Abstract

Objectives

This study aims: (1) to identify and describe similarities and differences in both adult and child COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, and (2) to examine sociodemographic, perception-related and behavioural factors influencing vaccine hesitancy across five West African countries.

Design

Cross-sectional survey carried out between 5 May and 5 June 2021.

Participants and setting

4198 individuals from urban and rural settings in Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Senegal and Sierra Leone participated in the survey.

Study registration

The general protocol is registered on clinicaltrial.gov.

Results

Findings show that in West Africa at the time only 53% of all study participants reported to be aware of COVID-19 vaccines, and television (60%, n=1345), radio (56%; n=1258), social media (34%; n=764) and family/friends/neighbours (28%; n=634) being the most important sources of information about COVID-19 vaccines. Adult COVID-19 vaccine acceptance ranges from 60% in Guinea and 50% in Sierra Leone to 11% in Senegal. This is largely congruent with acceptance levels of COVID-19 vaccinations for children. Multivariable regression analysis shows that perceived effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccines increased the willingness to get vaccinated. However, sociodemographic factors, such as sex, rural/urban residence, educational attainment and household composition (living with children and/or elderly), and the other perception parameters were not associated with the willingness to get vaccinated in the multivariable regression model.

Conclusions

Primary sources of information about COVID-19 vaccines include television, radio and social media. Communication strategies addressed at the adult population using mass and social media, which emphasise COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness and safety, could encourage greater acceptance also of COVID-19 child vaccinations in sub-Saharan countries.

Trial registration number

Keywords: COVID-19, public health, epidemiology, preventive medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The rural areas included in the study were located in the surroundings of the capital cities and may not be representative of more remote settings.

Data are drawn from a cross-sectional survey meaning that conclusions cannot be made regarding the causality of relationships.

The study relied on self-reported data, which can be susceptible to social desirability bias; however, the influence of this bias is likely to have had a minimal impact on this study’s main findings.

In Senegal, there was a limited number of observations due to particular ethical requirements in the country.

Introduction

Sufficient immunisation coverage against COVID-19 in particular also in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) is crucial in addressing the current pandemic.1 In Africa, as elsewhere, reaching the necessary herd immunity threshold is jeopardised by factors, such as the emergence of new SARS-CoV2 variants, inequitable access to COVID-19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy.2 Vaccine hesitancy can be defined as a ‘delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services’ and can vary ‘across time, setting, and vaccines’.3 4 In Africa, a recent survey conducted among 15 countries indicates that acceptance of adult COVID-19 vaccines varies from 94% and 93%, respectively, in Ethiopia and Niger to 65% and 59%, respectively, in Senegal and the Democratic Republic of Congo.2 5–7 However, little is known about acceptance of child COVID-19 vaccines. Furthermore, there are concerns that without appropriate interventions even in settings with relatively high reported levels of willingness to get vaccinated compared with countries such as the USA and Russia,8 those who are still hesitant may shift to completely refusing or maintain passive avoidance in seeking out immunisation.9 High levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy coupled with inequitable access to COVID-19 vaccines in LMICs represent a major problem in the global efforts to control the current COVID-19 pandemic.10 Furthermore, vaccine hesitancy might also revert the tremendous successes LMICs have made in increasing overall immunisation against other (childhood) infectious diseases,11 if hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccines translates into a more generalised hesitancy towards other vaccines, such as routine childhood vaccinations. Therefore, to build confidence and trust in COVID-19 vaccines, it is important to understand and address the reasons for vaccine hesitancy and the motivations behind the decision making of whether to get vaccinated or not. However, context-specific studies, which investigate factors influencing vaccine hesitancy towards adult and child COVID-19 vaccines in sub-Saharan Africa, are still far and few between.8 In this study, a community-based survey was carried out in five West African countries (Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Senegal and Sierra Leone) in order to: (1) identify and describe similarities and differences in both adult and child COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and (2) to examine sociodemographic, perception-related and behavioural factors influencing vaccine hesitancy across a subregion of Africa, which shares major cultural and geopolitical characteristics12 13

Materials and methods

Study area

The survey was conducted in the five West African countries Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Senegal and Sierra Leone. In all study countries, study sites were selected in consultation with the local principal investigators from among urban and rural communities in and around the capital cities of the countries, namely Ouagadougou, Conakry, Bamako, Dakar and Freetown, respectively.

Sample size

The study size was calculated to estimate the proportion of the population willing to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Assuming a proportion of 0.5 (conservative estimate leading to the largest sampling size), 385 individuals had to be interviewed per study country to receive an estimate with 5% precision. These sample size considerations were met in all countries apart from Senegal, where a considerable proportion of respondents had to be excluded from the analysis as they had reported to have never heard of any COVID-19 vaccines.

