Abstract

A growing number of studies report dermal malignancies mimicking diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs). We reviewed clinical cases reporting malignant tumours misdiagnosed to be DFU aiming to identify factors contributing to misdiagnosis. We systematically searched in PubMed for clinical cases reporting on misdiagnosis of DFU in patients with cancer. A chi‐square analysis was conducted to show the link between the incidence of initial DFU misdiagnosis and patient age, gender and wound duration. Lesions misdiagnosed to be DFU were subsequently diagnosed as melanoma (68% of the cases), Kaposi's sarcoma (14%), squamous cell carcinoma (11%), mantle cell lymphoma, and diffuse B‐cell lymphoma (both by 4%). Older age (≥65 years) was associated with a significantly increased risk of malignancy masked as DFU (OR: 2.452; 95% CI: 1.132 to 5.312; P value = .019). The risk of such suspicion in older patients (age ≥ 65 years) was 145% higher than in younger patients (age < 65 years). Clinicians should maintain a high level of awareness towards potentially malignant foot lesions in elderly patients with diabetes (age ≥ 65).

Keywords: diabetic foot ulcer, malignancy, melanoma, misdiagnosis, skin cancer

1. INTRODUCTION

Skin malignancies and cutaneous manifestations of other types of cancer may not display typical features and mimic benign wounds. Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is a common diabetes mellitus (DM) complication affecting 6% of patients. 1 Diabetic ulcer manifestation is usually explained by an altered immune response, vascular and neurological irregularities and other factors related to diabetes. However, foot ulcers in patients with diabetes may be a symptom of malignancy, especially considering that the risk of developing skin cancer is increased in individuals with DM. 2 , 3

It is well known that it is not always easy to distinguish between chronic ulcers and malignancy. Malignancy can mimic DFUs 4 or ulcers may transform into a malignancy, 5 , 6 complicating the diagnosis. Acral melanoma is especially prone to be misdiagnosed because of its location and attribution to other types of lesions. Sondermann et al analysed 107 patients with melanoma on foot and showed that 30% of patient's foot lesions were incorrectly diagnosed at the first medical visit. Notably, DFUs were one of the most frequent initial misdiagnoses. 7 At the same time, it is well known that misdiagnosis and delay in the diagnosis of malignancies can lead to poor disease outcomes. 8

Difficulties in the diagnosis of plantar malignancies have been recently reviewed that illustrates the complexity of alternative diagnosis. Soon et al showed 18 cases of acral lentiginous melanoma misdiagnosed as wart, callous, fungal disorder, foreign body, blister, non‐healing wound, mole and keratoacanthoma, among other conditions. 9 At the same time, the conjunction of a large number of people living with diabetes and predilection of diabetic patients towards foot ulceration may cause initial clinical suspicion of DFU in diabetic patients whose wounds have malignant nature. Moreover, the problem of differential diagnosis between malignancies and DFU is especially important today because modern approaches for DFU include therapies with growth factors. The presence of the neoplasm at the site of application is a contraindication for the use of growth factors, as is indicated for REGRANEX Gel, the first and only FDA‐approved recombinant platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF) therapy for use on diabetic neuropathic ulcer. 10

The phenomenon of misdiagnosis of DFU in patients with malignancies has never been systematically reviewed, and the factors causing such misdiagnosis have not been statistically analysed. While the problem of malignancies mimicking DFU is not widely discussed in the literature, there is a growing interest of clinicians in increasing awareness towards potentially malignant nature of wounds on feet of diabetic patients. In this article, we describe the first systematic review of clinical cases in which there was a misdiagnosis of DFU, but consequently foot malignancies were diagnosed.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The PubMed database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed) was searched using a combination of keywords to identify articles reporting on misdiagnosis of DFU in patients with cancer. We used a request with keywords indicating (a) sinister tumour (eg, “cancer,” “melanoma,” “sarcoma,” “carcinoma,” “malignancy,” “lymphoma,” etc.), (b) mimicry or misdiagnosis of malignant tumour (eg, “misdiagnosed,” “mistaken,” “false,” “disguised,” “mimicry,” etc.) and (c) site and nature of the lesion (DFU). The full text of the search is available upon request. Searches were completed up to 19 June 2021.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Studies with papers on misdiagnosis of DFU in patients who were consequently diagnosed with cancer were eligible for inclusion. Participants of interest were patients with DM whose foot lesions were at first suspected to be related to diabetes instead of malignant tumours. Only the most recent and complete reports were selected when the same cases were reported in multiple reports to avoid overlap. Studies were excluded if (a) the authors did not report any suspicion of DFU or (b) the differential diagnosis of malignancy omitted DFU. Publications in which misdiagnosis of DFU was reported by the authors of corresponding reports were included. We also included cases in which malignancies were initially misdiagnosed as DFU.

The term “misdiagnosis” was applied to clinical cases in which the authors reported that there was initial, presumptive, preliminary diagnosis of DFU, clinical impression of DFU, suggested clinical diagnosis, or diagnosis on referral.

2.3. Selection of studies

The title and the abstract of all the retrieved articles were reviewed in order to exclude studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining full‐text articles from the first stage of the analysis were reassessed by the same researcher.

2.4. Data extraction

The following data were extracted from studies that met the inclusion criteria: malignancy type, number of patients, DM type and duration, diabetes complications, wound description and duration. Data were extracted from all included studies independently by two members of the review team. Epidemiological data on the distribution of diabetes and DFU depending on age were extracted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention online database 11 and from a large retrospective cohort study. 12

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analysis of case studies was performed using GraphPad Prism v. 7.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). The chi‐square test was used to compare differences among categorical variables. Odds ratio was assessed on the amount of DFU patients' presence in the US population. We are observing papers (2004‐2021), so in 2015 the US population of DFU patients was assessed as 0.944 mln (age 18 < … < 65) and 0.693 mln (age ≥ 65). 1

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results

Three hundred and eighty‐four articles were obtained from PubMed at the first step. A full list of these articles can be retrieved by the authors upon request. Studies not addressing the question of the present systematic review and studies without full‐text articles were excluded. One review article reporting on misdiagnosis and malignant transformation of chronic wounds was identified. No misdiagnosis of DFU was reported in 19 articles. In three reports, the differential diagnosis of malignancy did not include DFU.

