Abstract

Introduction

Despite increases in e-cigarette sales restrictions, support for sales restrictions and perceived impact on young adult use are unclear.

Aims and Methods

We analyzed February-May 2020 data from a longitudinal study of 2159 young adults (ages 18–34; Mage = 24.75 ± 4.71; n = 550 past 30-day e-cigarette users) in six metropolitan areas (Atlanta, Boston, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, San Diego, and Seattle). We examined support for e-cigarette sales restrictions and—among e-cigarette users—perceived impact of flavored vape product and all vape product sales restrictions on e-cigarette and cigarette use (and potential correlates; ie, e-cigarette/tobacco use, use-related symptoms/health concerns).

Results

About 24.2% of e-cigarette users (and 57.6% of nonusers) supported (strongly/somewhat) sales restrictions on flavored vape products; 15.1% of e-cigarette users (45.1% of nonusers) supported complete vape product sales restrictions. If restricted to tobacco flavors, 39.1% of e-cigarette users reported being likely (very/somewhat) to continue using e-cigarettes (30.5% not at all likely); 33.2% were likely to switch to cigarettes (45.5% not at all). Considering complete vape product sales restrictions, equal numbers (~39%) were likely versus not at all likely to switch to cigarettes. Greater policy support correlated with being e-cigarette nonusers (adjusted R2 [aR2] = .210); among users, correlates included fewer days of use and greater symptoms and health concerns (aR2 = .393). If such restrictions were implemented, those less likely to report continuing to vape or switching to cigarettes used e-cigarettes on fewer days, were never smokers, and indicated greater health concern (aR2 = .361).

Conclusions

While lower-risk users may be more positively impacted by such policies, other young adult user subgroups may not experience benefit.

Implications

Young adult e-cigarette users indicate low support for e-cigarette sales restrictions (both for flavored products and complete restrictions). Moreover, if vape product sales were restricted to tobacco flavors, 39.1% of users reported being likely to continue using e-cigarettes but 33.2% were likely to switch to cigarettes. If vape product sales were entirely restricted, e-cigarette users were equally likely to switch to cigarettes versus not (~40%). Those most likely to report positive impact of such policies being implemented were less frequent users, never smokers, and those with greater e-cigarette-related health concerns. This research should be considered in future tobacco control initiatives.

Introduction

E-cigarette use (or vaping) has drastically increased domestically and globally over the last 12 years, particularly among youth and young adults.1–3 In 2020, 19.6% of US high school students reported past-month vaping,2 with US young adults (ages 18–24) showing increases in vaping from 5.2% in 2014 to 9.3% in 2019.3 E-cigarettes contain nicotine and chemicals which may increase risk of various diseases, contribute to detrimental neurocognitive effects among youth,4,5 and lead to conventional cigarette use.6–9 Additionally, deaths and negative symptoms (eg, cough, dizziness, irritated throat)10 because of e-cigarette/vaping-associated lung injury (EVALI)11 made addressing e-cigarette use among young people a priority.10Although EVALI is largely linked to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing e-cigarette products, the contribution of other chemicals from non-THC-containing products is not fully understood.

Some state and local governments have taken steps to reduce e-cigarette use among young people.12,13 One key consideration is flavors, which are a major reason for e-cigarette use in this group14–16; 82% of young adults report using nontobacco e-cigarette flavors (vs. 70% of adults).16,17 Massachusetts was the first state to restrict the sale of all flavored tobacco products (effective November 2019). As of March 2021, at least five states and 300 localities restricted the sale of flavored e-cigarettes (some included menthol),18 and laws were more comprehensive than federal restrictions on flavored cartridge-based products (excluding menthol).19

Recent progress toward implementing sales restrictions on e-cigarettes—specifically the sale of flavored products or vape product sales all together—has occurred in the context of limited research on policy support and potential impact on use behaviors among young adult e-cigarette users. Understanding public opinion and potential policy impact is critical to inform policy.20 Drawing from prior literature regarding the potential impact of restrictions on menthol tobacco products,21–25 restricting flavors in e-cigarettes alone could increase cessation and reduce initiation; however, some research assessing the impact of such restrictions in hypothetical scenarios suggests the possibility of unintended consequences, such as prompting e-cigarette users to switch to cigarette smoking and youth to initiate use of conventional tobacco products.26,27 However, it is important to note that the likelihood and population-level impact of these potential unintended consequences are unclear. Such policy implications should be considered within a dynamic multilevel framework, such as the Socioecological Model,28 which highlights how individual-level factors (eg, EVALI-related symptoms and health concerns, e-cigarette/other tobacco use characteristics), interpersonal factors (eg, social/media influences), and macro-level factors (eg, policy) interact.

In a 2016 survey, 47.3% of US adults reported favorable attitudes toward restricting flavors in all tobacco products, with never and former users29 and parents (75%)29,30 reporting the most favorable attitudes. However, a survey of 18- to 34-year-old former tobacco users in San Francisco found that only 8.1% supported the city’s sales restriction on flavored tobacco and perceptions varied by product (eg, 42% opposed restrictions on flavored e-cigarettes).31 This study also indicated that smokers, e-cigarette users, and those who did not believe in the harms associated with e-cigarettes were typically less supportive of such policies.32 In previous research, being a nonsmoker and sociodemographics (eg, being older, female) were related to more support for tobacco control policies.33 Among smokers, readiness to quit has been associated with greater policy support.33 Thus, current users may hold more negative opinions of e-cigarette sales restrictions. In particular, users who have experienced EVALI symptoms and/or are concerned about health consequences of e-cigarette use may be more motivated to reduce or quit and, therefore, express greater support for sales restrictions.

