Abstract

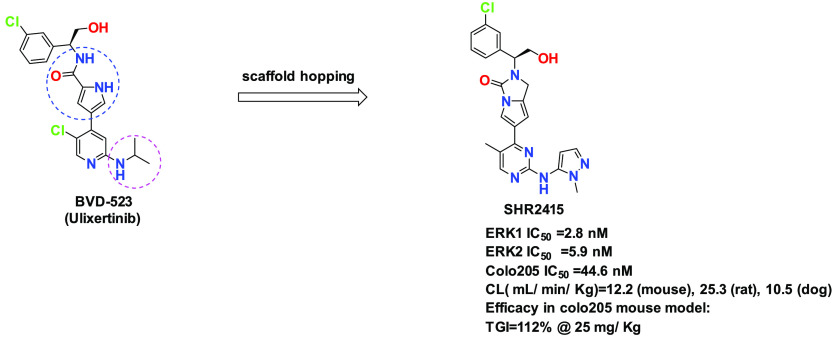

ERK1/2 kinase is a key downstream node of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway. A highly potent and selective ERK1/2 inhibitor is a promising option for cancer treatment that will provide a potential solution for overcoming drug resistance. Herein we designed and synthesized a novel scaffold featuring a pyrrole-fused urea template. The lead compound, SHR2415, was shown to be a highly potent ERK1/2 inhibitor that exhibited high cell potency based on the Colo205 assay. In addition, SHR2415 displayed favorable PK profiles across species as well as robust in vivo efficacy in a mouse Colo205 xenograft model.

Keywords: ERK kinase, inhibitor, MAPK pathway, cancerl, SHR2415

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) from the mitogen-activated protein kinase family are key downstream nodes in the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK (MAPK) signaling pathway. When the pathway is triggered by an exocellular signal, ERK1/2 are activated by MEK1 and MEK2 via phosphorylation. The activated ERK1/2 then regulate a series of biological processes, such as cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and migration.1,2

Continued activation of the MAPK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations, such as RAS and RAF mutations, may promote the malignant transformation and abnormal proliferation of cells ultimately leading to tumors.3 Small molecule inhibitors targeting MAPK upstream kinases, such as BRAF and MEK, have shown promising efficacy for cancer treatment in the clinic setting. Recently, the combination of BRAF and MEK inhibitors was shown to significantly improve the overall response rate and prolong the progression-free survival and overall survival for melanoma and lung cancer patients with BRAF V600E or V600 K mutations;4−6 however, drug resistance and disease progression were observed within 12 months.6,7 The mechanisms underlying the resistance phenomenon are complicated, most of which rely on reactivation of ERK signaling.8,9 Therefore, direct inhibition of ERK may provide not only a promising cancer treatment option but also a potential solution for drug resistance in combination with MAPK upstream kinase inhibitor treatment. In addition, ERK inhibitors may have clinical benefits in combination with other MAPK inhibitors or the combination of immune checkpoint antibody molecules, such as anti-PD-1 and -CTLA4 antibodies, similar to the important synergies shown by upstream MAPK inhibitors.4,10,11

Driven by the promising therapeutic prospect of ERK inhibitors, a number of compounds (Figure 1) have been developed in clinical trials, such as BVD-523,12 GDC-0994,13 LY3214996,14 AZD0364,15 MK8353,16 KO-947,17 CC-90003,18 and others.19−24 The identification of novel and potent ERK1/2 inhibitors with favorable ADME properties continues to be an area of great interest for drug discovery efforts in oncology.

Figure 1.

Selection of ERK1/2 inhibitors in clinical trials.

