Abstract

Recent studies have documented life satisfaction of people have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is unknown about the influential factors and mechanisms of life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a strong link among life satisfaction and individual quality of life and achievement, so it is important to explore the influence mechanism of life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students and explore ways to improve life satisfaction for the development of postgraduate medical students. The current study was based on the Circumplex Model of Marital and Family System, The Theory of Family Functioning, The Meaning Maintenance Model, The Theory of Personal Meaning and Existential Theory to construct theoretical framework and examine whether meaning in life and depression would mediate the link between family function and postgraduate medical students’ life satisfaction. By convenient sampling method, a total of 900 postgraduate medical students (Mage = 27.01 years, SD = 3.33) completed questionnaires including Family APGAR Scale, Chinese Version of Meaning In Life Questionnaire, Patient Health Questionnaire, and Satisfaction With Life Scale. In this study, SPSS 25.0 was used for correlation analysis, regression analysis and common method bias test, and AMOS 23.0 was used for structural equation modeling analysis. The results showed that (a) family function could predict life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students significantly; (b) both meaning in life and depression mediated the association between family function and life satisfaction in a parallel manner; (c) meaning in life and depression sequentially mediated the link between family function and life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students. The study illuminates the role of meaning in life and depression in improving life satisfaction and implies that it is necessary to focus on the changes of life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic, and medical educator can improve the sense of meaning in life of postgraduate medical students through improving their family function, further decreasing the risk of depression, finally improving their life satisfaction.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Medical students, Life satisfaction, Family function, Meaning in life, Depression

COVID-19 pandemic; Medical students; Life satisfaction; Family function; Meaning in Life; Depression.

1. Introduction

Due to the influence of multiple factors, such as individual, family and school, the psychological pressure of graduate students in colleges and universities is higher than that of the general population on the whole, and their mental health status is also worse (Guo et al., 2021). For students, experience of high academic stress was associated with low life satisfaction (Moksnes et al., 2019)coupled with the fact that medical education itself is a highly stressful process (Iftikhar et al., 2019), which can reduce medical students’ life satisfaction (Wang et al., 2019). While there is a global concern about the effects of COVID-19 on physical health now, the effects of the coronavirus on psychological health should not be underestimated (Satici et al., 2020; Karakose et al., 2021). It is true that during the COVID-19 pandemic, everyone in society had to face the double pressure of interpersonal isolation and infection (Duong, 2021) and was forced to live with dangerous infectious viruses (Karakose et al., 2021). Due to the increasing risk of the COVID-19 infection, strict isolation measures, mandatory home isolation and other events, more and more studies are beginning to focus on the mental health status of different populations during this period (Loan et al., 2021). Especially, postgraduate medical students are the future big part of people fighting the pandemic against the COVID-19, which means they have more mental and psychological distress (Safa et al., 2021). There have been several studies that have attempted to link the decline in life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic to a number of factors, but these studies either did not address the medical student population (Karakose et al., 2021) or did not explore the specific causes of the decline in life satisfaction of medical students (Bolatov et al., 2021; Nikolis et al., 2021), which means that it would be difficult to develop psychological intervention programs to improve the mental health status of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic based on the phenomenon of declining life satisfaction among medical students. For example, medical students need to study at home and need to balance online course study tasks as well as research tasks, and may face double pressure from academics and family. When medical students encounter psychological problems and reduced life satisfaction, they can seek help from medical educators through the online platform, but the emergence of psychological problems and reduced life satisfaction of medical students is different from the past, and at this time increases the impact of home isolation and close contact with family, medical educators may be at a loss for words in these situations because they do not know why the life satisfaction of medical graduate students is affected, much less what advice can be given to better help medical graduate students solve their immediate problems. Therefore, on the other hand, this study focuses on what factors may have an impact on medical students’ life satisfaction during COVID-19 pandemic, and on the other hand, this study hopes to explore the specific mechanisms by which this impact arises and expects to develop relevant recommendations applicable to medical students during COVID-19 pandemic based on specific mechanisms.

The investigators hope that the results of this study will enrich the discussion about medical students' life satisfaction, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, as discussions addressing this issue will certainly affect the future of the medical and health industry. Hence, the main research question of this study is: What is the relationship between medical students’ family function and their satisfaction with life? What are the factors that may influence the relationship between medical students’ family function and their satisfaction with life? Therefore, the next paragraphs present the findings and research progress on family function, life satisfaction, and other relevant factors of medical students, and lays the theoretical foundation for the proposed research hypothesis.

1.1. Family function and life satisfaction

Family function includes the structure of family relations, the quality of communication between family members and the internal communication of the family (Fang et al., 2004). Many studies also have found that family seems to be a key variable that contributes to life satisfaction (Frasquilho et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2019). Circumplex Model of Marital and Family System constructs a trustworthy theoretical and empirical framework for a better view of the relationship between parental affection and personal well-being (Olson et al., 2000). This notion has been confirmed by some recent studies. For example, some research results have supported that the high level of life satisfaction was greatly linked to family function (Wenzel et al., 2020). To be more precise, Manzi and colleagues observed if young people’ s family relationships are cohesive, their life satisfaction is likely to be relatively high (Manzi et al., 2010). During the COVID-19 pandemic, home quarantine and medical observation increased the time spent with family members, so the effort from family function on individual satisfaction with life was also more obvious during the period. If there is at low level of family interaction (disengagement) or a failure to provoke a higher level of empathy between members, that would cause isolation of relationship and decrease life satisfaction of family members. However, the researchers suggest that the interaction among medical students’ family function and their satisfaction with life may have subtly changed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, and that family function may be a better predictor of life satisfaction, or the effect of family function on life satisfaction may be weakened by the involvement of other factors. Only a few previous literature has addressed the link between family function and life satisfaction in the group of postgraduate medical students during the special period of the COVID-19 pandemic, therefore, the present study can provide a better complement to the previous findings. So our study would like to explore if family function can positively predict life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.2. The mediating role of meaning in life

