Abstract

Background and Objective:

Understanding the way nonexercisers view the benefits and barriers to physical exercise helps promote physical exercise. This study reports perceived benefits and negative outcomes of yoga perceived by yoga-naïve persons.

Methods:

The 2550 yoga-naïve respondents of both sexes (m:f = 2162:388; group mean age ± SD 23.5 ± 12.6 years) participated in a convenience sampling in-person survey conducted to determine the perceived benefits and negative outcomes of yoga.

Results:

Among 2550 respondents, 97.4% believed yoga practice had benefits. The three most common perceived benefits of yoga were improvement in (i) physical health (39.8%), (ii) cognitive functions (32.8%), and (iii) mental health (20.4%). Among the respondents, 1.4% believed that yoga had negative outcomes. The three most common perceived negative outcomes were (i) apprehension that wrong methods may be harmful (0.24%), (ii) apprehension that excessive practice may harm (0.24%), and (iii) laziness (0.12%).

Conclusion:

The most common perceived benefit of yoga practice was “improvement in physical health,” with “apprehension that wrong or excessive practice could be harmful” as the most common perceived negative outcomes of yoga.

Keywords: Naïve to yoga persons, perceived benefits, perceived negative outcomes, yoga

Introduction

Understanding the way nonexercisers perceive the benefits and barriers to physical activity has mediated change promoting physical activity.[1] While the practice of yoga includes an increase in physical activity and calmness of the mind, there are also several similarities between the factors associated with regular physical activity or yoga practice as a lifestyle choice.[2,3]

Several surveys have reported yoga practitioners’ benefits from yoga practice.[4,5,6] A survey on 3135 yoga practitioners in India reported that the most common benefits were improvement in (i) physical fitness, (ii) mental state, and (iii) cognitive functions.[6] The most common negative outcomes reported were (i) soreness and pain, (ii) muscle injuries, and (iii) fatigue.[6] These findings were comparable to previously reported benefits and negative outcomes of yoga from the US, UK, Japan, and Germany.[4,5,7,8] These results suggest that yoga practitioners with varying experience of yoga practice experience and report improved physical health as well as benefits to mental health.

Reports about the benefits and negative effects of yoga as perceived by yoga-naïve persons are scarce. An understanding of the perceptions of yoga naïve persons about the benefits and negative outcomes of yoga is essential to promoting yoga practice. With this background, the present survey was conducted to determine perceived benefits and negative outcomes of yoga in yoga-naïve persons.

Materials and Methods

Respondents

Convenience in person sampling was used to distribute the survey sheets to persons at a public event on yoga.[9] The inclusion criteria were (i) participation in the event and (ii) having completed 10 years of age, as the minimum age required for children to respond to questions accurately.[10] The exclusion criterion was prior experience of yoga practice. Of the 8600 respondents who returned the survey sheet, 5441 had practiced yoga before and their responses have been published elsewhere.[6] Incomplete or incorrectly filled surveys were also excluded. The signed informed consent of each respondent was obtained.

Study design

Prior clearance from the institutional ethical committee was obtained to conduct the survey (approval number YRD-018/002). The study is reported according to the recommendations of “The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.”

The survey

The survey was originally developed in English and was translated into Hindi (i.e., local language). The method of translating the survey from English to Hindi has been described elsewhere.[6]

The survey was developed to understand the perceived benefits and negative outcomes of yoga by yoga-naïve persons. The survey had three questions. The first question was to identify yoga-naïve persons from those who had prior yoga experience (i.e., question 1(a) “have you practiced yoga before?” respond “yes” or “no”). Those who had prior experience of yoga were excluded.

The second and third questions of the survey had one parent question and one follow-up question. The follow-up questions were for those who responded “yes” to parent questions. The second question was question 2(a) (i.e., question 2(a) “’Do you think that there is any benefit of practicing yoga?” respond “’Yes” or “No”; question 2(b) “If your response to question 2(a) was “Yes,” mention the most definitive benefit of yoga you think can occur).” The third question was question 3(a) “’Do you think that there can be any negative outcome of practicing yoga?” respond “’Yes” or “No”; question 3(b) “’If your response to question 3(a) was “Yes,” mention the most definite negative outcome of yoga you think can arise by practicing yoga.” Responses to questions 1 were mandatory for all the participants, whereas the responses to questions 2(b) and 3(b) were mandatory for those who responded “Yes” to questions 2(a) and 3(a).

The characteristics of the respondents such as age and gender were obtained separately.