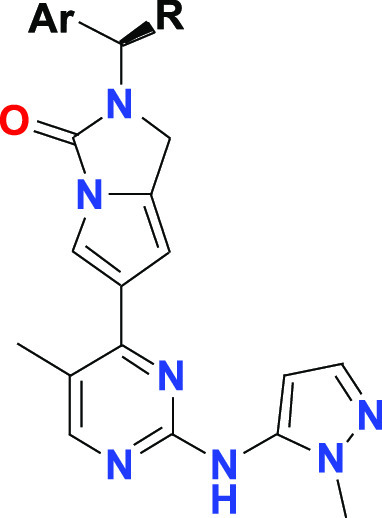

Enlightened by the structures of reported ERK1/2 inhibitors (Figure 1), we designed and synthesized new derivatives with a focus on core exploration. These efforts afforded a novel structure, featuring a pyrrole-fused urea template. The elaboration of this scaffold delivered the key compound, SHR2415, which was selected for further in vivo studies. As shown in Table 1, a saturated ring, such as piperazinone (1) and proline amide (2), were introduced to mimic the central core of BVD-523. It was found that the cell activity was lost completely. Next, a six-membered lactam (3) was investigated, which resulted in high biochemical inhibition activity for ERK2 (IC50 = 9.2 nM); however, restoration of cell potency was not being satisfied. Based on this result, a five-membered lactam (4) was also being evaluated. Out of our expectation, the biochemical potency decreased dramatically compared with 3. Subsequently, a pyrazole fused with a pyrrole as a central core provided a moderately potent compound (5), which underwent methyl substitution to afford analog 6. This compound showed less potent data in cell based assay (Colo205 IC50 = 964 nM). Thus, a new strategy was utilized by introducing a pyrrole-fused urea scaffold as a central core. To our knowledge, this building block was novel. The pyrrole-fused six-membered urea ring (7) exhibited high ERK2 inhibition activity, as well as cellular potency (Colo205 IC50 = 77.1 nM).Then a five-membered urea ring (8) was therefore prepared and the cellular potency was further enhanced (Colo205 IC50 = 44.6 nM). In addition, pyrrole was replaced with imidazole, which yielded compound 9 with potency lost completely. It appeared that the pyrrole core was very sensitive; minor changes with one fluoride substitution on the pyrrole (10) resulted in decreased potency.

Table 1. ERK2 Inhibition Activity of Central Core Modificationa.

All IC50 data are the mean of at least two independent measurements with variations of <15%; BVD-523 as positive control (EK2 IC50 = 10.6 nM; Colo 205 IC50 = 102.7 nM).

Enantiomer mixtures.

Therefore, the five-membered urea fused with the pyrrole was selected as the core template for further SAR studies (Table 2). Modification of the pyrimidine substitution was achieved by switching the methyl group for the chloride group (compound 11). In so doing, the most potent compound in this series was generated (ERK2 IC50 = 3 nM). Next, the different amine groups (R1) on pyrimidine were also screened. The cell potency (12, 13) decreased approximately 3-fold compared with compound 11. The trend was clear that an aromatic R1 was better than the aliphatic group (8 vs 15). Additionally, the tail group from BVD-523 (compound 16) was evaluated at the same time; however, the potency was significantly decreased.

Table 2. ERK2 Inhibition Activity of Tail Group Modificationa.

All IC50 data are the mean of at least two independent measurements with variations of <15%.

After optimization of the central core and tail group, we continued screening on the head groups as shown in Table 3. The bis-halide or methoxy substitution on benzene was prepared and evaluated. These compounds (17–19) possessed slightly lower cell potency compared with compound 8. Based on the results of 20 and 21, it was clearly shown that the methylene hydroxyl group was important for potency. Furthermore, replacing the hydroxyl group with methyl amine was also attempted and the biochemical inhibition activity of 22 was very high (ERK2 IC50 = 1.5 nM), while the cellular activity likely decreased due to permeability. After removal of the methyl group to produce a primary amine, the ERK2 inhibition activity decreased further (23).

Table 3. ERK2 Inhibition Activity of Head Group Modificationa.

All IC50 data are the mean of at least two independent measurements with variations of <15%.

Based on the overall data, compound 8, hereafter referred to as SHR2415, was selected as the lead compound for further evaluation. As shown in Table 4, SHR2415 displayed highly potent ERK1 and ERK2 activity in the biochemical and cellular assay, which was further confirmed by downstream activity data (pRSK/tRSK IC50 = 223.6 nM).

Table 4. Profiles of SHR2415.

| compd ID | SHR2415 |

| ERK1 IC50 (nM) | 2.75 ± 0.35 (n = 5) |

| ERK2 IC50 (nM) | 5.93 ± 0.87 (n = 4) |

| Colo205 IC50 (nM) | 44.60 ± 6.49 (n = 3) |

| pRSK/tRSK IC50 (nM) | 223.6 |

| CDK2 IC50 (nM) | 99.4 |

| GSK3 beta IC50 (nM) | 64.3 |

| human PPB (%) | 98.4 |

| hERG (μM) | 14 |

| CYP450 IC50 (μM) | 2D6 > 30; 3A4 (m):a 11.5; 3A4 (t):b 5.4 |

m: Midazolam.

t: Testosterone.

