Abstract

Background

To produce graduates with strong knowledge and skills in the application of evidence into healthcare practice, it is imperative that all undergraduate health and social care students are taught, in an efficient manner, the processes involved in applying evidence into practice. The two main concepts that are linked to the application of evidence into practice are “evidence‐based practice” and “evidence‐informed practice.” Globally, evidence‐based practice is regarded as the gold standard for the provision of safe and effective healthcare. Despite the extensive awareness of evidence‐based practice, healthcare practitioners continue to encounter difficulties in its implementation. This has generated an ongoing international debate as to whether evidence‐based practice should be replaced with evidence‐informed practice, and which of the two concepts better facilitate the effective and consistent application of evidence into healthcare practice.

Objectives

The primary objective of this systematic review was to evaluate and synthesize literature on the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice versus evidence‐based practice educational interventions for improving knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior of undergraduate health and social care students toward the application of evidence into practice. Specifically, we planned to answer the following research questions: (1) Is there a difference (i.e., difference in content, outcome) between evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions? (2) Does participating in evidence‐informed practice educational interventions relative to evidence‐based practice educational interventions facilitate the application of evidence into practice (as measured by, e.g., self‐reports on effective application of evidence into practice)? (3) Do both evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions targeted at undergraduate health and social care students influence patient outcomes (as measured by, e.g., reduced morbidity and mortality, absence of nosocomial infections)? (4) What factors affect the impact of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions (as measured by, e.g., course content, mode of delivery, multifaceted interventions, standalone intervention)?

Search Methods

We utilized a number of search strategies to identify published and unpublished studies: (1) Electronic databases: we searched Academic Search Complete, Academic search premier, AMED, Australian education index, British education index, Campbell systematic reviews, Canada bibliographic database (CBCA Education), CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Database of Abstracts of Reviews on Effectiveness, Dissertation Abstracts International, Education Abstracts, Education complete, Education full text: Wilson, ERIC, Evidence‐based program database, JBI database of systematic reviews, Medline, PsycInfo, Pubmed, SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online), and Scopus; (2) A web search using search engines such as Google and Google scholar; (3) Grey literature search: we searched OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe), System for information on Grey Literature, the Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness, and Virginia Henderson Global Nursing e‐Repository; (4) Hand searching of journal articles; and (5) Tracking bibliographies of previously retrieved studies. The searches were conducted in June 2019.

Selection Criteria

We planned to include both quantitative (including randomized controlled trials, non‐randomized controlled trials, quasi‐experimental, before and after studies, prospective and retrospective cohort studies) and qualitative primary studies (including, case series, individual case reports, and descriptive cross‐sectional studies, focus groups, and interviews, ethnography, phenomenology, and grounded theory), that evaluate and compare the effectiveness of any formal evidence‐informed practice educational intervention to evidence‐based practice educational intervention. The primary outcomes were evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior. We planned to include, as participants, undergraduate pre‐registration health and social care students from any geographical area.

Data Collection and Analysis

Two authors independently screened the search results to assess articles for their eligibility for inclusion. The screening involved an initial screening of the title and abstracts, and subsequently, the full‐text of selected articles. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third author. We found no article eligible for inclusion in this review.

Main Results

No studies were found which were eligible for inclusion in this review. We evaluated and excluded 46 full‐text articles. This is because none of the 46 studies had evaluated and compared the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice educational interventions with evidence‐based practice educational interventions. Out of the 46 articles, 45 had evaluated solely, the effectiveness of evidence‐based practice educational interventions and 1 article was on evidence‐informed practice educational intervention. Hence, these articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Authors' Conclusions

There is an urgent need for primary studies evaluating the relative effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions targeted at improving undergraduate healthcare students' competencies regarding the application of evidence into practice. Such studies should be informed by current literature on the concepts (i.e., evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice) to identify the differences, similarities, as well as appropriate content of the educational interventions. In this way, the actual effect of each of the concepts could be determined and their effectiveness compared.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Evidence‐informed versus evidence‐based practice educational interventions for improving knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior toward the application of evidence into practice: A comprehensive systematic review of undergraduate students

We found no studies that compared the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice educational interventions to evidence‐based practice educational interventions in targeting undergraduate health and social care students' knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior.

1.2. The review in brief

This review aimed to compare the relative effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice versus evidence‐based practice educational interventions on the knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior of undergraduate health and social care students. We did not find any studies that met our inclusion criteria, therefore we cannot draw any conclusions regarding the relative effectiveness of the two approaches. The evidence is current to June 17, 2019.

1.3. What is this review about?

The effective application of the best evidence into healthcare practice is strongly endorsed, alongside a growing need for healthcare organizations to ensure the delivery of services in an equitable and efficient manner. Existing evidence shows that guiding healthcare practice with the best available evidence enhances healthcare delivery, improves efficiency and ultimately improves patient outcomes. Nevertheless, there is often the ineffective and inconsistent application of evidence into healthcare practice.

The two main concepts that have been associated with the application of evidence into healthcare practice are “evidence‐based practice” and “evidence‐informed practice.” This review assesses the relative effectiveness of these two approaches, specifically in relation to improving knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior of undergraduate health and social care students. In addition, we aimed to assess the impact of evidence‐informed practice and/or evidence‐based practice educational programmes on patient outcomes. Examples of patient outcome indicators that we would have assessed had eligible studies been found are: user experience, length of hospital stay, nosocomial infections, patient and health practitioner satisfaction, mortality, and morbidity rates.

What is the aim of this review?

This Campbell systematic review examines the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions for improving knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior of undergraduate health and social care students toward the application of evidence into practice.

1.4. What studies are included?

We planned to include both quantitative and qualitative studies aimed at improving knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior of undergraduate pre‐registration health and social care students from any geographical area. Studies whose participants were registered health and social care practitioners and postgraduate students were excluded.

We planned to include studies that were published between 1996 and June 2019. No limit was placed on the language of publication.

1.5. What are the main findings of this review?

A total of 45 full‐text articles on evidence‐based practice educational interventions and one full‐text article on evidence‐informed practice educational intervention were screened for their eligibility for inclusion. However, we identified no studies examining the relative effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice versus evidence‐based practice educational interventions. As a result, we are unable to answer the question as to which of the two concepts better facilitates the application of evidence into healthcare practice.

1.6. What do the findings of this review mean?

Whilst evidence suggests that evidence‐informed practice can be effective (compared to a no‐intervention control) in improving student outcomes, we are unable to conclude which approach better facilitates the application of evidence into practice.

