PURPOSE:

Serious Illness Conversations (SICs) are structured conversations between clinicians and patients about prognosis, treatment goals, and end-of-life preferences. Although behavioral interventions may prompt earlier or more frequent SICs, their impact on the quality of SICs is unclear.

METHODS:

This was a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial (NCT03984773) among 78 clinicians and 14,607 patients with cancer testing the impact of an automated mortality prediction with behavioral nudges to clinicians to prompt more SICs. We analyzed 318 randomly selected SICs matched 1:1 by clinicians (159 control and 159 intervention) to compare the quality of intervention vs. control conversations using a validated codebook. Comprehensiveness of SIC documentation was used as a measure of quality, with higher integer numbers of documented conversation domains corresponding to higher quality conversations. A conversation was classified as high-quality if its score was ≥ 8 of a maximum of 10. Using a noninferiority design, mixed effects regression models with clinician-level random effects were used to assess SIC quality in intervention vs. control groups, concluding noninferiority if the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was not significantly < 0.9.

RESULTS:

Baseline characteristics of the control and intervention groups were similar. Intervention SICs were noninferior to control conversations (aOR 0.99; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.09). The intervention increased the likelihood of addressing patient-clinician relationship (aOR = 1.99; 95% CI, 1.23 to 3.27; P < .01) and decreased the likelihood of addressing family involvement (aOR = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.90; P < .05).

CONCLUSION:

A behavioral intervention that increased SIC frequency did not decrease their quality. Behavioral prompts may increase SIC frequency without sacrificing quality.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with cancer undergo emotional and psychologic distress through their disease course.1-3 Serious illness conversations (SICs) are structured discussions between the physician, patient, and patient family members to determine a patient's goals and values for therapy. SICs decrease patient anxiety and depression, and health care spending without increasing patient distress.4-6 Although there is a need for earlier and more frequent initiation of SICs, most patients with advanced cancer die without a documented SIC.7 There has been increasing interest in using behavioral interventions targeting clinicians to initiate more SICs with the aim of improving patient outcomes.8-13 In a pragmatic randomized trial, we found that an algorithm-based prompt to clinicians led to an increase in documentation rates of SICs from 3% to 15% of all patients at a large academic cancer center.9 However, the effect of such interventions on SIC quality has not been studied.

Although there is weak consensus on what defines a high-quality conversation,14 individual components of the SIC have been rated as important by patients and families and are associated with improved quality of end-of-life care.15 Several studies have shown that discussion of components of the SIC, including life-prolonging care preferences, prognostic understanding, and family involvement in decision making, is associated with a higher likelihood of goal-concordant care and a lower likelihood of aggressive end-of-life care.16-24 Previous work has also demonstrated that although most elderly patients and their families have considered their preferences for medical treatment at the end of life and prefer comfort measures, there is inadequate documentation of these wishes in the electronic health record (EHR), leading to a disparity between patient and family preferences for less aggressive care and the care that is ultimately provided.25 EHR documentation of SICs represents a readily available source of data, and expert stakeholder groups have recognized that documentation of SICs captures key aspects of communication quality and process.14,26 For these reasons, we used comprehensiveness of SIC documentation as a surrogate for high-quality conversation.

