Abstract

Background:

Health literacy is a determinant of health. Few studies characterize its association with surgical outcomes.

Methods:

Retrospective cohort study of patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery 2015–2020. Health literacy assessed using Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool. Outcomes were postoperative complications, LOS, readmissions, mortality.

Results:

Of 552 patients, 46 (8.3%) had limited health literacy, 506 (91.7%) non-limited. Median age 57.7 years, 305 (55.1%) patients were female, 148 (26.8%) were Black. Limited patients had higher rates of overall complications (43.5% vs. 24.3%, p=0.004), especially surgical site infections (21.7% vs. 11.3%, p=0.04). Limited patients had longer LOS (5 vs 3.5 days, p=0.006). Readmissions and mortality did not differ. On multivariable analysis, limited health literacy was independently associated with increased risk of complications (OR 2.03, p=0.046), not LOS (IRR 1.05, p=0.67).

Conclusion:

Limited health literacy is associated with increased likelihood of complications after colorectal surgery. Opportunities exist for health-literate surgical care to improve outcomes for limited health literacy patients.

Keywords: Health literacy, surgical outcomes, surgical disparities, colorectal surgery

Introduction

Health literacy is “the degree to which an individual has the capacity to obtain, communicate, process and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions”1. Limited health literacy has been linked to poor outcomes in many chronic medical conditions such as chronic kidney disease, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease2–4. Importantly, health literacy is modifiable, and health literacy-based interventions have been shown in these conditions to improve outcomes and experiences5–8. Among surgical populations, over one third of surgical patients may be impacted by limited or low health literacy9. The role of health literacy in surgery is not fully understood but has significant implications as health literacy-based interventions positively impact health outcomes and may be readily applied in surgical care.

For many patients, including those with limited health literacy, the surgical journey is complex and filled with papers, instructions, and schedules amidst significant stress. The capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand surgical information is required in every phase of surgery. Early studies have suggested that patients with limited health literacy may experience worse outcomes after surgery including longer lengths-of-stay10–12. These studies, however, have been limited by the inclusion of widely disparate surgical procedures, inclusion of primarily White and/or male patient populations, and exclusion of enhanced recovery programs (ERPs) which are increasingly adopted in surgical care13. In fact, no studies to date have assessed the association of health literacy with surgical outcomes under an ERP. Given that many ERP components require information processing and understanding by the individual patient (i.e. pre-operative education, limited fasting, and early postoperative ambulation), it is plausible that an individual’s health literacy may impact postoperative outcomes under an ERP. This knowledge gap is important to fill as surgeons continue building innovative, and patient-centered, ways to improve surgical outcomes and patient experiences.

To fill this gap and address previous study limitations, our study examined health literacy in a racially-diverse surgical population in the Deep South with a particular focus on colorectal surgery, known for its high-risk of poor surgical outcomes14 and long history with ERPs15. Our objective was to characterize the association between health literacy and 30-day overall postoperative outcomes among this population. We hypothesized that limited health literacy would be associated with worse surgical outcomes including increased rate of complications, increased postoperative length-of-stay, and increased rate of readmissions after colorectal surgery.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study of patients undergoing colorectal surgery at a single academic tertiary-referral center between January 2015 and July 2020. Inclusion criteria for the identification of the retrospective cohort were patients undergoing inpatient elective and major abdominal colorectal surgery, age greater than 18 years and a documented health literacy score in the electronic medical record. Exclusion criteria were patients undergoing emergent surgery or patients undergoing outpatient or ambulatory surgery. Pre-operative patient education materials at the study institution are standardized and written at 6th grade reading level. These materials were updated partway through the study period and reviewed by a committee consisting of patients and patients’ family members to ensure that they were understandable and addressed patients’ needs. This study was approved by the institutional review board at University of Alabama at Birmingham (IRB-160311008).

Health Literacy Assessment

Beginning in 2018, health literacy was routinely assessed as a part of normal clinic triage with the 4-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BRIEF)16 in one colorectal surgeon’s clinic. After the process was streamlined, BRIEF health literacy assessment was more widely implemented in all colorectal surgery clinics for up to 7 colorectal surgeons. This well-validated screening instrument is administered by clinic staff during intake and entered into the electronic medical record. The four items in the instrument are: 1) How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials? 2) How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information? 3) How often do you have a problem understanding what is told to you about your medical condition? 4) How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself? Answers for each question are recorded on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 with a total possible score of 4–20. Limited health literacy is defined as a score of 4–12, marginal 13–16 and adequate 17–20. Previous analysis of our patient population using the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) has demonstrated that up to 24% of patients may have lower levels of health literacy17, however this study uses the patient-reported BRIEF tool to focus on those high-risk patients with the most limited health literacy. As this study was designed a priori to focus on patients with limited health literacy (4–12), the marginal and adequate health literacy groups were combined into one “non-limited” group (13–20). Two-level stratifications for health literacy have been performed in prior studies10,12,18,19. As health literacy assessments were not implemented at our institution until 2018, some patients in this study underwent health literacy assessment outside of the immediate perioperative window if they were still being followed in clinic or returned for another indication. However in existing literature, only 20% of patients have a change in health literacy over time, and the degree of change has been minimal and observed 5–10 years after initial assessment20,21. In this study, all patients underwent assessment and surgery within the same 5-year study period. Thus, significant changes in health literacy resulting in change in classification between limited and non-limited groups are unlikely in this study.

