Abstract

Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) is a potential target for anticancer drugs. However, as an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) whose tertiary structure cannot be solved, innovative strategies are needed. We focused on its hydrophobic α-helix structure, defined as an induced helical motif (IHM), which is a possible interface for protein–protein interaction. Using mathematical analyses predicting the α-helix’s structure and hydrophobicity, a 4-amino-acid site (V-A-I-F) was identified as an IHM. Low-molecular-weight compounds that mimic the main chain conformation of the α-helix with the four side chains of V-A-I-F were synthesized using bicyclic pyrazinooxadiazine-4,7-dione. These compounds selectively suppressed the proliferation and survival of cancer cells but not noncancer cells and decreased the protein but not mRNA levels of KLF5 in addition to reducing proteins of Wnt signaling. The compounds further suppressed transplanted colorectal cancer cells in vivo without side effects. Our approach appears promising for developing drugs against key IDPs.

Keywords: KLF5, induced helical motif, intrinsically disordered protein, targeting undruggable protein

We developed novel anticancer drugs, NC compounds, against transcription factor KLF5, an intrinsically disordered protein, based on the predicted hydrophobic α-helix structure. The 4-amino-acid sequence in KLF5, V-A-I-F, was identified as the target site. Chemical compounds were synthesized by modulating the four side chains of bicyclic pyrazinooxadiazine-4,7-dione. The compounds selectively suppressed the proliferation of human colorectal cancer cells but not that of noncancer cells. They decreased the levels of the KLF5 protein and the proteins of the Wnt signaling pathway in cancer cells. The compounds effectively suppressed transplanted colorectal cancer cells in vivo without apparent side effects. We report a promising approach for developing drugs against intrinsically disordered key molecules.

Numerous cancers are caused by the genetic and epigenetic instability of key proteins, including those of transcription factors.1 Transcription factors, because of their excessive activation or frequent dysfunction, are potential targets for the development of anticancer agents. The therapeutic regulation of transcription factors has been successful for nuclear receptors.2 However, targeting DNA-binding transcription factors is challenging because most transcription factors are intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) and lack rigid small molecule-binding pockets.3

Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) belongs to a family of zinc-finger-containing transcription factors that mediate diverse cellular functions.4 We previously reported that KLF5, an essential regulator of intestinal oncogenesis at the stem cell level in mice with intestinal stem cell-specific ablation of the KLF5 gene, prevented Wnt signal-driven tumor formation.5 KLF5 expression was markedly enhanced in human colorectal cancer compared with normal colonic epithelia. Focal genomic amplification of the KLF5 gene locus frequently occurs in human colon cancers.5−6b These results collectively suggest that KLF5 may be a potential therapeutic target against colorectal cancer.7−7c However, because KLF5 is an IDP, its tertiary structure has not been determined.8−9 Therefore, we used a strategy of suppressing the protein–protein interaction (PPI) of KLF5 to develop inhibitory compounds, as inhibitors of PPI have been successfully developed in several key molecules (e.g., β-catenin/CREB-binding protein inhibitors).10−11b

Many IDPs are considered to undergo a disorder-to-order transition upon binding to protein partners, which are referred to as molecular recognition features.12 One of the targets is the α-helix, which constitutes a large class of secondary protein structures, because it is exposed on the surface of proteins and frequently interacts with other proteins.13−13c Several low-molecular-weight compounds with structures similar to an α-helix have been reported to inhibit disease-related molecules.14−15

In the present study, we developed low-molecular-weight compounds mimicking a mathematically predicted induced helical motif (IHM) in the KLF5 protein. We here demonstrate that these compounds suppress colorectal cancer cells in vitro and in vivo without apparent side effects. We also show that these compounds reduce the protein levels of Wnt signaling pathways and KLF5.