Sampling strategy

Participants were selected from among the general population within predefined rural and urban study areas. Similar proportions of interviewees were selected from among rural and urban areas. The number of interviews to be conducted was based on the overall sample size and was proportionally allocated according to the population size within the sampling clusters. A random sample was drawn using an adjusted random walk procedure, a procedure used in previous immunisation coverage studies.14 Within each cluster between 8 and 12 random walks were conducted, and an equal number of interviews were conducted per random walk. Each random walk started on a randomly assigned location mark. For this purpose, geographical maps of the selected clusters were drawn, for which random coordinates were marked using ascending numbers. Valid sampling points (eg, coordinates pointing to a house or in the proximity of a house) on each map were identified by the field teams. Coordinates were selected in consecutive order from these valid location marks in order to start the random walks. The random walk procedure was applied to select study participants as described in Lemeshow and Robinson.15 Once the sample was saturated per each starting point, a new one was used until the defined sample size was reached. Inclusion criteria for the study were: to be at least 18 years old, live in the study area and willingness to provide written informed consent. All those who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded from the study. In Senegal, the ethical commission asked to exclude from the study those who had been already vaccinated; for this reason, an additional exclusion criterion was added: have been offered the COVID-19 vaccination.

Data collection

Survey data were collected between 5 May and 5 June 2021. Respondents were invited to take part in face-to-face survey interviews using a 45-item questionnaire. The questionnaire uses measures as employed in other COVID-19 survey-based studies (eg, COSMO, COVID-19 Snapshot Monitoring, https://projekte.uni-erfurt.de/cosmo2020/web/) and were guided by the survey design recommendations by the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy.16 Questions were discussed with all local PIs (Principal Investogators) and adapted as appropriate to the countries’ context. The questionnaires were completed by trained local fieldworkers on tablets with KoBoToolbox software (V.2.0) installed. Questionaries were programmed to minimise data entry errors, for example, by applying predefined ranges for some variables. The questionnaire asked about respondents’ sociodemographic background characteristics and their perceptions, experience, confidence and decision making in relation to COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines, as well as past acceptance and perceptions of other vaccines. Depending on the preference of the respondents, interviews were conducted in French, English or one of the local languages. At the time of data collection, the COVID-19 vaccination roll-out was starting in the study countries, and part of our study population had already been offered a vaccine. In Senegal, this part of the population, on specific request of the country’s ethical commission, was excluded from the study analysis.

Analysis

The current study is a multicountry cross-sectional study. Descriptive statistics were used to apply plausibility checks, and no inconsistencies were found in the study data. Graphical and statistical methods were used to describe study data. Continuous variables were described using the median and the IQR, and categorical data were described using the frequency and percentages. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, no significance testing was applied. Some interviewees did not respond to all questions, and these missing data were excluded from the respective analysis. Thus, the denominator in some calculations may differ. Poisson regression models, with robust SEs, were calculated to analyse associations with vaccine hesitancy. For the model, vaccine hesitancy was dichotomised into no (definitely or probably do not want to be vaccinated) or yes (definitely or probably want to be vaccinated). Prevalence ratios (PRs) and the 95% CI were calculated. Categorical variables were dummy-coded to estimate PRs. This coding includes the categories yes, no and don’t know (dk). Bivariable models (outcome and one predictor variable) and multivariable regression model (outcome with all predictor variables, without variable selection) were calculated. Multivariable regressions were calculated for each country. Multilevel models to calculate pooled effect estimates were not applied because of the small number of countries. All analyses were done in R (V.4.1.0) using the sandwich packages (3.0–1) to calculate robust SEs.

Institutional review board and ethical considerations

Alongside a general study protocol, which defined the general rules for sampling strategy, sample size, selection of the recruitment areas and the ethical principles on which the survey is based on, country-specific protocols were developed. Data were collected according to a standard GCP procedure. The general protocol is registered on clinicaltrial.gov).

Patient and public

The patients and public were not involved in the design of the study and the research instrument mainly due to time constraints since the first survey wave was meant to be conducted in the early phases of vaccine rollout in the partner countries. However, the public has been engaged in the dissemination of the results. Two webinars (one in French and one in English) were organised on the 30 June 2021 in order to make the findings available to the local stakeholders in order to inform vaccination strategies in a timely manner. Additionally, individual reports have been submitted to the ethical commission of those countries, which have requested them so far (ie, Guinea and Mali).

