Abstract

Hematin polymerization is a parasite-specific process that enables the detoxification of heme following its release in the lysosomal digestive vacuole during hemoglobin degradation, and represents both an essential and a unique pharmacological drug target. We have developed a high-throughput in vitro microassay of hematin polymerization based on the detection of 14C-labeled hematin incorporated into polymeric hemozoin (malaria pigment). The assay uses 96-well filtration microplates and requires 12 h and a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta liquid scintillation counter. The robustness of the assay allowed the rapid screening and evaluation of more than 100,000 compounds. Random screening was complemented by the development of a pharmacophore hypothesis using the “Catalyst” program and a large amount of data available on the inhibitory activity of a large library of 4-aminoquinolines. Using these methods, we identified “hit” compounds belonging to several chemical structural classes that had potential antimalarial activity. Follow-up evaluation of the antimalarial activity of these compounds in culture and in the Plasmodium berghei murine model further identified compounds with actual antimalarial activity. Of particular interest was a triarylcarbinol (Ro 06-9075) and a related benzophenone (Ro 22-8014) that showed oral activity in the murine model. These compounds are chemically accessible and could form the basis of a new antimalarial medicinal chemistry program.

Malaria remains one of the most important widespread diseases in the world. It is estimated that there are 300 to 500 million clinical cases of malaria every year and 1.7 to 2.5 million deaths (1). The major concern in the treatment of malaria at present is the increasing resistance of the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum to antimalarial drugs.

Quinoline antimalarials (20), particularly chloroquine, have been the mainstay of antimalarial drug treatment for the past 50 years. The slow development of resistance to chloroquine compared to other drugs (3, 10, 23) and the demonstration that this resistance is structure specific (5, 16) suggest that if a novel chemical class of drug could be developed against the same molecular target as chloroquine, this could have immense clinical value.

It has become increasingly apparent over recent years that chloroquine most likely exerts its antimalarial activity through interaction with hematin in the lysosomal digestive vacuole of the malaria parasite (4, 9, 17, 24). It is believed that this interaction affects the ability of the parasite to adequately sequester the toxic hematin that is released during the process of proteolytic degradation of hemoglobin into hemozoin, an inert pigment that develops within the parasite digestive vacuole during its growth within the erythrocyte. There is some dispute as to whether this sequestration or polymerization is protein mediated (22, 25) or not (2, 7, 9, 14, 15).

The structure of hemozoin is also open to debate. A recent model of the structure of hemozoin (12) suggests that it is not a polymeric substance as originally hypothesized (21) but an association of dimers. However, none of these debates affect the core hypothesis that chloroquine, and possibly many other quinoline antimalarials (8), exerts its activity through binding to hematin (17).

One assay that can be used to readily assess this interaction is the so-called hematin polymerization assay (7, 9, 22), an in vitro assay in which radiolabeled hematin is incorporated into insoluble β-hematin, which is chemically indistinguishable from hemozoin, at an acid pH reflecting the conditions of the lysosomal food vacuole. The ability of quinolines to inhibit this assay correlates directly with their ability to inhibit parasite growth in culture (8).

The simplicity of the assay lends itself to robotic high-throughput screening (HTS) and the chance of identifying novel heme binding pharmacophores that could in turn be suitable leads for the development of medicinal chemistry programs that could lead to new antimalarial drugs. HTS, by which many thousands of compounds can be tested rapidly in low quantities, is an essential part of modern drug discovery (19). The availability of the hematin polymerization assay plus the strong evidence that it represented a validated antimalarial drug target led us to initiate the screening program that we report here. Key features of the program were, first, the ability to identify false positives and nonspecific hits based on the wide range of other assays to which the compound library was subjected and, second, the rapid and synchronized follow-up of hits from this molecular screen with testing of efficacy against P. falciparum in culture and, where appropriate, against Plasmodium berghei in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The Catalyst program was obtained from Molecular Simulations Inc. (San Diego, Calif.). All chemicals were at least of analytical grade. Unlabeled hemin was purchased from Fluka BioChemica (Buchs, Switzerland), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (Buchs, Switzerland), and other standard chemicals were from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Lyophilized [14C]hemin was provided by University of Leeds Innovations Industrial Services Ltd., Leeds, United Kingdom. The assay was carried out on 96-well polypropylene plates (no. 3794; Costar, Integra Biosciences, Wallisellen, Switzerland) and on MultiScreen DV filtration plates (0.65-μm-pore-size, hydrophilic, low-protein-binding Durapore membrane; MADV NOB 10; Millipore, Volketswil, Switzerland). Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM; low-glucose medium), fetal bovine serum, penicillin, streptomycin, and trypsin were from Gibco BRL (Basel, Switzerland). The compounds for testing were obtained from the Hoffmann-La Roche inventory. They included solid organic synthetic compounds with molecular weights between 175 and 800 Da, compounds of commercial origin (SPECS, Rijswijk, The Netherlands), purified compounds of natural origin (Natural Compound Collection [NCC]), and microbial broths. Microbial broths were from actinomycetes, fungi, and bacteria, mostly isolated from Japanese soil samples. The organisms were inoculated into various media (9 ml) in polypropylene bottles (Yasumoto Kasei Co. Ltd., Hatogaya Saitama, Japan) with shaking (160 rpm) at 27°C for 5 days. The whole culture broths including mycelia were lyophilized, and 11 ml of methanol (MeOH) was added. The MeOH solution was stirred and then filtered. After evaporation of MeOH, the samples were redissolved in 1 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and used for the assay. This DMSO solution was added to the assay solution at a final concentration of 1% (vol/vol). An acetonitrile extract from a trophozoite lysate of P. falciparum was prepared as previously described (7, 9).

