Abstract

Early life adversities (ELAs) are associated with an increased risk of psychopathology, with studies suggesting a relation to structural brain alterations. Given the recently growing evidence of ELA effects on brain structure, an updated summary is highly warranted. Therefore, anatomical likelihood estimation was used to conduct a coordinate-based meta-analysis of gray matter volume (GMV) alterations associated with ELAs, including sub-analyses for different age groups and maltreatment as specific ELA-type. The analyses uncovered a convergence of pooled ELA-effects on GMV in the right hippocampus and amygdala and the left inferior frontal gyrus, age-specific effects for the right amygdala and hippocampus in children and adolescents, and maltreatment-specific effects for the right perigenual anterior cingulate cortex in adults. These results reveal a possible underlying commonality in the impact of adversity and also point to specific age and maltreatment effects. They suggest neural markers of ELAs in regions involved in socio-emotional functioning and stress regulation, with the potential to be used as targets for interventions designed to buffer or reverse harmful ELA-effects.

Keywords: Childhood adversity, Early life stress, Magnetic resonance imaging

1. Introduction

Early life adversities (ELAs) may be defined as circumstances depriving children of adequate care or confronting them with conditions that provoke fear and anxiety (Herzberg and Gunnar, 2020). ELAs increase the risk for mental disorders across the lifespan. As such, the risk of developing a mental disorder is up to twice as high for ELA-exposed individuals compared to those without ELAs in both the short- and long term (e.g. (Green et al., 2010)). Most commonly, ELAs have been associated with affective disorders, conduct disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), borderline personality disorder (BPD), and substance use disorders in young people (Green et al., 2010; Herzog and Schmahl, 2018; Kessler et al., 2010; Kim and Cicchetti, 2009; Lewis et al., 2019; Murphy et al., 2020) and with adverse effects on health outcomes traceable until mid-to-late adulthood (Chen et al., 2016; Clark et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2017; Takizawa et al., 2015). The degree of increased risk also may depend on the type of ELA (Norman et al., 2012), for example, the association of ELAs and depression was strongest for emotional abuse and neglect across all age groups (Humphreys et al., 2020). Additionally, patients who experienced ELAs typically show an earlier disease onset, worse progression, and poorer treatment response (Nanni et al., 2012).

To understand how ELAs increase the risk for psychopathology, several levels of mechanisms have to be taken into account. Experiences of negative environments are unexpected by the organisms and require significant adaptation by an average individual that relate to changes of socioemotional and cognitive functioning (e.g. (Dunne and Meinck, 2020; Hughes et al., 2017; Pechtel and Pizzagalli, 2011)). These adaptations have been proposed to be mediated by multi-system biological recalibrations that encompass the autonomic nervous system (Esposito et al., 2016), the immune system (Elwenspoek et al., 2017), and the most prominently investigated frequent or chronic over-activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis resulting in a dysregulated stress response (Herzberg and Gunnar, 2020; Pechtel and Pizzagalli, 2011). It has been shown that the HPA-axis is targeted by a variety of different ELAs, such as maltreatment, socioeconomic disadvantages, and prenatal adversity (Bunea et al., 2017; Entringer et al., 2009). If these encounters are chronic and occur in sensitive periods of heightened neural plasticity during development, they may become neurobiologically embedded through reorganization to guarantee functioning to learned environmental contingencies (Hensch, 2005). On a neural level, animal studies have provided evidence that chronic adversities have been shown to induce dendritic atrophy in the fronto-hippocampal circuit and altered dendritic branching in the amygdala that have been linked to cognitive deficits and heightened emotional responding (Holmes and Wellman, 2009; McEwen and Morrison, 2013; Roozendaal et al., 2009; Vyas et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 1992).

These neurobiological reorganizations have largely been confirmed in human studies as well, although heterogeneous effects are observable. Depending on the type of ELA, previous reviews (Holz et al., 2020; Teicher and Samson, 2016) and meta-analyses (Lim et al., 2014; Paquola et al., 2016) have reported structural alterations particularly in the hippocampus, amygdala, and regions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) such as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). Beyond this converging evidence, the results of individual studies show that ELA-related alterations seem to be widely distributed in the brain (as described in Table 1). These are broadly covered by brain regions underpinning socio-affective functioning and memory processing (subcortical volumes such as the amygdala, the hippocampus, and the basal ganglia), and executive control including prefrontal regulatory areas and the visual system. Summarizing the available evidence, the majority of studies investigated the effect of maltreatment and psychosocial deprivation and demonstrated widespread volume reductions in frontal control networks (see Table 1, experiments 1, 6, 8, 11–13, 15, 17, 19–20, 22, 25–28, 30, 32–37, 42, 46), subcortical structures (see Table 1, experiments 10–11, 14, 17, 25, 29, 32, 37), occipital areas (see Table 1, experiments 4, 5, 8, 18, 31, 39), as well as increased frontal (see Table 1, experiments 1, 3, 14, 16, 22, 24–25, 29, 47), subcortical (see Table 1, experiments 2, 12), and occipital volumes (see Table 1, experiment 7).

Table 1.

Experiments Included in the Main Analysis of ELA effects on GMV.

| Ex | Study | n1 | n2 | Diagnosis | Analysis | DV | Age | % ♂ | Med. | ELA | ELA ass. | # foci | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| 1 | (Kelly et al., 2015) | 62 | 60 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 12.46 | 47.54 | no | maltreatment (neglect, emotional & physical & sexual abuse) | social services files were rated on Kaufman scale | 13 | reduction R supramarginal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, L (medial) orbitofrontal gyrus, IFG, supramarginal gyrus, inferior parietal, middle temporal gyrus |

| 3 | increase L precentral gyrus | ||||||||||||

| 2 | (Liao et al., 2013) | 26 | 0 | GAD | correlation Pat | GMV | Adol. | 50 | no | maltreatment | CTQ | 1 | increase L thalamus |

| 3 | (Carrion et al., 2009) | 19 | 24 | PTSS | GMV | Pat vs. HC | 11 | 58.33 | NA | pediatric PTSD | at least one episode DSM-IV criterion A1 trauma | 3 | increase R cuneus/MOG, L inf and MOG/cuneus, R rectal gyrus, L medFG |

| 4 | (Fujisawa et al., 2018) | 21 | 22 | RAD | Pat vs. HC | GMV | 12.86 | 41.58 | no | maltreatment | child welfare facility staff collected information about type and timing of exposure to maltreatment | 1 | reduction L primary visual cortex |

| 5 | (Shimada et al., 2015) | 21 | 22 | RAD | Pat vs. HC | GMV | 12.86 | 41.58 | no | maltreatment | 1 | reduction L primary visual cortex | |

| 6 | (Heyn et al., 2019) | 22 | 20 | PTSD | Pat vs. HC | GMV | 15.35 | 33.33 | NA | pediatric PTSD | CAPS-CA, PTSD-RI | 5 | reduction bilat vlPFC, bilat PCC, R precentral gyrus, R vmPFC |

| 7 | (Chaney et al., 2014) | 10 | 36 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 36.61 | 39.13 | no | maltreatment | 1 | reduction L supramarginal | |

| 2 | increase R inf temporal, L mid occipital | ||||||||||||

| 8 | (Dannlowski et al., 2016) | 309 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 34.3 | 44.66 | no | maltreatment | CTQ | 10 | reduction L STG/MTG/supramarginal gyrus, R caudate nucleus, R IPG/SPG/angular gyrus, R MTG/MOG/angular gyrus, R SOG/cuneus/calcarine fissure, R HC/pHC gyrus, L cuneus, L lingual gyrus, R SFG, R MFG |

| 9 | (Everaerd et al., 2016) | 143 | 72 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 21.9 | 0 | no | maltreatment | List of Threatening Life Events | 1 | reduction right visual posterior precuneal region |

| 10 | (Filippi et al., 2019) | 37 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 24.3 | 37.8 | NA | maltreatment | CTQ | 10 | reduction bilat lobule VIII of cerebellar hemisphere, L lobule VI of cerebellar hemisphere, R lobule VIIB of cerebellar hemisphere, bilat Crus II of cerebellar hemisphere, lobule VII of vermis, bilat HC, L pHC gyrus |

| 11 | (Grabe et al., 2016) | 1826 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 47.88 | 46.71 | NA | genotype x abuse | CTQ | 8 | reduction bilat insula, bilat HC, bilat ACC, L temporal pole/sup gyrus, R MTG |

| 12 | (Kuhn et al., 2016) | 32 | 97 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 24.97 | 41.09 | NA | childhood adversity | CTQ | 3 | reduction bilat temporal lobe, R SFG |

| 2 | increase R paraHC, L HC | ||||||||||||

| 13 | (Lu et al., 2013) | 24 | 24 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 21.5 | 37.5 | NA | maltreatment | CTQ | 1 | reduction R mid cingulate gyrus |

| 14 | (Lu et al., 2018) | 48 | 38 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 33.35 | 50 | no | maltreatment | CTQ | 1 | reduction L pHC gyrus |

| 2 | increase cuneus, dorsal mPFC | ||||||||||||

| 15 | (Luo et al., 2020) | 314 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 19 | 100 | NA | abuse/neglect | 2 | reduction L frontal ed orb & temporal pole sup | |

| 16 | (Mielke et al., 2016) | 25 | 28 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 38.96 | 0 | NA | maltreatment | CECA | 5 | increase bilat precentral gyrus, L inf temporal gyrus, L postcentral gyrus |

| 17 | (Opel et al., 2016) | 20 | 20 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 37.5 | 50 | no | maltreatment | CTQ | 4 | reduction R HC/amygdala/pHC gyrus/putamen, R MFG, R ACC/sup medFG/mid cingulate cortex, bilat lingual gyrus/calcarine fissure |

| 18 | (Tomoda et al., 2009a) | 14 | 14 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 19.6 | 0 | no | sexual abuse | Traumatic Antecedents Interview | 1 | reduction L inf occipital gyrus |

