Abstract

Background

With the rise of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma associated with human papillomavirus (HPV), appropriate treatment strategies continue to be tailored toward minimizing treatment while preserving oncologic outcomes. We aim to compare outcomes of those undergoing transoral resection with or without adjuvant therapy for HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma.

Methods

A case-match cohort analysis was performed at two institutions on patients with HPV-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. All subjects underwent transoral surgery and neck dissection. Patients treated with surgery alone were matched 1:1 to those treated with surgery and adjuvant therapy using two groups identified as confounders: T-stage (T1/2 or T3/4) and number of pathologically positive lymph nodes (≤4 or >4).

Results

105 matched pairs were identified with a median follow-up of 42 months (3.1 to 102.3 months). Patients were staged T1/T2 (86%) or T3/4 (14%). Each group had 5 patients with >4 positive lymph nodes. Adjuvant therapy significantly improved disease free survival (HR 0.067, 95%CI 0.01–0.62) and was associated with a lower risk of local and regional recurrence (RR 0.096, 95%CI 0.02–0.47,). There was no difference in disease specific survival (HR 0.22, 95%CI 0.02–2.57) or overall survival (HR 0.18, 95%CI 0.01–2.4) with the addition of adjuvant therapy. The risk of gastrostomy tube was higher in those receiving adjuvant therapy (RR 7.3, 95%CI 2.6–20.6).

Conclusions

Transoral surgery is an effective approach to treat HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma. The addition of adjuvant therapy appears to decrease the risk of recurrence and improve disease free survival but may not significantly improve overall survival.

Introduction:

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCCa) associated with the human papilloma virus (HPV) continues to rise.1 With the rise of HPV-related OPSCCa, appropriate treatment strategies continue to be tailored toward minimizing the intensity of treatment while preserving oncologic outcomes. Currently, patients with HPV-positive OPSCCa are being treated based on recommendations similar to those with HPV-negative disease, despite these two patient populations having a very different prognosis. Oncologic outcomes of patients with HPV-related OPSCCa tend to be very favorable, which has led to the movement of deintensification of treatment regimens.

The two main treatment options for OPSCCa endorsed by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines are surgery with or without adjuvant therapy or radiation with or without chemotherapy.2 The favorable survival seen with HPV-related OPSCCa has been demonstrated with both treatment approaches.3 At a time where younger and healthier patients are being treated for a cancer with favorable survival, the choice of treatment becomes even more imperative as the treatment toxicities will have an even greater impact on long-term quality of life. The goal to decrease treatment morbidity while maintaining oncologic outcomes has led to the gaining popularity of transoral surgery.

Transoral robotic surgery (TORS) and transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) offer a minimally invasive approach to the oropharynx with similar oncologic outcomes and lower postoperative morbidity than traditional open approaches.4 These surgical techniques have provided a viable treatment option with comparable oncologic outcomes to radiation-based approaches and have provided an additional means of deintensification.5,6 Patients undergoing transoral surgery for HPV-related OPSCCa have low recurrence rates at the primary site and regional nodal basin.7,8 Despite this, these patients are often recommended to undergo adjuvant treatment in the primary setting.

Therefore, we aim to evaluate the oncologic outcomes of patients with HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma undergoing surgery alone in a case matched analysis compared to those undergoing surgery with adjuvant therapy. We also aim to determine factors related to locoregional recurrence and the success rates of salvage treatments. We hypothesize that patients undergoing transoral surgery with neck dissection alone will have higher risk of locoregional recurrence but this will not impact overall survival or disease specific survival secondary to successful salvage.

Materials and Methods:

Institutional review board approval was granted from both study centers of Washington University School of Medicine and Mayo Clinic – Rochester. Data was retrospectively collected on all consecutive patients undergoing transoral resection of HPV-positive OPSCCa at the two academic centers between January 2007 and November 2013.

Patients were identified in the transoral surgery databases maintained at each respective institution. Only patients with pathologically proven HPV-positive OPSCCa from the palatine tonsil or tongue base treated with transoral surgery and neck dissection were included. Patients in the adjuvant therapy group must have completed all recommended radiation or chemoradiation to be included. HPV-related disease was determined by p16 immunohistochemistry. Transoral surgery consisted of either transoral robotic surgery (TORS) or transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) for the primary tumor with selective neck dissection of the involved and high-risk nodal basins. Recommendations for adjuvant therapy were based on multidisciplinary discussion with radiation and medical oncology. For the group undergoing surgery alone, adjuvant therapy was withheld based on these discussions or patient preferences.

