Abstract

Novel cell-based assays were developed to assess antibody-dependence cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) antibodies against both vaccine and a representative circulation strain HA and NA proteins for the 2014-15 influenza season. The four assays using target cells stably expressing one of the four proteins worked well. In pre- and post-vaccine sera from 70 participants in a pre-season vaccine trial, we found ADCC antibodies and a rise in ADCC antibody titer against target cells expressing the 4 proteins but a much higher titer for the vaccine than the circulating HA in both pre-and post-vaccine sera. These differences in HA ADCC antibodies were not reflected in differences in HA binding antibodies. Our observations suggested that relatively minor changes on the subtype HA can result in large differences in ADCC activity.

Keywords: Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity (ADCC), Influenza hemagglutinin (HA), Influenza neuraminidase (NA), Influenza virus vaccine

1. Introduction

Influenza viruses cause severe respiratory illness, leading to 290,000-600,000 annual deaths and 3-5 million cases of severe disease each year globally(World Health Organization, March, 2018) and an average of estimated 36,000 deaths and 430,000 hospitalizations each year in the United States since the 2010-2011 season(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). Influenza virus infection induces humoral and cellular immune responses with the humoral responses usually considered as an indicator of protection. Antibodies against the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins that neutralize virus, inhibit hemagglutination, or inhibit neuraminidase activity are associated with protection from disease(Couch et al., 2013; Ohmit et al., 2011; Weiss et al., 2020). There are, however, other functional antibodies that contribute to protection against influenza viruses such as antibodies that mediate Fc effects on virus infection including complement activation, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), antibody-dependent cellular viral inhibition (ADCVI), and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP). Influenza ADCC antibodies have been associated with protection from disease and often may have cross-protective potential across strains (de Vries et al., 2020; Florek et al., 2020; Vanderven et al., 2020). Since ADCC antibodies are associated with protection, we hypothesized that they may contribute to year-to-year differences in vaccine effectiveness (VE). ADCC occurs when antibodies bind to influenza virus antigens on the surface of infected cells, effector cells such as natural killer cells bind to the Fc portion through the CD16 (FcrRIIIa) on their surface and the effector cell releases cytotoxic products into the influenza virus-infected cell. To investigate a contribution of ADCC antibodies to immunogenicity, we developed ADCC antibody assays against the HA and NA proteins. Though anti-neuraminidase (NA), anti-hemagglutinin (HA), anti-nucleoprotein (N protein), and anti-matrix protein (M protein) ADCC antibodies have been identified(Asthagiri Arunkumar et al., 2019b; Chow et al., 1979; Kawai et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2019), surface expression of N and M protein is low and HA and NA are more important drivers of ADCC activity (Jegaskanda et al., 2017; Vanderven et al., 2017a). In most prior studies, ADCC activity was detected utilizing NK cell activation assays or ADCC reporter bioassays that measure effector cell activity associated with target cell killing but not functional cell killing (Florek et al., 2020; Friel et al., 2021; Maier et al., 2020). We therefore developed a cytotoxicity assay, similar to ones that we had previously developed for Zika and SARS-CoV-2(Chen et al., 2021a; Chen et al., 2021b), that measures ADCC target cell killing using the HA and NA proteins for both the H3N2 vaccine strain and a representative circulating H3N2 strain for the 2014-2015 influenza season, a low VE year. We sought to determine if there are differences in ADCC induced by 2014-15 influenza vaccination between vaccine and circulating strain HA or NA proteins.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Serum samples and antibodies:

Pre- and post-vaccination serum samples from 70 healthy adults participating in a University of Georgia IRB-approved pre-season (2014-2015 season) study of the 2014-15 influenza virus vaccine responses at the University of Georgia (Carlock et al., 2019; Nunez et al., 2017) were used to evaluate the 2014/2015 H3N2 HA and NA vaccine and circulating strain ADCC assays. Influenza virus infection naïve residual sera were available from young children enrolled into a different IRB-approved study conducted previously at Emory University. The sera were stored at −80°C and were screened by ELISA for maternal influenza IgG. If IgG was detected, the specimen was excluded. All sera were heat-inactivated at 56°C for 1 hour before testing. A monoclonal antibody against neuraminidase (E4) was generated as follows: six- to eight-week-old female BALB/c mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were immunized against influenza A/Hong Kong/4801/2014 by intraperitoneal (ip) administration of 1107 PFU virus followed by ip administration of 2017/18 seasonal Fluarix Quadrivalent vaccine (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) which contained HK/4801 as the H3N2 vaccine component. Spleens were harvested 4 days after the boost and hybridomas were generated as previously described (Wilson et al., 2016). Briefly, individual hybridomas were picked from colonies and supernatants from expanded clones were screened by ELISA using recombinant NA from HK/4801. To ensure clonality, positive clones were further subcloned by single cell sorting using a Wolf cell sorter (NanoCellect Biomedical Inc). Anti-NA mAb were subsequently purified from the tissue culture supernatant of hybridoma clones using a protein G column (GE Healthcare) and quantified using Biolayer interferometry on the Octet Red96 system (ForteBio, Inc).

The following reagents were purchased from providers: moAbs pABC-345 (against human HA) from Creative Biolabs, kz52 (against Ebola glycoprotein) from IBT Bioservices. LS-C175809 (against HA of H3N2 strain) from LifeSpan BioSciences, Inc. and ab197020 (rabbit monoclonal antibody against NA) from Abcam.

2.2. Influenza naïve serum selection by Anti-influenza HA protein IgG ELISA:

Influenza-naïve sera was obtained from young influenza-naïve children that was subsequently used as ADCC antibody negative controls. To exclude the effect of maternal antibodies on the assay, an influenza-HA specific IgG in serum was measured by Enzyme-linked Immunoassay (ELISA). 100 μl/well of 25 ng/ml purified HA protein (SinoBiological #40354-V08B; H3N2 strain: A/Texas/50/2012) in PBS was adsorbed onto 96-well polyvinyl flat-bottom plates overnight at 4°C, the plates were washed 3 times with 0.05% PBS-Tween 20 (PBST) and blocked with 5% fat-free milk in PBS for 2 h. After washing, the serum starting at 1:150 dilution with 3-fold serial dilutions in 5% milk were added, incubated for 2 h, the plates washed 3 times with PBST, and bound IgG was detected using HRP-conjugated goat anti-human IgG Ab (Thermo Fisher Scientific #31412). Color was developed using TMB substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific #34021), the reaction stopped with 50 μl 4 M H2SO4, and absorbance measured at 450 nm against a reference of 690 nm.

2.3. Influenza HA and NA genes and reporter construct:

HA and NA genes from the 2014-15 seasonal H3N2 vaccine strain (A/Texas/50/2012 X-223A, EPI_ISL_132571) and a representative of the predominant circulating strain (A/Louisiana/20/2014, EPI_ISL_169290) were used to develop four ADCC target cell lines, respectively. The codon optimized HA and NA genes from the strains were synthesized (Genscript). The HA genes were separately cloned into the pCDNA5/TO (puro) plasmid and named “pcDNA5/TO (p)_2014 vac_H3” and “pcDNA5/TO (p)_2014 cir_H3”. The NA genes of vaccine strain and circulating strain were separately cloned into the pCDNA5/TO plasmid and named “pcDNA5/TO _2014 vac_N2” and “pcDNA5/TO_2014 cir_N2”.

2.4. Development of the ADCC cell line:

T-Rex293 cell line was stably transfected with enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) and Luciferase reporter genes that was previously published (Chen et al., 2021b). The clone with the highest expression of GFP and luciferase with the lowest background was used to develop HA and NA target cell lines and as well used as control cell line for the ADCC assay development. We termed this line as reporter-only cells. To generate stable inducible cell lines expressing the respective HA or NA proteins, reporter-only cells were transfected with H3 plasmids (pcDNA5/TO (p) 2014 vac_H3 or pcDNA5/TO (p) 2014 cir_H3) or N2 plasmids (pcDNA5/TO_2014 vac_N2 or pcDNA5/TO_2014 cir_N2). The pCDNA5/TO, or pCDNA5/to(puro), vector allows tetracycline-regulated expression of HA and NA in the presence of TetR in reporter-only cell line. Expression of HA or NA from these plasmids is controlled by the CMV promotor and under tetracycline-regulation in the presence of TetR. Thus, the stably transfected cells HA, or NA, cell lines are tetracycline inducible. After antibiotic selection, the proteins expressed by the cell lines were characterized by Western blot and flow cytometry using monoclonal HA(3) or NA(2) antibodies. Single clones with high surface expression of the HA or NA protein were amplified, divided into aliquots, and stored in liquid nitrogen.