Results

Study population characteristics

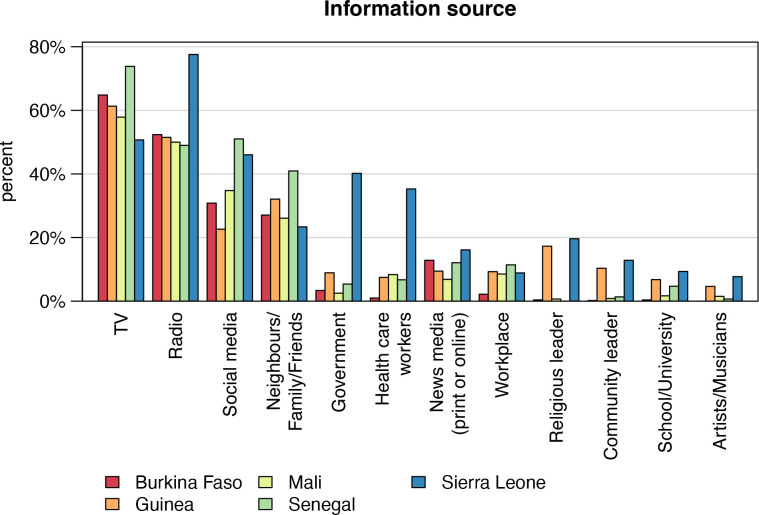

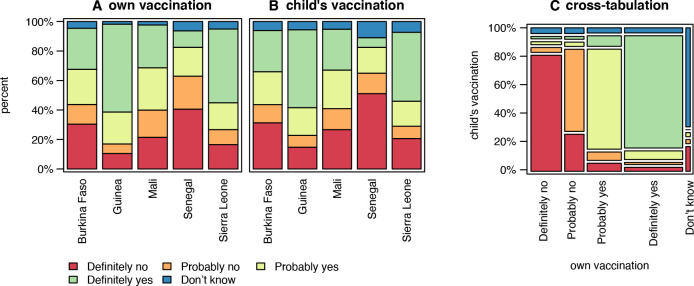

Among the 4198 study participants, 2242 (53%) were aware of COVID-19 vaccines, and data of these individuals were used for subsequent analyses. Figure 1A shows vaccine awareness across the study countries. In Senegal, only 19% (n=149) of the interviewees had heard about vaccines against COVID-19; however, in the other countries, awareness ranged between 50% (n=428) in Sierra Leone and 70% (n=598) in Mali. Respondents’ background characteristics stratified by country are described in table 1. In total, 1240 (55%) interviews were conducted in urban areas. The median age of the interviewees was 36 years with an IQR of 28–49 years and 42% (951) were female. The majority of study participants (1832; 85%) lived together with children and 39% (n=840) lived together with people aged ≥65 years. In total, 22% (n=496) had not completed any formal education, 19% (n=417) had attended primary/middle school and 59% (1,329) secondary school or higher. At the time of the survey (May 2021), COVID-19 vaccination had already been offered to 480 (21%) of the interviewees, the majority of whom were in the Guinean study group (n=312; 56%). Half of the respondents who had already been offered a COVID-19 vaccination (n=240; 50%) had subsequently been vaccinated, again, with the largest number in the Guinean study group (n=181; (58%) (figure 1B). Study participants were asked about their main sources for information about COVID-19 vaccines (figure 2). Among all participants, the most important sources mentioned were television (60%, n=1345), radio (56%; n=1258), social media (34%; n=764) and family/friends/neighbours (28%; n=634). Governmental sources were only mentioned by 12% (n=262); however, 40% (n=172) of interviewees from Sierra Leone ranked this as an important information source.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 vaccine awareness (A) and COVID-19 vaccination status (B) among the study population stratified by country (n=4198), 2021. Figure 1A depicts the proportion of respondents who have ever heard of COVID-19 vaccines stratified by country, and figure 1B shows the proportion of those study participants who actually accepted the COVID-19 vaccination when offered. In alignment with the requirements of the Ethical Committee in Senegal, those participants in Senegal who had already been offered a COVID-19 vaccination had to be excluded from this study.

Table 1.

Respondent background characteristics (A) and their perceptions of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines stratified by country (n=2242) (B)

| Burkina Faso | Guinea | Mali | Senegal | Sierra Leone | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| A: background characteristics | |||||

| Total | 506 (22) | 561 (25) | 598 (27) | 149 (7) | 428 (19) |

| Female gender | 254 (50) | 202 (36) | 226 (38) | 75 (50) | 194 (45) |

| Age (years)* | 34 (27–45) | 34 (27–47) | 43 (18–54) | 35 (26–47) | 35 (27–45) |

| Urban area | 276 (55) | 331 (59) | 366 (61) | 76 (51) | 191 (45) |

| Vaccination offered | 9 (2) | 312 (56) | 120 (20) | 0 (0) | 39 (9) |

| Vaccinated | 1 (0) | 181 (32) | 37 (6) | 0 (0) | 23 (5) |

| Living with children | 414 (88) | 410 (77) | 556 (93) | 135 (92) | 317 (78) |

| Living with elderly (≥65 years) | 79 (17) | 188 (35) | 342 (57) | 94 (64) | 137 (34) |

| Education | |||||

| No formal education | 113 (22) | 121 (22) | 162 (27) | 31 (21) | 69 (16) |

| Primary/middle school | 101 (20) | 96 (17) | 123 (21) | 57 (38) | 40 (9) |

| Secondary school or higher | 292 (58) | 344 (61) | 313 (52) | 61 (41) | 319 (74) |

