Abstract

To assess the potential efficacy of evernimicin (SCH 27899) against serious enterococcal infections, we used a rat model of aortic valve endocarditis established with either a vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecalis or a vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium strain. Animals infected with either one of the test strains were assigned to receive no treatment (controls) or 5-day therapy with one of the following regimens: evernimicin 60-mg/kg of body weight intravenous (i.v.) bolus once daily, 60-mg/kg i.v. bolus twice daily (b.i.d.), 60 mg/kg/day i.v. by continuous infusion, or 120 mg/kg/day i.v. by continuous infusion. These regimens were compared with vancomycin at 150 mg/kg/day. In animals infected with E. faecalis, evernimicin at 120 mg/kg/day by continuous infusion significantly reduced bacterial counts in vegetations (final density, 5.75 ± 3.38 log10 CFU/g) compared with controls (8.51 ± 1.11 log10 CFU/g). In animals infected with 0.5 ml of an 8 × 107-CFU/ml inoculum of the vancomycin-resistant E. faecium, both 60-mg/kg bolus once a day and b.i.d. dose regimens of evernimicin were very effective (viable counts, 3.45 ± 1.44 and 3.81 ± 1.98 log10 CFU/g, respectively). Vancomycin was unexpectedly active against infections induced with that inoculum. In animals infected with a 109-CFU/ml inoculum of the vancomycin-resistant E. faecium, the evernimicin 60-mg/kg i.v. bolus b.i.d. reduced viable counts in vegetations compared with controls (6.27 ± 1.63 versus 8.34 ± 0.91 log10 CFU/g; P < 0.05), whereas vancomycin was ineffective. Although resistant colonies could be selected in vitro, we were not able to identify evernimicin-resistant clones from cardiac vegetations. An unexplained observation from these experiments was the great variability in final bacterial densities within cardiac vegetations from animals in each of the evernimicin treatment groups.

Optimal therapy for serious infections caused by multiply antibiotic-resistant strains of enterococci has not been determined, and there is an important need for new therapeutic options for infections caused by these organisms. Evernimicin (SCH 27899; Ziracin), a novel oligosaccharide antibiotic, belongs to the everninomicin family of antimicrobial agents, which is produced from Micromonospora carbonacea var. africana (13). The antimicrobial activity of evernimicin results from interference with protein synthesis (T. A. Black, W. Zhao, K. J. Shaw, and R. S. Hare, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. C-106, p. 99, 1998). In vitro studies have shown that this compound is active against a broad range of gram-positive bacterial species, including vancomycin-resistant strains of enterococci (6, 12). Like vancomycin, evernimicin exerts a primarily bacteriostatic effect against enterococci (12), with an in vitro postantibiotic effect against strains of Enterococcus faecalis of 2.6 h (6). In vivo single-dose studies have demonstrated that evernimicin is active against vancomycin-susceptible and -resistant E. faecalis in a murine peritonitis model, with a potency similar to that of vancomycin against susceptible strains but approximately 10-fold higher than that of vancomycin against vancomycin-resistant strains (F. Meuzel, C. Norris, M. Michalsky, E. Corcoran, E. L. Moss, A. F. Cacciapuoti, D. Loebenberg, R. S. Hare, and G. H. Miller, Abstr. 37th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. B-98, p. 44, 1997). Evernimicin has been administered to human volunteers (C. R. Banfield, P. Glue, M. B. Affrime, B. F. Flannery, S. Pai, S. Menon, V. Batra, and P. Rudewicz, Abstr. 37th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. A-114, p. 23, 1997), and phase II clinical studies have shown the agent to have some activity in the treatment of pneumococcal pneumonia (J. M. L. Tsitsi, A. D. Calver, B. Luke, J.-J. Garaud, P. Grint, J. Gupte, and J. C. Wherry, Abstr. 38th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. L-109, p. 580, 1998). These data suggest that evernimicin could be evaluated for the treatment of enterococcal infections, especially those caused by multidrug-resistant isolates. Therefore, we conducted the present study in order to evaluate the efficacy of this compound against vancomycin-susceptible and -resistant strains of enterococci in a rat model of experimental endocarditis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Test organisms.

