Abstract

A 27-year-old woman at 17 weeks gestation was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with a history of fever, dyspnea, and dry cough for 3 days. She was diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) based on her nasopharyngeal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that was positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In the ICU, the patient developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and increased levels of inflammatory markers. She was then intubated for mechanical ventilation and had a treatment for critical COVID-19 illness during pregnancy. She also received three cycles on alternating days of therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) since she was failing to respond to conventional medical treatment. During hospitalization, the patient’s fetus was closely monitored by repetitive ultrasound. After 27 days of hospitalization and 10 days of mechanical ventilation weaning, the patient’s respiratory condition improved and her inflammatory biomarkers normalized. She was discharged from the hospital with an apparently healthy 20th week fetus. This case report highlights the role of TPE for treatment of ARDS due to cytokine storm in pregnant women with severe COVID-19 infection. This case emphasizes that careful evaluation of clinical and biological progression of the patient’s status is very important and when conventional therapies are failing, alternative therapies such as TPE should be considered.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pregnancy, ARDS, Fetus, Therapeutic plasma exchange, TPE

Key Summary Points

| Evidence-based treatment and management of pregnant women with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is still limited. |

| Cytokine storm-induced ARDS may contribute to the severe and critical illness conditions of pregnant women with COVID-19. |

| Therapeutic plasma exchange could be used as an adjunctive therapy for treating pregnant women with COVID-19—induced ARDS. |

Introduction

At the beginning of 2020, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic had devastating effects worldwide. The most severe complications of COVID-19 are acute respiratory distress syndrome, multi-organ failure, septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation and death [1, 2]. For these adverse outcomes, special populations have been considered at high risk for morbidity and mortality such as pregnant women, elderly, immunodeficiency disorders, active cancers, and transplantation recipients [3]. Obviously, the management of pregnant women with severe COVID-19 remains a challenge for physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pregnant women with COVID-19 have an increased risk of respiratory failure and obstetric complications, leading to miscarriage, premature delivery, or intrauterine growth restriction [4, 5]. Moreover, the data related to the treatment for severe COVID-19 in pregnant women are limited as compared with that for the general population.

Besides the conventional treatment for patients with severe COVID-19, therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) is an adjunct method based upon continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) machine to remove patient’s plasma and return it with another fluid (plasma or albumin) at the same volume [6, 7]. Although the benefits of TPE for patients with severe COVID-19, particularly for pregnant women, are not fully described, the effectiveness of this intervention has been reported in the treatment of severe COVID-19 patients in case reports [8, 9]. Unfortunately, there are few pregnancy-specific clinical trials for COVID-19 pregnant women because of the concerns of safety for the mother and fetus [9, 10]. Therefore, clinical reports on the treatment benefits of TPE in pregnancy associated with severe COVID-19 may contribute significantly to available therapies.

In this case report, we present the effectiveness of therapeutic plasma exchange for pregnant woman with severe COVID-19 in Viet Nam.

Case Presentation

A 27-year-old woman (Gravida 4, Para 3) at 17 weeks’ gestation developed fever, dry cough, and shortness of breath and presented at the local health center in Binh Duong Province, Vietnam. She was diagnosed with COVID-19 based on a nasopharyngeal swab polymerase chain reaction that was positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). She had the first COVID-19 vaccine dose 11 days before hospitalization, had no underlying medical conditions, or respiratory problems, and was not taking any medications.

At admission, the patient described a 3-day history of fever, shortness of breath, and dry cough. She was conscious with stable hemodynamic parameters. Her initial examination indicated a body temperature of 39.0 °C, oxygen saturation (SpO2) 84% on oxygen by mask (fraction of inspired oxygen [FiO2] of 60%), respiratory rate of 30 breaths/minute, blood pressure of 130/80 mmHg, and pulse of 125 beats per minute. She was then transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) of COVID-19 Centre of Binh Duong General Hospital because of her severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Investigations

The results of the patient’s biochemical blood test and arterial blood gas (ABG) are presented in Table 1. The tests were remarkable for an increase of liver enzyme (aspartate aminotransferase [AST] and alanine aminotransferase [ALT]) and inflammatory biomarkers (C-reactive protein [CRP], lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], and ferritin; Table 1) before TPE. The results of ABG done on admission and before TPE confirmed severe hypoxia associated with moderate hypercapnia (before TPE). She had normal renal function and coagulation tests.