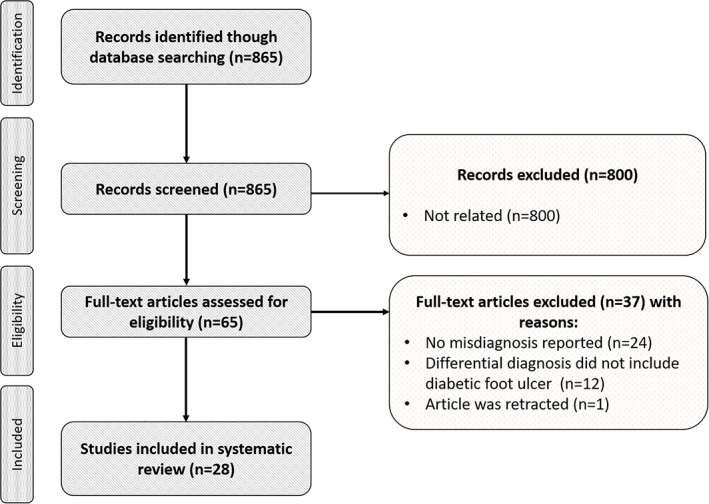

Twenty‐five articles met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. The selected studies were case report articles and were published between 2004 and 2019. The flow chart of the selection process is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the selection process

3.2. Malignancies misdiagnosed as DFUs are linked to the advanced age of patients

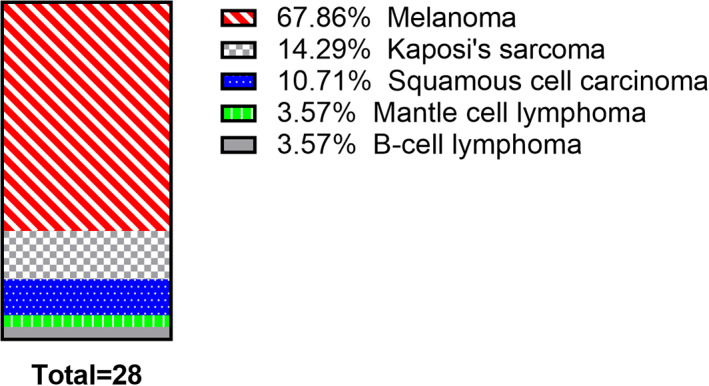

A total of 28 reports reporting on misdiagnosis of DFU in patients whose wounds were subsequently diagnosed as cancer involving 28 patients were distributed according to several different cancer types (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Percentage by cancer type in malignant wounds misdiagnosed to be DFU

Lesions, misdiagnosed to be DFU corresponded to subsequently diagnosed melanoma (including amelanotic ones) in 68% of the cases (19 patients), 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 14% (4 patients) to Kaposi's sarcoma, 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 11% (3 patients) to squamous cell carcinoma, 31 , 32 , 33 4% (one patient) to mantle cell lymphoma, 34 and 4% (1 patient) to diffuse B‐cell lymphoma. 35

All the reports included case studies, and all patients had type 2 diabetes except eight patients, whose diabetes type was not specified. 13 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 36

Nineteen patients were males, and six were females. Gender characteristics of three patients were not indicated. 21 Diabetes duration ranged from 2 to 30 years (mean 14.1 years). Nine patients had diabetes‐related complications, including neuropathy, 14 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 31 peripheral arterial disease, 14 ischaemia and atherosclerotic irregularities. 4 , 36 Three patients did not have diabetes complications, 16 , 23 , 37 but one of them had hepatocellular carcinoma and a family history of melanoma, 37 and another had immunosuppressive treatment prior to hospital submission. 16 No diabetes complication information was presented for nine patients. 8 , 13 , 15 , 21 , 22 , 29 , 32 , 34 , 35 Wound descriptions correspond to the data presented by the authors of included studies. Table 1 shows clinical cases in which wounds, misdiagnosed to be DFU were subsequently diagnosed as cancer. The table also includes patient demographics, diabetes duration and complications, and wound description.

TABLE 1.

Malignancies initially suspected to be diabetic foot ulcers (DFU)

| Case | Reference | Malignancy type | Age/sex | DM duration (y) | DM complications | Wound description | Misdiagnosis confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Black et al 24 | Melanoma | 73 M | n/r | + |

Case of a 73‐year‐old Caucasian male with a 13‐month history of an ungual lesion on his right hallux. Ulcer duration: 13 mo. |

“The lesion was initially treated as a chronic diabetic ulceration with failure to resolve with standard of care.” |

| 2 | Gaskin et al 25 | Melanoma | 57 W | 2 | n/r |

A 57‐year‐old overweight woman presented to The Maria Holder Diabetes Centre for the Caribbean with a non‐healing ulcer of the right heel after being treated by various primary care physicians over the preceding year. Ulcer duration: approximately 1 y. |

“A 57‐year‐old overweight woman presented to The Maria Holder Diabetes Centre for the Caribbean with a non‐healing ulcer of the right heel after being treated by various primary care physicians over the preceding year. The original debridement sample was not examined by a pathologist. Presumably, at the time, there was no clinical suspicion of melanoma.” |

| 3 | Shao et al 33 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 58 M | n/r | n/r | A 58‐year‐old male patient with diabetic foot ulcer was admitted to the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine on December 11, 2018. The patient was treated with local debridement, vacuum sealing drainage treatment, and dressing change and discharged after basic wound healing. |