Patient/Procedure-Level Characteristics

Patient-level characteristics including demographics, comorbidities and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Class were defined per the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) and abstracted from the electronic medical record by a trained ACS-NSQIP research nurse and members of the research team. Patient race /ethnicity was self-reported and included in this study as Black patients have been observed to experience disparate surgical outcomes after colorectal surgery22,23. Procedure-level characteristics included procedure and operative approach. During the time period of this study, elective colorectal surgery was routinely performed under an ERP protocol designed within ERAS guidelines as described elsewhere13. Patient enrollment in an ERP protocol was identified in the electronic medical record. ERP compliance was defined as a composite metric based on patients receiving preoperative education, bowel preparation prescription, regional analgesia, intraoperative normothermia and goal-directed fluid therapy, removal of nasogastric tube at completion of surgery, postoperative early oral intake, early mobilization, urinary catheter removal on postoperative day 1, minimization of labs, deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis, and multimodal analgesia with appropriate pain scores.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes

Thirty-day postoperative outcomes were defined per ACS-NSQIP and abstracted from the electronic medical record. Primary outcome was overall rate of postoperative complications within 30 days after surgery. Rates of specific complications were assessed including overall surgical site infection, superficial site infection, deep space infection, organ space infection, wound disruption, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, clostridium difficile infection, sepsis, septic shock, postoperative intubation, ventilator requirement for more than 48 hours after surgery, pulmonary thromboembolism, venous thrombosis, renal insufficiency, renal failure, cerebrovascular accident, cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction and postoperative transfusion. Overall rate of surgical site infections (SSI) was defined as presence of superficial SSI, deep space SSI, or organ space SSI. Timing to complication was assessed by date of diagnosis of complication and whether event occurred during index hospitalization (inpatient) or after discharge (outpatient).

Secondary outcomes were defined as postoperative length-of-stay after index surgery, readmission within 30 days and mortality within 30 days of surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were stratified into “limited” and “non-limited” health literacy groups based on BRIEF score. Bivariate comparisons using Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables and Chi-squire and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables were performed to describe the study population. Multivariable logistic regression modeling was performed using a stepwise approach to calculate odds ratio (OR) for overall postoperative complications among all patients in the study. Negative binomial regression modelling was performed to calculate incidence rate ratio (IRR) for the association between independent variables and LOS among all patients in the study. Backwards model selection with a stepwise method was used. All independent variables were included except factors with <10 occurrences. Selection was based on minimum BIC and AIC. An interaction term was considered between health literacy and race, however did not improve model fit and thus was not included in the final multivariable analysis. All tests were 2-sided with significance defined a priori as alpha 0.05 and performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

552 patients were included in the study. Patient demographics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 46 (8.3%) patients had limited health literacy and 506 (91.7%) had non-limited health literacy. Median age was 57.7 years. Overall, 304 (55.1%) patients were female and 248 (44.9%) male. There were 390 (70.7%) White patients and 148 (26.8%) Black patients, which accurately reflects the demographics of the surrounding state. There were no significant differences in age, BMI, sex, comorbidities, or ASA class between patients with limited and non-limited health literacy. For primary procedure, 261 (47.3%) patients underwent partial colectomy, 109 (19.8%) proctectomy, 69 (12.5%) ostomy closure or reversal, 48 (8.7%) total colectomy, 20 (3.6%) creation or revision of an ostomy and 16 (2.9%) small bowel procedure. 29 (5.0%) patients were classified as “other” procedure type which included appendectomy, parastomal hernia repair, abdominal mass excision, Altemeier or other rectal prolapse procedures. While there was no difference in procedure types between limited and non-limited health literacy patients, limited health literacy patients were more likely to have an open procedure (60.9% limited vs 42.7% non-limited, p=0.02, Table 1). The majority of patients in the study underwent surgery under an enhanced recovery program (ERP). Amongst the 497 ERP patients in the study, ERP compliance was 59.6% and did not vary significantly between limited and non-limited health literacy patients.

Table 1.