2.5. Characterization of target cell surface influenza antigens by flow cytometry

Flow cytometry studies of surface expression of the respective HA or NA protein were used to select optimal clones for the four target cell lines (i.e., one each for 2014 vaccine and circulating HA and NA proteins). For flow cytometry, the cell lines were induced with doxycycline for 20 hours, incubated with monoclonal antibodies (pABC-345 for HA; E4 for NA) or influenza-positive serum specimens for 1 hour at 4°C. Human anti-Ebola glycoprotein moAb kz52 or influenza-naïve sera were used as negative controls. Following incubation, the cells were stained with Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (H+L) antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory: #109-136-098) for 30 min, fluorescing cells detected with an LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), and results analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). The target cell lines from clones with the highest level of HA or NA surface fluorescence were used for subsequent experiments.

2.6. Western Blot:

Vaccine and circulating HA or NA target cells were then induced with 2μg/ml of doxycycline for 40 hours to induce HA- or NA-antigen expression and cell lysates were prepared and separated by SDS/PAGE electrophoresis under reducing conditions. The proteins were then transferred from gel to nitrocellulose. The HA or NA proteins were detected by Western blot using anti-HA antibody (LS-C175809), or anti-NA antibody (ab197020).

2.7. HA-mediated membrane fusion assay:

After confirming correct size of the HA protein expressed in the target cell lines by Western blot studies, we confirmed intact function by HA-mediated membrane fusion assay as previously described (Galloway et al., 2013; Steinhauer et al., 1991). Briefly, the codon optimized genes from 2014-15 seasonal H3N2 vaccine strain and circulating strain were inserted into pCDNA3.1(+) vector separately. 1.0 μg of plasmid encoding HA genes was transfected into BHK-21 cells using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Where noted, 0.25 μg plasmid encoding human airway trypsin-like protease (HAT) or 0.25 μg transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2) plasmids was included in the transfection. At 16–18 hours post transfection, HA-expressing BHK cells were washed once with PBS and treated with 5 μg/ml TPCK-Trypsin (Sigma) at 37°C for 15 min. Trypsin-treated HA-expressing cells were exposed to pH adjusted 1.0 ml PBS using 100 mM citric acid to the indicated pH at 37°C for 5 min. The pH-adjusted PBS was removed, complete growth medium was added to the cells incubated at 37°C for 2 hours to allow syncytia to form, and the cells stained with the Hema3 Stat Pak according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Syncytia were visualized and photographed using a Zeiss Axio Observer inverted microscope.

2.8. NA neuraminidase assay:

After confirmation of size by Western Blot studies, the NA proteins expressed in the cell lines were evaluated for neuraminidase activity with the NA-Fluor™ Influenza Neuraminidase Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA) performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the induced cells were trypsinized and washed twice with PBS, serial dilutions of resuspended cells were added to a 96-well black plate with an equal volume of NA-Fluor substrate working solution. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. After terminating the reaction by adding NA-Fluor stop solution, the plate was read using an excitation wavelength of 350nm and an emission wavelength of 450nm. The data were analyzed using Excel and GraphPad Prism. NA activity was reflected on relative fluorescence unit (RFU) plotted with cell numbers.

2.9. Effector cells:

The effector cells utilized for the assay were from the CD16-176 V-NK-92 cell line (ATCC: PTA-6967) which has high expression of CD16 on the cell surface. A NK-92 cell line (ATCC CRL-2407) that lacks CD16 was used as an effector negative control cell. The effector cells were maintained in NK complete medium (Alpha MEM without ribonucleotides and deoxyribonucleosides media containing 0.2mM of Myo-inositol, 0.1mM of 2-Mercaptoethanol, 0.02mM of Folic acid, and 12.5% each of heat-inactivated horse and fetal bovine serum) supplemented with 200 IU/ml of human recombinant IL-2 (R&D system: #202-IL-050).

2.10. ADCC assay:

HA and NA target cells and Reporter-only cells (used as control cells) were incubated in DMEM supplemented with 10% Tet-approved fetal bovine serum (FBS) without selection antibiotics for 48 hours. The cells were trypsinized, washed once with this medium, and then re-suspended to a concentration of 2x105 cells/mL in the presence of 2 μg/ml doxycycline and seeded into a 96-well clear-bottom black plate with CellBIND surface (Corning 07-201-96) in a volume of 100 μl per well. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 16 to 20 hours with doxycycline induction. The serum samples were serially diluted (3-fold) in duplicate wells in 96-well V-bottom plates with AIM V™ (Gibco 12055091) medium starting at 1/30 dilutions. The induced target cells were removed from the incubator and 50μl of medium was carefully removed from each well. Then 50μl of serially diluted serum was added to each of the target cell wells. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes while the effector cells were being prepared. The effector cells were cultured in a 75 cm2 cell culture flask with NK cell complete medium supplemented with 200 IU/ml of recombinant human IL-2 (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN). On the day of the experiment, the NK cells were washed once with AIM V™ medium and resuspended in AIM V™ medium at a cell density of 1.6 x 106/ml to create an effector: target (E: T) cell ratio of 2:1. Then, 50 μl of effector cell suspension was added into the target cell plate. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 4 hours in 5% CO2 incubator before being placed at RT for 30 minutes to equilibrate to ambient temperature. The plate was centrifuged at 850×g for 5 min and then 50 μl of the medium was removed from each well. Subsequently, 100μl of ambient temperature Britelite Plus luciferase substrate (PerkinElmer 6066769) was added to each well and mixed thoroughly using a multichannel pipettor. The bottom of the plate was covered with Black Vinyl sealing tape (Thermo Scientific: 236703) and the top of the plate was covered with Adhesive Clear Polyester Seal Film (GE Healthcare: 7704-0001). The plate was incubated for 5 min and Relative Luminescence Units (RLU) were read on a luminometer (TopCount NXT Luminescence Counter). The percent lysis of target cells was calculated for each well using the following formula:

2.11. Statistical analysis:

The specificity and sensitivity of ADCC assay was analyzed and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were developed. The assay performance using sera from adults vaccinated with 2014-2015 influenza vaccine and influenza naïve sera at different serum dilutions was analyzed. Analysis of corresponding ROC curves, area under the ROC curve (AUC), and different cutoff values were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.0). Correlation analysis between antibody binding activity (MFI) and ADCC was performed by Spearman correlation method. Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s t-tests. P-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Development of Influenza Hemagglutinin (HA) and Neuraminidase (NA) protein ADCC Target Cell Lines from 2014-15 Seasonal Vaccine and Circulating H3N2 Strains:

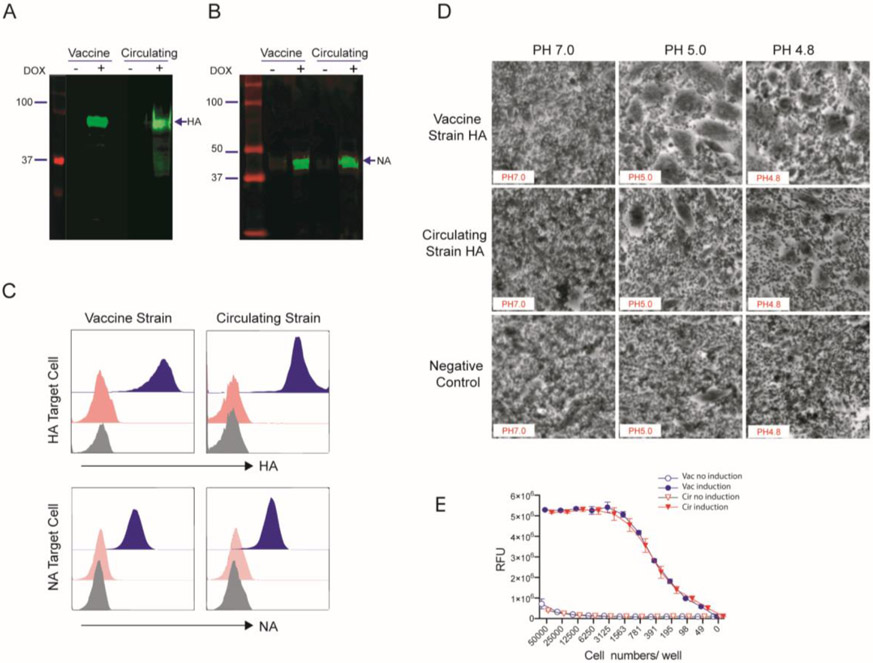

The target cell lines express the hemagglutinin (H3) or neuraminidase (N2) from either the vaccine or circulating 2014-15 influenza H3N2 strains with dual reporters of GFP and luciferase. These genes are regulated by tetR and induced by doxycycline/ tetracycline. The expected full-length HA and NA proteins were detectable in cell lysate after doxycycline induction but not without induction (Figure 1A and B). We designated the HA-expressing cell lines as 2014-15 vaccine HA target cell line and 2014-15 circulating HA target cell lines. NA-expressing cell lines were designated similarly, i.e., 2014-15 vaccine NA and 2014-15 circulating NA target cell lines (Supplementary Table 1). To determine antibody binding to HA and NA protein on target cells, flow cytometry was conducted to determine antibody binding to the hemagglutinin for HA positive cell lines and the neuraminidase for NA target cell lines. The human monoclonal antibody against HA (pABC-345) gave strong fluorescence for both vaccine and circulating HA target cells with no binding of isotype control antibody kz52 (human anti Ebola glycoprotein antibody) (Figure 1C top). A similarly strong fluorescence signal was observed for both NA target cell lines with an anti-NA (E4) monoclonal antibody (Figure 1c bottom). To further assess if the hemagglutinin genes expressed were functional, a qualitative syncytia assay was employed. BHK cells were transiently transfected with an HA expression plasmid following treatment procedures that are detailed in the Materials and Methods, and the cells were visualized by light microscopy. Both HA proteins fused the cells at pH less than 5 as visualized by light microscopy, representative photomicrographs are shown in Figure 1 D. We also measured the neuraminidase activity of our NA target cell lines using NA-Fluor Influenza Neuraminidase Assay Kit. Both vaccine and circulating NA target cell lysates demonstrated high neuraminidase activity 24 hours after doxycycline induction. Neuraminidase activity was not observed on the cell lysates without induction (Figure 1 E). These results demonstrate that the HA and NA proteins in the target cell lines are the correct size and functionally intact.

Figure 1. Characterization of the influenza HA and NA expressing target cell lines.

Identification of Influenza hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) protein expression on HA (A) and NA (B) target cells from 2014-15 H3N2 vaccine and circulating strains by Western blot. The HA and NA target cells were induced with 2 μg/ml of doxycycline and the cell lysates were harvested. The HA and NA protein in the cell lysates were determined by using moAb against HA (LS-C175809) and NA (ab197020). (C) Influenza HA protein expression (Top) and NA protein expression (Bottom) on the target cell surface were separately stained with monoclonal antibodies against HA (pAPC-345) and NA (E4). The stained target cells were analyzed with flow cytometry. All histograms represent specific staining (blue) against HA (moAb pAPC-345) and NA (moAb E4) vs isotype control kz52 (red). (D) Photomicrographs of syncytia formation assay to test HA protein induced pH-induced fusion. BHK cells were transfected with plasmids containing the HA genes of 2014-15 vaccine or circulating strain. Empty plasmid was used as a negative control. Following the treatments detailed in the Materials and Methods, the cells were imaged. Photomicrographs corresponding to the last pH at which syncytia were observed and 0.1-pH unit higher are shown. (E) The functional neuraminidase enzyme activity of both 2014-15 vaccine and circulating strains in NA-expressing target cells were determined. The cells were induced with 2μg/ml of doxycycline in 24 hours and then the cell lysate was diluted. The neuraminidase enzyme activity was measured at multiple sample dilutions. Non-induced cell lysates were used as a control.

3.2. Assay development for evaluation of specific ADCC Abs to HA and NA antigens of influenza A viruses in human stable cell line

3.2.1. Influenza HA ADCC Assay:

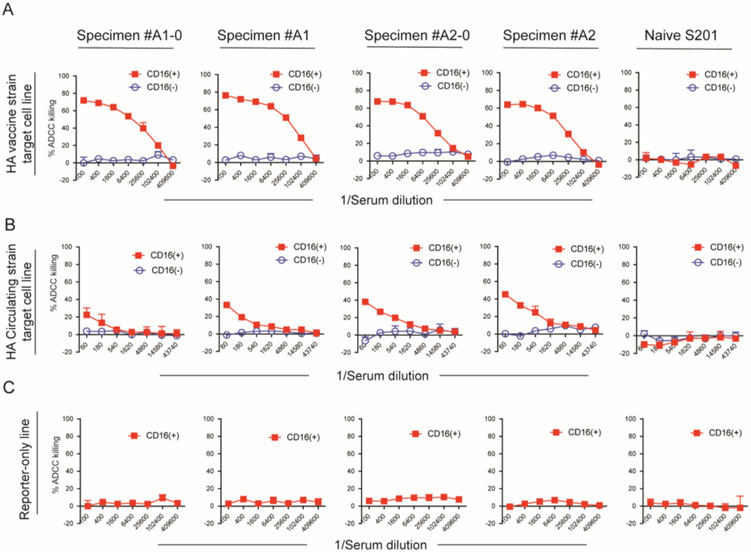

We conducted our ADCC assay using serum samples from adult volunteers who received 2014-15 H3N2 influenza vaccine. Serum from influenza-naïve children were used as ADCC antibody negative controls. The sera were naïve if a 1:150 dilution of the sera had an absorbance value <0.1 in the anti-HA ELISA (Supplementary Figure s1). In a pilot study with 4 adult sera, we noted that the ADCC antibody titer was much higher for the vaccine HA compared to the circulating HA ADCC assay and chose to use a higher starting dilution (1:100 vs 1:60) and 4-fold instead of 3-fold dilution series for the vaccine HA assay. We sought to confirm that our assay measured ADCC activity by comparing cell killing of the HA expressing target cells by CD16(+) NK effector cells to that by CD16(−) NK effector cells. All 4 sera from vaccinated adults mediated lysis of both vaccine and circulating HA antigen expressing target cells with CD16(+) NK effector cells but not with CD16(−) NK effector. For vaccine HA target cells, all 4 sera gave >20% killing at the 1:25,600 dilution with CD16(+) NK effector cells with a maximum of 76% killing at a 1:100 dilution. Against the circulating HA target cells, the maximum killing was 45% at the 1:60 serum dilution, percent killing dropped below 20% at the 1:1,620 serum dilution (Figure 2B). In contrast, with the CD16(−) NK cells cell lysis did not exceed 10% (Figure 2A). Reporter-only target cells lacking HA surface expression did not undergo cell lysis in the presence of adult vaccinated sera and NK CD16(+) effector cells. (Figure 2c). Similarly, the H3N2 influenza-naïve sera from children did not elicit target cell lysis, either in the presence of NK CD16(+) effector cells. Representative data are shown in the last panel of Figure 2A, B, and C.

Figure 2. ADCC of influenza HA target cells from 2014-15 vaccine strain and circulating strain mediated by the serum from 2014-15 vaccinated volunteers via Fc receptor binding.

The target cells and Reporter-only cells were incubated with individual influenza vaccinated sera and NK CD16(+) effector cells or NK-92 cells lacking CD16 on the surface. (A) shows the percentage of cell lysis of 2014-15 vaccine strain HA target cell elicited by 4 influenza vaccinated serum samples and one influenza naïve infant serum. (B) shows ADCC from 2014-15 circulating strain HA target cell. (C) shows that the reporter-only control cell line did not undergo ADCC by the sera in the presence of NK CD16(+) effector cells. The serum dilution is indicated on the x-axis. All samples were run in duplicate, and data represent the mean ± standard deviation of %ADCC cell lysis