1.7. How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies published up to June 2019.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. Description of the condition

Over the past three decades, there has been increasing attention on improving healthcare quality, reliability, and ultimately, patient outcomes, through the provision of healthcare that is influenced by the best available evidence, and devoid of rituals and tradition (Andre et al., 2016; Melnyk et al., 2014; Sackett et al., 1996). There is an expectation by professional regulators such as the Nursing and Midwifery Council, United Kingdom (Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2015) and the Health and Care Professions Council (Health and Care Professions Council, 2012) that the professional, as part of their accountability applies the best available evidence to inform their clinical decision‐making, roles, and responsibilities. This is imperative for several reasons. First, it enhances the delivery of healthcare and improves efficiency. Second, it produces better intervention outcomes and promotes transparency. Third, it enhances co‐operation and knowledge sharing among professionals and service users, and ultimately, the effective application of evidence into practice improves patient outcomes and enhances job satisfaction. Indeed, the need to guide healthcare practice with evidence has been emphasized by several authors, including Kelly et al. (2015), Nevo and Slonim‐Nevo (2011), Scott and Mcsherry (2009), Shlonsky and Stern (2007), Smith and Rennie (2014) Straus et al. (2011), Tickle‐Degnen and Bedell (2003), and Sackett et al. (1996). According to these authors, the effective and consistent application of evidence into practice helps practitioners to deliver the best care to their patients and patient relatives.

Two main concepts have been associated with the application of evidence into healthcare practice: “evidence‐based practice” and “evidence‐informed practice.” Evidence‐based practice is an offshoot of evidence‐based medicine; hence, the universally accepted definition of evidence‐based practice is adapted from the definition of evidence‐based medicine, which is “the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of the best evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient” (Sackett et al., 1996, p. 71). Evidence‐informed practice, on the other hand, is defined as the assimilation of professional judgment and research evidence regarding the efficiency of interventions (McSherry et al., 2002). This definition was further elaborated by Nevo and Slonim‐Nevo, 2011 as an approach to patient care where:

Practitioners are encouraged to be knowledgeable about findings coming from all types of studies and to use them in an integrative manner, taking into consideration clinical experience and judgment, clients' preferences and values, and context of the interventions (p. 18).

The primary aim of both evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice is to facilitate the application of evidence into healthcare practice. However, there are significant differences between the two concepts. These differences are discussed in detail in the ensuing sections. Nonetheless, it is important to note here that a characteristic difference between evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice is the processes involved in applying the concepts. Evidence‐based practice provides a step‐wise approach to the application of evidence into practice, where practitioners are required to follow a series of steps to implement evidence‐based practice. According to Sackett (2000), the core steps of evidence‐based practice include: (1) formulating a clinical question, (2) searching the literature for the best research evidence to answer the question, (3) critically appraising the research evidence, (4) integrating the appraised evidence with own clinical expertise, patient preferences, and values, and (5) evaluating outcomes of decision‐making.

Evidence‐informed practice, on the other hand, offers an integrated, all‐inclusive approach to the application of evidence into practice (Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011). As illustrated by McSherry (2007), evidence‐informed practice provides a systems‐based approach (made up of input, throughput, and output) to applying evidence into practice, which contains, as part of its elements, the steps of evidence‐based practice. Besides, unlike evidence‐based practice, the main process involved in the implementation of evidence‐informed practice is cyclical and interdependent (McSherry et al., 2002).

Evidence‐based practice is a well‐established concept in health and social care (Titler, 2008) and is regarded as the norm for the delivery of efficient healthcare service. In recent times, however, the concept of evidence‐informed practice is often used instead of evidence‐based practice. For example, in countries such as Canada, the term has been widely adopted and is used more often in the health and social care fields. This was reflected in a position statement by the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA, 2008) and the Canadian Physiotherapy Association (Canadian Physiotherapy Association, 2017), where healthcare practitioners, including nurses, clinicians, researchers, educators, administrators, and policy‐makers were encouraged to collaborate with other stakeholders to enhance evidence‐informed practice, to ensure integration of the healthcare system. In the United Kingdom, the term evidence‐informed practice has been extensively adopted in the field of education, with a lot of resources being invested to assess the progress toward evidence‐informed teaching (Coldwell et al., 2017). In addition, an evidence‐informed chartered college of teaching has been launched (Bevins et al., 2011) to ensure evidence‐informed teaching and learning.

Whilst evidence‐based practice has been considered the gold standard for effective healthcare delivery, a large majority of healthcare practitioners continue to encounter multiple difficulties, which inhibit the rapid application of evidence into practice (Epstein, 2009; Glasziou, 2005; Greenhalgh et al., 2014; McSherry, 2007; McSherry et al., 2002; Melnyk, 2017; Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011). This has generated an on‐going international debate as to whether the term “evidence‐based practice” should be replaced by “evidence‐informed practice,” and which of the two concepts best facilitate the effective and consistent application of evidence into practice. Researchers, such as Melnyk (2017), Melnyk and Newhouse (2014), and Gambrill (2010) believe that knowledge and skills in evidence‐based practice help the healthcare professional to effectively apply evidence into practice. Conversely, Epstein (2009), Nevo and Slonim‐Nevo (2011), and McSherry (2007) have argued the need to equip healthcare professionals with the necessary knowledge and skills of evidence‐informed practice to facilitate the effective and consistent application of evidence into practice. According to Nevo and Slonim‐Nevo (2011), the application of evidence into practice should, in principle be “informed by” evidence and not necessarily “based on” evidence. This suggests that decision‐making in healthcare practice “might be enriched by prior research but not limited to it” (Epstein, 2009, p. 9).

It is imperative that healthcare training institutions produce graduates who are equipped with the knowledge and skills necessary for the effective and consistent application of evidence into practice (Dawes et al., 2005; Frenk et al., 2010; Melnyk, 2017). Hence, healthcare training institutions are required to integrate the principles and processes involved in the application of evidence into undergraduate health and social care curricula. However, the question that often arises is: which of the two concepts (i.e., evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice) best facilitates the application of evidence into practice? While Melnyk et al. (2010) have suggested a seven‐step approach to the application of evidence into practice (termed the “evidence‐based practice model”), as stated earlier, McSherry (2007) has argued that the principle involved in the application of evidence into practice is a systems‐based approach, with an input, throughput and an output (named the “evidence‐informed practice model”).

The main purpose of this systematic review was to determine the differences and similarities, if any, between evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions; as well as explore the role each concept plays in the application of evidence into practice. In addition, the present review aimed at determining whether the two concepts act together, or individually to facilitate the effective application of evidence into practice. We hoped to achieve these aims by reviewing published and unpublished primary papers that have evaluated and compared the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice educational interventions with evidence‐based practice educational interventions targetted at improving undergraduate pre‐registration health and social care students' knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior regarding the application of evidence into practice.

2.2. Description of the intervention

The gap between evidence and healthcare practice is well acknowledged (Lau et al., 2014; Melnyk, 2017; Straus et al., 2009). Difficulties in using evidence to make decisions in healthcare practice are evident across all groups of decision‐makers, including health care providers, policymakers, managers, informal caregivers, patients, and patient relatives (Straus et al., 2009). Consequently, several interventions have been developed to improve the implementation of evidence into healthcare practice and policy. Specifically, evidence‐based practice educational interventions are widely used and have been greatly evaluated (e.g., Callister et al., 2005; Dawley et al., 2011; Heye & Stevens, 2009; Schoonees et al., 2017; and Goodfellow, 2004). Evidence‐informed practice educational interventions have also been used (e.g., Almost et al., 2013), although to a much smaller extent. Conducting a systematic review of currently available research offers a rigorous process for evaluating the comparative effectiveness of both evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions.

