Abstract

Although the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has amplified risk factors known to increase children’s vulnerability to abuse and neglect, emerging evidence suggests declines in maltreatment reporting and responding following COVID-19 social distancing protocols in the United States. Using statewide administrative data, this study builds on the current state of knowledge to better understand the volume of child protection system (CPS) referrals and responses in Colorado, USA before and during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and to determine whether there were differences in referral and response rates by case characteristics. Results indicated an overall decline in referrals and responses during COVID-19 when compared to the previous year. Declines were specific to case characteristics, such as reporter and maltreatment type. Implications regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child maltreatment reporting and CPS response are discussed.

Keywords: abuse, child maltreatment, child protection, COVID-19, neglect

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has led to extensive hardship for children and families worldwide, including heightened economic instability (Nicola et al., 2020; U.S. Department of Labor, 2020), disconnection from schools and support systems (Fishbane & Tomer, 2020), and increased emotional and behavioral reactions such as fear and anxiety (Brown et al., 2020; Rajkumar, 2020). Evidence from past public health threats and economic recessions demonstrates that school closures, increased social isolation, and unemployment/financial loss contribute to widening health, economic, and educational disparities and serve as known risk factors for child maltreatment (Rashid et al., 2015; Schneider et al., 2016; Sell et al., 2010). Studies of self-reported stressors from families in the United States demonstrate that pandemic-related factors, including changes in parental mood or physical health, financial well-being, employment status, children’s education, or parent-child relationships may increase parental perceptions of stress as well as psychological and physical maltreatment of children (Brown et al., 2020; Lawson et al., 2020). More-over, spaciotemporal incident data reveal that in areas with housing instability, poverty, or school absenteeism, incidence of child abuse and neglect have increased from the same time period preceding the COVID-19 pandemic social distancing protocols (Barboza et al., 2020).

Despite such documented increases in risk factors for child maltreatment, national reports of child abuse and neglect have decreased since the pandemic’s inception (Rapoport et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2020). Many of the prevention measures to reduce disease transmission have resulted in changes to the child protection system (CPS) by altering the way services are delivered to children and families (Petrowski et al., 2020). As a result, several states have seen an 18%–50% decrease in referrals to the CPS for alleged abuse and neglect (Amaro, 2020; Prabhu, 2020; Streicher, 2020). Such declines mirror drops in referral rates generally seen during holidays and summer, when mandatory reporters (e.g., teachers, health and behavioral health professionals, daycare and after-school providers) have less regular contact with children (Jonson-Reid et al., 2020; Weiner et al., 2020). Declines in reporting during COVID-19 are also consistent with data from past economic downturns that reveal certain regions of the United States experienced significant variation in referrals to the CPS (Bitler & Zavodny, 2004), especially for specific types of maltreatment such as physical abuse (Schenck-Fontaine & Gassman-Pines, 2020).

Discrepancies in trends regarding maltreatment risk between national and self-report data thus warrant further attention. That is, the pandemic is a time when parents/care-givers are reporting greater distress and risk factors that may be implicated in maltreatment, but preliminary CPS data indicate that children are less likely to be reported and investigated. Therefore, the current study used state administrative data to understand the scope of child protection referrals and responses in Colorado for select periods before and during the global COVID-19 pandemic and associated shutdowns. Specifically, we compared referrals and responses in Colorado prior to the pandemic and during early closure periods, as well as examined the extent to which the pandemic may have changed mean weekly referral and response counts overall. We hypothesized that significant drops in mean weekly CPS referral and response counts occurred in early- to mid-2020 and that the timing of these drops aligned with Colorado’s initial school-closure and stay-at-home orders, effective March 2020. We also descriptively examined changes by specific referral and response characteristics. Findings can inform the CPS on adaptations and actions needed to respond to unparalleled, evolving conditions that disrupt the lives of children and families.

Method

Data and Population

Administrative data from Colorado’s Comprehensive Child Welfare Information System (CCWIS) were used. The CCWIS includes a range of information on all children who come to the attention of Colorado’s CPS. To understand possible changes in CPS referrals and responses before and during COVID-19, referral and response data were examined for children and youth involved with Colorado’s CPS as a result of reports of abuse and/or neglect or “youth-in-conflict” between January and July of 2019 or 2020, respectively. Data were grouped into the 11 full weeks of 2020 prior to the arrival of COVID-19 in Colorado and statewide stay-at-home orders (January 5th to March 21st 2020; “pre-COVID-19 weeks”) and 17 weeks during the early onset of COVID-19 and resultant stay-at-home to safer-at-home orders (March 22nd to July 17th 2020; “COVID-19 weeks”). Comparable 11-week and 17-week groupings were defined for the year 2019 to create a baseline comparison (see Table 1). The 11- and 17-week groupings thus mirror how the pandemic unfolded in the study setting (Colorado) and are used to maintain our focus on COVID-19-related trends in early 2020 and a comparison with the prior year.

