Abstract

Objectives.

Binaural pitch fusion is the perceptual integration of stimuli that evoke different pitches between the ears into a single auditory image. Adults who use hearing aids (HAs) or cochlear implants (CIs) often experience abnormally broad binaural pitch fusion, such that sounds differing in pitch by as much as 3–4 octaves are fused across ears, leading to spectral averaging and speech perception interference. The main goal of this study was to measure binaural pitch fusion in children with different hearing device combinations, and compare results across groups and with adults. A second goal was to examine the relationship of binaural pitch fusion to interaural pitch differences or pitch match range, a measure of sequential pitch discriminability.

Design.

Binaural pitch fusion was measured in children between the ages of 6.1–11.1 years with bilateral HAs (n=9), bimodal CI (n=10), bilateral CIs (n=17), as well as normal-hearing (NH) children (n=21). Depending on device combination, stimuli were pure tones or electric pulse trains delivered to individual electrodes. Fusion ranges were measured using simultaneous, dichotic presentation of reference and comparison stimuli in opposite ears, and varying the comparison stimulus to find the range that fused with the reference stimulus. Interaural pitch match functions were measured using sequential presentation of reference and comparison stimuli, and varying the comparison stimulus to find the pitch match center and range.

Results.

Children with bilateral HAs had significantly broader binaural pitch fusion than children with NH, bimodal CI, or bilateral CIs. Children with NH and bilateral HAs, but not children with bimodal or bilateral CIs, had significantly broader fusion than adults with the same hearing status and device configuration. In children with bilateral CIs, fusion range was correlated with several variables that were also correlated with each other: PTA in the second implanted ear prior to CI, and duration of prior bilateral HA, bimodal CI, or bilateral CI experience. No relationship was observed between fusion range and pitch match differences or range.

Conclusions.

The findings suggest that binaural pitch fusion is still developing in this age range, and depends on hearing device combination but not on interaural pitch differences or discriminability.

Keywords: pitch, fusion, binaural, children, hearing aids, bimodal, cochlear implants

summary:

Children with hearing loss have broader fusion than children with normal-hearing. Differences depend on device combination.

Introduction

Options for the treatment of sensorineural hearing loss include the use of hearing aids (HAs), cochlear implants (CIs), and bimodal CI stimulation (i.e., the use of a CI in one ear with a HA in the other). The use of two hearing devices, either bilateral HAs, bilateral CIs, or bimodal CI, can lead to improved performance (i.e., a binaural advantage) compared with the use of just one device (Dunn et al., 2005; Kong et al., 2005; Litovsky et al., 2006a; Ahlstrom et al., 2009; Dorman and Gifford, 2010). Some of the benefits include improved word recognition, speech perception in noise, and localization abilities. However, while many hearing device users experience a binaural advantage, others experience no benefit or show worse performance (i.e., binaural interference) with the use of two hearing devices compared to the better ear alone (Arkebauer et al., 1971; Jerger et al., 1961; Carter et al., 2001; Ching et al., 2007; Litovsky et al., 2006b; Reiss et al., 2016).

How might binaural interference occur? In normal-hearing (NH) listeners, the two ears provide essentially matched spectral information. In addition, under dichotic headphone playback, NH adults typically only fuse tones that evoke pitches differing by less than 0.1–0.2 octaves between the ears (van den Brink, 1976; Reiss et al., 2017). In contrast, many hearing-impaired adults experience abnormally broad binaural pitch fusion, in which dichotic stimuli that evoke pitches differing by as much as 3–4 octaves are fused; this phenomenon occurs in bimodal CI users, as well as bilateral HA and bilateral CI users (Reiss et al., 2014; Reiss et al., 2017; 2018). Further, fusion often leads to averaging of the original pitches into an entirely new pitch (Reiss et al., 2014; Oh and Reiss, 2017). Broad fusion can lead to the averaging of mismatched spectral information between the ears, especially when there are interaural mismatches in spectral representations due to dead regions within the cochlea or to hearing device programming. For instance, broad fusion appears to be linked to binaural interference for vowel perception in CI and HA users (Reiss et al., 2016). Additional recent findings suggest that broad fusion is associated with greater difficulty in understanding speech in the presence of competing talkers, presumably due to fusion and blending of speech from multiple talkers (Oh et al., 2018). Thus, broad fusion can lead to both binaural interference for speech in quiet and poorer abilities to understand speech in background noise.

Little is known about binaural fusion in either NH children or children who use HAs and/or CIs. Studies of visual and multimodal perception suggest that sensory fusion is still developing in children between 8–14 years of age (Vedamurthy et al., 2007; Gori et al., 2008; Nardini et al., 2010). For instance, one study in children with normal vision revealed that dichoptic integration of different inputs to the two eyes and binocular summation both decrease during development, suggesting that binocular integration is still developing in children up to 14 years of age (Vedamurthy et al., 2007). Thus, binaural fusion as another form of sensory fusion may also be developing in this age range, even in NH children.

In the auditory system, one study measured binaural fusion in children with bilateral CIs, and found the likelihood of binaural fusion for the same-numbered electrodes in the two CIs to be reduced compared to NH children (Steel et al., 2015). However, it should be noted that the same-numbered electrodes are not necessarily matched in cochlear place of stimulation, due to surgical variations in insertion depth (Skinner et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2010; O’Connell et al., 2016). Thus, fusion will not necessarily occur for the same-numbered electrodes due to place mismatches. A more comprehensive measure of fusion is to measure fusion for one electrode with multiple electrodes. When fusion is measured across multiple electrodes, adults with bilateral CIs generally exhibit broad fusion, the fusion of one electrode in one ear with multiple electrodes in the other ear (Kan et al., 2013; Reiss et al., 2018). The difference between children and adults may be due to differences in time of implantation, with most adults implanted late in life after several years of bilateral HA and/or bimodal CI experience. This discrepancy raises the possibility that the hearing device combination(s) experienced during childhood development can affect the development of binaural fusion, and that these effects last through adulthood. Certainly, recent data in adult bilateral HA users show a significant correlation between broad fusion and early age of onset of hearing loss and HA use (Reiss et al., 2017). Hence, variability in binaural fusion in hearing-impaired adults with HAs and CIs may be partially explained by variation in childhood hearing device history – such as whether they grew up normal-hearing and were late-deafened, wore bilateral HAs as children, or became bimodal or bilateral early on.

Another possibility is that binaural fusion is affected by pitch mismatches between ears. Pitch mismatches may arise due to the mismatch of cochlear place of stimulation between same-numbered electrodes (in bilateral CI users), or the mismatch between place of stimulation between an electrode in an implanted ear and the acoustic frequencies allocated to that electrode and played simultaneously to a non-implanted ear (in bimodal CI users). Interaural pitch matching is typically conducted using sequentially presented stimuli, rather than simultaneously presented stimuli as in the binaural fusion task. The subject is asked to indicate which of two stimuli, a reference stimulus or comparison stimulus, was higher in pitch, and the process is repeated with various comparison stimuli to estimate a pitch match. Previously, it was shown pitch may adapt over time to reduce this mismatch in adults who use a Hybrid or electro-acoustic stimulation (EAS) CI, a device that combines CI and HA technology in the same ear, often together with a HA in the opposite ear, for CI recipients with hearing preservation (Reiss et al., 2007; 2013). In contrast, in adult bimodal CI users who use a CI and HA in opposite ears, very little or incomplete pitch adaptation to reduce the mismatch across ears has been observed (Reiss et al., 2015; Tan et al., 2017). Similarly, adult bilateral CI users show some, but incomplete, pitch adaptation (Reiss et al., 2012; Aronoff et al., 2019). Interestingly, binaural fusion range was found to be weakly correlated with the degree of mismatch in interaural pitch and even shifted to reduce the mismatch in some adult bimodal CI users (Reiss et al., 2014), suggesting that binaural fusion range may increase over time to reduce the perception of mismatch, as well as or instead of pitch adapting to reduce mismatch. It may be that across-ear mismatches are more easily resolved by changes in fusion whereas within-ear mismatches may be resolved by pitch changes. However, no such correlation was seen in adult bilateral CI users (Reiss et al., 2018). Little is known about pitch perception in children with bimodal or bilateral CIs.

Another measure of interest is the slope of the interaural pitch match function. The slope or range of the pitch match function can be considered as a measure of interaural pitch discriminability. The slope will be shallower and the range broader if there is more overlap in neural populations being compared across the ears. A broad pitch match range may explain broad binaural pitch fusion. Interaural pitch discriminability may also differ between children and adults, as suggested by previous studies of frequency discrimination. For instance, on tests of frequency modulation detection, thresholds improve over the age range from 6–11 years (Dawes and Bishop, 2008; Moore et al., 2011). Similarly, frequency discrimination has also been shown improve over this age range (Moore et al., 2011).

In the current study, binaural pitch fusion and interaural pitch match functions were measured in four groups of children between the ages of 6–11 years: NH, bilateral HA, bimodal CI, and bilateral CI. These four groups were studied and compared in order to assess the effects of early childhood experience with different hearing device combinations on binaural fusion. Findings were also compared with previously collected adult data for each group, in order to assess differences related to development in fusion perception. Within the four pediatric groups, binaural pitch fusion ranges were correlated with subject chronological age, hearing device experience, interaural pitch mismatch, and interaural pitch discriminability to determine the relationships of these factors to binaural fusion.

Materials & Methods

Subjects

These studies were conducted according to the guidelines for the protection of human subjects as set forth by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Oregon Health and Sciences University (OHSU), who also approved the methods employed in this study. A total of 57 children (age range: 6.1 – 11.1 years) participated in the study, with 21 NH children, 9 bilateral HA users, 10 bimodal CI users, and 17 bilateral CI users, designated in subject identification labels as NK, HK, CK, and BK, respectively. Demographic tables for pediatric HA, bimodal CI, and bilateral CI users are shown in Tables 1–3. The tables and subject count do not include 4 HA, 1 bimodal CI, and 2 bilateral CI users who were excluded for various reasons including an inability to understand and follow instructions, failure to complete all study appointments, or withdrawal from the study. Note that one bimodal CI user, CK03, became a bilateral CI user a few years later and was also tested as a bilateral CI subject, BK10; the results of the latter testing as BK10 were excluded from group comparisons, and only included for within-group analyses in the bilateral CI group.

TABLE I.

Demographic information for bilateral hearing aid (HA) pediatric subjects (HK): age, gender, etiology of hearing loss, duration of experience with HAs, daily hours of bilateral HA (BHA) use, HA make and model, use of HA frequency shifting or frequency compression (cutoff frequency and compression ratios provided if present), and reference ear. Numbers separated by semicolon indicate values for the left; right ears if different for the two ears. HL=hearing loss; L=left; R=right.

| Subj. ID | Age (yrs) | Gender | Etiology of HL | Dur. BHA Use (yrs) | Daily HA Use (hrs/day) | HA Model | Freq. shift HA? | Ref. Ear |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HK01 | 9.9 | Male | Unknown | 8.4 | 10 | Oticon Safari 300 BTE Power | No | L |

| HK02 | 8.2 | Male | Unknown | 3.7 | 12 | Oticon Safari 300 BTE Power | No | L |

| HK03 | 6.7 | Male | Unknown | 2.0 | 13 | Oticon Safari 300 BTE Power | No | L |

| HK04 | 6.3 | Male | Unknown | 4.0 | 12 | Phonak Naida IX SP | 3.1 kHz@ 3.6:1 | R |

| HK10 | 9.2 | Male | Unknown | 2.0 | 9 | Oticon Sensei BTE 75 | No | L |

| HK11 | 8.6 | Male | Unknown | 7.7 | 16 | Oticon Sensei Pro BTE 90 | No | R |

| HK12 | 7.5 | Male | Unknown | 7.2 | 14 | Oticon Safari 300 BTE | No | L |

| HK13 | 10.0 | Male | Unknown | 9.8 | 14 | Phonak Naida Q70-SP | 4.7 kHz@1.3:1 | R |

| HK14 | 7.7 | Male | Unknown | 1.7 | 14 | Phonak Sky Q70 M13 | No | L |

| Avg | 8.2 | 5.2 | 12.7 | |||||

| Std | 1.3 | 3.1 | 2.2 |

TABLE III.