Data cleaning

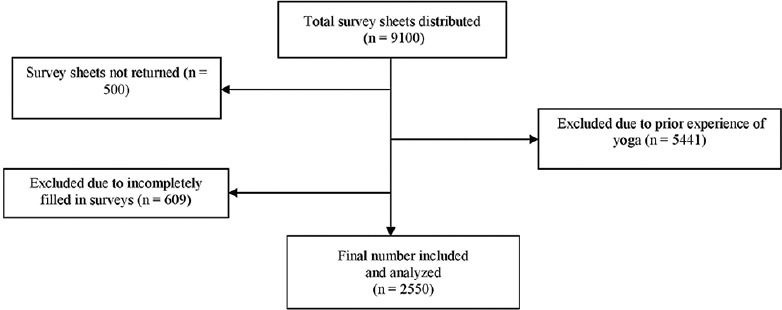

Nine thousand and one hundred survey sheets were distributed. Of these, 8600 respondents returned the survey, of which 5441 had prior experience of yoga and were excluded from the present analysis. From the remaining 3159 respondents, 609 were excluded due to the following reasons: (i) 280 did not mention clearly whether they had prior experience of yoga or not and (ii) 329 were excluded as their responses to either question 2(b) or question 3(b) were unclear. Hence, data of 2550 (29.7% of the total respondents who returned the survey) respondents were used for analyses.

Data analysis

The percentages of respondents who reported perceived benefits and perceived negative outcomes of yoga were calculated.

Results

Two thousand five hundred and fifty respondents completed the survey satisfactorily and their responses were analyzed. The number of respondents at different stages of the trial is provided in Figure 1. The baseline characteristics of the respondents are provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Trial profile

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the respondents

| Characteristics | n=2550 |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Age range | 10-77 |

| Group mean age±SD | 23.5±12.6 |

| Gender (male: female) | |

| Actual values | 2162:388 |

| Percentage values | 84.78:15.22 |

| Years of education (%) | |

| 10 and less | 629 |

| 11-12 | 1117 |

| 13-15 | 395 |

| 16 and above | 215 |

| Not mentioned | 194 |

SD: Standard deviation

Perceived benefits of yoga

Two thousand four hundred eighty-four respondents (97.4% of the total respondents who completed the survey satisfactorily) reported perceived benefits of yoga [Table 2]. The three most common perceived benefits were improvement in (i) physical health (n = 988; 39.8% of the total respondents), (ii) cognitive health (n = 814; 32.8% of the total respondents), and (iii) mental health (n = 504; 20.4% of the total respondents).

Table 2.

Gender- and age-wise details of the respondents who reported perceived benefits and perceived negative outcomes of yoga

| Characteristics | Subcharacteristics | n (%) | Perceived benefits | Perceived negative outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |||

| Gender | Male | 2162 (84.78) | 2110 (97.59) | 52 (2.41) | 30 (1.39) | 2132 (98.61) |

| Female | 388 (15.22) | 374 (96.39) | 14 (3.61) | 7 (1.80) | 381 (98.20) | |

| Age (years) | 10-12 | 31 (1.22) | 31 (100) | 0 | 1 (3.23) | 30 (96.77) |

| 13-20 | 1728 (67.77) | 1688 (97.69) | 40 (2.32) | 25 (1.45) | 1703 (98.55) | |

| 21-44 | 542 (21.26) | 525 (96.86) | 17 (3.14) | 6 (1.11) | 536 (98.89) | |

| 45-59 | 178 (6.98) | 171 (96.07) | 7 (3.93) | 3 (1.69) | 175 (98.32) | |

| 60 and above | 71 (2.78) | 68 (95.78) | 3 (4.23) | 1 (1.41) | 70 (98.59) | |

Perceived negative outcomes of yoga

Thirty-five respondents (1.4% of the total number of respondents) reported perceived negative outcomes of yoga [Table 2]. The three most common negative outcomes reported were (i) apprehension that wrong methods may cause negative outcomes (0.24% of the total respondents), (ii) apprehension that excessive practice may cause negative outcomes (0.24% of the total respondents), and (iii) lethargy (0.12% of the total respondents).

Discussion

97.4% of the yoga-naïve respondents reported perceived benefits of yoga and 1.4% reported perceived negative outcomes.

