Abstract

To develop an in vivo tool to probe brain genotoxic stress, we designed a viral proxy as a single-cell genetic sensor termed PRISM that harnesses the instability of recombinant adeno-associated virus genome processing and a hypermutable repeat sequence–dependent reporter. PRISM exploits the virus-host interaction to probe persistent neuronal DNA damage and overactive DNA damage response. A Parkinson’s disease (PD)–associated environmental toxicant, paraquat (PQ), inflicted neuronal genotoxic stress sensitively detected by PRISM. The most affected cell type in PD, dopaminergic (DA) neurons in substantia nigra, was distinguished by a high level of genotoxic stress following PQ exposure. Human alpha-synuclein proteotoxicity and propagation also triggered genotoxic stress in nigral DA neurons in a transgenic mouse model. Genotoxic stress is a prominent feature in PD patient brains. Our results reveal that PD-associated etiological factors precipitated brain genotoxic stress and detail a useful tool for probing the pathogenic significance in aging and neurodegenerative disorders.

A novel genetic sensor was developed to trace DNA damage response in the brain.

INTRODUCTION

Most cases of neurodegenerative disorders (NDDs), such as Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s diseases (PD), are idiopathic, with no identifiable inheritance, and occur in a sporadic form (1). Environmental risk factors have long been implicated in the etiology of sporadic NDDs (2). However, the causal evidence and mechanistic insights into the pathogenic role of environmental risk factors in NDDs are still mostly unknown.

The recent discovery of nongermline inherited, somatic mutations in human brains provides further evidence associating environmental risk with the etiology of sporadic NDDs (3). Age-dependent accumulation of somatic mutations has been associated with aging and neurodegenerative cases (4, 5). Multiple studies have identified a low allele frequency of mutations of genes causing the familial form of NDDs in human brains (6). For example, mosaicism from the somatic mutation of presenilin-1 was identified in 14% of cortical cells in a patient with AD. Somatic variants of β-amyloid precursor protein and somatic single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) affecting tau phosphorylation have also been reported (7–10). In addition, mosaic instability of the CAG repeat expansion in somatic tissues of Huntington’s disease (HD) mouse models and HD patient brains is associated with an earlier age of disease onset (11). This has led to a hypothesis that somatic instability may contribute to disease progression (12, 13). Somatic mosaicism of SNCA rearrangements and copy number variants (CNVs) (14, 15) were identified in patients with PD. However, disease-relevant somatic coding variants have not been consistently detected in synucleinopathies (16–18).

Brain somatic mutations could arise in the developing embryo in the progenitor cells of neurons or glia through replication errors during S phase, which has been speculated to contribute to the origin of neurodevelopmental disorders (18, 19). However, the age-dependent accumulation of unrepaired brain somatic mutations suggests that adult postmitotic neurons can acquire mutations as a result of persistent DNA damage (genotoxic stress). Genotoxic stress could be elicited by endogenous factors, such as free radicals and peroxides generated during physiologic/pathologic processes, and environmental factors, e.g., exposure to toxic chemicals and physical agents in the environment (20).

Known as a driver of cancer, low-dose environmental chemical exposure has been hypothesized to cause genomic instability, defined as higher-than-normal mutation rates (21), and precipitate somatic mosaicism in the adult brain (3). For example, PD-related environmental toxicants, such as paraquat (PQ) and rotenone, have been linked to PD due to their ability to trigger redox cycling/oxidative stress (22) that can cause damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA (23). A recent study reported that humans with genetic variants of base excision repair (BER) genes are particularly vulnerable to PQ or rotenone exposure (24); BER variants synergize with PQ exposure to increase the risk of PD. Inefficient DNA repair is an age-related disease modifier (25). Together, these findings highlight genotoxic events driving somatic mutation and cellular response/dysfunction and their relevance to the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration.

In response to DNA damage, eukaryotic cells have evolved a concerted signaling cascade, the DNA damage response (DDR), to recognize, signal, and repair DNA damage (26). Persistent genotoxic stress triggers an overzealous DDR signaling cascade, dictating the fate of cells into apoptosis or senescence to prevent the replication of a damaged genome. This serves as a safety mechanism to avoid cancer. However, in postmitotic neurons, DDR-mediated cell cycle reentry and consequential apoptosis or cell senescence have been associated with aging and neurodegeneration (27–29).

New tools are needed to understand how brain genotoxic stress can elicit neurodegeneration (16, 30). The current methods to study the impact of genotoxic stress focus on bulk or single-cell sequencing to seek disease mutations. Such an approach has been, and will continue to be, critical and needs further improvement of detection sensitivity of very-low-frequency alleles and diverse types of mutations, including SNVs, CNVs, retrotransposon insertions, repeat expansions/contractions, aneuploidy, etc. Furthermore, heterogeneity of different cell types and brain regions may result in different vulnerabilities to the acquisition of mutations. In addition, the small number of neurons with a deleterious somatic mutation(s) may have been long gone before the patient’s death. Therefore, genetic tools enabling longitudinal tracking of the fate of cells with genotoxic stress (persistent DNA damage or increased DDR) may provide sufficient spatial and temporal resolution and sensitivity to track the neurons with environment-driven genotoxic stress and disentangle the cause-and-effect relation in NDDs (30).

To design a genetic sensor to probe neuronal cell DNA damage and its surveillance and repair machinery in response to global genotoxic stress, we exploited long-standing observations that genotoxic DNA damage can increase permissivity to AAV transduction due to the role of host cell DDR as an innate antiviral defense mechanism that is inhibitory to viral life cycles. We, therefore, harnessed the single-strand recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) genome processing mechanism and the instability of a hypermutable repeat sequence to detect brain genotoxic stress and visualize neurodegeneration in postmitotic differentiated neurons. We demonstrated that our viral genetic probe is sensitive in detecting neurons with increased DDR mediated by the central orchestrator of DDR, ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM). Exposure to PQ, a PD-associated environmental toxicant, heightened neuronal genotoxic stress and elicited neuropathology revealed by single-cell analysis. The increased neuronal genotoxic stress was also probed in a humanized alpha-synuclein (aSyn) transgenic mouse model infused with aSyn preformed fibrils (PFFs). Last, we confirmed that genotoxic stress is a prominent feature in human PD patient brains. Our results revealed that environment toxicants and aSyn proteotoxicity could precipitate neuronal genotoxic stress and detailed a useful tool to study its pathogenic significance in PD.

RESULTS

Designing a genetic sensor of neuronal genotoxic stress

The idea for our neuronal DNA damage reporter originated from studies of virus-host interaction. Host cells fight against virus invasion via DDR pathways. DDR is thus detrimental to viral life cycles and can be considered as an innate antiviral host defense mechanism. Genotoxic agents, such as ultraviolet irradiation, hydroxyurea, topoisomerase inhibitors, and several chemical carcinogens, increase host cell DDR and greatly increase AAV transduction in vitro and in vivo (31–33). Although its role as a rate-limiting step of AAV transduction is controversial, increased viral second-strand DNA synthesis and DNA amplification are a major response to and may represent a marker of cellular genotoxic stress (33, 34). Host DDR pathway proteins, e.g., ATM, DNA-PKCS (35), and the MRN (Mre11/Rad50/Nbs1) complex (36), are involved in AAV genome processing, including double-strand genome conversion and genome circularization or multimerization (35). In a whole-genome screen aimed at identifying cellular factors regulating AAV transduction, a common characteristic of the most effective small interfering RNAs was the induction of cellular DNA damage and activation of a cell cycle checkpoint (37). Last, although they are episomal, processing of rAAV genomes occurs in nuclear structures that overlap with the foci of DDR proteins, e.g., the MRN complex (38). These observations shed light on the idea that an rAAV vector could be exploited as an episomal proxy in postmitotic neurons to detect host cell genotoxic stress and consequent DDR.

To further probe the host cell DNA damage repair machinery that maintains genomic stability, we engineered an error-prone microsatellite repeat into the rAAV genome. During the single- to double-strand rAAV genome conversion, microsatellite sequences not preserved faithfully by the host cell DNA damage repair mechanism(s) could “turn on” the reporter expression. Because microsatellite repeats are highly polymorphic and have mutation rates up to 1 × 10−2 per locus per generation, they have been used as sensitive indicators of genomic stability in cancer studies (39–42). These repetitive DNA repeat sequences are hotspots for genome instability, and the subsequent repair is error prone. DNA repair pathways, such as mismatch repair (MMR) in dividing cells and DDR-mediated nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) repair (43), have been shown to promote repeat instability. Previously, a single-neuron genetic strategy termed Mosaicism with Repeat Frameshift was developed to achieve sparse neuronal labeling in vivo (44), suggesting that microsatellite repeat instability can be used to probe genotoxic stress in postmitotic neurons.

On the basis of the above observations, we designed a genetic Probe with a viRal proxy for the Instability of DNA surveillance/repair in Somatic brain Mosaicism (PRISM) that harnessed the genome processing mechanism of a single-strand rAAV and the instability of a hypermutable microsatellite sequence. The hypothesized mechanisms of PRISM are shown in Fig. 1A. A microsatellite sequence (G3n+1, e.g., G22) was inserted between the translation start codon (ATG) and the protein-coding sequence of the Cre recombinase to create an out-of-frame mutation and prevent the synthesis of a functional Cre protein in mammalian cells. The synapsin promoter-driven cassette, which encompasses the frameshift mutation–dependent Cre recombinase, was then inserted into the rAAV genome between the two inverted terminal repeats.

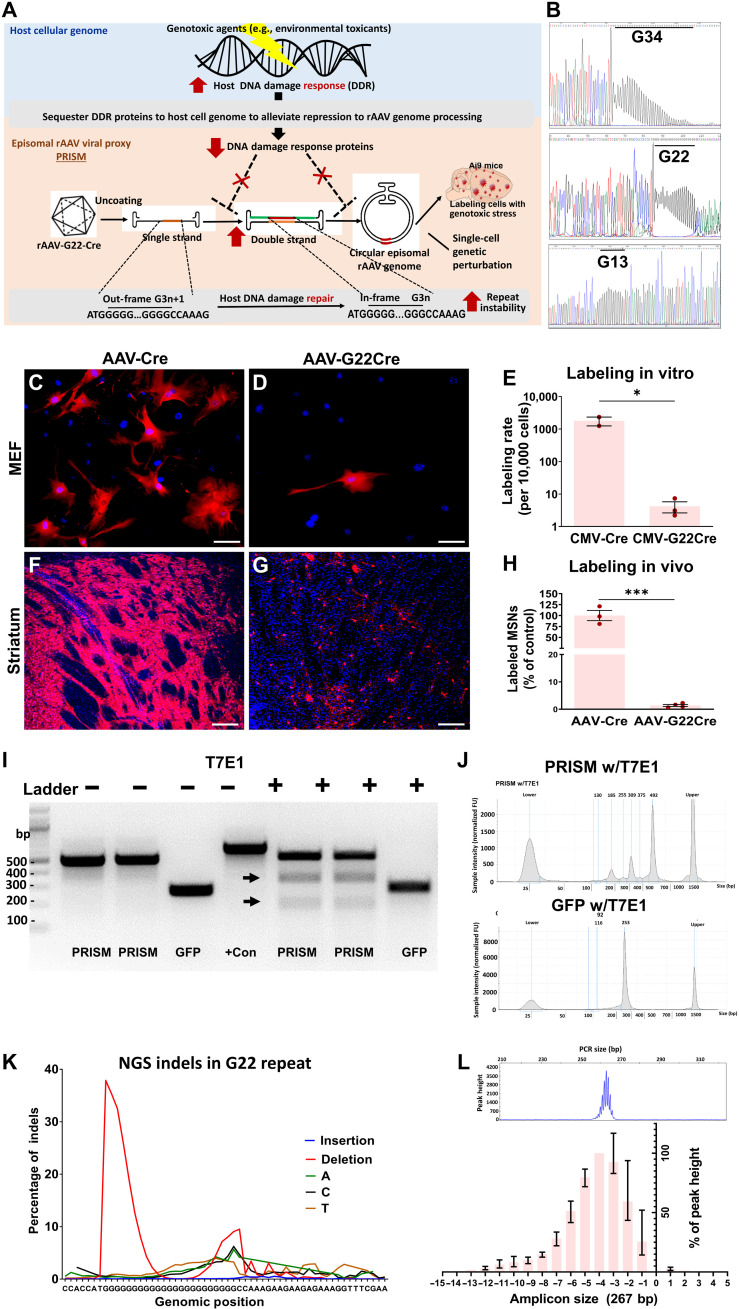

Fig. 1. Design and validation of PRISM.

