Abstract

The genetic circuits that allow cancer cells to evade destruction by the host immune system remain poorly understood1–3. Here, to identify a phenotypically robust core set of genes and pathways that enable cancer cells to evade killing mediated by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), we performed genome-wide CRISPR screens across a panel of genetically diverse mouse cancer cell lines that were cultured in the presence of CTLs. We identify a core set of 182 genes across these mouse cancer models, the individual perturbation of which increases either the sensitivity or the resistance of cancer cells to CTL-mediated toxicity. Systematic exploration of our dataset using genetic co-similarity reveals the hierarchical and coordinated manner in which genes and pathways act in cancer cells to orchestrate their evasion of CTLs, and shows that discrete functional modules that control the interferon response and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-induced cytotoxicity are dominant sub-phenotypes. Our data establish a central role for genes that were previously identified as negative regulators of the type-II interferon response (for example, Ptpn2, Socs1 and Adar1) in mediating CTL evasion, and show that the lipid-droplet-related gene Fitm2 is required for maintaining cell fitness after exposure to interferon-γ (IFNγ). In addition, we identify the autophagy pathway as a conserved mediator of the evasion of CTLs by cancer cells, and show that this pathway is required to resist cytotoxicity induced by the cytokines IFNγ and TNF. Through the mapping of cytokine- and CTL-based genetic interactions, together with in vivo CRISPR screens, we show how the pleiotropic effects of autophagy control cancer-cell-intrinsic evasion of killing by CTLs and we highlight the importance of these effects within the tumour microenvironment. Collectively, these data expand our knowledge of the genetic circuits that are involved in the evasion of the immune system by cancer cells, and highlight genetic interactions that contribute to phenotypes associated with escape from killing by CTLs.

Cancer cells must acquire phenotypic changes that allow them to evade recognition and destruction by effector cells of the immune system such as CTLs. These phenotypic changes not only facilitate the progressive expansion and dissemination of cancer cells during tumorigenesis, but also promote resistance to immunotherapies that harness the potent cytotoxic properties of CTLs, including checkpoint inhibitors and chimaeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cells. Previous genomic studies of patients with cancer who were treated with immunotherapy have provided fundamental insights into several mechanisms that promote immune evasion (for example, loss of antigen presentation machinery or defects in interferon signalling)4–6, but these studies are limited to the detection of frequently occurring genetic alterations. More recently, functional genomic screens using CRISPR–Cas9 approaches have shed light on the mechanistic basis of cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion7–11. However, there remains a lack of data systematically cataloguing the genetic elements of cancer cells that act in a genotype-to-phenotype fashion to facilitate cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion.

Mapping genetic determinants of CTL evasion

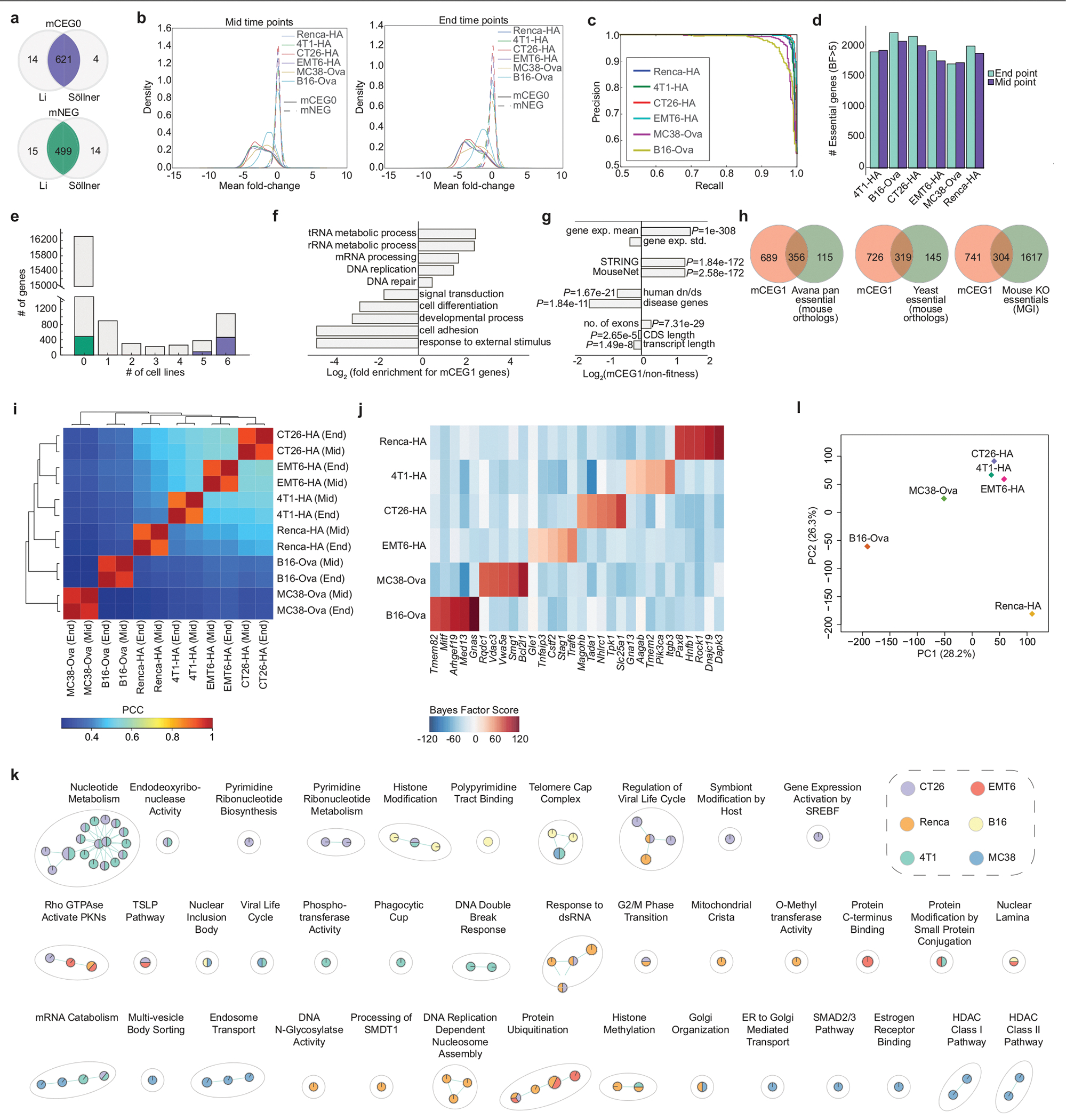

To build a platform for genome-wide phenotypic screens in mouse cancer cell lines for the systematic identification of genes associated with cancer-intrinsic immune evasion, we first constructed, using empirically defined rules12, an optimized Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (spCas9) guide RNA (gRNA) library containing 94,528 gRNAs that target 19,069 protein-coding genes. We then used this library (which we call the mouse Toronto KnockOut, or mTKO, library; Supplementary Table 1) to identify: (1) fitness genes required for the proliferation of mouse cancer cells; and (2) cancer-cell-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes. This was accomplished by performing pooled loss-of-function genetic screens across a panel of six engineered mouse cancer cell lines that express either haemagglutinin (HA) or ovalbumin (Ova) as marker antigens (Fig. 1a). For all screens, CRISPR-mutagenized cells were propagated in the presence or absence of preactivated antigen-specific CTLs to apply a selection pressure, with representative cell populations serially sampled at different time points and subjected to deep sequencing to identify gRNAs that were enriched or depleted relative to untreated cell populations (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 2; see Methods). The functional genomic diversity of our panel of cell lines, as well as the quality of the screens using the mTKO library, was confirmed by the analysis and refinement of reference essential and non-essential gene sets as previously described12–17 (Extended Data Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 3–6; see Supplementary Information).

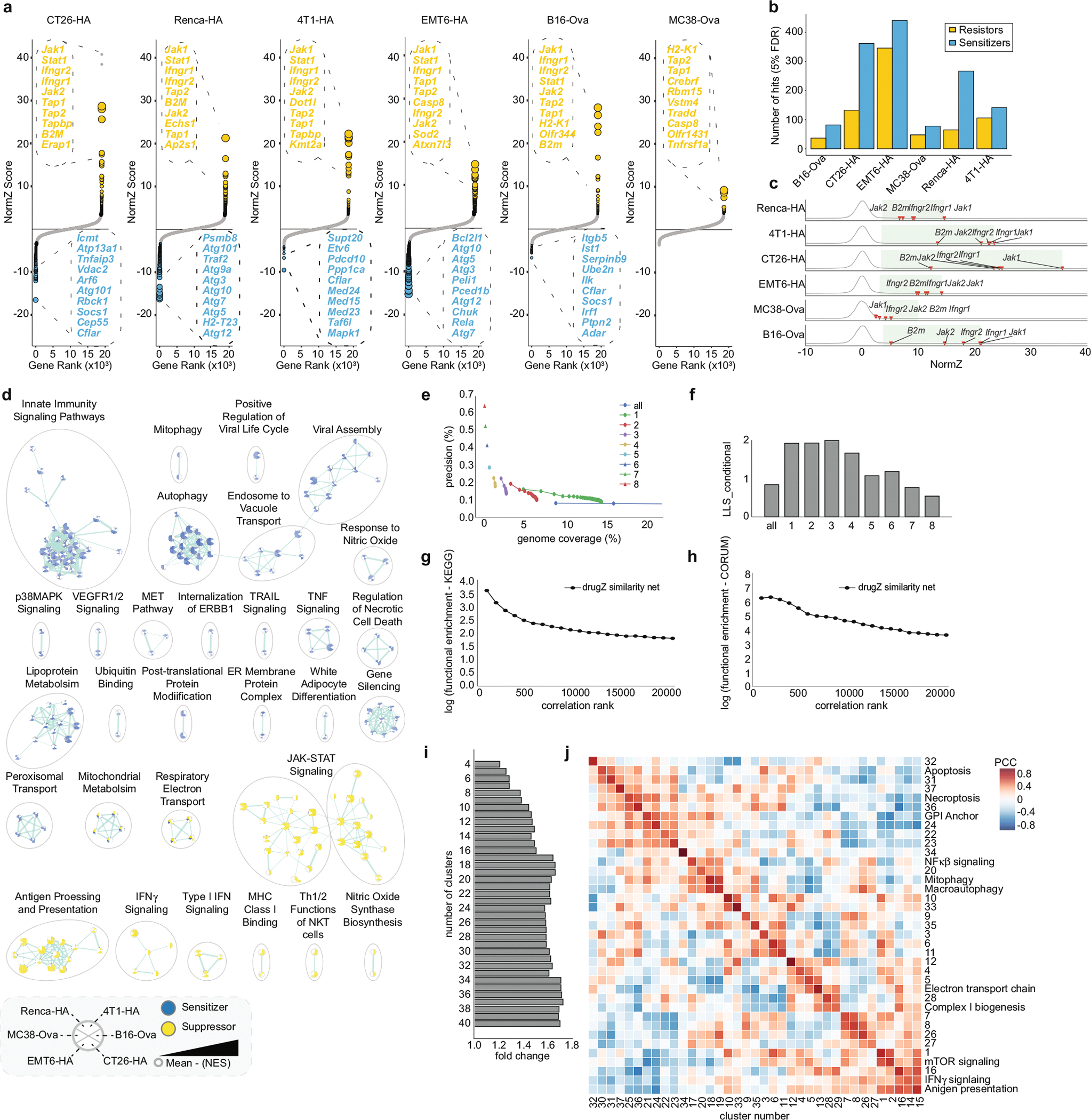

Fig. 1 |. Mapping core genes and pathways for cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion.

a, Mouse cell lines screened in this study. Renca, renal carcinoma; B16, melanoma; 4T1 and EMT6, breast carcinoma; CT26 and MC38, colorectal carcinoma. HA and Ova refer to haemagglutinin and ovalbumin antigens, respectively. Cell lines with the C57BL/6 genotype are in grey, and those with the BALB/c genotype are in black. b, Workflow for mTKO genome-scale pooled CRISPR screens to identify fitness and CTL-evaslon genes. E:T, effector-to-target cell ratio; KO, knockout. The essential gene and non-essential gene distributions are based on gene-level fold-change values, where fold change = log2(normalized read counts at early or late time points) − log2(normalized T0 read counts). c, Rank-ordered normalized z-score (NormZ score) at the mid time point for all six CTL killing screens. Hits at FDR < 5% are highlighted in yellow (resistor genes) and blue (sensitizer genes). The top ten resistor and sensitizer genes are indicated. Dot size is inversely scaled by FDR. d, Genetic co-similarity map for cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion. Representative pathways enriched in a cluster are shown on the diagonal axis (FDR < 1%). ETC, electron transport chain; PCC, Pearson correlation coefficient. e, Daisy model of gene essentiality, adapted for core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes. Each cancer cell line is represented as a petal on the flower. f, Distribution of cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes at FDR < 5% across the six cell lines. g, Pathway themes enriched in core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes (FDR < 5%). −log10(P) represents the −log10 of the adjusted P value (FDR). Mean percentage overlap refers to the mean of the percentage of overlapping core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion and pathway-definition genes across all pathways in a theme. For each theme, the mean number of query genes contained in the pathway/mean pathway term size is displayed to the right of each bar.