The three most common perceived benefits of yoga were of three categories, namely (i) physical health which includes improved physical fitness, better physical strength, balance, flexibility, body weight regulation, and ability to carry out physical activity (reported by 39.8%), (ii) cognitive health indicates an improvement in attention, concentration, learning, and memory (32.8%), and (iii) mental health functions included positive affect, increased satisfaction with life, and reduced depression (20.4%). The three categories of perceived benefits reported were the same as the categories of benefits experienced by yoga-experienced population.[6]

Most yoga-naïve persons perceived better physical health as the most likely outcome of yoga practice. These findings are supported by the results of a pre–post survey on yoga-naïve adults assessed at baseline before a 4-week yoga program for which they had enrolled (n = 604 at baseline, response rate = 16%–47%).[11] Participants were asked whether they perceived yoga as an exercise activity, a spiritual activity, or as a means to treat a health condition. Ninety-two percent of the respondents who were naïve to yoga at baseline considered yoga as an exercise activity, which was more than those who perceived yoga as a spiritual activity (73%) or as a means to treat a health condition (50%). Furthermore, earlier surveys on the benefits of yoga in yoga-experienced persons showed similar results.[4,5,6] Hence, yoga practice is often perceived as an exercise activity, perhaps because the perceived and experienced benefits to physical fitness are the most common.

In the present study, cognitive benefits were reported as the second most common perceived benefit (32.8%). In a comparable population who were yoga experienced, cognitive benefits were cited as a common experienced benefit, though by fewer persons (13.2%).[6] Comparably, 20.4% of yoga-naïve persons in the present study believed that yoga would lead to a positive mental state, while a positive mental state was reported as an experienced benefit by 28.5% of yoga-experienced persons in an earlier report.[6]

Previously, 94.5% (n = 2963 out of 3135) of yoga-experienced persons from the same background as the present respondents reported benefits of yoga which they had experienced.[6] This indicates that the perceived benefits of yoga reported by the respondents of the present study are well supported by the experienced benefits by the yoga practitioners.[6]

The three most common negative perceptions reported in the present study were (i) practicing yoga wrongly could be harmful (0.24%), (ii) yoga practice could be strenuous (0.24%), and (iii) practicing yoga could increase lethargy (0.12%). The perceived negative outcomes of yoga here differ from the experienced negative outcomes reported previously (i.e., (i) soreness and pain, (ii) muscle injuries, and (iii) fatigue).[6] These differences in the experienced versus perceived negative outcomes of yoga indicate that there should be more information regarding the safety of yoga practice.

In summary, while the perceived benefits reported here are supported by reported benefits experienced, the perceived negative outcomes are not similarly supported.

The main limitations of the study are (i) the respondents had an interest in yoga as they had chosen to be part of a public event on yoga, (ii) respondents were recruited by convenience sampling, and (iii) a large number of responses were incomplete and had to be excluded.

Future directions

In future research, yoga-naive persons with no specific inclination toward yoga could be examined to determine their perceptions about the benefits and negative outcomes of yoga. These perceptions could be correlated with the persons’ likelihood of starting and subsequently adhering to practicing yoga to better understand factors promoting yoga practice.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nahas MV, Goldfine B. Determinants of physical activity in adolescents and young adults: The basis for high school and college physical education to promote active life styles. Phys Educat. 2003;60:42–57. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ezrin S. 16 Benefits of Yoga that are Supported by Science. Healthline. [Last accessed on 2022 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/13-benefits-of-yoga#:~:text=This%20article%20takes%20a%20look%20at%2013%20evidence-based, of%20cortisol%2C%20the%20primary%20stress%20hormone%20%282%2C%203%29 .

- 3.Varshney M, Parel JT, Raizada N, Sarin SK. Initial psychological impact of COVID-19 and its correlates in Indian Community: An online (FEEL-COVID) survey. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0233874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park CL, Riley KE, Braun TD. Practitioners’ perceptions of yoga's positive and negative effects: Results of a National United States survey. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2016;20:270–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartwright T, Mason H, Porter A, Pilkington K. Yoga practice in the UK: A cross-sectional survey of motivation, health benefits and behaviours. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e031848. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Telles S, Sharma SK, Chetry D, Balkrishna A. Benefits and adverse effects associated with yoga practice: A cross-sectional survey from India. Complement Ther Med. 2021;57:102644. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsushita T, Oka T. A large-scale survey of adverse events experienced in yoga classes. Biopsychosoc Med. 2015;9:9. doi: 10.1186/s13030-015-0037-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer H, Quinker D, Schumann D, Wardle J, Dobos G, Lauche R. Adverse effects of yoga: A national cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19:190. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2612-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.HT Correspondent. Baba Ramdev's Three-Day-Long Yoga Camp Begins in Kota. Hindustan Times. [Last accessed on 2018 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.hindustantimes.com/jaipur/baba-ramdev-s-three-day-long-yoga-camp-begins-in-kota/story-w41uDJWy4AuUGnypx673VI.html .

- 10.Lerner RM, Steinberg L. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, Individual Bases of Adolescent Development. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quilty MT, Saper RB, Goldstein R, Khalsa SB. Yoga in the real world: Perceptions, motivators, barriers, and patterns of use. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2:44–9. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2013.2.1.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]