(A) Schematic illustrating the mechanisms of neuronal genotoxic stress reporter. (B) Sanger sequencing to determine the stability of different lengths of the poly-G tracts in G34-RFP, G22-GFP, and G13-BFP plasmids. (C and D) Ai9 MEF transfected with an equal amount of Cre or G22-Cre plasmids. Scale bars, 25 μm. (F and G) Representative images of dorsal striatum from Ai9 mice following stereotaxic injections of either rAAV Cre or rAAV G22-Cre at equal titer. Scale bars, 50 μm. (E) The number of MEF cells expressing tdT after transfection (Student’s t test, *P < 0.05; each data point derived from three technical replicates, means ± SE, data shown as the number of tdT-labeled MEF cells per 10,000 cells on a log10 scale). (H) rAAV-G22-Cre–mediated tdT expression in significantly fewer neurons relative to rAAV-Cre (Student’s t test, ***P = 0.0002; means ± SE, n = 3 for each group). (I) DNA endonuclease T7E1-mediated mutation assay. rAAV genomic region containing G22 site or a GFP fragment was amplified from the PRISM and the rAAV-GFP coinfused mouse striatum. Arrow indicates specific cleavage products. (J) Quantification of T7E1-digested PRISM and GFP amplicons using DNA ScreenTape Analysis (Agilent). The top and bottom peaks are nonspecific, also seen in blank controls. (K) Targeted NGS was performed to analyze indels of the G22-Cre fragment amplified from mouse striatum infused with PRISM. (L) Capillary electrophoresis to determine the distribution of different sizes of the PCR amplicons containing the G22 sequence in the striatum of the animals infused with PRISM (peak heights were normalized with the highest value within the same base pair group to control for the amount of input DNA, means ± SE, n = 4).

In the cells with genotoxic stress, such as exposure to genotoxic agents, two steps permit the expression of the sensor. First, the increased DNA damage in the host cell genome sequesters DDR machinery and diverts the inhibitory DDR proteins away from the rAAV genome. The loss of function of the innate viral defense alleviates the repression of rAAV genome processing, e.g., conversion of rAAV single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) or stability of dsDNA. Second, during the double-strand rAAV genome conversion, the microsatellite repeat instability (e.g., contraction of the repeats) leads to the reversion of frameshift mutation for Cre-dependent reporter expression (Fig. 1A).

Furthermore, we used an rAAV-Cre–mediated footprinting strategy (45) to detect the transient functional dsDNA. It has been shown that only 0.1 to 1% of input rAAV vectors are stabilized and lead to transgene expression. PRISM strategy can imprint the cells as long as they harbor rAAV dsDNA carrying the in-frame Cre recombinase. The Cre-dependent reporter can then become and remain active even when rAAV genomes are later lost. The footprinting strategy can provide the following advantages. First, it reports not only the stabilization of rAAV genomes but also the transient double-strand genome conversion facilitated by genotoxic stress. Second, the reporter expression within the single cells does not depend on the copy of the rAAV genome to facilitate the consequent single-cell pathology analyses. Ultimately, with the Cre recombinase, the PRISM can serve not only as a sensor but as an actuator for single-cell genetic perturbation in cells with genomic instability; thus, it is a “seek-and-rescue” strategy.

Validation of PRISM in vitro and in vivo

To test the stability of different lengths of G repeats, we inserted the mononucleotide tracts 34G, 22G, and 13G in between the ATG and open reading frame to create the frameshift mutations in three different fluorescence proteins: red fluorescence protein (RFP), enhanced green fluorescence protein (EGFP), and blue fluorescence protein (BFP). Figure 1B shows the Sanger sequencing results of the three different constructs. In G34 and G22 constructs, sequences gradually diminish in intensity because of the long polyG. The G34 is highly unstable and results in more than 60% of cells expressing RFP, compared to 12% of cells expressing G22-GFP, when transfected in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells. Meanwhile, the G13-BFP construct resulted in almost no BFP-expressing cells after transfection. These preliminary observations suggested that the repeat length inversely correlates to its stability. Thus, we opted to use the G22 construct for the following experiments for its balance between instability and tractability.

We further validated the G22 reporter both in vitro in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells and in vivo in a Cre-dependent tdTomato (tdT) reporter mouse model (Ai9) (46). The G22-Cre vector was examined for its ability to restrict Cre-mediated tdT expression in MEF cells. Confluent MEF cells isolated from Cre-dependent reporter Ai9+/+ mice were transfected with an equal amount of either cytomegalovirus (CMV)–G22-Cre or control CMV-Cre vector DNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection, CMV-G22-Cre drastically reduced the labeling frequency to 0.2% of that of MEF cells transfected with CMV-Cre plasmid [G22-Cre: mean (M) = 4.20, SD = 2.73; control Cre plasmids: M = 1797.00, SD = 768.2; independent-sample Student’s t test, t = 4.43, df = 3, P = 0.021; each data point derived from three technical replicates] (Fig. 1, C to E).

To show that we can indeed label postmitotic differentiated neurons in vivo with this system, we substituted the CMV promoter with a neuron-specific synapsin promoter (hSYN) and packaged with the capsid rAAV-DJ8, hereinafter referred to as PRISM. Bilateral stereotaxic injections of rAAV-G22-Cre or control rAAV-Cre into the striatum were performed on homozygous Ai9+/+ mice at 2 months of age. Four weeks after the infusion, we observed PRISM-mediated sparse neuronal labeling (Fig. 1, F and G) across the striatum. The microsatellite sequence significantly restricted labeling frequency to 1.4% of transduced striatal neurons (Fig. 1, G and H) in comparison to the massive labeling in neurons transduced with the control rAAV-Cre vector (rAAV-Cre: M = 100.00%, SD = 20.17, n = 3; rAAV G22-Cre: M = 1.40%, SD = 0.73, n = 3; unpaired Student’s t test, t = 10,11, df = 5, P = 0.0002; Fig. 1H). The fully differentiated neuronal morphology and the short virus incubation time (3 weeks) exclude the possibility that the PRISM-dependent labeling was derived from adult neurogenesis.

To support the proposed mechanism of PRISM, we examined the in vivo genomic instability of the G22 tract in the rAAV genome. First, we developed an efficient mutation reporter assay to confirm the instability of the G22 microsatellite sequence on the rAAV genome in vivo using the DNA endonuclease T7E1, which is commonly used to detect double-strand breaks (DSBs) induced by the genome editing enzyme Cas9 (Fig. 1, I and J) (47). PRISM and rAAV-Synapsin-GFP vectors were coinfused in equal titer into the mouse striatum. Three weeks after the coinfusion, genomic DNA was extracted from the striatal tissue. The rAAV genomic regions containing the G22 site and the GFP fragment were amplified using Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Taq in the EnGen Mutation Detection Kit [New England Biolabs (NEB)]. Two pairs of primers were designed to generate an amplicon size of 512 base pairs (bp) (Fig. 1I) and 267 bp of the rAAV genomic regions containing the G22 site, respectively. The G22 repeat sequence was strategically designed to locate in the different positions of the amplicons. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were then denatured, reannealed, and treated with T7E1 enzyme. PCR products were cleaved in PCR amplicons containing the G22 site (Fig. 1I) but not in the control GFP rAAV genome, suggesting that the mutations are specific to the G22 site and not due to the instability inherent to the rAAV genome processing. Furthermore, T7E1 can cleave both amplicons to generate the correct sizes of the cleaved products corresponding to the G22 site position in the amplicons, suggesting that the mutations are located within or in close proximity to the G22 repeat sequence.

Next, we performed targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) on an Illumina MiSeq to analyze genetic variation in the G22 repeat on the rAAV genomic region (Fig. 1K). A 512-bp genomic region containing the G22 site was amplified from mouse striata infused with PRISM. The G22 repeat tract is highly unstable, with about 40% of counts displaying deletions in the 5′ of the G22 repeat sequence adjacent to ATG but few insertions or substitutions (Fig. 1K). We further confirmed that these deletions indeed cause the change of the repeat sizes by using capillary electrophoresis with 5-FAM (5-carboxyfluorescein) to determine the variable sizes of the PCR amplicons containing the G22 sequence in the strata of the animals (n = 4) infused with PRISM vector for 3 weeks (Fig. 1L). Fragment analysis determined that the range of base pair changes is about +1 to −11 bp, with the most common alterations being 4-bp deletions. The deletion indels and the contraction of G22 repeat size (e.g., −1, −4, and −7 deletions or G21, G18, and G15s, respectively) can lead to reversion of translation reading frame of Cre recombinase to turn on the reporter expression. All these observations suggest a predominant repeat contraction mediated by a possible NHEJ instead of an MMR repair mechanism.

