PURPOSE:

AccessHope is a program developed initially by City of Hope to provide remote subspecialist input on cancer care for patients as a supplemental benefit for specific payers or employers. The leading platform for this work has been an asynchronous model of review of medical records followed by a detailed assessment of past and current management along with discussion of potential future options in a report sent to the local oncologist. This summary describes an early period of development and growth of this service, focusing on cases of lung cancer, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS:

Cases were primarily identified by a trigger list of cancer diagnoses that included non–small-cell lung cancer and small-cell lung cancer. After medical records were obtained, a summary narrative was provided to a thoracic oncology specialist who wrote a case review sent to the local physician, followed by a direct discussion with the recipient. We focused on feasibility as measured by case volumes, the rates of concordance between the subspecialist reviewer with the local team, and cost savings from recommended changes, using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS:

From April 2019 to November 2020, 110 cases were reviewed: 55% male, median age 62.5 years (range, 33-92 years); 82% non–small-cell lung cancer (12% stage I or II, 16% stage III, and 57% stage IV), and 17% small-cell lung cancer (4% limited and 14% extensive). Median turnaround time for report send-out was 5.0 days. The review agreed with local management in 79 (72%) cases and disagreed in 31 (28%) cases; notably, specific additional recommendations were associated with evidence-based anticipated improvements in efficacy in 76 cases (69%) and improvement in potential for cure in 14 cases (13%). Recommendations leading to cost savings were identified in 14 cases (13%), translating to a projected cost savings of $19,062 (USD) per patient for the entire cohort of patient cases reviewed.

CONCLUSION:

We demonstrate the feasibility of completing a rapid turnaround of cases of lung cancer either patient-initiated for review or prospectively triggered by diagnosis and stage. This program of asynchronous second opinions identified evidence-based management changes affecting current treatment in 28% and potential improvements to improve care in 92% of patients, along with cost savings realized by eliminating low-value interventions.

INTRODUCTION

With advances in cancer care arriving at an escalating pace, additional input from second opinions may provide invaluable insight, particularly if conferred by a subspecialist in a limited area of oncology. Reviews of second opinions in general,1,2 as well as telemedicine-based second opinions in particular,3 reveal that they are sought to provide additional certainty, supplemental communication, more personalized attention, and potential identification of novel management options; diagnostic or therapeutic discrepancies are identified in a significant fraction (2%-69%) of cases.1-3

AccessHope is a subsidiary of City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center that provides remote subspecialist input on wide range of different cancer subtypes, most commonly offered as a supplemental employee benefit for specific companies or health care payers. Evaluations are commonly conducted as an asynchronous review of medical records, without patient travel required, followed by a detailed assessment of prior and current management along with recommendations for subsequent testing and treatment options. Importantly, patients may seek a remote opinion, but most cases are proactively identified on the basis of the anticipated impact of potential management changes on the basis of the diagnosis and stage of a cancer for which the prognosis is often unfavorable and practice patterns are dynamic. The reports are provided directly to the primary medical team, a strategy providing subspecialist guidance that typically incorporates treatment plans amenable to ongoing management close to their home and support system.

The feasibility of such an approach has yet to be clarified, but restrictions on mobility and direct access as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic only made it more challenging for people to seek additional opinions in person, raising the appeal of a remote alternative that offers an individualized assessment for patients.

The purpose of this descriptive analysis is to retrospectively evaluate the cohort of patients with lung cancer whose cases were reviewed during the early period of this program, from April 2019 through November 2020. The focus of this work is on case volumes, rates of concordance versus alternative management recommendations compared with the plans from the local medical team, projected improvements in outcomes that may include cost savings, and observed clinical patterns that may be compared with published series from clinical trials. This work demonstrates the feasibility and growth of the program despite the practical challenges introduced by the COVID-19 pandemic and reveals opportunities for its ongoing evolution as AccessHope transitions into a network of geographically decentralized tertiary care institutions.

METHODS

Identification of Cases

Client companies or medical payers (see Appendix Fig A1, online only for distribution) retain AccessHope to offer expert reviews for their insured employees and dependents, in which AccessHope provides detailed reviews that may become eligible through either of two paths.

