Abstract

Two seminal observations suggest that the African genome contains genes selected by malaria that protect against systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in individuals chronically exposed to malaria, but in the absence of malaria, are risk factors for SLE. First, Brian Greenwood observed that SLE was rare in Africa and that malaria prevented SLE-like disease in susceptible mice. Second, Africans-Americans, as compared to individuals of European descent, are at higher risk of SLE. Understanding that antibodies play central roles in malaria immunity and SLE, we discuss how autoreactive B cells contribute to malaria immunity but promote SLE pathology in the absence of malaria. Testing this model may provide insights into the regulation of autoreactivity and identify new therapeutic targets for SLE.

Keywords: autoreactivity, B cells, malaria, systemic lupus erythematosus, clonal redemption, anergy

The impact of malaria on the human genome

Malaria is a mosquito-transmitted infectious disease caused by parasites of the Plasmodium species. Endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, P. falciparum is the deadliest species, taking an enormous toll in Africa with nearly ~228 million cases of malaria and an estimated ~602,000 deaths in 2020, primarily among young children and pregnant women [1]. Cerebral malaria (CM), the most deadly form of severe malaria, accounts for a high proportion childhood deaths from malaria in Africa. Therefore, due to the selective pressure imposed by the high mortality of P. falciparum in children and pregnant women, malaria has had an enormous impact on shaping the human genome [2].

P. falciparum emerged in humans in Africa about 100,000 years ago from ancestral parasites that infected gorillas [3]. Over time, the evolutionary interplay between parasites and the human host selected genes conferring resistance to severe malaria [4]. For example, protection against severe malaria by genes expressed in red blood cells (RBCs), such as hemoglobin S (HgbS), is well-established [2]. In Kenyan children [5], HgbS heterozygosity reduces severe life-threatening malaria by 70–90% among those who have not yet acquired full immunity to malaria [6]. However, the benefits of HgbS are not without costs, since HgbS homozygosity results in sickle cell disease. An estimated 300,000 infants with sickle cell disease are born every year in Africa, and the mortality of children under 5 years with sickle cell disease can exceed 50% [7, 8].

Immunity to malaria is gradually acquired in malaria-endemic areas, but only after years of repeated infections with P. falciparum. However, recent studies confirm that acquired immunity protects against febrile disease, but not infection [9]. Antibodies play a critical role in malaria immunity, as does the control of innate inflammatory responses. Thus, with repeated exposures, the immune system becomes programmed to dampen inflammatory responses to P. falciparum, such that immune individuals co-exist with parasitemia but without fever or other classical symptoms [10–12]. It is therefore not surprising that variants in immune genes may have been evolutionarily selected by P. falciparum. For example, variants in CD40L, TLR7, TLR9, IFNα, and IFNAR1 [13–16], have been associated with reduced risk for severe malaria. It is notable that many of these genes are also implicated in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE, see Glossary). Whether such genetic variants protect against severe malaria have pathophysiologic costs to host fitness is not clear.

In people living in sub-Saharan Africa, chronic malaria infections are highly associated with the presence of autoantibodies but not autoimmune disease, underscoring an interesting relationship between autoreactivity and immunity to malaria, and raising the questions: 1) what are the benefits and costs of autoreactivity; and 2) how are these influenced by the African genome and the environment? Here, we examine the relationship between malaria and autoimmunity in Africans and in individuals of African ancestry living in the U.S. to understand the potential advantages of autoimmune susceptibility genes encoded in the African genome, and the mechanisms that regulate autoimmunity in Africans residing in malaria-endemic regions. Answers to these questions may provide a novel perspective on our current understanding of the mechanisms that contribute to the development of both malaria immunity and the pathogenesis of SLE. Because autoantibodies are associated with a variety of inflammatory infectious diseases, notably HIV and COVID-19 [17, 18], our discussion may also provide insights into the role of autoreactive B cells in these infections.

Exploring a hypothesis linking genetic resistance to severe malaria to autoimmune susceptibility