Demographic information for bilateral CI pediatric subjects (BK): age, gender, etiology of hearing loss, duration of experience with bilateral HAs before CI, duration of bimodal or CI-only experience before the second CI, duration of bilateral CI (BiCI) experience, daily hours of bilateral CI use, CI internal devices, and reference ear. NR indicates no data collected for that ear. Numbers separated by semicolon indicate values for the left; right ears if different for the two ears. CI internal devices are from Cochlear unless otherwise specified.

| Subj.ID | Age (yrs) | Gender | Etiology of HL | Dur. BHA pre-CI (yrs) | Dur. BM pre-2nd CI (yrs) | Dur. BiCI (yrs) | Daily biCI Use (hrs/day) | CI internal devices | Ref. Ear |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BK01 | 6.6 | Male | Unknown | 0.75 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 12 | CI24RE; CI512 | R |

| BK02 | 9.3 | Female | Genetic | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.8 | 16 | CI24RE; CI512 | L |

| BK03 | 7.7 | Female | Connexin 26 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 13 | CI24RE | R |

| BK04 | 6.1 | Female | EVA; malformed cochlea | 0.25 | 0.5 | 4.7 | 13 | MED-EL SONATAti 100: Standard electrode | R |

| BK05 | 6.5 | Male | Pendred syndrome | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 14 | CI422 | R |

| BK06 | 8.5 | Female | Unknown | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6.9 | 15 | CI24RE | R |

| BK08 | 7.3 | Male | Genetic | 0.25 | 0.0 | 6.2 | 13 | CI512 | L |

| BK09 | 8.6 | Male | Unknown progressive | 1.2 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 12 | CI24RE | R |

| BK10 | 10.0 | Male | Genetic progressive | 2.6 | 4.8 | 1.1 | 13 | CI512; CI422 | L |

| BK11 | 9.1 | Male | Meningitis progressive | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.2 | 13 | CI24RE | R |

| BK12 | 9.2 | Male | Unknown | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 14 | CI512; CI24RE | R |

| BK14 | 8.4 | Male | Connexin 26 progressive | 4.75 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 9 | CI522; CI512 | L |

| BK15 | 7.7 | Female | Myosin 15a progressive | 1.1 | 0.8 | 3.8 | 13 | CI422 | R |

| BK16 | 7.6 | Female | Connexin 26 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 14 | CI24RE | L |

| BK17 | 10.3 | Male | Connexin 26 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 9.3 | 14 | CI24RE | L |

| BK18 | 8.7 | Male | Unknown | 0.5 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 14 | CI24RE | R |

| BK19 | 8.1 | Male | Usher Syndrome Type 1 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 7.2 | 13 | CI512 | R |

| Avg | 8.2 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 4.6 | 13.3 | ||||

| Std | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 1.5 |

All subjects completed a questionnaire prior to testing to obtain information on age, gender, family history of hearing loss, additional impairments, tinnitus, number of ear infections, and music and language background. Hearing-impaired children were also asked about hearing loss history (etiology, onset, duration, and time course of hearing loss), hearing device type and history, and daily hours of hearing device use. Hearing loss history, hearing device history, and audiometric data were also collected from OHSU medical records for OHSU patients or obtained from audiology service providers for non-OHSU patients. In addition, to guide selection of images used to keep children engaged during the experiment, children were asked about favorite toys, games, movies, pets, sports, and other hobbies.

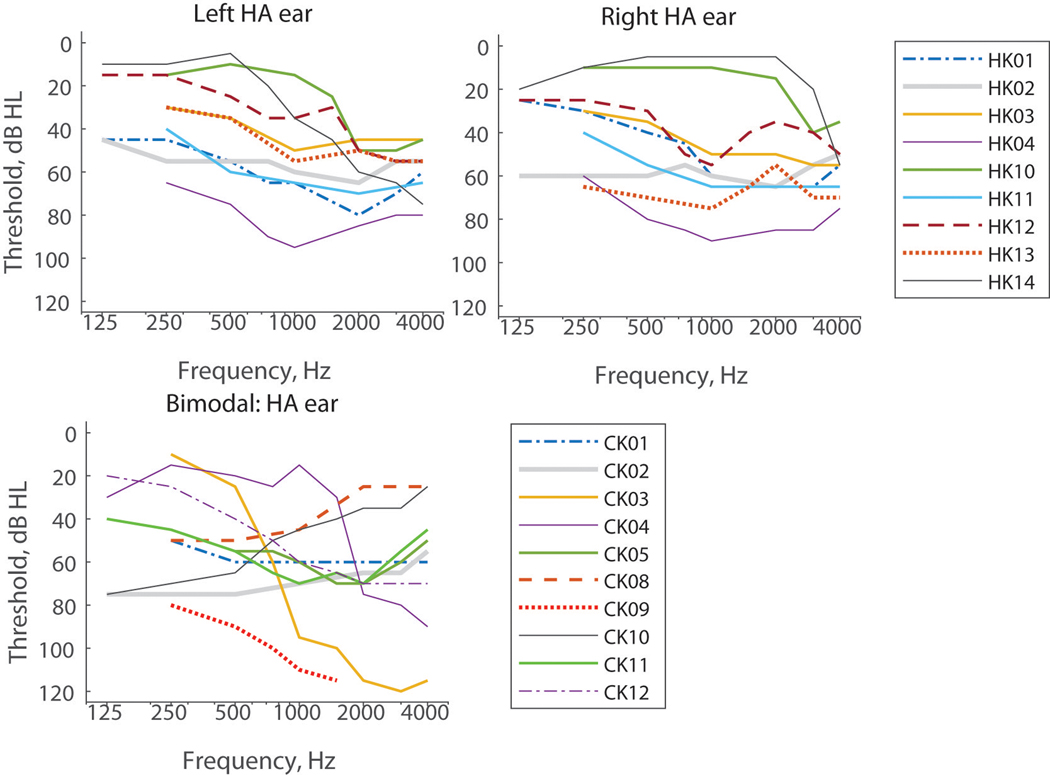

The NH children were all confirmed to have audiometric thresholds ≤ 20 dB HL from 250–4000 Hz and consisted of 13 males and 8 females with an average age of 8.3 years (standard deviation = 1.1 years). The hearing-impaired children all had at least one year of experience with their current combination of hearing devices; audiograms are shown in Figure 1. Tables 1, 2, and 3 show the ages, gender, etiology of hearing loss, duration of hearing loss, duration of use of each hearing device, daily hours of use of the current devices, device models, and reference ears for the bilateral HA, bimodal CI, and bilateral CI groups, respectively. Group average ages were 8.2 ± 1.3 years, 8.5 ±1.6 years, and 8.2 ± 1.2 years for the bilateral HA, bimodal CI, and bilateral CI group (without BK10), respectively; a one-way ANOVA showed no significant differences in age across the four pediatric subject groups (F(3,54)=0.22; p=0.88). The use of frequency-shifting HAs and their parameters if applicable are also indicated for bilateral HA and bimodal CI subjects in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Audiograms for individual bilateral HA (top row) and bimodal CI (bottom left) subjects. (color online)

TABLE II.

Demographic information for bimodal cochlear implant (CI) pediatric subjects (CK): subject age, gender, etiology of hearing loss, duration of experience with bilateral HAs before CI, duration of CI experience, daily hours of listening in bimodal mode (BM; both CI and HA), HA make and model: CI internal device, use of frequency shifting in the HA ear (cutoff frequency and compression ratios provided if present), and reference ear. NR indicates no data collected for that ear. CA=Contour Advance. AB=Advanced Bionics.

| Subj. ID | Age (yrs) | Gender | Etiology of HL | Dur. BHA pre-CI (yrs) | Dur. CI (yrs) | Daily BM use (hrs/day) | HA model; CI internal device | Freq. shift HA? | Ref. (CI) Ear |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK01 | 9.1 | Male | Pendred syndrome | 5.9 | 3.0 | 14 | Phonak Naida V-SP; Cochlear CI512 | No | R |

| CK02 | 8.8 | Female | Unknown | 1.3 | 7.1 | 12 | Widex Mind 440 M4–19; Cochlear CI24RE | No | L |

| CK03 | 6.6 | Male | Genetic progressive | 2.6 | 2.5 | 12 | Widex Inteo; Cochlear CI512 | No | R |

| CK04 | 8.6 | Female | Unknown | 1.0 | 2.4 | 13 | Phonak Ambra M H2O; Cochlear CI422 | 2.7 kHz@4:1 | R |

| CK05 | 6.8 | Female | Connexin 26 | 2.0 | 4.6 | 13 | Widex Inteo IN-19; Cochlear CI512 | No | L |

| CK08 | 11.1 | Male | Unknown progressive | 4.6 | 5.5 | 14 | Phonak Sky Q70-UP; Cochlear CI24RE | 7 kHz@1.5:1 | R |

| CK09 | 8.7 | Female | Connexin 26 | 1.3 | 7.0 | 0 | Phonak Naida; CI512 | NR | R |

| CK10 | 7.3 | Female | Waarden-burg syndrome type 2 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 12 | Phonak V70-P; Med-El Concert: Standard electrode | No | L |

| CK11 | 7.2 | Female | Unknown | 1.0 | 5.6 | 12 | Oticon Sensei Pro BTE 90; AB HiFocus MS | No | R |

| CK12 | 10.8 | Male | Unknown progressive | 4.2 | 6.3 | 13 | Oticon Sensei Pro; AB HiFocus 1J | No | R |

| Avg | 8.5 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 11.5 | |||||

| Std | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 4.1 |

Of the bimodal CI users, seven subjects used Cochlear devices, two subjects used Advanced Bionics devices, and one subject used a MED-EL device. Of the bilateral CI users, sixteen used Cochlear devices, and one used a MED-EL device(s). All CI subjects used a variation of the fixed-rate continuous interleaved sampling strategy (CIS). MED-EL device users differed in that they also used a Fine Structure Processing (FSP) strategy for apical electrodes; hence, MED-EL device users were only tested on basal electrodes that used the CIS envelope-based strategy.

Data collected from children in this study were compared with data collected and published previously from adult subjects from equivalent categories (Reiss et al., 2014; 2017; 2018; supplementary tables 1–3). The adult subjects ranged in age of onset of hearing loss, from pre-lingual to adult onsets (Reiss et al., 2014; 2017; 2018). All subjects were paid for their time spent in the study, and travel and overnight accommodations were provided for subjects from out of town.