First, cases may be identified proactively through the Accounfig Precision Oncology (APO) program on the basis of prior authorizations and claims submissions identifying the top 20% of complex cancers, to address significant variability in treatment patterns and outcomes. This proactive process is designed to expedite identification of cases for which timely input is critical, including diagnosed lung cancer across many stages. Alternatively, a limited subset of client companies offers a program called Expert Advisory Review, a patient-initiated service in which participants with any cancer diagnosis can request a review of their case materials and request answers to specific questions so that their reviewer can suggest management options to their treating physician.

This review includes cases of non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), or other chest malignancies that were conducted from April 2019 through November 2020.

Case Review and Reporting Process

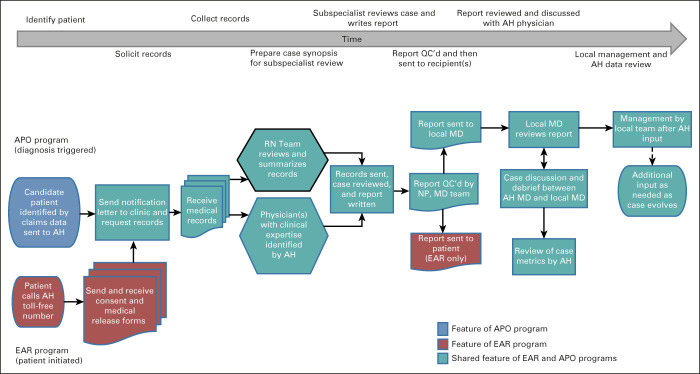

The process of collecting data, performing the case review, and sending completed reports is summarized in Figure 1. Once needed medical records were collected for each case, they were reviewed by an oncology specialist nurse who developed a synopsis of the chronology and key data; the Clinical Operations team then worked with an Access Hope oncologist as needed to identify the most relevant clinical expert(s) in hematology or oncology, radiation oncology, surgery, or potentially other experts who serve as active faculty at City of Hope to review the case. The narrative summary and original records are sent securely to the expert(s), who offer written commentary on the workup, prior therapy, current plans, and future management options for the patient.

FIG 1.

AccessHope work flow. Flowchart depicting the multistep process of case identification, intake of medical records, summary of a case narrative, distribution of the case to the subspecialist expert, editing of the report, delivery of the case to the recipient(s), subsequent case discussion with the local oncologist, and review of case metrics to assess the clinical and financial impact of each case. AH, AccessHope; APO, Accounfig Precision Oncology; EAR, Expert Advisory Review; MD, physician; NP, AccessHope nurse; QC, quality control; RN, AccessHope registered nurse.

Upon completion, reports undergo review and editing for quality control by a nurse practitioner followed by an additional hematology or oncology specialist on the AccessHope team before they are sent to the local physician in all cases, with a copy also sent to the requesting patient for Expert Advisory Review cases. The key components of a completed report are illustrated in Appendix Figure A2 (online only). For APO cases, the AccessHope team coordinates a call between an AccessHope physician and the oncologist or other leading member of the treatment team coordinating the patient's care. This is pursued to directly discuss the report and interval events in the patient's care, as well as to facilitate outreach back to AccessHope by the local physician in the future in the event that any further communication could be helpful.

Assessing Metrics to Case Reviews

Metrics for each case were assessed in multiple dimensions, generally by a team of two or more physicians reviewing case reports and agreeing on an assignment of these metrics on the basis of defined criteria enumerated in the Appendix 1. The level of concordance of the expert reviewer with the planned management ranged from agreement (without additional recommendations) to disagreement, with significant recommendations. Notably, all categories other than agreement include additional recommendations anticipated to improve outcomes for the patient's care.

In addition, recommendations for a change in diagnosis or stage, treatment, additional testing or specifically precision medicine, a clinical trial, or other management recommendations such as bone-directed therapy were tabulated. Humanistic outcomes such as an anticipated reduction in side effects or long-term complications, improvement in patient support or distress, and potential improvement in anticipated survival or cure rate on the basis of evidence-based recommendations were recorded. Finally, anticipated cost savings from overutilization or inappropriate utilization of services (such as imaging or treatment interventions) not supported as an appropriate standard of care was identified. Cost savings were valued (in US dollars) on the basis of differences in the cost of the plan by the treatment team compared with that proposed by Access Hope. In keeping with established practices,4 we relied on the methodology for measuring return on investment for oncology pathways. Specifically, savings are based on a payer perspective and account for direct costs associated with treatments and procedures, whereas for chemotherapy or supportive care agents, savings are associated with the drug reimbursement. Costs are based on Medicare reimbursement fees and adjusted with a conversion factor for private carriers. Cost savings are only captured for future activities; assessments or treatments that were delivered and completed were not subject to savings.