Single-neuron labeling and neuronal morphology analysis

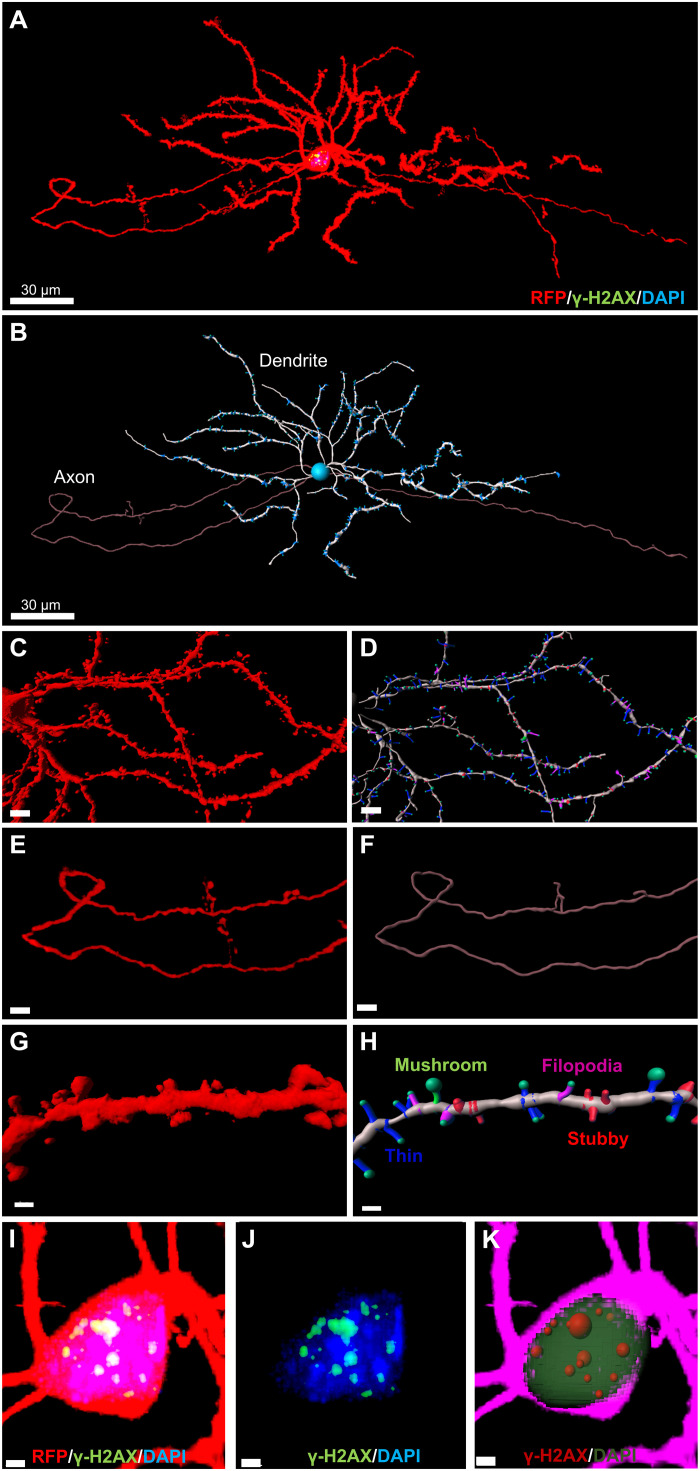

Sparse neuronal labeling throughout the PRISM-transduced brain region facilitates unobstructed visualization of neuronal morphology, while strong RFP tdT expression enables the visualization of fine anatomical structures for three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of neuronal morphology using IMARIS (Bitplane). This, in turn, allows quantitative morphological analyses, e.g., Sholl analysis. As shown in Fig. 2 (A and B), a striatal medium spiny neuron (MSN) labeled by PRISM was reconstructed using IMARIS. Fine neuronal structures were visualized, including dendrites and axons, down to the details of dendritic spines and axon buttons (Fig. 2A and movie S1). We also established a workflow to facilitate rendering and quantitative analysis of acquired images of PRISM-mediated single-neuron labeling using an automatic threshold-based dendritic and spine reconstruction function in IMARIS and open-source software R for data cleaning and analysis (fig. S1). The dendrites (Fig. 2, B to D), axons (Fig. 2, E and F), and dendritic spines (Fig. 2, G and H) of single-labeled neurons can be easily reconstructed and segmented using IMARIS. The dendritic spines were 3D-rendered (Fig. 2G) in IMARIS and further classified using a MATLAB plug-in to differentiate mushroom, stubby, thin, and filopodia spines (Fig. 2H and movie S2). Furthermore, sparse single-neuron labeling can reveal subcellular changes. By using the cell function in IMARIS, we could reconstruct and segment the cell body, nucleus, and vesicles of interest [e.g., foci of phosphorylated histone 2A (γH2AX), a substrate of ATM] in PRISM-labeled neurons (Fig. 2, I to K, and movie S3) for easy quantification of subcellular pathology. Since the neuronal structure is tightly linked to its function and pathology, sparse single-neuronal labeling and morphology analysis enable us to investigate the possible causative pathogenic role of neuronal genotoxic stress in neurodegeneration.

Fig. 2. PRISM-mediated single-neuron labeling facilitates neuronal morphology and pathology analysis.

(A) Maximal projection of a confocal image stack of a PRISM-labeled MSN in the dorsal striatum after receiving an intrastriatal infusion of PRISM vector in Ai9 homozygous mice. The cell was stained for RFP (red), γH2AX (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 30 μm. (B) Single-neuron reconstruction and segmentation of the MSN shown in (A) using IMARIS filament function (dendrite: white; axon: purple; dendritic spine: blue). Scale bar, 30 μm. (C) 3D rendering of a confocal image stack of PRISM-labeled striatal MSN. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) 3D reconstruction of dendrites (white) and dendritic spines (mushroom spine: green; stubby spines: red; thin spine: blue; filopodia spine: blue). Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) 3D rendering of a stack of confocal images of the labeled axon of a striatal MSN. Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) 3D reconstruction of the axon shown on (E). Scale bar, 10 μm. (G) 3D rendering of a segment of the dendrite from the MSN shown in (C). Scale bar, 2 μm. (H) Dendritic spine reconstruction and classification using a MATLAB plugin in IMARIS (mushroom spine: green; stubby spine: red; thin spine: blue; filopodia spine: purple). Scale bar, 2 μm. (I and J) Representative maximal projection of a stack of confocal images of a PRISM-labeled striatal MSN immunostained for γH2AX (γH2AX foci: green; PRISM: red; DAPI: blue). Scale bars, 2 μm. (K) Reconstructed and segmented cell body (purple), nucleus (green), and vesicles of interest (γH2AX foci in red spheres) for quantification of subcellular pathology.

PRISM reports neuronal genotoxic stress inflicted by frameshift mutagen and DNA DSB inducer

To explore the mechanism of action of the genomic reporter in postmitotic neurons, we first examined whether the PRISM vector can report the genotoxic stress elicited by 9-aminoacridine (9-AA), an acridine derivative known to induce frameshift mutations (48). 9-AA effectively induces −1 frameshift mutations in a run of guanine residues and is thus well suited to test PRISM’s proposed mechanism of action. Stereotaxic infusion of PRISM alongside an 8 μM dose of 9-AA (shown to induce abnormal nuclear foci in eukaryotic cells; 16 μM is the peak concentration to induce mutations in Escherichia coli) had no obvious neurotoxic effects but induced robust reporter expression in the hippocampus (fig. S2, A and B).

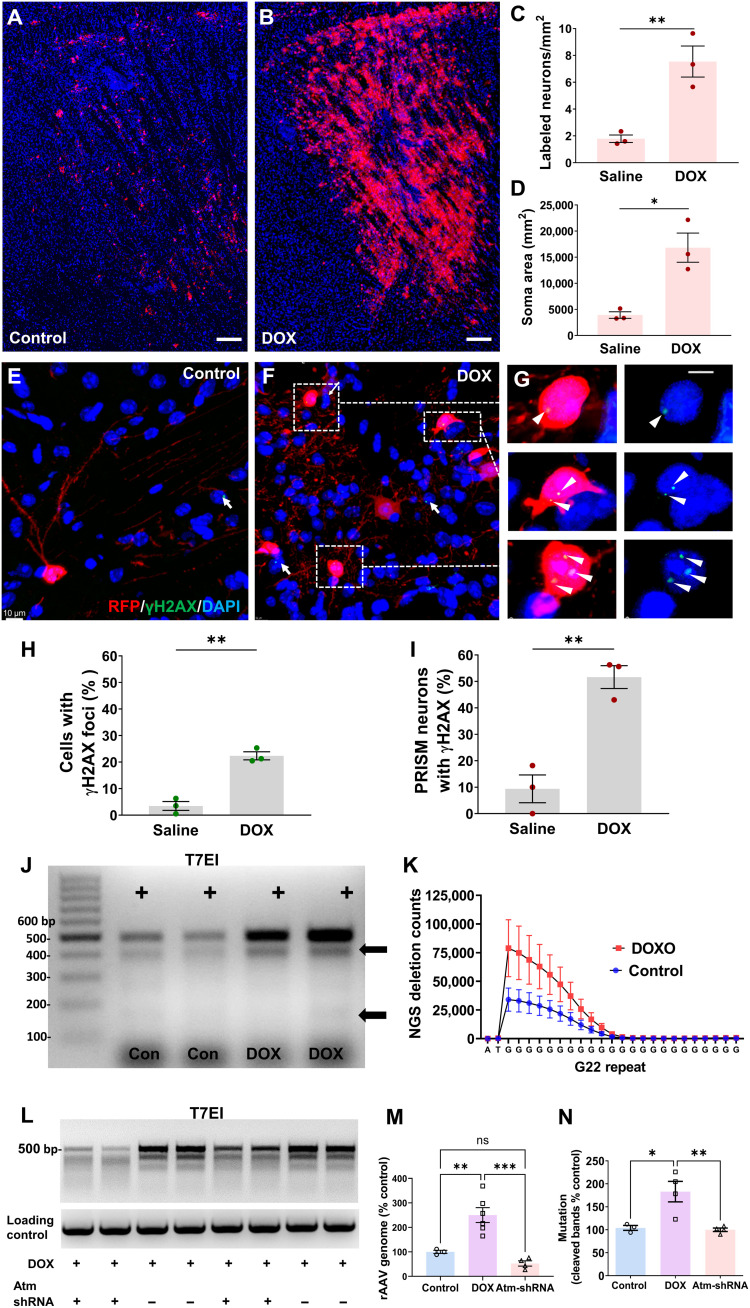

Next, we examined whether PRISM could detect DNA DSBs in postmitotic neurons. Doxorubicin (DOX) is a known DNA DSB inducer that intercalates DNA and dysregulates DDR mediated by ATM, the master orchestrator of the DDR pathways (49, 50). We performed bilateral intrastriatal infusion of PRISM [109 viral genomic copy number (VG) per mouse] with 200 μM DOX or vehicle control in adult Ai9+/+ mice and sacrificed 4 weeks later. DOX produced a notable and statistically significant increase in the number of neurons labeled by PRISM in comparison to vehicle control in the striatum (Fig. 3, A and B, and fig. S2, C to F). DOX increased RFP labeling frequency by 400% as measured by cell counts (Fig. 3C), the total soma area (Fig. 3D), and the total fluorescence intensity in the striatum (fig. S2G). The number of labeled MSNs was significantly higher in the DOX (M = 7.54/mm2, SD = 1.999, n = 3)–treated group than the saline (M = 1.79/mm2, SD = 0.49, n = 3) group (independent-sample Student’s t test, t = 4.84, df = 4, P = 0.008; Fig. 3C). Total area of labeled somas was also significantly higher in the DOX group (DOX: M = 16827 μm2, SD = 4833, n = 3; saline: M = 3924 μm2, SD = 1078, n = 3, independent-sample Student’s t test, t = 4.51, df = 4, P = 0.01; Fig. 3D). Because PRISM fluorescence is derived from a host-encoded fluorescence transgene that operates in a binary manner, fluorescent intensity should not be modulated by DOX directly. To confirm this, we coinfused Ai9 mice with rAAV-GFP and PRISM, along with either saline or DOX (fig. S3). DOX caused a significant increase in the mean intensity of rAAV-GFP–labeled neurons but not in PRISM-labeled neurons of the same animals (fig. S3, A to D). We also observed comparable fluorescence intensity between rAAV-GFP + saline, PRISM + saline, and PRISM + DOX, whereas rAAV-GFP + DOX resulted in a significant increase in peak fluorescent intensity (fig. S3, E to H). This observation confirmed that PRISM labeling and assay outcome are not products of DOX-mediated transgene overexpression.

Fig. 3. PRISM reports neuronal genotoxic stress inflicted by DNA DSB inducer.

(A and B) Representative confocal images of reporter expression in mouse striatum 4 weeks after rAAV-PRISM vector infusion. Equal volume and titer of the PRISM with either 200 μm DOX or saline (control) were administered. Scale bars, 200 μm. (C) The number of labeled MSNs was significantly higher in the DOX-treated group than in the saline control group (t test, **P < 0.01; means ± SE, n = 3). (D) The total area of labeled somas was significantly higher in the DOX group than in the saline group (t test, *P = 0.01; means ± SE, n = 3). (E to G) Representative images of PRISM-labeled dorsal striatal MSNs immunostained for γH2AX in saline- or DOX-treated animals. White arrows and white triangles indicate γH2AX foci in non-PRISM–labeled or PRISM-labeled cells, respectively. Scale bars, 10 μm (E and F) and 2 μm (G). (H and I) γH2AX labeling frequencies in dorsal striatal cells and in PRISM-labeled neurons were quantified separately (t test, **P < 0.01; means ± SE, n = 3). (J) T7E1 assay demonstrated that DOX increased both the rAAV genome and mutations in the G22 site. (K) NGS counts of deletion mutations in the G22 site within the amplicons from the striatal tissue treated with DOX or saline control (two-way ANOVA, n = 3). (L) rAAV-Atm-shRNA infusion in striatum reduced the DOX-induced rAAV genomic DNA amplification and mutations in the G22 site, as shown in the T7E1 assay. (M) RT-PCR quantification of rAAV genomic DNA flanked the G22 site (one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test, **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, means ± SE). (N) DOX-induced total mutation on rAAV-PRISM after rAAV-Atm-shRNA infusion as shown in the quantification of the amount of the cleaved bands in T7E1 assay (sum of the band intensity of the two major cleaved fragments, one-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, means ± SE). ns, not significant.

