Abstract

COVID‐19 causes lasting neurological symptoms in some survivors. Like other infections, COVID‐19 may increase risk of cognitive impairment. This perspective highlights four knowledge gaps about COVID‐19 that need to be filled to avoid this possible health issue. The first is the need to identify the COVID‐19 symptoms, genetic polymorphisms and treatment decisions associated with risk of cognitive impairment. The second is the absence of model systems in which to test hypotheses relating infection to cognition. The third is the need for consortia for studying both existing and new longitudinal cohorts in which to monitor long term consequences of COVID‐19 infection. A final knowledge gap discussed is the impact of the isolation and lack of social services brought about by quarantine/lockdowns on people living with dementia and their caregivers. Research into these areas may lead to interventions that reduce the overall risk of cognitive decline for COVID‐19 survivors.

Keywords: Alzheimer's risk factor, caregiver burden, COVID‐19, delerium, longitudinal cohort, systemic inflammation, SARS‐CoV‐2

1. INTRODUCTION

The global pandemic of COVID‐19 caused by the SARS CoV‐2 virus has disrupted virtually every aspect of human life. The authors here are part of the ISTAART Professional Interest Area (PIA) Immunity and Neurodegeneration. The PIA is producing a series of review‐like articles with the purpose of highlighting perceived gaps in knowledge regarding the goal of the ROADMAP established as part of the Alzheimer's Disease Plan to develop disease‐modifying treatments for dementia by 2025. This specific manuscript will focus on knowledge gaps regarding the impact of COVID‐19 on the risk of development and progression of dementia. This review is not intended to provide a comprehensive summary of our current knowledge regarding COVID‐19 effects on the brain, and the reader desiring such a summary is referred here 1 . Instead, this review will illustrate select items that are not yet known regarding COVID‐19 and dementia, and the research needed to provide potential treatments for mitigating the influence of COVID‐19 on Alzheimer‘s disease (AD) and other dementias. The opinions expressed in the manuscript are solely those of the authors and do not represent the opinions of the Alzheimer's Association or ISTAART.

Indeed, anecdotal and literature reports are emerging of cognitive and psychological symptoms after COVID‐19. Four months after COVID‐19 hospitalization, 30‐40% of patients report problems with memory, attention and sleep, while 10‐15% of patients report loss of taste and/or smell 2 . Increasing media attention is devoted to “COVID‐19 fog,” a nonspecific mental syndrome after COVID‐19 infection which can include fatigue, inattention, poor concentration, memory complaints, lack of motivation and difficulty working long hours. Younger people are also at risk for COVID‐19 related cognitive symptoms, even in the absence of serious disease. Although recent reviews have described the constellation of cognitive symptoms associated with COVID‐19 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , and what is known about their molecular underpinnings, a central question that remains is whether the neurological symptoms observed in people with COVID‐19 can be long‐lasting (>6 mo) or even progressive, possibly increasing risk of cognitive impairment or dementia. A related question is, in people living with dementia, does infection with COVID‐19 accelerate or aggravate the course of the existing disease? One mechanism by which SARS CoV‐2 could impact cognitive function is by direct infection of the brain. The olfactory tract showed the highest concentration of ACE2 enzymes, the cell surface receptor for SARS CoV‐2 6 . Further the brains of AD patients have elevated levels of ACE2 7 .