The ERK1 kinase selectivity of SHR2415 was also acceptable with a 36-fold increase over CDK2 kinase and 23-fold increase over GSK3K beta kinase. The human plasma protein binding (PPB) data of SHR2415 was also collected (PPB% = 98%). Moreover, the cytochrome P450 inhibition of SHR2415 was investigated to assess the potential DDIs with major CYP isoforms. SHR2415 was shown to have no apparent CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 inhibition with IC50 values > 5 μM except CYP2C9 (IC50 = 0.79 μM). In contrast, high-potency compound 11 showed 0.35 μM CYP2D6 inhibition with other CYP isoforms inhibition IC50 values >5 μM. It seems SHR2415 had slightly less potential DDI liability, compared with 11. The hERG IC50 of SHR2415 was approximately 14 μM, suggesting a relatively high cardiac safety margin.

As summarized in Table 5, SHR2415 also displayed a favorable PK profile across species with low clearance and good in vivo exposure (AUC = 2460 ng/mL·h in mice; AUC = 726 ng/mL·h in rats; AUC = 3271 ng/mL·h in dogs), which further confirmed the suitability for the following development. Considering the high potency compound 7 had similar urea scaffold as compound 8, by curiosity, its PK profiles have also been investigated which showed clearly inferior result to the corresponding five-membered urea structure (8).

Table 5. In Vivo Pharmacokinetics Data of SHR2415 and Compound 7a.

| compd ID |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHR2415 | compd 7 | ||||

| species | mouse | rat | dog | mouse | rat |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 604 | 219 | 526 | 275 | 84.3 |

| AUC0–t p.o. (ng/mL·h) | 2460 | 726 | 3271 | 277 | 258 |

| t1/2 p.o. (h) | 3.5 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 0.82 | 1.6 |

| CL (mL/min/kg) | 12.2 | 25.3 | 10.5 | 63.1 | 38.5 |

| F (%) | 90.8 | 45.8 | 101 | 54 | 29.4 |

p.o. is oral administration; i.v. is intravenous administration; CL is clearance of i.v.; t1/2 is the half-life of the compound exposure in plasma; AUC is the area under the curve. The i.v. dosage for mouse and rat was 1 mg/kg and for dog was 0.5 mg/kg. The p.o. dosage for mouse, rat, and dog was 2 mg/kg.

Furthermore, SHR2415 was investigated in a Balb/c mouse Colo205 tumor xenograft model to evaluate the therapeutic effect (Figure 2). In agreement with the high in vitro inhibition activity, SHR2415 displayed remarkable efficacious characteristics at 25 and 50 mg/kg doses. It appeared that SHR2415 might reach its efficacy plateau at 50 mg/kg. In addition, SHR2415 exhibited better efficacy at a 25 mg/kg dose (TGI = 112%) than BVD-523 at a 50 mg/kg dose (TGI = 63%), likely due to the higher cell potency compared with BVD-523 (see Table 1). Another benefit of SHR2415 was that it displayed a high AUC-tumor:AUC-plasma ratio (1.42 vs 0.43).

Figure 2.

Efficacy of SHR2145 in a Colo205 xenograft model on Balb/c mice and end point study of PK data (n = 9).