Two strains of enterococci were examined in the present study. E. faecalis 1310 was a clinical blood culture isolate susceptible to ampicillin and vancomycin (MICs = 1 μg/ml). The second strain, Enterococcus faecium A1221, was a laboratory transconjugant derived from the mating of a naturally penicillin-susceptible isolate with E. faecium 228 (vanA). The MICs of vancomycin and teicoplanin against E. faecium A1221 were 128 and 64 μg/ml, respectively. This strain was used in preference to a more typically penicillin-resistant clinical isolate of vancomycin-resistant E. faecium for laboratory safety.

Antimicrobial agents.

The evernimicin preparation was provided by Schering-Plough Research Institute (Kenilworth, N.J.). A solution which contained only excipients but no active drug (termed placebo SCH 27899) was used as a diluent and line-flushing solution. The clinical preparation of vancomycin for intravenous (i.v.) use was obtained from Eli Lilly & Co. (Indianapolis, Ind.).

In vitro studies.

The susceptibility of test strains to evernimicin was determined by (i) agar dilution on Mueller-Hinton II agar (Becton Dickinson, Cockeysville, Md.), (ii) broth macrodilution in Mueller-Hinton II broth, (iii) Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) on Mueller-Hinton II agar and on brain heart infusion (BHI) agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and (iv) the broth microdilution method in BHI broth (7). To assess the effect of different inocula on the activity of the agent, microdilution MICs were also determined at inocula of approximately 107 and 103 CFU/ml. The influence of serum on drug activity was examined by the microdilution method in BHI broth with 50% pooled rat serum. Minimal bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) at the 99.9% killing level were determined by the method of Pearson et al. (8). Bactericidal activity was also evaluated in BHI broth (with or without 50% rat serum) by time-kill methods (5). The final concentrations of evernimicin used in these studies were 2, 20, and 200 μg/ml, which included serum levels achieved with the dosage regimens used in this investigation.

To evaluate the possibility of emergence of resistance to evernimicin in vitro, each strain was serially streaked onto BHI agar plates containing doubling concentrations of the antibiotic. Specifically, colonies growing on antibiotic-containing plates after 24 or 48 h of incubation were suspended in BHI broth to a 0.5 McFarland standard, and 0.1 ml of the suspension was transferred onto plates with a two-fold-higher concentration up to 8 μg/ml. At that point, the MIC against these colonies was determined. To test the stability of resistance in the absence of drug, resistant organisms were serially subcultured on antibiotic-free plates for 2 weeks and the MIC was retested. To determine the frequency of spontaneous resistance to evernimicin, inocula of approximately 109 CFU of each of the test strains/ml were plated on BHI agar containing the antibiotic at eight times the MIC. Colonies emerging after 72 h of incubation at 35°C were subjected to repeat MIC testing. The frequency of spontaneous resistance was calculated as the ratio of the number of resistant cells to the number of cells inoculated.

In vivo studies. (i) Creation and treatment of experimental endocarditis.

Infective aortic valve endocarditis was established in male Sprague-Dawley rats by the technique of Santoro and Levison (10) with modifications previously described (11). A polyethylene catheter (PE10; inside and outside diameters, 0.28 and 0.61 mm, respectively; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.) was inserted via the right carotid artery through the aortic valve. Twenty minutes after catheterization, each rat was inoculated with 0.5 ml of a preparation containing approximately 5 × 107 CFU of E. faecalis 1310/ml or 8 × 107 or 1 × 109 CFU of E. faecium A1221/ml. After inoculation, the catheter was sealed and left in place throughout the experiment. Treatment was started 24 h after bacterial challenge. Antibiotics were delivered i.v. via an indwelling central venous catheter (silicone tubing; Baxter Healthcare Corp., Deerfield, Ill.) inserted through the external jugular vein into the superior vena cava. The distal portion of the catheter was connected to a programmable device (Pump 22; Harvard Apparatus) through a swivel.

(ii) Study groups.

