Graphical abstract

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Main protease, Hydroxamates, Thiosemicarbazones, Inhibitor

Abstract

The emerging COVID-19 pandemic generated by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has severely threatened human health. The main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 is promising target for antiviral drugs, which plays a vital role for viral duplication. Development of the inhibitor against Mpro is an ideal strategy to combat COVID-19. In this work, twenty-three hydroxamates 1a-i and thiosemicarbazones 2a-n were identified by FRET screening to be the potent inhibitors of Mpro, which exhibited more than 94% (except 1c) and more than 69% inhibition, and an IC50 value in the range of 0.12–31.51 and 2.43–34.22 μM, respectively. 1a and 2b were found to be the most effective inhibitors in the hydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones, with an IC50 of 0.12 and 2.43 μM, respectively. Enzyme kinetics, jump dilution and thermal shift assays revealed that 2b is a competitive inhibitor of Mpro, while 1a is a time-dependently inhibitor; 2b reversibly but 1a irreversibly bound to the target; the binding of 2b increased but 1a decreased stability of the target, and DTT assays indicate that 1a is the promiscuous cysteine protease inhibitor. Cytotoxicity assays showed that 1a has low, but 2b has certain cytotoxicity on the mouse fibroblast cells (L929). Docking studies revealed that the benzyloxycarbonyl carbon of 1a formed thioester with Cys145, while the phenolic hydroxyl oxygen of 2b formed H-bonds with Cys145 and Asn142. This work provided two promising scaffolds for the development of Mpro inhibitors to combat COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) generated by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread widely and rapidly around the globe since it was found in December 2019 [1]. So far, millions of people have died because of the infection of COVID-19 [2]. Though some vaccines have been developed and widely vaccinated, the problems of this viral disease have not been essentially solved, especially now, the emergence of coronavirus variants such as delta and kappa [3], [4], [5], [6]. Studies have found that the sera of individuals receiving a dose of Pfizer or AstraZeneca vaccine have limited inhibition of variant Delta [7]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop more effective antivirals.

SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-sense and single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus betacoronavirus and shares 96% sequence to a bat coronavirus [8]. The virus occupies roughly 26–32 kb in length and encodes some structural, non-structural and accessory proteins. The cleavage of pp1a and pp1ab polyproteins into a single non-structural protein is an essential process in virus replication, and the main protease (Mpro) plays a vital role in this process [9], [10], [11]. Also, there is no homology between Mpro and human protease [12]. Therefore, the Mpro is regarded as an important target for designing drugs to combat COVID-19 [13].

The Mpro, a nucleophilic cysteine protease, has three domains: I (residues 8–101), II (102–184), and III (201–306). The first two domains are responsible for the structure of protein and the last domain is in charge of the catalytic process [14]. In the active site, Cys145 and His41 form a catalytic binary. The thiol (-SH) group of cysteine is responsible for the hydrolysis and His41 provides the optimal pH conditions to activate the -SH group, thus it achieves a nucleophilic attack on the substrate [15].

So far, many types of Mpro inhibitors have been reported, such as peptides, non-peptides, drug molecules and natural products [13], [16], [17], [18]. Recently, Wang and his colleagues discovered that peptidomimetic molecules (boceprevir, GC-376, and calpain inhibitors II and XII) have an IC50 value range from single-digit to sub-micromolar [19]. Masitinib, a specific kinase inhibitor, was identified to be effective on tested coronavirus variants (B.1.1.7 and

B.1.351) in vitro [20]. More importantly, recently, Pfizer has released an inhibitor (PF-07321332), currently in Phase 3 clinical trials, is expected to be the first Mpro drug to treat

SARS-CoV-2 [21], [22]. Although it is early to determine potential inhibitors that would be very effective against the virus, they provide an encouraging start for further coronavirus therapeutics. Both New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 (NDM-1) and Mpro are the cysteine proteases [23], [24]. As the NDM-1 inhibitors, the Ebsulfur and Ebselen were reported to inhibit Mpro [25]. Recently, both hydroxamates and thiosmicarbazones were synthesized in our lab and characterized by NMR and mass spectrometry and evaluated to have inhibitory efficacy on NDM-1 [26], [27]. In the same case, we expected these two classes of compounds to have inhibitory activity on Mpro, therefore evaluated them. In this work, we focus on screening the Mpro inhibitor by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) method [28], [29]. The hydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones were found to be the potential scaffolds to target Mpro. Subsequently, the action mechanism of these molecules was characterized and analyzed by enzyme kinetics, jump dilution and thermal shift assays.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Screening of Mpro inhibitor

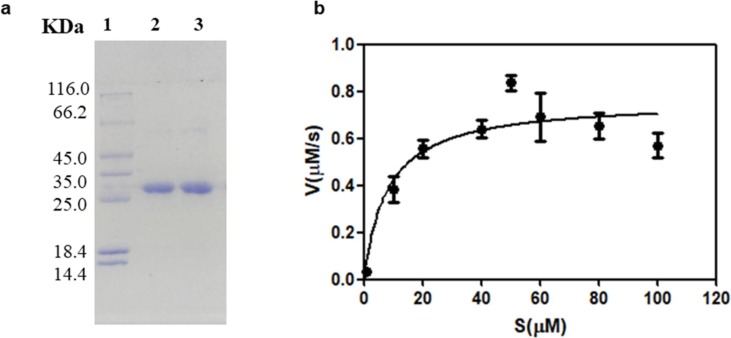

The SARS-CoV-2 Mpro was expressed and purified by the method reported previously [29]. The Mpro gene was inserted into the vector PGEX-6P-1 and expressed in BL21 E. coli. The protein was purified by Ni-NTA and HiTrap Q FF columns, respectively. The SDS-PAGE of the purified protein is shown in Fig. 1 a.

Fig. 1.

The SDS-PAGE of the purified SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (a). Lane 1: protein molecular weight marker, lane 2: purified Mpro, lane 3: Mpro before cleavage with HRV 3C-protease. Activity of Mpro was confirmed by quantification crack of the fluorescent decapeptide Mca–AVLQSGFRK(Dnp)K as substrate (b).