3.2.2. Influenza NA ADCC Assay:

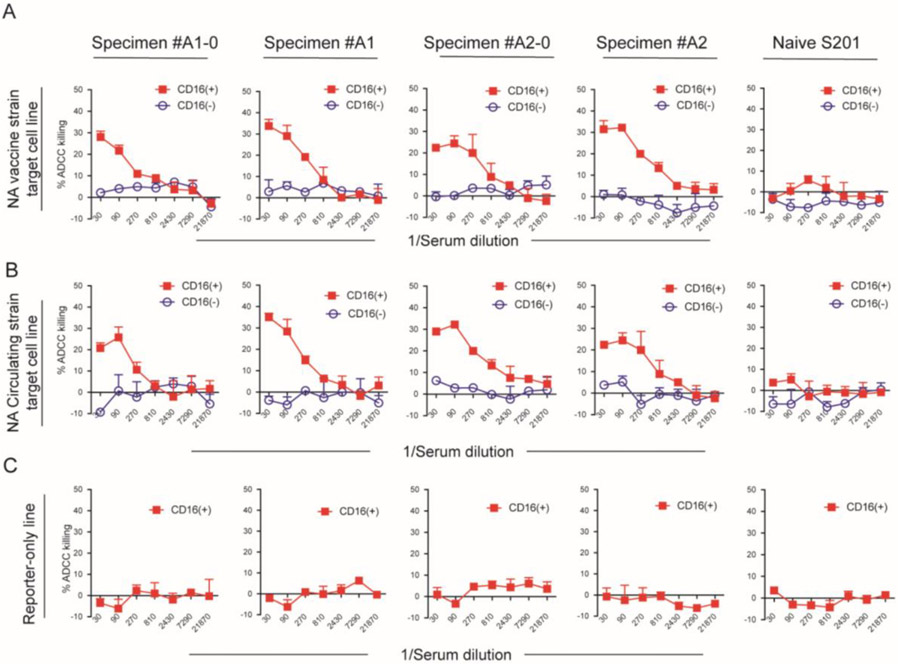

We next examined ADCC activity of the NA antigens of 2014-15 season vaccine and circulating strain using adult serum samples from HA ADCC positive subjects and influenza naïve infant serum. Relatively low levels of cell lysis, i.e., low levels of ADCC activity, with both vaccine NA and circulating NA target cells were detected in adult serum samples and none of the influenza naïve child sera. Representative data from four individual serum samples with ADCC activity and one influenza naïve child serum are shown in Figure 3A (vaccine NA target cell) and Figure 3B (circulating NA target cell). With the NK CD16(−) cells replacing NK CD16 (+) effector cells, we did not observe ADCC at any serum dilution nor did we detect cell lysis on reporter-only cells in the presence of NK CD16(+) effector cells (Figure 3 C). These data support the antigen and Fc specificity of the NA ADCC assays.

Figure 3. ADCC of influenza NA target cells from 2014-15 vaccine strain and circulating strain mediated by the serum from 2014-15 vaccinated volunteers.

ADCC was elicited by 4 adult sera and not elicited by influenza-naïve child serum on vaccine strain NA target cells (A) and circulating NA target cells (B). Reporter-only control cell line did not undergo ADCC by the sera in the presence of NK CD16(+) effector cells (C). The serum dilution is indicated on the x-axis. All samples were run in duplicate, and data represent the mean ± standard deviation of %ADCC cell lysis.

3.3. Pre-vaccine Sera exhibit higher titer of ADCC antibodies to 2014-15 vaccine HA than the 2014-15 circulating HA.

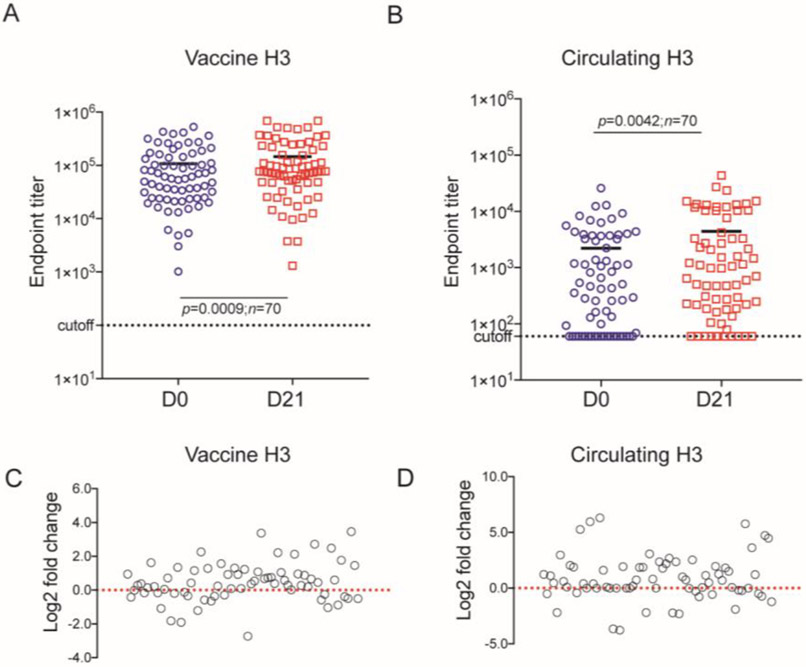

To evaluate this assay, we examined the ADCC activity in pre-vaccination (D0) and post-vaccination (D21) sera from 70 adult recipients of the 2014-15 FluZone® vaccination that included the H3N2 strain (A/Texas/50/2012 X-223A). We first tested for HA ADCC. To determine cut-off value of vaccine and circulating HA, we tested 5 sera from HA naïve children’s sera (i.e., no detectable antibody in the HA ELISA) (Supplementary Figure S1). None of these sera induced more than 10% cell killing at any dilution to both vaccine and circulating HA. We chose 20% of cell lysis of vaccine HA target cells as the cutoff for ADCC antibodies and the ADCC endpoint titer as the highest dilution that had >20% cell lysis. All the serum from our cohort had detectible ADCC antibodies in pre-vaccination and post-vaccination samples. The endpoint titer ranged from 1,022 to 527,475 (median: 59,093) in pre-vaccine serum samples and from 1,317 to 687,500 (median: 77,130) in post-vaccine samples. The ADCC titers against circulating HA target cells were substantially lower than against the vaccine HA target cells. To explore the difference of endpoint titer against circulating HA between pre-vaccine serum and post-vaccine serum, we reevaluated the cutoff value by analyzing the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) for 14 vaccinated adult sera and the 10 influenza naïve children’s sera at each dilution (Supplementary Figure S2). The cutoff values for end-point titers at each dilution were calculated and are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Based on the ROC analysis and the fact that the influenza naïve sera had maximum cell lysis <10% at each dilution, we chose 10% as the cutoff value for calculation of circulating HA target cells ADCC activity. The highest dilution that had ADCC activity >10% was considered the endpoint titer for that specimen. The ADCC response to circulating HA target cell ranged from 60 to 25,870 (median: 426) in pre-vaccine serum samples and from 60 to 43,740 (median: 841) in post-vaccine samples. Twenty-one of 70 samples had ADCC activity below the cutoff level in pre-vaccine serum samples and 11 of 70 in post-vaccine serum samples. To determine the effect of vaccination on ADCC response, the difference of endpoint titer from pre-vaccination to post-vaccination serum on 2014-15 season vaccine HA target cell (Figure 4C) and on circulating HA target cell (Figure 4D) were assessed by log2 fold change. Forty-seven subjects from this cohort had increased ADCC responses against vaccine HA, and 44 subjects had increased ADCC responses against circulating HA. Thus, vaccination significantly increased HA-specific ADCC antibodies against both vaccine and circulating strains of influenza. The mean difference between pre- and post-vaccine sera for vaccine HA was 39,105 (p<0.0009) and for circulating HA was 2,189 (P0=0.0042). The 13 amino acid differences between the vaccine and circulating 2014/2015 influenza season HAs are given in Table S4.

Figure 4. ADCC antibody end-point titers against the 2014-2015 vaccine H3 and circulating strain HA target cells in pre-vaccination (D0) and post-vaccination (D21) sera with a cutoff of 20% for the vaccine HA and 10% for the circulating HA target cells (n=70).

Lines represent the median of the end-point titers. Statistical comparisons were made using paired t-test. log2 fold change analysis shows the difference of ADCC end-point titers between pre-vaccination (D0) and post-vaccination (D21) induced by samples on vaccine HA target cells (C) and on circulating HA target cells. Each symbol represents an individual serum sample.