Meaning in life plays an important role in human physical as well as mental health and well-being (O'Donnell et al., 2014). The existing researches have confirmed that family function could impact meaning in life. The Meaning Maintenance Model suggests that the relationship structure that individuals have plays a critical role in their acquisition of meaning (Heine et al., 2006). Individuals tend to find a sense of belonging in intimate relationships, which leads to a sense of meaning in life (Baumeister, 2005), and family relationship structure is an important source of meaning acquisition for college students (Zeng et al., 2018). Goodman et al. (2019) assumed that family dynamics may be an important source of increasing belonging for both women and men, and belonging is predictive of meaning in life. Some surveys also have concluded that family relationships have an important role in influencing the meaning of life and families contributing to promote their sense of meaning for young adults (Lambert et al., 2010). Meanwhile, life satisfaction is strongly related to meaning in life. The Theory of Personal Meaning is that meaning in life is composed of order, coherence and purpose, achieving goals can produce a sense of accomplishment (Reker and Wong, 1988). That process can increase people’s life satisfaction. Previous literature results also suggest a strong link among meaning in life and individual satisfaction with life, meaning in life positively affected life satisfaction of college students (Datu and Mateo, 2015). And previous research also has used meaning in life as a mediator, the result demonstrated that meaning in life could mediate the association among positive cognition and their satisfaction with life (Lightsey and Boyraz, 2011). And yet most of these studies were conducted on general college students, and it is known that medical students are a special group of students, so it is not known whether the findings of previous studies can be applied to the medical student population, plus the psychological status of medical students changed to a greater or lesser extent during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is necessary to develop new findings based on previous studies for medical students in the special period. Based on the results of previous studies, we hypothesized that meaning in life might be a mediator between family function and postgraduate medical students’ satisfaction with life.

1.3. The mediating role of depression

The Theory of Family Functioning suggests that the realization of the basic family function provides certain environmental basis for the healthy development of the physical, psychological and social aspects of family members (Fang et al., 2004). Epstein also believed that if the family failed to realize its basic function in the process of operation, it would easily lead to a variety of mental health problems among family members (Miller et al., 2010). On the one hand, a wealth of theoretical and empirical literature existed linking poor family function with depression (Febres et al., 2011). A previous research has examined medical students’ family function and found that the medical students with major depressive disorder had worse family function (Shao et al., 2020). Adolescent depression was also associated with impairment in family function (Sireli and Aysev Soykan, 2016). On the other hand, people’s depression was negatively associated with their own level of satisfaction with life (Bukhari and Saba, 2017; Schnettler et al., 2019). Furthermore, in a previous whole study of women living with breast cancer, depression was found to be an important mediator variable in the effect from social support to quality of life (Kugbey et al., 2020) while a study also investigated the indirect effect of facebook addiction on life satisfaction through social anxiety and depression (Foroughi et al., 2019). These studies all suggested that depression as a mediator can mediate the relationship between the external environment and the individual subjective experience of life during COVID-19 pandemic (Mahmud et al., 2021). While these studies certainly have provided a solid theoretical foundation for this study, they also had limitations: most of these studies were limited by sample size, sampling method, or the period of the survey, and therefore, the researchers want to further test the reliability of these findings. In conclusion, depression might mediate the association among family function and postgraduate medical students’ satisfaction with life.

1.4. The mediating role of meaning in life and depression

Existential Theory emphasizes the relationship between meaning in life and depression, Frankl also assumed that the individual search for a sense of meaning is a human instinct and a source of motivation (Frankl, 2005). When individuals believe that life has meaning and that they can find it, they are able to experience a sense of control over their lives, however, when they continue to feel that life is meaningless and full of emptiness, they experience a sense of powerlessness that life is out of control and have no motivation or confidence to do anything, increasing the likelihood that the individual will fall into depression. A longitudinal study of 797 adults in 43 countries investigating factors influencing depression showed that a high level of meaningful living predicted a reduction in depression over a period of three to six months and that meaningful living interventions were effective in reducing depression in adults (Disabato et al., 2017). On the one hand, in the student population, students who perceive higher meaning in life experience less depression (Datu et al., 2018) while significant correlation between meaning of life and depression of undergraduates has also been demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic (Parra, 2020). This implies that the meaning of life may have an impact on depression in postgraduate medical students. On the other hand, in a previous study of college students, family function was shown to significantly influence the meaning of life for college students (Zhang et al., 2021). Thus, the relationship between family function and depression of postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic may be mediated by meaning in life.

Most previous studies have focused on the discussion of the relationship between one or two of these four variables, and these studies did find some relationships that existed, but if one needs to uncover the specific mechanisms by which family function affects medical students’ life satisfaction, one must include family function, meaning in life, depression, and life satisfaction in the same hypothetical model and test the order and pattern in which such changes occur. In summary, maybe there is a chain mediating effect between family function, meaning in life, depression, and life satisfaction among postgraduate medical students.

1.5. Present study

In short, this study sought to test the mediators of meaning in life and depression between family function and life satisfaction among postgraduate medical students, in order to consolidate and broaden our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the links between family function and their satisfaction with life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

If the hypotheses hold, it would directly improve the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students by enhancing their family function, it can also improve the family function to enhance their meaning in life and reduce their depression, further reaching the goal of enhancing life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students indirectly. As an important force in the development of medical career, the mental health of postgraduate medical students is related to the future direction of medical and health care, exploring the factors influencing the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic is not only of immediate importance to provide methods to enhance the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students, but also of long-term significance to provide interventions to enhance the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students when public health emergencies may occur in the future. Based on the above discussions, we raised the following four hypotheses:

H1

Family function will positively predict life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students.

H2

Family function will affect life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students through meaning in life.

H3

Family function will affect life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students through depression.

H4

Family function will affect life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students through the serial mediation of meaning in life and depression.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The study was approved by Medical Research Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (Approval No. 2020, 037), the study complies with all regulations. Our study was conducted according to established ethical guidelines, and informed consent obtained from the participants and hospital administrators. Before commencing the survey, we used Monte Carlo methods to calculate the sample size of the study (Thoemmes et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2021). The findings revealed that the statistical testing power of each of the paths of the model was over 0.90 after the sample size reached 850. Thus, the researchers concluded that the sample size of the present study should be more than 850. In this study, postgraduate medical students were selected at a university hospital through convenience sampling method. According to the questionnaire setting of this study, participants had to complete all the items in the questionnaire before they could complete the submission. Therefore, all the questionnaire data obtained for this study are complete. After obtaining all the data, we checked the data and found the data didn’t distribute normally (P < 0.05), with reference to previous studies, we ensured the integrity of all data and therefore we believe that the data with non-normal distribution will not affect the findings of this study when testing the proposed structural equation model using Bootstrap Method in AMOS 23.0 (Liu and Ouyang, 2021). A total of 900 postgraduate medical students finished the all questionnaires and scales, and 447 (49.67%) of the postgraduate medical students were females. The mean age of the postgraduate medical students was 27.01 (SD age = 3.33, range = 22–57).