Mechanism of action of PRISM couples to neuronal DNA damage and DDR

To confirm that PRISM genetically labels postmitotic neurons with increased neuronal DNA damage and overactive DDR signaling and to establish PRISM’s sensitivity to DDR activity at a single-cell resolution, we used confocal microscopy and IMARIS Co-loc function to quantify the frequency of the relevant DSB markers γH2AX (Fig. 3, H and I) and 8OHdG (fig. S4, F and G) colocalized within all dorsal striatal cells and within the subpopulation of PRISM-positive dorsal striatal neurons. As expected, the labeling frequency of γH2AX was significantly higher after DOX exposure both for the entire population (P = 0.001) and for the PRISM-positive (P = 0.0034) neuronal population (Fig. 3, H and I). Notably, after DOX treatment, γH2AX was expressed in 21% of cells, which increased more than twofold in the subpopulation of PRISM-positive neurons. Thus, PRISM was enriched in the γH2AX-positive neuronal population. It is relevant to note that the lack of PRISM-mediated RFP expression in a neuron with γH2AX does not necessarily suggest that PRISM failed to detect genotoxic stress; rather, the neuron may have never been transduced with rAAV-PRISM. Last, we performed high-resolution confocal imaging and displayed genetically labeled neurons in Blend mode (IMARIS) to visualize cellular localization of nuclear γH2AX, which revealed exquisite details and provides a powerful approach to track pathologic changes in terminally differentiated neurons experiencing genotoxic stress (fig. S4, A and B).

In addition to inducing DSBs, DOX is a potent reactive oxygen species inducer. Oxidation of nucleotides can result in single-strand breaks, as well as DSBs if numerous bases from both strands are oxidized within close proximity. This may engage DDR machinery and therefore jeopardize genomic integrity. We examined PRISM sensitivity toward DNA oxidation by measuring 8OHdG, a marker of DNA oxidative damage (Fig. 4, F and G, and fig. S4, D and E). 8OHdG staining covered significantly more (t = 2.950, df = 6, P = 0.0256; fig. S4F) striatal area in the DOX (M = 4.871, SD = 3.194, N = 4)–treated group relative to the saline (M = 0.153, SD = 0.151, N = 4) control group; likewise, the percentage of PRISM-labeled neurons with 8OHdG expression was significantly higher (t = 2.465, df = 6, P = 0.049; fig. S4G) in the DOX (M = 9.05, SD = 7.343, N = 4)–treated group than in the saline (M = 0, SD = 0, N = 4)–treated group. Therefore, PRISM labeled a subpopulation of neurons enriched with 8OHdG lesions. Double staining showed that 8OHdG has both nuclear and cytoplasmic distribution, with cytoplasmic 8OHdG colocalized with the mitochondria marker COX IV (fig. S4, H to J) in both PRISM-labeled neurons in mouse and DA neurons in human brains.

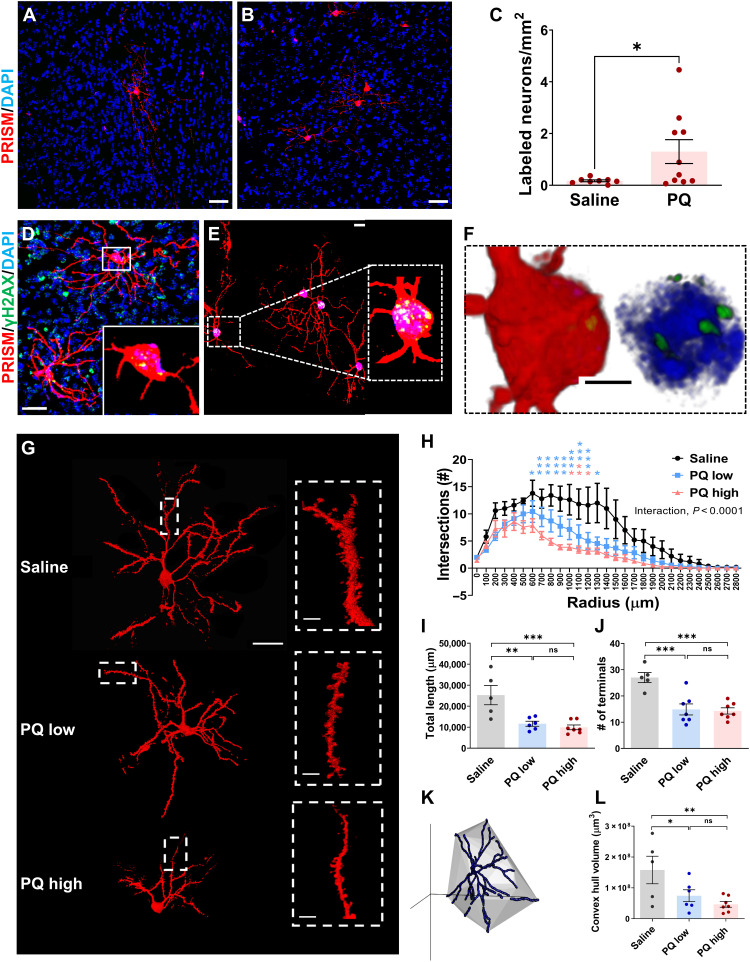

Fig. 4. PRISM detects genotoxic stress elicited by PD-associated environmental toxicant, PQ.

(A and B) Representative confocal images of PRISM-mediated labeling of striatal neurons in saline- or PQ-treated mice. Scale bars, 10 μm. (C) Quantification of PRISM-labeled neurons (number of PRISM-labeled neurons per square millimeter) in the PQ- or saline-treated group (independent t test; *P = 0.0243). (D to F) Confocal imaging stack of MSNs labeled by PRISM with nuclear γH2AX foci (green) from mice treated with PQ, shown as max projection and as 3D (F) rendering in blend mode (IMARIS). Scale bars, 30, 20, and 3 μm. (G) Representative confocal images of single MSNs from saline, PQ-low, and PQ-high dose groups. Scale bars, 10 and 2 μm for inserts. (H) Comparison of dendritic arborization complexity using Sholl analysis of the reconstructed single MSNs from saline, PQ-low, and PQ-high dose groups {two-way ANOVA factored with treatment and number of branch intersections within 100-μm concentric shells; interaction [F(56, 448) = 2.624, P < 0.0001]}. (I to L) Quantification of total neurite length (I), terminal number (J), and 3D convex hull (K and L) volume of the reconstructed single MSNs from saline, PQ-low, and PQ-high dose groups [one-way ANOVA, F(2, 15) = 11.20, P = 0.0011; F(2, 16) = 7.082, P = 0.0003; F(2, 15) = 5.142, P = 0.0199]. Pairwise comparison of means indicates that all three variables of the saline group were significantly larger than that of the PQ-low and PQ-high groups [LSD, (I) P = 0.0016 and P = 0.0005; (J) P = 0.0003 and P = 0.0002; (L) P = 0.0376 and P = 0.0066; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001].

To further validate DDR activation, we examined the aberrant expression of tumor suppressor P53-binding protein 1 (53BP1), another downstream effector of ATM, in brain regions (dorsal striatum) labeled by PRISM (fig. S5, A to D). Striatal immunostaining of 53BP1 was significantly higher in the DOX (M = 206.6%, SD = 84.69%, n = 5)–treated group than in the saline (M = 100%, SD = 19.92%, n = 4) group (unpaired independent-sample Student’s t test, t = 2.433, df = 7, P = 0.045; fig. S5E).

To support the hypothesized mechanism of action of the PRISM reporter (Fig. 1A), we determined whether DOX can increase the rAAV genome DNA 1 week after striatal coinfusion of PRISM with DOX or saline. Using real-time PCR to amplify the rAAV genomic region flanking the G22 track and a housekeeping gene (GAPDH) as the loading control, we found that DOX significantly increased rAAV-G22-Cre genome [one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post hoc test, F(2, 10) = 18, P = 0.0005, control versus DOX, *P < 0.01; means ± SE; Fig. 3, J (top band) and M]. The amplified rAAV genome suggests an increase in the conversion of DNA double-strand or dsDNA stabilization, supporting the proposed mechanism as illustrated in Fig. 1A. We next performed the T7E1 assay and demonstrated that DOX could also significantly increase the total amount of the cleaved products, suggesting an increase in the indels in the G22 site of the rAAV genomic region [Fig. 3J (cleaved products) and quantification in Fig. 3N; one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, F(2, 8) = 10.72, P = 0.0054, control versus DOX, *P = 0.015; n = 3 per group]. NGS on an Illumina MiSeq was used to detect significantly higher counts of deletion mutants within the genomic region of the G22 site in the DOX treatment group in comparison to the saline control group [two-way ANOVA, G positional effect, F(24, 100) = 12.42, P < 0.0001; DOX treatment effect, F(1, 100) = 21.98, P < 0.0001; interaction F(24, 100) = 1.819, P = 0.0213, n = 3 per group; Fig. 3K]. These results confirm that G22 microsatellite instability increases along with rAAV genome processing, e.g., single- to double-strand conversion, supporting the proposed mechanism as illustrated in Fig. 1A. We observed an increase in the total amount of cleaved products in the DOX group that drives the reporter expression but not the ratio of cleaved/uncleaved amplicons. The inherent instability of the G22 track may be more related to G repeat length or host cell DNA damage repair capability.

To establish that PRISM genetic labeling directly depends on DDR activation, we genetically reduced DDR signaling using an Atm short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to knock down Atm as described previously (51). Atm-shRNAs (targeting sequence: CGCTTAGCTGGAGGCTTAAAT) targeting exon 52 of Atm protein-coding sequence (CDS) were packaged in a single-strand AAV-PHP.eB vector. rAAV-Atm-shRNAs (109 VG) or nontargeting AAV control was infused bilaterally into the striatum 2 weeks before PRISM vector (109 VG) and DOX (200 μM) coinfusion. Genomic DNA was prepared from the harvested striatal tissue 1 week after introducing the PRISM vector. We observed that rAAV-shRNA infusion blocked the DOX-elicited amplification of the rAAV-PRISM genome (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, DOX versus Atm-shRNA: P < 0.001; Fig. 3, L and M). T7E1 assay further demonstrated that AAV-shRNA infusion significantly reduced DOX-elicited increase in the total amount of mutations of the G22 repeat (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, DOX versus Atm-shRNA: P < 0.001; Fig. 3, L and N). All these results support the proposed mechanism of action of PRISM reporter: Genotoxic stress activates host cell DDR to facilitate the rAAV genome processing. i.e., dsDNA synthesis. During the single- to double-strand genome conversion, instability of the microsatellite sequence (deletion mutations) can shift the open reading frame of Cre recombinase to lead to reporter expression.

Neuroinflammation

To determine whether the neuronal genomic stress induced by DOX is pathogenic, we examined neuroinflammation in the striatum 4 weeks after DOX treatment. In the regions heavily labeled with the neuronal genotoxic stress reporter, we identified DOX-elicited robust microgliosis (fig. S6, A and B) and astrogliosis (fig. S6, E and F). Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (IBA1) immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining indicates both an increase in IBA1 expression and activation of microglia (fig. S6, C and D). The total area of microglial immunostaining was significantly higher in the DOX (M = 1175 μm2, SD = 550.1, n = 5)–treated group than in the saline (M = 138.8 μm2, SD = 148.1, n = 4) group (independent-sample Student’s t test, t = 3.617, df = 7, P = 0.009; fig. S6D). The DOX (M = 0.78, SD = 0.31, n = 10 cells from four animals)–treated group exhibited reactive microglia morphology, shown as a significant shift in the ratio of deramified microglial to total microglial when compared to the saline (M = 0.1, SD = 0.224, n = 5 cells each from three animals) group (independent-sample Student’s t test, t = 4.361, df = 13, P = 0.0008; fig. S6D). Likewise, immunostaining of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) was significantly higher in the DOX (M = 143.7%, SD = 25.95, n = 4) group than in the saline (M = 100%, SD = 14.09, n = 4) control group (independent-sample t test, t = 2.895, df = 6, P = 0.0275; fig. S6G). Collectively, the observed reactive neuroinflammation suggests that DOX-elicited neuronal genotoxic stress is associated with neuropathology.