All patients were clinically staged with physical examination, CT or MRI of the neck, CT of the chest, and PET/CT scan at the discretion of the treating physician. All tumors were confirmed to be HPV-related squamous cell carcinoma by testing for p16-positivity on immunohistochemistry, and staged pathologically from the surgical specimen according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual 7th edition.9 Locoregional recurrences were determined to be on the date of biopsy or imaging if the patient did not undergo biopsy. Since pathological T-stage and the number of positive lymph nodes are known confounders of treatment impact on survival,10,11 patients undergoing surgery alone were 1:1 matched by T-stage (T1/2 or T3/4) and number of pathologically positive lymph nodes (≤4 or >4) to those undergoing surgery with adjuvant therapy. Matching was performed using SAS statistical software package (SAS 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). If a case had more than one match, only one case was randomly selected as a matched pair.

Smoking status in the respective databases was classified as “current smokers” if the patient was actively smoking at the time of presentation, “former smokers” if they had at least a 10 pack year history but were no longer smoking at the time of presentation, or “non-smoker” if they did not smoke at the time of presentation and did not have a 10 pack year history. Smoking status was then dichotomized for statistical analysis to include “smokers” (current and former smokers) and “non-smokers.”

Statistical analysis:

Descriptive statistics were used to describe distribution of characteristics in each of the two study groups. Bivariate analysis using paired samples t-test for continuous level variables and McNemar’s test for categorical variables were used explore for significant differences in distribution of each of the study variables between the two matched cohorts. Univariable stratified Cox PH regression analysis was used to investigate the association and impact of each of the variables with overall survival (OS), disease specific survival (DSS), and disease free survival (DFS) in the setting of matched cohorts and multivariable Cox regression was used for assessing the impact of adjuvant therapy on survival after controlling for confounding. Date of surgery was defined as time zero for the analysis. Conditional Poisson regressions were used to estimate associations of the variables with recurrence and gastrostomy tube placement. Conditional Poisson regression is the appropriate method for risk estimation in the setting of matched pair cohort data.12,13 Variables significantly associated with each of the outcomes listed in the univariable analysis (evaluated at alpha level of 0.05) were included in multivariable analysis. STATA 12.0 (StataCorp. 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP) was used for statistical analysis.

Results:

A total of 105 matched pairs were identified with a mean age of 62 years (Std. Dev. 9.8 years). There were 174 male and 36 female patients. Median follow-up was 42 months (3.1 to 102.3 months). Of the 105 patients who received adjuvant treatment, 43 patients had radiation and 62 had radiation and chemotherapy. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of the matched pair groups are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and pathologic characteristics

| Surgery (n=105) | Surgery+Adjuvant (n=105) | Percent difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (mean, STDEV) | 63 (10.7) | 61 (8.6) | 2.5 (0.04 to 0.91)a |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 84 (80) | 90 (86) | |

| Female | 21 (20) | 15 (14) | 6 (−4 to 16) |

|

| |||

| Center | |||

| 1 | 47 (45) | 46 (44) | |

| 2 | 58 (55) | 59 (56) | −1 (−14 to 12) |

|

| |||

| Smoking | |||

| No | 63 (60) | 46 (44) | |

| Yes | 42 (40) | 59 (56) | −16 (−29 to −3) |

|

| |||

| ACE-27 | |||

| None | 53 (53) | 52 (50) | 3 (−10 to 17) |

| Mild | 31 (31) | 42 (40) | −11 (−24 to 2) |

| Moderate+Severe | 16 (16) | 11 (10) | 6 (−14 to 12) |

|

| |||

| Subsite | |||

| BOT | 42 (40) | 41 (39) | |

| Tonsil | 62 (60) | 64 (61) | −1 (−14 to 12) |

|

| |||

| Treatment | NA | ||

| Surgery alone | 105 | − | |

| Adjuvant radiation | − | 43 (41) | |

| Adjuvant chemoradiation | − | 62 (59) | |

|

| |||

| ECE | |||

| No | 81 (77) | 35 (33) | |

| Yes | 24 (23) | 70 (67) | −44 (−56 to 32) |

|

| |||

| PNI | |||

| No | 100 (95) | 93 (89) | |

| Yes | 5 (5) | 12 (11) | −6 (−13 to 1) |

|

| |||

| LVI | |||

| No | 93 (89) | 85 (81) | |

| Yes | 12 (11) | 20 (19) | −8 (−18 to 2) |

|

| |||

| Margins | |||

| Negative | 104 (99) | 103 (98) | |

| Positive | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | −1 (−4 to 2) |

|

| |||

| Pathologic T Stage | NA | ||

| 1 and 2 | 90 (86) | 90 (86) | |

| 3 and 4 | 15 (14) | 15 (14) | |

|

| |||

| Lymph node | NA | ||

| <=4 | 100 (95) | 100 (95) | |

| >4 | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | |

Abbreviations: CI – Confidence interval; STDEV – Standard deviation; ACE-27 – Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27; BOT – Base of tongue; ECE – Extracapsular extension; PNI – Perineural invasion; LVI – Lymphovascular invasion; NA – Not applicable

