Abstract

The rapid geographic spread of COVID-19, to which various factors may have contributed, has caused a global health crisis. Recently, the analysis and forecast of the COVID-19 pandemic have attracted worldwide attention. In this work, a large COVID-19 data set consisting of COVID-19 pandemic, COVID-19 testing capacity, economic level, demographic information, and geographic location data in 184 countries and 1241 areas from December 18, 2019, to September 30, 2020, were developed from public reports released by national health authorities and bureau of statistics. We proposed a machine learning model for COVID-19 prediction based on the broad learning system (BLS). Here, we leveraged random forest (RF) to screen out the key features. Then, we combine the bagging strategy and BLS to develop a random-forest-bagging BLS (RF-Bagging-BLS) approach to forecast the trend of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, we compared the forecasting results with linear regression (LR) model,

-nearest neighbors (KNN), decision tree (DT), adaptive boosting (Ada), RF, gradient boosting DT (GBDT), support vector regression (SVR), extra trees (ETs) regressor, CatBoost (CAT), LightGBM (LGB), XGBoost (XGB), and BLS.The RF-Bagging BLS model showed better forecasting performance in terms of relative mean-square error (RMSE), coefficient of determination (

-nearest neighbors (KNN), decision tree (DT), adaptive boosting (Ada), RF, gradient boosting DT (GBDT), support vector regression (SVR), extra trees (ETs) regressor, CatBoost (CAT), LightGBM (LGB), XGBoost (XGB), and BLS.The RF-Bagging BLS model showed better forecasting performance in terms of relative mean-square error (RMSE), coefficient of determination (

), adjusted coefficient of determination (

), adjusted coefficient of determination (

), median absolute error (MAD), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) than other models. Hence, the proposed model demonstrates superior predictive power over other benchmark models.

), median absolute error (MAD), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) than other models. Hence, the proposed model demonstrates superior predictive power over other benchmark models.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, broad learning system (BLS), coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) testing capacity, COVID-19, random forest (RF), time-series forecasting

I. Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1], has high transmissibility [2]. This new infectious disease spread worldwide in less than half a year in 2020, causing devastation to the human population. The outbreak of COVID-19 has progressed with a tremendous impact on the economic [3], social behavior [4], environment [5], climate [6], etc. Evolutionary virologist found bats may be the origins of SARS-CoV-2 [7], which has a long evolutionary history [8]. However, at present, there is no unified scientific conclusion on the origin of SARS-CoV-2 [9]. Although most countries launched emergency responses early in the outbreak, the COVID-19 still swiftly spread from metropolitan areas to urban areas, from countries to countries. By September 30, 2020, more than 200 countries had been affected, with major outbreaks in the United States, India, Brazil, Russia, Colombia, Peru, and others. A total of 34488636 COVID-19 cases and 1026176 deaths were reported worldwide [10] and more than 60% of the global population went into coronavirus lockdown [11]. As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) set COVID-19 to the highest crisis alert level by declaring the COVID-19 outbreak a global pandemic [12].

The tremendous number of COVID-19 cases may be attributable to multiple factors [13], [14]. Presymptomatic and asymptomatic patients play a key role in the spread of COVID-19 [15], [16]. Confirmed COVID-19 cases are mostly quarantined or self-isolated [17], while presymptomatic and asymptomatic patients form a large group of unregistered patients, who can move freely and infect close contacts easily [18]. The population movement of a large group of presymptomatic and asymptomatic patients is a key factor contributing to the spread of COVID-19 [13]. For a country or an area, sufficient COVID-19 tests can greatly decrease the number of unconfirmed infections, reduce the speed of disease transmission [19], and help in an accurate trend analysis to evaluate the pandemic situation [20]. Testing capacity is highly related to the number of confirmed cases and essential to elucidate the progress of the pandemic [19]. However, many low-income countries with comparatively weak health systems have limited resources for conducting massive tests and implementing public health measures to flatten the curve [20], [21]. Hence, the developing level of countries or regions is also related to the spread of COVID-19 [22]. The nonpharmacological interventions (NPIs) (or public health measures) have been the mainstay for containing the spread of COVID-19 [23]. Additionally, the geographical environment and climate also influence the spread of the COVID-19 [24]. In summarize, the spread of COVID-19 is a nonlinear complex dynamic progress greatly influenced by multiple factors, including COVID-19 testing capacity [19], geographical environment and climate [24], economic level [20], [22], human movements [25], NPIs (or public health measures) [26], air pollution [14], etc.

Machine learning has shown promising results in forecasting nonlinear dynamic progress and has been recognized as a potentially powerful tool for fighting COVID-19 [27]–[29]. However, the new pandemic still brings a number of new challenges, such as predicting the spread of the infection [30], making diagnoses and prognosis [31], [32], searching for treatments and vaccines [33], and social control [34]. Recently, estimates of COVID-19 patient volume are urgently required for local authorities to effectively manage the rising case for restricting the infections [35]. Generally, scholars develop epidemiological models for describing the spread of COVID-19. However, due to the complexity and the high level of uncertainty of the COVID-19, the standard epidemiological models always are a high-dimension nonlinear model with many unknown parameters, which are difficult to determine [25]. Hence, machine learning, which can, in principle, be utilized to build outbreak prediction models, has recently gained attention [36]. Machine learning always requires sufficient pandemic data for training. In contrast, most recent works reporting on using machine learning for a predictive purpose use small samples of only one or several areas, which may be biased and make predictions widely uncertain [37], [38]. Some researchers try to enhance the amount of data set by adding new features, such as social media [36], [39]. However, a large amount of media data inevitably contains a lot of false information or noise, which has to be filtered to create a training set [40]. As a result, it has posed great challenges in developing machine learning models for accurately and reliably forecasting the spread of COVID-19 [41]. Different countries have various attitudes toward COVID-19 and different public health measures. As a result, the daily changes of COVID-19 in different areas are highly volatile and variable, which makes it a challenging task to develop a prediction model, which can be applied to all the countries [37].

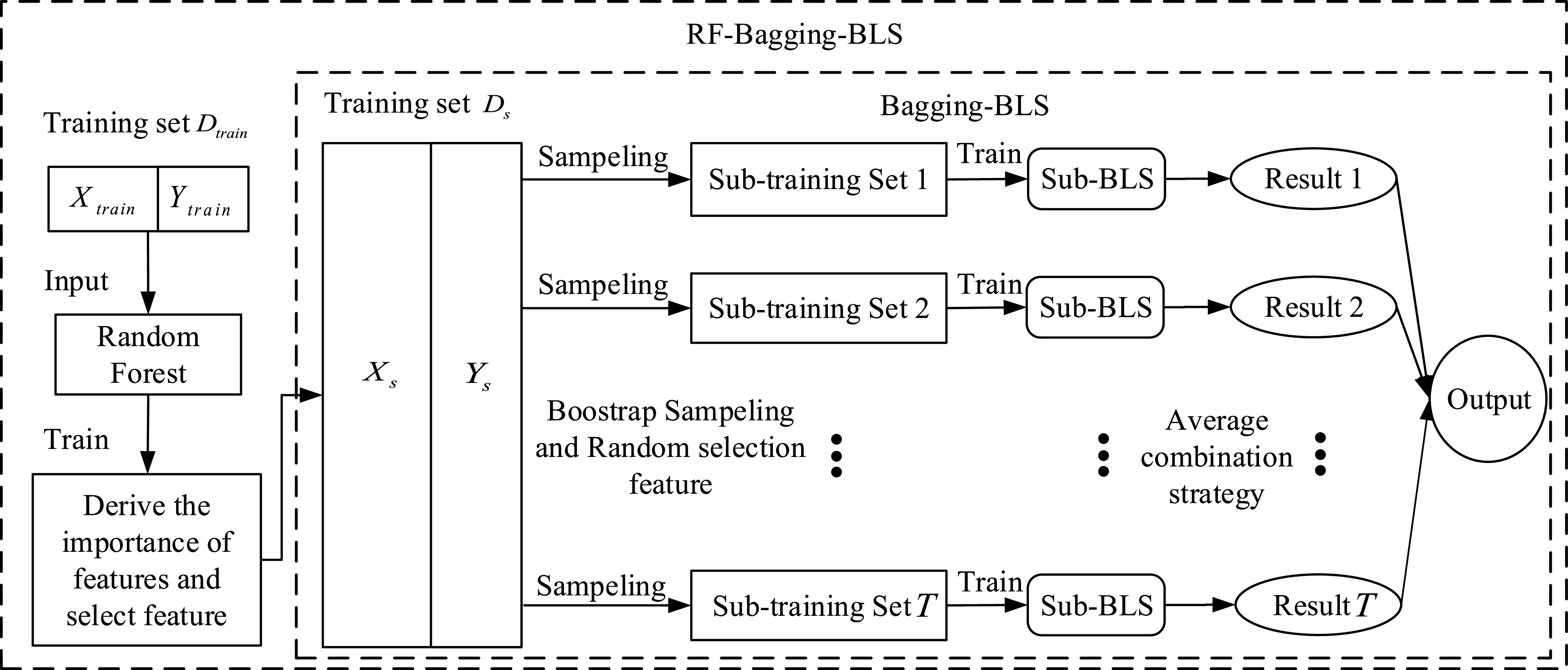

To alleviate the problem of lacking data and features, in this work, we developed a data set, including the pandemic data of 184 countries and 1241 areas with a total population of 7730029662, accounting for more than 95% of the global population. Briefly, these countries varied in population size, from less than one million population to more than one billion. Additionally, we collected COVID-19 testing data, economic level data, demographic information, and geographic information to establish a large data set to train machine learning models. A broad learning systems (BLSs) is a new proposed structure neural network without deep architecture [42] and shows good potential in time-series prediction [43]. In this work, we utilize random forest (RF), a popular ensemble learning method, to derive the importance score of each feature. Then, we adopted a set of most important features as a training data set. Combining with Bagging strategy and BLSs, we developed a random-forest-bagging BLSs (RF-Bagging-BLSs) model for predicting the spread of COVID-19 in 184 countries and 1241 areas. For justification, a number of machine learning models, including the linear regression (LR) model,

-nearest neighbors (KNN), decision tree (DT), support vector regression (SVR), adaptive boosting (Ada), RF, gradient boosting DT (GBDT), extra trees (ETs) regressor, CatBoost (CAT), LightGBM (LGB), XGBoost (XGB), and BLS, are adopted to compare with the proposed RF-Bagging-BLS model. Experimental results demonstrate that the RF-Bagging-BLS model outperforms other benchmark models by providing more accurate, stable and robust results.