Project Scope and Statistics

This project was submitted to the institutional review board and determined to be exempt.

The aims of this analysis are as follows:

To assess the changes in case volumes and characterize the stage and histologic distribution of remote consultations for lung cancer over time during the interval noted above.

To evaluate the level of concordance of subspecialist expert recommendations in remote consults on cases compared with management pursued or proposed by the local medical team for the case.

To identify the proportion of patients with anticipated improvements in clinical outcomes.

To identify trends in patterns on the basis of aggregate review of cases, including molecular marker testing, surveillance with positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), and marginal performance status limiting treatment options.

These variables were characterized using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS

Feasibility of Reviews and Case Volumes

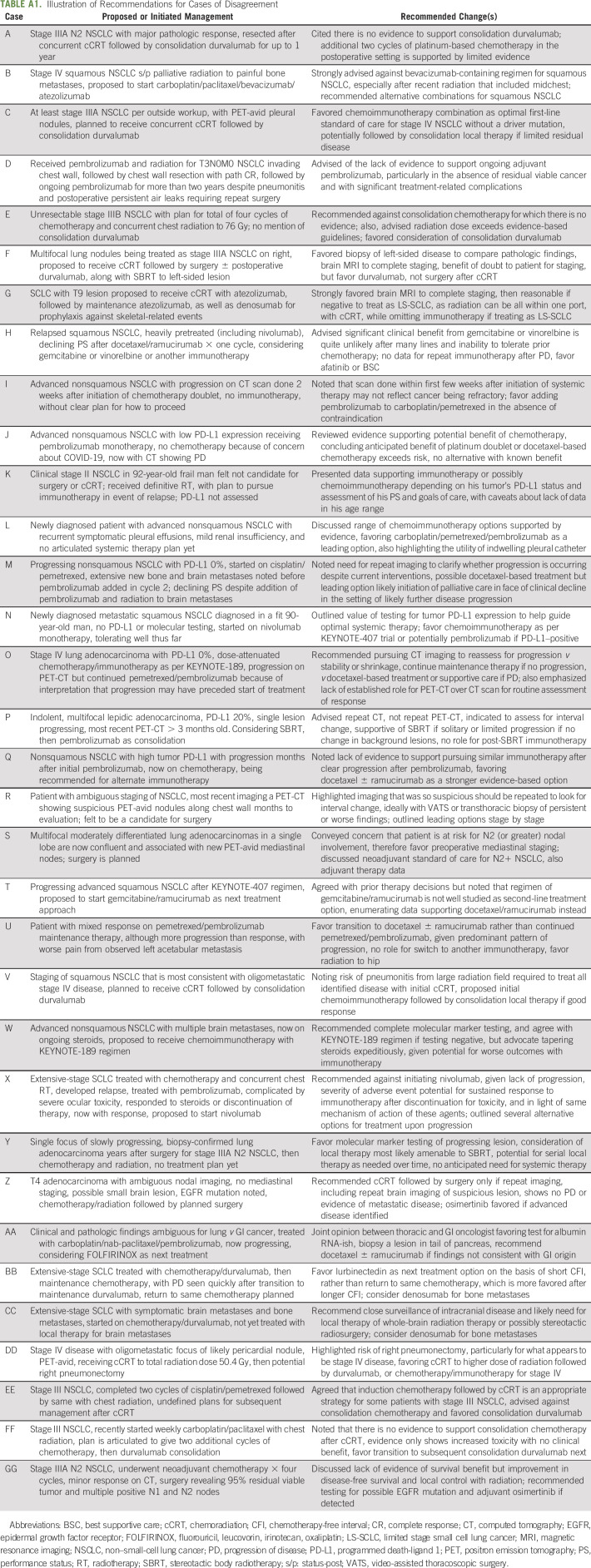

A total of 110 cases with a diagnosis of NSCLC or SCLC were reviewed during the interval being evaluated, the majority (107 [97%]) coming through the APO program. As shown in Figure 2, case volume increased over time, despite the disruption of workflows and many health care processes and workups in the spring of 2020, albeit with marked variation month to month because of variance in client company case input. The characteristics of patients for whom reviews were conducted are shown in Table 1.