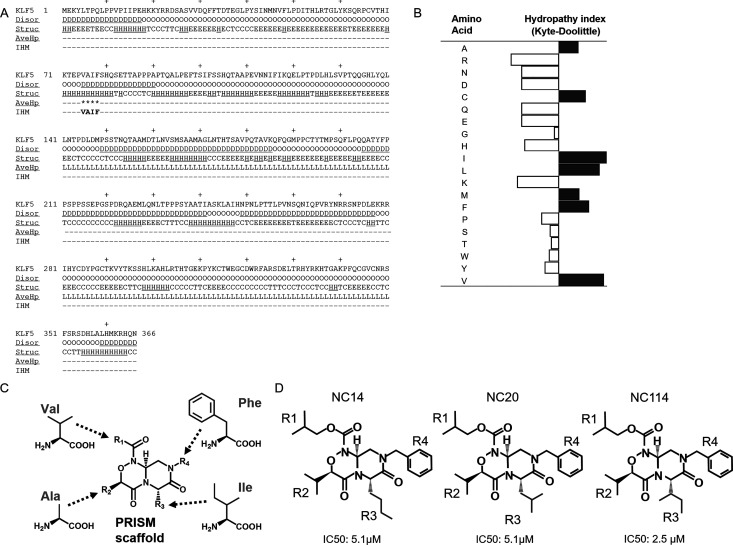

We predicted short α-helical regions with high hydrophobicity in the IDP region that may constitute IHMs when interacting with other proteins. The IHM in the KLF5 protein was predicted using a sequence-based prediction method, as illustrated in Figure 1A. Three criteria were used for IHM identification: [1] that the region is intrinsically disordered as calculated using a protein disorder prediction server (PrDOS);16 [2] that the region has a tendency to form a short α-helix as calculated using Chou and Fasman secondary structure prediction;17 and [3] the region has high hydrophobicity when calculated by using the Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy index (Figure 1B).18 Based on these criteria, we identified the amino acid sequence 75-V-A-I-F-78 in KLF5 as a predicted IHM (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Prediction of the induced helical motif (IHM) in the KLF5 protein and design of low-molecular-weight compounds based on the predicted IHM in KLF5. (A) The IHM in KLF5 was identified based on IDR prediction (Disor), secondary structure prediction (Struct), and average hydrophobicity (AveHp). In the “Disor” lines, “D” and “O” indicate disordered and ordered regions, respectively. In the “Struct” lines, “H”, “E”, “T”, and “C” indicate the helix, sheet, turn, and coil, respectively. In the “AveHp” lines, “*” indicates a region with an average hydrophobicity equal to or greater than the threshold value. The amino acid sequence “V-A-I-F” was predicted to be an IHM. (B) The hydrophobicity of amino acids plotted using a hydropathy index (Kyte-Doolittle). (C) Structures of the compounds with a bicyclic pyrazinooxadiazine-4,7-dione, namely, the PRISM scaffold, and the four side chains corresponding to the side chain structure of the target amino acid site. (D) Chemical structures of NC14, NC20, and NC114, which were designed as small-molecule α-helix mimetics based on the predicted IHM in KLF5. The half maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration (μM) in SW480 cells was examined at 72 h after treatment (cf. Figure 3A).

To construct low-molecular-weight compounds mimicking the V-A-I-F sequence, we used the PRISM scaffold (a bicyclic pyrazinooxadiazine-4,7-dione) as a template (Figure 1C)15,19 with a structure similar to that of a standard α-helix with the backbone of dihedral angles of −60° of phi and −45° of psi. We then added template derivatives of the side chains of the amino acids of the V-A-I-F sequence.

More than 60 small-molecular-weight compounds were synthesized by modulating four side chains attached to the bicyclic skeleton (Figure 1C,D). The four side chains of R1 to R4 have a chemical structure similar to that of the amino acid side chains of the target IHM, 75-VAIF-78. The compounds were synthesized via the synthetic route shown in Figure 2A. The detailed synthetic protocols of these molecules are described in the Supporting Information.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of NC114. (A) The following reagents and conditions were used in each step: a) NaBH(OAc)3 and dichloroethane; b) HATU, DIPEA, and CH2Cl2 (DCM); c) DEA and DCM; d) BnBr, Cs2CO3, and CH3CN; e) Ph3P, DIAD, and DCM; f) hydrazine hydrate and DCM; g) DMAP and DCM; h) H2, Pd/C, and MeOH; (i) HATU, DIEA, and DCM; and j) HCO2H.