Dawes et al. (2005) and Tilson et al. (2011 have each reported on Sicily statements, which have been made about the need for developing educational interventions on evidence‐based practice in healthcare. The statements were made separately in the “Evidence‐Based Healthcare Teachers and Developers” conference held in 2003 (Dawes et al., 2005) and 2009 (Tilson et al., 2011). The statements provide suggestions for evidence‐based practice competencies, curricula, and evaluation tools for educational interventions. All health and social care students and professionals are required to understand the principles of evidence‐based practice, to have a desirable attitude toward evidence‐based practice, and to effectively implement evidence‐based practice (Dawes et al., 2005). To incorporate a culture of evidence‐based practice among health and social care students, Melnyk (2017) believes undergraduate health and social care research modules need to be based on the seven‐step model of evidence‐based practice that was developed by Melnyk et al. (2010). In addition, the curricula should include learning across the four components of evidence‐based practice, namely, knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and practice (Haggman‐Laitila et al., 2016).

Tilson et al. (2011) identified major principles for the design of evidence‐based practice evaluation tools for learners. Among the identified categories for evaluating evidence‐based practice educational interventions include the learner's knowledge of, and attitudes regarding evidence‐based practice, the learner's reaction to the educational experience, behavior congruent with evidence‐based practice as part of patient care, as well as skills in implementing evidence‐based practice. According to Tilson et al. (2011), frameworks used in assessing the effectiveness of evidence‐based practice interventions need to reflect the aims of the research module, and the aims must also correspond to the needs and characteristics of learners. For example, students may be expected to perform the seven‐steps of evidence‐based practice, whilst health practitioners may be required to acquire skills in applying evidence into practice. Tilson et al. (2011) also stated that the setting where learning, teaching, and the implementation of evidence‐based practice occur needs to be considered.

Evidence‐informed practice, on the other hand, extends beyond the initial definitions of evidence‐based practice (LoBiondo‐Wood et al., 2013) and is more inclusive than evidence‐based practice (Epstein, 2009). This is due to the following reasons. First, evidence‐informed practice recognizes practitioners as critical thinkers and encourages them to be knowledgeable about findings from all types of research (including systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), qualitative research, quantitative research, and mixed methods), and to utilize them in an integrative manner. Second, evidence‐informed practice considers the best available research evidence, practitioner knowledge and experience, client preferences and values, and the clinical state and circumstances (Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011). However, Melnyk and Newhouse, 2014 (p. 347) disagreed with this assertion as a difference between the two concepts. According to the authors, like evidence‐informed practice, evidence‐based practice has broadened to “integrate the best evidence for well‐designed studies and evidence‐based theories (i.e., external evidence) with a clinician's expertise, which includes internal evidence gathered from a thorough patient assessment and patient data, and a patient's preferences and values.” Although this statement may be true, the existing evidence‐based practice models (e.g., DiCenso et al., 2005; Dufault, 2004; Greenhalgh et al., 2005; Melnyk et al., 2010; Titler et al., 2001) place too much emphasis on the scientific evidence in clinical decision‐making, and give little or no attention to the other forms of evidence such as the clinical context, patient values and preferences, and practitioner's knowledge and experiences (McTavish, 2017; Miles & Loughlin, 2011).

Inasmuch as scientific evidence plays a major role in clinical decision‐making, the decision‐making process must be productive and adaptable enough to meet the on‐going changing condition and needs of the patient, as well as the knowledge and experiences of the health practitioner (LoBiondo‐Wood et al., 2013; Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011). Hence, researchers, including Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011 and McSherry, 2007, have advocated for a creative and flexible model of applying evidence into practice, where healthcare practitioners are not limited to following a series of steps (as advocated in evidence‐based practice) to apply evidence into practice. Third, unlike evidence‐informed practice, evidence‐based practice uses a formal hierarchy of research evidence, which ranks certain forms of evidence (e.g., systematic reviews and RCTs) higher than others (such as qualitative research and observational studies). Instead of the hierarchy of research evidence, proponents of evidence‐informed practice support an integrative model of practice that considers all forms of studies and prefers the evidence that provides the best answer to the clinical question (Epstein, 2009). Therefore, in place of the hierarchy of research evidence, Epstein, 2011 suggested a “wheel of evidence,” where “all forms of research, information gathering, and interpretations would be critically assessed but equally valued” (p. 225). This will ensure that all forms of evidence are considered during decision‐making in healthcare practice.

Evidence‐informed practice does not follow a stepwise approach to applying evidence into practice. According to McSherry (2007), the actual process involved in applying evidence into practice occurs in a cyclical manner, termed the evidence‐informed cycle. Similarly, Epstein (2009) described evidence‐informed practice as an integrative model that “accepts the positive contributions of evidence‐based practice, research‐based practice, practice‐based research, and reflective practice” (p. 223). Epstein (2009)'s integrative model of evidence‐informed practice is presented in the form of a Venn diagram, which highlights the commonalities and intersections among the concepts. Likewise, Moore (2016) believes evidence‐informed practice is an integration of three components, namely, evidence‐based programs, evidence‐based processes, and client and professional values. According to Moore (2016), these sources of evidence need to be blended in practice to achieve optimal person‐centered care.

Thus, an evidence‐informed practice educational intervention needs to recognize the learner as a critical thinker who is expected to consider various types of evidence in clinical decision‐making (Almost et al., 2013; McSherry et al., 2002). One is not expected to be a researcher to effectively implement evidence‐informed practice. Rather, McSherry et al. (2002) argue that the healthcare professional must be aware of the various types of evidence (such as the context of care, patient preferences, and experience, as well as the professional's own skills and expertise), not just research evidence, to deliver person‐centered care. Table 1 presents a summary of the differences and similarities between evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the differences and similarities between evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice

| Evidence‐based practice | Evidence‐informed practice | Similarities between evidence‐based practice and evidence‐informed practice |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence‐based practice adopts a “cook‐book” approach to applying evidence into practice, and so leaves no room for flexibility (Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011). | Evidence‐informed practice recognizes practitioners as critical thinkers (McSherry, 2007; Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011), and encourages them to be creative and to consider the clinical state and circumstances when making patient care decisions. | Both evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice are approaches for making informed clinical decisions (Woodbury & Kuhnke, 2014) |

| Both evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice integrate research with patient values and preferences and clinical knowledge and expertise (Melnyk & Newhouse, 2014) | ||

| The existing evidence‐based practice models (e.g., DiCenso et al., 2005; Dufault, 2004; Greenhalgh et al., 2005; Melnyk et al., 2010; Titler et al., 2001) rely heavily on scientific evidence, when making clinical decisions, and give little attention to other forms of evidence such as the clinical context, patient values and preferences, and practitioner's knowledge and experiences (McTavish, 2017; Miles & Loughlin, 2011) | The existing evidence‐informed practice models (e.g., McSherry, 2007; Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011) are innovative and flexible. The client is at the centre not the evidence (McTavish, 2017). One is not expected to be a researcher in order to effectively implement evidence‐informed practice; the healthcare professional must be aware of the various types of evidence, such as the context of care, patient preferences and experience, as well as the clinician's skills and expertise, not just research evidence, in order to deliver effective person‐centred care. | |

| Evidence‐based practice uses a formal hierarchy of research evidence, which ranks certain forms of research evidence (e.g., systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials) higher than others (such as qualitative research and observational studies). | Instead of the hierarchy of research evidence, evidence‐informed practice supports an integrative model of practice that considers all forms of research evidence (including, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, qualitative research, quantitative research and mixed methods), and prefers the evidence that provides the best answer to the clinical question (Epstein, 2009). | |

| The existing models of Evidence‐based practice adopt a stepwise approach to applying evidence into healthcare practice. | Evidence‐informed practice is an integrative (McTavish, 2017) and a systems‐based approach to applying evidence into practice, which comprises of an input, throughput and an output (McSherry, 2007) | |

| The linear approach of evidence‐based practice does not allow health practitioners to be creative enough, so as to meet the on‐going changing needs and conditions of the patient and the healthcare setting. | Evidence‐informed practice is adaptable, and considers the complexities of health and healthcare delivery (LoBiondo‐Wood et al., 2013; Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011). The evidence‐informed practice model considers several factors, such as the factors that influence research utilization (including workload, lack of organizational support, and time) in clinical decision‐making (McSherry, 2007). |

