Abstract

Little is known on how the pandemic has changed care home care delivery. The aim of this study was to explore the impact of COVID‐19 on care provision and visits in care homes from staff and family members’ perspectives. For this purpose, we conducted a telephone‐ and zoom‐based qualitative semi‐structured interview study. Care home staff and family carers of people living with dementia (PLWD) across the UK were recruited via convenience sampling and participated via telephone or online. Participants took part in a semi‐structured remote interview. Data were collected between October and November 2020. Anonymised transcripts were analysed separately by two research team members using thematic analysis, with codes discussed and themes generated jointly, supported by research team input. 42 participants (26 family carers and 16 care home staff) took part. Five themes were generated: (a) Care home reputation and financial implications; (b) Lack of care; (c) Communication or lack thereof; (d) Visiting rights/changes based on residents’ needs; (e) Deterioration of residents. With a lack of clear guidance throughout the pandemic, care homes delivered care differently with disparities in the levels and types of visiting allowed for family members. Lack of communication between care homes and family members, but also government and care homes, led to family carers feeling excluded and concerned about the well‐being of their relative. Improved communication and clear guidance for care homes and the public are required to negate the potentially damaging effects of COVID‐19 restrictions upon residents, their families and the carers who support them.

Keywords: care delivery, care homes, COVID‐19, dementia, nursing, staff

What is known about this topic?

People with dementia and family carers have been severely affected by the pandemic.

Care home closures are bad for the well‐being of residents and family members.

Social care staff is emotionally affected by the pandemic and providing care in stressful situations.

What this paper adds?

This is the first paper to explore how care delivery and visitation are affected from both family carers’ and staff’ points of views.

There is a clear lack of communication between decision makers and care homes and care homes and family members about guidance and visitation.

There is a clear dilemma between managing infection risk and providing suitable care to residents.

1. BACKGROUND

Since early 2020, COVID‐19 has caused severe disturbances in care for older adults and people with dementia (Cheung & Peri, 2020). Given the high susceptibility of older adults to the virus, care homes have been the worst affected setting in this pandemic (Liu et al., 2020). In England and Wales alone, around 20,000 COVID‐19 related deaths have been recorded amongst the care home population, although there is no consistent count since the pandemic began (Office for National Statistics [ONS], 2020).

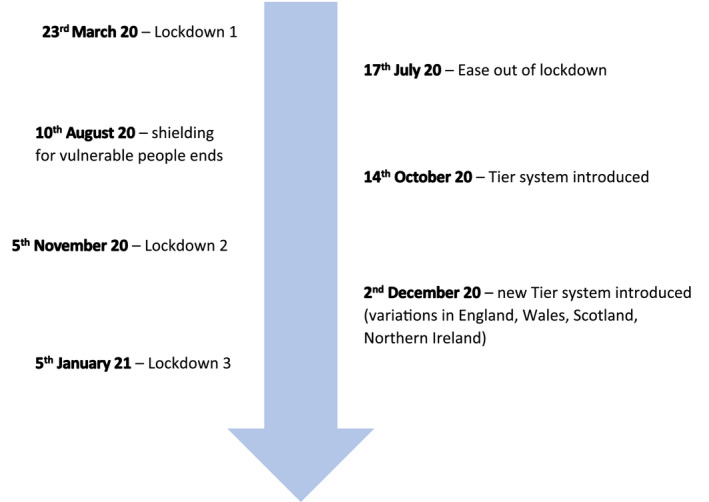

Care homes in the UK encompass both nursing homes and residential care settings without qualified nursing support. Since March 2020, rules and guidance surrounding care home visiting and testing have changed, following delays in guidance provision in the first instance. In the first 3 months of the pandemic, the majority of care homes were completely locked down and stopped access for family members. Over the summer, visiting changed and was dependent on the individual care home, without any clear understanding nationally of what was provided and how these different types of visiting were experienced. Besides care home specific changes, the UK has seen various public health restrictions implemented since March, with currently a third nationwide lockdown being imposed (see Figure 1 for further details).

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of COVID‐19 public health restrictions in the UK

Considering the large number of people in close proximity, and the frailty and age of the care home population, once COVID‐19 reached a care home it could easily spread within (Burton et al., 2020). Risk of infection was heightened further where staff worked across different care homes (Ladhani et al., 2020). In Canada, the risk of a COVID‐19 outbreak was heightened in care homes with older/non‐purposive design standards, and the extent of an outbreak was greater in for‐profit care homes, which thus also had higher levels of associated deaths (Stall et al., 2020). The risk of an outbreak further increased in larger care homes, as identified in one region of the UK (Burton et al., 2020). These patterns indicate severe concerns for infection management in care homes, especially with a lack of accessible testing in the early stages of the pandemic, and are likely to have a notable impact on current and future care home practices and visiting rights for family members.