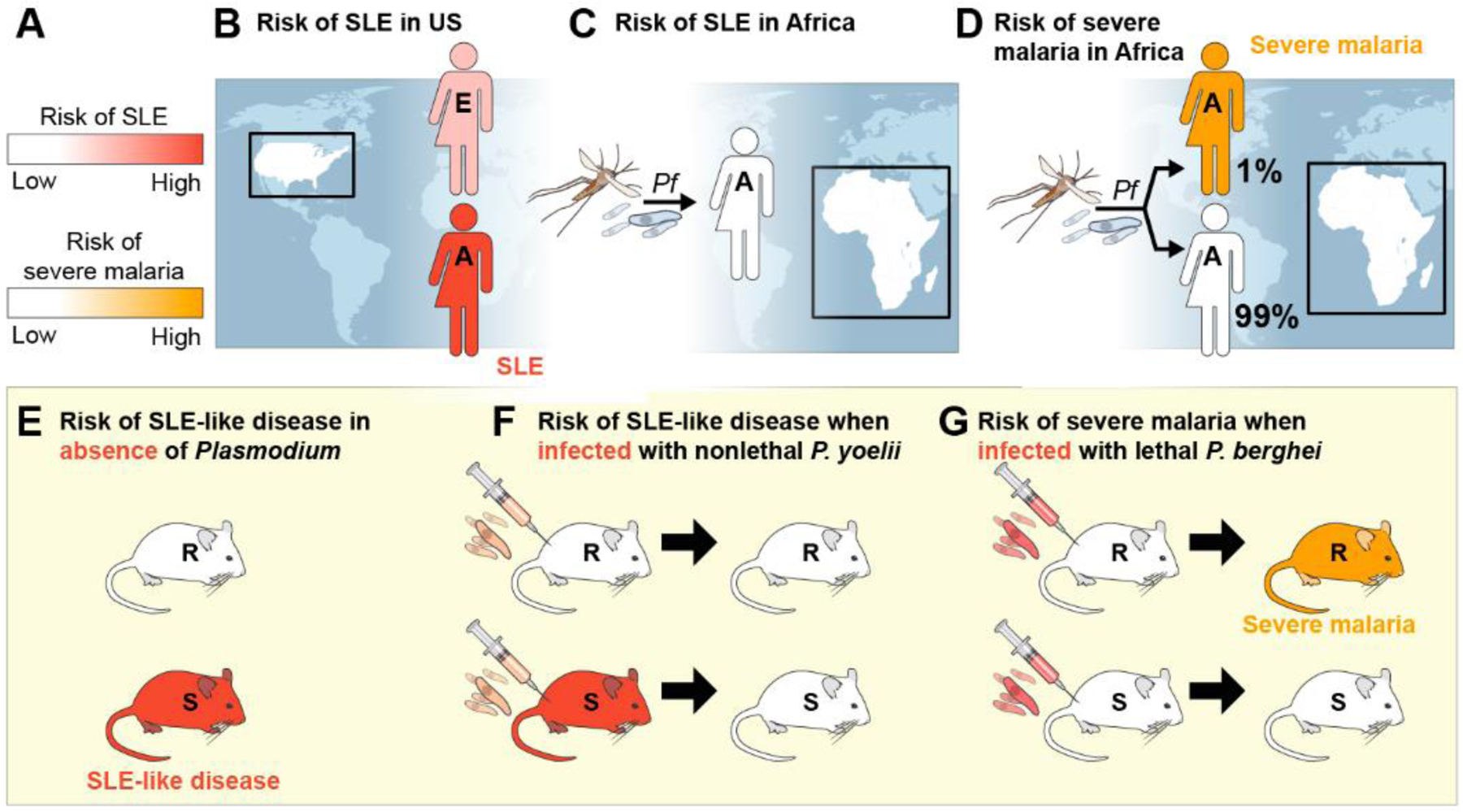

Here we explore a hypothesis that P. falciparum shaped the African genome by selecting genetic variants that confer resistance to severe malaria and death but function as autoimmune susceptibility genes in the absence of malaria. We imagine that resistance to severe malaria depends heavily on alterations in genes that control immune functions including inflammation. The relative risks for SLE (in dark pink) or severe malaria (in orange) resulting from genetic composition and environmental factors are depicted as color-coded scales (Figure 1A). We then illustrate the risk of SLE in individuals of African (A) and European (E) genetic ancestry living in the U.S., where P. falciparum exposure is essentially non-existent (Figure 1B), as compared to Africans living in sub-Saharan Africa, where malaria is endemic (Figure 1C). We also depict the risk of severe malaria in Africans (Figure 1D). In this review, we excluded data obtained from vaccinated individuals and malaria in European travelers due to the inherent differences between acute and chronic exposures to malaria, as well as infections with other Plasmodium species including P. vivax. Lastly, we illustrate the experiments in autoimmune-susceptible (S) and -resistant (R) mouse models mimicking key features of human SLE [19], which have established causality, namely that malaria blocks autoimmune disease in autoimmune-susceptible mice and that genetic autoimmune susceptibility blocks the development of severe malaria (Figure 1E–G).

Figure 1. Diagram of the relationships between autoimmune resistance and susceptibility alleles and the outcomes of severe malaria and overt autoimmune disease.

A relative risks for either SLE (in dark pink) or severe malaria (in red) are shown in A. Individuals with low disease risk are shown in white. The clinical outcomes of individuals of European or African ancestry living in the U.S. (B) or Africa (C and D) as a function of the absence (B) or presence (C and D) of P. falciparum (Pf) are illustrated. In panels E-G, the disease outcomes of autoimmune-resistant (R) and autoimmune-susceptible (S) mice that are uninfected (E) or infected with nonlethal (F) or lethal (G) Plasmodium strains are shown. SLE= systemic lupus erythematosus, E= European, A= African, Pb= Plasmodium bergei, Py= Plas

The African genome is a risk factor for SLE in the U.S. (Figure 1B). Individuals of African ancestry who live outside Africa, such as the Caribbean and the U.S., are at higher risk of SLE [20]. For example, the prevalence of SLE among African-Americans is ~3-fold higher than Americans of European descent [21]. Disease severity in SLE in African-Americans is also correlated with increased genetic load of autoimmune-susceptibility variants [22], and genetic ancestry is considered to be a key determinant of poor outcomes in African-Americans with SLE [20]. Although many candidate genes in the African genome have been associated with increased risk of autoimmunity, these have not yet held up to rigorous genetic analysis. Research is ongoing to explore these candidate genes in-depth and to identify new candidates [23].

In Africa, SLE is rare (Figure 1C). In 1968, Brian Greenwood published his observations made in the hospitals of Nigeria that diseases such as SLE were rare. He proposed a link between parasite infections and systemic autoimmunity [24]. As a caveat, Greenwood pointed out that the true prevalence of SLE is highly debated given the impact of evolving medical care and increased recognition of SLE [25], as well as the potential effects of urbanization and climate change on the transmission of Plasmodium, factors that are continuing to evolve [26, 27]. Nonetheless, the observations depicted in Figure 1B and C strongly suggest that the African genome harbors autoimmune susceptibility genes that are somehow masked by environmental factors in Africa, in particular the prevalance of parasitic diseases including malaria.

Genetic risk factors for SLE may protect against severe malaria (Figure 1D). Only a small fraction of African children with acute febrile malaria proceed to severe malaria (~1%), suggesting that the remaining 99% of these children are protected from severe malaria. This observation, and the epidemiological findings shown in Figure 1B and C, support a hypothesis that genes in the African genome which confer risk of autoimmune disease were selected by P. falciparum because they protected young children and pregnant women from severe malaria and death. Although the molecular basis of the susceptibility of young African children to severe malaria is not clearly understood, we speculate that autoimmune susceptibility genes contribute to resistance to CM in the vast majority of children (99%), and that their absence in the small minority (1%) of children contributes to CM. For example, variants of the FcγRIIb gene are enriched in individuals of African ancestry as well as patients with SLE [28, 29]. Expressed by B cells and myeloid cells, FcγRIIb functions as an important inhibitory receptor for B cell receptor (BCR)-mediated B cell activation (reviewed in [30, 31]). FcγRIIbT232, which contains a mutation in the membrane-associated domain at position 232, is unable to stably partition into cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains on the B cell surface, and is unable to inhibit B cell activation [32, 33]. A meta-analysis examining the frequency of FcγRIIbT232 outside of Africa revealed that FcγRIIbT232 is significantly associated with SLE [29], and thus functions as an autoimmune susceptibility gene (Figure 1B). Conversely, in sub-Saharan Africa, where FcγRIIbT/T232 homozygosity is present at 11% and the FcγRIIbT232 allele is present in 29% of individuals [28], FcγRIIbT232 is correlated with protection from severe malaria [29] (Figure 1D).

Taken together, these observations describing the risks of SLE and severe malaria with respect to African ancestry and the prevalence of malaria suggests that genes present in the African genome function as severe malaria resistance genes when operating in a malaria-endemic environment, but function as autoimmune susceptibility genes in the absence of malaria.