Hematin polymerization high-throughput screen.

The hematin polymerization assay (7, 9, 22) was modified for HTS; semiautomated HTS in a 96-well plate format was done using a Zymark bioassay robot system. The reaction was carried out in a total volume of 100 μl consisting of 500 mM sodium acetate (pH 4.8), unlabeled hemin at a final concentration of 100 μM, 0.56 nCi of [14C]hemin, an acetonitrile extract of P. falciparum trophozoite lysate (10 μl), and compounds added as DMSO solutions (10 μl). The components were dispensed into the 96-well polypropylene plate using a Quadra 96 (96-tip channel dispenser; Tomtec Inc., Hamden, Conn.) except for the acetonitrile extract, for which a Uniflex Mechatropet quartette was used. The mixture was incubated overnight at 37°C. After incubation, assay mixtures were transferred into MultiScreen DV filtration plates, filtered, and washed once with 400 μl of 100 mM NaHCO3–0.2% SDS and twice with 200 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) using the Zymark system. The intensive wash step is necessary to remove nonpolymeric, precipitated material. The incorporation of [14C]hematin into the polymer was quantified by scintillation counting using the Wallac 1450 MicroBeta liquid scintillation counter.

In vitro measurement of parasite growth inhibition.

The compounds, added as DMSO solutions, were tested by the semiautomated microdilution assay against the intraerythrocytic form of P. falciparum as described previously (16, 18), based on the method of Desjardins et al. (6). This measures the incorporation by the parasite of radiolabel from [3H]hypoxanthine, a nucleic acid precursor, into its RNA and DNA. Compounds were tested for inhibitory effect against P. falciparum growth in culture by using both the chloroquine-sensitive strain NF54 (an airport strain of unknown origin that is sensitive to standard antimalarials) and the chloroquine-resistant strain K1 (from Thailand).

Drug testing was carried out in 96-well microtiter plates. The compounds, dissolved in DMSO, were titrated in duplicate in serial twofold dilutions over a 64-fold range in culture medium. Parasite cultures with an initial parasitemia (expressed as the percentage of erythrocytes infected) of 0.75% in a 2.5% erythrocyte suspension were added and incubated for 48 or 72 h. The growth of the parasites was measured by the incorporation of radiolabeled [3H]hypoxanthine added 16 h prior to termination of the test. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was estimated by Logit regression analysis.

In vivo measurement of parasite growth and antimalarial activities of compounds. (i) Method of infection of animals.

Male mice (Fü albino; specific pathogen free) weighing 20 ± 2 g were infected intravenously with 2 × 107 P. berghei ANKA strain-infected erythrocytes from donor mice on day 0 of the experiment. Heparinized blood was taken from donor mice with circa 30% parasitemia and was diluted in physiological saline to 108 parasitized erythrocytes/ml. An aliquot (0.2 ml) of this suspension was injected intravenously into experimental and control groups of mice. In untreated control mice, parasitemia rose regularly to 30 to 40% by day +3 after infection and to 70 to 80% by day +4. The mice died between days +5 and +7 after infection.

(ii) Administration of compounds.

Compounds were prepared at appropriate concentrations, either as solutions or as suspensions containing 3% ethanol (EtOH) and 7% Tween 80. They were administered either subcutaneously (s.c.) or per os (p.o.), in a total volume of 0.01 ml per g of body weight.

(iii) Measuring parasite growth inhibition.

Determinations of parasite growth inhibition were made by the test of Peters et al. (13). Groups of five mice were used. On day +3, blood smears of all animals were prepared and stained with Giemsa stain. Parasitemia was determined microscopically, and the difference between the mean value for the control group (taken as 100%) and that for each experimental group was calculated and expressed as percent reduction.