Animals infected with either of the two test organisms were assigned to the following treatment groups. (i) Evernimicin, 60-mg bolus/kg of body weight i.v. once daily (q.d.). (ii) Evernimicin, 60-mg/kg bolus i.v. injection twice daily (b.i.d.). In these two sets of experiments, antibiotic injection was followed by i.v. bolus injection of 0.6 ml of placebo SCH 27899 to flush the catheter to prevent precipitation of the antibiotic. Thereafter, the lines were kept open by infusion of 0.3 ml of 5% dextrose in water per h. (iii) Evernimicin, 60 mg/kg/day by continuous infusion. (iv) Evernimicin, 120 mg/kg/day by continuous infusion. In the latter two sets of experiments, the antibiotic solutions were delivered at a rate of 0.3 ml/h. (v) Vancomycin, 150 mg/kg/day in saline by continuous infusion. (vi) Untreated (control) animals were observed for the duration of the experiment and sacrificed at the same time as the treated animals. The above-mentioned doses of evernimicin were chosen to achieve concentrations in rats comparable to those achievable in humans (Baufield et al., 37th ICAAC). Therapy was administered for 5 days.

(iii) Monitoring of therapy and outcome.

On day 4 of treatment, serum antibiotic concentrations were determined for several rats of each group. Blood was drawn from the retro-orbital sinus 15 min after the bolus injection of evernimicin (peaks) and just prior to the next injection (troughs) or during continuous infusion of evernimicin or vancomycin. Blood antibiotic levels were also determined in a few rats at the time of sacrifice. The concentrations of antimicrobial agents were measured by an agar well diffusion bioassay technique (9) using Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 (Difco) as the indicator organism. Standard curves were constructed with known concentrations of antibiotics diluted in sterile pooled rat serum. The limit of detection for the trough levels of evernimicin was 0.78 μg/ml.

The animals were sacrificed 3 h after discontinuation of vancomycin or 20 h after the last dose of evernimicin (based on a reported elimination half-life in rats of approximately 2 h [P. Krieter, M. Thonoor, M. Wirth, S. Gupta, J. Patrick, and M. N. Cayen, Abstr. 37th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. A-112, p. 23, 1997]) to allow washout of antibiotics from the serum. At necropsy, correct catheter position across the aortic valve was ascertained, and only those animals with correct placement were evaluated in the study. Cardiac vegetations were aseptically excised, weighed, homogenized, and serially diluted in saline. A volume of 25 μl of each dilution of the homogenate was plated on sheep blood agar plates in duplicate and on enterococcosel agar (Becton Dickinson) plates, and the results from all three plates were averaged to determine colony counts. Colonies were counted after 24 h of incubation at 35°C, and the results were expressed as log10 CFU per gram of vegetation. This technique permitted the detection of ≥2 log10 CFU/g. Animals that did not survive the 5 days of the experiment were included in the statistical analysis only if they had received treatment for at least 4 days.

To evaluate the emergence of evernimicin-resistant organisms among those persisting in cardiac vegetations, 0.1 ml of the homogenates from several infected animals was plated on agar containing 2, 4, 8, and 16 times the MIC of the test strains. Randomly selected colonies growing from colony count plates were also retested for susceptibility to evernimicin using the broth microdilution technique.

Statistical analysis.

The chi-square test with the Yates correction was used to evaluate the significance of mortality differences between groups. The significance of differences in bacterial counts from cardiac vegetations was assessed by analysis of variance, with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

In vitro studies.