Patient and procedure-level characteristics stratified by patient health literacy level, n (%).

| Variable | Overall n=552 | Limited n=46 | Non-Limited n=506 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 57.7 (44.0–67.0) | 57.3 (46.0–67.0) | 57.7 (43.9–67.0) | 0.42 |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 27.4 (23.6–32.4) | 27.7 (25.0–33.8) | 27.4 (23.5–32.2) | 0.27 |

| 304 (55.1) | 25 (54.4) | 279 (55.1) | ||

| Male | 248 (44.9) | 21 (44.7) | 227 (44.9) | |

| 148 (26.8) | 16 (34.8) | 132 (26.1) | ||

| 390 (70.7) | 27 (58.7) | 363 (71.7) | ||

| 8 (1.4) | 2 (4.4) | 6 (1.2) | ||

| 4 (0.7) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (0.6) | ||

| 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Unreported | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| 17 (3.1) | 2 (4.6) | 15 (3.0) | 0.58 | |

| 106 (19.2) | 5 (10.9) | 101 (20.0) | 0.13 | |

| 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.76 | |

| 9 (1.6) | 1 (2.2) | 8 (1.6) | 0.76 | |

| 17 (3.1) | 2 (4.4) | 15 (3.0) | 0.60 | |

| 30 (5.4) | 5 (10.9) | 25 (4.9) | 0.24 | |

| 52 (9.4) | 4 (8.7) | 48 (9.5) | ||

| 248 (44.9) | 23 (50.0) | 225 (44.5) | 0.47 | |

| 5 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.0) | 0.50 | |

| 101 (18.3) | 8 (17.4) | 96 (18.4) | 0.87 | |

| 21 (3.8) | 1 (2.2) | 20 (4.0) | 0.55 | |

| 60 (11.0) | 5 (11.1) | 55 (11.0) | 0.97 | |

| 4 (0.7) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (0.6) | 0.23 | |

| Renal failure | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | 0.60 |

| 112 (20.4) | 5 (10.9) | 107 (21.3) | ||

| 406 (74.0) | 39 (84.8) | 367 (73.0) | ||

| 4 | 31 (5.7) | 2 (4.4) | 29 (5.8) | |

| 261 (47.3) | 16 (34.8) | 245 (48.2) | ||

| 109 (19.8) | 11 (23.9) | 98 (19.4) | ||

| 69 (12.5) | 10 (21.7) | 59 (11.7) | ||

| 48 (8.7) | 3 (6.5) | 45 (8.9) | ||

| 29 (5.0) | 4 (8.5) | 25 (4.7) | ||

| 20 (3.6) | 2 (4.4) | 18 (3.6) | ||

| Small Bowel | 16 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (3.2) | |

| 308 (55.8) | 18 (39.1) | 290 (57.3) | ||

| Open | 244 (44.2) | 28 (60.9) | 216 (42.7) | |

| 387 (70.1) | 29 (63.0) | 358 (70.8) | ||

| Malignant | 165 (29.9) | 17 (37.0) | 148 (29.3) | |

| ERP | 497 (90.0) | 42 (91.3) | 455 (89.9) | 0.76 |

| % ERP Compliance | 59.6 ±12.7 | 59 ±12.3 | 59.7 ±12.7 | 0.74 |

BMI indicates body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; ERP, enhanced recovery program.