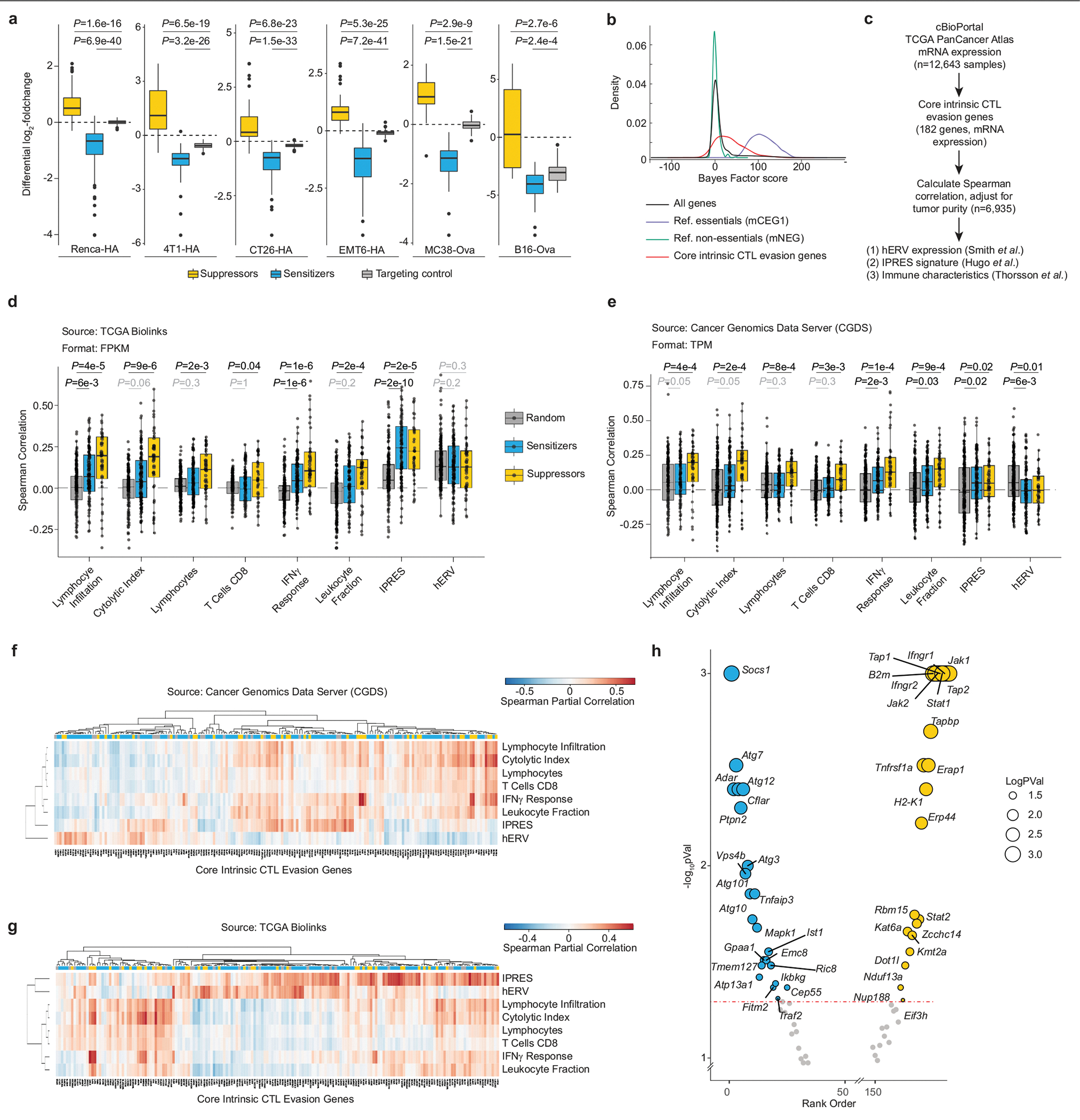

To explore the genetic landscape of cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion, we interrogated our dataset to identify genes with differential fitness effects in CTL-treated versus control populations of cancer cells using the drugZ algorithm18 (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 7). This analysis revealed that more than 2,000 genes affect cancer cell fitness under CTL killing pressure in at least one of the six cell lines, with a mean of around 330 genes per screen (Extended Data Fig. 2b; false discovery rate (FDR) < 5%). Our identified genes included well-characterized cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes that are frequently mutated in patients resistant to checkpoint immunotherapy (for example, B2m, Jak1, Jak2, Ifngr1, Ifngr2)4,6 (Extended Data Fig. 2c). To further validate our dataset, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), and observed the enrichment of well-characterized immune regulatory pathways: gRNAs that target genes involved in antigen presentation, Jak–Stat signalling and the interferon pathways mediated resistance to CTL killing, whereas those that target genes involved in necroptosis, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling and the NF-κβ pathway conferred sensitivity to CTLs4,6–11 (Extended Data Fig. 2d, Supplementary Table 8). GSEA also highlighted pathways with previously underappreciated roles in regulating the responses of cancer cells to CTL-mediated killing, including resistor genes in nitric oxide production and mitochondrial metabolism (mitochondrial translation, electron transport chain), and sensitizer genes in glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor metabolism, endosomal trafficking, transcriptional regulation and autophagy (Extended Data Fig. 2d).

To identify gene networks that regulate cancer-intrinsic immune evasion, we performed a genetic co-similarity analysis and identified gene pairs that showed correlated drugZ profiles across our six CTL killing screens, using data from two time points (mid and end) (Supplementary Table 9). Only genes that were significant in at least three measurements (FDR < 5%, resistor or sensitizer) were included, as this maximized the co-annotation of genes to the same pathway (log-likelihood score of around 2; see Methods) while maintaining sufficient genome coverage (around 2.5%) (Extended Data Fig. 2e, f). The resulting network contained a total of 548 genes (Fig. 1d). High-ranking correlated gene pairs were more than tenfold enriched for co-annotation in KEGG pathways and 50-fold enriched in CORUM complexes relative to random gene pairs, demonstrating the ability of our network to capture functional modules that affect cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion (Extended Data Fig. 2g, h). Unsupervised clustering of the matrix revealed a modular structure in keeping with this functional coherence, with gene pairs within clusters being enriched for shared pathway annotations relative to the overall network (Extended Data Fig. 2i). Notably, this allowed us to identify functional modules of pathways that are known to act in a coordinated manner to regulate immune signalling (for example, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) presentation, interferon response)—similar to what has been observed in large-scale networks of genetic interactions in model organisms19,20 (Fig. 1d, Extended Data Fig. 2j). Our network therefore provides an initial glimpse of the genetic wiring that is involved in the evasion of CTLs by cancer cells.

Core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes

The substantial genetic and functional heterogeneity of cancers means that it is essential to identify phenotypically robust genetic regulators of immune evasion for the discovery and validation of drug targets21. We therefore adapted the Daisy model of gene essentiality to identify ‘core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes’ (Fig. 1e), which we defined simply as a sensitizer or a resistor gene that was present across three or more of the six cell lines that we screened (FDR < 5%). This analysis yielded 182 genes (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Table 10) that represent the major pathways identified in our global pathway analysis described above (Fig. 1g, Extended Data Fig. 2d). To validate this set of 182 genes, we cloned a mini-library of 1,664 gRNAs that target 367 genes—including all 182 of the core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes—and performed secondary CTL killing screens across the same six cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 3a, Supplementary Tables 11, 12). Relative to a tailored list of gene-targeting control gRNAs (n = 728), our validation screens revealed robust classification of a-priori-determined sensitizer and resistor gene perturbations for each cell line (Extended Data Fig. 3a, P < 0.05, Supplementary Tables 11, 12). Only 18 core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes were also required for cell proliferation under standard growth conditions (that is, core fitness genes) (Extended Data Fig. 3b).

We next used data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to examine associations between the core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes and established markers of effective anti-tumour T cell responses4,5,22,23 (Extended Data Fig. 3c, Supplementary Table 13). Notably, compared to random gene sets, we detected significant positive correlations between the core CTL-evasion genes and IFNγ response (P = 5.05 × 10−8), leukocyte fraction (P = 5.56 × 10−6) and innate anti-PD-1 resistance (P = 1.74 × 10−3). Moreover, significant positive correlations were observed within the core CTL suppressor class for tumour lymphocyte infiltration (P = 4.16 × 10−4), cytolytic index (P = 1.73 × 10−4), lymphocytes (P = 8.37 × 10−4) and CD8+ T cell fraction (P = 2.61 × 10−3) (Extended Data Fig. 3c–g). These data further highlight the importance of our functionally defined core CTL-evasion gene set, and directly link our observations in mouse cancer models to data from patients with cancer.