-nearest neighbors (KNN), decision tree (DT), support vector regression (SVR), adaptive boosting (Ada), RF, gradient boosting DT (GBDT), extra trees (ETs) regressor, CatBoost (CAT), LightGBM (LGB), XGBoost (XGB), and BLS, are adopted to compare with the proposed RF-Bagging-BLS model. Experimental results demonstrate that the RF-Bagging-BLS model outperforms other benchmark models by providing more accurate, stable and robust results.

In this study, our main contributions are as follows.

-

1)

We establish a large data set with comprehensive information on COVID-19 spreading in 184 countries and 1241 areas.

-

2)

RF is adopted for feature importance analysis to improve BLS. A machine learning model, the RF-Bagging-BLS model, is proposed for forecasting the pandemic situation in various countries and areas around the world.

-

3)

We developed prediction models based on traditional machine learning, ensemble learning, and BLS.

-

4)

The new data set is also adopted for multiday-ahead forecasting to evaluate and verify the predictive power of these prediction models in different scenarios.

Our approaches and predictive outcomes can help contain the spread, flatten the curve, and possibly eliminate the current COVID-19 pandemic.

II. Literature Review

Forecasting the spread of COVID-19 in an area has received considerable critical attention. Based on a small data set including pandemic data of 5 countries, a comparative analysis of the predictive performance of machine learning and traditional models, including simple epidemiological and statistical models, is conducted. Two models, the adaptive network-based fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) and multilayered perceptron, showed promising results [28]. A nonauto regressive neural network is trained based on a small data set with 164 samples for global records and 90 scores of nine different countries for predicting the cumulative number of infections and death toll [44]. A modified stacked autoencoder is developed for real-time forecasting the confirmed cases in China from January 11 to Febuary 27, 2020 [45]. However, most of studies focused on prediction of the confirmed cases in just one or few countries, such as American [46], Brazilian [47], Canada [37], China [36], France [48], Hungary [38], Italy [49], India [50], Iran [51], Japan [46], South Korea [51], etc. [52].

The recurrent neural network (RNN) model is a commonly used model for predicting time series. A number of researchers used long short-term memory (LSTM) to build COVID-19 prediction models [53]–[55]. A modified LSTM model, trained on the 2003 SARS data, is utilized to predict the epidemic in China from January 23 to April 24, 2020 [54]. A data-driven estimation methods based on curve fitting and LSTM is developed for forecasting the number of COVID-19 cases in India [53]. Convolutional neural network (CNN) is also a good candidate for analyzing and predicting the spread of COVID-19 [55]. A model combining mechanistic and machine learning methodologies is developed for alleviating the lack of essential data and real-time forecasting in China [56]. Also, an improved adaptive neurofuzzy inference system (ANFIS) is proposed to estimate and forecast the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the upcoming ten days in China [57]. Ghamizi et al. [58] tried to combine the classical susceptible-exposed-infected-recovered (SEIR) model and machine learning to develop an SEIR-HCD model considering the impact of mitigation strategies. A hybrid machine learning method, which is based on a multilayered perceptron-imperialist competitive algorithm (MLP-ICA) and ANFIS, is used to predict the number of confirmed cases and mortality rate in Hungary [38].

III. Data Description and Forecasting Problem

A. Pandemic Data

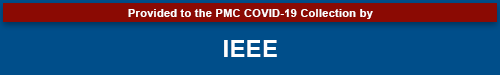

Based on several public data sets provided by John Hopkins University, local Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and other health authorities, we established a large COVID-19 epidemic research data set covering 184 countries and 1241 areas (cities, provinces, states, and other prefectures) spanning from December 8, 2019, to September 30, 2020. The cumulative number of confirmed cases in the 184 countries is shown in Fig. 1(a), while Table I summarizes the information of the COVID-19 data in the six continents. The data set includes the following contents.

-

1)

For each day

, the COVID-19 spreading data set utilized in this study includes the number of confirmed cases

, the COVID-19 spreading data set utilized in this study includes the number of confirmed cases

, fatalities

, fatalities

and recovered cases

and recovered cases

for 184 countries and 1241 areas (shown in Table I).

for 184 countries and 1241 areas (shown in Table I). -

2)

The information resultant from COVID-19 tests is a critical factor in ascertaining infection numbers. Additionally, sufficient testing capacity is essential to elucidate the progress of the pandemic [19]: the more tests, the high possibility to identify unconfirmed COVID-19 patients. Hence, test capacity

, representing the cumulative number of conducted test, is adopted as a feature for forecasting the spread of COVID-19. Note that the world’s COVID-19 test capacity increases dramatically in six months from less than 10,000 tests per day on March 1, 2020, to more than 4 million tests per day on September 30, 2020 [shown in Fig. 1(b)].

, representing the cumulative number of conducted test, is adopted as a feature for forecasting the spread of COVID-19. Note that the world’s COVID-19 test capacity increases dramatically in six months from less than 10,000 tests per day on March 1, 2020, to more than 4 million tests per day on September 30, 2020 [shown in Fig. 1(b)]. -

3)

Several studies suggest climate may be one factor that influences the spread of COVID-19 [24]. The environment in an area is closely related to the local location. Hence, the latitude

and longitude

and longitude

of each country and region are collected. Fig. 1(a) shows the geographic distribution of confirmed cases in these 184 countries over the world. Additionally, we divide each area into six categories according to the continent where it is located. Then, each region has another feature

of each country and region are collected. Fig. 1(a) shows the geographic distribution of confirmed cases in these 184 countries over the world. Additionally, we divide each area into six categories according to the continent where it is located. Then, each region has another feature

, where 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 represent Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Africa, and Oceania, respectively.

, where 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 represent Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Africa, and Oceania, respectively. -

4)

Most developed countries have advanced health systems and strong capacity to offset the economic and can apply population-level physical distancing measures to contain the spread of COVID-19, while undeveloped countries may have limited sources to fight with COVID-19. Hence, the economic situation of an area is also an influential factor [20]. According to the World Bank indicators, we divide countries into developed countries, developing countries, and undeveloped countries. Each region has a feature

, while 1, 2, and 3 stand for developed, developing, and undeveloped countries.

, while 1, 2, and 3 stand for developed, developing, and undeveloped countries. -

5)

The population

of each country or area is also adopted as a feature for forecasting the spread of COVID-19.

of each country or area is also adopted as a feature for forecasting the spread of COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

(a) Cumulative number of confirmed cases in 184 countries up to September, 2020. The size of the solid circles represents the number of confirmed cases. (b) Daily confirmed cases and daily COVID-19 tests over the world up to September 30, 2020.

TABLE I. Information on COVID-19 Data Released by 184 Countries in Six Continents Up to September 30, 2020.

| Continent | Countries (amount) | Areas (amount) | Population (in millions) | Confirmed cases | Recovered cases | Death toll | COVID-19 Tests | Mortality Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 45 | 802 | 4,465 | 10,632,594 | 8,926,323 | 194,702 | 134,266,412 | 1.8312 |

| Europe | 46 | 231 | 743 | 5,078,482 | 2,449,329 | 224,315 | 135,205,765 | 4.4170 |

| North America | 24 | 115 | 604 | 9,135,594 | 5,468,439 | 319,302 | 132,616,914 | 3.4952 |

| South America | 11 | 85 | 612 | 7,601,438 | 6,595,662 | 240,320 | 6,351,210 | 3.1616 |

| Africa | 54 | 0 | 1,265 | 1,481,929 | 1,227,334 | 35,863 | 11,189,231 | 2.4201 |

| Oceania | 4 | 8 | 39 | 29,510 | 27,098 | 922 | 8,661,117 | 3.1244 |

| Total | 184 | 1,241 | 7,730 | 33,959,547 | 24,694,185 | 1,015,424 | 428,290,649 | 2.9901 |

Here, public health intervention information is not included in this data set. Each country or even each prefecture in a country would have different control measures. For instance, in the USA, each state implement control measures independently. In [59], the authors summarized country-level public health measures in more than 200 countries from January 1 to October 1, 2020. However, it is difficult to quantify the effort of each public health measures. Hence, we do not consider this factor in this work. Migration is another important feature influencing the spread of the COVID-19. However, few countries or areas provide a daily migration or even weekly migration data [13], [25], [46]. Hence, in our data set, we do not consider migration data either. For developing predictive models, we divided this COVID-19 data set into two parts: 1) the training set (73%), ranging from January 1, 2020, to August 15, 2020 and 2) the test set (27%), from August 16, 2020, to September 30, 2020.

