Abstract

In the past decade of microbiome research, we have learned about numerous adverse interactions between the microbiome and medical interventions such as drugs, radiation, and surgery. What if we could alter our microbiomes to prevent these events? Here, we discuss potential routes to mitigate microbiome adverse events including applications from the emerging field of microbiome engineering. We highlight cases where the microbiome acts directly on a treatment, such as via differential drug metabolism, and cases where a treatment directly harms the microbiome, such as in radiation therapy. Understanding and preventing microbiome adverse events is a difficult challenge which will require a data driven approach involving causal statistics, multi-omics techniques, and a personalized approach to adverse event mitigation. Here, we propose research considerations to encourage productive work in preventing microbiome adverse events and we highlight the many challenges and opportunities that await.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the past decade, research on the microbiological ecosystems (‘microbiomes’) that inhabit our body became widely accessible due to advances in molecular biology and high throughput genomic sequencing 1. One stream of this research focuses on identifying interactions between drugs, other medical interventions, and the microbiome 2–6. Research into microbiome-driven drug metabolism has led to the discovery of enzymes present in certain bacteria which, if present within an individual, can interact with a drug, leading to a differential response 7. For example, the chemotherapeutic drug irinotecan may have its pharmacological safety reduced if the person taking the drug has high abundances of bacteria carrying beta-glucuronidase enzymes which modify an inactive irinotecan metabolite into a toxic metabolite 8–10. There are also more general scenarios where a medical intervention ‘harms’ an individual’s microbiome. For example, antibiotics can reduce the diversity of the system and enable opportunistic pathogens such as C. difficile to take root by eliminating commensal organisms that prevent its emergence 11.

The diversity of microbiome-driven phenomena in medicine goes beyond drugs. Procedures such as radiotherapy and surgery can have destructive effects on the microbiome, and non-medical activities such as diet and lifestyle can alter it in potentially harmful (or beneficial) ways 12–16. This effect can happen in both directions; the microbiome can alter a treatment, and a treatment can alter the microbiome. We will refer to either of these phenomena collectively as microbiome adverse events (MAE).

Adverse interactions associated with the microbiome are fundamentally different from phar-macogenomic mediated adverse events because, instead of a single or group of variants in the human genome, the phenomenon is mediated by an entire ecosystem in the human body 17. The microbiome ecosystem is constantly changing in response to its environment, making it difficult to pin down a specific ‘variant’ driving adverse event risk. This has implications for how this system should be studied and modulated. We will argue that it is necessary to assay microbiomes at multiple time points throughout a study in order to think in terms of how a treatment perturbed a specific patient microbiome or how the pretreatment community composition was associated with outcomes. However, these challenges also come with silver lining: since the microbiome is so easily perturbed, what if we could deliberately alter it to favor a desired outcome?

Another stream of microbiome research focuses on such questions in the context of personalized diagnostics and treatments. Microbiome diagnostic and treatment research includes machinelearning models to diagnose disease, methods to engineer one’s microbiome to treat a disease, and methods to engineer a ‘healthy’ gut via supplements 18–20.

However, most work in microbiome engineering has been focused on treating disease states and improving health. Here, we highlight the applications of microbiome engineering toward the goal of mitigating microbial adverse events 21–23. The intersection of these two streams has not received as much attention as other topics despite the clinical need for such therapies 24. Here, we highlight some of the work that has been done and the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. We begin by discussing microbiome engineering modalities and their potential usefulness in MAE mitigation. We discuss specific cases of known MAE/treatment interactions and ongoing research.

MAE can be broadly classified into two categories: 1) events where the microbiome serves as a ‘cofactor’, modifying a particular treatment to produce an unwanted effect; and 2) events where the treatment directly or indirectly alters the microbiome in a significant manner. We conclude by discussing statistical challenges and reproducibility concerns. Our overarching argument is that meta-’omics should serve a central technology to frame questions about MAE mitigation in studies seeking causal relationships involving the microbiome.