The structures of the representative compounds NC14, NC20, and NC114 are shown in Figure 1D. The chemical structure of NC114 was also confirmed using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and the molecular weights of NC14, NC20, and NC114 were confirmed by mass spectrometry (Data S4 and S5 and Supporting Information).

Many of the developed NC compounds suppressed the proliferation of human colorectal cancer cells (SW480 and HCT116; Figure 3A), as shown on examination of growth of three-dimensional spheroids of human colorectal cancer cells (Figures 3B and S2A,B). Out of the synthesized compounds, NC114 showed the most potent antiproliferative effects on cancer cells with a half maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration of 2.5 μM (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Selective suppression of the proliferation of human colorectal cancer cells by NC compounds and effects of NC compounds on KLF5 protein levels. (A) Six representative NC compounds suppressed human colorectal cancer cells (SW480 and HCT116) without affecting the growth of noncancer cells (CCD841). The scores shown in (A) indicate the half maximal (50%) inhibitory concentration (μM) in SW480 cells examined at 72 h after treatment. Among the compounds, NC114 inhibited the proliferation of SW480 cells at the lowest concentration. NC25 had the same side chain chemical structure as NC14, but the only side chain at R4 was an optical isomer of that of NC14. (B) NC compounds (NC14, NC20, and NC22) suppressed the cell growth of the three-dimensional spheroids of human colorectal HCT116 cells as measured with a Cell3iMager Duos system (SCREEN). NC25 did not effectively suppress the growth of the spheroids.

Of particular interest, the NC compounds did not affect the survival of the noncancer cells (CCD841; Figure 3A). The differential effect of NC compounds between cancer and noncancer cell proliferation was dependent on the structures of R1 to R4 around the bicyclic skeletons. For instance, NC25 is an optical isomer of NC14 at R4, but the selective antiproliferative effect of NC14 was not observed in NC25 (Figure 3A).

We also examined the antiproliferative effects of Wnt signal inhibitors, compounds 1–11 and ICG-001, which were identified by using a TOP-Flash luciferase assay.11,11b These compounds had bicyclic skeletons identical with or close to the PRISM skeleton and suppressed the proliferation of both cancer and noncancer cells (Figures 3A and S1A).

The administration of NC compounds to human colon cancer cells resulted in significant decreases in the levels of KLF5, TCF4, Survivin, and phosphorylated β-catenin at Ser 552, which are involved in Wnt signaling and are critical to the survival of colorectal cancer cells (Figure 4A,C–E). NC114 also reduced the protein level of cyclin D1, an important cell cycle-promoting factor whose transcription is controlled by KLF5 (Figure 4F).20 In addition, phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser 552 or Ser 675, a hallmark of Wnt signaling activation, was reduced by NC compounds (Figure 4D–F). In addition, the protein level of β-catenin included in the purified FLAG/HA-KLF5 protein complex was attenuated by NC114 treatment of SW480 cells (Figure S3A,B). Interestingly, NC compounds did not reduce the mRNA levels of KLF5 in the cells (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of NC compounds on the levels of KLF5 and Wnt signaling. (A) NC compounds decreased the protein levels of KLF5 and Survivin in SW480 cells after treatment at 10 μM for 24 h but not in the human normal cell line, CCD841. The NC compounds that did not suppress the proliferation of human colorectal cancer cells (NC13 and NC25) did not decrease the protein levels of KLF5 or Survivin. (B) NC compounds (NC13, NC14, NC20, NC22, and NC25) did not decrease the KLF5 mRNA levels after treatment at 10 μM for 24 h in SW480 cells. (C) NC compounds (NC14, NC20, and NC22) decreased the protein levels of TCF4 in SW480 cells after treatment at 10 μM for 24 h. However, the TCF4 levels in the human normal cell line CCD841 did not change after the same treatment. (D) NC14, NC20, and NC22 suppressed the phosphorylation of Ser 552 on β-catenin in SW480 cells after treatment at 10 μM for 24 h. However, they did not decrease the β-catenin levels in SW480 cells. (E) NC compounds (NC102, NC108, NC109, NC14, NC114, and NC20) decreased the protein levels of KLF5, Survivin, and TCF4 and the phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser 552 after treatment at 10 μM for 24 h. Among these compounds, NC114 exhibited the most effective suppression. (F) Protein levels of cyclin D1 and KLF5 and phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser 675 in SW480 cells after treatment with NC114 for 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h. Cyclin D1 and KLF5 expressions and the phosphorylation of β-catenin at Ser 675 were attenuated by NC114 treatment. By contrast, protein levels and phosphorylation did not significantly decrease in CCD841 cells after NC114 treatment for 24 h.

