Abstract

Rifampin in combination with erythromycin is a recommended treatment for severe cases of legionellosis. Mutations in the rpoB gene are known to cause rifampin resistance in Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and the purpose of the present study was to investigate a possible similar resistance mechanism within the members of the family Legionellaceae. Since the RNA polymerase genes of this genus have never been characterized, the DNA sequence of the Legionella pneumophila rpoB gene was determined by the Vectorette technique for genome walking. A 4,647-bp DNA sequence that contained the open reading frame (ORF) of the rpoB gene (4,104 bp) and an ORF of 384 bp representing part of the rpoC gene was obtained. A 316-bp DNA fragment in the center of the L. pneumophila rpoB gene, corresponding to a previously described site for mutations leading to rifampin resistance in M. tuberculosis, was sequenced from 18 rifampin-resistant Legionella isolates representing four species (L. bozemanii, L. longbeachae, L. micdadei, and L. pneumophila), and the sequences were compared to the sequences of the fragments from the parent (rifampin-sensitive) strains. Six single-base mutations which led to amino acid substitutions at five different positions were identified. A single strain did not contain any mutations in the 316-bp fragment. This study represents the characterization of a hitherto undescribed resistance mechanism within the family Legionellaceae.

Infections caused by members of the family Legionellaceae can be life threatening and are associated with a high rate of mortality, especially in immunocompromised patients (21). Treatment of these infections necessitates the use of antibiotics that penetrate well into macrophages since these are the host cells of strains of the family Legionellaceae in human infection (16). Among such drugs, rifampin in combination with erythromycin is a recommended treatment for severe Legionnaire's disease (13). This recommendation is based upon clinical results and especially in vitro data, with rifampin being the most effective drug, as judged by MICs (25) and excellent penetration into macrophages (14). Development of resistance toward rifampin has sporadically been reported as an in vitro phenomenon (11, 23), but with no attempt to characterize the genetic resistance mechanism.

Rifampin exerts its action by binding to the RNA polymerase. Resistance can be induced by point mutations in the rpoB gene, which codes for the β subunit of the RNA polymerase. Such mutations have been described in Escherichia coli (17) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (18, 22), but other resistance mechanisms have been proposed as well (9, 10). In order to investigate any potential rifampin resistance mechanism within the family Legionellaceae, we produced rifampin-resistant derivatives of Legionella bozemanii, L. longbeachae, L. micdadei, and L. pneumophila by cultivation of these species on rifampin-containing media. Since the rpoB gene has not previously been characterized for any Legionella species, the total DNA sequence of the L. pneumophila rpoB gene was determined. By using these sequence data, a 316-bp region in the sequences of rifampin-resistant Legionella strains corresponding to the previously reported hot-spot region for rifampin resistance mutations in M. tuberculosis (18) was searched for mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The rifampin-susceptible (wild-type) strains were L. bozemanii K26 (clinical isolate), L. longbeachae K47 (ATCC 33462), K48 (ATCC 33484), and K72 (clinical isolate), L. pneumophila K69 and K91 (both clinical isolates), L. micdadei K74 (clinical isolate), and L. oakridgensis K78 (environmental isolate). Rifampin MICs for all strains were <0.016 μg/ml. The clinical isolates were all from patients at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark, with the species designation confirmed at the Legionella reference laboratory, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen. Rifampin-resistant isolates were obtained by culturing an inoculum of 4.8 × 107 CFU on buffered charcoal yeast extract agar with α-ketoglutarate (BCYE-α) containing 1.6 or 16 μg of rifampin per ml. The plates were incubated in plastic bags for 1 to 2 weeks at 37°C. MIC determinations were performed by the E-test (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) on BCYE-α plates. Testing for reversion from the resistant to the susceptible phenotype was performed by subculturing the resistant strains on BCYE-α without rifampin for 12 passages.

DNA methods.

Chromosomal DNA was purified by pretreatment with sodium dodecyl sulfate, lysozyme, and proteinase K, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and RNase treatment as described previously (4).