Cytotoxicity assay.

The HeLa cell suspension was diluted in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 U of penicillin/ml, and 50 μg of streptomycin/ml to 2 × 104 cells/ml. The diluted cell suspension was dispensed into a microtiter plate, and then the test compound was added at different concentrations. The final number of cells was 105/ml. The cells were incubated under 5% CO2 at 37°C for 3 days. The culture medium was discarded, and to each well was added 100 μl of a solution containing 0.05% (wt/vol) crystal violet, 7.5% (vol/vol) formalin, and 10% (vol/vol) EtOH. The intensity of the color was measured as the optical density at 630 nm. Only living cells were stained, because they were attached to the bottom of the microtiter plate while the dead cells were discarded together with the culture medium.

Selectivity test.

All compounds tested had previously been run in a series of more than 50 other molecular assays. For example, compounds inhibiting hematin polymerization were also tested for their interaction with DNA gyrase, RNA polymerase II, deformylase, folate biosynthesis, ras/raf-1 binding, UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase, and cyclin E/cyclin-dependent kinase 2, among others. Results of these selectivity tests were used to distinguish between “hits” specific to hematin polymerization and compounds with nonspecific binding properties.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Establishing the assay.

The hematin polymerization assay was used in a high-throughput format to identify compounds with activities equal to or better than that of chloroquine (IC50, <100 μM) that were not of the quinoline class. Various reagents, including trophozoite lysate (22), purified β-hematin (7), acetonitrile extracts of trophozoite lysate and β-hematin (7, 9), and lipids (2, 9), have been used to initiate the hematin polymerization assay. At the time this work was initiated, we were focusing on utilizing acetonitrile extracts from P. falciparum trophozoite lysates (7, 9) and preferred these to trophozoite lysates. This was because (i) the reaction mixtures were easier to filter than with the protein-rich trophozoite lysate and (ii) there was less assay interference through nonspecific binding of compounds to lysate proteins (9). We subsequently demonstrated that the major component of the acetonitrile extracts that initiated the hematin polymerization process was lipid (9). It is therefore likely that an appropriate lipid mixture or an acetonitrile extract of another cell type, e.g., erythrocytes, could have proven just as effective for this work as an acetonitrile extract from malaria trophozoites.

This assay was readily adapted into a 96-well-format filtration assay that could be semirobotized by use of a Zymark robot. This was important because microtiter plates offer several advantages over larger vessels, such as Eppendorf tubes, for compound screening. These include the following: (i) samples are easily and quickly tested in duplicate or triplicate, (ii) plate handling can be automated or semiautomated, (iii) the assay can be monitored by microplate readers, and (iv) the assay throughput is increased. In preliminary studies, the product of the hematin polymerization reaction in microtiter plates was monitored and the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic characteristics (distinct peaks at 1,660 and 1,210 cm−1) demonstrated that the product was essentially β-hematin (9).

Assessment of interfering substances.

In a preliminary experiment the effects of possible interfering substances were examined (Table 1). Most of the compounds tested had no influence on the hematin polymerization activity. Of importance, however, was the need to assess the effects of certain organic solvents, as broths and compounds to be screened were mainly dissolved in organic solvents. For this reason, the effects of DMSO, MeOH, and EtOH on hematin polymerization activity were examined. Each solvent was added to the standard assay mixture at concentrations of 0.5 to 10% (vol/vol). DMSO, MeOH, and EtOH did not inhibit the hematin polymerization reaction at the concentrations tested; indeed, they enhanced the hemozoin-forming activities. This might be caused by an increased solubility of hematin, which tends to precipitate in aqueous solutions at the pH of the digestive vacuole (pH 4.8 to 5.2). Salts had only minor inhibitory effects on the polymerization reaction. NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, NaH2PO4, and NH4Cl at 100 mM concentrations inhibited hematin polymerization by only 10 to 15%; 100 mM Na2HPO4 inhibited the polymerization by about 25%, whereas CaCl2 had no inhibitory effect. The assay was sensitive to detergents, which showed inhibitory activities ranging from about 40% (1% [wt/vol] Triton X-100 or SDS) to 90% (1% [vol/vol] Tween 80). Hematin polymerization was also susceptible to reducing agents, as described previously (9, 11). It is postulated that hemozoin–β-hematin consists of an ionic polymer of hematin monomers (21) or an association of dimers (12) in their oxidized Fe(III) state (21). If oxidation to the Fe(III) state is a precondition for hematin polymerization, one would expect reducing agents to significantly inhibit the process. Glutathione (GSH) and dithiothreitol (DTT) at concentrations of 100 μg/ml inhibited hematin polymerization by 41 and 89%, respectively. Interestingly, cysteine did not inhibit the reaction. The polymerization reaction was independent of protein, and the activity of the trophozoite acetonitrile extract has previously been shown to be resistant to proteinase K treatment (7). Other proteases, such as actinase E or S peptidase, also had no inhibitory effect on the hematin polymerization activity. Results for representative samples of substances tested for their influence on hematin polymerization activity are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Effects of substances possibly interfering with the hematin polymerization reaction