General Procedures

All procedures and experiments were conducted in a double-walled, sound attenuated booth. Prior to testing, subjects completed an audiometric evaluation. For NH, HA, and bimodal CI subjects with acoustic hearing, this included otoscopy, tympanometry, and pure tone air and bone conduction thresholds. For HA and bimodal CI subjects, real ear aided measurements were obtained from the hearing aid ear(s) and compared to Desired Sensation Level (DSL) 5.0a Child prescriptive targets using an Audioscan Axiom in order to measure the amount of amplification provided by the HAs. For bimodal and bilateral CI subjects, aided hearing thresholds for CI ear(s) were obtained using sound field presentation of narrowband noise. For all hearing-impaired subjects, hearing device programming was downloaded, printed, and included in each subject’s file in order to document device parameters (e.g., CI MAPs and frequency lowering/compression parameters for comparison with pitch match results).

For experiments, stimuli were presented via computer to control electric and acoustic stimulus presentations. NH and HA subjects were tested using acoustic stimuli under headphones. For bimodal CI subjects, electric stimuli were presented via an experimental CI processor to the implanted ear, and acoustic stimuli via headphone to the opposite ear. For bilateral CI subjects, electric stimuli were presented to both ears. All subjects were tested unaided using headphones and experimental CI processors; no personal HAs or CI processors were used.

Electric stimuli were delivered to the CI using NIC2, RIB2, and BEDCS CI research software for Cochlear, MED-EL, and Advanced Bionics devices, respectively. Hardware consisted of clinical programming pods and L34 research processors for Cochlear, and a National Instruments PCIe-6351 card for MED-EL and Advanced Bionics. Stimuli were synchronized across ears for bimodal and bilateral CI subjects using triggering via the trigger input feature of the programming pods for Cochlear and the PCIe-6351 card for MED-EL and Advanced Bionics. Pulse widths were those used in the subjects’ clinical programs. For Cochlear users, pulse widths were 25 μsec, except for bilateral CI subjects BK10, BK14, and CK09 who used 37 μsec pulse widths for the right CI. For the two MED-El subjects, a 29.58 μsec pulse width was used for CK10 and a range of pulse widths from 26.67–53.33 μsec and 27.50–47.50 μsec for different electrodes in the left and right ear of BK04, respectively. For the Advanced Bionics users, pulse widths of 32.32 μsec were used. All CI subjects were stimulated using monopolar stimulation with a pulse rate of 1,200 pps/electrode to minimize the effects of any temporal cues on pitch; all subjects and electrodes tested used clinical pulse rates of 900 pps or higher, also above this rate limit.

Acoustic stimuli were generated at a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz with Matlab (version R2010b), generated by an ESI Juli sound card (for NH, HA, and bimodal CI subjects with Cochlear devices) or the PCIe-6351 card (for bimodal CI subjects with Med-El or Advanced Bionics devices), TDT PA5 digital attenuator and HB7 headphone buffer, and presented over Sennheiser HD-25 headphones. Each headphone’s frequency response was equalized using calibration measurements obtained with a Brüel & Kjær sound level meter with a 1-inch microphone in an artificial ear. All acoustic stimuli consisted of sinusoidal pure tones with 10-ms raised-cosine onset/offset ramps. For acoustic loudness balancing, 300-msec tones at 0.125, 0.175, 0.25, 0.375, 0.5, 0.625, 0.75, 0.875, 1, 2, 3, and 4 kHz were used.

All stimuli were loudness balanced using a method of adjustment. First, the level of the acoustic or electric stimulation for each stimulus was initialized to a comfortable level on a visual loudness scale. For children, a simplified visual loudness scale was provided with three options: “too soft”, “good”, and “too loud”. For hearing-impaired acoustic ears, tones that could not be presented loud enough to reach a “good” level due to too much hearing loss at those frequencies were excluded; this determined the upper limits of the loudness balanced frequency range of the acoustic ear. Second, once levels were initialized, then all stimuli were sequentially loudness balanced across stimuli both within and across ears, by presenting each pair of stimuli sequentially and adjusting levels until the two stimuli were judged to be similar in loudness. For acoustic stimuli, interpolation (on a dB scale) was then used to determine appropriate levels for all usable tone frequencies within the 125–4000 Hz frequency range used for testing.

After the loudness balancing procedure, the same interface was used to assess understanding of pitch. Two stimuli with large pitch differences (such as acoustic tones with a low and high pitch, e.g. 125 Hz versus the 1000 Hz, or apical and basal CI electrodes) were presented sequentially, and the child asked to indicate verbally if the first or second stimulus was higher in pitch, and verbal feedback was given by the experimenter. A significant number of younger children, including NH children, did not understand the concept of pitch initially. In those cases, the concept was taught using various methods including a toy keyboard, ecological examples (e.g. trombone versus flute, cow “moo” versus bird, man’s voice versus woman’s voice), and musical activities (such as those linking movement to pitch). Once conceptual understanding was verified, practice pitch matching tests were conducted within ears, with feedback, to further train and assess pitch ranking abilities.

Listeners performed dichotic fusion range and interaural pitch matching measurements using the same reference ear and stimulus. For bimodal CI subjects, the reference ear was the CI ear. For other subjects, if pitch discrimination was symmetric across ears, the reference ear was chosen randomly; otherwise, the ear with worse pitch discrimination was chosen as the reference ear. For NH and HA subjects, the reference stimulus was a 1.6 kHz tone (except for HK01 who was tested with a .5 kHz reference stimulus). This tone frequency was used because it is above the binaural beat frequency detection limit for NH listeners (Perrott and Nelson, 1969), to avoid binaural beats adding difficulty to the task; HK01 was verified as not hearing binaural beats at 0.5 kHz using an adaptive beat detection procedure (Reiss et al., 2017; Grose and Mamo, 2010). For bimodal and bilateral CI subjects using Cochlear devices, the reference stimulus was electrode 18 (frequency-to-electrode allocation range: 688–813 Hz), with the exception of CK01 who was tested with electrode 22 (frequency-to-electrode allocation range: 188–313 Hz) due to a limited acoustic hearing range. For CI subjects using MED-EL and Advanced Bionics devices, the reference stimulus was electrode 5 which had similar frequency-to-electrode allocations and were not among the apical four electrodes used in MED-EL’s fine-structure strategy (MED-EL frequency range: 787–1144 or 935–1383 Hz; Advanced Bionics frequency range: 697–828 Hz). Electrode 18/5 was selected as an electrode that would be likely to yield a successful pitch match for both bimodal and bilateral CI subjects, i.e. pitch match within the acoustic frequency range for bimodal CI users (below 1500 Hz) and within the electrode range for bilateral CI users (at least 4 electrodes away from the most apical electrode 22/1). While these frequency-to-electrode allocations differ from the 1600 Hz used in the acoustic tone experiments, it should be noted that CIs are often inserted only to the ~1000 Hz place and up in the cochlea (Lee et al., 2010; Greenwood, 1990; Stakhovskaya et al., 2007), so that electrode 18/5 in reality is likely to be stimulating at or above the 1600 Hz cochlear place.

Subjects were given practice trials with feedback before each procedure. Within each run of the fusion range or pitch matching task, the reference stimulus was fixed, and the comparison stimulus varied in pseudorandom sequence from trial-to-trial for a total of 6 repeat trials for each comparison stimulus per run (Reiss et al., 2012). Comparison stimuli in the contralateral ear were acoustic tones for NH, bilateral HA, and bimodal CI subjects, and electrodes in the contralateral CI for bilateral CI subjects. For bilateral CI subjects with MED-El, all 10–12 electrodes were tested. For bilateral CI subjects with Cochlear devices, which have 22 electrodes spaced at less than half the spacing of MED-EL electrodes, only even-numbered electrodes were tested in order to limit the number of trials and make data collection time feasible in young children. At least two repeat runs were performed for each reference electrode and procedure.

In addition, as these were young children, a variety of methods were used to keep children engaged and on task. First, successful completion of each trial was followed by the appearance of a third screen with an image in a 5×4 grid, with one random piece of the image revealed incrementally after each trial, so that the full image was displayed after every 20 trials. Images were chosen based on the child’s interests as determined in the initial questionnaire. Second, an experimenter was always in the booth to monitor the child, help the child to stay engaged, provide small rewards such as stickers at intervals, and determine based on behavioral cues when a break was needed. Third, successful completion of each full procedure was followed by a larger reward such as a small toy or tickets to accumulate for larger prizes.

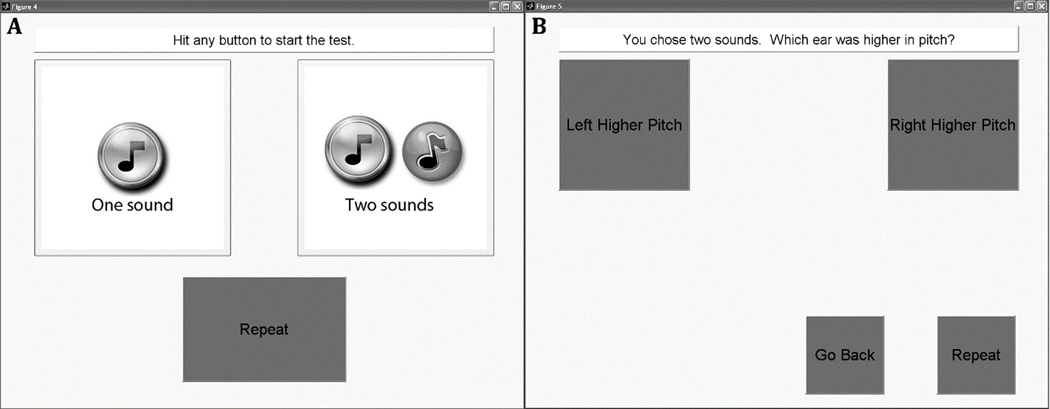

Dichotic Fusion Range Measurements

The dichotic fusion range, or the range of comparison stimuli that were fused with the reference stimulus, was measured using a single interval procedure. For each trial, the comparison stimulus was presented simultaneously with the reference stimulus over a duration of 1,500 msec. Subjects were asked to indicate on a touchscreen display whether they heard one or two sounds, by selecting one of two response buttons with one or two musical notes, respectively (Figure 2A). If they heard only one sound, regardless of whether it was heard only in one ear or both ears, they were instructed to choose the “One Sound” button. If they heard different sounds in each ear, then they were instructed to choose the “Two Sounds” button. If the “Two Sounds” button was selected, then another screen appeared with two response buttons titled “Left Higher Pitch” and “Right Higher Pitch” (Figure 2B). Subjects were asked to choose which ear they heard the higher pitched sound of the two sounds, by selecting the appropriate button. If subjects couldn’t tell which was higher in pitch, they were instructed to guess and pick one of the two ears randomly. From this screen, subjects could also choose to, “Go Back” if they changed their mind and wanted to choose “One Sound”. This second screen was provided as a check of whether the subject really heard two sounds and that they understood the task (for pitches that are sufficiently different, subjects should be able to reliably identify which ear had the higher pitch). A “Repeat” button was also provided on both screens to allow subjects to listen to the stimuli again as often as needed.

Figure 2.