A major gap in the research is how young adults respond to such e-cigarette policies, such as considering quitting e-cigarettes (and other tobacco) altogether or switching to conventional cigarettes. Results from the San Francisco survey suggest that the use prevalence of flavored tobacco overall and e-cigarettes specifically decreased from ~83% to ~73% and from ~57% to ~47%, respectively; cigar use prevalence decreased as well.31 However, cigarette smoking increased among participants aged 18–24 but not older adults (aged 25–34).31 Notably, 65% perceived enforcement to be limited, and most users reported obtaining flavored tobacco products in multiple ways despite the restrictions.31 In research examining menthol restrictions, increases in quitting among menthol smokers and reduced overall smoking was indicated in discrete choice experiments,21,26 population-based surveys in Canada,22–24 and simulation models34; however, other studies suggested likely increases in the use of alternative flavored tobacco products (eg, e-cigarettes, cigars).22,24–26 An experimental study26 found that e-cigarette flavor sales restrictions (other than menthol) would reduce e-cigarette use but increase cigarette smoking, and comprehensive restrictions on menthol cigarettes and flavored e-cigarettes might not only decrease e-cigarette use and reduce menthol cigarette smoking but also increase non-menthol cigarette use.

To contribute to the evidence base to inform such policies, the current study examined e-cigarette sales restriction policy support and potential impact on e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking among e-cigarette users. In addition, analyses examined key correlates including sociodemographics, e-cigarette, and other tobacco product use characteristics, negative health (EVALI) symptoms, e-cigarette-related health concerns, and social/media influences. Within this context, we also examined correlates of EVALI symptoms and e-cigarette-related health concerns among e-cigarette users.

Methods

Study Design

We analyzed survey data of 3006 young adults (aged 18–34) from six metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs: Atlanta, Boston, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, San Diego, and Seattle) in a 2-year, 5-wave longitudinal cohort study, the Vape shop Advertising, Place characteristics and Effects Surveillance (VAPES). These MSAs were selected for their variation in state policies regarding tobacco control (eg, strongest in California and Massachusetts; weakest in Georgia and Oklahoma).12,13 At the time of this survey, Massachusetts had restricted e-cigarette flavors (effective November 2019), which occurred after an emergency restriction on all e-cigarette sales in Massachusetts (September-November 2019) as a result of the EVALI outbreak. (Washington implemented a brief restriction on flavored e-cigarettes from October 2019-February 2020.) These MSAs also differ in their retail markets for recreational marijuana35 (relevant given high co-use of e-cigarettes, cigarettes, and marijuana36,37 and the implications of marijuana in EVALI).38 This study, detailed elsewhere,39 was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

Participants and Recruitment

Potential participants were recruited via social media. Eligibility criteria were: (1) 18–34 years old, (2) residing in zip codes of the six MSAs, and (3) English speaking. Purposive sampling was used to ensure sufficient proportions of the sample representing e-cigarette and cigarette users (roughly 1/3 each), sexes, and racial/ethnic minorities. Ads posted on Facebook and Reddit targeted individuals: (1) by using indicators reflecting those of eligible age and geographical locations (within 15 miles of their respective MSAs); (2) by identifying activities/interests of young adults (eg, targeting those who followed, “liked,” or were group members of pages related to sports/athletics, arts/entertainment, technology, fashion), as well as tobacco-related interests (eg, Marlboro, Juul, Swisher Sweets); and (3) by posting ads including images of diverse young adults socializing, young adult professionals, etc. Ad tag lines included “Help researchers learn what young adults in your city think about tobacco products!,” “Communities of young adults: Researchers want to know your world!,” or “Smok’n? Vape’n? Researchers want to know your thoughts!”

Once potential participants clicked on an ad, they were directed to a webpage with a study description and consent form. Once individuals consented, they completed an eligibility screener, which also assessed sex, race, ethnicity, and past-month e-cigarette and cigarette use (to facilitate reaching recruitment targets of subgroups in each MSA). Enrollment varied for each MSA, and subgroup enrollment was capped by MSA. Eligible individuals allowed to advance were then routed to complete the online baseline (Wave 1) survey (via SurveyGizmo, now Alchemer). Upon survey completion, participants were notified that, 7 days after completing the baseline survey, they would be asked to confirm their participation by clicking a “confirm” button in an email sent to them that reiterated study procedures and timeline. (During this week, we scrutinize data provided to ensure logical response options, identify potentially fraudulent activity, etc.) Based on prior research,40 we took several measures to prevent fraudulent responses, including (1) concealing eligibility criteria and (2) using IP addresses to block duplicate screening attempts. Additionally, during this initial 7-day period, we scrutinized data provided to identify potentially fraudulent activity (eg, duplicate IP addresses or contact information) or other suspicious response activity (eg, multiple survey responses in a brief period, illogical response patterns). Duplicate records were inactivated and deemed to be invalid. We documented a fraud rate of less than 1%. Once participants clicked “confirm,” they were officially enrolled into the study and emailed their first incentive ($10 Amazon e-gift card).

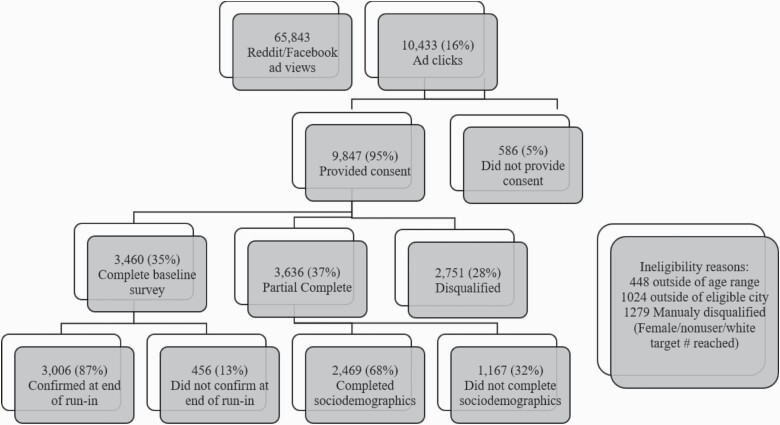

The participant flowchart is included in Figure 1. The duration of the recruitment period ranged from 87 to 104 days across the six MSAs (<90 days for Atlanta, Boston, and Minneapolis; >90 days for Seattle, San Diego, and Oklahoma City). Overall, 65 843 Facebook and Reddit users viewed study ads, and 10 433 clicked on ads. Of the 9847 who consented, 2751 (28%) were not allowed to advance because they were either: (1) ineligible (n = 1427) and/or (2) excluded in order to reach subgroup target enrollment (ie, we had already reached the recruitment targets in that MSA for that subgroup, mostly women, Whites, and nonusers of e-cigarettes or cigarettes, n = 1279).39 Of the 7096 consented participants who were eligible and allowed to advance to the baseline survey, 3460 (48.8%) completed the baseline survey, and 3636 (51.2%) partially completed the survey (deemed ineligible for the remainder of the study). Of the 3460 who completed the baseline survey, 3006 (87%) confirmed participation at the 7-day follow-up. Confirmation response rates varied across the six MSAs from 83% (Seattle) to 91% (Boston). Incomplete survey respondents differed from completers (ie, younger, more likely male, Black or other race, and past 30-day cigarette and e-cigarette users); non-confirmers also differed (ie, more likely Black or other race, and cigarette and e-cigarette users).39

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment flowchart.