2.2. Measurement tools

2.2.1. Measurement of family function

Family function was measured by using Family APGAR Scale (APGAR, Feng et al., 2021). The scale is composed of five items that assess different dimensions. The scale adopts a three scoring method (0 = occasionally, 1 = rarely, 2 = frequently). In the present study, the Cronbach alpha for the total scale was 0.89, respectively. CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) has showed that AVE (Average Variance Extracted) was 0.63, CR (Composite Reliability) was 0.90, which indicated good convergent validity of the Family APGAR Scale.

2.2.2. Measurement of meaning in life

Meaning in life was measured by using 10 item Chinese Version of Meaning in Life Questionnaire (C-MLQ) which was developed by Liu and Gan (2010). The questionnaire includes 2 dimensions: the presence of meaning in life and search for meaning in life. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.74 and 0.89 for the MLQ-P and MLQ-S, respectively. CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) has showed that AVE (Average Variance Extracted) of the presence of meaning in life was 0.72, CR (Composite Reliability) was 0.91, while AVE (Average Variance Extracted) of the search of meaning in life was 0.63, CR (Composite Reliability) was 0.90, which indicated good convergent validity of the Chinese Version of Meaning in Life Questionnaire.

2.2.3. Measurement of depression

Depression was measured by using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, Spitzer et al., 1999). The questionnaire consisted of 9 items. The Cronbach alpha in this study for this assessment was 0.87. CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) has showed that AVE (Average Variance Extracted) was 0.51, CR (Composite Reliability) was 0.90, which indicated good convergent validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire.

2.2.4. Measurement of life satisfaction

Life satisfaction was measured by using the 5-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS, Diener et al., 1985). The Scale consisted of 5 items. The Cronbach alpha in this study for this assessment was 0.91. CFA (Confirmatory Factor Analysis) has showed that AVE (Average Variance Extracted) was 0.67, CR (Composite Reliability) was 0.91, which indicated good convergent validity of the 5-item Satisfaction With Life Scale.

3. Results

3.1. Common method bias

The Harman’s single factor test (Huang et al., 2021) revealed that there were 5 common factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, of which the initial eigenvalue of the first factor was 9.64, which explained 33.25% of the variance, and which was also less than the critical value of 40%, indicating that common method bias was not significant.

3.2. Correlation between variables

Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated that there was a positive correlation among family function and meaning in life and life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students (Table 1). However, there was a negative correlation between family function and depression. In addition, meaning in life was negatively correlated with depression. And meaning in life was positively related to life satisfaction. Finally, depression was negatively related to life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students.

Table 1.

Correlations between variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family function | — | |||

| Meaning in life | 0.32∗∗∗ | — | ||

| Depression | −0.39∗∗∗ | −0.21∗∗∗ | — | |

| Life satisfaction | 0.50∗∗∗ | 0.38∗∗∗ | −0.46∗∗∗ | — |

| M | 6.95 | 50.49 | 2.59 | 21.91 |

| SD | 2.62 | 9.35 | 3.60 | 5.85 |

Note. ∗P< 0.05, ∗∗P< 0.01, ∗∗∗P< 0.001.

3.3. Regression analysis

After the strict control of postgraduate medical students’ gender and age (Table 2), family function could positively predict meaning in life (β = 0.32, t = 10.16, P < 0.001) and was also a negative predictor of depression (β = -0.36, t = -11.25, P < 0.001). In addition, meaning in life was a negative predictor of depression (β = -0.09, t = -2.68, P < 0.05). Moreover, family function, meaning in life and depression significantly predicted life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students (β = 0.31, t = 10.49, P < 0.001; β = 0.22, t = 7.86, P < 0.001; β = -0.29, t = -10.09, P < 0.001). Therefore, family function could predict life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students during the COIVD-19 pandemic, hypothesis 1 was supported.

Table 2.

Regression analysis.

| Meaning in life |

Depression |

life satisfaction |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | β | SE | t | β | SE | t | |

| Gender | −0.07 | 0.03 | −2.15 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.16 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.67 |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.50 | −0.003 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.64 |

| Family function | 0.32 | 0.03 | 10.16 | -0.36 | 0.03 | −11.25 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 10.49 |

| Meaning in life | -0.09 | 0.03 | −2.68 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 7.86 | |||

| Depression | −0.29 | 0.03 | −10.09 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.37 | ||||||

| F | 36.05∗∗ | 43.15∗∗∗ | 107.58∗∗∗ | ||||||

∗P< 0.05, ∗∗P< 0.01, ∗∗∗P< 0.001.

3.4. Path analysis depicting direct effects

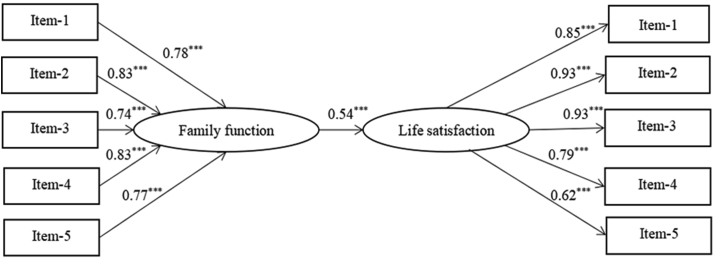

To further test the mechanism of the medication role of depression and meaning in life between family function and life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students, we used AMOS 23.0 to conduct a path analysis. We first verified the direct path. The indicators of model 1 were well fitted, χ2 = 219.19, χ2/DF = 6.45, CFI = 0.97, NFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.04. The findings of path analysis (Figure 1) revealed that family function could be a predictor of postgraduate medical students’ life satisfaction (β = 0.54, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Path analysis depicting direct effects of family function on life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students. Note. all variables were standardized prior to the analysis to avoid the multicollinearity.