Screenshots of the touch screen choices for the fusion range test. A. The first screen of the pediatric fusion range test. B. The second screen of the pediatric fusion range test. Subjects would see this screen only if they chose “Two sounds” in the first screen.

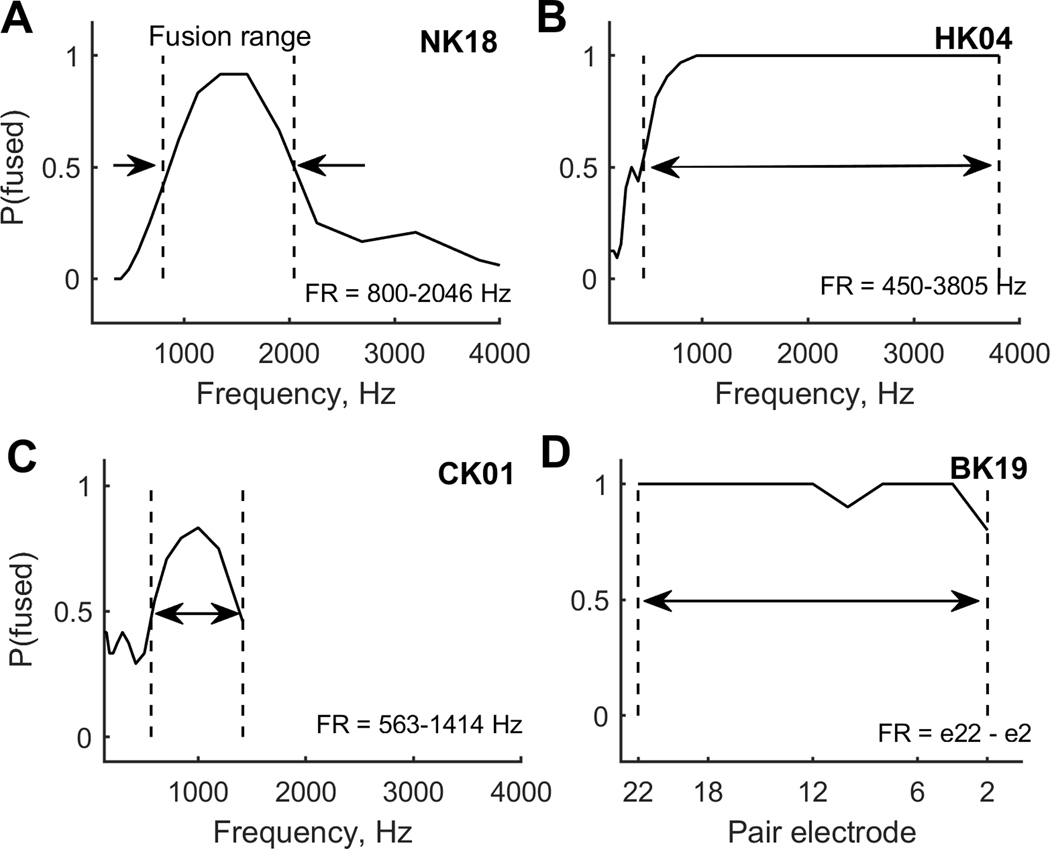

For analysis, responses were assigned fusion values as follows: “Left Higher Pitch” or “Right Higher Pitch”=0, and “One Sound”=1. Each point on the fusion function was calculated as these fusion values averaged over all trials for each contralateral reference stimulus, and indicates the proportion of trials that the reference stimulus was fused with that contralateral stimulus. For each fusion function (example curves shown in Fig. 3), the fusion range was defined as the frequency or electrode range between the 50% points (P(fused)=0.5; demarcated by dashed vertical lines). The fusion range is the stimulus range (acoustic tone frequencies or CI electrodes) in one ear that fused with a single stimulus location (acoustic tone frequency or CI electrode) in the other ear.

Figure 3.

Example fusion functions for representative children in each of the four subject groups. Dashed vertical lines indicate the rising and falling 0.5 points on the curves. A. NH child. B. Child with bilateral HAs. C. Child wtih bimodal CI. D. Child wtih bilateral CIs. The curves indicate the proportion that each contralateral stimulus was fused with the reference stimulus. The fusion range is defined as the range of contralateral stimuli that fused with the reference stimulus more than 50% of the time.

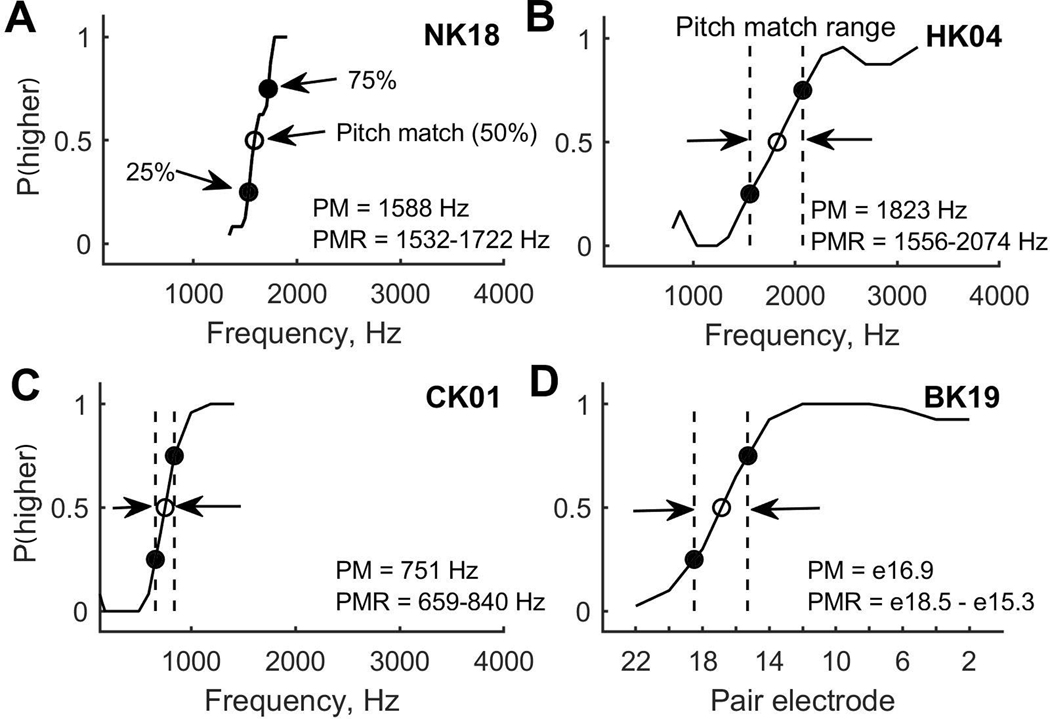

Interaural Pitch Matching

Prior to testing, subjects were trained using a within-ear pitch ranking test with feedback. Interaural pitch matches were then obtained using a two-interval, two-alternative forced-choice constant stimulus procedure. One interval contained a reference stimulus delivered to the reference ear. The other interval contained a comparison stimulus delivered to the contralateral ear; stimuli were either acoustic or electric, depending on subject group. The stimuli were each 500 msec in duration and separated by a 500-msec interstimulus interval, with interval order randomized. In each trial, the subject was asked to indicate on a touchscreen display which interval had the higher pitch.

Pitch match psychometric functions were computed as the averaged responses to the range of comparison stimuli (examples shown as solid curves in Figure 4). When functions showed clear bracketing of the pitch match with y-values increasing from 0 to 1, pitch match centers were computed as the 50% points on the functions (P(higher)=0.5; open circles), and pitch match ranges were computed as the distance between the 25% and 75% points (P(higher) =0.25 and 0.75; filled circles) in the psychometric function. This pitch match range is used as a measure of slope, with narrow ranges indicating steep slopes and broad ranges indicating shallow slopes. Most subjects were able to pitch match the reference stimuli (acoustic tones or CI electrodes) to the comparison stimuli in the contralateral ear. However, several pediatric subjects, particularly in the bilateral CI group, were not able to pitch match at all, as indicated by mostly flat pitch match functions. Ability to pitch match was defined as the ability to bracket the reference stimulus pitch within the range of comparison stimuli (Reiss et al., 2007). Specifically, if the pitch match function did not reach 0 or did not reach 1, this indicated an inability to consistently rank a comparison stimulus as lower and higher in pitch than the reference, respectively, and thus an inability to pitch match. In these cases, pitch match ranges were set to the maximum range of the stimuli, and pitch match centers were not computed and thus excluded.

Figure 4.

Example pitch match psychometric functions for representative children in each of the four subject groups. A. NH child. B. Child with bilateral HAs. C. Child with bimodal CI. D. Child with bilateral CIs. Pitch match functions that indicate the proportion that the contralateral stimulus was higher in pitch than the reference stimulus. The pitch match is defined as the 50% point (open circle), and the pitch range is defined as the difference between the 25% and 75% points (filled circles); see arrows in A. Vertical lines show pitch match range in B-D (not shown in A).

In order to compare pitch match and fusion results across CI manufacturers and devices with different inter-electrode distances, fusion ranges and pitch match ranges estimated for bilateral CI subjects were converted from units of electrodes to units of mm (measured between the centers of adjacent electrodes) using the following inter-electrode distances based on physical electrode spacing: 2.4 mm for the MED-EL Standard array, 0.75 mm for Cochlear CI24M, and variable distances between 0.4–0.81 for Cochlear CI24R/CI24RE/CI512 and between 0.85–0.95 for Cochlear CI422 arrays. In order to avoid creating artificial differences in fusion ranges in bilateral CI subjects with different internal electrode arrays and inter-electrode spacing, maximum fusion ranges and pitch match ranges were defined to be 10.92 millimeters (the length of the shortest array in the data set) for all subjects.

In order to compare results from the bilateral CI group, in units of mm, to the results from other groups, the scale in mm was approximated to octaves based on the observed mostly linear relationship of cochlear place to log frequency above the 1000 Hz cochlear place for both the organ of Corti and spiral ganglion maps (~1 octave per 5 mm; Greenwood, 1990; Stakhovskaya et al., 2007).

Results

Example fusion functions from representative subjects in each of the four pediatric subject groups are shown in the panels in Figure 3. Each fusion function shows the proportion of trials that a reference tone was fused with a contralateral pair stimulus, as a function of pair stimulus frequency or electrode. The stimuli used depended on the subject’s hearing device combination. For NH and bilateral HA subjects, the fusion function is shown for a reference tone at 1600 Hz as a function of contralateral tone frequency (Fig. 3A–B). For bimodal CI subjects, the fusion function is shown for reference electrode 18/5 (Electrode 18 for Cochlear or electrode 5 for MED-EL or AB) as a function of contralateral tone frequency (Fig. 3C). For bilateral CI subjects, the fusion function is shown for reference electrode 18/5 as a function of contralateral electrode number (Fig. 3D). Generally, but not always, the fusion functions showed a single peak over which fusion occurred, centered on the reference frequency or electrode (e.g. Fig. 3A).

Clear lower and upper 50% points are seen for the NH child (NK; Fig. 3A), but not the other groups, in which floor- and ceiling-like effects are observed due to the combination of abnormally broad fusion and limitations on the range of stimuli that could be tested. These examples illustrate the broader fusion ranges typically observed in children in the hearing-impaired groups, particularly the bilateral HA (HK; Fig. 3B) and the bilateral CI (BK; Fig. 3D) groups.