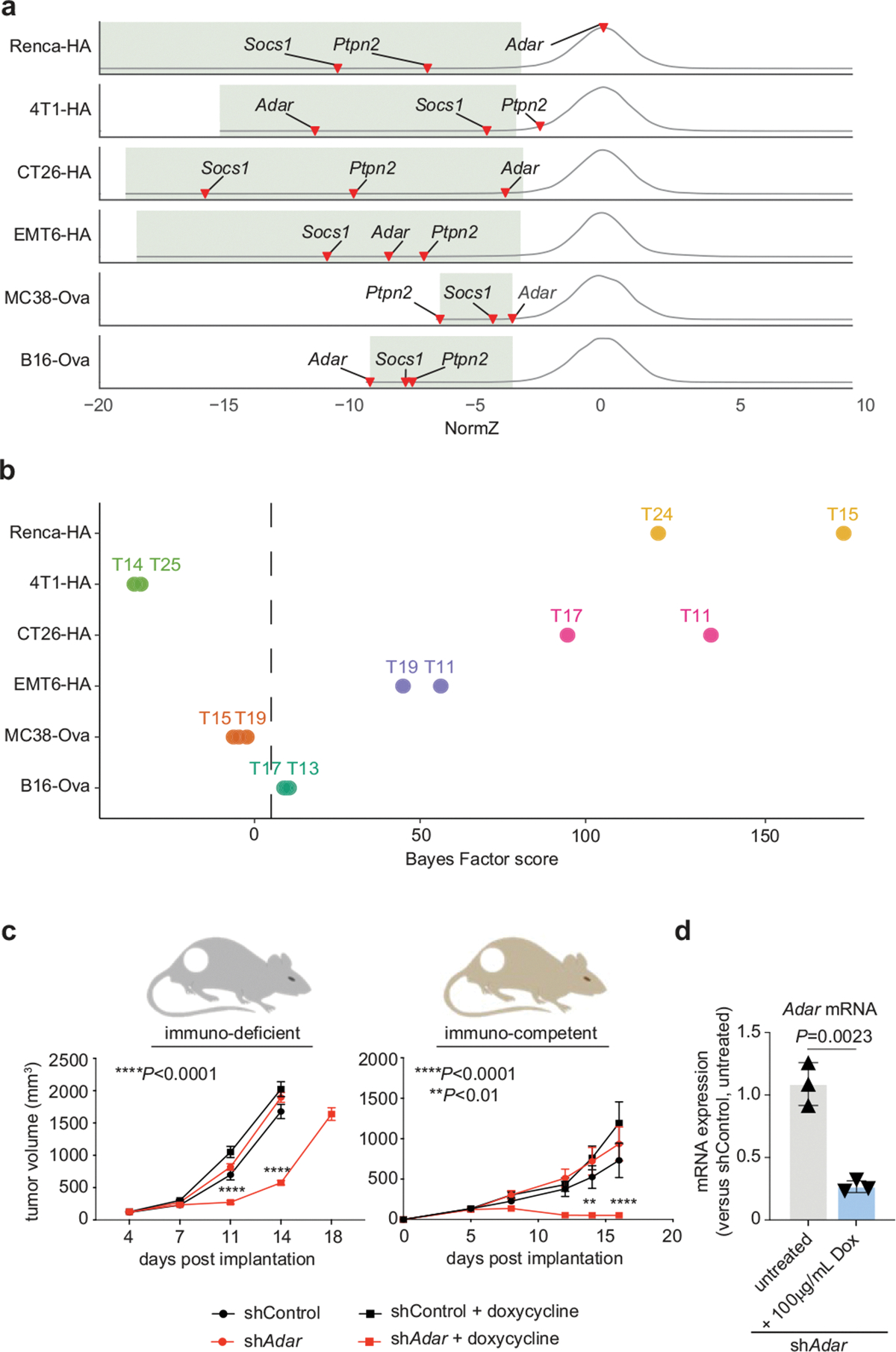

Resistance to IFNγ regulates CTL evasion

We ordered the core genes by computing the geometric mean rank across all screens, to highlight conserved hits with the strongest phenotypic effects across our dataset (Extended Data Fig. 3h, Supplementary Table 14). In addition to canonical upstream IFNγ signalling components (for example, Ifngr1 and Ifngr2, Jak1 and Jak2, Stat1 and Stat2), these hits also included three negative regulators of IFNγ signalling—Socs1, Ptpn2 and Adar24,25—that were identified as strong synthetic lethal hits with checkpoint immunotherapy in in vivo CRISPR screens performed in B16 melanoma cells8,26. Our data also show that perturbation of these genes sensitizes cancer cells to CTL killing across a range of different genetic backgrounds (Extended Data Fig. 4a). One notable exception was the loss of Adar in renal carcinoma (Renca) cells, in which Adar scored as a fitness gene (Bayes Factor (BF) score = 173; Extended Data Fig. 4b). Consistent with these observations, short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown of Adar resulted in the regression of B16 melanomas engrafted on immunocompetent mice (Extended Data Fig. 4c, d).

The observation that regulators of IFNγ signalling can broadly influence cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion motivated us to further examine the genetic determinants that dictate the sensitivity of cancer cells to this cytokine. To this end, we performed a genome-wide CRISPR screen in Renca cells propagated in the presence or absence of recombinant IFNγ, recovering both established suppressors (for example, Ifngr1 and Ifngr2, Stat1, Jak1 and Jak2) and sensitizers (for example, Socs1, Ptpn2) (Fig. 2a). Many of our core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes were prominent hits in the screen (Extended Data Fig. 5a), confirming the importance of the IFNγ response to the intrinsic CTL-evasion phenotype. These included genes annotated to the autophagy pathway (for example, Atg3, Atg5, Atg7, Atg10, Atg12 and Atg14), as well as the poorly characterized lipid-droplet-related gene Fitm2, which scored as the top hit (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 15).

Fig. 2 |. IFNγ resistance is a conserved cancer-intrinsic mechanism of CTL evasion.

a, Gene-level NormZ scores for genome-wide CRISPR screen in wild-type Renca cells propagated in the presence or absence of IFNγ (10 ng ml−1). Hits at FDR < 5% are highlighted in yellow (resistor genes) and blue (sensitizer genes), and the top ten genes are indicated for each category. Dot size is inversely scaled by FDR. b, Viability of B16–Ova cells transduced with gRNAs that target Fitm2 or intergenic control sites and treated with preactivated OT-1 T cells (CTLs) with or without anti-IFNγ blocking antibodies. Results shown are from a single experiment with three technical replicates. Data are representative of three independent biological replicates. Horizontal lines indicate the mean. P values were determined by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) comparison. P values indicated in black are significant, in contrast to those in grey, which are not significant. c, Schematic outlining genotype-to-phenotype relationship. Positive genetic interactions occur when fitness is better than expected, and are shown in yellow (masking or suppression). Negative genetic interactions occur when fitness is worse than expected, and are shown in blue (sick or synthetic lethal). d, Sectored scatter plot of gene-level quantile-normalized z-scores (qNormZ) from wild-type and Fitm2Δ cells propagated under IFNγ selection pressure. Significant negative and positive genetic interactions (FDR < 5%) are coloured blue and yellow, respectively. Dashed lines indicate median NormZ scores of genetic interactions. e, Sunbeam plot of differential gene-level Fitm2 genetic-interaction scores under IFNγ versus CTL selection pressure. Ellipse (black dashed line), 5% FDR threshold delineated by normal ellipse fit to differential scores. Principal axes (grey dashed lines), lines projecting in direction of each sector (0°, 45°, 90°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, 315°). Sector, area spanning ±22.5° of each sector principal axis: blue and yellow sectors represent consistent hits across both conditions; grey sector represents cytokine-specific effects; tan sector represents CTL-specific effects. Data point sizes are scaled by Euclidean distance from origin. f, Schematic outlining select genetic interactions with Fitm2. AtgΔ, autophagy mutants.

Fitm2 is required for normal fat storage in adipose tissue in mice27, but has not been previously associated with IFNγ signalling. We first confirmed the enhanced sensitivity of Fitm2-knockout (Fitm2Δ) cells to CTL killing with mouse Renca, mouse CT26, and human A375 cells, as well as to IFNγ sensitivity with mouse Renca and mouse B16 cells (Extended Data Fig. 5b, c). After treatment with IFNγ, Renca Fitm2Δ cells showed increased visual evidence of cell death relative to control cells (Extended Data Fig. 5d). Notably, B16-Ova cells Fitm2Δ cells displayed similar surface levels of MHC class I (MHC-I) and MHC-I-Ova peptide compared with control cells (Extended Data Fig. 5e, f). These Fitm2-related observations were specific to IFNγ, with minimal fitness effects observed after treatment of Renca Fitm2Δ cells with TNF (Extended Data Fig. 5g). Fitm2Δ-mediated sensitization to CTL killing was abrogated when cells were pretreated with anti-IFNγ blocking antibodies (Fig. 2b), which shows that Fitm2 is critical for maintaining cell survival after exposure to CTL-produced IFNγ.

To better define the genetic determinants of Fitm2-mediated CTL evasion, we mapped genetic interactions for Fitm2 under IFNγ and CTL selection pressures using genome-wide, pooled CRISPR knockout screens in co-isogenic Renca wild-type and Fitm2Δ cells in the presence of IFNγ or activated CTLs. This allowed us to systematically identify secondary genetic perturbations that render Fitm2Δ cells less sensitive (that is, positive genetic interactions: more fit or classified as masking or suppression) or more sensitive (that is, negative genetic interactions: less fit or classified as sick or synthetic lethal) to IFNγ or CTL treatment compared to parental wild-type Renca cells (that is, double-mutant interactions) (Fig. 2c). Notably, our Fitm2Δ cells exhibited a typical build-up of lipid droplet structures along the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), consistent with the known function of Fitm2 in the budding of lipid droplets (Extended Data Fig. 6a).

Genetic interactions were calculated by deriving quantile-normalized differential drugZ scores (wild type versus Fitm2Δ) for each gene (Fig. 2d, Extended Data Fig. 6b). For both CTL and IFNγ screens, and as expected for this analysis, Fitm2 itself appeared as a top positive genetic interaction. Of note, strong negative genetic interactions were identified in the IFNγ screen for genes that are involved in regulation of K63-linked protein ubiquitination, including Trim32, Stub1 and Parp10, as well as the fatty acid elongation enzyme Elovl1 (Fig. 2d). Several of these genetic interactions were also identified in the CTL screen at either the gene level (for example, Trim32, Parp10) or the pathway level (Far1) (Extended Data Fig. 6b), suggesting that Fitm2Δ cells are susceptible to oxidative proteotoxic and lipotoxic stress, which may occur during exposure to IFNγ. Consistently, whole-transcriptome analysis of Fitm2Δ cells treated with IFNγ revealed an upregulation of genes related to ER stress relative to wild-type cells, increased Xbp1 splicing and increased levels of the ER-stress-related protein BiP (Extended Data Fig. 6c–e, Supplementary Tables 16, 17, Supplementary Information). These results are consistent with a previous report in which Fitm2 was shown to be a regulator of ER membrane homeostasis that is conserved from yeast to human cells28.

The analysis of positive genetic interactions also provided insight into the genetic determinants of Fitm2-mediated sensitivity to IFNγ, with mutations in autophagy and peroxisomal genes suppressing this phenotype (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Table 18). Indeed, comparison of the rank-ordered IFNγ hits in wild-type and Fitm2Δ Renca cells revealed genetic suppression when perturbation of Fitm2 was combined with perturbation of autophagy genes. For example, Fitm2ΔAtg7Δ (FDR of around 1.36 ×10−35), Fitm2ΔAtg10Δ (FDR ≈ 3.28 ×10−31), Fitm2ΔAtg12Δ (FDR ≈ 7.28×10−30), Fitm2ΔAtg5Δ (FDR ≈ 4.69 ×10−21), Fitm2ΔAtg3Δ (FDR ≈ 2.68 × 10−17) and Fitm2ΔAtg16l1Δ (FDR ≈ 7.81 × 10−5) double mutants were particularly resistant to IFNγ-mediated cytotoxicity. This was unexpected, as perturbations in the autophagy and peroxisome pathways were among the strongest sensitizing mutations to IFNγ alone (that is, similar to Fitm2) in wild-type Renca cells. These results highlight the profound effects that genetic interactions have in the mediation of cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion, with the mutation of a single gene (Fitm2) leading to an autophagy-dependent inverse phenotype.

Autophagy–NF-κβ axis regulates CTL evasion

Notably, perturbations to autophagy only suppressed Fitm2 sensitization in the presence of IFNγ, and not in the presence of activated CTLs (Fig. 2e, f). This suggests that autophagy perturbation must have other effects that are not mediated by IFNγ—for example, effects mediated by other cytokines released by CTLs. Given the strong enrichment for TNF and NF-κβ signalling pathway genes in our overall core CTL dataset (Extended Data Fig. 7a)—as well as a significant association between these genes and autophagy in our co-similarity network (Extended Data Fig. 7b, Supplementary Table 19)—we hypothesized that autophagy has a role in mediating resistance to TNF. To test this hypothesis, we performed a genome-wide CRISPR screen in wild-type Renca cells treated with recombinant TNF. This unbiased approach supported our hypothesis, with autophagy and NF-κβ pathway genes scoring as the top sensitizing perturbations (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 20). It is noteworthy that neither Tnfrsf1a nor Tnfrsf1b emerged as resistance genes (that is, alleviating or ameliorating hits), indicating that wild-type Renca cells are not normally wired for TNF-mediated cell death, but can be sensitized through the loss of autophagy or NF-κβ signalling pathways (Supplementary Table 20). We validated these findings in independent experiments, which confirmed that Atg12Δ and Tbk1Δ cells were highly sensitized to TNF-induced cell death (Fig. 3b). Atg12Δ cells were also more sensitive to CTL killing across multiple genetic backgrounds including Renca, EMT6, MC38 (all mouse cell lines) as well as human A375 melanoma cells (Extended Data Fig. 7c–e). Pretreatment of cells with anti-TNF blocking antibodies abrogated Atg12-dependent sensitization to CTL killing, verifying the contribution of TNF-mediated death to this phenotype (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 7f).