B. Forecasting Problem Formulation

As previously mentioned, we have nine original features, including cumulative confirmed cases, totally recovered cases, death toll, cumulative COVID-19 tests, the latitude and longitude, the continent to which the area belongs, the economic level, and the population of each area. Based on these original features, we can derive the following augmented features.

-

1)Daily Confirmed Cases:

-

2)Daily Recovered Cases:

-

3)Daily Deaths:

-

4)Active COVID-19 Cases:

which represents the number of COVID-19 patients, who have not been removed yet.

-

5)Daily COVID-19 Tests:

-

6)Daily Growth Rate of Daily Confirmed Cases:

-

7)Daily Growth Rate of Daily Recover Cases:

-

8)Daily Growth Rate of Daily Death Cases:

All the input features are summarized in Table II. Note that these input features can be classified into two categories

|

where

represents constant features, which is time-independent, while

represents constant features, which is time-independent, while

stands for time-varying features.

stands for time-varying features.

TABLE II. Input Features for Machine Learning Models.

| Original features | |

|---|---|

|

Cumulative confirmed cases at time

|

|

Total recovered cases at time

|

|

Death toll at time

|

|

Cumulative COVID-19 tests at time

|

|

The latitude of the geographical location of an area |

|

The longitude of the geographical location of an area |

|

The continent to which an area belongs |

|

The level of economic development of an area |

|

The population of an area |

| Augmented features | |

|

Daily confirmed cases |

|

Daily recovered cases |

|

Daily deaths |

|

Active COVID-19 patients |

|

Daily COVID-19 tests |

|

Daily growth rate of confirmed cases |

|

Daily growth rate of daily recover cases |

|

Daily growth rate of daily death cases |

Here, we provide

-day forecasts for

-day forecasts for

consecutive days with quantified uncertainty based on machine learning models. The prediction model is

consecutive days with quantified uncertainty based on machine learning models. The prediction model is

|

where

represents the predicted value, while

represents the predicted value, while

stands for the machine learning model. Then, the prediction problem can be formulated as

stands for the machine learning model. Then, the prediction problem can be formulated as

|

where

is the true value.

is the true value.

IV. Methods

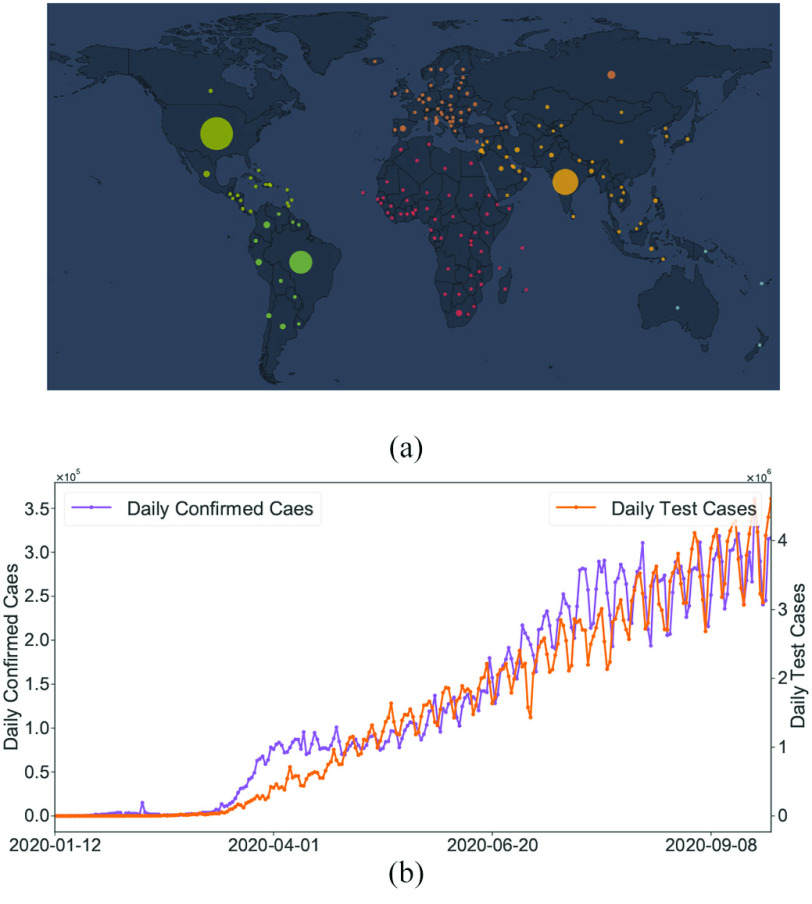

A. Broad Learning System

Drawing on the idea of the random vector function link neural network (RVFLNN), Chen and Liu [42] proposed a BLS, which is a new flat structure neural network without the need for deep architecture. The BLS simplifies the training procedure for a fast universal approximation and has provided competitive results with deep learning and ensemble learning methods in various fields. In recent studies, BLS has shown impressive performance for specific tasks, including visual-based assessment systems [60], predicting the setting time of cement [61], fatigue detection [62], etc. The BLS has a universal approximation capability and can approximate the loss function globally. Inspired by this work, several structural variations of BLS have been proposed [63]. Additionally, the BLS is a kind of increment learning structure, which can efficiently and effectively update the system using newly added features or data. Fig. 2 illustrates the structure of a typical BLS, which shows the effects of different nodes and information propagation. First, the features are extracted from the training data set by the mapped feature nodes. Then, the adopted features are transformed into enhancement nodes. Finally, the output is a linear combination of all mapping features and the output of enhancement nodes. The connection weights of a typical BLS can be derived from the ridge regression approximation algorithm [64], [65].

Fig. 2.

Simplified structure of a typical BLS.

Consider the training set

, where

, where

and

and

are the dimension of each sample and corresponding outputs, respectively. Then, the input pattern is

are the dimension of each sample and corresponding outputs, respectively. Then, the input pattern is

,

,

, where

, where

,

,

, and

, and

is the number of input samples. In the feature learning stage, the input matrix

is the number of input samples. In the feature learning stage, the input matrix

is mapped into

is mapped into

feature nodes by

feature nodes by

feature mapping

feature mapping

to generates random features. The following feature function generates the mapped feature

to generates random features. The following feature function generates the mapped feature

:

:

|

where weights

and bias term

and bias term

are randomly generated matrices with applicable dimensions from the given proper distribution scope

are randomly generated matrices with applicable dimensions from the given proper distribution scope

.

.

stands for prior activation functions of mapped feature nodes. The outputs of groups of feature nodes can be denoted as

stands for prior activation functions of mapped feature nodes. The outputs of groups of feature nodes can be denoted as

|

where

and

and

expresse all the mapped features from

expresse all the mapped features from

feature modes.

feature modes.

Then,

is randomly mapped to enhancement nodes for nonlinear transformation. Assuming that there are

is randomly mapped to enhancement nodes for nonlinear transformation. Assuming that there are

groups of enhancement nodes, the output of the

groups of enhancement nodes, the output of the

th group of enhancement node is

th group of enhancement node is

|

where weights

and bias term

and bias term

are also generated randomly, and

are also generated randomly, and

represents the activation function of the

represents the activation function of the

th enhancement node. The overall output of the enhancement layer can be expressed as

th enhancement node. The overall output of the enhancement layer can be expressed as

|

where

. Consequently, the output of BLS can be derived as

. Consequently, the output of BLS can be derived as

|

where

is the weights connecting the layer of feature and enhancement nodes to the output layer.

is the weights connecting the layer of feature and enhancement nodes to the output layer.

Let

, then, the connection weights of a BLS can be rapidly approximated by the ridge regression [66]

, then, the connection weights of a BLS can be rapidly approximated by the ridge regression [66]

|

where

is a constant. The BLS has a simple structure, which effectively increases the training procedure and keeps the generalization ability of function approximation.

is a constant. The BLS has a simple structure, which effectively increases the training procedure and keeps the generalization ability of function approximation.

B. Random Forest Feature Selection

RFs is a popular ensemble learning methods consisting of multiple DTs [67]. Correlation between different DTs can be eliminated via a random adopted strategy. Each DT is developed from a random sample of the original training set. Each tree provides a classification or regression result, and the forest summarizes these results to formulate a more accurate and stable output. Hence, RF shows good performance in solving high-dimensional, nonlinear, and ill-posed classification and regression problems. A highly dimensional problem always has a vast number of input features. In establishing of prediction models, a feature

with a high correlation with the objective value

with a high correlation with the objective value

may not be an important feature helping the prediction, while some features with relatively low correlation coefficients could be more important. It is challenging to manually investigate the feature importance and select the most relevant features for prediction. Compared with other feature selection methods, RF is more explanatory and efficient. One key advantage of using RFs is that it can derive the importance score of each feature, which can be utilized to evaluate individual feature importance regarding the prediction results [68]. Hence, RF is adopted to select the important features.

may not be an important feature helping the prediction, while some features with relatively low correlation coefficients could be more important. It is challenging to manually investigate the feature importance and select the most relevant features for prediction. Compared with other feature selection methods, RF is more explanatory and efficient. One key advantage of using RFs is that it can derive the importance score of each feature, which can be utilized to evaluate individual feature importance regarding the prediction results [68]. Hence, RF is adopted to select the important features.