An important tool for understanding the molecular mechanisms that underlie the relationship between malaria and SLE are robust mouse models in which genetically susceptible mice develop spontaneous autoimmune disease that closely mimics key features of human SLE (Figure 1E) (reviewed in [19]). It is well-established that SLE in humans and SLE-like disease in susceptible-mice are polygenic diseases, and multiple susceptibility genes have been identified [34, 35]. For example, Brian Greenwood took advantage of NZB × NZW F1 mice that develop SLE-like disease characterized by nephrotic range proteinuria [36, 37] to show that autoimmune-susceptible mice infected with a non-lethal malaria-causing parasite, P. yoelii, were protected from proteinuria and death from glomerulonephritis (Figure 1F) [37]. Subsequently, autoimmune-prone C57BL/6 FcγRIIb−/− mice infected with P. yoelii were protected from the advanced sequelae of glomerulonephritis, and further mechanistic studies suggested that protection involved CCL17-producing dendritic cells and was not conferred by passive transfer of serum antibodies [36]. Thus, these findings provide evidence that malaria is protective against overt clinical autoimmunity in mice expressing autoimmune susceptibility genes, suggesting that malaria in Africans may block overt autoimmunity that is hardwired into the African genome (Figure 1C). Conversely, in the absence of malaria in the U.S., autoimmune susceptibility variants enriched in individuals of African ancestry confer increased risk of autoimmune disease (Figure 1B).

Remarkablly, the converse also appears to be the case, namely that autoimmune-prone mice are protected against severe malaria, notably CM (Figure 1G). For example, when autoimmune-susceptible transgenic TLR7 and FcγRIIb−/− mice were infected with P. berghei ANKA that causes CM in 100% of infected mice, over 60% survived [38], demonstrating that autoimmune susceptibility genes can confer resistance to severe malaria.

Taken together, the associations in humans and causal links established in mouse models provide a foundation for the hypothesis that the African genome is enriched in autoimmune susceptibility genes that confer resistance to severe malaria but lead to autoimmune disease in the absence of malaria. This hypothesis provides a plausible explanation for the high risk of SLE in African-Americans (Figure 1B) and the rarity of autoimmune disease in Africa (Figure 1C). Exploring the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of malaria on autoimmune disease in genetically susceptible individuals provides a unique opportunity to understand the pathophysiology of systemic autoimmunity.

Impact of malaria on shaping the autoreactive B cell repertoire

To understand how malaria impacts the development of clinical autoimmunity in SLE, we need to consider the roles of autoreactive B cells, autoantibodies and immune tolerance in SLE.

Defects in developmental checkpoints that regulate autoreactive B cell tolerance underlie SLE (Box 1). It is estimated that 55–75% of healthy human immature B cells generated in bone marrow are autoreactive [39]. These B cells must be eliminated or silenced by a process termed tolerance, which occurs in two stages: ‘central tolerance’ that occurs in the bone marrow eliminates high-affinity autoreactive B cells, and ‘peripheral tolerance’ that occurs outside the bone marrow and eliminates weakly autoreactive BCRs that escape central tolerance. Failure to restrain autoreactive B cells through central and/or peripheral tolerance underlies autoimmune diseases such as SLE.

Text box 1: B Cell Tolerance.

Defects in developmental checkpoints that regulate autoreactivity underlie SLE. It is estimated that 55–75% of human immature B cells generated in bone marrow are autoreactive [39]. These cells must be eliminated or silenced by a process termed tolerance, which occurs in two stages. ‘Central tolerance’ occurs in developing bone marrow B cells that engage antigen through high-affinity interactions to eliminate high-affinity autoreactive B cells through negative selection or dampen their autoreactivity through BCR editing of light chains or replacement of heavy chain variable gene segments [88]. ‘Peripheral tolerance’ occurs via BCR engagement of autoantigens outside the bone marrow, leading to the elimination of weakly autoreactive BCRs through receptor editing in germinal centers (GCs) or the induction of a hyporesponsive state termed ‘anergy’ [89]. Through mechanisms of tolerance, B cell autoreactivity is reduced from 75% to 20% [39], with the majority of these remaining autoreactive B cells existing in an unresponsive anergic state [70, 90].

In mouse models, it has been demonstrated that mutations or deficiencies in key genes that control B cell responses to antigens impair B cell tolerance and increase the risk of autoimmunity. For example, in mice genetically engineered to produce B cells expressing BCRs specific for the self-antigen double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), autoreactive dsDNA-specific B cells are in fact rare in the periphery due to peripheral tolerance mechanisms that induce the B cell to undergo BCR editing to eliminate autoreactivity [91]. In contrast, autoimmune C57BL/6 FcγRIIb−/− mice genetically engineered to produce dsDNA-specific B cells develop high titers of dsDNA specific antibodies leading to SLE-like disease due to impaired peripheral tolerance [92]. Therefore, the presence of autoimmune susceptibility genes, such as non-functional FcγRIIb, may lead to defects in reducing BCR autoreactivity or allowing plasma cell differentiation, which then lead to SLE. Similarly, individuals of African ancestry who live in the United Kingdom and are homozygous for non-functioning FcγRIIbT232 alleles have higher frequencies of inherently autoreactive B cells than individuals with functional FcγRIIbI232 alleles [93].

Comparisons between individuals of African ancestry living in Africa versus outside of Africa where malaria is absent, have revealed similar levels of elevated autoantibodies, suggesting that B cell autoreactivity is encoded in the African genome. Indeed, as compared to Caucasians and Hispanics, healthy African-Americans in the U.S. have a significantly higher prevalence of autoimmune antinuclear antibodies (ANA) [40], and the prevalence of ANA in African-Americans is increasing [41]. Because the prevalence of SLE is low in Africa, these observations suggest several possibilities, including that autoantibodies alone are not sufficient to trigger autoimmune disease and/or that the autoantibody repertoires are not identical in Africans living in the absence of malaria and Africans living in malaria-endemic Africa. Illustrating this point, the Gullah people of South Carolina are genetically related to their ancestors in Sierra Leone [42], and it is estimated that 90% of the Gullah genome is derived from the African genome [43]. However, the prevalence of SLE among the Gullah population is roughly 1/150–1/200 in contrast to women living in Sierra Leone where SLE is rare, even though the level of autoantibodies is similar in the two populations, ~28–35% [42].