The enzyme activity was assayed by measuring K m and V max values as previously reported method [30]. The employed fluorescent substrate in this experiment was Mca–AVLQSGFRK(Dnp)K.. Various concentrations of the fluorescent substrate (1–100 µM) were premixed with Mpro sample (0.2 µM), respectively. The hydrolysis velocity of substrate was measured, and the data obtained were fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation to give K m and V max values. The calculated K m and V max are 5.4 ± 4.13 µM and 0.68 ± 0.08 nM/s, respectively (Fig. 1b), and Kcat /Km is 6296 M−1 s−1, which is consistent with the data (6925 M−1 s−1) previously reported [30].

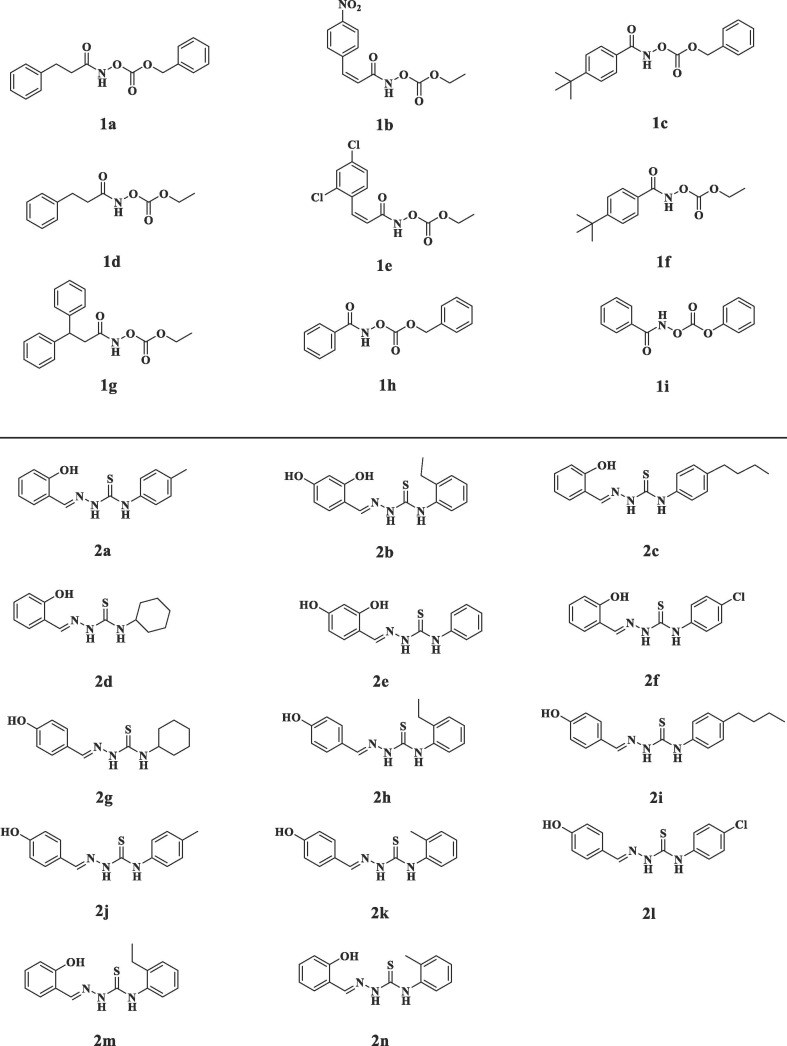

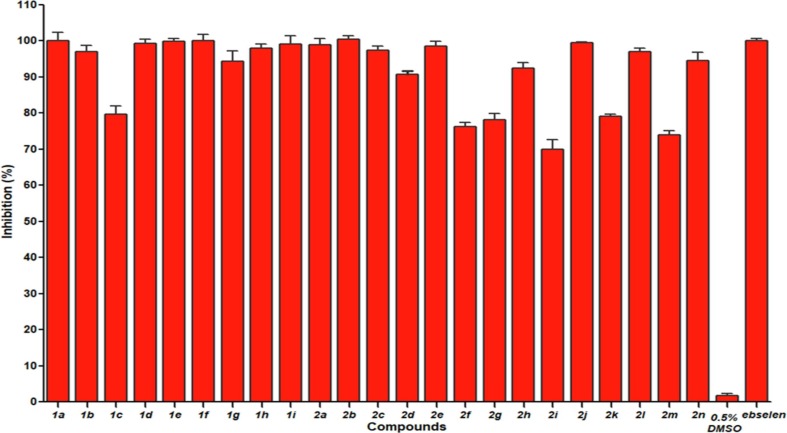

The FRET experiments were performed to screen the potential Mpro inhibitors [28], [29]. The hydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones were prepared in our lab, characterized by 1H and 13C NMR, confirmed by HRMS, and reported to be the inhibitors of metallo-β-lactamases [26], [27] (Fig. 2 ). To explore these molecules whether have potential inhibitory effects against Mpro. We firstly determined the percent inhibition of these compounds as previously reported method [31]. The hydroxamates 1a-i and thiosemicarbazones 2a-n were dissolved in a certain amount of DMSO, and then diluted with assay buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 6.5, 0.4 mM EDTA, 20% glycerol, 120 mM NaCl) [29]. It should be noted that the final concentration of DMSO was less than 0.5%, because the control experiments proved that DMSO at this concentration has no effect on enzyme activity. Percent inhibition of the tested compounds on Mpro is shown in Fig. 3 . It is clearly to be observed that all hydroxamates (50 μM) exhibited more than 94% inhibition on Mpro (except 1c), and all thiosemicarbazones at same concentration shown more than 69% inhibition. Significantly, the thiosemicarbazones tested had better percent inhibition on Mpro than the thiosemicarbazone complexes with iron (III) recently reported (30.62% at 100 μM) [32].

Fig. 2.

Structures of the tested hydroxamates (above) and thiosemicarbazones (below) against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro.

Fig. 3.

Percent inhibition of hydroxamates 1a-i and thiosemicarbazones 2a-n (50 µM) against Mpro. 0.5% DMSO was used as negative control and ebselen was used as positive control.

2.2. Determination of IC50

The inhibitor concentrations causing 50% decrease of enzyme activity (IC50) of hydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones on Mpro were measured as previously reported method [33]. The concentration range of inhibitors was from 0 to 80 μM, and the substrate and protease concentrations were 20 and 0.2 μM, respectively. The measured IC50 data are listed in Table. 1 . The collected data show that all of these compounds exhibited potential inhibition against Mpro, with an IC50 value in the range of 0.12–34.22 μM. The hydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones had an IC50 value range of 0.12–31.51 and 2.43–34.22 μM, respectively, 1a (IC50 = 0.12 μM) and 2b (IC50 = 2.43 μM) were found to be the most effective inhibitors in the two classes of compounds, respectively. These assays revealed that both hydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones are attractive scaffolds for the development of Mpro inhibitors.