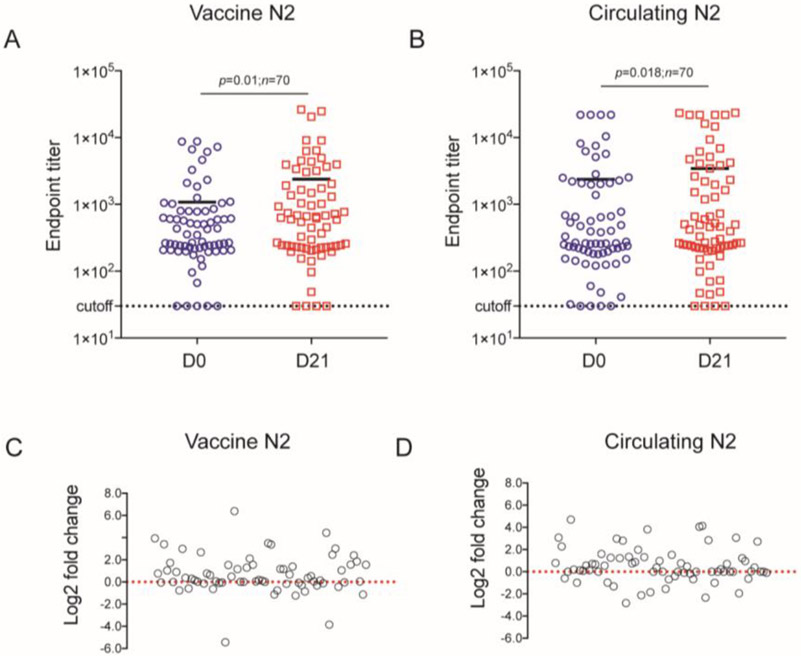

3.4. ADCC antibody to NA of detected in 2014-15 vaccinated human sera

After HA, NA is considered as the second major influenza surface glycoprotein. To investigate the ADCC activity of anti-NA antibodies, we first used 7 HA ADCC-positive adult sera and 5 influenza-naive children’s sera to assess antibody mediated NA target cell lysis (both vaccine and circulating NAs). The NA target cell killing elicited by these sera was analyzed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the area under the corresponding experimental ROC (AUC) for each serum dilution (Supplementary Figure S3). The sensitivity and specificity of cutoff values for end-point titers at each dilution are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Based on the ROC optimized cutoff values at each dilution, 6% was chosen as the optimal cutoff value for ADCC for both vaccine and circulating NA end-point titer calculations. Then, we tested the ADCC response to vaccine NA and circulating NA target cells induced by the sera from this cohort of 70 vaccinated adults. We found that almost all the serum samples had detectible ADCC levels. The median of endpoint titer to vaccine NA target cells is 353 (range from 30 to 8,778) in the pre-vaccine serum group and 626 (range from 30 to 26,250) in the post-vaccine group (Figure 5A). The median of ADCC endpoint titer to circulating NA target cell is 265 (range from 30 to 21,870) in the pre-vaccine serum group and 440 (range from 30 to 23,487) in post-vaccine group (Figure 5B). The difference of endpoint titer induced by pre-vaccine and post-vaccine serum samples on 2014-15 season vaccine NA target cell (Figure 5C) and on circulating NA target cell (Figure 5D) was assessed by log2 fold change. The post-vaccination sera ADCC titer was higher than the pre-vaccination titer for most subjects (vaccine NA n=48, circulating NA=52). As with HA-specific ADCC, there were significant differences in the pre-vaccine and post-vaccine NA-specific ADCC endpoint titers. The ADCC titers were lower than those observed for the HA-expressing cell lines. The mean of difference between pre- and post-vaccine sera for Vaccine NA is 1,306 (p=0.01) and for circulating NA is 1,060 (P=0.018).

Figure 5. ADCC antibody end-point titers from NA target cells in sera from the volunteers who received 2014-15 influenza vaccine.

The ADCC antibody end-point titers specific to 2014-15 vaccine strain NA protein (A) and 2014-15 circulating strain NA protein (B) in the presence of the sera from the volunteer’s pre-vaccination (D0) and post-vaccination (D21) were determined using a cutoff of 6% (n=70). Lines represent the median of the end-point titers. Statistical comparisons were made using paired t-test. log2 fold change analysis shows the difference of ADCC end-point titers between pre-vaccination (D0) and post-vaccination (D21) induced by all volunteer samples in vaccine NA target cells (C) and in circulating NA target cells (D). Each symbol represents an individual serum.

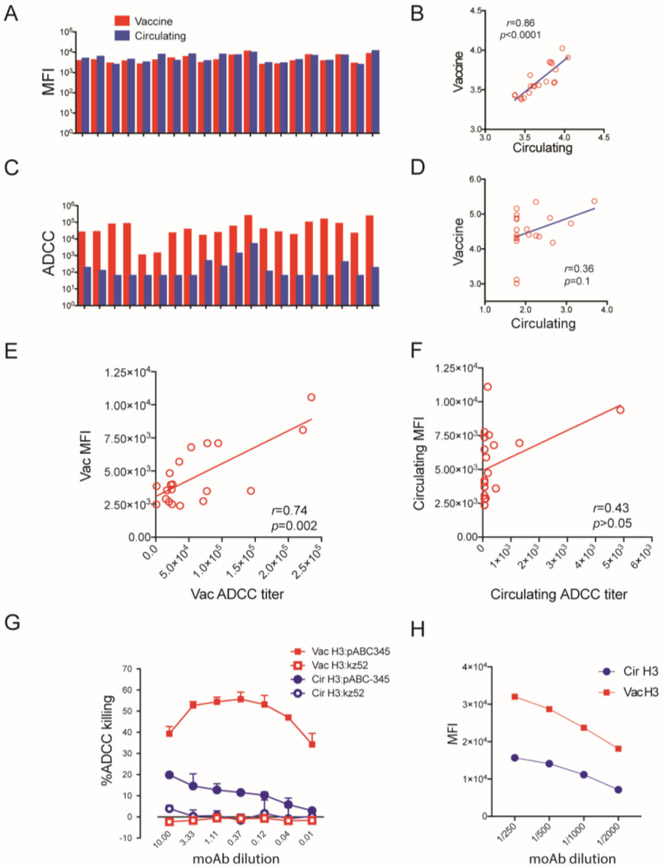

3.5. ADCC responses to HA of target cell surface do not highly correlate with surface bound IgG

Typically, ADCC occurs when the antibodies bind the specific antigen on the surface of a target cell in the presence of effector cells. We have found that ADCC response correlates with antibody binding activity in prior Zika and COVID-19 studies (Chen et al., 2021a; Chen et al., 2021b). To explore the relationship between antigen-specific antibody binding to ADCC activity for HA, we tested the antibody binding on vaccine HA and circulating HA target cells with 10 paired pre- and post-vaccination adult sera (total samples = 20) by flow cytometry assay. The specific antibody binding activity was analyzed by mean fluoresce intensity (MFI). We observed similar levels of IgG to vaccine HA and circulating H3 for these specimens (mean MFI of 4,591 for vaccine HA vs 5,343 for circulating HA) and a correlation for antibody binding to the vaccine compared to the circulating HA cell line of 0.86 (Pearson, p value<0.0001) (Figure 6 A and B). In contrast, as noted above the ADCC titers were very different between the vaccine HA (mean titer of 30,609) compared to the circulating HA (mean titer 60). The Pearson correlation coefficient for ADCC titers for the two HAs was also much lower, 0.36 (p=0.1) between the two (Figure 6 C and D). We compared the correlation of ADCC with MFI and found that ADCC correlated with bound IgG to vaccine HA (r=0.74, p=0.0002; Figure 6E) and lower correlation to circulating HA (r= 0.43, p>0.05; Figure 6 F). The binding studies suggest that in the polyclonal response, the difference in ADCC titers between vaccine and circulating HAs is not explained solely by a difference in binding antibodies. To explore the relationship between binding and ADCC activity, we tested the HA-specific moAb (pABC-345) for binding and ADCC activity. We had already detected ADCC activity against both vaccine and circulating HA target cells with this monoclonal antibody. pABC-345 mediated strong ADCC response to vaccine HA target cell and weak ADCC responses against circulating HA target cell (Figure 6 G) and similarly had a robust binding activity to vaccine HA and low binding activity to circulating HA (Figure 6H). This indicated, for this specific monoclonal antibody, a correlation between binding activity and ADCC activity for vaccine and circulating HA target cells.

Figure 6. Correlation between H3 binding and ADCC antibodies on the target cell surface.

(A) Binding activity of 10 paired sera (20 sera) from 2014-15 vaccinated volunteers against the 2014-15 vaccine HA target cells and 2014-15 circulating HA target cells (A). The correlation of binding activity to vaccine HA and circulating HA is shown in (B). The ADCC response induced from these same sera are shown in (C). Correlation analysis of ADCC response to vaccine HA and circulating HA from the same group serum samples were analyzed (D). Correlation analysis of ADCC with IgG bound to vaccine HA and circulating HA are shown in (E) and (F). (G) shows ADCC of 2014-15 vaccine strain HA target cells and circulating strain induced by moAb against H3N2 virus (pABC-345) in the presence of NK CD16(+) effector cells. moAb kz52 was used as an isotype control. (H) Vaccine HA target cells and circulating HA target cell was stained with moAb pABC-345 with multiple dilutions and antibody binding was measured by flow cytometry. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was analyzed by FlowJo software.

