Abstract

Background:

Few existing evidence-based parent interventions (EBPIs) for prevention and treatment of child and youth mental health disorders are implemented in low-middle-income countries. This study aimed to translate and confirm the factor structure of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS-15) survey in Brazilian Portuguese with the goal of examining providers’ perspective about EBPIs.

Methods:

We translated and back translated the EBPAS-15 from English to Brazilian Portuguese. Participants were recruited via snowball sampling and data were collected using an online survey from July of 2018 through January of 2020. A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to determine if the scale retained its original structure. Open-ended questions about providers’ perspectives of their own clinical practice were coded using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). Analyses included data from 362 clinicians (318 women, 41 men) from 20 of the 27 states of Brazil. Participants on average were 26.7 years old, held specialist degrees in the field of psychology, actively worked as therapists, and practiced in private clinics.

Results:

The translation of the EBPAS to Brazilian Portuguese retained the same four-factor structure as the English version except for dropping one item from the Divergence domain. When asked about the challenges in their practices, providers generally referred to parents as clients with little skills to discipline their children and lacking knowledge about child development.

Discussion:

The Brazilian version of the EBPAS-15 is promising, but future research should consider using quantitative data alongside qualitative information to better understand providers’ attitudes about evidence-based interventions to inform implementation efforts.

Trial registration.

N/A.

Keywords: Evidence-based parent interventions, Provider attitude, EBPAS-15, Implementation

1. Background

About 10–20% of children and adolescents worldwide have mental health problems (Kieling et al., 2011). Whereas there are several evidence-based parent interventions (EBPIs) for the prevention and treatment of child and youth mental health disorders (Buchanan-Pascall et al., 2018; Medlow et al., 2016; Mingebach et al., 2018; Weber et al., 2019), reviews of interventions in low-middle-income countries indicate that there are few rigorous studies (Kieling et al., 2011; Pedersen et al., 2019), with the majority having small sample sizes (Kieling et al., 2011). There were no national-level surveys in Brazil prior to the SARS COVID-19 pandemic, but surveys conducted in major cities suggested an average prevalence of 25% for mental health problems among adults (Andrade et al., 2012) and between 13.1% and 30% among children from representative states within the country (Paula et al., 2015; Sá et al., 2018). National level data collected from adults in Brazil during the pandemic have shown a higher prevalence of depression (61%), anxiety (44%), and stress (50%), especially among younger adults (between 18 and 24 years old; Campos et al., 2020; Ribeiro et al., 2021). Similar increases in mental health problems and anxiety have been found among children after the start of the pandemic (Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2020), with caregivers reporting struggles with parenting practices during the SARS COVID-19 outbreak in Brazil (Oliveira et al., 2021). With the assumption that parenting practices mediate children’s behaviors (Forehand et al., 2013; Forgatch & DeGarmo, 2002; Forgatch & Patterson, 2010; Sanders et al., 2000; Webster-Stratton, 2020), there is an urgent need to promote effective parenting practices (EBPIs) among caregivers to prevent increases in mental health issues among Brazilian children.

Referrals and access to EBPIs in Brazil, however, are problematic. Even when diagnosed with an emotional disorder, the majority of children (about 80%) are not referred to services (Fatori et al., 2019). With the exception of a small number of randomized controlled trials (Murray et al., 2019), there is very little knowledge about the efficacy or effectiveness of EBPIs in Brazil. In fact, researchers have voiced their concerns regarding the low availability of evidence-based interventions (EBIs) to address common mental health conditions, a fact that is particularly worrisome considering the recent spike in the prevalence of mental health issues during the pandemic (Mari et al., 2021), showing a clear quality gap in the context of health services research in Brazil.

Multiple factors determine the implementation of evidence-based interventions in usual care, including providers’ attitudes towards EBIs to inform their development, adaptation, implementation, and sustainment (Cabassa & Baumann, 2013). In Brazil, the training of mental health professionals such as psychologists is purposefully designed to be broad and traditionally does not emphasize any specific area of training (de Oliveira et al., 2017), with the idea that individuals will then seek further training on their own (Paula et al., 2012). One consequence of such broad training is a lack of exposure to EBIs. Additionally, while the country has a universal healthcare system, the private care sector has a strong presence (Amaral et al., 2018; Malta et al., 2017). The contextual factors of broad training and main delivery of mental healthcare being in private practice poses potential barriers to implementing EBIs in Brazil.

The field of implementation science aims to implement EBIs into usual care (Eccles & Mittman, 2006) by examining the contextual factors (e.g., the effect of providers, organization, policies) on the implementation of EBIs. Examining the context and implementation process is key to distinguishing the effect of the intervention versus the implementation, and thoughtful theory-based implementation approaches are critical for the successful implementation and sustainment of EBIs (Damschroder & Hagedorn, 2011). Context, such as the structure and the network of communication between providers and their leaders, and the values and beliefs of providers, are some of the key variables in many implementation frameworks (Aarons, 2004; Atkins et al., 2017; Damschroder & Hagedorn, 2011; Meyers et al., 2012; Michie, 2005). One of the factors that predict successful implementation of EBIs is related to provider attitudes. Several studies have examined provider attitudes in systems of care settings (Melas et al., 2012), such as community health centers (Gioia, 2007), hospitals (Aarons, 2004; Melas et al., 2012), substance use disorder treatments in indigenous communities (Moullin et al., 2019), genomic medicine (Overby et al., 2014), and residential care (Ringle et al., 2019), but little is known about providers’ attitudes towards evidence-based interventions in private practice.

Research is needed to identify factors that may impact the adoption of EBPI interventions among providers to inform implementation efforts in Brazil. Before adapting EBPIs for the Brazilian context, we aimed to examine the attitudes of mental health professionals, including those in private practice, towards EBPIs in general. In this study, we used the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS-15; Aarons, 2004) to examine Brazilian providers’ attitudes towards EBPIs. The EBPAS-15 asks about professionals’ feelings about using and being trained in evidence-based interventions, defined as types of therapy, treatment, or interventions with specific guidelines or components that are outlined in a manual or that are to be followed in a determined way. The original scale contains 15 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale, organized into four dimensions. The Appeal subscale examines the extent to which the provider would adopt an evidence-based intervention if it was intuitively appealing, could be used correctly, or if it were being used by peers. The Requirements subscale examines the extent to which the providers would adopt an evidence-based intervention if it was required by their supervisor, agency, or state. The Openness subscale examines the extent to which the provider is open to trying new interventions and whether s/he would be willing to try manualized interventions. The Divergence subscale examines the extent to which the provider perceives evidence-based interventions as not clinically useful and less important than their clinical experience. The EBPAS-15 total score represents the providers’ overall attitudes towards the adoption of evidence-based interventions. The EBPAS-15 has been translated to examine providers attitudes in multiple countries and languages, including Sweden (Roaldsen & Halvarsson, 2019), Netherlands (van Sonsbeek et al., 2015), Norway (Egeland et al., 2016), Greece (Melas et al., 2012), Iceland (Gudjonsdottir et al., 2017), and South Africa (Padmanabhanunni & Sui, 2017).