| 19 | (Tomoda et al., 2009b) | 23 | 22 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 21.71 | 46.67 | no | exposure to harsh corporal punishment | Life Experiences Questionnaire | 1 | reduction R medFG |

| 20 | (van Harmelen et al., 2010) | 48 | 97 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 36.94 | 36.27 | no | emotional maltreatment | Nemesis Trauma Interview, List of Threatening Life Events | 5 | reduction bilat med prefrontal gyrus, R cingulate/med prefrontal gyrus, bilat mid cingulum |

| 21 | (Walsh et al., 2014) | 27 | 31 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 18.4 | 44.83 | no | family-focused adverse life experiences | Cambridge Early Experiences Interview | 1 | reduction R cerebellum |

| 22 | (Yang et al., 2017) | 16 | 68 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 30.39 | 27.38 | no | maltreatment | 1 | reduction L posterior cingulate cortex | |

| 1 | increase R IFG | ||||||||||||

| 23 | (Benedetti et al., 2012) | 20 | 20 | OCD | Pat vs. Pat | GMV | 35.48 | 65 | mixed | ELA | sum score over 13 items | 1 | increase L caudate nucleus |

| 24 | (Brooks et al., 2016) | 21 | 0 | OCD | correlation Pat | GMV | 31 | 52 | mixed | maltreatment | CTQ | 1 | increase R orbitofrontal gyrus |

| 25 | (Chaney et al., 2014) | 20 | 17 | MDD | Pat vs. Pat | GMV | 40.22 | 43.24 | mixed | maltreatment | 4 | reduction R rectus, hippocampus, inf temporal, L postcentral | |

| 4 | increase R front sup, front inf oper, L cuneus, front inf tri | ||||||||||||

| 26 | (Fonzo et al., 2013) | 33 | 0 | PTSD | correlation Pat |

GMV | 39.27 | 0 | no | maltreatment | CTQ | 4 | reduction R inf/MOG, bilat pre/postcentral gyrus, R mid/SFG |

| 1 | increase L mid/sup temoral gyrus | ||||||||||||

| 27 | (Monteleone et al., 2019) | 18 | 18 | ED | Pat vs. Pat | GMV | 27.1 | 0 | no | maltreatment | CTQ | 2 | reduction R paracentral lobule, L inf temporal gyrus |

| 28 | (Sheffield et al., 2013) | 24 | 23 | Psychotic Disorder | Pat vs. Pat | GMV | 39.1 | 40.43 | yes | sexual abuse | CTQ | 2 | reduction R ACC, L IFG |

| 29 | (Soloff et al., 2008) | 8 | 14 | Borderline | Pat vs. Pat | GMV | 27.5 | 0 | no | sexual abuse | Dissociative Interview Schedule - Abuse History | 6 | reduction R amygdala, bilat IFG, R pHC gyrus, L MTG, L cingulate gyrus |

| 1 | increase L SFG | ||||||||||||

| 30 | (Song et al., 2020) | 36 | 0 | BPD | correlation Pat | GMV | 30.6 | 44.4 | yes | maltreatment | CTQ | 1 | reduction R precentral gyrus |

| 31 | (Yang et al., 2017) | 41 | 43 | MDD | Pat vs. Pat | GMV | 30.88 | 27.38 | mixed | maltreatment | 1 | reduction L inferior occipital gyrus | |

| 1 | increase cerebellum | ||||||||||||

| 32 | (Brooks et al., 2014) | 116 | 0 | AUD | correlation mixed | GMV | 14.8 | 43.10 | no | maltreatment | CTQ | 2 | reduction R precentral gyrus, L HC |

| 33 | (Kumari et al., 2013) | 56 | 0 | antisocial personality disorder, SCZ | correlation mixed | GMV | 33.18 | 100 | mixed | psychosocial deprivation | rating using interview, case history, clinical records, forensic records on 5-point-scale | 1 | reduction L PFC |

| 34 | (Lu et al., 2019) | 40 | 38 | MDD | mixed vs. mixed | GMV | 22.45 | 44.87 | no | maltreatment | CTQ | 1 | reduction L DLPFC |

| 35 | (Luo et al., 2020) | 1725 | 0 | NA | correlation mixed | GMV | 56.89 | 100 | NA | abuse/neglect | 7 | reduction L parietal inf, supra marginal, lingual, R postcentral, lingual, parietal inf, frontal sup | |

| 36 | (Luo et al., 2020) | 2396 | 0 | NA | correlation mixed | GMV | 56.89 | 0 | NA | abuse/neglect | 5 | reduction L insula, temporal mid, R frontal med orb, temporal sup, temporal mid | |

| 37 | (Maier et al., 2020) | 29 | 33 | NA | mixed vs. mixed | GMV | 26.93 | 22.58 | no | maltreatment | CTQ | 64 | reduction L angular gyrus, calcarine sulcus, inf occipital gyrus, insula, MOG, precentral gyrus, STG, SMA, supramarginal gyrus, R cerebellum XI, crus cerebellum, cuneus, gyrus rectus, IFG, inf temporal gyrus, med OFC, mid cingulate cortex, MTG, mid temporal pole, rolandic operculum, sup occipital gyrus, sup temporal pole, bilat cerebellum VIII, fusiform gyrus, lingual gyrus, MFG, precuneus, SFG, thalamus |

| 38 | (Tomoda et al., 2011) | 21 | 19 | mixed | mixed vs. healthy | GMV | 21.15 | 40 | no | parental verbal abuse | Verbal Aggression Scale | 1 | increase L STG |

| 39 | (Tomoda et al., 2012) | 22 | 30 | NA | mixed vs. healthy | GMV | 21.68 | 26.92 | no | witnessing domestic violence | Traumatic Antecedents Interview | 1 | reduction R lingual gyrus |

| 40 | (Bartlett et al., 2019) | 232 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 15.29 | 0 | NA | life stress in adolescence | Stressful Life Events Schedule | 2 | reduction L sup frontal cortex, R inf parietal cortex |

| 41 | (Benegal et al., 2007) | 20 | 21 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 15.55 | 100 | NA | family history of alcohol dependence | Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism | 11 | reduction bilat SFG, bilat pHC gyrus, bilat amygdala, bilat cingulate gyrus, bilat thalamus, R cerebellum |

| 42 | (Butler et al., 2018) | 65 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 15.8 | 45 | no | community violence exposure | survey of children’s exposure to community violence | 2 | reduction L ACC, L IFG |

| 43 | (Jednoróg et al., 2012) | 23 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 9.58 | 43.48 | NA | SES | Hollingshead two-factor index of social position | 11 | increase bilat HC, bilat pHC gyrus, bilat MTG, bilat insula, R inf occipito-temporal gyrus, L fusiform gyrus, L sup/MFG |

| 44 | (Levesque et al., 2015) | 108 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 15 | 42.59 | no | birth weight | birth weight | 1 | reduction L thalamus |

| 1 | increase R sup frontal cortex | ||||||||||||

| 45 | (Lugo-Candelas et al., 2018) | 16 | 61 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 3.51 | 49.35 | NA | prenatal SSRI exposure | center for epidemiological studies depression scale + SSRI intake | 2 | increase R amygdala/insula, R caudate |

| 46 | (Tyborowska et al., 2018) | 37 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 17.09 | 40.54 | NA | negative personal early life events | life events questionnaire | 23 | reduction L MFG, L frontal pole, L SFG, bilat PCC, R ant insula, R putamen, R insula, R OFC, bilat amygdala, bilat med parietal cortex, L postcentral sulcus, R supramarginal gyrus, R STG, bilat MTG, bilat inf temporal gyrus, bilat MOG, L inf occipital gyrus |

| 47 | (Zuo et al., 2019) | 20 | 20 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 15.8 | 55 | NA | orphan | orphan status | 1 | increase R ant cingulate gyrus |

| 48 | (Beckwith et al., 2020) | 76 | 59 | NA | mixed vs. mixed | GMV | 12.12 | 56.3 | NA | exposure to air pollution | fine particles exposure | 15 | reduction bilat cerebellum, L inf parietal lobule, precentral gyrus |

| 49 | (Corcoles-Parada et al., 2019) | 29 | 14 | NA | mixed vs. mixed | GMV | 11.22 | 58.14 | NA | birth weight | birth weight | 1 | reduction R fusiform gyrus |

| 50 | (McQuaid et al., 2019) | 28 | 55 | NA | mixed vs. mixed | GMV | 12.7 | 45.76 | no | prenatal stress | adapted PTSD questionnaire to collect information about major negative life events during pregnancy | 4 | increase bilat intraparietal sulcus, L supramarginal gyrus, L sup parietal lobule |

| 51 | (Rando et al., 2013) | 42 | 21 | NA | mixed vs. mixed | GMV | 14.66 | 58.73 | no | prenatal cocaine exposure | Addiction Severity Index | 3 | reduction bilat amygdala, HC, pHC gyrus, insula, IFG, OFC, gyrus rectus; L subgenual ant cingulate, L ventral striatum, putamen, sup temporal pole, R inf temporal lobe, ant temporal pole, bilat paracentral lobule, supplementary and preSMAs, dorsal ant cingulate, bilat precuneus, R midcingulate, L sup parietal lobule |

| 52 | (Favaro et al., 2015) | 35 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 25.6 | 0 | no | prenatal stress exposure | semi-structured interview | 1 | reduction L temporal pole, temporal fusiform cortex, ant pHC gyrus |

| 53 | (Haddad et al., 2015) | 110 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy |

GMV | 33 | 49.09 | no | urban upbringing | urbanicity score | 1 | reduction R posterior DLPFC |

| 54 | (Holz et al., 2015) | 33 | 134 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 25 | 40.12 | NA | early life poverty | income level below the risk-of- poverty threshold | 18 | reduction bilat medFG, bilat SFG, L inf temporal gyrus, L precentral gyrus, bilat insula, bilat inf orbitofrontal gyrus, L STG, L MOG, bilat SFG, L MTG |

| 55 | (Lammeyer et al., 2019) | 290 | 0 | NA | correlation healthy | GMV | 28.48 | 54.48 | no | urban upbringing | urbanicity score | 4 | reduction bilat DLPFC, R inf parietal lobule, L precuneus |

| 56 | (Wang et al., 2016) | 114 | 128 | NA | healthy vs. healthy | GMV | 22.61 | NA | no | subjective social status | subjective socioeconomic status (ladder) | 3 | reduction bilat HC, R sup parietal lobule |

| 2 | increase L mPFC, L precentral gyrus | ||||||||||||

| 57 | (Meisenzahl et al., 2008) | 40 | 75 | possibly prodromal phase | mixed vs. mixed | GMV | 25.1 | 61.7 | NA | high risk of psychosis | Familial Risk Status (schizophrenia) | 5 | reduction bilat MFG |

| 58 | (Pascoe et al., 2019) | 150 | 0 | NA | correlation mixed | GMV | 28.5 | 41.3 | NA | VLBW | birth weight | 13 | reduction R frontal pole, R MTG temporooccipital part, R MFG, L paracingulate gyrus, L juxtapositional lobule cortex, L cingulate gyrus ant division, R IFG pars triangularis |

| 19 | increase R sup & MTG post division, R planum polare, R planum temporale, L temporal fusiform cortex post division, bilat HC, L pallidum, R amygdala, L thalamus, R temporal occipital fusiform cortex, R temporal pole, R Heschl‘s gyrus, R insular cortex, L caudate, L putamen | ||||||||||||

| 59 | (Sharma and Hill, 2017) | 43 | 45 | NA | mixed vs. mixed | GMV | 25.9 | 44.32 | NA | high risk for alcohol dependency | structured interview | 5 | reduction L fusiform, L insula, L cerebellum, R lingual |

| 60 | (Sjoerds et al., 2013) | 36 | 107 | MDD /anxiety | mixed vs. mixed | GMV | 38.13 | 28.51 | no | family history of alcohol dependence | family tree method, standardized interview to assess presence of affective disorder in relatives | 1 | reduction R pHC gyrus |

(Experiments 4 & 5 grouped, experiments 15, 35 & 36 grouped, experiments 20 & 60 grouped).

Experiments 1–6, 32, 40–51 included in analysis of effects in children and adolescents (experiments 4 and 5 grouped).

Experiments 7–22, 52–56 included in the analysis of effects in adults with no current psychiatric diagnosis.

Experiments 1–39 included in the analysis of maltreatment effects.

Experiments 1, 7–22 included in analysis of maltreatment effects in participants with no current psychiatric diagnosis.

Experiments 1, 7–22, 40–47, 52–56 included in the analysis of all ELA effects in all participants with no current psychiatric diagnosis.

ACC – anterior cingulate cortex, ant – anterior, AUD – alcohol use disorder, bilat – bilateral, BPD – borderline personality disorder, CAPS-CA – Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM Child/Adoleseent Version, CECA – Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire, CTQ – Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, CUD – cocaine use disorder, DLPFC – dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, DPD – depersonalization disorder, DV – dependent variable, ELA ass. – ELA assessment instrument, ED – eating disorder, Ex – experiment, HC – hippocampus, IFG – inferior frontal gyrus, inf – inferior, L – left, lat – lateral, MDD – major depressive disorder, med – medial, medFG – medial frontal gyrus, MFG – middle frontal gyrus, mid – middle, mixed – compares ELA group with and without psychopathology with non-ELA group with and without psychopathology or analyzes correlation of ELAs with GMV in a single group with and without psychopathology, MOG – middle occipital gyrus, mPFC – medial prefrontal cortex, MTG – middle temporal gyrus, OCD – obsessive-compulsive disorder, OFC – orbi- tofrontal cortex, PCC – posterior cingulate cortex, PFC – prefrontal cortex, pHC – parahippocampal, post – posterior, PTSD – posttraumatic stress disorder, R – right, RAD – reactive attachment disorder, RD – reading disability, SCZ – Schizophrenia, SES – socioeconomic status, SFG – superior frontal gyrus, SMA – supplementary motor area, STG – superior temporal gyrus, sup – superior, VLBW – very low birth weight, vlPFC – ventrolateral PFC, vmPFC – ventromedial PFC.

Similarly, environmental adversities including low SES, air pollution, and urbanicity have been associated with reductions in frontal volumes (see Table 1, experiments 48,53–55), subcortical volumes (see Table 1, experiment 56) and the middle occipital gyrus (see Table 1, experiment 54) but also with increases in frontal (see Table 1, experiments 43, 56) and hippocampal volumes (see Table 1, experiment 43).

Moreover, whereas mostly volume reductions have been reported following family risks as well as stressful life events (frontal: see Table 1, experiments 40, 41, 46, 57; subcortical volume: see Table 1, experiments 41, 46, 60, and fusiform gyrus: see Table 1, experiment 59), increased caudate volume emerged as well (see Table 1, experiment 23).

Obstetric risk (low birth weight) was also differentially related to frontal lobe (see Table 1, experiment 58), thalamic (see Table 1, experiment 44) and fusiform reductions (see Table 1, experiment 49) as well as hippocampal, amygdala, and fusiform increases (see Table 1, experiment 58).

Last, neurobiological alterations following prenatal adversities are also largely distributed with reductions in frontal (see Table 1, experiment 51), occipital (see Table 1, experiment 52), and subcortical volumes (see Table 1, experiment 51–52), and increases in the hippocampus and amygdala (see Table 1, experiment 45).

In conclusion, results from previous studies were heterogeneous in terms of altered brain regions and direction of the effects. This heterogeneity and low replicability of findings may in part be due to small samples and inadequately powered whole-brain analyses that lack sensitivity to small effects and may at the same time overestimate observed effects (Button et al., 2013). From a more design-related point of view, this may arise due to different in- and exclusion criteria for the samples examined and variable operationalizations of ELAs. This heterogeneity of effects makes it hard to disentangle specific effects of different types of adversities. In addition, this diverseness of results is further aggravated by the possibility that neural recalibrations following ELAs may evoke short-term effects observable in children and adolescents and long-term effects in adults (Gehred et al., 2021; Koss and Gunnar, 2018).

Given the recently growing evidence demonstrating widely distributed ELA effects on brain morphology, and that the two latest comparable meta-analyses are over five years old, focused on maltreatment as one specific ELA type, and only included adult samples (Lim et al., 2014; Paquola et al., 2016), we performed an updated meta-analysis. In accordance with the heterogeneity of the available literature and the assumption that ELAs produce frequent or chronic over-activation of the stress response axis, the definition of ELAs applied is very broad. By including experiences of abuse and neglect, prenatal adversities, and more objective environmental disadvantages, this meta-analysis offers a comprehensive overview of the literature currently available, bringing to light possible underlying commonalities while also specifying for types of ELAs wherever the number of studies available permitted the analyses. Additionally, in light of the recent discussion on ELA’s short- and long-term effects (Gehred et al., 2021; Koss and Gunnar, 2018), we performed sub analyses for different age groups (children/adolescents versus adults).

2. Methods

A meta-analysis of effects of ELAs on gray matter volume (GMV; product of cortical thickness and surface area (Panizzon et al., 2009)) was conducted according to general PRISMA guidelines (Matthew et al., 2020), and more specifically MRI best-practice guidelines (Eickhoff et al., 2016; Müller et al., 2018; Nichols et al., 2017; Stroup et al., 2000). Our search also included cortical thickness (CT; distance between the white matter and pial surfaces) and gray matter density (GMD) as further properties of human cortical structure. Thereby, GMV represents a composite score being a product of cortical thickness and surface area (Panizzon et al., 2009). Further properties of human brain structure, such as CT and GMD, should, therefore, be taken into account, particularly, as they are reported to have different sensitive developmental periods and longitudinal trajectories. Specifically, CT has been shown to be largely established by age 2 years (Lyall et al., 2015) and might therefore be particularly vulnerable to ELAs. Consequently, focusing on further brain structural measures besides GMV, such as CT, might give important insights and help to unravel the underlying courses of maturational change.

We identified relevant studies through a computerized systematic literature search of articles published between 2001 and January 2021 using five databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE via PubMed, PsycINFO / PsycARTICLES, Scopus, and Web of Science) (see supplement for more information; Table ST1). To identify further articles, we additionally screened the reference sections of recent pertinent reviews (see supplement).

In order to reduce the risk of selection bias, screening and study selection were conducted independently by two researchers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or through consultation with the last author (NEH).

Studies were selected if: 1) the full text was published in English; 2) articles were peer-reviewed, original studies using human subjects; 3) associations of ELAs with GMV, CT, or GMD were assessed; 4) whole-brain results with coordinates were reported.

ELAs were defined as covering any adverse experiences or influences before the age of 18 pre- or postnatally, including low socio-economic status, urban environment, and maltreatment.

All data relevant for analysis were independently extracted from the included articles by two raters (AK and TP); discrepancies were resolved by the last author (NEH). In the case of missing information, the corresponding authors were contacted (number of contacted authors: 171).

BrainMap GingerALE 3.0.2 (http://www.brainmap.org/) was used to conduct coordinate-based anatomical likelihood estimation (ALE) analyses according to the standard procedures (Eickhoff et al., 2012, 2009; Turkeltaub et al., 2012). ALE calculates the statistical probability of structural change across the whole brain. To this end, coordinates of significant effects of individual experiments are used in a random effects model and modeled as probability distributions, which are then tested against a null distribution of a random spatial association between experiments (Eickhoff et al., 2016). Coordinates not reported in MNI space were converted in GingerALE. To address dependencies between datasets, when different studies reported effects from the same sample, we grouped datasets in order to limit within-subject effects (Turkeltaub et al., 2012; Samea et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2020), whereas we entered datasets separately into the analysis when different groups were compared within the same study.