Although algorithm-driven prompts may increase the frequency of SICs, there is concern that the prompted conversations may be inferior in quality to organic conversations.27 Attempts to increase end-of-life planning through increased reporting requirements have likely resulted in lower quality interactions. Although Physician Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) completion in California nursing homes increased to nearly 100% after POLST completion was added to the Minimum Data Set, interviews with cognitively intact nursing home residents and family found that few recalled discussion of POLST.28 Although behavioral interventions differ from such reporting requirements, there is a similar concern that behavioral interventions to increase SICs may decrease their quality by prompting less informed conversations or by causing clinicians to focus on document completion. In this secondary analysis of a large cluster-randomized trial, we examined the impact of an algorithm-based prompt on the quality of SICs using a validated codebook.29 We hypothesized that, after matching on the clinician, the behavioral intervention would not decrease the quality of SICs.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a secondary analysis of a stepped-wedge, cluster randomized clinical trial (NCT03984773) to determine whether intervention (prompted) SICs are noninferior in quality to control (unprompted) SICs.9 We reviewed EHR documentation of SICs with oncology patients who were receiving care at nine medical oncology practices within a large tertiary academic cancer center. The clinical trial evaluated the effect of a multipronged intervention consisting of three components, which incorporate well-established principles from behavioral economics: (1) a weekly e-mail to clinicians with performance feedback, indicating the number of SICs that the clinician performed and a peer comparison. (2) A personalized dashboard, updated weekly, which identified up to six high-risk patients (predicted 180-day mortality > 10%) as patients who may benefit from a SIC. Predicted 180-day mortality risk was calculated using a validated machine learning algorithm.8 (3) Default opt-out text message prompts to clinicians on the patient's appointment day to consider an SIC. Performance feedback, peer comparisons, and defaults have all been shown to affect the frequency of desired behaviors.30-33 SICs were documented using the Advanced Care Planning note template in the EHR, which includes a predefined text field corresponding to each topic suggested in the SIC guide developed by Ariadne labs.4,5 All clinicians were trained in the use of the SIC guide at least 3 months before the start of the trial, with a range of 5-18 months. Full details of the trial methods and intervention were published elsewhere.34 We obtained a record of all SICs conducted in the study period, matched the lists of control and intervention conversations by clinician with control for clinician-level effects, and abstracted quality domains by chart review. We compared the quality of control and intervention SICs using a noninferiority analysis. A noninferiority design was selected because the intervention was designed to increase the frequency of SICs, rather than their quality. The focus of this study was assessing whether the intervention reduced quality of SICs as an unintended effect.

The study protocol was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (Protocol, online only). A waiver of informed consent was granted because this was an evaluation of a health system initiative that posed minimal risk to clinicians and patients.

Study Sample

The study included clinicians who cared for adults at eight specialty oncology sites (breast, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, lymphoma, melanoma, central nervous system, myeloma, and thoracic or head and Neck) and one general oncology site. Patients were eligible for this study if they were 18 years or older and had a SIC during the study period between January 1, 2019, and May 6, 2020, with a clinician who participated in the Conversation Connect Trial (NCT03984773). Clinician inclusion and exclusion criteria were reported elsewhere.34

All documented SICs conducted with patients having high risk of mortality (predicted 180-day mortality risk score > 10%) between June 17, 2019 and May 6, 2020, associated with the intervention were included in the intervention group. All SICs documented in the EHR that were conducted by a clinician with a high-risk patient as part of a control group or outside the trial study period between January 1, 2019, and October 1, 2019, were included in the control group. All included SICs represented the first documented SICs with that patient, and no patient was included in both the control and intervention groups. Intervention and control SICs were 1:1 matched by clinician with control for the effect of the clinician on quality scores; after matching, 120 (43%) control conversations and 91 (31%) intervention conversations were excluded. A total of 159 control conversations and 159 intervention conversations conducted by 52 clinicians were studied after the application of the exclusion criteria.

Outcome

The primary outcome was a dichotomized measure of SIC quality, with the high-quality group defined by a quality score ≥ 8. To measure SIC quality, we assigned an integer score ranging from 0 to 10 to each conversation on the basis of the number of predefined conversation domains present in the EHR documentation of the conversation. A trained blinded researcher (E.H.L.) abstracted the following 10 binary features from the SIC note: (1) prognostic understanding, (2) information preferences, (3) goals, (4) fears and worries, (5) strength, (6) critical abilities, (7) trade-offs, (8) family involvement, (9) patient-clinician relationship, and (10) practical issues. Each of these domains were coded as Present (1) or Absent (0), on the basis of a validated codebook used in a previous qualitative study of SIC quality.29 These conversation features were chosen because they were included on the standard SIC template and they were also associated with positive clinical outcomes such as goal-concordant care, less aggressive care, and higher subjective satisfaction.16-24 Two of the elements (patient-clinician relationship and practical issues) were assessed from free-text elements; the other eight elements were assessed from structured data elements. SICs were dichotomized into two groups: a high-quality (score ≥ 8) and low-quality (score < 8) group. In our sensitivity analysis, we analyzed the quality score as a continuous outcome.

Inter-rater reliability of SIC quality was established by two trained blinded researchers (E.H.L. and R.B.P.) who jointly coded 20% of the total sample (n = 64), targeting a pooled kappa across the 10 quality domains of ≥ 0.8.35 SICs were coded in groups of 10, and each group was discussed for disagreements on coding and to update the codebook criteria in an iterative process.

Statistical Analysis

We performed statistical analysis using RStudio software, version 1.3.959. We used intention-to-treat approach for all analyses (as per the original clinical trial), using the patient as the unit of analysis and clustering at the level of the clinician. To compare patient characteristics between intervention and control groups, we used Kruskal-Wallis tests for all continuous variables and chi-square tests for all categorical variables.