Table 1.

The inhibitory activities (IC50, μM) of hydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones on Mpro.

| Compd. | IC50 | Compd. | IC50 | Compd. | IC50 | Compd. | IC50 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 0.12 | 1 g | 18.78 | 2d | 17.61 | 2j | 3.25 | ||||||||||

| 1b | 4.3 | 1 h | 11.7 | 2e | 8.45 | 2 k | 28.81 | ||||||||||

| 1c | 31.51 | 1i | 3.6 | 2f | 32.94 | 2 l | 9.11 | ||||||||||

| 1d | 0.15 | 2a | 3.61 | 2 g | 32.33 | 2 m | 33.40 | ||||||||||

| 1e | 0.42 | 2b | 2.43 | 2 h | 19.10 | 2n | 20.74 | ||||||||||

| 1f | 1.46 | 2c | 4.37 | 2i | 34.22 |

2.3. Inhibition mode assay

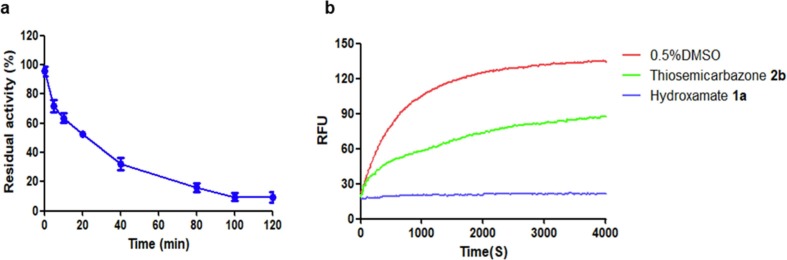

Given the best potency, the time-dependent inhibition of hydroxamate 1a on Mpro was assayed. As shown in Fig. 4 a, the residual activity of Mpro decreased with the increase of premix time of protease with inhibitor (1.25 µM), and 1a exhibited about 90% inhibition after incubation for 100 min, indicating that 1a is a time-dependent inhibitor [34].

Fig. 4.

Time-dependent inhibition curve of hydroxamate 1a (1.25 µM) on Mpro (a). Progress curves of Mpro activity change in the presence of hydroxamate 1a and thiosemicarbazone 2b (b). 0.5% DMSO was used for the blank control.

The reversibility of hydroxamate 1a and thiosemicarbazone 2b binding to Mpro was evaluated by jump dilution tests [29], [35], [36]. The Mpro sample was incubated with a high concentration of inhibitors (equivalent to 50 × IC50) 1a (6 µM) and 2b (122 µM) for 2 h, respectively, so that the inhibitor could fully occupy enzymatic active sites, the resulting mixtures were diluted 100-fold with the fluorescence substrate solution, and the enzymatic residual activity was determined by monitoring the fluorescence. It is clearly observed in Fig. 4b that in the presence of 1a, the enzyme activity did not recover after the dilution. However, the enzyme treated with 2b recovered about 60% activity after dilution for 4000 s. These results indicate that the thiosemicarbazone reversibly, but hydroxamate like the Ebselen and Ebsulfur, irreversibly inhibit Mpro [29].

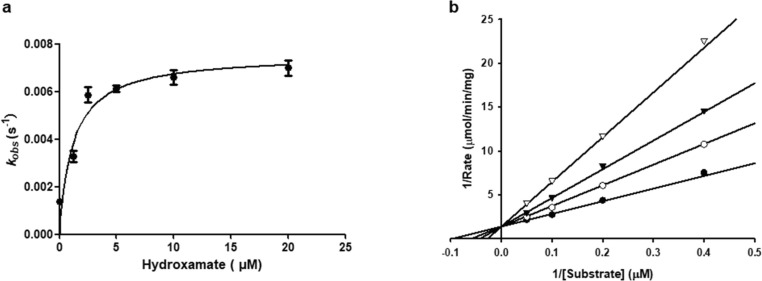

To further study the inhibition mode of the hydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones on Mpro, 1a and 2b were chosen to determine the enzyme kinetic parameters [37], [38], [39]. The above assay reveals that 1a inhibit Mpro in a time-dependent pattern, and the kinetic progression curves exhibited a biphasic character (Fig. 5 a), suggesting the inactivation rate follows pseudo-first-order rate kinetics. These results imply that the hydroxamate may covalently bind to the target [38]. The K obs (observed rate constant) were fitted against inhibitor concentration by nonlinear regression to calculate K I (the concentration of inacti-vator at the half-maximum inactivation rate constant), k inact, and k inact /K I values, which are 1.18 ± 0.43 µM, 0.0075 ± 0.0005 s−1, and 6.4 × 103 M−1s−1, respectively [37].

Fig. 5.

The hyperbolic plots of Kobs against concentrations of hydroxamate 1a (a). The Lineweaver-Burk plots of Mpro catalyzed hydrolysis of thiosemicarbazone 2b. The concentrations of inhibitors were 0 (●), 2.5 (○), 5(▾), 10 (▽) µM (b).

The inhibition mode of thiosemicarbazone 2b was identified by analyzing Lineweaver–Burk plots, and K i (inhibiton constant) value was determined by fitting initial velocity versus substrate concentrations at each inhibitor concentration using SigmaPlot 12.0. The concentrations of substrate and inhibitor were in the range of 2.5–20 and 0–10 µM, respectively. The enzyme (0.2 μM) was incubated with inhibitor for 2 h, and the reaction was monitored when substrate was added. The Lineweaver–Burk plots of fluorescent substrate hydrolysis by Mpro in the absence and presence of 2b are shown in Fig. 5b, which indicate that 2b is a competitive inhibitor [39], and the calculated K i value is 3.9 µM.