“The patient, a 58‐year‐old male, was admitted to the Second Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine Burn and Wound Repair Clinic (Wound Treatment Center) on December 11, 2018 for a right‐sided diabetic foot ulcer after repeated debridement and dressing changes for more than 1 mo, with recurrent localised redness and pus flow. On the third day after re‐admission to the hospital, he underwent an invasive surgery on the right foot, during which he saw a deep ulcer on the bottom of the foot with localised hairy and brittle basal tissues, which bled easily when touched. The pathological examination on the 3rd day after surgery reported: squamous cell carcinoma of the right foot, keratinized type.” [Translate from Chinese] |

| 4 | Novodvorsky et al 37 | Lentiginous melanoma | 48 M | n/r | − |

1‐cm diameter ulcer surrounded by patches of dark brown discoloration within 2‐cm diameter, without signs of infection or callus. Wound duration: more than 4 mo. |

Text: “We report a case of a 48‐year‐old man with type 2 diabetes who was referred by his general practitioner to a podiatry‐led foot clinic with a blister over the plantar aspect of the first metatarsophalangeal joint of his left foot. An advice for pressure offloading with a hexagonal shoe was given and he was referred to orthotics for provision of custom‐made insoles and for footwear review.” |

| 5 | Suarez Gonzalez et al 36 | Melanoma | 68 M | n/r | + | Granulated ulcer measuring 4 cm × 3 cm, with no sign of infection. |

The paper's title: “Misdiagnosed Malignant Tumour on an Ischemic Limb” Text: “Herein, the authors report the case of a man who presented with melanoma misdiagnosed as an ulcer to draw awareness of the possible resemblance in presentation of ALM to that of an ulcer.” |

| 6 | Torrence et al 30 | Kaposi's sarcoma | 80 M | n/r | n/r |

1‐cm diameter painful wound. The tumour cells showed diagnostic positive staining for HHV‐8 (human herpes virus 8). Wound duration: 4 mo. |

The paper's title: “A case of mistaken identity: classic Kaposi sarcoma misdiagnosed as a diabetic foot ulcer in an atypical patient” Text: “Classic Kaposi sarcoma is rare in this patient demographic and can be easily misdiagnosed.” |

| 7 | Fu et al 34 | Mantle cell lymphoma | 80 M | n/r | n/r | n/r | Initially, the diagnosis was an infected non‐healing diabetic wound with the possibility of abscess owing to erythema and fluctuance in the affected area. After the MRI assessment, the patient underwent wound biopsy. Pathologic examination of the biopsy specimens showed diffuse proliferation of atypical lymphoid cells. In conclusion, we report the case of a patient who developed subcutaneous nodules and a non‐healing ulcer, which, at first, was treated as a non‐healing diabetic ulcer but later was confirmed to be a skin manifestation of MCL invasion. |

| 8 | Gao et al 14 | Melanoma | 78 F | 8 | + |

Two 0.5‐cm diameter ulcers with pigmented margin. One ulcer with red granulation tissue. A lot of callus around both ulcers, no active drainage, erythema, oedema or other signs of infection. Ulcer duration: 6 mo. |

Text: From January 2003 to December 2014, 1132 in‐patients with diabetic foot and 177 in‐patients with ALM were admitted to our hospital. However, one case of them was misdiagnosed as diabetic foot ulcer in this period. |

| 9 | Detrixhe et al 13 | Melanoma | 64 M | n/r | n/r | Ulcerating lesion with an area of blue–brown pigmentation in the periphery of the ulceration. | The clinical hypotheses accompanying the punch biopsies were nodular basal cell carcinoma, fungal intertrigo, keratoacanthoma, lichenoid keratoma (defined as chronically irritated seborrheic keratosis), diabetic foot ulcer. Case 1b (suggested clinical diagnosis was diabetic foot ulcer) was followed by a diabetic foot specialist for several months before dermatological advice for absence of wound healing. |

| 10 | Iacopi et al 35 | B‐cell lymphoma | 76 M | 20 | n/r | Painful ulcer, wound bed intensively vascularised and partially covered by hyperkeratosis. | Here we report the case of a foot lesion misdiagnosed as DFU but actually caused by diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma |

| 11 | Kaneko et al 18 | Amelanotic melanoma | 80 M | 20 | n/r |

Intractable ulcer. Ulcer duration: 5 mo. |

An 80‐year‐old man was referred to our plastic and reconstructive surgery clinic because of a 5‐month history of an intractable ulcer on the left heel. He had a 20‐year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Under the diagnosis of diabetic ulcer, for the first half of the year, he received topical therapy with several ointments for the skin ulcer. Nevertheless, the skin ulcer was intractable 2 mo after the initial treatment began, suggesting a different skin condition. By performing an incisional biopsy of an ulcer specimen, a diagnosis of malignant melanoma was made. To the best of our knowledge, four other cases of amelanotic ALM were previously misdiagnosed as intractable diabetic skin ulcers in the initial clinical diagnosis, as in our case. |

| 12 | Mansur et al 4 | Melanoma | 87 F | n/r | + |

Painless ulcer that had begun as a dark spot under the nail and small ulcer nearby. Ulcer duration: 2.5 y. |

We describe here an elderly female patient treated for a non‐healing foot ulcer interpreted as a diabetic ulcer, which after 2 y was diagnosed as acral melanoma with satellitosis. We describe here a female diabetic patient who presented with acral melanoma with satellitosis masquerading as a diabetic ulcer for 2 y. In our case, because of underlying diabetes mellitus and old age, the ulcer was attributed to ischaemic necrosis due to microangiopathy, precipitated by diabetes and atherosclerosis. As the physicians taking care of the patient were not dermatologists, the nature of the ulcer was not recognised properly. Moreover, although our patient had been having satellite lesions on the foot for nearly a year, neither the patient nor the physicians paid attention to them. |

| 13 | Park et al 32 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 57 M | n/r | n/r |

Tender shallow, oval‐shaped, 0.7 × 0.3‐cm ulcer with purulent discharge. Ulcer duration: 6 mo. |