Analyses were conducted based on consensus guidelines for coordinate-based meta-analyses with inference at a cluster-level family-wise error corrected threshold of p < 0.05 (cluster-forming threshold: p < 0.001) (Eickhoff et al., 2016, 2009; Möller et al., 2018).

The main analysis was performed to map converging effects of ELAs on GMV.

Sub-analyses were conducted based on age and maltreatment as a specific ELA type (as this was the only ELA type with enough studies for further sub-analyses). To this end, studies were split by age group of the sample into child /adolescent samples (<18 years of age) and adult samples (18 and older). Physical and emotional abuse and neglect, sexual abuse, harsh corporal punishment, and exposure to domestic violence were classified as maltreatment. In a separate analysis, we additionally analyzed participants (across both age groups) without psychopathology, i.e., with no current psychiatric diagnosis, to ensure that the results were driven by ELAs and not confounded by psychopathology. Further sub-specifications were performed where possible. Finally, we applied the fail-safe N (FSN) method as used by Acar et al. (Acar et al., 2018) to all analyses, to control for potential publication bias.

3. Results

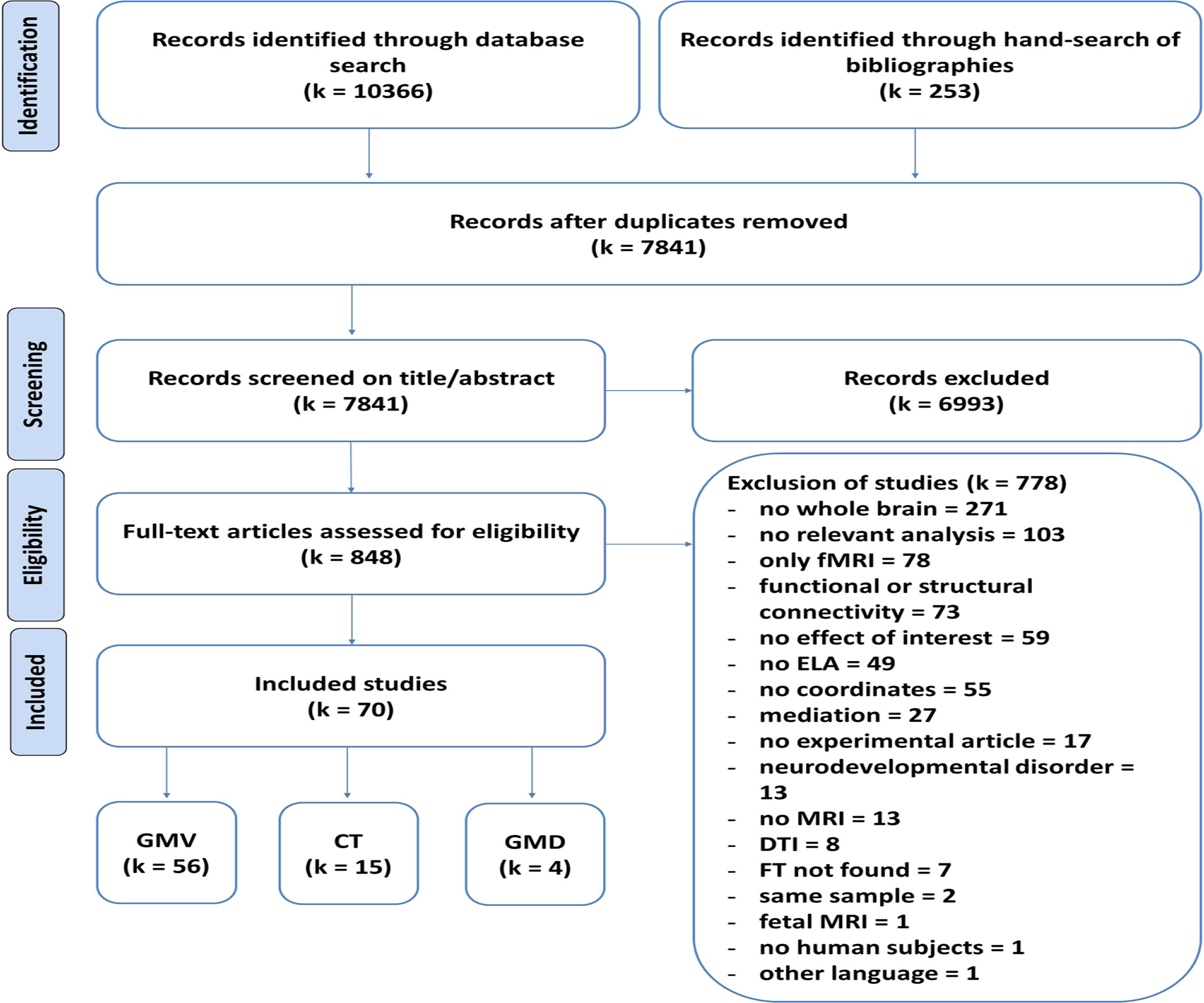

After screening 7841 titles and abstracts and assessing 848 full texts, a total of 70 studies were included in this work (Fig. 1, Table 1, Tables ST2 & ST3). All included studies satisfied the quality requirements on the basis of several criteria that were applied (see supplement for details).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Diagram depicting the search and screening procedure. fMRI – functional magnetic resonance imaging, ELA – early life adversity, DTI – diffusion tensor imaging, FT – full text, GMV - gray matter volume, CT - cortical thickness, GMD - gray matter density.

The number of studies for CT and GMD was lower than recommended for ALE (k < 17) (Eickhoff et al., 2016), therefore these analyses could not be performed (CT: k = 15 studies, including n = 7649 subjects; GMD: k = 4 studies, including n = 134 subjects; see Table ST3).

In this meta-analysis, we included k = 56 studies with n = 4915 subjects in total for GMV (Table 1). Sample sizes of the included studies ranged from n = 21 to n = 2396, with a median of n = 60. k = 19 studies were on children/adolescents and k = 37 studies on adults. Further, k = 10 studies on participants with psychopathology were included (with k = 9 of these on adults with psychopathology).

After application of the FSN method, all results remained unchanged (see Table ST5).

3.1. Main meta-analysis: pooled ELA effects on GMV

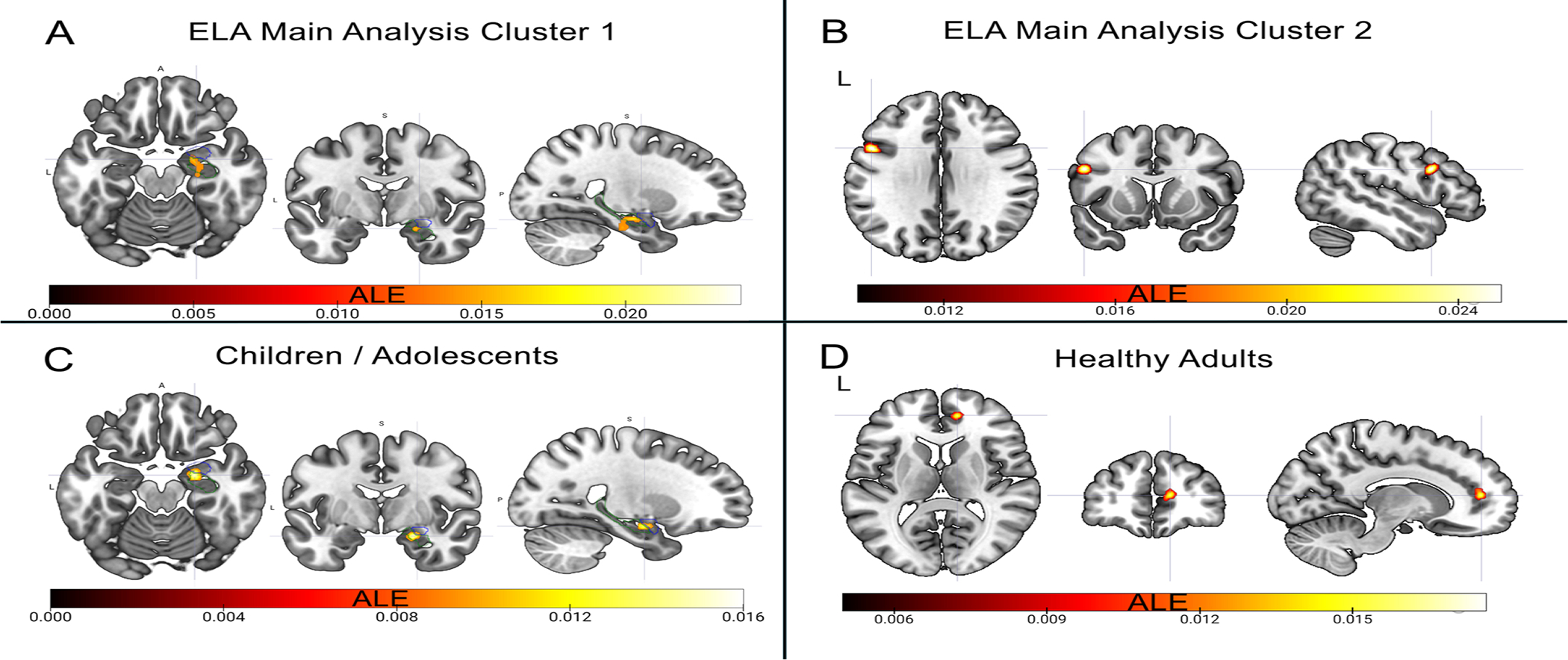

The overall analysis (experiments 1–60, Table 1) revealed that ELAs converged on a cluster containing the right amygdala and the right hippocampus (max. peak (22,−20,−26), ALE= 0.0249, p < 0.001, Z = 4.58) and on a second cluster in the left IFG (max. peak (−50,12,30), ALE= 0.0257, p < 0.001, Z = 4.67; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Illustration of Main Results. A) Cluster of convergence over all types of ELAs in the right hippocampus and amygdala with a peak at (22,−6,−18) shown here. Blue outlines the right amygdala, green outlines the right hippocampus. B) Cluster of convergence over all types of ELAs in the left IFG with a peak at (−50,12,30) shown here. C) Cluster of convergence over all types of ELAs in children / adolescents in the right hippocampus and amygdala with a peak at (22,−6,−18) shown here. Blue outlines the right amygdala, green outlines the right hippocampus. D) Cluster of convergence over all types of ELAs in healthy adults in the right pgACC with a peak at (12,48,10) shown here. The same cluster emerges in the analysis of maltreatment in healthy individuals. MRICroGL was used to visualize the effects. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Sub-analyses

3.2.1. Direction of the effects

Restricting the main analysis to reductions in GMV only, revealed a convergence in the left IFG (max. peak (−50,12,30), ALE= 0.0254, p < 0.001, Z = 4.79), while no convergence emerged when restricting the analysis to GMV increases.