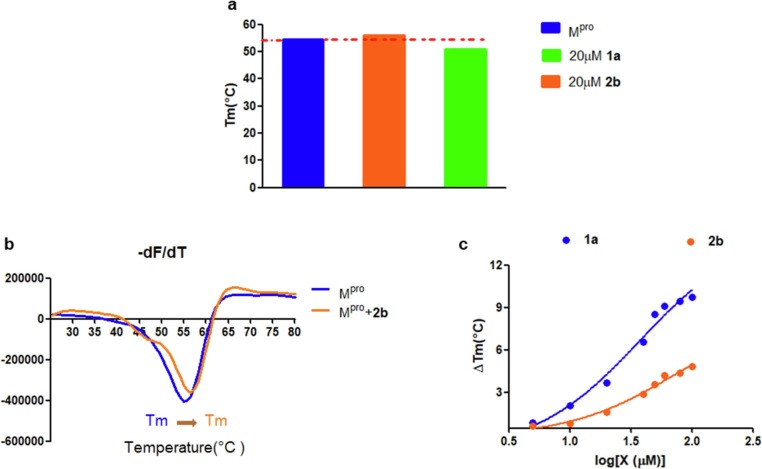

2.4. Thermal shift assay

Thermal shift analysis, a powerful technique, is used to screen molecules that impact protein stability via monitoring a shift in the melting temperature (Tm) of the protein [40]. In general, the binding of a small molecule stabilizes protein, leading to an increased Tm value. However, a decreased Tm value results in destabilization of the protein [41]. To investigate the interaction of Mpro with inhibitors, the Mpro (20 μM) was premixed with hydroxamate 1a (20 μM) and thiosemicarbazones 2b (20 μM) for 2 h, respectively, and then the mixtures were treated with the SYPROR orange dye. The reaction of the protein and inhibitor was heated from 25 to 80 °C in 0.8 °C increment. As shown in Fig. 6 a, the Tm of Mpro was 54.49 °C. While in the presence of 1a, the determined Tm value of protein decreased to 50.81 °C, indicating that binding of hydroxamates to protein leads to destabilization, like the Mpro inhibitors ebselen and disulfiram previously reported [42]. In contrast, in the presence of 2b, the Tm of protein increased from 54.49 to 56.11 °C, suggesting that the tightly binding of thiosemicarbazones to Mpro increases the stability of the protein.

Fig. 6.

The melting temperature (Tm) of Mpro in the absence and presence of 1a and 2b (a). Fluorescence based thermal shift assays of 2b interaction with Mpro as indicated by dF/dT (b). Dose-dependent melting temperature shift (c).

Moreover, we performed a dose-dependent determination of Tm as the reported method [33]. The Mpro (20 µM) was mixed with various concentrations of 1a and 2b (10–100 µM) for 2 h, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6c, the melting temperature shifts (ΔTm) of Mpro increased with the increase of inhibitor concentration (10–100 μM), implying that the stabilization of Mpro to thermal denaturation is concentration-dependent.

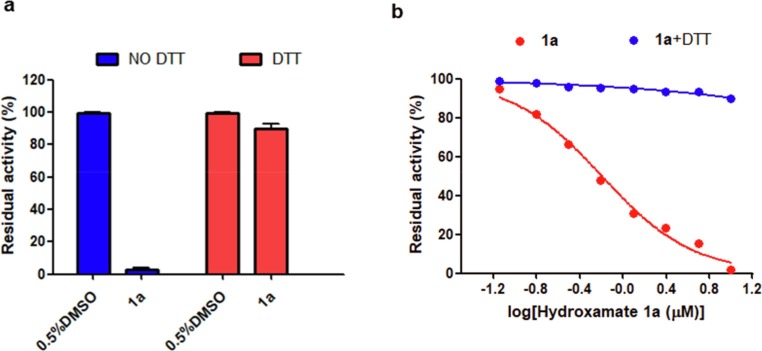

2.5. Dithiothreitol (DTT) assay

To verify the action site of hydroxamates 1a to Mpro, DTT experiments were performed as previously reported method [42]. The Mpro (0.2 μM) was premixed with 1a (1.25 μM) in the assay buffer (see above) supplemented with and without DTT (4 mM) for 2 h, respectively. The fluorescent substrate (20 μM) was added to the mixture solution and then the initial reaction rate was determined. As shown in Fig. 7 a, 1a had a potential inhibitory effect on the protein in the absence of DTT. Nevertheless, 4a did not show a significant inhibition on the protein in the presence of DTT.

Fig. 7.

Inhibition (a) and dose-dependent inhibition (b) of hydroxamate 1a on Mpro in the presence and absence of DTT.

Meanwhile, we also carried out a dose-dependent inhibition experiments of Mpro. As shown in Fig. 7b, the residual activity of protein decreased with the increase of 1a concentration (0–10 μM) in the absence of DTT. In contrast, in the presence of DTT, the enzymatic activity was not effectively inhibited. Also the residual activity of enzyme was not associated with inhibitor concentration. The inhibition of 1a on the enzyme was abolished, probably because the binding site of 1a on enzyme was disrupted by DTT. The above experimental results implied that the inhibition of hydroxamate 1a on Mpro was realized by cysteine modification and 1a is also the promiscuous cysteine protease inhibitor [29].

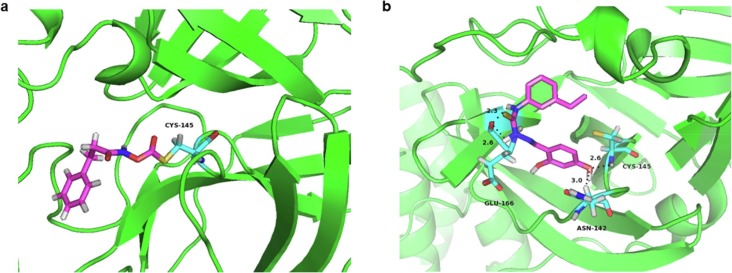

2.6. Molecular modeling

To predict the binding affinity and pose of both hydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones to Mpro, 1a and 2b were docked into the active sites of the crystal structure of Mpro (PDB ID: 6LU7) [43]. The minimized binding free energy of 1a and 2b were calculated to be −4.53 and −6.64 kcal/mol, respectively. Docking studies revealed that the carbonyl and amine group of 1a first approach Cys145 through H‐bond, and 1a also interacted with His41 residue, increasing the affinity of this substructure to the protein. Subsequently, the action mechanism might be as previously reported [15], [19], [44], [45], [46]. The SH group of Cys145 was deprotonated by His41, initiated a nucleophilic attack on benzyloxycarbonyl carbon to form thioester (Fig. 8 a), and control experiments proved that N-hydroxy-3, 3-diphenylpropanamide had no inhibitory effect on Mpro, which also proved that the interaction site of the hydroxamate and protease is the benzyloxycarbonyl instead of amide carbonyl.