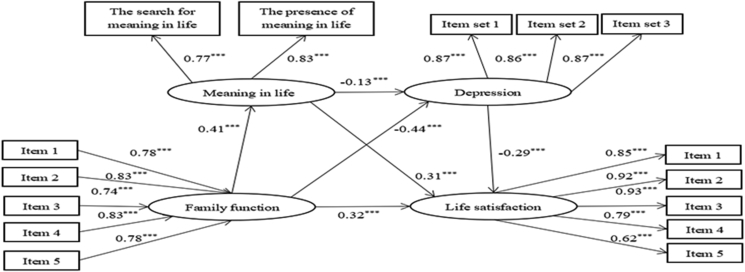

The serial mediation model (Figure 2) showed an excellent fit of the data, χ2 = 344.60, χ2/DF = 4.05, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.04, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0. 97, TLI = 0.97. The results of path analysis (Figure 2) demonstrated that family function could predict meaning in life and life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students positively (β = 0.41, P < 0.001, β = 0.32, P < 0.001, respectively), and family function could be a significant predictor of depression (β = -0.44, P < 0.001). Meaning in life markedly reduced depression (β = -0.14, P < 0.001), and had a significant effect on postgraduate medical students’ life satisfaction (β = 0.31, P < 0.001). Moreover, depression was related to life satisfaction negatively (β = -0.29, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Serial mediation model.

The bootstrapping procedures showed that both meaning in life and depression could mediate the relationships between family function and life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students (Table 3): (1) meaning in life mediated the association between family function and life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students (indirect effect = 0.13; 95%CI: 0.08, 0.18, P < 0.001); (2) depression mediated the link between family function on life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students (indirect effect = 0.13; 95%CI: 0.09, 0.18, P < 0.001); (3) meaning in life and depression played a serial mediating role in the relationship between family function and life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students (indirect effect = 0.02; 95%CI: 0.01, 0.03, P < 0.05). To sum up, hypothesis 2, 3 and 4 were supported.

Table 3.

The effect sizes with meaning in life and depression as mediators.

| Effect | Point Estimate (95% Confidence Interval) | Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FF→LS | 0.317(0.237, 0.409) | 54.00% | |||

| FF→ML→LS | 0.127(0.081, 0.180) | 21.63% | |||

| FF→DEP→LS | 0.127 (0.087, 0.178) | 21.63% | |||

| FF→ML→DEP→LS | 0.015 (0.005, 0.030) | 2.73% | |||

| Total | 0.586 (0.512, 0.669) | ||||

Note. FF=family function; ML=meaning in life; DEP=depression; LS=life satisfaction.

4. Discussion

Extensive researches have explored some reasons and factors which influenced life satisfaction (Chai et al., 2020; Rogowska et al., 2020; Kekkonen et al., 2020). However, only minority studies have examined the influence factors for life satisfaction of medical students in normal times (Shi et al., 2018; Salmani et al., 2019). The existing research also have showed the COVID-19 pandemic affected life satisfaction of people (Li et al., 2020; Khalafallah et al., 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, postgraduate medical students are not only faced with the dilemma that their scientific research and learning is negatively affected in this special period, but also need to cope with the impact of the COVID-19 on their daily life. The life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students may be damaged and cannot maintain a high level of state. But the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students is unknown, which means that if there is a need to improve medical students' life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is not yet known which relevant factors are feasible for us to intervene. To increase our understanding on the influential mechanisms of life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic and also for us to develop a more specific and clear psychological intervention program for medical students, the current study explored the mediating roles of meaning in life and depression from the impact of family function on life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students. Our findings are favorable to enhance the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students in two aspects: specifically, firstly, the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students can be directly enhanced by enhancing family function. Secondly, it can indirectly improve the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students by enhancing family function to influence their meaning in life and depression.

4.1. Family function and life satisfaction

Before undertaking structural equation modelling, many researchers have tested the correlations of the variables in the study to initially establish that the hypotheses are viable. This study referred to this testing process and as shown in Table 1, correlations exist between all four variables explored in this study. The study explored how family function affected life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. In hypothesis 1, we argued that family function predict the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students. Two methods were used to test hypothesis 1. One method used regression analysis to test whether family function predicted life satisfaction among medical postgraduate students, and the other method introduced family function and life satisfaction into a structural equation model to test whether the direct path was significant. The results of the study showed that this hypothesis was supported. On the one hand, family function could predict life satisfaction (β = 0.31, t = 10.49, P < 0.001; Table 2). On the other hand, the modeling fitting of the proposed model 1 (Figure 1) was in good condition (CFI, NFI, TLI > 0.90; RMSEA, SMRA < 0.08) and the path coefficients of family function predicting life satisfaction met the requirement for significance (β = 0.54, P < 0.001). Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the results showed that family function was positively correlated with life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students. This result was consistent with previous studies, individuals who rated their family function as positive and supportive are more likely to process their own emotions and enjoy higher life satisfaction (Szczeniak and Tuecka, 2020). The results of our study suggested that this finding also applied to postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many schools adopt online teaching to maintain the teaching process, postgraduate medical students have to complete their research and daily work at home and spend more time with their families, good family function not only means good communication and interaction between family members, which can lead to more positive emotions experienced by postgraduate medical students, but also means less family conflict and contradiction, which can help them handle stress effectively and give them more energy to deal with various things, ultimately maintaining the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students in a good state.

4.2. The mediating role of meaning in life

The study explored whether meaning in life mediated between family function and life satisfaction among postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. We tested hypothesis 2 using a serial mediation model. In the serial mediation model, we introduced four different variables, which were family function, meaning in life, depression and life satisfaction. As in testing proposed model 1 we first tested the modelling fitting index and the results showed that the serial mediation model fitted well (CFI, NFI, TLI > 0.90; RMSEA, SMRA < 0.08). Family function predicted meaning in life (β = 0.41, P < 0.001; Figure 1) while meaning in life could also predict life satisfaction (β = 0.31, P < 0.001). Consistent with Hypothesis 2, which meant that postgraduate medical students with high level of family function tended to find meaning in life, which in turn were more likely to be satisfied with life (indirect effect = 0.13, P < 0.001; Table 3). the one hand, as hypothesized, family function is positively associated with meaning in life. When medical staffs have negative emotions that affect their goals and experiences of life, the support of family is a good way for them to reduce stress and ease anxiety (Racine, Plamondon, Hentges, Tough and Madigan, 2020). After that, positive emotional experience and successful coping experience could motivate individuals to achieve goals and solve problems more effectively (Feldman and Snyder, 2005). This finding is also consistent with the theory of family intimacy (Li et al., 2014), which denotes that people had the sense of belonging from relatives, friends, and family could especially give themselves a great sense of meaning in life (Lambert et al., 2010). On the other hand, our findings indicate that postgraduate medical students’ meaning in life was a significant predictor of their satisfaction with life. Individuals with a higher sense of meaning have a lower risk of experiencing depression and anxiety (Sternthal et al., 2010), individuals with a higher sense of meaning also tend to be healthier, happier, less troubled, and live longer (Hill and Turiano, 2014), all of which contribute to increase medical students’ satisfaction with life (Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, meaning in life played a partially mediating role in the link among postgraduate medical students’ family function and their satisfaction with life.