Except where specified, PCR was performed in a total volume of 100 μl containing approximately 100 ng of target DNA; 50 μM each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP; 1.5 mM MgCl2; 50 mM KCl; 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3); and 2.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold polymerase (Perkin Elmer, Allerød, Denmark). The final concentration of each primer was 0.2 to 1 μM. Amplification was carried out in a Perkin-Elmer Cetus DNA thermal cycler heated to 95°C for 8 min before 35 cycles of 93°C for 1 min, 52 to 54°C for 1.5 min, and 72°C for 2 min, followed by extension at 72°C for 10 min. Amplicons were purified from 0.7 to 1% agarose gels (SeaKem GTG; FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine) by using Spin-X centrifuge tubes (Corning Costar Corporation, Cambridge, Mass.).

Vectorette libraries.

The Vectorette system was developed for the amplification of and sequencing of DNA adjacent to a known sequence of DNA by unidirectional PCR (3) and thus is applicable for genome walking (5). The Vectorette system includes three basic steps: digestion of target DNA with a suitable restriction enzyme, establishment of libraries by ligation of compatible synthetic oligonucleotides (Vectorettes) onto the digested DNA, and finally, PCR with a primer specific to the known DNA sequence and a primer directed toward the Vectorette unit used. An amount of approximately 0.2 μg of purified DNA from a clinical isolate of L. pneumophila (K69) was digested with the restriction enzymes BamHI, ClaI, EcoRI, and HindIII in separate tubes. Four Vectorette libraries were constructed by ligation of the corresponding compatible Vectorette units (Vectorette II; Genosys Biotechnologies, Cambridge, United Kingdom) (http://www.genosys.co.uk/vectorette.htm) onto the DNA fragments. Vectorette units (3 pmol) were added to 50 μl of the restriction enzyme-cut DNA by using 1 U of T4 DNA ligase (Pharmacia, Hillerød, Denmark), with ATP and dithiothreitol concentrations adjusted to 1.7 mM. The reaction mixture was incubated at 20°C for 1 h, followed by incubation for 30 min at 37°C. This temperature cycle was repeated twice before enzyme inactivation at 60°C for 10 min. Amplification of the Vectorette libraries was carried out in a final volume of 100 μl containing 1 pmol of specific primer, 100 pmol of Vectorette primer, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Amplification was started by adding 1 μl of the Vectorette library at 94°C. The amplification reaction was run at 94°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2.5 min for 35 cycles, followed by extension at 72°C for 10 min. The Vectorette amplicons were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and were sequenced as described below.

DNA sequence of the L. pneumophila rpoB gene.

Single point mutations in the RNA polymerase subunit rpoB gene are responsible for rifampin resistance in E. coli and M. tuberculosis. We presumed that an equivalent resistance mechanism exists in Legionella. As a first step toward demonstrating this, we decided to determine the entire sequence of the L. pneumophila rpoB gene. To this end, the RpoB amino acid sequences from eight different bacterial species were aligned, and two phylogenetically conserved domains were identified in the central part of the rpoB gene. On the basis of this alignment, we predicted that RRVRSVGE and PEGPNIGL were the most probable amino acid sequences of the corresponding domains in Legionella. The codon usage for the Legionellaceae was calculated from approximately 2,500 known codons, and two Legionella-biased PCR primers, RIF U1 (5′-CGI CGI GTT CGI TC(AGC) GT(AT) GG(ACT) GA-3′) and RIF D1 (5′-AA(GAT) CCA ATA TT(AT) GG(GAT) CCT TC(AGC) GG-3′), were synthesized. Total L. pneumophila DNA was used as the template in a PCR with primers RIF U1 and RIF D1, and a PCR product of 0.3 kbp was obtained. This size is in close agreement with the expected distance of approximately 80 codons between the two primers. The 0.3-kbp fragment was purified from an agarose gel and sequenced. The exact size of the amplified fragment was 316 bp. One of the six possible open reading frames contained sequence homology to the rpoB gene of other bacteria and had a typical L. pneumophila codon usage. The total rpoB sequence was determined by several successive PCR amplifications with the Vectorette II system (Fig. 1). Several sequences obtained from overlapping Vectorette PCR products were assembled to yield most of the sequence except for the sequence near the N terminus, which could not be determined by this technique. The rplL gene encodes the 50S ribosomal subunit protein L7/L12 and is situated upstream of the rpoB gene in several bacterial species (1, 8). We assumed a similar localization of the rplL gene in L. pneumophila, and by alignment of five different bacterial rplL sequences a consensus amino acid sequence of EEAGAEVE was determined. By using the information on L. pneumophila codon usage from above, a Legionella-specific primer for the C-terminal end of the rplL gene (5′-GAA GA(GA) GCI GG(TC) GCI GA(GA) GT(GAT) GA-3′) was designed and used for PCR in combination with the sequencing primer 8992 (5′-TCG GTC ATT AGA GGA ATT TCC CCC-3′). A PCR product of 0.7 kb spanning the region between rplL and rpoB was generated. This fragment was partly sequenced in order to determine the rpoB N terminus.