For our primary analysis, we fit a mixed effects logistic regression model using the intervention variable, whether a note was in the intervention or control group, as the sole predictor of the dichotomized quality outcome, and a random intercept to account for the effect of the clinician.36 Noninferiority would be declared if the lower limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI for the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was not < 0.9, equivalent to a one-sided test with an alpha value of 0.025.37,38 As a sensitivity analysis, we used mean quality score as a continuous outcome and fit a mixed effects linear regression model. Noninferiority would be declared if the lower limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI for the intervention effect was not less than -1 point. Additional covariates included in sensitivity analyses included patient race (White v African American v Others) and sex (male v female), as indicated in the EHR.

To study the heterogeneity of the effect of the intervention on each of the 10 SIC quality domains, we ran 10 independent mixed effects logistic regression models, each predicting the presence or absence of each of the 10 conversation domains using the intervention variable as the sole predictor, with a random intercept to account for random effects at the level of the clinician. In each analysis, we used 0.9 as the noninferiority margin.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

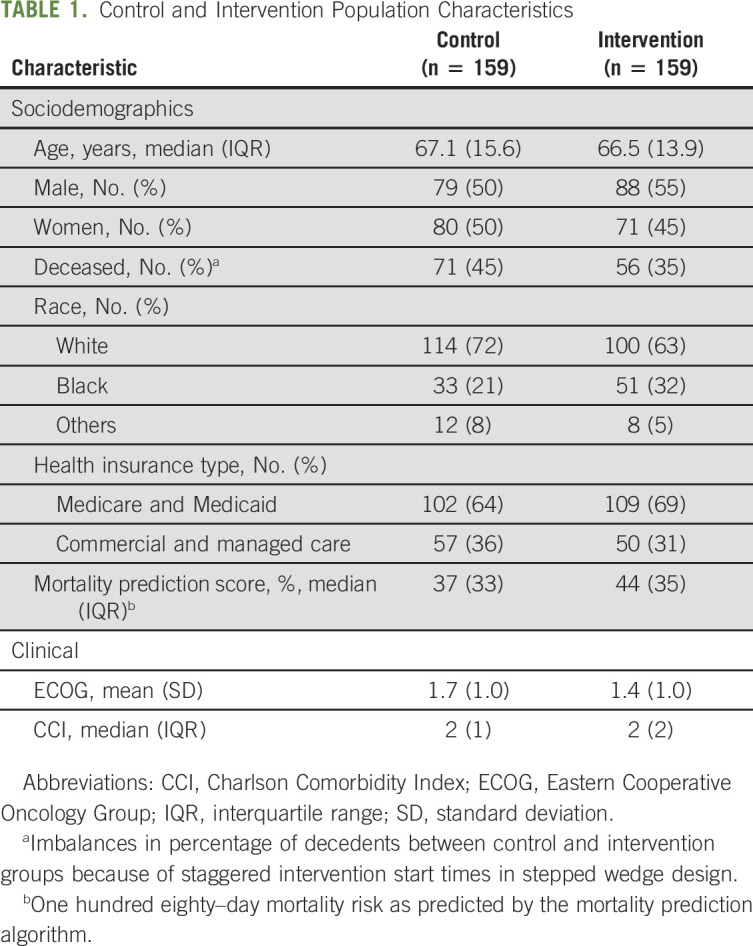

We studied 364 conversations conducted with 318 patients. Patients' mean age was 67.1 years, 151 (47%) were female, 214 (67%) were White, 107 (34%) were commercially insured, and 127 (40%) were deceased at the time of the study. There were no differences between the control and intervention group in age (67.2 v 67.0), sex (50% v 45%), percent publicly insured (64% v 69%), or median predicted 180-day mortality risk (37% v 44%).9 The control group had a significantly larger fraction of deceased patients (45% v 35%, P < .001). No other statistically significant differences were found (Table 1). The pooled kappa calculated on the agreement across all 10 conversation features for the 64 conversations was 0.9, which indicated a high level of inter-rater agreement.35

TABLE 1.