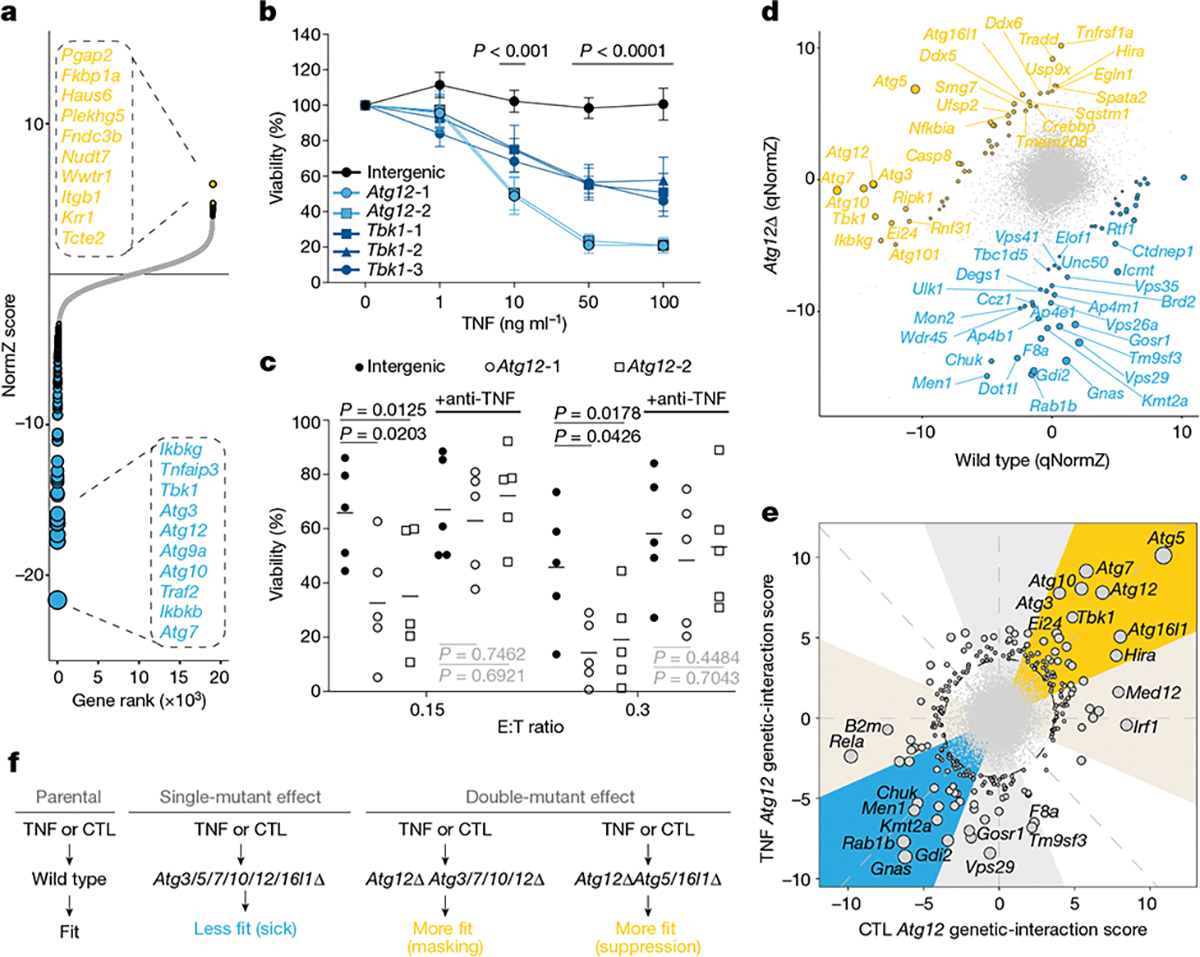

Fig. 3 |. A hub of autophagy and NF-κβ signalling mediates cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion.

a, Gene-level NormZ scores for genome-wide CRISPR screen in wild-type Renca cells propagated in the presence or absence of TNF (10 ng ml−1). Hits at FDR < 5% are highlighted in yellow (resistor genes) and blue (sensitizer genes), and the top ten genes are indicated for each category. Dot size is inversely scaled by FDR. b, Viability of Renca–HA cells transduced with gRNAs that target Atg12, Tbk1 or intergenic control sites after treatment with increasing doses of TNF. Data are mean ±s.e.m. of four (Tbk1) or 5 (intergenic, Atg12) independent experiments. P values were determined by two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD comparison. c, Viability of Renca–HA cells transduced with gRNAs that target Atg12 or intergenic control sites and treated with CTLs with or without anti-TNF blocking antibodies. Data are representative of five independent experiments. Horizontal lines indicate the mean. P values were determined by two-way ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD comparison. P values indicated in black are significant, in contrast to those in grey, which are not significant. d, Sectored scatter plot of gene-level qNormZ scores between wild-type and Atg12Δ cells propagated under TNF selection pressure. Significant negative and positive genetic interactions (FDR < 5%) are coloured blue and yellow, respectively. Dashed lines indicate median NormZ scores of genetic interactions. e, Sunbeam plot of differential gene-level Atg12 genetic-interaction scores under TNF versus CTL selection pressure. Plot features (that is, ellipse, principal axes and sectors) are as described in Fig. 2e. Data point sizes are scaled by Euclidean distance from origin. f, Schematic outlining select genetic interactions with Atg12.

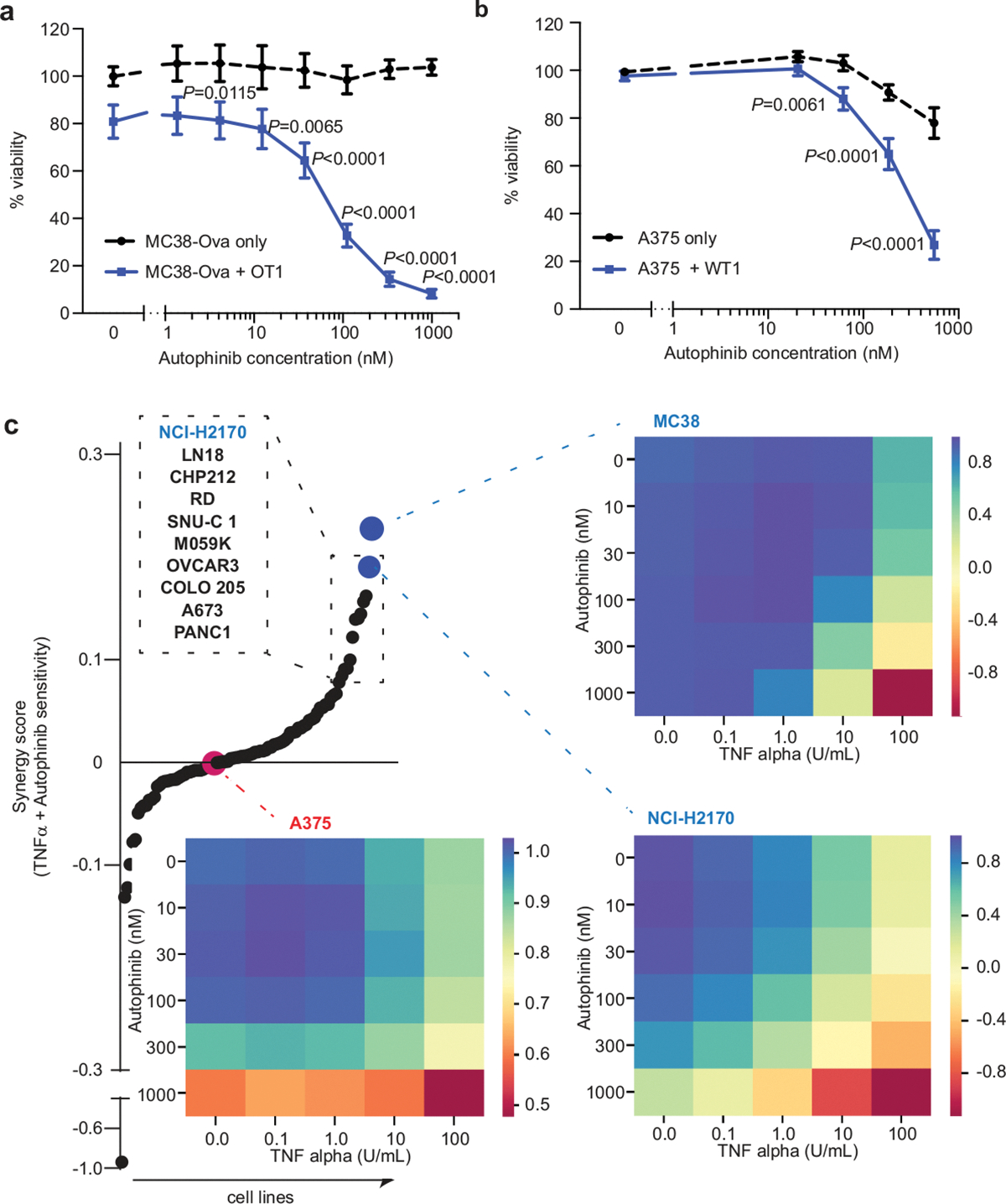

We next attempted to pharmacologically replicate our genetic results that demonstrated a role for autophagy genes in sensitivity to TNF-mediated cytotoxicity by using the VPS34 inhibitor autophinib to block autophagy29, and observed dose-dependent sensitization to CTL killing in our genetically validated mouse MC38 and human A375 cell lines (Extended Data Fig. 8a, b). To determine the generality of these findings, we conducted a drug–cytokine screen across 91 human cell lines. Forty-one cell lines showed synergistic effects (FDR < 0.05) after combinatorial treatment with autophinib and TNF (Extended Data Fig. 8c). Collectively, these results demonstrate the relevance of our findings in human cells.

To further characterize the genetic determinants of autophagy-mediated immune evasion, we mapped Atg12 genetic interactions under TNF or CTL selection pressure by performing CRISPR screens in Renca co-isogenic wild-type and Atg12Δ cells (Extended Data Fig. 9a). As expected, Atg12 itself appeared as a strong positive genetic interaction (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 9b, Supplementary Table 21). For both the TNF and the CTL screens, certain NF-κβ-associated genes emerged as either negative or positive genetic interactions. For example, downstream components of the NF-κβ pathway scored as top negative genetic interactions (Rela, Chuk), whereas upstream regulators of the pathway were more commonly positive genetic interactions (Tbk1, Ikbkg (also known as NEMO), Ei24, Rbck1, Ripk1, Sharpin) (Fig. 3d, Extended Data Fig. 9b). This demonstrates the complex relationship between the NF-κβ and autophagy pathways in orchestrating cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion, with our data suggesting that these pathways act in parallel and share upstream regulatory genes. In keeping with this, NF-κβ phosphorylation, nuclear translocation and transcriptional response remained intact when Atg12Δ cells were treated with TNF (Extended Data Fig. 9c, d, Supplementary Table 22, Supplementary Information).

Surprisingly, analysis of Atg12 genetic interactions revealed a strong inverse phenotype for several members of the autophagy family, most prominently Atg5 and Atg16l1 (Fig. 3d, e, Extended Data Fig. 9b); that is, Atg12ΔAtg5Δ and Atg12ΔAtg16l1Δ double-mutant cells were strongly resistant to the cytotoxic effects of TNF or CTLs relative to single-mutant cells (Fig. 3f). Both Atg5 and Atg16l1 have been reported to function outside of canonical macroautophagy30, and our results highlight a potential role for these non-canonical functions in immune evasion.