Mean difference and 95% CI

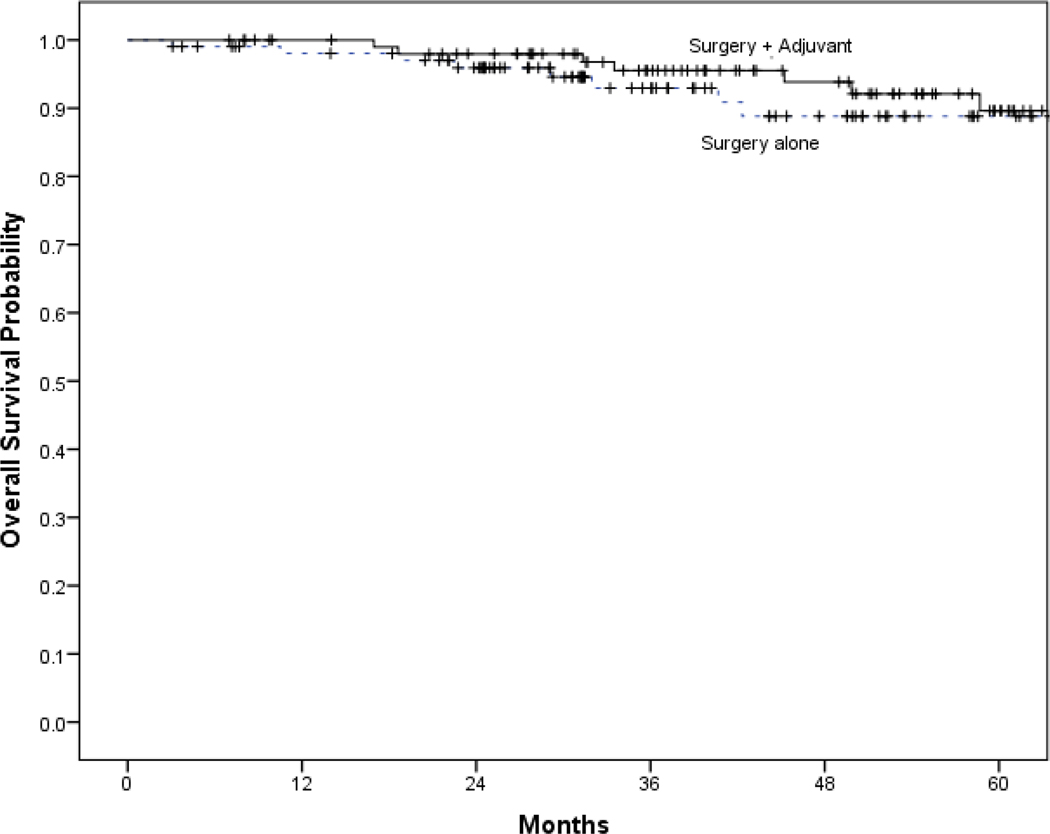

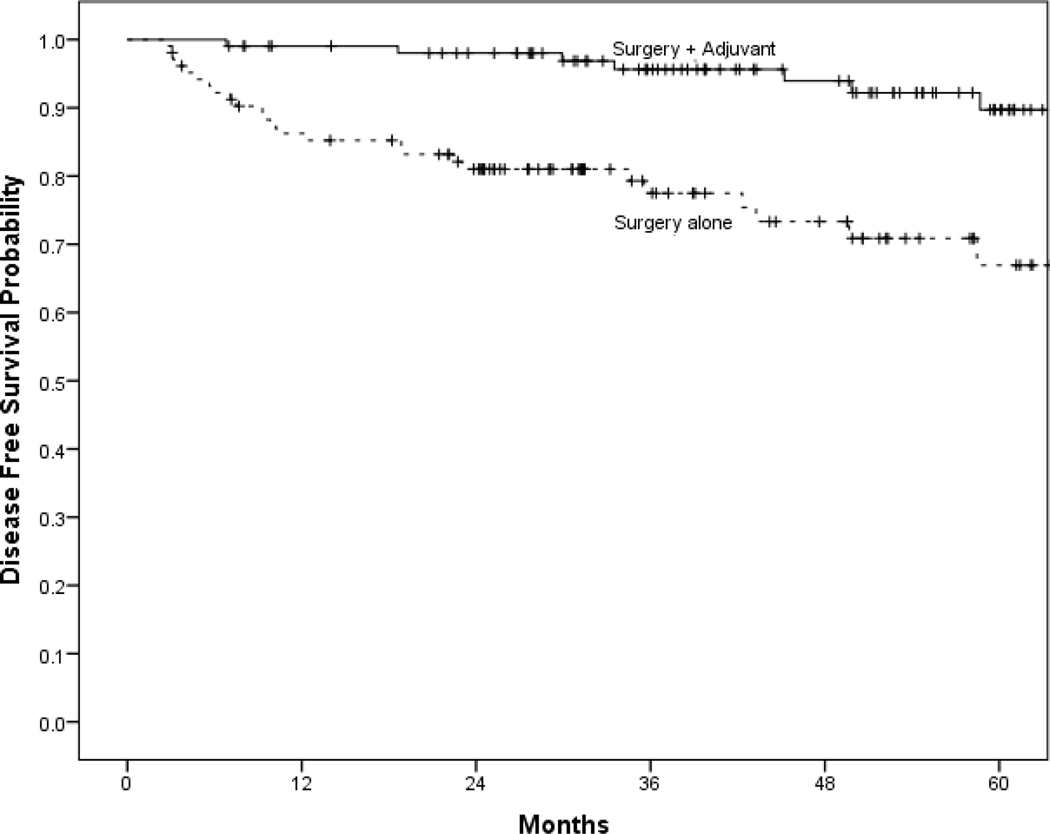

The 5-year estimated OS was 89% (95% CI: 81% - 97%) for those treated with surgery alone and 90% (95% CI: 82% - 98%) for those receiving adjuvant therapy. Distribution of recurrences in each treatment group is summarized in Table 2. Kaplan Meier estimates of OS, DSS, and DFS for each treatment group are shown in Figure 1. There was a significantly increased DFS with adjuvant therapy but no significant difference in OS or DSS. Univariable and multivariable analyses are shown in Table 3. After controlling for age and smoking status, adjuvant therapy was associated a decreased risk of recurrence (RR=0.096; 95% CI: 0.02 to 0.47). After controlling for age and smoking, adjuvant therapy was associated with decreased risk of recurrence (DFS) (HR=0.067; 95% CI: 0.01 – 0.62). There was no difference in DSS (aHR=0.22; 95% CI: 0.02 – 2.57) or OS (aHR=0.18; 95% CI: 0.01 – 2.40) with the addition of adjuvant therapy. The risk of gastrostomy tube was higher in those receiving adjuvant therapy (RR 7.3, 95% CI 2.6–20.6, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Recurrence characteristics