| Ever refused a vaccination | 26 (5) | 102 (18) | 69 (11) | 4 (3) | 20 (5) |

| … for child | 3 (12) | 1 (1) | 3 (5) | 2 (50) | 1 (7) |

| … for child/oneself | 2 (8) | 10 (11) | 21 (34) | 0 (0) | 2 (13) |

| … for oneself | 21 (81) | 84 (88) | 38 (61) | 2 (50) | 12 (80) |

| B: perceptions of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines | |||||

| Worried about COVID-19 | |||||

| No | 325 (65) | 191 (35) | 171 (29) | 96 (64) | 136 (32) |

| Yes | 177 (35) | 362 (65) | 421 (71) | 53 (36) | 290 (68) |

| Feel at risk of infection | |||||

| No | 253 (50) | 187 (34) | 174 (29) | 80 (54) | 121 (28) |

| Yes | 179 (35) | 244 (44) | 332 (56) | 36 (24) | 260 (61) |

| Don’t know | 73 (14) | 126 (23) | 91 (15) | 33 (22) | 45 (11) |

| Vaccine protects against COVID-19 | |||||

| No | 81 (16) | 17 (3) | 74 (13) | 40 (27) | 23 (5) |

| Yes | 329 (66) | 434 (78) | 382 (66) | 87 (58) | 293 (69) |

| Don’t know | 91 (18) | 107 (19) | 123 (21) | 22 (15) | 106 (25) |

| COVID-19 vaccines are safe | |||||

| No | 166 (33) | 44 (8) | 152 (26) | 61 (41) | 19 (4) |

| Yes | 104 (21) | 201 (37) | 129 (22) | 33 (22) | 175 (41) |

| Don’t know | 234 (46) | 294 (55) | 304 (52) | 55 (37) | 230 (54) |

| Concerned about side effects | |||||

| No | 63 (13) | 130 (24) | 129 (22) | 22 (15) | 24 (6) |

| Yes | 395 (79) | 327 (60) | 321 (55) | 120 (81) | 266 (63) |

| Don’t know | 42 (8) | 90 (16) | 134 (23) | 7 (5) | 134 (32) |

| COVID-19 vaccines carry more risks | |||||

| No | 57 (12) | 144 (26) | 77 (13) | 20 (13) | 26 (6) |

| Yes | 307 (62) | 156 (28) | 283 (49) | 104 (70) | 167 (39) |

| Don’t know | 130 (26) | 249 (45) | 221 (38) | 25 (17) | 231 (54) |

*Median age and IQR (in brackets).

Figure 2.

Main sources of information about COVID-19 vaccines stratified by country (n=2242), 2021.

Perceptions of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines

Respondents’ perceptions of COVID-19 and COVID-19 vaccines are summarised in table 1. While more than half of all participants reported to be worried about the risk of getting infected with SARS-CoV-2 (n=1303, 59%), there were variations between countries ranging from 71% (n=421) of respondents who reported to be concerned about getting infected in Mali to only 35% (n=177) and 36% (n=53), in Burkina Faso and Senegal, respectively. Almost half of the interviewees felt currently at risk of getting infected (n=1051; 47%) with Sierra Leone having the highest number of respondents who reported to feel currently at risk of getting infected (n=260; 61%). While 69% (n=1525) of the study participants believe that the vaccine protects against COVID-19, half of the interviewed individuals reported to be unsure whether the vaccine is safe. In fact, in Senegal, 41% of the respondents (n=61) said that they believe COVID-19 vaccines to be unsafe. A considerable proportion of all respondents (n=1429; 65%) voiced concern about vaccine side effects, with the highest levels of concern reported in Senegal (n=120; 81%) and Burkina Faso (n=395, 79%). About half of the participants (n=1017; 46%) think COVID-19 vaccines carry more risk than routine vaccines. This perception varies from 62% in Burkina Faso (n=307) who believe this to be the case to 28% in Guinea (n=156).