FIG 2.

Case volume over time: there was a clear increase over time, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, although marked variability from month to month was a product of changes in some client company priorities.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

The median turnaround time from receipt of the case materials by the expert to the report being sent to the local oncologist or other intended recipient was 5.0 days. Multidisciplinary reviews were conducted for 3 of 110 cases (3%).

At the time of the case review, 14 (13%) patients had not initiated treatment for their current treatment stage and setting, 68 (62%) were receiving or had received their primary treatment without progression, and 28 (25%) had disease progression and were receiving or planned to receive second line or later treatment.

Review Outcomes and Case Metrics

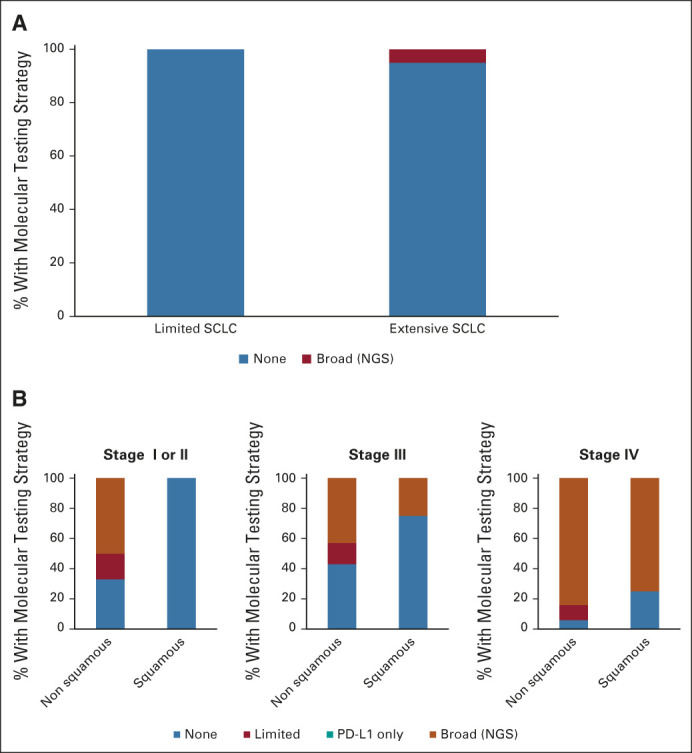

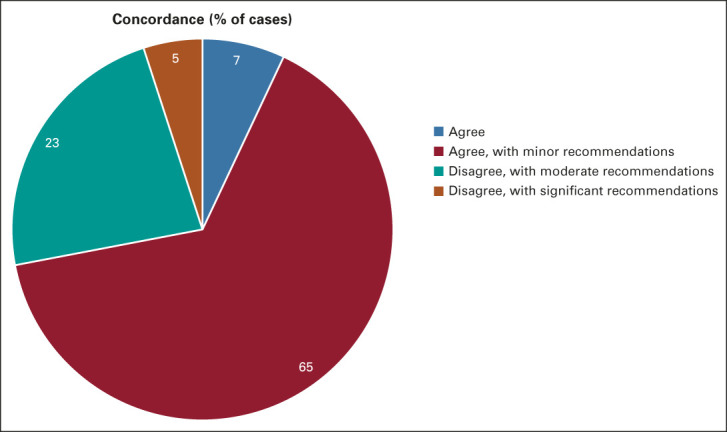

The distribution of concordance by the AccessHope expert with the recommendations from the local oncology team for the cohort of cases is illustrated in Appendix Figure A3. The most common level of concordance was agreement, with minor recommendations in 71 cases (65%); followed by disagreement, with moderate recommendations in 25 cases (23%); agreement, with no recommendations in eight cases (7%); and disagreement, with significant recommendations in six cases (5%). The recommendations were associated with evidence-based anticipated improvements in efficacy in 76 cases (69%) and improvement in potential for cure in 14 cases (13%, only feasible in patients with curable disease). Examples of suggested changes for the 31 cases (28%) with disagreement are briefly summarized in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

Recommendations accompanied by cost savings were identified in 14 cases (13%), with a total cost savings of $149,776 (USD) per patient within this subset, or $19,062 (USD) per patient for the full cohort of cases reviewed.