We gave oral antibiotics with wound dressing, under the clinical impression of a DM foot ulcer accompanying secondary infection and lymphadenitis. Despite 6 weeks of treatment, a new tender erythematous patch with swelling was discovered on the right thigh. A skin biopsy was performed on the right thigh and was reported as consistent with cellulitis. We switched the oral antibiotic to levofloxacin, but the lesion showed no improvement over 2 weeks. Therefore, we decided to perform another skin biopsy on the right fifth toe. The histopathologic findings showed infiltration of atypical pleomorphic cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, with invasion into the dermis. In our case, as the patient had ulceration with purulent discharge, he received conservative management including wound dressing and oral antibiotics under the diagnostic impression of DM foot ulcer with secondary infection. However, the lesions did not respond to this treatment, and after a skin biopsy of the toe and additional evaluation, we made the correct diagnosis of SCC of the toe. |

| 14 | Zaidi et al 26 | Melanoma | 67 M | 9 | Diabetes has been linked with malignancies like colon, rectum, liver, biliary tract, pancreas, kidney, leukaemia and melanoma. Melanoma can sometimes manifest as a diabetic foot ulcer. We describe an elderly male with type 2 diabetes, who had presented to us with a non‐healing wound at the right heel, that later turned out to be an invasive malignant melanoma. | “Melanoma can sometimes manifest as a diabetic foot ulcer. We describe an elderly male with Type 2 diabetes, who had presented to us with a non‐healing wound at the right heel, that later turned out to be an invasive malignant melanoma.” | |

| 15 | Sivaprakasam et al 29 | Kaposi's sarcoma | 70 M | n/r | n/r | Purplish nodules. | Personal communication. |

| 16 | Hussin et al 17 | Melanoma | 52 F | 15 | + |

Ulcer size 3 × 3 cm, hyper‐granulating base, the skin surrounding the ulcer was pigmented, and there were no signs of local infection. Ulcer duration: 4 mo. |

We present two patients with diabetes mellitus and malignant melanomas of the foot initially diagnosed as DFU. A 52 y old Malay woman presented with a non‐healing ulcer of 4 mo duration. She had type 2 DM for 15 y on oral medication. She sustained a small puncture wound on the sole of her left foot from stepping on a sharp object. This ulcerated and was seen by her family doctor who diagnosed a DFU. |

| 17 | Koo et al 28 | Kaposi's sarcoma | 88 M | 12 | + | Hypergranulating wound exuding serous exudate, asymmetrical in shape, atypical in appearance. | 88‐year‐old male with type 2 diabetes mellitus, presented at Liverpool Hospital High Risk Foot Service with a non‐healing wound on his right foot. The patient presented with a plantar wound on his right foot, which had the appearance of a neuropathic ulcer, possibly relating to his diabetes.The presenting lesion in this case was diagnosed on referral as a neuropathic foot ulcer. Due to the similarity classic Kaposi sarcoma has with other conditions, preliminary misdiagnoses could have been: pyogenic granuloma, nodular melanoma, melanocytic nevi or arteriovenous malformations. |

| 18 | Thomas et al 22 | Melanoma | 81 M | n/r | n/r | Painful ulcer with foul smelling drainage, size 6 × 5 cm. The ulcer was necrotic, black with bleeding and minimal purulent drainage. | The patient was started on oral antibiotics with local wound care and surgical consultation requested. Outpatient surgical evaluations showed a black eschar with punctuate areas of bleeding after the removal of the eschar. The patient was admitted to the hospital for surgical debridement of the presumptive diabetic necrotic ulcer. |

| 19 | Tomešová et al 38 | Melanoma | 60 M | 6 | − | The paper describes a history of a male diabetic patient with an atypical course of the foot defect. |

“The defect was considered and treated as DFU for almost 4 mo. Atypical was the pain of the terrain defect of diabetic neuropathy, the absence of signs of inflammation, the appearance of the defect and non‐healing in complex treatment. All these atypics could lead us to a correct diagnosis [malignant melanoma]”. [Translate from Polski] |

| 20 | Guarneri et al 16 | Melanoma | 86 M | 30 | − | Painless ulcer, size 2.5 × 1.9 cm, slightly hyperkeratotic, partly ulcerated mass with no peripheral erythema, warmth or tenderness on palpation in the surrounding area. | The tumour was diagnosed as a diabetic foot ulcer by both his general physician and an orthopaedist and managed with regular debridement, systemic antibiotics and pressure‐relieving footwear. Incisional biopsies of the lesion were obtained, and histopathological examination showed the dermis to be diffusely infiltrated by a malignant ulcerated mass. In the present case, the initial verrucous appearance of the lesion had favoured its misdiagnosis as a small plantar wart. Later, the ulceration, referred to an accidental trauma by the patient, and the slow healing were disregarded by the general physician because of the diabetes and the concomitant immunosuppressive regimen. |

| 21 | Torres et al 8 | Melanoma | 54 M | n/r | n/r |

Painless ulcer, 2.5 cm diameter with pigmented macule, with irregular borders in margins. Ulcer duration: 12 mo. |

A 54‐year‐old male patient, with type 2 diabetes mellitus, was referred to our department with a painless, non‐healing ulcer of 12 mo duration under the right fifth metatarsal bone. The ulcer had been managed for months as a diabetic foot ulcer with local wound care, antibiotics and pressure‐relieving footwear.An incisional biopsy was taken from the lesion and the histopathological examination showed a malignant melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.3 mm. |

| 22 | Caminiti et al 27 | Kaposi's sarcoma | 83 F | n/r | + | Roundish lesion (measuring approximately 15 mm in diameter). The lesion showed keratotic but not undermined edges; the ulcer had mushrooming granulation tissue. | In this report, the authors describe the case of a patient with Kaposi's sarcoma that was initially misdiagnosed as a plantar ulcer. |

| 23 | Pereyra‐Rodríguez et al 20 | Melanoma | 58 F | n/r | + |

Ulcer size 4 × 1.5 cm, slightly hyperpigmented nodule with a central ulceration. Wound duration: 7 mo. |