PD-associated environmental toxicant PQ elicits neuronal genotoxic stress

Since we have demonstrated that PRISM reporters can detect neurons with oxidative DNA damage, DNA DSBs, and increased DDR, next, as a proof of principle, we asked whether systemic subchronic exposure to PQ can elicit genotoxic stress in postmitotic neurons in adult mice. Using a widely used PQ administration regimen [10 mg/kg PQ, intraperitoneal injection (i.p.), once per week for 3 weeks] (52, 53), the PQ group exhibited a significant and approximately 10-fold increase in the number of PRISM-labeled neurons. PQ-elicited genetic labeling was detected in the striatum, cortex, and hippocampus (Fig. 4, A and B, and fig. S7, A to F). There is a significant difference between the number of the PRISM-labeled neurons for saline (M = 0.1714 neurons/mm2, SD = 0.1034, n = 8)– and PQ (M = 1.302 neurons/mm2, SD = 1.460, n = 10)–treated groups (independent-sample Student’s t test; t = 2.173, df = 16, P = 0.045; Fig. 4C). At the time of sacrifice, animals did not show any overt behavioral abnormalities, consistent with previous reports (53).

To support our results, IHC and immunofluorescence (IF) were used to quantify γH2AX levels. We found that the number of cortical neurons with γH2AX foci and the intensity of γH2AX foci were significantly higher in the PQ group than in the saline group (independent-sample test, t = 4.619, df = 24, P = 0.0001; fig. S8, A to F). Mean intensity of γH2AX/neuron in the hippocampus dentate gyrus was also significantly (t = 3.74, df = 111, P = 0.0003) higher in the PQ (M = 107.1, SD = 11.40, N = 60) group relative to the saline (M = 100, SD = 8.21, N = 53) group (fig. S8, G to J). These concomitant results confirm that DDR signaling is elevated in mice exposed to PQ, which is accurately detected by PRISM. To link elevated DDR to PRISM-labeled neurons at the single-neuron resolution, we performed immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy. Numerous PRISM-labeled neurons exhibit γH2AX foci in the striatum and hippocampus of PQ-exposed animals (Fig. 4, D to F, and fig. S7, G and H). These findings serve to strengthen our observation that systemic PQ exposure elicits genotoxic stress in terminally differentiated neurons that is sensitively detected by PRISM reporters at single-neuron resolution.

Environment-driven neuronal genotoxic stress is associated with neuropathological changes

Next, we sought to link environment-driven neuronal genotoxic stress with its biological consequence by examining subtle morphological changes in single-labeled terminally differentiated neurons. We imaged and reconstructed 3D dorsal striatal MSNs from animals treated with the aforementioned low-dose PQ regimen (10 mg/kg, i.p., once per week for 3 weeks) and a high-dose PQ regimen (10 mg/kg or saline, i.p., twice per week for 3 weeks) (Fig. 4G). Arbor complexity and dendritic morphometric parameters were statistically analyzed. Sholl analysis revealed dose-dependent neurodegenerative-like changes [two-way ANOVA, the interaction between the number of dendritic branch intersections within each concentric 100-μm shell and toxicant treatment, F(56, 448) = 2.624, ***P < 0.0001; Fig. 4H]. Total neurite length and the number of terminals were significantly different between the three treatment groups. Total neurite length and the number of terminals are significantly different between the three treatment groups [one-way ANOVA, F(2, 15) = 11.20, **P = 0.0011; F(2, 16) = 7.082, ***P = 0.0003; Fig. 4, I and J]. Pairwise comparison using Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test indicates that the neurite length of the saline group (M = 25,287 μm, SD = 10,272, n = 5) was significantly larger than that of PQ-low (M = 14,231, SD = 7326 μm, N = 7) and PQ-high (M = 9939 μm, SD = 3004, n = 7) groups (LSD, P = 0.0016, P = 0.0005; Fig. 4I). Likewise, the terminal number in the saline (M = 27, SD = 4.3, N = 5) group was significantly more than that in the PQ-low (M = 14.86, SD = 5.55, N = 7) and PQ-high (M = 14.29, SD = 3.15, n = 7) groups (LSD, P = 0.0003, P = 0.0002; Fig. 4J). Compared to the saline group, neuronal 3D convex hull volume was significantly reduced by 52.82 and 70.51% in the PQ-low and PQ-high group, respectively [one-way ANOVA, F(2, 15) = 5.142, P = 0.0199; Fig. 4, K and L]. Pairwise comparison of means using LSD post hoc test indicates that the 3D convex hull volume of the saline (M = 1.57 × 108 μm3, SD = 9.9 × 107 μm3, n = 5) group was significantly larger than that of PQ-low (M = 7.4 × 107 μm3, SD = 4.7 × 107 μm3, n = 6) and PQ-high (M = 4.6 × 107 μm3, SD = 2.5 × 107 μm3, n = 7) groups (LSD, P = 0.0376, P = 0.0066; Fig. 4L). There were no differences between low- and high-dose PQ groups for branch length, terminal number, or convex hull volume (P > 0.05). Our results associate the increased neuronal DNA damage to neuropathology that may lead to neurodegeneration.

The most affected brain region in PD is distinguished by a high rate of neuronal genotoxic stress

NDDs are characterized by selective region- and cell type–specific pathology. However, the mechanism and molecular substrates of such selective vulnerability are unknown. We set out to determine whether neuronal genomic instability could contribute to selective neurodegeneration by examining whether the most affected cell type in PD, the nigral dopaminergic (DA) neurons, had a high baseline of neuronal DDR and whether environmental toxicant exposure could precipitate cell type–specific neuronal DDR. To avoid a possible pharmacokinetic difference in striatum and nigra, PQ was intracerebrally coinfused with PRISM, respectively, into the two brain regions. We analyzed animals that received bilateral intranigral or intrastriatal coinfusions of PRISM with a very low dose of PQ (3 nM) that does not cause obvious DA neuron toxicity or behavioral changes in vivo, as previously reported (54). Intranigral infusion at this dose of PQ significantly reduced striatal tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) terminal IHC staining (fig. S9, A and B). Striatal TH terminal density was significantly lower in the PQ (M = 88.31, SD = 6.94, n = 4)–treated group than in the saline (M = 115.1 SD = 4.94, n = 3) group (independent-sample Student’s t test, t = 5.651, df = 5, P = 0.0024; fig. S9C). There was no significant difference between the number of TH-positive nigral neurons between the saline (M = 78.25, SD = 14.99, N = 4)– and PQ (M = 72.88, SD = 21.54, n = 4)–treated groups (fig. S9E). There was also no significant or detectable difference between the soma area of TH nigral neurons between the saline (M = 11,826 μm2, SD = 3132 μm2, N = 4)– or PQ (M = 10,415 μm2, SD = 3838 μm2, N = 4)–treated groups (fig. S9D), suggesting no noticeable neurodegenerative changes at this low dose of PQ administration.

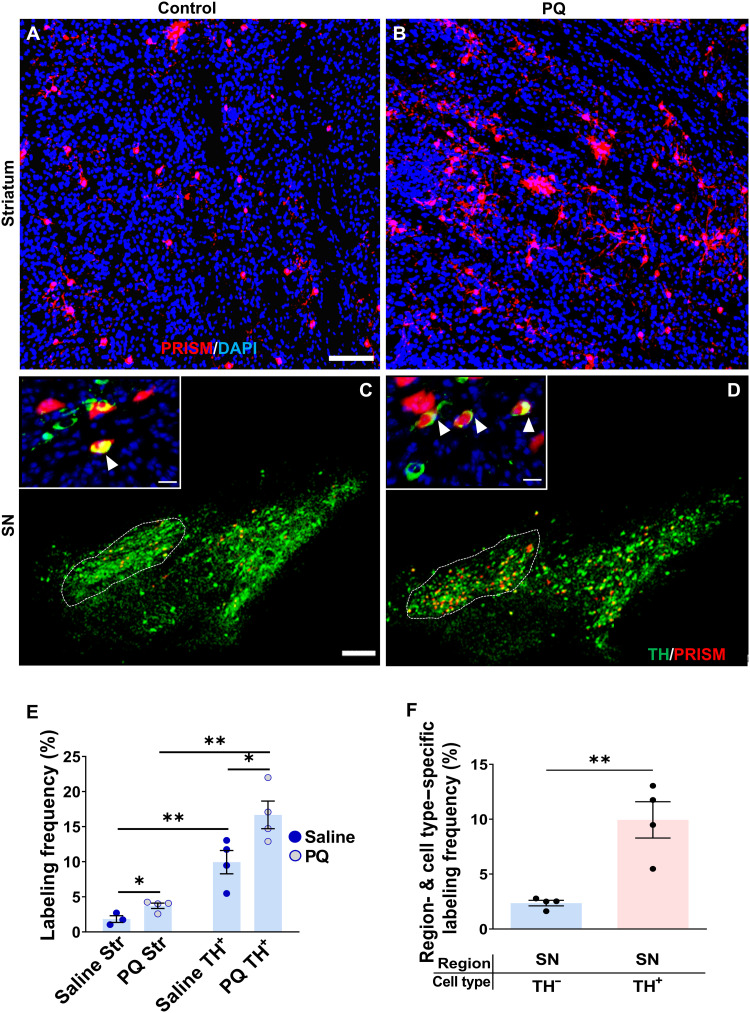

Low-dose PQ intracerebral infusions caused a significant increase in the number of striatal (Fig. 5, A and B) and substantia nigra (SN) (Fig. 5, C and D) neurons labeled with PRISM reporter. Cell type–specific PRISM labeling in the SN pars compacta (SNpc) was determined by double staining for TH to identify neurons coexpressing TH and PRISM-mediated RFP (Fig. 5, C and D). We quantified the number of striatal MSNs, nigral DA neurons, and nigral non-DA neurons labeled with the neuronal genotoxic stress reporter, with and without PQ treatment. A two-way ANOVA factoring treatment and cell type identified that both treatment and cell type had a significant influence on PRISM-mediated neuronal genomic instability labeling, with cell type having a far more significant and larger effect than PQ treatment (Fig. 5E). Between-subject effects revealed a significant effect of both treatment (P = 0.0116) and cell type (P < 0.0001) on PRISM labeling (i.e., neuronal genomic instability). Independent t tests were performed to compare simple main effects of the toxicant PQ and region specificity on reporter labeling (Fig. 5E). At baseline without PQ exposure, the PRISM reporter labeled 1.8% of striatal MSNs and 10% of nigral DA neurons (t = 4.048, df = 5, P = 0.0098). A larger and more significant increase occurred between the nigra and striatal regions after PQ exposure (t = 6.454, df = 6, P = 0.0007). Furthermore, PQ exposure caused a significant increase in PRISM labeling in both regions (striatum, t = 3.109, df = 5, P = 0.0266; nigra, t = 2.615, df = 6, P = 0.0398). Together, our results indicate that the PQ induced higher genotoxic stress in SN. Nearly 4% of striatal MSNs were labeled, while more than 16% of nigral DA neurons were labeled. Moreover, nigral DA neurons exhibited higher baseline levels of genotoxic stress relative to nigral non-DA neurons (Fig. 5F). PRISM labeling was more than fivefold higher in nigral DA neurons than neighboring non-DA neurons (9.94% of TH+ cells versus 2.36% of TH− cells) (independent-sample Student’s t test; t = 4.519, df = 6, **P = 0.004). The latter analysis required the identification of dopaminergic neurons labeled by PRISM (coexpression of TH and PRISM). In summary, these results support the idea that high levels of SNpc-specific neuronal genomic DNA damage at baseline and after PQ exposure may contribute to selective DA neuronal vulnerability in PD.