In addition to examining attitudes among providers towards EBPIs, we aimed to assess their perspectives on their own clinical practice. Because of the general training that mental health providers receive in Brazil, we were unsure about the degree to which providers were using theories in their clinical practice, and what their perceived barriers towards implementing EBPIs in their practice were. If we are to implement EBPIs in Brazil, we need to be informed by theory of behavior change to design and evaluate our future implementation process (Cane et al., 2012; French et al., 2012). As such, we asked which theoretical perspectives informed the clinicians’ practice. We also asked the types of challenges that providers have in their practice. Their open-ended responses for the challenges question were coded using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF; Michie, 2005). The TDF has been used to inform the implementation of several interventions (French et al., 2012; Phillips et al., 2015), and has 12 domains in its original framework measuring practitioner clinical behaviors and behavior change: knowledge; skills; social/professional role and identity; beliefs about capabilities; beliefs about consequences; motivation and goals; memory, attention and decision processes; environmental context and resources; social influences; emotion; behavioral regulation; and nature of behaviors.

As part of a line of research in adapting and implementing an EBPI in Brazil, the goals of this study were to translate and confirm the factor structure of the EBPAS-15 in Brazilian Portuguese, examine providers’ attitudes towards EBPIs, and identify the theoretical perspectives that inform their clinical practice.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedures

The survey was translated from English to Brazilian Portuguese by ACM, and then back-translated from Brazilian Portuguese to English by AB, following the World Health Organization guidelines for translation of assessments (World Health Organization, n.d.). Discrepancies were resolved in bi-weekly calls. Once the translation was done, ACM and AL conducted cognitive interviews with peers from Brazil to examine the readability of EBPAS-15 items. The survey was administered to participants using Qualtrics, an online survey tool. Participants were recruited via snowball sampling. We sent emails to groups of providers from our own networks (e.g., REDETAC - https://en.redetac.org/), listservs from psychological institutes and graduate courses (eg., Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Pós Graduação em Psicologia, ANPEEP - https://www.anpepp.org.br/). Up to three emails were sent to our networks. Informal contacts were also made through these organizations using WhatsApp groups. This study was approved by the Brazilian Ethics Committee (CAAE: 49965215.6.0000.5553, Report: 1.399.856, date: February 01, 2016) and the Washington University in St. Louis Ethics Committee (IRB #201705105).

2.2. Sample

A total of 615 clinicians participated in the survey across two versions distributed during recruitment. The first was distributed between July 2018 and March 2019 with 314 clinicians starting the survey, yielding 144 (45.9%) complete responses on the EBPAS-15. Modifications were made to the initial survey to attempt to improve the rate of respondents that completed the EBPAS-15 (i.e., moved the EBPAS scale to the start of the survey). The second version of the survey was then distributed between April 2019 and February 2020, which yielded an additional 301 respondents, with 143 (47.5%) individuals completing the EBPAS-15. For the analyses, we included an additional 75 participants who were missing information on four or fewer variables to reach the recommended sample size (n = 360; described further in analytic plan section).

As shown in Table 1, the final sample consisted of 362 clinicians from 20 out of the 26 states (26 states and Distrito Federal) of Brazil, with most of the participants being from Distrito Federal (42%), followed by São Paulo (16.9%), and Rio de Janeiro (10.5%). Participants were about 27 years old on average. The sample was predominately female, and participants held specialist degrees in the field of psychology, actively worked as providers, and practiced in private clinics. The most common level of work experience among respondents was one to three years and 11 months. Participants served a variety of populations, including children, adolescents, adults, couples, families, and groups. See Table 1 for additional information regarding sample demographics.

Table 1.

Sample descriptives (n = 362).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age M (SD) | 26.7 (9.9) |

| Sex | |

| Women | 318 (87.8%) |

| Men | 41 (11.3%) |

| Training | |

| Psychology | 348 (96.1%) |

| Medicine | 3 (0.8%) |

| Other | 10 (2.8%) |

| Years since graduation | |

| 0 to 1 year and 11 months | 55 (15.2%) |

| 2 years to 3 years and 11 months | 65 (18%) |

| 4 years to 7 years and 11 months | 53 (14.6%) |

| 8 years to 14 years and 11 months | 95 (26.2%) |

| 15 years to 29 years and 11 months | 76 (21%) |

| 30 years or more | 17 (4.7%) |

| Highest level of training | |

| High school | 73 (20.7%) |

| Specialist | 167 (46.1%) |

| Masters | 69 (19.1%) |

| Doctorate | 35 (9.7%) |

| Post-doctorate | 14 (3.9%) |

| Work as a therapist | 333 (92%) |

| Hours a week worked as therapist | |

| 1–4 | 52 (14.4%) |

| 5–8 | 56 (15.5%) |

| 9–15 | 67 (18.5%) |

| 15–25 | 69 (19.1%) |

| 26+ | 96 (26.5%) |

| Setting | |

| Private clinic | 257 (71%) |

| Outpatient clinic | 25 (6.9%) |

| Other | 69 (19.1%) |

| Population | |

| Children | 214 (59.1%) |

| Adolescents | 250 (69.1%) |

| Adults | 282 (77.9%) |

| Couple | 91 (25.1%) |

| Family | 175 (48.3%) |

| Group | 38 (10.5%) |

| Years of experience | |

| 1 year to 3 years and 11 months | 143 (39.5%) |

| 4 years to 7 years and 11 months | 63 (17.4%) |

| 8 years to 15 years and 11 months | 82 (22.7%) |

| 16 years to 29 years and 11 months | 45 (12.4%) |

| 30 years or more | 13 (3.6%) |

2.3. Measures

Attitudes towards evidence-based practice.

The EBPAS-15 is a 15-item scale assessing provider attitudes towards adopting new or different types of therapies or interventions (Aarons, 2004). This scale assesses four areas associated with the adoption of evidence-based practice: appeal (four items), requirements (three items), openness (four items), divergence (four items). Responses to scale items range from 0 to 4: (0) not at all, (1) to a slight extent, (2) to moderate extent, (3) to a great extent, (4) to a very great extent. Research in the United States suggests that internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the overall scale was good (α = 0.76) and ranged from poor to good for subscales (appeal = 0.80; requirements = 0.91; openness = 0.84; divergence = 0.66; Aarons et al., 2010).

Open-ended questions.