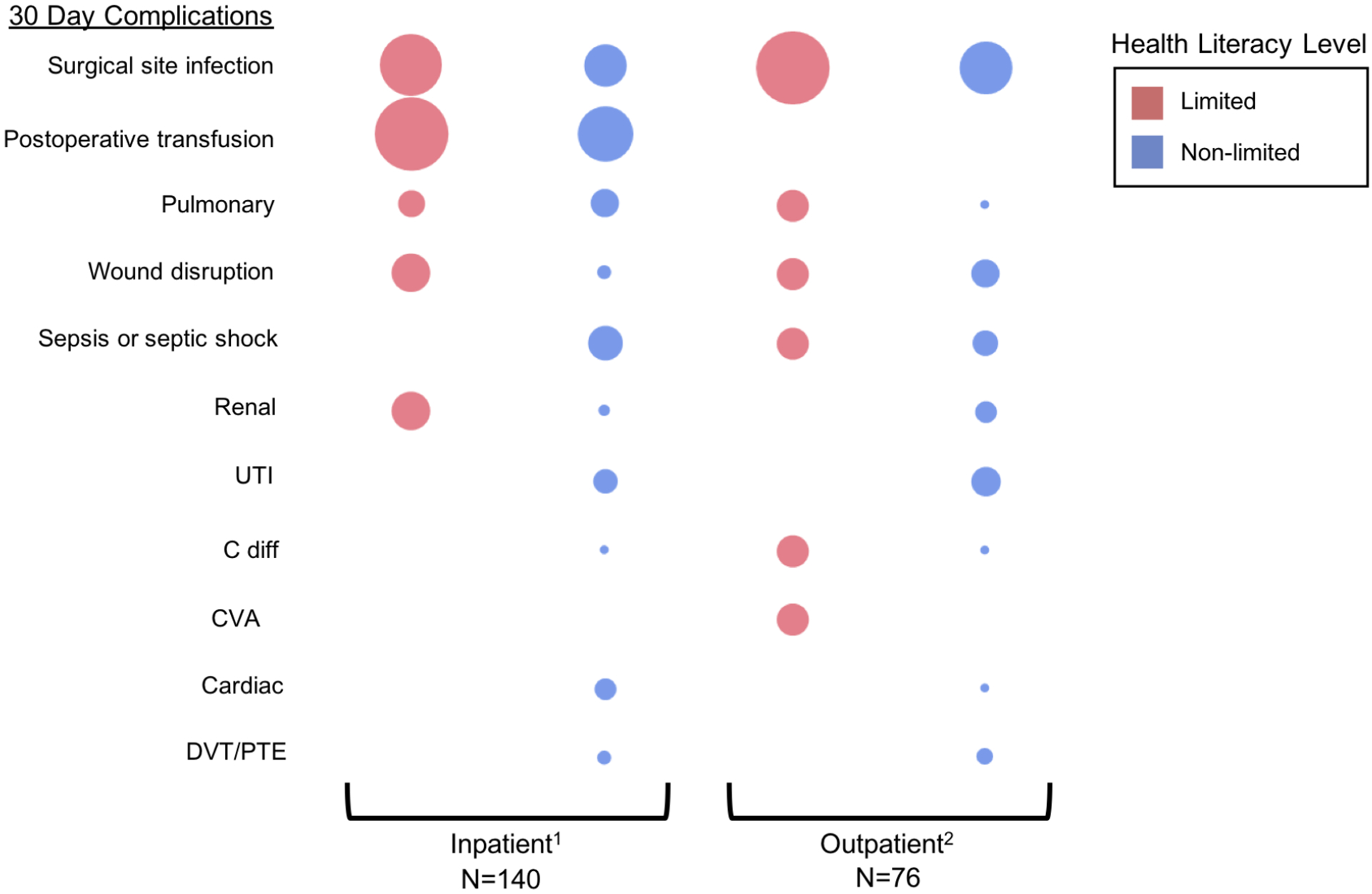

Overall, 143 (25.9%) patients experienced any complication within 30 days after surgery. On unadjusted comparison, postoperative complication incidence varied significantly between limited and non-limited health literacy patients, with 20 (43.5%) limited health literacy patients experiencing a complication versus 123 (24.3%) of non-limited patients (p=0.004, Table 2). Limited health literacy patients experienced higher rates of surgical site infection (21.7% vs. 11.3%, p=0.04, Table 2). In particular, limited health literacy patients were higher risk for deep space infections (10.9% vs. 1.4%, p<0.001). Also, limited health literacy patients had significantly higher risk of renal failure (2.2% vs. 0%, p<0.001) and cerebrovascular accident (2.2% vs. 0%, p<0.001), although only 1 patient in the limited health literacy group experienced each of these complications. Five (10.9%) patients with limited health literacy experienced more than 1 complication, compared to 43 (8.5%) patients with non-limited health literacy (p=0.58). Overall, 140 of 216 (64.8%) total complication events occurred inpatient. There was no difference in rates of inpatient versus outpatient complications between limited and non-limited health literacy patients. The breakdown of type and timing of all complication events for the limited and non-limited health literacy groups is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Unadjusted outcomes stratified by patient health literacy level, n (%).

| Variable | Overall n=552 | Limited n=46 | Non-Limited n=506 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median LOS, days (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) | 3.5 (2.0–6.0) | 0.006 |

| Readmission | 83 (15.2) | 5 (11.4) | 78 (15.5) | 0.47 |

| Mortality | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0.77 |

| Any complication 1 | 143 (25.9) | 20 (43.5) | 123 (24.3) | 0.004 |

| 67 (12.1) | 10 (21.7) | 57 (11.3) | 0.04 | |

| 19 (3.5) | 1 (2.2) | 18 (3.6) | 0.62 | |

| 12 (2.2) | 5 (10.9) | 7 (1.4) | <0.001 | |

| Organ space infection | 36 (6.5) | 4 (8.7) | 32 (6.3) | 0.54 |

| 14 (2.5) | 3 (6.5) | 11 (2.0) | 0.15 | |

| 7 (1.3) | 1 (2.2) | 6 (1.2) | 0.57 | |

| 18 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 18 (3.6) | 0.19 | |

| 3 (0.5) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0.12 | |

| 19 (3.5) | 1 (2.2) | 18 (3.6) | 0.62 | |

| 6 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.2) | 0.46 | |

| 5 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.0) | 0.50 | |

| 3 (0.5) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (0.4) | 0.12 | |

| 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.6) | 0.60 | |

| 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.6) | 0.60 | |

| 8 (1.5) | 1 (2.2) | 7 (1.4) | 0.67 | |

| 1 (0.2) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| 1 (0.2) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | |

