Abstract

Aim

Our aim was to describe the outcomes of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C) associated with COVID‐19.

Methods

This national, population‐based, longitudinal, multicentre study used Swedish data that were prospectively collected between 1 December 2020 and 31 May 2021. All patients met the World Health Organization criteria for MIS‐C. The outcomes 2 and 8 weeks after diagnosis are presented, and follow‐up protocols are suggested.

Results

We identified 152 cases, and 133 (87%) participated. When followed up 2 weeks after MIS‐C was diagnosed, 43% of the 119 patients had abnormal results, including complete blood cell counts, platelet counts, albumin levels, electrocardiograms and echocardiograms. After 8 weeks, 36% of 89 had an abnormal patient history, but clinical findings were uncommon. Echocardiogram results were abnormal in 5% of 67, and the most common complaint was fatigue. Older children and those who received intensive care were more likely to report symptoms and have abnormal cardiac results.

Conclusion

More than a third (36%) of the patients had persistent symptoms 8 weeks after MIS‐C, and 5% had abnormal echocardiograms. Older age and higher levels of initial care appeared to be risk factors. Structured follow‐up visits are important after MIS‐C.

Keywords: abnormal echocardiograms, fatigue, intensive care, outcomes, persistent symptoms

Abbreviations

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- ICU

intensive care unit

- MIS‐C

multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Key Notes.

This was a national, population‐based, longitudinal, multicentre study of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C) associated with COVID‐19.

Swedish data were prospectively collected from 1 December 2020 to 31 May 2021, 2 and 8 weeks after the children's MIS‐C diagnosis.

Most of the 133 children had clinically recovered 8 weeks after their MIS‐C diagnosis, but 36% still complained of symptoms and 5% had abnormal echocardiograms.

1. INTRODUCTION

In April 2020, reports from several countries warned of the increased frequency of a hyperinflammatory condition, which had affected children who had contracted the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). 1 , 2 The condition was named multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C), and it has been defined by the World Health Organization. In short, affected children or adolescents must have fever, symptoms and laboratory features suggesting MIS‐C and a history of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Other disorders must be excluded. 3

The complexity of the disease presentation and treatment strategies has been described in many publications, 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 but comprehensive reports on the long‐term outcomes are lacking. 8 , 9 The first follow‐up studies of MIS‐C patients were published in 2021. 10 , 11 , 12 All three studies were relatively small and represented a selection of MIS‐C cases. Most patients achieved good resolution of their somatic symptoms. However, the most comprehensive study, of 46 patients, 10 demonstrated emotional or psychosocial stress, as well as reduced exercise capacity after 6 months. To our knowledge, no further evidence or experience has so far been presented on risk factors for organ‐specific outcomes or how follow‐up visits should be managed in terms of content and duration. This highlights the fundamental need for large, population‐based, follow‐up studies of children recovering from MIS‐C.

The aim of this prospective, Swedish population‐based, study was to present nationwide follow‐up data at 2 and 8 weeks after a MIS‐C diagnosis. In addition, we wanted to describe the patients’ symptoms and clinical examinations at follow‐up, by age‐ and care‐level groups. These results could then be used to discuss the appropriate duration and content of MIS‐C follow‐up programmes.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

This was a longitudinal prospective population‐based multicentre study of Swedish children with MIS‐C from 1 December 2020 to 31 May 2021. When the first Swedish cases emerged in May 2020, the Swedish Paediatric Rheumatology Association initiated biweekly national online meetings for physicians involved in the care of patients with MIS‐C. The purpose of the meetings was to report on the incidence and to discuss the management and outcomes of patients affected by this new disease entity. To ensure complete national coverage, mandatory reporting of MIS‐C cases to the Swedish Paediatric Rheumatology Registry (the Registry) was implemented as soon as cases started to emerge. The first Swedish clinical guidelines on the treatment and management of MIS‐C were published in June 2020. 13 It was quickly recognised that patients with MIS‐C also needed to be seen after hospital discharge and national guidelines for structured follow‐up visits were published in December 2020. 14 These recommended clinical assessments by physicians at 2 and 8 weeks and 6, 12, 18 and 24 months after a MIS‐C diagnosis. Heart examinations were recommended at 2 and 8 weeks and neuropsychiatric screening at 6 and 12 months.