2. Microbiome Engineering: An Emerging Field

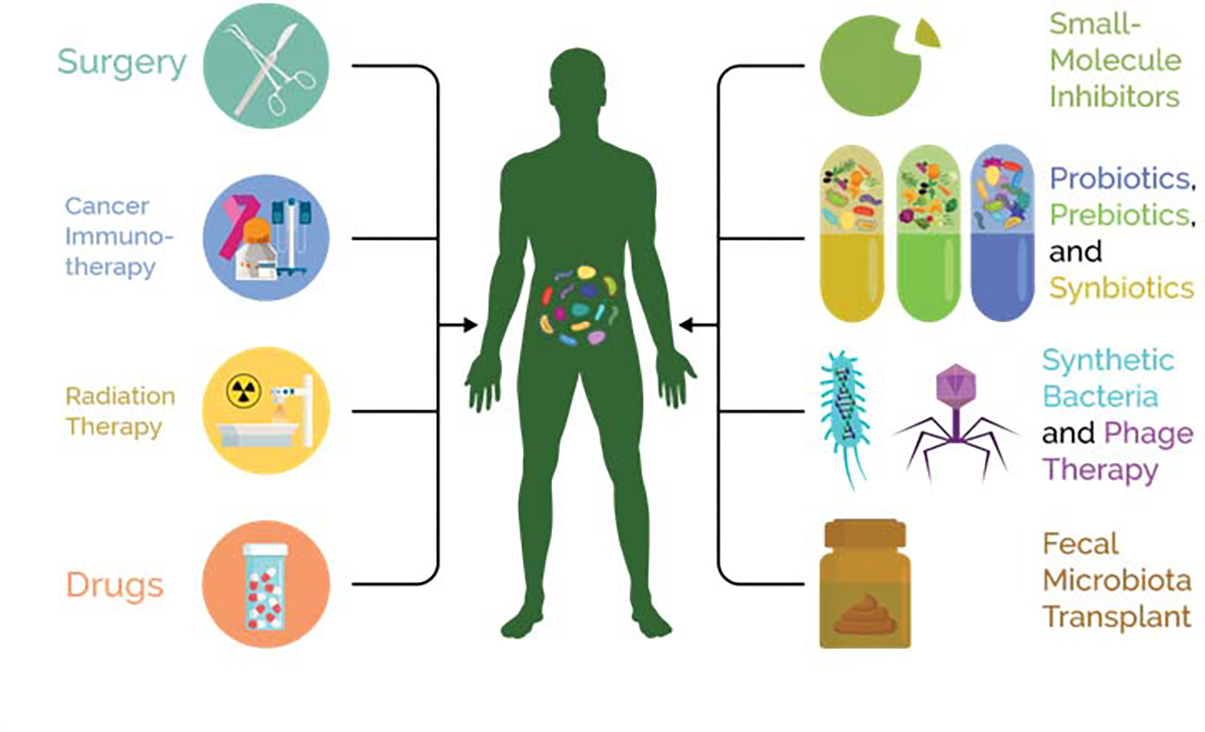

As microbiome research develops, we can shift from a search for statistical associations to a search for causal relationships. Causal relationships can include effects of the microbiome on an an intervention (for example the microbiome conversion of drugs such as levodopa 25, irinotecan 8, 9, and digoxin 26, 27 or of an intervention on the microbiome (for example the effect of radiation on microbiome diversity 28. As we begin to unravel these relationships, we can ask how to encourage desired patient outcomes by precisely engineering a patient microbiome. The emerging field of microbiome engineering faces two key challenges: precision and magnitude. How can we make the effects of our perturbations to a microbiome as focused on a specific set of organisms as possible, and how can we ensure that the microbiome is actually changing in response to our perturbation? These are active research topics consolidated around the concept of treating diseases and improving overall health in a personalized manner 22. Here, we illustrate how microbiome engineering could be a promising approach to treating and preventing microbial adverse events; Figure 1 provides an overview of engineering modalities along with some examples of treatments which can haveadverse interactions with the microbiome.

Figure 1:

Both treatments and engineering modalities are a two-way street. Each can have effects on and also be altered by the host and their microbiome.