Specific Features of Reviews

Molecular testing patterns

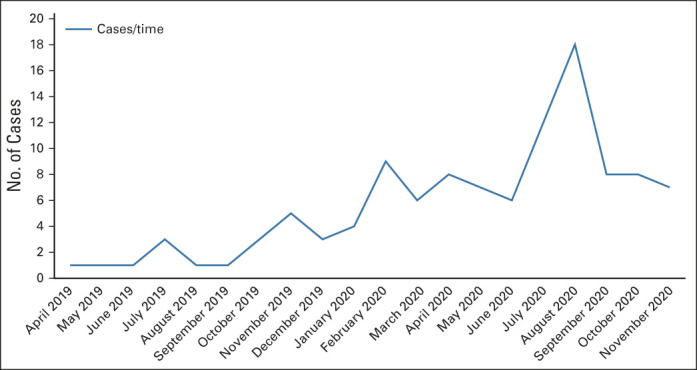

As shown in Figure 3, molecular marker testing was rare in SCLC, ordered for only one of 19 (5%) cases of SCLC, consistent with the lack of any clear role for it in this setting.5 For patients with NSCLC, molecular marker testing was more commonly ordered for patients with nonsquamous compared with squamous NSCLC at all stages (66% and 0% for early-stage nonsquamous and squamous NSCLC, respectively; 57% v 25% for stage III nonsquamous and squamous NSCLC, respectively; 94% v 75% for stage IV nonsquamous NSCLC, respectively) and most commonly ordered for stage IV NSCLC, all consistent with clinical guidelines.5

FIG 3.

Molecular marker testing patterns by local oncologists by lung cancer histology and clinical setting for SCLC and NSCLC. Cases are categorized as SCLC (limited [n = 4]; extensive [n = 14]) and NSCLC (early stage, squamous [n = 7]; nonsquamous [n = 6]; stage III, squamous [n = 4]; stage III, nonsquamous [n = 14]; stage IV, squamous [n = 8]; stage IV, nonsquamous [n = 53]). Testing is categorized as none, limited mutation panel, PD-L1 expression only, or broad testing, eg, NGS. NGS, next generation sequencing; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1.

Routine surveillance with PET-CT

Among the cohort of 110 cases, surveillance PET-CT scans were identified as the prevailing imaging studies to assess ongoing treatment response in 12 cases (11%). In these cases, the reviews noted that there is no evidence demonstrating that PET-CT offers a significant incremental benefit in terms of clinical outcomes and that routine monitoring of response by CT may be an appropriate alternative.

Frail or marginal performance status

A total of 21 patients (19%) were identified by their local cancer care team as having a poor performance status, as reflected in clinic notes, limiting treatment considerations relative to standard of care for more fit patients. Although this cohort included nine patients (8%) age 80 years or older, only three (33%) of this subset were noted to be frail enough on the basis of clinic notes to limit the treatment recommendations.

DISCUSSION

The program developed by AccessHope represents a new model for cancer care that remotely incorporates input from a subspecialist oncologist into a report to a patient's local medical team, thereby enabling delivery of optimal care without an expectation that a patient present to a tertiary care center. Our experience over slightly more than 1.5 years demonstrates that this model is not only feasible to implement but revealed increasing uptake over that time, despite disruption of workflows and many health care processes throughout much of 2020.6

Reviewing the results of these reports in aggregate demonstrated that although our expert agreed with the general management approach in the majority (72%) of cases, 92% of cases included recommendations to refine management, largely on the basis of strategies for surveillance, subsequent treatment options, surveillance, and/or supplemental evidence-based recommendations such as bone-directed therapy for patients with bone metastases. Two-thirds of cases included recommendations for current or future care associated with an anticipated improvement in efficacy, and 13% included a proposed plan associated with improved chance of cure. Moreover, even when commenting on past management, identifying teaching points for completed therapies is prone to improve outcomes for other patients treated by the same physician; similarly, outlining and suggesting optimal subsequent therapy options for a patient is not recorded as discordant with current therapy but stands to improve that patient's outcome later, while also providing guidance that can also be translated to many other patients. Overall, for more than one of every four cases, expert recommendations proposed an alternative management approach for current treatment associated with a significantly superior survival on the basis of available data. Moreover, by recommending against low-value imaging or treatments that are not concordant with clinical guidelines for that setting, marked cost savings could be identified that averaged more than $19,000 (USD) per patient.