Evidence on how care provision in care homes has been affected is very limited to date. Emerging research has shown the positive impacts of clear care home visiting guidance early on in the Netherlands, and how visits were not linked to any subsequent outbreaks (Verbeek et al., 2020). The deleterious psychosocial impact on family members has been quantified in the US, where family members of care home residents with cognitive impairment, including dementia, have reported reduced levels of well‐being as a result of the visiting restrictions, as well as poorer communication with staff (O’Caoimh et al., 2020). As Canevelli et al. (2020) highlight, it is important to provide both infection control and dementia‐sensitive care simultaneously during this ongoing pandemic. Whilst these first findings indicate an impact on the emotional well‐being of family members, it is still unclear though how the restrictions have impacted, and are impacting, on residents and staff, and how precisely care provision has changed during the pandemic in institutional long‐term care settings as opposed to community care (Giebel et al., 2020).

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of family carers and care home staff of pandemic‐related changes to care delivery and provision, by understanding the impact that risk management and infection control versus care for residents have on care delivery. Care encompasses tending to physical basic care needs, support with more instrumental activities of daily living, such as engaging in social activities, as well as ensuring the mental well‐being of residents. Although heavily covered in the media, to date there is still little scientific evidence on how care provision in care homes has been affected, and its implications for all involved. Whilst frontline health and social care staff in the UK and more globally are starting to be vaccinated now, as well as the oldest of our population and care home residents, it is important to understand the changes in care resulting from COVID‐19, and provide crucial learning for both the current and future pandemics.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

This was a qualitative semi‐structured interview study.

2.2. Sample/participants

Unpaid family carers were eligible if the person they used to care for in the community had a diagnosis of dementia, and was at the study time point, residing in a care home. Care home staff were eligible if they worked in a care home or worked solely with care homes as part of their clinical roles. All participants had to be at least 18 years of age.

Unpaid family carers and care home staff were recruited via third sector organisations such as the Liverpool Service User Reference Forum and the Lewy Body Society, many of which have existing links with care home organisations; an existing network of dementia and ageing (the Liverpool Dementia & Ageing Research Forum); and social media. This involved emailing organisations and sharing the study information, as well as posting information about the study on social media. Interested participants could contact the principal investigator via email to take part.

2.3. Data collection

Participants were asked demographic background questions and about details of the care home in which their relative resided in / they worked in. Questions included age, gender, ethnicity, total years of education, as well as details about the dementia, relationship to the person living with dementia, length of care homestay for family carers, length of working in the care home sector, job role, and care home size for care home staff.

Interview topic guides were co‐developed with current and former carers as well as clinicians and service providers, and can be found in Appendix S1. Family carers were asked about their experiences of visiting and communicating with their relative with dementia during the pandemic, and how this had changed compared to before March 2020 and severe public health measures. Care home staff was asked about how care provision and their regular working day had changed since the pandemic, how their care home was providing testing and general COVID‐19 safety measures, visiting and communications between family members and residents, the impact of the restrictions on the residents, End of Life Care arrangements, and their perceptions of working in the care sector.

Semi‐structured interviews were conducted over the phone or online via zoom and audio‐recorded between October and November 2020. Verbal consent was obtained and recorded at the beginning of each interview. Interviews lasted between 12 and 58 min, and lasted on average 30 (±11) minutes.

At the time of data collection, public health restrictions had been devolved into the four nations across the UK, with different restrictions in place in England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. In October/November 2020, the UK faced the beginning of Wave 2, and England had implemented a second lockdown from early November to early December.

2.4. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was received from the University of Liverpool (Ref: 7626) prior to study begin.

2.5. Data analysis

Anonymised transcripts were coded by research team members (CG, KH, MG, JC, SM) and one assistant psychologist, ensuring that each transcript was coded by two people. Specifically, one researcher (KH) coded all transcripts, and the second round of coding for each transcript was split across the four other team members and the assistant psychologist. This was to ensure that each transcript was coded twice, and ensured a diverse background in those who were coding the data, ensuring that all information was picked up. Data coders were experienced in conducting qualitative analysis, including academics, clinicians, and one former carer. Data were analysed using descriptive, inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), whereby emerging codes and themes about care provision and visiting were conceptualised when reading through the transcripts. Each coder went through their transcripts separately, before discussing the codes jointly. This solidified the codes amongst the team members and allowed clustering of individual codes into themes. These were discussed with all carers who were active team members to ensure identified themes reflected their real‐life experiences of caring for someone living with dementia.

2.6. Public involvement

One current and two former unpaid carers were active team members in this study. Both former carers were also currently running a third sector organisation to support carers and people living with dementia (PLWD). All three were involved in all aspects of the study, including designing study documents, attending team meetings, interpreting findings, and contributing to the dissemination. Public involvement fees were paid according to NIHR INVOLVE (2013) guidelines.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participant characteristics

A total of 42 participants were interviewed for this study (26 family carers and 16 care home staff). The majority were female (n = 31), White British (n = 35) and with a mean age of 55 (±16) years. Many participants (44%) resided in the least disadvantaged quintile (index of multiple deprivation [IMD] = 1) as reported from their postcode IMD score. Of the 26 family carers recruited, the majority were adult children (n = 16), with the remaining relations spouse or partner. The most common dementia subtype, of the PLWD residing in a care home, was Alzheimer's (n = 8), followed by Lewy Body (n = 6) and vascular dementia (n = 4). Of the 16 care home staff, the mean years of working in a care home were 9.3 (±10.6), with care assistant and manager the most common job roles (n = 4 respectively). Staff was recruited from 16 different care homes. Table 1 shows the full demographics of the recruited participants.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of family carers and care home staff