Table 1.

Volume of Colorado CPS Referrals and Responses Before and During COVID-19.

| “Pre-COVID-19 Weeks” | “COVID-19 Weeks” | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| January 06–March 23, 2019 (11 Weeks) Weekly Mean (N) | January 05–March 21, 2020 (11 Weeks) Weekly Mean (N) | March 24–July 20, 2019 (17 Weeks) Weekly Mean (N) | March 22–July 17, 2020 (17 Weeks) Weekly Mean (N) | |

| Total Referrals (Counts) | 2,394 (26,331) | 2,521 (27,729) | 2,094 (35,598) | 1,510 (25,678) |

| Referral Case Characteristic Referrals by Reporter Type | n | n | n | n |

|

| ||||

| County | 817 | 636 | 1,157 | 947 |

| Court-Order | 358 | 381 | 546 | 300 |

| Daycare Provider | 181 | 195 | 331 | 201 |

| Family/Relative | 1,519 | 1,494 | 2,559 | 2,303 |

| Law Enforcement | 3,276 | 3,120 | 5,476 | 4,457 |

| Medical Professional | 2,305 | 2,474 | 3,759 | 2,997 |

| Mental Health Professional | 4,348 | 4,438 | 5,404 | 3,639 |

| Neighbor/Friend | 670 | 644 | 1,247 | 1,482 |

| Others | 3,297 | 3,816 | 5,765 | 4,580 |

| Parent | 1,322 | 1,422 | 2,103 | 2,099 |

| School | 7,583 | 8,595 | 6,358 | 1,988 |

| Social Worker | 655 | 514 | 893 | 685 |

|

| ||||

| Weekly mean (N) | Weekly mean (N) | Weekly Mean (N) | Weekly Mean (N) | |

|

| ||||

| Total Responses (Counts) | 803 (8,838) | 806 (8,868) | 725 (12,329) | 552 (9,386) |

| Response Case Characteristic Responses by Reporter Type | n | n | n | n |

|

| ||||

| County | 268 | 242 | 417 | 318 |

| Court-Order | 291 | 285 | 439 | 238 |

| Day Care Provider | 47 | 44 | 91 | 59 |

| Family/Relative | 453 | 438 | 795 | 805 |

| Law Enforcement | 1,663 | 1,464 | 2,743 | 2,402 |

| Medical Professional | 1,006 | 1,021 | 1,664 | 1,397 |

| Mental Health Professional | 1,178 | 1,080 | 1,409 | 996 |

| Neighbor/Friend | 199 | 203 | 385 | 482 |

| Others | 989 | 1,070 | 1,617 | 1,401 |

| Parent | 329 | 350 | 524 | 603 |

| School | 2,195 | 2,478 | 1,910 | 422 |

| Social Worker | 220 | 193 | 335 | 263 |

| Responses by Maltreatment Type | n | n | n | n |

|

| ||||

| Domestic Violence in the Home | 1,394 | 1,481 | 2,156 | 2,009 |

| Sexual Abuse | 939 | 952 | 1,346 | 1,114 |

| Physical Abuse | 2,132 | 2,323 | 2,721 | 1,887 |

| Neglect | 4,345 | 4,730 | 6,099 | 5,104 |

Note. Reporter types for referrals and responses are mutually exclusive. There may be multiple types of maltreatment identified for a single response. Administrative procedures also permit caseworkers up to 60 days to complete records and data entry delays due to the burden of COVID-19 are expected; as such, data herein may be incomplete.

Variables

CPS referrals.

The population of referrals for the two groupings for years 2019 and 2020 were included. Referrals to the CPS encompassed all calls made to the Colorado Child Abuse and Neglect Hotline System as well as other methods of referral (e.g., letter, walk-in to a County Human Services Department). Case characteristics about the referrals, specifically the source of the referral (reporter type), were also included. Given the breadth of calls made to the CPS, several types of reporters are possible; therefore, we recoded them into distinct categories as follows: county, court-order, daycare provider, family/relative, law enforcement, medical professional, mental health professional, neighbor/friend, parent, school, social worker, and “other” (e.g., other community agency, victim’s advocate, first responder, unknown/anonymous, etc.).

CPS response.