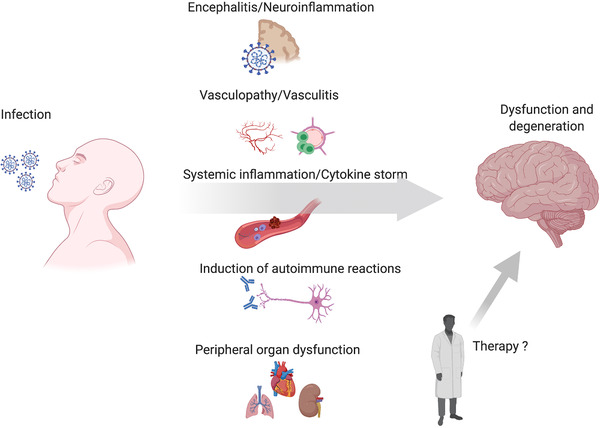

A central question that remains is whether the neurological symptoms observed in people with COVID‐19 are due to (i) overstimulation of a systemic inflammatory response/cytokine storm, (ii) encephalitis as a result of brain invasion of SARS‐CoV‐2, or both, (iii) perfusion deficits through vasculitis or vasculopathy, (iv) the induction of autoimmune reactions, or (v) peripheral organ dysfunction (Figure 1). The investigation of disease mechanisms is critical to apply the appropriate treatments in patients with acute or chronic brain alterations, and could be crucial to treat COVID‐19 properly to prevent subsequent cognitive decline (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Modes of SARS CoV‐2 impact on the central nervous system. There are multiple means by which COVID‐19 may lead to neural dysfunction. There can be direct brain invasion by SARS‐CoV2 during systemic infection. Vascular inflammation and pathological changes of the cerebral vessel endothelium represents a second route by which Covid‐19 can affect brain function, together with a systemic coagulopathy this pathological mechanism may account for ischemic strokes. A major concern is the extreme systemic inflammatory reaction which can feedback onto the brain and provoke neural damage through the excess generation of inflammatory mediators including complement factors, prostanoids, cytokines and chemokines. A further mechanism is the generation of self‐recognizing antibodies causing autoimmune disease including but not limited to Guillain‐Barré syndrome as a consequence of immune recognition of the virus. Finally, the transient or persistent loss of normal function of peripheral vital organs may have lasting impact on the brain. Further possible consequences of therapy such as unwanted side‐effects of antiviral medication or vaccination may have to be considered in future.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic review: The authors reviewed the published literature on neurological consequences of COVID‐19 infection and the mechanisms by which infections might challenge the CNS. Specific attention is paid to the possibility of increased risk for subsequent cognitive impairment.

Interpretation: We believe there are several gaps in knowledge regarding the symptoms and genetic polymorphisms associated with increased risk of cognitive impairment, the need for model systems to understand mechanisms and the need for longitudinal clinical cohorts to confirm risk factors to close these gaps.

Future directions: Identifying features of COVID‐19 infection increasing risk of cognitive impairment and developing experimental models in which to test interventions may help reduce risk for dementia in those recovering from COVID‐19

Infectious disease is a strong risk factor for the development of cognitive deficits. Experience from cohort observations suggest that systemic inflammation, as frequently experienced during COVID‐19 infection, is associated with subsequent cognitive decline 8 and also results in persisting EEG changes and hippocampal atrophy 9 . Many systemic infections and associated inflammation can result in acute, rapidly changing episodes of delirium. Symptoms include confusion, agitation, disorientation, memory complaints, impairments in consciousness and hallucinations. Approximately 30% of seniors over the age of 65 admitted to emergency care due to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection experience delirium 10 . Delirium is the sixth most common COVID‐19 symptom experienced, and is so common that it should be included among diagnostic criteria. The presence of delirium increases requirements for ICU placement and death as an outcome. Importantly, approximately one‐third of these patients do not express typical respiratory symptoms. Delirium is also a harbinger of long‐term cognitive consequences, such as increased risk for developing AD 11 , 12 , 13 . Delirium can induce more rapid decline in patients with preexisting dementia. Thus, COVID‐19 can have adverse effects on cognition secondary to the extreme inflammatory events associated with infections, especially in older patients.

Another significant finding from people dying from COVID‐19 is the increased degree of thrombosis. This primarily impacts lung tissue, but can include other organs such as liver, heart and the brain, where the thromboembolism can cause a stroke 14 . Clearly this can add to other dementia‐inducing pathologies to both accelerate the course of cognitive impairment in those already diagnosed and increase subsequent risk.

Thus, it is critical to ascertain whether infection with SARS‐CoV2 increases the risk of subsequent, long‐term cognitive decline and/or accelerates the onset or progression of AD and AD‐related dementias. We must develop an understanding of short‐ and long‐term cognitive sequelae that contribute to decreased quality of life and cost to society, especially in diverse populations. If even a fraction of COVID‐19 infected individuals experience increased risk, there would be a great increase in cognitive decline and/or AD in the future. In this roadmap, we discuss research knowledge gaps and highlight strategies to help mitigate the effects of COVID‐19 on the brain, particularly in at‐risk populations.

These long‐term cognitive consequences may be especially widespread or severe for historically underserved racial and ethnic groups. In Northern California, for example, positivity rates are twice as high in African‐Americans and four times higher in Hispanic adults versus Whites 15 . African‐Americans communities also have disproportionately higher death rates due to COVID‐19 16 , 17 . More positive and severe cases may, in turn, lead to greater risk for AD, despite Hispanic and African‐American seniors already being 1.5 and 2 times as likely to develop Alzheimer's disease or other dementias 18 . It is therefore essential to investigate, understand, and treat brain health and cognitive function in this highly at‐risk crossover population, to avoid a considerable increase in future patient numbers of AD, which already requires 1 in 5 Medicare dollars 19 .

2. UNDERSTANDING THE MAGNITUDE AND PROGRESSION OF COGNITIVE SYMPTOMS AFTER SARS‐CoV‐2 INFECTION

Based upon clinical presentation, studies should be undertaken to identify individuals who are at increased risk of current or subsequent cognitive decline after SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. It will be necessary to determine novel syndromes resulting from SARS‐CoV‐2 infection that predict the risk of subsequent cognitive decline. This will codify, to the extent feasible, those variables in medical records that are most important to collect for the purposes of predicting later cognitive function. To identify those most at risk, three categories of factors should be monitored as detailed below, with clarification of the existing gaps in knowledge to guide future research studies. All three factors will stratify by race, sex and age.