| Surgery Only N=105 | Surgery+Adjuvant N=105 | Percent difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Recurrence | |||

| No | 82 (78) | 102 (97) | |

| Yes | 23 (22) | 3 (3) | 19 (10 to 28) |

|

| |||

| Local | |||

| No | 96 (91) | 103 (98) | |

| Yes | 9 (9) | 2 (2) | 7 (0.9 to 13) |

| Regional | |||

| No | 90 (86) | 105 (100) | |

| Yes | 15 (14) | 0 (0) | 14 (7 to 21) |

| Distant | |||

| No | 103 (98) | 104 (99) | |

| Yes | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (−2 to 4) |

Figure 1:

Title:

Kaplan Meier estimates of survival of surgery with and without adjuvant therapy.

Legend:

Disease free survival (A), disease specific survival (B), and overall survival (C).

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of outcomes

| Recurrence RR (95% CI) |

DFS HR (95% CI) | DSS HR (95% CI) | OS HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UNIVARIABLE | ||||

| Age | 1.02 (0.96–1.09) | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 1.01 (0.93–1.10) | 1.04 (0.97–1.12) |

| Center | 0.75 (0.26–2.16) | 2.25 (0.69–7.30) | 0.67 (0.11–3.99) | 1.67 (0.39–6.97) |

| Smoking | 0.58 (0.23–1.48) | 0.80 (0.32–2.03) | 1.5 (0.25–8.98) | 1.33 (0.29–5.96) |