First, we can utilize ordinary RF to derive the importance score of each feature. RF uses the mean-square error (MSE) or mean absolute error (MAE) to develop regression trees and determine regression results in each tree. The MSE at node

,

,

, measuring the impurity of

, measuring the impurity of

can be derived as

can be derived as

|

where

is the regression results of sample

is the regression results of sample

recording at node

recording at node

.

.

is the number of samples divided for node

is the number of samples divided for node

.

.

Again, the MSE of feature

for splitting the tree node

for splitting the tree node

is defined as

is defined as

|

where

represents the impurity of node

represents the impurity of node

;

;

and

and

represent the left and right child node of node

represent the left and right child node of node

, respectively;

, respectively;

and

and

stands for a fraction of examples assigned to the left and right child node, respectively. Generally, we adopt the feature maximizing the reduction in impurity as the splitting feature.

stands for a fraction of examples assigned to the left and right child node, respectively. Generally, we adopt the feature maximizing the reduction in impurity as the splitting feature.

Moreover, we can derive the importance score of the tree-

for feature

for feature

from the

from the

|

where

is the set of split nodes of the tree-

is the set of split nodes of the tree-

;

;

is a node set splitting on feature

is a node set splitting on feature

;

;

is the sum of the impurity of all nodes in tree-

is the sum of the impurity of all nodes in tree-

.

.

Normalization of the importance score is defined as

|

where

stands for the importance score of

stands for the importance score of

and

and

stands for the sum of all features impurity in the tree-

stands for the sum of all features impurity in the tree-

, while the normalized importance score is

, while the normalized importance score is

.

.

Finally, in RF, the importance score of

is defined as

is defined as

|

where

represents the number of tree.

represents the number of tree.

C. Bagging

Bagging [69] is a kind of ensemble learning strategy that ensemble many weak learners to build a strong learning idea. It is mainly used for model improvement in machine learning and has wide applications in classification and regression tasks in prediction. Boostrap Sampling is a technique in Bagging. Algorithm 2 describes the process of Boostrap Sampling. Suppose one has a data set that contains

samples; then, each sample is randomly selected and put back into the original sample set. Repeat this procedure for

samples; then, each sample is randomly selected and put back into the original sample set. Repeat this procedure for

times. A subdata set containing

times. A subdata set containing

samples can be obtained. The probability of each sample in the original data set being selected is the same. In this work, we utilized the Boostrap Sampling strategy to establish

samples can be obtained. The probability of each sample in the original data set being selected is the same. In this work, we utilized the Boostrap Sampling strategy to establish

subdata sets containing

subdata sets containing

samples. Then, we utilize

samples. Then, we utilize

subdata sets to establish

subdata sets to establish

weak learners. Finally, a combination strategy is used to combine

weak learners. Finally, a combination strategy is used to combine

weak learners into strong learners.

weak learners into strong learners.

Algorithm 1 Derive RF Feature Importance Score

Input: Training dataset:

; Number of features in

; Number of features in

:

:

; Number of selected features:

; Number of selected features:

); Feature set of

); Feature set of

:

:

;

;Output: Selected feature set

;

;Use

to build a RF model;

to build a RF model;-

2:

Set the number of RF trees:

;

; for

to

to

do

do-

4:

Set

;

; for

to

to

do

do-

6:

Set

;

; Set the set of split nodes:

;

;-

8:

Set the set of split nodes on feature

:

:

;

; for

in

in

do

do-

10:

;

; end for

-

12:

;

;  ;

;-

14:

end for

for

to

to

do

do-

16:

;

; end for

-

18:

end for

for

to

to

do

do-

20:

Set

;

; for

to

to

do

do-

22:

;

; end for

-

24:

;

; end for

-

26:

;

; Sort

from largest to smallest, get the sorted set

from largest to smallest, get the sorted set

;

;-

28:

Base

to extract the feature set

to extract the feature set

of the first

of the first

scores.

scores. return

.

.

Algorithm 2 Boostrap Sampling

Input: Sample ratio:

; Number of iterations:

; Number of iterations:

; Training dataset:

; Training dataset:

;

;Output: The sampled sample set

Set the number of subsamples:

;

;for

to

to

do

do-

3:

for

to

to

do

do Use random sampling to sample

from

from

;

; goes back to the data sample set

goes back to the data sample set

;

;-

6:

Put

into the data set

into the data set

;

; end for

-

9:

Put

into the

into the

;

; end for

return

.

.

Assume that the sample data set of COVID-19 information is

, where

, where

represents a sample of the data set composed of features and predictive value. All the samples can be divided into a training and a test data set, the sizes of which are

represents a sample of the data set composed of features and predictive value. All the samples can be divided into a training and a test data set, the sizes of which are

and

and

, respectively. A sampling ratio of

, respectively. A sampling ratio of

is set to determine the number of samples extracted from the original training data set to form a subtraining data set. The bootstrapping technique is adopted to make the selection procedure of the subtraining data set completely random. Bootstrapping technique draws samples after choosing these samples and then puts samples back into the original training data set. The process is shown in Algorithm 2.

is set to determine the number of samples extracted from the original training data set to form a subtraining data set. The bootstrapping technique is adopted to make the selection procedure of the subtraining data set completely random. Bootstrapping technique draws samples after choosing these samples and then puts samples back into the original training data set. The process is shown in Algorithm 2.

D. Random-Forest-Bagging Broad Learning System

Here, the classic RF and ensemble learning-bagging are adopted to enhance the performance of BLS for the prediction of the spread of COVID-19. Here, we leverage the RF feature selection strategy for adopting important features to improve predictive performance. Then, we randomly sample data in these important features to form a number of subtraining data sets based on bagging strategy and then build multiple independent BLS prediction models based on these subtraining data. Finally, we combine these results to provide a final prediction. The structure of the RF-Bagging-BLS model is shown in Fig. 3, in which

is the training input,

is the training input,

is the expected training output. After the training data pass the feature importance analysis,

is the expected training output. After the training data pass the feature importance analysis,

is the input after the feature selection in data set

is the input after the feature selection in data set

,

,

is excepted output in data set

is excepted output in data set

.

.

Fig. 3.

Structure of bagging-BLS and RF-bagging-BLS.

The establishment of an RF-bagging-BLS includes the following parts.

-

1)

Feature Selection: Multiple factors are related to the spread of epidemics. However, part of the features may be less relevant to the spread and redundant, decreasing learning ability. As the multiple features are mutually independent, we adopt an RF feature selection strategy to automatically adopt the most suitable features (shown in Algorithm 1).

-

2)

Establish Subtraining Data Set: The whole data set is divided into two data sets: a) a training data set (of size

) and b) a test data set (of size

) and b) a test data set (of size

).

).

samples are chosen from the training data set using the Boostrapping technique, where

samples are chosen from the training data set using the Boostrapping technique, where

is the sampling ratio and

is the sampling ratio and

represents the largest integer no more than

represents the largest integer no more than

. This sampling process is repeated

. This sampling process is repeated

times to prepare

times to prepare

different subtraining data sets for training submodels.

different subtraining data sets for training submodels. -

3)Build the Sub-BLS Models: In this model, each sub-BLS model is regarded as a weak learner in the ensemble learning model. Then, we combine multiple weak learners to form strong learners. Finally, the output of the RF-Bagging-BLS model (shown in Algorithm 3) can be computed by

where

is the predicted value of the

is the predicted value of the

th learner, while

th learner, while

is final predicted value.

is final predicted value.

Algorithm 3 RF-Bagging-BLS

Input: Training dataset:

; Number of features in

; Number of features in

:

:

; Number of selected features:

; Number of selected features:

; Feature set of

; Feature set of

:

:

; Number of features in

; Number of features in

:

:

; Number of iterations:

; Number of iterations:

; Sample ratio:

; Sample ratio:

; Basic learning model:

; Basic learning model:

;

;Output: A prediction model

;

;-

1:

Enter

,

,

,

,

and

and

into Algorithm 1 to get the feature set

into Algorithm 1 to get the feature set

.

. -

2:

Selected data set:

;

; -

3:

Enter

,

,

and

and

into Algorithm 2 to get the sampled set

into Algorithm 2 to get the sampled set

;

; -

4:

for

to

to

do

do -

5:

Randomly generate feature set

from

from

;

; -

6:Sub-training set:

-

7:Using

Training the sub-BLS:

Training the sub-BLS:

-

8:

end for

-

9:

return

.

.

V. Experimental Results

In order to assess the performance of the proposed technique, we adopt several forecasting methods to evaluate the results. We employed LR model, KNN, DT, Ada, RF, GBDT, ETs regressor, SVR, CatBoost (CAT), LightGBM (LGB), XGBoost (XGB), and BLS approaches in the comparisons. We trained each model with data until September 30, 2020, reported by local health authorities in 184 countries and 1241 areas. Meanwhile, multiple evaluation metrics are adopted to evaluate the predictive power of each model.