3.2.2. Age-group effects

The right amygdala and hippocampus emerged as convergence sites of ELAs for children and adolescents (age range: 3.51–17.09 years; experiments 1–6, 32, 40–51, Table 1) (max. peak (22,−4,−18), ALE= 0.0154, p < 0.001, Z = 4.40; Fig. 2). No cluster was found for adults (age range: 18.40–56.89 years). Restricting the analysis to healthy adults only (experiments 7–22, 52–56, Table 1) revealed a convergence site in the right perigenual ACC (pgACC; max. peak (12,48,10), ALE = 0.0159, p < 0.001, Z = 4.1; Fig. 2), which was virtually unchanged when only including reductions in GMV in healthy adults (max. peak (12,48,10), ALE= 0.0159, p < 0.001, Z = 4.21).

3.2.3. Maltreatment-specific analysis

While no effect was revealed for maltreatment across all subjects (studies 1–39, Table 1), a convergence in the right pgACC (max. peak (12,48,10), ALE= 0.0159, p < 0.001, Z = 4.21) emerged in healthy subjects only (experiments 1, 7–22, Table 1).

3.2.4. 3.2.4. Participants without psychopathology

A cluster in the right amygdala and hippocampus (max. peak (26,−12,−16), ALE= 0.0179, p < 0.001, Z = 4.16) emerged as a convergence site of ELAs (experiments 1, 7–22, 40–47, 52–56, Table 1, with k = 9 studies on children/adolescents, and k = 21 studies on adults; for results on healthy adults only, see 3.2.2.). This cluster was confirmed when including GMV reductions only.

See Table 2 for a detailed list of all analyses and results.

Table 2.

All Analyses and Results.

| ALE analysis | # exp.k | # foci No | # subjects No [Range] | age [Range] | Cluster No | mm3 | Location of cluster | X | Y | Z | ALE | Z score | Contributors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Main Analysis | Overall | 56 | 353 | 4915 [21–2396] | [3.51–56.89] | 1 | 912 | R Hippocampus / Amygdala | 22 | −20 | −26 | 0.0249 | 4.58 | 1 foci from experiment 12 | |

| 26 | −12 | −16 | 0.0185 | 3.74 | 1 foci from experiment 29 | ||||||||||

| 22 | −6 | −18 | 0.0165 | 3.44 | 2 foci from experiment 41 1 foci from experiment 43 1 foci from experiment 46 1 foci from experiment 56 1 foci from experiment 58 |

||||||||||

| 2 | 776 | L IFG | −50 | 12 | 30 | 0.0257 | 4.67 | 1 foci from experiment 37 1 foci from experiment 42 1 foci from experiment 54 1 foci from experiment 55 1 foci from experiment 57 |

|||||||

| Reductions | 47 | 295 | 4492 [22–2396] | [11.22–56.89] | 1 | 768 | L IFG | −50 | 12 | 30 | 0.0254 | 4.79 | 1 foci from experiment 37 1 foci from experiment 42 1 foci from experiment 54 1 foci from experiment 55 1 foci from experiment 57 |

||

| Increases | 21 | 58 | 1642 [21–242] | [3.51–40.22] | ns | ||||||||||

| Healthy | 30 | 166 | 3248 [23–1826] | [3.51–47.88] | 1 | 816 | R Hippocampus / Amygdala | 26 | −12 | −16 | 0.0179 | 4.16 | 1 foci from experiment 11 | ||

| 34 | −8 | −18 | 0.0127 | 3.37 | 1 foci from experiment 17 1 foci from experiment 41 1 foci from experiment 43 1 foci from experiment 46 1 foci from experiment 56 |

||||||||||

| Healthy Reductions | 27 | 147 | 3078 [28–1826] | [12.46–47.88] | 1 | 928 | R Hippocampus / Amygdala | 26 | −12 | −16 | 0.0179 | 4.24 | 1 foci from experiment 11 | ||

| 34 | −8 | −18 | 0.0127 | 3.45 | 1 foci from experiment 17 1 foci from experiment 41 1 foci from experiment 43 1 foci from experiment 46 1 foci from experiment 56 |

||||||||||

| Adults | Overall | 39 | 250 | 3692 [21–2396] | [18.4–56.89] | ns | |||||||||

| Reductions | 35 | 207 | 3538 [22–2396] | [18.4–56.89] | ns | ||||||||||

| Healthy | 21 | 96 | 2503 [28–1826] | [18.4–47.88] | 1 | 552 | R perigenual ACC | 12 | 48 | 10 | 0.0159 | 4.1 | 1 foci from experiment 11 1 foci from experiment 17 1 foci from experiment 20 |

||

| Healthy Reductions | 20 | 84 | 2450 [28–1826] | [18.4–47.88] | 1 | 600 | R perigenual ACC | 12 | 48 | 10 | 0.0159 | 4.18 | 1 foci from experiment 11 1 foci from experiment 17 1 foci from experiment 20 |

||

| Child/Adol | 18 | 105 | 1339 [23–232] | [3.51–17.09] | 1 | 600 | R Amygdala / Hippocampus | 22 | −6 | −18 | 0.0155 | 4.1 | 1 foci from experiment 41 | ||

| 30 | 2 | −16 | 0.0102 | 3.25 | 1 foci from experiment 43 1 foci from experiment 46 1 foci from experiment 51 |

||||||||||

| Maltreatment | Overall | 36 | 203 | 2771 [21–2396] | [11.00–56.89] | ns | |||||||||

| Reductions | 30 | 175 | 2548 [22–2396] | [12.46–56.89] | ns | ||||||||||

| Healthy | 17 | 82 | 1781 [28–1826] | [12.46–47.88] | 1 | 640 | R perigenual ACC | 12 | 48 | 10 | 0.0159 | 4.21 | 1 foci from experiment 11 1 foci from experiment 17 1 foci from experiment 20 |

||

L – Left, R – Right.

See Table ST5 in the supplemental material for results on sensitivity analyses.

3.3. Systematic review of ELA effects on CT/GMD

As mentioned above, the number of primary studies of ELA effects on CT and GMD did not allow for meta-analyses of these properties. On a descriptive level, four of the 15 studies of ELA effects on CT focused on maltreatment, with results indicating CT reductions in the ACC, the posterior cingulate gyrus (emotional abuse) (Heim et al., 2013), the somatosensory and motor cortex, precuneus (emotional and sexual abuse) and also the parahippocampal gyrus (sexual abuse) (Heim et al., 2013) in adults. Deprivation was reflected in CT reductions in the posterior cingulate as well (Mackes et al., 2020). In children, CT reductions were reported in similar areas such as the ACC (Kelly et al., 2013, 2016), the somatosensory and motor cortex (Whittle et al., 2013), and frontal (Whittle et al., 2013), and occipital (Kelly et al., 2013) areas. Increases of CT in children have been reported following maltreatment in the left rostral middle frontal gyrus (Whittle et al., 2013). Regarding social adversity, an increase of children’s CT in the left fusiform gyrus has been reported after bullying victimization (Muetzel et al., 2019). Following (early) life stress in general, reductions in CT have been reported in the right orbitofrontal cortex in adults (Monninger et al., 2019), whereas in children CT reductions have been found for the left precuneus, and left postcentral gyrus (Bartlett et al., 2019). Concerning more objective forms of environmental adversity, socioeconomic status has been associated with CT reductions in the superior parietal gyrus in children (Leonard et al., 2019) and with CT increases in frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital areas, as well as fusiform and insula (Romeo et al., 2018). Further, exposure to air pollution has been associated with CT reductions in the frontal cortex, the cingulate cortex, the fusiform area, and parietal areas (Beckwith et al., 2020) in children. While obstetric risks (birth weight, gestational age) have been associated with CT reductions in areas of the frontal, temporal, and occipital cortex in children (El Marroun et al., 2020), CT increases were reported in occipital and fusiform areas for adult brains (Pascoe et al., 2019). As for prenatal adversity, one study examined prenatal exposure to thyroid stimulating hormone and reported CT reductions in areas of the frontal cortex, the insula, inferior parietal gyrus, precuneus, and fusiform area and increases in the frontal and fusiform areas, the postcentral gyrus, superior parietal gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, and temporal pole in children (Lischinsky et al., 2016). Another study focused on prenatal exposure to air pollution, reporting CT reductions in frontal and occipital areas as well as the fusiform area and the cuneus in children (Guxens et al., 2018).

Regarding GMD, three of the four studies focused on maltreatment effects in adults, with one study reporting GMD reductions after general maltreatment in the lateral orbitofrontal and middle temporal gyrus (Bachi et al., 2018), one study reporting GMD reductions following abuse in frontal areas, the ACC, and the hippocampus (Thomaes et al., 2010), and one study reporting GMD reductions in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and GMD increases in the IFG following emotional neglect (Cancel et al., 2015). The fourth study focused on prenatal exposure to maternal anxiety and reported GMD reductions for children in frontal, temporal, occipital, and fusiform areas, as well as the cerebellum (Buss et al., 2010).