Symptoms directly resulting from COVID‐19 infection, including disease severity. The constellation of symptoms should include whether patients experience specific symptoms in respiratory, thrombolytic, skeletomuscular, febrile, gastrointestinal and/or neurological systems. In addition, indicators of disease severity such as hospitalization, oxygenation and mechanical ventilation and blood immune parameters should be collected from hospitalized and perhaps more importantly, nonhospitalized cases, as data are emerging that mild cases may still develop cognitive impairment.

Patient medical history of preexisting conditions. While there are a range of potential impacts from COVID‐19 alone, patients with comorbidities stemming from obesity, hypertension, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease (CVD) or pulmonary dysfunction are more likely to develop severe symptoms. Some of these comorbidities already predispose to cognitive decline. The combination of comorbidities predisposing to neurological risk, together with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, is expected to worsen the risk of cognitive decline.

Patient treatment. Remdesivir, dexamethasone, benzodiazepines, convalescent plasma, monoclonal antibodies, and other new, emerging or experimental therapeutics should be monitored to allow future determination of the contribution to cognitive decline. Longitudinal follow‐up will allow determination of whether any treatment done at the time of infection or after, such as vaccine treatments, can ameliorate or worsen long‐term effects.

3. BIOFLUID, IMAGING, OR GENETIC MARKERS TO PREDICT SUBSEQUENT COGNITIVE DECLINE AFTER SARS‐CoV‐2 INFECTION

Biomarkers are needed to: 1) distinguish neurological symptoms in patients with mild or asymptomatic infection; 2) determine if levels of inflammatory and brain injury markers also predict the risk of cognitive decline; 3) provide molecular insights into COVID‐19 pathogenesis and progression, and 4) to monitor treatment effects. However, there are substantial barriers to this approach that must be overcome. Most of the current studies with these biomarkers have been carried out in small populations, which can provide a biased representation. Larger sample sizes focusing on the neurological and neuropsychiatric alterations of patients are needed to overcome this barrier. This need is compounded by patients with remarkably diverse disease symptoms that reflect severe, mild, or asymptomatic infection 5 . Likewise, it will be important to test sub‐populations of individuals with different comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular, immunosuppressive and chronic respiratory diseases, and substance use disorders 20 as well as the contribution of aging to the risk of neurological damage. Finally, while blood or saliva is easier to sample in the clinical COVID‐19 setting, CSF collection will be important to better understand whether the impact on the CNS is through direct infection or via secondary effects.

Despite these challenges, there are several AD biofluid markers that are promising. Biomarkers of CNS injury in plasma and CSF have been reported to be elevated in hospitalized patients with mild to severe COVID‐19, including neurofilament light chain protein (NfL), released because of neuronal damage; glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), S100b, astrocytic markers for injury; and total tau, a general marker of neurodegeneration 21 , 22 . Increased levels of NfL in the CSF of patients with central neurological symptoms have been correlated with the level of consciousness and disease severity 22 . Circulating levels of inflammatory biomarkers are increased in most COVID‐19 patients and could also contribute to the characterization of disease progression. Some of these markers are cytokines including interleukin (IL)‐6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and other molecules such as C‐reactive protein and complement system proteins C5, C6, and C8 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , some of which have been reported to predict cognitive decline post sepsis 27 .

More broadly, COVID‐19 and AD may share broad neuropathological signatures that offer other routes of discovery for biomarkers. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection is associated with an exaggerated systemic inflammatory response that can cause blood‐brain barrier (BBB) breakdown. In turn, this can exacerbate brain damage by allowing entry of viral particles, peripheral immune cells, and other molecules into the CNS 28 . Therefore, measuring BBB permeability biomarkers might also be useful, such as CSF/plasma albumin ratio 29 , PDGFRβ 30 and perhaps tight junction markers impacted by AD pathology, such as claudin‐5 and occludin 31 . Further, it is necessary to identify whether the BBB disruption is a transient or long‐term complication, as observed in neurodegenerative diseases. Such disruption may also affect nutrient transport or uptake based on related genotypes. For example, deleterious mutations in water channel genes like aquaporin‐4 can impact nutrient transport across the BBB 32 and cognitive decline 33 .

Dysregulated glucose metabolism may also be a common culprit for inducing cognitive disruption in COVID‐19 and AD. Obesity causes systemic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction. In turn, excess glucose and insulin are related to COVID‐19 severity risk, and insulin treatment worsens outcomes 34 . Similarly, acute or lingering COVID‐19 effects may exacerbate the relationships of these obesity factors on cognitive decline 35 , brain atrophy 36 , and reduced brain glucose use in parietal and frontal areas that subserve memory and higher‐order cognition 37 . This last point is key, as less glucose use in these areas is one of the earliest signs of AD. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection may directly cause the immune cells of the brain to further alter this metabolism. It may therefore be important to use PET imaging to track brain glucose use, beta‐amyloid deposition, tau accumulation, immune activation, or even MRI‐based blood flow as a reasonable proxy, to establish the neural correlates of COVID‐19 cognitive dysfunction.