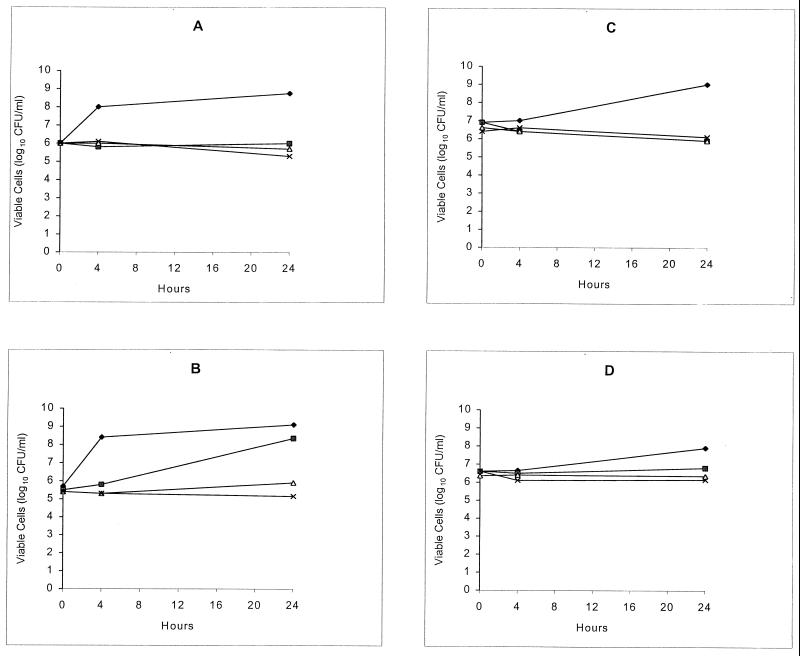

The results of the susceptibility studies are summarized in Table 1. MIC measurements were method and inoculum dependent. The addition of serum resulted in a marked decrease in the inhibitory activity of the drug. The time-kill curves shown in Fig. 1 confirmed that evernimicin was not bactericidal against the test strains, with or without rat serum. Exposure of each of the test strains to twofold stepwise increasing concentrations of the antibiotic resulted in the selection of resistant colonies of both E. faecalis 1310 (MIC ≥ 16 μg/ml) and E. faecium A1221 (MIC ≥ 16 μg/ml). Resistance was stable in the absence of the antibiotic, because the MICs remained at ≥16 μg/ml after serial passages on antibiotic-free plates for 2 weeks. When large inocula were plated onto agar containing evernimicin at eight times the MIC, resistant colonies of E. faecium A1221 and E. faecalis 1310 were detected at low frequencies (1 × 10−9 and 7 × 10−9, respectively). Upon retesting, the MICs of the emerging colonies were 2 and 4 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 1.

In vitro activity of evernimicin against the two test strains, E. faecalis 1310 and E. faecium A1221, using different test methods

| Method (inoculum) |

E. faecalis 1310

|

E. faecium A1221

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (μg/ml) | MBC (μg/ml) | MIC (μg/ml) | MBC (μg/ml) | |

| Agar dilution | 0.25 | 0.125 | ||

| Etest on Mueller-Hinton II agar | 0.75 | 0.5 | ||

| Etest on BHI agar | 1.5 | 0.75 | ||

| Broth macrodilution (105 CFU/ml) | 2 | 64 | 1 | 32 |

| Broth microdilution (103 CFU/ml) | 0.5 | 0.06 | ||

| Broth microdilution (105 CFU/ml) | 1 | >64 | 0.25 | 32 |

| Broth microdilution (107 CFU/ml) | >8 | >8 | ||

| Broth microdilution (105 CFU/ml) + 50% rat serum | >64 | >64 | 16 | 32 |

FIG. 1.

Time-kill curves showing in vitro activity of evernimicin against E. faecalis 1310 without (A) and with (B) 50% rat serum and E. faecium A1221 without (C) and with (D) 50% rat serum. The diamonds, squares, triangles, and crosses represent growth in 0, 2, 20, and 200 μg of antibiotic/ml, respectively.

In vivo studies. (i) E. faecalis endocarditis.

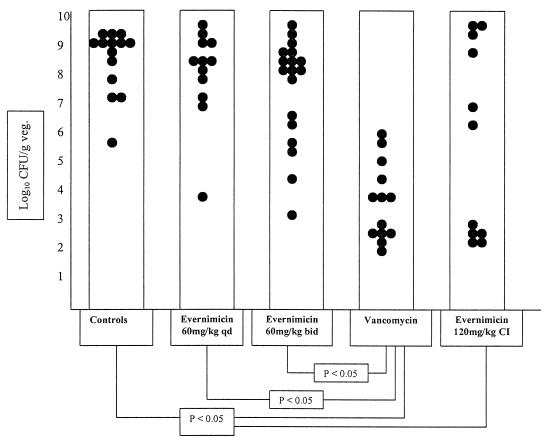

Treatment of endocarditis in animals infected with E. faecalis 1310 gave the results presented in Fig. 2. Bacterial counts (mean ± standard deviation) in vegetations from rats treated with evernimicin 60-mg/kg bolus q.d. (8.08 ± 1.62 log10 CFU/g; n = 12) or b.i.d. (7.52 ± 1.85 log10 CFU/g; n = 18) were not statistically different from those of control animals (8.51 ± 1.11 log10 CFU/g; n = 14). However, the latter dose of evernimicin (120 mg/kg/day) was effective when given by continuous infusion (5.75 ± 3.38 log10 CFU/g; n = 11), reducing viable bacteria to significantly lower counts than in controls. Except for one animal in the continuous-infusion treatment group (1 of 11; 9.1%), no animals had sterile vegetations after treatment with the above regimens.