Fecal Microbiota Transplant

Perhaps the most blunt and dramatic means to engineer a microbiome is fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), which transfers an entire microbiome from a healthy donor to a recipient. FMT was initially developed to treat recurrent C. difficile colitis 29. FMT is a powerful tool with many potential applications but numerous caveats. For example, the method of administration can vary, and each has variable success rates. Transplant can be performed via an oral capsule containing fecal extracts 30–32, colonoscopy guided insertion 32, 33, or implantation of an enema 34, 35. Healthy donors can also vary widely in microbiome composition, and donor composition can affect success rates, but the causative microbiome features that lead to a successful or failed FMT remain unknown 36, 37. Additionally, FMT involves risks, and regulatory bodies have recently administered safety alerts regarding the risk for transmission of antibiotic resistant organisms via FMT 38.

These uncertainties limit our understanding of how fecal transplants could be used in new applications. Ideally, we should be able to use our knowledge of the mechanisms of MAE and the microbiome ecology to select the most appropriate donor based on their microbiome composition. This was proposed by Duvallet et al. who presented a framework for donor selection based on a model of the disease/intervention in question 39.

Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Synbiotics

Another approach is to administer a formulation of compounds and spores which promote growth of desirable bacteria in the gut. These are colloquially referred to as probiotics, although the term specifically refers to formulations containing live mi-croorganisms 40. Prebiotic refers to compounds such as oligosaccharides and fibers which promote the growth of specific bacteria 41, 42. A synergistic combination of these is called a synbiotic 43.

The appeal of this strategy is that one could theoretically incorporate any combination of microorganisms to construct a targeted, personalized synbiotic, and this may one day be a reality. However, a recent review by Suez et al. highlights numerous challenges standing in the way of that goal 44. For one, the variety of possible synbiotics makes it difficult to make comparisons; different studies use different formulations, doses, and regimens. Additionally, it is not always clear whether a synbiotic regimen actually altered a microbiome, and this could lead to negative results when a stronger dose could have had meaningful effects. Lastly, synbiotics themselves can cause adverse events, and their safety profile is often overlooked 45, 46. However, they have still shown efficacy in many studies, and there is active research to address these problems, some of which we discuss here.

Synthetic Microbes

Whereas the previous methods typically modulate bacteria naturally occurring within our microbiomes, research is also now underway to create synthetic microorganisms with artificially modified genetic pathways to create a specific desired effect.

Many bacterial genera have been engineered in this way, and these organisms can be used as chassis to deliver genetic payloads. For example, Steidler et al. developed a genetically modified strain of L. lactis to deliver the cytokine IL-10 to treat colitis in a mouse model 47. These payload activations can also be tied to specific signals; Hwang et al. developed an E. coli strain which detects a quorum-sensing molecule secreted by the pathogen P. aeruginosa and secretes antibiotics against that pathogen in response 48. The possible functions that these bacteria can be programmed for are becoming increasingly impressive over time. For example, Mimee et al. embedded a microelectronic device inside an E. coli strain which could wirelessly relay signals to a receiver when it detected bleeding events in a host 49. Much of the work in this field has focused on pathogen elimination or host health monitoring, but synthetic bacteria could become a powerful tool for general purpose microbiome engineering such as for MAE mitigation in the future (23); to date there are no successful interventions that utilize engineered microbes to improve patient outcomes.

Phage therapy is another promising technology for precision microbiome engineering. The goal of phage therapy is to isolate or design phages that infect and kill certain undesired bacteria such as pathogens. This has been used in Eastern Europe since the early 20thcentury as a treatment for infections, which have been the primary use case, but it could be used for other applications as well 50. Paule et al. suggested in a review that phages could serve as a general tool for treating microbiome associated pathologies; this approach could naturally extend to adverse event mitigation 51.

However, phage therapy carries its share of problems. Phages are live organisms, and as such, they could theoretically evolve and cause unknown effects on a microbial community 52. It is challenging to design phages with a specific desired host-range, although there has been progress here as well 53. For example, Dunne et al. recently demonstrated a method to modulate the host range of a bacteriophage using a combination of computational techniques, high-throughput screens, and synthetic biology; this approach could be used to tune the specificity of the treatment 54. Personalized phage therapy has already been successfully performed in a handful of extreme cases. Two examples include a successful last resort treatment for a diabetic patient at UCSD Medical Center infected with multidrug resistant A. baumannii 55 and successful treatment of a disseminated Mycobacterium abscessus infection in a patient with cystic fibrosis 56. Thus, phage therapy is becoming increasingly popular as potential applications for microbiome engineering grow 57.