Control and Intervention Population Characteristics

SIC Quality Impact

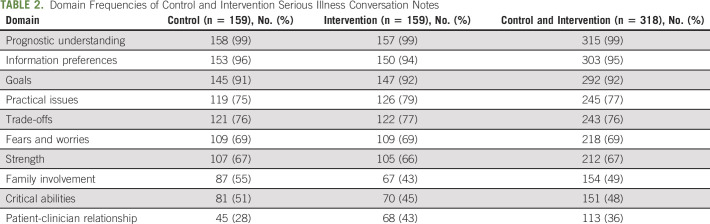

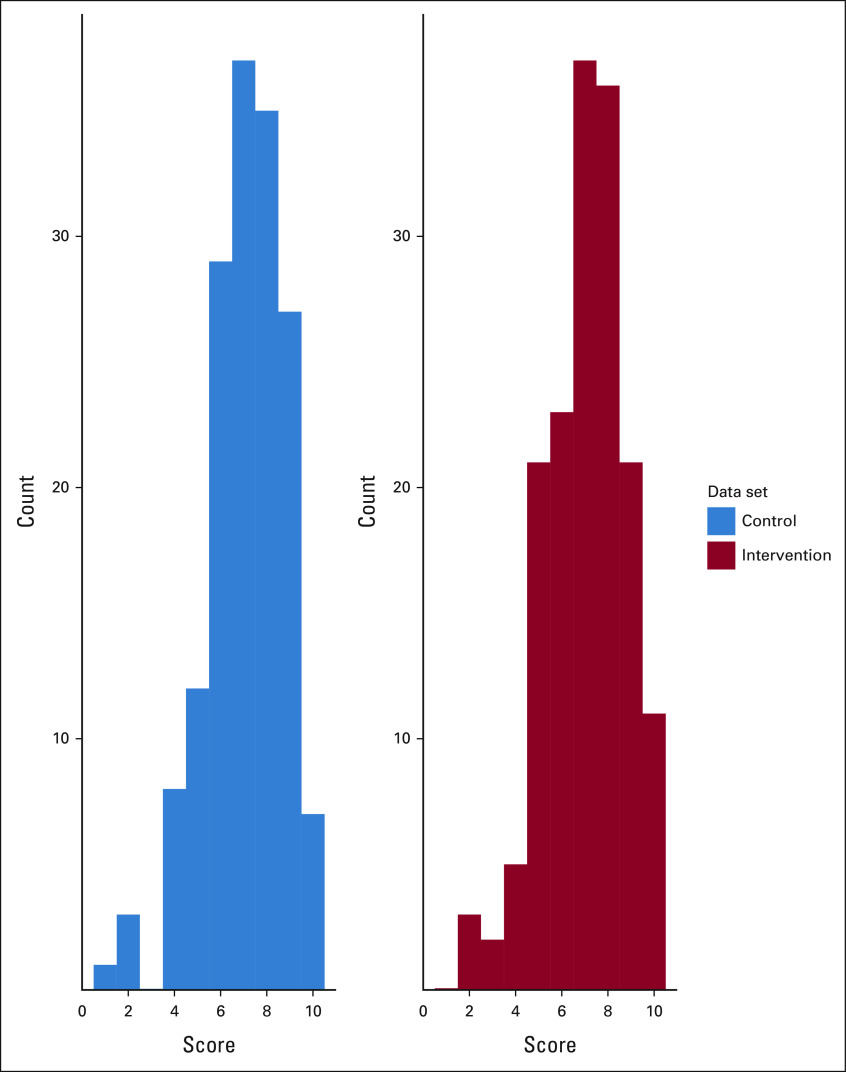

The mean quality score for Intervention SICs was 7.05, and the mean quality score for Control SICs was 7.07 (Table 2). Sixty-eight (43%) intervention conversations and 69 (43%) control conversations were of high quality. The distribution of quality scores was similar in intervention and control conversations (Fig 1). Intervention SICs were noninferior to Control SICs (aOR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.09). The lower limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI was an aOR of 0.91, establishing noninferiority of the intervention SICs. Adding race and sex into the model did not change this result (aOR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.91 to 1.10). Our sensitivity analysis used a continuous outcome for quality and showed noninferiority of the intervention (coefficient = –0.03; 95% CI, –0.33 to 0.28), where the coefficient represents the effect of the intervention on the mean quality score. The lower limit of the one-sided 97.5% CI was –0.33, establishing noninferiority of the intervention SICs.

TABLE 2.

Domain Frequencies of Control and Intervention Serious Illness Conversation Notes

FIG 1.