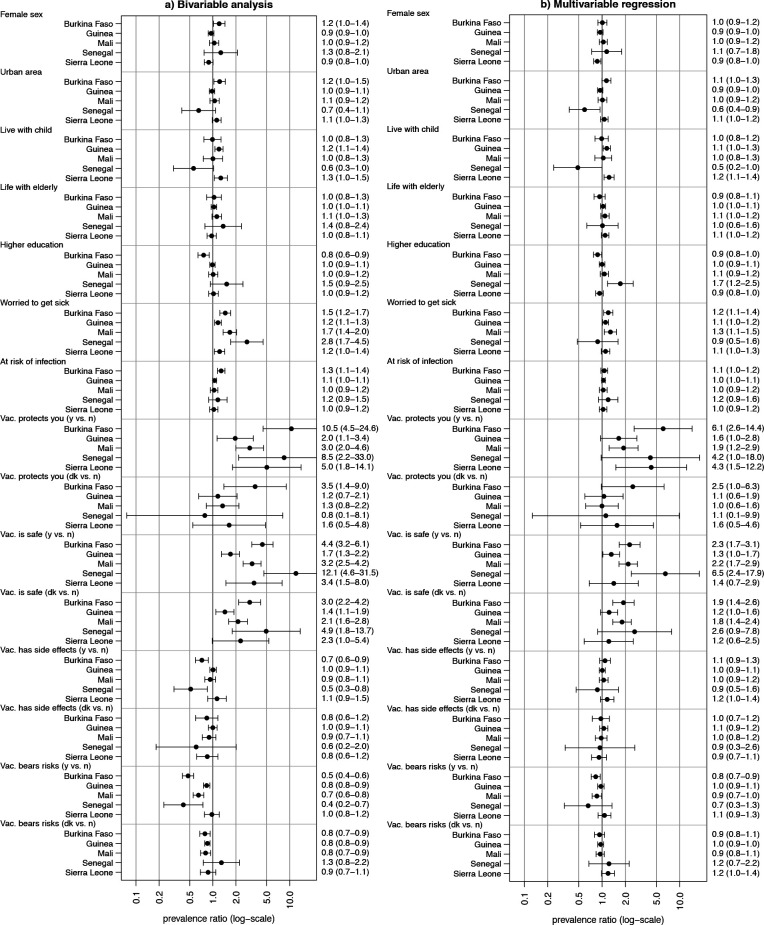

Vaccine acceptance, hesitancy and refusal in five West Africa countries

Overall, 39% (n=865) of the study population said they would definitely and 23% (n=514) would probably accept to get vaccinated against COVID-19, while 21% (n=465) of all participants would definitely and 13% (n=287) would probably refuse vaccination. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance ranged from 60% (n=330) in Guinea to 11% (n=16) in Senegal, whereas vaccine hesitancy ranged from 41% (n=58) in Senegal to 10% (n=58) in Guinea (figure 3A). Similarly, when asked about their willingness to have their own children vaccinated against COVID-19 in case a vaccine would be licenced for that age group, 36% (n=765) responded that they would accept, 25% (n=532) that they would refuse, whereas the remainder reported either that they would probably vaccinate their children against COVID-19 (21%; n=448), or that they would probably not have their children vaccinated (11%; n=235). Again, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance for children was highest in Guinea (n=283; 53%) and Sierra Leone (n=179; 47%) and the lowest in Senegal (n=9; 7%) (figure 3B). Figure 3C shows the congruence of those who would accept, hesitate or refuse vaccination against COVID-19 for themselves, with those who would do so when it comes to their own children. Eighty per cent (n=1690) of the respondents show the same level of willingness in both cases.

Figure 3.

Respondents’ willingness to get vaccinated and their willingness to have their children vaccinated against COVID-19 stratified by country, (n=2242), 2021. Figure 3A shows respondents’ COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, refusal and hesitancy for themselves 8 (A) and for their children (B), respectively. Figure 3C shows a cross-tabulation 9 of those who would accept, hesitate or refuse to get themselves vaccinated against COVID-19, with those who would accept, hesitate or refuse to have their children vaccinated against COVID-19.

Factors influencing acceptance, hesitancy and refusal

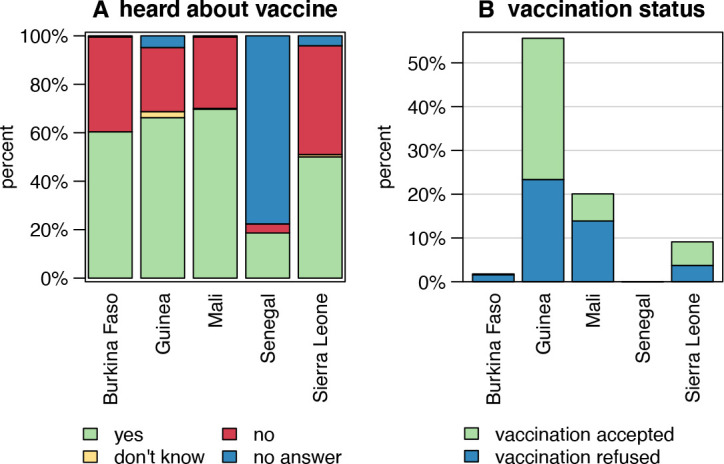

Of all respondents 1926 (86%) who were included in the Poisson regression models (figure 4), 22% came from Burkina Faso (n=433), 25% from Guinea (n=484), 27% from Mali (n=524), 7% (n=132) from Senegal and 18% (n=353) from Sierra Leone. Study participants with missing values in the independent variables had to be excluded from the regression analysis.

Figure 4.

Bivariable (A) and multivariable prevalence ratios (PRs) (B) for willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19 (n=1926), 2021. Dots represent the estimated PRs, and the six whiskers represent the 95% CI. Vac., vaccine; y, yes; n, no; dk, don’t know.