4. Discussion

Recently, ADCC antibodies have been associated with broader reactivity across influenza strains than neutralizing or HAI antibodies(Ermler et al., 2017; Morrison et al., 2017). In this report, we describe new ADCC antibody assays, against HA or NA proteins for the vaccine strain or a representative circulating strain from the 2014-2015 influenza season. The four assays were developed to study the contribution of ADCC antibody to vaccine immunogenicity. The expressed proteins are of the correct size, react against monoclonal antibodies with the appropriate HA or NA specificity, and retain biological activity i.e., pH dependent cell fusion for HA, and NA function (i.e., neuraminidase activity). Furthermore, the assays show good sensitivity and specificity. With these assays, we demonstrate ADCC activity in most pre- and post-vaccination sera from 70 participants in a 2014-2015 study of influenza vaccination. For example, all participants had high levels of vaccine strain HA ADCC antibodies in both serum specimens. The finding that all 70 had ADCC antibodies pre-vaccination is not surprising due to the likelihood of multiple exposure through lifetime influenza infections and often multiple vaccinations which induce HA-specific antibodies easily detected in adult serum (de Vries et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021; Liao et al., 2020; Vanderven et al., 2020). Interestingly, we found a modest boost in HA ADCC titers after vaccination (boost in median titer of 1.3-fold for the vaccine HA and 2.0-fold for the circulating HA). Vanderven et al. analyzed ADCC activity in human serum samples from 3 groups of subjects receiving the 2008-2009 seasonal trivalent vaccine and found that participants classified as high HAI responders had increased ADCC titers post-vaccination against homologous HA proteins while non-responders had no detectible increase in ADCC after vaccination (Vanderven et al., 2017b).

In this study, we found NA ADCC antibodies in many specimens, but at titers lower than the HA ADCC antibody titers (i.e., median titers were 1,494-fold lower for pre-vaccine and 1,098-fold lower for the post-vaccine for vaccine HA and NA and 1.6- and 1.9-fold lower for the circulating HA and NA). Antibodies to NA have been associated with protection against infection during seasonal and pandemic influenza outbreaks for 50 years (Monto and Kendal, 1973; Murphy et al., 1972) but often are not measured after vaccination and the NA content of the vaccine is not standardized. However, studies have noted that pre-influenza infection anti-NA antibodies are associated with a reduction in influenza illness duration in adults and impact transmission among adults (Brett and Johansson, 2005; Gubareva and Mohan, 2020; Maier et al., 2020; Pushko et al., 2010). NA antibodies have also been associated with improving protection against pandemic influenza (Monto and Kendal, 1973; Viboud et al., 2005). Recently, Stadlbauer et al. identified human NA monoclonal antibodies that provide broad protection against both influenza A and B viruses as indicated by a panel of three NA monoclonal antibodies that had ADCC activity against influenza A (H1N1, H5N1, H7N9) and B viruses, even when these moAbs exhibited weak binding (Madsen et al., 2020; Stadlbauer et al., 2019). Others have had similar observations (Yasuhara et al., 2019). Our result is consistent with these prior studies. The rate of NA antigenic drift is slower than HA (Westgeest et al., 2012) which may explain the broad ADCC activity mediated by these adult sera. Compared to HA, NA protein has a relatively lower expression on the viral surface and attracts less immune response (McAuley et al., 2019) which is consistent with our finding of lower NA than HA ADCC antibody titers.

We unexpectedly found a large, significant difference in ADCC antibody titers between the vaccine and circulating strain HA proteins; with a more prominent ADCC response against the vaccine than circulating strain HA, both in pre- and post-vaccination sera. A study that assessed HA ADCC antibodies against two influenza B HA strains, one representing the B/Vic lineage and one representing B/Yam showed modest differences in ADCC antibody titers, ~2-fold, between the two HAs. Note that we did not see much difference between the vaccine and circulating strain NAs in ADCC titers and the target NK cell line used for these assays is homozygous for a polymorphism in its FcγRIIIa gene. This polymorphism is associated with increased binding affinity to antibody on target cells (Mahaweni et al., 2018; Wu et al., 1997). Though this polymorphism may also affect the ability of this binding to induce ADCC activity, it is unlikely to explain the marked increase in HA ADCC activity for the vaccine compared to the circulating strain HA that was consistently seen in individual serum specimens. We wondered if the difference in ADCC titers between the vaccine and circulating strain HA proteins might be associated with overall differences in binding but found only a minimal difference in MFI (indicative of level antibody binding to the target cells) for vaccine compared to the circulating strain HA target cells. This minimal difference is insufficient to account for the large difference in ADCC titers. We suspect this level of difference may result from a combination of factors related to epitope differences in the two HA proteins. For example, the location of an epitope on the influenza HA is critical in determining whether another antibody is available that allows the Fc-FcγRIIIa on the effector cell to interact with two antibodies on the target cell surface as noted in several studies of influenza ADCC activity (Cox et al., 2016; DiLillo et al., 2016; He et al., 2016; Leon et al., 2016). A recent study on how antibody specificity affects Fc effector function has demonstrated that interactions among influenza glycoprotein-binding antibodies of varying specificities regulate the magnitude of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity induction(Asthagiri Arunkumar et al., 2019a; Vanderven et al., 2020). Antibodies targeting the conserved stalk region of HA have been reported to potently induce ADCC (Cox et al., 2016; DiLillo et al., 2016; DiLillo et al., 2014; Leon et al., 2016), but the antibodies binding to HA head region did not (DiLillo et al., 2014). Further study found that the ADCC response induced by some ADCC antibodies binding to the HA stalk domain were inhibited by HA head antibodies (He et al., 2016). The magnitude of ADCC by the human polyclonal IgG is, at least in part, influenced by the ratio of ADCC-inducing and ADCC-inhibiting antibodies (Li et al., 2021). Another factor in ADCC activity is that it may require two antibodies binding on the target cell surface to create the molecular bridge required for ADCC activity. Leon et al. demonstrated that antibody-dependent cell-mediated immunity requires two synapses between the effector cell and the virus-infected cells and the location of binding on the influenza HA and determines whether a second antibody can bind in a fashion to create the molecular bridge. A single Fc-FcγRIIIa interaction is insufficient to induce potent ADCC activity (Leon et al., 2016). Thus, the level of ADCC activity in a serum specimen depends on the sum of the contribution to ADCC of the individual antibodies and sometimes interactions between these antibodies. Individual differences in ADCC antibodies likely result from a combination of factors including host response genes, past experience with influenza virus infection and vaccines, other recent infections, etc. The circulation of influenza H3N2 strains with HAs antigenically similar to the 2014/2015 vaccine HA in 2012/2013 (Centers for Disease and Prevention, 2013) and inclusion of an antigenically similar H3N2 in the 2013/2014 season vaccine (Epperson et al., 2014), may explain the high ADCC HA antibody titers from this vaccine trial in the fall of 2014 but not the extent of differences, 13 amino acid differences, between vaccine and circulating strain HAs. The predominant circulating strains for the 2014/2015 season were more antigenically different from 2014/2015 vaccine strain(Appiah et al., 2015).

Our data suggest that strain level differences in the influenza virus HA protein can markedly affect individual antibody ADCC activity. We explored the relationship of antibody binding to ADCC titer with one monoclonal antibody pABC-345 and found relative levels of binding and ADCC activity for vaccine and circulating strain HA proteins to be comparable, unlike our findings with human serum specimens. However, a much larger study of antibodies that includes a representative sample of epitopes on these two HA proteins is needed to further explain our findings. Further study is needed to understand the features of antibodies and epitopes that effect ADCC. The results of the present study, however, do demonstrate the importance of considering strain differences in studies of influenza HA ADCC antibodies and, possibly, ADCC activity against other target antigens.

Most previous studies of ADCC antibody responses to influenza virus vaccination have demonstrated that healthy humans have cross-reactive ADCC-mediating antibodies. Multiple vaccination and infections may boost influenza virus specific ADCC. We expected that ADCC antibody levels in the study samples would be similar against the vaccine and circulating HA proteins. However, we found ADCC antibodies detected against the circulating HA target cells at a much lower titer than against the vaccine HA target cell and that this difference was not accompanied by a similar difference in binding. Interestingly, strain HA and NA proteins for this study are from a year with low vaccine effectiveness, i.e., 6% (Flannery et al., 2016; Zimmerman et al., 2016). It is possible that the large difference in ADCC antibody titers between vaccine and circulating strain HA proteins might help explain this low VE, but further study is needed to determine if such a relationship exists.