Distributions of quality scores in control and intervention SICs. Histograms comparing the distribution of SIC quality scores for intervention (n = 159, red) and control (n = 159, blue) SICs. The quality score is an integer score ranging from 0 to 10, which corresponds to the number of validated quality domains present in the SIC. The 10 quality domains include (1) prognostic understanding, (2) information preferences, (3) goals, (4) fears and worries, (5) strength, (6) critical abilities, (7) trade-offs, (8) family involvement, (9) patient-clinician relationship, and (10) practical issues. Quality domains were abstracted by chart review of electronic health record documentation of the SICs by a trained blinded researcher (E.H.L.). Two of the elements (patient-clinician relationship and practical issues) were assessed from free-text elements within the SIC; the other eight elements were assessed from structured data elements within the SIC. SIC, serious illness conversation.

Heterogeneity of the Intervention's Effects on Quality Domains

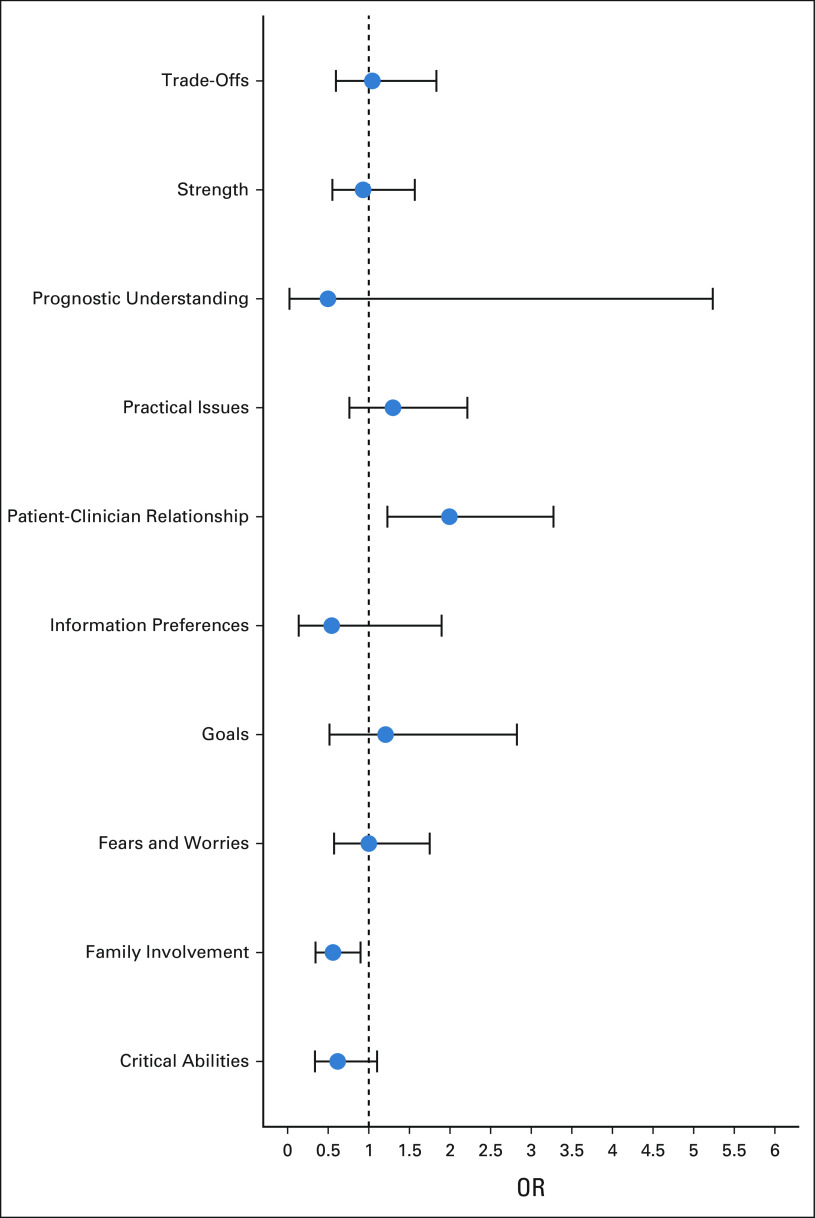

In analyses of differential impact across SIC quality domains, the intervention was associated with an increase in fulfilling the patient-clinician relationship domain (43% intervention v 28% control; aOR = 1.99; 95% CI, 1.23 to 3.27; P < .01). The intervention was associated with a decrease in fulfilling the family involvement domain (43% intervention v 55% control; aOR = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.90; P < .05). There was no significant difference between intervention and control conversations in the other eight quality domains (Fig 2).