Providers were also asked about the theoretical orientation that guides their clinical practice, what type of complaints they see most often at their clinics, and whether they would be willing to be trained in an EBPI. Specifically, we asked providers which theory informed their practice. We also asked the following questions: “We have heard from some of our colleagues who work in primary care that some parents seem to report having difficulties with their children’s behavior. In other words, parents have reported issues with compliance or that children refuse to take their medicine. What has been your experience with this?”, “Based on your experience, which children would have more behavioral difficulties? For example, children with asthma, obesity, older or younger children?”, “If we were to develop a parenting intervention for the families that you see, how do you think this intervention should be?”, “Which barriers or challenges should we foresee to implement such interventions?, “Do you have any additional suggestions regarding evidence-based parenting practices?”, “Would you have any interest in implementing an evidence-based parenting practice?”. See Appendix 1 for interview questions in Portuguese.

2.4. Analytic plan

Statistical analyses examining the EBPAS-15 questionnaire were performed using R version 3.5.2 (R Core Team, 2018), with the lavaan (Rosseel, 2012), tidyverse (Wickham et al., 2019), psych (Revelle, 2019), mice (Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2010), and furniture (Barrett & Brignone, 2017) packages. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) using the Diagonally Weighted Least Square estimator to determine if the EBPAS-15 retained its original structure after translation and administration to a Brazilian audience. The four-factor structure estimates 36 parameters for the CFA, meaning the suggested minimum sample is 360 respondents. Within the current sample, 287 (80% of the required sample) participants provided complete responses on EBPAS-15 items. We included an additional 75 participants who were missing responses on four or fewer variables to reach the recommended sample size. Chi-square test of independence suggest that observed EBPAS-15 items were significantly (p < .05) related to the pattern of missingness. This pattern of missingness falls under the Missing at Random (MAR) mechanism, which describes situations in which observed responses are significantly related to the patterns of missingness (Enders, 2010). When data are MAR, information from observed responses can be used to estimate missing values (Enders, 2010). Data were imputed using the Random Forest algorithm for the CFA, which provides a method of estimating missing categorical values within the structural equation framework (Shah et al., 2014). A baseline model loading all survey items onto one factor was performed. A four-factor model with items loaded to Requirements, Appeal, Openness, and Divergence subscales was tested against the baseline. One item with a poor factor loading (≤0.30) was then removed for the final model.

The question about which theory informs the providers’ practices was double coded by MJ and ACM, and percentage of agreement between raters was calculated (Tinsley & Weiss, 1975). Most of the open-ended questions were not answered by the participants or were not rich enough to allow for coding. The answers to the question about providers’ experience (“What has been your experience about this?”), however, was coded by AB and MJ using the TDF through deductive coding (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the frequency of responses regarding the relevance and usefulness of the TDF domains. The brevity of the answers provided by respondents precluded richer thematic analysis (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006).

3. Results

EBPAS-15.

Scale descriptive statistics and reliability analysis were conducted only with complete data (n = 287). An EBPAS-15 global score was calculated by summing responses across scales after reverse scoring divergence items. The EBPAS-15 global score suggests that on average participants had overall neutral attitudes towards adopting new or different types of therapies or interventions (M = 2.44; SD = 0.51). Respondent on average reported neutral evidence-based practice appeal (M = 2.43 SD = 0.69), openness (M = 2.48; SD = 0.69), and requirements (M = 1.97; SD = 0.88). Average EBP divergence attitudes within the current sample were low (M = 0.99; SD = 0.63). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the EBPAS-15 global scale was good (α = 0.82) and subscales ranged from poor to good (required = 0.86; appeal = 0.74; openness = 0.77; divergence = 0.60). See Table 2 for summary statistics of EBPAS-15 scales and items.

Table 2.

Summary statistics for completes cases for EBPAS-15 scales and items (n = 287).

| Items | M, ±SD | Skew | Kurtosis | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Requirements | 1.97 ± 0.88 | 0.09 | −0.34 | 0.86 |

| 11) It was required by your supervisor/administrator? | 2.10 ± 0.97 | −0.01 | −0.54 | |

| 12) It was required by your school? | 2.00 ± 0.98 | 0.09 | −0.32 | |

| 13) It was required by your state? | 1.80 ± 1.03 | 0.02 | −0.55 | |

| Appeal | 2.43 ± 0.69 | −0.30 | −0.26 | 0.74 |

| 9) It was intuitively appealing? | 2.48 ± 1.06 | −0.45 | −0.52 | |

| 10) It “it made sense” to you? | 2.97 ± 0.90 | −0.79 | 0.39 | |

| 14) It was being used by colleagues who were happy with it? | 2.23 ± 0.91 | −0.27 | −0.03 | |

| 15) You felt you had enough training to use it correctly? | 2.05 ± 0.81 | −0.60 | 0.13 | |

| Openness | 2.48 ± 0.69 | −0.32 | −0.15 | 0.77 |

| 1) I like to use new types of methods/interventions to help clients. | 2.96 ± 0.91 | −0.43 | −0.65 | |

| 2) I am willing to try new types of methods/interventions even if I have to follow a teaching/training manual. | 2.70 ± 1.02 | −0.40 | −0.48 | |

| 4) I am willing to use new types of methods/interventions developed by researchers. | 2.03 ± 0.80 | −0.46 | −0.34 | |

| 8) I would try new methods/interventions even if it were very different from what I am used to doing. | 2.23 ± 0.99 | 0.13 | −0.63 | |

| Divergence | 0.99 ± 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.60 |

| 3) I know better than academic researchers how to care for clients. | 1.28 ± 0.98 | 0.54 | −0.15 | |

| 5) Research-based teaching methods/interventions are not useful in practice. | 0.49 ± 0.94 | 2.32 | 5.20 | |

| 6) Professional experience is more important than using manualized methods/interventions. | 1.45 ± 1.04 | 0.31 | −0.39 | |

| 7) I would not use manualized methods/interventions. | 0.76 ± 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.06 | |