This study uses data from Wave 4 (Spring 2020), which included 2159 participants with complete data (71.8% of the baseline sample, N = 3006; n = 550 [25.5%] e-cigarette users).

Measures

Sociodemographics

Participants reported their age, sex, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, highest level of educational attainment, employment status, and relationship status.

Tobacco and Marijuana Use

Participants were asked, “In the past 30 days, on how many days did you use: e-cigarettes? cigarettes? hookah/waterpipe? little cigars/cigarillos? large cigars? smokeless tobacco? marijuana?” Each assessment was presented alongside photos providing examples/prototypes of the respective product.41 These use variables were operationalized as dichotomous variables (yes vs. no) for each product.41 Among lifetime e-cigarette users, we assessed age at first use; among past-month users, we assessed whether they typically used an open or closed tank system (given literature suggesting that using closed pod systems that contain nicotine salts may be associated with increased respiratory symptoms).42,43 We also created a variable for former cigarette use (ie, no past-month cigarette smoking but reported: (1) smoking ≥100 cigarettes in their lifetime at baseline or (2) current smoking at waves 1, 2, or 3). Finally, past-month marijuana users were asked how they use marijuana most of the time, categorized as: smoked via joint/bowl, smoked via pipe/bong, digested, vaporized, and other (eg, tinctures, dabs).

Health Effects and Concerns

E-cigarette users were asked, “Please indicate the extent to which you experienced any of the following symptoms during or shortly after vaping (or using e-cigarettes)?” cough, dry or irritated mouth or throat, dizziness or lightheadedness, headache or migraine, shakiness or jitters, shortness of breath, change in or loss of taste, nausea, tightness in chest, congestion, sweating or cold sweats, or other.10 Response options were 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = always (Cronbach’s alpha = .88). They were also asked, “How concerned are you about the potential negative health effects of vaping?” Response options were 0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = somewhat, and 3 = very.44

Social/Media Influences

All participants were asked, “In the past year, how often have you heard or seen news stories regarding any negative health affects related to vaping?” E-cigarette users were also asked, “In the past year, how often has: (1) a friend or family member expressed concerns about your vaping (use of e-cigarettes)? and (2) a friend or family member shared with you any news stories regarding any negative health effects related to vaping (or using e-cigarettes)?” 44 Response options were 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = always.44 To create one variable for social/media influences for e-cigarette users, these items were summarized by calculating a mean score.

Policy Support

All participants were asked, “Legislation to ban the sale of flavored vape products has been approved in some cities and states. To what extent do you support or oppose a policy to ban the sale of flavored vape products in your state? To what extent do you support or oppose a policy to ban the sale of any vape products in your state?” 29,31 Response options were 0 = strongly oppose, 1 = somewhat oppose, 2 = don’t know/neutral, 3 = somewhat support, and 4 = strongly support.29,31 We created an overall policy support variable by summarizing the two items as a mean score (Kappa = .53).

Perceived Impact

E-cigarette users were asked: (1) “If the government restricted vape products to tobacco flavors only, how likely would you be to continue to vape or use e-cigarettes?”; (2) “If the government restricted vape products to tobacco flavors only, how likely would you be to switch to traditional cigarettes?”; and (3) “If the government banned all vape product sales, how likely would you be to switch to traditional cigarettes?” 31 Response options were 0 = very, 1 = somewhat, 2 = a little, and 3 = not at all.31 We created an overall positive policy impact variable by summarizing the three items as a mean score (Cronbach’s alpha = .66). For example, if a participant indicated “3 = not at all” to all three of the items, their score would be a 3 (ie, high positive policy impact), indicating “0 = very” to all 3 would yield a score of 0 (ie, low positive policy impact).

Data Analysis

Chi-square tests and t-tests were used to explore differences across e-cigarette users and nonusers. We also explored correlates of EVALI symptoms and health concern. We then addressed our two primary outcomes: (1) e-cigarette policy support and (2) positive impact of e-cigarette policies. Each outcome was explored among e-cigarette users only, and e-cigarette policy support was also examined among all participants (controlling for e-cigarette use status). For each of our primary outcomes, we conducted multivariable linear regression modeling to assess the effects of predictors of interest (ie, e-cigarette use characteristics, other tobacco use, EVALI symptoms, health concerns, social/media influences), accounting for MSA and sociodemographics. Regression analyses were also conducted using multilevel modeling to account for the hierarchical structure of the data (ie, young adults at the individual level nested in MSA)45; all intra-class correlations ranged from 0 to .01, and findings were not significantly different. Note that we did not include all sociodemographics in multivariable models because of multicollinearity (ie, age correlated with education, employment, and relationship status so only age included). All analyses were conducted using SPSS v26. Alpha was set at .05.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 provides participant characteristics and bivariate comparisons between past-month e-cigarette users versus nonusers. Among e-cigarette users, the most commonly reported EVALI symptom was cough (74.2% reporting at least rarely), followed by dry or irritated mouth or throat (64.8%), dizziness/lightheadedness (58.5%), and shortness of breath (46.2%). Multivariable regression (Table 2) indicated that greater EVALI symptoms correlated with residing in Boston relative to Atlanta (p = .010) or San Diego (.027), older age (p = .008), being Black (p = .001), being younger age at first e-cigarette use (p < .001), and past-month other tobacco use (p < .001; adjusted R2 [aR2] = .166).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics and Bivariate Comparisons Among Past 30-Day E-Cigarette Users and Nonusers