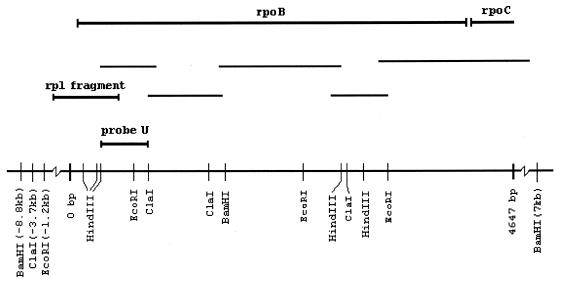

FIG. 1.

Sequencing strategy for the rpoB gene in L. pneumophila. The thin bars represent the amplicons from the Vectorette PCR. The locations of sites for the restriction enzymes BamHI, ClaI, EcoRI, and HindIII are shown. The approximate positions upstream of the gene were found by Southern blotting with probe U. The C-terminal end of the rplL gene is also indicated.

PCR amplicons were sequenced with the Dye Deoxy Terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer). All procedures were performed according to the instructions in the manual provided with the kit. The samples were sequenced in a 377 PRISM DNA cycler (Perkin-Elmer). DNA sequences were analyzed by using the two programs Sequencher (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, Mich.) and DNASIS (Hitachi Software Engineering Company Ltd.). A total of 4,647 bp was sequenced in both directions.

Southern hybridization.

Chromosomal DNA from L. pneumophila (approximately 1 μg) was cleaved with each of the restriction enzymes used for the Vectorette libraries. The digested DNA was loaded onto an agarose gel, and after electrophoresis, depurination was performed with 0.25 M HCl. DNA was transferred to a nylon membrane (ZetaProbe GT blotting membrane; Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) overnight in transfer buffer (0.6 M NaCl, 0.5 M NaOH). The membrane was prehybridized in hybridization buffer (0.75 M NaCl, 75 mM sodium citrate, 10 g of blocking reagent per liter, 0.1% sodium N-lauroylsarcosine) for 1 h at 60°C. Hybridization was performed with a 504-bp digoxigenin-labeled probe (Fig. 1) complementary to part of the N-terminal end of the L. pneumophila rpoB gene (probe U). This probe was constructed by amplification of chromosomal L. pneumophila DNA with two primers, 9004 (5′-GCC TGC ATT TGA TGT TCG CGA ATG C-3′) and 9005 (5′-GGA ATT AAA TCG ATG TGG TAT TCG C-3′). Digoxigenin labeling and detection were carried out according to the instructions of the manufacturer (DIG DNA Labeling and Detection Non-radioactive Applications; Boehringer Mannheim).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 4,647-bp L. pneumophila DNA fragment containing the full sequence of the L. pneumophila rpoB gene and part of the rpoC gene is stored in GenBank under accession number AF087812, and the 316-bp rpoB fragments from the different Legionella species are stored in GenBank under accession numbers AF101270 (L. bozemanii), AF101271 (L. longbeachae), AF101272 (L. micdadei), AF101273 (L. pneumophila), AF113669 (L. longbeachae), and AF113670 (L. pneumophila).