Though several models of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice exist, our operational definitions for evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions were based on McSherry (2007)'s model of evidence‐informed practice and Melnyk et al. (2010)'s model of evidence‐based practice, respectively. The following operational definitions were applied:

Evidence‐informed practice educational interventions referred to any formal educational program that facilitates the application of the principles of the evidence‐informed practice model developed by McSherry (2007). The evidence‐informed practice model (Figure 1), as developed by McSherry (2007) is a systems‐based model comprising input (e.g., roles and responsibilities of the health practitioner) throughput (i.e., research awareness, application of knowledge, informed decision‐making, evaluation), and output, which is an empowered professional who is a critical thinker and doer (McSherry, 2007).

Figure 1.

Evidence‐informed practice model

Evidence‐based practice educational interventions referred to any formal educational program that enhances the application of the principles of the evidence‐based practice model developed by Melnyk et al. (2010). The evidence‐based practice model developed by Melnyk et al. (2010) comprises a seven‐step approach to the application of evidence into practice. These are (1) to cultivate a spirit of inquiry (2) ask a clinical question (3) search for the best evidence to answer the question (4) critically appraise the evidence (5) integrate the appraised evidence with own clinical expertise and patient preferences and values (6) evaluate the outcomes of the practice decisions or changes based on evidence and (7) disseminate evidence‐based practice results (Melnyk et al., 2010).

In this systematic review, it was not a requirement for eligible studies to mention specifically Melnyk et al. (2010)'s model of evidence‐based practice or McSherry (2007)'s model of evidence‐informed practice as the basis for the development of their educational program. However, for a study to be eligible for inclusion, it was planned that the content of its educational program(s) must include some, if not all, of the elements and/or principles of the aforementioned models.

In addition, definitions for “knowledge,” “attitudes,” “understanding,” and “behavior” were based on the Classification Rubric for Evidence‐based practice Assessment Tools in Education (CREATE) created by Tilson et al. (2011). These are provided below.

Knowledge referred to learners' retention of facts and concepts about evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice. Hence, assessments of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice knowledge might assess a learner's ability to define evidence‐based practice and evidence‐informed practice concepts, list their basic principles, or describe levels of evidence.

Attitudes referred to the values ascribed by the learner to the importance and usefulness of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice to inform clinical decision‐making.

Understanding referred to learners' comprehension of facts and concepts about evidence‐based practice and evidence‐informed practice.

Behavior referred to what learners actually do in practice. It is inclusive of all the processes that a learner would use in the implementation of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice, such as assessing patient circumstances, values, preferences, and goals along with identifying the learners' own competence relative to the patient's needs to determine the focus of an answerable clinical question.

We planned that the mode of delivery of the educational program could be in the form of workshops, seminars, conferences, journal clubs, and lectures (both face‐to‐face and online). It was anticipated that the content, manner of delivery, and length of the educational program may differ in each of the studies that were to be included as there is no standard evidence‐informed practice/evidence‐based practice educational program. Evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions that are targeted toward health and social care postgraduate students or registered health and social care practitioners were excluded.

2.3. How the intervention might work

Most efforts to apply evidence into healthcare practice have either been unsuccessful or partially successful (Christie et al., 2012; Eccles et al., 2005; Grimshaw et al., 2004; Lechasseur et al., 2011; McTavish, 2017). The resultant effects include ineffective patient outcomes, reduced patient safety, reduced job satisfaction, and increased rate of staff turnover (Adams, 2009; Fielding & Briss, 2006; Huston, 2010; Knops et al., 2009; Melnyk & Fineout‐Overholt, 2005; Schmidt & Brown, 2007). Consequently, a lot of emphases have been placed on integrating evidence‐based practice (Masters, 2009; Melnyk, 2017; Scherer & Smith, 2002; Straus et al., 2005) and/or evidence‐informed practice competencies (Epstein, 2009; McSherry, 2007; McSherry et al., 2002; Nevo & Slonim‐Nevo, 2011) into undergraduate health and social care curricula. Yet, it remains unclear the exact components of an evidence‐based practice/evidence‐informed practice educational intervention. Healthcare educators continue to encounter challenges with regard to finding the most efficient approach to preparing health and social care students toward the application of evidence into practice (Almost et al., 2013; Flores‐ Mateo & Argimon, 2007; Oh et al., 2010; Straus et al., 2005). This has resulted in an increase in the rate and number of research investigating the effectiveness of educational interventions for enhancing knowledge, attitudes, and skills regarding, especially, evidence‐based practice (Phillips et al., 2013). There is also empirical evidence (primary studies) to support a direct link between evidence‐based practice/evidence‐informed practice educational interventions and knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior, which in turn may have a positive impact on the application of evidence into practice. However, participants in most of the studies reviewed were nursing students. Some examples are given below.

Ashtorab et al. (2014) developed an evidence‐based practice educational intervention for nursing students and assessed its effectiveness, based on Rogers' diffusion of innovation model (Rogers, 2003). The authors concluded that evidence‐based practice education grounded on Roger's model leads to improved attitudes, knowledge, and adoption of evidence‐based practice. According to the authors, Rogers' diffusion of innovation model contains all the important steps that need to be applied in the teaching of evidence‐based practice.

Heye and Stevens (2009) developed an evidence‐based practice educational intervention and assessed its effectiveness on 74 undergraduate nursing students, using the Academic Center for Evidence‐based practice (ACE) Star model of knowledge transformation (Stevens, 2004). The ACE star model describes how evidence is progressively applied to healthcare practice by transforming the evidence through various stages (including translation, integration, evaluation, discovery, and summary).

Heye and Stevens (2009) indicated that the students who participated in the educational program gained research appraisal skills and knowledge in evidence‐based practice. Furthermore, the authors reported that the students acquired evidence‐based practice competencies and skills that are required for the work environment.