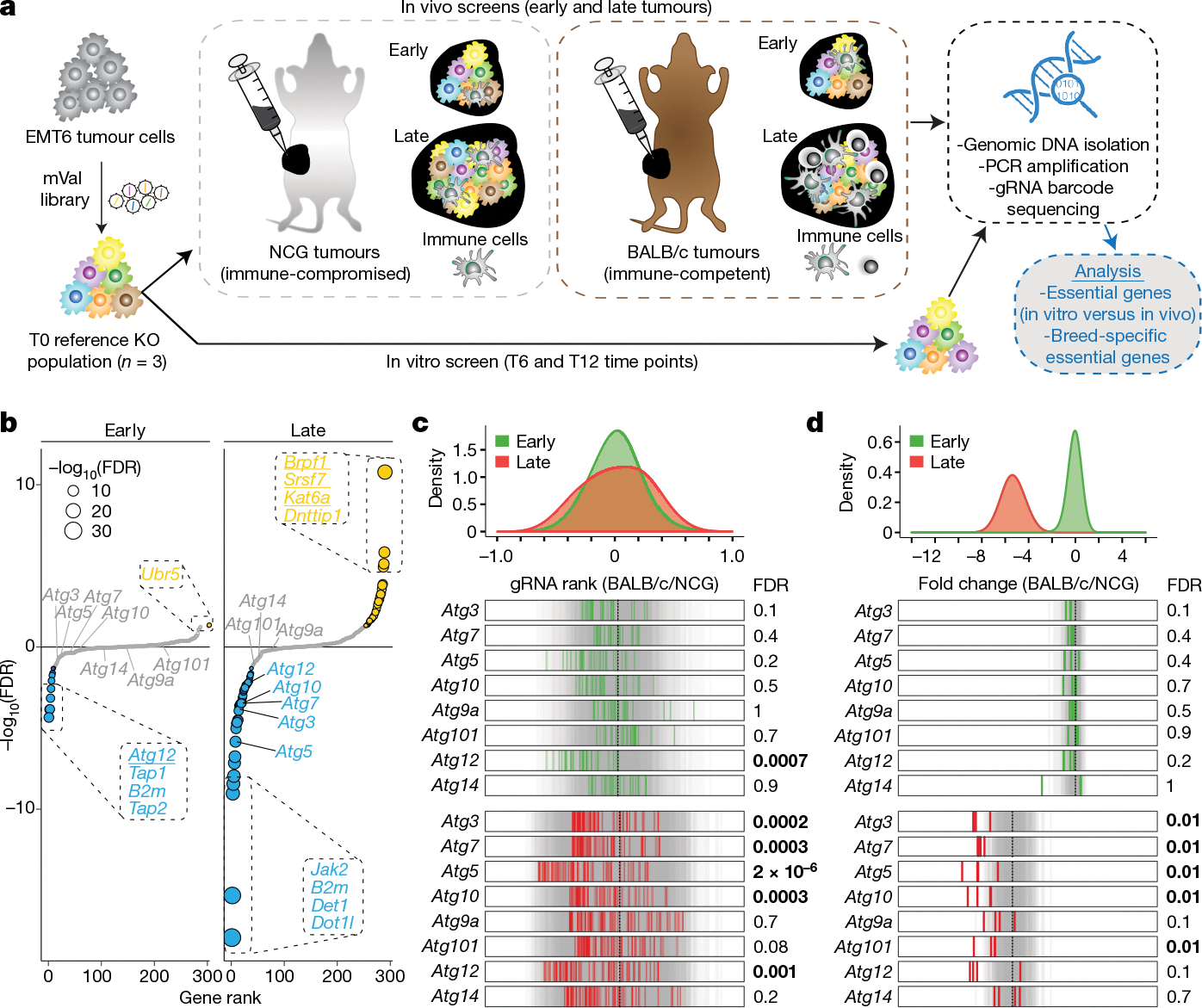

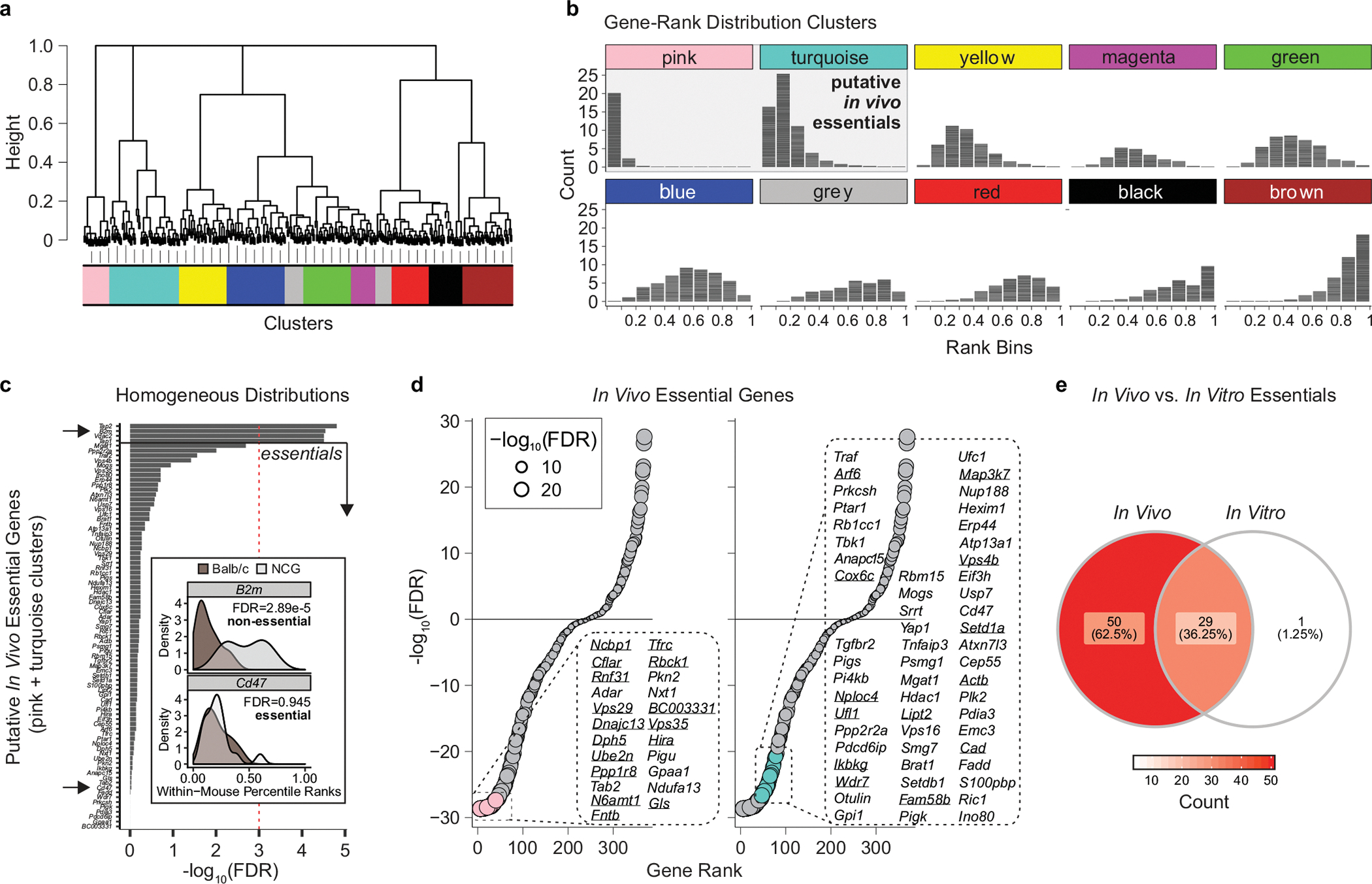

To investigate the role of cancer-intrinsic autophagy within the tumour microenvironment, we next performed an in vivo pooled CRISPR screen in the EMT6 cell model. EMT6 was chosen owing to the strong dependence of this line on autophagy in our in vitro CTL-killing screens, as well as our ability to generate Cas9-expressing tumours in immunocompetent mice. By using our mVal gRNA library targeting the 182 core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes described above, we propagated EMT6 mutagenized cells in the subcutaneous flanks of immunocompetent BALB/c or immunocompromised NCG mice, sampling tumours at early and late time points to assess the distribution of gRNA barcodes (Fig. 4a). Genes that were previously found to be essential for in vitro EMT6 proliferation were strongly depleted across all samples (Extended Data Fig. 10a–e, Supplementary Table 20), with our screen validating several core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes, including both sensitizers (Ago2, Med16, Tmem127) and suppressors (Srsf7, Brpf1, Kat6a) (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Table 23). We also observed a strong depletion of gRNAs that target autophagy genes, particularly in the late-stage tumours (Fig. 4c, d, Supplementary Table 23). Overall, these findings show that autophagy has a conserved role in mediating cancer-intrinsic immune evasion within the tumour microenvironment.

Fig. 4 |. In vivo screen validates the role of autophagy as a cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion pathway.

a, Experimental set-up for in vivo CRISPR screen. T refers to time point measured in days after the establishment of the mixed population of EMT6 knockout cells. b, Gene-level differential rank between tumours engrafted in BALB/c mice and those engrafted in NCG mice, at early and late time points. Hits at FDR < 5% are highlighted in yellow (resistor genes) and blue (sensitizer genes), markers are scaled by −log10(FDR) and genes validated from the in vitro screen are underlined. c, Tumour-level analysis showing distributions and rug plots of differential gRNA ranks for all BALB/c compared to all NCG tumours, targeting autophagy and control genes at early and late time points. The top green and red distributions represent tumour-level data at early and late time points, respectively. In the rug plots (bottom), grey lines indicate targeting control gRNAs and green and red lines represent the average gRNA rank for the indicated gene, for each tumour. Vertical dotted black lines represent the median of control gRNAs. Statistical significance between the autophagy and control genes was determined by two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test with Benjamini–Hochberg correction (FDR). d, gRNA-level analysis showing distributions and rug plots. Top graphs show differential fold change (FC) distributions for early and late tumour time points in different mouse genetic backgrounds (mean(FCBALB/c) − mean(FCNCG)), where FCBALB/c = log2(BALB/c read counts at early or late time points) − log2(BALB/c T6-normalized T0 read counts) and FCNCG = log2(NCG read counts at early or late time points) − log2(NCG T6-normalized T0 read counts). The rug plots show differential fold change for individual gRNAs that target autophagy and control genes between tumours engrafted in BALB/c mice and those engrafted in NCG mice, at early and late time points. The grey lines indicate targeting control gRNAs. Vertical dotted black lines represent the mean of control gRNAs. Statistical significance between the autophagy and control genes was determined by one-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Holm’s multiple testing correction (FDR). FDR values equal to or below 0.01 are indicated in bold.

Discussion

To explore the functional genomic landscape of cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion, we developed and applied optimized loss-of-function CRISPR–Cas9 genetic screening methods on a genome scale to identify regulators of the response of cancer cells to CTL-mediated killing. By performing screens across our panel of functionally and genetically diverse cell lines, we identified a core conserved set of genes and pathways that broadly mediate cancer-intrinsic CTL evasion. Our study provides a reference set of core CTL-evasion genes and pathways that may inform efforts to develop cancer immunotherapy strategies.

Similar to ongoing large-scale functional genomic efforts to map the dependencies of cancer cell lines, our data reveal the utility of systematically dissecting the complex genetic landscape of cancer-intrinsic immune evasion using a combination of in vitro and in vivo approaches. In particular, we highlight the critical importance of understanding how genetic interactions combine to alter the CTL-evasion phenotype, with pathways such as autophagy exemplifying how strong pleiotropic effects may complicate the application of approaches that target a single gene to cancer immunotherapy.

Methods

Plasmids

Lenti-HA-RFP was generated by PCR amplification of the Puerto Rico influenza A strain 8 haemagglutinin sequence (a gift from T. Griffith) followed by ligation into the lentiCas9-EGFP (Addgene 63592) backbone by restriction enzyme digestion to remove the Cas9 open reading frame and Gibson assembly. Monomeric RFP (mRFP) was subsequently inserted and replaced EGFP by restriction enzyme digestion and Gibson assembly. Lenti-OVA was generated internally, with the OVA sequence31 cloned into a pLVX-EF1a-IRES-neo backbone and Flag-tagged in the N terminus (pLVX-EF1a-IRES-neo: OVA, Flag N-term). Lenti-Cas9–2A-Blast plasmid (Addgene 73310) was used to make Cas9 stably expressing cell lines. The lentiviral firefly luciferase construct (PGK-GFP-IRES-LUCIFERASE) was used to make cell lines that stably express luciferase. The modified lentiCRISPRv2 (ref. 12) and pLCKO2 plasmids32 (Addgene 125518) were used for expression of individual gRNAs in native or Cas9-expressing cell lines, respectively.

Cell lines

A complete list of cell lines, including the 91 used in the autophinib screen, can be found in the Supplementary Information. Commonly used lines include Renca, CT26, B16, MC38, HEK293T, 4T1 and EMT6, and were originally purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The 4T1 and EMT6 cell lines were gifts from W. Chan and D. Morris, respectively. These lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Life Science Technologies). Cells were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Cell lines were authenticated using whole-transcriptomic analysis. No short tandem repeat (STR) analyses were performed on the above cell lines. Mycoplasma testing was routinely performed. U-118 MG (contained in the 91-cell-line panel for the autophinib screen) is the only cell line used in this study that appears on the commonly misidentified list. This line was purchased from ATCC and verified by STR analysis.