| Total | Users | Nonusers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 2159 (100%) | N = 550 (25.5%) | N = 1609 (74.5%) | ||

| Variables | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | N (%) or M (SD) | p |

| MSA, N (%) | ||||

| Atlanta | 432 (20.9) | 92 (17.6) | 340 (22.0) | .001 |

| Boston | 421 (20.4) | 87 (16.6) | 334 (21.7) | |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul | 365 (17.7) | 105 (20.1) | 260 (16.9) | |

| Oklahoma City | 126 (6.1) | 28 (5.4) | 98 (6.4) | |

| San Diego | 313 (15.2) | 90 (17.2) | 223 (14.5) | |

| Seattle | 306 (14.8) | 100 (19.1) | 206 (13.4) | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age, M (SD) | 24.75 (4.71) | 24.86 (4.65) | 24.45 (4.88) | .024 |

| Male, N (%) | 857 (39.7) | 242 (44.0) | 615 (38.2) | .058 |

| Sexual minority, N (%) | 666 (30.8) | 194 (35.3) | 472 (29.3) | .009 |

| Race, N (%) | ||||

| White | 1544 (71.5) | 396 (72.0) | 1148 (71.3) | — |

| Black | 114 (5.3) | 22 (4.0) | 92 (5.7) | — |

| Asian | 284 (13.2) | 62 (11.3) | 222 (13.8) | — |

| Other | 216 (10.0) | 70 (12.7) | 146 (9.1) | — |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 236 (10.9) | 65 (11.8) | 171 (10.6) | .443 |

| Education ≥bachelor’s degree, N (%) | 1672 (77.4) | 368 (66.9) | 1304 (81.0) | <.001 |

| Employment, N (%) | <.001 | |||

| Student | 593 (27.5) | 122 (22.2) | 471 (29.3) | — |

| Unemployed | 177 (8.2) | 46 (8.4) | 131 (8.1) | — |

| Full time | 865 (40.1) | 204 (37.1) | 661 (41.1) | — |

| Part time | 523 (24.2) | 178 (32.4) | 345 (21.4) | — |

| Married/living with partner, N (%) | 809 (37.5) | 222 (40.4) | 587 (36.5) | .082 |

| E-cigarette use characteristicsa | ||||

| Age at first use, M (SD) | — | 20.23 (4.39) | — | — |

| Number of days used, M (SD) | — | 16.92 (12.09) | — | — |

| Open (vs. closed) system/tank use, N (%) | — | 281 (51.1) | — | — |

| Other tobacco use | ||||

| Past 30-day cigarette user, N (%) | 417 (19.3) | 252 (45.8) | 165 (10.3) | <.001 |

| Past 30-day other tobacco user, N (%) | 331 (15.3) | 179 (32.5) | 152 (9.4) | <.001 |

| Former cigarette smoker, N (%) | 361 (16.7) | 162 (29.5) | 199 (12.4) | <.001 |

| Past 30-day marijuana user, N (%)b | 793 (36.7) | 315 (57.3) | 478 (29.7) | <.001 |

| EVALI symptoms, M (SD)a,c | — | 0.69 (0.63) | — | — |

| Health concern, M (SD)d | 1.80 (1.02) | 1.37 (1.03) | 1.95 (0.97) | <.001 |

| Social/media influencesc | — | 1.58 (0.80) | — | — |

| Heard/seen news on negative health effects | 2.31 (0.88) | 2.29 (0.89) | 2.32 (0.88) | .607 |

| Friend/family expressed concernsa | — | 1.16 (1.07) | — | — |

| Friend/family shared news on negative health effectsa | — | 1.27 (1.10) | — | — |

| Policy support, M (SD)e | — | 1.11 (1.20) | — | — |

| Flavored vape product sales restrictions | 2.25 (1.45) | 1.26 (1.36) | 2.60 (1.31) | <.001 |

| All vape products sales restrictions | 1.89 (1.46) | 0.95 (1.23) | 2.23 (1.38) | <.001 |

| Positive policy impact, M (SD)a,f | — | 1.83 (0.86) | — | — |

| If restricted to tobacco flavors, likely to quit vs. continue vaping | — | 1.78 (1.03) | — | — |

| If restricted to tobacco flavors, likely to quit vs. switch to cigarettes | — | 1.97 (1.13) | — | — |

| If all sales prohibited, likely to quit vs. switch to cigarettes | — | 1.75 (1.21) | — | — |

MSA, metropolitan statistical areas; EVALI, e-cigarette/vaping-associated lung injury. p-values indicate omnibus tests (per t-tests and chi-square).

Italic p-values indicate significance (ie, p < .05).

aAmong past 30-day e-cigarette users.

bParticipants’ reports of their most frequent way to consumer marijuana: among all participants: 39.9% smoked, 20.9% digest, 19.4% vaped, 15.7% pipe/bong, 4.1% other; among e-cigarette users: 39.3% smoked, 19.7% digest, 19.7% vaped, 16.7% pipe/bong, and 4.6% other.

cOn a scale of 0 = Never, 1 = Rarely, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Often, 4 = Always.

dOn a scale of 0 = Not at all, 1 = A little, 2 = Somewhat, 3= Very.

eOn a scale of 0 = Strongly oppose, 1 = Somewhat oppose, 2 = Neutral/Don’t know, 3 = Somewhat support, 4 = Strongly support.

fOn a scale of 0 = Very, 1 = Somewhat, 2 = A little, 3 = Not at all.

Table 2.