Several other studies have reported on the effectiveness of evidence‐based practice educational interventions and their underpinning theoretical foundations: the Self‐directed learning strategies (Fernandez et al., 2014; Kruszewski et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012), the Constructivist Model of learning (Fernandez et al., 2014), Bandura's self‐efficacy theory (Kim et al., 2009), as well as the Iowa model of evidence‐based practice (Kruszewski et al., 2009). Nonetheless, research in the area of evidence‐informed practice educational interventions has been limited. Almost et al. (2013) developed an educational intervention aimed at supporting nurses in the application of evidence‐informed practice. Before developing the intervention, the authors conducted interviews to examine the scope of practice, contextual setting, and learning needs of participants. A Delphi survey was then conducted to rank learning needs, which were identified by the interview participants, to select the key priorities for the intervention. The authors then conducted a pre and post‐survey, before the intervention and six months after the intervention, respectively, to assess the impact of the intervention. Thus, the development of the intervention was learner‐directed, which reaffirms McSherry (2007)'s description of the evidence‐informed practitioner as a critical thinker and doer. Unlike evidence‐based practice, practice knowledge and intervention decisions regarding evidence‐informed practice are enriched by previous research but not limited to it. In this way, evidence‐informed practice is more inclusive than evidence‐based practice (Epstein, 2009 p. 9). Nevo and Slonim‐Nevo (2011) argue that rather than focusing educational interventions on the research‐evidence dominated steps of evidence‐based practice, research findings should be included in the intervention process, but the process itself must be creative and flexible enough to meet the continually changing needs, conditions, experiences, and preferences of patients and health professionals.

A logic model has been presented in Figure 2 to indicate the connection between evidence‐based practice/evidence‐informed practice educational intervention and outcomes.

Figure 2.

Logic model

2.4. Why it is important to do this review

Despite the seeming confusion surrounding the terms “evidence‐informed practice” and “evidence‐based practice,” together with the on‐going debate in the literature as to which concept leads to better patient outcomes, no study, to the best of the researchers' knowledge, has compared through a systematic review, the effects of the two concepts on the effective implementation of evidence into practice. A review of the literature reveals several systematic reviews conducted on evidence‐based practice educational interventions and the effects of such interventions. Examples of such systematic reviews are described below.

Young et al. (2014) conducted an overview of systematic reviews that evaluated interventions for teaching evidence‐based practice to healthcare professionals (including undergraduate students, interns, residents, and practicing healthcare professionals). Comparison interventions in the study were no intervention or different strategies. The authors included 15 published and 1 unpublished systematic reviews. The outcome criteria included evidence‐based practice knowledge, critical appraisal skills, attitudes, practices, and health outcomes. In many of the included studies, however, the focus was on critical appraisal skills. The systematic reviews that were reviewed used a number of different educational interventions of varying formats (e.g., lectures, online teaching, and journal clubs), content, and duration to teach the various component of evidence‐based practice in a range of settings. The results of the study indicated that multifaceted, clinically integrated interventions (e.g., lectures, online teaching, and journal clubs), with assessment, led to improved attitudes, knowledge, and skills toward evidence‐based practice. The majority of the included systematic reviews reported poorly the findings from the source studies, without reference to significant tests or effect sizes. Moreover, the outcome criteria (e.g., knowledge, skills, attitudes, practices, and health outcomes) were described narratively as improved or not, with the use of vote counting.

Coomarasamy and Khan (2004) conducted a systematic review to evaluate the effects of standalone versus clinically integrated teaching in evidence‐based medicine on postgraduate healthcare students' knowledge, critical appraisal skills, attitudes, and behavior. The results indicated that standalone teaching improved knowledge, but not skills, attitudes, or behavior. Clinically integrated teaching, however, improved knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behavior. A similar systematic review by Flores‐ Mateo and Argimon (2007) identified a small significant improvement in postgraduate healthcare students' skills, knowledge, behavior, and attitudes after participating in evidence‐based practice interventions. Furthermore, a systematic review of the literature has been conducted to identify the effectiveness of evidence‐based practice training programs and their components for allied health professionals (Dizon et al., 2012). The researchers reported that irrespective of the allied health discipline, there was consistent evidence of significant changes in knowledge and skills among health practitioners, after participating in an evidence‐based practice educational program. In addition, recently, a systematic review has been conducted by Rohwer et al. (2017) to assess the effectiveness of e‐learning of evidence‐based practice on increasing evidence‐based practice competencies among healthcare professionals (medical doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, physician assistants, and athletic trainers). The results showed that pure e‐learning compared to no learning led to an improvement in knowledge as well as attitudes regarding evidence‐based practice among the various professional groups.

Yet, according to a comprehensive literature review, no specific systematic review has been conducted on evidence‐informed practice educational interventions and the effects of such interventions on the knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior of undergraduate health and social care students. Two reviews (conducted by McCormack et al., 2013, and Yost et al., 2015) on evidence‐informed practice interventions were identified in the literature. However, these reviews focused on “change agency” and “knowledge translation” as interventions in improving evidence‐informed practice. For example, McCormack et al. (2013) conducted a realist review of strategies and interventions to promote evidence‐informed practice, but the authors focused only on “change agency” as an intervention aimed at improving the efficiency of the application of evidence. Also, a systematic review by Yost et al. (2015) concentrated on the effectiveness of knowledge translation on evidence‐informed decision‐making among nurses. Moreover, a relatively recent systematic review by Sarkies et al. (2017) focused on evaluating the effectiveness of research implementation strategies for promoting evidence‐informed policy and management decisions in healthcare. The authors also described factors that are perceived to be associated with effective strategies and the correlation between these factors. Nineteen papers (research articles) were included in Sarkies et al. (2017)'s review. The results revealed a number of implementation strategies that can be used in promoting evidence‐informed policy and management in healthcare. The strategies included workshops, knowledge brokering, policy briefs, fellowship programs, consortia, literature reviews/rapid reviews, multi‐stakeholder policy dialogue, and multifaceted strategies. It is important to note that these strategies, though relevant, are more linked to healthcare management and policy decisions rather than typical patient care decision‐making/healthcare practice, which is the focus of the present systematic review.

This systematic review offers originality and is significantly different from previously conducted systematic reviews in three ways. First, this review focused on pre‐registration undergraduate health and social care students as opposed to only nursing students, nurses, or health care professionals. Second, the current review assessed the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice educational interventions, while recent studies by Rohwer et al. (2017) and Yost et al. (2015) assessed the effectiveness of e‐learning of evidence‐based health care and the effectiveness of knowledge translation on evidence‐informed decision‐making, respectively. Third, this systematic review focused on comparing the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice to evidence‐based practice educational interventions on undergraduate pre‐registered health and social care students' knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior regarding the application of evidence into practice. The current review also aimed to determine whether evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice act together, or individually to facilitate the application of evidence into practice.

By conducting a comprehensive systematic review of the literature that specifically compares the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice to evidence‐based practice educational interventions on undergraduate health and social care students, we hoped to review and analyze current evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice approaches in higher education settings. In addition, we hoped that the results of this systematic review would help to determine the relative effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions, as well as identify gaps in the current literature. We hoped to be able to offer direction for practice, policy, and future inquiry in this growing area of research and practice.

3. OBJECTIVES

The primary objective of this systematic review is as follows.

To evaluate and synthesize literature on the relative effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions for improving knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior of undergraduate pre‐registration health and social care students regarding the application of evidence into practice.

Specifically, the review aimed to address the following research questions:

-

1.

Is there a difference (i.e., difference in content, outcome) between evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions?

-

2.

Does participating in evidence‐informed practice educational interventions relative to evidence‐based practice educational interventions facilitate the application of evidence into practice (as measured by, for example, self‐reports on effective application of evidence into practice)?