FIG 2.

Effect of intervention on individual SIC quality domains. Mixed effects logistic regression models were fit where the sole predictor is the intervention variable and the outcome is each of the 10 validated quality domains, and a random intercept accounts for the influence of the clinician. An odds ratio above one indicates that SICs in the intervention group are more likely to include documentation of the corresponding SIC quality domain compared with SICs in the control group. OR, odds ratio. SIC, serious illness conversation.

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the impact of an EHR-based health systems initiative designed to increase the frequency of SICs with patients at high risk of mortality on SIC quality, using comprehensiveness of SIC documentation as a measure of conversation quality. This intervention was previously found to quadruple the rate of documentation of SICs.9 However, interventions that increase the frequency of a clinical interaction risk worsen their quality through factors such as an increased tendency to check boxes and complete documentation.27 Although the literature investigating the impact of behavioral interventions on SICs quality is limited, previous attempts to increase goals of care conversations, such as implementing reporting requirements for POLST completion in California nursing homes, have been shown to increase form completion rates while likely sacrificing quality of the conversation.28 We showed that this intervention did not decrease the quality of initial SICs while increasing their frequency. Although we did not demonstrate superiority of the quality of prompted SICs, we do not consider this a negative result. Our intervention was intended to increase the number of documented SICs, not their quality. These findings are reassuring that well-designed behavioral interventions may be used to increase the frequency of clinician-patient conversations in oncology without sacrificing at least one metric of quality. To our knowledge, this study is the first to characterize the impact of an algorithm-based behavioral intervention on the quality of initial clinician-patient SICs.

Although there is broad agreement between physicians and patients on what they believe are important aspects of end-of-life care,15 there is no gold standard for a high-quality SIC.14,39 Previous studies on the quality of physician-patient interactions also typically rely on patient-reported outcomes (PROs).40,41 Although PROs are an important measure of interaction quality, expert stakeholders have recognized that PROs are suboptimally captured because of factors such as low survey response rates and burden on seriously ill patients, and there is no well-defined standard of which PROs should be used to assess conversation quality.14 Because our study was a pragmatic trial, we did not mandate collection of PROs during the prospective component of the clinical trial and hence cannot directly use PROs to assess patient or clinician perceptions of communication quality.

Our study used comprehensiveness of clinician documentation as a surrogate for quality of the SIC for several key reasons. We used a validated template to measure documentation of patient-centered communication such as values and goals and prognostic communication according to patient preferences. Our approach captured documentation of conversation domains that have been widely accepted as key aspects of shared decision making and suggestive of high-quality communication.14,26,42 Our approach also has the advantage of using readily available sources of data in the EHR. However, given the importance of patient experience of communication, future study of SIC quality should also include measurement and validation of PROs40,43,44 and validated scales of anxiety and depression.14,26,43

We also found that the intervention had different effects on each of the 10 SIC quality domains, significantly increasing the likelihood that intervention conversations fulfilled the criteria for patient-clinician relationship and significantly decreasing the likelihood that they fulfilled the criteria for family involvement. In a previous study, a higher percentage of physicians rated discussing patient-clinician relationships as important, compared with the number rating discussing patients' relationships with family and friends as important.15 Clinicians prompted to initiate a SIC may begin by discussing topics that they believe are most important.

There are several limitations to this study. First, we were limited in the range of downstream patient outcomes that could be studied. We did not have adequate follow-up to measure guideline-based end-of-life outcomes, including chemotherapy utilization at the end of life, inpatient death rates, and hospice enrollment. Future well-powered studies should address these issues. Additionally, we were limited to measuring quality using documented SIC notes because, as this was a pragmatic trial involving 14,607 patients, we did not mandate collection of PROs as a metric of communication quality. These notes use a standardized template with several predefined fields that correlate with metrics from a validated codebook of SIC quality.29 Future studies should also collect PRO measures of communication quality for further validation of PROs and direct measurement of patient experiences of communication quality. Finally, the results of this study may be difficult to generalize, particularly to noncancer settings. However, the trial included a diverse set of 14,607 patients seen at a tertiary academic and general oncology site and thus represents various patients and practice settings in oncology.