Besides the analysis of fluid biomarkers, such neuroimaging measurements are fundamental to understand mechanisms that could lead to cognitive decline. Current COVID‐19 imaging data is limited to small case series, so larger clinical cohorts are needed to confirm related brain parenchymal signal alterations. When available, brain MRI has been widely used across institutions to evaluate patients with neurological manifestations 38 , 39 , 40 . PET imaging could separately provide several insights. First, in vivo imaging for markers of neuroinflammation via PET ligands (TSPO, COX‐2) may inform clinical evaluation of COVID‐19 and preclinical risk of cognitive decline. PET imaging can also track metabolic and neurotransmission signaling system changes that accompany neurological damage and cognitive decline. Finally, PET has determined pathophysiological mechanisms underlying neurodegenerative disease and cognitive decline (e.g., amyloid beta, tau) that may also be relevant for COVID‐19 41 . However, acquiring imaging data of COVID‐19 patients might be challenging depending upon the setting. The spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 in some centers could be enhanced due to the entry of infected patients into imaging facilities. In addition, the protocol to perform brain imaging in unstable patients under intensive care may not be possible in all cases. One strategy could be to take neuroimaging measures after total recovery from COVID‐19 and correlate it with cognitive tests and fluid biomarkers in a follow‐up. Consequently, historical averaged data of patients would be available for comparative purposes. The obtained imaging data could help to determine whether the CNS impact is transient or long‐lasting, and detail the cells and brain regions affected.

Several studies have identified genetic risk factors associated with severity and/or susceptibility to infection with COVID‐19, which may be important contributors to cognitive dysfunction. For example, it is well known that blood type O is slightly protective and type A carries slightly greater risk 42 . A variant region carrying approximately 6 genes on Ch3 triples the risk of severe disease as indicated by ventilator or supplemental O2 use 43 . Interestingly, this variant is derived from Neanderthal and shows ethnic variation in distribution, with high frequency of expression in south Asian (50%), middle frequency in European (16%) and low frequency in African (0%) ancestry 44 . Candidate genes in this region are related to inflammatory processes (chemokine receptors CXCR6, CCR2, CCR3) and amino acid transporters, including one that interacts with ACE2, the receptor that mediates cellular entry of SARS‐CoV viruses (see below). Other linkages to innate antiviral defense (interferon receptor IFNAR2, OAS) gene variants and genes involved in lung inflammation, injury, and cancer (DPP9, TYK2, FOXP4) have been described. Finally, linkage with APOE4 has been reported, which doubled risk of developing severe disease 45 . APOE4 is also a major risk factor for AD. Future genome wide association studies utilizing consortia of samples with cognitive symptoms after COVID‐19 infection will be required to validate and identify new risk alleles. Once variants associated with defined constellations of cognitive symptoms have been elucidated, then genetic analysis of specific SNPs could be incorporated as a biomarker in future studies. Twin studies could be informative as well, because anecdotal reports of twins or family members with highly discordant disease trajectories abound.

Postmortem tissues and curated COVID‐19 brain banks will also answer important questions related to the neurologic features of COVID‐19 on the brain. Such approaches have already highlighted microvascular pathology in patients using high‐resolution magnetic resonance imaging combined with standard histopathological examination. In addition, this tissue would provide opportunities for detailed sequencing experiments on CNS cells akin to other experiments performed on blood and lung tissues (during COVID infection) as well as existing transcriptional dataset of aging, AD, and other ADRDs.

Lastly, it is critical to establish and maintain robust, longitudinal studies, which are needed to correlate cognitive impairment and the neurodegenerative process with biomarker measurements. Such evaluations, though difficult to perform in severe patients, can include neuropsychiatric evaluation, imaging measurements, and fluid collection. The development of biobanks of blood and CSF samples from patients collected from various time points throughout the disease will be extremely important to expand basic and clinical research. However, the mechanisms of infection and neurological damage might not be the same for all patients. The characterization of risk of developing cognitive decline due to COVID‐19 through blood and CSF biomarkers and genetic variants associated with COVID‐19, in larger, longitudinal cohorts could be key in solving this issue.

4. MODELS FOR INFECTION IN WHICH MECHANISMS AND EXPERIMENTAL INTERVENTIONS MIGHT BE INTERROGATED

To enable controlled mechanistic studies and therapeutic interventions, model systems are essential. Research with animal models should be strategically designed and critically evaluated. As is likely in humans, it has been demonstrated that susceptibility to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in animals is a function of several factors, including angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE) composition, immune response and other factors 46 . One mode of cellular entry for SARS‐CoV viruses is via binding to cell surface ACE2 47 . Neuronal infection is achieved in mice humanized at the ACE2 gene 48 . To determine mechanisms by which SARS‐CoV‐2 affects cognition, one approach might be to characterize the influence of COVID‐19 upon cognitive function in mice that have been humanized at the ACE2 gene. This would include deep phenotyping for immunohistochemistry, biochemistry (quantifying inflammation and neuronal damage), gene expression and cognitive behaviors. In parallel, to specifically address the influence of SARS‐CoV2 infection on development of AD‐like pathology and cognitive deficits, humanized ACE2 mice should be crossed to AD mouse models, and the onset and progression of brain pathology and cognitive function explored longitudinally. This could include existing models of familial AD/amyloidosis such as APP/PS1, Tg2576 or APP knock‐in mice or models with tauopathy.