| Class and compound | Concn | % Inhibition | IC50 | Concn tolerated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cations and anions | ||||

| NaCl | 100 mM | 10 | ||

| KCl | 100 mM | 10 | ||

| NH4Cl | 100 mM | 14 | ||

| MgCl2 | 100 mM | 16 | ||

| CaCl2 | 100 mM | −15 | ||

| Na2HPO4 | 100 mM | 26 | ||

| NaH2PO4 | 100 mM | 14 | ||

| Detergents | ||||

| Tween 80 | 1% | 88 | 0.14% | 0.003% |

| Triton X-100 | 1% | 37 | ||

| SDS | 1% | 46 | ||

| Chelating agents | ||||

| EDTA | 10 mM | −19 | ||

| EGTA | 10 mM | −10 | ||

| Tannins | ||||

| Catechin | 100 μg/ml | 11 | ||

| Gallic acid | 100 μg/ml | −43 | ||

| Tannic acid | 100 μg/ml | 100 | 34 μg/ml | 3 μg/ml |

| Pigments | ||||

| Chlorophyll a | 100 μg/ml | 33 | ||

| Chlorophyll b | 100 μg/ml | 28 | ||

| Melanin | 100 μg/ml | 40 | ||

| Saponin (saikosaponin A) | 100 μg/ml | −9 | ||

| Antibiotics | ||||

| Daunomycin | 100 μg/ml | −27 | ||

| Amphotericin B | 100 μg/ml | 4 | ||

| Penicillic acid | 100 μg/ml | −19 | ||

| Actinomycin D | 100 μg/ml | 37 | ||

| SH-group reacting agents | ||||

| DTT | 100 μg/ml | 89 | 5.1 μg/ml | 1 μg/ml |

| Cysteine | 100 μg/ml | −13 | ||

| GSH | 100 μg/ml | 41 | ||

| Fatty acids | ||||

| Stearic acid | 100 μg/ml | 11 | ||

| Oleic acid | 100 μg/ml | 30 | ||

| Linoleic acid | 100 μg/ml | −15 | ||

| Proteases | ||||

| Actinase E | 10 μg/ml | −13 | ||

| S peptidase | 10 μg/ml | −29 | ||

| Proteinase K | 10 μg/ml | −6 | ||

| Organic solvents | ||||

| MeOH | 10% | −29 | ||

| EtOH | 10% | −28 | ||

| Acetonitrile | 10% | −40 | ||

| DMSO | 10% | −37 |

Overview of process for compound testing and hit rate.

The majority of the Roche compound library at the time of this activity was stored as cocktails of 10 compounds that were later tested individually if the cocktail produced a hit. A total of 11,887 Roche chemical cocktails (mixtures of 10 synthetic compounds), 15,760 samples obtained from SPECS, 97 purified samples from the NCC, 1,380 compounds selected from a number of diverse combinatorial chemistry libraries, and 14,640 microbial broths were screened for inhibitory activity toward hematin polymerization (Table 2). Compounds from the NCC are of natural origin and were isolated from microbial broths.

TABLE 2.

Results of tests for inhibition of hematin polymerization

| Chemical source of compounds | No. of compounds in primary screening | No. (%) of hits in:

|

No. (%) of active single compounds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary screening | Reassay | |||