| 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) | 0.67 | |

| 6 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (1.2) | 0.46 | |

| Postoperative transfusion | 50 (9.1) | 7 (15.2) | 43 (8.5) | 0.13 |

LOS indicates length of stay.

Calculated as number of patients with at least one complication

Calculated as number of patients with superficial site, deep space, organ space infection

Figure 1.

Breakdown and timing of all complication occurrences for patients with limited and non-limited health literacy. Bubble size reflects relative number of occurrences of each complication type.

DVT indicates deep venous thrombosis; PTE, pulmonary thromboembolism; C diff, clostridium difficile infection; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; UTI, urinary tract infection.

1 Complication presentation prior to discharge from index surgical encounter

2 Complication presentation after discharge from index surgical encounter

Median LOS for the cohort was 4.0 days (Table 2). Patients with limited health literacy had a longer median length-of-stay of 5.0 days vs 3.5 days for patients with non-limited health literacy (p=0.006). Overall, 88 (15.2%) of patients were readmitted within 30 days. There were no significant differences in rates of readmission by health literacy. There was 1 (0.2%) patient mortality in the non-limited health literacy group (p=0.77).

Results of multivariable logistic regression of overall postoperative complications are shown in Table 3. Limited health literacy was independently predictive of overall postoperative complications (OR 2.03, 95% CI 1.01–4.08, p=0.046). Black race/ethnicity vs White (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.05–2.57, p=0.03), dyspnea on exertion (OR 1.21 95% CI 1.21–4.04, p=0.01), ASA class 4 vs ASA class 2 (OR 2.89, 95% CI 1.17–7.15, p=0.02) and disseminated cancer (OR 4.62, 95% CI 1.63–13.09, p=0.004) were associated with increased likelihood of postoperative complications. Laparoscopic approach was protective against postoperative complications (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.30–0.78, p=0.002, Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted analysis of postoperative outcomes using multivariable regression models.

| Overall complications | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Limited health literacy1 | 2.03 | 1.01 | 4.08 | 0.046 |

| Black or African American2 | 1.64 | 1.05 | 2.57 | 0.03 |

| Dyspnea on moderate exertion3 | 1.21 | 1.21 | 4.04 | 0.01 |

| ASA class 44 | 2.89 | 1.17 | 7.15 | 0.02 |

| Disseminated cancer5 | 4.62 | 1.63 | 13.09 | 0.004 |

| Laparoscopic approach6 | 0.48 | 0.30 | 0.78 | 0.002 |

| Postoperative length of stay | ||||

| IRR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Limited health literacy1 | 1.05 | 0.83 | 1.34 | 0.67 |

| Black or African American2 | 1.19 | 1.02 | 1.37 | 0.02 |

| ASA class 44 | 1.75 | 1.30 | 2.37 | <0.001 |

| Laparoscopic approach6 | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.79 | <0.001 |

| Procedure Type7 | ||||

| Total Colectomy | 1.61 | 1.06 | 2.43 | 0.03 |

| Partial Colectomy | 1.17 | 0.81 | 1.69 | 0.41 |

| Proctectomy | 1.13 | 0.77 | 1.67 | 0.52 |

| Closure Ostomy | 1.03 | 0.69 | 1.55 | 0.88 |

| Other | 0.68 | 0.42 | 1.09 | 0.11 |

| Small Bowel | 1.08 | 0.63 | 1.84 | 0.79 |

ASA indicates American Society of Anesthesiologists; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Ref= non-limited health literacy,

Ref= white,

Ref= no dyspnea,

Ref= ASA class 2,

Ref= no disseminated cancer,

Ref= open approach,

Ref= creation or revision of ostomy (shortest LOS)