| Global | 2.44 ± 0.51 | −0.22 | −0.36 | 0.82 |

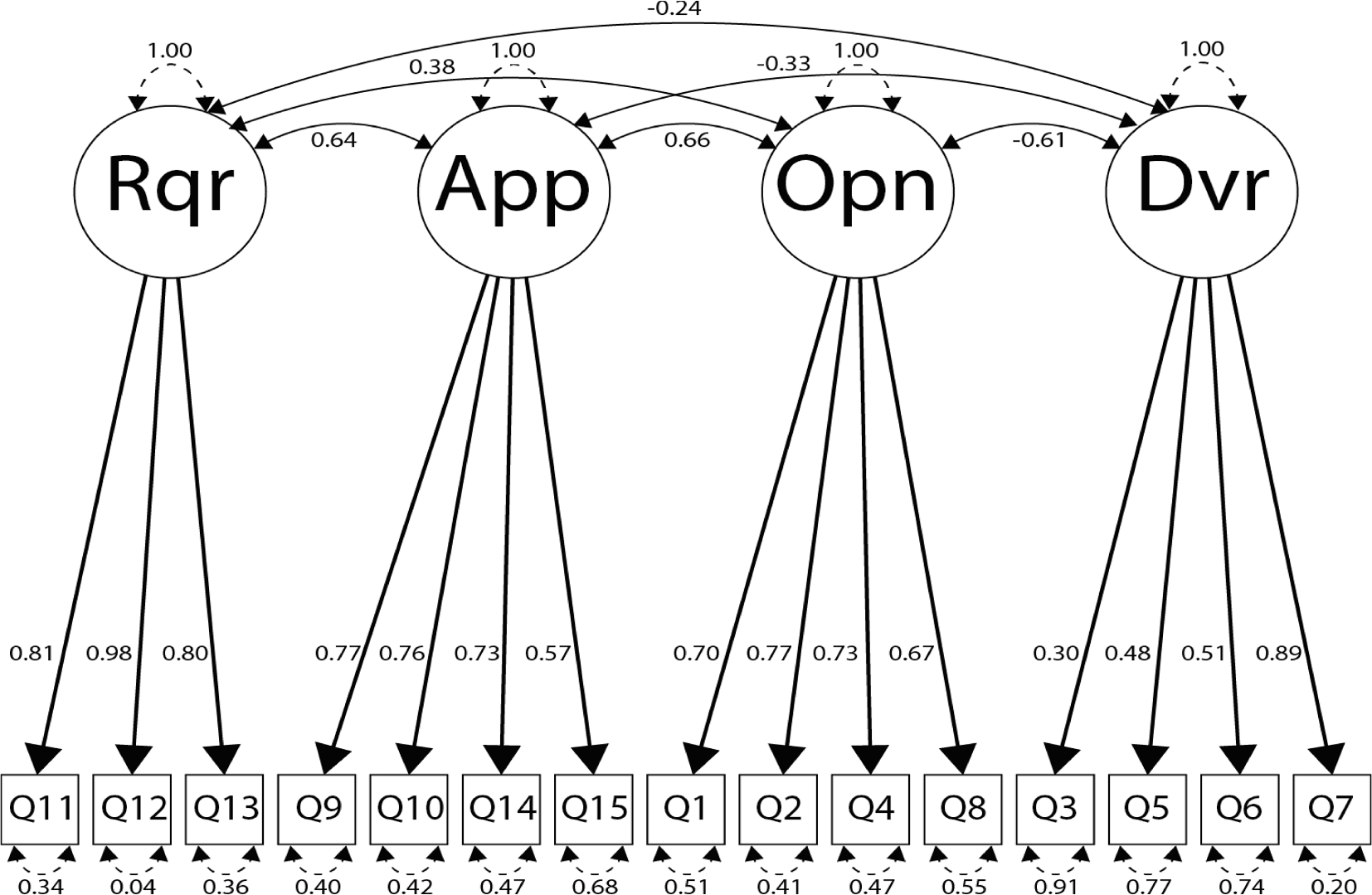

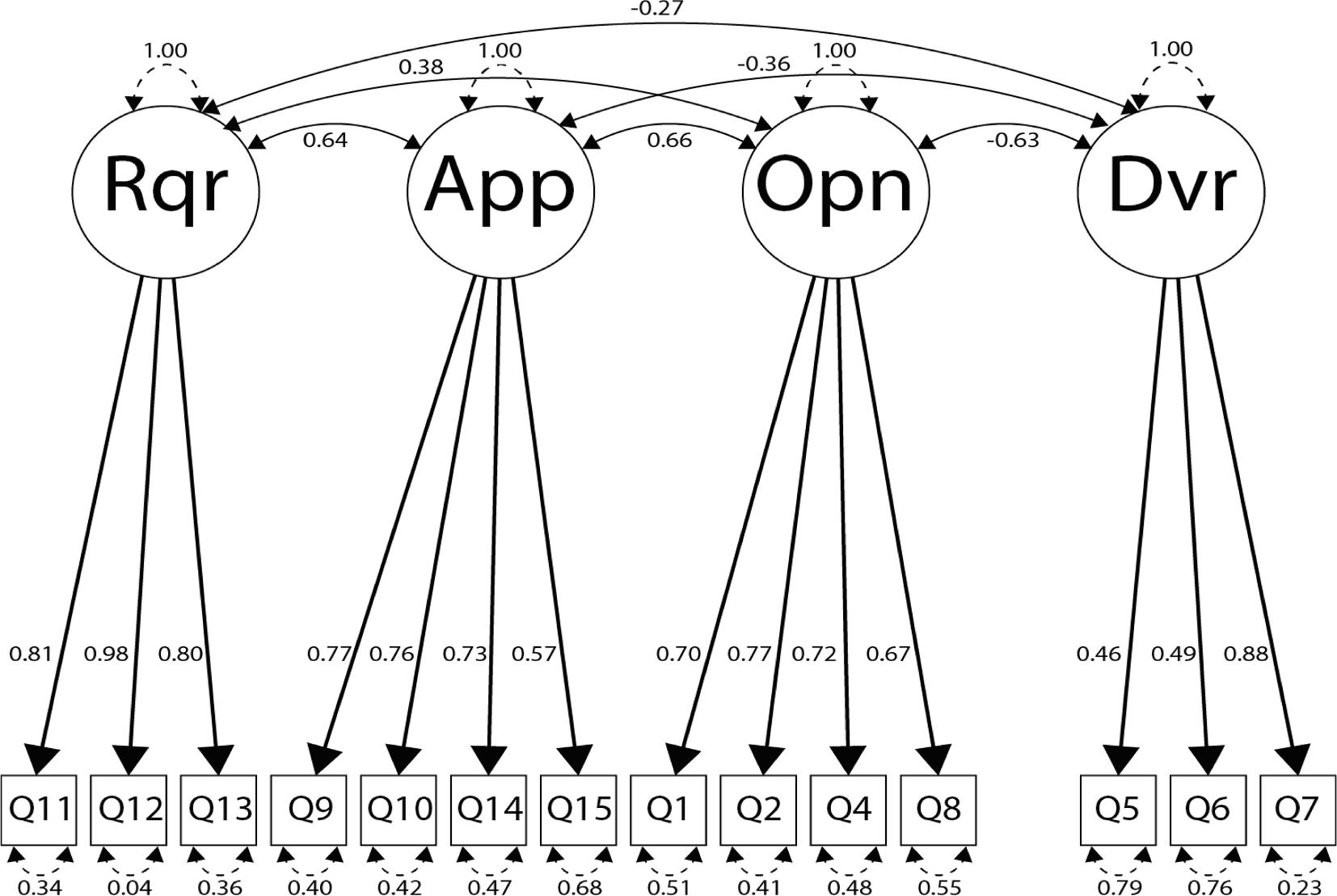

CFA models utilized data which included imputed values (n = 362). The baseline model with all scale items loaded on to one factor had poor fit across multiple indices (Table 3). The four-factor 15-item model had a significantly better fit across all indices, X2(ChisqDif[6] = 164, p < .001), which suggest that Brazilian EBPAS-15 may be best represented by subscales rather than an overall score. (See Fig. 1 for the EBPAS four factor 15-item CFA model.) The decision was then made to drop one item (“I know better than academic researchers how to care for clients”) from the divergence subscale due to a weak factor loading (0.30). This item was also the most common missing value (n = 283; 86.3%) among 328 participants with at least one missing variable in the overall sample (n = 615), providing further evidence that the item may not have been relevant within the current sample. A four-factor 14-item scale was then examined and demonstrated improved fit across all indices except RMSEA, which tends to fit better with a greater number of indicators. Internal consistency for the three-item divergence subscale was 0.55. See Fig. 2 for the final EBPAS four-factor 14-item CFA model.

Table 3.

Fit statistics for baseline and four factor models (n = 362).

| X2 | df | X2/df | RMSEA [90% CI] | SRMR | CFI | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| One factor 15-items | 1104.52 | 90 | 12.27 | 0.177 [0.167–0.186] * | 0.140 | 0.898 | 0.881 |

| Four factor 15-items | 266.04 | 84 | 3.17 | 0.077 [0.067–0.088] * | 0.069 | 0.982 | 0.977 |

| Four factor 14-items | 232.46 | 71 | 3.27 | 0.079 [0.068–0.091] * | 0.068 | 0.984 | 0.979 |

Note: p-value < 0.001*

Fig. 1.

Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale 4 factor 15 item model (n = 362).

Fig. 2.

Final Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale 4 factor 14 item model (n = 362).

Open-ended questions.

We asked the participants “Qual nomenclatura expressa melhor sua orientação teórico-prática?” [“Which theoretical orientation defines your clinical practice?”]. Table 4 shows the frequency and percentage of the theories and practices reported by providers; only 206 participants answered this question. AC and MJ coded these data, with 89.3% agreement. Disagreements were resolved over a conference call. The data showed that 22.3% of providers mentioned that they were informed by Psychodynamic Theories (e.g., Psychoanalysis), 21.8% reported that they were informed by Behavior Analysis Theories, 16.9% by Cognitive Behavior Therapy, and 14.1% by Systemic Family Theory. Other theories that informed the practice of Brazilian providers included Humanist Theories, and Social Therapies, with providers also mentioning being informed or practicing Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing.

Table 4.

Theories that inform providers’ practices.

| Theories | N | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Psychodynamic Theories (e.g., Psychoanalysis) | 46 | 22.3 |

| Behavior Analysis (e.g., ABA, TAC) | 45 | 21.8 |

| Cognitive Behavior Therapy | 35 | 16.9 |

| Systemic Family Theory | 29 | 14.1 |

| Humanist Theories (e.g.,Gestalt) | 16 | 7.7 |

| Social Therapies (e.g., Psychodrama) | 11 | 5.3 |

| Others (e.g., Organizational Theory) | 11 | 5.3 |

| Contextual Therapies (e.g., DBT) | 4 | 1.9 |

| Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing | 4 | 1.9 |

| Human Development | 2 | 0.9 |

| Body Therapies (e.g., Bioenergetic Analysis) | 2 | 0.9 |

| Health Therapy | 1 | 0.48 |