FIG. 2.

Outcome of 5-day treatment of experimental endocarditis due to vancomycin-susceptible E. faecalis 1310 with either evernimicin or vancomycin. Control animals received no treatment. Each dot represents the bacterial density in the vegetation (veg.) of a single animal. Only statistically significant differences are indicated.

Vancomycin significantly reduced bacterial densities in vegetations (3.66 ± 1.38 log10 CFU/g; n = 13) compared with no treatment or evernimicin bolus regimens. Two animals in the vancomycin group had sterile vegetations after treatment (2 of 13; 15.4%). Mortality among rats treated with vancomycin (1 of 13; 7.7%) was significantly reduced compared with the control group (6 of 14; 42.9%) (P < 0.05). No mortality was observed in rats treated with evernimicin bolus injection b.i.d., and only one rat receiving evernimicin by continuous infusion died. Mortality in the evernimicin q.d. bolus injection group (5 of 12; 41.7%) was similar to and not statistically significantly different from that of the control animals.

(ii) E. faecium endocarditis.

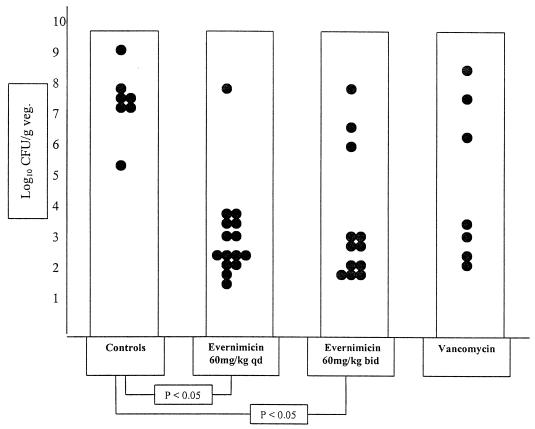

The results of treatment for animals infected with the low inoculum of the vancomycin-resistant strain, E. faecium A1221, are shown in Fig. 3. Evernimicin 60-mg/kg bolus q.d. and b.i.d. regimens were effective in reducing bacterial densities in vegetations (bacterial densities of 3.45 ± 1.44 log10 CFU/g, n = 15, and 3.81 ± 1.98 log10 CFU/g, n = 12, respectively). Both regimens were significantly better than no treatment (7.42 ± 1.07 log10 CFU/g; n = 7). Eight animals (53.3%) in the evernimicin 60-mg/kg bolus q.d. group had sterile vegetations after treatment, and no mortality was observed in any of the groups in this experiment. Unexpectedly, vancomycin was also effective when this inoculum was used (final densities, 5.04 ± 2.47 log10 CFU/g of vegetation; n = 7). We therefore performed additional experiments using a higher inoculum of E. faecium A1221. These results are shown in Fig. 4.

FIG. 3.

Outcome of 5-day treatment with either evernimicin or vancomycin of experimental endocarditis following a low inoculum (8 × 107 CFU/ml) of vancomycin-resistant E. faecium A1221. Control animals received no treatment. Each dot represents the bacterial density in the vegetation (veg.) of a single animal. Only statistically significant differences are indicated.

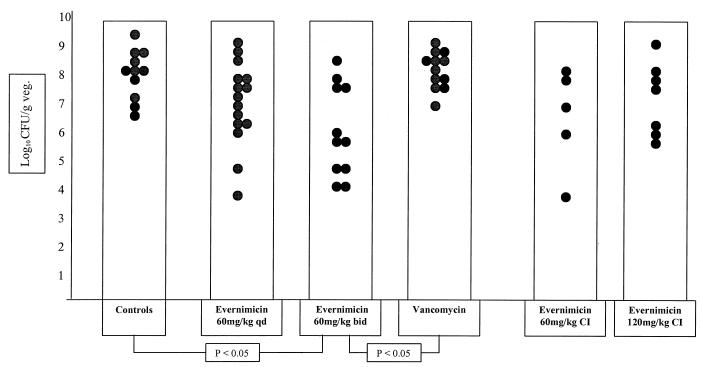

FIG. 4.