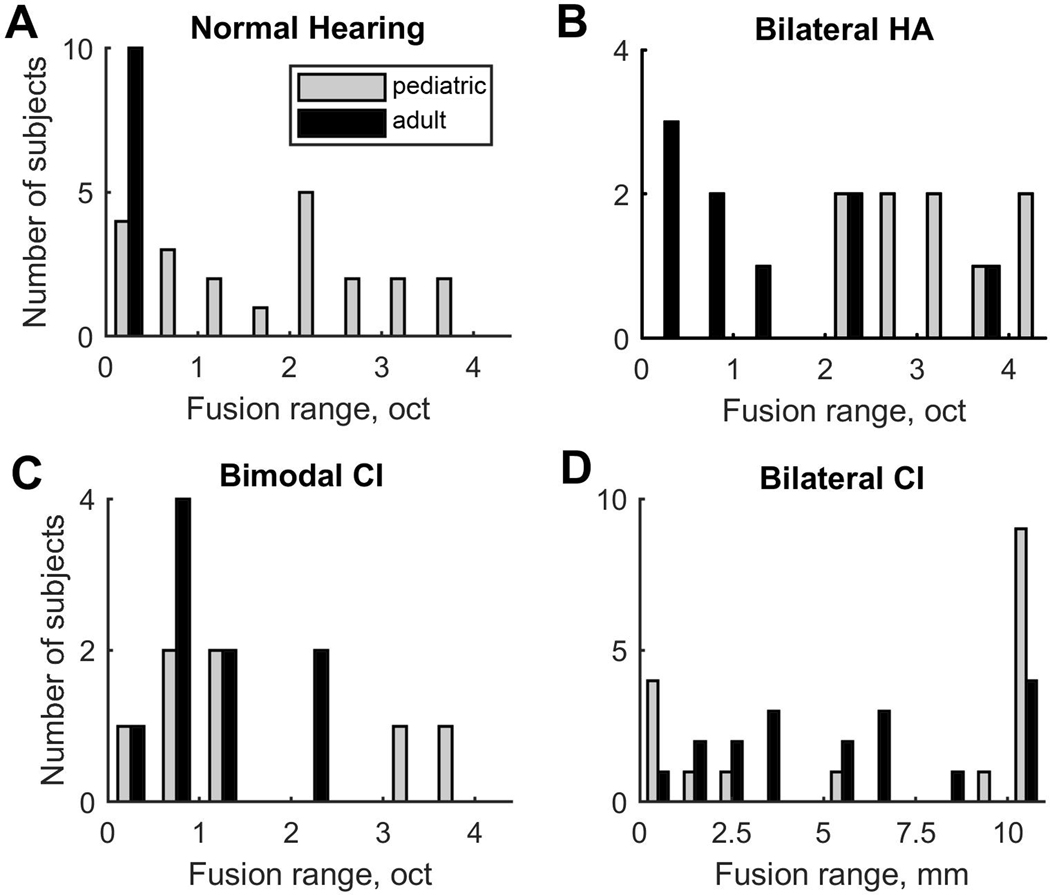

Figure 5 shows distributions in fusion ranges for all pediatric and adult subjects, grouped in panels by hearing device combination. Evident here are differences in distributions between children and adults in each group, and across groups. Of all subject groups, the adult NH group showed the least variation, with narrow fusion ranges clustered below 0.5 octaves (black bars, Fig. 5A); this contrasts with the greater variation seen in the pediatric NH group (gray bars, Fig. 5A). Another group that showed little variation was the pediatric HA group, which showed uniformly broad fusion, clustering above 2 octaves (gray bars, Fig. 5B), which contrasts with the greater variation seen in HA adults (black bars, Fig. 5B). This is striking given many of these children had good sequential pitch discrimination, i.e. were able to pitch match stimuli across ears over a much smaller range, as can be seen for subject HK04 (compare the fusion range in Fig. 3B with the pitch match range in Fig. 4B). Greater variability in fusion range was observed in all of the hearing-impaired adult groups (HA, bimodal CI, and bilateral CI) and in all of the pediatric groups other than the pediatric HA group. Interestingly, in the pediatric bilateral CI group, a bimodal distribution with two peaks is apparent; several children fused the entire range of comparison electrodes, whereas other children fused few or no electrodes (light gray bars, Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Distributions of individual fusion ranges by group. Pediatric groups are represented by the light gray bars and adults are represented by the dark gray bars.

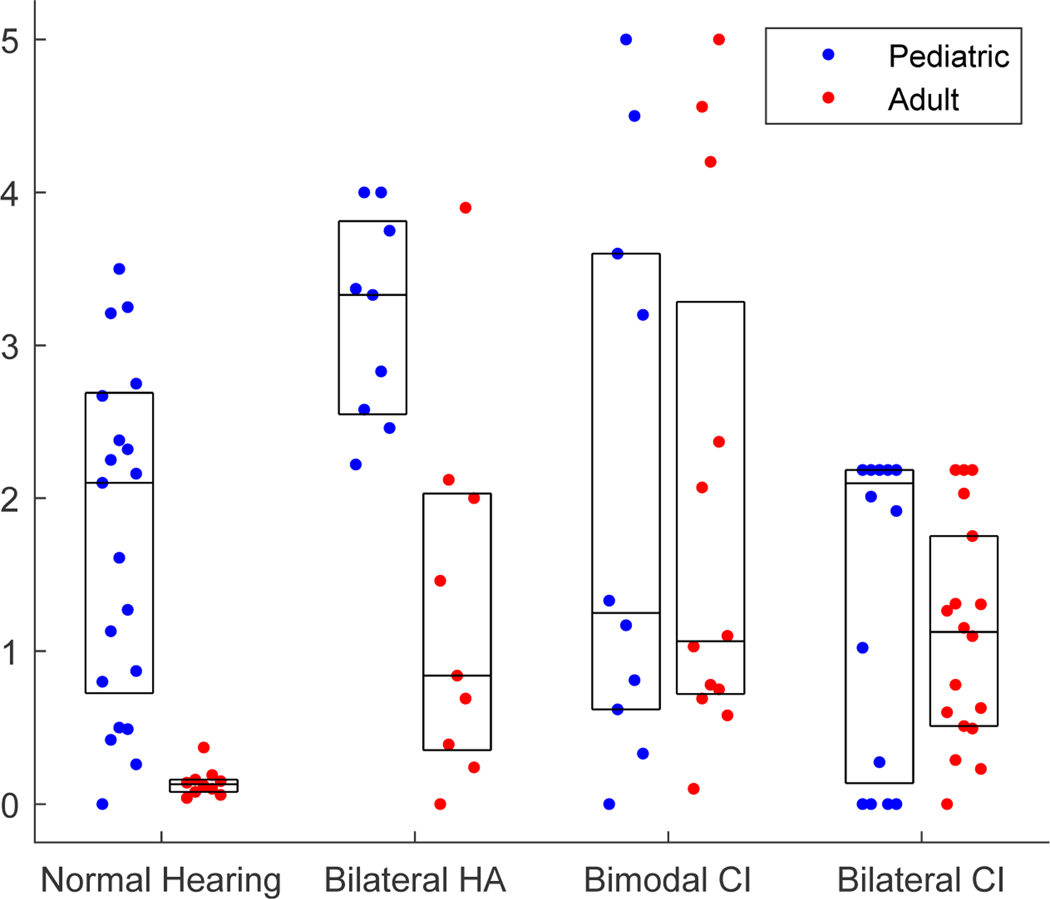

Figure 6 shows the individual data for the pediatric groups (gray dots; blue in color online), along with data collected from the corresponding adult groups (black dots; red in color online) using the same reference stimuli and procedures; summary group medians are shown as horizontal lines and the middle 50% of the fusion range data are outlined by boxes. The fusion range is plotted in octaves for the NH, bilateral HA, and bimodal CI groups on the primary Y axis at left, and in millimeters for the bilateral CI group on the secondary Y axis at right; to facilitate comparison, the millimeter scale on the right axis is approximated to match the octave scale on the left axis at a ratio of 5 mm/octave observed for both the organ of Corti and spiral ganglion for 1000 Hz and up (Greenwood, 1990; Stakhovskaya et al., 2007).

Figure 6.

Summary of group fusion range data for all pediatric subject groups (gray dots; blue in color online), and corresponding adult groups (black dots; red in color online). The scale for NH, bilateral HA, and bimodal CI subjects is in octaves on the primary Y axis at left. For bilateral CI users, the scale is shown in millimeters on the secondary Y axis (right), and scaled at 5 mm/octave for comparison with the other groups (Greenwood, 1990; Stakhovskaya et al., 2007). Boxes represent the interquartile range (50% of the data), whiskers show the range of the data (1.5 times the interquartile range if outliers are shown as individual symbols), and horizontal lines indicate medians. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01

Due to non-normal distributions and non-uniform variance (apparent in Fig. 5), a linear regression model with robust variance estimation was used to evaluate group trends, with hearing device and age group as independent factors and fusion range as the dependent factor. Significant and strong effects were seen both between adult and pediatric groups (F(4,97)=14.81, p<0.0001) and across hearing device combinations (F(6,97)=13.86, p<0.0001), with a significant interaction (F(3,97)=5.26, p=0.0021). These effects can be seen in Figure 6. Posthoc pairwise comparisons were conducted between children and counterpart adult groups with the same hearing device to assess effects of age group (child versus adult), and between pediatric groups with different hearing devices to assess effects of hearing device combination in children. Significant differences were seen for some, but not all, comparisons. First, when pediatric groups were compared with counterpart adult groups, only the NH and bilateral HA groups exhibited significantly broader fusion than the adult counterparts (r=0.71, p<0.0001 and r=0.69, p=0.0036, respectively, two-tailed Wilcoxon rank-sum test), while both the bimodal and bilateral CI groups had similar fusion ranges as their adult counterparts (r=0.014, p=0.95 and r=0.17, p=0.33, respectively). Second, when pediatric groups with different hearing devices were compared, only the bilateral HA group had broader fusion than the other groups, with a significant difference in fusion range compared to the NH and bilateral CI groups (r=0.54, p=0.0033 and r=0.82, p<0.0001, respectively), but not the bimodal CI group. These differences remained significant at p<0.05 even when p-values were multiplied by a Bonferroni correction factor of 10 for 10 multiple comparisons (leading to corrected p-values of p<0.001 and p=0.036 between pediatric and counterpart adult groups with NH and HAs, respectively, and p=0.033 and p<0.001 between pediatric HA versus NH and bilateral CI groups, respectively); the correction did not change the significance of the statistical tests.

Example interaural pitch match functions from representative subjects in each of the four pediatric subject groups are shown in Figure 4. All of the subjects shown were able to complete the task, with clear 25%, 50%, and 75% points in their functions. Similar to binaural fusion range, there are also substantial differences in interaural pitch match functions among the different groups of children. The NH child has the steepest slope, resulting in the narrowest pitch match range (Fig. 4A), and thus best interaural pitch discrimination. The two children with bilateral HAs and bimodal CI both have shallower slopes than the NH child (Fig. 4B and 4C, respectively), and the child with bilateral CIs has the shallowest slope with the widest pitch match range (Fig. 4D), indicating the poorest pitch discrimination ability.