The patient had been seen several times by a primary care physician and received topical antibiotic treatment for the presumptive diagnosis of mal perforans from a diabetic neuropathy. When examined, a 4 × 1.5 cm slightly hyperpigmented nodule was found with a central ulceration located on the distal portion of the left foot sole. An incisional biopsy was obtained which included a focus of dark pigmentation. Histological examination showed tumoural melanocytic cell nests filling and expanding the papillary dermis with atypical mitosis and melanoma cells infiltrating up through the epidermis. |

| 24 | Kong et al 31 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 73 M | n/r | + |

Painful ulcer discharging pus. Ulcer duration: 7 mo. |

73‐year‐old Caucasian man with type 2 diabetes was referred with a 7‐month history of an ulcer on his left heel. His left heel had ulcerated on two previous occasions as a result of fissures and using his heel to prop himself up in bed. The ulcer was superficial and initially showed signs of healing, but it subsequently became very painful and began to discharge pus. A biopsy from the surgical debridement showed moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). We have previously reported cases of malignant melanoma diagnosed in patients referred to our foot ulcer clinic (4,5); five of seven patients had diabetes, and their ulcers were initially thought to be diabetic foot ulcers, as was the case in this patient. |

| 25 | Rogers et al 21 | Melanoma | 48 M | n/r | n/r |

Painless ulcer with mushrooming granulation tissue and areas of intact epidermis in a lenticular fashion over the wound bed. Wound duration: 18 mo. |

A male patient aged 48 y with type 2 diabetes presented with a painless non‐healing ulcer of 18 mo duration under his right first metatarsal head. The ulcer was not a typical appearing neuropathic foot ulcer and had mushrooming granulation tissue and areas of intact epidermis in a lenticular fashion over the wound bed.An incisional biopsy was taken from the foot lesion, which showed a poorly differentiated melanoma covered by an intact epidermis and granulation tissue. |

| 26 | Yeşil et al 23 | Amelanotic melanoma | 71 M | 17 | − | Painless ulcer, 4 cm diameter, no erythema, tenderness or warmth on palpation in wound area. |

A 71‐year‐old male patient with a 17‐year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to our clinic with atypical hypergranulation and painless ulcer under his left fifth metatarsal head. He was previously admitted by another physician, and the lesion was diagnosed as a diabetic foot ulcer. He went on to have an incisional punch biopsy of his left foot ulcer, which showed the dermis to be diffusely infiltrated by malignant tumour, displaying melan‐A positivity. The diagnosis was malignant melanoma. |

| 27 | Kong et al 19 | Melanoma | 69 M | 2 | + |

Painful ulcer, atypical hyper‐granulation around edges of the ulcer Wound duration: 2 mo This article describes four cases of melanoma misdiagnosed as DFU, but the characteristics of the patients are presented for only one case. |

He had developed the ulcer in January 2003, and had been receiving podiatry care in the community. In addition to this patient, we have diagnosed five other cases of malignant melanoma over the past 4 y which were referred to our diabetes foot ulcer clinic. Two of the patients did not have diabetes. In four of our patients who had diabetes, the lesion was initially misdiagnosed as a diabetic foot ulcer. |

| 28 | Gregson et al 15 | Amelanotic melanoma | 76 F | 15 | + |

1‐cm diameter non‐pigmented ulcer with callus‐like periphery. Wound duration: 15 y. |

We report a case of amelanotic malignant melanoma, which presented late due to the ulcer being falsely attributed to diabetes. The diagnosis was missed despite the patient having seen diabetic, vascular and orthopaedic specialists. |

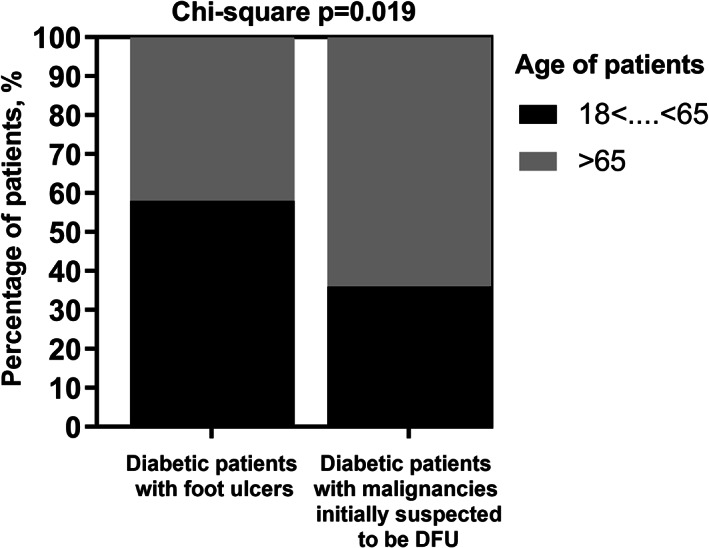

To examine if there is a link between the incidence of DFU initial misdiagnosis and patient age, gender and wound duration, we conducted a chi‐square analysis to compare differences among categorical variables. No associations were found between gender and wound duration and the incidence of such clinical suspicion.

There was a significant association between patient age and the incidence of initial clinical suspicion of DFU in patients whose wounds have malignant nature (OR: 2.452; 95% CI: 1.132 to 5.312; P value = .019). The risk of such suspicion in older patients (age ≥ 65 years) was 145% (2.45 fold) higher than in younger patients (age < 65 years) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of patients with DFU versus patients with malignancies misdiagnosed to be DFU is dependent on age

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we provide a systematic review of clinical cases reporting malignancies misdiagnosed to be DFU. Our main finding was that advanced age increases the odds of initial suspicion of DFU in patients subsequently diagnosed with cancer. We found that being at age ≥ 65 years was associated with an increased incidence of such suspicion (OR: 2.452; 95% CI: 1.132 to 5.312; P value = .019). This result suggests that clinicians should be especially attentive when determining wound aetiology in elderly patients with DM. Our result is consistent with Mansur et al 4 and Bennett et al, 39 who suggested that misdiagnosis occurs predominantly in the sixth decade of life, and Iacopi et al, 35 who suggested that advanced patient age is an indication to challenge the wound aetiology and perform a biopsy.