4.3. The mediating role of depression

The study examined whether depression play a mediator among medical students’ family function and their satisfaction with life. The relationship between these three variables was also tested in the serial mediation model. Family function was a negative predictor of depression (β = 0.41, P < 0.001; Figure 1) and depression could also predict life satisfaction negatively (β = 0.31, P < 0.001). Consistent with Hypothesis 3, which suggested that depression mediated the association between family function and life satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.13, P < 0.001; Table 3). This finding reveals that postgraduate medical students with healthy family function tended to have less depressive symptoms, which were more likely to be pleased with their life. First, family function was significantly positively associated with depression. This result is in line with previous research that medical students with poor family function could hardly get support from family during a crisis and were more likely to have mood swings which could lead to feelings of depression (Nasir et al., 2011). Therefore, for postgraduate medical students with healthy family function, they may discuss more with family members when feeling uncomfortable during the COVID-19 pandemic, becoming consequently more capable of dealing with problems by themselves. Our result is also consistent with previous empirical studies that have shown that other psychological variables associated with depression such as aloneness, helplessness and anxiety were negatively associated with family function (Yang et al., 2020). Second, depression was related to life satisfaction, it meant depression is often a factor in making current life satisfaction reduction. This finding is congruent with the prior study (Swami et al., 2007), which indicates that medical students who had a higher opinion of themselves, fewer symptoms of depression, will also have higher life satisfaction. Our results also are consistent with prior cross-sectional studies, which have shown that the depression of both adults and children is related to low life satisfaction (Wei et al., 2015; Wang and Peng, 2017). Therefore, depression played a partial mediator in the link among postgraduate medical students’ family function and their satisfaction with life.

4.4. The mediating role of meaning in life and depression

At the end of the study, we examined whether meaning in life and depression play a serial mediating role between family function and life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students. The final sequential mediator role tested in the serial mediation model was that of meaning in life and depression. The serial mediation model was designed to test the relationship between the two mediation models, so whether meaning in life could predict depression was key to the validity of the serial mediation model, and the results showed that meaning in life could predict depression (β = -0.14, P < 0.001). Consistent with Hypothesis 4, which implied that meaning in life and depression could medicate the association between family function and postgraduate medical students’ life satisfaction both in parallel and sequential manners (indirect effect = 0.02, P < 0.05; Table 3). To be specific, postgraduate medical students with poor family function tended to have less sense of meaning in life and were more likely to have depressive symptoms, such as low spirits and insomnia which in turn reduced their life satisfaction. For one thing, postgraduate medical students with healthy family function not only tend to have the sense of meaning in life (Glaw et al., 2020), but also less likely to be depressed (Ozkaya et al., 2010), which in turn were less likely to be unsatisfied with their life (Ni et al., 2020). For another thing, postgraduate medical students’ meaning in life and depression sequentially mediated the relationship among family function and their satisfaction with life. Our findings indicate that postgraduate medical students with good family function incline to have a greater sense of meaning in life meaning in life (Li et al., 2020), which in turn promotes mental health (Shiah et al., 2015) and reduces the risk of having mental diseases, consequently increase life satisfaction (Fergusson et al., 2015). In sum, these findings support that the positive effect of family function for life satisfaction, which can increase the sense of meaning in life and decrease the probability of being depressed, thus improve the satisfaction with life.

4.5. Implication

The study has great theoretical and practical significance for understanding the psychological mechanisms underlying the family function --- life satisfaction associations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Theoretically, during the COVID-19 pandemic, our study adds new evidence and extends other factors to life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students for the family function theory. The results reaffirm the notion that family function can play a unique role in influencing the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students. Practically, the present study also helps to identify the vulnerable medical students, providing some help for their online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Online learning was common during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for medical students, where the risk of the virus spreading on campus forced universities to reduce the number of face-to-face classes and, therefore, the intensive medical curriculum forced universities to use online learning to ensure that medical students could complete their scheduled study programmes (Mustika et al., 2021). However, previous research has indicated that medical students’ motivation during online learning is affected by a lack of social support from the institution, which further affects their learning outcomes (Kaup et al., 2020; Longhurst et al., 2020). And a reduction in face-to-face training could also have led to a decrease in motivation and life satisfaction of medical students (Bolatov et al., 2021). As a result, students might be at greater risk of anxiety, loneliness and feelings of isolation as online learning continues (Lyons et al., 2020), further affect their life satisfaction negatively (Vate-U-Lan, 2020). According to self-determination theory, motivation to learn could be influenced by a combination of internal and external factors (Orsini et al., 2016). Family function as important external factors, meaning in life, depression and life satisfaction as individual internal factors might have influenced the academic motivation of medical students while studying online during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the potential for online learning to extend for another year or even years, medical educators must quickly find a way to deal with the negative emotions experienced by medical students (Mustika et al., 2021). On the one hand, with the family as an important social support system, good family function may have a positive impact on medical students’ motivation to learn online and may somewhat offset the negative effects of their lack of social support from institutions. On the other hand, Life satisfaction has always been a strong predictor of academic motivation (Karaman and Watson, 2017). Their satisfaction with life was influenced by medical students’ family function during the COVID-19 pandemic, and we therefore suggest that medical students' life satisfaction could be improved either directly or indirectly by improving their family functions, and that this increase in life satisfaction, ultimately increasing their motivation to learn online during the COVID-19 pandemic. We therefore consider: firstly, there is a positive impact from family function on the life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students, and the school can carry out relevant elective courses or group support activities to help postgraduate medical students acquire quality communication skills and good interaction with their families, so as to optimize the family function of postgraduate medical students and thus improve their life satisfaction. Secondly, meaning in life and depression could medicate the link among postgraduate medical students’ family function and their satisfaction with life both in parallel and sequential manners, this means that schools and internship units can also help postgraduate medical students to find and improve the meaning in life and reasonably regulate negative emotions to improve their satisfaction with life by offering physical and mental health courses and providing psychological online counseling services (Karakose et al., 2021). In addition, online learning plays an important role in maintaining postgraduate education during the COVID-19 pandemic. When designing online courses, medical educators should not only consider the planning of professional courses, but should also include content related to mental health education such as communication skills in their online courses to help them improve their family function. The above-mentioned courses can be uploaded through school videos for students to browse independently, and online psychological consultation can also be carried out to serve students.