3. Preventing Adverse Effects of the Microbiome on Treatments

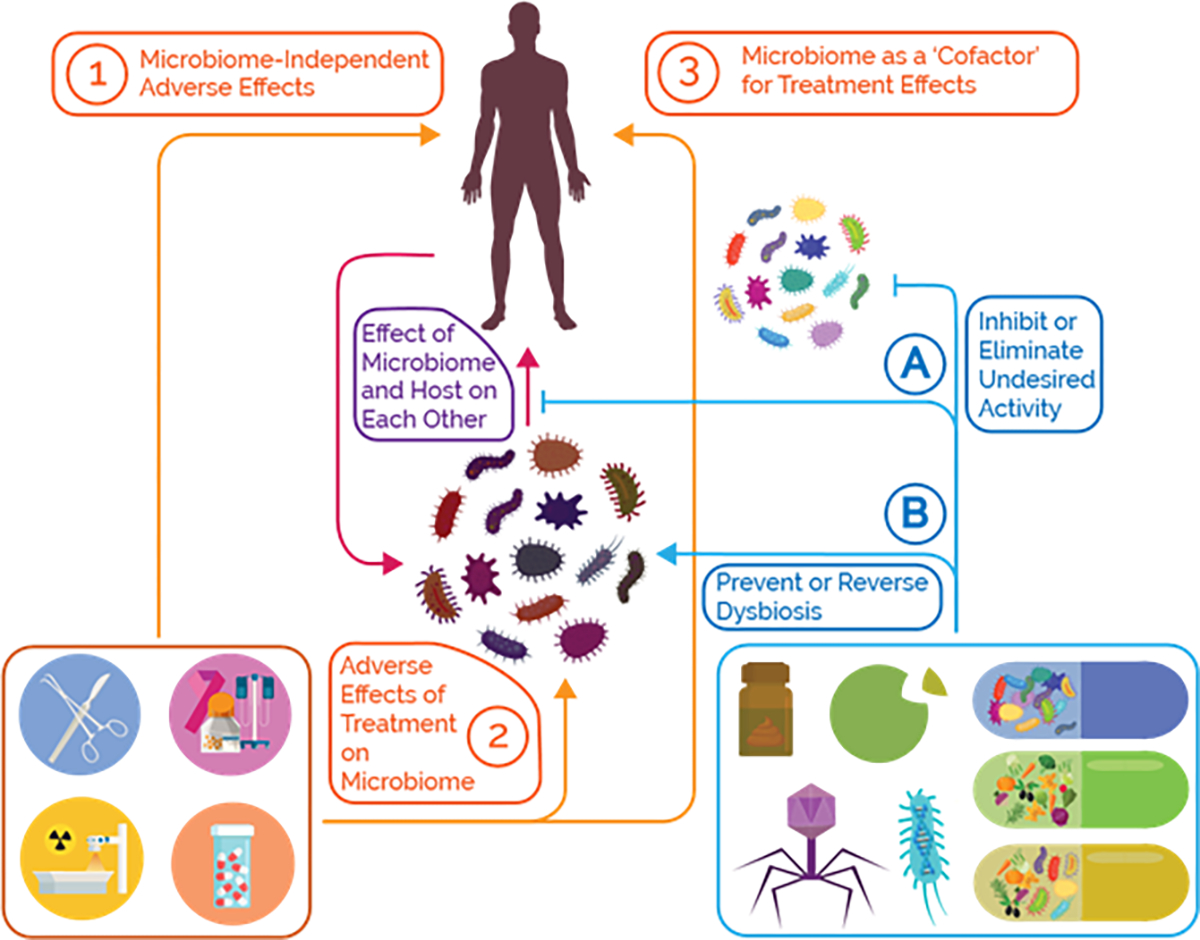

A well understood class of MAE are the chemical modification of food and drugs by enzymes in certain bacteria. This is an example of the microbiome acting as a ‘cofactor’; the original treatment is modulated and has its original effect increased, decreased, or supplemented with a toxic side-effect (Figure 2). Here, we discuss cases where drugs are reactivated or inactivated by the microbiome, potential methods to prevent unwanted microbiome/drug interactions, and production of toxic byproducts by the microbiome. We note that prior reviews cover many additional microbiome/drug interactions 2–6.