Conclusion:

We generated 2014-15 influenza virus season vaccine and circulating influenza virus H3N2 subtype HA and NA ADCC assays with target cell lines that stably express functional HA or NA proteins on the cell surface. With these assays, sera from 70 adults pre- and post-seasonal influenza vaccination were evaluated from the 2014-2015 season. We found baseline ADCC activity against the vaccine and circulating proteins for HA and NA, a boost in titers after vaccination, and higher titers against HA than NA. Of note, we find much higher ADCC antibody titers for the vaccine than circulating strain HA. The basis for these differences and the possibility that differences in ADCC antibody titers between vaccine and circulating strain HAs may contribute to differences in vaccine effectiveness merit further study. Our data highlights the importance of considering the potential impact of strain differences in future studies of the role of ADCC antibodies in influenza disease and vaccines.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Influenza antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) antibodies have been associated with protection from disease.

The ADCC assays based on stable and inducible antigen expressing target cells efficiently determined influenza HA and NA ADCC antibody responses in vaccinees from a clinical trial of the influenza vaccine for the 2014/2015 influenza season, a season with low vaccine effectiveness.

ADCC antibody titers against the 2014/2015 vaccine strain HA were much higher than those against a representative circulating strain HA indicating that relatively minor differences in the HA protein can result in large differences in ADCC antibodies.

Vaccine and circulating influenza HA and NA specific ADCC antibodies were detected pre-vaccination and a rise in titer post-vaccination titer was detected in many vaccinees.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS) to L.J.A. We would like to thank Rebecca Kondor at CDC for providing us influenza strain information.

We thank staff at UGA for kindly providing 2014-15 vaccinated specimens.

Finally, we would like to thank all the participating volunteers for donating their specimens.

Funding

This study was funded through HHSN272201400004C (NIAID Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance, CEIRS)

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or funding agency.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests:

LJA has done paid consultancies on RSV vaccines for Bavarian Nordic, ClearPath Vaccines Company, Pfizer, and ADVI; his laboratory is currently receiving funding through Emory University from Pfizer for laboratory studies for RSV surveillance studies in adults, and Sciogen for animal studies of RSV vaccines; he is a co-inventor on several CDC patents on the RSV G protein and its CX3C chemokine motif relative to immune therapy and vaccine development; and is co-inventor on a patent filing for use of RSV platform VLPs with the F and G proteins for vaccines.

E.J.A has consulted for Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur, Janssen, and Medscape, and his institution receives funds to conduct clinical research unrelated to this manuscript from MedImmune, Regeneron, PaxVax, Pfizer, GSK, Merck, Sanofi-Pasteur, Janssen, and Micron. He also serves on a safety monitoring board for Kentucky BioProcessing, Inc. and Sanofi Pasteur. His institution has also received funding from NIH to conduct clinical trials of Moderna and Janssen COVID-19 vaccines.

