Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of belimumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in China.

Methods

In this phase 3, open-label extension period, eligible completers of study BEL113750 (NCT01345253) received intravenous belimumab 10 mg/kg monthly for ≤6 years. The primary endpoint was safety. Secondary endpoints included the SLE Responder Index (SRI)-4 response rate, severe SLE flares and changes in prednisone use. Analyses were based on observed data from the first dose of belimumab through to study end.

Results

Of the 424 patients who received belimumab, 215 (50.7%) completed the study, 208 (49.1%) withdrew and 1 patient died. Overall, 359/424 (84.7%) patients had adverse events (AEs), and 96/424 (22.6%) had serious AEs. 26/424 (6.1%) patients discontinued study treatment/withdrew from the study due to AEs. Postinfusion systemic reaction rate was 1.5 events/100 patient-years. Herpes zoster infection rate was 3.0 events/100 patient-years, of which 0.4 events/100 patient-years were serious events. One papillary thyroid cancer and one vaginal cancer were reported in year 0–1 and year 3–4, respectively. There were no completed suicides/suicide attempts and no reports of serious depression. The proportion of SRI-4 responders increased progressively (year 1, week 24: 190/346 (54.9%); year 5, week 48: 66/82 (80.5%)). Severe flares were experienced by 55/396 (13.9%) patients. For 335 patients with baseline prednisone-equivalent dose >7.5 mg/day, the number of patients with a dose reduction to ≤7.5 mg/day increased over time (year 1, week 24: 30/333 (9.0%); year 5, week 48: 36/67 (53.7%)).

Conclusions

Favourable safety profile and disease control appeared to be maintained in patients with SLE in China for ≤6 years, consistent with previous belimumab studies.

Keywords: biological therapy, B-lymphocytes, cytokines, lupus erythematosus, systemic

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Belimumab is a recombinant, human immunoglobulin G1 lambda monoclonal antibody that binds soluble human B lymphocyte stimulator protein and inhibits its activity.

Double-blind, placebo-controlled trials report that belimumab reduces disease activity and new organ damage accrual and has a favourable safety and tolerability profile.

Long-term data on the safety and efficacy of belimumab are limited in the Chinese population.

What does this study add?

Belimumab therapy for up to 6 years in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in China was well tolerated with no new safety concerns identified.

There was also a continued efficacy benefit seen following long-term treatment with belimumab that should be viewed in the context of the limitations of an open-label safety study, where efficacy analyses were exploratory.

These findings are consistent with previous long-term belimumab studies.

How might this impact on clinical practice or further developments?

The results of the presented analyses support a positive benefit–risk profile of treatment with belimumab as an add-on to standard therapy in patients with active SLE in China.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, inflammatory autoimmune disease that commonly manifests with a range of clinical abnormalities, including multisystem microvascular inflammation with the generation of autoantibodies (particularly anti-nuclear antibodies).1 2 Patients with SLE have elevated levels of B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) protein, which promotes abnormal B cell activation and differentiation.3 4

B cells produce autoantibodies targeting nuclear components, such as anti-double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid (anti-dsDNA),5 which go on to cause irreversible organ damage in most patients with SLE.6

Clinical heterogeneity and racial differences affect SLE disease progression and prevalence.7 SLE is more prevalent and severe in non-Caucasian populations, such as those in China, than in Caucasian populations.8 9

In China, SLE affects 97.5–100 people per 100 000.10 Despite advances in the diagnosis and treatment of SLE, many patients still have progressive disease activity. Long-term use of standard SLE therapy is often associated with significant toxicity, thus, there remains an unmet need for therapeutic alternatives.6

Belimumab is a human immunoglobulin G1 lambda monoclonal antibody that binds to and inhibits the biological activity of BLyS.11 Intravenous (IV) belimumab is approved in Europe, the USA and Japan for treatment of patients ≥5 years of age with active autoantibody-positive SLE receiving standard therapy12–14 and was recently approved in China.15 16 Previous phase 3 studies demonstrated safety and efficacy of belimumab in patients with autoantibody-positive, active SLE.17 18 The long-term safety and efficacy of belimumab were demonstrated in two open-label (OL) continuation studies (BEL112233 and BEL112234) and supported by a pooled interim analysis of these two studies.19 20 The safety and efficacy of belimumab were also demonstrated in the phase 3 double-blind, placebo-controlled 52-week study (BLISS-NEA; BEL113750; NCT01345253) in patients with SLE from North East Asia (China, Japan and South Korea).16 Patients from Japan and South Korea who successfully completed the double-blind period of the BLISS-NEA study were eligible to participate in the long-term OL extension period (BEL114333; NCT01597622), in which the beneficial effects of belimumab were further demonstrated.21 However, there are limited data on the long-term safety and efficacy of belimumab in Chinese patients with SLE. This OL period of the BLISS-NEA study aimed to evaluate the long-term safety and tolerability and efficacy of belimumab treatment in patients with SLE in China.