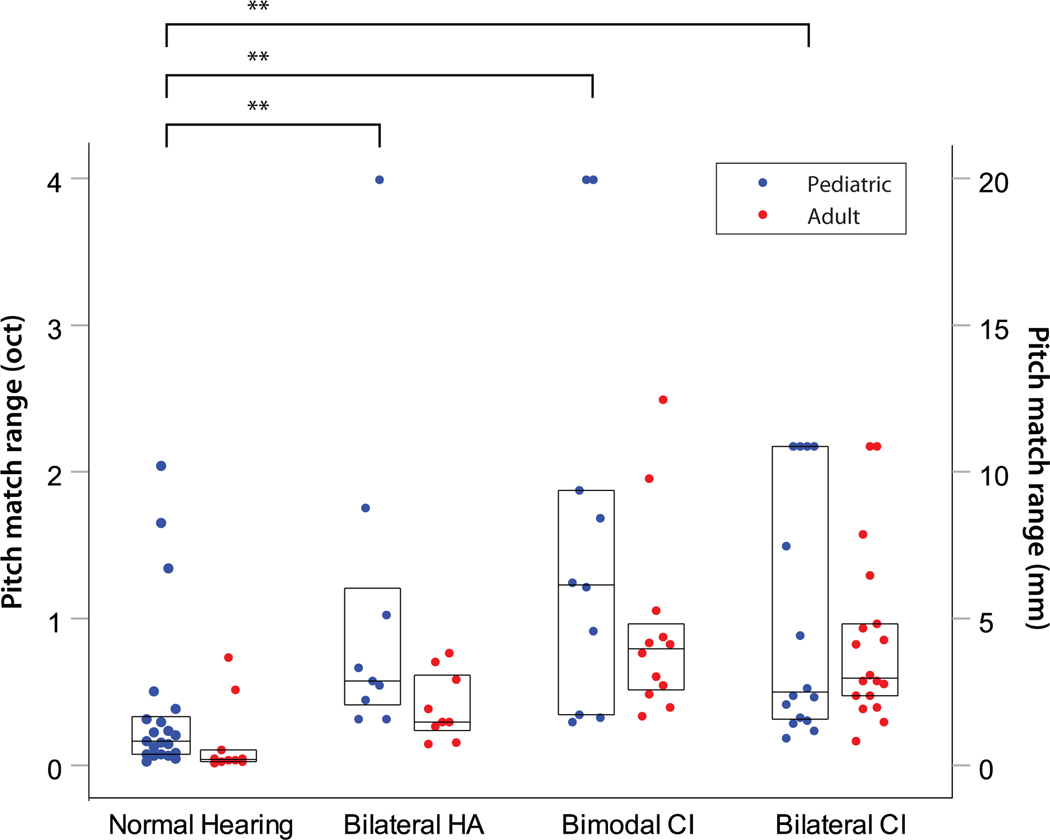

Figure 7 shows the individual data for the pediatric groups (gray dots; blue in color online), along with data collected from the corresponding adult groups (black dots; red in color online); summary group medians are shown as horizontal lines and the middle 50% of the pitch match range data are plotted as boxes. Note that this plot does not include the children who could not complete the pitch match task, including one bilateral HA user, one bimodal CI user, and 6 bilateral CI users. Note also that the pitch match ranges in Figure 7 are generally much smaller for the NH and HA users, at 1 octave or smaller, than the fusion ranges of 2–4 octaves observed for those same groups in Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Summary of group interaural pitch match range data for all pediatric subject groups (gray dots; blue in color online), along with corresponding adult groups (black dots; red in color online). The scale for NH, bilateral HA, and bimodal CI subjects is in octaves on the primary Y axis at left. For bilateral CI users, the scale is shown in millimeters on the secondary Y axis (right). Boxes represent the interquartile range (50% of the data), whiskers show the range of the data (outliers at 1.5–3 and greater than 3 times the interquartile range are shown as circles and stars, respectively), and horizontal lines indicate medians. Asterisks above brackets indicte significance: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01

A linear regression model with robust variance showed no significant effects between adult and pediatric groups (F(4,97)=1.91, p=0.115), but did show highly significant effects across hearing device combinations in the pediatric group (F(6,97)=6.86, p<0.0001). No significant interaction was observed (F(3,97)=0.63, p=0.59). Comparisons across pediatric groups showed that NH children had significantly narrower pitch match ranges than bilateral HA (r=0.55, p=0.0024), bimodal CI (r=0.59, p=0.0011), and bilateral CI children (r=0.57, p=0.0005). No other significant differences were seen.

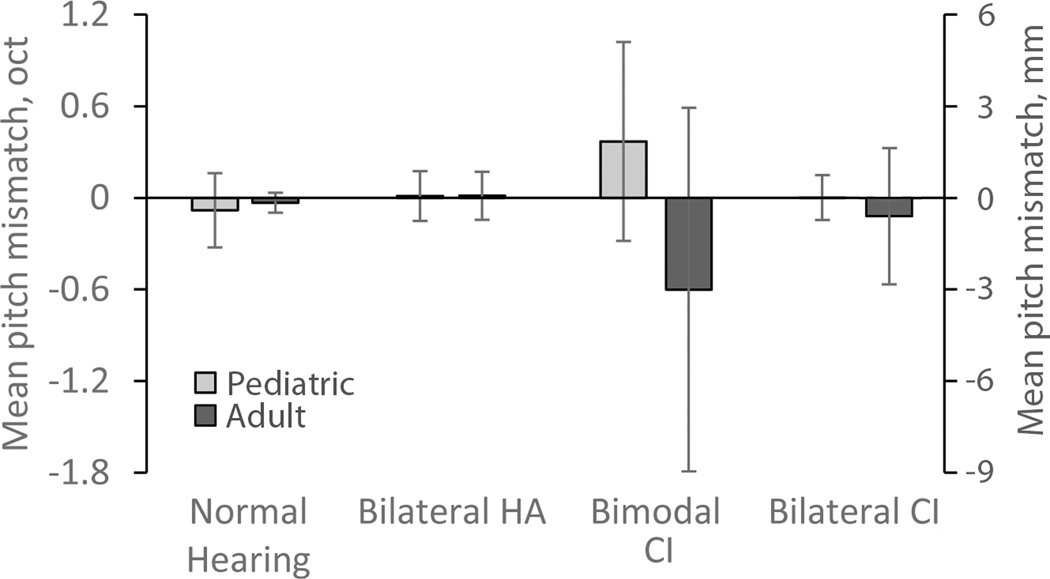

Pitch mismatches were also calculated as the difference between the pitch match and reference frequencies, in octaves. For instance, the NH child shows a pitch match 50% point roughly aligned with the reference frequency of 1600 Hz (Fig. 4A), while the child with bilateral HAs shows an upward shift in the pitch match 50% point relative to the reference frequency (Fig. 4B). These mismatches are summarized in Figure 8, and show generally small mismatches on average for all groups except for the bimodal CI groups. A linear regression model with robust variance did not show significant effects between pediatric and adult groups (F(4,87)=1.84, p=0.13) or across hearing device combinations (F(6,87)=1.50, p=0.19). The interaction between age group and hearing device was not quite significant (F(3,87)=2.45, p=0.069).

Figure 8.

Summary of group mean interaural pitch mismatches for all pediatric subject groups (light gray bars), along with corresponding adult groups (dark gray bars). The scale for NH, bilateral HA, and bimodal CI subjects is in octaves on the primary Y axis at left. For bilateral CI users, the scale is shown in millimeters on the secondary Y axis (right). Error bars represent +/− 1 standard deviations.

Correlation analyses were conducted within each pediatric group to assess whether fusion ranges were related to subject variables of age, durations of HA, bimodal CI, or bilateral CI use, and to pitch mismatch or pitch match range using two-tailed Spearman correlation tests. Correlation results are shown in Table 4. For the NH, bilateral HA, and bimodal CI groups, no significant correlations were seen between fusion range and age, applicable durations of hearing device experience, pitch mismatch, or pitch match range. In addition, bilateral HA and bimodal CI groups showed no correlations of fusion range with average headphone level in the experiment.

Table IV.

Table of correlations of fusion range with various subject- and stimulus-specific variables by subject group. The two-tailed Spearman correlation test was used.

| r | p | |

|---|---|---|

| NH children (NK group) | ||

| Age | −0.32 | 0.16 |

| Pitch match range (oct) | 0.13 | 0.57 |

| Bilateral HA children (HK group) | ||

| Age | −0.03 | 0.93 |

| Pitch match range (oct) | −0.52 | 0.15 |

| Bilateral HA experience (years) | 0.17 | 0.68 |

| Average bilateral low-frequency PTA (dB HL) | 0.49 | 0.18 |

| Bimodal CI children (CK group) | ||

| Age | 0.41 | 0.24 |

| Pitch match range (oct) | 0.07 | 0.84 |

| Bilateral HA experience (years) | −0.25 | 0.49 |

| Bimodal experience (years) | 0.13 | 0.73 |

| Average low-frequency PTA (dB HL) | 0.13 | 0.73 |

| Bilateral CI children (BK group) | ||

| Age | 0.11 | 0.68 |

| Pitch match range (mm) | −0.17 | 0.52 |

| Bilateral HA experience (years) | −0.80 ** | 0.00011 |

| Bimodal experience (years) | −0.57 * | 0.016 |

| Bilateral CI experience (years) | 0.52 * | 0.038 |

| Average low-frequency PTA (dB HL) before second CI | 0.55 * | 0.022 |

Correlation values in bold fact indicate significant results

p<0.05

p <0.01.

No correlations were seen with pitch mismatch (not shown).

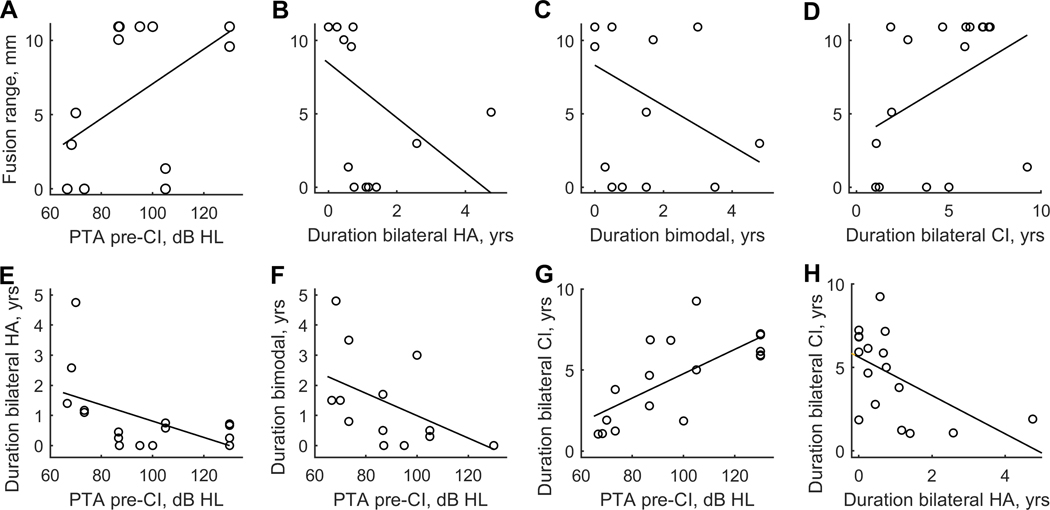

The bilateral CI group, on the other hand, showed significant correlations between fusion range and four variables, as shown in Figure 9. Fusion range was positively correlated with low-frequency pure-tone average (PTA; 250, 500, and 1000 Hz) in the second CI ear before that ear was implanted (Fig. 9A) and duration of bilateral CI experience (Fig. 9D), and negatively correlated with duration of bilateral HA experience (Fig. 9B) and duration of bimodal CI experience (Fig. 9C). In other words, sharp fusion was associated with better pre-operative PTA, longer durations of both bilateral HA and bimodal CI use, and shorter duration of bilateral CI use. However, all four variables were also highly correlated with each other. For instance, duration of bilateral HA and bimodal CI experience are positively correlated (r= 0.58, p=0.015), and duration of bilateral CI experience is negatively correlated with duration of bilateral HA experience (Fig. 9H; r= −0.58, p=0.014) and duration of bimodal CI experience (r= −0.86, p=1.0e-4). Similarly, duration of bilateral HA, bimodal CI, and bilateral CI use are all strongly correlated with average low-frequency PTA with 60%−77% of variance explained (Fig. 9E–G; r= −0.60, p=0.011, r= −0.77, p=0.00036, and r= 0.76, p=0.00036, respectively; Spearman 2-tailed correlation test).