Outcome of 5-day treatment with either evernimicin or vancomycin of experimental endocarditis following a high inoculum (109 CFU/ml) of vancomycin-resistant E. faecium A1221. Control animals received no treatment. Each dot represents the bacterial density in the vegetation (veg.) of a single animal. Only statistically significant differences are indicated. CI, continuous infusion.

In these experiments, vancomycin was ineffective (8.52 ± 0.68 log10 CFU/g of vegetation; n = 12). Evernimicin 60-mg/kg bolus i.v. q.d. also failed to reduce bacterial counts (7.25 ± 1.54 log10 CFU/g; n = 15), which were not different from those of the control (8.34 ± 0.91 log10 CFU/g; n = 11) or vancomycin-treated animals. Evernimicin at 60 mg/kg b.i.d. was effective, with residual counts (6.27 ± 1.63 log10 CFU/g; n = 11) significantly reduced compared with those of controls and vancomycin-treated animals.

In view of the favorable results of higher-dose evernimicin against the vancomycin-resistant strain, a small number of animals were treated by continuous infusion. This was intended as an exploratory experiment without the intention to pursue the statistical significance of the results. However, continuous infusion of neither 60 mg/kg/day (6.73 ± 1.90 log10 CFU/g of vegetation; n = 5) nor 120 mg/kg/day (7.46 ± 1.28 log10 CFU/g of vegetation; n = 7) was obviously superior to the bolus regimens.

No vegetations were rendered culture negative by any of the treatment regimens in this (high-inoculum E. faecium infection) arm of the study. The mortality rate in the control group (2 of 11; 18.2%) was not significantly different from that observed in the vancomycin-treated group (3 of 12; 25%). No mortality was observed in the groups of animals that received evernimicin bolus i.v. treatment (P < 0.05 versus the controls and the vancomycin group).

(iii) Serum drug concentrations and resistance monitoring.

The mean serum drug concentrations achieved during treatment with the various regimens are shown in Table 2. Serum evernimicin levels determined at the time of sacrifice for three rats treated with each of the studied regimens were undetectable (<0.78 μg/ml), thus making significant antibiotic carryover unlikely during determination of colony counts.

TABLE 2.

Serum antibiotic concentrations during treatment with various regimens evaluated in the studya

| Regimen (dose) | No. of animals | Peak concnb | Trough concnc | Steady-state concn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCH 27899 (60 mg/kg q.d.) | 7 | 343.16 ± 74.52 | <0.78 | |

| SCH 27899 (60 mg/kg b.i.d.) | 9 | 501.54 ± 91.13 | 2.22 ± 1.2 | |

| SCH 27899 (120 mg/kg/day CI)f | 5 | 7.66 ± 2.05d | ||

| SCH 27899 (60 mg/kg/day CI) | 2 | 2.58 ± 0.29d | ||

| Vancomycin (150 mg/kg/day CI) | 5 | 32.74 ± 10.24e |

Values are means ± standard deviations and are given in micrograms per milliliter.

Sampling at 15 min after injection.

Sampling at 24 h after last dose for the q.d. regimen and at 12 h after last dose for the b.i.d. regimen.

During sampling, antibiotic infusion was discontinued for approximately 10 min.

During sampling, animals continued to receive antibiotic i.v.

CI, continuous infusion.

No resistant colonies of either of the test organisms were detected by plating 0.1 ml of the homogenate of vegetations on evernimicin-containing plates. Based on colony counts from vegetations of the animals sampled, the number of colonies in the amount of homogenate plated varied from <1 to approximately 5 × 106 CFU and exceeded 104 CFU for only three animals. Individual colonies from antibiotic-free plates, when retested, were inhibited by evernimicin at concentrations that were equal to or within 1 dilution of the MICs of the original strains.