4.6. Limitations and future directions

This study still has some limitations that require special attention in interpreting the findings of this study, and based on these limitations, there are still many aspects of this study that can be enhanced. First of all, the data for all postgraduate medical students were collected from the online survey. Therefore, the various types of errors that may be introduced by online surveys require additional attention. In future studies, we consider combining online surveys with face-to-face interviews to get a more comprehensive picture of medical students’ relevant information. Second, postgraduate medical students in the current study were from the same university affiliated hospital, which may not be representative of postgraduate medical students in other areas of China. Therefore, we hope that medical students from other regions and other institutions can be included in the study to improve the representativeness of the sample. Additionally, we collected data from one hospital, a cross-section of the general population, we cannot confidently infer causation from the relationships between our variables. If possible, a future experiment or longitudinal study would be a better option.

5. Conclusions

The present study contributes to literature by examining the relationship between family function and life satisfaction among postgraduate medical students, and the mechanisms of influence therein. Our findings enrich our insights on how family function improves life satisfaction of postgraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Few previous studies on medical students’ life satisfaction have been conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, and even when studies have investigated medical students’ life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic (Nikolis et al., 2021; Yun et al., 2021), however, they have not explored the underlying mechanisms of this phenomenon, nor have they suggested what factors could be interfered with to improve medical students’ life satisfaction during the period. Therefore, the present study fills the research gap and we constructed a sequential mediation model, in addition to two mediation models and a direct pathway. Thus, based on our findings we propose four ways to intervene in the life satisfaction of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. They are directly enhancing medical students’ life satisfaction by improving family function, indirectly enhancing medical students’ life satisfaction by affecting meaning of life or depression through family function respectively, and the last one is based on a sequential mediation model by enhancing medical students’ family function, enhancing medical students’ meaning in life, further reducing depression, and finally enhancing medical students’ life satisfaction.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Zewen Huang; Junyu Wang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Lejun Zhang; Tingting Wang; Conceived and designed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Lu Xu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Yan Tang; Yin Li; Ming Guo; Yipin Xiong; Wenying Wang; Xialing Yang: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Yifeng Yu; Heli Lu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by grant from Jiangxi Provincial Natural Foundation (20212acb206022).

Data availability statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Contributor Information

Yifeng Yu, Email: 171018170@qq.com.

Heli Lu, Email: luheli0902@163.com.

References

- Baumeister R.F. Oxford University Press; 2005. The Cultural Animal: Human Nature, Meaning, and Social Life. [Google Scholar]

- Bolatov A.K., Gabbasova A.M., Baikanova R.K., Igenbayeva B.B., Pavalkis D. Medical Science Educator; 2021. Online or Blended Learning: the COVID-19 Pandemic and First-Year Medical Students' Academic Motivation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari S.R., Saba F. Depression, anxiety and stress as negative predictors of life satisfaction in university students. Rawal Med. J. 2017;42(2):255–257. [Google Scholar]

- Chai L., Xue J., Han Z.,Q. School bullying victimization and self-rated health and life satisfaction: the mediating effect of relationships with parents, teachers, and peers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020;117 [Google Scholar]

- Datu J.A.D., Mateo N.J. Gratitude and life satisfaction among Filipino adolescents: the mediating role of meaning in life. Int. J. Adv. Counsell. 2015;37(2):198–206. [Google Scholar]

- Datu J.A.D., King R.B., Valdez J.P.M., Eala M.S.M. Grit is associated with lower depression via meaning in life among Filipino high school students. Youth Soc. 2018;51(6):865–876. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E., Emmons R., Larsen R.J., Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Disabato D.J., Kashdan T.B., Short J.L., Jarden A. What predicts positive life events that influence the course of depression? A longitudinal examination of gratitude and meaning in life. Cognit. Ther. Res. 2017;41(3):444–458. [Google Scholar]

- Duong C.D. Personality and Individual Differences; 2021. The Impact of Fear and Anxiety of Covid-19 on Life Satisfaction: Psychological Distress and Sleep Disturbance as Mediators; p. 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X.,Y., Xu J., Sun L., Zhang J.T. Family functioning: theory, influencing factores, and its relationship with adolescent social adjustment. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2004;12(4):544–553. [Google Scholar]

- Febres J., Rossi R., Gaudiano B.A., Miller I.W. Differential relationship between depression severity and patients' perceived family functioning in women versus men. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2011;199(7):449–453. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318221412a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman D.B., Snyder C.R. Hope and the meaningful life: theoretical and empirical associations between goal? Directed thinking and life meaning. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2005;24(3):401–421. [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y.J., Fan Y.J., Su Z.Z., Li B.B., Li B., Liu N., Wang P.X. Correlation of sexual behavior change, family function, and male-female intimacy among adults aged 18-44 Years during COVID-19 epidemic. Sex. Med. 2021;9(1) doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson D.M., McLeod G.F.H., Horwood L.J., Swain N.R., Chapple S., Poulton R. Life satisfaction and mental health problems (18 to 35 years) Psychol. Med. 2015;45(11):2427–2436. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foroughi B., Iranmanesh M., Nikbin D., Hyun S.S. Are depression and social anxiety the missing link between facebook addiction and life satisfaction? the interactive effect of needs and self-regulation. Telematics Inf. 2019;43 [Google Scholar]

- Frankl V.E. Man's search for meaning. Pocket Books. 2005;67(September):671–677. [Google Scholar]

- Frasquilho D., de Matos M.G., Neville F., Gaspar T., de Almeida J.M.C. Parental unemployment and youth life satisfaction: the moderating roles of satisfaction with family life. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016;25(11):3214–3219. [Google Scholar]

