Abstract

Refractory coeliac disease (RCD) occurs when patients with confirmed CD have continuous or recurrent malabsorption and enteropathy after at least 12 months on a gluten-free diet. Differentiating between type I and type II RCD is key as the latter is associated with T-cell aberrancy and considered prelymphoma, with high mortality rates. Current treatment regimens for type II RCD include corticosteroids, biologics and chemotherapy, but there are no proven therapies for this serious condition. Our patient is a middle-aged woman who developed postpartum type II RCD. When she failed multiple drug classes, we did a trial of tofacitinib. Our clinical experience with use of a janus kinase inhibitor was successful, with no associated adverse events. This is the first report in the literature of RCD remission in response to tofacitinib. The use of this novel agent shows promise in reversing this potentially fatal condition.

Keywords: Small intestine, Coeliac disease, Drugs: gastrointestinal system, Nutrition, Malabsorption

Background

Coeliac disease (CD) is a gluten-associated enteropathy that often is fully treated with dietary modifications, however a small subset of patients progress to develop refractory CD (RCD). A diagnosis of RCD is made when a patient has signs and symptoms of malabsorption along with enteropathy after at least 12 months of a strict gluten-free diet (GFD). Type II RCD is defined by the presence of aberrant, clonal T-cell intraepithelial lymphocytes that are not present in type I RCD.1 Identifying this subset of patients is crucial in light of the difference in outcomes between those with type I RCD and type II. While Type I RCD is associated with a 5-year survival of 80%–96% with deaths from malabsorption or non-CD-related causes, type II RCD has a 5-year survival of 44%–58%, which is tied to high rates of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL).2–5 Thus, there is a strong impetus to early diagnosis, aggressive treatment and reversal of the enteropathy in patients with type II RCD.

Case presentation

Our patient is a woman in her 40s with a medical history significant for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and known positive coeliac serology, who was initially admitted to our sister academic medical centre for protein-losing enteropathy. Although she had previously been on a GFD for a year after positive CD screening, in light of new constipation, bloating and foggy mind, she reintroduced gluten to her diet 3 years prior to her pregnancy without recurrence of symptoms. She stayed on a gluten-containing diet until 1-month postpartum, when she developed epigastric pain, nausea, diarrhoea (with 2–3 loose to watery stools daily), along with bilateral lower extremity oedema. She reinitiated her GFD 2 months postpartum.

At the time of initial hospital admission, she was 5 months postpartum with the above symptomatology and had been on a GFD continuously for 3 months. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy showed marked flattening of the duodenal villi and scalloping suggestive of CD, and biopsies confirmed the diagnosis with Marsh 3B lesions. She was discharged to outpatient setting on a GFD and referred to our tertiary CD clinic for management.

During her initial outpatient visit in our CD clinic, she was noted to be hypotensive with anasarca, diagnosed with coeliac crisis, and urgently sent for readmission. At this time, the patient had been on a GFD for a total of 4 months.

Investigations and treatment

She was treated in-house with 72 hours of intravenous solumedrol 20 mg every 12 hours and then transitioned to open-capsule protocol budesonide 3 mg three times a day. During that admission she underwent capsule endoscopy which showed grossly abnormal small bowel with diffuse ulcerations, oozing of blood, mosaicism, diffuse villous blunting and a small bowel stricture (figure 1A). These findings were further evaluated by a single balloon enteroscopy. She was subsequently diagnosed with ulcerative jejunitis (figure 1B) with repeat biopsies showing Marsh 3A-B lesions (figure 2A–C) with T-cell receptor gamma locus gene rearrangement demonstrating abnormal clonality and immunohistochemistry with dominant loss of CD8 expression, all compatible with type II RCD.

Figure 1.

Wireless capsule endoscopy (A) and subsequent enteroscopy findings with ulcerative jejunitis (B).

Figure 2.

Jejunum biopsy from our patient (H&E, ×200 original magnification) showing moderate to severe villous atrophy (A) and an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes with an abnormal immunophenotype characterised by expression of CD3 (B) with near-complete absence of CD8 expression (>90% loss) (C). These findings were consistent with Marsh 3B–C. Subsequently, the duodenal bulb biopsy from our patient during tofacitinib (H&E, ×100 and ×100 original magnification) showing normal villous architecture with focal areas of crypt hyperplasia. The is still an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes. The findings are consistent with Marsh 1–2 (D).

Enteroscopy on budesonide for 3 months showed corticosteroid-resistant RCD with persistent ulcerative jejunitis and worsening Marsh 3B-C lesions with marked loss of CD8 expression. She was started on a hyperstrict GFD with our expert CD dietician, and switched to infliximab after nearly 6 months on budesonide. She was induced with infliximab and was on maintenance dosing for a total of 9 months with endoscopic resolution of her ulcerative jejunitis but only a mild histological improvement to Marsh 3A, with unchanged T-cell aberrancy. Endoscopic improvement was also documented during a concurrent repeat capsule endoscopy.