Results from the bivariable (figure 4A) and multivariable (figure 4B) regression are summarised in figure 4. The multivariable regression (figure 4B) showed that the perceived effectiveness of a vaccine to protect from COVID-19 and safety of COVID-19 vaccines increased the willingness to get vaccinated. Strongest associations with the perception of vaccine protection were observed for Burkina Faso (PR=6.1; 95% CI 2.6 to 14.4), Sierra Leone (PR=4.3; 95% CI 1.5 to 12.2) and Senegal (PR=4.2; 95% CI 1.0 to 18.0). Strongest association with vaccine safety was shown for Senegal (PR=6.5; 95% CI 2.4 to 17.9), while for the other countries PRs about two or lower were observed. However, sociodemographic factors, such as sex, rural/urban residence, educational attainment and household composition (living with children and/or elderly), and the other perception parameters were not associated with the willingness to get vaccinated in the multivariable regression model. In the bivariable regression analysis (figure 4A), the belief that the vaccine has side effects or that the vaccine carries more risks compared with routine vaccines lowers the willingness to get vaccinated. However, this effect was no longer present in the multivariable regression, which could indicate that associations were confounded. Overall, the findings were fairly consistent across countries.

Discussion

This study presents findings from a multicountry survey on a thus far under-researched topic: factors influencing COVID-19 adult and child vaccine hesitancy in sub-Saharan Africa. Main findings from the survey, which was conducted in five West African countries (Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Senegal and Sierra Leone) include, first, that at the time of data collection overall levels of COVID-19 vaccine awareness were strikingly low. Out of the 53% of respondents (n=2242) who reported to be aware of COVID-19 vaccines, levels of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance varied and ranged from 60% (n=330) in Guinea to 11% (n=16) in Senegal, conversely vaccine hesitancy ranged from 41% (n=58) in Senegal to 10% (n=58) in Guinea (figure 3A). One explanation for the lower levels of vaccine hesitancy in Guinea and Sierra Leone could be that these two countries have built on experiences from past epidemics, such as the devastating Ebola epidemic in 2014–201617 and greater exposure to Ebola vaccinations and vaccination campaigns.18 It is possible that the major investments in community-based interventions19 to increase the acceptability of a newly released vaccine might have a role in the greater acceptance of vaccines against COVID-19.

Second, to our knowledge, this study is the first to look into the relationship between acceptance of both adult and child COVID-19 vaccinations in sub-Saharan Africa. Our findings show that the adults’ willingness to get vaccinated was largely congruent with the intention to have their own children vaccinated against COVID-19 should an appropriate vaccine becomes available/accessible (figure 3C). This stands in contrast to previous research, for instance in England, which shows that study participants were more likely to accept a COVID-19 vaccine for themselves than their child/children.20 However, other studies in high-income countries have shown that adult vaccine hesitancy may further reduce parental intent to have their children vaccinated, through mechanisms such as distrust, and concerns around vaccine safety and efficacy.21 This may suggest that as COVID-19 vaccination strategies are moving towards child immunisation22 in our study region, communication and awareness-raising approaches targeting adults may also have a positive impact on COVID-19 vaccine coverage of children.

Third, consistent with other studies, vaccine hesitancy among the study countries is primarily explained by concerns over the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines,23–25 rather than age or educational attainment.8 However, in contrast to other studies on vaccine hesitancy in LMIC, gender and rural versus urban setting did not explain the difference.26

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the most popular source of COVID-19 related information among the study population are television, radio and social media, rather than, for example, governmental sources and healthcare workers (figure 2), which is in line with recent literature.27 Previous research has shown that individuals who inform themselves mostly relying on social media as primary source of information are more likely to be hesitant than those drawing more on professional sources of information.28 Thus, as shown by research concerned with other health topics, such as reproductive health, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, social media needs to be used more effectively as a tool to communicate correct and appropriate information about COVID-19 vaccinations.29 30

Overall, only 39% of all participants included in the study reported that they would accept a vaccination against COVID-19, 21% in the group said they would refuse and 36% said they were still hesitant. Strikingly, 55% of those who had previously been offered vaccination against COVID-19 declined it when the opportunity arose (figure 1B). Considerable levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and refusal coupled with inequitable access to vaccines and suboptimal vaccination coverage represent a complex challenge in these countries. Going forward, the possibility of a detrimental knock-on effect of lack of confidence in COVID-19 vaccines on the uptake of, for instance, childhood routine vaccinations, should be considered. There is evidence to suggest that this could revert the tremendous successes African countries have had in terms of increasing access to immunisation and reducing child deaths.31

Finally, while this study managed to conduct a baseline survey in a timely manner to capture the moment in time when COVID-19 vaccination campaigns—for both adults and children—had not yet or only just started to roll out in a region of Africa hat has a number of common historical, cultural and geopolitical characteristics, it is not without limitations. First, the study relied on self-reported perceptions and behaviour, and responses are therefore susceptible to social desirability bias. However, trained local fieldworkers experienced in administering survey questionnaires and fluent in local languages and dialects helped to minimise this risk. Furthermore, the survey included both urban and rural areas; however, the rural areas surrounding the capital cities may not be representative of more remote settings. The estimated target sample sizes were met in four out of the five study countries. However, in Senegal, there were particular ethical requirements that needed to be adhered to, and there was a particularly high number of respondents who reported to not be aware of COVID-19 vaccines, which led to a limited number of observations and decreased the power of the data collected for this country. Finally, data are drawn from a cross-sectional survey, meaning that conclusions cannot be made regarding causality of relationships. Going forward, longitudinal research is needed to monitor vaccine hesitancy and its determinants in this region over time.