Surveying the broad range of case materials submitted also affords an opportunity to understand the features of the patient population and clinical decision making of a diverse array of oncology practice across the United States. Through this lens, we observed that PET scan–based imaging was pursued or planned to assess for response or progression in 11% of cases despite it having no demonstrated incremental benefit over CT scan surveillance. We noted that 19% of patients were limited by marginal or poor performance status for which individualized judgment is left to fill the void of scant clinical evidence; importantly, this proportion is based on local assessment and includes only the subset of patients for whom their functional status was specifically documented within clinic notes as poor candidates for standard therapies favored for more fit patients. Assessment of molecular testing patterns revealed that testing in this broad sample far exceeded that reported in some prior reports7-9; overall, even very recent broad data sets have shown that community-based molecular marker testing follows clinical guidelines in < 50% of cases.9 Consistent with clinical guidelines, molecular testing was far more likely to be ordered for patients with NSCLC than SCLC, more commonly ordered for advanced- compared with early-stage disease, and more likely to be ordered in patients with nonsquamous versus squamous NSCLC histology.

We must also acknowledge the limitations of this work. First, this analysis represents a growing but still relatively small cohort that limits our ability to draw strong conclusions about patient features or practice patterns; our ability to see these with greater resolution will undoubtedly improve as the size of this cohort grows with the trajectory of this program. Findings are also gleaned from a population of patients who are not only insured but have an employer or insurance payer providing a high level of support; the observations cannot be extrapolated to a broader population of uninsured or underinsured patients in the United States. In addition, the expert input has been provided by only a limited group of experts in this early interval of the program. Given the value in obtaining input from a plurality of experts as well as the steadily growing case volume, the AccessHope program is now increasingly distributing cases not only among City of Hope faculty but also to faculty that include two additional National Cancer Institute–designated cancer centers (Northwestern Medicine and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) as foundational partners, with others planned, to create a geographically diverse network of experts reviewing an escalating number of candidate cases.

Importantly, we do not directly assess patient or local physician satisfaction, nor the rates at which articulated recommendations have been followed or clinical outcomes associated with them. AccessHope is striving to pursue follow-up at one or more defined time points, which should enable us to assess which recommendations have been pursued in the interval since the initial review was submitted.

Those interested in these services may question whether this work constitutes telemedicine that would require physicians to be licensed by the state in which the patient is located. AccessHope provides educational and support services to the local treating physicians who are licensed in the state where the patient resides and who provide direct care for the patient. AccessHope does not establish a doctor-patient relationship, provide care, or practice telemedicine. Therefore, although patients may be located throughout the United States, there is no requirement for AccessHope physicians to be licensed in the state in which a specific patient resides.

Multiple mechanisms for second opinions exist to provide reassurance to patients and potentially their care team, although the experience of many of these programs has not been summarized and published. As one option with some similarities to AccessHope, Meyer et al10 describe their experience with an asynchronous patient-initiated second opinion service (Best Doctors) covering all aspects of medicine that included 588 patients with hematology or oncology diagnoses, with opinions in this subset estimated to have moderate or major clinical impact in 38% of cases. Another option that provides a multidisciplinary approach is virtual tumor boards or case conferences, which have been pursued for testicular cancer,11 sarcoma,12 and lung cancer,13 with success in improving care while overcoming geographic barriers.

AccessHope has prioritized proactive identification of cases with high potential for impact by triggering cases on the basis of diagnosis and stage, with a rationale that many patients and oncologists may be unaware of when supplemental subspecialist input could improve outcomes. Only 3% of our reviewed cases with lung cancer were patient-initiated, likely reflecting the disinclination of so many patients with cancer, often particularly patients with lung cancer, to seek a second opinion.14

The AccessHope program is also designed to minimize turnaround time and maximize flexibility to accommodate a variable volume of patients with a potentially wide array of cancer diagnoses. Although a regular cadence of multidisciplinary tumor boards or case conferences could potentially provide support for patients with specific tumor types, this incurs a delay before feedback is available, cannot be readily offered across a wide range of tumor types simultaneously, and is challenging to modulate in response to variable patient volumes over time.

As new employers contract with this AccessHope network, this program can offer oncologists in practice the input and support of a subspecialist while preserving the autonomy of the local medical team, without requiring patient travel, and keeping the patient's care close to home.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful for the critical data support from Abhishek Kumar from AccessHope, as well as to Mark Stadler, Melissa Gilkerson, and Bridget Davis of AccessHope for critical review of the manuscript content.