| Total | 206 | |

Participants were also asked to share what challenges they see or experience with parents. Only 147 participants answered this question. AB and MJ coded these responses using the TDF domains, with a 72% of agreement. Disagreements were resolved in one meeting with both coders. Table 5 shows the frequency and percentage of each domain. Below we share some of the key quotes from each domain.

Table 5.

Frequency of the TDF Constructs.

| TDF Constructs | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Skills | 100 | 43.7 |

| Social/professional role and identity | 15 | 6.5 |

| Knowledge | 11 | 4.8 |

| Environmental context and resources | 7 | 3 |

| Social influences | 5 | 2.2 |

| Emotion | 4 | 1.7 |

| Goals | 1 | 0.4 |

| Optimism | 1 | 0.4 |

| N/A | 85 | 37.1 |

| Total | 229 | |

Skills had the highest frequency of all TDF domains. The skills referred to by the providers were about the parents, not about themselves as providers. For example, the difficulty parents had in establishing discipline was a major theme:

“Pra mim isso é parte do reflexo causado pela falta do não. Quando é apresentado um estímulo que não é agradável, fugir é sempre a primeira opção. Por isso falo sempre, ao dizer não para o filho você o prepara para a vida.” [“For me, this is part of the challenge caused by the absence of ’no’. When it is instructed as a stimuli that it is not pleasant, running away is always the first option. So I always say that by saying no to the son is how you prepare him for life.”]

Providers also described having difficulty communicating with parents: “Casos de dificuldade de comunicação com os pais têm sido bem presentes na minha prática clínica.” [“Difficult cases of communication with parents have been very present in my clinic.”], and some difficulties regarding parents’ skills regarding self-control and autonomy:

“Os pais reclamam constantemente sobre os comportamentos de seus filhos, principalmente em casos de falta de autocontrole e de autonomia.” [“Parents constantly complain about the behavior of their children, especially the absence of self-control and autonomy.”]

Knowledge was mentioned in terms of parents not being aware of developmental milestones:

“Muitas vezes os pais procuram manuais prontos sobre como lidar com os filhos em determinadas situações. Na maioria dos casos nota-se uma falta de conhecimento sobre desenvolvimento infantil, implicando em dúvidas quanto aos processos vivenciados pelas crianças.” [“A lot of times parents look for manuals on how to deal with their children in certain circumstances. In the majority of the cases, we can observe an absence of knowledge about the development of children, and consequent doubts related to the experiences of the children.”]

Regarding social and professional roles and identities, some providers recognized the challenges related to the context in parenting practices:

“Há um distanciamento na relação pais e filhos, por diversos motivos: carga excessiva de trabalho dos pais, abuso do uso da tecnologia nas famílias, falta de concepção de grupos nas família, diferenças grandes em referenciais (modelos de crenças). Tudo isso tem gerado falta de diálogo e uma tendência ao individualismo (quase egoísmo) e uma certa arrogância” [“There is a distance in the relationship between parents and children due to several reasons: excessive workload from the parents, overuse of technology, absence of the concept of family, large differences in references (religious beliefs). All of this yield an absence of dialog and a tendency for individualism (almost egocentrism) and a certain arrogance.”]