HA-expressing cell lines were generated in the Renca, CT26, 4T1 and EMT6 backgrounds via transduction with lenti-HA-RFP. Successfully transduced cells were selected via flow cytometry and subjected to limiting dilution and single-cell clonal expansion. Ova-expressing cell lines were generated in the B16 and MC38 backgrounds via transduction with lenti-Ova followed by flow cytometry to obtain an Ovahi polyclonal population. HA- and Ova-expressing cell lines were periodically re-sorted by flow cytometry to maintain cells with high expression levels. In addition, for validation experiments, B16F10–Ova and MC38–Ova cell lines were engineered to stably express TdTomato (pLVX-EF1a-IRES-hyg-tdTomato), whereas Renca–HA, CT26–HA, 4T1–HA and EMT6–HA were engineered to stably express firefly luciferase (PGK-GFP-IRES-LUCIFERASE). All lines were sorted for high expression.

Knockout cell lines were generated by electroporation using the Neon Transfection System (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, high-quality modified LCV2 or pLCKO plasmids targeting a gene of interest were prepared using the PureLink Plasmid Midiprep/Maxiprep Kit (Invitrogen), and electroporated into Renca or Renca-HACas9+, respectively. Twenty-four hours after electroporation cells were puromycin-selected for 72 h. Selected cells were then subjected to limiting dilution and single-cell clonal expansion. Genomic DNA from selected clones was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (Qiagen) and gRNA target regions were PCR-amplified and analysed by Sanger sequencing. Confirmation of gene knockout was performed using TIDE (https://tide.nki.nl/) to identify out-of-frame insertion-and-deletion mutations. CRISPR-mediated gene knockouts were also verified by manual inspection of the aligned RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) reads at the gRNA target sites in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV), when RNA-seq data were available (for example, Renca Fitm2Δ and Atg12Δ knockout cells).

Animals

The use of animals in this study followed the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care, Ontario’s Animals for Research Act, The Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Cambridge Public Health Laboratory Animal Ordinances and the USDA’s Animal Welfare Act. The study was approved by the University Animal Care Committee at the University of Toronto and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Agios Pharmaceuticals. At the University of Toronto, mice were housed at approximately 22 ± 2 °C, humidity 45% on a 14-h light, 10-h dark cycle. At Agios, mice were housed at approximately 21 ± 3 °C, 30–70% humidity on a 12-h light/dark cycle. Two–to-twelve-month-old female or male Clone 4 (CL4) (CBy.Cg-Thy1aTg(TcraCl4,TcrbCl4)1Shrm/ShrmJ, stock no. 005307) and 3–6-month-old female OT-1 (C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J, stock no. 003831) T cell receptor transgenic mice were used, being purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (www.jax.org) with a breeding colony maintained. CL4 genotyping was performed according to The Jackson Laboratory protocols. Eight-to-twelve-week-old female C57BL/6j and NSG mice were purchased and used from The Jackson Laboratory and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Agios animal care facility. Eight-to-sixteen-week-old female NCG (NOD-Prkdcem26Cd52Il2rgem26Cd22/NjuCrl, strain no. 572) and BALB-c mice were used and purchased from Charles River Laboratory.

Quantitative PCR analyses

RNA was extracted using the Qiagen RNeasy Plus Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (74136, Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized by converting extracted RNA using the RNA to cDNA EcoDry Premix (Oligo dT) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (629543, Takara). Relative gene expression levels were monitored using the following Taqman assays from Applied Biosystems: ADAR1 (Mm00508001_m1) and PPIA (Mm02342430_g1) using Advanced Fast Master Mix (4444557, Applied Biosystems). CT values were normalized to PPIA as the endogenous control.

mTKO and validation library construction

All 94,528 gRNA sequences for the mTKO library were designed in an analogous manner to the human TKOv3 library and cloned into the pLCKO2 vector as previously described12. The cloned plasmid pool yielded a 2,300-fold representation of the library.

For the validation library (also referred to as mVal), gRNAs targeting the 182 core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes were selected from the mTKO library. The top four best-performing gRNAs displaying the most significant depletion (sensitizers) or enrichment (suppressors) in fold change between CTL-treated versus untreated populations across the genome-wide screens were selected for each gene. An additional 728 control gRNAs were included in the library targeting 182 genes (4 gRNAs per gene) that displayed no significant proliferation (Bayes Factor (BF) score, see ‘Data processing for pooled CRISPR screens’) or immune-evasion (NormZ, see ‘Analysis of cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes’) fitness profile and were expressed across all cell lines. Cloning of the mVal library was performed in an analogous manner to the mTKO library, as described above. Oligos were obtained from Agilent and the library was cloned at 233-fold representation.

In vitro genome-wide and mini-validation CRISPR screens

Cas9-expressing cells were infected with the mTKO lentiviral library at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of around 0.5. Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were selected with puromycin for 48–96 h. Selected cells were divided into a control and an experimental group with three replicates each and maintained at around a 200-fold library coverage throughout the screens. For T cell killing screens, the experimental groups were treated with preactivated CL4 or OT-1 CD8+ T cells to achieve approximately 50% or higher cytotoxicity (determined by microscopic evaluation), with control groups being treated with wild-type CD8+ T cells (B16–Ova, MC38–Ova) or left untreated (Renca– HA, EMT6–HA, 4T1–HA, CT26–HA). For cytokine screens, the experimental groups were treated with recombinant TNF (10 ng/ml) or IFNγ (10 ng ml) to achieve approximately 50% or higher cytotoxicity (determined by microscopic evaluation). Treatments were repeated 2–3 times throughout the course of each screen. Screens in isogenic mutant lines were performed in an analogous fashion, as above. At each passage, cell pellets were collected at around a 200-fold library coverage for genomic DNA extraction, starting at day 0 after selection. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. gRNAs were amplified as described previously32. The resulting libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2500. For each screen, we sequenced a mid and end time point (except Fitm2 CTL-treated screen), defined as the population of cells following 1–2 and 2–3 treatment rounds, respectively.

CTL killing validation screens were performed across our cell line panel using the mVal library in an analogous fashion to that described above but at more than 500× representation.

Data processing for pooled CRISPR screens

For each sample, reads were preprocessed by locating the first 8 bp of one of the three anchors used in the barcoding primers (U6, tracr or pLCKO tracr), and extracting the 20 bp preceding the anchor using a bespoke Perl script. We allowed up to two mismatches during the anchor search. The untrimmed reads were retained for quality control; the median ratio of reads with unmatched anchors was 1.0% for the genome-wide library, and 5.3% for the validation library. After trimming, a quality control alignment was performed using Bowtie v. 0.12.8 (allowing for a maximum of two mismatches, ignoring qualities). On average, 89.7% of the trimmed reads aligned for the mouse TKO screens, and 95.4% of the reads aligned for the validation screens.

For each sample, all available reads were combined from different sequencing runs if applicable and aligned using Bowtie as described above, and gRNAs were tallied. Read counts for all samples in a screen were combined in a matrix and normalized to 10 million reads per sample by dividing each read count by the sum of all read counts in the sample and then multiplying by 10 million. Fold change is calculated against a reference sample (usually T0). Bayes Factor (BF) scores were calculated as previously described12,14,15.

Analysis of cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes

To measure the effect of gene knockout on cancer cell fitness during treatment with CTLs, we compared paired screens of cell lines cultured with and without CTLs using the drugZ version 1.0 pipeline (Python v.3.7.1) for two different time points (mid, end)33. An FDR threshold of 5% for sensitizer and resistor genes was used.

For cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes, we identified and visualized significantly enriched pathways for each screen using GSEA (GSEA v3.0)34. GSEA was performed using a preranked gene list sorted on the basis of mid-time point drugZ scores as input. The pathway database was obtained from the laboratory of G.B. (http://download.baderlab.org/EM_Genesets/), and comprised pathways from Reactome, NCI Pathway Interaction Database, Gene Ontology (GO) Biological Processes (BP), HumanCyc, MSigDB, Netpath and Panther35. GO terms inferred from electronic annotations were excluded. Only pathways with between 8 and 200 genes were included. Enrichments were visualized using Cytoscape (v.3.7.1) with the Enrichment Map plug-in (v.3.5.1), in which nodes represent pathways and edges connect pathways with overlapping genes. Nodes are connected by an edge if they share gene set similarity ≥ 0.375. Clusters of related nodes were circled using the AutoAnnotate plug-in v.1.3 in Cytoscape and given a general pathway label. Pathways are shown if they were enriched in at least three or more screens at an FDR of <5% (blue, sensitizer; yellow, suppressor).

Core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes were identified as those that were hits in at least three cell lines (FDR < 5%). Pathway enrichment for these genes was performed using g:Profiler (accessed around 3 October 2018). Reactome and GO:BP pathways with between 3 and 200 genes were included. Enriched pathways were visualized using Cytoscape, and the AutoAnnotate plug-in (v.1.3) was used to find pathway themes. A pathway similarity of 0.3 was used to connect related nodes. For each pathway in each theme, the percentage overlap (that is, percentage of core killing genes found in that pathway) was computed as: overlap size/gene set size. The mean percentage overlap was computed over all pathways in the theme, and the P value was set to be the minimum P value over all pathways in the theme. The bar plot displays the mean percentage overlap for each theme and is ordered and coloured according to the maximum −log10(P value).

Rank order of core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes

The rank product was calculated by multiplying the rank of a given gene across each of the six screens and raising the product to the power of multiplicative inverse of the number of screens (that is, 1/6):

To calculate P values, 1,000 random sets of 182 rows by 6 columns were generated. Each column in each set contained values between 1 and 182. The rank product was calculated for each of the sets and combined into a large matrix of 182 rows by 1,000 columns of random rank products. In parallel, the screen rank products were converted into a large matrix of the same dimensions as the random sets by replicating the rank products for the 182 genes 1,000 times (resulting again in 182 rows by 1,000 columns with the same rank product per column). P values were then calculated by subtracting the screen data matrix (182 rows × 1,000 columns) from the random set matrix (182 rows × 1,000 columns) element-wise, then summing the resulting differences across every row and dividing by 1,000.

Co-similarity analysis

NormZ profiles for all six cell lines at mid and end time points were obtained using drugZ as described above, resulting in a total of 12 data points for each gene. We subsequently calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients (PCCs) between all possible gene pair combinations across the 12 data points. To reduce the number of associations between genes lacking phenotypes in our screen, we filtered the resultant matrix of PCCs to include only genes with three or more significant drugZ scores at an FDR of 5%. This threshold was determined using a benchmarking analysis that used a log-likelihood score (LLS) to quantify functional enrichment in the highly correlated gene pairs across various data point thresholds (number of data points required, Ndp), as previously described36.

In brief, the LLS is represented by the following formula:

in which E represents the top-ranked gene pairs by PCC (for example, top 1,000 gene pairs above threshold Ndp), P(L|E) represents the frequency of gene pairs in the filtered matrix belonging to the same functional pathway using the Bader laboratory pathway database (‘co-annotated’), andP( ¬ L|E) represents gene pairs that are present in the pathway but not co-annotated. Therefore, P(L|E)/P(¬L|E) represents the odds ratio (OR) for gene pair co-annotation at the given threshold. In the denominator, P(L) represents the frequency of all co-annotated gene pairs in the unfiltered matrix, P(¬L) represents the frequency of pairs lacking co-annotation, and P(L)/P(¬L) measures the OR of functional enrichment in the unfiltered matrix, or the background OR. Taking the log of the two OR values produces a LLS for functional enrichment in the filtered gene pairs at the given threshold, Ndp.

To account for extreme filtering effects that may artificially inflate the score, we adjusted the LLS with a filtering parameter and termed this the conditional LLS. To achieve this, we separated the LLS into two components: a conditional LLS that represents functional enrichment (that is, LLS) after controlling for the filtering effect, and a significance-based filtering effect. This is represented by the following formula:

Here, we multiplied the previously introduced LLS formula by P(L|F)/P( ¬L|F), which represents the OR of functional enrichment in the gene list filtered by the data point threshold. Consequently, the right term (that is, filtering effect) captures the functional bias of filtering genes using a specific data point threshold, whereas the left term explains the network predictive power (that is, LLS) after removing this filtering bias.

To establish a threshold Ndp, we calculated the conditional LLS of the first 1,000 gene pairs, ordered from highest to lowest PCC, for all data point thresholds. We also calculated the percentage genome coverage after filtering, defined as the number of genes in the dataset after filtering over the total number of genes in the mouse genome, to determine the optimal threshold that maintains both high conditional LLS and genome coverage. A threshold of three data points best fulfilled these criteria, resulting in a final matrix of 548 genes. To determine the functional prediction performance of this matrix, we quantified the LLS using independent annotations defined by the KEGG and CORUM protein complex databases for all pairwise gene combinations amongst these 548 genes37,38.