Some of the reasons for initial suspicion of DFU in patients with cancer have previously been described in the literature. What we know is that foot ulcers are one of the most common DM complications affecting 6% of patients with diabetes 1 ; consequently, because of such frequency, clinicians may at first attribute foot wounds to diabetic complications instead of malignancies. Gao et al suggested that when a foot lesion is present, patients and their health care providers may not readily consider melanoma as a diagnosis because of the low incidence of acral lentiginous melanoma. 14 At the same time, malignant tumours may not manifest typical features covered by ABCD mnemonic aid (asymmetry, border, colour, diameter) 4 , 8 , 14 , 21 or ABCDE (asymmetry, border, colour, diameter, evolution) 40 diagnostic algorithms used for its identification, and may possess the ability to mimic chronic or benign 18 wounds, including DFU, what complicates accurate and timely diagnosis. 28 Kong et al also suggested that acral melanoma can be misdiagnosed because it does not fit the changing mole pattern as well as because of its less common location 19 and strong similarity with diabetic ulcer. 31

It is possible that malignant aetiology of a wound may not be identified at first also because clinicians providing care for diabetic patient are generally not dermatologists, which has been suggested by Mansur et al. 4 Interestingly, in a case report of Gregson, amelanotic malignant melanoma was missed despite the patient seeing diabetic, vascular, and orthopaedic specialists. 15 Therefore, it is important to perform specific educational efforts for non‐dermatologists 18 and promote consultations with multidisciplinary teams.

Gregson et al first mention of malignancy falsely attributed to DFU was made in 2004. 15 The most recent report on malignancy misdiagnosed as DFU was published in 2019 by Suarez Gonzalez et al who described a case on melanoma misdiagnosed as ischaemic DFU. 36 These data suggest that despite recent medical progress and modern, effective diagnostic tools such as dermoscopy and biopsy, diagnostics of sinister tumours in diabetic patients is still challenging.

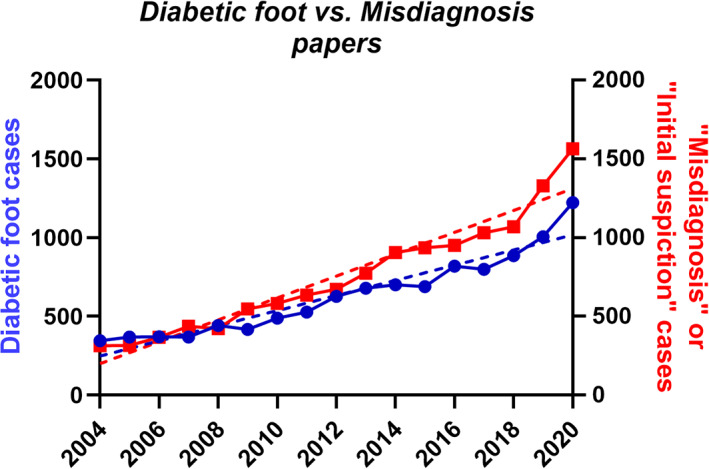

Figure 4 shows the dramatic increase in the number of publications on DFU treatment: from 346 and 700 reports per year in 2004 and 2014, respectively, to 1223 in 2020, achieving more than 5000 (5421) reports for the last 6 years, reflecting the rising interest in this problem.

FIGURE 4.

The numbers of publications on DFU treatment (red) and articles mentioning the words “Misdiagnosis” or “Initial suspicion” (blue)

While the number of published reports on initial misdiagnosis is not large (28 reports for the last 6 years, that is, 0.52% from the total number of DFU reports), our study shows that this problem is not uncommon. It is likely that the real number of malignancies misdiagnosed to be DFU is substantially larger compared with what so far has been published. Figure 4 also suggests a trending growth in the number of articles mentioning the words “Misdiagnosis” or “Initial suspicion”. We consider that such trends display not decreased diagnostic accuracy but upgrowing attention to the overall misdiagnosis problem, in particular about malignant wounds misdiagnosed as DFU. Considering that the number of people living with diabetes is growing rapidly and is going to reach 642 million by 2040, 41 and that several meta‐analyses have shown that diabetic patients face an increased risk of developing skin cancer, 2 , 3 the number of cases, in which malignant wounds are going to be misdiagnosed as DFU may also increase.

One potentially underappreciated similarity between cancer and foot ulcers is that both can recur at anatomical locations distinct from the primary occurrence, albeit with different physiological mechanisms. 42 Furthermore, chronic ulcers in diabetic feet are susceptible to malignant transformation. 43 A heightened index of suspicion for a malignant process in the foot of diabetic patients is necessary when standard of care fails to lead to improvement or resolution. 24

The largest number of reports on cancer misdiagnosed to be DFU is dedicated to melanoma. Only a few published articles described cases of carcinoma, sarcoma and even T‐cell, B‐cell and mantle cell lymphomas initially attributed to DFU. However, this does not mean that melanoma is more prevalent than non‐melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in diabetic patients, nor that melanoma is mimicking DFU more frequently than NMSC. The summarised cases in this review only highlight the problem of malignancies mimicking DFU, but they are not sufficient to make any conclusions about what type of cancer is misdiagnosed to be DFU more often. Relevant epidemiological studies are needed to establish the real number of malignancies misdiagnosed to be DFU.