Multivariate Regression Examining Correlates of EVALI Symptoms, Health Concern, Policy Support, and Policy Impact Among E-Cigarette Users, N = 550

| EVALI Symptomsa | Health Concern | Policy Support | Positive Policy Impactc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B | CI | p | B | CI | p | B | CI | p | B | CI | p |

| MSA (ref = Boston) | ||||||||||||

| Atlanta | −.31 | −.55, −.08 | .010 | .07 | −.19, .33 | .573 | .05 | −.23, .34 | .713 | .08 | −.14, .31 | .461 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul | .03 | −.20, .26 | .811 | −.03 | −.28, .22 | .824 | .01 | −.27, .28 | .961 | .06 | −.16, .28 | .592 |

| Oklahoma City | .07 | −.28, .43 | .688 | −.37 | −.75, .01 | .058 | .26 | −.17, .69 | .230 | .13 | −.21, .46 | .461 |

| San Diego | −.27 | −.51, −.03 | .027 | −.24 | −.50, .02 | .066 | .10 | −.19, .38 | .518 | .20 | −.02, .43 | .080 |

| Seattle | −.14 | −.37, .10 | .248 | −.13 | −.38, .12 | .305 | .05 | −.23, .32 | .750 | −.05 | −.26, .17 | .683 |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||||||||

| Age | .03 | .01, .06 | .008 | −.02 | −.04, .01 | .213 | .03 | −.01, .06 | .074 | −.01 | −.04, .01 | .270 |

| Male (ref = female)b | −.02 | −.17, .13 | .790 | .01 | −.17, .15 | .919 | −.15 | −.33, .02 | .087 | −.14 | −.28, .01 | .052 |

| Sexual minority (ref = heterosexual) | −.01 | −.16, .15 | .938 | −.06 | −.22, .11 | .500 | −.22 | −.40, −.03 | .020 | −.15 | −.29, −.01 | .035 |

| Race (ref = White) | ||||||||||||

| Black | .69 | .30, 1.08 | .001 | −.11 | −.54, .32 | .606 | .14 | −.33, .61 | .556 | .39 | .02, .76 | .037 |

| Asian | .24 | .00, .48 | .050 | .04 | −.22, .30 | .785 | .27 | −.02, .56 | .066 | −.01 | −.23, .22 | .995 |

| Other | .11 | −.11, .33 | .328 | −.03 | −.27, .21 | .804 | −.03 | −.30, .24 | .825 | −.13 | −.34, .07 | .204 |

| Hispanic (ref = non-Hispanic) | .13 | −.10, .35 | .260 | .04 | −.21, .28 | .766 | −.04 | −.31, .23 | .775 | −.03 | −.24, .18 | .781 |

| E-cigarette use characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Age at first use | −.05 | −.08, −.02 | <.001 | .01 | −.02, .04 | .641 | −.01 | −.05, .02 | .367 | .01 | −.02, .03 | .518 |

| Number of days used in past 30 days | −.01 | −.01, .01 | .116 | −.01 | −.02, −.01 | <.001 | −.03 | −.04, −.03 | <.001 | −.02 | −.03, −.01 | <.001 |

| Open system/tank use (ref = closed) | .04 | −.11, .19 | .564 | −.19 | −.35, −.03 | .021 | −.15 | −.32, .03 | .113 | .05 | −.09, .19 | .516 |

| Other tobacco use | ||||||||||||

| Past 30-day cigarette user | .15 | −.03, .34 | .109 | −.12 | −.33, .08 | .228 | −.09 | −.32, .13 | .417 | −.92 | −1.10, −.75 | <.001 |

| Past 30-day other tobacco user | .44 | .28, .60 | <.001 | −.19 | −.37, −.01 | .040 | −.09 | −.29, .11 | .359 | −.09 | −.25, .07 | .256 |

| Former cigarette smoker | .04 | −.17, .25 | .699 | −.06 | −.29, .16 | .575 | −.13 | −.38, .12 | .291 | −.29 | −.49, −.10 | .004 |

| E-cigarette health effects | ||||||||||||

| EVALI symptoms | — | — | — | .41 | .28, .55 | <.001 | .34 | .18, .50 | <.001 | .01 | −.11, .13 | .874 |

| Health concern | — | — | — | — | — | -- | .40 | .30, .51 | <.001 | .18 | .10, .26 | <.001 |

| Social/media influences | — | — | — | .18 | .08, .28 | .001 | −.01 | −.12, .10 | .860 | −.03 | −.12, .06 | .518 |

| Adjusted R2 | .166 | .195 | .393 | .361 |

MSA, metropolitan statistical areas; EVALI, e-cigarette/vaping-associated lung injury; B, beta; CI, 95% confidence interval. Exploratory analyses using multilevel modeling to account hierarchical structure of the data (ie, young adults at the individual level nested in MSA) were conducted; all intra-class correlations ranged from 0 to .01, and findings were not significantly different.

Italic p-values indicate significance (ie, p < .05).

aIn preliminary analyses, neither marijuana use nor marijuana vaping contributed significantly to the model.

bThose reporting “other” sex are excluded from these analyses.

c“If the government restricted vape products to tobacco flavors only, how likely would you be to continue to vape or use e-cigarettes?” Correlates of being less likely to continue to vape: living in Oklahoma City (vs. Boston), being female, fewer days of e-cigarette use, and being a never cigarette smoker. “If the government restricted vape products to tobacco flavors only, how likely would you be to switch to traditional cigarettes?” Correlates of being less likely to switch to cigarettes: being Black, fewer days of e-cigarette use, being a never cigarette smoker, and greater health concern. “If the government banned all vape product sales, how likely would you be to switch to traditional cigarettes?” Correlates of being less likely to switch: being Black, being heterosexual, fewer days of e-cigarette use, being a never cigarette smoker, and greater health concern.

Among e-cigarette users, 20.0% reported not being concerned, 40.7% a little, 25.3% somewhat, and 10.0% very concerned about the health effects of vaping (not shown in tables). Regression results (Table 2) indicated that greater health concern among e-cigarette users correlated with fewer days of use (p < .001), using a closed system device (p = .021), no past-month other tobacco product use (p = .040), reporting more EVALI symptoms (p < .001), and greater social/media influences emphasizing negative health effects (p = .001; aR2 = .195).

