Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic created stressful working conditions for nurses and challenges for leaders. A survey was conducted among 399 acute and ambulatory care nurses measuring availability of calming and safety resources, perceptions of support from work, and intent to stay. Most nurses reported intent to stay with their employer, despite inadequate safety and calming resources. High levels of support from work were significantly influenced nurses’ intent to stay. Leadership actions at the study site to provide support are described, providing context for results. Nurse leaders can positively influence intent to stay through consistent implementation of supportive measures.

Key Points.

-

•

Keep communication open. Keep people informed. Do it consistently and frequently

-

•

Find ways for everyone to ask questions and convey needs. Be ready to deploy resources based on reported needs

-

•

Nursing leadership can positively impact nurse retention by addressing situational needs and sending consistent messaging and resources for support

Nurse leaders are increasingly challenged to retain nurses and maintain a stable workforce. The growing nursing shortage1 , 2 negatively affects both organizational finances3 and patient outcomes.4 The percent of hospital nurses leaving their jobs increased substantially from 14.6% in 2016 to 18.7% in 2020.5 Conditions precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic have both exacerbated the need for nursing workforce stability and highlighted the role of leadership and organizational support in nurse retention. Nurse retention is consistently predicted by quality of leadership and elements of the work environment influenced by leaders.6, 7, 8, 9 Effective leadership may take different forms, depending on situational requirement. In times of crisis and change, distribution of leadership through various levels of the organization is integral to successful change navigation.10 The COVID-19 pandemic created such a situation of change, and organization-level leadership was needed to provide resources needed for staff safety and well-being.11 , 12

Nurses contended with high patient loads and acuity, uncertainty about viral spread and risk of infection, and rapidly evolving global and local events during the pandemic.13 , 14 Supply chain disruptions and a scarcity of personal protective equipment (PPE) in many health care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic15 lead to tangible concerns for safety among nurses and other health care workers.16 Safety became a priority concern for nurses17 contributing to increased distress, anxiety,18 , 19 burnout, and turnover intention.19

A robust body of literature exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the nursing workforce has already emerged. Yet, the impact of COVID-19 has varied geographically in both infection and hospitalization rates. At the study site, the University of Kansas Health System (TUKHS) located in the United States Midwest, capacity constraints had not yet been experienced when data collection for this study began in mid-2020. Thus, leadership was able to focus organizational efforts on deploying protective strategies. Our primary aim is to explore relationships between organizational support and safety and calming elements of the workplace on intent to stay with their current employer during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our secondary aim is to illustrate the role of organizational support, actions undertaken in a health care setting, and their effect on nurses’ intent to stay with their employer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This study was an academic-practice collaboration between nursing leadership at TUKHS and nurse researchers at the University of Kansas School of Nursing. A cross-sectional, descriptive survey design was used to collect study data at TUKHS. TUKHS provides multiple care levels and specialties across urban and suburban locations. A total of 3447 nurses were invited to participate across ambulatory and acute care settings. Both ambulatory and acute care settings were included due to similarities in nurse characteristics, the nature of their nursing work, and exposure to COVID-19 patients. Nurses were recruited via an electronic link to a REDCap™ survey sent in institutional email from the TUKHS Chief Nursing Officer between July and September 2020. Data collection for this study was initiated four months after the first local cases were reported in 2020. During data collection, the daily census of patients confirmed as COVID-19 positive ranged between 20 and 80. Analyses focused on the subset of nurses that reported providing direct patient care and answered the environment of care questions. Ethical approval was obtained through the University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Measures used in this study were developed and validated in three phases by staff nurses and subject matter experts. Items relating to safety and calming features of the workplace were developed by the Department of Architecture faculty at the University of Kansas.

Demographics

Participants were asked their age, sex, race, ethnicity, and highest level of education. In addition, participants indicated if they provided direct patient care (Yes, Sometimes, No), if they worked in an ambulatory or acute care setting, and if they were a licensed practical nurse (LPN) or a registered nurse (RN) (Yes, No).

Safe Environment

Safety features of the work environment (Safe Environment), relevant to delivering patient care in COVID-19, were measured using the question “Does your unit or department provide a safe environment for you to deliver healthcare services to COVID-19 or potential COVID-19 patients?” The six Yes:No response options were as follows: (1) Has dedicated PPE donning and doffing area; (2) A one-way flow suite that allows doffing in a designated area separate from that of donning can reduce the risk of contamination and disease spread to staff; (3) Has enough negative-pressure rooms for COVID-19 or potential COVID-19 patients; (4) Has enough hand hygiene stations throughout the unit, easily visible and accessible to nurses; (5) Has separate waiting and screening areas for potential COVID-19 patients; and (6) Has enough space to allow social distancing between patients and staff, and among staff.