2.2. Study population

By 31 May 2021, 243 Sweden cases of MIS‐C had been reported to the Registry. All patients were under 18 years of age at diagnosis and fulfilled the World Health Organization case definition for MIS‐C. The follow‐up programme was not nationally standardised until 1 December 2020, and 66 patients diagnosed before this date were excluded from our study cohort. Oral and written consent was provided, so that the pseudonymised data of 152 of the 177 patients registered with MIS‐C from 1 December 2020 to 31 May 2021 could be shared for research purposes. If the patient was under 15 years of age, this consent was provided by a parent or guardian (Figure S1).

2.3. Data sources and variables

The electronic Registry contains prospectively collected data on Swedish cases of paediatric rheumatology diseases since 2009. 15 It can be connected to medical patient charts via the personal identity number that is issued to all Swedish residents at birth or immigration. 16 In 2020, a new custom‐made interface was designed for the Registry so that all Swedish MIS‐C cases could be entered, in order to create a population‐based cohort for quality control and research purposes. In addition to including patients with MIS‐C at baseline, it is mandatory to file a report for every outpatient visit after they are discharged.

A wide range of information was extracted from the Registry. This included the baseline demographic data, the date of the MIS‐C diagnosis and the results of the SARS‐CoV‐2 polymerase chain reaction test and serum immunoglobulin G antibodies to SARS‐CoV‐2. It also included the level of care the patient received, namely outpatient, general ward, intensive care unit (ICU) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) unit. The symptoms and signs at presentation that were extracted were as follows: fever, diarrhoea, vomiting, abdominal pain, lethargy, oedema, affected mucus membranes, dyspnoea, encephalopathy, seizures, irritability, non‐purulent conjunctivitis, scaly skin, reddened lips, headache, sore throat, cough, joint pain, lymphadenopathy and rashes. We also extracted electrocardiogram and echocardiogram results and laboratory results, namely the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (highest value before treatment in mm/h), albumin (lowest value in g/L), troponin I/T (highest value in ng/L) and N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (highest value in ng/L). Information was also collected from the Registry on the outpatient visits 2 and 8 weeks after diagnosis, including the dates of the visits and the patient history and complaints. The physical examination comprised the following: mouth and mucus membranes, lymph nodes on the throat and neck, heart auscultation, lung auscultation, blood pressure, palpation of the abdomen, skin and joints. The laboratory results were as follows: complete blood cell counts (n/109/L), platelet counts (n/109/L), albumin, ferritin (μg/L) D‐dimers (mg/L) and fibrinogen equivalent units, electrocardiograms and echocardiograms. All the follow‐up variables were categorised by the reporting physician as normal, abnormal or not examined. If the patient's history was described as abnormal, we collected the reported symptoms and signs.

2.4. Measurement bias

An invitation to contribute patients to the study was issued to all Swedish paediatric clinics, and reminders were sent by email and discussed during regular online meetings, to avoid missed cases. Data were prospectively collected in the Registry at the time of each follow‐up visit. Time points at the follow‐up visits varied slightly, according to the availability of slot times for the appointments. Visits that occurred 6–28 days after the MIS‐C diagnosis were considered 2‐week follow‐up visits, and visits occurring at 6–12 weeks after diagnosis were considered 8‐week visits. Due to practical and administrative reasons, 14 children had follow‐up data at 8 weeks but not at 2 weeks. To avoid inter‐user variability and measurement bias, the follow‐up forms were short, predetermined and easy to fill in. This also minimised the amount of missing data and dropouts.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Descriptive data are presented as numbers and percentage for categorical variables and as means and standard deviations (SD) for continuous variables. Microsoft Excel 2019 (Microsoft Corp, Washington, USA) was used for the analyses. This study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority.