Methods

Study design

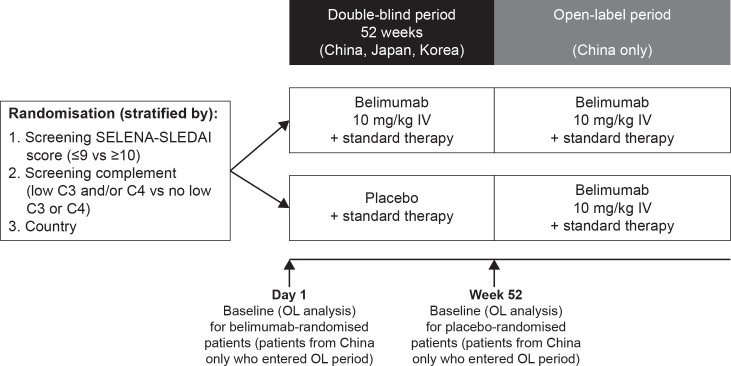

This study was an OL, multicentre period of the phase 3 BLISS-NEA study (GSK Study BEL113750; NCT01345253) conducted in 24 centres across China in patients with SLE. This OL study was similar in design to the previously published BEL114333 study.21 Eligible patients who completed the 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the BLISS-NEA study could choose to enter the OL period (figure 1). All enrolled patients received belimumab 10 mg/kg IV infused over 1 hour every 28 days, plus standard therapy, for up to 6 years, irrespective of their randomised treatment in the double-blind period in the BLISS-NEA study, and received their first OL belimumab dose 4 weeks (range 2–8 weeks) after the last dose in the double-blind period. Patients continued to receive belimumab unless specific stopping criteria occurred.21

Figure 1.

Study design.C, complement; IV, intravenous; OL, open-label; SELENA-SLEDAI, Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment SLE Disease Activity Index; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Blinding

All patients and study site personnel, with exception of the site pharmacist or designee, were blinded to belimumab treatment, biomarkers and pharmacodynamic laboratory results during the double-blind period of the BEL113750 study until the double-blind results were made public. In the OL period, all patients and the investigator were unblinded to belimumab treatment.

Patients

Eligible patients in China had completed the double-blind treatment period of the BLISS-NEA study up to week 48. Patients had to be on a stable SLE treatment regimen for ≥30 days prior to day 0 of the double-blind period of BLISS-NEA. The details of the SLE treatment regimen have been previously published.21

Patients requiring acute therapy for severe lupus kidney disease or active lupus nephritis within 90 days prior to day 0 were excluded from this study. Further key eligibility criteria and permissible and prohibited medications and non-drug remedies are listed in online supplemental methods. Full patient eligibility criteria have been previously published.16

rmdopen-2021-001669supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoint of this OL extension was safety, assessed by the incidence of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs) and AEs of special interest (AESI), physical examinations, change from baseline in proteinuria levels and immunogenicity throughout the study. Treatment–emergent AEs were defined as any AE that occurred after receipt of the first belimumab dose, that is, for patients randomised to placebo in the double-blind period, the first dose was at the start of the OL period and for patients randomised to belimumab in the double-blind period, the first dose was at the start of the double-blind period; figure 1). AEs were assessed at each infusion visit. Other safety endpoints were monitored at regular intervals until the 16-week follow-up visit (post-final belimumab dose). Changes from baseline in proteinuria levels were assessed at weeks 24 and 48 visits of each study year 4 weeks post-final belimumab dose (exit visit). This OL extension study was designed to have 48-week study years, and week 48 was the last assessment visit of each study year. Further information, including AEs coding, is found in online supplemental methods.

The key secondary efficacy endpoint was the observed proportion of SLE Responder Index (SRI)-4 (defined as a ≥4-point reduction from baseline in Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment version of the SLE Disease Activity Index (SELENA-SLEDAI), no worsening in Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA; <0.3-point increase from baseline) and no new British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) 1A/2B organ domain score responders, and it was assessed at weeks 24 and 48 of each study year and at exit visit.

Other secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of patients’ meeting each of the three SRI-4 response component criteria individually; median time to first severe SLE Flare Index (SFI) flare (definition of SFI flares is provided in online supplemental methods); proportion of patients experiencing SFI flare, BILAG 1A/2B flare (≥1 new 1A or ≥2 new 2B scores compared with baseline), and renal flare at any time post-first dose of belimumab; the cumulative number of days where prednisone dose was ≤7.5 mg/day and/or reduced by 50% from baseline.

Other efficacy endpoints were: change from baseline in SELENA-SLEDAI score and PGA score and shifts in prednisone dose. The above-listed efficacy endpoints were assessed at weeks 24 and 48 visits of each study year and at exit visit. Change from baseline in Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index (SDI) was also assessed, at week 48 annually and at exit visit.

Change from baseline in serum IgG, anti-dsDNA autoantibodies and complement (C3, C4) levels were also assessed. IgG levels were assessed at week 12, 24 and 48 visits in year 1, and at week 48 in additional years as well as at exit and 16-week follow-up visits. Anti-dsDNA and complement levels were assessed at weeks 24 and 48 of each study year and at exit visit.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculations were not performed as enrolment in this OL period was dependent on the number of patients in China who completed the double-blind period of BLISS-NEA study. Baseline was defined as the last available value prior to belimumab initiation: day 1 for patients randomised to belimumab in the double-blind period and week 52 for patients randomised to placebo in the double-blind period (figure 1). Analyses were descriptive, based on observed data, and summarised relative to baseline.

No follow-up data were collected post-study. All data summaries and analyses were performed using SAS software, V.9.3 or higher (SAS Institute).

Safety endpoints were assessed in the Safety population, which was defined as all enrolled patients who received at least one dose of belimumab during this OL period. AEs were summarised at any time after the first dose of belimumab and by year of belimumab treatment, starting from first belimumab dose (baseline). Efficacy endpoints were assessed in the safety population, excluding 25 patients from one site in China due to source data issues for disease assessments. Exit visits were slotted to the next scheduled visit for each efficacy endpoint.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design or implementation of the study, or the dissemination of its results.