| Family carers (n = 26) | Care home staff (n = 16) | Total sample (n = 42) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 18 (69.2%) | 13 (81.3%) | 31 (73.8%) |

| Male | 8 (30.8%) | 3 (18.8%) | 11 (26.3%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White British | 22 (84.6%) | 13 (81.3%) | 35 (56.5%) |

| White Other | 2 (7.7%) | 1 (6.3%) | 3 (4.8%) |

| BAME | 2 (7.7%) | 1 (6.3%) | 3 (4.8%) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Relationship with PLWD | |||

| Spouse | 9 (34.6%) | ||

| Partner | 1 (3.8%) | ||

| Adult child | 16 (61.5) | ||

| Dementia subtype | |||

| Alzheimer's disease | 8 (30.8%) | ||

| Mixed dementia | 2 (7.7%) | ||

| Vascular dementia | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| Lewy Body dementia | 6 (23.1%) | ||

| Other | 2 (7.7%) | ||

| Unknown | 4 (15.4%) | ||

| IMD quintile a | |||

| 1 (least disadvantaged) | 11 (42.3%) | 3 (23.1%) | 14 (43.8%) |

| 2 | 4 (14.5%) | 3 (23.1%) | 2 (21.9%) |

| 3 | 0 | 3 (23.1%) | 3 (9.4%) |

| 4 | 3 (11.5%) | 1 (7.7%) | 4 (12.5%) |

| 5 (most disadvantaged) | 1 (3.8%) | 3 (23.1%) | 4 (12.5%) |

| Job role | |||

| Activity coordinator | 1 (6.3%) | ||

| Care home liaison | 1 (6.3%) | ||

| Care quality | 1 (6.3%) | ||

| Care assistant | 4 (25.0%) | ||

| Senior care assistant | 2 (12.5) | ||

| Night care assistant | 1 (6.3%) | ||

| Housekeeper | 1 (6.3%) | ||

| Matron | 1 (6.3%) | ||

| Manager | 4 (25.0%) | ||

| M (SD), [range] | |||

| Age b | 62.3 (±9.5) [42–89] | 41.8 (±16.6) [18–62] | 54.8 (±15.9) [18–89] |

| Years of education | 17.9 (±2.9) [11–23] | 15.7 (±2.7) [11–20] | 17.1 (±3.0) [11–23] |

| Care home capacity | 41.5 (±17.4) [18–76] | 42.2 (±15.8) [12–64] | 41.7 (±16.6) [12–76] |

| Years working in a care home | 9.3 (±10.6) [1–35] | ||

| Years since dementia diagnosis | 6.7 (±3.6) [2–16] | ||

| Years (PLWD) residing in a care home | 2.7 (±2.1) [1–10] | ||

Abbreviation: BAME, black and minority ethnic; IMD, index of multiple deprivation; PLWD, people living with dementia.

n = 4 missing data (IMD not generated from provided postcodes).

n = 1 care home staff = prefer not to say.

Thematic analysis identified five themes: (1) care home reputation and financial implications; (2) lack of care; (3) communication or lack thereof; (4) visiting rights changes based on residents’ needs; (5) deterioration of residents. Table 2 shows all quotes by theme.

TABLE 2.

Quotes illustrating each theme

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Care home reputation and financial implications |

“we have had some people move in but gradually we are going, at the worst we had ten empty beds which probably for a 62‐bed home doesn't sound much but you're talking about a lot of money every month and if we were private, we might have decided to cut our losses and close or sell up as a number of homes around here have.” CS6, male care home manager “there should be more money put into this industry, more funding put into the industry (people) think care workers is just there to wipe the bum, it's all about documentation, it's all about people who work, it's a lot about providing personal centred care … if people are living longer then long‐term care is needed, so more money more funding” CS12 |

|

“it's common knowledge that all nursing homes are run by a group of owners and directors and at the end of the day they've got to make money and with COVID it's, it's common sense that they need to protect their assets and the residents are their main assets, if residents die from COVID it's very quickly on the grapevine …” FC26, son “they're more worried about money and getting COVID and people dying from COVID and then losing the money than they are actually trying to promote the wellbeing of the residents, that's my feeling about it.” FC14, daughter | |

| Theme 2: Lack of care |

“I understand the COVID and I understand the difficulties of interpreting the guidance but his dementia needs I think are greater than the risks over COVID because he doesn't understand COVID and he doesn't understand most of what's going on and all he knows, well I don't know whether he does know but he's been prevented from his family. He hasn't got access to his family anymore and he's a deeply, deeply entrenched family man.” FC8, daughter “I suppose [there] is more pressure on the staff and I think that's detrimental to my wife's care.” FC5, male spouse “I was told was in an end of life situation which obviously if these antibiotics don't work it might turn into that. They obviously allow you to go in then but again you're in full PPE and you've got to keep 2 m away, so I mean this sounds awful but I said well that would be like me going and watching my mother dying … I wouldn't be comforting her I’d just be sat watching” FC10, daughter |