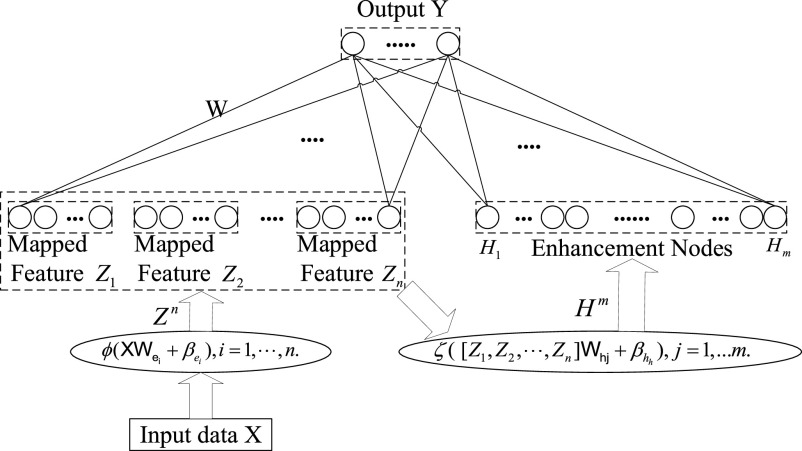

Due to the large amount of human and financial resources required to achieve a comprehensive picture of the spread of COVID-19 in an area, the data released by many local authorities will occasionally have some errors. For instance, the number of daily confirmed cases or the daily increase in the number of recovered people is negative. Hence, we have to process the data set by removing the abnormal data or filling in missing data. In this study, the predictive value

is the cumulative number of confirmed cases in an area, which increases monotonically. Here, we adopt

is the cumulative number of confirmed cases in an area, which increases monotonically. Here, we adopt

and

and

; namely, we provide 7-days forecasts for 7-consecutive days in an area (cities, provinces, states, and other prefectures). According (10), we have more than 100 different candidate features. Studies indicate that, in some scenarios, data-driven methods perform well when the output data have a distribution close to a uniform or normal distribution [70]. We hope that the predicted value distribution is closer to the normal distribution to improve the model’s generalization ability after training. However, the distribution of

; namely, we provide 7-days forecasts for 7-consecutive days in an area (cities, provinces, states, and other prefectures). According (10), we have more than 100 different candidate features. Studies indicate that, in some scenarios, data-driven methods perform well when the output data have a distribution close to a uniform or normal distribution [70]. We hope that the predicted value distribution is closer to the normal distribution to improve the model’s generalization ability after training. However, the distribution of

is far from a normal distribution [shown in Fig. 4(a) with

is far from a normal distribution [shown in Fig. 4(a) with

], while the distribution of

], while the distribution of

is similar to a normal distribution [shown in Fig. 4(b)]. Here, we consider two scenarios: under scenario-I, first, machine learning models are developed to predict

is similar to a normal distribution [shown in Fig. 4(b)]. Here, we consider two scenarios: under scenario-I, first, machine learning models are developed to predict

to achieve prediction value

to achieve prediction value

, and then perform the reverse operation to achieve the predictive value of

, and then perform the reverse operation to achieve the predictive value of

; under scenario-II, we establish machine learning models predict

; under scenario-II, we establish machine learning models predict

directly.

directly.

Fig. 4.

(a) Probability distribution of

. (b) Probability distribution of

. (b) Probability distribution of

.

.

A. Correlation Analysis

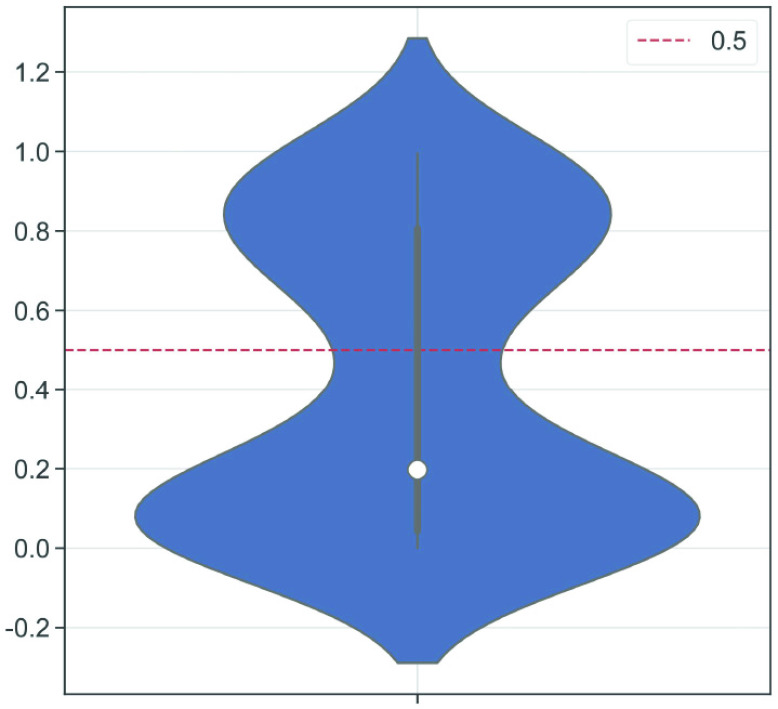

In our case, there exists a large number of features that may influence the spread of COVID-19. In the proposed methods, we use RF for feature selection, while we adopted correlation analysis for feature selection for other classical models for a fair comparison. In order to adopt features highly correlated with the predictive value as the input of machine learning models, the violin chart is utilized. First, we derived all the correlation coefficients between input feature

and the predictive value

and the predictive value

. Then, the violin chart (Fig. 5) shows the frequency (or probability distribution) of the absolute value of correlation coefficients. The correlation coefficients range from 0.0004 to 0.9953, while upper and lower quartiles are 0.0436 and 0.8052, respectively. The median of the correlation coefficient is about 0.2. Note that the violin chart is clearly separated into two parts (the dashed line in Fig. 5): one class of the features with the absolute value of the correlation coefficient is greater than 0.5, while the other is less than 0.5. Then, according to this observation,

. Then, the violin chart (Fig. 5) shows the frequency (or probability distribution) of the absolute value of correlation coefficients. The correlation coefficients range from 0.0004 to 0.9953, while upper and lower quartiles are 0.0436 and 0.8052, respectively. The median of the correlation coefficient is about 0.2. Note that the violin chart is clearly separated into two parts (the dashed line in Fig. 5): one class of the features with the absolute value of the correlation coefficient is greater than 0.5, while the other is less than 0.5. Then, according to this observation,

was taken as the threshold. The feature with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.5 after taking the absolute value is taken as the input of machine learning models. Finally, 50 features are selected as the input of classical models except for the proposed RF-BLS and RF-Bagging-BLS. The 50 features are divided into two categories, including original and augmented features (shown in Table III).

was taken as the threshold. The feature with a correlation coefficient greater than 0.5 after taking the absolute value is taken as the input of machine learning models. Finally, 50 features are selected as the input of classical models except for the proposed RF-BLS and RF-Bagging-BLS. The 50 features are divided into two categories, including original and augmented features (shown in Table III).

Fig. 5.

Absolute value of the correlation coefficient between features and the predictive value: the white point is the median value of data; the upper and lower bounds of the middle black box represent the upper and lower quartiles of the correlation coefficients, respectively; the upper and lower bounds of the middle black line represent the maximum and minimum values of the correlation coefficients; the shape of the violin indicates the frequency (or estimated probability distribution) of correlation coefficients.

TABLE III. 50 Important Features for Classical Models.

| Selected features | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Original features |

|

Cumulative confirmed cases at day

( (

) ) |

|

Total recovered cases at day

( (

) ) |

|

|

Death toll at day

( (

) ) |

|

|

Cumulative COVID-19 tests at day

( (

) ) |

|

|

The population of an area | |

| Augmented features |

|

Activate COVID-19 patients at day

( (

) ) |

|

Daily confirmed cases at day

( (

) ) |

|

|

Daily COVID-19 tests at day

( (

) ) |

B. Experimental Results by Classical Methods

After selecting the relevant features, we used all the models mentioned above to build the predictive models. Since the scale of different features varies in a large range, we first adopted the Z-score standardized method to normalize the feature data on the same scale

|

where

and

and

represent the mean of feature and the standard deviation of feature, respectively.

represent the mean of feature and the standard deviation of feature, respectively.

Each machine learning model has a large volume of hyperparameters to be adjusted to achieve a satisfying performance. Here, a grid search method is adopted for searching the optimal hyperparameters [71]. The regression task evaluation metrics, including MAE, relative MSE (RMSE), coefficient of determination (

), adjusted coefficient of determination (

), adjusted coefficient of determination (

), median absolute error (MAD), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), were adopted to evaluate the performance of each model. Suppose that the test set has

), median absolute error (MAD), and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), were adopted to evaluate the performance of each model. Suppose that the test set has

samples, the characteristics of the model input are

samples, the characteristics of the model input are

,

,

is the predicted value of sample

is the predicted value of sample

,

,

is the actual value of the sample,

is the actual value of the sample,

represents the median value of

represents the median value of

samples

samples

|

where

is residual sum of squares and

is residual sum of squares and

represents total sum of squares.

represents total sum of squares.

Tables IV and V show the regression task evaluation metrics for each model under two scenarios. Without considering the proposed RF-BLS and RF-Bagging-BLS methods, LR takes a good effect in predicting

, with 3394.6494 for RMSE, 1601.8012 for MAE, and 0.9994 for

, with 3394.6494 for RMSE, 1601.8012 for MAE, and 0.9994 for

. DT makes a better effect to predict

. DT makes a better effect to predict

. The RMSE and MAE of DT in case two are 20441.1788 and 9758.9613, respectively. However, DT shows better robustness in predicting

. The RMSE and MAE of DT in case two are 20441.1788 and 9758.9613, respectively. However, DT shows better robustness in predicting

, with 1423 for MAD. For ensemble learning models, Ada has the best predictive effect compared to other models. In case one for predicting

, with 1423 for MAD. For ensemble learning models, Ada has the best predictive effect compared to other models. In case one for predicting

, RMSE and MAE are 17861.0283 and 5933.6822, respectively. LGB has the best robustness among the classical ensemble learning models with MAD equals 939.8207. Among all the classical methods, the predictive performance of BLS is better than all the other methods. In scenario-II, The RMSE, MAE, and

, RMSE and MAE are 17861.0283 and 5933.6822, respectively. LGB has the best robustness among the classical ensemble learning models with MAD equals 939.8207. Among all the classical methods, the predictive performance of BLS is better than all the other methods. In scenario-II, The RMSE, MAE, and

of BLS are 2269.8906, 1362.8407, and 0.9997, respectively. It means BLS has a better fitting effect on the test set. By comparing Tables IV and V, we find that DT and LGB have better results in predicting

of BLS are 2269.8906, 1362.8407, and 0.9997, respectively. It means BLS has a better fitting effect on the test set. By comparing Tables IV and V, we find that DT and LGB have better results in predicting

, which means that the data has a normal distribution and a certain lifting effect for some models.