| Roche cocktails | 11,887 | 268 (2.3) | 69 (0.6) | 38 (0.3) |

| NCC | 97 | 16 (16) | 16 (16) | 5 (5.2) |

| SPECS | 15,760 | 36 (0.2) | 13 (0.1) | |

| Combinatorial chemistry libraries | 1,380 | 0 | ||

| Microbial broths | ||||

| Actinomycetes | 6,000 | 23 (0.4) | 3 (0.1) | 0 |

| Fungi | 6,320 | 42 (0.7) | 17 (0.3) | 10 (0.2) |

| Bacteria | 2,320 | 13 (0.6) | 4 (0.2) | 1 |

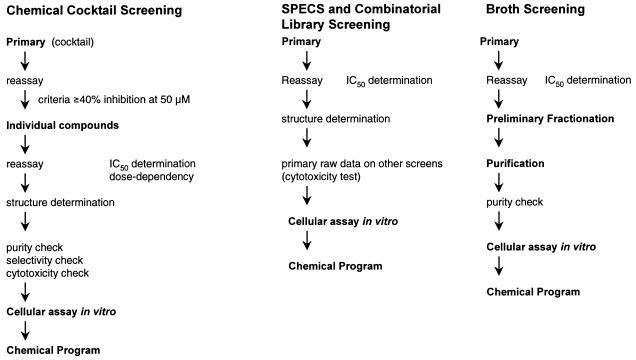

Figure 1 shows the “screening cascade” for chemical cocktails, SPECS compounds, and microbial broths. As described above, the chemical cocktails were composed of 10 single compounds each. If the initial primary screening of the cocktails gave an inhibition greater than 40% at a concentration of 50 μM, the cocktails were first retested to confirm activity and then tested as individual compounds to identify the active compound and determine an IC50. After further selectivity and cytotoxicity tests of hits, the compounds were examined for activity against intact parasites in culture.

FIG. 1.

Screening cascade for chemical cocktails, SPECS compounds, and microbial broths. Schematically shown are the procedures and selection criteria leading from primary screening to in vitro testing and the start of a medicinal chemistry program. First, the inhibitory activity should be above a defined value (e.g., ≥40% inhibition at 50 μM) and must be confirmed; second, the structure must be of interest (acceptable molecular weight; lipophilicity) and have a potential for chemical variations; third, the identified hit would, preferentially, have in vitro activity.

SPECS compounds and compounds from combinatorial chemistry libraries were screened as single compounds, so no additional deconvolution step was necessary, and the IC50 was determined immediately after primary screening. Subsequent steps were the same as those described for chemical cocktails. For the screening of compounds of natural origin (broth screening), the “active principle” of the broth had to be isolated and purified and its structure had to be identified.

Follow-up activities and selection of compounds for potential lead development relied primarily on whether the compounds also displayed antimalarial activity in vitro and/or in vivo and on their chemical accessibility.

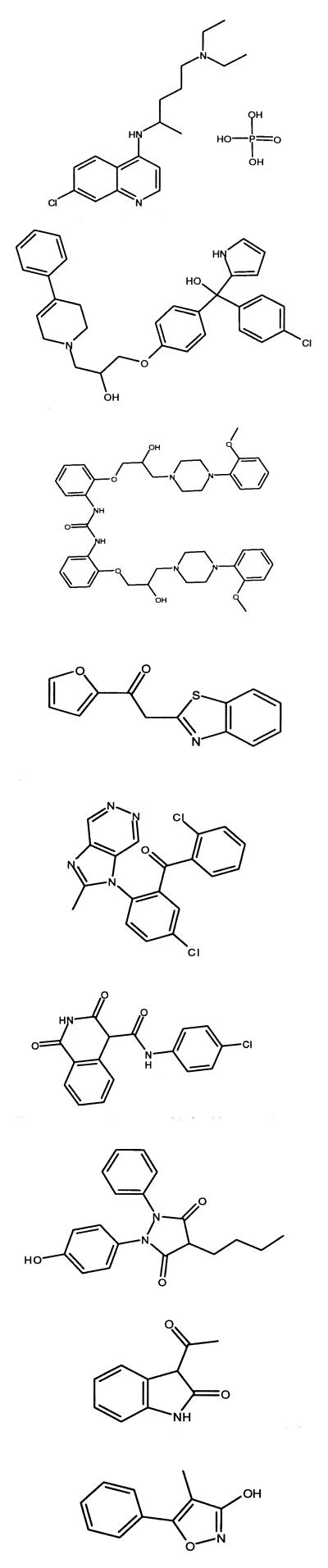

Potential lead compounds identified.

More than 100,000 compounds were tested. Of these, 45 nonquinoline compounds had IC50s of less than 50 μM in the hematin polymerization assay. These compounds belonged to different chemical classes, including triarylcarbinols (Ro 06-9075), piperazines (Ro 10-3428), benzophenones (Ro 22-8014), imides (Ro 20-1120), hydrazides (Ro 04-4410), indoles (Ro 90-2341), and isoxazoles (Ro 90-0987) (Table 3). Quinolines and bisquinolines that were also identified in the hematin polymerization assay were discounted because they did not represent new structural classes. The different structural classes, e.g., triarylcarbinols, piperazines, benzophenones, imides, hydrazides, indoles, and isoxazoles, that were highly active in the hematin polymerization assay were also assessed for activity against P. falciparum growth in culture, both against the chloroquine-sensitive strain NF54 and against the chloroquine-resistant strain K1. The selection criterion was an IC50 of less than 5 μM against both strains. This requirement was fulfilled only by the following lead compounds: Ro 06-9075 (a triarylcarbinol), Ro 10-3428 (a piperazine), Ro 14-3955 (miscellaneous), and Ro 22-8014 (a benzophenone). Of great significance from a drug discovery viewpoint, two of these compounds, Ro 06-0975 and Ro 22-8014, also possessed quite reasonable oral antimalarial activity in the murine P. berghei model. Further titration of their activity (data not shown) demonstrated that significant improvement on this activity was still required before any compound from either of these classes could be considered a drug candidate, but their value as potential antimalarial leads is apparent.