| ACE-27 Mild Moderate+Severe |

1.28 (0.42–3.89) 1.54 (0.30–7.87) |

0.85 (0.21–3.41) 1.86 (0.41–8.42) |

0.78 (0.08–7.12) 1.29 (0.14–11.84) |

0.66 (0.07–6.01) 1.52 (0.17–13.92) |

| Subsite (Tonsil vs. BOT) | 0.33 (0.03–3.20) | 0.50 (0.05–5.51) | 1 | 1 |

| ECE | 0.5 (0.15–1.66) | 0.63 (0.20–1.91) | 1.0 (0.14–7.10) | 0.75 (0.17–3.35) |

| PNI | 0.75 (0.17–3.35) | 1 (0.25–4.00) | 2.0 (0.18–22.06) | 2.0 (0.18–22.1) |

| LVI | 1.0 (0.29–3.45) | 0.71 (0.27–3.25) | 1.0 (0.14–7.10) | 0.75 (0.17–3.35) |

| Margins | 0.50 (0.07–3.71) | 0.62 (0.08–4.56) | 0.19 (0.02–1.50) | 0.243 (0.03–1.87) |

| Path T Stage (1 and 2 vs. 3 and 4) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Lymph node (<=4 vs. >4) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.07 (0.02–0.31) | 0.19 (0.08–0.43) |

0.48 (0.14–1.63) | 0.50 (0.19–1.29) |

| MULTIVARIABLE | ||||

| Age | 0.96 (0.86–1.07) | 0.97 (0.89–1.05) | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) | 0.99 (0.91–1.1) |

| Smoking | 1.28 (0.27–6.16) | 4.41 (0.43–45.03) | 4.22 (0.26–67.32) | 5.63 (0.35–89.67) |

| Adjuvant therapy | 0.096 (0.02–0.47) | 0.067 (0.01–0.62) | 0.22 (0.02–2.57) | 0.18 (0.01–2.4) |

Abbreviations: RR – Relative Risk; HR – Hazard ratio; CI – Confidence interval; DFS – Disease free survival; DSS – Disease specific survival; OS – Overall survival; ACE-27 – Adult Comorbidity Evaluation-27; BOT – Base of tongue; ECE – Extracapsular extension; PNI – Perineural invasion; LVI – Lymphovascular invasion; NA – Not applicable

Margins were positive in 3 patients. None of the two patients receiving adjuvant therapy for positive margins had a recurrence at 40 and 53 months follow-up, respectively. In the surgery alone group, one had a local recurrence 12 months after a positive margin. He refused re-resection of the original margin as well as any additional therapy and ultimately died of disease 17 months after the recurrence.

A recurrence occurred in 12% of patients (n=26/210) at a median of 9 months (1–59 months). Characteristics of patients with a recurrence and salvage therapy are shown in Table 4. Among patients receiving adjuvant therapy, there were 3 (3%) recurrences (2 local and 1 distant). One of the local recurrences was successfully salvaged with radiation and chemotherapy. The other two patients died of disease. Among the surgery alone patients, there were 23 (22%) recurrences. Patients with indications for recommending adjuvant therapy such as T3–4, N2+ nodal disease or extracapsular extension (ECE), had a recurrence rate of 24% compared to 20% for those with no such features. Of the 9 local recurrences, 6 were successfully salvaged, 2 died of disease and 1 did not yet have follow-up after completion of salvage chemoradiation therapy. Of the 15 regional recurrences, 3 occurred in the contralateral untreated neck in the surgery alone group. All 3 patients had primary tonsil cancers. All 3 were successfully salvaged with neck dissection with one receiving adjuvant radiation therapy. One of these patients ultimately died of distant metastasis but had no further regional recurrence.

Table 4.

Characteristics and outcomes of patients with a recurrence

| Patient | Primary Site | Treatment | T-stage | Node number | LVI | PNI | ECE | Margins | Recurrence Site | Salvage | Status | OS (months) | DFS (months) | Follow-up After Recurrence (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tonsil | S | 1 | 0 | − | − | NA | − | Local | S+R | ANED | 95 | 59 | 36 |

| 2 | BOT | S | 1 | 5 | + | − | + | − | Regional | S | ANED | 54 | 4 | 50 |

| 3 | BOT | S | 4a | 1 | − | − | − | − | Local | R+C | ANED | 45 | 10 | 35 |

| 4 | BOT | S | 1 | 1 | − | − | − | − | Local Regional |

S | ANED | 44 | 43 | 1 |

| 5 | Tonsil | S | 3 | 0 | − | − | NA | − | aRegional | S | ANED | 30 | 23 | 7 |

| 6 | Tonsil | S | 1 | 1 | − | − | − | − | Regional | S+R | ANED | 25 | 1 | 24 |

| 7 | Tonsil | S | 2 | 8 | + | + | + | − | Regional | R | ANED | 21 | 6 | 15 |

| 8 | Tonsil | S | 2 | 2 | − | − | − | − | aRegional | S+R | ANED | 59 | 8 | 51 |