Results of multivariable linear regression of LOS are also shown in Table 3. Limited health literacy was not significantly associated with LOS on adjusted comparison. Black race/ethnicity vs White (IRR=1.19, 95% CI 1.02–1.37, p=0.02) and ASA class 4 vs ASA class 2 (IRR=1.75, 95% CI 1.30–2.37, p<0.001) were associated with longer LOS. Laparoscopic approach was associated with shorter LOS (IRR=0.68, 95% CI 0.59–0.79, p<0.001). Total colectomy was associated with longer LOS (IRR=1.61, 95% CI 1.06–2.43, p=0.03) when compared to creation or revision of ostomy, which had the shortest length of stay. Partial colectomy, proctectomy, closure of ostomy, small bowel, and other procedures were not significantly associated with LOS.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that health literacy plays an important role in determining surgical outcomes in colorectal surgery even with an ERP. Patients with limited health literacy were at two-fold increased odds of developing a postoperative complication. In particular, patients with limited health literacy experienced significantly higher rates of surgical site infections. This is the first study to demonstrate an independent association between limited health literacy and complications after colorectal surgery. Our study addresses the limitations of previous studies by using ACS-NSQIP defined variables, including a more racially and gender-diverse patient cohort, and reducing procedure heterogeneity through the inclusion of colorectal-specific procedures and care under an ERP. Our findings implicate health literacy as a potential target for quality improvement efforts and highlight a need for more health literate care in surgery.

Although the relationship between health literacy and chronic disease has been widely studied2–4, few studies have linked health literacy to outcomes after surgery. In the largest study to date of 1239 patients, Wright et al. found that limited health literacy was associated with a 1-day increase in length-of-stay after gastric, colorectal, hepatic, or pancreatic resection10. Low health literacy has also been shown to lead to higher rates of minor complications after radical cystectomy11 and increased risk for readmission after elective surgery in a Veteran’s Affairs population12. However, no study to date has demonstrated an association between health literacy and overall postoperative complications. Our study builds on the small body of surgical literature by showing that limited health literacy is associated with increased likelihood of developing complications after colorectal surgery, and that patients with limited health literacy may be at particularly high risk for surgical site infections. In our study, limited health literacy patients did not experience higher rates of readmission, nor was health literacy associated with LOS on adjusted comparison as has been previously observed in other cohorts. These findings may be, in part, impacted by the widespread use of ERP at our institution, which has been shown in the past to mitigate disparities in LOS13 and reduce readmissions24. ERPs, and their heavy emphasis on standardizing patient education, may represent an early example of a health literacy-sensitive intervention, however our study suggests that further room for improvement exists.

Several factors may place limited health literacy patients at higher risk for postoperative complications. Existing literature has demonstrated that patients with low health literacy are at risk for decreased preoperative medication adherence and understanding of preoperative information25,26. Patients with limited health literacy in our study were at highest risk for surgical site infections. This could possibly be driven by lower rates of bowel preparation adherence among these patients, as mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation has been shown to decrease postoperative infection27,28. While the majority of patients in this study had surgery under an ERP and compliance did not differ significantly, our institution measures bowel preparation by the issue of a prescription. Patient adherence with filling the prescription and taking the bowel preparation is unknown. Difficulty understanding post-discharge wound care instructions may further complicate postoperative recovery, particularly for patients with limited health literacy. Previous literature has demonstrated that postoperative materials are frequently written at a level that is not understandable for many patients with low health literacy29. This may contribute to a lower quality of recovery for these patients after surgery30 and perhaps even contribute to increased risk for postoperative complications, especially the 35.2% of complications in our study that were diagnosed after hospital discharge. Further research is needed to better understand these mechanism(s).

Our study identifies important opportunities for intervention for patients with limited health literacy. Newer definitions of health literacy frame its multi-level nature31, and multilevel interventions and health literate models of care are needed to effectively improve surgical outcomes for this high-risk population32. At the individual-level, targeting patient activation, self-efficacy, and understanding may allow patients to better engage in their care33–35. At the provider-level, use of understandable words and revision of patient education materials to feature visuals and text at appropriate reading levels are important5,18,36. Furthermore, multimedia and e-learning interventions may be novel ways to supplement patient education materials, and have been shown to be effective among patients undergoing colonoscopy37–39. At the organizational-level, use of SSI prevention kits has been shown to improve patient adherence with bowel preparation and reduce rates of SSI after colectomy40. This is a novel intervention that may particularly benefit limited health literacy patients at higher risk for SSI. ERPs are another organizational-level intervention that have been shown to improve patient outcomes after surgery41. In our study, ERP compliance did not vary by patient health literacy, representing a protocol that is applicable to patients of all health literacy levels. However, even under an ERP, limited health literacy patients remain at risk for postoperative complications, indicating that further improvement is needed. In order to best reach patients with limited health literacy, federal agencies and national organizations have called for “universal precautions” and widespread implementation of health-literate practices and interventions for all patients, regardless of health literacy level42,43.