TABLE 3.

Classes of compounds identified as inhibitors of the hematin polymerization reaction in HTS

| Compound class | Structure | IC50 (μM) in hematin polymerization assay | IC50 (μM) against P. falciparum growth in culture

|

% Inhibition of P. berghei growth in vivoa | IC50 (μM) in cytotoxicity assayb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | NF54 | |||||

| Chloroquine (Ro 01-6014) |  |

80 | 0.45 | 0.0125 | 100 | NT |

| Triarylcarbinol (Ro 06-9075) | 30 | 0.97 | 1.16 | 98.4 | 4.66 | |

| Piperazine (Ro 10-3428) | <100 | 0.21 | 0.27 | Inactive | 4.45 | |

| Miscellaneous (Ro 14-3955) | 24 | 1.93 | 2.7 | Inactive | 63.3 | |

| Benzophenone (Ro 22-8014) | 24 | 1.32 | 1.78 | 88 | NT | |

| Imide (Ro 20-1120) | 13 | 16 | 16 | NT | NT | |

| Hydrazide (Ro 04-4410) | 19 | 15.4 | 15.4 | Inactive | NT | |

| Indole (Ro 90-2341) | 14 | 28.5 | 28.5 | NT | NT | |

| Isoxazole (Ro 90-0987) | 12 | 28.5 | 28.5 | NT | NT | |

Mice were treated p.o. with four doses of each test compound at 100 mg/kg of body weight.

With HeLa cells. NT, not tested.

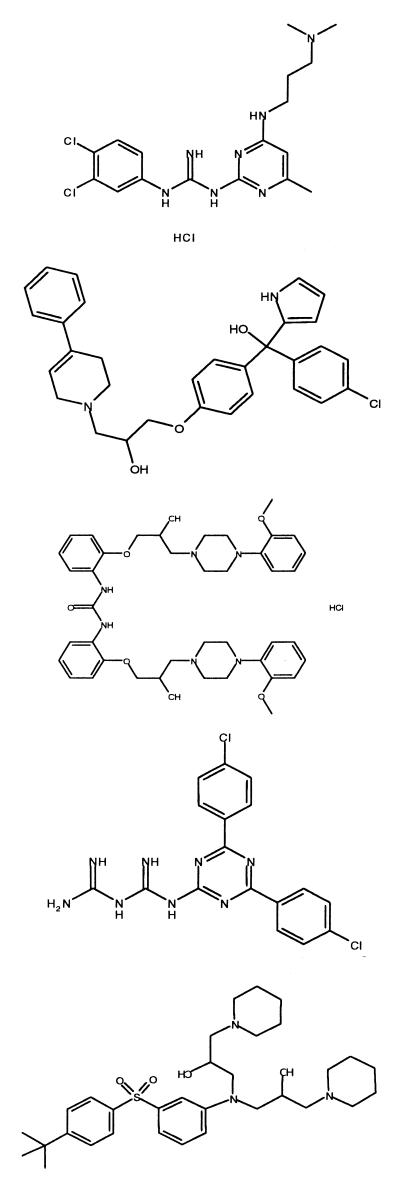

In silico screening of the Roche database using the Catalyst program.

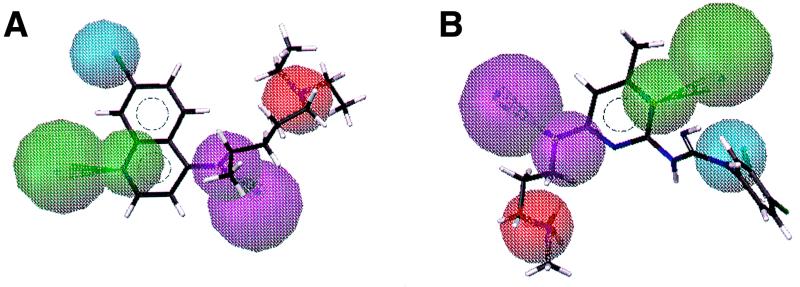

In addition to the random HTS approach outlined, we also proactively looked for potential novel antimalarial structures from the Roche database that had structural features analogous to those of the quinolines and that might mediate their activity through the same mechanism of action. Based on a large amount of data accumulated in screening the 4-aminoquinoline class of compounds, a pharmacophore hypothesis was developed using the Catalyst program. The computer analysis comparing the three-dimensional (3-D) structures, lipophilicity, positions of hydrogen donors and acceptors, and electrostatic relationships of quinoline antimalarials led to the development of a “consensus structure” for antimalarials.