CPS responses were defined by whether a referral was screened-in, which includes a referral that was accepted for follow-up through either a traditional investigation or an alternative response.1 For each CPS response, case characteristics about the source of the initial referral (reporter type) and type of maltreatment allegation (sexual abuse, domestic violence, physical abuse, and neglect) were included in order to examine the potential impact of COVID-19 on CPS response patterns.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe changes in CPS referrals and responses by reporter and maltreatment type based on the above-mentioned 11- and 17-week timeframes. Then, changepoint analyses were conducted to examine significant differences in mean counts of overall referrals and responses between selected weeks in early 2019 and 2020. As outlined by Killick and Eckley (2014), changepoint detection refers to the problem of estimating the point at which statistical properties of a sequence of observations change. Although methods for multiple changepoint detection are available, the current study seeks to confirm the presence of one major changepoint for child welfare referrals and responses related to COVID-19. The detection of a single changepoint is posed as a hypothesis test. The null hypothesis corresponds to no changepoint and the alternative hypothesis corresponds to a single changepoint. A parametric, general likelihood ratio test statistic for detecting mean differences is calculated, based on methods originally proposed by Hinkley (1970).

We used the “changepoint” package as implemented in the R statistical computing environment (Killick et al., 2014) to test for a hypothesized difference in means before and after the beginning of the pandemic. We used the methodology of “at most one change” in each time series (CPS referrals and responses) because we hypothesized that there is likely one significant change in mean weekly referral counts due to COVID-19. For the changepoint analyses, we only included data from weeks 2 through 20 (i.e., mid-January through mid-May) during both 2019 and 2020 because this is a period of time unaffected by typical fluctuations in referrals and responses due to normal school break closures and associated seasonal change (Jonson-Reid et al., 2020; Weiner et al., 2020). We expected that the null hypothesis of no changepoint during the specified time period would be rejected. Rather, we expected to find a statistically significant drop in mean weekly child welfare referral counts and response counts at either week 11 or 12 of year 2020, corresponding to Colorado’s mandatory stay-at-home orders, as indicated by a changepoint. If a changepoint is identified, we compared the pre-changepoint and post-changepoint means.

Results

Overall volume of Colorado CPS referrals and responses prior to and during COVID-19 and according to case characteristics are described in Table 1.