Table 1.

Laboratory results before and after TPE treatment

| Investigations | Reference range | On admission | Before TPE | After TPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cell (109/l) | 4–11 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 15.5 |

| Neutrophil (109/l) | 2–8.10 | 6812 | 5904 | 13,203 |

| Lymphocytes (109/l) | 1.5–4.5 | 624 | 705 | 1084 |

| Platelet (109/l) | 140–500 | 223 | 273 | 337 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | < 1 | 6.3 | 11.0 | 2.6 |

| LDH (U/l) | < 247 | 410 | 430 | 270 |

| Fibrinogen (g/l) | 1.5–4.0 | 5.36 | 4.06 | 1.47 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 23·9–336·2 | 675.2 | 865.4 | 324.3 |

| AST (U/l) | 0–50 | 86 | 98 | 54 |

| ALT (U/l) | 0–50 | 124 | 127 | 58 |

| Glucose (mmol/l) | 4.1–5.9 | 9.6 | 7.4 | 5.8 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 35–52 | 26.4 | 28.3 | 34.6 |

| Creatinine (µm/l) | 58–96 | 45 | 35 | 64 |

| Arterial blood gas | HFNC | IMV | NIV | |

| FiO2 (%) | % | 100 | 100 | 60 |

| pH | 7.35–7.45 | 7.49 | 7.36 | 7.39 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 35–45 | 43 | 54 | 46 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 80–100 | 62 | 71 | 134 |

| HCO3− (mmol/l) | 18–23 | 32.8 | 30.5 | 22.6 |

| BE (mmol/l) | − 2 to + 3 | 8.6 | 4 | - 3.7 |

| A-aDO2 (mmHg) | 5–20 | 597 | 575 | 236 |

| PaO2/FiO2 | 62 | 71 | 221 |

AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, CRP C-reactive protein, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, HFNC high flow nasal cannula, IMV invasive mechanical ventilation, NIV noninvasive ventilation

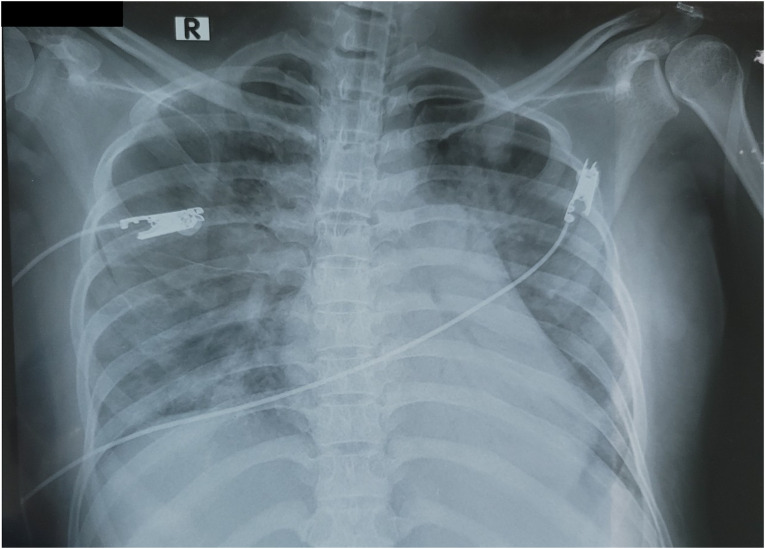

The patient’s chest X-ray demonstrated a bilateral alveolar infiltration (Fig. 1) and a normal abdominal ultrasound that also showed a live fetus that was normal for gestational age. The patient’s ECG (electrocardiogram) was sinus tachycardia at 117 bpm, but otherwise normal. Based on the above objective evidence she was diagnosed with COVID-19-induced severe ARDS.