Fig. 8.

The lowest-energy conformations of the complex of inhibitors with Mpro. Interactions formed between hydroxamate 1a (a) and thiosemicarbazone 2b (b) and surrounding residues, the Mpro skeleton is exhibited as a green cartoon and the inhibitors and residues are exhibited as sticks colored by elements (N, blue; O, red; H, white; S, yellow; C, purple). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

For the complex Mpro/2b (Fig. 8b), the phenolic hydroxyl oxygen formed H-bond with Cys145 (2.6 Å) and Asn142 (3.0 Å), also two nitrogen atoms of thiourea interacted with Gln166 (2.3 Å, 2.6 Å) through H-bond, tightly anchoring the 2b complex in the active site of Mpro [47].

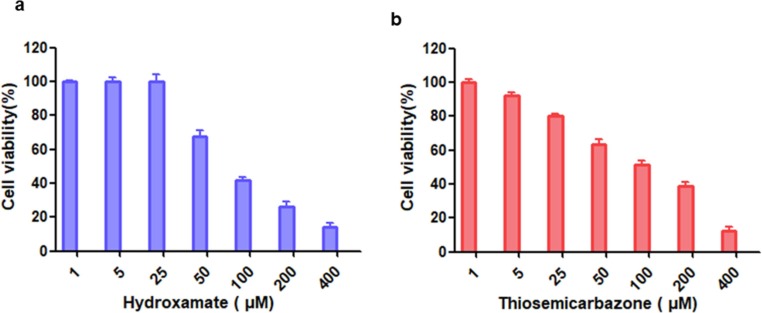

2.7. Cytotoxicity assay

The potential toxicity of compounds is a vital criterion to evaluate their clinical medical applications. The cytotoxicity of the hydroxamate 1a and thiosemicarbazone 2b (1–400 μM) were assayed by using mouse fibroblast (L929) cells [48], [49]. As shown in Fig. 9 , the cell viability was over 98% in the presence of 25 µM 1a, but only 80% of cells tested maintained viability in the presence of 2b at same concentration, indicating that the hydroxamate has low cytotoxicity, and the thiosemicarbazone has certain cytotoxicity on L929 cells.

Fig. 9.

The cytotoxicity assays of inhibitors (1–400 µM) hydroxamate 1a (a) and thiosemicarbazone 2b (b) on mouse fibroblast (L929) cells.

Given that both thydroxamates and thiosemicarbazones were reported to have anticancer efficacy [50], [51], [52], [53], we performed toxicity assay and fluorescence microscopy images of the human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) treated with these compounds (see supporting information) [54], [55]. As shown in Fig. S1, more than 98% of cells maintained viability in the presence of 1a and 2b (25 µM). However, the cell viability was over 85% for 100 µM inhibitors (Fig.S2) and less than 30% for 800 µM inhibitors, indicating that 1a and 2b have low cytotoxicity at a low concentration.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Enzymatic activity assay

The enzyme activity was evaluated according to previously described method [30]. The fluorescence substrate Mca–AVLQSGFR-K(Dnp)K was prepared into samples with different concentration (1–100 µM). The Mpro (0.2 µM) was added to the assay buffer containing substrate, and then the fluorescence change of substrate was monitored on Microplate Reader (Var ioskan flash, emission, 405 nm / excitation, 320 nm) for 4 min. The initial reaction rate of enzyme hydrolyzing substrate was calculated by linear regression (Graphpad Prism 5) and the Michaelis-Menten equation was used to plot against the substrate concentration.

3.2. Enzymatic inhibition assay

To obtain the percent inhibition, the hydroxamates 1a-i and thiosemicarbazones 2a-n were first dissolved in DMSO and then diluted with assay buffer. The protease (0.2 μM) was mixed with inhibitors (50 μM) at 37 °C for 2 h. Finally, the substrate (20 μM) was added to the mixture solutions, and then the hydrolysis of fluorescence substrate was monitored on Microplate Reader for 1 min. The enzyme was treated with 0.5% DMSO as the negative control and ebselen was used as the positive control [31].

3.3. Inhibition mode assays

The inhibition mode of hydroxamate 1a on Mpro was evaluated and the kinetic parameters were determined [37], [38]. In detail, the substrate (20 μM) was added into assay buffer supplement with 1a at different concentrations (1–30 μM), respectively. When the enzyme sample was added and then the hydrolysis of fluorescence substrate was monitored on Microplate Reader for 5 min. The K obs was obtained by fitting the enzyme inhibition progress curves to the equation (1).

| (1) |

Where Rt is the fluorescence value at time t, R0 is the initial fluorescence value at time 0, V0 is the initial reaction rate, K obs values was obtained and then fitted into Equation (2) to aqucire k inact and K I values.

| (2) |

Where [I] is inhibitor concentration, k inact is the rate constant of inactivation.

3.4. Thermal shift assay

Thermal shift assay was performed according to the previously described [33], [40]. The dyes used in this experiment was SYPRO Orange (10 X final concentration), Mpro (20 µM) was premixed with hydroxamate 1a and thiosemicarbazone 2b (10–100 μM) in Tris buffer (60 mM, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) for 2 h, respectively. When the SYPRO Orange was added in 96-well plate and then the fluorescence was monitored on an ICycler (Bio-Rad, emission, 570 nm / excitation, 300 nm) from 25 to 80 °C in steps of 0.8 °C. The protein melting temperature (Tm) was obtained by using the Boltzmann model (Protein Thermal Shift Software v1.3) to analyze the mid log of the transition state of protein from the nature to the denatured. The enzyme sample in wells was treated with 0.5% DMSO as blank controls, and both ligands only control and no protein control were used as the negative control to exclude the contamination in wells and ligand–dye interactions interference.

3.5. Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of hydroxamate 1a and thiosemicarbazone 2b were tested with L929 cells. The cells were cultured into 96-well plates (1.0 × 103 cells /well) containing culture medium for 2 days. Subsequently, the cells were premixed with inhibitors (1–400 μM) for another 24 h, respectively. The cell supernatant was removed and added MTT solution (10 μL/well) for 4 h, and then added DMSO (100 μL/well) for 20 min. The OD490 values (optical density) were measured on Microplate Reader [48].