APPENDIX 1. APPENDIX 1. Supplemental Materials

Definitions of Case Metrics

Agree

The clinical expert agrees with current management and has no suggestions for clinically significant changes in management. This category should only be selected when outcome of review is validation of current care.

Agree, with minor recommendations

The clinical expert has recommendations for additional tests, interventions, or changes in management that are not associated with significant evidence-based improvements in cancer outcome and may be secondary to anticancer treatment and/or on the basis of preference.

Disagree, with moderate recommendations

The clinical expert recommends a change in anticancer therapy that is anticipated to be associated with an evidence-based, clinically significant improvement in cancer outcome, whether greater efficacy or reduced toxicity or both; OR the clinical expert recommends a management plan in the absence of any default treatment recommendations by the local medical team.

Disagree, with significant recommendations

The clinical expert recommends a change in anticancer therapy that is anticipated to be associated with an evidence-based, clinically significant improvement in cancer outcome that is provided as an alternative to a treatment plan by the local medical team that is associated with greater anticipated harm than benefit or represents a treatment plan clearly below the standard of care for that clinical setting.

Records Requested

Medical records including most recent three clinic notes from relevant specialists (as applicable), pathology reports including all molecular marker testing, and initial and most recent imaging reports for each case were requested as pdf files, although an original history and physical examination and any additional relevant records were also welcomed. Imaging and pathology were reviewed on the basis of reports and not direct review of source materials.

FIG A1.

Geographic distribution of client companies working with AccessHope. At the present time, AccessHope works with 43 companies in 21 states to cover approximately 2.3 million lives.

FIG A2.

Content of Sample Report from AccessHope. (A) Summary data on patient, then local clinical team, name of expert reviewer, date of review, followed by brief synopsis of case by expert physician, and numbered points of commentary on workup and treatment thus far. (B) Continued numbered points of commentary on treatment and potential alternatives, surveillance and subsequent management options, as well as supportive care, followed by suggested clinical trial options, as applicable. (C) Numbered references cited in review commentary, followed by narrative summary of case as prepared by nurse. (D) Additional narrative summary by nurse, followed by chronologic summary of case data and medical history (continues for additional pages). (E) Program disclaimers. (F) Introduction to expert reviewer, with biography. (G) The summary of education, training, and papers authored by the expert reviewer (continues for additional pages).

FIG A3.

Concordance with local oncologist or medical team. The breakdown of measures of concordance or disagreement with diagnosis and current or proposed management as defined by AccessHope. Note that agree, with minor recommendations includes recommendations for changes in management applied to past or future care. Dr Howard West's image is visible and recognizable within Appendix Figure A3 (online only), which illustrates the faculty biography portion of the provided case report. Dr West has provided his explicit consent for his likeness to be included in the context of this publication.

TABLE A1.

Illustration of Recommendations for Cases of Disagreement

Howard (Jack) West

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Merck, Takeda, Mirati Therapeutics, Regeneron

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Takeda, Mirati Therapeutics, Regeneron

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda, Merck, AstraZeneca

Yuan Angela Tan

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Merck, Takeda, Mirati Therapeutics, Regeneron, Merck, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Takeda, Mirati Therapeutics, Regeneron

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda, Merck, AstraZeneca

Afsaneh Barzi

Leadership: Cardiff Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merrion, bioTheranostics, Bayer Technology System, Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca

Research Funding: Bayer (Inst), Merck (Inst)

Debra Wong

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Sanofi/Aventis, Blueprint Medicines, Regeneron, Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: Pfizer

Research Funding: BioMed Valley Discoveries (Inst), Merck Serono (Inst), Merck Sharp & Dohme (Inst), ARMO BioSciences (Inst), AstraZeneca/MedImmune (Inst), Kura Oncology (Inst), Regeneron (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), FSTAR (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Enzychem Lifesciences (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Elevar Therapeutics (Inst)

Robert Parsley

Employment: AccessHope, Optum

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

Because of legal restrictions and the proprietary nature of several of the processes included, data represented in this work cannot be shared beyond that which is included here or published elsewhere by representatives of AccessHope.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Howard (Jack) West, Yuan Angela Tan