In conclusion, while the majority of studies on ELA effects on CT found CT reductions (12 studies), particularly in children (9 studies) with five studies indicating an increase in CT in adults (Pascoe et al., 2019) and children (Whittle et al., 2013; Lischinsky et al., 2016; Romeo et al., 2018; Muetzel et al., 2019), all studies on GMD found GMD reductions in either adults or children. However, no clear pattern of regional increases and decreases emerged.

4. Discussion

This meta-analysis provides a quantitative summary of the impact of ELAs on GMV, with converging effects of ELAs in the right hippocampus/amygdala and in the left IFG, and of maltreatment in the right pgACC. As such, this study critically extends the current knowledge on ELA effects across age groups while specifying more broad effects of ELAs in general and maltreatment-specific effects beyond the findings obtained from two earlier meta-analyses (Lim et al., 2014; Paquola et al., 2016). Due to a rather low number of primary studies of ELA effects on CT and GMD, for these two properties of human cortical structure, no (quantitative) meta-analyses could be conducted. Future work should fill this gap in research for more fine-grained analyses allowing to understand in more detail the complex neurodevelopmental effects of ELAs across the lifespan by also comparing different structural properties of the cortex, and to disentangle the temporal dynamics of the rather widely distributed ELA effects on CT and GMD.

First, the main analysis revealed a cluster of convergence in the right hippocampus and amygdala, indicating an effect of overall ELAs on these brain structures. Sub-analyses further specified the main results and showed that this effect emerged specifically in children and adolescents, and reflects GMV reductions in participants without psychopathology, which may lead to several implications. According to the stress acceleration hypothesis, it has been suggested that the amygdala and hippocampus mature earlier in response to adverse environments in order to increase the chance of survival and procreation, which may increase vulnerability to psychopathology (Callaghan and Tottenham, 2016). This accelerated development would also shorten the window of neural plasticity, terminating processes of maturation earlier than in non-exposed individuals. This potentially explains why the same deviations were not apparent in our analysis in adults only. Alternatively, GMV reductions might indicate a delayed development of the amygdala and are therefore visible in children and adolescents only. Importantly, delayed rather than accelerated development has recently been shown for the emotion circuitry (Keding et al., 2021). Thus, more definite interpretations would require normative models of subcortical development derived out of longitudinal samples as a reference. The convergence cluster in the amygdala might index either resilience or latent vulnerability. While the prevailing reason to assume protective effects lies within the fact that this finding as driven by healthy participants, this does not preclude the possibility that GMV reductions may imply a signature of latent vulnerability that renders individuals more prone to psychopathology when confronted with challenging stressful situation. In fact, the latter interpretation is supported capitalizing on previous results demonstrating analogous reductions across several psychiatric disorders (Goodkind et al., 2015) and increased hippocampal volume to be related to resilience (Eaton et al., 2021) with, however, unclear evidence regarding amygdala volumes (Morey et al., 2016; Whittle et al., 2013). Following the line of reasoning of latent vulnerability, amygdala alterations are suggestive of inappropriate stress responses, e.g., under- or overestimating the threat level of a stimulus (Teicher and Samson, 2016). This may lead to emotional dysregulation, which has been considered as a transdiagnostic phenotype involved in several psychiatric disorders (Pozzi et al., 2020; Thompson, 2019). The hippocampus is also involved in the regulation of stress responses and reductions in its volume have been associated with cognitive deficits such as impaired memory consolidation, with both also being related to deficiencies in emotion regulation (Barch et al., 2019).

Second, the left IFG emerged as a convergence site in the main analysis of ELA effects, with a sub-analysis specifying a volume reduction. The IFG is associated with top-down cognitive and affective control, with reductions in volume being linked to impaired emotion regulation and later development of psychiatric disorders such as depression (Luby et al., 2017). Interestingly, the IFG emerged in the overall analysis including both patients and healthy participants, indicating that we cannot rule out that volume changes are confounded with psychopathology such as depression, eating disorders, or alcohol dependence (Fujisawa et al., 2015; Luby et al., 2017; Wiers et al., 2015). As the total sample size of studies including participants with psychopathology (k = 7, sample sizes from 22 to 84, total: 295) is smaller than the sample sizes of studies including healthy participants (k = 27, sample sizes from 28 to 1826, total: 4400) and participants with and without psychopathology (k = 13, sample sizes from 42 to 2396, total: 3582), one might conclude that this effect may be driven by healthy participants. However, the analysis only in healthy participants did not show this convergence, which we assume to reflect a power issue. Further studies are needed, also allowing for more fine-grained analyses of different patient samples.

Third, sub-analyses in healthy adults showed a convergence in GMV reductions in the right pgACC. While this region has been discussed as being moldable by a broad range of environmental circumstances, such as socioeconomic disadvantage (for review see Holz et al., 2020), the current meta-analysis specifically shows its plasticity to maltreatment. Smaller pgACC volumes in adulthood might suggest a cumulative effect of ELAs (Ansell et al., 2012), reflecting its role in HPA axis inhibition and as a target of glucocorticoid action (Boehringer et al., 2015). Notably, ELA effects on regions involved in socio-affective functioning may also result in dysfunctional self-representations and interpersonal functioning (Kessler et al., 1997; Rajalin et al., 2020) underpinned by the ACC (Praus et al., 2021), and therefore may become manifest in the adult brain. In analogy to the limbic cluster mentioned above, the convergence in ACC reductions might index resilience or latent vulnerability. In accordance with the latter, volume increases in frontal regions related to executive functioning are observed in resilient individuals (Eaton et al., 2021). The specific convergence of maltreatment may point to a possible dysfunctional regulation in the face of social adversity (Holz et al., 2020). Indeed, while volume reductions have been specifically related to psychiatric disorders such as depression (Koolschijn et al., 2009), which are also increased following maltreatment (LeMoult et al., 2020), volume increases have shown protective effects regarding internalizing psychopathology (Holz et al., 2016). The reduced GMV in the pgACC may reflect changes caused by stress-induced HPA axis alterations (Boehringer et al., 2015), as indicated by the association of ACC volume with HPA axis dysregulation (MacLullich et al., 2006).

Our results show the impact of ELAs on brain areas involved in socio-affective functioning and stress regulation and may provide important implications for the establishment of biomarker-based treatment options. They point to the left IFG, the right amygdala and hippocampus in children, and the pgACC in adults, as possible neuromodulation targets. Given alterations in these regions observed across a variety of psychiatric symptoms (e.g. (Besteher et al., 2020; Goodkind et al., 2015; Koolschijn et al., 2009; Monninger et al., 2019)), they might represent potential targets for interventions beyond specific diagnoses, for example with neurofeedback training. Indeed, targeting these regions when training patients’ or participants’ ability to purposely regulate brain activity has shown promising results, reflected in subsequently reduced psychopathological symptoms (e.g. (Kohl et al., 2020; Linhartová et al., 2019)). As positive coping styles have been associated with brain regions affected by ELAs (Holz et al., 2016), it is worth exploring whether training emotion-regulation strategies or undergoing cognitive behavioral therapy might have similar regulatory effects on activity in the brain structures involved, and if so, whether these transfer to morphological alterations in the long term.

Our findings partially mirror those of the two previous comparable coordinate-based meta-analyses on this topic (Lim et al., 2014; Paquola et al., 2016). GMV reductions in the left IFG and in the right hippocampus and amygdala have previously been shown following maltreatment (Lim et al., 2014) and exposure to severe stress in childhood (Paquola et al., 2016). However, within our work, we critically extend those earlier findings by showing that those alterations are not specific to maltreatment but represent rather general effects of a variety of ELAs. Further, not all results of our analyses were mirrored in the two earlier meta-analyses above and vice versa, with the additional finding of a convergence in the right pgACC in healthy participants that does not appear in either of the previous analyses for example. This could be due to the differences both meta-analyses show to ours in the samples and results included and in the definition of ELAs. Whereas Lim analyzed only studies of maltreatment (Lim et al., 2014), Paquola used a slightly broader definition of ELA as exposure to severe stress before the age of 16, comprising neglect, abuse, natural disaster, and major family disturbances (Paquola et al., 2016) while we applied the broadest definition of ELAs, in keeping with the assumption that a variety of ELAs contribute to the dysregulation of the stress response axis via its chronic or frequent over-activation, while performing sub-analyses on the effect of specific adversities such as maltreatment. In addition, regarding methodological differences, Paquola included only adult samples (Paquola et al., 2016) and, further, Lim based results on group comparisons (Lim et al., 2014). Regarding the individual studies included, there was a large overlap between ours and the previous meta-analyses (Lim et al., 2014; Paquola et al., 2016) with the difference in the number of studies largely accounted for by studies published after January 2014 (21 of the studies included in the current meta-analysis) and October 2015 (34 of the studies included in the current meta-analysis), respectively. Thereby, our current meta-analysis critically extends the findings from those previous quantitative summaries, by representing an update with recent primary studies published since 2016, including analyses on child and adolescent samples, and including a broad variety of different types of ELAs. Additionally, within our quantitative analysis of ELA effects on maltreatment, 37 more studies were included since the previous meta-analysis, consequently resulting in a higher statistical power. Further, within our work a systematic summary of ELA effects on CT and GMD as two further brain structural properties is provided.

4.1. Limitations and future directions

While ELA effects independent from psychopathology were revealed, due to an insufficient number of studies, it was not possible to unravel the additive or interactive effect with psychopathology in this quantitative review.