Furthermore, malaria-immune adult Africans commonly have high levels of autoantibodies, providing clear evidence for activation of autoreactive B cells [30, 44, 45] and strongly suggesting that chronic malaria exposures can break B cell tolerance. From a clinical standpoint, the presence of autoantibodies is significant because they may indicate immune dysfunction, including impaired immune tolerance, which typically precedes the onset of clinical autoimmune disease [46]. As discussed above, even though individuals chronically exposed to malaria have high levels of autoantibodies, overt autoimmune disease is rare. ANA are highly prevalent in children and adults in West Africa [47–49], and elevated levels of anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm antibodies, which are correlated with SLE, are common in individuals living in malaria-endemic regions of the world such as Africa [48, 50, 51]. Anti-phospholipid antibodies such as anti-cardiolipin and anti-phosphatidylserine antibodies, which may also be found in some SLE patients [52, 53], are elevated in Africans chronically exposed to malaria [54–56]. Finally, the presence of ANA in individuals born in West Africa wanes over time in areas where malaria transmission is reduced [57], indicating a requirement for chronic malaria exposures to maintain autoreactivity.

Mouse models have provided tools to investigate the molecular basis of such observations in humans. BALB/c mice infected with P. chabaudi transiently produce high levels of IgM and IgG specific for RBC antigens and DNA [58]. Monoclonal anti-DNA antibodies from BALB/c mice infected with P. berghei recognized parasitized red blood cells and the mesangial areas of kidneys [59], suggesting that Plasmodium-specific antibodies may have developed from autoreactive B cells present in the repertoire. In contrast, C57BL/6 mice infected with P. yoelii produce high titers of ANA that are long-lived [36], suggesting that autoantibody persistence may be genetically controlled by the host or parasite strain. Taken together, these data provide evidence that malaria induces autoreactivity, and its persistence is influenced by genetic background and repeated malaria exposures.

Chronic malaria exposure has had a large impact on the human B cell compartment (recently reviewed in [60]) including the expansion of a unique subset of B cells termed atypical B cells (ABCs) [61–63]. ABC numbers correlate with chronic exposures to malaria, and ABCs exhibit unique activation requirements as well as a distinct cell surface phenotype notable for high levels of inhibitory receptors [64, 65]. An important tool to investigate the potential associations between malaria-derived ABCs and autoreactivity in humans is the inherently autoreactive germline-encoded antibody heavy chain variable gene termed VH4-34 [66]. Autoantigens that bind to VH4-34 have been well-characterized, and an anti-idiotypic antibody called 9G4 that identifies autoreactive VH4-34-expressing human B cells has been developed [67, 68]. In healthy individuals, autoreactive B cells exhibit anergy [69, 70], suggesting that 9G4+ cells may be regulated in the periphery when immune tolerance is intact. ABCs from individuals living in a malaria-endemic Mali expand with repeated malaria exposure [68] and VH4-34 B cells are highly enriched in ABC subsets, especially in young children [61]. Interestingly, although VH4-34 B cells increase during acute febrile malaria in young children [61, 71], this response was absent in older individuals that had developed immunity to malaria [71], suggesting that autoreactivity is regulated when immunity to malaria is acquired. Analyses of recombinant antibodies from ABCs from malaria-immune African adults showed that some ABC-derived antibodies recognized P. falciparum antigens [72], while another study demonstrated P. falciparum-specific antibodies utilizing VH4-34 and/or binding autoantigens [73], indicating that they originated from autoreactive B cells. ABCs from individuals with malaria produced autoreactive anti-phosphatidylserine antibodies ex vivo which correlated with severe malarial anemia [74]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the expansion and differentiation of autoreactive ABCs in malaria is driven by P. falciparum antigens. However, further research is needed to clarify how autoreactive ABCs contribute to malaria immunity.

B cells similar to malaria-derived ABCs are expanded in SLE and produce autoantibodies. During periods of active disease, SLE patients also have large expansions of two B cell subpopulations, termed activated naïve (AN) and double-negative 2 (DN2) B cells on the basis of cell surface phenotyping and expression of the transcription factor T-bet [75]. Additionally, comparison of the transcriptomes of ABCs from malaria-exposed individuals and DN2 B cells from SLE patients revealed common drivers of ABCs, such as IFN-γ [61]. Therefore, given the similar phenotype and transcriptomic profiles of these cells, we will refer to AN and DN2 B cells from SLE patients as SLE-derived ABCs for the remainder of this review. Like malaria-derived ABCs, SLE-derived ABCs contain high frequencies of autoreactive VH4-34 B cells [76]. 9G4+ VH4-34 antibodies from SLE patients bind lupus autoantigens and exhibit autoreactive features in their complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3), including positively-charged amino acids and long lengths [68]. Finally, SLE-derived ABCs can migrate to inflamed tissues and secrete anti-dsDNA and anti-Sm autoantibodies [77], supporting the conclusion that SLE-derived ABCs contribute to autoimmune disease pathogenesis.

ABCs in malaria exhibit high antigen affinity thresholds for activation; in contrast, SLE-derived B cells are hyperresponsive to BCR stimulation [78], suggesting that SLE-derived ABCs have abnormal low thresholds for activation. ABCs are abundant in chronic inflammatory states, including malaria and SLE, but their function is not clearly established. BCRs expressed by malaria-derived ABCs demonstrate evidence of somatic hypermutation [61, 65], suggesting that development of ABCs is antigen-driven; however, they possess unusual activation requirements. For example, malaria-derived ABCs respond poorly to soluble antigens, but when they encounter membrane-associated antigens, they readily form synapses in a manner dependent on affinity for antigen [61, 64]. Malaria-derived ABCs also express high levels of inhibitory receptors on their cell surfaces, including FcγRIIb, FcRL4, and FcRL5 [65], that further regulate the activation of ABCs. These findings strongly suggest that malaria-derived ABCs represent an anergic population with tightly regulated and intrinsically programmed affinity thresholds for activation. In contrast, SLE-derived B cells are hyperresponsive [79], suggesting that defects in regulating B cell activation thresholds may underlie the pathogenesis of SLE. The activation thresholds of SLE-derived ABCs, which have pathogenic potential [75], are not well-characterized. Therefore, given our current understanding of the signaling requirements of malaria-derived ABCs, we propose that anergy in SLE-derived ABCs is impaired, leading to lower activation thresholds and allowing tolerance to be broken.