, which means that the data has a normal distribution and a certain lifting effect for some models.

TABLE IV. Scenario-I: The Evaluation Value of Different Models With the Predictive Value

.

.

| Method | RMSE | MAE |

|

MAD |

|

MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 57387.6106e+9 | 76255.7453e+8 | -1.5816e+17 | 21649.1423 | -1.6344e+17 | 2.5650+9 |

| KNN | 32589.3837 | 13272.0041 | 0.9498 | 3875.6634 | 0.9472 | 13.7311 |

| DT | 20441.1788 | 9758.9613 | 0.9799 | 3664.0001 | 0.9792 | 31.8415 |

| SVR | 119751.7181 | 43284.9216 | 0.3113 | 6676.6545 | 0.2883 | 28.2169 |

| Ada | 27126.1988 | 9364.6234 | 0.9646 | 1033.5000 | 0.9634 | 5.9561 |

| RF | 23413.5558 | 8136.2741 | 0.9736 | 1090.4159 | 0.9727 | 5.2950 |

| GBDT | 25739.2592 | 9643.7920 | 0.9681 | 1791.4312 | 0.9671 | 8.3891 |

| ET | 21978.5323 | 7612.5017 | 0.9768 | 1292.7426 | 0.9760 | 6.1060 |

| CAT | 31788.7347 | 11952.3085 | 0.9515 | 1533.8260 | 0.9498 | 8.4482 |

| LGB | 24249.7400 | 8033.8196 | 0.9717 | 939.8207 | 0.9708 | 5.4479 |

| XGB | 29203.4126 | 9389.2712 | 0.9590 | 1107.6260 | 0.9576 | 5.5478 |

| BLS | 35079.3674 | 16463.1951 | 0.9409 | 9145.3791 | 0.9389 | 27.6222 |

| RF-BLS | 39131.9767 | 23896.6042 | 0.9265 | 9328.3896 | 0.9255 | 40.3023 |

| Bagging-BLS | 13539.3023 | 9882.3092 | 0.9911 | 7690.6102 | 0.9909 | 23.0960 |

| RF-Bagging-BLS | 35793.3709 | 19923.3754 | 0.9384 | 8895.5277 | 0.9376 | 39.5285 |

TABLE V. Scenario-II: The Evaluation Value of Different Model With Predictive Value

.

.

| Method | RMSE | MAE |

|

MAD |

|

MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 3394.6494 | 1601.8012 | 0.9994 | 642.4868 | 0.9994 | 3.2467 |

| KNN | 32267.9550 | 16772.8781 | 0.9483 | 6280.7837 | 0.9483 | 22.3130 |

| DT | 24733.7204 | 10304.4542 | 0.9706 | 1423.0000 | 0.9696 | 10.8748 |

| SVR | 53319.4198 | 23591.0204 | 0.8634 | 8708.3930 | 0.8589 | 63.6835 |

| Ada | 17861.0283 | 5933.6822 | 0.9846 | 1196.0000 | 0.9842 | 5.5883 |

| RF | 23770.2149 | 8554.5544 | 0.9728 | 1218.9372 | 0.9719 | 6.7004 |

| GBDT | 21103.7782 | 7325.3585 | 0.9786 | 977.8010 | 0.9778 | 7.2672 |

| ET | 19635.1575 | 6997.1890 | 0.9814 | 1469.4092 | 0.9808 | 6.7076 |

| CAT | 25744.2812 | 8687.9153 | 0.9681 | 1351.8562 | 0.9671 | 7.3150 |

| LGB | 25470.3411 | 9120.9554 | 0.9688 | 973.4710 | 0.9678 | 7.9324 |

| XGB | 24354.7123 | 8455.0691 | 0.9715 | 1082.3067 | 0.9705 | 6.8996 |

| BLS | 2269.8906 | 1362.8407 | 0.9997 | 766.4345 | 0.9997 | 6.7834 |

| RF-BLS | 2042.4723 | 1018.2183 | 0.9997 | 565.5706 | 0.9997 | 6.4979 |

| Bagging-BLS | 2872.1029 | 1475.1688 | 0.9996 | 697.3510 | 0.9995 | 3.9903 |

| RF-Bagging-BLS | 1989.1970 | 952.5739 | 0.9998 | 432.3244 | 0.9998 | 3.0090 |

C. Experimental Results by RF-Bagging-BLS

1). RF-BLS:

The RF-BLS is established by BLS using the features adopted through RF. Compared with classical BLS, the predicted RF-BLS results are slightly improved, indicating that the feature selection strategy base on RF helps improve BLS performance. Table V shows the predicted results of RF-BLS and BLS. The RMSE, MSE, and MAE of RF-BLS predicting

are 4171692.9897, 2042.4723, and 1018.2183, respectively. It can be observed that the RMSE, MSE and MAE of the RF-BLS are lower than that of BLS. Meanwhile, compared with BLS, RF-BLS is also more robust and the MAD is 565.5706.

are 4171692.9897, 2042.4723, and 1018.2183, respectively. It can be observed that the RMSE, MSE and MAE of the RF-BLS are lower than that of BLS. Meanwhile, compared with BLS, RF-BLS is also more robust and the MAD is 565.5706.

2). Bagging-BLS:

The Bagging-BLS is a combination model of Bagging and BLS [72]. Fig. 3 shows the structure of Bagging-BLS. It is worth noting that the feature selection used by Bagging-BLS is still a correlation analysis. Through RMSE and MAE in Table V, Bagging-BLS also has better robustness than classical BLS. The MAD of Bagging-BLS predicts

is 565.5706. However, by comparing RMSE and MAE, the Bagging-BLS model only increase the predictive accuracy slightly.

is 565.5706. However, by comparing RMSE and MAE, the Bagging-BLS model only increase the predictive accuracy slightly.

3). RF-Bagging-BLS:

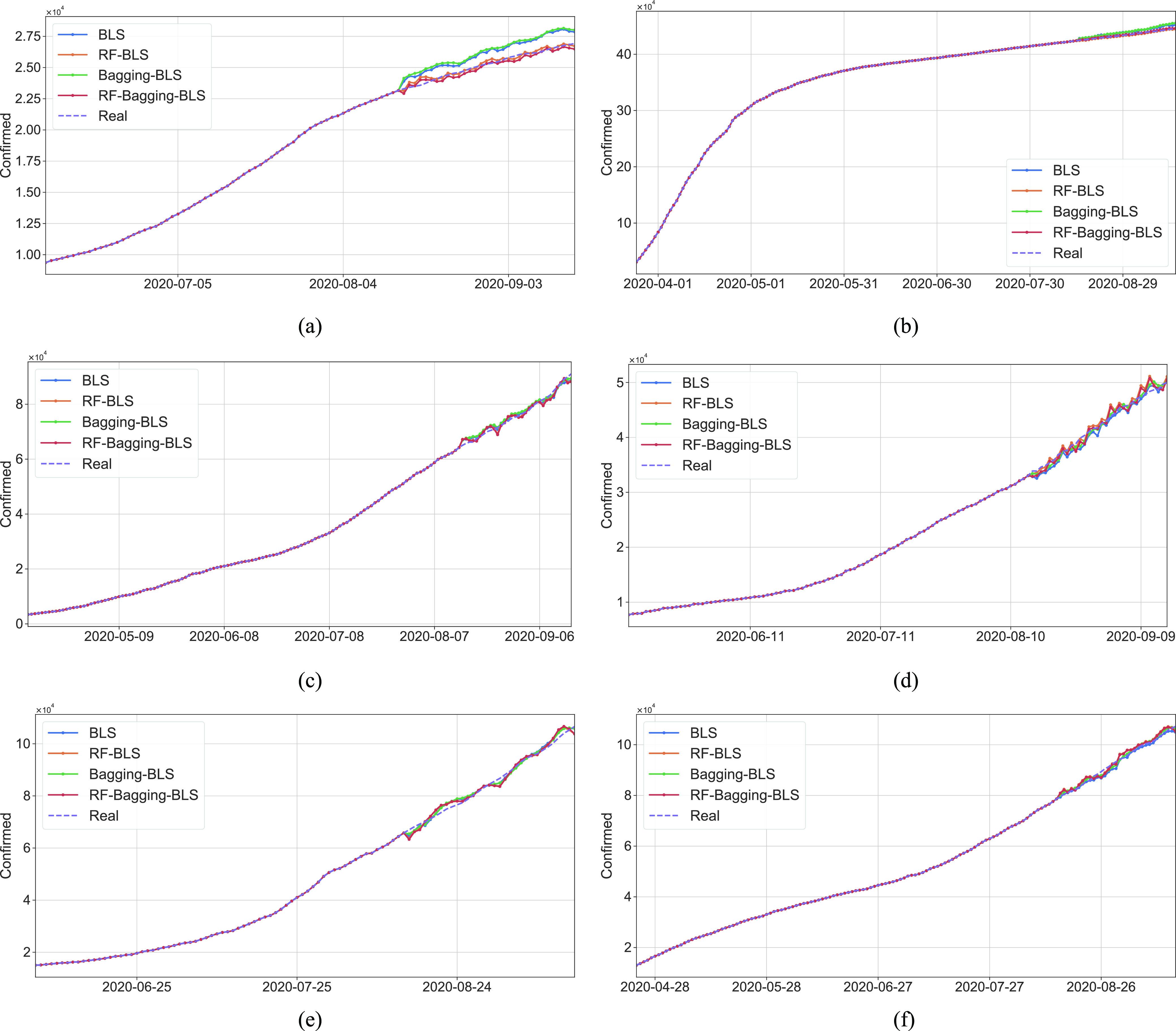

Experimental results show that the proposed RF-Bagging-BLS achieve the best value among all the comparison algorithms. All the evaluation metric of BLS are all the best (shown in Table V). In case one, the RMSE, MAE