DISCUSSION

It has previously been shown that the everninomicin family of antibiotics has potent activity against gram-positive organisms in vitro (6, 12). The susceptibilities to evernimicin of the two organisms used in this study were typical of those reported for vancomycin-susceptible or -resistant strains of enterococci (12). Enterococci are now the third most common cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections (4), and as the resistance patterns of these organisms become broader, the everninomicins could provide new therapeutic options against these pathogens. In the present study, an experimental model of enterococcal endocarditis was used to evaluate the in vivo antimicrobial efficacy of evernimicin. It is important to note that bactericidal activity of an antimicrobial is not mandatory for demonstration of antimicrobial efficacy in this model. In prior studies using this model with another strain of E. faecalis, we demonstrated that 5 days of treatment with vancomycin could reduce residual bacterial densities within cardiac vegetations by approximately 5 log10 CFU/g compared with untreated controls, even though the agent was only bacteriostatic against the test strain (14). However, even when treatment with vancomycin was extended to 10 days, only approximately 40% of animals remained culture negative when observed off therapy. Therefore, we believed that this model would be useful to assess the in vivo antibacterial activity of evernimicin, even though the agent was bacteriostatic in vitro. We hoped that the model could also provide information on possible dosing regimens for the new compound.

The results of the study indicated that intermittent administration of evernimicin, even at a dose of 60 mg/kg b.i.d., was not effective against infection caused by E. faecalis 1310. At this dose level, peak serum levels were manyfold above the MIC (and MBC) determined under standard conditions. Trough levels remained well above the MIC determined by agar dilution or low-inoculum broth microdilution and still marginally exceeded the MIC determined by broth macrodilution. The marked reduction in activity of evernimicin tested in 50% rat serum, with a MIC exceeding 64 μg/ml, may help to explain these results. Nevertheless, as shown by time-kill testing results depicted in Fig. 1B, while the inhibitory activity of evernimicin at 2 μg/ml was clearly reduced in the presence of serum, at 20 μg/ml this agent still demonstrated a significant inhibitory effect on the growth of the organism. The specific variables that account for differences in assessment of activity by these two methods are unknown. Administration of the 120-mg/kg/day dose by continuous infusion, which achieved serum concentrations of evernimicin well above the MIC throughout the dosing, did result in a statistically significant reduction in bacterial counts within vegetations, but still to a lesser degree than observed with vancomycin. The fact that the mean serum concentrations of evernimicin achieved with this regimen in rats fell below the MIC determined in vitro with serum-supplemented broth underscores the importance of the time-kill study observations noted above.

Against the vancomycin-resistant strain of E. faecium, both bolus evernimicin regimens reduced viable counts in vegetations by approximately 4 log10 CFU/g when an inoculum of 8 × 107 CFU/ml was used. However, vancomycin was also unexpectedly active in the low-inoculum infection. Use of a higher inoculum appeared to improve the performance of the E. faecium model, with final colony counts in untreated animals being similar to those observed in rats infected with E. faecalis 1310 and with vancomycin therapy proving ineffective. Under these conditions, however, only evernimicin at the higher dose of 60 mg/kg b.i.d. (but not at 60 mg/kg q.d.) reduced bacterial counts to a statistically significant level compared with the control group. These results likely reflect the inoculum dependence of evernimicin activity against the test organism shown in Table 1.

Therefore, despite the very favorable in vitro activity of the compound (12; Menzel et al., 37th ICAAC), the in vivo antibacterial efficacy of evernimicin was modest. Several possibilities could explain this discrepancy. Our in vitro data showed that the activity of evernimicin was both inoculum dependent and adversely affected by rat serum. These factors may well have contributed to the lack of substantial activity of some regimens in spite of serum drug concentrations well above the MIC for most of the dosing intervals. These factors possibly also contribute to the great variability in final bacterial densities observed within each evernimicin treatment arm. Another possible explanation for both intersubject variability and limited overall activity of some regimens would be the emergence of resistant clones during treatment. Although in vitro data supported this possibility as an explanation, we were unable to detect resistant subpopulations from either test strain in homogenates of vegetations from treated animals. Another potential explanation for suboptimal efficacy in experimental endocarditis is heterogeneous diffusion of an antibiotic into large vegetations (1–3). To evaluate this possibility, we compared the average weight of the vegetations in the different treatment groups with final bacterial densities. However, we were not able to determine any consistent correlation between the weight of vegetations and viable bacteria in the evernimicin treatment groups (data not shown). While these results do not support the hypothesis that penetration is a limiting factor (because one might have predicted larger vegetations to have higher final colony counts), autoradiographic studies would more definitively address this question.