Figure 2 shows the monoquinoline-derived hypothesis. Using the multiconformer database of available Roche compounds, 317 compounds out of 123,000 were found to fulfill the distance constraints of the hypothesis depicted in Fig. 2. Of these, 36 were quinolines and thus were discounted. The remaining 281 selected compounds were assessed in the hematin polymerization assay and tested against malaria parasites in culture. Of these, 107 showed activity against the chloroquine-resistant or nonresistant strain in the 1.5 to 15.0 μM range and 26 of these compounds showed activity in the 0.15 to 1.0 μM range. Some of these hits had previously been identified as having antimalarial activity through testing over many years at Hoffmann-La Roche, but five new structures were identified and are shown in Table 4. Interestingly, two of these compounds, the triarylcarbinol Ro 06-9075 and the piperazine Ro 10-3428, had also been selected through the hematin polymerization screening process (see Table 3), further validating their selection as antimalarial leads that have a mode of action similar to that of chloroquine, namely, interaction with hematin.

FIG. 2.

(A) The monoquinoline-derived hypothesis superimposed on chloroquine. (B) Fit of the monoquinoline-derived hypothesis for Ro 06-8463, which was found by 3-D database screening (activity for the resistant strain K1, 0.3 μM; activity for the sensitive strain NF54, 0.026 μM). Feature definitions: blue, hydrophobic; green, hydrogen bond acceptor; cyan, hydrogen bond donor; red, positive ionizable.

TABLE 4.

Selection of the most active compounds found by 3-D database screening

| Compound structure | Roche no. | IC50 (μM) in hematin polymerization assay | IC50 (μM) against P. falciparum growth in culture

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF54 | K1 | |||

|

Ro 06-8463 | 28 | 0.026 | 0.3 |

| Ro 06-9075 | 30 | 1.16 | 0.97 | |

| Ro 10-3428 | <100 | 0.27 | 0.21 | |

| Ro 10-8995 | 100 | 0.14 | 0.29 | |

| Ro 47-3191 | NTa | 0.46 | 0.3 | |

NT, not tested.

Summary conclusions.

This study demonstrates that the hematin polymerization assay can lead to the identification of novel antimalarial pharmacophores. This further validates the study of hematin polymerization as an antimalarial drug target, possibly in its own right or, at the very least, as a surrogate for assessing the antimalarial interactions of compounds with hematin.

Further biochemical studies (4, 26) have to be undertaken in order to fully demonstrate and prove the mode of action of the compounds identified in this screen. However, the fact that two compounds, the triarylcarbinol Ro 06-9075 and the piperazine Ro 10-3428, were selected as potential antimalarial leads both on the basis of the hematin polymerization screen and on the basis of a Catalyst-derived pharmacophore hypothesis lends a high degree of confidence that the compounds with antiparasitic activity identified in this screen mediate their activity through interaction with hematin.

It should be remembered that the compounds identified in this screen are at an early stage of the drug discovery process. Of those studied so far, the two compounds demonstrating oral activity in the murine P. berghei model, the triarylcarbinol Ro 06-9075 and the benzophenone Ro 22-8014, deserve particular investigation and attention. In addition to confirmation of their mechanism of action, demonstration of an absence of any overt toxicity and the preliminary development of structure-activity relationships through a medicinal chemistry program are required.