RESULTS

Development of rifampin resistance.

Five of eight Legionella strains produced colonies on BCYE-α containing 1.6 μg of rifampin per ml, and three strains produced colonies on BCYE-α with 16 μg of rifampin per ml. Rifampin MICs for the resistant derivatives of strains K74 and K91 were 3 and 12 μg/ml, respectively; the MICs for all other resistant isolates were >256 μg/ml. One of the species investigated (L. oakridgensis) did not produce any colonies on the rifampin-containing media. Rifampin resistance was found to be stable for at least 12 passages on antibiotic-free media.

DNA sequence of L. pneumophila rpoB gene.

A stretch of 4,647 bases contained an open reading frame of 1,367 codons representing the L. pneumophila rpoB gene (GenBank accession number AF087812). Two putative ATG start codons were found at coordinates 69 and 153. Comparisons of the rpoB sequences of E. coli, Pseudomonas putida, and Neisseria meningitidis identified the first ATG codon (coordinate 69) as the most likely start codon. This was supported by identification of typical −10 (AATAAT) and −35 (TTTAC) sequences and a Shine-Dalgarno sequence eight nucleotides upstream of this ATG codon. These comparisons also showed highly conserved domains within the RpoB subunits of these species (data not shown). A 128-codon open reading frame was identified 88 nucleotides downstream of the L. pneumophila rpoB gene. The deduced amino acid sequence showed strong homology with the rpoC gene (which encodes the β′ subunit of the RNA polymerase) of E. coli and other bacteria. Southern hybridization of chromosomal L. pneumophila DNA digested with the enzymes used to construct the Vectorette libraries (BamHI, ClaI, HindIII, and EcoRI) with probe U produced only one band, indicating the existence of only one rpoB gene in the genome (data not shown). These experiments also explained why sequence information about the initial part of the rpoB gene could not be obtained. BamHI and ClaI cleavage sites were 8.8 and 3.7 kb upstream of the gene, respectively, yielding fragments too large for amplification; conversely, the HindIII fragment was too small to be detected by amplification with the conditions used.

Identification of mutations in rifampin-resistant Legionella strains.