of RF-Bagging-BLS predicts

of RF-Bagging-BLS predicts

are 1989.1970, 952.5739 and 0.9998, respectively. Additionally, the metric MAD shows that RF-Bagging-BLS has great robustness. Fig. 6 shows the prediction results of New Mexico, New York, Wisconsin, Kansas, Missouri, and Indiana by BLS, RF-BLS, Bagging-BLS, and RF-Bagging-BLS, respectively. Several researchers utilize CNN, LSTM, and GRU models to forecast the spread of COVID-19 based on a data set of one or a few countries. In this work, we also test CNN, LSTM, and GRU based on our data set. However, these methods are easily overfitting. For instance, LSTM (with three layers, 64 nodes), GRU (four layers, 128 nodes) would converge in 1000 epochs, and 1-D CNN (one layer, three kernel size, one stride) would converge in 100 epochs. GRU achieves 25021.441 RMSE in training data, while 147259.83 RMSE in testing data; LSTM achieves 18975.209 RMSE in training data, while 169766.4 RMSE in testing data; 1-D CNN achieves 11937.837 RMSE in training data, but performed poorly in the testing data. Experimental results indicate that these neural network models are easily overfitting based on a small data set and provide poor performance in this task.

are 1989.1970, 952.5739 and 0.9998, respectively. Additionally, the metric MAD shows that RF-Bagging-BLS has great robustness. Fig. 6 shows the prediction results of New Mexico, New York, Wisconsin, Kansas, Missouri, and Indiana by BLS, RF-BLS, Bagging-BLS, and RF-Bagging-BLS, respectively. Several researchers utilize CNN, LSTM, and GRU models to forecast the spread of COVID-19 based on a data set of one or a few countries. In this work, we also test CNN, LSTM, and GRU based on our data set. However, these methods are easily overfitting. For instance, LSTM (with three layers, 64 nodes), GRU (four layers, 128 nodes) would converge in 1000 epochs, and 1-D CNN (one layer, three kernel size, one stride) would converge in 100 epochs. GRU achieves 25021.441 RMSE in training data, while 147259.83 RMSE in testing data; LSTM achieves 18975.209 RMSE in training data, while 169766.4 RMSE in testing data; 1-D CNN achieves 11937.837 RMSE in training data, but performed poorly in the testing data. Experimental results indicate that these neural network models are easily overfitting based on a small data set and provide poor performance in this task.

Fig. 6.

Forecast results generated by BLS, RF-BLS, Bagging-BLS, and RF-Bagging-BLS; (a) New Mexico. (b) New York. (c) Wiscosin. (d) Kansas. (e) Missouri. (f) Indiana.

Previous work points outs that in some cases that data-driven methods perform well when the output data have a distribution close to a uniform or normal distribution. Hence, in this work, we tested two scenarios: under scenario-I, first, we develop machine learning models to predict

to achieve the predictive value

to achieve the predictive value

, then derive

, then derive

, while under scenario-II, machine learning models predict the cumulative confirmed cases

, while under scenario-II, machine learning models predict the cumulative confirmed cases

directly. However, experimental results indicate that, under scenario one, all the models achieve a worse performance in forecasting

directly. However, experimental results indicate that, under scenario one, all the models achieve a worse performance in forecasting

. Hence, the predictive output

. Hence, the predictive output

with a normal distribution cannot help improve the performance. Additionally, according to the experimental results presented in Tables IV and V, most machine learning models can achieve relatively better performance under scenario-II. The proposed RF-Bagging BLS show the best performance in predicting

with a normal distribution cannot help improve the performance. Additionally, according to the experimental results presented in Tables IV and V, most machine learning models can achieve relatively better performance under scenario-II. The proposed RF-Bagging BLS show the best performance in predicting

, which is also the best result under two scenarios. Experiment results indicate that the distribution of predictive value affects the performance of data-driven models [73]. However, in our case, the predictive value with a uniform or normal distribution may not help in improving the predictive performance. BLS algorithm is efficient for training. In our work, the mean training time of RF-BLS, Bagging-BLS, and RF-Bagging-BLS, is 15.346, 0.500, and 17.175 s, respectively. After training, the time required to predict a result is 0.273, 0.287, and 0.467 s for RF-BLS, Bagging-BLS, and RF-Bagging-BLS, respectively.

, which is also the best result under two scenarios. Experiment results indicate that the distribution of predictive value affects the performance of data-driven models [73]. However, in our case, the predictive value with a uniform or normal distribution may not help in improving the predictive performance. BLS algorithm is efficient for training. In our work, the mean training time of RF-BLS, Bagging-BLS, and RF-Bagging-BLS, is 15.346, 0.500, and 17.175 s, respectively. After training, the time required to predict a result is 0.273, 0.287, and 0.467 s for RF-BLS, Bagging-BLS, and RF-Bagging-BLS, respectively.

VI. Conclusion

COVID-19 has become a global public health threat and spread to more than 200 countries by September 30, 2020. How to contain the spread of COVID-19 becomes a challenging task for policymakers to assess health care requirements to estimate the present trends, determine public health measures, and flatten the COVID-19 curve shortly. Until now, most researchers just developed classical models based on epidemic spreading data covering one or several countries. However, the behavior of the COVID-19 outbreak varies from region-to-region. The number of confirmed cases released by the local authorities could be influenced by multiple factors, such as testing capacity and other related factors. Additionally, classical epidemiological models usually do not consider extra details, such as testing capacity, population, geographic information, etc. With limited testing capacity and human resources, significant delays in identifying, isolating, and reporting cases due to the magnitude of the epidemic are unavoidable, which has a negative impact on the predictive performance. Hence, whether these models can be applied to other countries or not is a question.

Due to the complex nature of forecasting the COVID-19 trend, we suggest machine learning as an effective technique to model the outbreak. Recently, most of the local authorities provide COVID-19 information, which scatters on dozens of public databases. In this work, we collect and unified these data sets into one comprehensive data set, including the epidemic spread data, geographic information, economic information, population, COVID-19 testing information of 184 countries and 1241 areas (cities, provinces, states, and other areas). Then, a hybrid machine learning model of RF-Bagging-BLS is developed for predicting the COVID-19 trend in more than 180 countries and 1200 areas. The proposed models showed promising performance in timely short-term forecasts without the requirement of epidemiological models. RF-Bagging-BLS model outperformed other models by delivering accurate results on validation samples. Experimental results show that the proposed method presents the best result in all evaluation criteria, indicating the RF-Bagging-BLS model is suitable with this training data set. An accurate prediction of the pandemic situation can help the authority to evaluate the hospital capacity needs and provide effective help for the government to adopt epidemic prevention policies [74], [75]. However, inaccurate predictions of cases may lead to a loosening of containment policies, leading to the emergence of another wave of infection and a rapid increase in the number of infected cases [76]. The effective implementation of public health interventions, such as social distancing, lockdown, and personal protection, will be critical to bringing the epidemic under control. Short-term forecasting of COVID-19 can help policymakers, including health managers, public health officials, etc., to prepare medical resources, organize health care to confront the epidemic, plan nonpharmaceutical interventions required to mitigate an outbreak, finally contain the epidemic outbreak or even eliminate the pandemic. This work can help local authorities to make suitable decisions in the future.

The world today is connected with smart devices [77]–[79]. Data is recorded and shared between the regions in an unprecedented way than ever before [80]. The availability of timely and high-quality pandemic data can help scholars develop data-driven methods to analyze the pandemic situation. Weather and air quality are other important factors. However, the proposed data set did not include the detailed weather and air quality data, such as daily temperature, wind speed, etc. We replace the weather data with geographic location data, which may be too rough in this work. Experimental results show that the proposed method present the best result in all the evaluated criterion, indicating the proposed method is suitable with this training data set. In the future work, we would quantify the effort of public health measures, and consider migration data and weather data. Machine learning has been shown as a powerful tool in healthcare. We would explore the true capability of the proposed hybrid model.

Biographies

Choujun Zhan (Member, IEEE) received the B.S. degree in automatic control engineering from Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China, in 2007, and the Ph.D. degree in electronic engineering from the City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, in 2012.

After graduation, he worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow with the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong. Since Fall 2016, he has been an Associate Professor with the Department of Electronic Communication and Software Engineering, Nanfang College of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou. He is currently a Professor with the School of Computer, South China Normal University, Guangzhou. His research interests include complex networks, time-series modeling and prediction, epidemic spreading, information diffusion, and machine learning.