-

3.

Do both evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions targeted at undergraduate health and social care students influence patient outcomes (as measured by, e.g., reduced morbidity and mortality, absence of nosocomial infections)?

-

4.

What factors affect the impact of evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions (as measured by, e.g., course content, mode of delivery, multifaceted interventions, standalone intervention)?

4. METHODS

4.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

4.1.1. Types of studies

This review followed standard procedures for conducting and reporting systematic literature reviews. The protocol for this systematic review (Kumah et al., 2019) was published in July 2019. The protocol is available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/cl2.1015.

In this review, we intended to include both qualitative and quantitative primary studies (a mixed‐methods systematic review) that compared evidence‐informed practice educational interventions with evidence‐based practice educational interventions.

We planned to include quantitative primary studies that used both experimental and epidemiological research designs such as RCTs, non‐RCTs, quasi‐experimental, before and after studies, prospective and retrospective cohort studies.

We also planned to include qualitative primary studies that had used descriptive epidemiological study designs. Examples include case series, individual case reports, descriptive cross‐sectional studies, focus groups, and interviews. Furthermore, we intended to include primary studies that have used qualitative approaches such as ethnography, phenomenology, and grounded theory. We planned to discuss the biases and limitations associated with any included study design in relation to the impact it may have on the effectiveness of the intervention.

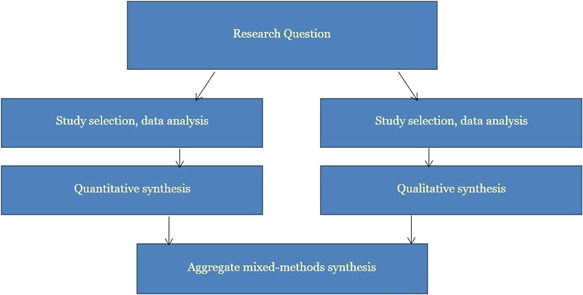

For the primary analysis, the intention was to follow the recommended steps by Sandelowski et al. (2012): to first conduct two separate syntheses for included quantitative and qualitative primary studies. We planned to synthesize qualitative studies by way of meta‐aggregation and quantitative studies by way of meta‐analysis (Lockwood et al., 2015). We planned to then integrate the results of the two separate syntheses by means of an aggregative mixed‐methods synthesis. We intended to integrate the two results (i.e., qualitative and quantitative results) by translating findings from the quantitative synthesis into qualitative statements, by the use of Bayesian conversion (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2014). Figure 3 presents the mixed‐methods approach we intended to employ in this systematic review.

Figure 3.

Summary of mixed‐methods strategy to be employed

4.1.2. Types of participants

We intended to include undergraduate pre‐registration health and social care students in higher education (University) from any geographical area. We planned to include undergraduate pre‐registration students studying health and social care programs such as nursing, midwifery, dental hygiene, and dental therapy, dental nurse practice, diagnostic radiography, occupational therapy, operating department practice studies, paramedic practice, social work, and physiotherapy.

We planned to exclude studies whose participants were registered health and social care practitioners and postgraduate students.

4.1.3. Types of interventions

The intention was to include primary studies that evaluate and compare any formal evidence‐based practice educational intervention with evidence‐informed practice educational interventions aimed at improving undergraduate pre‐registration health and social care students' knowledge, attitudes, understanding, and behavior regarding the application of evidence into healthcare practice. Such interventions may be delivered via either workshops, seminars, conferences, journal clubs, or lectures (both face‐to‐face and online).

Specifically, we planned to include any formal educational intervention that incorporates any or all of the principles and elements of McSherry (2007)'s evidence‐informed practice model and Melnyk et al., 2010's evidence‐based practice model. It was not a requirement for eligible studies to mention specifically Melnyk et al. (2010)'s model of evidence‐based practice or McSherry (2007)'s model of evidence‐informed practice as the basis for the development of their educational program. However, we planned that for a study to be eligible, the content of its educational program must include some, if not all, of the elements and/or principles of the models. We anticipated that the content, manner of delivery, and length of the educational program may differ in eligible studies as there is no standard evidence‐informed practice/evidence‐based practice educational program.

Evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice educational interventions that are targeted at health and social care postgraduate students or registered health and social care practitioners were excluded. We intended to include, as comparison conditions, educational interventions that do not advance the teaching of the principles and processes of evidence‐informed practice, and/or evidence‐based practice in healthcare.

4.1.4. Types of outcome measures

Outlined below are the primary and secondary outcome measures for this systematic review

Primary outcomes

-

1.

Participants' knowledge about evidence‐informed practice and/or evidence‐based practice.

-

2.

Participants' understanding of evidence‐informed practice and/or evidence‐based practice.

-

3.

Participants' attitudes toward evidence‐informed practice and/or evidence‐based practice.

-

4.

Participants' behavior toward evidence‐informed practice and evidence‐based practice.

Since there is no uniform tool for evaluating the effectiveness of evidence‐based practice and evidence‐informed practice educational interventions, we planned that measurement of the above outcomes may be conducted using standardized or unstandardized instruments. Some examples of these instruments include:

the use of a standardized questionnaire to evaluate knowledge, attitude, understanding, and behavior toward the application of evidence into practice. Examples of such questionnaires include (1) the Evidence‐Based Practice Belief (EBPB) and Evidence‐Based Practice Implementation (EBPI) scales developed by Melnyk et al. (2008). The EBPB scale is a 16‐item questionnaire that allows measurement of an individual's belief about the values of evidence‐based practice and the ability to implement evidence‐based practice, whereas the EBPI scale is an 18‐item questionnaire that evaluates the extent to which evidence‐based practice is implemented, (2) the use of pre and post validated instruments such as the Berlin test (Fritsche et al., 2002) to measure changes in knowledge, and (3) the use of Likert scale questions to measure changes in attitudes before and after the intervention.

unstandardized instruments include self‐reports from study participants and researcher‐administered measures.

Secondary outcomes

The intention was to include studies that measure the impact of evidence‐informed practice and/or evidence‐based practice educational programs on patient outcomes. We planned to assess patient outcome indicators such as user experience, length of hospital stays, absence of nosocomial infections, patient and health practitioner satisfaction, mortality, and morbidity rates.

Duration of follow‐up

No limit was placed on the duration of follow‐up. The rationale was to give room for studies with either short‐ or long‐term follow‐up duration to be eligible for inclusion.

Types of settings

We intended to include primary studies from any geographical area. However, due to language translation issues, we planned to include only studies written in English. We also planned that studies whose title and abstracts are in English and meet the inclusion criteria, but the full article is reported in another language would be included, subject to the availability of translation services.

Time

To qualify for inclusion in this systematic review, studies must have been published during the period from 1996 (the date when evidence‐based practice first emerged in the literature) (Closs & Cheater, 1999; Sackett et al., 1996), to the date when the literature search was concluded (June 17, 2019).