In the present study, we tried to create a risk‐factor profile to raise clinician's awareness towards a certain group of patients, and we showed that age is an important risk factor. Our study confirms the idea that in older patients the odds of initial suspicion of DFU instead of cancer is high due to the strong ability of cancer to mimic diabetic foot ulcers. We could not establish or rule out the link between the presence of diabetic complications and the ulcer malignisation. Other risk factors could be immunosuppressive treatment, which has undergone several patients in the misdiagnosed cohort prior to the medical consultation regarding the ulcer, 15 , 16 and the history of other malignancies of the patients and their family members, indicated in some clinical cases. 28 , 37 However, these risk factors need further epidemiological evaluation. Another serious risk factor of DFU malignisation could be unhealthy diet\lifestyle as it was shown for incidence of pancreatic cancer in diabetic patients 44 ; however, we did not find any dietary mention in cited articles on DFU misdiagnoses, concluding that doctors still underestimate the influence of a healthy lifestyle on patients' disease outcome. We could not establish a statistically significant link between gender and the incidence of initial suspicion of DFU because of the small number of included articles. However, Soon et al analysed cases of acral lentiginous melanoma mimicking benign disease and showed an equal frequency of misdiagnosis between genders, 9 and in the study by Sondermann, acral melanoma was initially misdiagnosed in a similar number of males and females. 7

In summary, here we discuss the uncommon but severe problem of malignant tumours misdiagnosis to be DFUs with a focus on risk factors contributing to such suspicion. While the number of published cases is still small, and partly inconclusive, there is an increasing number of such reports. Further systematic studies are warranted on this seemingly growing diagnostic phenomenon.

5. CONCLUSION

The risk of misdiagnosis of DFU in patients whose wounds have malignant nature is significantly higher in older patients with DM. Our recommendation is that clinicians should maintain a high level of awareness towards potentially malignant foot lesions in elderly patients with DM (age ≥ 65) to make a timely and accurate diagnosis and to avoid the application of growth factors at the site of neoplasm.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that we have no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Alexey V. Lyundup, Helgi B. Schiöth, and Ilya D. Klabukov designed the study. Alexey V. Lyundup and Ilya D. Klabukov oversaw the literature search and data analysis. Maxim V. Balyasin and Ilya D. Klabukov did the statistical analyses. Alexey V. Lyundup, Maxim V. Balyasin, Helgi B. Schiöth, and Ilya D. Klabukov drafted the manuscript. Alexey V. Lyundup, Nadezhda V. Maksimova, Maxim V. Balyasin, Marina V. Kovina, Tatiana G. Dyuzheva, Helgi B. Schiöth, and Ilya D. Klabukov contributed to key data interpretation. Sergey A. Yakovenko and Svetlana A. Appolonova collected data for Figure 4. Nadezhda V. Maksimova, Alexey V. Lyundup, Marina V. Kovina, Mikhail E. Krasheninnikov, Tatiana G. Dyuzheva, Helgi B. Schiöth, and Ilya D. Klabukov provided essential corrections and critically revised the manuscript. The final version of the paper has been seen and approved by all the authors. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Alexey Fayzullin (Laboratory of Experimental Morphology, Institute for Regenerative Medicine of Sechenov University) for providing expert consultation on the pathological aspects of melanoma and other types of cancer. This paper has been supported by the RUDN University Strategic Academic Leadership Program. Part of this work was financed by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation within the framework of state support for the creation and development of World‐Class Research Centers «Digital Biodesign and Personalised Healthcare» (No: 075–15–2020‐926).

Lyundup AV, Balyasin MV, Maksimova NV, et al. Misdiagnosis of diabetic foot ulcer in patients with undiagnosed skin malignancies. Int Wound J. 2022;19(4):871‐887. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13688

Funding information Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, Grant/Award Number: 075‐15‐2020‐926

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data and materials support their published claims and comply with field standards.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhang P, Lu J, Jing Y, Tang S, Zhu D, Bi Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Med. 2017;49(2):106‐116. 10.1080/07853890.2016.1231932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Qi L, Qi X, Xiong H, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and risk of malignant melanoma: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of cohort studies. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(7):857‐866. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tseng HW, Shiue YL, Tsai KW, Huang WC, Tang PL, Lam HC. Risk of skin cancer in patients with diabetes mellitus: a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine. 2016;95(26):e4070. 10.1097/md.0000000000004070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mansur AT, Demirci GT, Ozel O, Ozker E, Yıldız S. Acral melanoma with satellitosis, disguised as a longstanding diabetic ulcer: a great mimicry. Int Wound J. 2016;13(5):1006‐1008. 10.1111/iwj.12481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Panda S, Khanna S, Singh SK, Gupta SK. Squamous cell carcinoma developing in a diabetic foot ulcer. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2011;10(2):101‐103. 10.1177/1534734611412001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Priesand SJ, Holmes CM. Malignant transformation of a site of prior diabetic foot ulceration to Verrucous carcinoma: a case report. Wounds. 2017;29(12):E125‐E131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sondermann W, Zimmer L, Schadendorf D, Roesch A, Klode J, Dissemond J. Initial misdiagnosis of melanoma located on the foot is associated with poorer prognosis. Medicine. 2016;95(29):e4332. 10.1097/md.0000000000004332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Torres T, Rosmaninho A, Caetano M, Selores M. Malignant melanoma misdiagnosed as a diabetic foot ulcer. Diabet Med. 2010;27(11):1302‐1303. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soon SL, Solomon AR Jr, Papadopoulos D, Murray DR, McAlpine B, Washington CV. Acral lentiginous melanoma mimicking benign disease: the Emory experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(2):183‐188. 10.1067/mjd.2003.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. SmithNephew Regranex . Available from https://www.smith-nephew.com/key-products/advanced-wound-management/regranex-becaplermin-gel/.

- 11. Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Available from https://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/diabetes/DiabetesAtlas.html.