Policy Support

The average e-cigarette policy support score was 2.25 (eg, reflecting “neutral/don’t know to somewhat support”; Table 1). Overall, 24.2% of e-cigarette users and 57.6% of nonusers reported strongly/somewhat supporting policy to restrict flavored vape product sales; 15.1% of e-cigarette users and 45.1% of e-cigarette nonusers reported strongly/somewhat supporting policy to restrict all vape product sales. Per multivariable regression results, greater policy support among all participants (not shown in table) correlated with being an e-cigarette nonuser (B = −1.27, SE = .06, p < .001), residing in Boston (vs. Seattle; B = −0.26, SE = .09, p = .004), as well as being female (B = −0.28, SE = .06, p < .001), heterosexual (B = −0.23, SE = .06, p < .001), and Black (vs. White, B = 0.34, SE = .12, p = .006) or Asian (vs. White, B = 0.37, SE = .08, p < .001; aR2 = .210). Among e-cigarette users (Table 2), greater policy support correlated with being heterosexual (p = .020), fewer days of e-cigarette use (p < .001), reporting more EVALI symptoms (p < .001), and greater health concerns (p = .001; aR2 = .393).

Perceived Policy Impact

The average positive e-cigarette policy impact score was 1.89 (ie, reflecting an average report of “somewhat to a little”; Table 1). If policy was implemented to restrict vape products to tobacco flavor only, 39.1% of e-cigarette users indicated being very or somewhat likely to continue using e-cigarettes, and 33.2% of e-cigarette users reported being very or somewhat likely to switch to traditional cigarettes. Also, 14.9% reported being very or somewhat likely to both continue to use e-cigarettes and switch to traditional cigarettes. However, 30.5% of e-cigarette users reported being not at all likely to continue to use e-cigarettes, and 45.5% of e-cigarette users reported being not at all likely to switch to traditional cigarettes (17.1% reported being not at all likely to do either). If all vape product sales were restricted, 39.4% of e-cigarette users said that they would be very or somewhat likely to switch to traditional cigarettes. However, 38.9% of e-cigarette users reported being not at all likely to switch to traditional cigarettes. Among e-cigarette users who did not currently use cigarettes: a) 72.2% reported being “not at all likely” (39.4%) or “a little likely” (32.8%) to continue vaping if vape product flavors were restricted; b) 79.8% reported being “not at all likely” (72.7%) or “a little likely” (7.1%) to switch to cigarettes if vape product flavors were restricted; and c) 75.8% reported being “not at all likely” (63.7%) or “a little likely” (12.1%) to switch to cigarettes if all vape products were restricted.

In multivariable regression (Table 2), greater positive policy impact correlated with being heterosexual (p = .035) and Black (p = .037), fewer days of use (p < .001), not being a current (p < .001) or former smoker (p = .004), and greater health concern (p < .001; aR2 = .361). We also explored each item separately, which indicated that, across items, fewer days of e-cigarette use and being a never cigarette smoker predicted less likelihood of continuing to vape or switching to cigarettes as a result of flavor or complete sales restrictions; greater health concern also predicted less likelihood of switching to cigarettes as a result of vape product flavor or complete sales restrictions. Additionally, being female and in Oklahoma City (vs. Boston) predicted less likelihood of continuing to vape as a result of vape product flavor restrictions, being Black (vs. White) predicted less likelihood of switching to cigarettes as a result of flavor or complete sales restrictions, and being a sexual minority predicted greater likelihood of switching to cigarettes because of complete sales restrictions.

Discussion

Among e-cigarette users in this young adult sample, 30.5% reported being unlikely to continue using e-cigarettes and 45.5% reported being unlikely to switch to cigarettes if a policy restricting vape product sales to tobacco flavor only was implemented; however, 39.1% reported being likely to continue using e-cigarettes and 33.2% reported being likely to switch to cigarettes, with 14.9% being likely to do both. If sales of vape products were eliminated entirely, equal numbers (~39%) of e-cigarette users were likely versus unlikely to switch to cigarettes. These findings underscore the complexities in anticipating the likely outcomes of restricting e-cigarette flavors documented in prior research26,31 and reflect those complexities resulting from restricting menthol cigarettes.21–24,26,31,34 Note, however, that roughly 75% of e-cigarette users not currently using cigarettes reported being unlikely to continue vaping or to switch to cigarettes as a result of such restrictions. These findings support previous research26,31 by highlighting the potential importance of comprehensive restrictions (all flavors of all tobacco products) as well as the need to monitor changes in conventional tobacco product use in order to anticipate and react to such implications.

While nonusers reported substantial support for sales restrictions (57.6% for flavored vape products and 45.1% for all vape products), there was also considerable opposition, particularly among e-cigarette users. Young adults (aged 18–34) represent 20.5% of the US population,46 but less than 10% are e-cigarette users3 (thus, a small proportion of eligible voters). Other segments of the population show high levels of support for such policies.29–31

Current findings also suggest that less frequent e-cigarette use and greater health concerns, as well as being heterosexual, correlated with greater policy support and perceived impact. Additionally, being Black and a never smoker was associated with indicating greater positive policy impact, and greater policy support was reported by e-cigarette users experiencing more symptoms associated with EVALI. These findings align with prior research regarding policy support and impact specifically with regard to e-cigarette restrictions29–32,47 and the broader range of tobacco control efforts.33,48

Regarding health effects and concerns, greater negative EVALI symptoms correlated with earlier initiation and other tobacco use as well as being older and Black. Past studies have observed similar results with greater symptoms among those initiating earlier38,49 and dual usage with other tobacco products.50 As described in the National Cancer Institute (NCI) monograph on tobacco disparities,33 Blacks report more symptoms, possibly because of environmental stressors and perceived discrimination. Not surprisingly, greater health concerns correlated with reporting greater EVALI symptoms as well as more social/media influences emphasizing the negative health effects of e-cigarette use. Those reporting greater health concerns used e-cigarettes less frequently (perhaps reflecting efforts to minimize use and health effects); however, they were more likely to use closed system e-cigarettes, which reflects some findings that closed systems (commonly containing nicotine salts) may be linked to respiratory symptoms.42,43

Current findings have implications for research and practice. First, additional research is needed to anticipate the potential impact of such sales restrictions on young adults, as well as the broader population, particularly within the context of other tobacco products, product characteristics (ie, flavors), and related regulations/policies. Indeed, surveillance of these outcomes is needed as local jurisdictions, states, and federal governments globally continue to implement e-cigarette sales restrictions. Moreover, current findings can inform campaigns to garner support for e-cigarette sales restrictions as well as how they are implemented and evaluated over time and within different policy contexts.