Calm Environment

Calming features of the workplace (Calm Environment) were measured by the question, “Does your care space provide a calm environment to reduce your stress?” The five Yes:No response options were (1) Has a staff respite area away from the treatment zone; (2) Provides positive distractions such as arts and/or music; (3) Has views of nature; (4) Has low noise; and (5) Has natural light.

Support From Work

The item measuring Support from Work was generated by TUKHS staff nurses during the second round of instrument validation and then tested during the third round of validation. Front-line nurses interviewed for item validation felt strongly that nurse well-being could not be separated from feeling supported at work and that feeling supported means different things to different people. Organizational support can be provided within relationships (e.g., increased quality or quantity of communication from nurse leaders), programs (e.g., Employee Assistance Programs), policies (e.g., paid leave during quarantine), and within the work environment (e.g., adequate PPE or remote work). The following item was generated from these discussions: “Since you first became aware of COVID-19, how often did you feel you have received enough support from your work, (corporation, organization, or facility) during COVID-19?” Responses were measured on a Likert-type scale from 1 = Never to 5 = Always.

Intent to Stay

Intent to Stay with their current employer was measured using a single item “A year from now, do you think you will:” (1) Remain in your current position; (2) Remain at your current facility, but in a different nursing position; (3) Hold a nursing position at a different facility, under the same ownership as your current facility, (4) Hold a position with a different facility and ownership, but remain in your type of setting/unit; (5) Hold a position outside of your setting/unit, but remain in nursing; (6) Leave nursing, and (7) Not be employed. Intent to Stay with their current employer was considered a Yes response to response options 1, 2, or 3.

Data Management and Analysis

REDCap™ survey software was used to collect data and securely record and store study data during collection. Study data were downloaded and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27. Data were initially analyzed descriptively. A bivariate correlation matrix was created including Intent to Stay with Current Employer, Support from Work, Calm Environment, and Safe Environment. Variables with significant correlations identified in the matrix were included in the subsequent path analysis. A path analysis using 2-layered regression models was conducted to determine the pathways by which the Safe Environment, Calm Environment, and Support from Work variables interacted to influence nurses’ Intent to Stay with their current employer. Path model relationships were estimated controlling for the effects of demographic characteristics including age, education, provided direct care, worked in acute or ambulatory care, and LPN/RN. Overall model fit was determined using the R2 statistic. An alpha of p < .05 was set a priori.

Results

A total of 399 RNs were included in this analysis, for an overall response rate of 11.6%. The majority (92.7%) of participants identified as female; the average age was 38.6 ± 12.6 with most (59.9%) between the ages of 18 and 39 years. Most (95.2%) participants self-identified as White (95.2) and non-LatinX (96.8%). Participants were primarily Baccalaureate prepared (71.0%), provided direct patient care (65.1%), worked in an acute setting care setting (66.7%), and were an LPN or an RN (88.2%) (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Characteristics (N = 399)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age category | |

| 18-29 years | 116 (29.1) |

| 30-39 years | 123 (30.8) |

| 40-49 years | 74 (18.5) |

| 50-59 years | 46 (11.5) |

| ≥60 years | 40 (10.0) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 366 (92.7) |

| Male | 24 (6.1) |

| Other/prefer not to answer | 5 (1.3) |

| Race | |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (0.3) |

| Asian | 5 (1.3) |

| Black/African American | 5 (1.3) |

| White | 380 (95.2) |

| Other | 8 (2.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 12 (3.2) |

| Highest level of education | |

| None/student | 8 (2.0) |

| Licensed practical nurse (LPN) | 2 (0.5) |

| Diploma | 5 (1.3) |

| Associate degree | 23 (5.8) |

| Baccalaureate degree | 281 (71.0) |

| Master’s degree | 62 (15.7) |

| Doctorate | 15 (3.8) |

| Provide direct patient care | |

| No | 66 (16.7) |

| Yes, sometimes | 72 (18.2) |

| Yes | 257 (65.1) |

| Work setting during 2020 | |

| Acute care | 264 (66.7) |

| Ambulatory care | 132 (33.1) |

| LPN/registered nurse | |

| Yes | 352 (88.2) |

| No | 47 (11.8) |

Most participants indicated they intended to remain with their current employer (88.9%), and most (79.6%) felt supported by organizational leadership at least sometimes (79.5%) (Table 2 ). Regarding variables addressing a Calm Environment, less than half of the participants (27.1%) reported having a dedicated respite area away from the care area, 19.8% reported access to a low-noise space, and only 17.3% had views of nature in their workplace. Fewer than 10% reported having access to distraction resources such as visual art or music, and only one participant reported having access to natural light at work.