3. RESULTS

We received responses from 14 of the 21 Swedish regions and these covered 152 patients, which was 75% of the paediatric patients diagnosed with MIS‐C during the study period (Figure S1). There were 19 patients (13%) with incomplete follow‐up data at the date of the data extraction, and they were excluded from analyses (Figure S1). The mean age of the remaining 133 patients (61% boys) was 9.3 years, and the children were divided into three age groups. Just over a quarter (28%) were aged 0–6 years, which is preschool age in Sweden, 45% were aged 7–12 years, and 27% were aged 13–18 years.

Baseline data from the initial hospitalisation are presented in Table 1. During the acute phase, 36% of the patients tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 by polymerase chain reaction or antigen test and 80% tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies. The most common symptom at presentation was fever (99%), followed by abdominal pain (70%) and a rash (51%). An echocardiography was performed on 122 (92%) children during the acute phase, and 19% of these had decreased ejection fraction, and 16% had coronary artery involvement. Pericardial effusion and arrhythmia were less common. Most of the patients were cared for in a general paediatric ward and only 16% needed to be admitted to the ICU, including one who needed ECMO (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline data for the Swedish MIS‐C cohort 1 December 2020 to 31 May 2021

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Patient characteristics (n = 133) | |

| Total cohort, mean age in years | 9.3 ± 4.3 |

| 0–6 years | 37 (28) |

| 7–12 years | 60 (45) |

| 13–18 years | 36 (27) |

| Male | 80 (61) |

| SARS‐CoV−2 testing (n = 133) | |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 antigen or PCR test positive | 46 (36) |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies positive | 107 (80) |

| Symptomatology (n = 133) | |

| Fever | 132 (99) |

| Diarrhoea | 58 (44) |

| Vomiting | 72 (55) |

| Abdominal pain | 94 (70) |

| Lethargy | 40 (30) |

| Oedema | 25 (19) |

| Affected mucus membranes | 12 (9) |

| Dyspnoea | 11 (8) |

| Encephalopathy | 5 (4) |

| Seizures | 2 (2) |

| Irritability | 16 (12) |

| Non‐purulent conjunctivitis | 69 (52) |

| Scaly skin | 6 (5) |

| Reddened lips | 22 (17) |

| Headache | 56 (42) |

| Sore throat | 22 (16) |

| Cough | 9 (7) |

| Joint pain | 8 (6) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 26 (20) |

| Rash | 67 (51) |

| Cardiology (n = 122) | |

| Decreased ejection fraction | 23 (19) |

| Abnormal coronary arteries | 20 (16) |

| Pericardial effusion | 11 (9) |

| Arrhythmia | 6 (5) |

| Level of care (n = 133) | |

| General ward or outpatient care only | 111 (83) |

| Intensive care unit or ECMO unit | 21 (16) |

| Laboratory analyses | Mean |

| ESR, highest value (SD, mm/h, n = 107) | 53.2 (24.8) |

| Albumin, lowest value (SD, g/L, n = 122) | 23.5 (4.6) |

| Troponin I/T, highest value (SD, ng/L, n = 115) | 75.2 (155) |

| NT‐ProBNP, highest value (SD, ng/L, n = 122) | 5735 (6994) |

Abbreviations: ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; MIS‐C, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children; NT‐ProBNP, N‐terminal proB‐type Natriuretic peptide; PCR, polymerase chain reaction, SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SD, standard deviation.

3.1. Two‐week follow‐up visit

There were 119 children who were followed up 2 weeks after their MIS‐C diagnosis: 28% were 0–6 years old, 46% were 7–12 years old, and 26% were 13–18 years old. The physicians reported that 43% of the patient histories were abnormal, but clinical findings were uncommon. The exceptions were skin changes or rashes, which were seen in 15%. The most common abnormal laboratory results during these visits were the complete blood counts, platelet counts and albumin levels. Just under three‐quarters (71%) of the patients underwent an electrocardiogram, and five (6%) of these were abnormal: one child aged 0–6 and four teenagers aged 13–18. In addition, 74% of the 119 children underwent an echocardiography and 14 (16%) of these were abnormal (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Two‐week follow‐up after multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS‐C) in Swedish children