Decreased levels of Wnt signaling-associated proteins after treatment with NC compounds were observed in cancer cells, with little, if any, effects on the human noncancer cell line CCD841 (Figure 4A,C,F). We further examined the antitumor profiles of the NC compounds across a panel of JFCR39 human cancer cell lines. COMPARE analysis (US National Cancer Institute) revealed that the antitumor fingerprint of NC14 was similar to that of LGK974 (r = 0.645), which is a Wnt pathway inhibitor (Table S1; Figure 4A,C–F).21−21c These results suggest that NC compounds suppress cancer cell proliferation through the inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway.22

The Wnt signaling pathway is one of the most critical targets for the treatment of human colorectal cancer,22−23b but drugs directly targeting Wnt signaling have been unsuccessful because of severe adverse effects.24,24b In the present study, the compounds with the PRISM scaffold screened by Wnt signaling inhibition did not show cancer cell-selective antiproliferative activities, which suggests that the presence of KLF5-dependent Wnt signaling is needed for cancer cell proliferation.

The differential antiproliferative effects of NC compounds are of notable interest, and whether these effects are due to KLF-dependent Wnt signaling unique to cancer cells warrants further elucidation. As KLF5 protein expression is enhanced in colorectal cancer cells, the differential effects of NC compounds between cancer and noncancer cells may be due to the difference in the abundance of KLF5 expression. In addition, the protein level of β-catenin in the KLF5 protein complex was attenuated by NC114 treatment. Therefore, the stability of the β-catenin-KLF5 protein complex may be impaired by treatment with NC compounds, which results in reduced levels of Wnt proteins.

Proteins binding to NC114 were identified by using NC114-bound beads (Data S1). We used the method of Kanoh et al.,25 which allows small molecules to be irreversibly photo-cross-linked to affinity beads in a functional group-independent manner. We then found ubiquitin-specific peptidase 3 (USP3) to be among the NC114-binding proteins. As USP3 is known to stabilize KLF5 by deubiquitination,26 we examined whether the USP3-KLF5 protein complex was inhibited by NC114 treatment. To detect the protein complex, we co-overexpressed FLAG/HA-KLF5 and Myc-tag-USP3 in HEK293T cells, and then the Myc-tag-USP3 protein complex was purified by immunoprecipitation (IP) from the cell lysate. As shown in Figure 5A, IP-Western blotting analysis revealed decreased amounts of KLF5 in the Myc-tag-USP3 protein complex after treatment with NC114 (Figure 5A,B).

Figure 5.

NC114 inhibited the formation of the USP3-KLF5 protein complex. (A) The Myc-tag-USP3 protein complex was purified by immunoprecipitation using an anti-Myc tag antibody in HEK293T cells overexpressing Myc tag-USP3 and FLAG/HA-KLF5 proteins. The Myc tag-USP3 protein complex contained the coimmunoprecipitated KLF5 protein, as confirmed by immunoprecipitation-Western blotting. (B) Relative quantity of the KLF5 protein per Myc-tag-USP3 protein in Myc-tag-USP3 protein complexes. NC114 treatment for 4 h at 20 μM attenuated the protein level of KLF5 in the USP3 protein complex. Quantification was performed after the presence of the KLF5 protein was confirmed by blotting. The protein level of KLF5 was not suppressed by NC114 treatment under the same conditions (4 h, 20 μM).

In the present study, we could not identify the molecular target of NC compounds, although many candidate proteins were identified by using a binding assay with NC114-bound beads in which both KLF5-related and non-KLF5-related proteins were included. Therefore, NC compounds may target multiple molecules simultaneously, as is the case with many low-molecular-weight drugs.