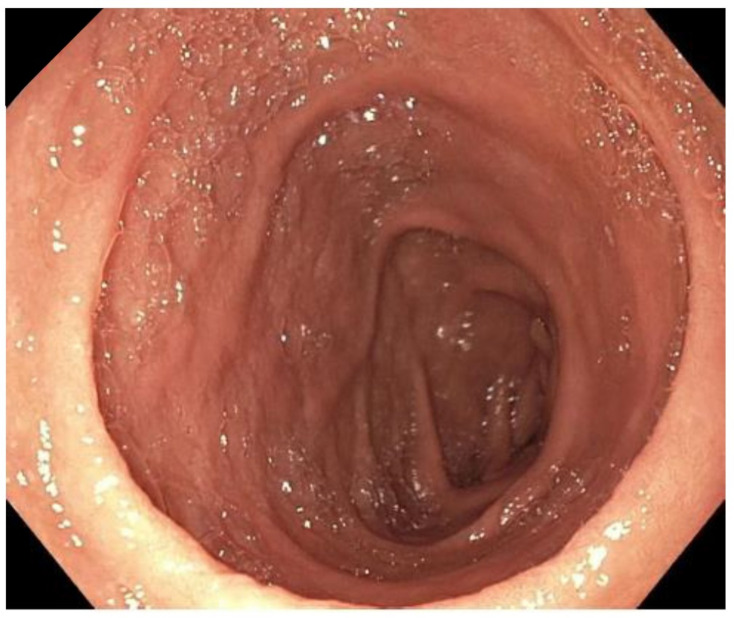

Due to corticosteroid and anti-TNF refractory disease, despite very strict gluten avoidance, she was referred to oncology for a trial of cladribine, unfortunately without histological response therefore a second cycle was not given. The patient was now about 18 months out from diagnosis of type II RCD, which is associated with about 50% risk of EATL in 5 years, so it was imperative to continue finding an effective regimen for this prelymphoma state. In light of positive yet statistically insignificant results of AMG714, anti-interleukin (IL)-15 monoclonal antibody, and in accordance with the 2019 European Society for the Study of Coeliac Disease guideline for CD and other gluten-related disorders,6 we started off-label use of tofacitinib (Xeljanz, Pfizer), a janus kinase (JAK) 1/3 inhibitor, at 10 mg two times per day, after discussing risks vs benefits of the treatment with the patient and obtaining her consent to start treatment. Discussion of associated adverse events, including thromboembolic ones, was conducted, and pretreatment labs including lipid profile, kidney and liver function tests, complete blood count, as well as tuberculosis and hepatitis B screening were completed. This oral drug is often used by gastroenterologists to treat ulcerative colitis. Tofacitinib works by inhibiting the JAK from activating signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) protein. Inhibition of STAT leads to decreased cytokine production, including IL-15 inhibition, which plays a key role in CD. Four months after the start of tofacitinib therapy, the patient had a repeat upper endoscopy, which showed improvement in her duodenopathy (figure 3) with biopsies confirming down-staging of her disease to Marsh 1–2 lesions (figure 2C) and near-normalisation of her CD serologies (table 1). At that time the patient’s tofacitinib dose was lowered to 5 mg two times per day, to minimise the risk of potential side effects. Aside for close symptom and laboratory monitoring, she is scheduled for a repeat upper endoscopy with biopsies in 3–6 months after dose reduction to confirm sustained treatment response.

Figure 3.

Marked improvement of enteropathy during tofacitinib therapy.

Table 1.

Trend of pertinent laboratory values and histology throughout patient’s treatments

| Initial admission Time 0 |

Coeliac crisis time 2 weeks |

After budesonide time 3 months |

After infliximab time 1 year |

After cladribine time 1.5 years |

During tofacitinib time 2 years |

|

| WCC | 5.0 | 2.7 (L) | 7.5 | 7.1 | 4.2 | 3.2 |

| Haemoglobin | 10.7 (L) | 10.9 (L) | 12.1 | 11.7 | 13.2 | 12.0 |

| Platelets | 734 (H) | 539 (H) | 707 (H) | 298 | 362 | 373 |

| CRP | 1.2 (H) | <0.3 | <0.3 | <0.3 | <0.3 | <0.3 |

| DGP IgA | 237.7 (H) | 205.2 (H) | 186.9 (H) | 53.9 (H) | 57.7 (H) | 48 (H) |

| TTG IgA | 300.5 (H) | 206.0 (H) | 152.3 (H) | 33.1 (H) | 44.3 (H) | 5 |

| EMA IgA | <1:10 | Positive | Positive | <1:10 | <1:10 | <1:10 |

| Pathology | Marsh 3B | Marsh 3A–B | Marsh 3B–C | Marsh 3A | Marsh 3A | Marsh 1–2 |

(H)=high; (L)=low.