Further, our results are based on studies that showed correlations within single groups as well as t-test comparisons between groups with no specific clusters emerging when these classes of studies were separately considered (see Table ST4). While the lack of results might be attributable to less power, future meta-analyses should take this differentiation into account to further increase the homogeneity of the analyses.

Further, the fact that the convergence of the main analysis in the amygdala and hippocampus did not emerge when restricting the analysis to reductions in GMV indicates variability in the individual findings contributing to this cluster of convergence. Indeed, the impact of ELAs on amygdala volume varies across studies with several hypotheses as to the underlying mechanism of this variance. There are suggestions that the direction of the volume change hinges on the type of ELA or the age of exposure, and the age of assessment (Tottenham, 2020). It is also hypothesized that the direction of the effect in the amygdala changes during youth (Herzberg and Gunnar, 2020), with socioeconomic disadvantage for example associated with smaller amygdala volume at younger ages but larger volumes at older ages. What our results show is a convergence of effects of ELAs, in the right amygdala, especially in childhood samples. Further studies are needed to clarify the exact nature of these effects.

In addition, models such as the dimensional model of adversity and psychopathology (Colich et al., 2020) organize the expanse of experiences we have classified as ELAs in this study into underlying dimensions such as threat and deprivation with distinct impact on neural and behavioral outcomes. Due to the landscape of original studies currently available that fit our inclusion and exclusion criteria, it was not possible to examine these dimensions separately in this meta-analysis. Furthermore, as a mechanism biologically interacting with the convergence sites found in our analysis, the HPA axis is targeted by diverse ELAs, such as maltreatment but also socioeconomic disadvantages or prenatal stress exposure (Bunea et al., 2017; Entringer et al., 2009), and therefore might not show specific effects. We have therefore chosen the approach of pooling ELAs to reveal effects that might be common in different ELA-types and emerge despite the heterogeneity in the sample, while also performing sensitivity analyses on more homogenous samples where possible, to reduce heterogeneity.

Moreover, we acknowledge that the convergent effects in the amygdala/hippocampus and the pgACC can be interpreted as resilience or latent vulnerability markers, given that they were mainly driven by findings from healthy participants. A definite conclusion about the nature of the pathway might only be disentangled in longitudinal designs that allow the specification of its predictive validity in terms of stress reactivity and psychopathology, while relying on a deeply phenotyped sample, that entails more information on stressor and its evaluation by the individual, which is crucially dependent on the interaction of individual traits and the social embedding. Further, separate analyses in patients with ELAs as well as contrast analyses between groups of ELA-exposed/non-exposed and healthy/not healthy groups were not possible, which further contributes to this interpretative uncertainty.

Unfortunately, due to rather low numbers of studies for each of the ELA types of interest, no further ELA-subtype analyses besides the one on specific effects of maltreatment could be conducted. While our meta-analysis could be interpreted as a starting point, future studies should take more differentiated characteristics of the adversity such as predictability, chronicity, timing and intensity as well as the subjective burden of ELAs into account (Pollak & Smith, 2021) when addressing specific ELA effects. Furthermore, as mentioned above, there is a variety of internal and external factors moderating the impact of ELAs that could not be included in this study, such as the individual’s genetics, personality, and type, timing, and duration of ELAs (Ioannidis et al., 2020). Therefore, future prospective longitudinal studies on neurodevelopment are essential to provide further clarification.

Besides, our analyses indicate convergence sites that are specific for developmental periods with the number of studies precluding a further subdivision in childhood and adolescence. Given that remodeling effects have been observed not only in infancy but also during adolescence, which constitutes a second period of synaptogenesis and synaptic pruning sets (Pfeifer and Allen, 2021), future studies should focus on more fine-grained age windows.

Finally, as the number of studies on CT and GMD alterations following ELAs was below the recommendations for sufficient power and robustness, no meta-analyses could be performed on those properties. However, a systematic review is presented within the current work. Future meta-analyses should focus on those different properties of cortical structure as they are reported to have different sensitive maturational periods and developmental trajectories (Lyall et al., 2015; Raznahan et al., 2011), consequently allowing for more fine-grained meta-analytical results.

4.2. Conclusions

Relevant convergence sites of ELA effects on GMV were identified in brain regions involved in affective functioning and stress regulation. While we found clusters of convergence of GMV alterations related to pooled ELAs, possibly insinuating an underlying commonality in the impact of adversity in the hippocampus and amygdala and the IFG, our results also point to specific effects of maltreatment in the pgACC. This manifests in developmentally distinct clusters including the right amygdala and hippocampus in children and adolescents and the right pgACC in adults. These findings on transdiagnostic phenotypes of ELAs may highlight their potential as neural targets for interventions designed to buffer or reverse harmful effects of ELAs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (grant number DFG HO 5674/2-1, GRK2350/1-324164820), the Ministry of Science, Research and the Arts of the State of Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany (Special support program SARS CoV-2 pandemic), and the Radboud Excellence Fellowship to N.E.H. T.B. gratefully acknowledges grant support by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01EE1408E ESCAlife; FKZ 01GL1741[X] ADOPT; 01EE1406C Verbund AERIAL; 01EE1409C Verbund ASD-Net; 01GL1747C STAR; 01GL1745B IMAC-Mind), by the German Research Foundation (TRR 265/1), by the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking (IMI JU FP7 115300 EU-AIMS; grant 777394 EU-AIMS-2-TRIALS), and the European Union – H2020 (Eat2beNICE, grant 728018; PRIME, grant 847879). SBE acknowledges funding by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH074457), the Helmholtz Portfolio Theme “Supercomputing and Modeling for the Human Brain“, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Grant Agreement No. 945539 (HBP SGA3). T.B. served in an advisory or consultancy role for ADHS digital, Infectopharm, Lundbeck, Medice, Neurim Pharmaceuticals, Oberberg GmbH, Roche, and Takeda. He received conference support or speaker’s fee by Medice and Takeda. He received royalties from Hogrefe, Kohlhammer, CIP Medien, and Oxford University Press; the present work is unrelated to these relationships. D. B. served as an unpaid scientific consultant for an EU-funded neurofeedback trial unrelated to the present work. All other authors declare no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104589.