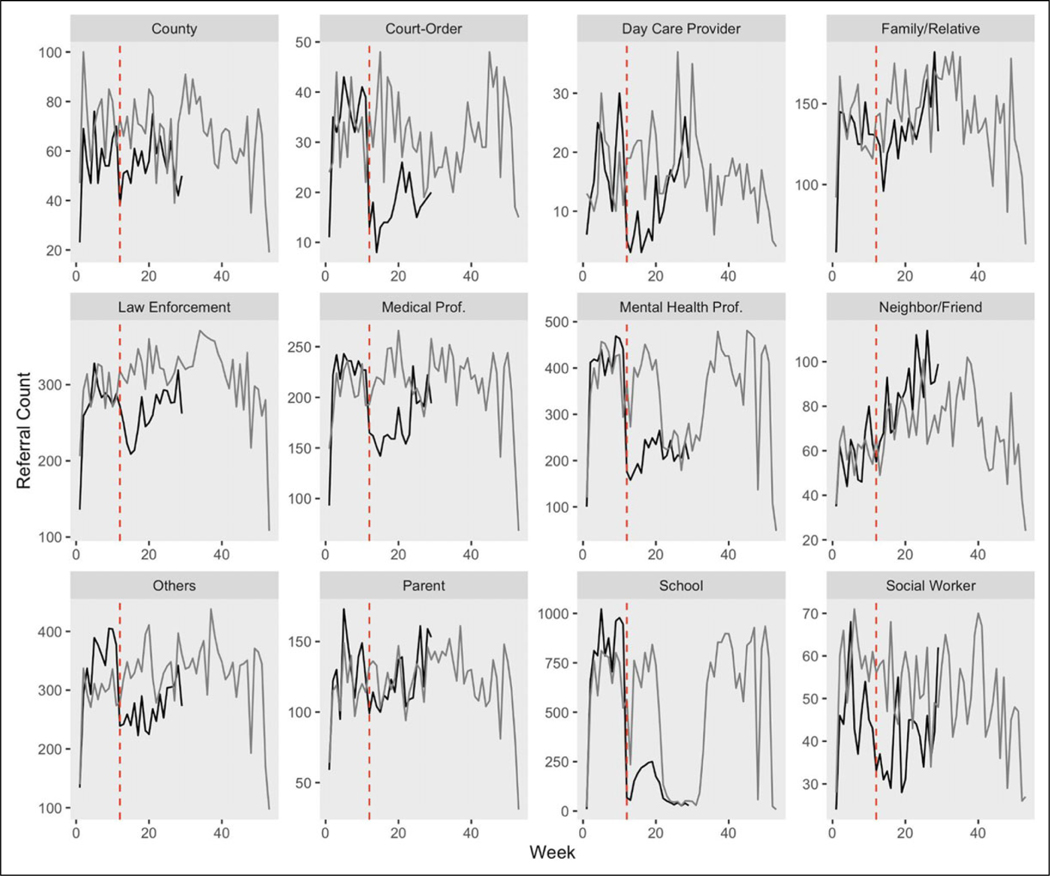

CPS Referrals

Total CPS referrals were up from 26,331 during the first 11 weeks of 2019 to 27,729 in the first 11 weeks of 2020, an increase of 5.3% and one consistent with rises in referrals to the CPS across the nation in recent years (U.S. DHHS, 2020). In the period following the COVID-19 restrictions, referrals decreased from 35,598 to 25,678 in a 17-week period from late March to late July. This change is a substantial 27.9% drop over 2019. Drops in referrals were related to reporter type, with court-orders, day care providers, and mental health and school professionals showing the most notable decreases. Specifically, there were considerable decreases in referrals by court-orders of 45.1% (546 to 300), daycare providers of 39.3% (331 to 201), mental health professionals of 32.7% (5,404 to 3,639), and school professionals of 68.7% (6,358 to 1,988) between comparable periods in 2019 and 2020. Furthermore, referrals by several other types of reporters including family/relatives, county, law enforcement, medical professionals, and social workers showed slight decreases, ranging from 10% to 23.3%. In contrast, there was an increase in referrals by neighbors/friends of 18.8% (1,247 to 1,482) between comparable periods in 2019 and 2020. These changes are graphically illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Colorado referral volume by reporter type: 2019 versus 2020. Note. Dashed vertical line represents start of COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions. Light line represents 2019; dark line represents 2020.

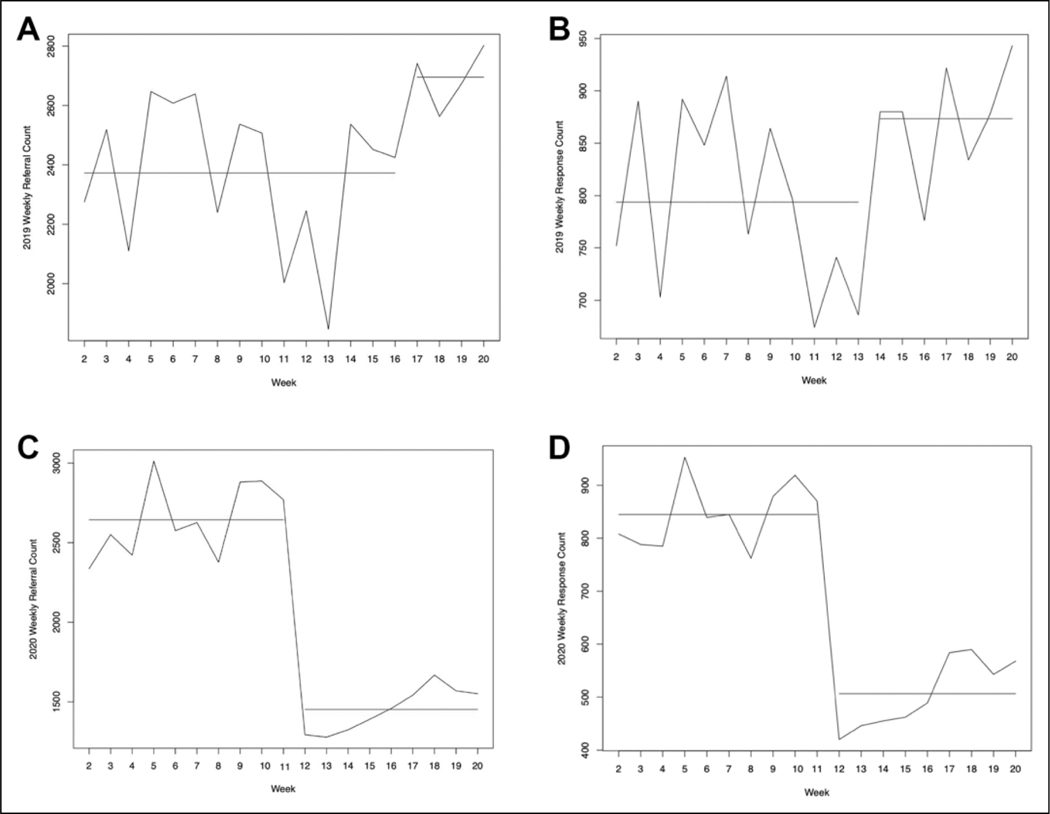

The changepoint analysis causes us to reject the null hypothesis that no changepoint exists in the mean weekly referral count between weeks 2 and 20. Instead, the analysis identified a statistically significant changepoint, and the changepoint occurs at 11 weeks, as hypothesized. The pre-changepoint mean weekly referral count is estimated to be 2,643.6 (mean referrals per week up to week 11) and the post-changepoint mean weekly referral count drops to 1,452.6 mean weekly referrals after week 11. The change in mean for 2020 is illustrated on the graph in Figure 2C by the horizontal line segments. For comparison, the changepoint graph for the same time period in 2019 (weeks 2 through 20) is shown in Figure 2A. No changepoint was detected at week 11 using the 2019 data; the figure is provided as a comparison confirming that the 2020 week 11 changepoint was due to COVID-19 stayat-home restrictions.