4. Conclusions

The main protease (Mpro) that the SARS-CoV-2 viral replication employed was expressed and purified by Ni-NTA and HiTrap Q FF columns, and Km and Vmax were determined to be 5.4 ± 4.13 µM and 0.68 ± 0.08 nM/s, respectively. Twenty-three hydroxamates 1a-i and thiosemicarbazones 2a-n were identified by FRET screening to be the potent inhibitors of Mpro, which exhibited more than 94% (except 1c) and more than 69% inhibition, and an IC50 value in the range of 0.12–31.51 and 2.43–34.22 µM, respectively, the hydroxamate 1a (IC50 = 0.12 μM) and thiosemicarbazone 2b (IC50 = 2.43 μM,) were found to be the most effective inhibitors. The enzyme kinetics, jump dilution and thermal shift assays showed that 2b is a competitive inhibitor, while 1a is a time-dependent inhibitor; 2b reversibly but 1a irreversibly bound to the target; the binding of 2b increases but 1a decreases the stability of the protein, and DTT assays indicate that 1a is the promiscuous cysteine protease inhibitor. Cytotoxicity assays showed that 1a has low cytotoxicity and 2b has certain cytotoxicity on the mouse fibroblast cells (L929). Docking studies revealed potential binding modes of the two most potent inhibitors to Mpro, in which the benzyloxycarbonyl carbon of 1a might be formed a thioester bond with Cys145, while the phenolic hydroxyl oxygen of 2b formed H-bonds with Cys145 and Asn142.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant (22077100) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the grant (2019KW-068) from Shaanxi Province International Cooperation Project.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bioorg.2022.105799.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Dimeglio C., Milhes M., Loubes J.-M., Ranger N., Mansuy J.-M., Trémeaux P., Jeanne N., Latour J., Nicot F., Donnadieu C., Izopet J. Influence of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7, vaccination, and public health measures on the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses. 2021;13(5):898. doi: 10.3390/v13050898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pascual-Iglesias A., Canton J., Ortega-Prieto A.M., Jimenez-Guardeño J.M., Regla-Nava J.A. An overview of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Pathogens. 2021;10(8):1030. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10081030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Q.A. Al Khames Aga, W.H. Alkhaffaf, T.H. Hatem, K.F. Nassir, Y. Batineh, A.T. Dahham, D. Shaban, L.A. Al Khames Aga, M.Y.R. Agha, M. Traqchi, Safety of COVID-19 vaccines, J Med Virol, 93 (2021) 6588-6594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Farinholt T., Doddapaneni H., Qin X., Menon V., Meng Q., Metcalf G., Chao H., Gingras M.C., Avadhanula V., Farinholt P., Agrawal C., Muzny D.M., Piedra P.A., Gibbs R.A., Petrosino J. Transmission event of SARS-CoV-2 delta variant reveals multiple vaccine breakthrough infections. BMC Med. 2021;19:255. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A. Stern, S. Fleishon, T. Kustin, E. Dotan, M. Mandelboim, O. Erster, E. Mendelson, O. Mor, N.S. Zuckerman, (2021).