In conclusion, a behavioral intervention that was found to significantly increase the frequency of SICs was not associated with a decrease in their quality as measured by comprehensiveness of EHR documentation. The intervention was also associated with a significant increase in the frequency of discussion of the patient-clinician relationship and a significant decrease in the frequency of discussion of family involvement. Behavioral interventions may be used to increase the frequency of SICs without sacrificing their quality. Further work may be needed to correlate EHR documentation with PRO measures of communication quality and to increase family involvement during the behavioral intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Manqing Liu, MHS, for her contributions in advising the design of the statistical analyses presented in this article. We also thank Maria Nelson, MA, for her contributions in advising the design of the metrics presented for evaluating inter-rater reliability. E.H.L. and R.B.P. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

William Ferrell

Research Funding: Humana

Pallavi Kumar

Consulting or Advisory Role: Acceleron Pharma (I), Amylyx (I)

Research Funding: Amicus Therapeutics (I), Amylyx (I), Acceleron Pharma (I)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Acceleron Pharma (I), Amylyx (I)

Lynn M. Schuchter

Consulting or Advisory Role: Incyte

Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Merck (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst)

Expert Testimony: Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Stand U 2 Cancer

Mitesh S. Patel

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Catalyst Health Network

Consulting or Advisory Role: Life.io, HealthMine, Holistic Industries

Research Funding: Deloitte

Christopher R. Manz

Research Funding: Genentech

Ravi B. Parikh

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Merck, Google, GNS Healthcare

Consulting or Advisory Role: GNS Healthcare, Cancer Study Group, Onc.AI

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Conquer Cancer Foundation, Flatiron Health

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by the Penn Center of Precision Medicine (recipients are R.B.P. and C.R.M.) and the National Cancer Institute K08-CA-263541 (recipient is R.B.P.).

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Individual participant data will not be available. The study protocol is available (Protocol). No other documents will be available. Reason: The study involves extensive electronic medical record data for all trial participants that cannot be accessed outside of the health system.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Eric H. Li, William Ferrell, Nina O'Connor, Lynn M. Schuchter, Mitesh S. Patel, Christopher R. Manz, Ravi B. Parikh

Financial support: Ravi B. Parikh

Administrative support: Tamar Klaiman, Ravi B. Parikh

Provision of study materials or patients: Lynn M. Schuchter, Ravi B. Parikh

Collection and assembly of data: Eric H. Li, Ravi B. Parikh

Data analysis and interpretation: Eric H. Li, Tamar Klaiman, Pallavi Kumar, Nina O'Connor, Lynn M. Schuchter, Jinbo Chen, Christopher R. Manz, Ravi B. Parikh

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Impact of Behavioral Nudges on the Quality of Serious Illness Conversations Among Patients With Cancer: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

William Ferrell

Research Funding: Humana

Pallavi Kumar

Consulting or Advisory Role: Acceleron Pharma (I), Amylyx (I)

Research Funding: Amicus Therapeutics (I), Amylyx (I), Acceleron Pharma (I)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Acceleron Pharma (I), Amylyx (I)

Lynn M. Schuchter

Consulting or Advisory Role: Incyte

Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Merck (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst)

Expert Testimony: Pfizer

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Stand U 2 Cancer

Mitesh S. Patel

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Catalyst Health Network

Consulting or Advisory Role: Life.io, HealthMine, Holistic Industries

Research Funding: Deloitte

Christopher R. Manz

Research Funding: Genentech

Ravi B. Parikh

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Merck, Google, GNS Healthcare

Consulting or Advisory Role: GNS Healthcare, Cancer Study Group, Onc.AI

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Conquer Cancer Foundation, Flatiron Health