4.2. Search methods for identification of studies

4.2.1. Search terms and keywords

We used a combination of keywords and terms related to the population, intervention, outcome, and study design to conduct the search. Specific strategies for each database were explored, such as the use of Boolean operators (e.g., OR, AND), wildcards (such as?), phrase operators (e.g. “”), and truncations (including *). This was done to ensure search precision and sensitivity. In addition, we used three sets of terms for the search strategy: the population, intervention(s), and outcomes. We used limiting commands to narrow the results by date and type of study design. The search was limited to studies published from 1996, which is the year when evidence‐based practice first emerged in the literature. No limit was placed on the language of publication, however, due to language translation issues, eligible studies whose full texts were not in English might have been included only if there were available language translation facilities.

Below are examples of the search terms used in the current review:

Targeted population: nurs* OR physio* OR “occupa* therap*” OR “dental Hygiene” OR “undergraduate healthcare student*” OR “undergraduate social care student*” OR baccalaureat* OR “social work” OR dent* OR BSc OR student* OR “higher education” OR “undergrad* nurs* student*”

Intervention: evidence‐informed* OR evidence‐based* OR “evidence‐informed practice” OR “evidence‐based practice” OR EBP OR EIP OR “evidence‐informed practice education” OR “evidence‐based practice education” OR “evidence into practice” OR evidence‐informed near. practice teaching learning OR evidence‐based near. practice teaching learning

Outcomes: “knowledge, attitudes, understanding and behavio* regarding EBP” OR “knowledge near. attitudes understanding behavio* regarding EIP OR “Knowledge of evidence‐informed*” OR “knowledge of evidence‐based*” OR “patient outcome*” OR outcome*

Study design/type: trial* OR “randomi?ed control trial” OR “qua?i‐experiment*” OR random OR experiment OR “control* group*” OR program OR intervention OR evaluat* OR qualitative OR quantitative OR ethnograpy OR “control* study” OR “control* studies” OR “control* design*” OR “control* trial*” OR “control group design” OR RCT OR rct OR “trial registration”

4.2.2. Management of references

We exported the full set of search results directly into an Endnote X9 Library. Where this was not possible, search results were manually entered into the Endnote Library. The Endnote library made it easier to identify duplicates and manage references.

4.2.3. Search strategy

The search to identify eligible studies was initially carried out in June 2018, and then a repeat search was conducted in June 2019. We utilized a number of strategies, to identify published and unpublished studies that meet the inclusion criteria described above. These strategies are outlined below.

Electronic searches

The following electronic searches were conducted to identify eligible studies.

-

1.

An electronic database search was conducted using the following databases.

Academic Search complete

Academic search premier

AMED

Australian education index

British education index

Campbell systematic reviews

Canada bibliographic database (CBCA Education)

CINAHL

Cochrane Library

Database of Abstracts of Reviews on Effectiveness

Dissertation Abstracts International

Education Abstracts

Education complete

Education full text: Wilson

ERIC

Evidence‐based program database

JBI database of systematic reviews

Medline

PsycInfo

Pubmed

SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online)

Scopus

Supporting Information Appendix 1 presents the search strategy for the MEDLINE database searched on the EBSCOhost platform. We modified the search terms and strategies for the different databases.

-

2.

A web search was conducted using the following search engines.

Google

Google Scholar

-

3.

A gray literature search was conducted using the following databases.

OpenGrey (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe)

System for information on Grey Literature

The Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness

Virginia Henderson Global Nursing e‐Repository

Searching other resources

The following strategies were also used to identify eligible studies.

Hand searching: the table of contents of three journals were hand‐searched for relevant studies. The journals include the Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing Journal, the British Medical Journal, and the British Journal of Social Work.

Tracking bibliographies of previously retrieved studies and literature reviews: we screened the reference list of previously conducted systematic reviews, meta‐analysis, and primary studies for relevant studies.

4.3. Data collection and analysis

4.3.1. Selection of studies

First, we exported search results from the various databases and search engines into an Endnote X9 software. Second, we searched for and removed duplicates using the Endnote software. Third, we exported search results from Endnote into Covidence (a web‐based software platform that streamlines the production of systematic reviews) for the screening of the search results. Two authors independently screened the titles and abstracts for relevant papers. The full text of potentially relevant papers was subsequently assessed by two independent authors for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Where disagreements persisted, a third reviewer was contacted. We selected papers that were published during the period from 1996 (the date when evidence‐based practice first emerged in the literature) (Closs & Cheater, 1999; Sackett et al., 1996) to the date when the literature search was concluded (June 2019). A total of 46 full‐text papers were screened for eligibility. Among the 46 papers, 45 papers had assessed solely evidence‐based practice educational interventions and 1 paper had assessed the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice interventions. However, we identified no evidence of primary studies that had evaluated and compared the effectiveness of evidence‐informed practice to evidence‐based practice educational interventions. As such, we were unable to perform most of the pre‐stated methodology. We will, therefore, describe the planned methodologies in the ensuing sections.

4.3.2. Data extraction and management

Had we found any eligible study, two independent authors (either S. H. and R. M. or E. A. K. and J. B. S.) would have assessed its methodological validity using standardized critical appraisal instruments from the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta‐Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI‐MAStARI). We would have used the JBI‐MAStARI checklist for case‐control studies, the checklist for case reports, the checklist for cohort studies, the checklist for quasi‐experimental, the checklist for RCTs, and the checklist for analytical cross‐sectional studies. Disagreements between authors would have been resolved through discussion; if no agreement could be reached, a third author was to be consulted.

Data would have been extracted from included papers using standardized data extraction form for intervention reviews for RCTs and non‐RCTs developed by the Cochrane Collaboration. We would have extracted information relating to study design, interventions, population, outcomes that are of significance to the review questions, and specific objectives, and methods used to assess the impact of evidence‐informed practice/evidence‐based practice educational interventions on patient outcomes. Supporting Information Appendix 2 presents the data extraction form we planned to use for this review.

4.3.3. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (either R. M. and S. H. or E. A. K. and J. B. S.) would have independently assessed eligible studies for risk of bias. This would have been done using the Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias tool (Higgins & Green, 2011). Discrepancies between reviewers would have been resolved through consultation and discussion with a third author (V. W.). We planned to categorize studies as having high, low, or unclear risks of bias. We planned to use the following criteria to assess the risk of bias:

Random sequence generation

We would have categorized studies as having a high risk of bias if the authors used a nonrandom sequence generation process, for example, the sequence generated by the preference of the study participants, even or odd date of birth, or availability of the intervention. Studies would have been judged as having a low risk of bias if a random sequence generation process was used, and the process used in generating the allocation sequence is described in sufficient detail and able to produce comparable groups.

Allocation concealment

Studies would have been deemed as having a low risk of bias if the method used in generating the allocation sequence was adequately concealed from study participants, such that study participants are unable to foresee group allocation. We planned to judge studies as having a high risk of bias if the process used in generating allocation sequence was open such that study participants can predict group allocation. This introduces selection bias. An example includes using a list of random numbers.

Blinding of participants and personnel

Inadequate blinding results in participants and personnel having different expectations for their performance, hence biasing the results of the trial. We planned to consider studies as having a low risk of bias if participants and trial personnel are blind to allocation status.

Blinding of outcomes assessors

We planned to examine included studies to determine if outcome assessors were blind to allocation status. Studies would have been considered as having a low risk of bias if outcomes are assessed by independent investigators who had no previous knowledge of group allocation.