Figure 2: Microbial Adverse Events and Mitigation Strategies.

MAE can be broadly classified into two categories: (2) events where the treatment directly or indirectly alters the microbiome, and (3) events where the microbiome serves as a ‘cofactor’, modifying a particular treatment to produce an unwanted effect. In the latter case, these perturbations can have their own negative effects. We must also distinguish adverse phenomena mediated by the microbiome from microbiome-independent pathways (1), which is an important consideration when researching this topic. In order to demonstrate an MAE takes place, we must implicitly show that the microbiome actually mediates the event. This also informs mitigation strategies; we can attempt to block the microbial pathways driving the adverse interaction or alter the composition in order to reverse an undesired perturbation or eliminate an undesired function from the community.

Drug Reactivation

Some bacteria can interfere with drug metabolism, causing a drug to remain active or to reactivate. Many drugs are normally modified in the liver by addition of a hydrophilic moiety as part of that drug’s metabolism 58. In the case of the colorectal cancer drug irinotecan, the active metabolite, SN-38, becomes glucuronidated (conjugated) to facilitate its excretion. However, a class of enzymes called β-glucuronidases can de-conjugate this compound in the intestine, returning it to its active form. β-glucuronidases are diverse and widespread across many taxa 8, 59, and these enzymes are not specific to irinotecan but rather affect the metabolism of many other compounds such as environmental toxins like bisphenol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and hormones 60–63.

The association between β-glucuronidases and irinotecan toxicity has led to an active search for methods to suppress microbial β-glucuronidase activity; numerous natural and synthetic inhibitors have been discovered 9, 64, 65. Moreover, inhibition of these enzymes has been shown to eliminate harmful side-effects without impacting drug efficiency. Tumorbearing mice treated with irinotecan and a β-glucuronidase inhibitor prevented intestinal colitis and diarrhea associated with irinotecan without affecting the antitumour effects of the drug 9, 65. The same protective phenomenon was observed in mice treated with the NSAID diclofenac co-administered with a β-glucuronidase inhibition 66.

However, most of these molecules only inhibit specific isoforms of β-glucuronidase; this can limit their utility because there are many isoforms of this enzyme in different bacteria 8, 10. Microbiome genomic diversity is a general challenge in MAE mitigation; there is rarely just one enzyme that needs to be inhibited, but rather a family of enzymes. Guthrie et al. proposed an alternative strategy: supplementing patients with food compounds that are naturally glucuronidated to competitively overwhelm the β-glucuronidases 4. Such a strategy could be safe, easy, and robust in implementation. Lastly, even if we cannot mitigate the event, we may be able to predict it and adjust the treatment. Clinical trials have been conducted to predict irinotecan toxicity using host genomics, but none yet have looked at using host gut microbiome to predict adverse event risk 67.

Drug Deactivation

L-dopa The Parkinson’s disease drug L-dopa can be converted into dopamine by the microbial enzyme tyrosine decarboxylase (TDC), which reduces L-dopa bioavailability. Any L-dopa that is converted into dopamine before crossing the blood brain barrier (BBB) would not have the desired therapeutic effect because dopamine cannot cross the BBB 68. L-dopa is administered with the aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) inhibitor, carbidopa, to prevent L-dopa from prematurely getting converted into dopamine in the peripheral blood circulation and to increase the concentration that reaches the brain 68. L-dopa/carbidopa in combination are the most effective treatments for the symptoms of Parkinson disease 68. Even when administered with carbidopa, only 47% of intact L-dopa remains the blood after one hour. Intestinal loss of L-dopa can be driven by gut bacteria which have their own TDC enzymes 69.

Thus, inhibitors targeting microbial TDC may increase the bioavailability of L-dopa. Recently, Maini et al. discovered that (S)-α-Fluoromethyltyrosine (AFMT) inhibits TDC in multiple gut bacteria from patient stool samples 25. Although not yet validated in clinical trials, this would serve as an example of a drug blocking multiple isoforms of an enzyme - a very difficult task in drug design.