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, et al. : The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology 10:19-28, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells N, Murphy B, Wujcik D, et al. : Pain-related distress and interference with daily life of ambulatory patients with cancer with pain. Oncol Nurs Forum 30:977-986, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. : High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 90:2297-2304, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paladino J, Bernacki R, Neville BA, et al. : Evaluating an intervention to improve communication between oncology clinicians and patients with life-limiting cancer: A cluster randomized clinical trial of the serious illness care program. JAMA Oncol 5:801-809, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. : Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 179:751-759, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakin JR, Neal BJ, Maloney FL, et al. : A systematic intervention to improve serious illness communication in primary care: Effect on expenses at the end of life. Healthcare 8:100431, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schubart JR, Levi BH, Bain MM, et al. : Advance care planning among patients with advanced cancer. J Oncol Pract 15:e65-e73, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manz CR, Chen J, Liu M, et al. : Validation of a machine learning algorithm to predict 180-day mortality for outpatients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 6:1723-1730, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manz CR, Parikh RB, Small DS, et al. : Effect of integrating machine learning mortality estimates with behavioral nudges to clinicians on serious illness conversations among patients with cancer: A stepped-wedge cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 6:e204759, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parikh RB, Kakad M, Bates DW: Integrating predictive analytics into high-value care: The dawn of precision delivery. JAMA 315:651-652, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weng SF, Reps J, Kai J, et al. : Can machine-learning improve cardiovascular risk prediction using routine clinical data? PLoS One 12:e0174944, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertsimas D, Dunn J, Pawlowski C, et al. : Applied informatics decision support tool for mortality predictions in patients with cancer. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2:1-11, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan B, Tarbi E: Behavioral economics: Applying defaults, social norms, and nudges to supercharge advance care planning interventions. J Pain Symptom Manage 58:e7-e9, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders JJ, Paladino J, Reaves E, et al. : Quality measurement of serious illness communication: Recommendations for health systems based on findings from a symposium of national experts. J Palliat Med 23:13-21, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinhauser KE: Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 284:2476-2482, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. : Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: A prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 30:4387-4395, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al. : End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 28:1203-1208, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. : The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 340:c1345, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heyland DK, Allan DE, Rocker G, et al. : Discussing prognosis with patients and their families near the end of life: Impact on satisfaction with end-of-life care. Open Med 3:e101-e110, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ray A, Block SD, Friedlander RJ, et al. : Peaceful awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 9:1359-1368, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silveira MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM: Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med 362:1211-1218, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apatira L, Boyd EA, Malvar G, et al. : Hope, truth, and preparing for death: Perspectives of surrogate decision makers. Ann Intern Med 149:861-868, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wendler D, Rid A: Systematic review: The effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med 154:336-346, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MHN, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol 25:715-723, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heyland DK: Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med 173:778-787, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA: Achieving goal-concordant care: A conceptual model and approach to measuring serious illness communication and its impact. J Palliat Med 21:S17-S27, 2017. (suppl 2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolle S, Teno J: Counting POLST form completion can hinder quality|Health Affairs Blog. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180709.244065/full/

- 28.Stephens CE, Hunt LJ, Bui N, et al. : Palliative care eligibility, symptom burden, and quality-of-life ratings in nursing home residents. JAMA Intern Med 178:141-142, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geerse OP, Lamas DJ, Sanders JJ, et al. : A qualitative study of serious illness conversations in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 22:773-781, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown B, Gude WT, Blakeman T, et al. : Clinical performance feedback intervention theory (CP-FIT): A new theory for designing, implementing, and evaluating feedback in health care based on a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Implement Sci 14:40, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navathe AS, Emanuel EJ: Physician peer comparisons as a nonfinancial strategy to improve the value of care. JAMA 316:1759-1760, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel MS, Volpp KG, Asch DA: Nudge units to improve the delivery of health care. N Engl J Med 378:214-216, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel MS, Volpp KG, Small DS, et al. : Using active choice within the electronic health record to increase influenza vaccination rates. J Gen Intern Med 32:790-795, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manz CR, Parikh RB, Evans CN, et al. : Integrating machine-generated mortality estimates and behavioral nudges to promote serious illness conversations for cancer patients: Design and methods for a stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials 90:105951, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vries HD, Europe R, Elliott MN, et al. : Using pooled kappa to summarize interrater agreement across many items. Field Methods 20:272-282, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearce N: Analysis of matched case-control studies. BMJ 352:i969, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mascha EJ, Sessler DI: Equivalence and noninferiority testing in regression models and repeated-measures designs. Anesth Analg 112:678-687, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, et al. : Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: Extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA 308:2594-2604, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. : Defining advance care planning for adults: A consensus definition from a multidisciplinary delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 53:821-832.e1, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, et al. : Effect of a patient and clinician communication-priming intervention on patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 178:930-940, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lohr KN, Zebrack BJ: Using patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice: Challenges and opportunities. Qual Life Res 18:99-107, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Légaré F, Witteman HO: Shared decision making: Examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff (Millwood) 32:276-284, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR: Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 9:1086-1098, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heyland DK, Dodek P, You JJ, et al. : Validation of quality indicators for end-of-life communication: Results of a multicentre survey. CMAJ 189:E980-E989, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Individual participant data will not be available. The study protocol is available (Protocol). No other documents will be available. Reason: The study involves extensive electronic medical record data for all trial participants that cannot be accessed outside of the health system.