Limitations

Using hypothetical scenarios to assess individuals’ potential responses to policies may inaccurately reflect what would actually occur. These items also did not account for dual-use behaviors as a result of such restrictions or the differential impact of e-cigarette versus cigarette use. For example, as a result of e-cigarette flavor restrictions, an individual could report being very likely to continue vaping and unlikely to switch to cigarettes—or could report being very likely to switch to cigarettes and unlikely to continue vaping. Note, however, that findings from multivariable analyses for each of these items separately also indicated similar key predictors, specifically that fewer days of e-cigarette use and being a never cigarette smoker predicted more positive impact. We also did not ask about comprehensive restrictions on all flavored tobacco sales, nor did we specify in what level of “government” the assessment referred to, which may have influenced responses. However, there is some consistency among responses from this young adult panel and findings from other methods, including discrete choice experiments,21,26 surveys in Canada,22–24 and simulation models.34 This data collection wave did not assess flavor use, although prior research suggests that tobacco flavor use is highly common among current and former cigarette smokers, whereas nontobacco flavor use is the most common among never smokers.7,14,15,17 Thus, flavor preference could have been largely accounted for by the other tobacco use variables included in the models. Also, rates of e-cigarette use and policy support in this sample should not be interpreted as reflections of national estimates, given this study’s purposive sampling design. Other limitations include the sample’s limited generalizability; however, this analysis provides a foundation for subsequent analyses that may capture potential natural experiments.

Conclusions

Current findings regarding young adults’ perceptions of sales restrictions on flavored vape products and on all vape products indicate that such policies may not only have a positive impact (ie, reduced e-cigarette use prevalence) but also underscore the potential for no impact (ie, continued e-cigarette use) or negative impact (ie, switch to cigarettes or dual use). Those most likely to perceive positive outcomes of such policies being implemented were less frequent users, never smokers, and those with greater e-cigarette-related health concerns. Moreover, nonusers reported mixed support for such policies, with e-cigarette users indicating low levels of support. This research is timely given the movement toward implementing e-cigarette sales restrictions and can inform future tobacco control initiatives.

Supplementary Material

A Contributorship Form detailing each author’s specific involvement with this content, as well as any supplementary data, are available online at https://academic.oup.com/ntr.

Contributor Information

Heather Posner, Global Health Epidemiology and Disease Control, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA.

Katelyn F Romm, Department of Prevention and Community Health, Milken Institute School of Public Health; George Washington Cancer Center, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA.

Lisa Henriksen, Department of Medicine, Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, USA.

Debra Bernat, Department of Epidemiology, Milken Institute School of Public Health; George Washington Cancer Center, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA.

Carla J Berg, Department of Prevention and Community Health, Milken Institute School of Public Health; George Washington Cancer Center, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA.

Funding

This publication was supported by the US National Cancer Institute (R01CA215155-01A1; PI: Berg). CJB is also supported by other US National Cancer Institute funding (R01CA179422-01; PI: Berg; R01CA239178-01A1; MPIs: Berg and Levine), the US National Institutes of Health/Fogarty International Center (1R01TW010664-01; Multiple Principal Investigators [MPIs]: Berg and Kegler), and the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences/Fogarty International Center (D43ES030927-01; MPIs: Berg, Marsit, and Sturua). LH is supported by other NCI funding (5R01CA067850-17; PI: Henriksen; 1R01CA217165; PI: Henriksen; 1P01CA0225597; MPI: Henriksen, Luke, and Ribisl). DB is supported by NCI (R01CA226074-01; MPIs: Bernat and Horn).