|

Reported cases n |

Abnormal findings n (%) |

0–6 years n (%) |

7–12 years n (%) |

13–18 years n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow‐up visits | 119 | 33 (28) | 55 (46) | 31 (26) | |

| Clinical findings | |||||

| Patient history | 119 | 51 (43) | 12 (36) | 23 (42) | 16 (52) |

| General appearance | 119 | 3 (3) | 0 | 1 (2) | 2 (6) |

| Mouth and mucus membranes | 116 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymph nodes | 115 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heart auscultation | 116 | 2 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Lung auscultation | 117 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abdomen | 116 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Joints | 112 | 3 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 2 (7) |

| Skin | 116 | 17 (15) | 3 (10) | 8 (15) | 6 (20) |

| Pulse | 111 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blood pressure | 104 | 7 (7) | 0 | 3 (6) | 4 (14) |

| Growth | 115 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Laboratory findings | |||||

| Complete blood cell count | 114 | 51(45) | 14 (44) | 23 (44) | 14 (47) |

| Platelet count | 114 | 53 (46) | 14 (45) | 24 (46) | 15 (50) |

| Albumin | 112 | 33 (29) | 6 (19) | 18 (35) | 9 (30) |

| Ferritin | 103 | 26 (25) | 2 (7.4) | 16 (33) | 8 (29) |

| D‐dimer | 98 | 14 (14) | 4 (17) | 8 (17) | 2 (8) |

| Cardiology | |||||

| Electrocardiogram | 85 | 5 (6) | 1 (4) | 0 | 4 (17) |

| Echocardiography | 88 | 14 (16) | 6 (26) | 4 (10) | 4 (16) |

3.2. Eight‐week follow‐up visit

There were 89 children who were followed up 8 weeks after diagnosis: 27% were 0–6 years old, 48% were 7–12 years old, and 25% were 13–18 years old. The physicians reported that 36% of the patient histories were abnormal, but clinical findings were uncommon. The exception was three teenagers who displayed abnormal findings during the joint examination. Abnormal growth was noted in six children aged 7–12 years. The most common abnormal laboratory values 8 weeks after MIS‐C were the complete blood count and ferritin levels in general and abnormal platelet counts in 50% of the children aged 0–6. During this visit, 72% of the patients underwent an electrocardiogram and 2 (3%) of these were abnormal. In addition, 75% had an echocardiography and 3 (5%) of these were abnormal (Table 3). These children had already presented with abnormal electrocardiogram or echocardiogra findings during the previous 2‐week visit and no new cases presented during the 8‐week visit (Figure S2).

TABLE 3.

Eight‐week follow‐up after multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS‐C) in Swedish children associated with COVID‐19

|

Reported cases n |

Abnormal findings n (%) |

0–6 years n (%) |

7–12 years n (%) |

13–18 years n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow‐up visits | 89 | 24 (27) | 43 (48) | 22 (25) | |

| Clinical findings | |||||

| Patient history | 89 | 32 (36) | 11 (46) | 13 (30) | 8 (36) |

| General appearance | 87 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mouth and mucus membranes | 85 | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Lymph nodes | 85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heart auscultation | 87 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lung auscultation | 86 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abdomen | 85 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Joints | 84 | 3 (4) | 0 | 0 | 3 (14) |

| Skin | 84 | 4 (5) | 1 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (10) |

| Pulse | 85 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Blood pressure | 77 | 4 (5) | 0 | 3 (8) | 1 (5) |

| Growth | 86 | 7 (8) | 0 | 6 (14) | 1 (5) |

| Laboratory findings | |||||

| Complete blood cell count | 69 | 10 (15) | 2 (11) | 5 (15) | 3 (17) |

| Platelet count | 73 | 15 (21) | 9 (50) | 6 (19) | 0 |

| Albumin | 66 | 2 (4) | 1 (5) | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Ferritin | 69 | 10 (14) | 2 (11) | 4 (13) | 4 (21) |