Results

Patient disposition and baseline characteristics

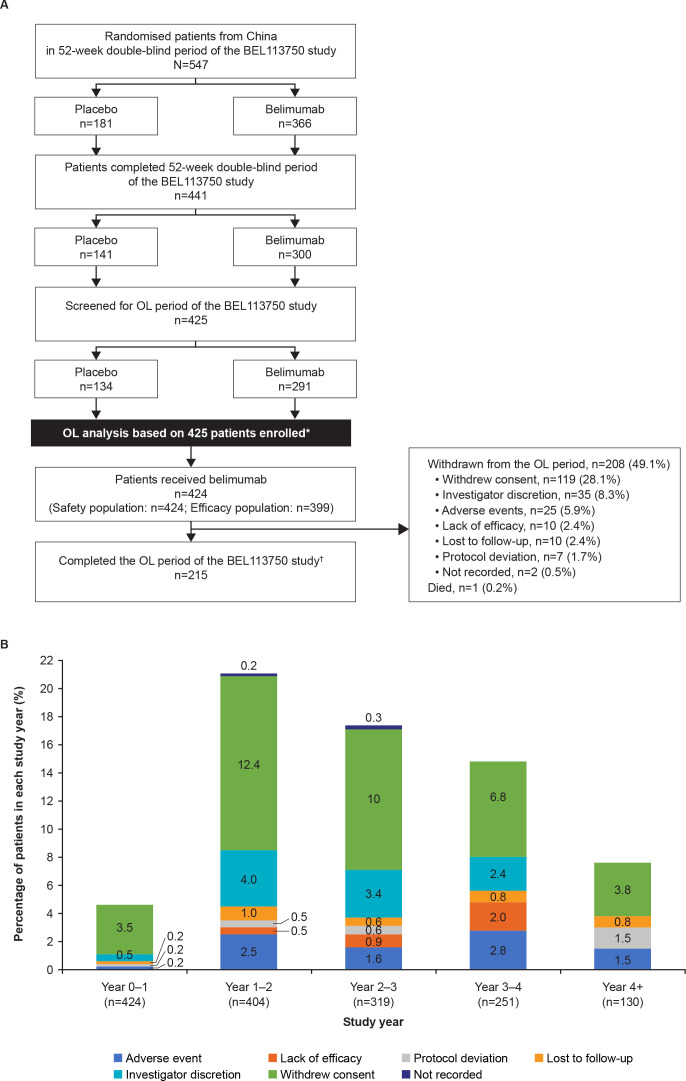

The first patient was enrolled into this OL period on 29 October 2013, and the last patient last visit was on 21 September 2018. A total of 77.7% (425/547) patients from China who were randomised in the double-blind period continued to the OL period of the BEL113750 study, 424/425 patients received OL belimumab and were included in the safety population and 399/424 were included in the efficacy population. Overall, 50.7% (215/424) patients completed the OL period, 49.1% (208/424) withdrew and one patient died (figure 2A). The most common reason for withdrawal from the study was withdrawal of consent (28.1%). The proportion of patients who withdrew from the OL period of the study did not exceed 25% for any given year interval (figure 2B), and there were no trends of clinical concern for any given withdrawal reason over time. Overall median (min, max) belimumab exposure was 1204 (56, 1932) days and cumulative belimumab-treated patient years on study were 1323.1.

Figure 2.

(A) Patient disposition and (B) withdrawals per study year (safety population; N=424).*One patient did not receive OL belimumab and was excluded from the safety population. The patient was withdrawn from the OL period due to an ongoing non-SAE that started during the double-blind period (considered by the investigator to be unrelated to study treatment).†Patients who entered the OL period were considered to have completed the OL period of the study if they transferred to another study or were still participating at the time of the sponsor decision to close/terminate the study. Year 4+ represents year 4–5 and year 5–6 of belimumab treatment.OL, open-label; SAE, serious adverse event.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics are presented in table 1. The mean (SD) baseline SELENA-SLEDAI score was 8.0 (4.1). Most patients (65.3%) had a baseline SELENA-SLEDAI score ≤9. Patients randomised to placebo in the double-blind period who subsequently entered in the OL period had lower mean SELENA-SLEDAI and PGA scores than patients randomised to belimumab (online supplemental table 1). In addition, a higher proportion of patients (56.7%) who were randomised to placebo in the double-blind period had no A or B BILAG domain involvement at baseline than patients randomised to belimumab (17.6%). Among patients randomised to belimumab in the double-blind period, the most frequently affected organ domains based on BILAG scoring at baseline were mucocutaneous (49.0%), renal (25.9%) and musculoskeletal (24.5%), whereas haematology (17.2%), renal (16.4%) and mucocutaneous (15.7%) involvements were most common at baseline among patients randomised to placebo in the double-blind period (online supplemental table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline clinical characteristics (safety population; N=424)

| Total OL population (N=424) | |

| Female, n (%) | 393 (92.7) |

| Mean age (SD), years | 31.9 (9.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (0.5) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 422 (99.5) |

| Mean BMI (SD), kg/m2 | 22.7 (3.8) |

| Mean SLE disease duration (SD), years | 6.0 (4.8) |

| BILAG organ domain involvement*, n (%) | |

| ≥1A or 2B | 137 (32.3) |

| ≥1A | 20 (4.7) |

| ≥1B | 292 (68.9) |

| No A or B | 127 (30.0) |

| BILAG organ system involvement (A or B scores), n (%) | |

| General | 14 (3.3) |

| Mucocutaneous | 163 (38.4) |

| Neurological | 0 (0) |

| Musculoskeletal | 74 (17.5) |

| Cardiovascular and respiratory | 1 (0.2) |

| Vasculitis | 34 (8.0) |

| Renal | 97 (22.9) |

| Haematology | 79 (18.6) |

| Mean SELENA-SLEDAI score (SD) | 8.0 (4.1) |

| SELENA-SLEDAI category | |

| ≤9 | 277 (65.3) |

| ≥10 | 147 (34.7) |

| SLE flare index, n (%) | |

| ≥1 Flare | 63 (14.9) |

| ≥1 Severe flare | 9 (2.1) |

| Mean PGA (SD) | 1.5 (0.5) |

| SDI score | |

| Mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.4) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 0 (0, 3) |