| Theme 3: Communication or lack thereof |

Communication from the government “the difficulty for us is we get guidance and the guidance; the guidance is written in such a way that it's guidance. It isn't these are the rules. So, we have to follow that guidance because if you don't follow that guidance potentially you could end up in a lot of trouble with commissioners and CQC. It's just the language …” CS6, male care home manager “when we went into lockdown end of March, beginning of April. The guidelines changed so much to the point that it was like everyday new guidelines, sometimes twice a day it would change … it changed to masks and then it changed to no masks, then it was mask and visors …” CS13, female care assistant “When you have an announcement on, when we did have the 5 o'clock sessions on BBC every day, all through the original pandemic and something would be said. Relatives would assume that that was an immediate action around that. But what you would find is for instance, when that announcement was made last week, we are still waiting for guidance.” CS6, male care home manager Communication between care homes and families “they started doing through the COVID weekly newsletters which are very nice and a little bit of news and pictures and painting flowers and stuff like that […] but to get that personal information that's my bug bear. So I phone up every day and I know I’m a bloody nuisance.” FC8, daughter “it took since the pandemic started, it took 6, 7 weeks for care home to know they were always telling us one story after another story, which the information wasn't accurate” FC13, son “I think there should be a newsletter that comes out every couple of weeks or just a sentence or two, this has happened or this is what we're doing. There's nothing like that you go on the website, it's a bit old.” FC23, daughter “we were in the gazebo and then they said no we've got to close it again because we have a case, but she didn't go into specifics.” FC17, daughter “it would have been nice maybe to have a Skype with a key worker, once a week or even once a fortnight to kind of say this is how your dad's been, this is what we've done, this is how his care plan's changed but we there was nothing like that really and I think there's something like that that, my dad maybe couldn't have taken part in it to say, or maybe he could.” FC11, daughter “Communication's been, I would say non‐existent. I felt that they could have kept you more informed, even if it was just twice weekly as to what was occurring, now they (care home) do have a zoom meeting once a month but I’m not particularly into zoom meetings and things like that and I imagine there's a lot of people who visit, well I know there's a lot of people who visit who are in their eighties and it's their husband or wife and they haven't got the technical ability to deal with these types of things” FC26, son “they [care home] haven't said much because I think they are a bit concerned about opening it up completely again erm they said that they are hoping that once people are vaccinated and everybody's vaccinated in the home that's when maybe they can look at letting us have a little bit more freedom of walking around the home” FC7, daughter “…we always had a relative's meetings every month, we still have those on zoom, we have one family member who would contact me every day trying to come in which was really sad … they're all quite happy at the moment because they're coming in, but they do want to come in more often but I’ve just said no because you know it's the footfall I’ve got 59 residents … every person has somebody in that's 59 people … so it's really just trying to get them to understand that.” CS2, female care home manager Remote technology not effective for residents “we tried FaceTime but again she's just not getting it so you know it's sort of again lovely to see her and like a carer would be like here's your Jo here's your Jo but she's looking at a screen but she's not seeing she's not seeing anything she's not seeing isn't seeing a person.” FC10, daughter “on FaceTime some people don't even recognise their families because they don't recognise the technology, they'll think they're looking at a photograph” CS8, female activity coordinator “after a few months or something they were looking into getting like a WhatsApp they were trying to get a tablet and that so we could do WhatsApp or Zoom calls or whatever she could see. The only thing is with my mum, we did try a couple of those but she just, she didn't register that the phone was there.” FC3, daughter “Socially, as I’ve just said, they've taken really well to technology and ways of communicating with loved ones which is going fantastic.” CS5, female care home manager |

| Theme 4: Visiting rights changes based on residents’ needs |

“they've now set up a system where my mum will be put in front of the French doors at the back of the day room and they've got a pod on the outside so my mum will be in the wall but I will be sat in the pod with a plastic screen, which isn't ideal but you know at least I’ll get to see her.” FC26, son “you take somebody's temperature, you ensure that they're in full PPE, they're escorted to the bedroom where they'd make no contact with anybody else whatsoever and the room to which they're in with that individual is safe to either be kept at a distance or obviously wearing the PPE they're able to comfort their loved one but obviously we ensure that safeguarding in place, they do not come outside of that room. They do not have interaction, they only have interaction with one member of staff who is a named member of staff.” CS5, female care home manager “so initially we had essential visitors for somebody who was end of life care and then we kind of allowed people to come in as essential visitors for people who were just unwell generally sort of for their mental health. It was very very limited, but if we felt that somebody would benefit from seeing their relative or the other way round we enable those visits.” CS2, female care home manager “I cannot praise the staff highly enough. Essentially what they said to me was look why don't you basically move in and from that point I spent about 22, 23 hr a day at the home just returning home for a shower and a change of clothes once a day … they fed me, they made sure I was comfortable, I had a reclining chair next to [PLWD]’s bed they even said look get into bed with her if you want … it was fantastic I’m sure it broke some rule” FC16, male partner “Also, residents’ rights as well has been affected, so it's how are we going to maintain and ensure that their rights are being respected, even though there's restrictions in place, not only is that, obviously quite an emotional subject for everybody, but it's also a huge paperwork exercise. We need to make sure that we are in the four corners of the Human Rights Act as well.” CS5, female care home manager “The guidance does allow us for somebody's welfare to have a visit, i.e. their mental health was deteriorating rapidly, they were at end of life or there was a safeguarding issue. Ok where somebody was maybe neglected, refusing to eat. So, we've now got an allowance to use the pod again, but we're not opening the doors on that one because I think if you're not strict on it then we'd have 60 sets of relatives wanting to come in straight away and we couldn't manage it we would actually be causing a risk to the general community I think.” CS6, male care home manager “one example I would refer to is the manager, the acting services team manager when she says that video consultations at this present stage is the right strategy to undertake for family members to keep in contact with their relative. But surely when I was driving through with my brother there were patients, there were other family members who were visiting their relatives. So, some members in the care home were given access to their relatives, whereas our family we were not given access so I don't know why that would be, is it due to health grounds.” FC13, son “I’m just hoping that they're not going to rush it [allowing visits] and they're going to take it area by area by area and look at it that way erm yeah 'cause we haven't got a lot of residents anymore unfortunately so we are going to have to start bringing more in and that increases the risk and then if their relatives come and everybody else's are coming inside” CS1, female housekeeper |