- Glaw X., Hazelton M., Kable A., Inder K. Exploring academics beliefs about the meaning of life to inform mental health clinical practice. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020;34(2) doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman M.L., Gibson D.C., Keiser P.H., Gitari S., Raimer-Goodman L. Family, belonging and meaning in life among semi-rural kenyans. J. Happiness Stud. 2019;20(5):1627–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Guo L.P., Fan H.Y., Xu Z., Li J.Y., Chen T.L., Zhang Z.Y., Yang K.H. Prevalence and changes in depressive symptoms among postgraduate students: a systematic review and meta-analysis from 1980 to 2020. Stress Health. 2021;37(5):835–847. doi: 10.1002/smi.3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine S.J., Proulx T., Vohs K.D. The meaning maintenance model: on the coherence of social motivations. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2006;10(2):88–110. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1002_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill P.L., Turiano N.A. Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychol. Sci. 2014;25(7):1482–1486. doi: 10.1177/0956797614531799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.W., Zhang L.J., Wang J.Y., Xu L., Li Y., Guo M., Ma J.B., Xu X., Wang B.Y., Lu H.L. The structural characteristics and influential factors of psychological stress of urban residents in Jiangxi province during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross sectional study. Heliyon. 2021;7(8) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iftikhar N., Awais M., Ayoub S. Prevalence of stress in medical students of different medical colleges. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019;6(6):13143–13145. [Google Scholar]

- Karakose T., Polat H., Papadakis S. Examining teachers' perspectives on school principals' digital leadership roles and technology capabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability. 2021;13(23) [Google Scholar]

- Karakose T., Yirci R., Papadakis S. Exploring the interrelationship between COVID-19 phobia, work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and life satisfaction among school administrators for advancing sustainable management. Sustainability. 2021;13(15) [Google Scholar]

- Karakose T., Yirci R., Papadakis S., Ozdemir T.Y., Demirkol M., Polat H. Science mapping of the global knowledge base on management, leadership, and administration related to COVID-19 for promoting the sustainability of scientific research. Sustainability. 2021;13(17) [Google Scholar]

- Karaman M.A., Watson J.C. Examining associations among achievement motivation, locus of control, academic stress, and life satisfaction: a comparison of US and international undergraduate students. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2017;111:106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kaup S., Jain R., Shivalli S., Pandey S., Kaup S. Sustaining academics during COVID-19 pandemic: the role of online teaching-learning. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020;68(6):1220–1221. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_1241_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kekkonen V., Tolmunen T., Kraav S.L., Hintikka J., Kivimaki P., Kaarre O., Laukkanen E. Adolescents' peer contacts promote life satisfaction in young adulthood - a connection mediated by the subjective experience of not being lonely. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2020;167 [Google Scholar]

- Khalafallah A.M., Lam S., Gami A., Dornbos D.L., Sivakumar W., Johnson J.N., Mukherjee D. A national survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon burnout and career satisfaction among neurosurgery residents. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020;80:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugbey N., Asante K.O., Meyer-Weitz A. Depression, anxiety and quality of life among women living with breast cancer in Ghana: mediating roles of social support and religiosity. Support. Care Cancer. 2020;28(6):2581–2588. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert N.M., Stillman T.F., Baumeister R.F., Fincham F.D., Graham S.M. Family as a salient source of meaning in young adulthood. J. Posit. Psychol. 2010;5(5):367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Li A., Wang S., Cai M., Sun R., Liu X. Personality and Individual Differences; 2020. Self-compassion and Life-Satisfaction Among Chinese Self-Quarantined Residents during Covid-19 Pandemic: a Moderated Mediation Model of Positive Coping and Gender; p. 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., He W., Zhang X., Guo F., Cai J. The relationship between parenting style, coping style, index of well-being and life of meaning of undergraduates. China J. Heal. Psychol. 2014;22(11):1683–1685. [Google Scholar]

- Lightsey O.R., Boyraz G. Do positive thinking and meaning mediate the positive affect-life satisfaction relationship? Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2011;43(3):203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.Q., Gan Y.Q. Chinese meaning in life questionnaire revised in college students and its reliability and validity test. Chin. Ment. Health J. 2010;24(6):478–482. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.H., Ouyang C.N. Establishment of care service quality evaluation index system for the pension institutions combined with medical service. Chines. J. Health Pol. 2021;14(10):59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Loan L., Cong D.D., Thang H., Nga N.T.V., Van P.T., Hoa P.T. Entrepreneurial behaviour: the effects of the fear and anxiety of Covid-19 and business opportunity recognition. Entrep. Busin. Econom. Rev. 2021;9(3):7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst G.J., Stone D.M., Dulohery K., Scully D., Campbell T., Smith C.F. Strength, weakness, opportunity, threat (SWOT) analysis of the adaptations to anatomical education in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2020;13(3):301–311. doi: 10.1002/ase.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons Z., Wilcox H., Leung L.D.O. COVID-19 and the mental well-being of Australian medical students: impact, concerns and coping strategies used. Australas. Psychiatr. 2020;28(6):649–652. doi: 10.1177/1039856220947945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud M.S., Talukder M.U., Rahman S.M. Does 'Fear of COVID-19' trigger future career anxiety? An empirical investigation considering depression from COVID-19 as a mediator. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 2021;67(1):35–45. doi: 10.1177/0020764020935488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzi C., Vignoles V.L., Regalia C., Scabini E. Cohesion and enmeshment revisited: differentiation, identity, and well-being in two European cultures. J. Marriage Fam. 2010;68(3):673–689. [Google Scholar]

- Miller I.W., Ryan C.E., Keitner G.I., Bishop D.S., Epstein N.B. The mcmaster approach to families: theory, assessment, treatment and research. J. Fam. Ther. 2010;22(2):168–189. [Google Scholar]