Figure 2.

Identified changepoints in weekly referrals and responses for 2019 versus 2020. (A) 2019 Weekly Referral Volume. (B) 2019 Weekly Response Volume. (C) 2020 Weekly Referral Volume. (D) 2020 Weekly Response Volume.

CPS Responses

Total CPS responses were flat between the first 11 weeks of 2019 (8,838 responses) to the first 11 weeks of 2020 (8,868 responses). In the period following the COVID-19 restrictions, responses dropped from 12,329 to 9,386, a 23.9% decrease over 2019, as shown in Table 1. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 17-week period, drops in responses were related to reporter type similar to the trends seen in referrals. Specifically, there were considerable decreases in responses by court-orders of 45.8% (439 to 238), daycare providers of 35.2% (91 to 59), mental health professionals of 29.3% (1,409 to 996), and school professionals of 77.9% (1,910 to 422) as well as an increase in responses by neighbors/friends of 25.2% (385 to 482) between comparable periods in 2019 and 2020. Moreover, responses by several other types of reporters including county, law enforcement, medical professionals, and social workers showed slight decreases, ranging from 12.4% to 23.7%, whereas responses according to family/relative reporters remained relatively stable. Furthermore, there were drops in percentage of responses involving physical abuse (30.7%), sexual abuse (17.2%), neglect (16.3%), and/or domestic violence (6.8%).

The changepoint analysis also identified a statistically significant drop in the mean weekly response counts at week 11 of year 2020; as with referrals, the drop aligns with Colorado’s COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions. Graphical representations of time series changepoints are included in Figure 2, with horizontal lines in Figure 2D indicating mean weekly counts before and after the identified changepoint in 2020. The pre-changepoint mean weekly response count is estimated to be 844.8 and the post-changepoint mean weekly response count is 506.3. Thus, the hypotheses of no change in mean weekly counts for both referrals and responses are rejected, with the identified changepoint as expected at week 11 for both. Note that, based on the mean weekly counts, 32% of referrals were screened in for a response prior to the COVID-19 shutdowns (weeks 2 through 11)and34.9% of referrals were screened in for a response afterward (weeks 12–20). Thus, the overall proportion of mean weekly referrals which were screened in increased slightly.

Discussion

We used administrative data to examine the volume of Colorado CPS referrals and responses for select periods before and during COVID-19. Findings show an overall decline in the volume of referrals and responses during COVID-19 compared to the previous year. As such, there are declines in responses for all types of maltreatment allegations, ranging from 6.8% for domestic violence in the home to 30.7% for child physical abuse. Specific declines in the volume of referrals and responses are also evident according to certain types of reporters.

Findings underscore the impact that COVID-19 is having on referrals to the CPS. Indeed, we found that after COVID-19 stay-at-home restrictions were enforced, there were notable decreases in court mandated, daycare providers’, and mental health and school professionals’ reporting, as well as increases in neighbors’ and friends’ reporting of potential maltreatment. That more families were at home and thus more likely to interact with their surrounding community may support the increasing trends in referrals by neighbors and friends and subsequent CPS responses. Moreover, our conclusions are consistent with other early data regarding the impact of COVID-19 on child maltreatment reporting (e.g., Baron et al., 2020; Rapoport et al., 2020). For instance, school closings occurred across the United States; Florida data from March and April 2020 show decreases of 27% in levels of reporting, with the decline driven by daycare and school closures (Baron et al., 2020). Similarly, New Hampshire data suggest a 50% reduction in calls to the state’s Children, Youth, and Families hotline (ISPCAN, in press), also corresponding to school closures. Declines in referrals by school professionals, as associated with school closures, reflects the fact that under usual circumstances, educational personnel are responsible for the highest percentage of reports of suspected cases of child maltreatment nationally (U.S. DHHS, 2020). Additionally, declines observed in reporting by mental health professionals may be due in part to increased telehealth services, necessitated by physical distancing requirements and mandatory closures of facilities. Racine and colleagues (2020) have identified several barriers to detecting and addressing child maltreatment in the context of telehealth services, including: not all families have reliable access to telehealth technology, which reduces interaction with providers and thus their ability to detect (and report) suspected cases of child maltreatment, particularly for the most economically and socially marginalized children; physical limitations related to lack of private spaces in the home that can ensure client confidentiality and safety of the child to disclose maltreatment; and providers not being readily equipped with strategies to handle disclosures in trauma-informed ways in the context of telehealth.