Figure 9.

Scatterplots showing significant correlations between variables in children with bilateral CIs. In the top row, fusion range is plotted as a function of PTA in the second implanted ear before CI (A), duration of bilateral HA use (B), duration of bimodal CI use (C), and duration of bilateral CI use (D). In the bottom row, duration of bilateral HA use is plotted as a function of duration of bimodal CI use (E), and the variables shown in A-D are plotted against each other: durations of bilateral HA use, bimodal CI use, and bilateral CI use are plotted as a function of PTA (F-H).

Two-tailed Spearman correlation analyses were also used to determine whether pitch match ranges were associated with age or applicable durations of hearing device experience. No significant correlations were discovered for any subject group, as shown in Table 5.

Table V.

Table of correlations of pitch match ranges with various subject-specific variables by group. The two-tailed Spearman correlation test was used.

| r | p | |

|---|---|---|

| NH children (NK group) | ||

| Age | 0.24 | 0.30 |

| Bilateral HA children (HK group) | ||

| Age | 0.48 | 0.19 |

| Bilateral HA experience (years) | 0.50 | 0.17 |

| Average bilateral low-frequency PTA (dB HL) | −0.03 | 0.93 |

| Bimodal CI children (CK group) | ||

| Age | −0.05 | 0.89 |

| Bilateral HA experience (years) | −0.55 | 0.098 |

| Bimodal experience (years) | −0.30 | 0.40 |

| Average low-frequency PTA (dB HL) | 0.35 | 0.32 |

| Bilateral CI children (BK group) | ||

| Age | −0.22 | 0.39 |

| Bilateral HA experience (years) | 0.10 | 0.71 |

| Bimodal experience (years) | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| Bilateral CI experience (years) | −0.24 | 0.36 |

| Average low-frequency PTA (dB HL) before second CI | −0.38 | 0.13 |

No values are bolded, because none were significant

In addition, pediatric bilateral HA and bimodal CI groups were evaluated for an effect of frequency-shifting HA use (indicated in Tables 1 and 2, respectively) on these measures. Fisher’s two-tailed exact test showed no significant relationship with frequency-shifting HA use on fusion range (criterion: 1.8 octaves), pitch match range (criterion: 0.4 octaves), or pitch mismatches (criterion: 0.05 octaves). However, analysis of individual data shows that only one subject, CK04, had strong compression (4:1 compression starting at 2.7 kHz) near the frequency range tested. Interestingly, this child had the largest pitch mismatch (1.5 octaves) of the pediatric bimodal CI group. Only one other child, CK02, had pitch mismatch greater than 1 octave (1.3 octaves), while the other six children had pitch mismatches smaller than 0.13 octaves.

Discussion

This is the first study to systematically measure binaural pitch fusion and interaural pitch matches in children with both normal-hearing and with hearing loss, and compare them with adults using the same experimental procedures. Overall, the study reveals some interesting differences between children and adults, and between different groups of children, depending on device combination and history.

Differences in Binaural Fusion Between Children and Adults, and Across Hearing Device Groups

Comparisons across hearing device groups showed that children with bilateral HAs had significantly broader binaural pitch fusion ranges than all of the other subject groups; this is apparent not just in the averaged data but also in the low variance and uniformly broad fusion ranges of the individual subject data in the bilateral HA group. Children with bimodal and bilateral CIs, on the other hand, did not have significant differences in fusion range on average from NH children. This suggests that there might be something different about the bilateral HA combination that promotes abnormally broad fusion, especially during childhood development. This interpretation is supported by previous findings in adult HA users of a positive correlation between fusion range and early onset of hearing loss and long durations of bilateral HA use (Reiss et al., 2017).

How might bilateral HA use promote broad fusion? Bilateral HA use, through amplification, provides stimulation at much higher levels than NH individuals experience. This stimulation at higher levels, combined with the loss of outer hair cells and thus fine tuning in the cochlea, results in a chronic spread of excitation in response to everyday stimuli like speech. This broad peripheral tuning may promote broad fusion simply through the greater overlap of distant receptive fields with broad tuning. Alternatively, early experience with broad tuning may alter central auditory processing; chronic spread of excitation over a broad range of frequencies may lead to abnormally high incidence of coincident firing and thus synapse strengthening across mismatched frequency inputs between ears in binaural neurons, or reduced pruning of synapses necessary for refinement of central auditory processing. As a result, the brain may learn different rules for binaural fusion, i.e. which stimuli are associated together in time and should be fused together.

Interestingly, in children with bilateral CIs, a different effect was seen. There was a significant negative correlation between fusion range and duration of bilateral HA and bimodal CI experience before the second CI, as well as a positive correlation with bilateral CI experience. Further, there were significant correlations with PTA of the second implanted ear prior to CI, and all of these variables were also correlated with each other. The correlation between these factors likely arises because individuals with greater residual acoustic hearing are more likely to be implanted later with the first and second CI. In other words, children who start out with more residual hearing are likely to remain bilateral HA users longer, and then bimodal CI users for longer, before becoming bilateral CI users. The data suggest some influence of one or more of these variables on development of fusion, but more data is needed to separate the effects of these correlated variables observed in this sample.

One possible interpretation, from a peripheral standpoint, is that better PTA reflects better neural health, and thus better peripheral resolution and more discrete neural populations stimulated by each CI, leading to less spatial overlap between binaural neural populations and sharper binaural fusion. One might also speculate from the other direction on how auditory experience may affect binaural fusion; since the bilateral HA group had uniformly broad fusion, we can rule out the prior HA experience as having a sharpening effect on fusion in the bilateral CI group. Instead, experience with the bimodal CI combination may promote development of sharp fusion, i.e. exert an effect opposite to that of bilateral HA experience, possibly because the firing patterns differ greatly between electric and acoustic stimulation, reducing the likelihood of coincident firing. Such an effect may also depend on the PTA of the acoustic ear, i.e. children with better PTAs may show a greater benefit from bimodal CI experience. Certainly, other studies have reported on the benefits of bimodal experience with both CI and HA for speech and language development before receiving a second CI. Longer duration of bimodal experience is associated with better acquisition of generative language and nonword repetition scores (Nittrouer et al., 2014; Nittrouer et al., 2009; Davidson et al., 2017). These studies suggest that language development is impaired in children with less exposure to acoustic stimulation, due to the impoverished phonological representations from the spectrally degraded signal received through a CI. It is possible that exposure to acoustic input early in life may benefit both pitch perception and binaural fusion, and that this benefit carries over even if the child transitions to fully electric hearing with a second CI. For instance, early acoustic experience may be essential for refinement of tonotopic maps in the cortex, and may explain why several children with bilateral CIs were unable to perform the pitch matching task.

Note that there was also a significant number of children with bilateral CIs who did not fuse at all, i.e. there was no contralateral electrode that fused with the reference electrode (BK01, BK05, BK09, BK15; shown as four subjects with zero fusion at the leftmost light gray bar in Figure 5D). This is consistent with the findings in a previous study in which half of children with bilateral CIs did not fuse at all (Steel et al., 2015); the lower percentage in this study is likely due to testing of other contralateral electrodes besides the electrode matched in number to account for electrode place mismatches between ears. It is unclear why some children did not fuse any electrodes across ears. These four subjects tended to have better PTAs prior to implantation than those with broad fusion, so it seems unlikely that they had more dead regions that would explain poor fusion. As these children were all Cochlear device users, one possible explanation is that these children had ultra-sharp fusion with a single odd-numbered electrode that was missed because of how fusion was measured, as fusion was only measured with even-numbered comparison electrodes. Future experiments will test such children with denser electrode sampling to check this.

Compared to NH adults, NH children had significantly broader binaural pitch fusion ranges. This suggests that binaural pitch fusion may still be developing in this age range, and is consistent with several previous studies of binaural fusion as well as visual and multisensory fusion. For instance, one study tested children on binaural fusion of speech, using Word Intelligibility by Picture Identification (WIPI) words that were low-pass and high-pass filtered to each ear, respectively, compared to a control condition in which both bands were presented diotically to both ears (Plakke et al., 1981). The percentage of words repeated correctly in the dichotic compared to diotic condition increased as a function of age (4, 6, and 8 years), with the oldest children obtaining equivalent scores in the dichotic and diotic conditions. A significant effect of age on children’s performance on this task was observed up to 12 or 13 years of age (Stollman et al., 2004). Similarly, in studies of visual and multisensory integration, adult-like performance in binocular and cross-modal fusion is not achieved until about 8-to-14 years of age (Vedamurthy et al., 2007; Gori et al., 2008; Nardini et al., 2010).

In NH children, significant variability in binaural pitch fusion ranges was observed. This may be part of natural variation and asynchronies in development of each individual child; other possible reasons for variation include enriched acoustic environments or auditory training that may accelerate the refinement of binaural fusion. Finally, while there was no significant correlation with age, a decreasing trend with age is apparent (r= −0.32, p=0.16, Table 4; Supplementary Figure 1), consistent with the interpretation that binaural fusion is still developing in this age range.

Similarly to NH children, children with HAs had broader fusion than adult HA users. In contrast, children with bimodal and bilateral CIs did not have broader fusion than the equivalent adult groups. This discrepancy of the bimodal and bilateral CI data from the NH and HA data may be due to the abnormal nature of CI stimulation, such as potential promotion of sharp fusion by bimodal CI use as discussed above.

Interaural Pitch Matching Across Groups and Relation to Binaural Fusion

Comparisons across hearing device groups showed that NH children had narrower pitch match ranges compared to other groups, suggesting better pitch discrimination ability across ears, than the hearing-impaired children who are bilateral HA, bimodal CI, or bilateral CI users. Worse interaural pitch matching performance in the hearing-impaired children may be attributable to reduced frequency resolution with hearing loss and with CIs, especially in cases of limited nerve survival.

Only NH children showed significantly poorer performance compared to NH adults, suggesting that pitch perception is still developing in this age range, as in other modalities of perception. No significant differences were found between children and adults for the hearing-impaired groups.