Our study has several limitations. First, our assessment of ERP compliance are derived from metrics documented in the electronic medical record. While the rates of bowel preparation are extracted from a prescription order, for example, the true rates of patient adherence to the regimen are unknown. Thus, ERP compliance may be overestimated in this study, particularly as it pertains to preoperative mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation. Second, as this was a retrospective study, some patients underwent health literacy assessment outside of the immediate perioperative window. While significant changes in health literacy resulting in change in classification between limited and non-limited health literacy groups are unlikely during the time period of this study, this limitation could result in either under or overestimation of the effect of health literacy on postoperative outcomes. Third, this study is limited by the size of the patient cohort and may be underpowered to detect significant differences in other outcomes. However, this study is strengthened by homogenous case types in this cohort. Fourth, this study only assesses the difference in objective clinical outcomes between patients with varying levels of health literacy, and does not assess other important metrics such as clinic or surgery cancellations, or disease surveillance and follow up. Fifth, even though patient education materials at the study institution are standardized, there may be differences in pre-operative teaching between surgeons which confound the effect of health literacy on patient outcomes. Additionally, patients with limited health literacy were more likely to undergo open surgery. Despite operative approach being included in the multivariable model, there may be additional variables that increase surgical risk that are not captured by NSQIP. Thus, this study could overestimate the effect of health literacy on postoperative outcomes. Lastly, this is a single-institution study and thus findings may not be widely generalizable to other patient populations. While our study population is more diverse than past studies with 26.8% of patients being Black, very few patients in the study were from other racial/ethnic minority groups, thus limiting generalizability of these findings to those patients.

Conclusion

Limited health literacy was independently associated with two-fold increased odds of postoperative complications after colorectal surgery. In particular, patients with limited health literacy are at high risk for surgical site infections. Opportunities exist to develop, implement, and adopt more health literate care in surgery to improve outcomes for patients with limited health literacy.

Highlights.

Limited health literacy patients have 2x higher odds of postoperative complications

Limited health literacy patients are at the highest risk for surgical site infections

Opportunities exist for more health literate care to optimize surgical outcomes

Acknowledgements

Author Contributions:

The authors would like to thank Ashley Webster for her assistance with data acquisition.

Funding:

DIC supported in part by the NIH and University of Alabama at Birmingham [K12 HS023009 2017–2019 and K23 MD013903 2019–2022] and the UAB Health Services Foundation General Endowment Fund 2018–2020. LMT is supported by the Veterans Affairs Quality Scholars fellowship 2019–2021. CS supported by the NIH [U54MD000502 2020–2021], the University of Alabama at Birmingham [T32 2T32HS013852-11 2020–2022], and the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarship Award 2020–2022.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Meeting Presentation: This study was presented at the American College of Surgeons Quality and Safety Conference in August of 2020.