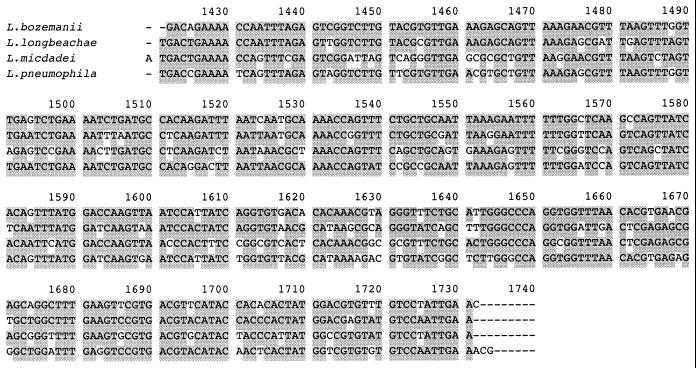

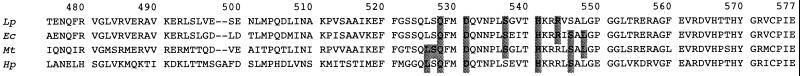

The sequences of the two primers RIF U1 and RIF D1 span a region of rpoB where single point mutations are known to cause rifampin resistance in E. coli and M. tuberculosis. We searched for equivalent mutations in the rifampin-resistant derivatives of L. pneumophila, L. bozemanii, L. micdadei, and L. longbeachae by using RIF U1 and RIF D1 for amplification of total DNA from the 18 rifampin-resistant isolates as well as the corresponding parent strains. A single 0.3-kb fragment was produced in all strains examined, and the fragments were sequenced after extraction from an agarose gel. Within each species, the DNA sequences of the wild-type rpoB fragments were identical (Fig. 2). The deduced amino acid sequences of the 316-bp fragments (wild type) were identical for three species; the sequence of L. micdadei differed from those of the other species in having a valine instead of an isoleucine at codon 517. The DNA sequences of the rifampin-resistant isolates and the wild-type strains were compared for the identification of possible mutations (Table 1). Six point mutations causing amino acid substitutions at five different positions were identified. At position 528, two different substitutions were observed. None of the rifampin-resistant isolates were found to contain more than one mutation. No mutation could be identified in rifampin-resistant isolate 8749 derived from L. bozemanii. Alignment of the amino acid sequence of the 316-bp region of L. pneumophila to the RpoB sequences of other bacterial families in which mutations that lead to rifampin resistance have been reported (M. tuberculosis [18], E. coli [17], and Helicobacter pylori [15]) was performed, and the results are shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 2.

Partial DNA sequences of the rpoB genes of wild-type strains L. bozemanii K26, L. longbeachae K47 and K72, L. micdadei K74, and L. pneumophila K69 and K91. Conserved nucleotides are shaded. Numbering is according to that for the rpoB gene in L. pneumophila (GenBank accession number AF087812).

TABLE 1.

Mutations in the region from positions 528 to 544 of the rpoB gene in rifampin-resistant Legionella isolates

| Isolate designation (parent strain) | Position and amino acid substitutiona |

|---|---|

| 8749 (L. bozemanii K26) | No mutation observed |

| 8750 (L. longbeachae K47) | 528 Gln(CAA)→Leu(CTA) |

| 8751 (L. pneumophila K69) | 541 His(CAT)→Tyr(TAT) |

| 8752 (L. pneumophila K69) | 541 His(CAT)→Tyr(TAT) |

| 8840-43 (L. pneumophila K69) | 541 His(CAT)→Tyr(TAT) |

| 8844 (L. pneumophila K69) | 537 Ser(TCT)→Phe(TTT) |

| 8845-49 (L. pneumophila K69) | 541 His(CAT)→Tyr(TAT) |

| 8753 (L. longbeachae K72) | 528 Gln(CAA)→Lys(AAA) |

| 8754 (L. micdadei K74) | 531 Asp(GAC)→Asn(AAC) |

| 8755 (L. pneumophila K91) | 544 Arg(CGT)→His(CAT) |

| 8756 (L. pneumophila K91) | 537 Ser(TCT)→Phe(TTT) |

Numbering is according to that for the rpoB gene of L. pneumophila (GenBank accession number AF087812) MICs were >256 μg/ml for all isolates except strains 8754 and 8755, for which MICs were 3 and 12 μg/ml, respectively.

FIG. 3.

Alignment of partial β-subunit sequences of the RNA polymerase genes of L. pneumophila (Lp; GenBank accession number AF087812), E. coli (Ec; GenBank accession number P00575), M. tuberculosis (Mt; GenBank accession number P47766), and H. pylori (Hp; GenBank accession number AE000625). Amino acid coordinates correspond to those in the sequence of L. pneumophila. The partial β-subunit sequence of L. pneumophila is identical to those of L. longbeachae (GenBank accession numbers AF101271 and AF113669), L. micdadei (GenBank accession number AF101272), and L. bozemanii (GenBank accession number AF101270), except that L. micdadei has the amino acid valine at position 517. The positions of the mutations found in these Legionella species are all indicated in the L. pneumophila sequence. Known amino acid substitutions associated with rifampin resistance are shaded.

Furthermore, a comparison of the 316-bp region of L. pneumophila to the sequence with mutations that lead to rifampin resistance in N. meningitidis was done (6). In E. coli, the rpoB mutation positions that correspond to those of L. pneumophila are 513, 516, 521, 526, and 529 (cluster I) (17).