- Moksnes U.K., Eilertsen M.E.B., Ringdal R., Bjornsen H.N., Rannestad T. Life satisfaction in association with self-efficacy and stressor experience in adolescents-self-efficacy as a potential modera. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019;33(1):222–230. doi: 10.1111/scs.12624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustika R., Yo E.C., Faruqi M., Zhuhra R.T. Evaluating the relationship between online learning environment and medical students' wellbeing during COVID-19 pandemic. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2021;28(5):108–117. doi: 10.21315/mjms2021.28.5.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasir R., Mustaffa M.B., Shahrazad W.S.W., Khairudin R., Salim S.S.S. Parental support, personality, self-efficacy as predictors for depression among medical students. J. Soci. Sci. Humanit. 2011;19:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ni X., Li X., Wang Y. The impact of family environment on the life satisfaction among young adults with personality as a mediator. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020:120. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolis L., Wakim A., Adams W., Bajaj P. Medical student wellness in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02837-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell M.B., Bentele C.N., Grossman H.B., Le Y., Steger M.F. You, me, and meaning: an integrative review of connections between relationships and meaning in life. J. Psychol. Afr. 2014;24(1):44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Olson D.H., Waldvogel L., Schlieff M. Circumplex model of marital and family systems. J. Family Theory Rev. 2000;22(2):144–167. [Google Scholar]

- Orsini C., Binnie V.I., Wilson S.L. Determinants and outcomes of motivation in health professions education: a systematic review based on self-determination theory. J. Educ. Evalu. Heal. Profess. 2016;13(19) doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2016.13.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkaya E., Cetin M., Ugurad Z., Samanc N. Evaluation of family functioning and anxiety-depression parameters in mothers of children with asthma. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2010;38(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra R.M.R. Depression and meaning of life in university students in times of pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020;9(3):223–242. [Google Scholar]

- Racine N., Plamondon A., Hentges R., Tough S., Madigan S. Dynamic and bidirectional associations between maternal stress, anxiety, and social support: the critical role of partner and family support. J. Affect. Disord. 2019;252:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reker G.T., Wong P.T.P. In: Emergent Theories of Aging. Birren J.E., Bengtson V.L., editors. Springer Publishing Company; 1988. Aging as an individual process: toward a theory of personal meaning; pp. 214–246. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowska A.M., Zmaczyńska-Witek B., Milena M., Kardasz Z. The mediating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between health locus of control and life satisfaction: a moderator role of movement disability. Disability and Health Journal. 2020;13(4) doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safa F., Anjum A., Hossain S., Trisa T.I., Hasan M.T. Immediate psychological responses during the initial period of the covid-19 pandemic among bangladeshi medical students. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021;122 doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmani S., Biderafsh A., Arani Z.A. The relationship between spiritual development and life satisfaction among students of qom university of medical sciences. J. Relig. Health. 2019;8 doi: 10.1007/s10943-018-00749-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satici B., Gocet-Tekin E., Deniz M.E., Satici S.A. Adaptation of the fear of covid-19 scale: its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. Int. J. Ment. Health Addiction. 2020;6 doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnettler B., Miranda-Zapata E., Grunert K.G., Lobos G., Hueche C. Depression and satisfaction in different domains of life in dual-earner families: a dyadic analysis. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2019;51(3) [Google Scholar]

- Shao R.Y., He P., Ling B., Tan L., Xu L., Hou Y.H., Kong L.S., Yang Y.Q. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychology. 2020;8(1) doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-00402-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M., Li L., Sun X., Wang L. Associations between symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and life satisfaction in medical students: the mediating effect of resilience. BMC Med. Educ. 2018;18(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1261-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiah Y.J., Chang F., Chiang S.K., Lin I.M., Tam W.C.C. Religion and health: anxiety, religiosity, meaning of life and mental health. J. Relig. Health. 2015;54(1):35–45. doi: 10.1007/s10943-013-9781-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sireli O., Aysev Soykan A. Examination of relation between parental acceptance-rejection and family functioning with severity of depression in adolescents with depression. Anadolu Psikiyatri Dergisi-Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;17(5):403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R., Kroenke K., Williams J.B. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternthal M.J., Williams D.R., Buck M. Depression, anxiety, and religious life: a search for mediators. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010;51(3):343–359. doi: 10.1177/0022146510378237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swami V., Chamorro-Premuzic T., Sinniah D., Maniam T., Kannan K., Stanistreet D., Furnham A. General health mediates the relationship between loneliness, life satisfaction and depression-A study with Malaysian medical students. Soc. Psychiatr. Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2007;42(2):161–166. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szczeniak M., Tuecka M. Family functioning and life satisfaction: the mediatory role of emotional intelligence. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020;13:223–232. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S240898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoemmes F., Mackinnon D.P., Reiser M.R. Power analysis for complex mediational designs using Monte Carlo methods. Struc. Eq. Modeling-A Multidis. J. 2010;17(3):510–534. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2010.489379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vate-U-Lan P. Psychological impact of e-learning on social network sites: online students' attitudes and their satisfaction with life. J. Comput. High Educ. 2020;32(1) -SI. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.H., Wang L., Shi M., Li X.L., Liu R., Liu J., Zhu M., Wu H.Z. Empathy, burnout, life satisfaction, correlations and associated socio-demographic factors among Chinese undergraduate medical students: an exploratory cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2019;19(1) doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1788-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.C., Peng J.X. Work-family conflict and depression in Chinese professional women: the mediating roles of job satisfaction and life satisfaction. Int. J. Ment. Health Addiction. 2017;15(2):394–406. [Google Scholar]

- Wei C., Yu C.F., Hong X.Z., Zheng Y.H., Zhou S.S., Sun G.J. Gratitude and life satisfaction among left-behind children: the mediating effect of anxiety and Depression. Chinese J. Child Health Care. 2015;23(3):290–292. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel K., Townsend J., Hawkins B.L., Russell B. Changes in family leisure functioning following a family camp for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Ther. Recreat. J. 2020;54(1):17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Zhao Q., Liu H., Zhu X.M., Wang K., Man J. Family functioning mediates the relationship between activities of daily living and poststroke depression. Nurs. Res. 2020;70(1):51–57. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X.J., Zhuo R., Li G.D. Migration patterns, family functioning, and life satisfaction among migrant children in China: a mediation model. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2019;22(1):113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Yun J.Y., Kim J.W., Myung S.J., Yoon H.B., Moon S.H., Ryu H., Yim J.J. Impact of COVID-19 on lifestyle, personal attitudes, and mental health among Korean medical students: network analysis of associated patterns. Front. Psychiatr. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.702092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H.K., Zhao J.B., Zhang X.Y. Mediating effect of life meaning between family functioning and suicide risk in freshmen. Chinese General Pract. 2018;21(36):4521–4526. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Ye L., Fu F., Zhang L.G. The influence of gratitude on the meaning of life: the mediating effect of family function and peer relationship. Front. Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.680795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.