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray at the time of admission

Treatment

At admission, she was initially placed on high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) with 100% FiO2 and flow of 60 l/min. However, her respiratory status was not improved after 24 h and HFNC was replaced on bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) with expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) of 8 cmH2O and inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) of 13 cm with 100% FiO2. At day 4 of hospitalization, due to her severe hypoxemia (respiratory rate of > 35 breaths/minute and SpO2 < 88% on BiPAP with FiO2 > 80%), the patient was intubated for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). The initial ventilator parameters were: VC (volume control) mode, RR (respiratory rate: 20/min), PEEP (positive end expiratory pressure: 10 cmH2O), Vt (Tidal volume: 300 ml [6 ml/kg]), I (inspiratory)/E (expiratory) ratio: 1/2, and FiO2 of 100%.

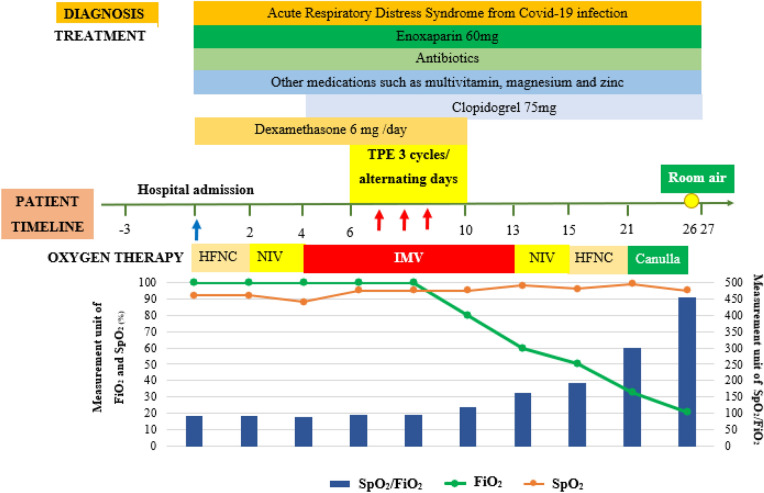

For medical therapy, the patient was treated with dexamethasone 6 mg/day, enoxaparin 60 mg twice a day, and clopidogrel 75 mg daily. The use of antiplatelet agent in association with preventive dose of enoxaparin was based on the critical status of the patient to prevent the additional risk of hypercoagulation related to platelet activation. She was also given ceftriaxone 2 g/day, multivitamin, magnesium, and zinc. Nutrition was assured via nasal gastric enteral feeding and supplemented with parenteral nutrition. On day 6 of hospitalization, secondary to clinical deterioration despite maximal conventional medical care, the patient was offered TPE (3 cycles/alternating day). After TPE with 20% of human albumin replacement, the patient’s clinical status, arterial blood gas, and biochemical parameters all improved (Fig. 2). There were any complications related to TPE had been detected in this patient.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of patient's clinical management progression. TPE therapeutic plasma exchange, HFNC high-flow nasal cannula, NIV non-invasive ventilation, IMV invasive mechanical ventilation, FiO2 fraction of inspired oxygen, SpO2 peripheral oxygen saturation

Outcome and follow-up

The results of blood gases realized at 24 h after the third TPE showed a significant improvement of PaO2 vs. 24 h before the first TPE (Table 1); and during that moment, the patient underwent IMV without any changes in ventilation parameters (ventilation mode: VC; PEEP 10 cmH2O; I/E = 1/2; Vt = 5 ml/kg). On day 12, the antibiotic treatment with ceftriaxone was changed to meropenem and linezolid because the patient developed a fever of 39 °C. She was extubated and placed on CPAP (FiO2 60%) at day 13, and changed to HFNC on day 15. Over the following days, flows and FiO2 gradually were reduced from 40 to 10 l/min, and 60–33%; respectively). By day 21 the patient was on nasal cannula with FiO2 of 33%, and finally on this day oxygen support was discontinued (Fig. 2). On day 27, the patient was discharged from the hospital in stable condition with what appeared to be a healthy 20-week gestational fetus. This case report was in compliance with ethics guidelines and patient consent for publication was obtained.