We also demonstrated that NC compounds reduced KLF5 protein levels but not KLF5 mRNA levels, which may be due in part to the impairment of KLF5-USP3 protein complex formation. However, we do not exclude the possibility that a decrease in KLF5 protein levels by other mechanisms may result in a decreased amount of KLF5 in the complex with USP3. Further investigation is needed to understand the molecular and pharmacological mechanisms of NC compounds.

To investigate the antitumor effect of NC114 in vivo, we administered NC114 intraperitoneally to nude mice subcutaneously transplanted with HT-29 human colorectal cancer cells. As shown in Figure 6A, the administration of NC114 significantly reduced tumor volume. To note, histological examination of the intestines revealed no abnormality in epithelial cell integrity or villi formation (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Suppression of tumor growth in vivo by NC114 treatment. (A) Thirteen nude mice were subcutaneously transplanted with HT29 human colon cancer cells (5 × 106) and then treated with NC114. NC114 was administered intraperitoneally (2 mg ×2/day for 8 days) to tumor-bearing mice. Tumor volumes were calculated as follows: short diameter 2 × long diameter/2. Tumor size was significantly smaller in the treated mice than in the untreated mice (n = 13). No side effects were observed. (B) Hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistological staining of KLF5 and Ki67 of the colons showing that the intestinal tissues of the NC114-treated mice had no significant cellular damage.

Considering these results, NC compounds are a potential new class of anticancer agents, as they selectively suppress the cancer-promoting function of the Wnt signaling pathway, with limited influence on physiological functions. This is a unique characteristic of NC compounds because many anticancer drugs used in standard chemotherapeutic regimens nonspecifically suppress the proliferation of both cancer and normal cells, thus causing serious side effects.23,23b,27 However, NC114 is a paste-like chemical compound with low solubility. Its chemical structure and characteristics need to be improved, possibly by using the same method used for PRI-724 which was developed from ICG-001 for clinical use.28

The KLF5 protein interacts with the USP3 protein on its N-terminal side, including the VAIF region.26 USP3 was identified as an NC compound-binding protein (Data S1). In contrast, ß-catenin was not detected as a significant NC compound-binding protein (Data S1). From this result, we speculate that NC compounds might interfere with KLF5 protein complex formation, at least in part, without direct interference with PPI.

As for the transcription coactivator proteins, the KLF5 protein has been previously reported to interact with p300 in its C-terminal side zinc finger/DNA-binding domain, excluding the VAIF region.29

Our method of drug development has been applied only to KLF5. Therefore, whether α-helix structure-mimicking compounds can be developed as drugs controlling intrinsically denatured key proteins needs to be elucidated in future studies. However, given that numerous cancers are promoted by dysregulation of oncogenic IDPs and as inhibitory drugs against them are unavailable at present, our approach is worthy of further research to develop new anticancer drugs and contribute to cancer biology.8,8b

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the helpful support of members of Jichi Medical University (especially Dr. Sei-ichi Hashimoto, Hiroyo Masuda, Yasuko Sakuma, Tomoko Kamiakito, Prof. Nobuhiko Ohno, Dr. Tomu Kouki, and Prof. Naoya Shibayama), PRISM BioLab (especially Dr. Tadashi Mishina, Yoichiro Hirose, and Dr. Hajime Takashima), the University of Tokyo, RIKEN (especially Kaori Honda), the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (especially Dr. Akihiro Tomida and Hideaki Toki), the Institute of Theoretical Medicine, the Oita University Institute of Advanced Medicine, Saitama Medical University (Dr. Takashi Murakami), and Kyoto University Innovation Capital (Dr. Nobuhiro Yagi).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00721.