| ANA | |

| Positive (Index ≥0.80), n (%) | 424 (100.0) |

| Anti-dsDNA | |

| Positive (≥30 IU/mL), n (%) | 324 (76.4) |

| Complement level, n (%) | |

| Low C3 (<90 mg/dL) and/or low C4 (<10 mg/dL) | 278 (65.6) |

| No low C3 or C4 | 146 (34.4) |

| Mean proteinuria level (SD), g/24 hours | 0.8 (1.2) |

| Proteinuria category (g/24 hours), n (%) | |

| ≤0.5 | 247 (58.3) |

| >0.5 | 177 (41.7) |

| >0.5 to <1 | 57 (13.4) |

| 1 to <2 | 71 (16.7) |

| ≥2 | 49 (11.6) |

| Medication at baseline | |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 415 (97.9) |

| Mean daily prednisone† dose (SD), mg/day | 16.1 (9.9) |

| Antimalarials, n (%) | 328 (77.4) |

| Immunosuppressants/immunomodulatory agents, n (%) | 270 (63.7) |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 47 (11.1) |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 6 (1.4) |

| Traditional Chinese medication, n (%) | 66 (15.6) |

Note: Baseline was defined as the last available value prior to belimumab initiation: day 1 for patients randomised to belimumab in the double-blind period and week 52 for patients randomised to placebo in the double-blind period.

*Patients may have been counted in more than one category.

†Prednisone equivalent.

ANA, anti-nuclear antibodies; BILAG, British Isles Lupus Assessment Group; BMI, body mass index; C, complement; dsDNA, double stranded DNA; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OL, open-label; PGA, Physician’s Global Assessment; SD, standard deviation; SDI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index; SELENA-SLEDAI, Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment version of the SLE Disease Activity Index; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Concomitant SLE medications permitted during the study are shown in online supplemental table 2.

Safety

Overall, in the safety population, 84.7% (359/424) of patients experienced ≥1 treatment-emergent AE and most AEs were mild or moderate in severity; incidence decreased over time. The most frequent AEs were upper respiratory tract infection (35.4%) and viral upper respiratory tract infection (13.9%). The incidences of the most frequent AEs were generally stable or declined over time (table 2). Overall AE rate at any time post-first dose of belimumab was 165.1 events/100 patient-years and it decreased over time (table 3).

Table 2.

Overall summary of treatment-emergent AE* incidence by year interval (safety population; N=424)

| Number (%) of patients | ||||||

| Any time post-first dose of belimumab† | Year 0–1 | Years 1–2 | Years 2–3 | Years 3–4 | Year 4+‡ | |

| (N=424) | (n=424) | (n=404) | (n=319) | (n=251) | (n=130) | |

| AE | 359 (84.7) | 277 (65.3) | 236 (58.4) | 176 (55.2) | 122 (48.6) | 49 (37.7) |

| AE preferred terms occurring in ≥5% of patients: | ||||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 150 (35.4) | 70 (16.5) | 78 (19.3) | 41 (12.9) | 35 (13.9) | 12 (9.2) |

| Viral upper respiratory tract infection | 59 (13.9) | 23 (5.4) | 20 (5.0) | 21 (6.6) | 5 (2.0) | 4 (3.1) |

| Urinary tract infection | 41 (9.7) | 23 (5.4) | 15 (3.7) | 7 (2.2) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) |

| Herpes zoster | 40 (9.4) | 19 (4.5) | 9 (2.2) | 2 (0.6) | 8 (3.2) | 2 (1.5) |

| Fever | 37 (8.7) | 17 (4.0) | 11 (2.7) | 5 (1.6) | 4 (1.6) | 2 (1.5) |

| Bacterial upper respiratory tract infection | 37 (8.7) | 15 (3.5) | 11 (2.7) | 15 (4.7) | 7 (2.8) | 3 (2.3) |

| Cough | 30 (7.1) | 14 (3.3) | 6 (1.5) | 9 (2.8) | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| Diarrhoea | 28 (6.6) | 17 (4.0) | 9 (2.2) | 3 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| Hypokalaemia | 24 (5.7) | 14 (3.3) | 13 (3.2) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.8) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 24 (5.7) | 14 (3.3) | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.6) | 3 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) |

| Bacterial urinary tract infection | 23 (5.4) | 18 (4.2) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (2.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 22 (5.2) | 9 (2.1) | 4 (1.0) | 6 (1.9) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.8) |

| Treatment-related AE | 181 (42.7) | 93 (21.9) | 94 (23.3) | 80 (25.1) | 52 (20.7) | 14 (10.8) |

| SAE | 96 (22.6) | 23 (5.4) | 36 (8.9) | 25 (7.8) | 20 (8.0) | 4 (3.1) |

| SAE preferred terms occurring in >2 (0.5%) of patients: | ||||||

| Lupus nephritis§ | 12 (2.8) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.2) | 5 (1.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Herpes zoster | 6 (1.4) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) |

| Osteonecrosis | 6 (1.4) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 4 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.2) | 0 |

| Severe AE¶ | 35 (8.3) | 12 (2.8) | 9 (2.2) | 8 (2.5) | 7 (2.8) | 1 (0.8) |

| Severe AE preferred terms occurring in ≥2 (0.5%) of patients: | ||||||

| Osteonecrosis | 6 (1.4) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| Lupus nephritis§ | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Granulocytopaenia | 2 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Necrosis ischaemic | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AE resulting in study drug discontinuation | 26 (6.1) | 3 (0.7) | 9 (2.2) | 6 (1.9) | 6 (2.4) | 2 (1.5) |

| Deaths** | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 |

*Treatment-emergent AEs are defined as AEs that started on or after first belimumab dose.