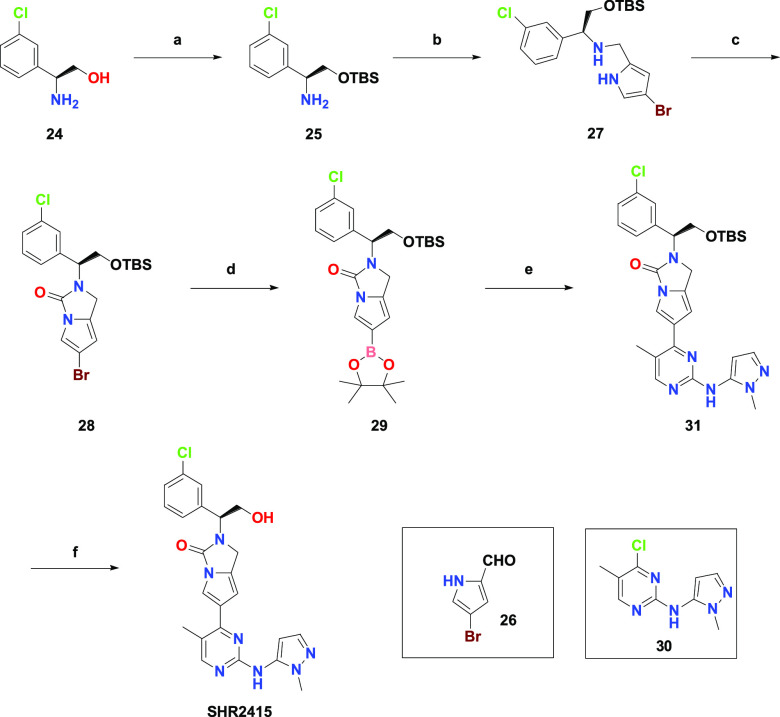

The synthesis of SHR2415 was straightforward, as shown in Scheme 1. In the six-step synthesis, the key building block (29) was required. Starting from the commercially available chiral alcohol (24), TBS protection and reductive amination with aldehyde 26 resulted in a good yield of compound 27. Subsequently, urea (28) was obtained via cyclization under basic conditions. Next, the following Miyaura borylation of compound 28 provided boronic ester (29), which when coupled with intermediate 30 successfully delivered compound 31. Finally, SHR2415 was produced by removal of the TBS group under acid conditions.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Route of SHR2415.

Reagents and conditions: (a) TBSCl, imidazole, DCM, r.t. 14h, 97% (b) 25 and 26, MeOH, r.t. 2h then NaBH4, 0 °C, 2h, 79% (c) NaH, 1,1′-Carbonyldiimidazole, THF, r.t. 14h, 78% (d) Pd(dppf)Cl2, bis(pinacolato)diboron, potassium acetate, dioxane, 90 °C, N2, 2h, 45% (e) 30, Pd(dppf)Cl2, cesium carbonate, dioxane, H2O, 80 °C, N2, 14h, 74% (f) TFA, DCM, r.t. 4h, 44%

In summary, we described the discovery of ERK1/2 inhibitors with a novel pyrrole-fused urea template. As a lead compound, SHR2415 exhibited high potency based on the ERK1/2 enzyme and Colo205 cell line assays. In addition, SHR2415 displayed a favorable PK profile across species as well as robust efficacy in the mouse Colo205 tumor xenograft model. Further, a preclinical study of SHR2415, such as efficacy with additional cancer cell lines or in combination with other MAPK inhibitors, will be under investigation in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hong Wan, Zhendong Xue, Dongdong Bai, Binqiang Feng, and the whole ERK project team for their contributions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinases

- ADME

absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- DDI

drug–drug interaction

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- AUC

area under curve

- TGI

tumor growth inhibition

- TBS

tert-butyldimethylsilyl

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00029.