The inflammatory environment in SLE and malaria may be key to determining the fate of ABCs. Even though SLE and malaria share common drivers of inflammation, the inflammation is ultimately restrained in malaria, yet persistent in SLE, leading to autoimmune disease. The inflammatory environments in malaria and SLE may both support the activation of autoreactive B cells, but may do so in different ways. During malaria, Plasmodium DNA is found at significant levels in circulating immune complexes with pro-inflammatory activity [80], similar to immune complexes from SLE patients. Exposed host DNA in neutrophil extracellular traps are produced during uncomplicated and severe malaria induced by P. falciparum and SLE [81], and may be associated with the development of ANA and anti-dsDNA antibodies [48]. Exposed self-DNA, Plasmodium-derived DNA and hemozoin each activate B cells in a TLR9-dependent manner [82, 83]. CD4+ T cells from SLE patients are pro-inflammatory and contribute to autoimmune disease (reviewed in [84]). However, less functional subsets of CD4+ T cells in acute febrile malaria are activated, leading to suboptimal humoral responses [85], and in the subsequent dry season, CD4+ T cells produce anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL-10 [11]. These findings suggest that although malaria- and SLE-driven inflammation share features supporting autoreactive B cell activation, their fate may be influenced by distinct qualities of inflammation, which alter anergic B cell signaling thresholds and their ability to be ‘reawakened’.

Regulation of autoreactivity in autoimmune-susceptible individuals by malaria

Based on the above, we propose that autoimmune-susceptibility genes and malaria may trigger the activation of autoreactive B cells, but the ability of these B cells to participate in clinical autoimmunity is somehow attenuated by the inflammatory microenvironment. If this hypothesis is correct, the following questions arise: what is the advantage of maintaining as autoreactive B cell repertoire in healthy individuals and survival and how is the progression of autoreactive B cells to overt autoimmune disease regulated?

A proposed evolutionary advantage of maintaining an autoreactive B cell repertoire is to ensure a diverse B cell repertoire (reviewed in [60]). Autoreactive B cells are incompletely eliminated by central tolerance and comprise 20% of the naïve B cell repertoire [39], existing in a state of anergy. It may be that autoreactive B cells are maintained to limit gaps in the antibody repertoire that could be exploited by pathogens [60]. In the case of Plasmodium that possesses extensive antigenic diversity [86], it would make sense for the host to generate a B cell repertoire with sufficient diversity to recognize and anticipate future Plasmodium antigens by maintaining a pool of low-affinity autoreactive B cells that can be drawn into the response when needed.

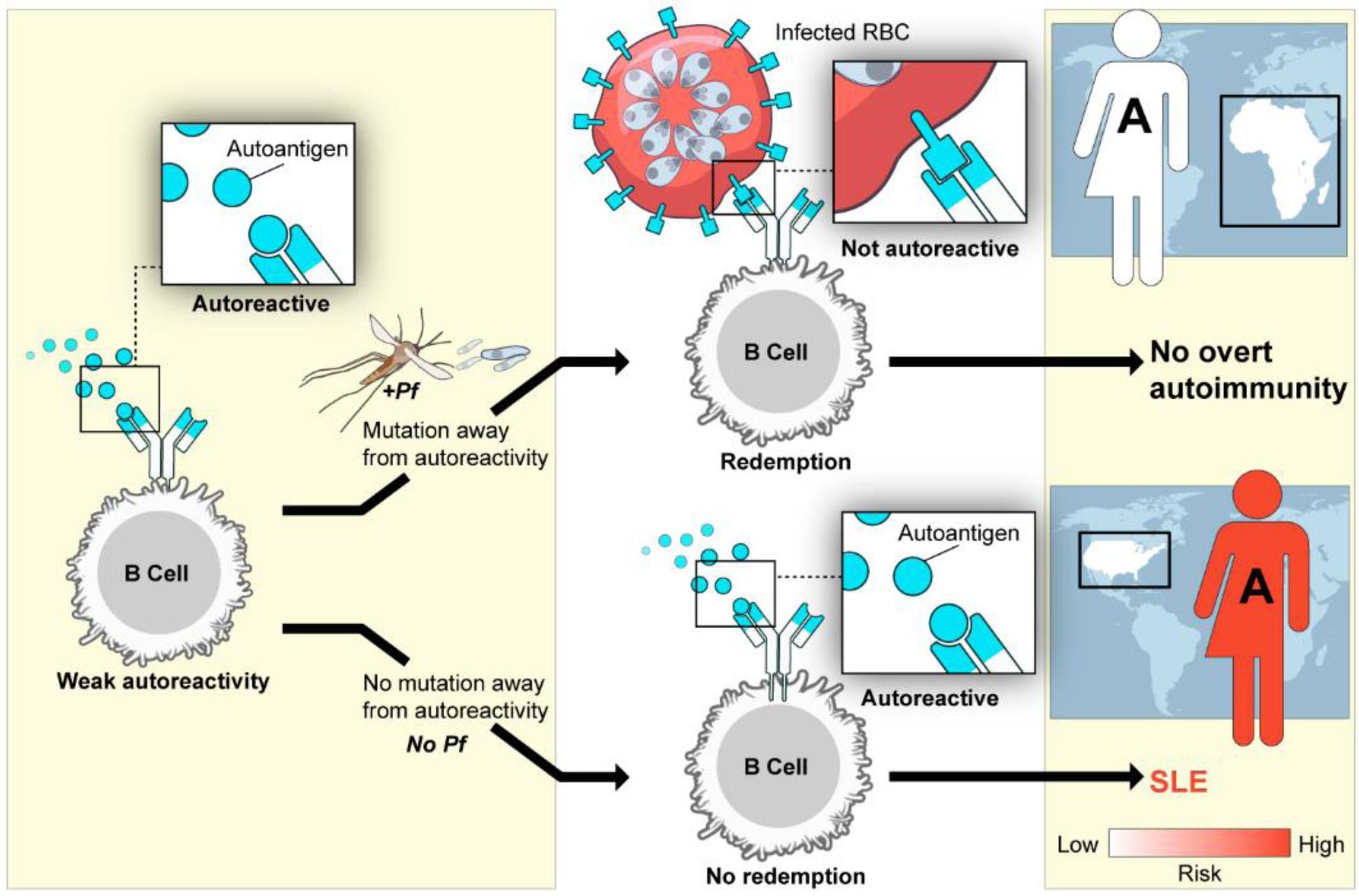

Clonal redemption may allow for the generation of Plasmodium-specific antibodies while regulating autoreactivity (Figure 2). By virtue of their high activation threshold, we speculate that anergic B cells, such as ABCs, are intrinsically programmed to respond to antigen and ‘reawaken’ to initiate clonal redemption, a process in which weakly-autoreactive B cells migrate to germinal centers (GCs) where they undergo somatic hypermutation of their BCRs towards foreign antigen and away from self-reactivity [87]. In individuals of African ancestry who are enriched for autoimmune susceptibility genes that promote repertoire diversity, the presence of Plasmodium infections may provide the stimulus for clonal redemption (Figure 2 top). In this case, low-affinity autoreactive B cells in an individual living in a malaria-endemic region would mutate towards antigens expressed by P. falciparum and reduce self-reactivity. Analysis of heavy chain sequences from unswitched IgMlow VH4-34 ABCs demonstrated that their CDR3 charge was neutral, when compared to IgMhigh unswitched VH4-34 ABCs and naïve B cells, which had net-positive CDR3 charge, suggesting reduced reactivity to negatively-charged autoantigens such as dsDNA [61]. In autoimmune-susceptible individuals living where malaria is not endemic, autoreactive B cells would not encounter the necessary factors to initiate clonal redemption, which would increase their risk of developing SLE (Figure 2 bottom).