- 6.Izumi H., Nafie L.A., Dukor R.K. Conformational variability correlation prediction of transmissibility and neutralization escape ability for multiple mutation SARS-CoV-2 strains using SSSCPreds. ACS Omega. 2021;6(29):19323–19329. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c03055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Planas D., Veyer D., Baidaliuk A., Staropoli I., Guivel-Benhassine F., Rajah M.M., Planchais C., Porrot F., Robillard N., Puech J., Prot M., Gallais F., Gantner P., Velay A., Le Guen J., Kassis-Chikhani N., Edriss D., Belec L., Seve A., Courtellemont L., Péré H., Hocqueloux L., Fafi-Kremer S., Prazuck T., Mouquet H., Bruel T., Simon-Lorière E., Rey F.A., Schwartz O. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596(7871):276–280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho E., Rosa M., Anjum R., Mehmood S., Soban M., Mujtaba M., Bux K., Moin S.T., Tanweer M., Dantu S., Pandini A., Yin J., Ma H., Ramanathan A., Islam B., Mey A., Bhowmik D., Haider S. Dynamic Profiling of beta-coronavirus 3CL M(pro) protease ligand-binding sites. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021;61:3058–3073. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved alpha-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368:409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baig M.H., Sharma T., Ahmad I., Abohashrh M., Alam M.M., Dong J.-J. Is PF-00835231 a pan-SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor? a comparative study. Molecules. 2021;26(6):1678. doi: 10.3390/molecules26061678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiao J., Li Y.-S., Zeng R., Liu F.-L., Luo R.-H., Huang C., Wang Y.-F., Zhang J., Quan B., Shen C., Mao X., Liu X., Sun W., Yang W., Ni X., Wang K., Xu L., Duan Z.-L., Zou Q.-C., Zhang H.-L., Qu W., Long Y.-H.-P., Li M.-H., Yang R.-C., Liu X., You J., Zhou Y., Yao R., Li W.-P., Liu J.-M., Chen P., Liu Y., Lin G.-F., Yang X., Zou J., Li L., Hu Y., Lu G.-W., Li W.-M., Wei Y.-Q., Zheng Y.-T., Lei J., Yang S. SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors with antiviral activity in a transgenic mouse model. Science. 2021;371(6536):1374–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.abf1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niesor E.J., Boivin G., Rhéaume E., Shi R., Lavoie V., Goyette N., Picard M.-E., Perez A., Laghrissi-Thode F., Tardif J.-C. Inhibition of the 3CL protease and SARS-CoV-2 replication by dalcetrapib. ACS Omega. 2021;6(25):16584–16591. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c01797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan H.T.H., Moesser M.A., Walters R.K., Malla T.R., Twidale R.M., John T., Deeks H.M., Johnston-Wood T., Mikhailov V., Sessions R.B., Dawson W., Salah E., Lukacik P., Strain-Damerell C., Owen C.D., Nakajima T., Świderek K., Lodola A., Moliner V., Glowacki D.R., Spencer J., Walsh M.A., Schofield C.J., Genovese L., Shoemark D.K., Mulholland A.J., Duarte F., Morris G.M. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) peptide inhibitors from modelling substrate and ligand binding. Chem. Sci. 2021;12(41):13686–13703. doi: 10.1039/d1sc03628a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva J.R.A., Kruger H.G., Molfetta F.A. Drug repurposing and computational modeling for discovery of inhibitors of the main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2. RSC Adv. 2021;11(38):23450–23458. doi: 10.1039/d1ra03956c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Citarella A., Scala A., Piperno A., Micale N. SARS-CoV-2 M(pro): a potential target for peptidomimetics and small-molecule inhibitors. Biomolecules. 2021;11(4):607. doi: 10.3390/biom11040607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J., Lin X., Xing N., Zhang Z., Zhang H., Wu H., Xue W. Structure-based discovery of novel nonpeptide inhibitors targeting SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021;61:3917–3926. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma D., Kunamneni A. Recent progress in the repurposing of drugs/molecules for the management of COVID-19. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2021;19:889–897. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2021.1860020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christy M.P., Uekusa Y., Gerwick L., Gerwick W.H. Natural products with potential to treat RNA virus pathogens including SARS-CoV-2. J. Nat. Prod. 2021;84:161–182. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang H., Yang J. A review of the latest research on M(pro) targeting SARS-COV inhibitors. RSC Med. Chem. 2021;12:1026–1036. doi: 10.1039/d1md00066g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drayman N., DeMarco J.K., Jones K.A., Azizi S.-A., Froggatt H.M., Tan K., Maltseva N.I., Chen S., Nicolaescu V., Dvorkin S., Furlong K., Kathayat R.S., Firpo M.R., Mastrodomenico V., Bruce E.A., Schmidt M.M., Jedrzejczak R., Muñoz-Alía M.Á., Schuster B., Nair V., Han K.-Y., O’Brien A., Tomatsidou A., Meyer B., Vignuzzi M., Missiakas D., Botten J.W., Brooke C.B., Lee H., Baker S.C., Mounce B.C., Heaton N.S., Severson W.E., Palmer K.E., Dickinson B.C., Joachimiak A., Randall G., Tay S. Masitinib is a broad coronavirus 3CL inhibitor that blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2021;373(6557):931–936. doi: 10.1126/science.abg5827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao K., Wang R., Chen J., Tepe J.J., Huang F., Wei G.W. Perspectives on SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2021;64:16922–16955. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Owen D.R., Allerton C.M.N., Anderson A.S., Aschenbrenner L., Avery M., Berritt S., Boras B., Cardin R.D., Carlo A., Coffman K.J., Dantonio A., Di L.i., Eng H., Ferre R.A., Gajiwala K.S., Gibson S.A., Greasley S.E., Hurst B.L., Kadar E.P., Kalgutkar A.S., Lee J.C., Lee J., Liu W., Mason S.W., Noell S., Novak J.J., Obach R.S., Ogilvie K., Patel N.C., Pettersson M., Rai D.K., Reese M.R., Sammons M.F., Sathish J.G., Singh R.S.P., Steppan C.M., Stewart A.E., Tuttle J.B., Updyke L., Verhoest P.R., Wei L., Yang Q., Zhu Y. An oral SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science. 2021;374(6575):1586–1593. doi: 10.1126/science.abl4784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang T., Xu K., Zhao L., Tong R., Xiong L., Shi J. Recent research and development of NDM-1 inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021;223 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee J., Worrall L.J., Vuckovic M., Rosell F.I., Gentile F., Ton A.T., Caveney N.A., Ban F., Cherkasov A., Paetzel M., Strynadka N.C.J. Crystallographic structure of wild-type SARS-CoV-2 main protease acyl-enzyme intermediate with physiological C-terminal autoprocessing site. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5877. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19662-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y., Yu J., Wang L., Yang K., Liu F., Jiang R., Yang X., You T., Liu X., Yang X., Bai F., Liu H., Liu X., Guddat L.W., Xu W., Xiao G., Qin C., Shi Z., Jiang H., Rao Z., Yang H. Structure of M(pro) from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chigan J.-Z., Li J.-Q., Ding H.-H., Xu Y.-S., Liu L.u., Chen C., Yang K.-W. Hydroxamates as a potent skeleton for the development of metallo-β-lactamase inhibitors. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2022;99(2):362–372. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J.Q., Sun L.Y., Jiang Z.H., Chen C., Gao H., Chigan J.Z., Ding H.H., Yang K.W. Diaryl-substituted thiosemicarbazone: A potent scaffold for the development of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1 inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;107 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alhadrami H.A., Hassan A.M., Chinnappan R., Al-Hadrami H., Abdulaal W.H., Azhar E.I., Zourob M. Peptide substrate screening for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay. Mikrochim. Acta. 2021;188:137. doi: 10.1007/s00604-021-04766-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun L.Y., Chen C., Su J., Li J.Q., Jiang Z., Gao H., Chigan J.Z., Ding H.H., Zhai L., Yang K.W. Ebsulfur and Ebselen as highly potent scaffolds for the development of potential SARS-CoV-2 antivirals. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;112 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iketani S., Forouhar F., Liu H., Hong S.J., Lin F.Y., Nair M.S., Zask A., Huang Y., Xing L., Stockwell B.R., Chavez A., Ho D.D. Lead compounds for the development of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease inhibitors. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2016. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22362-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y., Chen C., Sun L.Y., Gao H., Zhen J.B., Yang K.W. meta-Substituted benzenesulfonamide: a potent scaffold for the development of metallo-beta-lactamase ImiS inhibitors. RSC Med. Chem. 2020;11:259–267. doi: 10.1039/c9md00455f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atasever Arslan B., Kaya B., Sahin O., Baday S., Saylan C.C., Ulkuseven B. The iron(III) and nickel(II) complexes with tetradentate thiosemicarbazones. Synthesis, experimental, theoretical characterization, and antiviral effect against SARS-CoV-2. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1246 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma C., Sacco M.D., Hurst B., Townsend J.A., Hu Y., Szeto T., Zhang X., Tarbet B., Marty M.T., Chen Y., Wang J. Boceprevir, GC-376, and calpain inhibitors II, XII inhibit SARS-CoV-2 viral replication by targeting the viral main protease. Cell Res. 2020;30:678–692. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0356-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J.Q., Chen C., Yao M., Sun L.Y., Gao H., Chigan J., Yang K.W. Hydroxamic acid with benzenesulfonamide: An effective scaffold for the development of broad-spectrum metallo-beta-lactamase inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2020;105 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.104436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghazanfari D., Noori M.S., Bergmeier S.C., Hines J.V., McCall K.D., Goetz D.J. A novel GSK-3 inhibitor binds to GSK-3beta via a reversible, time and Cys-199-dependent mechanism. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021;40 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker E.N., Song J., Kishore Kumar G.D., Odutola S.O., Chavarria G.E., Charlton-Sevcik A.K., Strecker T.E., Barnes A.L., Sudhan D.R., Wittenborn T.R., Siemann D.W., Horsman M.R., Chaplin D.J., Trawick M.L., Pinney K.G. Synthesis and biochemical evaluation of benzoylbenzophenone thiosemicarbazone analogues as potent and selective inhibitors of cathepsin L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23(21):6974–6992. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strelow J.M. A perspective on the kinetics of covalent and irreversible inhibition. SLAS Discov. 2017;22(1):3–20. doi: 10.1177/1087057116671509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C., Sun L.Y., Gao H., Kang P.W., Li J.Q., Zhen J.B., Yang K.W. Identification of cisplatin and palladium(II) complexes as potent metallo-beta-lactamase inhibitors for targeting carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020;6:975–985. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ge Y., Xu L.W., Liu Y., Sun L.Y., Gao H., Li J.Q., Yang K. Dithiocarbamate as a valuable scaffold for the inhibition of metallo-beta-lactmases. Biomolecules. 2019;9 doi: 10.3390/biom9110699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sviben D., Bertoša B., Hloušek-Kasun A., Forcic D., Halassy B., Brgles M. Investigation of the thermal shift assay and its power to predict protein and virus stabilizing conditions. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018;161:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhusal R.P., Patel K., Kwai B.X.C., Swartjes A., Bashiri G., Reynisson J., Sperry J., Leung I.K.H. Development of NMR and thermal shift assays for the evaluation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isocitrate lyase inhibitors. Medchemcomm. 2017;8(11):2155–2163. doi: 10.1039/c7md00456g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma C., Hu Y., Townsend J.A., Lagarias P.I., Marty M.T., Kolocouris A., Wang J. Ebselen, disulfiram, carmofur, PX-12, tideglusib, and shikonin are nonspecific promiscuous SARS-CoV-2 Main protease inhibitors. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020;3(6):1265–1277. doi: 10.1021/acsptsci.0c00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.G.G. Rossetti, M. Ossorio, S. Barriot, L. Tropia, V.S. Dionellis, C. Gorgulla, H. Arthanari, P. Mohr, R. Gamboni, T.D. Halazonetis, (2020).