TTG/DGP normal reference <20 U/mL.

Bold text indicates abnormal values

CRP, C reactive protein; DGP, deamidated gliadin peptide; EMA, endomysial Abs; TTG, transglutaminase; WCC, white cell count.

Outcome and follow-up

This was the first-time the patient achieved such results in the 2 years since presenting with coeliac crisis and being diagnosed with ulcerative jejunitis/type II RCD. Along with endoscopic, serological and immunohistochemical improvement, she reported feeling well with minimum symptoms. She was updated that her RCD was in remission and we reduced her tofacitinib dose to 5 mg two times per day to reduce associated adverse events. Additionally, she was counselled to remain on a strict GFD. She is scheduled for close endoscopic surveillance.

Discussion

The exact prevalence of RCD is not well known, with the most reliable data suggesting the rate is less than 1.5% of all patients with CD and less than 1% having specifically type II RCD.7 However, malabsorption, malignancy, morbidity and mortality are known complications in type II RCD.1 7 8 Currently, the best clinical practice in managing RCD advocate for off-label medication treatment in adjunct to a strict GFD. Yet those same guidelines acknowledge the absence of treatments with proven efficacy in type II RCD.6 9 The European guidelines discuss the potential use of AMG714 or JAK inhibitor after unsuccessful treatment with corticosteroids, immunomodulators and chemotherapy in the most refractory of CD cases. The latter recommendation is also based on efficacious tofacitinib use in an IL-15 transgenic CD mouse model. Our clinical experience with the use of a JAK inhibitor was successful, after several stepwise treatment failures, with no associated adverse events. The use of this novel agent shows promise in reversing this prelymphoma state. Although a prior case report in a patient on a gluten-containing diet treated for alopecia has shown effectiveness in inducing histological remission in uncomplicated CD, we recommend that at this time tofacitinib be considered in refractory or complicated CD due to the safety profile and long-term treatment duration.10 Future JAK-inhibitor research in needed in RCD, non-responsive (or slow responsive) CD, and even uncomplicated CD.

Patient’s perspective.

I didn’t know how bad my situation was until I read the case report. I feel so lucky to be better and I’m happy to share my experience. I hope that it will help others. I am grateful for my UCLA care providers who saved my life.

Learning points.

Type II refractory coeliac disease (RCD) is a prelymphoma state with a 5-year mortality of 50%.

There are no proven treatments for type II RCD.

Janus kinase inhibitors, such as tofacitinib, should be considered in patients with type II RCD that fail to respond to immunosuppressive agents, immunomodulators and/or biologics.

Tofacitinib induced remission in our patient with ulcerative jejunitis/type II RCD.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the the writing and editing of the paper. JKG and GAW providered clinical care for the patient. AK analysed the histology and reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Cellier C, Delabesse E, Helmer C, et al. Refractory sprue, coeliac disease, and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. French coeliac disease Study Group. Lancet 2000;356:203–8. 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02481-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubio-Tapia A, Malamut G, Verbeek WHM, et al. Creation of a model to predict survival in patients with refractory coeliac disease using a multinational registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:704–14. 10.1111/apt.13755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malamut G, Afchain P, Verkarre V, et al. Presentation and long-term follow-up of refractory celiac disease: comparison of type I with type II. Gastroenterology 2009;136:81–90. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Toma A, Verbeek WHM, Hadithi M, et al. Survival in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma: retrospective evaluation of single-centre experience. Gut 2007;56:1373–8. 10.1136/gut.2006.114512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubio-Tapia A, Kelly DG, Lahr BD, et al. Clinical staging and survival in refractory celiac disease: a single center experience. Gastroenterology 2009;136:99–107. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilus T, Kaukinen K, Virta LJ, Collin P, et al. Refractory coeliac disease in a country with a high prevalence of clinically-diagnosed coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:418–25. 10.1111/apt.12606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss G. Diagnosis and management of Gluten-Associated disorders: a clinical casebook. Springer, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al. Acg clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:656–76. 10.1038/ajg.2013.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Toma A, Volta U, Auricchio R, et al. European Society for the study of coeliac disease (ESsCD) guideline for coeliac disease and other gluten-related disorders. United European Gastroenterol J 2019;7:583–613. 10.1177/2050640619844125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wauters L, Vanuytsel T, Hiele M. Celiac disease remission with tofacitinib: a case report. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:585. 10.7326/L20-0497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]