The evaluation of the comparative therapeutic efficacies of new antibiotics or novel regimens in animal models must be extrapolated to human infections with great caution. One example from the present study was the unexpected activity of vancomycin against low-inoculum infection with vancomycin-resistant E. faecium. In our study, the efficacy of evernimicin in this experimental model of endocarditis with either E. faecalis or E. faecium was modest. It is quite possible that less severe infections due to such organisms, either in experimental systems or in the clinical setting, may respond considerably better. The place of the new compound in the treatment of serious enterococcal infections requires further clarification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from Schering Plough Research Institute, Kenilworth, N.J. Maria Souli was supported in part by a grant from the Hellenic Society for Infectious Diseases and in part by a grant from Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation.

We thank Robert C. Moellering, Jr., and David Loebenberg for their invaluable advice concerning these studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caron F, Kitzis M D, Gutmann L, Crémieux A C, Mazière B, Vallois J M, Saleh-Mghir A, Lemeland J F, Carbon C. Daptomycin or teicoplanin in combination with gentamicin for the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to a highly glycopeptide-resistant isolate of Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2611–2616. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.12.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crémieux A C, Mazière B, Vallois J M, Ottaviani M, Azancot A, Raffoul H, Bouvet A, Pocidalo J J, Carbon C. Evaluation of antibiotic diffusion into cardiac vegetations by quantitative autoradiography. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:938–944. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.5.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crémieux A C, Mazière B, Vallois J M, Ottaviani M, Bouvet M, Pocidalo J J, Carbon C. Ceftriaxone diffusion into cardiac fibrin vegetation. Qualitative and quantitative evaluation by autoradiography. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1991;5:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1991.tb00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones R N, Marshall S A, Pfaller M A, Wilke W W, Hollis R J, Erwin M E, Edmond M B, Wenzel R P the SCOPE Hospital Study Group. Nosocomial enterococcal blood stream infections in the SCOPE program: antimicrobial resistance, species occurrence, molecular testing results, and laboratory testing accuracy. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1997;29:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(97)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krogstad D J, Moellering R C., Jr . Antimicrobial combinations. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 2nd ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins; 1985. pp. 537–595. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakashio S, Iwasawa H, Dun F Y, Kanemitsu K, Shimada J. Everninomicin, a new oligosaccharide antibiotic; its antimicrobial activity, post-antibiotic effect and synergistic bactericidal activity. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1995;21:7–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 3rd ed. Approved standard. NCCLS document M7-A3. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson R D, Steigbigel R T, Davis H T, Chapman S W. Method for reliable determination of minimal lethal antibiotic concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;18:699–708. doi: 10.1128/aac.18.5.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabath L D, Anhalt J P. Assay of antimicrobials. In: Lennette E H, Balows A, Hausler W J Jr, Truant J P, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1980. pp. 485–490. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santoro J, Levison M E. Rat model of experimental endocarditis. Infect Immun. 1978;19:915–918. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.3.915-918.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thauvin C, Eliopoulos G M, Willey S, Wennersten C, Moellering R C., Jr Continuous-infusion ampicillin therapy of enterococcal endocarditis in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:139–143. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urban C, Mariano N, Mosinka-Snippas K, Wadee C, Chahrour T, Rahal J J. Comparative in-vitro activity of SCH 27899, a novel everninomicin, and vancomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;37:361–364. doi: 10.1093/jac/37.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstein M J, Luedemann G M, Oden E M, Wagman G H. Everninomicin, a new antibiotic complex from Micromonospora carbonacea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1964;4:24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao J D C, Thauvin-Eliopoulos C, Eliopoulos G M, Moellering R C., Jr Efficacy of teicoplanin in two dosage regimens for experimental endocarditis caused by a β-lactamase-producing strain of Enterococcus faecalis with high-level resistance to gentamicin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:827–830. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.5.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]