| Theme 5: Deterioration in residents |

“I'm just thinking about this one lady, she stopped eating when her husband didn't come every day and then was only eating when our male nurses, when our male carers were on.” CS1, female housekeeper “there probably will actually be more deaths because even the people who have recovered they've lost so much weight from not eating and the COVID that they've gone so so frail now.” CS8, female activity coordinator “her family which she's not getting so I would imagine well I think there's a decline in her mental capacity which might I mean I don't know it might have happened anyway as a natural progression but you know I don't know because I’m still not seeing her so I don't know really.” FC10, daughter “[Skype] enabled me to look at her and go in fact she had a delirium. This is not her dementia this is not her normal and I can say that to you because we've been talking to her on Skype practically every day actually since lockdown so we know what she was like yesterday and what she was like the day before so that's an example of having to navigate and negotiate incredibly difficult visiting restrictions about how can we work out what the best thing is to do for her at this time.” FC25, daughter |

Abbreviation: PLWD, people living with dementia; PPE personal protective equipment.

3.2. Theme 1: Care home reputation and financial implications

Both family carers and some care home staff raised concern about the reputation of many care homes by reporting COVID‐19 cases, and their implications on their financial future and survival. Care home staff was not only concerned about having the virus in for obvious health reasons but also what having and reporting COVID‐19 cases might do to the home's reputation and willingness of people in need of institutional long‐term care choosing a care home with an infection outbreak. For this reason, many care homes were particularly stringent with rules and regulations, with family carers expressing their dissatisfaction of being unable to see their relative despite being prepared with personal protective equipment (PPE) and adhering to social distancing and other measures.

In contrast, family carers were concerned about the well‐being of the relatives residing in the care homes, with some feeling that care homes prioritised their reputation and income over the residents’ well‐being.

3.3. Theme 2: Lack of care

Some family carers suggested reductions of care for their relative during the pandemic. Carers were mindful of the additional workload and job intensity for care home staff and considered that to be one of the reasons why care home staff were less able to focus on the individual's care. It is to be noted that not all family carers reported reduced quality of care, yet questioned the regulations and delivery of guidance by care home staff in not enabling face‐to‐face visiting due to the detrimental impact on the residents. Being unable to see family and have regular social contact was seen to be a lack of care in its own right.

Visiting regulations seemed to be different in end of life scenarios, but to have to reach these before restrictions were relaxed was not desirable for anyone and family carers wanted to see their relatives before end of life care was initiated.

3.4. Theme 3: Communication or lack thereof

3.4.1. Communication from the government

Both care home staff and family carers experienced minimal communication from the government surrounding guidance. Even when new guidance was announced in the media, there was a delay in detailed guidance being circulated to care homes, so that care home staff faced additional difficulties in that period when family carers expected changes to take place immediately.

3.4.2. Communication between care homes and families

There were mixed experiences surrounding communication between care homes and family carers, with many reporting positive experiences by receiving regular newsletters, at least at the beginning of the pandemic. Whilst many family carers would have wanted more regular communication and updates about their relatives, many trusted care home staff in informing them if anything important was happening. Others also noted that they were repeatedly told similar information about their relative, making carers suspicious of the information provided by care home staff.

With constantly changing regulations, many family carers experienced sudden changes in visiting rights without having had sufficient information about these in advance, which caused distress to carers.

Family carers also missed being able to talk to care home staff about their relatives, as could normally be done pre‐pandemic. This would have provided them with more information about their relative, especially when remote technology was not working for residents and caused difficulties.

3.4.3. Remote technology not effective for residents

Care homes tried to enable communication between residents and family carers via remote technology, including Skype and FaceTime. This seemed to be more for the benefit of family carers though, as residents often appeared to be unable to comprehend remote technology and seeing their relatives through a screen, amplified by the cognitive difficulties those people with dementia experience. Most older adults were unfamiliar with remote technology in the first place and were only introduced to it through the pandemic, and with severe cognitive deficits for many, they were unable to process this form of communication.

One care home staff member acclaimed remote communication without noting any comprehension difficulties from care home residents. However, this was unlike other participants’ experiences and highlights either a rare exception or unwillingness to share negative experiences about care delivery.