- 44.Tam N.M., Nam P.C., Quang D.T., Tung N.T., Vu V.V., Ngo S.T. Binding of inhibitors to the monomeric and dimeric SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Rsc Adv. 2021;11(5):2926–2934. doi: 10.1039/d0ra09858b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malla T.R., Tumber A., John T., Brewitz L., Strain-Damerell C., Owen C.D., Lukacik P., Chan H.T.H., Maheswaran P., Salah E., Duarte F., Yang H., Rao Z., Walsh M.A., Schofield C.J. Mass spectrometry reveals potential of beta-lactams as SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 2021;57:1430–1433. doi: 10.1039/d0cc06870e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.P.W. Thomas, M. Cammarata, J.S. Brodbelt, A.F. Monzingo, R.F. Pratt, W. Fast, A Lysine-Targeted Affinity Label for Serine-beta-Lactamase Also Covalently Modifies New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase-1 (NDM-1), Biochemistry 58(25) (2019) 2834-2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.S.O. Aftab, M.Z. Ghouri, M.U. Masood, Z. Haider, Z. Khan, A. Ahmad, N. Munawar, Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase as a potential therapeutic drug target using a computational approach, J Transl Med, 18 (2020) 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Ding H.-H., Zhao M.-H., Zhai L.e., Zhen J.-B., Sun L.-Y., Chigan J.-Z., Chen C., Li J.-Q., Gao H., Yang K.-W. A quinine-based quaternized polymer: a potent scaffold with bactericidal properties without resistance dagger. Polym. Chem. 2021;12(16):2397–2403. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Wahaibi L.H., Mostafa A., Mostafa Y.A., Abou-Ghadir O.F., Abdelazeem A.H., Gouda A.M., Kutkat O., Abo Shama N.M., Shehata M., Gomaa H.A.M., Abdelrahman M.H., Mohamed F.A.M., Gu X., Ali M.A., Trembleau L., Youssif B.G.M. Discovery of novel oxazole-based macrocycles as anti-coronaviral agents targeting SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;116:105363. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strobl J.S., Nikkhah M., Agah M. Actions of the anti-cancer drug suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) on human breast cancer cytoarchitecture in silicon microstructures. Biomaterials. 2010;31(27):7043–7050. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.You B.R., Han B.R., Park W.H. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid increases anti-cancer effect of tumor necrosis factor-α through up-regulation of TNF receptor 1 in lung cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8(11):17726–17737. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maqbool S.N., Lim S.C., Park K.C., Hanif R., Richardson D.R., Jansson P.J., Kovacevic Z. Overcoming tamoxifen resistance in oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer using the novel thiosemicarbazone anti-cancer agent, DpC. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020;177:2365–2380. doi: 10.1111/bph.14985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sibuh B.Z., Gupta P.K., Taneja P., Khanna S., Sarkar P., Pachisia S., Khan A.A., Jha N.K., Dua K., Singh S.K., Pandey S., Slama P., Kesari K.K., Roychoudhury S. Synthesis, in silico study, and anti-cancer activity of thiosemicarbazone derivatives. Biomedicines. 2021;9(10):1375. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9101375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen C., Yang K.-W., Zhai L.e., Ding H.-H., Chigan J.-Z. Dithiocarbamates combined with copper for revitalizing meropenem efficacy against NDM-1-producing Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Bioorg. Chem. 2022;118:105474. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li J., Yang W., Zhou W., Li C., Cheng Z., Li M., Xie L., Li Y. Aggregation-induced emission in fluorophores containing a hydrazone structure and a central sulfone: restricted molecular rotation. Rsc Adv. 2016;6(42):35833–35841. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.