Conclusion

High vaccination coverage represents one of the most effective measures to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic32 but is jeopardised by vaccine hesitancy. Addressing vaccine hesitancy is particularly relevant in countries, where access to vaccines is limited. Communication strategies addressed at the adult population using mass and social media and emphasising vaccine efficacy and safety could encourage greater acceptance also towards COVID-19 child vaccinations in the countries included in the study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the participants and the field team including drivers and IT staff who contributed to the success of the study. A special mention to data collectors: Burkina Faso: Mamadou Baduon, Adiaratou Bamba, Betiani Pierre Coulibaly, Mohamed Dabre, Ingrid Kere, Oumpanhala Elisée Lompo, Aboubacar B Ouattara, Charles Henri Oeudraogo, Wendtoin Athali Ouedraogo, Paterne Wendpouire Sawadogo, Ramondé-Wendé Alphonsine Inès Sawadogo, Wendgouda Félicité Tapsoba, Rokia Yabre, Moustapha Yoada; Guinea: Fatoumata Adama Diallo, Roufoudati Said, Ahmed Doukouré, Barry Abdourahmane Barry, Tolno Macky Tolno, Mamadou Lamarana Cira Diallo, Mamadou Maladho Diallo, Mariam Camara, Ansoumane Sangare, Marlyatou Diallo, Thierno Mamadou Diallo, Fodé Youssouf Diallo, Mamadou Oury Diallo, Fatoumata Binta Bah, Pascal Traore, Soufyane Mohamat Ahmed, Fatoumata Binta Kann, Adama Sangare, Hassane Diawara, Saoudatou, Diallo, Ibrahima Bah; Mali: Abdoulaye Sidibe, Ousmarne Telly, Youssouf Keita, Amadou Coulibaly, Mountaga Diallo, Fatoumata S Keita, Salimata Sangaré, Fallaye B Sissoko, Baba Alpha Oumar Wangara, Mohamed Dramé; Senegal: Abdoulaye Moussa Diallo, Serigne Abdou Lahat Ndiaye, Hélène Agnès Diene, Delphine Mariata Bousso, Martine Eva Tine, Coumba Ka, Mouhamed Fall, Mademba Lo; Sierra Leone: Bockarie Kemokai, Safiatu Sengeh, Amina Kargbo, Karim Dubumya, Shaika Sombi, Alimany Kargbo, Sandee Mbawah, Madda Rogers, Mohamed Alie Kamara and Christiana Samba. We would like to thank the Global Health Protection Program of the German Federal Ministry of Health, which funded the project. A special thanks to all the country authorities who allowed the implementation of this study and were supportive of its activities.

Footnotes

SLBF and RK contributed equally.

DIP and DF contributed equally.

Contributors: SF, RK, DIP and DF contributed to the conceptualisation and drafting of the manuscript; SF, RK, SD, MT, RS, HGO, TS, AMB, AKM, COD, JM, DIP and DF contributed to the conceptualisation of the study; SF, SD, MT, HGO, TLS, AMB, AM, COD, SD, KC, MH, PD, DIP and DF contributed to the set-up and implementation of data collection; RK performed data analysis; DIP designed the investigation tool; DF, RS and JM contributed to the financial aspects of the study; DF coordinated data collection, data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. DF is the guarantor of this publication. SF and RK equally contributed to the manuscript. DF and DIP equally contributed to the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Global Health Protection Program (GHPP) of the German Federal Ministry of Health grant number FKZ 2517GHP704.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Ethics Committee(s): Äeztekammer Hamburg, COMITÉ D’ÉTHIQUE POUR LA RECHERCHE EN SANTÉ Burkina Faso, Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé (CNERS) Guinea, Comité national d’éthique pour la santé et les sciences de la vie – CNESS Mali, Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé (CNERS) Senegal, Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (SLERC) Sierra LeoneID: 2021-10550-BO-ffID: 2021-05-115ID: 97/CNERS/21ID: 2021/118/CE/USTTBID: 00000065/MSAS/CNERS/SPID: SLERSC deliberated 11.05.21 – no official code. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Viana J, van Dorp CH, Nunes A, et al. Controlling the pandemic during the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination rollout. Nat Commun 2021;12:1–15. 10.1038/s41467-021-23938-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aschwanden C. Five reasons why COVID herd immunity is probably impossible. Nature 2021;591:520–2. 10.1038/d41586-021-00728-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A. Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-19. Vaccines 2021;9:19–21.33406694 [Google Scholar]