| 9 | Tonsil | S | 2 | 0 | − | − | NA | − | Regional | S+R+C | ANED | 88 | 9 | 79 |

| 10 | BOT | S | 2 | 0 | − | − | NA | − | Local | S+R+C | ANED | 89 | 35 | 54 |

| 11 | Tonsil | S | 2 | 0 | − | − | NA | − | Local | S+R | ANED | 40 | 3 | 37 |

| 12 | BOT | S | 1 | 1 | − | − | − | − | Regional | S | ANED | 37 | 23 | 14 |

| 13 | Tonsil | S | 2 | 2 | − | − | + | − | Regional | S+R+C | ANED | 36 | 4 | 32 |

| 14 | Tonsil | S | 1 | 0 | − | − | NA | − | Local | R+C | ANED | 67 | 10 | 57 |

| 15 | Tonsil | S | 2 | 3 | − | + | + | − | Regional | R | AWD | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| 16 | Tonsil | S | 3 | 1 | − | − | − | − | Local | R+C | AWD | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| 17 | BOT | S | 4a | 3 | − | − | + | − | Regional | Unknown | AWD | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| 18 | BOT | S | 3 | 3 | + | + | + | + | Local | Refused | DOD | 29 | 12 | 17 |

| 19 | BOT | S | 2 | 5 | − | − | + | − | Local | S | DOD | 23 | 6 | 17 |

| 20 | Tonsil | S | 1 | 1 | − | − | − | − | Regional | R+C | DOD | 11 | 3 | 8 |

| 21 | Tonsil | S | 1 | 1 | − | − | + | − | bRegional | S+R | DOD | 32 | 9 | 23 |

| 22 | Tonsil | S | 4a | 4 | + | + | + | − |

aRegional Distant |

S+C | DOD | 84 | 36 | 48 |

| 23 | Tonsil | S | 2 | 1 | + | − | − | − | Regional Distant |

S+R | DOD | 41 | 19 | 22 |

| 24 | Tonsil | S+R | 2 | 1 | − | − | − | − | Local | C | DOD | 17 | 7 | 10 |

| 25 | BOT | S+R+C | 2 | 1 | − | − | + | − | Local | R+C | ANED | 14 | 6 | 8 |

| 26 | BOT | S+R+C | 4a | 13 | + | − | + | − | Distant | C | DOD | 31 | 30 | 1 |

Regional recurrence was in the contralateral, untreated neck. Number 22 ultimately died of distant metastatic disease without further recurrence of regional disease after contralateral neck dissection.

Patient also had metastatic breast cancer in revision neck dissection specimen, therefore, it is not entirely known if patient died of recurrent oropharyngeal carcinoma or metastatic breast cancer.

Abbreviations: LVI – Lymphovascular invasion; PNI – Perineural invasion; ECE – extracapsular extension; OS – Overall survival; DFS – Disease free survival; S – Surgery; R – Radiation; C – Chemotherapy; BOT – Base of tongue; NA – Not applicable; ANED – Alive no evidence of disease; AWD – Alive with disease; DOD – Dead of disease

Of those 6 surgery alone patients that died of disease, 2 had distant metastases, 1 had concomitant breast cancer metastases in cervical lymph nodes and 1 had positive surgical margins but refused re-resection, adjuvant therapy and salvage therapy. The remaining 2 patients died from locoregional disease.

Discussion:

Our multi-institutional matched analysis for transorally resected HPV-related OPSCCa showed that addition of adjuvant therapy in surgical patients was associated with lower risk of disease recurrence. Although adjuvant therapy lowered the risk of local and regional recurrence, there was no difference in distant spread. Distant metastasis is a major mode of failure in HPV-related OPSCCa.11,14,15 The risk of distant metastasis did not seem to be determined by the primary treatment and will likely continue to be a source of treatment failure.

There was a significantly improved DFS with the addition of adjuvant therapy, but no observed improvement in DSS or OS. This is likely secondary to the success of available surgery, radiation and chemotherapy as salvage modalities.