In addition, newer models of late onset amyloid are being developed by the NIA‐funded MODEL‐AD and others 49 . In the near future, they should be available to test the consequences of viral dose‐responsive pathologies and peripheral vs. central dominant SARS‐CoV2 infection on development of AD‐like pathology and AD‐related dementias. Moreover, the use of animal models mimicking human comorbidities could also help to understand the contribution of other diseases in COVID‐19 progression associated with neuropsychiatric consequences. Considering the evidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in the brainstem, which controls respiratory and cardiovascular function 50 , COVID‐19 may worsen cardiac and respiratory function in patients with severe symptoms. Therefore, it is appropriate to complement ongoing research and investigate these mechanisms in a CNS‐mediated manner. Once the candidate drivers of neuroinflammation or neuropathology are identified, these rodent models may be complemented by models coupling or mimicking human comorbidities, and/or use of organoids, human iPSC derived brain cells, primary‐tissue‐derived human cells or human‐on‐a‐chip models. These models may not require infection to determine mechanisms by which either viral infection or the inflammatory response impacts cognition. These controlled systems should be able to test downstream molecular consequences and experimental therapeutics to ameliorate cognitive decline.

5. THE NEED FOR LONGITUDINAL STUDIES, AND DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

5.1. Studies using existing longitudinal cohorts

One question regarding the long‐term consequences of COVID‐19 illness is what effects the virus might have on cognitive function, both immediately and delayed over time. A cost‐effective opportunity is to begin tracking COVID‐19 indices over the many ongoing longitudinal studies of older adults. These include stand‐alone studies, clinical cohorts of ADRCs, and large registries in Europe, among other sources. It is likely that some participants in these longitudinal cohorts have or will contract COVID‐19 at some point. The populations enrolled in these studies are unfortunately the ones which have the greatest risk of severe illness and death. Those who have confirmed diagnosis of the disease and survive may supply a wealth of information regarding the impact of the illness upon cognitive function. For example, the UK Biobank study in England has a large number of participants with extensive medical histories. Many have data comprising brain and enteric MR imaging, biofluid (but not CSF), and cognitive function. The study is presently following 20,000 adults who have contracted COVID‐19. Many European countries have similar longitudinal studies, including Germany and Sweden, with extensive banked CSF samples. In the USA, there are the NIA ADRC cohorts which are followed longitudinally, have a core set of cognitive function evaluations and in many cases brain imaging, in addition to a series of ongoing observational and interventional cohorts including large numbers of older adults.

Most older adults enrolled in these longitudinal cohorts have relatively in‐depth cognitive evaluations that are repeated at set intervals. Within these cohorts, COVID‐19 patients and survivors could be identified. This design offers the opportunity to examine the rates of cognitive decline among these groups, as opposed to cross‐sectional measurement of mean cognition scores for those with exposure compared to those without exposure outside of longitudinal studies. One approach to consider is to establish case controls for the index participants. Within the same study cohort, an individual confirmed to have been exposed to COVID‐19 would be matched for age, sex, APOE status, cognitive performance and possibly other variables to another study participant who has not been exposed to COVID‐19. There may be an opportunity to confirm non‐exposure with antibody testing for a short time, although widespread vaccination of these populations will soon render antibody titers uninformative regarding prior infection. Thus, it is likely that reliance on absence of symptoms and possibly a negative PCR test will need to suffice in determination of non‐exposure to COVID‐19. The case‐control approach does not preclude other types of comparisons within these cohorts, but may offer the most statistical power in determining: a) if COVID‐19 exposure accelerates cognitive decline; and b) what factors might moderate this influence of COVID‐19 exposure.

It will be important to establish consortia to fully investigate how COVID‐19, cognitive decline, and neurodegenerative diseases are linked. In the US, each ADRC or other longitudinal study is unlikely to have a sufficient number of positive cases for robust statistical comparisons. ADRC cohorts typically include 500 cases or less. Assuming a minimum of 9% overall infection rate (e.g. 29 million Americans infected to date out of 330 million), this would result in 45 index cases in a given location. This is unlikely to provide sufficient power to detect moderate effect sizes regarding cognitive decline. However, collectively, thirty ADRCs could identify 1350 index cases and a similar number of case controls, which may provide the power necessary to identify biofluid, imaging, or other factors that associate with the rate of decline. This will require adoption of well described, harmonized protocols across sites. Indeed, one important feature of the ADRC longitudinal cohorts is that they use a common set of cognitive function tests (NACC). Thus, with minimal additional effort, there could be ADRC consortia that would agree to a set of study protocols to work together on this question. In addition to establishing index cases in current and future enrolled ADRCs, UK Biobank, and broad‐based European cohorts such as FINGER and POINTER, researchers could incorporate, curate, and harmonize data to understand and perhaps mitigate the effects of COVID‐19 on the brain.