Toxic Byproducts

Ingested compounds Microbial enzymes can also produce toxic byproducts from metabolism of ingested foods. For example, microbial enzymes metabolize the amino acid tyrosine into p-cresol which is associated with increase risk of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity in healthy individuals 70. P-cresol competes for the same sulfotransferase and sulfonate donors that detoxify acetaminophen, and is associated with decreased urinary excretion of acetaminophen sulfate 70. P-cresol can also be sulfonated in the liver into p-cresyl sulfate which reduces dialysis efficacy in chronic kidney disease patients. Similarly, the bacterial metabolite indoxyl sulfate reduces dialysis efficacy, and both p-cresyl sulfate and indoxyl sulfate are associated with all-cause mortality in chronic kidney disease patients 71.

Multiple studies have attempted to reduce toxic metabolite production by inhibiting bacterial enzymes such as tryptophanase which drives the production of indoxyl sulfate from tryptophan 72, 73. This has led to some probiotic clinical trails with variable results 74. For example, the usage of the prebiotic oligofructose-enriched inulin in hemodialysis patients reduced the level of p-cresyl sulfate 71. In another clinical trial, chronic kidney disease patients taking synbiotics saw a reduction in their levels of p-cresyl sulfate 75.

4. Preventing Adverse Effects of Treatments on the Microbiome

A second class of MAE involves changes to the microbiome caused by a treatment (Figure 2). Much research focuses on the idea of ‘dysbiosis’, the notion that certain configurations of a microbiome are ‘unhealthy’ in a general sense. It is not yet clear how useful this notion is; perhaps we have yet to discover the precise mechanisms which drive these links, or perhaps the ‘healthiness’ of a microbiome is specific to a pathology and an individual. Regardless, many medical interventions are thought to have harmful effects on the microbiome. The MAE in this category involve a direct perturbation to the microbiome which then results in downstream effects, and the goal of mitigation is to prevent or reverse these perturbations. Perhaps the most well known example of this is the effects of long-term antibiotics usage and the observation that many non-antibiotic compounds have antibacterial properties, the implications of which are not well understood 76. However, this has been discussed extensively in other reviews, and here we focus on other treatments 77, 78.

Cancer

Radiation is commonly used to treat cancer, but most patients experience side effects such as gastrointestinal damage, reducing the quality of care. Many of these sequelae are mediated by systemic immune responses from radiation, and due to the relationship between the microbiome and the immune system, researchers have long hypothesized that one’s microbiome composition affects susceptibility to these side-effects 79.

The converse, that radiation affects the microbiome by altering the community structure, has been shown 28, 80. The effects of radiation on the microbiome can themselves promote intestinal damage. Gerassy-Vainberg et al. colonised germ-free mice with microbiota from radiation-treated mice and found that colonized mice had elevated intestinal levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNFα. They hypothesized that the microbiome mediates radiation sensitivity by altering these cytokine levels 81. Colonized mice were more susceptible to damage if they received radiation, suggesting that radiation can alter the microbiome leading to further effects independent from the initial insult.

The observation that the microbiome mediates some aspects of radiation-induced adverse responses has prompted investigation into the use of probiotics to mitigate these sequelae by helping reestablish a healthy microbiome. A 2017 meta-analysis by Liu et al. spanning 6 studies and 917 participants investigated the efficacy of probiotics and found a small protective effect against radiation-induced diarrhea 82. However, although the study found a statistically significant relative risk (RR) of .55 of diarrhea when given probiotics, they found no significant changes in the frequency of anti-diarrheal medication usage or the consistency of stool between probiotic and control groups. However, the study protocols were highly heterogenous In particular, the study with the lowest mean change in RR for any of the statistical endpoints also used the smallest dose of probiotics, on the order 108colony forming units (CFU) compared to 109– 1012CFU in the other studies 83. Additionally, the individual studies varied in the time at which endpoints were measured. For example, Demers et al. measured endpoints every day and generated survival curves which showed no significant difference in diarrhea incidence between test and control groups until at least 4 weeks post-treatment 84. None of the studies assayed the microbiome itself, thus one cannot comment on whether the probiotic had an effect on the microbiome specifically. If it could be shown that successful microbe engraftment, or permanent residency in the microbiome, is a pre-requisite for preventing radiation-induced diarrhea, then the focus of research could shift from asking if probiotics are useful here to what the optimal dosing / administration / composition formulation is for successful engraftment.