Synthetic procedures, analytical data, in vitro assay protocol, in vivo pharmacokinetic studies, in vivo efficacy model details (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Roskoski R. Jr. ERK1/2 MAP kinases: structure, function, and regulation. Pharmacol. Res. 2012, 66 (2), 105–143. 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon A. S.; Hagan S.; Rath O.; Kolch W. MAP kinase signaling pathways in cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26 (22), 3279–3290. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts P. J.; Der C. J. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26 (22), 3291–3310. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert C.; Karaszewska B.; Schachter J.; Rutkowski P.; Mackiewicz A.; Stroiakovski D.; Lichinitser M.; Dummer R.; Grange F.; Mortier L.; Chiarion-Sileni V.; Drucis K.; Krajsova I.; Hauschild A.; Lorigan P.; Wolter P.; Long G. V.; Flaherty K.; Nathan P.; Ribas A.; Martin A. M.; Sun P.; Crist W.; Legos J.; Rubin S. D.; Little S. M.; Schadendorf D. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372 (1), 30–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planchard D.; Smit E. F.; Groen H. J. M.; Mazieres J.; Besse B.; Helland A.; Giannone V.; D’Amelio A. M. Jr.; Zhang P.; Mookerjee B.; Johnson B. E. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously untreated BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18 (10), 1307–1316. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30679-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies A. M.; Ashworth M. T.; Swann S.; Kefford R. F.; Flaherty K.; Weber J.; Infante J. R.; Kim K. B.; Gonzalez R.; Hamid O.; Schuchter L.; Cebon J.; Sosman J. A.; Little S.; Sun P.; Aktan G.; Ouellet D.; Jin F.; Long G. V.; Daud A. Characteristics of pyrexia in BRAFV600E/K metastatic melanoma patients treated with combined dabrafenib and trametinib in a phase I/II clinical trial. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26 (2), 415–421. 10.1093/annonc/mdu529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long G. V.; Stroyakovskiy D.; Gogas H.; Levchenko E.; de Braud F.; Larkin J.; Garbe C.; Jouary T.; Hauschild A.; Grob J. J.; Chiarion-Sileni V.; Lebbe C.; Mandalà M.; Millward M.; Arance A.; Bondarenko I.; Haanen J. B.; Hansson J.; Utikal J.; Ferraresi V.; Kovalenko N.; Mohr P.; Probachai V.; Schadendorf D.; Nathan P.; Robert C.; Ribas A.; DeMarini D. J.; Irani J. G.; Swann S.; Legos J. J.; Jin F.; Mookerjee B.; Flaherty K. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015, 386 (9992), 444–451. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60898-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little A. S.; Smith P. D.; Cook S. J. Mechanisms of Acquired Resistance to ERK1/2 Pathway Inhibitors. Oncogene 2013, 32 (10), 1207–1215. 10.1038/onc.2012.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long G. V.; Fung C.; Menzies A. M.; Pupo G. M.; Carlino M. S.; Hyman J.; Shahheydari H.; Tembe V.; Thompson J. F.; Saw R. P.; Howle J.; Hayward N. K.; Johansson P.; Scolyer R. A.; Kefford R. F.; Rizos H. Increased MAPK reactivation in early resistance to dabrafenib/trametinib combination therapy of BRAF-mutant metastatic melanoma. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5694–5702. 10.1038/ncomms6694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick D. T.; Piris A.; Cogdill A. P.; Cooper Z. A.; Lezcano C.; Ferrone C. R.; Mitra D.; Boni A.; Newton L. P.; Liu C.; Peng W.; Sullivan R. J.; Lawrence D. P.; Hodi F. S.; Overwijk W. W.; Lizée G.; Murphy G. F.; Hwu P.; Flaherty K. T.; Fisher D. E.; Wargo J. A. BRAF inhibition is associated with enhanced melanoma antigen expression and a more favorable tumor microenvironment in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19 (5), 1225–1231. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni A.; Cogdill A. P.; Dang P.; Udayakumar D.; Njauw C. N.; Sloss C. M.; Ferrone C. R.; Flaherty K. T.; Lawrence D. P.; Fisher D. E.; Tsao H.; Wargo J. A. Selective BRAFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without affecting lymphocyte function. Cancer Res. 2010, 70 (13), 5213–5219. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germann U.; Furey B.; Roix J.; Markland W.; Hoover R.; Aronov A.; Hale M.; Chen G.; Martinez-Botella G.; Alargova R.; Fan B.; Sorrell D.; Meshaw K.; Shapiro P.; Wick M. J.; Benes C.; Garnett M.; DeCrescenzo G.; Namchuk M.; Saha S.; Welsch D. J. Abstract 4693: The Selective ERK Inhibitor BVD-523 is Active in Models of MAPK Pathway-Dependent Cancers, Including Those with Intrinsic and Acquired Drug Resistance. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 4693–4693. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2015-4693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake J. F.; Burkard M.; Chan J.; Chen H.; Chou K.