As the treatment of HPV-related OPSCCa moves toward deintensification, it is prudent to understand the reasons we add therapy and outcomes of individual treatment modalities become critically important. This is particularly pertinent when we consider findings in this study and other series,16 that the addition of postoperative adjuvant therapy is associated with significant increases in swallowing-related morbidity. There are very few reports specifically analyzing the oncologic outcomes and treatment failures of patients with HPV-related OPSCCa treated with definitive surgery alone. Grant et al. evaluated 69 patients treated with TLM with or without neck dissection and found excellent disease control and low morbidity with primary transoral surgery. They did not specifically address HPV-related disease.17 Funk et al. evaluated 25 patients undergoing surgery alone with intermediate to high-risk features that would have qualified them for adjuvant therapy.18 They found a 20% recurrence rate at a median of 4.8 months after surgery. Two of the 5 patients that recurred were in the contralateral, untreated neck. All 5 patients were successfully salvaged with multimodality therapy and are alive with no evidence of disease at 17–23 months after salvage treatment. In the current study, 3 patients recurred in the contralateral neck and all were successfully salvaged at the nodal basin.

The amount of adjuvant therapy, mainly the addition of chemotherapy, in patients undergoing transoral surgery also remains controversial. The presence of ECE and positive surgical margins are considered high-risk features and indicators for adjuvant chemoradiation therapy as recommended by the NCCN.19 In a critical appraisal of the literature used to establish the NCCN guidelines, Sinha et al. concluded the guidelines to recommend adjuvant chemotherapy in addition to radiation therapy is not based on high-level evidence and its role remains unknown in surgically treated HPV-related OPSCCa.16 This conclusion is supported by multiple studies that have not identified ECE as a risk factor for survival in surgically managed, HPV-related OPSCC.10,20–24 The role of tobacco exposure is also not well understood in HPV-positive compared to HPV-negative disease. These controversies are likely a product of the improved prognosis of patients with HPV-related OPSCCa compared to those with HPV-negative disease.

As a result, there is currently no consensus on the optimum management of HPV-related OPSCCa. This is, in part, because prognostic features are not consistently agreed upon. Studies have demonstrated that the prognosis and related factors for HPV-related OPSCCa differ from HPV-negative disease and that conventional prognostic features do not predict treatment outcomes.10,11,15,20,21,25 Most recently, Kaczmar et al. described 114 patients treated with TORS and did not identify conventional poor prognostic variables as predictors of treatment failure.15 Sinha et al. described that greater than 4 metastatic lymph nodes, and not ECE or N-classification, correlated with poorer prognosis.10 On the other hand, Funk et al. concluded that patients with intermediate and high-risk features should receive adjuvant therapy, despite all of their patients undergoing successful salvage.18

Patients treated with surgery and offered adjuvant therapy based on multidisciplinary recommendations have excellent oncologic outcomes. With relatively low recurrence rates of 9% locally and 14% regionally for patients undergoing surgery alone, our results demonstrate that locoregional recurrence in patients who have only undergoing surgical therapy does not portend a worse prognosis for survival. Patients that are offered or choose close observation after surgery instead of adjuvant therapy have a similar OS despite a higher risk of locoregional recurrence. This may be secondary to having potentially all modalities available for locoregional salvage. On the other hand, this may be limited by sample size, in which a larger sample may show significant differences in survival between the two groups. Therefore, future trials could be designed in which properly selected patients receive surgery alone with close observation, utilizing radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or further surgery for recurrent disease. This could potentially eliminate adjuvant therapy in the majority of this patient population and thus decrease the risk of toxicities from these treatments.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it is limited by the retrospective nature of the study design and data collection. Second, the low number of recurrence events makes it difficult to compare outcomes between groups. It is also limited by the random nature of the matching process. Despite nearly all of the surgery alone patients being included in the analysis, only 105 of 306 patients who received adjuvant therapy were included although such exclusion was essential to ensure a balance of known, important confounders. We cannot definitively apply these results to the entire population, as many recurrence events were not included secondary to the matching process. Lastly, several variables that may have prognostic implications could not be evaluated such as tumor volume, extent of radiation fields, and radiation dose.

Conclusions:

Transoral surgery continues to play a role in the treatment of HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma, with a majority avoiding recurrence following surgery alone. Secondary to lower locoregional recurrence, adjuvant therapy associates with improved DFS, without significant improvement in OS or DSS. As we move forward in the management of HPV-related OPSCCa, we must weigh carefully the morbidity and costs of our treatments and the reasons to add additional therapy. Trials comparing surgery with adjuvant therapy to surgery alone with close follow-up would be needed to study the true effects of adjuvant therapy. With relatively low local and regional recurrence and fairly successful salvage after surgery alone, adjuvant therapy could potentially be spared in a select subset of patients and reserved for recurrent disease, given the similar OS between the two groups.

SYNOPSIS:

Transoral surgery is an effective approach to treat HPV-related oropharyngeal carcinoma.

The addition of adjuvant therapy appears to decrease the risk of recurrence and improve disease free survival.