Table 2.

Frequencies of Intent to Stay with Current Employer, Support from Work, Calm and Safe Environment Variables (N = 399)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Intent to Stay with Current Employer | |

| Yes | 351 (88.9) |

| No | 44 (11.1) |

| Support from Work | |

| Never | 15 (3.8) |

| Rarely | 65 (16.6) |

| Sometimes | 131 (33.4) |

| Often | 133 (33.9) |

| Always | 48 (12.2) |

| Calm Environment | |

| Has a staff respite area away from treatment zone | 108 (27.1) |

| Has low noise | 79 (19.8) |

| Has views of nature | 69 (17.3) |

| Provide positive distractions such as arts and/or music | 39 (9.8) |

| Has natural light | 1 (0.3) |

| Safe Environment | |

| Has enough hand hygiene stations (easily visible and accessible) throughout the unit | 308 (77.2) |

| Has enough space to allow social distancing | 176 (44.1) |

| Has separate waiting and screening areas | 134 (33.6) |

| Has dedicated PPE donning and doffing area | 133 (33.3) |

| Has enough negative pressure rooms | 90 (22.6) |

| Has a one-way flow suite that allows doffing in a designated area separate from donning | 65 (16.3) |

Analysis of the Safe Environment variables revealed that most participants (77.2%) reported having access to adequate hand hygiene stations. Less than half of the participants indicated they had adequate space to allow adequate social distancing (44.1%), separate screening and waiting areas for COVID-19 patients (33.6%), dedicated PPE donning and doffing areas (33.3%), enough negative-pressure rooms (22. 6%), and one-way flow suites (16.3%).

Only Support from Work was significantly correlated with Intent to Stay with Current Employer (p < .01) (Table 3 ). The Calm Environment variables of Positive distractions such as arts and/or music (p < .01), Views of nature (p < .05), and Low noise (p < .01) were significantly correlated with Support from Work. The Safe Environment variables of Dedicated PPE donning/doffing area (p < .05), One-way flow suite (p < .01), and Enough space to allow social distancing (p < .01) were significantly correlated with Support from Work.

Table 3.

Spearman Correlation Coefficients for Intent to Stay with Current Employer, Support from Work, and Calm and Safe Environment Variables

| Variable/Factor | Intent to Stay | Support from Work |

|---|---|---|

| Intent to Stay with Current Employer | 1 | |

| Support from Work | 0.247∗∗ | 1 |

| Calm Environment | ||

| Has a staff respite area away from the treatment zone | 0.013 | 0.082 |

| Provide positive distractions such as arts and/or music | −0.018 | 0.162∗∗ |

| Has views of nature | 0.055 | 0.102∗ |

| Has low noise | 0.036 | 0.145∗∗ |

| Has natural lighta | 0.018 | −0.024 |

| Safe Environment | ||

| Has dedicated PPE donning and doffing area | 0.082 | 0.127∗ |

| Has a one-way flow suite | 0.070 | 0.158∗∗ |

| Has enough negative pressure rooms | 0.039 | 0.070 |

| Has enough hand hygiene stations | 0.004 | 0.088 |

| Has separate waiting and screening areas | 0.031 | 0.096 |

| Has enough space to allow social distancing | 0.069 | 0.192∗∗ |

Notes: ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, an = 1.

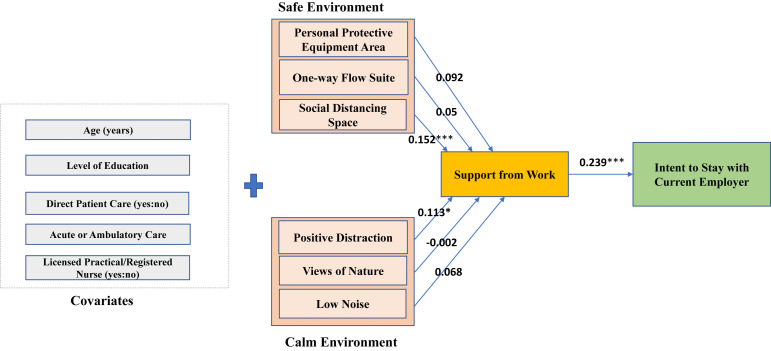

The path model with standardized parameter (β) estimates is depicted in Figure 1 . The full model fit the data adequately and explained 7.9% of variance in Intent to Stay with Current Employer. The model indicates that the effect of Safe Environment and Calm Environment variables on Intent to Stay with Current Employer is channeled through Support from Work. None of the Safe or Calm Environment variables had a direct effect on Intent to Stay. Social Distancing and having Positive Distractions were found to significantly influence Support from Work. The direct effect of Support from Work (p < 0.0001) on Intent to Stay with Current Employer appears to be the dominating path within the conceptualized model.