Yufan Zheng is currently pursuing the B.S. degree with the Nanfang College of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangdong, China.

His recent research interests include data mining of time series, machine learning, deep learning, and epidemic spreading based on complex networks and artificial intelligence.

Haijun Zhang (Senior Member, IEEE) received the B.Eng. and master’s degrees from Northeastern University, Shenyang, China, in 2004 and 2007, respectively, and the Ph.D. degree from the Department of Electronic Engineering, City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, in 2010.

He was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Windsor, Windsor, ON, Canada, from 2010 to 2011. Since 2012, he has been with the Shenzhen Graduate School, Harbin Institute of Technology, Shenzhen, China, where he is currently a Professor of Computer Science. His current research interests include neural networks, data mining, machine learning, computational advertising, and service computing.

Prof. Zhang is currently an Associate Editor of Neurocomputing, Neural Computing and Applications, and Pattern Analysis and Applications.

Quansi Wen (Member, IEEE) received the bachelor’s and master’s degrees from RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, in 2011 and 2013, respectively, and the Ph.D. degree from the School of Computer Science and Engineering, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, in 2020.

Since 2021, she has been with the School of Computer Science and Engineering, South China University, China, and also with the Jiangmen City Road Traffic Accident Social Relief Fund Management Center, Jiangmen, China. Her current research interests includes information diffusion, access control, and network security.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China, under Grant 201904010224; in part by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China, under Grant 2020A1515010761 and Grant 2018A030313351; and in part by the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province under Grant 2020B010166001 and Grant 2019B010137001.

Contributor Information

Choujun Zhan, Email: zchoujun2@gmail.com.

Yufan Zheng, Email: zhjpre@gmail.com.

Haijun Zhang, Email: hjzhang@hitsz.edu.cn.

Quansi Wen, Email: qwen2012@foxmail.com.

References

- [1].Wölfel R.et al. , “Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019,” Nature, vol. 581, no. 7809, pp. 465–469, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].He X.et al. , “Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19,” Nat. Med., vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 672–675, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ou S.et al. , “Machine learning model to project the impact of COVID-19 on U.S. motor gasoline demand,” Nat. Energy, vol. 5, pp. 666–673, Jul. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Badr H. S., Du H., Marshall M., Dong E., Squire M. M., and Gardner L. M., “Association between mobility patterns and COVID-19 transmission in the USA: A mathematical modelling study,” Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 1247–1257, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wang Y., Yuan Y., Wang Q., Liu C., Zhi Q., and Cao J., “Changes in air quality related to the control of coronavirus in China: Implications for traffic and industrial emissions,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 731, Aug. 2020, Art. no. 139133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Forster P. M.et al. , “Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19,” Nat. Climate Change, vol. 10, pp. 913–919, Oct. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lau S. K.et al. , “Possible BAT origin of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2,” Emerg. Infectious Diseases, vol. 26, no. 7, p. 1542, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boni M. F.et al. , “Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic,” Nat. Microbiol., vol. 4, pp. 1408–1417, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lam T. T.-Y.et al. , “Identifying SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses in malayan pangolins,” Nature, vol. 583, pp. 282–285, Jul. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Worldometer. (2020). COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. [Online]. Available: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

- [11].Agence France Presse. (2020). Coronavirus: 4.5 Billion People Confined. [Online]. Available: https://www.barrons.com/news/coronavirus-4-5-billion-people-confined-01587139808

- [12].Cucinotta D. and Vanelli M., “Who declares COVID-19 a pandemic,” Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parmensis, vol. 91, no. 1, pp. 157–160, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhan C., Tse C., Fu Y., Lai Z., and Zhang H., “Modelling and prediction of the 2019 coronavirus disease spreading in china incorporating human migration data,” PLoS ONE, vol. 15, no. 10, 2020, Art. no. e0241171, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fattorini D. and Regoli F., “Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the COVID-19 outbreak risk in Italy,” Environ. Pollution, vol. 264, Sep. 2020, Art. no. 114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bai Y.et al. , “Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19,” J. Amer. Med. Assoc., vol. 323, no. 14, pp. 1406–1407, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rothe C.et al. , “Transmission of 2019-NCOV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany,” New England J. Med., vol. 382, no. 10, pp. 970–971, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hellewell J.et al. , “Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts,” Lancet Global Health, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 488–496, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mallapaty S., “Antibody tests suggest that coronavirus infections vastly exceed official counts,” Nature, to be publilshed. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [19].Peto J., “COVID-19 mass testing facilities could end the epidemic rapidly,” BMJ, vol. 368, Mar. 2020, Art. no. m1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].World Health Organization. (2020). COVID-19 Strategy Update 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/covid-strategy-update-14april2020.pdf

- [21].Callaway E., “The unequal scramble for coronavirus vaccines-by the numbers,” Nature, vol. 584, no. 7822, pp. 506–507, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Walker P. G.et al. , “The impact of COVID-19 and strategies for mitigation and suppression in low-and middle-income countries,” Science, vol. 369, no. 6502, pp. 413–422, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ali S. T.et al. , “Serial interval of SARS-CoV-2 was shortened over time by nonpharmaceutical interventions,” Science, vol. 369, no. 6507, pp. 1106–1109, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Baker R. E., Yang W., Vecchi G. A., Metcalf C. J. E., and Grenfell B. T., “Susceptible supply limits the role of climate in the early SARS-CoV-2 pandemic,” Science, vol. 369, no. 6501, pp. 315–319, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhan C., Zheng Y., Lai Z., Hao T., and Li B., “Identifying epidemic spreading dynamics of COVID-19 by pseudocoevolutionary simulated annealing optimizers,” Neural Comput. Appl., to be published. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [26].Prem K.et al. , “The effect of control strategies to reduce social mixing on outcomes of the COVID-19 epidemic in Wuhan, China: A modelling study,” Lancet Public Health, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 261–270, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Carlson C. J., Dougherty E., Boots M., Getz W., and Ryan S. J., “Consensus and conflict among ecological forecasts of zika virus outbreaks in the united states,” Sci. Rep., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ardabili S. F.et al. , “COVID-19 outbreak prediction with machine learning,” in Proc. SSRN, 2020, Art. no. 3580188. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Alimadadi A., Aryal S., Manandhar I., Munroe P. B., Joe B., and Cheng X., “Artificial intelligence and machine learning to fight COVID-19,” Phys. Genom., vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 200–202, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ribeiro M. H. D. M., da Silva R. G., Mariani V. C., and dos Santos Coelho L., “Short-term forecasting COVID-19 cumulative confirmed cases: Perspectives for brazil,” Chaos Solitons Fractals, vol. 135, Jun. 2020, Art. no. 109853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yan L.et al. , “An interpretable mortality prediction model for COVID-19 patients,” Nat. Mach. Intell., vol. 2, pp. 283–288, May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Iwendi C.et al. , “COVID-19 patient health prediction using boosted random forest algorithm,” Front. Public Health, vol. 8, p. 357, Jul. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Beck B. R., Shin B., Choi Y., Park S., and Kang K., “Predicting commercially available antiviral drugs that may act on the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) through a drug-target interaction deep learning model,” Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J., vol. 18, pp. 784–790, Mar. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rivas A., “Drones and artificial intelligence to enforce social isolation during COVID-19 outbreak,” Medium Towards Data Sci., vol. 26, Mar. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Vespignani A.et al. , “Modelling COVID-19,” Nat. Rev. Phys., vol. 2, no. 6, Jun. 2020, pp. 279–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zheng N.et al. , “Predicting COVID-19 in China using hybrid Ai model,” IEEE Trans. Cybern., vol. 50, no. 7, pp. 2891–2904, Jul. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Chimmula V. K. R. and Zhang L., “Time series forecasting of COVID-19 transmission in Canada using LSTM networks,” Chaos Solitons Fractals, vol. 135, Jun. 2020, Art. no. 109864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Pinter G., Felde I., Mosavi A., Ghamisi P., and Gloaguen R., “COVID-19 pandemic prediction for hungary; a hybrid machine learning approach,” Mathematics, vol. 8, no. 6, p. 890, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jahanbin K. and Rahmanian V., “Using Twitter and Web news mining to predict COVID-19 outbreak,” Asian Pac. J. Tropical Med., vol. 13, no. 8, pp. 378–380, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lazer D., Kennedy R., King G., and Vespignani A., “The parable of Google flu: Traps in big data analysis,” Science, vol. 343, no. 6176, pp. 1203–1205, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Naudé W., “Artificial intelligence vs COVID-19: Limitations, constraints and pitfalls,” Ai Soc., vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 761–765, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chen C. P. and Liu Z., “Broad learning system: An effective and efficient incremental learning system without the need for deep architecture,” IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 10–24, Jan. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Xu M., Han M., Chen C. L. P., and Qiu T., “Recurrent broad learning systems for time series prediction,” IEEE Trans. Cybern., vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 1405–1417, Apr. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ghazaly N. M., Abdel-Fattah M. A., and Abd El-Aziz A., “Novel coronavirus forecasting model using nonlinear autoregressive artificial neural network,” J. Adv. Sci., vol. 29, no. 5s, pp. 1831–1849, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Hu Z., Ge Q., Li S., Boerwinkle E., Jin L., and Xiong M., “Forecasting and evaluating multiple interventions for COVID-19 worldwide,” Front. Artif. Intell., vol. 3, p. 41, May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]