Discussion

This report is the first case of a pregnant woman with COVID-19-induced ARDS who was treated with TPE in combination with conventional therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in Vietnam. TPE is a treatment method used to remove a large number of high molecular weight substances from plasma that includes harmful antibodies, cytokines, and fibrin degradation products [7]. For this reason, TPE has been considered as a rescue therapy in different disorders. Generally, the first TPE cycle can remove about 55–65% of high molecular weight substances, the second cycle has the potential to remove an additional 20–25%, and finally the third cycle can often remove an additional 10% [7].

Obviously, the main indications of TPE are neurological diseases, including Guillain–Barre syndrome, myasthenia gravis, and chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. TPE is also used in non-neurologic diseases including hyperviscosity syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome, idiopathic thrombocytopenia, and renal and rheumatologic diseases [7, 11, 12]. Previous reports have suggested that TPE may be indicated for the treatment of septic shock [13], acute lung injury related to H1N1 influenza [14], and COVID-19 [8, 9, 15, 16].

The data from these reports seem to suggest a beneficial effect of TPE for treatment of the cytokine storm-induced ARDS related to COVID-19 [17, 18]. In severe COVID-19 infection, TPE removes toxins, deleterious inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and tumor necrosis factor, and other inflammatory mediators that may trigger the cytokine storm [16, 19]. In turn, TPE might also remove the SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, which are beneficial to recovery from the virus, but this hypothesis should be clarified since plasma cells continue to secret antibodies despite TPE [9]. Furthermore, in COVID-19 patients, it has been reported that excessively high levels of inflammatory cytokines released that induce severe diseases is a main indication to start TPE, especially in the early stages of COVID-19, to assure its success [20].

However, this case report has an important limitation related to a very small number of patients who received TPE (only one). Therefore, more studies with an adequate number of patients for randomized control trial should be done to confirm the role of TPE in treatment of pregnant women with COVID-19.

Conclusions

Our case report demonstrates that a pregnant female in her second trimester of pregnancy, with Berlin Consensus defined cytokine induced ARDS from COVID-19, and normal cardiac function, responded to TPE after failing to respond to conventional therapy [21, 22]. In addition to TPE, treatment with corticosteroids was initiated to decrease production of the inflammatory mediators [7, 23]. Finally, after three cycles of TPE, with the patient’s plasma replaced with 20% of human albumin, the patient’s clinical status and biochemical inflammation were improved and she was discharged from the hospital without any oxygen requirement, and what appeared to be a normal fetus for gestational age.

In light of our findings, and other case reports noted above, TPE may be a useful intervention for selected pregnant women with cytokine storm-induced ARDS secondary to COVID-19 who are failing to respond to conventional therapeutic interventions. Obviously, more work needs to be done to confirm the efficacy and safety of TPE for the treatment of pregnant women with COVID-19-induced ARDS; and future prospective randomized studies are also required to confirm the beneficial role of TPE in the treatment of COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Sy Duong-Quy, Duc Huynh-Truong-Anh, Thanh Nguyen-Thi-Kim, Tien Nguyen-Quang, and Thanh Nguyen-Chi: data collection. Sy Duong-Quy, Nhi Nguyen-Thi-Y, Van Duong-Thi-Thanh, Carine Ngo, and Timothy Craig: manuscript drafting. Sy Duong-Quy, Duc Huynh-Truong-Anh, Carine Ngo, and Timothy Craig: manuscript approving.

Disclosures

Sy Duong-Quy, Duc Huynh-Truong-Anh, Thanh Nguyen-Thi-Kim, Tien Nguyen-Quang, Thanh Nguyen-Chi, Nhi Nguyen-Thi-Y, Van Duong-Thi-Thanh, Carine Ngo, and Timothy Craig have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This case report was in compliance with ethics guidelines and patient consent for publication has been obtained.