†Post-first belimumab dose (baseline) includes time on study up to the 16-week follow-up visit post-last dose. Data from year 0 to a patient’s exit visit (4 weeks post-last dose) are shown by years of study participation.

‡Year 4+ represents year 4–5 and year 5–6 of belimumab treatment.

§Active nephritis requiring acute therapy not permitted by protocol (eg, IV cyclophosphamide).

¶For severe AEs, events listed as life-threatening were included in the count.

**Accidental fall unrelated to study treatment.

AE, adverse event; IV, intravenous; SAE, serious AE.

Table 3.

Event rate of treatment-emergent AEs (safety population; N=424)

| Number (rate per 100 patient-years) of events* | ||||||

| Any time post-first dose of belimumab† | Year 0–1 | Years 1–2 | Years 2–3 | Years 3–4 | Year 4+‡ | |

| Patient-years=1384 | Patient-years=415 | Patient-years=364 | Patient-years=282 | Patient-years=197 | Patient-years=65 | |

| AE | 2285 (165.1) | 863 (207.9) | 566 (155.7) | 439 (155.5) | 260 (132.1) | 86 (131.6) |

| Treatment-related AE | 659 (47.6) | 202 (48.7) | 170 (46.8) | 167 (59.2) | 88 (44.7) | 21 (32.1) |

| SAE | 135 (9.8) | 28 (6.7) | 41 (11.3) | 31 (11.0) | 23 (11.7) | 6 (9.2) |

| Serious infections and infestations | 25 (1.8) | 4 (1.0) | 6 (1.7) | 3 (1.1) | 9 (4.6) | 1 (1.5) |

| Severe AE | 47 (3.4) | 13 (3.1) | 11 (3.0) | 11 (3.9) | 9 (4.6) | 2 (3.1) |

| AEs resulting in study discontinuation | 29 (2.1) | 3 (0.7) | 11 (3.0) | 6 (2.1) | 6 (3.0) | 3 (4.6) |

| AESI | ||||||

| Malignant neoplasms§¶ | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Any post-infusion systemic reactions**†† | 21 (1.5) | 11 (2.7) | 5 (1.4) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| All infections of special interests§‡‡ | 50 (3.6) | 21 (5.1) | 14 (3.9) | 3 (1.1) | 9 (4.6) | 2 (3.1) |

| Serious | 8 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 3 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) |

| All opportunistic infections§§ | 15 (1.1) | 8 (1.9) | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Serious | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Active TB§ | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Herpes zoster¶¶ | 42 (3.0) | 19 (4.6) | 10 (2.8) | 2 (0.7) | 8 (4.1) | 2 (3.1) |

| Serious | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 2 (1.0) | 1 (1.5) |

| Recurrent opportunistic | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Disseminated opportunistic | 8 (0.6) | 6 (1.4) | 2 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sepsis§ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression*** | 14 (1.0) | 3 (0.7) | 8 (2.2) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.0) | 0 |

| Deaths | 1 (<0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 |

*Each column shows the number of reported AEs for that year and the rate of events per 100 patient-years.

†Post-first belimumab dose (baseline) includes time on study up to the 16 week follow-up visit post-last dose. Data from year 0 to a patient’s exit visit (4 weeks post-last dose) are shown by years of study participation.

‡Year 4+ represents years 4–5 and years 5–6 of belimumab treatment.

§Per Custom MedDRA query (CMQ, version 21.1).

¶No skin malignancies reported.

**No serious post-infusion systemic reactions reported.

††Per anaphylactic reaction CMQ broad search.

‡‡All infections of special interest are limited to opportunistic infections, active TB, herpes zoster and sepsis.

§§Per sponsor adjudication.

¶¶Herpes zoster events that were recurrent or disseminated are also counted under ‘All opportunistic infections’.

***Per MedDRA preferred term.

AE, adverse event; AESI, AE of special interest; CMQ, custom MedDRA query; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; SAE, serious AE; TB, tuberculosis.

Serious treatment-emergent AEs were reported in 22.6% (96/424) of patients, with infections and infestations being the most frequently reported by system organ class (SOC; 5.0%, data not shown). The most frequently reported SAEs by preferred term were lupus nephritis (2.8%), herpes zoster (1.4%) and osteonecrosis (1.4%) (table 2). The highest SAE event rate by SOC was infections and infestations (1.8 events/100 patient-years) (table 3).

Overall, 42.7% (181/424) of patients experienced a treatment-emergent AE considered by the investigator to be at least possibly treatment related (table 2). Treatment-related AEs with >5% incidence at any time post-first dose of belimumab were upper respiratory tract infection (14.9%) and bacterial and viral upper respiratory tract infections (5.7% each) (data not shown). There was no clear increase in the incidence of treatment-related AEs over time.

In total, 6.1% of patients had an AE that resulted in treatment discontinuation/study withdrawal (2.1 events/100 patient-years). One (0.2%) death was reported during year 2–3 due to an accidental fall (considered by the investigator to be unrelated to study treatment).

AESI rates per 100 patient-years are presented in table 3. One malignancy occurred in year 0–1 (papillary thyroid cancer) and one in year 3–4 (vaginal cancer). There were no serious anaphylaxis/hypersensitivity reactions and no clear increase was observed in the rate of infections up to year 4+ (overall rate for all infections of special interest was 3.6 events/100 patient-years). The rate of herpes zoster infection at any time post-first dose of belimumab was 3.0 events/100 patient-years, of which 0.4 events/100 patient-years were serious events. There were no completed suicides or suicide attempts and no reports of serious depression.

