Abstract

A 47-year-old male with a history of acute promyelocytic leukemia was admitted for his induction chemotherapy session with all-trans retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide. On day 25, his medical course became complicated with differentiation syndrome and he developed isolated acute pericarditis.

Keywords: arsenic trioxide (ato), all-trans retinoic acid (atra), acute myeloid leukemia (aml), differentiation syndrome, acute pericarditis

Introduction

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) is an aggressive type of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a high mortality rate. However, since the introduction of differentiating agents such as all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide (ATO) as induction chemotherapy, the mortality rate has highly reduced with the total recovery of most patients [1]. In a clinical trial of APL patients who received ATRA, De Botton et al. found the incidence of the retinoic acid syndrome, now called differentiation syndrome (DS), was 15%. He also reported that 89% of patients with DS developed respiratory distress and only 19% had a pericardial effusion [2]. DS is a life-threatening complication if not treated promptly. Signs and symptoms are often nonspecific and may include dyspnea, pulmonary interstitial infiltrates, fever, hypotension, acute renal failure, and pleuropericardial effusion [3]. We are presenting a rare case of acute pericarditis secondary to DS.

Case presentation

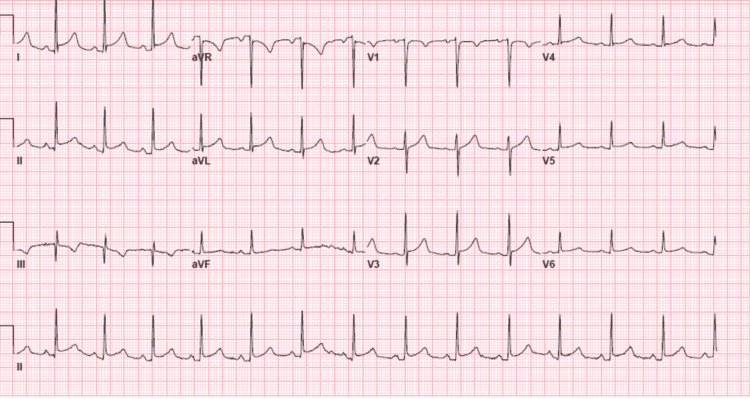

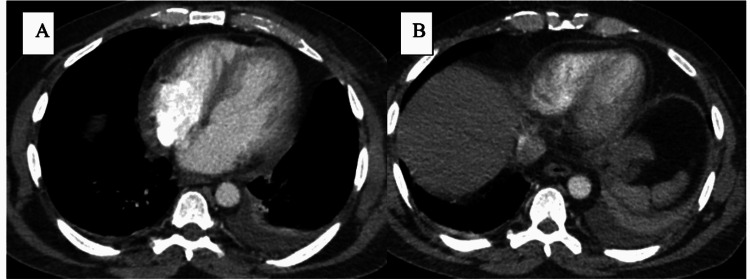

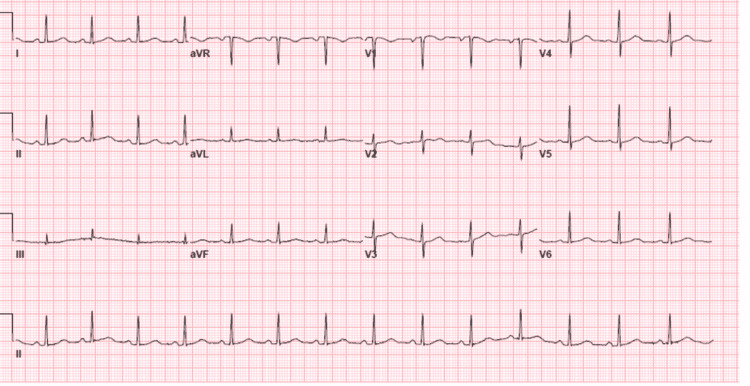

A 47-year-old male diagnosed with APL was admitted to a cancer center. Induction therapy consisting of ATRA and ATO was initiated. The patient had been well until the 25th day from the initiation of therapy, but then he began experiencing chest pain in the substernal region that was not radiating and improved when he leaned forward. The cardiology team was consulted to evaluate the chest pain. The patient had a history of hypertension and seizure disorder. His medications were hydrochlorothiazide and an anti-seizure drug (ASD). He did not report a history of smoking or drug abuse. His family history revealed coronary artery disease (CAD) in his father. Findings on a screening electrocardiogram (ECG) were normal. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) before the induction therapy revealed a normal left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) with no pericardial effusion. His temperature was 37°C, blood pressure was 118/64 mmHg, heart rate was 88 beats/min, respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation was 96%. The patient was looking acutely ill and there was no pericardial friction rub or rales on the chest exam. An ECG revealed sinus rhythm with diffuse ST-segment elevation and PR depression (Figure 1). TTE showed normal LVEF without wall motion abnormality or significant valvular disease, but there was a small pericardial effusion. Laboratory test findings indicated normal troponin level, pancytopenia, C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 164 mg/dl (range: 0-0.8 mg/dl), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 87 mm/hr (range: 0-15 mm/hr). Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was unremarkable for pulmonary embolism (PE), but there was small left pleural effusing and mild pericardial effusion (Figure 2). In view of normal troponin and normal cardiac function on TTE, we continued the ATRA and ATO therapy with caution and continuous monitoring. A diagnosis of acute pericarditis was made based on the characteristic chest pain and ECG findings, in addition to the pericardial effusion and elevated CRP. He was diagnosed and treated for acute pericarditis. The patient experienced some relief from symptoms after being given Toradol for acute pericarditis and steroids for DS. He was also started on oral colchicine 0.6 mg once per day for three months. The patient’s symptoms subsided over the course of treatment with the resolution of the ECG’s changes during monitoring, and no further imaging was performed. The patient was completely asymptomatic, and his ECG showed resolution of ST-segment elevation and PR depression three days after the initiation of colchicine (Figure 3). He followed up with the cardio-oncology clinic as an outpatient, and he will be maintained on colchicine for three months.

Figure 1. Twelve-lead electrocardiogram showing diffuse ST elevations and PR depression.

Figure 2. Chest CT showing mild pericardial effusion and left side pleural effusion.

Figure 3. Twelve-lead electrocardiogram showing normal sinus rhythm with the resolution of ST and PR segments abnormalities.

Discussion

APL DS is recognized when patients with APL are treated with ATRA and/or ATO. Frankel et al. reported the first case of DS in 1992, describing it as a potentially lethal syndrome if not diagnosed and treated promptly [3]. To date, DS has no specific criteria for the diagnosis, and it requires a high index of suspicion as the presentation can be variable. Common symptoms and findings upon presentation include dyspnea, fever, chest pain, hypotension, pleuropericardial effusion, and acute kidney injury.

In DS, reported cases have shown cardiac involvement [4-13]. Myopericarditis was described in four cases, myocarditis was present in five cases, while the involvement of entire cardiac wall layers was seen in one case. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first reported case of isolated pericarditis as a cardiac involvement with DS. Acute pericarditis is most often associated with viral infection or is idiopathic. According to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) clinical practice guidelines, the clinical diagnosis of acute pericarditis can be made with two out of four criteria including chest pain, pericardial rub, newly widespread ST-elevation or PR depression on the ECG, and pericardial effusion [14]. CRP is an important inflammatory marker when acute pericarditis is clinically suspected, and it plays an important role in the monitoring of the disease’s progression and treatment response. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and colchicine are considered the primary treatment, with corticosteroids considered as an alternative [15].

In our patient, a clinical diagnosis of acute pericarditis was made based on the presence of three criteria, in addition to the elevated inflammatory markers and recent initiation of ATRA chemotherapy. Meanwhile, we considered other differential diagnoses including CAD, PE, and myocarditis. However, the cardiac enzyme was not elevated, the EKG had no horizontal ST-elevation, the TTE had normal LVEF without wall motion abnormality, and the chest CT with contrast excluded PE.