Administrative support: Howard (Jack) West, Todd Sachs

Provision of study materials or patients: Howard (Jack) West

Collection and assembly of data: Howard (Jack) West, Yuan Angela Tan, Afsaneh Barzi, Robert Parsley

Data analysis and interpretation: Yuan Angela Tan, Afsaneh Barzi, Debra Wong, Todd Sachs

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Novel Program Offering Remote, Asynchronous Subspecialist Input in Thoracic Oncology: Early Experience and Insights Gained During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Howard (Jack) West

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Merck, Takeda, Mirati Therapeutics, Regeneron

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Takeda, Mirati Therapeutics, Regeneron

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda, Merck, AstraZeneca

Yuan Angela Tan

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Genentech/Roche, Merck, Takeda, Mirati Therapeutics, Regeneron, Merck, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Takeda, Mirati Therapeutics, Regeneron

Speakers' Bureau: Takeda, Merck, AstraZeneca

Afsaneh Barzi

Leadership: Cardiff Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merrion, bioTheranostics, Bayer Technology System, Daiichi Sankyo/Astra Zeneca

Research Funding: Bayer (Inst), Merck (Inst)

Debra Wong

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Sanofi/Aventis, Blueprint Medicines, Regeneron, Pfizer

Speakers' Bureau: Pfizer

Research Funding: BioMed Valley Discoveries (Inst), Merck Serono (Inst), Merck Sharp & Dohme (Inst), ARMO BioSciences (Inst), AstraZeneca/MedImmune (Inst), Kura Oncology (Inst), Regeneron (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), FSTAR (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Astellas Pharma (Inst), Enzychem Lifesciences (Inst), Lilly (Inst), Elevar Therapeutics (Inst)

Robert Parsley

Employment: AccessHope, Optum

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hillen MA, Medendrop NM, Daams JG, et al. : Patient-driven second opinions in oncology: A systematic review. Oncologist 22:1197-1211, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruetters D, Keinki C, Schroth S, et al. : Is there evidence for a better health care for cancer patients after a second opinion? A systematic review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 142:1521-1528, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mao A, Meng Y, Qang Q, et al. : Outcome assessment for a telemedicine-based second opinion program for Midwest China. Inquiry 57:0046958020968788, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreys ED, Koeller JM: Documenting the benefits and cost savings of a large multistate cancer pathway program from a payer’s perspective. JCO Oncol Pract 9:e241-e249, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) : Clinical Guidelines in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (version 3.2021). bit.ly/NCCNNSCLC [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakouny Z, Paciotti M, Schmidt AL, et al. : Cancer screening tests and cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol 7:458-460, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singal G, Miller PG, Agarwala V, et al. : Association of patient characteristics and tumor genomics with clinical outcomes among patients with non-small cell lung cancer using a clinicogenomic database. JAMA 321:1391-1399, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gierman HJ, Goldfarb S, Labrador M, et al. : Genomic testing and treatment landscape in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC) using real-world data from community oncology practices. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019. (suppl; abstr 1585) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robert NJ, Nwokeji ED, Espirito JL, et al. : Biomarker tissue journey among patients (pts) with untreated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (mNSCLC) in the US Oncology Network community practices. J Clin Oncol 38, 2021. (suppl 15; abstr 9004) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer AN, Singh H, Graber Ml: Evaluation of outcomes from a national patient-initiated second-opinion program. Am J Med 128:1137.e25-33, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zengerling F, Hartmann M, Heidenreich A, et al. : German second opinion network for testicular cancer: Sealing the leaky pipe between evidence and clinical practice. Oncol Rep 31:2477-2481, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan M, Yu J, Sidhu M, et al. : Impact of a virtual multidisciplinary sarcoma case conference on treatment plan and survival in a large integrated healthcare system. JCO Oncol Pract 17:e1711-e1718, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gebbia V, Guarani A, Piazza D, et al. : Virtual multidisciplinary tumor boards: A narrative review focused on lung cancer. Pulm Ther 7:295-308, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peier-Ruser KS, von Greyerz S: Why do cancer patients have difficulties evaluating the need for a second opinion and what is needed to lower the barrier? A qualitative study. Oncol Res Treat 41:769-773, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Because of legal restrictions and the proprietary nature of several of the processes included, data represented in this work cannot be shared beyond that which is included here or published elsewhere by representatives of AccessHope.