While the preliminary nature of the compounds identified through this screen as antimalarial leads has been noted, it is equally important to realize that they also represent a high potential value. There is a great need to discover new antimalarial pharmacophores if innovative antimalarial drugs are to be discovered and developed. Studies such as the one reported here exemplify the value of the HTS process by which a bridge between biological investigation and medicinal chemistry, so necessary for effective drug discovery (19), can be built.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Peter Hartman, Malcolm Page, and Rudolf Then for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ad Hoc Committee on Health Research relating to Future Intervention Options. Report. Investing in health research and development. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendrat K, Berger B J, Cerami A. Haem polymerization in malaria. Nature. 1995;378:138–139. doi: 10.1038/378138a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray P G, Ward S A. A comparison of the phenomenology and genetics of multidrug resistance in cancer cells and quinoline resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;77:1–28. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray P G, Mungthin M, Ridley R G, Ward S A. Access to hematin: the basis of chloroquine resistance. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:170–179. doi: 10.1124/mol.54.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De D, Krogstad F M, Beyers L D, Krogstad D J. Structure-activity relationships for antiplasmodial activity among 7-substituted 4-aminoquinolines. J Med Chem. 1998;41:4918–4926. doi: 10.1021/jm980146x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desjardins R S, Canfield C J, Haynes J D, Chulay J D. Quantitative assessment of antimalarial activity in vitro by a semiautomated microdilution technique. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:710–718. doi: 10.1128/aac.16.6.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorn A, Stoffel R, Matile H, Bubendorf A, Ridley R G. Malarial haemozoin/β-haematin supports haem polymerization in the absence of protein. Nature. 1995;374:269–271. doi: 10.1038/374269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorn A, Vippagunta S R, Matile H, Jaquet C, Vennerstrom J L, Ridley R G. An assessment of drug-haematin binding as a mechanism for inhibition of haematin polymerisation by quinoline antimalarials. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:727–736. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorn A, Vippagunta S R, Matile H, Bubendorf A, Vennerstrom J L, Ridley R G. A comparison and analysis of several ways to promote haematin (haem) polymerisation and an assessment of its initiation in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:737–747. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foley M, Tilley L. Quinoline antimalarials. Mechanism of action and resistance prospects for new agents. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;79:55–87. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monti D, Vodopivec B, Basilico N, Olliaro P, Taramelli D. A novel endogenous antimalarial: Fe(II)-protoporphyrin IXa (heme) inhibits hematin polymerization to β-hematin (malaria pigment) and kills malaria parasites. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8858–8863. doi: 10.1021/bi990085k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pagola S, Stephens P W, Bohle D S, Kosar A D, Madsen S K. The structure of malaria pigment beta-haematin. Nature. 2000;404:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35005132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters W, Portus J H, Robinson B L. The chemotherapy of rodent malaria. XXII. The value of drug resistant strains of P. berghei in screening for blood schizontocidal activity. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1975;69:155–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ridley R G, Dorn A, Matile H, Kansy M. Haem polymerisation in malaria—reply. Nature. 1995;378:138–139. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ridley R G. Haemozoin formation in malaria parasites: is there a haem polymerase? Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:253–254. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)30021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridley R G, Hofheinz W, Matile H, Jaquet C, Dorn A, Masciadri R, Jolidon S, Richter W F, Guenzi A, Girometta M-A, Urwyler H, Huber W, Thaithong S, Peters W. 4-Aminoquinoline analogs of chloroquine with shortened side chains retain activity against chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1846–1854. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridley R G, Dorn A, Vippagunta S R, Vennerstrom J L. Haematin (haem) polymerization and its inhibition by quinoline antimalarials. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:559–566. doi: 10.1080/00034989760932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridley R G, Matile H, Jaquet C, Dorn A, Hofheinz W, Leupin W, Masciadri R, Theil F-P, Richter W F, Girometta M-A, Guenzi A, Urwyler H, Gocke E, Potthast J-M, Csato M, Thomas A, Peters W. Antimalarial activity of the bisquinoline trans-N1,N2-bis(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)cyclohexane-1,2-diamine: comparison of two stereoisomers and detailed evaluation of the S,S enantiomer, Ro 47-7737. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:677–686. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ridley R G. Antimalarial drug discovery and development—an industrial perspective. Exp Parasitol. 1997;87:293–304. doi: 10.1006/expr.1997.4230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridley R G, Hudson A T. Quinoline anti-malarials. Exp Opin Ther Patents. 1998;8:121–136. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slater A F G, Swiggard W J, Orton B R, Flitter W D, Goldberg D E, Cerami A, Henderson G B. An iron-carboxylate bond links the heme units of malaria pigment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:325–329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slater A F G, Cerami A. Inhibition by chloroquine of a novel haem polymerase enzyme activity in malaria trophozoites. Nature. 1992;355:167–169. doi: 10.1038/355167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su X, Kirkman L A, Fujioka H, Wellems T E. Complex polymorphisms in an approximately 330 kDa protein are linked to chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum in Southeast Asia and Africa. Cell. 1997;91:593–603. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80447-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sullivan D J, Jr, Gluzman I Y, Russell D G, Goldberg D E. On the molecular mechanism of chloroquine's antimalarial action. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11865–11870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan D J, Jr, Gluzman I Y, Goldberg D E. Plasmodium hemozoin formation mediated by histidine-rich proteins. Science. 1996;271:219–222. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5246.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan D J, Jr, Matile H, Ridley R G, Goldberg D E. A common mechanism for blockade of heme polymerization by antimalarial quinolines. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31103–31107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]