Materials and methods: chemistry–prediction of IHMs, procedure for synthesis of NC114, and sample analyses by mass spectrometry; biology–materials, measurement of relative cell viability, Western blotting, RT-PCR, human colorectal cancer cell spheroid formation and measurement, tumor transplantation and measurement of tumors under NC114 medication, histopathological analysis, immunohistochemistry, purification of protein complex by immunoprecipitation, identification of NC114 bound proteins, and JFCR 39 cancer cell panel; Table S1, antitumor fingerprint of NC14 similar to that of LGK974, Wnt pathway inhibitor, in JFCR39 cancer cell line tests; legends for Data S1–S5; Supporting Information references; Figure S1, Wnt signal transcription inhibitors with PRISM scaffold did not selectively suppress cancer cells; Figure S2, NC compounds suppressed 3D spheroids of HCT116 cells; and Figure S3, NC114 inhibited USP3-KLF5 protein complex formation (PDF)

Data S1: identification of NC114 binding proteins (XLSX)

Data S2: gene expression changes in HT29 cells following NC114 treatment (XLSX)

Data S3: gene expression changes in HT29 cells following NC14 treatment (XLSX)

Data S4: confirmation of molecular mass of synthesized molecules (NC14, NC20, NC114) by low resolution mass spectrometry (LRMS) (PDF)

Data S5: confirmation of molecular mass of synthesized molecules (NC14, NC20, NC114) by high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) (PDF)