References

- 1.Azer SA. COVID-19: pathophysiology, diagnosis, complications and investigational therapeutics. New Microbes New Infect. 2020;37:100738. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou X, Cheng Z, Luo L, Zhu Y, Lin W, Ming Z, et al. Incidence and impact of disseminated intravascular coagulation in COVID-19 a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res. 2021;201:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JI, Im Y, Song JE, Jang SJ. Healthcare considerations for special populations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a review. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2021;51(5):511–524. doi: 10.4040/jkan.21156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wastnedge EAN, Reynolds RM, van Boeckel SR, Stock SJ, Denison FC, Maybin JA, et al. Pregnancy and COVID-19. Physiol Rev. 2021;101(1):303–318. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berkowitz K, LaSala A. Risk factors associated with the increasing prevalence of pneumonia during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163(3):981–985. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91109-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bobati SS, Naik KR. Therapeutic plasma exchange—an emerging treatment modality in patients with neurologic and non-neurologic diseases. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(8):EC35–EC37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.CMcG/AH. Guidelines for therapeutic plasma exchange in critical care: National Health Service. 2019. https://www.bsuh.nhs.uk/library/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/09/TPE.pdf.

- 8.Jaiswal V, Nasa P, Raouf M, Gupta M, Dewedar H, Mohammad H, et al. Therapeutic plasma exchange followed by convalescent plasma transfusion in critical COVID-19—an exploratory study. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:332–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khamis F, Al-Zakwani I, Al Hashmi S, Al Dowaiki S, Al Bahrani M, Pandak N, et al. Therapeutic plasma exchange in adults with severe COVID-19 infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;99:214–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pastick KA, Nicol MR, Smyth E, Zash R, Boulware DR, Rajasingham R, et al. A systematic review of treatment and outcomes of pregnant women with COVID-19—a call for clinical trials. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(9):ofaa350. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padmanabhan AC-SL, Aqui N, Balogun RA, et al. Guidelines on the use of therapeutic apheresis in clinical practice—evidence-based approach from the Writing Committee of the American Society for Apheresis: the eighth special issue. J Clin Apher. 2019;34:171–354. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Knaup H, Stahl K, Schmidt BMW, Idowu TO, Busch M, Wiesner O, et al. Early therapeutic plasma exchange in septic shock: a prospective open-label nonrandomized pilot study focusing on safety, hemodynamics, vascular barrier function, and biologic markers. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):285. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2220-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hadem JHC, Schneider AS, Wiesner O, et al. Therapeutic plasma exchange as rescue therapy in severe sepsis and septic shock: retrospective observational single-centre study of 23 patients. BMC Anesthesiol. 2014;14(24):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-14-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel PNV, Vanchiere J, Conrad SA. Use of therapeutic plasma exchange as a rescue therapy in 2009 pH1N1 influenza A—an associated respiratory failure and hemodynamic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(2):87–89. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e2a569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faqihi F, Alharthy A, Abdulaziz S, Balhamar A, Alomari A, AlAseri Z, et al. Therapeutic plasma exchange in patients with life-threatening COVID-19: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2021;57(5):106334. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang LZH, Ma S, Chen J, et al. Efficacy of therapeutic plasma exchange in severe COVID-19 patients. Br J Haematol. 2020;190:181–232. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Felsenstein S, Herbert JA, McNamara PS, Hedrich CM. COVID-19: Immunology and treatment options. Clin Immunol. 2020;215:108448. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin SH, Zhao YS, Zhou DX, Zhou FC, Xu F. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): cytokine storms, hyper-inflammatory phenotypes, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Genes Dis. 2020;7(4):520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balagholi S, Dabbaghi R, Eshghi P, Mousavi SA, Heshmati F, Mohammadi S. Potential of therapeutic plasmapheresis in treatment of COVID-19 patients: Imm. Transfus Apher Sci. 2020;59(6):102993. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2020.102993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang XH, Sun RH, Zhao MY, Chen EZ, Liu J, Wang HL, et al. Expert recommendations on blood purification treatment protocol for patients with severe COVID-19. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2020;6(2):106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cdtm.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maisel AMC, Adams KJ, Anker SD, et al. State of the art: using natriuretic peptide levels in clinical practice. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:824–839. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cappanera S, Palumbo M, Kwan SH, Priante G, Martella LA, Saraca LM, et al. When does the cytokine storm begin in COVID-19 patients? A quick score to recognize it. J Clin Med. 2021;10(2):297. doi: 10.3390/jcm10020297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]