No trends of clinical concern were observed over time with regards to the incidence of grades 3 or 4 in haematology parameters, clinical chemistry, urinalysis values and IgG.

Among patients with proteinuria >0.5 g/24 hours at baseline (n=164), the mean (SD) baseline value was 1.75 (1.38) g/24 hours. In these patients, the mean (SD) per cent change in proteinuria from baseline was −42.78% (102.57) at year 5, week 48 (n=36) (online supplemental figure 1).

One patient was classified with a transient positive result for antidrug antibodies (ADA) at any time post-first dose of belimumab, as a result of a single positive result at the 16-week follow-up visit, which was confirmed as negative at the 6-month follow-up visit.

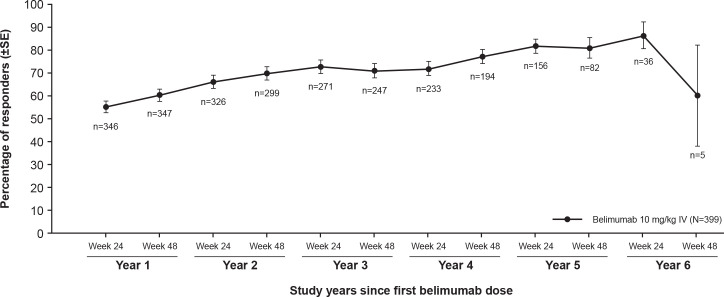

Efficacy results

During belimumab treatment, the proportion of SRI-4 responders increased from 54.9% (190/346) at year 1, week 24 to 80.5% (66/82) at year 5, week 48 (figure 3). Similarly, the proportion of patients with a ≥4-point reduction from baseline in SELENA-SLEDAI score increased from 55.9% (195/349) in year 1, week 24 to 81.9% (68/83) in year 5, week 48. The proportion of patients with no worsening in PGA (range of 92.8%–100%) and no new BILAG 1A/2B domain scores (range of 96.7%–99.4%) remained stable over time.

Figure 3.

SRI-4 response rate during belimumab treatment over time (efficacy population; N=399).Note: Baseline was defined as the last available value prior to belimumab initiation: day 1 for patients randomised to belimumab in the double-blind period and week 52 for patients randomised to placebo in the double-blind period. The observed proportion of SRI-4 responders was assessed at weeks 24 and 48 visits of each study year. The SRI-4 was defined as a ≥4-point reduction from baseline in SELENA-SLEDAI, no worsening in PGA (<0.3-point increase from baseline), and no new BILAG 1A/2B organ domain scores.BILAG, British Isles Lupus Assessment Group; IV, intravenous; PGA, Physician’s Global Assessment; SELENA-SLEDAI, Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment version of the SLE Disease Activity Index; SRI-4, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Responder Index≥4-point reduction in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index.

Only 13.9% (55/396) patients experienced a severe SFI flare post-first dose of belimumab (68 severe flares, 5.4 events/100 patient-years). For patients who had a severe SFI flare post-first dose of belimumab, the median (IQR) time to first severe flare post-first dose of belimumab was 510 (337.0 to 961.0) days. Overall, 64.6% (256/396) patients experienced any SFI flare post-first dose of belimumab (49.1 events/100 patient-years) during belimumab treatment. For the total efficacy population, the median (IQR) time to first SFI flare was 377 (139 to 1686) days. Only 16.4% (65/396) of patients experienced ≥1 new BILAG 1A/2B flare and 10.9% (43/396) had ≥1 new BILAG A flare post-first dose of belimumab. A total of 25.8% (102/396) of patients experienced a renal flare post-first dose of belimumab.

A total of 335 patients received an average daily prednisone-equivalent dose >7.5 mg/day at the baseline visit. Among these patients, the number of patients with a dose reduction to ≤7.5 mg/day appeared to increase over time, with 30/333 (9.0%) patients reducing their prednisone dose to ≤7.5 mg/day at year 1, week 24 and 36/67 (53.7%) at year 5, week 48. For patients with an average daily prednisone-equivalent dose ≤7.5 mg/day (n=64) at baseline, 9/64 (14.1%) patients at year 1, week 24, and 5/17 (29.4%) patients at year 5, week 48, showed prednisone-equivalent dose elevation to >7.5 mg/day. These results should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size.

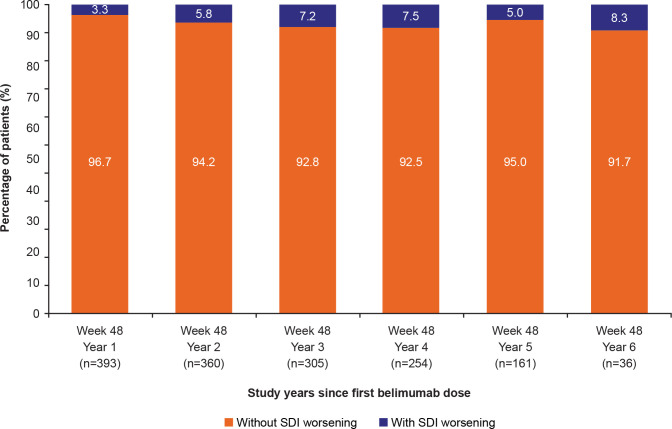

Other efficacy endpoints included change from baseline in SELENA-SLEDAI and PGA scores, which decreased numerically over time (online supplemental figure 2). Over 90% of patients at any visit had no change in SDI score during belimumab treatment (figure 4), suggesting low organ damage accrual.

Figure 4.