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1. Kennedy RD, Awopegba A, De León E, Cohen JE. Global approaches to regulating electronic cigarettes. Tob Control. 2017;26(4):440–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang TW, Neff LJ, Park-Lee E, Ren C, Cullen KA, King BA. E-cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1310–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan CG, Neff LJ. Tobacco product use among adults—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(46):1736–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. New Report One of the Most Comprehensive Studies on Health Effects of E-Cigarettes; Finds That Using E-Cigarettes May Lead Youth to Start Smoking, Adults to Stop Smoking. Washington, DC: The National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine; 2018. https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2018/01/new-report-one-of-most-comprehensive-studies-on-health-effects-of-e-cigarettes-finds-that-using-e-cigarettes-may-lead-youth-to-start-smoking-adults-to-stop-smoking. Accessed January 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Romberg AR, Miller Lo EJ, Cuccia AF, et al. Patterns of nicotine concentrations in electronic cigarettes sold in the United States, 2013-2018. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;203:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen JC, Das B, Mead EL, Borzekowski DLG. Flavored e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking susceptibility among youth. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(1):68–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berry KM, Fetterman JL, Benjamin EJ, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with subsequent initiation of tobacco cigarettes in US youths. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e187794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Treur JL, Rozema AD, Mathijssen JJP, van Oers H, Vink JM. E-cigarette and waterpipe use in two adolescent cohorts: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations with conventional cigarette smoking. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(3):323–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldenson NI, Leventhal AM, Stone MD, McConnell RS, Barrington-Trimis JL. Associations of electronic cigarette nicotine concentration with subsequent cigarette smoking and vaping levels in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(12):1192–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Siegel DA, Jatlaoui TC, Koumans EH, et al. ; Lung Injury Response Clinical Working Group; Lung Injury Response Epidemiology/Surveillance Group. Update: Interim guidance for health care providers evaluating and caring for patients with suspected e-cigarette, or vaping, product use associated lung injury—United States, October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(41):919–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control. Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html. Published 2019. Accessed January 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Lung Association. State of Tobacco Control, 2018. Chicago, Il: American Lung Association; 2018. https://www.lung.org/research/sotc. Accessed January 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Public Health Law Center. U.S. E-Cigarette Regulations—50 State Review (2019). Saint Paul, MN: Public Health Law Center. https://publichealthlawcenter.org/resources/us-e-cigarette-regulations-50-state-review. Published 2019. Accessed January 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Villanti AC, Johnson AL, Ambrose BK, et al. Flavored tobacco product use in youth and adults: findings from the first wave of the PATH Study (2013-2014). Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(2):139–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhalerao A, Sivandzade F, Archie SR, Cucullo L. Public health policies on e-cigarettes. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21(10):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zare S, Nemati M, Zheng Y. A systematic review of consumer preference for e-cigarette attributes: flavor, nicotine strength, and type. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harrell MB, Weaver SR, Loukas A, et al. Flavored e-cigarette use: characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Public Health Law Center. U.S. E-Cigarette Regulation: A 50-State Review. Saint Paul, MN: Public Health Law Center. https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/sites/default/files/E-Cigarette-Legal-Landscape-March15-2021.pdf. Published 2021. Accessed June 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hemmerich N. Flavoured pod attachments score big as FDA fails to enforce premarket review. Tob Control. 2020;29(e1):e129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kowitt SD, Goldstein AO, Schmidt AM, Hall MG, Brewer NT. Attitudes toward FDA regulation of newly deemed tobacco products. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3(4):504–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guillory J, Kim AE, Nonnemaker JM, et al. Effect of menthol cigarette and other menthol tobacco product bans on tobacco purchases in the RTI iShoppe virtual convenience store. Tob Control. 2020;29(4):452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chaiton M, Schwartz R, Cohen JE, Soule E, Eissenberg T. Association of Ontario’s ban on menthol cigarettes with smoking behavior 1 month after implementation. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(5):710–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chaiton MO, Nicolau I, Schwartz R, et al. Ban on menthol-flavoured tobacco products predicts cigarette cessation at 1 year: a population cohort study. Tob Control. 2020;29(3):341–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soule EK, Chaiton M, Zhang B, et al. Menthol cigarette smoker reactions to an implemented menthol cigarette ban. Tob Reg Sci. 2019;5(1):50–64. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rose SW, Ganz O, Zhou Y, et al. Longitudinal response to restrictions on menthol cigarettes among young adult US menthol smokers, 2011-2016. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1400–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Buckell J, Marti J, Sindelar JL. Should flavours be banned in cigarettes and e-cigarettes? Evidence on adult smokers and recent quitters from a discrete choice experiment. Tob Control. 2019;28(2):168–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Friedman AS. A difference-in-differences analysis of youth smoking and a ban on sales of flavored tobacco products in San Francisco, California. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(8):863–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Agaku IT, Odani S, Armour BS, King BA. Adults’ favorability toward prohibiting flavors in all tobacco products in the United States. Prev Med. 2019;129:105862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Czaplicki L, Perks SN, Liu M, et al. Support for e-cigarette and tobacco control policies among parents of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(7):1139–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang Y, Lindblom EN, Salloum RG, Ward KD. The impact of a comprehensive tobacco product flavor ban in San Francisco among young adults. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;11:100273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jongenelis MI, Kameron C, Rudaizky D, Pettigrew S. Support for e-cigarette regulations among Australian young adults. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. U.S. National Cancer Institute. A Socioecological Approach to Addressing Tobacco-Related Health Disparities. National Cancer Institute Tobacco Control Monograph 22. NIH Publication No. 17-CA-8035A. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2017. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/monograph-22. Accessed January 1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Levy DT, Pearson JL, Villanti AC, et al. Modeling the future effects of a menthol ban on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(7):1236–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Public Health Law Center. Commercial Tobacco and Marijuana: https://www.publichealthlawcenter.org/topics/commercial-tobacco-control/commercial-tobacco-and-marijuana. 2020. Accessed January 1, 2021.

- 36. Schauer GL, Berg CJ, Kegler MC, Donovan DM, Windle M. Assessing the overlap between tobacco and marijuana: trends in patterns of co-use of tobacco and marijuana in adults from 2003-2012. Addict Behav. 2015;49:26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schauer GL, King BA, Bunnell RE, Promoff G, McAfee TA. Toking, vaping, and eating for health or fun: marijuana use patterns in adults, U.S., 2014. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Navon L, Jones CM, Ghinai I, et al. Risk factors for e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) among adults who use e-cigarette, or vaping, products—Illinois, July-October 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(45):1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berg CJ, Duan X, Getachew B, et al. Young adult e-cigarette use and retail exposure in 6 US metropolitan areas. Tob Reg Sci. 2020;7(1):59–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bauermeister J, Pingel E, Zimmerman M, Couper M, Carballo-Diéguez A, Strecher VJ. Data quality in web-based HIV/AIDS research: handling invalid and suspicious data. Field methods. 2012;24(3):272–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. National Institutes of Health. The Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health. https://pathstudyinfo.nih.gov/UI/FAQsResMobile.aspx. Published 2016. Accessed October 1, 2016.

- 42. Blagev DP, Harris D, Dunn AC, Guidry DW, Grissom CK, Lanspa MJ. Clinical presentation, treatment, and short-term outcomes of lung injury associated with e-cigarettes or vaping: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394(10214):2073–2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kechter A, Schiff SJ, Simpson KA, et al. Young adult perspectives on their respiratory health symptoms since vaping. Subst Abus. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2020.1856290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alexander JP, Williams P, Lee YO. Youth who use e-cigarettes regularly: a qualitative study of behavior, attitudes, and familial norms. Prev Med Rep. 2019;13:93–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bovaird JA, Shaw LH. Multilevel structural equation modeling. In: Handbook of Developmental Research Methods. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2012:501–518. [Google Scholar]

- 46. United States Census Bureau. United States Census Bureau: Population. Washington, DC: United States Census Bureau; 2021. https://www.census.gov/topics/population.html. Accessed August 26, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mello S, Bigman CA, Sanders-Jackson A, Tan AS. Perceived harm of secondhand electronic cigarette vapors and policy support to restrict public vaping: results from a national survey of US adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(5):686–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Allen JA, Duke JC, Davis KC, Kim AE, Nonnemaker JM, Farrelly MC. Using mass media campaigns to reduce youth tobacco use: a review. Am J Health Promot. 2015;30(2):e71–e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. McConnell R, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wang K, et al. Electronic cigarette use and respiratory symptoms in adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(8):1043–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bhatta DN, Glantz SA. Association of e-cigarette use with respiratory disease among adults: a longitudinal analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(2):182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.