Figure 2. A diagram detailing the possible influences of malaria and African ancestry containing autoimmune susceptibility genetic variants on the outcome of clonal redemption.

An individual possessing an African genome-derived autoimmune-susceptibility (S) variant who lives in a malaria endemic region is shown at the top. In this case, the individual’s autoreactive B cells are exposed to Pf-driven inflammation and Pf-derived antigens expressed by infected red blood cells (RBCs), leading to somatic hypermutation and the generation of B cell receptors specific for Pf-derived antigens. Clonal redemption is achieved, and overt clinical autoimmunity is averted. In contrast, an individual of African ancestry (A) who possesses the same African genome-derived autoimmune susceptibility variant but who lives in the U.S., where malaria is absent, is shown in the bottom. In this case, without Pf-driven inflammation or Pf-derived antigens, there is no mutation away from autoreactivity, which increases the risk for developing SLE. Pf= P falciparum.

Concluding remarks

Observations of individuals of African ancestry living in versus outside of Africa suggest a unique relationship between the evolutionary selection of genetic susceptibility to autoimmunity that confer protection against severe malaria and their modulation by malaria. Here we summarized the epidemiologic data and mechanistic studies that together provide evidence for a causal link between malaria and protection from overt systemic autoimmune disease. We propose that qualitative differences in malaria- and SLE-associated inflammation may lead to different outcomes following autoreactive B cell activation, including the regulation of B cell autoreactivity through clonal redemption. Although many of the mechanistic details still need to be addressed and formally tested (see Outstanding Questions), it is clear that understanding the interplay between autoimmune susceptibility alleles and malaria on the B cell repertoire may provide novel insights into the regulation of autoreactivity and pathogenesis of systemic autoimmune diseases such as SLE and uncover new therapeutic targets for autoimmunity.

OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS.

In humans, what specific genetic variants in the African genome contribute to resistance to severe malaria and in the absence of malaria predispose to systemic autoimmune disease?

In Africans, do autoantibodies elicited by chronic malaria exposure contribute to protection against severe malaria?

What features are shared and/or distinct in the autoreactive B cell repertoires arising from chronic malaria exposures and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)?

How might genetic variants present in the African genome that increase the risk of of autoimmune disease influence autoreactive B cell activation, the fates of atypical B cells (ABCs), and the resulting B cell repertoire?

How does malaria-associated inflammation alter the activation of autoreactive B cells?

Would infection with benign Plasmodium parasites be an effective treatment for SLE?

At the mechanistic level, how might the interplay between autoimmune susceptibility genetic variants in the African genome and chronic malaria exposures by P. falciparum lead to clonal redemption of autoreactive B cells?

HIGHLIGHTS.

The pressure that P. falciparum exerted on the African genome due to high lethality among young children and pregnant women may have selected for genetic variants that confer resistance against severe malaria, but in the absence of malaria, function as risk factors for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

SLE is rare in Africans living in malaria-endemic regions. Individuals of African descent living in the U.S. are at high risk of SLE compared to those of European descent.

Malaria rescues genetically susceptible mice from autoimmune disease. Conversely, these same mice are resistant to death from severe malaria.

In malaria, atypical B cells are enriched in autoreactivity, produce Plasmodium-specific antibodies, and exhibit unusual activation requirements.

In malaria, clonal redemption of autoreactive B cells may allow for the generation of Plasmodium-specific antibodies and reduction of autoreactivity.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Pierce lab for critically reading the manuscript, and Ryan Kissinger of Visual and Medical Arts, Research Technologies Branch, National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) for creating the figures. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, NIAID, and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Glossary

- Anergy

a programmed state of hyporesponsiveness in immune cells exerted by tolerance checkpoints that regulate their activation in the periphery. For example, anergic B cells exhibit diminished calcium flux and signaling pathways downstream of BCR engagement

- Anti-idiotypic antibody

an antibody that specifically recognizes a region of the antigen-binding site of another antibody. Anti-idiotype antibodies are used to identify clonal B cells sharing the same BCR antigen-binding site

- Anti-Sm antibodies

anti-nuclear antibodies specific for SLE that recognize the Sm antigen, a ribonucleoprotein

- Atypical B Cells (ABCs)

a newly-identified lineage of B cells of unknown function expanded in chronic inflammatory diseases, including malaria and SLE. ABCs are characterized by expression of the transcription factor T-bet, the absence of the cell surface markers CD21 and CD27, and increased expression of inhibitory receptors such as FcγRIIb. ABCs exhibit unique activation requirements, including hyporesponsiveness to soluble antigens but activation by membrane-associated antigens

- Clonal redemption

a newly-discovered mechanism of B cell regulation in the periphery in which autoreactive B cells are activated and undergo somatic hypermutation of their BCRs away from autoreactivity and towards a foreign antigen

- Complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3)

a region present in all antibody heavy and light chains that is highly variable, thereby contributing to antibody diversity and antigen specificity

- Germinal centers (GCs)

specialized microanatomical structures in secondary lymphoid organs in which B cells undergo antigen-driven somatic hypermutation, isotype switching, and antigen-affinity selection, leading to differentiation towards long-lived plasma cells and memory B cells

- Somatic hypermutation (SHM)

programmed mutation of BCRs in GCs to increase the diversity of BCRs. SHM is followed by antigen-dependent selection to expand antigen-specific cells and remove autoreactive B cells

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

a polygenic systemic autoimmune disease with highly variable clinical symptoms and characterized by the production of autoantibodies, including anti-doublestranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and anti-Sm antibodies

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.WHO (2021) World malaria report 2021.