3.5. Theme 4: Visiting rights changes based on residents’ needs

Most visits, if they occurred, took place via window visits, garden visits, or via purposefully‐built pods. However, face‐to‐face visiting overall was significantly reduced/ non‐existent in many cases compared to before the pandemic. This included that family carers were not allowed to enter the care home. One care home, however, allowed family carers to continue to enter the care home by wearing full PPE and was directed by staff to the resident's room where they were allowed to remain for the duration of the visit.

This differed for residents considered to be at the end of life, where family carers were allowed to spend more time with relatives in the care home. In some instances, care home staff in some ways allowed physical contact and holding hands at the end of life, as staff was not watching over the end of life visits and felt inhumane disallowing a family member to hold their dying relative's hand.

Between August and September 2020, lockdown restrictions continued to ease in the UK, meaning care home staff could make adaptations to visiting rights. However, when presented with this opportunity, it seemed some staff remained more concerned with infection control measures to keep COVID out of the homes, and so visiting changes were not observed by many of the family carers at this time. Where care homes did alter visiting abilities to meet these new changes in policy, it was found that adapted visitation was not possible for all residents due to their variable needs, and so some staffs were worried that they would be inundated with requests for visitation from all residents’ families if they made adaptions for a small number of residents. The multiple factors that had to be considered by individual homes when deciding how and when to safely adapt visits for families presented moral dilemmas for the care staff.

With some families being allowed to see their relative in the care homes, others were left out and were complaining about the different allowances made, whilst they were told specifically that they were not allowed to visit their relative.

3.6. Theme 5: Deterioration in residents

Care home staff and family carers noted deteriorations in residents, both in physical and mental well‐being. With most family carers rarely seeing their relative either face‐to‐face or remotely, they often noted severe deteriorations when they eventually saw their relative.

Care home staff further reported that some residents were upset about not being able to see their family, which is why they were often allowed to see their family members as outlined in Theme 4. This was noted in behavioural disturbances in residents and a loss of appetite, leading to physical deteriorations. Carers noted that these changes may be due to dementia and may have occurred regardless of COVID‐19 public restrictions, however they were considered more difficult to manage due to the restrictions.

4. DISCUSSION

As the first study to have explored the impact of COVID‐19 on care provision in institutional long‐term care settings, this study highlights the moral dilemma of providing care during the pandemic and its impact on family members by showing a trade‐off between managing infection risk versus adequate care for residents.

Care home staff faced substantial difficulties in adapting their care to newly imposed public health measures to keep residents, and themselves, safe, with communication on various levels in most instances not being effective. This included communication from the government to care homes about clear, timely, guidance, as well as communication between care home staff and residents with family members. The virus has caused an unprecedented situation worldwide, and staff felt mostly unclear on how to deal with the virus in the first instance, with some care homes having closed down before the national lockdown. Whilst the Netherlands, for example, was the first country to provide clear care home visiting guidance in May 2020 (Verbeek et al., 2020), care homes in the UK still provided their own systems of visiting, if any at all, with no central guidance from the government until later in 2020.

This lack of communication to care homes contributed to a moral dilemma of how care was provided in many instances, with some staff adhering to very strict guidelines of not allowing any family members to visit, even via windows or outside in the garden, whilst others took account of the mental health of residents and adapted access to family members accordingly. This was also influenced by End of Life Care situations, where family members received greater visiting rights. To date, it appears that no research has yet captured the decisions that care home staff is facing in how to adapt the care for residents during the pandemic. Considering the high infection rates in care homes and death toll of the virus if restrictions are not adhered to (Burton et al., 2020), limiting forms of social contact are an important part of stemming the spread/ risk of the virus. However, as population‐based evidence is emerging on the detrimental impact of lack of social contact and isolation during the pandemic on people's mental health (Fancourt et al., 2020; Giebel et al., 2020; White & van der Boor, 2020), these consequences need to be equally considered within the care home sector. Specifically, PLWD are found to deteriorate faster during home confinement and lockdowns in the community (Borges‐Machado et al., 2020; Giebel et al., 2020), which is reflected in care home residents with dementia, as our study indicates. Therefore, it is vital that family members are allowed to see their relatives face‐to‐face on a regular basis, whilst adhering to public health measures to prevent virus transmission. An alternative, which has been tested recently in parts of the UK, was completing multiple lateral flow tests that take a short time to confirm whether someone has contracted COVID‐19. However, these tests were found to miss nearly half of affected COVID‐19 cases (Wise, 2020), therefore adhering to full PPE and social distancing measures may be more feasible until the vaccination of all care home residents and staff.

Some staff adapted visiting rules for residents where they noticed a negative impact on the resident's mental health, allowing family members to visit, or visit more frequently. This is in contrast to the strict adherence to rules by many staff, who put the physical health from suffering COVID‐19 above the wider mental health of residents, without making care decisions on an individual basis. Besides the desire to reduce the chances of infection in the care home, it appears that staff may also be wary of the national care home ratings if they were to have COVID‐19 cases and subsequent future income from new residents. Besides this financial and reputational angle, the low levels of general training which UK care workers mostly receive and limited evidence‐based personal care practice may also be to blame (Fossey et al., 2014). This pandemic has caused enormous pressures and sudden changes to the care home sector, and many staff may have been ill‐equipped in handling these and making well‐considered care decisions without having had sufficient training in the first place and with a lack of clear guidance, leading to burnout (Padros et al., 2021). Support for this argument comes from the Netherlands, a country often lauded for its advanced care and social care sector. The Netherlands was the first country to implement clear care home visiting guidance (Verbeek et al., 2020), but its care workforce in general is more highly trained than care workers in the UK, providing them a potential advantage in facing a care crisis and adapting care swiftly to the benefit, and not a sole detriment, of residents. Our findings illustrate the practical and moral balancing of different priorities and risks. Apart from the fear of damaging publicity from outbreaks, there is also evidence of setting the rules for reducing risks of outbreaks and transmission of COVID‐19 with lack of hard research evidence to guide protocols thus tending to err on caution; against psychosocial and thus physical well‐being of residents and emotional needs of relatives.