Fig. 5. Paraquat elicits genotoxic stress in DA neurons.

Representative confocal images of striatum (A and B) (scale bar, 100 μm) and nigra (C and D) (scale bars, 300 μm) coinjected with PRISM and PQ (3 nmol) or saline (scale bars, 100 μm). White triangles [(C) and (D) inset] (scale bars, 15 μm) indicate PRISM-labeled DA neurons. (E) Quantification of PRISM labeling frequency in the striatal neurons or nigral DA neurons with the local infusion of PQ (3 nmol) or saline [two-way ANOVA factored by treatment (saline and PQ) and brain region (striatum and SN); between-subject effects of treatment (P = 0.0116) and brain region (P < 0.0001); interaction effect between PQ and region on PRISM labeling (P = 0.118)] (Post hoc test: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (F) Quantification of PRISM labeling frequency in the nigral DA neurons (TH+) or neighboring non-DA neurons (TH−) with the local infusion of PQ (3 nmol) or saline. PRISM labeling was significantly higher in nigral DA neurons than in neighboring non-DA neurons (independent t test; **P = 0.004).

Human α-synuclein proteotoxicity and propagation increase neuronal genotoxic stress in a humanized mouse model

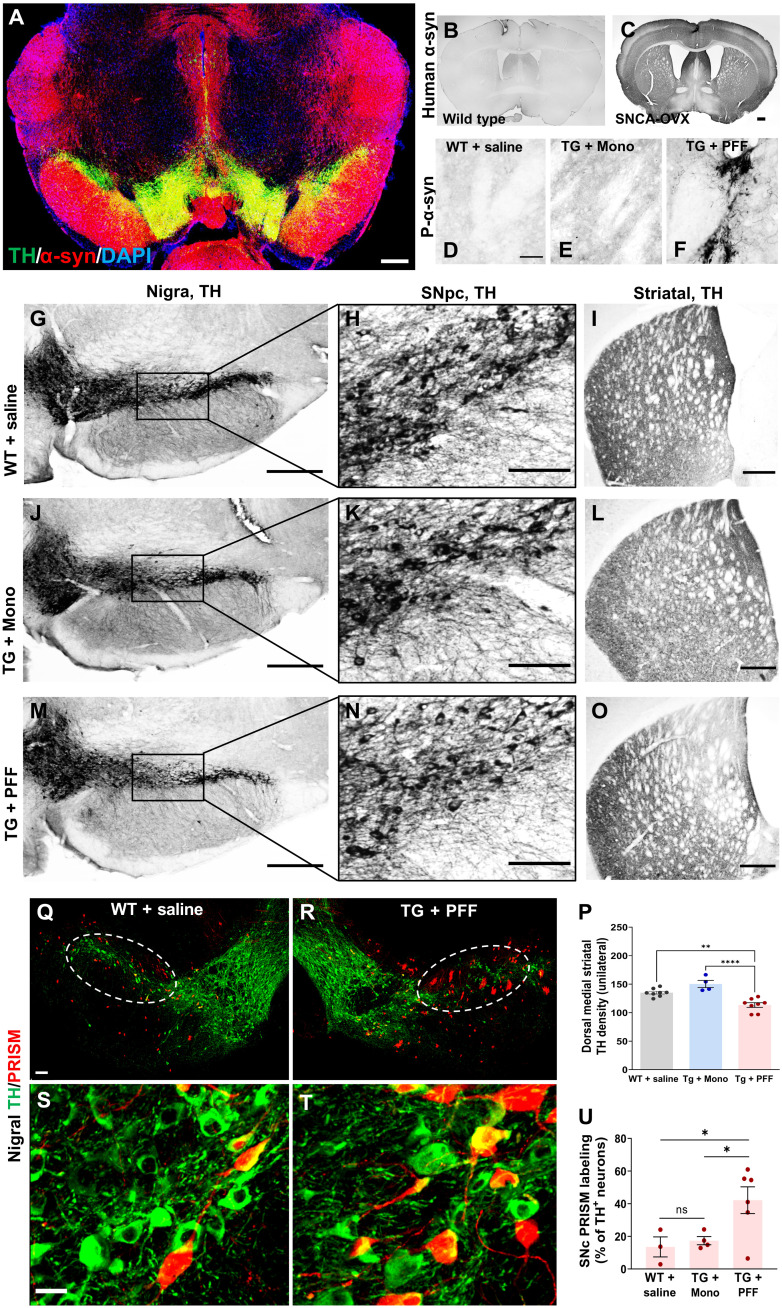

Converging genetic, pathological, and molecular studies suggest that aSyn is a central etiological factor in the onset and progression of PD (55). PD-associated environmental toxicants, such as PQ, up-regulate and aggregate aSyn in vivo (52, 56). Thus, we next examined whether proteotoxicity of aSyn can increase neuronal genotoxic stress in a novel humanized mouse model of aSyn propagation. We started with the bacterial artificial chromosome SNCA-OVX human aSyn–overexpressing mouse model because of its high construct validity (47). The human aSyn transgene contains full-length human SNCA with complete cis-regulatory elements. Human SNCA is overexpressed throughout the brain of the transgenic animal (TG) (Fig. 6A) and is absent in wild-type (WT) animals (Fig. 6, B and C). These animals develop a subtle behavioral phenotype around 16 months of age. To model the proteotoxicity of aSyn and exaggerate the pathological phenotype, we coinfused PFFs of human recombinant α-syn protein, monomer α-syn (MONO), or saline (vehicle) into the bilateral striatum at 6 to 7 months of age. Three months later, animals were subjected to behavioral and histopathological analysis. Phosphorylated (Ser129) aSyn (P-aSyn) is the primary synuclein isoform comprising Lewy Body (LB) inclusions in the brains of patients with PD. SNCA-OVX mice receiving PFF infusions exhibited robust P-aSyn immunostaining, while WT + saline and TG + Mono animals lacked detectable P-aSyn immunostaining (Fig. 6, D to F). Furthermore, we used a human aSyn–specific antibody (57) and observed a massive accumulation of striatal, as well as nigral and cortical, proteinase K–resistant (PK-R) aSyn in the TG + PFF group but not in the TG + saline group (fig. S10). Insoluble PK-R aSyn is indicative of toxic aSyn aggregation. The pathological consequence of P-aSyn was evident by observed gross morphological structures, including highly condensed fibrils and aggregates throughout the soma and dendrites.

Fig. 6. Human aSyn proteotoxicity and propagation increase neuronal genotoxic stress in a humanized mouse model.

(A) Representative confocal image showing nigral TH expression (green) and human α-syn overexpression (red) with nuclear counterstain (DAPI) in transgenic SNCA-OVX mice. (B and C) Representative images of human aSyn IHC staining in WT (B) and transgenic SNCA-OVX mice (C). Transgenic SNCA-OVX (TG) mice received intrastriatal infusions of human aSyn PFF or human aSyn monomers, and WT animals received vehicle only. Representative images of dorsal striatum illustrating immunostaining of phosphor (P)–aSyn in WT + saline, transgenic SNCA-OVX (TG) + monomer, and TG + PFF groups (D to F). Nigral (G, J, and M), SNpc DA neurons (H, K, and N), and striatal (I, L, and O) TH immunostaining in the TG + PFF, WT + saline, and TG + monomer groups, respectively (G to I, J to L, and M to O). (P) Striatal DA TH staining density is significantly lower in the TG + PFF group than in the WT + saline and TG + Mono groups [one-way ANOVA, F(2, 17) = 8.6, P = 0.013, **P = 0.0014, and ****P < 0.0001]. (Q to T) Confocal images of SN TH (green) and PRISM-mediated RFP expression (red) in control (Q and S) or TG + PFF (R and T) animals that received intranigral infusions of PRISM. (U) PRISM labeling frequency in SNpc is shown in % of TH-positive neurons. LSD post hoc test revealed that the PRISM labeling frequency in the TG + PFF group was significantly higher than that in the WT + saline or TG + Mono groups (one-way ANOVA, F = 8.94, P = 0.032, followed by LSD post hoc test, *P < 0.05).

To determine whether P-aSyn elicited proteotoxicity and PD-like pathology, we examined nigrostriatal pathology. Striatal TH terminal density was significantly reduced in the TG + PFF group but not in the TG + Mono group [one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test, F(2, 17) = 19.75, P < 0.0001, WT + saline versus TG + PFF: P = 0.079; WT + saline versus TG + Mono, P = 0.0616; Fig. 6, I, L, O, and P]. Notably, most animals in the variable group displayed TH reduction in the dorsal quadrant of the striatum, which is the region affected earliest in PD progression (58). The TG + Mono group was included in the analysis to rule out the possibility of observed pathology resulting from the presence of a recombinant exogenous protein product. Stereological estimation of TH cell counts in the SNpc was performed. It did not reveal a statistically significant loss of DA neurons in TH + PFF group (t = 0.07103, df = 8, P = 0.9451; Fig. 6, G, J, and M, and fig. S11I). These results established that proteotoxicity of aSyn led to the posttranslational conversion of aSyn to toxic isoforms that aggregated and elicited nigrostriatal pathology.

We then addressed the outcome that these histological changes had on motor behavior using established behavioral assays, including spontaneous rearing, beam traversal, adhesive removal, open field (OF), and accelerating rotarod (fig. S11, A to G) (57). The TG + PFF group showed a significant decrease (independent Student’s t test; t = 2.427, df = 13, *P = 0.0305) in spontaneous rearing activity (control, M = 39.86, SD = 7.755, N = 7; TG + PFF, M = 29.63, SD = 8.467, N = 8) (fig. S11A). We also detected sensorimotor function impairment using an adhesive removal test. The control group contacted the adhesive in half the time of the TG + PFF group (independent Student’s t test, t = 2.263, df = 13, P = 0.0414; control, M = 1.405, SD = 0.4499, N = 7; TG + PFF, M = 3.292, SD = 2.156, N = 8) (fig. S11B). In addition, motor performance was also impaired in the TG + PFF group. The beam traversal challenge showed that the TG + PFF group made significantly more (t = 2.216, df = 12, P = 0.047) errors/step on the narrow section of the beam but not on the widest (t = 2.031, df = 12, P = 0.065) portion of the beam (narrow section: control, M = 0.25, SD = 0.08, N = 6; TG + PFF, M = 0.45, SD = 0.21, N = 8; widest section: control, M = 0.21, SD = 0.027, N = 6; TG + PFF, M = 0.32, SD = 0.14, n = 8) (fig. S11C). Other motor assays (OF and rotarod) did not detect significant differences between the two groups (fig. S11, D to F). The OF test did not detect a significant difference between the control and TG + PFF group for movement velocity (t = 0.4397, df = 13, P = 0.6674; control, M = 7.9, SD = 2.03, N = 7; TG + PFF, M = 8.413, SD = 2.427, N = 8), total distance traveled (unpaired Student’s t test; t = 0.4912, df = 13, P = 0.6315; control, M = 6754, SD = 1794, N = 7; TG + PFF, M = 7231, SD = 1944, N = 8), or for the duration of time spent in the center of the chamber (t = 0.3254, df = 13, P = 0.75; control, M = 42.33, SD = 43.73, N = 7; TG + PFF, M = 36.44, SD = 25.18, N = 8) (fig. S11G). The accelerating rotarod test did not detect a significant difference in motor function between the control and TG + PFF groups [repeated-measures ANOVA, F(8, 88) = 1.147, P = 0.341 for interaction between trial and genotype; F(8, 88) = 0.785, P = 0.294 for interaction between trial and gender]. We did not find a significant difference between between-subject effects for genotype (P = 0.585) and gender (P = 0.487). No weight difference was detected at 6 or 10 months of age (fig. S11H). Nonetheless, the behavioral assays that detected a difference (beam traversal and adhesive removal) are well-established tests developed specifically to detect subtle Parkinsonism-related motor deficits (57, 59).