- 4. MacDonald NE, Eskola J, Liang X, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy . Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015;33:4161–4. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tornero-Molinaa J, Sánchez-Alonsoc F, Fernández-Pradaa M. Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID-. Ann Oncol 2020:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med 2021;27:225–8. 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. AFRICA CDC . COVID-19 Vaccine Perceptions: A 15-country study [Internet], 2021. Available: file:///Users/danielafusco/Downloads/COVID-19%20Perception%20Survey%20Final%20Report%2020.02.2021%20(1).pdf

- 8. Solís Arce JS, Warren SS, Meriggi NF, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Med 2021;27:1385–94. 10.1038/s41591-021-01454-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ekwebelem OC, Yunusa I, Onyeaka H, et al. COVID-19 vaccine rollout: will it affect the rates of vaccine hesitancy in Africa? Public Health 2021;197:12–14. 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Truong J, Bakshi S, Wasim A. What factors promote vaccine hesitancy or acceptance during pandemics? A systematic review and thematic analysis. Health Promot Int 2021;9:daab105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bangura JB, Xiao S, Qiu D, et al. Barriers to childhood immunization in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1108. 10.1186/s12889-020-09169-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Defor S, Kwamie A, Agyepong IA. Understanding the state of health policy and systems research in West Africa and capacity strengthening needs: Scoping of peer-reviewed publications trends and patterns 1990-2015. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15:55. 10.1186/s12961-017-0215-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uneke CJ, Sombie I, Johnson E, et al. Lessons learned from strategies for promotion of evidence-to-policy process in health interventions in the ECOWAS region: a rapid review. Niger Med J 2020;61:227. 10.4103/nmj.NMJ_188_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. WHO . Vaccination coverage cluster surveys: reference manual, 2015: 3. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lemeshow S, Robinson D. Surveys to measure programme coverage and impact: a review of the methodology used by the expanded programme on immunization. World Health Stat Q 1985;38:65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, et al. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. Vaccine 2015;33:4165–75. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahanhanzo C, Johnson EAK, Eboreime EA, et al. COVID-19 in West Africa: regional resource mobilisation and allocation in the first year of the pandemic. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e004762–11. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kucharski AJ, Eggo RM, Watson CH, et al. Effectiveness of ring vaccination as control strategy for Ebola virus disease. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:105–8. 10.3201/eid2201.151410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lhomme E, Modet C, Augier A, et al. Enrolling study personnel in Ebola vaccine trials: from guidelines to practice in a non-epidemic context. Trials 2019;20:1–6. 10.1186/s13063-019-3487-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bell S, Clarke R, Mounier-Jack S, et al. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: A multi-methods study in England. Vaccine 2020;38:7789–98. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Temsah M-H, Alhuzaimi AN, Aljamaan F, et al. Parental attitudes and Hesitancy about COVID-19 vs. routine childhood vaccinations: a national survey. Front Public Health 2021;9:752323. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.752323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ledford H. Should children get COVID vaccines? what the science says. Nature 2021;595:638–9. 10.1038/d41586-021-01898-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaplan RM, Milstein A. Influence of a COVID-19 vaccine's effectiveness and safety profile on vaccination acceptance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021;118:e2021726118. 10.1073/pnas.2021726118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, et al. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 2020;26:100495. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kreps S, Dasgupta N, Brownstein JS, et al. Public attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccination: the role of vaccine attributes, incentives, and misinformation. npj Vaccines 2021;6:1–7. 10.1038/s41541-021-00335-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bono SA, Faria de Moura Villela E, Siau CS, et al. Factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: an international survey among low- and middle-income countries. Vaccines 2021;9:515. 10.3390/vaccines9050515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Glik D, Massey P, Gipson J, et al. Health-Related media use among youth audiences in Senegal. Health Promot Int 2016;31:73–82. 10.1093/heapro/dau060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Du F, Chantler T, Francis MR, et al. Access to vaccination information and confidence/hesitancy towards childhood vaccination: a cross-sectional survey in China. Vaccines 2021;9:201–13. 10.3390/vaccines9030201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Borzekowski DLG, Fobil JN, Asante KO. Online access by adolescents in Accra: Ghanaian teens' use of the Internet for health information. Dev Psychol 2006;42:450–8. 10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Denno DM, Hoopes AJ, Chandra-Mouli V. Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:S22–41. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Adamu AA, Jalo RI, Habonimana D. Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID- 19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier connect, the company ’ S public news and information 2020.

- 32. Marziano V, Guzzetta G, Mammone A. Return to normal: COVID-19 vaccination under mitigation measures. medRxiv 2021:2021.03.19.21253893. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.