To overcome the issue of reduced social engagement with family members, care homes implemented remote communication between residents and family members, although often with limited success. In some instances, the staff was very supportive however and enabled daily skype calls. As noted in recent evidence emerging from the pandemic, remote technology is difficult to utilise for older adults and particularly those living with dementia (Hill et al., 2015). Findings from this study therefore further corroborate the limited previous evidence base, by providing first insights into the care home sector. Remote technology communication, such as FaceTime, appeared to be of greater benefit to family members, as residents mostly failed to comprehend that they were seeing their family members on the screen, with some using it as a mirror instead, looking at themselves. Interestingly, some care home staff perceived that residents had dealt with remote communication well, whilst all family carers stated the opposite. This again may indicate that some care home staff may have not disclosed the full picture of the impact of the pandemic on its residents, for fear of their home's reputation. Further evidence is therefore required to highlight the efficacy of remote communication and informed assessment of needs and suitability of different modes for different residents reflecting their cognition and emotional states.

4.1. Limitations

Whilst benefitting from a large qualitative sample with varied and rich data, from multiple different perspectives, this study is subject to some limitations. The recruitment strategy of convenience sampling via support service organisations and social media amongst others may have led to a self‐selecting bias with many family carers with negative experiences wanting to share their stories. However, some carers also reported some less negative stories. The highly topical nature of the study led to us having to decline over 30 family carers from taking part due to over‐recruitment within a short space of time. Recruitment for care home staff on the other hand was more difficult, which is likely to be due to the large workloads of staff during the pandemic and thus restraints for time. Nevertheless, we were able to interview 16 care home staff members with different experiences. Amongst the sample and its representativeness, one further limitation was limited ethnic diversity. Whilst precise statistics on the ethnic make‐up of the care home population are missing (ONS, 2014), research into dementia care in ethnic minority groups indicates that many are cared for by their families, also for fear of stigma, and thus less likely to enter a care home (Baghirathan et al., 2018; Giebel et al., 2015). Information on the adult social care workforce is limited also, with recent data highlighting only that 7% were EU nationals, and 9% non‐EU nationals, yet no detail on their ethnic background (Skills for Care, 2020). Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising to see little ethnic diversity in our study, although future research should specifically address this limitation.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The pandemic has resulted in significant changes in care delivery across care homes, with staff trying to balance effective infection control and ensuring the mental, emotional, and physical well‐being of residents. With vaccines slowly being rolled out in some countries, the pandemic will still stay around for some time, during which it is important for clear guidance to be communicated to care home staff and family members, ensuring the right level of care and levels of social contact are adhered to and enabled. Understanding institutional and individual responses to these situations and subsequent choices and decisions will inform future balance‐setting between different risks and solutions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CG, PM, MG, HT, JS, JC, KH, SM, MR conceptualised the study. CG managed the study, collected and analysed data, and drafted the manuscript. KH collected and analysed data. JC, SM, and MG analysed data. All co‐authors interpreted the findings jointly, read drafts of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank all family carers and care home staff who took part in this study, and we also wish to thank the many family carers who expressed an interest to take part after we were already booked up. We also wish to thank Maxine Martine and Lynne McClymont for transcribing the audio files very swiftly to analyse the data in time.

Giebel, C. , Hanna, K. , Cannon, J. , Shenton, J. , Mason, S. , Tetlow, H. , Marlow, P. , Rajagopal, M. , & Gabbay, M. (2021). Taking the ‘care’ out of care homes: The moral dilemma of institutional long‐term care provision during COVID‐19. Health & Social Care in the Community, 00, 1–10. 10.1111/hsc.13651