Typically, educational personnel make the most referrals to the CPS, followed by law enforcement, medical providers, and mental health professionals. However, nationally, referrals from school and mental health professionals translate to the lowest percentage of CPS victims, while referrals from medical providers and law enforcement translate to the highest percentage (Weiner et al., 2020). Our finding of a slight increase in the overall proportion of mean weekly referrals screened-in for response may reflect the higher proportion of total referrals during the COVID-19 weeks of 2020 (as compared to the equivalent 2019 period) being made by law enforcement and medical personnel, whose reports more likely identify victims. Additionally, because under usual circumstances reports by school and mental health professionals result in lower percentages of CPS responses, sharp declines in referrals by these reporter types may not necessarily indicate a staggering number of “missed cases” of maltreatment.

However, given preliminary evidence that the circumstances of the pandemic suggest that risk of maltreatment is rising rather than falling, and the majority of perpetrators of child abuse and neglect are parents (U.S. DHHS, 2020), efforts to support and stabilize families to prevent child maltreatment are warranted (Weiner et al., 2020). Indeed, public health challenges are generally associated with increases in a variety of mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, and substance use (Galea et al., 2020). Risk for parental burnout and diminished family and community level protective factors for child maltreatment are also likely to increase (Griffith, 2020). This may be due in part to significant disruption in caregivers’ daily schedules, decreased social systems, and reduced concrete supports, including loss of employment or income (Lawson et al., 2020); difficulties with childcare and managing homeschooling or distance learning while also working from home or required employment outside the home (e.g., essential workers) (Brown et al., 2020; Cabarkapa et al., 2020); decreased interaction with friends and family (Peterman et al., 2020); and uncertainty regarding health status (Griffith, 2020).

In light of the possibility that some educational and mental health settings may continue in virtual formats beyond COVID-19, enhanced training and approaches for mandatory reporters to recognize maltreatment-based concerns before they escalate during virtual visits is needed (Racine et al., 2020; Weiner et al., 2020). Advanced training for professionals to be alert to the signs and symptoms of child maltreatment within virtual contexts may help reduce the risk of false positives and negatives. Such efforts may prevent children from entering the CPS for reasons that do not warrant an investigation, such as food insecurity or housing issues, but instead call attention to the necessity of meeting families’ basic needs (Maguire-Jack et al., 2018). The circumstances surrounding COVID-19 may thus invite the CPS and the broader community to reconsider surveillance strategies that are more sensitive to social inequities and avoid misidentifying and labeling families as “high-risk” (Pollack, 2010).

As such, the CPS should also pivot responses from a focus on promoting conventional surveillance by mandatory reporters to utilizing alternative methods of identifying child maltreatment. CPS agencies can support other maltreatment prevention and identification strategies by advancing community-based approaches to leverage family and community strengths. For example, research denotes that enhancing contexts surrounding families, including neighborhoods and schools, can strengthen communities to prevent child maltreatment (van Dijken et al., 2016). CPS agencies can provide public education in neighborhoods on child maltreatment and positive parenting, partner with stakeholders to implement prosocial family activities, and bolster assets that already exist within the community (Roygardner et al., 2021). Furthermore, the growing provision of mutual aid, or informal social support, in communities may be another promising strategy to encourage neighbors and friends both to pay attention to signs of child abuse and neglect (Budde & Schene, 2004) and to contribute to community-based prevention efforts. Equipping communities with resources to not only detect signs of maltreatment but also to attend to the needs of vulnerable families may help to mitigate maltreatment risk and its consequences.

Although beyond the scope of what the current CPS system is designed and funded to effectuate, prevention services and supports that work to reduce the heightened maltreatment risk that COVID-19 has created are certainly warranted. This will require child welfare leaders, practitioners, and decision-makers to strategically partner with community-based agencies, other health and human service systems, and families themselves to ensure families have what they need to care for their children, address challenges that arise, and stabilize the family unit. Our recommendation for the CPS to adapt their response by putting collective resources and collaborative efforts behind a prevention approach is in line with increasing calls nationally to move from a child welfare system to a child and family well-being system, including the Family First Prevention Services Act (P.L. 115–123) and the Thriving Families, Safer Children initiative spearheaded by the Children’s Bureau, Casey Family Programs, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, and Prevent Child Abuse America (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2020; Children’s Bureau, 2020). This recommendation aims to increase capacity of the CPS to respond to the ongoing concerns that are anticipated to persist even when the virus itself is under control. Child welfare caseworkers are already facing peritraumatic distress from the impacts of COVID-19 (Miller, Niu, & Moody, 2020), and the likelihood of caseworker burnout due to an overburdened child welfare system in the future is high (Wulczyn, 2020). By working to re-orient the CPS actions toward prevention and collective responsibility for child welfare now, infrastructure can be created that works to mitigate system overload while better serving families and communities long-term.