Operationally, this would require adding questions to interviews regarding COVID‐19 exposure to the study protocols. Those confirming exposure would then be asked to provide access to medical records and symptoms assessment. Important factors to include would be symptomology, severity, comorbid conditions, treatments and lingering immunologic or behavioral effects. Over the subsequent years, the rates of change in cognitive function can be monitored for both the index cases and the matched control cases. Excess decline in the index cases would support the concept that COVID‐19 has enduring influences and that reduced cognitive function is among these. If these effects are accumulated over years, it may portend a surge in cases of dementia years after the pandemic has largely concluded. Identifying those symptoms or treatment decisions (signaling severity of the disease) which are linked to the greatest rates of decline in the index cases can then identify those older adults not part of longitudinal studies who are most at risk for cognitive decline and more aggressive detection and treatment protocols.

5.2. New prospective studies

Initiating longitudinal studies of community based COVID‐19 related cognitive decline is imperative. First, this should involve patients who have or had an extended duration of COVID‐19 symptoms, including young adults. For example, 25% of 25‐34 year old adults positive for COVID‐19 still showed symptoms at 5 weeks after testing positive 51 . Further, COVID‐19 may involve considerably longer‐term impact, as demonstrated by a study in China which showed that 76% of patients retained at least one symptom after 6 months 52 . If these patients experience sustained inflammation or inflammation‐induced secondary pathogenetic mechanisms the brain may suffer from long‐term damage and the risk for amnestic and cognitive dysfunction may increase. Follow up targeted therapies would therefore be recommended.

Consequently, a registry of the greater population (non ADRC/not already in other longitudinal studies) should be created, including those identified as infected, who report loss of cognitive function as an immediate follow up of the infection, and those as yet unknown to suffer cognitive decline. Basic demographics such as age, sex and race/ethnicity would be collected in addition to the three factors described above. Banked biofluid samples and biomarker data at admission to hospital or at time of diagnosis could be incorporated. Emerging biomarkers and novel insights from model systems should be incorporated into studies in an iterative process. This would allow retrospective analysis of whether COVID‐19 infection/illness or related treatments including vaccination affects the rate of onset or progression of cognitive decline over time, as well as prospective studies to identify individuals with COVID‐19 who are at increased risk of current or subsequent cognitive decline based upon clinical presentation. Biobanking of fluid and tissue samples would allow future examination of additional or novel emerging causative influence.

The Long‐COVID patient population (‘COVID long‐haulers’) must also be closely monitored specifically for cognitive decline. Repeated monitoring/measuring of early biomarkers of decline will enable prevention of years of costly treatment. Research is needed to define in detail the impact of these long‐term symptoms on the brain in this at‐risk patient population. Large scale studies of invasive and non‐invasive measures of brain health must be carried out as soon as possible to be able to document any COVID‐relevant changes, and to enable patients to recall pre‐COVID experiences/health more accurately.

5.3. Sociological factors of pandemic life

Another potential role of longitudinal cohorts may be to identify social factors influencing risk. Irrespective of exposure, the pandemic has considerable impact on the psychological well‐being of many older adults (as well as young people). We expect there will be long term consequences of the social circumstances associated with isolation, lockdowns, loneliness and stress on cognitive function. All of these are known risk factors for subsequent cognitive decline. Thus, other add‐on studies may interview longitudinal study participants to query their social experiences during the pandemic, including lifestyle changes, social support and interactions, anxiety levels and fear of infection. Results could be tabulated into a severity of social stress scale to be used in comparison with the rate of cognitive decline, collected as part of the ongoing or new longitudinal studies.

Given the vast numbers of Americans who will be vaccinated over the next few months, ranging in age, race, and socioeconomic status, there is a unique opportunity to reach many people who may not otherwise have contact with healthcare providers.

First, this could either be used to collect information on a population to follow in the future in the types of longitudinal studies described above. The COVID‐19 vaccinated population could form a large study population of general vaccination outcome if a control group could be found. Alternatively, these study populations could provide healthcare information on lifestyle changes or other latent parameters associated with reduced incidence of future cognitive decline. Recent work demonstrates that up to 40% of dementias could be prevented through modifiable risk factors, including lifestyle changes 53 . Information on awareness of the potential impact of COVID infection on brain health would be helpful in mitigating a future onslaught of patients with cognitive decline. Patients aware of the potential for future cognitive decline might be more likely to note symptoms when they appear, and contact healthcare providers. There have been some very successful previous educational campaigns on stroke awareness (FAST symptoms) and breast cancer self‐monitoring. An educational campaign to inform the public about cognitive decline after COVID and how symptoms which those outside research may not link to the brain (e.g. loss of smell) can be relevant. Components of an educational program should include education on brain health, awareness of symptoms and societal preparation for significant uptick in future patients with cognitive decline, potentially from a younger age.