Conclusions

APL needs prompt initiation of induction chemotherapy with ATRA for effective treatment; however, ATRA can cause a fatal drug reaction that usually results in the development of DS. We describe a case of isolated pericarditis secondary to the development of DS, which is a fatal complication resulting from ATRA chemotherapy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of isolated acute pericarditis as a presentation of DS. To date, DS has no specific criteria for the diagnosis, and it requires a high index of suspicion as the presentation can be variable.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.History of acute promyelocytic leukemia: a tale of endless revolution. Lo-Coco F, Cicconi L. https://doi.org/10.4084/MJHID.2011.067. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2011;3:0. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2011.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Incidence, clinical features, and outcome of all trans-retinoic acid syndrome in 413 cases of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. The European APL Group. De Botton S, Dombret H, Sanz M, et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9763554/ Blood. 1998;92:2712–2718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The "retinoic acid syndrome" in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Frankel SR, Eardley A, Lauwers G, Weiss M, Warrell RP Jr. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/0003-4819-117-4-292. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117:292–296. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-4-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A rare case of perimyocarditis induced by all-trans retinoic acid administration during induction treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Ben El Makki A, Mahtat EM, Kheyi J, Bouzelmat H, Chaib A. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31750445/ Med Pharm Rep. 2019;92:418–420. doi: 10.15386/mpr-1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.All-transretinoic acid (ATRA) treatment-related pancarditis and severe pulmonary edema in a child with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Işık P, Çetin I, Tavil B, Azik F, Kara A, Yarali N, Tunc B. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2010;32:0–8. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e75731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.A case of ATRA-induced isolated myocarditis in the absence of circulating malignant cells: demonstration of the t(15;17) translocation in the inflammatory infiltrate by in situ hybridisation. van Rijssel RH, Wegman J, Oud ME, Pals ST, van Oers MH. Leuk Res. 2010;34:0–4. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Two cases of isolated symptomatic myocarditis induced by all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) Klein SK, Biemond BJ, van Oers MH. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:917–918. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0333-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reversible symptomatic myocarditis induced by all-trans retinoic acid administration during induction treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia: rare cardiac manifestation as a retinoic acid syndrome. Choi S, Kim HS, Jung CS, et al. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2011;19:95–98. doi: 10.4250/jcu.2011.19.2.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Recurrent acute myopericarditis without effusion during ATRA induction and ATO salvage of APL: a variant form of the differentiation syndrome? Vassilakopoulos TP, Asimakopoulos JV, Plata E, et al. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58:1743–1746. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1253838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Severe myopericarditis following induction therapy with idarubicin and transretinoic acid in a patient with acute promyelocytic leukemia. Carcelero San Martín E, Riu Viladoms G, Creus Baró N. Med Clin (Barc) 2018;22:492–493. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2017.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.All-trans retinoic acid induced cardiac and skeletal myositis in induction therapy of acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Fabbiano F, Magrin S, Cangialosi C, Felice R, Mirto S, Pitrolo F. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:444–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.All-trans retinoic acid-induced isolated myocarditis: a case report and review of the literature. Karakulak UN, Aladag E, Hazirolan T, Ozer N, Demiroglu H, Goker H. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:2101–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Differentiation syndrome-induced myopericarditis in the induction therapy of acute promyelocytic leukemia: a case report. Shenoy SM, Di Vitantonio T, Plitt A, et al. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40959-021-00124-9. Cardiooncology. 2021;7:39. doi: 10.1186/s40959-021-00124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.2015 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Adler Y, Charron P, Imazio M, et al. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26320112/ Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2921–2964. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Treatment with aspirin, NSAID, corticosteroids, and colchicine in acute and recurrent pericarditis. Imazio M, Adler Y. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-012-9328-9. Heart Fail Rev. 2013;18:355–360. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]