None of the positions with amino acid substitutions were unique to the Legionella species investigated, but the substitution observed at one position (544 Arg→His) was not described in other families.

As a control for the specificity of the rpoB mutations for rifampin resistance, the 316-bp rpoB fragment from an erythromycin-resistant (MIC, 1.5 μg/ml) derivative of L. pneumophila produced in our laboratory was sequenced; no mutations were observed.

DISCUSSION

Comparison of the L. pneumophila RpoB amino acid sequence with the sequences of other bacterial RpoB subunits shows that the protein is phylogenetically conserved. Highly conserved domains were identified and most likely correspond to functionally important structures. The three-dimensional structure of the RNA polymerase has not yet been determined for any bacteria, but identification of these phylogenetically conserved domains might contribute to a more detailed understanding of the function of RpoB and the other subunits of this enzyme. The identification of rplL upstream of the rpoB gene and rpoC downstream of the rpoB gene in L. pneumophila suggests that these genes are organized in a manner equivalent to that for other bacterial species. No promoter or terminating hairpin loops can be identified in the noncoding region between rpoB and rpoC, suggesting that these genes are cotranscribed. In E. coli, rplA, rplJ, rplL, rpoB, and rpoC constitute a coregulated operon (24).

The six single-point mutations at five different positions linked to rifampin resistance were identified within a region of only 16 codons. L. bozemanii K26 was the only resistant isolate for which mutations within the 316-bp fragment could not be identified. Additional mutations outside this region cannot be ruled out (17), and other mechanisms have been described for other bacterial families (2, 9).

When comparing sequence data from other bacteria in which rifampin resistance is reported to be associated with mutations in the rpoB gene (E. coli [17], H. pylori [15], M. tuberculosis [18], and N. meningitidis [6]), all of the positions of the substitutions found in the 316-bp region of the Legionella species were represented in other families. One substitution, however (i.e., the substitution of histidine for arginine at position 544), was not found in other bacteria, but the significance of this remains to be proven. We were not able to detect any systematic changes in the charges, polarities, or sizes of the amino acid substitutions leading to rifampin resistance.

Antibiotic resistance has been reported previously among the members of the family Legionellaceae: β-lactamase production (20) and resistance to spectinomycin (26). Furthermore, streptomycin resistance in L. pneumophila has been used as a genetic marker (7). The demonstration of single point mutations in the rpoB gene associated with rifampin resistance in L. pneumophila, L. bozemanii, L. longbeachae, and L. micdadei, however, represents the first molecular elucidation in Legionella of a mechanism of resistance to an antibiotic in clinical use for the treatment of Legionella infections. Although induction of resistance in a clinical setting has not been reported, the present policy of using rifampin only in combination with other antibiotics for the treatment of Legionella infections seems prudent. Development of resistance to rifampin during rifampin treatment in an animal model of L. pneumophila infection could not be demonstrated (12), which seems to conflict with our data and other data regarding the ease of resistance development in vitro.