6. CONCLUSIONS

We suggest an immediate implementation of strategies that will enable us to foresee a virus‐induced “new wave” of dementia. This will allow both for planning for new cases and for development of novel effective therapeutics applied either at the initial onset of infection or later to prevent the development of neurological damage and subsequent loss of cognitive ability. The proposed organization of primary research could additionally be a relevant guide for future pandemics involving neurological effects from infection, laying out a framework for rapid response. We do not claim that these four areas are exhaustive of the knowledge needed to prepare for the cognitive consequences of the current and future pandemics. However, we wish to highlight these priorities, and the need to move quickly before data and samples are lost.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

D. Morgan consults with Abbvie, is a member of the Speaker's Bureau at Biogen, and receives research support from Hesperos. Michael T. Heneka serves as an advisory board member at IFM Therapeutics, Alector, Cyclerion and Tiaki. He received honoraria for oral presentations from Novartis, Roche, and Biogen. Dr Terrando receives research support from Takeda, Fresenius Kabi, Exalys Therapeutics, and Reservoir Neuroscience. Drs Gordon, LePage, Limberger, Tenner, Willette and Willette have nothing to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This manuscript was facilitated by the Alzheimer's Association International Society to Advance Alzheimer's Research and Treatment (ISTAART), through the Immunity and Neurodegeneration Professional Interest area (PIA). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication represent those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the PIA membership, ISTAART or the Alzheimer's Association. AW was funded by Iowa State University, NIH R00 AG047282, and AARGD‐17‐529552. CL received a scholarship from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) [131409/2020‐4]. NT was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 AG057525, R01 AG057525‐04S1, R21 AG055877‐01A1, R03 AG064260, 3P01‐AT009968‐01A1, and the Alzheimer's Association. AT is supported by NIA R01 AG060148 and U54 U54 AG054349. MNG is supported by NIH R01 AG062217 and the Spectrum Health‐MSU Alliance Corporation. DM is supported by R01 AG‐051500, R01AG070349, R44AG058330, and the MSU Foundation. LLP is supported by Supported by an Alzheimer's Association Research Fellowship, a BrightFocus postdoctoral fellowship award and R01AG064170.

Gordon MN, Heneka MT, Le Page LM, et al. Impact of COVID‐19 on the Onset and Progression of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias: A Roadmap for Future Research. Alzheimer's Dement. 2022;18:1038–1046. 10.1002/alz.12488

All authors contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. de Erausquin GA, Snyder H, Carrillo M, et al. The chronic neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID‐19: The need for a prospective study of viral impact on brain functioning. Alzheimers Dement. 2021:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garrigues E, Janvier P, Kherabi Y, et al. Post‐discharge persistent symptoms and health‐related quality of life after hospitalization for COVID‐19. J Infect. 2020;81(6):e4‐e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic Features in Severe SARS‐CoV‐2 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2268‐2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Solomon T. Neurological infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 ‐ the story so far. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(2):65‐66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iadecola C, Anrather J, Kamel H. Effects of COVID‐19 on the Nervous System. Cell. 2020;183(1):16‐27 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manzo C, Serra‐Mestres J, Isetta M, Castagna A. Could COVID‐19 anosmia and olfactory dysfunction trigger an increased risk of future dementia in patients with ApoE4? Med Hypotheses. 2021;147:110479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ding Q, Shults NV, Gychka SG, Harris BT, Suzuki YJ. Protein Expression of Angiotensin‐Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) is Upregulated in Brains with Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long‐term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1787‐1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Semmler A, Widmann CN, Okulla T, et al. Persistent cognitive impairment, hippocampal atrophy and EEG changes in sepsis survivors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(1):62‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kennedy M, Helfand BKI, Gou RY, et al. Delirium in Older Patients With COVID‐19 Presenting to the Emergency Department. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2029540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fong TG, Jones RN, Shi P, et al. Delirium accelerates cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;72(18):1570‐1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis DH, Muniz‐Terrera G, Keage HA, et al. Association of Delirium With Cognitive Decline in Late Life: A Neuropathologic Study of 3 Population‐Based Cohort Studies. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):244‐251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Davis DH, Muniz Terrera G, Keage H, et al. Delirium is a strong risk factor for dementia in the oldest‐old: a population‐based cohort study. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 9):2809‐2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wool GD, Miller JL. The Impact of COVID‐19 Disease on Platelets and Coagulation. Pathobiology. 2021;88(1):15‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Escobar GJ, Adams AS, Liu VX, et al. Racial Disparities in COVID‐19 Testing and Outcomes : Retrospective Cohort Study in an Integrated Health System. Ann Intern Med. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dorn AV, Cooney RE, Sabin ML. COVID‐19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243‐1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang Q, Berger NA, Xu R. Analyses of Risk, Racial Disparity, and Outcomes Among US Patients With Cancer and COVID‐19 Infection. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):220‐227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Association As. Facts and Figures 2020; https://www.alz.org/alzheimers‐dementia/facts‐figures.