| D‐dimer | 60 | 5 (8) | 1 (7) | 3 (11) | 1 (6) |

| Cardiology | |||||

| Electrocardiogram | 64 | 2 (3) | 1 (6) | 0 | 1 (6) |

| Echocardiography | 67 | 3 (5) | 0 | 2 (7) | 1 (5) |

3.3. Patient complaints at 2 and 8 weeks

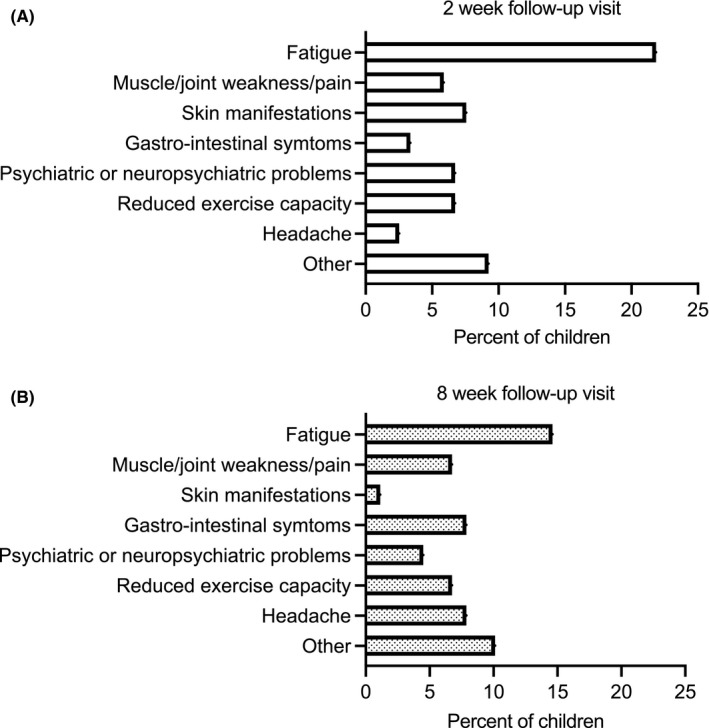

Figure 1 shows the distribution of self‐reported symptoms 2 and 8 weeks after the MIS‐C diagnosis. At 2 weeks, 51 of the 119 children reported persistent symptoms. The most common complaint was fatigue (22%), followed by skin manifestations (8%), psychiatric or neuropsychiatric problems and reduced exercise capacity (both 7%). These were followed by muscle or joint weakness or pain (7%), gastrointestinal symptoms (3%) and headaches (3%). At 8 weeks, 32 children reported persistent symptoms. The most common complaint was fatigue (14%), followed by gastrointestinal symptoms and headache (8%), muscle or joint weakness or pain and reduced exercise capacity (both 7%), psychiatric and neuropsychiatric problems (5%) and skin manifestations (1%).

FIGURE 1.

Complaints at the 2‐ and 8‐week follow‐up visits. (A) A total of 119 children had a registered 2‐week follow‐up visit and 51 reported any complaint. The most common were fatigue (n = 26), skin manifestations (n = 9), psychiatric or neuropsychiatric problems (n = 8), reduced exercise capacity (n = 8), muscle or joint weakness or pain (n = 7), gastrointestinal symptoms (n = 4), headaches (n = 3) and others (n = 11). (B) A total of 89 children had a registered 8‐week follow‐up visit and 32 reported any complaint. The most common were fatigue (n = 13), muscle or joint weakness or pain (n = 6), headaches (n = 7), gastrointestinal symptoms (n = 7), reduced exercise capacity (n = 6), psychiatric or neuropsychiatric problems (n = 4), skin manifestations (n = 1) and others (n = 9)