This study used administrative data to provide timely insight into the evolving nature of CPS referral and response trends before and during COVID-19; however, there are some limitations. Administrative data from local and state child protection agencies provide information about the specific entities which drive the reporting of child maltreatment under usual circumstances and can be useful in understanding the implications of global pandemics in changing referral and response patterns (Jud et al., 2016). However, relying on a single system-originated source to capture incidence of alleged child maltreatment does not estimate the true prevalence of child maltreatment during the pandemic and thus should be considered along with analyses from other state and national data. Moreover, given that our study reflects a focused analysis of CPS referrals and responses before and during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic and whether differences exist according to reporter and maltreatment type, future studies would benefit from a more nuanced understanding of factors that may be implicated in CPS involvement in addition to long-term follow-up. For example, examining family sociodemographic characteristics, maltreatment severity, placement decisions, or permanency outcomes as well as data regarding whether changes in CPS responses are conditional on referrals during a global pandemic could be informative.

Conclusion

In summary, our findings highlight Colorado CPS referrals and responses for select periods before and during COVID-19, corresponding to pandemic-related shutdowns. Results provide an emergent understanding of system-specific shifts during the global public health pandemic and give insight into adaptations the CPS may evoke in responding to increased stressors experienced by families and the associated, elevated risk for child maltreatment. Additional efforts are needed to more accurately assess the true influence of the COVID-19 pandemic in the context of maltreatment-related risk and protective factors through diverse methodologies and follow-up studies.

Acknowledgments

Access to the data was provided by the Colorado Department of Human Services (CDHS), Office of Children, Youth, and Families. The content of this manuscript is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of CDHS. This study was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health and Human Development (K01HD098331) awarded to S.M. Brown.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K01HD098331).

Footnotes

Alternative response in Colorado is called Differential Response, and referrals screened-out may receive service connections but no other further involvement with the CPS occurs; for more information, see the Colorado Department of Human Services Differential Response Program: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/cdhs/differential-response-program

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Amaro Y. (2020). Fresno-area officials fear child abuse going unreported amid coronavirus quarantine. https://www.fresnobee.com/news/local/article241754056.html [Google Scholar]

- Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2020). First-of-its-kind partnership aims to redesign child welfare into child and family well-being systems. https://www.aecf.org/blog/first-of-its-kind-partnership-aims-to-redesign-child-welfare-into-child-and/ [Google Scholar]

- Barboza GE, Schiamberg LB, & Pachl L. (2020). A spatiotemporal analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on child abuse and neglect in the city of Los Angeles, California. Child Abuse & Neglect. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron EJ, Goldstein EG, & Wallace C. (2020). Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. 10.2139/ssrn.3601399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitler MP, & Zavodny M. (2004). Child maltreatment, abortion availability, and economic conditions. Review of Economics of the Household, 2, 119–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Doom J, Watamura SE, Lechuga-Penã S, & Koppels T. (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Advance online publication. 10.31234/osf.io.ucezm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde S, & Schene P. (2004). Informal social support interventions and their role in violence prevention: An agenda for future evaluation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(3), 341–355. 10.1177/0886260503261157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabarkapa S, Nadjidai SE, Murgier J, & Ng CH (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: A rapid systematic review. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity Health. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Bureau, An Office of the Administration for Children & Families. (2020). Title IV-E Prevention Program. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/title-iv-e-prevention-program

- Fishbane L, & Tomer A. (2020). As classes move online during COVID-19, what are disconnected students to do? https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/03/20/as-classes-move-online-during-covid-19-what-are-disconnected-students-to-do/ [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Merchant RM, & Lurie N. (2020). The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(6), 817–818. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith AK (2020). Parental burnout and child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s10896-020-00172-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkley DV (1970). Inferences about the change-point in a sequence of random variables. Biometrika, 57(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- International Society for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. (in press). World Perspectives on Child Abuse 2020 (14th Ed.). ISPCAN. [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid M, Drake B, Cobetto C, & Gandarilla Ocampo M. (2020). Child abuse prevention month in the context of COVID-19. Center for Innovation in Child Maltreatment Policy, Research and Training. https://cicm.wustl.edu/child-abuse-prevention-month-inthe-context-of-covid-19/ [Google Scholar]