No relationship was seen between fusion range and pitch match performance in any group, consistent with previous findings in adults (Reiss et al., 2017; 2018). This is apparent in the example bilateral HA subject who had a broad fusion range as shown in Figure 3B, despite a narrow pitch matching range as shown in Figure 4B. This supports the interpretation that broad fusion is not attributable to poor pitch discrimination ability under sequential stimulation, but a difficulty, unique to simultaneous stimulation of both ears, in separation of sounds that should not be grouped together.

In general, children and adults who are bimodal CI users had larger pitch mismatches than the other groups, though group differences were not significant. This is likely due to the mismatch between typical CI electrode array insertion depths and the range of frequencies allocated to the speech processor; CI electrode arrays are typically inserted to the 500–1500 Hz cochlear place (Skinner et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2010; O’Connell et al., 2016), while frequency ranges must extend to lower frequencies of 100–200 Hz to capture the frequencies needed for speech perception. Previous studies have shown adaptation to this mismatch in Hybrid or electro-acoustic CI users with acoustic hearing in the CI ear, but less adaptation in bimodal CI users with acoustic hearing in the contralateral ear (Reiss et al., 2007; 2013; 2015); one possible reason for less pitch adaptation in the bimodal CI group is that binaural fusion may also adapt to reduce perception of this mismatch (Reiss et al., 2014).

Overall Implications

The findings overall show that similar to hearing-impaired adults, hearing-impaired children can have broad binaural pitch fusion, especially children with bilateral HAs. Studies in adult HA and bimodal CI users have shown that broad fusion can lead to binaural interference for speech perception of vowel sounds (Reiss et al., 2016), especially if there is a large pitch mismatch across the ears. In addition, a recent study showed that broad fusion predicts difficulties of adults with NH, bilateral HAs, and bimodal CI with speech perception in realistic environments with multiple competing talkers (Oh et al., 2018). Specifically, broad fusion predicts a reduced benefit from voice fundamental frequency differences between target and masker speech. These studies imply that children with broad fusion will experience similar difficulties with binaural interference and speech perception in noise. As NH children also had broader fusion than NH adults, NH children are likely to also have more difficulties with speech perception in noise than adults. Thus, classroom settings with acoustics that minimize background noise will benefit all children, not just those with hearing loss.

Another interesting finding was that children using the bimodal CI configuration demonstrated better fusion ranges than children with bilateral HAs. Two bimodal CI pediatric users performed within NH adult ranges, whereas all bilateral HA children clearly had much elevated fusion ranges than NH listeners. Hence, normal binaural fusion can be achieved with the bimodal CI configuration even though it combines two very different types of inputs, acoustic and electric hearing. The findings raise the interesting possibility that bimodal CI use in particular may help promote normal development of binaural pitch fusion, and the associated advantages for speech perception in noisy multi-talker environments.

One caveat is the small sample size of this study. Some effects, such as differences between groups, may be missed with small samples. Further study is needed with a larger population to rule out other effects, as well as further investigate the factors underlying variation in fusion range in the bimodal and bilateral CI groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.L.H, J.R.F., G.N.S., and L.A.J.R. designed experiments; C.L.H., J.R.F., G.N.S., B.G., M.E., Y.O. and L.A.J.R. conducted experiments; C.L.H. and L.A.J.R. analyzed data and wrote the paper; K.R. provided additional statistical analysis.

We would like to thank Cochlear, MED-EL, and Advanced Bionics for providing equipment and software support for interfacing with the cochlear implant, Ruth Litovsky and her lab for providing templates for a child-friendly experimental software, and Razi Muhammed, Jyotsna Sridharan, and Margo Heston for assistance with programming the software interface. We thank Jay Vacchani, and Pacific University audiology interns Anna-Marie E. Wood, Ashley Sobchuk, Daniel S. Talian, Sara Simmons, Larissa Katrina, Leah Sherwood, and Mary Preston for helping to collect data. We also thank Tim Hullar, Jessica Van Auken, Carrie Lakin, Jessica Middaugh, Jessica Eggleston, Amy Johnson, Jennifer Lane, and Devon Paldi at the OHSU Cochlear Implant Program; Shelby Atwill at Tucker Maxon School; Jill Beck, Karrie Pargman, Susie Jones, and Jenna Hoffman at St. Luke’s Idaho Elks Hearing and Balance; and Clough Shelton at University of Utah and Cache Pitt at Utah State University for help with recruiting subjects. We also thank all the participants –children and their parents, and adults - for their time in participating in the study.

This research was supported by grants R01 DC013307 and P30 DC010755 from the National Institutes of Deafness and Communication Disorders, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Ahlstrom JB, Horwitz AR, and Dubno JR (2009) Spatial benefit of bilateral hearing aids. Ear Hear. 30:203–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkebauer HJ, Mencher GT, McCall C. (1971) Modification of speech discrimination in patients with binaural asymmetrical hearing loss. J Speech Hear Disord. 36(2):208–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff JM, Staisloff HE, Kirchner A, Lee DH, Stelmach J. (2019) Pitch Matching Adapts Even for Bilateral Cochlear Implant Users with Relatively Small Initial Pitch Differences Across the Ears. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Noe CM, and Wilson RH (2001) Listeners who prefer monaural to binaural hearing aids. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 12: 261–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching TY, van Wanrooy E, and Dillong H. (2007) Binaural-bimodal fitting or bilateral implantation for managing severe to profound deafness: a review. Trends Amplif. 11(3): 161–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LS, Geers AE, Uchanski RM, and Firszt J. (2019) The effects of early acoustic hearing on speech perception and language for pediatric cochlear implant recipients. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 13:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawes P, and Bishop DVM (2008). Maturation of visual and auditory temporal processing in school-aged children. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res, 51: 1002–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman MF, and Gifford RH (2010) Combining acoustic and electric stimulation in the service of speech recognition. Int. J. Audiol. 49(12):912–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn CC, Tyler RS, and Witt SA (2005) Benefit of wearing a hearing aid on the unimplanted ear in adult users of a cochlear implant. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116: 1698–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gori M, Del Viva M, Sandini G, and Burr DC (2008) Young children do not integrate visual and haptic form information. Curr. Biol. 18(9): 694–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood D. (1990) A cochlear frequency-position function for several species−−29 years later. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 87(6):2592–2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose JH, and Mamo SK (2010) Processing of temporal fine structure as a function of age. Ear Hear. 31(6): 755–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerger J, Carhart R, and Dirks D. (1961) Binaural hearing aids and speech intelligibility. J Speech Hear. Res. 4:137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan A, Stoelb C, Litovsky RY, and Goupell MJ (2013) Effect of mismatched place-of-stimulation on binaural fusion and lateralization in bilateral cochlear implant listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 134(4): 2923–2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong YY, Stickney GS, Zeng FG (2005) Speech and melody recognition in binaurally combined acoustic and electric hearing. J Acoust. Soc. Am. 117: 1351–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Nadol JB, and Eddington DK. (2010) Depth of electrode insertion and postoperative performance in humans with cochlear implants: A histopathologic study. Audiol Neurotol 15:323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, Parkinson A, Arcaroli J, and Sammeth C. (2006a) Simultaneous bilateral cochlear implantation in adults: A multicenter clinical study. Ear. Hear. 27: 714–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky RY, Johnson PM, and Goday SP (2006b) Benefits of bimodal cochlear implants and/or hearing aids in children. Int. J. Audiol. 45(7): 78–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DR, Cowan JA, Riley A, Edmonson-Jones AM, and Ferguson MA (2011) Development of auditory processing in 6- to 11-yr old children. Ear Hear. 32(3): 269–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardini M, Bedford R, Mareschal D. (2010) Fusion of visual cues is not mandatory in children. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(39):17041–17046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nittrouer S, Caldwell-Tarr A, Sansom E, Twersky J, and Lowenstein JH (2014) Nonword repetition in children with cochlear implants: a potential clinical marker of poor language acquisition. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 23(4): 679–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nittrouer S. and Chapman C. (2009) The effects of bilateral electric and bimodal electric--acoustic stimulation on language development. Trends Amplif. 13(3):190–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell BP, Cakir A, Hunter JB, Francis DO, Noble JH, Labadie RF, Zuniga G, Dawant BM, Rivas A, Wanna GB (2016) Electrode Location and Angular Insertion Depth Are Predictors of Audiologic Outcomes in Cochlear Implantation. Otol. Neurotol. 37(8):1016–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y, Srinivasan N, Diedesch A, Hartling C, Gallun F, and Reiss L. (2018) Difficulty with understanding speech in background noise is predicted by broad binaural pitch fusion in bimodal cochlear implant users. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 143, 1719. [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y, and Reiss LAJ (2017) Binaural pitch fusion: Pitch averaging and dominance in hearing-impaired listeners with broad fusion. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 142(2): 780–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrott DR & Nelson MA (1969). Limits for the detection of binaural beats. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 6(2), 1477–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plakke BL, Orchik DJ, and Beasley DS (1981) Children’s performance on a binaural fusion task. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 24: 520–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LAJ, Turner CW, Erenberg SR, and Gantz BJ (2007) Changes in pitch with a cochlear implant over time. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 8(2): 241–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LA, Turner CW, Karsten SA, and Gantz BJ (2013) Plasticity in human pitch perception induced by tonotopically mismatched electro-acoustic stimulation. Neuroscience, 256: 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LAJ, Ito RA, Eggleston JL, Liao S, Becker JJ, Lakin CE, Warren FM, and McMenomey SO (2015) Pitch adaptation patterns in bimodal cochlear implant users: Over time and after experience. Ear. Hear. 36(2): e23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LAJ, Ito RA, Eggleston JL, and Wozny DR (2014) Abnormal binaural spectral integration in cochlear implant users. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol, 15(2): 235–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LA, Eggleston JL, Walker EP, and Oh Y. (2016) Two ears are not always better than one: Mandatory vowel fusion across spectrally mismatched ears in hearing-impaired listeners. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol, 17(4): 341–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LAJ, Fowler JR, Hartling CL, and Oh Y. (2018) Binaural pitch fusion in bilateral cochlear implant users. Ear. Hear. 39(2): 390–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LA, Perreau AE, and Turner CW (2012) Effects of lower frequency-to-electrode allocations on speech and pitch perception with the Hybrid short-electrode cochlear implant. Audiol. Neurotol. 17(6): 357–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss LAJ, Shayman CS., Walker EP, Bennett KO., Fowler JR, Hartling CL, Glickman B, Lasarev MR, and Oh Y. (2017) Binaural pitch fusion: Comparison of normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am.141(3): 1909–1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner MW, Ketten DR, Holden LK, Harding GW, Smith PG, Gates GA, Neely JG, Kletzker GR, Brunsden B, and Blocker B. (2002) CT-derived estimation of cochlear morphology and electrode array position in relation to word recognition in Nucleus-22recipients. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 3(3):332–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stakhovskaya O, Sridhar D, Bonham BM, Leake PA (2007) Frequency map for the human cochlear spiral ganglion: implications for cochlear implants. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 8(2):220–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel MM, Papsin BC, and Gordon KA (2015) Binaural fusion and listening effort in children who use bilateral cochlear implants: A psychoacoustic and pupillometry study. PLOS One 10(2): e0117611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]