We next asked whether the proteotoxicity of aSyn elicits genotoxic stress in DA neurons. A subset of all three groups received intranigral infusions of PRISM [representative images of the WT + saline (Fig. 6, Q and S) and TG + PFF (Fig. 6, R and T) groups are shown]. Stereological principles were applied to estimate the number and frequency of PRISM labeling within the SNpc. The TG + PFF group exhibited a significantly higher PRISM labeling frequency within the SNpc (one-way ANOVA, F = 8.94, P = 0.032; Fig. 6U). Fisher’s LSD post hoc test revealed that the mean of the TG + PFF group was significantly higher than that of both the WT + saline (P = 0.024) and TG + Mono (P = 0.03) groups. There was no significant difference between the WT + saline and TG + Mono groups. These results establish that the proteotoxicity of aSyn, i.e., the primary constituent of LB inclusions (PK-R aSyn and P-aSyn Ser129, respectively), elicits genotoxic stress in DA neurons.

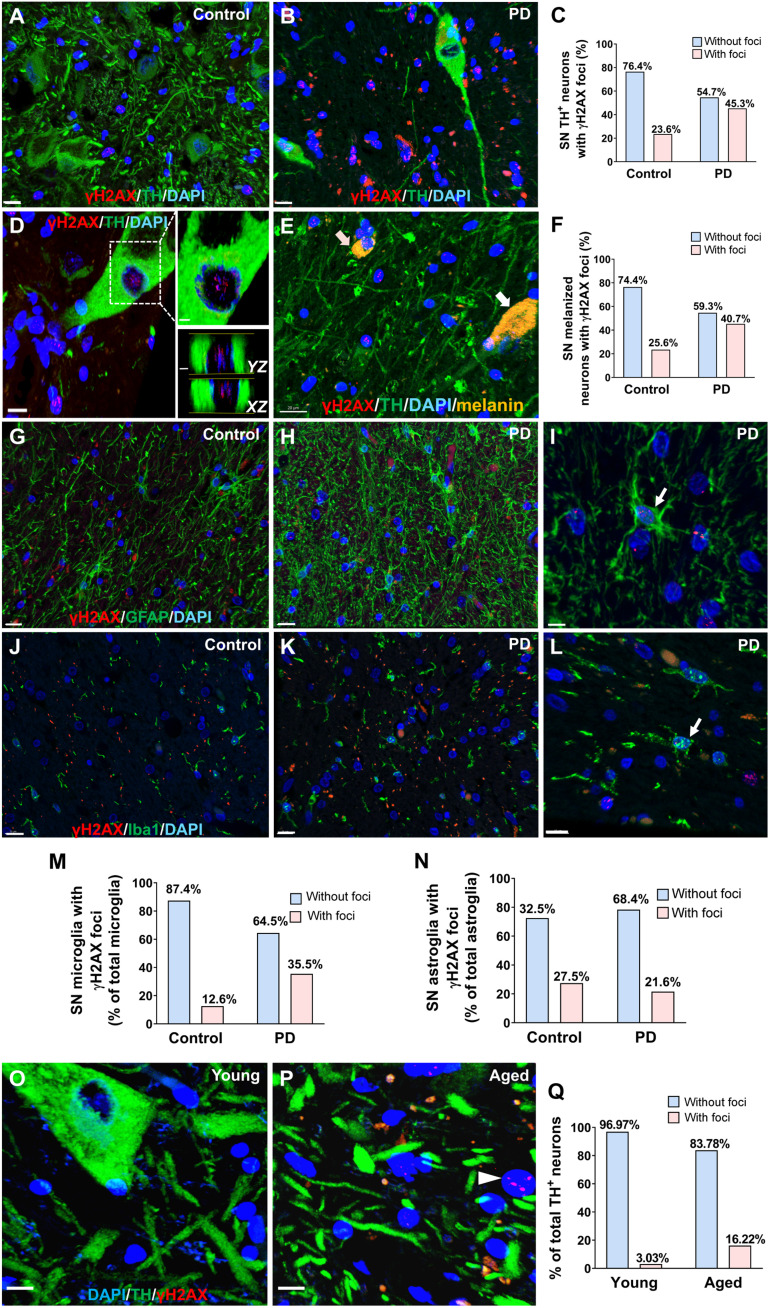

Genotoxic stress in PD patient brains

Last, we asked whether increased neuronal DNA genotoxic stress is relevant in human patients with PD. We assessed the presence of DNA DSBs by performing double IF staining of γH2AX and TH in SN from human postmortem brain samples. Expected PD pathology was first confirmed in the diseased group (fig. S12, A to C). We confirmed the presence of LB inclusions in the PD group (fig. S12A). IF staining for TH revealed not only a significant reduction in the number of nigral TH-immunoreactive DA neurons in PD brains by 50% but also a significant increase in the number of total glial (discerned by nuclear morphology), confirming PD pathology (fig. S12D; independent-sample test, t = 3.80, df = 9, P = 0.0042; fig. S12E; t = 2.324, df = 9, P = 0.0318, n = 6 patients with PD and 5 age-matched unaffected controls; demographic data of subjects shown in table S1). We developed an unbiased semiautomated workflow (fig. S13) for rapidly and accurately quantifying γH2AX foci in neurons and glia in human brain samples. In PD brains, the proportion of SN TH-positive neurons with γH2AX foci was significantly higher than in the age-matched unaffected controls [23.5% in the unaffected control group, which nearly doubled to 45.3% in the PD group, chi-square test, χ2 (1, n = 138) = 7.113, *P = 0.008, 138 TH-positive DA neurons were analyzed from n = 6 patients with PD and n = 5 age- and gender-matched unaffected controls; Fig. 7, A to C].

Fig. 7. Genotoxic stress in PD patient brains.

(A and B) Representative confocal images from postmortem samples after double IF staining for TH and γH2AX. Scale bars, 15 μm. (C) The proportion of TH-immunoreactive cells with distinct nuclear γH2AX foci in patients with PD and the age-matched unaffected controls (chi-square, P = 0.008). (D) A single TH-positive neuron with γH2AX foci. Right: 2D slice along YZ and XZ axis (slice thickness: 0.6 μm) illustrates γH2AX foci in a TH-immunoreactive DA neuron. (E) Representative confocal image of double IF staining for TH and γH2AX in SN. Neuromelanin-containing cells are shown in melanin granules (yellow) with TH-positive (white arrow) or TH-negative (pink arrow) melanized neurons. Scale bar, 20 μm. (F) The percentage of total melanized (TH-positive or TH-negative) neurons with γH2AX foci in the PD group or in the unaffected controls (chi-square, P = 0.033). (G to I) Representative confocal images from postmortem samples after double IF staining for GFAP and γH2AX in age-matched controls and PD brains. Scale bars, 15 μm (G and H) and 5 μm (I). (J to L) Representative images from postmortem samples after double IF staining for Iba1 and γH2AX in age-matched controls and PD brains. Scale bars, 15 and 10 μm (L). (M) The proportion of microglia with distinct nuclear γH2AX foci in patients with PD is significantly higher than in the age-matched controls (chi-square, P < 0.0001). (N) The proportion of astroglia with distinct nuclear yH2AX foci in patients with PD is not significantly different from age-matched controls (chi-square, P > 0.05). (O and P) Representative images from young and aged human postmortem samples after double IF staining for TH and γH2AX. White arrows indicate cells with nuclear γH2AX foci. Scale bars, 10 μm. (Q) The proportion of TH-positive cells with distinct nuclear γH2AX foci was significantly higher in the older age group relative to the younger age group (chi-square, P = 0.016).

It has been reported that the loss of nigral melanized neurons lags behind the loss of dopamine markers in PD brains (60). We thus examined the percentage of cells with γH2AX foci in SN melanin-containing neurons with negative or positive TH immunoreactivity in patients with PD and age-matched unaffected controls. Neuromelanin-containing neurons were discerned by melanin autofluorescence (61) and the typical cytoplasmic morphology of melanin granules (Fig. 7E). We confirmed that the percentage of total melanized (TH-positive or TH-negative) DA neurons with γH2AX foci in the PD group (40.7%) was significantly higher than in the unaffected controls (25.6%) [chi-square test, χ2 (1, n = 176) = 4.5637, P = 0.033, melanized neurons were analyzed from n = 6 patients with PD and n = 5 age- and gender-matched unaffected controls; Fig. 7F]. In the PD group, the percentage of TH-positive melanized neurons with γH2AX foci (45.28%) was comparable to the percentage of TH-negative melanized neurons with γH2AX foci (33.33%) [chi-square test, χ2 (1, n = 86) = 1.2033, P > 0.05; melanized neurons were analyzed from n = 6 patients with PD and n = 5 age- and gender-matched unaffected controls]. Last, the percentage of total melanized DA neurons (TH+ or TH−) that are TH negative is 38.37% in the PD group, which was significantly higher than in the unaffected control group (5.56%) [chi-square test, χ2 (1, n = 167) = 27.9754, P < 0.00001, melanized DA cells were analyzed from n = 6 patients with PD and n = 5 age- and gender-matched unaffected controls]. This suggests a significant loss of phenotypic expression of TH in nigral melanized neurons in PD and is consistent with the notion that the loss of nigral melanized neurons was less than the loss of TH-immunoreactive neurons in patients with PD (60).

To further analyze genotoxic stress in different types of glia, we performed double IF staining of γH2AX and GFAP for astroglia (Fig. 7, G to I) or Iba1 for microglia (Fig. 7, J to L). The percentage of γH2AX foci observed in microglia in the PD group (35.5%) was significantly higher than in the unaffected control group (12.6%) [chi-square test, χ2 (1, n = 873) = 40.3897, P < 0.00001, 873 microglia were analyzed from n = 10 patients with PD and n = 5 age- and gender-matched unaffected controls; Fig. 7M]. The percentage of γH2AX foci observed in astroglia was 27.6% in the unaffected control group and 21.8% in the PD group [chi-square test, χ2 (1, n = 510) = 2.068, P = 0.150, 476 astroglia were analyzed from n = 10 patients with PD and n = 7 age- and gender-matched unaffected controls; Fig. 7N].

Next, to gain insights into age-related changes in genotoxic stress in DA neurons, we compared γH2AX specifically in TH-positive neurons between a young group (24 to 33 years of age, mean = 28.25, n = 4) and a healthy aged group (61 to 74 years of age, mean = 67.33, n = 6) using the same approach described above (Fig. 7, O and P). The proportion of TH-positive DA neurons with distinct nuclear γH2AX foci was significantly higher in the older age group relative to the younger age group [chi-square test, χ2 (1, n = 103) = 5.75, *P = 0.016; Fig. 7Q]. There were no significant differences in postmortem interval between the test groups and no difference in mean age within the PD and age-matched control group (fig. S14, A to J, and table S1). Confocal optical settings were kept consistent and are provided in table S2.

DISCUSSION

We have detailed the design and characterization of the first in vivo genotoxic stress reporter, PRISM, to explore DNA damage and DDR in postmitotic differentiated neurons that do not undergo DNA replication. We demonstrated that the PRISM reporter responds to increased DDR and oxidative stress with high sensitivity, which permits longitudinal studies to track the fate of cells with genotoxic stress, as well as visualization of DNA damage/DDR that might be related to subtle neurodegenerative changes before the neuron’s final demise.