Funding information

This study was funded by the Geoffrey and Pauline Martin Trust, with funding awarded to the principal investigator. This is also independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast (ARC NWC). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Baghirathan, S. , Cheston, R. , Hui, R. , Chacon, A. , Shears, P. , & Currie, K. (2018). A grounded theory analysis of the experiences of carers for people living with dementia from three BAME communities: Balancing the need for support against fears of being diminished. Dementia. 10.1177/2F1471301218804714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Borges‐Machado, F. , Barros, D. , Ribeiro, O. , & Carvalho, J. (2020). The effects of COVID‐19 home confinement in dementia care: Physical and cognitive decline, severe neuropsychiatric symptoms and increased caregiving burden. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementiasr, 35, 153331752097672. 10.1177/1533317520976720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton, J. , Bayne, G. , Evans, C. , Garbe, F. , Gorman, D. , Honhold, N. , McCormick, D. , Othieno, R. , Stevenson, J. E. , Swietlik, S. , Templeton, K. E. , Tranter, M. , Willocks, L. , & Guthrie, B. (2020). Evolution and effects of COVID‐19 outbreaks in care homes: A population analysis in 189 care homes in one geographical region of the UK. LANCET Healthy Longevity, 1(1), E21–E31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canevelli, M. , Bruno, G. , & Cesari, M. (2020). Providing simultaneous COVID‐19 sensitive and dementia‐sensitive care as we transition from crisis care to ongoing care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(7), 968–969. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G. , & Peri, K. (2020). Challenges to dementia care during COVID‐19: Innovations in remote delivery of group cognitive stimulation therapy. Aging & Mental Health. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1789945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt, D. , Steptoe, A. , & Bu, F. (2020). Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID‐19 in England: A longitudinal observational study. LANCET Psychiatry. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossey, J. , Masson, S. , Stafford, S. , Lawrence, V. , Corbett, A. , & Ballard, C. (2014). The disconnect between evidence and practice: A systematic review of person‐centered interventions and training manuals for care home staff working with people with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(8), 797–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel, C. , Cannon, J. , Hanna, K. , Butchard, S. , Eley, R. , Gaughan, A. , Komuravelli, A. , Shenton, J. , Callaghan, S. , Tetlow, H. , Limbert, S. , Whittington, R. , Rogers, C. , Rajagopal, M. , Ward, K. , Shaw, L. , Corcoran, R. , Bennett, K. , & Gabbay, M. (2020). Impact of COVID‐19 related social support service closures on people with dementia and unpaid carers: A qualitative study. Aging & Mental Health. 10.1080/13607863.2020.1822292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel, C. M. , Zubair, M. , Jolley, D. , Bhui, K. S. , Purandare, N. , Worden, A. , & Challis, D. (2015). South Asian older adults with memory impairment: Improving assessment and access to dementia care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(4), 345–356. 10.1002/gps.4242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, R. , Betts, L. R. , & Gardner, S. E. (2015). Older adults’ experiences and perceptions of digital technology: (Dis)empowerment, wellbeing, and inclusion. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 415–423. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ladhani, S. N. , Chow, J. Y. , Janarthanan, R. , Fok, J. , Crawley‐Boevey, E. , Vusirikala, A. , Fernandez, E. , Perez, M. S. , Tang, S. , Dun‐Campbell, K. , Wynne‐Evans, E. , Bell, A. , Patel, B. , Amin‐Chowdhury, Z. , Aiano, F. , Paranthaman, K. , Ma, T. , Saavedra‐Campos, M. , Myers, R. , … Ramsay, M. E. (2020). Increased risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in staff working across different care homes: Enhanced COVID‐19 outbreak investigations in London care homes. Journal of Infection, 81(4), 621–624. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M. , Maxwell, C. J. , Armstrong, P. , Schwandt, M. , Moser, A. , McGregor, M. J. , Bronskill, S. E. , & Dhalla, I. A. (2020). COVID‐19 in long‐term care homes in Ontario and British Colombia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(47), E1540–E1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health Research INVOLVE . (2013). Values, principles and standards for public involvement in research. NIHR. [Google Scholar]

- O'Caoimh, R. , O'Donovan, M. R. , Monahan, M. P. , Dalton O'Connor, C. , Buckley, C. , Kilty, C. , Fitzgerald, S. , Hartigan, I. , & Cornally, N. (2020). Psychosocial impact of COVID‐19 nursing home restrictions on visitors of residents with cognitive impairment: A cross‐sectional study as part of the engaging remotely in care (ERiC) project. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.585373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) . (2014). Changes in the older resident care home population between 2001 and 2011. ONS. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) . (2020). Deaths involving COVID‐19 in the care sector, England and Wales: Deaths occurring up to 12 June 2020 and registered up to 20 June 2020. ONS. [Google Scholar]

- Padros, A. B. N. , Garcia‐Tizon, S. J. , & Melendez, J. C. (2021). Sense of coherence and burnout in nursing home workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Spain. Health & Social Care in the Community. 10.1111/hsc.13397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skills for Care . (2020). The state of the adult social care sector and workforce in England. Skills for Care. www.skillsforcare.org.uk/stateof [Google Scholar]

- Stall, N. M. , Jones, A. , Brown, K. A. , Rochon, P. A. , & Costa, A. P. (2020). For‐profit long‐term care homes and the risk of COVID_19 outbreaks and resident deaths. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 192(33), E946–E955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, H. , Gerritsen, D. L. , Backhaus, R. , de Boer, B. S. , Koopmans, R. T. C. M. , & Hamers, J. P. H. (2020). Allowing visitors back in the nursing home during the COVID‐19 crisis: A Dutch national study into first experiences and impact on well‐being. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(7), 900–904. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, R. , & van der Boor, C. (2020). Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic and initial period of lockdown on the mental health and well‐being of adults in the UK. Bjpsych Open, 6(5), E90. 10.1192/bjo.2020.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise, J. (2020). Covid‐19: Lateral flow tests miss over half of cases, Liverpool pilot data show. British Medical Journal, 371, m4848. 10.1136/bmj.m4848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.