- 2.Williams TN (2011) How do hemoglobins S and C result in malaria protection? J Infect Dis 204, 1651–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loy DE, et al. (2017) Out of Africa: origins and evolution of the human malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. Int J Parasitol 47, 87–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teo A, et al. (2016) Functional Antibodies and Protection against Blood-stage Malaria. Trends Parasitol 32, 887–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams TN, et al. (2005) Sickle cell trait and the risk of Plasmodium falciparum malaria and other childhood diseases. J Infect Dis 192, 178–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopera-Mesa TM, et al. (2015) Effect of red blood cell variants on childhood malaria in Mali: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Haematol 2, e140–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aygun B and Odame I (2012) A global perspective on sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59, 386–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makani J, et al. (2011) Mortality in sickle cell anemia in Africa: a prospective cohort study in Tanzania. PLoS One 6, e14699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran TM, et al. (2013) An intensive longitudinal cohort study of Malian children and adults reveals no evidence of acquired immunity to Plasmodium falciparum infection. Clin Infect Dis 57, 40–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrade CM, et al. (2020) Increased circulation time of Plasmodium falciparum underlies persistent asymptomatic infection in the dry season. Nat Med 26, 1929–1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portugal S, et al. (2014) Exposure-dependent control of malaria-induced inflammation in children. PLoS Pathog 10, e1004079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran TM, et al. (2016) Transcriptomic evidence for modulation of host inflammatory responses during febrile Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Sci Rep 6, 31291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aucan C, et al. (2003) Interferon-alpha receptor-1 (IFNAR1) variants are associated with protection against cerebral malaria in the Gambia. Genes Immun 4, 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kempaiah P, et al. (2012) Reduced interferon (IFN)-alpha conditioned by IFNA2 (−173) and IFNA8 (−884) haplotypes is associated with enhanced susceptibility to severe malarial anemia and longitudinal all-cause mortality. Hum Genet 131, 1375–1391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabeti P, et al. (2002) CD40L association with protection from severe malaria. Genes Immun 3, 286–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu CJ, et al. (2009) Association study of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the exon 2 region of toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) gene with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus among Chinese. Mol Biol Rep 36, 2245–2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bastard P, et al. (2020) Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19. Science 370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iordache L, et al. (2017) Nonorgan-specific autoantibodies in HIV-infected patients in the HAART era. Medicine (Baltimore) 96, e6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crampton SP, et al. (2014) Linking susceptibility genes and pathogenesis mechanisms using mouse models of systemic lupus erythematosus. Dis Model Mech 7, 1033–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis MJ and Jawad AS (2017) The effect of ethnicity and genetic ancestry on the epidemiology, clinical features and outcome of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford) 56, i67–i77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izmirly PM, et al. (2021) Prevalence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in the United States: Estimates From a Meta-Analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Lupus Registries. Arthritis Rheumatol 73, 991–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langefeld CD, et al. (2017) Transancestral mapping and genetic load in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Commun 8, 16021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudhury A, et al. (2020) High-depth African genomes inform human migration and health. Nature 586, 741–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenwood BM (1968) Autoimmune disease and parasitic infections in Nigerians. Lancet 2, 380–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Symmons DP (1995) Frequency of lupus in people of African origin. Lupus 4, 176–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mordecai EA, et al. (2020) Climate change could shift disease burden from malaria to arboviruses in Africa. Lancet Planet Health 4, e416–e423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tatem AJ, et al. (2013) Urbanization and the global malaria recession. Malar J 12, 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clatworthy MR, et al. (2007) Systemic lupus erythematosus-associated defects in the inhibitory receptor FcgammaRIIb reduce susceptibility to malaria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 7169–7174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willcocks LC, et al. (2010) A defunctioning polymorphism in FCGR2B is associated with protection against malaria but susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 7881–7885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amiah MA, et al. (2020) Polymorphisms in Fc Gamma Receptors and Susceptibility to Malaria in an Endemic Population. Front Immunol 11, 561142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verbeek JS, et al. (2019) The Complex Association of FcgammaRIIb With Autoimmune Susceptibility. Front Immunol 10, 2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Floto RA, et al. (2005) Loss of function of a lupus-associated FcgammaRIIb polymorphism through exclusion from lipid rafts. Nat Med 11, 1056–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kono H, et al. (2005) FcgammaRIIB Ile232Thr transmembrane polymorphism associated with human systemic lupus erythematosus decreases affinity to lipid rafts and attenuates inhibitory effects on B cell receptor signaling. Hum Mol Genet 14, 2881–2892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.International Consortium for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, G., et al. (2008) Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat Genet 40, 204–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanchez E, et al. (2011) Identification of novel genetic susceptibility loci in African American lupus patients in a candidate gene association study. Arthritis Rheum 63, 3493–3501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amo L, et al. (2021) CCL17-producing cDC2s are essential in end-stage lupus nephritis and averted by a parasitic infection. J Clin Invest 131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenwood BM, et al. (1970) Suppression of autoimmune disease in NZB and (NZB × NZW) F1 hybrid mice by infection with malaria. Nature 226, 266–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waisberg M, et al. (2011) Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus protects against cerebral malaria in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 1122–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wardemann H, et al. (2003) Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science 301, 1374–1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satoh M, et al. (2012) Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of antinuclear antibodies in the United States. Arthritis Rheum 64, 2319–2327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dinse GE, et al. (2020) Increasing Prevalence of Antinuclear Antibodies in the United States. Arthritis Rheumatol 72, 1026–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilkeson G, et al. (2011) The United States to Africa lupus prevalence gradient revisited. Lupus 20, 1095–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmerman KD, et al. (2021) Genetic landscape of Gullah African Americans. Am J Phys Anthropol 175, 905–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan J, et al. (2018) A public antibody lineage that potently inhibits malaria infection through dual binding to the circumsporozoite protein. Nat Med 24, 401–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Triller G, et al. (2017) Natural Parasite Exposure Induces Protective Human Anti-Malarial Antibodies. Immunity 47, 1197–1209 e1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arbuckle MR, et al. (2003) Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 349, 1526–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adu D, et al. (1982) Anti-ssDNA and antinuclear antibodies in human malaria. Clin Exp Immunol 49, 310–316 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker VS, et al. (2008) Cytokine-associated neutrophil extracellular traps and antinuclear antibodies in Plasmodium falciparum infected children under six years of age. Malar J 7, 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katz I, et al. (2020) Seroprevalences of autoantibodies and anti-infectious antibodies among Ghana’s healthy population. Sci Rep 10, 2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boonpucknavig S and Ekapanyakul G (1984) Autoantibodies in sera of Thai patients with Plasmodium falciparum infection. Clin Exp Immunol 58, 77–82 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rivera-Correa J, et al. (2020) Atypical memory B-cells and autoantibodies correlate with anemia during Plasmodium vivax complicated infections. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14, e0008466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sahin M, et al. (2007) Clinical manifestations and antiphosphatidylserine antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: is there an association? Clin Rheumatol 26, 154–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taraborelli M, et al. (2016) The contribution of antiphospholipid antibodies to organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 25, 1365–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Facer CA and Agiostratidou G (1994) High levels of anti-phospholipid antibodies in uncomplicated and severe Plasmodium falciparum and in P. vivax malaria. Clin Exp Immunol 95, 304–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jakobsen PH, et al. (1993) Anti-phospholipid antibodies in patients with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Immunology 79, 653–657 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rivera-Correa J, et al. (2019) Atypical memory B-cells are associated with Plasmodium falciparum anemia through anti-phosphatidylserine antibodies. Elife 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cainelli F, et al. (2004) Antinuclear antibodies are common in an infectious environment but do not predict systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 63, 1707–1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ternynck T, et al. (1991) Induction of high levels of IgG autoantibodies in mice infected with Plasmodium chabaudi. Int Immunol 3, 29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lloyd CM, et al. (1994) Characterization and pathological significance of monoclonal DNA-binding antibodies from mice with experimental malaria infection. Infect Immun 62, 1982–1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burnett DL, et al. (2019) Clonal redemption and clonal anergy as mechanisms to balance B cell tolerance and immunity. Immunol Rev 292, 61–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holla P, et al. (2021) Shared transcriptional profiles of atypical B cells suggest common drivers of expansion and function in malaria, HIV, and autoimmunity. Sci Adv 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sutton HJ, et al. (2021) Atypical B cells are part of an alternative lineage of B cells that participates in responses to vaccination and infection in humans. Cell Rep 34, 108684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weiss GE, et al. (2009) Atypical memory B cells are greatly expanded in individuals living in a malaria-endemic area. J Immunol 183, 2176–2182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ambegaonkar AA, et al. (2020) Expression of inhibitory receptors by B cells in chronic human infectious diseases restricts responses to membrane-associated antigens. Sci Adv 6, eaba6493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Portugal S, et al. (2015) Malaria-associated atypical memory B cells exhibit markedly reduced B cell receptor signaling and effector function. Elife 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Potter KN, et al. (2002) Evidence for involvement of a hydrophobic patch in framework region 1 of human V4-34-encoded Igs in recognition of the red blood cell I antigen. J Immunol 169, 3777–3782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhat NM, et al. (2015) Identification of Cell Surface Straight Chain Poly-N-Acetyl-Lactosamine Bearing Protein Ligands for VH4-34-Encoded Natural IgM Antibodies. J Immunol 195, 5178–5188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richardson C, et al. (2013) Molecular basis of 9G4 B cell autoreactivity in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 191, 4926–4939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cappione A 3rd, et al. (2005) Germinal center exclusion of autoreactive B cells is defective in human systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest 115, 3205–3216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zikherman J, et al. (2012) Endogenous antigen tunes the responsiveness of naive B cells but not T cells. Nature 489, 160–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hart GT, et al. (2016) The Regulation of Inherently Autoreactive VH4-34-Expressing B Cells in Individuals Living in a Malaria-Endemic Area of West Africa. J Immunol 197, 3841–3849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hopp CS, et al. (2021) Plasmodium falciparum-specific IgM B cells dominate in children, expand with malaria, and produce functional IgM. J Exp Med 218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muellenbeck MF, et al. (2013) Atypical and classical memory B cells produce Plasmodium falciparum neutralizing antibodies. J Exp Med 210, 389–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rivera-Correa J, et al. (2017) Plasmodium DNA-mediated TLR9 activation of T-bet(+) B cells contributes to autoimmune anaemia during malaria. Nat Commun 8, 1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jenks SA, et al. (2018) Distinct Effector B Cells Induced by Unregulated Toll-like Receptor 7 Contribute to Pathogenic Responses in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Immunity 49, 725–739 e726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tipton CM, et al. (2015) Diversity, cellular origin and autoreactivity of antibody-secreting cell population expansions in acute systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Immunol 16, 755–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang S, et al. (2018) IL-21 drives expansion and plasma cell differentiation of autoreactive CD11c(hi)T-bet(+) B cells in SLE. Nat Commun 9, 1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu XN, et al. (2014) Defective PTEN regulation contributes to B cell hyperresponsiveness in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med 6, 246ra299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liossis SN, et al. (1996) B cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus display abnormal antigen receptor-mediated early signal transduction events. J Clin Invest 98, 2549–2557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hirako IC, et al. (2015) DNA-Containing Immunocomplexes Promote Inflammasome Assembly and Release of Pyrogenic Cytokines by CD14+ CD16+ CD64high CD32low Inflammatory Monocytes from Malaria Patients. mBio 6, e01605–01615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Knackstedt SL, et al. (2019) Neutrophil extracellular traps drive inflammatory pathogenesis in malaria. Sci Immunol 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalantari P, et al. (2014) Dual engagement of the NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasomes by plasmodium-derived hemozoin and DNA during malaria. Cell Rep 6, 196–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Parroche P, et al. (2007) Malaria hemozoin is immunologically inert but radically enhances innate responses by presenting malaria DNA to Toll-like receptor 9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, 1919–1924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Moulton VR and Tsokos GC (2015) T cell signaling abnormalities contribute to aberrant immune cell function and autoimmunity. J Clin Invest 125, 2220–2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Obeng-Adjei N, et al. (2015) Circulating Th1-Cell-type Tfh Cells that Exhibit Impaired B Cell Help Are Preferentially Activated during Acute Malaria in Children. Cell Rep 13, 425–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ferreira MU, et al. (2004) Antigenic diversity and immune evasion by malaria parasites. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 11, 987–995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burnett DL, et al. (2018) Germinal center antibody mutation trajectories are determined by rapid self/foreign discrimination. Science 360, 223–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nemazee D (2017) Mechanisms of central tolerance for B cells. Nat Rev Immunol 17, 281–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tan C, et al. (2019) Self-reactivity on a spectrum: A sliding scale of peripheral B cell tolerance. Immunol Rev 292, 37–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Quach TD, et al. (2011) Anergic responses characterize a large fraction of human autoreactive naive B cells expressing low levels of surface IgM. J Immunol 186, 4640–4648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tiller T, et al. (2010) Development of self-reactive germinal center B cells and plasma cells in autoimmune Fc gammaRIIB-deficient mice. J Exp Med 207, 2767–2778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Paul E, et al. (2007) Follicular exclusion of autoreactive B cells requires FcgammaRIIb. Int Immunol 19, 365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Espeli M, et al. (2019) FcgammaRIIb differentially regulates pre-immune and germinal center B cell tolerance in mouse and human. Nat Commun 10, 1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]