No authors have any financial or commercial conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- 1.Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. In: Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor DM, Fraser S, Dudley C, et al. Health literacy and patient outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2018;33(9):1545–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey SC, Brega AG, Crutchfield TM, et al. Update on health literacy and diabetes. The Diabetes educator. 2014;40(5):581–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puente-Maestu L, Calle M, Rodríguez-Hermosa JL, et al. Health literacy and health outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory medicine. 2016;115:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Näslund U, Ng N, Lundgren A, et al. Visualization of asymptomatic atherosclerotic disease for optimum cardiovascular prevention (VIPVIZA): a pragmatic, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2019;393(10167):133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SH, Lee A. Health-Literacy-Sensitive Diabetes Self-Management Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Worldviews on evidence-based nursing. 2016;13(4):324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SH, Utz S. Effectiveness of a Social Media-Based, Health Literacy-Sensitive Diabetes Self-Management Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of nursing scholarship : an official publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing. 2019;51(6):661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren-Findlow J, Coffman MJ, Thomas EV, Krinner LM. ECHO: A Pilot Health Literacy Intervention to Improve Hypertension Self-Care. Health Lit Res Pract. 2019;3(4):e259–e267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang ME, B SJ; Dos Santos Marques IC; Liwo AN; Chung SK; Richman JS; Knight SJ; Fouad MN; Gakumo CA; Davis TC; Chu DI Health Literacy in Surgery. Health Literacy Research and Practice. 2020;4(1):e46–e65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright JP, Edwards GC, Goggins K, et al. Association of Health Literacy With Postoperative Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Major Abdominal Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(2):137–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarpato KR, Kappa SF, Goggins KM, et al. The Impact of Health Literacy on Surgical Outcomes Following Radical Cystectomy. Journal of health communication. 2016;21(sup2):99–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker S, Malone E, Graham L, et al. Patient-reported health literacy scores are associated with readmissions following surgery. Am J Surg. 2020;220(5):1138–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahl TS, Goss LE, Morris MS, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Eliminates Racial Disparities in Postoperative Length of Stay After Colorectal Surgery. Ann Surg. 2018;268(6):1026–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tevis SE, Kennedy GD. Postoperative Complications: Looking Forward to a Safer Future. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2016;29(3):246–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ljungqvist O, Scott M, Fearon KC. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haun J, Luther S, Dodd V, Donaldson P. Measurement Variation Across Health Literacy Assessments: Implications for Assessment Selection in Research and Practice. Journal of health communication. 2012;17(sup3):141–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marques ICDS, Theiss LM, Baker SJ, et al. Low health literacy exists in the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population and is disproportionately prevalent in older African-Americans. Crohn’s & Colitis 360. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zite NB, Wallace LS. Use of a low-literacy informed consent form to improve women’s understanding of tubal sterilization: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;117(5):1160–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dageforde LA, Box A, Feurer ID, Cavanaugh KL. Understanding Patient Barriers to Kidney Transplant Evaluation. Transplantation. 2015;99(7):1463–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi LC, Wardle J, Wolf MS, von Wagner C. Cognitive Function and Health Literacy Decline in a Cohort of Aging English Adults. Journal of general internal medicine. 2015;30(7):958–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis LM, Kwasny MJ, Opsasnick L, et al. Change in Health Literacy over a Decade in a Prospective Cohort of Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Journal of general internal medicine. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ravi P, Sood A, Schmid M, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Perioperative Outcomes of Major Procedures: Results From the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg. 2015;262(6):955–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girotti ME, Shih T, Revels S, Dimick JB. Racial disparities in readmissions and site of care for major surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218(3):423–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gustafsson UO, Hausel J, Thorell A, Ljungqvist O, Soop M, Nygren J. Adherence to the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol and outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery. Arch Surg. 2011;146(5):571–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Oliveira GS Jr., McCarthy RJ, Wolf MS, Holl J. The impact of health literacy in the care of surgical patients: a qualitative systematic review. BMC surgery. 2015;15:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Flum DR, Cornia PB, Koepsell TD. The impact of low health literacy on surgical practice. Am J Surg. 2004;188(3):250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klinger AL, Green H, Monlezun DJ, et al. The Role of Bowel Preparation in Colorectal Surgery: Results of the 2012–2015 ACS-NSQIP Data. Ann Surg. 2019;269(4):671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Badia JM, Arroyo-García N. Mechanical bowel preparation and oral antibiotic prophylaxis in colorectal surgery: Analysis of evidence and narrative review. Cirugia espanola. 2018;96(6):317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conlin KK, Schumann L. Literacy in the health care system: a study on open heart surgery patients. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2002;14(1):38–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hälleberg Nyman M, Nilsson U, Dahlberg K, Jaensson M. Association Between Functional Health Literacy and Postoperative Recovery, Health Care Contacts, and Health-Related Quality of Life Among Patients Undergoing Day Surgery: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surgery. 2018;153(8):738–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030. In. Washington, DC: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paasche-Orlow MK, Wolf MS. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. American journal of health behavior. 2007;31 Suppl 1:S19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health services research. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dumitra T, Ganescu O, Hu R, et al. Association Between Patient Activation and Health Care Utilization After Thoracic and Abdominal Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(1):e205002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Souza MS, Karkada SN, Parahoo K, Venkatesaperumal R, Achora S, Cayaban ARR. Self-efficacy and self-care behaviours among adults with type 2 diabetes. Applied nursing research : ANR. 2017;36:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowland-Morin PA, Carroll JG. Verbal communication skills and patient satisfaction. A study of doctor-patient interviews. Evaluation & the health professions. 1990;13(2):168–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hassinger JP, Holubar SD, Pendlimari R, Dozois EJ, Larson DW, Cima RR. Effectiveness of a multimedia-based educational intervention for improving colon cancer literacy in screening colonoscopy patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(9):1301–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holubar SD, Hassinger JP, Dozois EJ, Wolff BG, Kehoe M, Cima RR. Impact of a multimedia e-learning module on colon cancer literacy: a community-based pilot study. The Journal of surgical research. 2009;156(2):305–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pendlimari R, Holubar SD, Hassinger JP, Cima RR. Assessment of Colon Cancer Literacy in screening colonoscopy patients: a validation study. The Journal of surgical research. 2012;175(2):221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deery SE, Cavallaro PM, McWalters ST, et al. Colorectal Surgical Site Infection Prevention Kits Prior to Elective Colectomy Improve Outcomes. Ann Surg. 2020;271(6):1110–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varadhan KK, Neal KR, Dejong CH, Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Lobo DN. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2010;29(4):434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brega AG, Freedman MA, LeBlanc WG, et al. Using the Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit to Improve the Quality of Patient Materials. Journal of health communication. 2015;20 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. 2010; https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/index.html.