The engraftment hypothesis is supported by evidence from fecal transplant experiments which have shown that FMT can protect against radiation-induced side effects. In 2017, Cui et al. showed that fecal transplant from non-irradiated mice to radiation treated mice restored normal intestinal histology and gene expression and reduced toxicity without impairing treatment effectiveness 85. The next step is to determine if these results are relevant to patients. A 2018 pilot study examined FMT to patients experiencing chronic radiation enteritis, a syndrome characterized by intestinal complications lasting for more than three months post-radiation 86. The transplant successfully treated 3 out of the 5 patients with minimal adverse events, but much more testing is required to validate and refine this technique. In particular we must understand why FMT was effective in some, but not all patients, and how that knowledge could be used to improve the efficacy of FMT.

Immunotherapy Immunotherapeutics are also known to interact with the microbiome. Commensal Bifidobacterium was found to enhance the efficacy of PDL-1 inhibitors in mice 87, and a link between the microbiome and PDL-1 inhibitor effectiveness has also been shown in humans 88–90. In particular, FMT from patients who responded to treatment into germ-free mice was able to transfer this effect the recipient mice were more responsive to PDL-1 blockade than mice receiving FMT from non-responders 88.

We also indirectly know that a damaged microbiome can worsen outcomes by means of antibiotic studies. A cohort study by Pinato et al. found that antibiotic treatment in the weeks before immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment significantly worsened outcomes 91. However, the timing of antibiotic administration may also be important; the same study found that antibiotics administered concurrently with immunotherapy did not have worsened outcomes. Antibiotics have also been found to reduce the effectiveness of PDL-1 inhibitors 89 and in immunotherapuetics for renal cancer 92, 93, non small-cell lung cancer 92, 94, and melanoma 93.

Unfortunately, microbiome based mitigation techniques have so far been unsuccessful here. For example, a clinical trial evaluating prophylactic treatments for the tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor dacomitinib found no significant benefits from probiotics, although the antibiotic doxycline was effective in reducing side-effects 95.

Moreover, there is evidence that microbiome engineering can actually worsen immunotherapy outcomes 91, 96. For example, the observation that pre-treatment microbiome composition correlates with responsiveness to nivolumab, an immunotherapeutic used for melanoma, the MCGRAW clinical trial was established to examine the effects of probiotic supplementation prior to immnotherapy 88, 97. Although the study is not to complete until 2022, preliminary results have found that probiotics paradoxically worsen outcomes and are associated with a 70% lower chance of treatment response. Moreover, probiotic usage with nivolumab was associated with reduced microbiome diversity 98. In order to resolve this paradox, we need research to separate causal relationships from correlations; most likely the methods tried so far have engineering the wrong microorganisms, and we need to understand the true causal links here to identify how to solve this problem.

Surgery

Surgery is an intense and invasive process which can have numerous complications and surgical teams take preemptive measures to reduce risk of complications. In the case of intestinal surgery, antibiotic pretreatment has long been commonly used with the goal of decontaminating the colon to reduce the risk of post-operative infection. This procedure, known as mechanical bowel prep, has come under question in recent years due to advancements in surgical technique and an understanding of the ill effects of antibiotic abuse 99. A large multi-centre trial called MOBILE recently took place in Finland to evaluate the effect of mechanical bowel prep on relative risk of infections at the site of colon surgery and found no overall significant difference 100. We could conclude from this that surgical preparation is unnecessary, but complications are still a reality for many patients - this data suggests we require better preparation modalities.

There is evidence that the microbiome plays a role in physiological processes such as wound repair 101, implying that it could be an important tool in better preparation for surgery. Buoyed by these findings, clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics for reducing surgical complications, and the results have been promising. A recent meta-analysis by Chowdhury et al. evaluated the efficacy of probiotic and synbiotic surgical preparation for adbominal surgery across 34 trials and found an average risk reduction of .56 for post-surgical infections 102. Notably the microbiome also plays a role in susceptibility to sepsis 103.