Percentage of patients with and without SDI worsening (change >0) from baseline at week 48 of each study year (efficacy population; N=399).Note: Observed case data are presented. The index is cumulative, once an item had been scored, it continued to be scored at all subsequent visits. Baseline was defined as the last available value prior to belimumab initiation: day 1 for patients randomised to belimumab in the double-blind period and week 52 for patients randomised to placebo in the double-blind period.SDI, Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index.

Biomarkers

The IgG median per cent change from baseline decreased only slightly over time (online supplemental figure 3A). The median anti-dsDNA per cent change from baseline also decreased (online supplemental figure 3B). The median per cent change in C3 and C4 levels increased and generally remained at a raised level above baseline during belimumab treatment (online supplemental figure 3C).

Discussion

This OL period of a phase 3 long-term study in patients with SLE in China demonstrated that IV belimumab is well tolerated as add-on to standard therapy, with no apparent increase in the incidence of AEs or SAEs across 6 years of treatment, including infections and malignancies. The safety profile observed from the first dose of belimumab reported herein is consistent with that seen in the overall population of the double-blind period of BLISS-NEA study as well as in previous belimumab studies in patients with SLE across the USA and Europe.16–18 22 23 The frequency of AEs was generally lower than that of the phase 2 and phase 3 continuation studies in patients with active SLE.19 23 24

The rate of serious infections at any time post-first dose of belimumab was low (1.8 events/100 patient-years), which is lower compared with the results reported in previous belimumab studies (≤5.5 events/100 patient-years).22 23

The overall rate of malignant neoplasms, excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, was 0.1 events/100 patient-years, which was comparable to the rate of 0.2 events/100 patient-years reported in previous phase 3 continuation studies.22–24 The overall rate of depression was low (1.0 events/100 patient-years), and no serious depression or suicide/self-injury were reported. There was no apparent increase in the number of deaths in patients receiving belimumab; there was one death (accidental fall, incidence 0.2%), which was lower than the 0.7%–2.7% incidence reported in previous long-term belimumab continuation studies.19 22–24

Among patients with baseline proteinuria >0.5 g/24 hours, there appeared to be a decrease in proteinuria during belimumab treatment. One patient had a transient positive result for ADA at the 16-week follow-up visit confirmed as negative at the 6-month follow-up visit. The low rate of immunogenicity observed is consistent with immunogenicity results in the double-blind period of BLISS-NEA and other belimumab studies.16 22 23

Consistent with the double-blind period of BLISS-NEA and other pivotal phase 3 studies of IV belimumab treatment,16 22 23 the numerical increase in the proportion of SRI-4 responders, and the reduction in corticosteroids over time coupled with a low rate of severe flare suggest continued efficacy benefit of belimumab treatment. This is further supported by the observation that the progression in organ damage, as measured by SDI, was low, with over 90% of patients experiencing no change in SDI score at any time during belimumab treatment.

Favourable changes were observed in IgG, anti-dsDNA, C3 and C4 levels over time. The increase in complement and decrease in autoantibody levels observed are important since these biomarkers have been associated with increased risk of renal disease and severe SLE flares.25

Limitations to interpretation of the results include the small sample size, particularly at later study visits and absence of a placebo control group, meaning that treatment comparisons could not be made. Additionally, as eligible patients had completed the double-blind period, patients enrolled in the OL period were self-selecting, and potentially more likely to respond well to treatment over time. The efficacy results presented here are exploratory and based on observed data with no imputation analyses for withdrawal, which may bias the findings. Finally, the baseline definition used for the OL analysis differed according to the randomised treatment groups in the double-blind period. This may have also impacted the results presented here. Despite these limitations, this OL analysis provides valuable information about the effect of belimumab in patients with active SLE in China.

In conclusion, belimumab therapy for up to 6 years in patients with SLE in China was well tolerated with no new safety concerns identified, which is consistent with the previous long term belimumab studies. These findings, along with a suggested continued efficacy benefit, support the positive benefit–risk profile of treatment with belimumab as an add-on to standard therapy in patients with active SLE in China.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participating patients and their families, clinicians and study investigators.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception or design: DB, MC, DAR. Acquisition of data: FZ, JZ, YL, GW, MW, YS, JG, XL. Data analysis or interpretation: DB, MC, PC, KD, RK, JL, PM, DAR. DAR accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: This study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK study 113750). Medical writing support was provided by Olga Conn, PhD, of Fishawack Indicia Ltd, UK and funded by GSK.