Reference

- Appiah GD, Blanton L, D'Mello T, Kniss K, Smith S, Mustaquim D, Steffens C, Dhara R, Cohen J, Chaves SS, Bresee J, Wallis T, Xu X, Abd Elal AI, Gubareva L, Wentworth DE, Katz J, Jernigan D, Brammer L, Centers for Disease, C., Prevention, 2015. Influenza activity - United States, 2014-15 season and composition of the 2015-16 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64, 583–590. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asthagiri Arunkumar G, Ioannou A, Wohlbold TJ, Meade P, Aslam S, Amanat F, Ayllon J, Garcia-Sastre A, Krammer F, 2019a. Broadly Cross-Reactive, Nonneutralizing Antibodies against Influenza B Virus Hemagglutinin Demonstrate Effector Function-Dependent Protection against Lethal Viral Challenge in Mice. J Virol 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asthagiri Arunkumar G, McMahon M, Pavot V, Aramouni M, Ioannou A, Lambe T, Gilbert S, Krammer F, 2019b. Vaccination with viral vectors expressing NP, M1 and chimeric hemagglutinin induces broad protection against influenza virus challenge in mice. Vaccine 37, 5567–5577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett IC, Johansson BE, 2005. Immunization against influenza A virus: comparison of conventional inactivated, live-attenuated and recombinant baculovirus produced purified hemagglutinin and neuraminidase vaccines in a murine model system. Virology 339, 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlock MA, Ingram JG, Clutter EF, Cecil NC, Ramgopal M, Zimmerman RK, Warren W, Kleanthous H, Ross TM, 2019. Impact of age and pre-existing immunity on the induction of human antibody responses against influenza B viruses. Hum Vaccin Immunother 15, 2030–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease, C., Prevention, 2013. Influenza activity--United States, 2012-13 season and composition of the 2013-14 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 62, 473–479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018. Past seasons estimated influenza disease burden. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Anderson LJ, Rostad CA, Ding L, Lai L, Mulligan M, Rouphael N, Natrajan MS, McCracken C, Anderson EJ, 2021a. Development and optimization of a Zika virus antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) assay. J Immunol Methods 488, 112900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Rostad CA, Anderson LJ, Sun HY, Lapp SA, Stephens K, Hussaini L, Gibson T, Rouphael N, Anderson EJ, 2021b. The development and kinetics of functional antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Virology 559, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow TC, Beutner KR, Ogra PL, 1979. Cell-mediated immune responses to the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase antigens of influenza A virus after immunization in humans. Infect Immun 25, 103–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch RB, Atmar RL, Franco LM, Quarles JM, Wells J, Arden N, Nino D, Belmont JW, 2013. Antibody correlates and predictors of immunity to naturally occurring influenza in humans and the importance of antibody to the neuraminidase. J Infect Dis 207, 974–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox F, Kwaks T, Brandenburg B, Koldijk MH, Klaren V, Smal B, Korse HJ, Geelen E, Tettero L, Zuijdgeest D, Stoop EJ, Saeland E, Vogels R, Friesen RH, Koudstaal W, Goudsmit J, 2016. HA Antibody-Mediated FcgammaRIIIa Activity Is Both Dependent on FcR Engagement and Interactions between HA and Sialic Acids. Front Immunol 7, 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries RD, Nieuwkoop NJ, Krammer F, Hu B, Rimmelzwaan GF, 2020. Analysis of the vaccine-induced influenza B virus hemagglutinin-specific antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity response. Virus Res 277, 197839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo DJ, Palese P, Wilson PC, Ravetch JV, 2016. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J Clin Invest 126, 605–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo DJ, Tan GS, Palese P, Ravetch JV, 2014. Broadly neutralizing hemagglutinin stalk-specific antibodies require FcgammaR interactions for protection against influenza virus in vivo. Nat Med 20, 143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epperson S, Blanton L, Kniss K, Mustaquim D, Steffens C, Wallis T, Dhara R, Leon M, Perez A, Chaves SS, Elal AA, Gubareva L, Xu X, Villanueva J, Bresee J, Cox N, Finelli L, Brammer L, Influenza Division, N.C.f.I., Respiratory Diseases, C.D.C., 2014. Influenza activity - United States, 2013-14 season and composition of the 2014-15 influenza vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63, 483–490. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermler ME, Kirkpatrick E, Sun W, Hai R, Amanat F, Chromikova V, Palese P, Krammer F, 2017. Chimeric Hemagglutinin Constructs Induce Broad Protection against Influenza B Virus Challenge in the Mouse Model. J Virol 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery B, Zimmerman RK, Gubareva LV, Garten RJ, Chung JR, Nowalk MP, Jackson ML, Jackson LA, Monto AS, Ohmit SE, Belongia EA, McLean HQ, Gaglani M, Piedra PA, Mishin VP, Chesnokov AP, Spencer S, Thaker SN, Barnes JR, Foust A, Sessions W, Xu X, Katz J, Fry AM, 2016. Enhanced Genetic Characterization of Influenza A(H3N2) Viruses and Vaccine Effectiveness by Genetic Group, 2014-2015. J Infect Dis 214, 1010–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florek K, Mutschler J, McLean HQ, King JP, Flannery B, Belongia EA, Friedrich TC, 2020. Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity antibody responses to inactivated and live-attenuated influenza vaccination in children during 2014-15. Vaccine 38, 2088–2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel D, Co M, Ollinger T, Salaun B, Schuind A, Li P, Walravens K, Ennis FA, Vaughn DW, 2021. Non-neutralizing antibody responses following A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza vaccination with or without AS03 adjuvant system. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 15, 110–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway SE, Reed ML, Russell CJ, Steinhauer DA, 2013. Influenza HA subtypes demonstrate divergent phenotypes for cleavage activation and pH of fusion: implications for host range and adaptation. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubareva L, Mohan T, 2020. Antivirals Targeting the Neuraminidase. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Tan GS, Mullarkey CE, A.J. Lee, Lam MM, Krammer F, Henry C, Wilson PC, Ashkar AA, Palese P, Miller MS, 2016. Epitope specificity plays a critical role in regulating antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against influenza A virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 11931–11936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jegaskanda S, Co MDT, Cruz J, Subbarao K, Ennis FA, Terajima M, 2017. Induction of H7N9-Cross-Reactive Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity Antibodies by Human Seasonal Influenza A Viruses that are Directed Toward the Nucleoprotein. J Infect Dis 215, 818–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai A, Yamamoto Y, Nogimori T, Takeshita K, Yamamoto T, Yoshioka Y, 2021. The potential of neuraminidase as an antigen for nasal vaccines to increase cross-protection against influenza viruses. J Virol, JVI0118021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon PE, He W, Mullarkey CE, Bailey MJ, Miller MS, Krammer F, Palese P, Tan GS, 2016. Optimal activation of Fc-mediated effector functions by influenza virus hemagglutinin antibodies requires two points of contact. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E5944–E5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li APY, Cohen CA, Leung NHL, Fang VJ, Gangappa S, Sambhara S, Levine MZ, Iuliano AD, Perera R, Ip DKM, Peiris JSM, Thompson MG, Cowling BJ, Valkenburg SA, 2021. Immunogenicity of standard, high-dose, MF59-adjuvanted, and recombinant-HA seasonal influenza vaccination in older adults. NPJ Vaccines 6, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HY, Wang SC, Ko YA, Lin KI, Ma C, Cheng TR, Wong CH, 2020. Chimeric hemagglutinin vaccine elicits broadly protective CD4 and CD8 T cell responses against multiple influenza strains and subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 17757–17763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen A, Dai YN, McMahon M, Schmitz AJ, Turner JS, Tan J, Lei T, Alsoussi WB, Strohmeier S, Amor M, Mohammed BM, Mudd PA, Simon V, Cox RJ, Fremont DH, Krammer F, Ellebedy AH, 2020. Human Antibodies Targeting Influenza B Virus Neuraminidase Active Site Are Broadly Protective. Immunity 53, 852–863 e857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaweni NM, Olieslagers TI, Rivas IO, Molenbroeck SJJ, Groeneweg M, Bos GMJ, Tilanus MGJ, Voorter CEM, Wieten L, 2018. A comprehensive overview of FCGR3A gene variability by full-length gene sequencing including the identification of V158F polymorphism. Sci Rep 8, 15983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier HE, Nachbagauer R, Kuan G, Ng S, Lopez R, Sanchez N, Stadlbauer D, Gresh L, Schiller A, Rajabhathor A, Ojeda S, Guglia AF, Amanat F, Balmaseda A, Krammer F, Gordon A, 2020. Pre-existing Antineuraminidase Antibodies Are Associated With Shortened Duration of Influenza A(H1N1)pdm Virus Shedding and Illness in Naturally Infected Adults. Clin Infect Dis 70, 2290–2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuley JL, Gilbertson BP, Trifkovic S, Brown LE, McKimm-Breschkin JL, 2019. Influenza Virus Neuraminidase Structure and Functions. Front Microbiol 10, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monto AS, Kendal AP, 1973. Effect of neuraminidase antibody on Hong Kong influenza. Lancet 1, 623–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison BJ, Roman JA, Luke TC, Nagabhushana N, Raviprakash K, Williams M, Sun P, 2017. Antibody-dependent NK cell degranulation as a marker for assessing antibody-dependent cytotoxicity against pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in human plasma and influenza-vaccinated transchromosomic bovine intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. J Virol Methods 248, 7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BR, Kasel JA, Chanock RM, 1972. Association of serum anti-neuraminidase antibody with resistance to influenza in man. N Engl J Med 286, 1329–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez IA, Carlock MA, Allen JD, Owino SO, Moehling KK, Nowalk P, Susick M, Diagle K, Sweeney K, Mundle S, Vogel TU, Delagrave S, Ramgopal M, Zimmerman RK, Kleanthous H, Ross TM, 2017. Impact of age and pre-existing influenza immune responses in humans receiving split inactivated influenza vaccine on the induction of the breadth of antibodies to influenza A strains. PLoS One 12, e0185666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmit SE, Petrie JG, Cross RT, Johnson E, Monto AS, 2011. Influenza hemagglutination-inhibition antibody titer as a correlate of vaccine-induced protection. J Infect Dis 204, 1879–1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushko P, Kort T, Nathan M, Pearce MB, Smith G, Tumpey TM, 2010. Recombinant H1N1 virus-like particle vaccine elicits protective immunity in ferrets against the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. Vaccine 28, 4771–4776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadlbauer D, Zhu X, McMahon M, Turner JS, Wohlbold TJ, Schmitz AJ, Strohmeier S, Yu W, Nachbagauer R, Mudd PA, Wilson IA, Ellebedy AH, Krammer F, 2019. Broadly protective human antibodies that target the active site of influenza virus neuraminidase. Science 366, 499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauer DA, Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Hay AJ, 1991. Amantadine selection of a mutant influenza virus containing an acid-stable hemagglutinin glycoprotein: evidence for virus-specific regulation of the pH of glycoprotein transport vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88, 11525–11529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderven HA, Barr I, Reynaldi A, Wheatley AK, Wines BD, Davenport MP, Hogarth PM, Kent SJ, 2020. Fc functional antibody responses to adjuvanted versus unadjuvanted seasonal influenza vaccination in community-dwelling older adults. Vaccine 38, 2368–2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderven HA, Jegaskanda S, Wheatley AK, Kent SJ, 2017a. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity and influenza virus. Current opinion in virology 22, 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderven HA, Jegaskanda S, Wines BD, Hogarth PM, Carmuglia S, Rockman S, Chung AW, Kent SJ, 2017b. Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity Responses to Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in Older Adults. J Infect Dis 217, 12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viboud C, Grais RF, Lafont BA, Miller MA, Simonsen L, Multinational Influenza Seasonal Mortality Study, G., 2005. Multinational impact of the 1968 Hong Kong influenza pandemic: evidence for a smoldering pandemic. J Infect Dis 192, 233–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Huang B, Wang X, Tan W, Ruan L, 2019. Improving Cross-Protection against Influenza Virus Using Recombinant Vaccinia Vaccine Expressing NP and M2 Ectodomain Tandem Repeats. Virol Sin 34, 583–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss CD, Wang W, Lu Y, Billings M, Eick-Cost A, Couzens L, Sanchez JL, Hawksworth AW, Seguin P, Myers CA, Forshee R, Eichelberger MC, Cooper MJ, 2020. Neutralizing and Neuraminidase Antibodies Correlate With Protection Against Influenza During a Late Season A/H3N2 Outbreak Among Unvaccinated Military Recruits. Clin Infect Dis 71, 3096–3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westgeest KB, de Graaf M, Fourment M, Bestebroer TM, van Beek R, Spronken MIJ, de Jong JC, Rimmelzwaan GF, Russell CA, Osterhaus A, Smith GJD, Smith DJ, Fouchier RAM, 2012. Genetic evolution of the neuraminidase of influenza A (H3N2) viruses from 1968 to 2009 and its correspondence to haemagglutinin evolution. J Gen Virol 93, 1996–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Guo Z, Reber A, Kamal RP, Music N, Gansebom S, Bai Y, Levine M, Carney P, Tzeng WP, Stevens J, York IA, 2016. An influenza A virus (H7N9) anti-neuraminidase monoclonal antibody with prophylactic and therapeutic activity in vivo. Antiviral Res 135, 48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, March, 2018. Up to 650 000 people die of respiratory diseases linked to seasonal flu each year. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Edberg JC, Redecha PB, Bansal V, Guyre PM, Coleman K, Salmon JE, Kimberly RP, 1997. A novel polymorphism of FcgammaRIIIa (CD16) alters receptor function and predisposes to autoimmune disease. J Clin Invest 100, 1059–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara A, Yamayoshi S, Kiso M, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Koga M, Adachi E, Kikuchi T, Wang IH, Yamada S, Kawaoka Y, 2019. Antigenic drift originating from changes to the lateral surface of the neuraminidase head of influenza A virus. Nat Microbiol 4, 1024–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Chung J, Jackson ML, Jackson LA, Petrie JG, Monto AS, McLean HQ, Belongia EA, Gaglani M, Murthy K, Fry AM, Flannery B, Investigators USFV, Investigators USFV, 2016. 2014-2015 Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in the United States by Vaccine Type. Clin Infect Dis 63, 1564–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.