DDR machinery is absent in rAAV viral particles. Therefore, the PRISM detects the errors of DDR pathways in the host cells rather than host genomic mutation per se. Sophisticated surveillance and repair mechanisms have evolved in eukaryotic cells to recognize, signal, and repair DNA damage. In particular, ATM is one of the critical molecules for mediating DDR to safeguard genomic stability. ATM is a phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase–like kinase selectively activated upon DNA damage (62). Upon recruitment to a break in the DNA double helix by the MRN (Mre11/Rad51/Nbs1) complex, ATM autoactivates itself by phosphorylation of Ser1981. Once activated, pATM targets several proteins for phosphorylation, and the resulting alterations in their functions either assist in the DNA repair process itself (Brca1, Nbs1, γH2AX, etc.) or arrest the cell cycle (p53, Chk2, etc.). ATM is activated not only by DNA DSBs but also by oxidative stress (63) and responds to multiple DNA damage repair pathways such as MMR, BER, and nucleotide excision repair pathways (64–66). Intriguingly, in the virus-host interaction, the DDR pathway is used by host cells to eliminate virus invasion and can be considered as an innate antiviral host defense mechanism. On entering the nucleus, rAAV genomes are recognized by cellular DDR proteins, such as MRN and ATM. These DDR proteins are inhibitory of the single-strand to double-strand genome conversion, impeding rAAV dsDNA production or routing the genomes to aberrant processing or nucleolytic degradation, thus limiting transduction. Our extensive validation results support the hypothesis that genotoxic stress (e.g., elicited by exposure to environmental toxicants or alpha-synuclein proteotoxicity) increased and sequestered DDR protein to the host cell genome, alleviating their repression to rAAV genome processing (e.g., dsDNA conversion or stability of intermediate dsDNA). Therefore, PRISM primarily labels neurons with genotoxic stress, defined as persistent DNA damage and overzealous DDR.

Beyond sensing DNA damage in the host cells, we engineered an error-prone microsatellite repeat into the rAAV genome to explore host cell maintenance of DNA stability (DNA damage repair). In cells with the increased single-strand to double-strand rAAV genome conversion elicited by genotoxic agents, only the cells that fail to maintain microsatellite stability can turn on the reporter expression. It has been noted that microsatellite repeats are often sites of breakage or “fragile sites” (67), which are defined as gaps or breaks in human chromosomes. Many fragile sites are known in humans and are associated with trinucleotide repeat expansions or minisatellite expansions. These DNA repeat sequences are hotspots for genome instability, and the subsequent repair is error prone. DNA repair pathways, such as MMR and DDR-mediated DSB repair (43), have been shown to promote repeat instability. While MMR is particularly important in dividing cells, neurons are postmitotic and have a high metabolic rate, making them more sensitive to single-strand breaks or DSBs and oxidative damage, which would be repaired predominantly through the error-prone NHEJ pathway. Both double-strand (68) and single-strand break repair can lead to high frequencies of deletions within repeats (69). It has been shown that ssDNA break-induced contraction of repeats depends on the DDR kinase ATM by single-strand annealing between repeat ends (69).

We recognize that other genome integrity maintenance mechanisms could drive the expression of PRISM. PRISM-labeled neurons are enriched with nuclear and mitochondrial oxidative DNA damage. Oxidative DNA damage can facilitate microsatellite instability (70, 71). Oxidized bases are repaired via BER, which necessitates an abasic site that is cleaved out. Incomplete BER can, therefore, result in ssDNA breaks. The clustering of these ssDNA breaks can lead to NHEJ-mediated mutations via ATM (72). Furthermore, in the nonreplicating neurons, transcriptional mechanisms such as adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate response element–binding protein–binding protein activity, transcription elongation, and/or transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair could contribute to repeat instability (73–75).

With the mononucleotide poly-G (G22) tract inserted between the translation initiation codon and the open reading frame of a Cre recombinase, our sensor not only reports genotoxic stress but also uses conditional genetic reporter systems, resulting in sparse neuronal labeling. This system permits detailed morphologic/pathologic analysis at single-cell resolution. Furthermore, in cells with a floxed allele, the genomic instability reporter can further serve as an actuator for genetic perturbation. Therefore, in neurons/glia with genotoxic stress, the Cre recombinase can be activated and subsequently conditionally overexpress, knock out, or knock down the expression of a gene of interest, thus allowing a seek-and-rescue strategy to further dissect pathogenic mechanisms or serve as a therapeutic intervention.

Our sensitive single-neuron neurodegeneration pathologic analysis revealed, at single-cell resolution, sublethal structural and cellular changes to neurons that may increase neuronal vulnerability and detrimentally affect neuronal function long before their eventual demise (i.e., prodromal degeneration). Thus, this approach enables us to investigate the possible causative links between environment-driven and endogenous pathogenic processes, e.g., alpha-synuclein proteotoxicity and neurodegenerative disease phenotype. Furthermore, the labeled cells could be enriched for sequencing to identify possible deleterious somatic brain mutations, identify the potential therapeutic targets, and serve as a sensitive readout to evaluate the functional consequence of the therapeutic intervention.

One of the defining features of NDDs is the selective degeneration/vulnerability of one or more classes of neurons, such as SN DA neurons in PD, striatal MSNs in HD, motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and hippocampal neurons in AD. However, the molecular mechanism/substrates that underlie such selective vulnerability in NDDs are unknown, particularly as environmental toxicants or proteotoxicity affects the brain ubiquitously. What explanation is there for the selectivity in neuronal killing from a widely affected insult? Before single-neuron genomics, Bates’ group (12) observed DNA instability in postmitotic neurons in HD mouse models and HD patient brains; the most affected region in HD, striatum, is distinguished by an age-dependent high rate of CAG repeat instability. This observation is consistent with our results that PD-associated environmental toxicant exposure can induce genotoxic stress in postmitotic neurons. Unexpectedly, we found that SN DA neurons have a high rate of genotoxic stress (both at baseline and in response to exposure to environmental toxicants). With hundreds of cell types intermingled in the central nervous system, it is also conceivable that neuronal genotoxic stress may elicit different and sometimes opposite pathologic consequences in different neural cell types. Intriguingly, in the PD patient brains, we also found a significantly higher level of genotoxic stress in microglia. This highlights a non–cell-autonomous pathogenic role of dysfunctional glia, possibly via a genotoxic stress–driven replicative senescence mechanism. Further design of a cell type–specific genomic reporter and cell type–specific single-cell genetic manipulation may identify the molecular substrates as therapeutic intervention targets to solve selective vulnerability conundrums for neurodegeneration.

We have shown increased DSBs in neurons labeled by PRISM and in DA neurons in human patients with PD. Various studies have linked DDR and its master regulator ATM to apoptosis, genotoxic stress, and oxidative damage that is associated with aging and neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and ALS (76–78). A recent study analyzed two different synucleinopathy PD mouse models based on either intranigral delivery of rAAV-expressing human alpha-synuclein or intrastriatal injection of human alpha-synuclein PFF. In both cases, a significant increase in DDR (pATM, γH2AX, and 53BP1) in DA neurons was detected, collectively implicating a pathogenic role of overzealous DDR in PD (79).

Genetic and small-molecule ATM inhibitors are neuroprotective in primary striatal neurons, a genetic mouse model, and neurons differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells derived from patients with HD. This work suggested that reducing overactive DDR signaling could ameliorate mutant Huntingtin neurotoxicity (51). The neuroprotective role of attenuating the DDR is unexpected. If DNA damage accumulation is pathogenic in neurodegeneration, then attenuating DDR as a therapeutic strategy logically should enhance disease by decreasing DNA damage repair capability rather than suppressing it. On the basis of the literature and our results, we argue that environment-driven mutations that cause disease occur at very low frequencies. These mutations, on their own, have a relatively small pathogenic impact. Instead, the overzealous activation of DDR is more harmful and is the real culprit that initiates the pathogenic process of neurodegeneration.

Given the looming neurodegenerative epidemic stalking humanity’s aging population, an imminent need for novel neurotherapeutics exists. We have now provided a useful tool to study the pathogenic mechanism of neuronal genotoxic stress in neurodegeneration and to explore therapeutic approaches. PRISM may facilitate the identification of prodromal readouts/biomarkers for neurodegeneration and establish an in vivo high-throughput screening platform to expedite the development of disease-modifying therapies for NDDs that target both genetics and interacting environmental factors.

METHODS

Engineering PRISM (AAV-G22-Cre) vector

The viral vector construct rAAV-hSynapsin-G22-Cre-WPRE-bGHpA was designed and reconstructed as follows: Two oligonucleotides were synthesized and annealed to generate a multiple cloning site to replace the FLEX-EGFP fragment in the expression vector AAV phSyn1(S)-FLEX-EGFP-WPRE (a gift from H. Zeng; Addgene plasmid no. 51504; http://n2t.net/addgene:51504; RRID:Addgene_51504) containing the human synapsin promoter. The Sal I–Hind III fragment of the KOZAK-ATG-G22-Cre that contains the mononucleotide tract (G22), followed by the Cre coding region to create a frameshift mutation, was synthesized and inserted in between the phSyn1 promoter and WPRE-bGHpA.

rAAV production

The constructs were packaged into recombinant AAV-DJ8 or AAV-PHP.eB using capsid plasmid DNA and helper plasmid DNA from Cell Biolabs Inc. The Syn-G22-Cre plasmid was amplified by growing in E. coli, and plasmid DNA was purified using a Maxi-Prep Kit (Qiagen, 12162). The quality of the DNA product was assessed by digestion with restriction enzyme Kpn l and running the yield along with an uncut control on a 1% agarose gel. Purified Syn-G22Cre was packaged with pHelper and capsid construct DJ8 at 1:1:1 ratio in HEK-293 cells using Lipofectamine 3000 reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, L3000015). Cells were grown for 3 days after transfection, and cell lysate was harvested, and the packaged virus was purified using an affinity column method (Bioland, AAV12-00). Cell medium was also collected, and AAV was concentrated using AAVanced Concentration Reagent as per company protocol (System Biosciences, AAV100A-1). Cell lysates were applied to a discontinuous gradient of iodixanol (OptiPrep; Greiner Bio-One, Longwood, FL) 3 days after transfection and centrifuged (350,000g for 1 hour). The AAV was then removed, diluted twofold with lactated Ringer’s solution (Baxter, Deerfield, IL), and then washed and concentrated by Millipore (Billerica, MA) Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter units. The final stocks were sterilized by Millipore Millex-GV syringe filters into low-adhesion tubes (USA Scientific, Ocala, FL). VG was determined by real-time PCR using SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, 1725280) on three replicates of every viral batch produced. The virus was stored in 5-μl aliquots at −80°C.

T7E1 assay

Genomic DNA was extracted with Monarch Nucleic Acid Purification Kits (NEB). Target regions were PCR-amplified with Q5 Hot Start High Fidelity in the EnGen Mutation Detection Kit. PCR products were denatured at 95°C for 5 min and reannealed at a −2°C/s temperature ramp to 85°C, followed by a −0.1°C/s ramp to 25°C. The heterocomplexed PCR product (5 μl) was incubated with 5 U of T7E1 enzyme (NEB) at 37°C for 20 min. Products from mismatch assays were electrophoresed on a 2.5% tris-acetate-EDTA gel. Densitometry analysis was performed with Bio-Rad gel image analysis software. Some of the T7E1-digested products were analyzed for size with the Agilent TapeStation DS1000 assay (Agilent Technologies).

Next-generation sequencing

Six PCR amplicon samples were cleaned up, assessed, and processed for sequencing. Samples were cleaned up using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) using their standard PCR purification protocol. Samples were quantitated with the Qubit dsDNA BR (Broad Range) assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). DNA quality and size were determined with the Agilent TapeStation DS1000 assay (Agilent Technologies). Each amplicon (100 ng) was processed separately; six total libraries were prepared. The libraries were prepared with the Nextera DNA Flex Library Prep Kit and indexed with the Nextera CD Indexes (24 indexes) kit (Illumina). Each sample was tagmented and cleaned up. After 5 cycles of amplification, the second round of clean-up was performed. The libraries were quantitated with the Qubit dsDNA BR assay and quantified with the Agilent TapeStation DS1000 assay. Molarities of the libraries were determined, and libraries were normalized to 4 nM and pooled together. The pool was denatured and diluted to approximately 10 pM. A 5% library of 10 pM denatured PhiX was spiked in as an internal control. Paired-end 2 × 151 bp sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq.

NGS analysis