Next, we plotted a co-similarity matrix, consisting of PCC values between the 548 genes, and arranged by hierarchical clustering using Euclidian distance and average linkage methods. To select the optimal number of clusters, we evaluated the functional enrichment of various numbers of clusters by measuring the enrichment ratio of gene pairs within clusters versus random probability.

The enrichment ratio was defined as: (positive interactions/number of gene pairs within a cluster)/(positive interactions across genome/number of gene pairs across genome).

To define positive interactions, we only considered pathway terms (that is, gene sets) containing fewer than 50 genes to avoid inclusion of overly general pathways. Dividing into 37 clusters provided the strongest functional enrichment. To identify functional terms that best describe each cluster, we calculated Benjamini–Hochberg-corrected P values for functional enrichment with GO-BP terms using Fisher’s exact test. A representative pathway term enriched at an FDR of < 1% was chosen to label each cluster. For clusters without any significant enrichment, the cluster ID number was displayed. A cluster–cluster interaction diagram was then generated using the mean PCC of pairwise interactions between genes in cluster pairs.

A subnetwork for autophagy genes and their interactors in the co-similarity network was visualized using Cytoscape. Nodes represent genes annotated to the autophagy pathway (GO:0006914) and their interactors. Interactors connected to at least two autophagy genes were shown in the network.

Genetic interaction analysis

Genetic interactions for Atg12 and Fitm2 under cytokine or CTL selection pressures were calculated by computing quantile-normalized differential NormZ scores between mutant versus wild-type cells. Quantile normalization was conducted for each treatment set separately by including data from all screens under a given selection pressure; for CTLs (wild type; Fitm2; Atg12); TNF (wild type; Atg12); and IFNγ (wild type; Fitm2).

The difference (D) between wild-type gene effect (normZWT) and mutant gene effect (normZKO) was calculated for all mTKO targeted genes and converted to a z-score as shown below:

A negative score reflects that perturbation of the gene results in a reduced fitness in the context of the mutant background, whereas a positive score reflects improved fitness. Finally, we calculated P values corresponding to the z-score, and convert to FDR by Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

RNA-seq

To obtain RNA for sequencing, 0.5–1 × 106 cells transduced with lentivirus bearing gRNAs targeting Atg12, Fitm2 or intergenic control regions were seeded onto 6-well or 10-cm plates and cultured in complete medium until confluent. As indicated, clonal Atg12Δ and Fitm2Δ cells were also used. For baseline cell line expression analysis, cells were cultured for 48 h in duplicates. For Atg12Δ and Fitm2Δ studies, experiments were done in triplicate and cells were challenged with TNF (10 ng/ml) for 12 h or IFNγ (10 ng/ml) for 48 h, with cytokine-free medium serving as control. For all experiments, RNA was extracted from cultured cells using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, cells were lysed on ice in RTL plus buffer (Qiagen) and passed through QIAshredder columns. Supernatant was then transferred to RNeasy spin columns and an on-column DNase treatment was performed using the RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen).

RNA-seq data processing

Libraries were sequenced with single-end 76-bp reads on a NextSeq500 (baseline expression analysis) or paired-end 2 × 100-bp reads on an Illumina NovaSeq6000 (Atg12-mutant and Fitm2-mutant studies) sequencer using an S2 flowcell. Samples were mixed to obtain an average of 25 million single-end or 35 million paired-end clusters that passed filtering. Reads shorter than 36 bp on either read 1 or read 2 were removed before mapping. Reads were aligned to reference genome mm10 and Gencode vM12 gene models using the STAR short-read aligner (v.2.6.1b)39. For samples run on the NextSeq500, an average of 82.5% of filtered reads mapped uniquely (min 81.5%, max 83.8%), and an average of 90.8% of the filtered NovaSeq reads mapped uniquely (min 86.3%, max 93.1%). The gene-level read counts from each sample, computed by STAR, were merged into a single matrix using R. Finally, cufflinks (v.2.2.1) was used to generate a matrix of FPKM values for all samples using default parameters. The raw and processed data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database.

RNA-seq analysis

For Atg12 and Fitm2 knockout experiments, differentially expressed genes were identified using the Bioconductor packages limma (v.3.32.10) and edgeR (v.3.24.3). The read count matrix was filtered using the filterByExpr() function using default parameters. Principal component analysis was performed to examine the main treatment effects, and to exclude the presence of confounding batch effects, using the base R function prcomp(). Samples were normalized using calcNormFactors(method = “TMM”) from edgeR and transformed to log2 using the voom function in limma. Next, a design matrix was specified to fit coefficients for the CRISPR knockouts, presence or absence of cytokine, and an interaction term to examine differences in the cytokine effect in the mutant backgrounds. Differentially expressed genes were extracted using the topTable function in limma with absolute log2(fold change) > 0.58 (where fold change = log2(KO or WT read counts ± cytokine) − log2(WT read counts)) and adjusted P value < 0.05. Volcano plots were generated for visualization, with genes displaying an absolute fold change > 0.4 and a P value <10−6 being highlighted. Pathway analysis was performed on differentially expressed genes using these thresholds with g:Profiler, as described above.

To quantify the relative expression of the short and long splice forms of Xbp1, the base-level depth of sequence reads through exon 4 (chr11:5524239–5524384) of Xbp1 was extracted from the aligned BAM files using samtools depth. The short splice form is characterized by splicing out 26 base pairs between chr11:5524277–5524304. Thus, the ratio of short to long form is computed as: ratio = 1 − mean.26bp/(mean(upstream, downstream)). Differences in mean ratios between conditions were assessed using a Student’s t-test.

Isolation and activation of CD8+ T cells

Naive CL4 or OT-1 CD8+ T cells were magnetically separated from freshly extracted CL4 mouse spleens using an antibody magnetic separation kit (130–096-543, Miltenyi or 19853, StemCell). Immediately following isolation, T cells were activated and expanded with CD3/CD28 beads according to the manufacturer’s protocol (130–093-627, Miltenyi or 11453D, Gibco). Activated CD8+ T cells were cultured for 4–6 days before use in all experiments.

In vitro T cell cytotoxicity assay

HA- or Ova-expressing Cas9+ cancer cell lines were transduced with lentivirus bearing gRNAs targeting genes of interest or intergenic control regions. Transduced cells were selected with puromycin for around 72 h and seeded into 24- (25,000–50,000 cells per well) or 96- (1,500–5,000 cells per well) well plates in duplicates or triplicates. Following overnight incubation, cells were treated with preactivated CL4 or OT-1 CD8+ T cells at increasing effector-to-target ratios for around 48 h.

At the end point, CD8+ T cells and dead cancer cells were removed by gentle PBS wash, with cancer cell viability assessed by counting the remaining adherent cells in each well on a Coulter counter (24-well plates), via bioluminescence using a microtitre plate reader (96-well plate) or using CellTiter-Glo (CTG) reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (G7570, Promega). For selected experiments, cancer cell viability was also monitored by live-cell fluorescent microscopy using the IncuCyte. In all cases, cell viability relative to untreated control cells is shown.

For selected experiments, cancer cells were preincubated for 30 min with 100 μg/ml anti-TNF (MP6-XT22, Biolegend 506331) or anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2, Biolegend 505834) antibodies before addition of T cells to neutralize these cytokines during co-culture.

Cytokine dose-response assay

Cancer cells were transduced and seeded in 96-well plates as per the in vitro T cell cytotoxicity assay. Twenty-four hours after seeding, cells were treated with increasing doses of recombinant TNF (1–100 ng/ml) or IFNγ [1–100 ng/ml) for 72 h. Cell viability was measured via bioluminescence using a microtitre plate reader or by live-cell fluorescent microscopy using the IncuCyte for selected experiments. In all cases, cell viability relative to untreated controls cells is shown.

In vitro studies in human cancer cell lines

A375 (ATCC, CRL-1619) knockout cell lines were generated by electroporating Cas9 guide-conjugated RNPs as per a previous study40 using the 4D-Nucleofector system (Lonza) and Lonza optimized protocol for A375 cells. In brief, RNPs were produced by incubating 2 sgRNAs with Cas9 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A36499) at a final 3:1 molar ratio, and electroporated into A375 cells using the SF cell line solution (Lonza, VAXC-2032) with the FF-120 program. Each electroporation well contains 2 × 105 cells, 180 pmol Cas9 and 540 pmol sgRNA (2 guides combined per electroporation targeting either intergenic regions or the human gene of interest as follows sgIntergenic-1 and 2: GGGGCC ACTAGGGACAGGAT; GTCACCAATCCTGTCCCTAG, sgAtg12–1 and 2: CTCCCCAGAAACAACCACCC; CCTCCAGCAGCAATTGAAGT, sgFitm2–1 and 2: GAGGTAGCTCTCGGGCAACG; CGGGGTGCACTCACACGTTG). Twenty-four hours after electroporation cells were assessed for knockout by western and/or quantitative (q)PCR and used in the final assays within five passages from electroporation.

Human co-culture was performed by culturing A375 cells with anti-WT1 T cells (Astarte Biologicals, 1089–4040SE18) in the presence of 2 ng/ml of human recombinant IL-2 and increasing concentrations of autophinib (0–1,000 nM) for 60 h at an E:T ratio of 10:1. Similarly to mouse co-culture studies, CD8+ T cells and dead cancer cells were removed by gentle PBS wash and remaining viable cells were assessed using CTG reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, G7570).

A panel of 91 human cancer cell lines were seeded in 96-well plates in the recommended medium for each cell line and at densities optimized for each cell line and ranging from 2,000 to 6,000 cells per well. Twenty-four hours after seeding, cells were treated with human recombinant TNF (Invitrogen,10602HNAE50) ranging from 0 to 100 U/ml and/or autophinib (Tocris Bioscience, 63–245-0) ranging from 0–1,000 nM for a total of 72 h. Cell viability was then assessed using CTG reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, G7570) at T = 0 and at the end of the experiment, T = 72 h.

Growth rates (μ) were calculated using the following formula: μ = LN(Tend-blank)/(T0-blank)]/time (h). μ/μmax calculations were used to compare growth rates of drug-treated to vehicle-treated cells, where maximum growth is observed in vehicle (DMSO)-treated cells.

Synergy scores between TNF and autophinib were computed using the following model:

in which μ(cA,cT) is the growth rate of cells treated with concentrations cA and cT for autophinib and TNF, respectively. The residual, sAT, captures the effect of both treatments at concentrations cA and cT. The average synergy was computed across all concentrations of autophinib and TNF, in which M is the total number of conditions:

Live-cell imaging

For select cytokine sensitivity assays, TdTomato-expressing cancer cells were plated in clear-bottom 96-well plates (3904, Corning) at optimized densities, treated with increasing concentrations of IFNγ (78021.2, StemCell) or ΤNF (315–01A, Peprotech) and imaged every 2 h for at least 72 h (IncucyteS3 or Zoom, Essen Bioscience). The images were analysed using IncuCyte software (IncuCyte S3 v.2018A or Zoom v.2016A, Essen Biosciences) and the confluency of the red fluorescent cells was calculated.

Western blot analyses

For experiments assessing protein levels of NF-κβ, NRF2 and autophagy proteins, wild-type versus clonal Atg12Δ or Atg7Δ isogeneic Renca–HA cells were used. As indicated, polyclonal knockout populations were also used by transducing Renca cells with intergenic versus Atg12 gRNAs. A total of 1.5 × 106 cells were seeded into 10-cm plates and cultured for 48 h, followed by treatment with TNF (100 ng/ml) for 30 min. Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein fractions were generated using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction kit as per the manufacturer’s protocol, with around 6 million cells per 10-cm plate to generate 1 μg/μl protein lysates. Protein quantification was done by Pierce BCA Assay (23225, Life Technologies).

For experiments assessing BiP protein levels, wild-type versus clonal Fitm2Δ isogenic Renca cells were used. A total of 0.5 × 106 cells were seeded into 10-cm plates and cultured for 24 h, followed by treatment with increasing doses of tunicamycin (Abcam, ab120296) or IFNγ (100 ng/ml) for 24 or 72 h, respectively. Cells were washed once with 1×PBS and collected in 1× RIPA buffer (BP-115, Boston Bioproducts) containing phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktail (5872S, Cell Signaling Technologies). Cell lysates were briefly sonicated and subsequently cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein quantification was done by Pierce BCA Assay (23225, Life Technologies).