Acknowledgements:

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Presentation:

Oral presentation on July 17, 2016 at the AHNS 9th International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer, Seattle, WA.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest. There was no funding for this research. This manuscript has not been published or presented elsewhere.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J. Clin. Oncol. Nov 10 2011;29(32):4294–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfister DG, Spencer S, Brizel DM, et al. Head and Neck Cancers, Version 1.2015. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. Jul 2015;13(7):847–855; quiz 856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Almeida JR, Byrd JK, Wu R, et al. A systematic review of transoral robotic surgery and radiotherapy for early oropharynx cancer: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. Sep 2014;124(9):2096–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore EJ, Olsen KD, Kasperbauer JL. Transoral robotic surgery for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective study of feasibility and functional outcomes. Laryngoscope. Nov 2009;119(11):2156–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haughey BH, Hinni ML, Salassa JR, et al. Transoral laser microsurgery as primary treatment for advanced-stage oropharyngeal cancer: a United States multicenter study. Head Neck. Dec 2011;33(12):1683–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dziegielewski PT, Teknos TN, Durmus K, et al. Transoral robotic surgery for oropharyngeal cancer: long-term quality of life and functional outcomes. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Nov 2013;139(11):1099–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen MA, Weinstein GS, O’Malley BW Jr., Feldman M, Quon H Transoral robotic surgery and human papillomavirus status: Oncologic results. Head Neck. Apr 2011;33(4):573–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Almeida JR, Li R, Magnuson JS, et al. Oncologic Outcomes After Transoral Robotic Surgery: A Multi-institutional Study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Dec 2015;141(12):1043–1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edge SB, American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinha P, Kallogjeri D, Gay H, et al. High metastatic node number, not extracapsular spread or N-classification is a node-related prognosticator in transorally-resected, neck-dissected p16-positive oropharynx cancer. Oral Oncol. May 2015;51(5):514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haughey BH, Sinha P. Prognostic factors and survival unique to surgically treated p16+ oropharyngeal cancer. Laryngoscope. Sep 2012;122 Suppl 2:S13–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings P MB. Analysis of matched cohort data. The Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):274–281. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardin JW HJ. Generalized linear models and extensions. College Station, TX: Stata Press. 2001:404–415. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang SH, Perez-Ordonez B, Weinreb I, et al. Natural course of distant metastases following radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. Jan 2013;49(1):79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaczmar JM, Tan KS, Heitjan DF, et al. HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer: Risk factors for treatment failure in patients managed with primary transoral robotic surgery. Head Neck. Jan 2016;38(1):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinha P, Piccirillo JF, Kallogjeri D, Spitznagel EL, Haughey BH. The role of postoperative chemoradiation for oropharynx carcinoma: a critical appraisal of the published literature and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. Cancer. Jun 1 2015;121(11):1747–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant DG, Hinni ML, Salassa JR, Perry WC, Hayden RE, Casler JD. Oropharyngeal cancer: a case for single modality treatment with transoral laser microsurgery. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. Dec 2009;135(12):1225–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Funk RK, Moore EJ, Garcia JJ, et al. Risk factors for locoregional relapse after transoral robotic surgery for human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. Apr 2016;38(S1):E1674–E1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(U.S.) NCCN. Head and Neck Cancers (Version 1.2015). https://http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/head-and-neck.pdf. Accessed 5/1/2016.

- 20.Maxwell JH, Ferris RL, Gooding W, et al. Extracapsular spread in head and neck carcinoma: impact of site and human papillomavirus status. Cancer. Sep 15 2013;119(18):3302–3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klozar J, Koslabova E, Kratochvil V, Salakova M, Tachezy R. Nodal status is not a prognostic factor in patients with HPV-positive oral/oropharyngeal tumors. J. Surg. Oncol. May 2013;107(6):625–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iyer NG, Dogan S, Palmer F, et al. Detailed Analysis of Clinicopathologic Factors Demonstrate Distinct Difference in Outcome and Prognostic Factors Between Surgically Treated HPV-Positive and Negative Oropharyngeal Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. Dec 2015;22(13):4411–4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar B, Cipolla MJ, Old MO, et al. Surgical management of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: Survival and functional outcomes. Head Neck. Apr 2016;38 Suppl 1:E1794–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkie MD, Upile NS, Lau AS, et al. Transoral laser microsurgery for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A paradigm shift in therapeutic approach. Head Neck. Apr 4 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sinha P, Lewis JS Jr., Piccirillo JF, Kallogjeri D, Haughey BH. Extracapsular spread and adjuvant therapy in human papillomavirus-related, p16-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. Jul 15 2012;118(14):3519–3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]