-J.; Diaz D.; Dudley D. A.; Gaudino J. J.; Gould S. E.; Grina J.; Hunsaker T.; Liu L.; Martinson M.; Moreno D.; Mueller L.; Orr C.; Pacheco P.; Qin A.; Rasor K.; Ren L.; Robarge K.; Shahidi-Latham S.; Stults J.; Sullivan F.; Wang W.; Yin J.; Zhou A.; Belvin M.; Merchant M.; Moffat J.; Schwarz J. B. Discovery of (S)-1-(1-(4-Chloro-3- fluorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethyl)-4-(2-((1-methyl-1H-pyrazol-5-yl)- amino)pyrimidin-4-yl)pyridin-2(1H)-one (GDC-0994), an Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) Inhibitor in Early Clinical Development. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (12), 5650–5660. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwat S. V.; McMillen W. T.; Cai S.; Zhao B.; Whitesell M.; Shen W.; Kindler L.; Flack R. S.; Wu W.; Anderson B.; Zhai Y.; Yuan X. J.; Pogue M.; Van Horn R. D.; Rao X.; McCann D.; Dropsey A. J.; Manro J.; Walgren J.; Yuen E.; Rodriguez M. J.; Plowman G. D.; Tiu R. V.; Joseph S.; Peng S. B. ERK Inhibitor LY3214996 Targets ERK Pathway-Driven Cancers: A Therapeutic Approach Toward Precision Medicine. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2020, 19 (2), 325–336. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R. A.; Anderton M. J.; Bethel P.; Breed J.; Cook C.; Davies E. J.; Dobson A.; Dong Z.; Fairley G.; Farrington P.; Feron L.; Flemington V.; Gibbons F. D.; Graham M. A.; Greenwood R.; Hanson L.; Hopcroft P.; Howells R.; Hudson J.; James M.; Jones C. D.; Jones C. R.; Li Y.; Lamont S.; Lewis R.; Lindsay N.; McCabe J.; McGuire T.; Rawlins P.; Roberts K.; Sandin L.; Simpson I.; Swallow S.; Tang J.; Tomkinson G.; Tonge M.; Wang Z.; Zhai B. Discovery of a Potent and Selective Oral Inhibitor of ERK1/2 (AZD0364) That Is Efficacious in Both Monotherapy and Combination Therapy in Models of Nonsmall Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62 (24), 11004–11018. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boga S. B.; Deng Y.; Zhu L.; Nan Y.; Cooper A. B.; Shipps G. W. Jr.; Doll R.; Shih N. Y.; Zhu H.; Sun R.; Wang T.; Paliwal S.; Tsui H. C.; Gao X.; Yao X.; Desai J.; Wang J.; Alhassan A. B.; Kelly J.; Patel M.; Muppalla K.; Gudipati S.; Zhang L. K.; Buevich A.; Hesk D.; Carr D.; Dayananth P.; Black S.; Mei H.; Cox K.; Sherborne B.; Hruza A. W.; Xiao L.; Jin W.; Long B.; Liu G.; Taylor S. A.; Kirschmeier P.; Windsor W. T.; Bishop R.; Samatar A. A. MK-8353: Discovery of an Orally Bioavailable Dual Mechanism ERK Inhibitor for Oncology. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9 (7), 761–767. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X.; Ren P.; Mai W.; Wang Y.; Zhang Y.; Wu H.; Xie Y.; Chen H. From Lab Formulation Development to CTM Manufacturing of KO-947 Injectable Drug Products: a Case Study and Lessons Learned. AAPS PhamSciTech 2021, 22 (5), 168. 10.1208/s12249-021-02059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronchik I.; Dai Y.; Malek M.; Mavrommatis K.; Bray G. L.; Filvaroff E. H.; Labenski M.; Barnes C.; Jones T.; Qiao L.; Beebe L.; Elis W.; Shi T. Efficacy of a Covalent ERK1/2 Inhibitor, CC-90003, in KRAS-Mutant Cancer Models Reveals Novel Mechanisms of Response and Resistance. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17 (2), 642–654. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heightman T. D.; Berdini V.; Bevan L.; Buck I. M.; Carr M. G.; Courtin A.; Coyle J. E.; Day J. E. H.; East C.; Fazal L.; Griffiths-Jones C. F.; Howard S.; Kucia-Tran J.; Martins V.; Muench S.; Munck J. M.; Norton D.; O’Reilly M.; Palmer N.; Pathuri P.; Peakman T. M.; Reader M.; Rees D. C.; Rich S. J.; Shah A.; Wallis N. G.; Walton H.; Wilsher N. E.; Woolford A. J.; Cooke M.; Cousin D.; Onions S.; Shannon J.; Watts J.; Murray C. W. Discovery of ASTX029, A Clinical Candidate Which Modulates the Phosphorylation and Catalytic Activity of ERK1/2. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64 (16), 12286–12303. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of HH2710 in Patient With Advanced Tumors. ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04198818.

- A Study of ASN007 in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors. ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03415126.

- A Phase I Clinical Study With Investigational Compound LTT462 in Adult Patients With Specific Advanced Cancers. ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02711345.

- JSI-1187-01 Monotherapy and in Combination With Dabrafenib for Advanced Solid Tumors With MAPK Pathway Mutations. ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04418167.

- Miao L.; Tian H. Development of ERK1/2 inhibitors as a therapeutic strategy for tumour with MAPK upstream target mutations. J. Drug Target. 2020, 28 (2), 154–165. 10.1080/1061186X.2019.1648477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.