Figure 1.

Path Analysis Determining Pathways by which Safe Environment, Calm Environment, and Support from Work Influence Nurses’ Intent to Stay With Current Employer.

Notes: R2 = 0.079 (Adjusted R2 = 0.050), F(12,386) = 2.75, p < .01, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Discussion

In this paper, we explored relationships between Safe Environment and Calm Environment, Support from Work, and Intent to Stay among nurses during COVID-19. We also illustrated the role of Support from Work and organizational actions in a health care setting and their effect on nurses’ Intent to Stay with their current employer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Importance of Support at Work

Reports of inadequate Safe Environment and Calm Environment resources confirmed previous COVID-19 research.17 , 20 , 21 The care environment affects dimensions of well-being and productivity22 and can mitigate risk and increase staff safety.23 Yet most participants intended to remain with their employer, contrasting with other research linking COVID-19-related fears to turnover intention.19 , 24 Our results indicate that Support from Work had the strongest influence on Intent to Stay. In this study, Support from Work was developed by front-line staff nurses working in COVID-19 conditions and presented as a single, general item. Dimensions of Support from Work may vary by individual, entailing a variety of resources, socially supportive and leadership behaviors, and levels of organizational involvement. Given the dominating effect of Support from Work in the model to predict Intent to Stay, further exploration of its important facets is indicated.

Leadership Response Actions at TUKSH

A centralized Incident Command unit at TKUHS synchronized resource provision and employee support across the system. Safety measures included assembling dedicated groups of clinicians to review needs and supplies of PPE, deploying PPE spotters on regular rounding to assist with PPE needs, and implementing PPE training. Importantly, a shortage of PPE, which was a significant concern among health care globally,20 , 21 was not experienced at TUKHS during the time these data were collected. Employee support measures included COVID-19 support pay for exposed or ill employees, incentive pay for salaried employees to perform work in new resource areas such as COVID-19 swab testing, hotline for employee support, support for work reassignments for low volume situation, removal of the paid time off cap, remote work where appropriate, daily corporate communication emails/videos, and frequent town hall meetings for all employees. The physical capacity of the environment was addressed by creating additional negative-air-pressure rooms to expand capacity. Further, over a 48-hour period, an additional emergency department isolation care area was created to efficiently manage incoming potential COVID-19 patients.

Limitations

Results may have differed or supported other studies if data were collected at a different time during the pandemic. Conditions and organizational responses to working conditions and support for nurses and other staff members provided a context that may limit generalizability of these results to other institutions. Participating nurses worked in a variety of care settings, and not all provided care to COVID-19-positive patients, potentially influencing their responses. Finally, the relatively homogenous sample may limit the generalizability of results to more diverse populations.

Implications for Nurse Leaders

This study demonstrated that even in crisis conditions, nurses’ intent to stay or leave their employer is significantly linked to feeling supported at work. We have provided an account of some of the main actions taken by nursing leadership at the study site to respond to the unique needs precipitated by the pandemic and to provide support for nurses and other staff members. Work environments must be intentionally flexible, communication should be clear and consistent, and employee concerns should be actively sought and addressed. Above all, leadership in times of high stress and change is a test of endurance, so supportive strategies should be consistently implemented for the duration of the crisis.

Biography

Ericka Sanner-Stiehr, PhD, RN, is a Clinical Assistant Professor and Education Area Emphasis Coordinator at the University of Kansas School of Nursing in Kansas City, Kansas. She can be reached at esannerstiehr@kumc.edu. Amy Garcia, DNP, RN, is a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Kansas School of Nursing in Kansas City, Kansas. Barbara Polivka, PhD, RN, is a Professor and Associate Dean for Research at the University of Kansas School of Nursing in Kansas City, Kansas. Nancy Dunton, PhD, is a Research Professor at the University of Kansas School of Nursing in Kansas City, Kansas. Jennifer A. Williams, PhD, RN, ACNS-BC, is the Director of Nursing Practice, Research & Professional Development at the University of Kansas Hospital System in Kansas City, Kansas. Dammika Lakmal Walpitage, PhD, is a Senior Business Intelligence Analyst at the University of Kansas Department of Enterprise Analytics in Lawrence, Kansas. Cai Hui, PhD, is an Associate Professor and Chairperson at the University of Kansas School of Architecture and Design in Lawrence, Kansas. Kent Spreckelmeyer, D Arch, is a Professor at The University of Kansas School of Architecture and Design in Lawrence, Kansas. Frances Yang, PhD, is a Research Associate Professor at the University of Kansas School of Nursing in Kansas City, Kansas.