Finally, 220 providers answered whether they would be willing to be trained by an EBPI. Of these, 185 (84%) answered “yes,” 25 (11%) answered “no,” and 10 (5%) said “maybe.” Of the reasons for “no” and “maybe,” providers mentioned worries about the cost of the intervention and that they do not believe in evidence-based interventions because they prefer to consider the subjectivity of each family during their work.

4. Discussion

This study contributes to the literature in two areas. One, it provides an understanding of Brazilian providers’ attitudes towards EBPIs. Second, it does so with a sample of providers in private practice, which is innovative in the field of implementation science. Providers’ attitudes towards EBPIs were examined through the translation of the EBPAS-15 to Brazilian Portuguese (Aarons, 2004). Our version of the survey retains the same four-factor structure as the English version with good internal consistency across appeal, requirements, and openness subscales. The divergence subscale, however, had poor internal consistency within the current sample. We dropped one item from the divergence scale due to a factor loading below 0.30 (“I know better than academic researchers how to care for clients.”). Given the large number of respondents who chose not to answer this question (283 out of 615 total responses) and the relatively low average score (1.28 on a scale of 0–4), it may be that respondents who did feel that they knew better than academic researchers were uncomfortable with answering this question. Even with adjusting the scale, the internal consistency of the remaining three items remained poor (0.55). A similar challenge was reported regarding the Swedish (Roaldsen & Halvarsson, 2019), and Dutch versions (van Sonsbeek et al., 2015), and in replications of the original EBPAS-15 in the United States (Shapiro et al., 2012). The Norwegian version (Egeland et al., 2016), however, did not have issues with the divergence scale and rather had different loadings for the question regarding whether the state required providers to implement evidence-based interventions.

Our findings regarding internal consistency and factor loadings in the EBPAS-15 divergence subscale provide information regarding needed adaptations to the scale for use among Brazilian clinicians. Measurement is still an area that is evolving in the field of implementation science as we develop and test psychometrically valid instruments for different constructs that predict implementation success (Rabin et al., 2016). An important consideration in the field of the implementation science is whether measurement tools have been examined with members of the cultural context that is being studied. This is vital as measures that are not tested or adapted within the cultural context of interest may yield errors in measurement equivalence (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2018; Vaughn-Coaxum et al., 2016). Considering that the divergence subscale is problematic across samples in different contexts, care should be taken when interpreting results regarding divergence providers’ attitudes towards evidence-based practices. As the divergence subscale asks participants to report potential disagreement with evidence-based practices, responses may be affected by social desirability from respondents and thus further research may be needed to develop methods that better capture this construct (Krumpal, 2013). As researchers learn more about the factors that predict adoption of evidence-based practices globally, it will be important to understand the context and how it may affect response rates in validated surveys. In other words, surveys are an important component in our studies, but they are just a tool and should be part of a process involving qualitative data and, most importantly, the involvement of the country’s stakeholders as team members to guide and champion the implementation efforts.

We contextualized the information drawn from the EBPAS-15 survey with open-ended questions based on the TDF to examine barriers and facilitators of behavioral change. Providers reported determinants of EBPI implementation associated with most of the TDF domains. When asked about challenges in their clinical practice, most providers described parents as having limited skills to discipline their children, or that they lacked knowledge regarding child development. Additionally, providers tended to be pessimistic about the ability of their clients to have positive relationships with their children. This “parental determinism” seems to be present in other countries and is embedded in a larger conversation about how providers conceptualize the role of parents in promoting the well-being of their children (Furedi, 2004;Lee et al., 2014). While parents were identified as the primary contributor to their child’s wellbeing, aspects of the environmental context emerged as being relevant to the relationships between parents and their children. Challenges such as parents’ workload and differences in culture were considered barriers to positive parent-child relationships.

These qualitative findings are important in the context of EBPIs because they underscore the need for training providers with a multisystemic approach, including highlighting their own role as an agent of change who can influence parents’ behaviors (Forgatch & Domenech Rodríguez, 2016; Shapiro et al., 2012). The awareness of the relationship between providers and parents, and the providers’ attitudes towards EBPIs are perhaps even more crucial when related to providers in the private sector, as represented within our sample. The field of implementation science now needs to examine how to increase adoption of evidence-based practices among decentralized providers who are isolated in their private practices and are not connected to any specific organizations.

It is worth noting that respondents did not have strong attitudes for most subscales, neither for nor against evidence-based practices on the EBPAS-15 questionnaire. Notwithstanding the absence of strong responses for evidence-based practices on the EBPAS-15, when asked whether they would be willing to be trained in an EBPI as an open-ended question, 84% of 220 providers answered “yes.” As we move forward, we should capitalize on such enthusiasm for further training and think carefully about options for scaling EBPIs and maintaining fidelity within this context (Shapiro et al., 2010).

4.1. Limitations

While we have learned a lot about Brazilian providers and their attitudes towards EBPIs, this study has limitations. This study’s limitations include the potential for response bias, and brief answers in the open-ended questions prevented richer understanding of the context. The current study recruited participants using an online snowball approach. While this method reduced structural challenges to recruitment (e.g., decentralized private practice), it may have contributed to greater propensity for variable missingness and may have not captured a representative sample of Brazilian providers. Furthermore, as participants were largely concentrated in specific city centers, our findings may not generalize to providers in rural areas. Further research is needed to verify our findings within a more representative sample with lower levels of variable missingness. While these limitations should be considered when using the EBPAS-15 in Brazil, the absence of more rigorously evaluated measures in Brazilian Portuguese makes this a valuable tool for informing implementation efforts within this country. This measure presents a step towards documenting evidence-based practice attitudes in Brazil and informs the next phase of training providers in EBPI. That is, providing further information about attitudes towards EBPIs and its benefits for parents and children in Brazil may be an important step for stakeholder engagement during our pre-implementation work.

5. Conclusion

The data we collected indicated that the four-factor 14-item translation of the EBPAS-15 had a similar factor structure and internal validity to that of providers in other countries. We recommend caution with its application given the novelty of evidence-based practices within this context. Despite its limitations, the EBPAS-15 provides a valuable tool that may aid implementation efforts within Brazil and ultimately improve the quality of behavioral health services that families receive. Providers within the current sample reported that they struggled to provide effective parenting interventions and were largely interested in being trained in EBPIs to meet this need. Future research could utilize the EBPAS-15 alongside a broader array of predictors of successful EBPI implementation within usual care to identify opportunities and challenges in scaling these interventions in Brazil.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our participants for answering the survey and Dr. Gregory Aarons for his comments on early drafts of this manuscript.

Funding.