- 12. Al‐Rubeaan K, Al Derwish M, Ouizi S, et al. Diabetic foot complications and their risk factors from a large retrospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0124446. 10.1371/journal.pone.0124446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Detrixhe A, Libon F, Mansuy M, et al. Melanoma masquerading as nonmelanocytic lesions. Melanoma Res. 2016;26(6):631‐634. 10.1097/cmr.0000000000000294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gao W, Chen D, Ran X. Malignant melanoma misdiagnosed as diabetic foot ulcer: a case report. Medicine. 2017;96(29):e7541. 10.1097/md.0000000000007541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gregson CL, Allain TJ. Amelanotic malignant melanoma disguised as a diabetic foot ulcer. Diabet Med. 2004;21(8):924‐927. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guarneri C, Cannavò SP, Bevelacqua V, Urso C. A false diabetic foot ulcer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(10):1964‐1966. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03610_3.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hussin P, Loke SC, Noor FM, Mawardi M, Singh VA. Malignant melanoma of the foot in patients with diabetes mellitus‐a trap for the unwary. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67(4):422‐423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaneko T, Korekawa A, Akasaka E, Nakano H, Sawamura D. Amelanotic acral lentiginous melanoma mimicking diabetic ulcer: a challenge to diagnose and treat. Eur J Dermatol. 2016;26(1):107‐108. 10.1684/ejd.2015.2695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kong MF, Jogia R, Jackson S, Quinn M, McNally P, Davies M. Malignant melanoma presenting as a foot ulcer. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1750. 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67701-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pereyra‐Rodríguez JJ, Gacto‐Sánchez P. An ulcer of the foot. Neth J Med. 2009;67(8):336‐337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rogers LC, Armstrong DG, Boulton AJ, Freemont AJ, Malik RA. Malignant melanoma misdiagnosed as a diabetic foot ulcer. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):444‐445. 10.2337/dc06-2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thomas S, Meng YX, Patel VG, Strayhorn G. A rare form of melanoma masquerading as a diabetic foot ulcer: a case report. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2012;2012:502806. 10.1155/2012/502806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yeşil S, Demir T, Akinci B, Pabuccuoglu U, Ilknur T, Saklamaz A. Amelanotic melanoma misdiagnosed as a diabetic foot ulcer. J Diabetes Complications. 2007;21(5):335‐337. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2006.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Black AT, Lahouti AH, Genco IS, Yagudayev M, Markinson BC, Spielfogel WD. A rare case of Osteoinvasive Amelanotic melanoma of the nail unit. Skin Appendage Disord. 2021;7:139‐143. 10.1159/000512331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gaskin DA, Brathwaite D, Depeiza N, Gaskin PS, Ward J. Spindle cell melanoma presenting as an ulcer in a Black diabetic. Case Rep Pathol. 2020;2020:3083195. 10.1155/2020/3083195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zaidi MS, Hassan A, Ouizi S. Can a diabetic foot be malignant? J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(11):1487‐1489. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27812075/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Caminiti M, Clerici G, Quarantiello A, Curci V, Faglia E. Kaposi's sarcoma misdiagnosed as a diabetic plantar foot ulcer. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2009;8(2):120‐122. 10.1177/1534734609334810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koo E, Walsh A, Dickson H. Red flags and alarm bells: an atypical lesion masquerading as a diabetic foot ulcer. J Wound Care. 2012;21(11):550‐552. 10.12968/jowc.2012.21.11.550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sivaprakasam V, Chima‐Okereke C. An interesting case of 'diabetic foot ulcer' in an HIV‐positive patient. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(4):285‐287. 10.1177/0956462414534826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Torrence GM, Wrobel JS. A case of mistaken identity: classic Kaposi sarcoma misdiagnosed as a diabetic foot ulcer in an atypical patient. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;5:8. 10.1186/s40842-019-0083-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kong MF, Jogia R, Nayyar V, Berrington R, Jackson S. Squamous cell carcinoma in a heel ulcer in a patient with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(7):e57. 10.2337/dc08-0284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park HC, Kwon HI, Kim HW, Kim JE, Ro YS, Ko JY. A digital squamous cell carcinoma mimicking a diabetic foot ulcer, with early inguinal metastasis and cancer‐related lymphedema. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38(2):e18‐e21. 10.1097/dad.0000000000000412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shao JM, Wang XG, Yu CH, Han CM. Teicoplanin‐induced hypersensitivity syndrome in a diabetic foot patient with malignant ulcer. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2020;36(8):747‐750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fu P, Mercado D, Malezhik V, Mannan A. Case study: rare case of mantle cell lymphoma with Extranodal involvement in the foot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;56(5):1104‐1108. 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iacopi E, Coppelli A, Goretti C, Loggini B, Piaggesi A. Type 2 diabetic patient with a foot ulcer as initial manifestation of diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma: a case report. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;115:130‐132. 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Suarez Gonzalez LA, Del Canto PP, Cerviño Alvarez J, Alvarez Fernandez LJ. Misdiagnosed malignant tumor on an ischemic limb. Wounds. 2019;31(2):E12‐e13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Novodvorsky P, Arshad MF, Heyes S, Gandhi R. Non‐healing 'diabetic' ulceration which turned out to be a lentiginous melanoma: a case from a diabetic foot clinic. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:e228649. 10.1136/bcr-2018-228649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tomešová J, Lacigová S, Cechurová D, Gruberová J, Rušavý Z. Unusual cause of foot defect in patient with diabetes mellitus. Vnitr Lek. 2012;58(11):875‐877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bennett DR, Wasson D, MacArthur JD, McMillen MA. The effect of misdiagnosis and delay in diagnosis on clinical outcome in melanomas of the foot. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179(3):279‐284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bristow IR, Acland K. Acral lentiginous melanoma of the foot and ankle: a case series and review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Res. 2008;1(1):11. 10.1186/1757-1146-1-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. International Diabetes Federation . IDF Diabetes Atlas. 9th ed; Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2019. Available from www.diabetesatlas.org [Google Scholar]

- 42. Petersen BJ, Rothenberg GM, Lakhani PJ, et al. Ulcer metastasis? Anatomical locations of recurrence for patients in diabetic foot remission. J Foot Ankle Res. 2020;13(1):1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dörr S, Lucke‐Paulig L, Vollmer C, Lobmann R. Malignant transformation in diabetic foot ulcers—case reports and review of the literature. Geriatrics. 2019;4(4):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mills PK, Beeson WL, Abbey DE, Fraser GE, Phillips RL. Dietary habits and past medical history as related to fatal pancreas cancer risk among Adventists. Cancer. 1988;61(12):2578‐2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials support their published claims and comply with field standards.