3.4. Follow‐up results by level of care

Table 4 shows the selected follow‐up outcome variables stratified by the level of care the patient received during the acute phase of MIS‐C. At 2 weeks, skin pathology, elevated d‐dimers and abnormal cardiac examinations were more common among children treated in an ICU or ECMO unit than among children treated on a general ward. At 8 weeks, self‐reported symptoms were more common among children treated in an ICU or ECMO unit. Abnormal complete blood counts, low albumin, high ferritin and abnormal cardiac examinations were more common among children treated in an ICU or ECMO unit than a general ward (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Abnormal findings in Swedish children with MIS‐C at the 2‐week and 8‐week follow‐up visits by highest level of care

| Highest level of initial care | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General ward or outpatient clinic | ICU or ECMO care | |||

| 2‐week follow‐up | 8‐week follow‐up | 2‐week follow‐up | 8‐week follow‐up | |

| n (% of total examined) | n (% of total examined) | n (% of total examined) | n (% of total examined) | |

| Total cases | 105 (88) | 74 (83) | 14 (12) | 15 (17) |

| Abnormal findings | ||||

| Clinical findings | ||||

| Patient history | 45 (43) | 24 (27) | 6 (43) | 8 (53) |

| Skin | 12 (12) | 3 (4) | 5 (36) | 1 (7) |

| Blood pressure | 6 (7) | 4 (6) | 1 (8) | 0 |

| Laboratory findings | ||||

| Complete blood cell count | 44 (43) | 7 (13) | 7 (59) | 3 (21) |

| Platelet count | 45 (45) | 14 (20) | 8 (62) | 1 (7) |

| Albumin | 28 (28) | 3 (5) | 5 (45) | 2 (15) |

| Ferritin | 20 (22) | 7 (13) | 6 (46) | 3 (21) |

| D‐dimer | 10 (11) | 4 (8) | 4 (36) | 1 (8) |

| Cardiology | ||||

| Electrocardiogram | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | 2 (15) | 1 (8) |

| Echocardiography | 9 (12) | 1 (2) | 5 (36) | 2 (15) |

4. DISCUSSION

The severity of inflammation and multiorgan involvement seen in many children during the acute phase of MIS‐C has raised concerns about persistent organ damage and long‐term health effects. In this Swedish prospective nationwide population‐based study, 133 children and teenagers with MIS‐C were identified and described. Physicians followed up 119 patients approximately 2 weeks after their diagnosis and 89 were followed up at approximately 8 weeks, according to pre‐defined clinical standards. Due to practical and administrative reasons, 14 children had follow‐up data at 8 weeks but not at 2 weeks. We had to focus purely on the numbers and percentages, as it was not possible to perform any statistical tests due to the small size of the sub‐samples. However, the clinical outcomes did seem to differ according to the age groups and the level of initial care that the patients received. At 2 weeks, 43% of the patients reported symptoms, but nearly all of them had a normal physical examination. The majority of the cohort had recovered, with no remaining symptoms or signs, 8 weeks after diagnosis. The most common complaint at that point was self‐reported fatigue.

To our knowledge, only three previous reports have focused on the medium‐ to long‐term outcomes of MIS‐C. 10 , 11 , 12 All these studies concluded that their patients recovered well after MIS‐C, despite being critically ill at the time of their initial admission. Due to the relatively small sample sizes and clear findings at follow‐up, questions about possible adverse outcomes have been raised. One study of 45 MIS‐C patients from the USA followed up 31 of them at 1–4 months and 24 at 4–9 months after initial hospitalisation. 11 The authors reported that persistent immunological features were detected several months after diagnosis. However, the only clinical data presented in that study were cardiological results and laboratory values. The most comprehensive multidisciplinary follow‐up programme to be reported to date was from the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in the UK, 10 which followed up 46 patients with MIS‐C 6 weeks and 6 months after diagnosis. The distribution of age and gender was similar to our study, but the disease severity was probably higher in the UK study, as 34.8% of the children were ventilated and only 15% of our cohort needed to be admitted to an ICU. This was the most important difference between the UK study and ours. Our aim was to focus on a population‐based study that included a range of very mild to severe cases and to develop a simple programme that colleagues across Sweden could use when they entered data on their MIS‐C patients into the Registry. In contrast, the UK study focused on severe, but well‐defined, cases that were followed, examined and assessed by a single multi‐professional team.