Incomplete outcome data

We planned to assess studies to determine if there are any missing outcome data. We would have examined the differences between intervention and control groups in relation to measurement attrition and the reasons for missing data. Studies with low attrition (<20%), no attrition, or no evidence of differential attrition would have been considered as having a low risk of bias. We planned to record the use of Intention to Treat (ITT) analysis and methods of account for missing data (e.g., using missing multiple imputations).

Selective outcome reporting

We intended to assess studies for reporting bias to determine whether there are inconsistencies between measured outcomes and reported outcomes. Studies would have been considered as having a low risk of bias if the results section of publications clearly show that all pre‐specified outcomes are reported.

4.3.4. Measures of treatment effect

Continuous data

For continuous data, where outcomes on the same scale are presented, we planned to use mean difference, with a 95% confidence interval. However, where outcome measures differ between studies, we would have used the standardized mean difference as the effect size metric based on Hedges' g, which is calculated using the following formula:

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we planned to calculate the risk ratio (and its 95% confidence interval) for the occurrence of an event. For meta‐analysis, we planned to convert risk ratios to the standardized mean difference, using David Wilson's practical effect size calculator. We intended to use meta‐regression to assess the impact of moderator variables on the effect size of interventions. We planned to conduct moderator analysis if a reasonable number of eligible research articles were identified and if the required data is presented in the report.

Studies with multiple groups

For studies with one control group versus two or more intervention groups, and all the interventions are regarded as relevant to the study, we planned to use the following options: (1) if the intervention groups are not similar, we would have divided the sample size of the control group into two (or more based on the number of intervention groups), and then compared with the intervention groups (2) if the intervention groups were similar, we would have treated the two groups as a single group. Therefore, we would have provided two effect size estimates in this study. This was to ensure that participants in the control group were not “double‐counted” (Higgins & Green, 2011). We planned to employ a similar approach, but in reverse, in the event that an included study has one intervention group but two control groups. We also planned that if an included study contained an irrelevant and relevant intervention group, we would have included only data from the relevant intervention group for analysis.

4.3.5. Unit of analysis issues

In this systematic review, it was anticipated that included studies may have either involved individual participants or clusters (groups) of participants as units of analysis. we planned that in the event that cluster‐randomized trials (i.e., studies where participants are allocated as a group rather than as individuals) are identified as eligible, we would have used standard conversion criteria as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins & Green, 2011). We planned to do this only if such studies have not been properly adjusted for clustering (e.g., by the use of multi‐level modeling or robust standard errors).

The Cochrane Handbook (Higgins & Green, 2011) recommends guidelines to be followed in calculating the effective sample size in a cluster‐randomized trial. According to the Handbook, the effective sample size can be calculated by dividing the original sample size by the design effect. This equals 1 + (M − 1) × ICC, where M is the average cluster size and ICC is the Intra‐cluster Correlation Coefficient.

4.3.6. Dealing with missing data

We planned to contact the first author of studies with incomplete reports on data or to request relevant information that is missing from the report.

We planned that if requested data was not provided, our options for dealing with missing data would be based on whether data is “missing at random” or “missing not at random.” We planned that if data were missing at random (i.e., if the fact that they are missing is unrelated to actual values of the missing data), data analysis would have been conducted based on the available data.

However, if data is missing not at random (i.e., if the fact that they are missing is related to the actual missing data), we planned to impute the missing data with replacement values, and treat these values as if they were observed (e.g., last observation carried forward, imputing an assumed outcome such as assuming all were poor outcomes, imputing the mean, imputing based on predicted values from a regression analysis).

4.3.7. Assessment of heterogeneity

We intended to assess heterogeneity through the comparison of factors such as participant demographics, type of intervention, type of control comparators, and outcome measures. We would have assessed and reported heterogeneity visually and by examining the I 2 statistic, which describes the approximate proportion of variation that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. This would have been supplemented by the χ 2 test, where a p value < 0.05 indicates heterogeneity of intervention effects. In addition, we planned to estimate and present τ 2 along with its CIs, as an estimate of the magnitude of variation between studies. This would have provided an estimate of the amount of between‐study variation. We also planned to use sensitivity and subgroup analyses to investigate possible sources of heterogeneity.

4.3.8. Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess studies for reporting bias to determine whether there were inconsistencies between measured outcomes and reported outcomes. Studies would have been considered as having a low risk of bias if the results section of publications clearly showed that all pre‐specified outcomes are reported.

4.3.9. Data synthesis

We planned to use narrative and statistical methods to synthesize included studies. The synthesis would have focused on calculating the effect sizes of the included studies. We planned to conduct meta‐analysis if our search yielded sufficient (i.e., two or more) eligible studies that can be grouped together satisfactorily. A logical approach would have been used when combining studies in meta‐analysis. Had we found any eligible studies, decisions on combining studies in meta‐analysis would have been based on two reasons: (1) a sufficient number of eligible studies with similar characteristics, (2) similar characteristics shared by those eligible studies may include the type of intervention and the targeted outcome of the intervention. Had we conducted a meta‐analysis, we planned to use the comprehensive meta‐analysis software developed by Borentein et al. (2005). We would have conducted separate analyses for primary outcomes (i.e., knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and understanding) and secondary outcomes (i.e., patient outcome). In addition, separate analyses would have been conducted for the effect of evidence‐based practice and evidence‐informed practice interventions. We planned to compare evidence‐based practice and evidence‐informed practice interventions by conducting a mean comparison test between the two concepts. The intervention versus control comparisons for each of the concepts would have been based on adjusted post‐test means that control for imbalance at pre‐test. If this information was not available, we planned to subtract the pre‐test means effect size from the post‐test mean effect size by using the unadjusted pooled standard deviation.

4.3.10. Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where there was significant statistical heterogeneity, we planned to conduct subgroup analysis to consider the effects of variables, such as participant's age, geographical area, mode of delivery and content of the educational intervention, and type of study design.

4.3.11. Sensitivity analysis

Had we found any eligible studies, we planned to conduct sensitivity analysis to determine whether the overall results of data analysis was influenced by the removal of:

Unpublished studies

Studies with outlier effect sizes

Studies with high risks of bias

Studies with missing information (e.g., incomplete presentation of findings)

4.3.12. Treatment of qualitative research

Assessment of methodological quality of qualitative papers

Two authors (either S. H. and R. M. or E. A. K. and J. B. S.) would have independently assessed included qualitative studies for methodological validity using the JBI Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI‐QARI). Any disagreements between authors would have been resolved through discussion, if no agreement could be reached, a third author would have been consulted.

Data extraction and management

We planned to extract data from included papers using the Cochrane Collaboration's Data Collection form for Intervention Reviews for RCTs and non‐RCTs (Supporting Information Appendix 2). We would have extracted data relating to the population, study methods, details about the phenomena of interest, outcomes of significance to the review question and specific objectives, and methods used to assess the impact of evidence‐informed practice/evidence‐based practice educational interventions on patient outcomes.

Data synthesis and analysis

We planned to pool qualitative research findings using JBI‐QARI. This would have involved the synthesis or aggregation of findings to generate a set of statements that represent the aggregation. Findings would have been assembled based on their quality, and, by grouping findings with similar meanings together. We would have then performed a meta‐synthesis of these groups or categories to produce a single set of comprehensive synthesized findings. If textual pooling was not possible, we would have presented findings in narrative form.