- 19. Association As. 2020 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2020. doi: 10.1002/alz.12068. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20. Wang QQ, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Volkow ND. COVID‐19 risk and outcomes in patients with substance use disorders: analyses from electronic health records in the United States. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(1):30‐39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kanberg N, Ashton NJ, Andersson LM, et al. Neurochemical evidence of astrocytic and neuronal injury commonly found in COVID‐19. Neurology. 2020;95(12):e1754‐e1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Virhammar J, Naas A, Fallmar D, et al. Biomarkers for central nervous system injury in cerebrospinal fluid are elevated in COVID‐19 and associated with neurological symptoms and disease severity. Eur J Neurol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shen B, Yi X, Sun Y, et al. Proteomic and Metabolomic Characterization of COVID‐19 Patient Sera. Cell. 2020;182(1):59‐72 e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diao B, Wang C, Tan Y, et al. Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Front Immunol. 2020;11:827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carvelli J, Demaria O, Vely F, et al. Association of COVID‐19 inflammation with activation of the C5a‐C5aR1 axis. Nature. 2020;588(7836):146‐150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Holter JC, Pischke SE, de Boer E, et al. Systemic complement activation is associated with respiratory failure in COVID‐19 hospitalized patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(40):25018‐25025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lindlau A, Widmann CN, Putensen C, Jessen F, Semmler A, Heneka MT. Predictors of hippocampal atrophy in critically ill patients. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22(2):410‐415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, Yusof SR, Begley DJ. Structure and function of the blood‐brain barrier. NeurobiolDis. 2010;37(1):13‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(7):673‐684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sagare AP, Sweeney MD, Makshanoff J, Zlokovic BV. Shedding of soluble platelet‐derived growth factor receptor‐β from human brain pericytes. Neurosci Lett. 2015;607:97‐101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yamazaki Y, Shinohara M, Shinohara M, et al. Selective loss of cortical endothelial tight junction proteins during Alzheimer's disease progression. Brain. 2019;142(4):1077‐1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rainey‐Smith SR, Mazzucchelli GN, Villemagne VL, et al. Genetic variation in Aquaporin‐4 moderates the relationship between sleep and brain Abeta‐amyloid burden. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8(1):47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burfeind KG, Murchison CF, Westaway SK, et al. The effects of noncoding aquaporin‐4 single‐nucleotide polymorphisms on cognition and functional progression of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;3(3):348‐359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yu B, Li C, Sun Y, Wang DW. Insulin Treatment Is Associated with Increased Mortality in Patients with COVID‐19 and Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2021;33(1):65‐77 e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Klinedinst BS, Pappas C, Le S, et al. Aging‐related changes in fluid intelligence, muscle and adipose mass, and sex‐specific immunologic mediation: A longitudinal UK Biobank study. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;82:396‐405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Willette AA, Xu G, Johnson SC, et al. Insulin resistance, brain atrophy, and cognitive performance in late middle‐aged adults. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):443‐449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Willette AA, Bendlin BB, Starks EJ, et al. Association of Insulin Resistance With Cerebral Glucose Uptake in Late Middle‐Aged Adults at Risk for Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):1013‐1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kremer S, Lersy F, de Seze J, et al. Brain MRI Findings in Severe COVID‐19: A Retrospective Observational Study. Radiology. 2020;297(2):E242‐E251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kandemirli SG, Dogan L, Sarikaya ZT, et al. Brain MRI Findings in Patients in the Intensive Care Unit with COVID‐19 Infection. Radiology. 2020;297(1):E232‐E235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coolen T, Lolli V, Sadeghi N, et al. Early postmortem brain MRI findings in COVID‐19 non‐survivors. Neurology. 2020;95(14):e2016‐e2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fontana IC, Bongarzone S, Gee A, Souza DO, Zimmer ER. PET Imaging as a Tool for Assessing COVID‐19 Brain Changes. Trends Neurosci. 2020;43(12):935‐938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zietz M, Zucker J, Tatonetti NP. Testing the association between blood type and COVID‐19 infection, intubation, and death. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Severe Covid GG, Ellinghaus D, Degenhardt F, et al. Genomewide Association Study of Severe Covid‐19 with Respiratory Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1522‐1534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zeberg H, Paabo S. A genomic region associated with protection against severe COVID‐19 is inherited from Neandertals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Inal J. Biological Factors Linking ApoE epsilon4 Variant and Severe COVID‐19. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020;22(11):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Munoz‐Fontela C, Dowling WE, Funnell SGP, et al. Animal models for COVID‐19. Nature. 2020;586(7830):509‐515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, et al. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426(6965):450‐454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Song E, Zhang C, Israelow B, et al. Neuroinvasion of SARS‐CoV‐2 in human and mouse brain. J Exp Med. 2021;218(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oblak AL, Forner S, Territo PR, et al. Model organism development and evaluation for late‐onset Alzheimer's disease: MODEL‐AD. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2020;6(1):e12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lukiw WJ, Pogue A, Hill JM. SARS‐CoV‐2 Infectivity and Neurological Targets in the Brain. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Office for National Statistics U. Updated experimental estimates of the prevalence of long COVID symptoms. 2021; https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/adhocs/12788updatedestimatesoftheprevalenceoflongcovidsymptoms.

- 52. Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, et al. 6‐month consequences of COVID‐19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. 2021;397(10270):220‐232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413‐446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]