References

- Acar F, Seurinck R, Eickhoff SB, Moerkerke B, 2018. Assessing robustness against potential publication bias in Activation Likelihood Estimation (ALE) meta-analyses for fMRI. PLoS One 13, e0208177. 10.1371/journal.pone.0208177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell EB, Rando K, Tuit K, Guarnaccia J, Sinha R, 2012. Cumulative adversity and smaller gray matter volume in medial prefrontal, anterior cingulate, and insula regions. Biol. Psychiatry 72, 57–64. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachi K, Parvaz MA, Moeller SJ, Gan G, Zilverstand A, Goldstein RZ, et al. , 2018. Reduced orbitofrontal gray matter concentration as a marker of premorbid childhood trauma in cocaine use disorder. Front Hum. Neurosci 12 10.3389/fhhum.2018.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Harms MP, Tillman R, Hawkey E, Luby JL, 2019. Early childhood depression, emotion regulation, episodic memory, and hippocampal development. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 128, 81–95. 10.1037/abn0000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett EA, Klein DN, Li KQ, DeLorenzo C, Kotov R, Perlman G, 2019. Depression severity over 27 months in adolescent girls is predicted by stress-linked cortical morphology. Biol. Psychiatry 86, 769–778. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith T, Cecil K, Altaye M, Severs R, Wolfe C, Percy Z, Maloney T,Yolton K, LeMasters G, Brunst K, Ryan P, 2020. Reduced gray matter volume and cortical thickness associated with traffic-related air pollution in a longitudinally studied pediatric cohort. PLoS One 15, 1–19. 10.1371/journal.pone.0228092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti F, Poletti S, Radaelli D, Pozzi E, Giacosa C, Ruffini C, Falini A, Smeraldi E, 2012. Caudate gray matter volume in obsessive-compulsive disorder is influenced by adverse childhood experiences and ongoing drug treatment. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 32, 544–547. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31825cce05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benegal V, Antony G, Venkatasubramanian G, Jayakumar PN, 2007. Gray matter volume abnormalities and externalizing symptoms in subjects at high risk for alcohol dependence. Addict. Biol. 12, 122–132. 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besteher B, Gaser C, Nenadić I, 2020. Brain structure and subclinical symptoms: a dimensional perspective of psychopathology in the depression and anxiety spectrum. Neuropsychobiology 79, 270–283. 10.1159/000501024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehringer A, Tost H, Haddad L, Lederbogen F, Wüst S, Schwarz E, Meyer-Lindenberg A, 2015. Neural correlates of the cortisol awakening response in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 2278–2285. 10.1038/npp.2015.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SJ, Dalvie S, Cuzen NL, Cardenas V, Fein G, Stein DJ, 2014. Childhood adversity is linked to differential brain volumes in adolescents with alcohol use disorder: a voxel-based morphometry study. Metab. Brain Dis. 29, 311–321. 10.1007/s11011-014-9489-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SJ, Naidoo V, Roos A, Foucheá J-P, Lochner C, Stein DJ, 2016. Early-Life adversity and orbitofrontal and cerebellar volumes in adults with obsessive- Compulsive disorder: Voxel-Based morphometry study. Br. J. Psychiatry 208, 34–41. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.162610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunea IM, Szentágotai-Tătar A, Miu AC, 2017. Early-life adversity and cortisol response to social stress: a meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 7, 1274. 10.1038/s41398-017-0032-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss C, Davis EP, Muftuler LT, Head K, Sandman CA, 2010. High pregnancy anxiety during mid-gestation is associated with decreased gray matter density in 6–9-year-old children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35 (1), 141–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler O, Yang X-FX-F, Laube C, Kuhn S, Immordino-Yang MH, 2018. Community violence exposure correlates with smaller gray matter volume and lower IQ in urban adolescents. Hum. Brain Mapp. 39, 2088–2097. 10.1002/hbm.23988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button KS, Ioannidis JPA, Mokrysz C, Nosek BA, Flint J, Robinson ESJ, Munafò MR, 2013. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 365–376. 10.1038/nrn3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan BL, Tottenham N, 2016. The stress acceleration hypothesis: effects of early-life adversity on emotion circuits and behavior. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 7, 76–81. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancel A, Comte M, Truillet R, Boukezzi S, Rousseau P-F, Zendjidjian XY, et al. , 2015. Childhood neglect predicts disorganization in schizophrenia through grey matter decrease in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 132 (4), 244–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion VG, Weems CF, Watson C, Eliez S, Menon V, Reiss AL, 2009. Converging evidence for abnormalities of the prefrontal cortex and evaluation of midsagittal structures in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: An MRI study. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 172, 226–234. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney A, Carballedo A, Amico F, Fagan A, Skokauskas N, Meaney J, Frodl T, 2014. Effect of childhood maltreatment on brain structure in adult patients with major depressive disorder and healthy participants. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 39, 50–59. 10.1503/jpn.120208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Turiano NA, Mroczek DK, Miller GE, 2016. Association of reports of childhood abuse and all-cause mortality rates in women. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 920. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C, Caldwell T, Power C, Stansfeld SA, 2010. Does the Influence of childhood adversity on psychopathology persist across the lifecourse? a 45-year prospective epidemiologic study. Ann. Epidemiol. 20, 385–394. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colich NL, Rosen ML, Williams ES, McLaughlin KA, 2020. Biological aging in childhood and adolescence following experiences of threat and deprivation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 146, 721–764. 10.1037/bul0000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoles-Parada M, Gimenez-Mateo R, Serrano-del-Pueblo V, Lopez L, Perez-Hernandez E, Mansilla F, Martinez A, Onsurbe I, San Roman P, Ubero-Martinez M, Clayden JD, Clark CA, Munoz-Lopez M, 2019. Born too early and too small: higher order cognitive function and brain at risk at ages 8–16. Front. Psychol 10 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannlowski U, Kugel H, Grotegerd D, Redlich R, Opel N, Dohm K, Zaremba D, Groegler A, Schwieren J, Suslow T, Ohrmann P, Bauer J, Krug A, Kircher T, Jansen A, Domschke K, Hohoff C, Zwitserlood P, Heinrichs M, Arolt V, Heindel W, Baune BT, Grögler A, Schwieren J, Suslow T, Ohrmann P, Bauer J, Krug A, Kircher T, Jansen A, Domschke K, Hohoff C, Zwitserlood P, Heinrichs M, Arolt V, Heindel W, Baune BT, 2016. Disadvantage of social sensitivity: Interaction of oxytocin receptor genotype and child maltreatment on brain structure. Biol. Psychiatry 80, 398–405. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne MP, Meinck F, 2020. Childhood adversity and death of young adults in an affluent society. Lancet 396, 449–451. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30899-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton S, Cornwell H, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Fairchild G, 2021. Resilience and young people’s brain structure, function and connectivity: a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Grefkes C, Wang LE, Zilles K, Fox PT, 2009. Coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: A random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Hum. Brain Mapp. 30, 2907–2926. 10.1002/hbm.20718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Bzdok D, Laird AR, Kurth F, Fox PT, 2012. Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis revisited. Neuroimage 59, 2349–2361. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickhoff SB, Nichols TE, Laird AR, Hoffstaedter F, Amunts K, Fox PT, Bzdok D, Eickhoff CR, 2016. Behavior, sensitivity, and power of activation likelihood estimation characterized by massive empirical simulation. Neuroimage 137, 70–85. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.04.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Marroun H, Zou R, Leeuwenburg MF, Steegers EAP, Reiss IKM, Muetzel RL, 2020. Association of gestational age at birth with brain morphometry. JAMA Pedia 174 (12), 1149–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwenspoek MMC, Kuehn A, Muller CP, Turner JD, 2017. The effects of early life adversity on the immune system. Psychoneuroendocrinology 82, 140–154. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entringer S, Kumsta R, Hellhammer DH, Wadhwa PD, Wust S, 2009. Prenatal exposure to maternal psychosocial stress and HPA axis regulation in young adults. Horm. Behav. 55, 292–298. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito EA, Koss KJ, Donzella B, Gunnar MR, 2016. Early deprivation and autonomic nervous system functioning in post-institutionalized children. Dev. Psychobiol. 58, 328–340. 10.1002/dev.21373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro A, Tenconi E, Degortes D, Manara R, Santonastaso P, 2015. Neural correlates of prenatal stress in young women. Psychol. Med. 45, 2533–2543. 10.1017/S003329171500046X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi I, Hoertel N, Artiges E, Airagnes G, Guérin-Langlois C, Seigneurie A-S, Frère P, Dubol M, Guillon F, Lemaitre H, Rahim M, Martinot J-L, Limosin F, 2019. Family history of alcohol use disorder is associated with brain structural and functional changes in healthy first-degree relatives. Eur. Psychiatry 62, 107–115. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonzo GA, Flagan TM, Sullivan S, Allard CB, Grimes EM, Simmons AN, Paulus MP, Stein MB, 2013. Neural functional and structural correlates of childhood maltreatment in women with intimate-partner violence-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 211, 93–103. 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa TX, Yatsuga C, Mabe H, Yamada E, Masuda M, Tomoda A, 2015. Anorexia nervosa during adolescence is associated with decreased gray matter volume in the inferior frontal gyrus. PLoS One 10, 1–12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0128548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa TX, Shimada K, Takiguchi S, Mizushima S, Kosaka H, Teicher MH, Tomoda A, 2018. Type and timing of childhood maltreatment and reduced visual cortex volume in children and adolescents with reactive attachment disorder. NeuroImage Clin. 20, 216–221. 10.1016/j.nicl.2018.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehred MZ, Knodt AR, Ambler A, Bourassa KJ, Danese A, Elliott ML, Hogan S, Ireland D, Poulton R, Ramrakha S, Reuben A, Sison ML, Moffitt TE, Hariri AR, Caspi A, 2021. Long-term neural embedding of childhood adversity in a population-representative birth cohort followed for 5 decades. Biol. Psychiatry 1–12. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.02.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind M, Eickhoff SB, Oathes DJ, Jiang Y, Chang A, Jones-Hagata LB, Ortega BN, Zaiko YV, Roach EL, Korgaonkar MS, Grieve SM, Galatzer-Levy I, Fox PT, Etkin A, 2015. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental Illness. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 305–315. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabe HJ, Wittfeld K, der Auwera S, Janowitz D, Hegenscheid K, Habes M, Homuth G, Barnow S, John U, Nauck M, Voelzke H, Schwabedissen HMZ, Freyberger HJ, Hosten N, 2016. Effect of the interaction between childhood abuse and rs1360780 of the FKBP5 gene on gray matter volume in a general population sample. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 1602–1613. 10.1002/hbm.23123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC, 2010. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 113–123. ht 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guxens M, Lubczyńska MJ, Muetzel RL, Dalmau-Bueno A, Jaddoe VWV, Hoek G, et al. , 2018. Air pollution exposure during fetal life, brain morphology, and cognitive function in school-age children. Biol. Psychiatry 84 (4), 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad L, Schafer A, Streit F, Lederbogen F, Grimm O, Wust S, Deuschle M, Kirsch P, Tost H, Meyer-Lindenberg A, 2015. Brain structure correlates of urban upbringing, an environmental risk factor for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull 41, 115–122. 10.1093/schbul/sbu072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim CMC, Mayberg HSH, Mletzko T, Nemeroff CCB, Pruessner JCJ, 2013. Decreased cortical representation of genital somatosensory field after childhood sexual abuse. Am. J. Psychiatry [Internet] 170 (6), 616–623 (Jun). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK, 2005. Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6 (11), 877–888. 10.1038/nrn1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg MP, Gunnar MR, 2020. Early life stress and brain function: activity and connectivity associated with processing emotion and reward. Neuroimage 209, 116493. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog JI, Schmahl C, 2018. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Front Psychiatry 9, 1–8. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn SA, Keding TJ, Ross MC, Cisler JM, Mumford JA, Herringa RJ, 2019. Abnormal prefrontal development in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: A longitudinal structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 4, 171–179. 10.1016/j.bpsc.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Wellman CL, 2009. Stress-induced prefrontal reorganization and executive dysfunction in rodents. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 33, 773–783. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz NE, Boecker R, Hohm E, Zohsel K, Buchmann AF, Blomeyer D, Jennen-Steinmetz C, Baumeister S, Hohmann S, Wolf I, Plichta MM, Esser G, Schmidt M, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Banaschewski T, Brandeis D, Laucht M, 2015. The long-term impact of early life poverty on orbitofrontal cortex volume in adulthood: results from a prospective study over 25 years. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 996–1004. 10.1038/npp.2014.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz NE, Boecker R, Jennen-Steinmetz C, Buchmann AF, Blomeyer D, Baumeister S, Plichta MM, Esser G, Schmidt M, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Banaschewski T, Brandeis D, Laucht M, 2016. Positive coping styles and perigenual ACC volume: two related mechanisms for conferring resilience? Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11, 813–820. 10.1093/scan/nsw005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz NE, Tost H, Meyer-Lindenberg A, 2020. Resilience and the brain: a key role for regulatory circuits linked to social stress and support. Mol. Psychiatry 25, 379–396. 10.1038/s41380-019-0551-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, Jones L, Dunne MP, 2017. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2, e356–e366. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, LeMoult J, Wear JG, Piersiak HA, Lee A, Gotlib IH, 2020. Child maltreatment and depression: a meta-analysis of studies using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abus. Negl. 102, 104361 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ioannidis K, Askelund AD, Kievit RA, Van Harmelen AL, 2020. The complex neurobiology of resilient functioning after childhood maltreatment. BMC Med 18, 1–16. 10.1186/s12916-020-1490-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]