This study was funded by the Center for Dissemination and Implementation (CDI) at the Institute of Public Health, Washington University in St. Louis. AB is also funded by UL1TR002345, 5U24HL136790, P50 CA-244431, 3D43TW011541-01S1, 1U24HL154426-01, 5U01HL133994-05 and 3R01HD091218. BJC is also funded by 5UL1TR00234504 and 5P50CA24443102.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate. All participants were consented online to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Brazilian Ethics Committee (CAAE: 49965215.6.0000.5553, Report number: 1.399.856, date: February 01, 2016) and the Washington University in St. Louis Ethics Committee (IRB #201705105)

Consent for publication. As part of the consent process, participants consented publishing aggregate and anonymous data.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106421.

Availability of data and materials.

Data is available upon reasonable request.

References

- Aarons GA (2004). Mental Health Provider Attitudes Toward Adoption of Evidence-Based Practice: The Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research, 6(2), 61–74. 10.1023/B:MHSR.0000024351.12294.65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Glisson C, Hoagwood K, Kelleher K, Landsverk J, & Cafri G (2010). Psychometric Properties and United States National Norms of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Psychological Assessment, 22(2). 10.1037/a0019188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral CE, Onocko-Campos R, de Oliveira PRS, Pereira MB, Ricci ÉC, Pequeno ML, Emerich B, dos Santos RC, & Thornicroft G (2018). Systematic review of pathways to mental health care in Brazil: Narrative synthesis of quantitative and qualitative studies. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 12. 10.1186/s13033-018-0237-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade LH, Wang Y-P, Andreoni S, Silveira CM, Alexandrino-Silva C, Siu ER, Nishimura R, Anthony JC, Gattaz WF, Kessler RC, & Viana MC (2012). Mental Disorders in Megacities: Findings from the São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey, Brazil. Plos ONE, 7(2), Article e31879. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O’Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, Foy R, Duncan EM, Colquhoun H, Grimshaw JM, Lawton R, & Michie S (2017). A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Science, 12(1), 77. 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett TS, & Brignone E (2017). Furniture for Quantitative Scientists. The R Journal, 9(2), 142. 10.32614/RJ-2017-037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan-Pascall S, Gray KM, Gordon M, & Melvin GA (2018). Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Parent Group Interventions for Primary School Children Aged 4–12 Years with Externalizing and/or Internalizing Problems. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49(2), 244–267. 10.1007/s10578-017-0745-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S, & Groothuis-Oudshoorn K (2010). MICE: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software; University of California, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa L, & Baumann A (2013). A two-way street: Bridging implementation science and cultural adaptations of mental health treatments | Implementation Science | Full Text. Implementation Science: IS, 8, 90. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos JADB, Martins BG, Campos LA, Marôco J, Saadiq RA, & Ruano R (2020). Early Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil: A National Survey. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(9), 2976. 10.3390/jcm9092976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane J, O’Connor D, & Michie S (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7(1), 37. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, & Hagedorn HJ (2011). A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 194–205. 10.1037/a0022284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodríguez MM, Baumann AA, Vázquez AL, Amador Buenabad NG, Franceschi Rivera N, Ortiz-Pons N, & Parra-Cardona JR (2018). Scaling out evidence-based interventions outside the US mainland: Social justice or Trojan horse? Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 6(4), 329–344. 10.1037/lat0000121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles MP, & Mittman BS (2006). Welcome to Implementation Science. Implementation Science, 1(1), 1. 10.1186/1748-5908-1-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egeland KM, Ruud T, Ogden T, Lindstrøm JC, & Heiervang KS (2016). Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS): To measure implementation readiness. Health Research Policy and Systems, 14(1), 47. 10.1186/s12961-016-0114-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, & Kyngäs H (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guildford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fatori D, Salum GA, Rohde LA, Pan PM, Bressan R, Evans-Lacko S, Polanczyk G, Miguel EC, & Graeff-Martins AS (2019). Use of Mental Health Services by Children With Mental Disorders in Two Major Cities in Brazil. Psychiatric Services, 70(4), 337–341. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, & Muir-Cochrane E (2006). Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. 10.1177/160940690600500107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Jones DJ, & Parent J (2013). Behavioral parenting interventions for child disruptive behaviors and anxiety: What’s different and what’s the same. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 133–145. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, & DeGarmo D (2002). Extending and testing the social interaction learning model with divorce samples. In Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention (pp. 235–256). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/10468-012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2016). Interrupting coercion: The iterative loops among theory, science, and practice. In The Oxford handbook of coercive relationship dynamics (pp. 194–214). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, & Patterson GR (2010). Parent Management Training—Oregon Model: An intervention for antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. In Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (2nd ed., pp. 159–177). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- French SD, Green SE, O’Connor DA, McKenzie JE, Francis JJ, Michie S, Buchbinder R, Schattner P, Spike N, & Grimshaw JM (2012). Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: A systematic approach using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implementation Science, 7(1), 38. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furedi F (2004). Therapy Culture: Cultivating vulnerability in an uncertain age. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia D (2007). Using an Organizational Change Model to Qualitatively Understand Practitioner Adoption of Evidence-Based Practice in Community Mental Health. Best Practices in Mental Health, 3(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gudjonsdottir B, Arnadottir HA, Gudmundsson HS, Juliusdottir S, & Arnadottir SA (2017). Attitudes Toward Adoption of Evidence-Based Practice Among Physical Therapists and Social Workers: A Lesson for Interprofessional Continuing Education. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 37(1), 37–45. 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, Rohde LA, Srinath S, Ulkuer N, & Rahman A (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1515–1525. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumpal I (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047. 10.1007/s11135-011-9640-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Bristow J, Faircloth C, & Macvarish J (2014). Parenting Culture Studies Basingstoke and New York. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Malta DC, Stopa SR, Pereira CA, Szwarcwald CL, Oliveira M, & dos Reis AC (2017). Private Health Care Coverage in the Brazilian population, according to the 2013 Brazilian National Health Survey. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 22, 179–190. 10.1590/1413-81232017221.16782015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari JJ, Gadelha A, Kieling C, Ferri CP, Kapczinski F, Nardi AE, Almeida-Filho N, Sanchez ZM, & Salum GA (2021). Translating science into policy: Mental health challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 43(6), 638–649. 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medlow S, Klineberg E, Jarrett C, & Steinbeck K (2016). A systematic review of community-based parenting interventions for adolescents with challenging behaviours. Journal of Adolescence, 52, 60–71. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melas CD, Zampetakis LA, Dimopoulou A, & Moustakis V (2012). Evaluating the properties of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS) in health care. - PsycNET. Psychological Assessment, 24, 867–876. 10.1037/a0027445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers DC, Durlak JA, & Wandersman A (2012). The Quality Implementation Framework: A Synthesis of Critical Steps in the Implementation Process. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(3–4), 462–480. 10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S (2005). Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: A consensus approach. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 14(1), 26–33. 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingebach T, Kamp-Becker I, Christiansen H, & Weber L (2018). Meta-metaanalysis on the effectiveness of parent-based interventions for the treatment of child externalizing behavior problems. PLoS ONE, 13(9), Article e0202855. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moullin JC, Moore LA, Novins DK, & Aarons GA (2019). Attitudes Towards Evidence-Based Practice in Substance Use Treatment Programs Serving American Indian Native Communities. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 46 (3), 509–520. 10.1007/s11414-018-9643-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J, Santos IS, Bertoldi AD, Murray L, Arteche A, Tovo-Rodrigues L, Cruz S, Anselmi L, Martins R, Altafim E, Soares TB, Andriotti MG, Gonzalez A, Oliveira I, da Silveira MF, & Cooper P (2019). The effects of two early parenting interventions on child aggression and risk for violence in Brazil (The PIÁ Trial): Protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 20(1), 253. 10.1186/s13063-019-3356-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira IT, Soligo Á, de Oliveira SF, & Angelucci B (2017). Formação em Psicologia no Brasil: Aspectos Históricos e Desafios Contemporâneos. Psicologia Ensino & Formação, 8(1), 3–15. 10.21826/2179-5800201781315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira TDO, Costa DS, Alvim-Soares A, de Paula JJ, Kestelman I, Silva AG, Malloy-Diniz LF, & Miranda DM (2021). Children’s behavioral problems, screen time, and sleep problems’ association with negative and positive parenting strategies during the COVID-19 outbreak in Brazil. Child Abuse & Neglect, 105345. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overby CL, Erwin AL, Abul-Husn NS, Ellis SB, Scott SA, Obeng AO, Kannry JL, Hripcsak G, Bottinger EP, & Gottesman O (2014). Physician Attitudes toward Adopting Genome-Guided Prescribing through Clinical Decision Support. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 4(1), 35–49. 10.3390/jpm4010035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhanunni A, & Sui X-C (2017). Mental healthcare providers’ attitudes towards the adoption of evidence-based practice in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 47(2), 198–208. 10.1177/0081246316673244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paula CS, Coutinho ES, Mari JJ, Rohde LA, Miguel EC, & Bordin IA (2015). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents from four Brazilian regions. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 37(2), 178–179. 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paula CS, Lauridsen-Ribeiro E, Wissow L, Bordin IAS, & Evans-Lacko S (2012). How to improve the mental health care of children and adolescents in Brazil: Actions needed in the public sector. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 34(3), 334–351. 10.1016/j.rbp.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen GA, Smallegange E, Coetzee A, Hartog K, Turner J, Jordans MJD, & Brown FL (2019). A Systematic Review of the Evidence for Family and Parenting Interventions in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Child and Youth Mental Health Outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(8), 2036–2055. 10.1007/s10826-019-01399-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips CJ, Marshall AP, Chaves NJ, Jankelowitz SK, Lin IB, Loy CT, Rees G, Sakzewski L, Thomas S, To T-P, Wilkinson SA, & Michie S (2015). Experiences of using the Theoretical Domains Framework across diverse clinical environments: A qualitative study. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 8, 139–146. 10.2147/JMDH.S78458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin BA, Lewis CC, Norton WE, Neta G, Chambers D, Tobin JN, Brownson RC, & Glasgow RE (2016). Measurement resources for dissemination and implementation research in health. Implementation Science, 11(1), 42. 10.1186/s13012-016-0401-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Otto C, Erhart M, Devine J, & Schlack R (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Quality of Life and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3721508). Social Science Research Network. 10.2139/ssrn.3721508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W (2019). psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological (1.9.12) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych.