There were some similarities in the results of our study and the UK study. The UK authors also concluded that most children recovered after MIS‐C. A discouraging proportion (45%) of the UK patients performed less well than expected for the third percentile for age and sex in a 6‐min walk test at 6 months after MIS‐C. This finding corresponded well to the self‐reported fatigue (14%) and reduced exercise capacity (7%) in our study 8 weeks after diagnosis. The UK study found high numbers of emotional difficulties and anxiety at 6 months, both among the children affected by MIS‐C and their parents. In our study, 5% of the children spontaneously reported psychiatric or neuropsychiatric symptoms at the 8‐week follow‐up visit. It is reasonable to believe that a more severe acute disease, and the occurrence of multiorgan failure, may be associated with a worse long‐term outcome. Previous studies have not reported outcomes in relation to any measurements of disease severity. As an approximation of disease severity, we found that high levels of care seemed to be associated with a less favourable outcome 8 weeks after diagnosis.

It has been reported that cardiac symptoms and abnormal findings are common during the acute phase of MIS‐C. 17 , 18 In our cohort, 19% of the patients who underwent cardiac tests had reduced ejection fraction and 16% had abnormal coronary arteries during their hospital admission. The long‐term effects on the heart are unknown, but have been discussed by other studies. 6 , 19 Only three (5%) of the patients in our study who underwent cardiac tests had any echocardiography abnormalities at the 8‐week follow‐up. It is important to note that these three patients had abnormal echocardiograms during previous examinations. These results were consistent with previous studies, 10 , 11 , 12 suggesting that long‐term cardiac sequelae are uncommon after MIS‐C.

The Swedish recommendations have now been updated, based on this study and other studies, and they state that all patients with MIS‐C should be followed up with clinical visits at 2 and 8 weeks after their MIS‐C diagnosis and then again at 6 months. A 12‐month telephone check‐up is now recommended if patients had no complaints at 6 months. A cardiological examination should be performed at 2 and 8 weeks and a neuropsychiatric evaluation at 6 and 12 months. The follow‐up can end if everything is well at 12 months.

This follow‐up study has several strengths. It was the first prospective population‐based report of the disease course of MIS‐C. Specific modules in the Swedish Paediatric Rheumatology Registry were tailor‐made to facilitate the prospective reporting of consecutive patients with MIS‐C during the acute phase and during follow‐up visits. We included enough cases to stratify the results for age and level of care. The biweekly online meetings for physicians all over the country ensured that information on the study was shared and we believe that the mandatory requirement to report cases to the Registry meant that it covered almost 100% of Swedish MIS‐C cases during the study period. Not all Swedish paediatric centres asked their patients for consent to be included in this study, and therefore, our sample comprised 75% of the national Swedish cases during the study period. Swedish health care is Government funded and based on geographical regions and all MIS‐C patients in the participating regions would have been included in the study. In addition, missing data were minimal. These factors mean that our results are highly generalisable to similar populations.

Our study did have some limitations. First, we were not able to include all Swedish MIS‐C cases. Second, the data provided by the Registry were not entirely complete, as there were data missing on the follow‐up visits of 19 (13%) of the 152 MIS‐C patients. This could have been for several reasons. The treating physician may not have filled in the Registry form at the time of the follow‐up visits or the patients may have been admitted to hospital so recently that the first follow‐up visit had not yet been scheduled. In addition, 14 patients had follow‐up data registered at 8 weeks, but not 2 weeks. This may have been because some patients were still hospitalised 2 weeks after their MIS‐C diagnosis. These missing data are unlikely to have systematically skewed the study results. Third, some of the variables may have been misclassified. For example, we are aware that all cases should have reported fever at admission and that more than 80% of patients probably had positive SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody tests at some time after admission. Although these were limitations, these misclassifications should be viewed as non‐dependent, as they were not likely to have been associated with the outcomes or stratifications. Fourth, there were not enough patients to enable us to carry out statistical tests of group differences or analyse risk factors for adverse outcome. Fifth, indications for ICU care may have differed between regions and may not truly reflect the severity of disease. Sixth, we lacked data on treatment regimens and specific cardiology results in this dataset, which would have been interesting to correlate with long‐term symptoms.