Footnotes

Note: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations of Interest: None.

References

- 1.American Association of Colleges of Nursing . American Association of the College of Nursing; Washington, DC: 2019. Fact Sheet: Nursing Shortage. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Association of Colleges of Nursing Fact Sheet: Nursing Shortage. American Association of the College of Nursing. 2019. https://www.aacnnursing.org/News-Information/Fact-Sheets/Nursing-Shortage Available at:

- 3.Duffield C.M., Roche M.A., Homer C., Buchan J., Dimitrelis S. A comparative review of nurse turnover rates and costs across countries. J Adv Nurs John Wiley Sons Inc. 2014;70(12):2703–2712. doi: 10.1111/jan.12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cho S., Lee J., You S.J., Song K.J., Hong K.J. Nurse staffing, nurses prioritization, missed care, quality of nursing care, and nurse outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2020;26(1) doi: 10.1111/ijn.12803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc . 2021. 2021 NSI National Health Care Retention & RN Staffing Report.https://www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Documents/Library/NSI_National_Health_Care_Retention_Report.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marufu T.C., Collins A., Vargas L., Gillespie L., Almghairbi D. Factors influencing retention among hospital nurses: systematic review. Br J Nurs. 2021;30(5):302–308. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2021.30.5.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKenna J., Jeske D. Ethical leadership and decision authority effects on nurses’ engagement, exhaustion, and turnover intention. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(1):198–206. doi: 10.1111/jan.14591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean Martin A. Embracing Advanced practice Providers: creating a Culture of retention through Structural Empowerment. Nurse Lead. 2020;18(3):281–285. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Africa L., Trepanier S. The role of the nurse leader in Reversing the new Graduate nurse intent to leave. Nurse Lead. 2021;19(3):239–245. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson-Brantley H.V., Ford D.J. Leading change: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(4):834–846. doi: 10.1111/jan.13223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatzittofis A., Constantinidou A., Artemiadis A., Michailidou K., Karanikola M.N.K. The role of perceived organizational support in mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:707293. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.707293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu D., Zhang N., Bu X., He J. The effect of perceived organizational support on the work engagement of Chinese nurses during the covid-19: the mediating role of psychological safety. Psychol Health Med. 2021 doi: 10.1080/13548506.2021.1946107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Digby R., Winton-Brown T., Finlayson F., Dobson H., Bucknall T. Hospital staff well-being during the first wave of COVID-19: staff perspectives. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(2):440–450. doi: 10.1111/inm.12804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gázquez Linares J.J., Molero Jurado M. del M., Martos Martínez Á., Jiménez-Rodríguez D., Pérez-Fuentes M. del C. The repercussions of perceived threat from COVID-19 on the mental health of actively employed nurses. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(3):724–732. doi: 10.1111/inm.12841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen J., Rodgers Y. van der M. Contributing factors to personal protective equipment shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med. 2020;141:106263. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saadeh D., Sacre H., Hallit S., Farah R., Salameh P. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among nurses in Lebanon. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2021;57(3):1212–1221. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iheduru-Anderson K. Reflections on the lived experience of working with limited personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 crisis. Nurs Inq. 2021;28(1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/nin.12382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shanafelt T., Ripp J., Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133–2134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labrague L.J., Santos J.A.A. Fear of COVID-19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. J Nurs Manag John Wiley Sons Inc. 2021;29(3):395–403. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catania G., Zanini M., Hayter M., Timmins F., Dasso N., Ottonello G., et al. Lessons from Italian front-line nurses’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative descriptive study. J Nurs Manag John Wiley Sons Inc. 2021;29(3):404–411. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ming X., Ray C., Bandari M. Beyond the PPE shortage: Improperly fitting personal protective equipment and COVID-19 transmission among health care professionals. Hosp Pract 1995. 2020;48(5):246–247. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2020.1802172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry L.L., Parish J.T. The impact of facility improvements on hospital nurses. Health Environ Res Des J. 2008;1(2):5–13. doi: 10.1177/193758670800100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verdoorn B.P., Bartley M.M., Baumbach L.J., Chandra A., McKenzie K.M., Mendoza De la Garza M., et al. Design and implementation of a skilled nursing facility COVID-19 unit. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(5):971–973. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Said R.M., El-Shafei D.A. Occupational stress, job satisfaction, and intent to leave: nurses working on front lines during COVID-19 pandemic in Zagazig City, Egypt. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(7):8791–8801. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]