- Jud A, Fegert JM, & Finkelhor D. (2016). On the incidence and prevalence of child maltreatment: A research agenda. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 10, 17. 10.1186/s13034-016-0105-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killick R, & Eckley I. (2014). Changepoint: An R package for changepoint analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 58(3), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Killick R, Eckley I, & Haynes K. (2014). Changepoint: An R package for Changepoint Analysis (R package version 1.1.5). http://CRAN.R-project.org/package¼changepoint [Google Scholar]

- Lawson M, Piel MH, & Simon M. (2020). Child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consequences of parental job loss on psychological and physical abuse towards children. Child Abuse & Neglect. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Jack K, Negash T, & Steinman KJ (2018). Child maltreatment prevention strategies and needs. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 3572–3584. 10.1007/s10826-018-1179-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JJ, Niu C, & Moody S. (2020). Child welfare workers and peritraumatic distress: The impact of COVID-19. Children & Youth Services Review, 119, 105508. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, Agha M, & Agha R. (2020). The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. International Journal of Surgery, 78, 185–193. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterman A, Potts A, O’Donnell M, Thompson K, Shah N, Oertelt-Prigione S, & van Gelder N. (2020). Pandemics and violence against women and children (CGD Working Paper 528). Center for Global Development. [Google Scholar]

- Petrowski N, Cappa C, Pereira A, Mason H, & Daban RA (2020). Violence against children during COVID-19: Assessing and understanding change in use of helplines. Child Abuse & Neglect. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack S. (2010). Labelling clients ‘risky’: Social work and the neoliberal welfare state. British Journal of Social Work, 40, 1263–1278. 10.1093/bjsw/bcn079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu MT (2020). Child abuse reporting in Georgia down by half since schools closed amid virus. https://www.ajc.com/news/state-regional-govt-politics/child-abuse-reporting-georgia-down-halfsince-schools-closed-amid-virus/RKg3HzBy86Ai3QNq3jrZML/ [Google Scholar]

- Racine N, Hartwick C, Collin-Vénzina D, & Madigan S. (2020). Telemental health for child trauma treatment during and postCOVID-19: Limitations and considerations. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104698. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar RP (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 102066. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport E, Reisert H, Schoeman E, & Adesman A. (2020). Reporting of child maltreatment during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in New York City from March to May 2020. Child Abuse & Neglect. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid H, Ridda I, King C, Begun M, Tekin H, Wood JG, & Booy R. (2015). Evidence compendium and advice on social distancing and other related measures for response to an influenza pandemic. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 16, 119–126. 10.1016/j.prrv.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roygardner D, Hughes KN, & Palusci VJ (2021). Leveraging family and community strengths to reduce child maltreatment. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social science, 692 (1), 119–139. 10.1177/0002716220978402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schenck-Fontaine A, & Gassman-Pines A. (2020). Income inequality and child maltreatment risk during economic recession. Children and Youth Services Review, 112. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider D, Harknett K, & McLanahan S. (2016). Intimate partner violence in the great recession. Demography, 53, 471–505. 10.1007/s13524-016-0462-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell K, Zlotnik S, Noonan K, & Rubin D. (2010). The effect of recession on child well-being: A synthesis of the evidence by PolicyLab, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. https://policylab.chop.edu/sites/default/files/pdf/publications/PolicyLab_Recession_ChildWellBeing.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Streicher B. (2020). Texas child abuse reports are down amid stay-athome orders, but the threat is still there. https://www.kvue.com/article/news/investigations/defenders/texas-child-abuse-reportsdown-amid-stay-at-home-orders/269-fe078db6-7c98-499c-a95a-c3b694b6e5fe [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EY, Anurudran A, Robb K, & Burke TF (2020). Spotlight on child abuse and neglect response in the time of COVID-19. The Lancet, 5, e371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health & Human Services (U.S. DHHS), Admin-istration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2020). Child maltreatment 2018. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment

- U.S. Department of Labor. (2020). New release: Unemployment insurance weekly claims. https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf

- van Dijken MW, Stams GJJM, & de Winter M. (2016). Can community-based interventions prevent child maltreatment? Children and Youth Services Review, 61, 149–158. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner D, Heaton L, Stiehl M, Chor B, Kim K, Heisler K, Foltz R, & Farrell A. (2020). Chapin Hall issue brief: COVID-19 and child welfare: Using data to understand trends in maltreatment and response. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Wulczyn F. (2020). Looking ahead: The nation’s child welfare systems after Coronavirus. The Imprint. https://imprintnews.org/child-welfare-2/looking-ahead-the-nations-child-welfare-systems-after-coronavirus/41738 [Google Scholar]