For immunoblotting analysis, lysates were loaded onto precast SDS–PAGE gels (5671093, Bio-Rad) and subsequently transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane for detection. All primary antibodies were probed overnight at 4 °C, and membranes were washed with TBST and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies for 1 h. Subsequently membranes were washed with TBST and visualized using the Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR).

The primary antibodies used were ATG12 (20H24L24) (701684, Invitrogen, 1:250), LC3b (ab51520, Abcam, 1:3,000), NF-κB p65 (D14E12) (8242, Cell Signalling, 1:1,000), phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) (93H1) (3033, Cell Signalling, 1:1,000), IκBα (9242, Cell Signalling, 1:1,000), NRF2/NFE2L2 (D1Z9C) (12721, Cell Signalling, 1:1,000), SQSTM1/P62 (5114, Cell Signalling, 1:1,000), alpha tubulin (T6074, Sigma Millipore, 1:5,000), Histone H3 (9715, Cell Signalling, 1:1,000), BiP (C50B12, Cell Signalling, 1:1,000), GAPDH (2118S, Cell Signalling, 1:5,000). Secondary antibodies used were IRDye 680RD donkey anti-rabbit (926–68073, LI-COR, 1:5,000) and IRDye 800CW donkey anti-mouse (926–32212, LI-COR, 1:5,000).

Raw data for western Blots shown in Extended Data Figs. 6e, 9c are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Flow cytometry

For the analysis of MHC-I and MHC-I bound to OVA on B16–Ova, cells were treated (or not) with 10 nM of mouse recombinant IFNγ (78021.2, StemCell) for 96 h, lifted from the culture plates using trypsin EDTA and washed once in FACS buffer (PBS containing 5% FBS). After washing, cells were stained at 4 °C for 30 min in FACS buffer containing MHC-I (anti mouse MHC-I (H-2 kb) EFluor450 at 1:200, clone AF6–88.5.5.3, Ebiosciences) and MHC-I bound to OVA (anti mouse OVA 257–264 peptide bound to H2kb PE at 1:100, clone 25-D1.16, Ebiosciences) antibodies. After staining, cells were washed in FACS buffer, and resuspended in FACS buffer containing 1:500 of ToPro-3 for live and dead discrimination (T3606, Invitrogen). Samples were run in triplicate using a LSR Fortessa instrument (BD Biosciences) equipped with 5 lasers and a HTS. FACSDIVA v.6 software was used during data acquisition. Median fluorescent intensities (MFI) were calculated using FlowJo software (FlowJo v.10.6.1). The FACS gating strategy is provided in the Supplementary Information.

Lentivirus production

Lentivirus was produced via co-transfection of packaging (psPAX2, Addgene 12260), envelope (pMD2.G, Addgene 12259) and transfer plasmids into 293T cells using the X-treme Gene 9 transfection reagent (Roche). Sixteen hours after transfection, 293T culture medium was changed to viral collection medium consisting of DMEM supplemented with 1% BSA and 1% penicillin–streptomycin, and cells were incubated for 36–48 h. Virus-containing medium was collected and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm to remove cell debris and then aliquoted and stored at −80 °C.

For mTKO genome-wide and validation library virus production, the MOI was determined by functional titering for each cell line screened by comparing the fraction of surviving cells in transduced versus untransduced populations following puromycin selection.

TCGA analysis

RNA-seq V2 data from the TCGA PanCancer Atlas were retrieved from the cBioPortal using the cgdsr R package v.1.3.0 (10,071 tumour samples across 32 tumour types; 6,935 used for analysis) and National Cancer Institute (NCI) Genomic Data Commons (GDC) using TCGAbiolinks R package v.2.16.0 (9,353 tumour samples; 5,708 used for analysis). Tumour gene expression data were extracted from these datasets for 182 core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes; representative random gene sets (negative control); and expression data for GZMA and PRF1 to calculate the cytolytic index, as previously defined5. Corresponding data for other immune response surrogates (immune characteristics data, hERV expression, innate anti-PD1 resistance or IPRES signature data) were obtained from previous studies4,22,23. Core cancer-intrinsic CTL-evasion genes were stratified by suppressor or sensitizer status and pairwise partial Spearman correlations (pcor.test function; ppcor R package v1.1) were performed between the expression levels of each gene set and immune response surrogates, while controlling for the confounding effects of tumour purity. Tumour purity data were obtained from a previous study41. Unbiased hierarchically clustered heat maps were produced using the gplots R package

In vivo Adar validation

Tumours were established by subcutaneously injecting 100 μl of B16F10 cells stably expressing inducible iShADAR1 (hairpin sequence: GGAGA AGATCTGTGACTATCT) at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells per mouse in the right flank of each mouse. Similarly, tumours in NSG mice were established by subcutaneously injecting 100 μl of cells at a concentration of 5.0 × 104 cells per mouse also into the right flank of each mouse. All cell lines were prepared for implantation by resuspending cells in a 1-to-1 ratio of PBS and Matrigel. Upon establishment of tumours (100–150 mm3), mice were randomized into two groups: vehicle or doxycycline treatment. No power calculation for sample size was performed. The doxycycline treatment group was placed on an ad libitum diet of irradiated Prolab RMH 3000 (standard rodent diet) with 500 ppm (500 mg kg−1) doxycycline, formulated by Testdiets (https://www.labdiet.com/) for the remainder of the experiment. Tumour volume was measured three times per week by caliper, and volume was calculated using the formula 0.5 × W2 × L with the results presented as mean and standard error of mean (s.e.m.). Tumour volume measurements were not blinded. A tumour size limit of 2,000 mm3 was used as a humane end point. At the end of the study, mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation.

Experimental set-up for in vivo screen

Cas9-expressing EMT6–HA cells were infected in triplicate pools with the mVal library at an MOI of around 0.3 at around 7,000× representation. Cells were propagated in vitro with serial cell pellets and maintained at a representation of around 2,000×). On T7, 2.5 × 106 cells within each replicate were pooled and injected subcutaneously into the right hindflank of NCG (n = 90) or BALB/c (n = 107) mice. Sample size was chosen to ensure high library coverage (more than 5,000×) assuming a low cancer cell engraftment success rate (around 5%). Cells from each replicate were distributed evenly amongst mice. For each replicate, in vitro cell populations at were maintained at around 2,000× representation. At each passage, cell pellets were collected at more than 500-fold library coverage for genomic DNA extraction, starting on day 0 post-selection, with T6 representing the preimplantation samples.

Mice were monitored twice weekly for tumour size with calipers. Once tumours became obviously palpable (around 7 days after implantation), a cohort of NSG and BALB/c mice were euthanized (around 30 mice each), then tumours were collected and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen following manual surgical removal to establish an early time point. The remaining tumours were monitored over a period of 5 weeks, with tumours being collected after displaying an obvious pattern of persistent growth. All tumours collected after the first round (that is, the early time point) were categorized into the late time point. A total of 17 early and 72 late tumours were collected from NCG mice, whereas 28 early and 61 late tumours were collected from BALB/c mice.

Sample processing and construction of sequencing library for in vivo screen

For each tumour sample, around 100 mg of tumour tissue was excised and minced into small pieces using a razor blade. Genomic DNA was purified from minced tissues using the Promega Wizard Genomic Purification kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each tumour sample, the gRNA cassette was amplified directly from 1 μg of genomic DNA using primers containing Illumina TruSeq adaptors with i5 and i7 barcodes. The resulting sequencing libraries were pooled and gel-purified. For samples in the in vitro control arm, the gRNA cassette was amplified from 14 μg of genomic DNA. All sequencing libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq 550 instrument.

Analysis of in vivo screen results

Identifying in vivo essential genes.

In vivo essential genes were identified using the early time point under the assumption that gRNA targeting essential genes will be underrepresented relative to the remaining gRNA in the library. Individual genes were ranked according to total gRNA counts within each mouse sample and used to construct gene-level rank distributions. For each gene, NCG and BALB/c rank distributions were pooled and hierarchically clustered using Jensen-Shannon divergence as the distance metric. Discrete clusters were then defined using an adaptive branch pruning method42. Putative essential gene clusters were then defined as those rank distributions that were positively skewed and had <20th percentile median rank. From this list of putative essential genes (that is, genes belonging to pink and turquoise clusters) gene-level gRNA rank distributions were compared between NCG and BALB/c mice, and those that were consistent (that is, FDR < 0.001, two-sided rank-sum test) were classified as in vivo essential genes. To construct a rank plot for in vivo essentials, gene ranks were compared to targeting controls by Wilcoxon rank-sum test and ranked according to FDR. The list of in vivo essential genes was compared to in vitro EMT6 essential genes (BF > 50) with a Venn diagram.

Quantifying strain-dependent in vivo effects.

To quantify strain-dependent differences in the EMT6 in vivo screen, individual genes were ranked according to total gRNA counts within each mouse sample, and time- and strain-matched gene ranks were aggregated as median ranks. From these genes, all in vivo essential genes were omitted. For each time point, pairwise-gene rank comparison between BALB/c and NCG mice was performed using two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and P values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction. Log-transformed P values were signed according to the sign of BALB/c–NCG rank differences and used to construct rank plots.

A gRNA-level analysis of differential fold change (FC) between BALB/c and NCG was also conducted using the formula mean (FCBALB/c) − mean(FCNCG), where FCBALB/c = log2(BALB/c read counts at early or late time points) − log2(BALB/c T6-normalized T0 read counts), and FCNCG = log2(NCG read counts at early or late time points) − log2(NCG T6-normalized T0 read counts). For each gRNA in the mTKO library, T6-normalized T0 read counts were calculated by subtracting the T0 read counts for a given in vivo tumour sample by the preimplantation level obtained in vitro (that is, T6 time point), and subsequently normalizing to read depth. Gene-level statistics were generated by comparing the difference in mean FC of each gRNA across time-point-matched (that is, early versus late) BALB/c versus NCG tumour samples.

Transmission electron microscopy

For electron microscopy sample preparation, Renca wild-type, Fitm2Δ and Atg12Δ cells were cultured to around 80% confluency and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma Aldrich) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 7.4, Sigma Aldrich) for 3 h at room temperature and then shifted to 4 °C overnight. For primary washing, glutaraldehyde and sodium cacodylate were removed from samples, followed by three wash steps for 10 min each using 0.1 M sodium cacodylate rinse buffer (prepared using sodium cacodylate trihydrate diluted in ultrapure water, Sigma Aldrich) at room temperature. The samples were post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide (Sigma Aldrich) in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 90 min at room temperature, followed by three wash steps for 10 min each using 0.1 M sodium cacodylate rinse buffer. The samples were then dehydrated using a graded series of ethanol in distilled water (50%, 70%, 90%, 100%) for 15 min twice at each step. Next, the samples were infiltrated with 50% Quetol651 epoxy resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2 h at room temperature then shifted to 4 °C overnight. Next day, the samples were treated with 100% Quetol651 epoxy resin for 4 h then embedded in fresh resin and polymerized in a 60 °C oven for 48 h. After complete polymerization, the samples were sectioned on a Leica UC7 Ultramicrotome diamond knife to 50–70-nm thickness. Finally, the samples were stained with 2% uranyl acetate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min then rinsed six times with distilled water and stained in 0.1% aqueous lead citrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min. This was followed by a final rinse using distilled water and then samples were air-dried. Sections were observed under a FEI Tecnai 20 TEM at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV. Images were acquired using TEM Imaging and Analysis (TIA) software (v.4.0).

Statistical analysis

For all experiments, the number of technical and/or biological replicates is provided in the figure legends or text. Microsoft Excel (v.16.16.12) was used to organize data into tables. In all cases ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v.8.2.1 (GraphPad) or the R language (v.3.6.1) programming environment using RStudio (v.1.1.456).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed in this study are included in the manuscript. The raw FASTQ files for the sequencing data are available upon request and have also been deposited as a superset to the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession number GSE149936. Descriptions of the analyses, tools and algorithms are provided in the Methods and Reporting Summary. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Custom code for generating the qNormZ scores, differential NormZ scores, essential gene clustering and gene ranks will be available on GitHub (https://github.com/NMikolajewicz/Lawson2020).

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Assessment of core and context-specific mouse fitness genes with the mTKO library.