This study was financially supported by an AMED (P-CREATE) grant (19cm0106110h0004), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research Nos. 15H04824 to R.N., 16K08718, and 19K07512; the Mochida Foundation; the Princess Takamatsu Cancer Research Fund; the Fujii Memorial Foundation; the Takeda Foundation; the GSK Japan Research Grant; the Suzuken Foundation; the Kobayashi Foundation for Cancer Research; the Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research; the Sagawa Foundation; and the Okinaka Memorial Institute for Medical Research (to T.N.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Darnell J. E. Transcription factors as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2 (10), 740–749. 10.1038/nrc906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronemeyer H.; Gustafsson J. A.; Laudet V. Principles for modulation of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2004, 3 (11), 950–964. 10.1038/nrd1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley M. J.; Koehler A. N. Advances in targeting ’undruggable’ transcription factors with small molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2021, 20, 669. 10.1038/s41573-021-00199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai R.; Friedman S. L.; Kasuga M.. The biology of Krüppel-like factors; Springer Verlag, 2009; 10.1007/978-4-431-87775-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya T.; Ogawa S.; Manabe I.; Tanaka M.; Sanada M.; Sato T.; Taketo M. M.; Nakao K.; Clevers H.; Fukayama M.; Kuroda M.; Nagai R. KLF5 regulates the integrity and oncogenicity of intestinal stem cells. Cancer Res. 2014, 74 (10), 2882–2891. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Choi P. S.; Francis J. M.; Gao G. F.; Campbell J. D.; Ramachandran A.; Mitsuishi Y.; Ha G.; Shih J.; Vazquez F.; Tsherniak A.; Tayler A. M.; Zhou J.; Wu Z.; Berger A. C.; Giannakis M.; Hahn W. C.; Cherniack A. D.; Meyerson M. Somatic Superenhancer Duplications and Hotspot Mutations Lead to Oncogenic Activation of the KLF5 Transcription Factor. Cancer Discov 2018, 8 (1), 108–125. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.; Chen C. The roles and regulation of the KLF5 transcription factor in cancers. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112 (6), 2097–2117. 10.1111/cas.14910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y.; Ding Y.; Chen H. Y.; Chen H. J.; Zhou J. Targeting Kruppel-Like Factor 5 (KLF5) for Cancer Therapy. Curr. Top Med. Chem. 2015, 15 (8), 699–713. 10.2174/1568026615666150302105052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell B. B.; Yang V. W. Mammalian Kruppel-Like Factors in Health and Diseases. Physiol Rev. 2010, 90 (4), 1337–1381. 10.1152/physrev.00058.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi N.; Manabe I.; Tottori T.; Ishihara A.; Ogata F.; Kim J. H.; Nishimura S.; Fujiu K.; Oishi Y.; Itaka K.; Kato Y.; Yamauchi M.; Nagai R. A nanoparticle system specifically designed to deliver short interfering RNA inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 2009, 69 (16), 6531–6538. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M. E.; Romero P.; Ishida T.; Ghalwash M.; Mizianty M. J.; Xue B.; Dosztanyi Z.; Uversky V. N.; Obradovic Z.; Kurgan L.; Dunker A. K.; Gough J. (DP2)-P-2: database of disordered protein predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41 (D1), D508–D516. 10.1093/nar/gks1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iakoucheva L. M.; Brown C. J.; Lawson J. D.; Obradovic Z.; Dunker A. K. Intrinsic disorder in cell-signaling and cancer-associated proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 323 (3), 573–584. 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00969-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santofimia-Castano P.; Rizzuti B.; Xia Y.; Abian O.; Peng L.; Velazquez-Campoy A.; Neira J. L.; Iovanna J. Targeting intrinsically disordered proteins involved in cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77 (9), 1695–1707. 10.1007/s00018-019-03347-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojadzic D.; Buchwald P. Toward Small-molecule Inhibition of Protein-protein Interactions: General Aspects and Recent Progress in Targeting Costimulatory and Coinhibitory (Immune Checkpoint) Interactions. Curr. Top Med. Chem. 2018, 18 (8), 674–699. 10.2174/1568026618666180531092503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkin M. R.; Tang Y.; Wells J. A. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing toward the reality. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21 (9), 1102–1114. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkin M. R.; Wells J. A. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing towards the dream. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2004, 3 (4), 301–317. 10.1038/nrd1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin H.; Lee G. I.; Park H. S.; Payne G. A.; Rodriguez J. M.; Sebti S. M.; Hamilton A. D. Terphenyl-based helical mimetics that disrupt the p53/HDM2 interaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit 2005, 44 (18), 2704–2707. 10.1002/anie.200462316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emami K. H.; Nguyen C.; Ma H.; Kim D. H.; Jeong K. W.; Eguchi M.; Moon R. T.; Teo J. L.; Kim H. Y.; Moon S. H.; Ha J. R.; Kahn M. A small molecule inhibitor of beta-catenin/CREB-binding protein transcription [corrected]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101 (34), 12682–12687. 10.1073/pnas.0404875101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi M.; Nguyen C.; Lee S. C.; Kahn M. ICG-001, a novel small molecule regulator of TCF/beta-catenin transcription. Med. Chem. 2005, 1 (5), 467–472. 10.2174/1573406054864098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotta-Loizou I.; Tsaousis G. N.; Hamodrakas S. J. Analysis of Molecular Recognition Features (MoRFs) in membrane proteins. Bba-Proteins Proteom 2013, 1834 (4), 798–807. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guharoy M.; Chakrabarti P. Secondary structure based analysis and classification of biological interfaces: identification of binding motifs in protein-protein interactions. Bioinformatics 2007, 23 (15), 1909–1918. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jochim A. L.; Arora P. S. Assessment of helical interfaces in protein-protein interactions. Mol. Biosyst 2009, 5 (9), 924–926. 10.1039/b903202a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraogi I.; Hamilton A. D. alpha-Helix mimetics as inhibitors of protein-protein interactions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008, 36 (6), 1414–1417. 10.1042/BST0361414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings C. G.; Hamilton A. D. Disrupting protein-protein interactions with non-peptidic, small molecule alpha-helix mimetics. Curr. Opin Chem. Biol. 2010, 14 (3), 341–346. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzarito V.; Long K.; Murphy N. S.; Wilson A. J. Inhibition of alpha-helix-mediated protein-protein interactions using designed molecules. Nat. Chem. 2013, 5 (3), 161–173. 10.1038/nchem.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda H.; Kurita J.; Neyama H.; Hirao Y.; Kouji H.; Mishina T.; Kasai M.; Nakano H.; Yoshimori A.; Nishimura Y. A mimetic of the mSin3-binding helix of NRSF/REST ameliorates abnormal pain behavior in chronic pain models. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27 (20), 4705–4709. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T.; Kinoshita K. PrDOS: prediction of disordered protein regions from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W460–W464. 10.1093/nar/gkm363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar T. A. CFSSP: Chou and Fasman Secondary Structure Prediction server. Wide Spectrum 2013, 1 (9), 15–19. 10.5281/zenodo.50733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyte J.; Doolittle R. F. A Simple Method for Displaying the Hydropathic Character of a Protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982, 157 (1), 105–132. 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura M.; Uda-Tochio H.; Murai K.; Mori N.; Nishimura Y. The neural repressor NRSF/REST binds the PAH1 domain of the Sin3 corepressor by using its distinct short hydrophobic helix. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 354 (4), 903–915. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T.; Sawaki D.; Aizawa K.; Munemasa Y.; Matsumura T.; Ishida J.; Nagai R. Kruppel-like factor 5 shows proliferation-specific roles in vascular remodeling, direct stimulation of cell growth, and inhibition of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284 (14), 9549–9557. 10.1074/jbc.M806230200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori T.; Matsunaga A.; Sato S.; Yamazaki K.; Komi A.; Ishizu K.; Mita I.; Edatsugi H.; Matsuba Y.; Takezawa K.; Nakanishi O.; Kohno H.; Nakajima Y.; Komatsu H.; Andoh T.; Tsuruo T. Potent antitumor activity of MS-247, a novel DNA minor groove binder, evaluated by an in vitro and in vivo human cancer cell line panel. Cancer Res. 1999, 59 (16), 4042–4049. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker R. H. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6 (10), 813–823. 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong D. X.; Yamori T. JFCR39, a panel of 39 human cancer cell lines, and its application in the discovery and development of anticancer drugs. Bioorgan Med. Chem. 2012, 20 (6), 1947–1951. 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012, 487 (7407), 330–337. 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltz L. B.; Cox J. V.; Blanke C.; Rosen L. S.; Fehrenbacher L.; Moore M. J.; Maroun J. A.; Ackland S. P.; Locker P. K.; Pirotta N.; Elfring G. L.; Miller L. L. Irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. Irinotecan Study Group. N Engl J. Med. 2000, 343 (13), 905–914. 10.1056/NEJM200009283431302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz H.; Fehrenbacher L.; Novotny W.; Cartwright T.; Hainsworth J.; Heim W.; Berlin J.; Baron A.; Griffing S.; Holmgren E.; Ferrara N.; Fyfe G.; Rogers B.; Ross R.; Kabbinavar F. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J. Med. 2004, 350 (23), 2335–2342. 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusse R.; Clevers H. Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell 2017, 169 (6), 985–999. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn M. Can we safely target the WNT pathway?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2014, 13 (7), 513–532. 10.1038/nrd4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanoh N.; Honda K.; Simizu S.; Muroi M.; Osada H. Photo-cross-linked small-molecule affinity matrix for facilitating forward and reverse chemical genetics (vol 44, pg 3559, 2005). Angew. Chem. Int. Edit 2005, 44 (28), 4282–4282. 10.1002/anie.200590096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Qin J.; Li F.; Yang C.; Li Z.; Zhou Z.; Zhang H.; Li Y.; Wang X.; Liu R.; Tao Q.; Chen W.; Chen C. USP3 promotes breast cancer cell proliferation by deubiquitinating KLF5. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294 (47), 17837–17847. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.009102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florea A. M.; Busselberg D. Cisplatin as an anti-tumor drug: cellular mechanisms of activity, drug resistance and induced side effects. Cancers (Basel) 2011, 3 (1), 1351–1371. 10.3390/cancers3011351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa Y.; Oboki K.; Imamura J.; Kojika E.; Hayashi Y.; Hishima T.; Saibara T.; Shibasaki F.; Kohara M.; Kimura K. Inhibition of Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate (cAMP)-response Element-binding Protein (CREB)-binding Protein (CBP)/beta-Catenin Reduces Liver Fibrosis in Mice. EBioMedicine 2015, 2 (11), 1751–1758. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S.; Suzuki T.; Muto S.; Aizawa K.; Kimura A.; Mizuno Y.; Nagino T.; Imai Y.; Adachi N.; Horikoshi M.; Nagai R. Positive and negative regulation of the cardiovascular transcription factor KLF5 by p300 and the oncogenic regulator SET through interaction and acetylation on the DNA-binding domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23 (23), 8528–8541. 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8528-8541.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.