Amplification of the 316-bp fragment opens a possibility of monitoring drug resistance without cultivation, a clear advantage with slowly growing bacteria such as the members of the family Legionellaceae. The clinical use of this technique, however, still remains to be investigated. Furthermore, taxonomic use of the rpoB gene has been studied with success within the mycobacteria (19). Our sequence data could be extremely useful for this application for the Legionellaceae, since the identification of the individual species within this family can be very difficult.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Kristian Klindt for useful advice concerning DNA sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aboshkiwa M, Al-Ani B, Coleman G, Rowland G. Cloning and physical mapping of the Staphylococcus aureus rplL, rpoB and rpoC genes, encoding ribosomal protein L7/L12 and RNA polymerase subunits beta and beta′. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1875–1880. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-9-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Ani B, Aboshkiwa M, Glass R E, Coleman G. The patterns of extracellular protein formation by spontaneously-occurring rifampicin-resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;70:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold C, Hodgson I J. Vectorette PCR: a novel approach to genomic walking. PCR Methods Appl. 1991;1:39–42. doi: 10.1101/gr.1.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangsborg J M, Gerner-Smidt P, Colding H, Fiehn N-E, Bruun B, Høiby N. Restriction fragment length polymorphism of rRNA genes for molecular typing of members of the family Legionellaceae. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:402–406. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.402-406.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bangsborg J M, Hindersson P, Shand G, Høiby N. The Legionella micdadei flagellin: expression in Escherichia coli and DNA sequence of the gene. APMIS. 1995;103:869–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1995.tb01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter P E, Abadi F J R, Yakubu D E, Pennington T H. Molecular characterization of rifampin-resistant Neisseria meningitidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1256–1261. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.6.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cianciotto N P, Fields B. Legionella pneumophila mip gene potentiates intracellular infection of protozoa and human macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5188–5191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dabbs E R. Order of ribosomal protein genes in the Rif cluster of Bacillus subtilis is identical to that of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:770–772. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.2.770-772.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dabbs E R, Yazawa K, Mikami Y, Miyaji M, Morisaki N, Iwasaki S, Furihata K. Ribosylation by mycobacterial strains as a new mechanism of rifampin inactivation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1007–1009. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.4.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dabbs E R, Yazawa K, Tanaka Y, Mikami Y, Miyaji M. Rifampicin inactivation by Bacillus species. J Antibiot. 1995;48:815–819. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dowling J N, McDevitt D A, Pasculle A W. Disk diffusion antimicrobial susceptibility testing of members of the family Legionellaceae including erythromycin-resistant variants of Legionella micdadei. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:723–729. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.6.723-729.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edelstein P H. Rifampin resistance of Legionella pneumophila is not increased during therapy for experimental Legionnaires' disease: study of rifampin resistance using a guinea pig model of Legionnaires' disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:5–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelstein P H. Legionnaire's disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:741–749. doi: 10.1093/clind/16.6.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hand W L, Corwin R W, Steinberg T H, Grossman G D. Uptake of antibiotics by human alveolar macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:933–937. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1984.129.6.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heep M, Beck D, Bayerdörffer E, Lehn N. Rifampin and rifabutin resistance mechanism in Helicobacter pylori. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:1497–1499. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwitz M A, Maxfield F R. Legionella pneumophila inhibits acidification of its phagosome in human monocytes. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:1936–1943. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.6.1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin D J, Gross C A. Mapping and sequencing of mutations in the Escherichia coli rpoB gene that lead to rifampicin resistance. J Mol Biol. 1988;202:45–58. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapur V, Li L-L, Iordanescu S, Hamrick M R, Wanger A, Kreiswirth B N, Musser J M. Characterization by automated DNA sequencing of mutations in the gene (rpoB) encoding the RNA polymerase β subunit in rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains from New York City and Texas. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1095–1098. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.1095-1098.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim B, Lee S, Lyu M, Kim S, Bai G, Kim S, Chae G, Kim E, Cha C, Kook Y. Identification of mycobacterial species by comparative sequence analysis of the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB) J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1714–1720. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.6.1714-1720.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marre R, Medeiros A A, Pasculle A W. Characterization of the beta-lactamases of six species of Legionella. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:216–221. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.216-221.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marston B J, Lipman H B, Breiman R F. Surveillance for Legionnaires' disease. Risk factors for morbidity and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2417–2422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller L P, Crawford J T, Shinnick T M. The rpoB gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:805–811. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.4.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moffie B G, Mouton R P. Sensitivity and resistance of Legionella pneumophila to some antibiotics and combinations of antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;22:457–462. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ralling G, Linn T. Relative activities of the transcriptional regulatory sites in the rplKAJLrpoBC gene cluster of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:279–285. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.1.279-285.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhomberg P R, Jones R N. Evaluations of the Etest for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Legionella pneumophila, including validation of the imipenem and sparfloxacin strips. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;20:159–162. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson P R, Hughes D W, Cianciotto N P, Wright G D. Spectinomycin kinase from Legionella pneumophila. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14788–14795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]