Competing interests: FZ is a Principal Investigator at GSK. JZ, YL, GW, MW, YS, JG and XL have no conflict of interest to declare. DB, PC, KD, JL, PM and DAR are employees of GSK and hold stocks and shares in the company. MC and RK were employees of GSK and held stocks and shares in the company at the time of study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Author note: Myron Chu and Regina Kurrasch were employed at Immunoinflammation, GlaxoSmithKline, Collegeville, PA, USA, at the time of the study.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Anonymised individual patient data and study documents can be requested for further research from: https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by local institutional review boards and/or ethics committees and conducted in accordance with the International Council on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, Good Clinical Practice ethical principles, and the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were not re-consented upon enrolling into this OL period. This study involves human participants and was approved by Qilu Hospital of Shandong University-Jinan-China (2013)临审第(104)号 approval number: 2013104Guangdong General Hospital-Guangzhou-China 粤医伦理(2012) 34-2号Xijing Hospital.-Xian-China 第20130814-4号Peking Union Medical College Hospital-Beijing-China 13088China-Japan Friendship Hospital-Beijing-China 2013-56Peking University People’s Hospital-Beijing-China (2012)伦理药临字第(36)号修正1The 2nd Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical Univ-harbin-China 2013-药(器)-031Renji hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong Un-Shanghai-China 仁济伦审[2012]62b号The 1st Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical Univ-Harbin-China 哈医一伦审编号201335Changhai Hospital of Shanghai-Shanghai-China CHEC2013-188Xiangya Hospital Central-south University-Changsha-China 伦审第(20128048-2) West China Hospital, Sichuan University-Chengdu-China NAAnhui Provincial Hospital-Hefei-China 伦审2013第38Jiangsu Province Hospital-Nanjing-China 2012-MD-124.A11st Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University-Suzhou-China (2013) 伦快审药第 (236) 号2nd Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University-Hangzhou-China (2013) 伦快审药第 (064) 号3rd Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University-Guangzhou-China 中大附三医伦[2013]1-5号修正12nd Affiliated Hospital of GuangZhou Medical Univ.-Guangzhou-China (2013) 临审第 (39) 号Ruijin Hosp affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ-Shanghai-China (2012) 伦审第 (62) -2号The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical-Kunming-China (2013) 伦审字 (31) 号Southwest Hospital,Third Military Med Uni-Chongqing-China 2013年伦审药第 (29) 号Xiangya 2nd Hospital, Central South University-Changsha-China (2013) 伦审【药】第 (90) 号Shanghai Changzheng Hospital-Shanghai-China 2013 (伦审) -18-01Tianjin Medical University General Hospital-Tianjin-China IRB2103-047-01 Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Dema B, Charles N. Autoantibodies in SLE: specificities, isotypes and receptors. Antibodies 2016;5. doi: 10.3390/antib5010002. [Epub ahead of print: 04 Jan 2016]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cojocaru M, Cojocaru IM, Silosi I, et al. Manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Maedica 2011;6:330–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petri M, Stohl W, Chatham W, et al. Association of plasma B lymphocyte stimulator levels and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2453–9. 10.1002/art.23678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Roschke V, Baker KP, et al. Cutting edge: a role for B lymphocyte stimulator in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol 2001;166:6–10. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karrar S, Cunninghame Graham DS. Abnormal B cell development in systemic lupus erythematosus: what the genetics tell us. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70:496–507. 10.1002/art.40396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce IN, O'Keeffe AG, Farewell V, et al. Factors associated with damage accrual in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: results from the systemic lupus international collaborating clinics (SLICC) inception cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1706–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y-F, Lau YL, Yang W. Genetic studies on systemic lupus erythematosus in East Asia point to population differences in disease susceptibility. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2019;181:262–8. 10.1002/ajmg.c.31696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González LA, Toloza SMA, McGwin G, et al. Ethnicity in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): its influence on susceptibility and outcomes. Lupus 2013;22:1214–24. 10.1177/0961203313502571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus 2006;15:308–18. 10.1191/0961203306lu2305xx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z, Wang Y, Zhu R, et al. Long-Term survival and death causes of systemic lupus erythematosus in China: a systemic review of observational studies. Medicine 2015;94:e794. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker KP, Edwards BM, Main SH, et al. Generation and characterization of LymphoStat-B, a human monoclonal antibody that antagonizes the bioactivities of B lymphocyte stimulator. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:3253–65. 10.1002/art.11299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.GSK . Prescribing information, 2019. Available: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/125370s064,761043s007lbl.pdf [Accessed Jan 2020].

- 13.GSK . Benlysta summary of product characteristics. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/benlysta-epar-product-information_en.pdf [Accessed Mar 2020].

- 14.PMDA . Benlysta report on deliberation results. Available: https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000233737.pdf [Accessed Mar 2020].

- 15.GSK . Benlysta, the world’s first biologic therapy for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), now approved in mainland China, 2019. Available: https://www.gsk-china.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/2019/benlysta-the-world-s-first-biologic-therapy-for-the-treatment-of-systemic-lupus-erythematosus-sle-now-approved-in-mainland-china/ [Accessed Feb 2020].

- 16.Zhang F, Bae S-C, Bass D, et al. A pivotal phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled study of belimumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus located in China, Japan and South Korea. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:355–63. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3918–30. 10.1002/art.30613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navarra SV, Guzmán RM, Gallacher AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;377:721–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61354-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furie RA, Wallace DJ, Aranow C, et al. Long-Term safety and efficacy of belimumab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a continuation of a Seventy-Six-Week phase III parent study in the United States. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70:868–77. 10.1002/art.40439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruce IN, Urowitz M, van Vollenhoven R, et al. Long-Term organ damage accrual and safety in patients with SLE treated with belimumab plus standard of care. Lupus 2016;25:699–709. 10.1177/0961203315625119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka Y, Bae S-C, Bass D, et al. Long-Term open-label continuation study of the safety and efficacy of belimumab for up to 7 years in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus from Japan and South Korea. RMD Open 2021;7:e001629. 10.1136/rmdopen-2021-001629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace DJ, Ginzler EM, Merrill JT, et al. Safety and efficacy of belimumab plus standard therapy for up to thirteen years in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1125–34. 10.1002/art.40861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ginzler EM, Wallace DJ, Merrill JT, et al. Disease control and safety of belimumab plus standard therapy over 7 years in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2014;41:300–9. 10.3899/jrheum.121368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Vollenhoven RF, Navarra SV, Levy RA, et al. Long-Term safety and limited organ damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus treated with belimumab: a phase III study extension. Rheumatology 2020;59:281–91. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giles BM, Boackle SA. Linking complement and anti-dsDNA antibodies in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Res 2013;55:10–21. 10.1007/s12026-012-8345-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2021-001669supp001.pdf (1.6MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. Anonymised individual patient data and study documents can be requested for further research from: https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/.