- Ribeiro FS, Santos FH, Anunciação L, Barrozo L, Landeira-Fernandez J, & Leist AK (2021). Exploring the Frequency of Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in a Brazilian Sample during the COVID-19 Outbreak. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4847. 10.3390/ijerph18094847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringle JL, James S, Ross JR, & Thompson RW (2019). Measuring youth residential care provider attitudes: A confirmatory factor analysis of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 35(2), 241–247. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roaldsen KS, & Halvarsson A (2019). Reliability of the Swedish version of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale assessing physiotherapist’s attitudes to implementation of evidence-based practice. PLoS ONE, 14, Article e0225467. 10.1371/journal.pone.0225467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sá DGF, Brentani AVM, Grisi SJFE, Miguel EC, & Graeff-Martins AS (2018). Prevalência de problemas de saúde mental na infância na atenção primária. https://lume.ufrgs.br/handle/10183/206729. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Tully LA, & Bor W (2000). The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 624–640. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AD, Bartlett JW, Carpenter J, Nicholas O, & Hemingway H (2014). Comparison of Random Forest and Parametric Imputation Models for Imputing Missing Data Using MICE: A CALIBER Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179 (6), 764–774. 10.1093/aje/kwt312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro CJ, Prinz RJ, & Sanders MR (2010). Population-Based Provider Engagement in Delivery of Evidence-Based Parenting Interventions: Challenges and Solutions. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 31(4), 223–234. 10.1007/s10935-010-0210-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro CJ, Prinz RJ, & Sanders MR (2012). Facilitators and Barriers to Implementation of an Evidence-Based Parenting Intervention to Prevent Child Maltreatment: The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Child Maltreatment, 17(1), 86–95. 10.1177/1077559511424774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley H, & Weiss D (1975). Interrater reliability and agreement of subjective judgments. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 22, 358–376. 10.1037/h0076640 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Sonsbeek MAMS, Hutschemaekers GJM, Veerman JW, Kleinjan M, Aarons GA, & Tiemens BG (2015). Psychometric properties of the Dutch version of the Evidence-Based Practice Attitude Scale (EBPAS). Health Research Policy and Systems, 13(1), 69. 10.1186/s12961-015-0058-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn-Coaxum RA, Mair P, & Weisz JR (2016). Racial/Ethnic Differences in Youth Depression Indicators: An Item Response Theory Analysis of Symptoms Reported by White, Black, Asian, and Latino Youths. Clinical Psychological Science, 4 (2), 239–253. 10.1177/2167702615591768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber L, Kamp-Becker I, Christiansen H, & Mingebach T (2019). Treatment of child externalizing behavior problems: A comprehensive review and meta–meta-analysis on effects of parent-based interventions on parental characteristics. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28(8), 1025–1036. 10.1007/s00787-018-1175-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C (2020). The Incredible Years Parent, Teacher and Child Programs: Foundations and Future. Routledge: In Designing Evidence-Based Public Health and Prevention Programs. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan LD, François R, … Yutani H (2019). Welcome to the Tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. 10.21105/joss.01686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). WHO | Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. WHO; World Health Organization. Retrieved April 5, 2021, from https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.