Future research should focus on larger follow‐up studies with enough power to determine risk factors for adverse outcomes and persistent symptoms after MIS‐C. There is also a need for longer follow‐up studies and more detailed analyses of fatigue, reduced exercise capacity, parent and child psychiatric symptoms and treatment for long‐term symptoms. Ideally, there should be a randomised controlled trial of treatment options in the acute phase and effects on health parameters in the long run.

5. CONCLUSION

This population‐based study adds to our understanding of the full disease spectra of MIS‐C. We show that long‐term symptoms 8 weeks after diagnosis were few and mild and that organic sequelae, including cardiac consequences, appeared to be rare. However, more than a third of the children reported symptoms at the 8‐week follow‐up and these need to be detected and addressed in all cases. Age and the initial level of care may have influenced their long‐term recovery. Regular follow‐up visits after MIS‐C are important, and we suggest that after 8 weeks, the focus should be on the patient history, including exercise and mental capacity and psychological well‐being. Repeated assessments of cardiac function after normalisation at 8 weeks may not be required, but the long‐term effects of MIS‐C on cardiovascular health need to be more carefully evaluated.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Figure S1

Figure S2

Kahn R, Berg S, Berntson L, et al. Population‐based study of multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID‐19 found that 36% of children had persistent symptoms. Acta Paediatr.2022;111:354–362. doi: 10.1111/apa.16191

REFERENCES

- 1. Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez‐Martinez C, Wilkinson N, Theocharis P. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607‐1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki‐like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS‐CoV‐2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1771‐1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO . Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents temporally related to COVID‐19. 2020. Available at: https://www.WHO.int/news‐room/commentaries/detail/multisystem‐inflammatory‐syndrome‐in‐children‐and‐adolescents‐with‐covid‐19 Accessed 29 July, 2021.

- 4. Ouldali N, Toubiana J, Antona D, et al. Association of intravenous immunoglobulins plus methylprednisolone vs immunoglobulins alone with course of fever in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. JAMA. 2021;325:855‐864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McArdle AJ, Vito O, Patel H, et al. Treatment of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:11‐22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harwood R, Allin B, Jones CE, et al. A national consensus management pathway for paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with COVID‐19 (PIMS‐TS): results of a national Delphi process. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:133‐141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feldstein LR, Tenforde MW, Friedman KG, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of US children and adolescents with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS‐C) compared with severe acute COVID‐19. JAMA. 2021;325:1074‐1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahmed M, Advani S, Moreira A, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evans C, Davies P. SARS‐CoV‐2 paediatric inflammatory syndrome. Paediatr Child Health (Oxford). 2021;31:110‐115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Penner J, Abdel‐Mannan O, Grant K, et al. 6‐month multidisciplinary follow‐up and outcomes of patients with paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome (PIMS‐TS) at a UK tertiary paediatric hospital: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:473‐482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Farooqi KM, Chan A, Weller RJ, et al. longitudinal outcomes for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Pediatrics. 2021;148(2):e2021051155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patnaik S, Jain MK, Ahmed S, et al. Short‐term outcomes in children recovered from multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:1957‐1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Society TSP . Covid‐associated Hyperinflammation ALB. 2020. Available at: https://reuma.barnlakarforeningen.se/vardprogram/ Accessed 29 July, 2021.

- 14. Society TSP . Nationella Riktlinjer För Uppföljning Av Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome In Children (Mis‐C) 2020. Available at: https://reuma.barnlakarforeningen.se/vardprogram/ Accessed 29 July, 2021.

- 15. Registry TSPR . Available at: http://barnreumaregistret.se Accessed 29 July, 2021.

- 16. Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad‐Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659‐667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Valverde I, Singh Y, Sanchez‐de‐Toledo J, et al. acute cardiovascular manifestations in 286 children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID‐19 infection in Europe. Circulation. 2021;143:21‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alsaied T, Tremoulet AH, Burns JC, et al. Review of cardiac involvement in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. Circulation. 2021;143:78‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, et al. American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance for Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children Associated With SARS‐CoV‐2 and Hyperinflammation in Pediatric COVID‐19: version 2. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73:e13‐e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1

Figure S2