5. Research Considerations for Microbial Adverse Event Mitigation

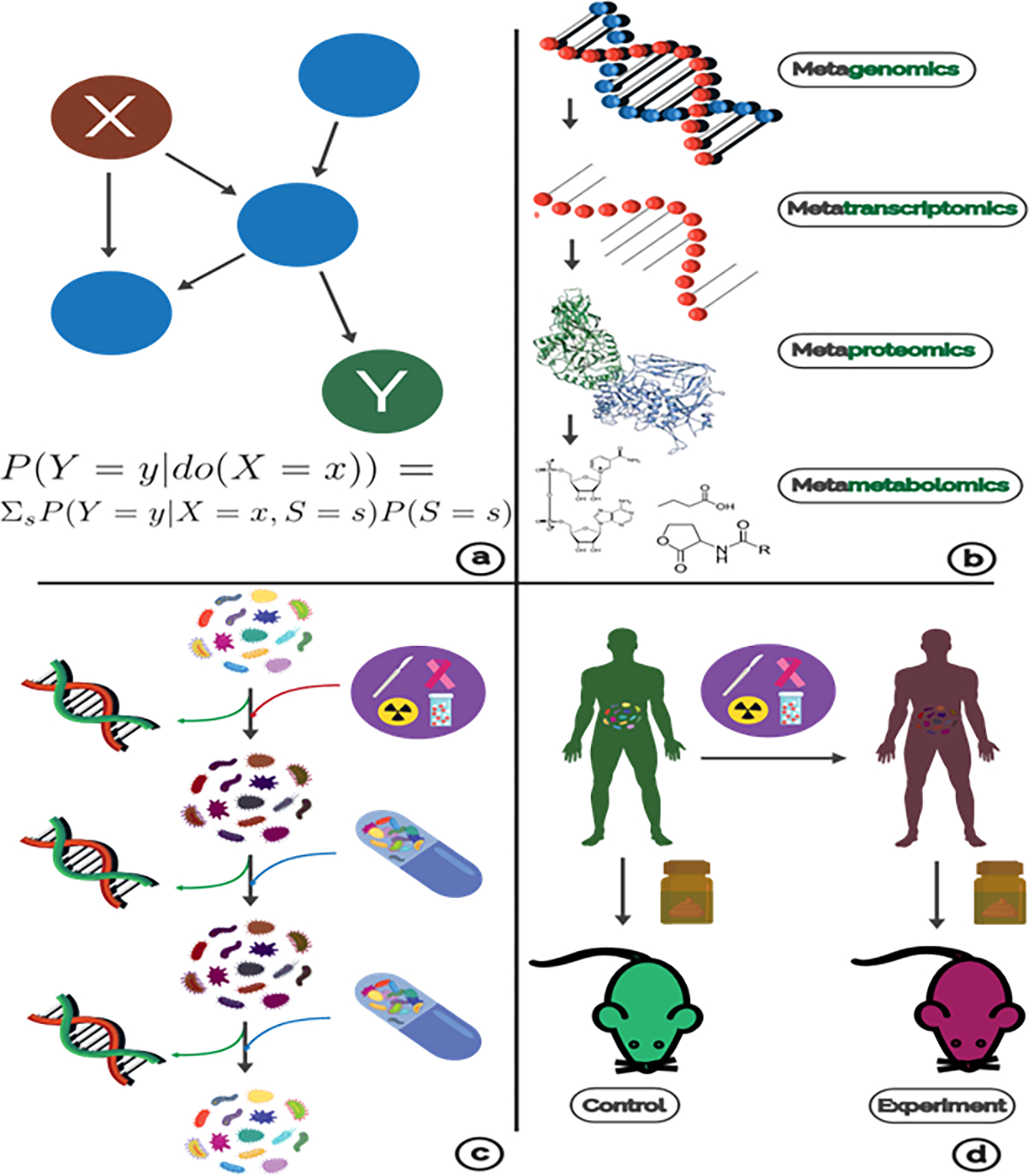

Research on preventing and mitigating microbial adverse interactions is just beginning, and we envision a great deal of basic science, translational, and clinical work to take place over the next decade in this direction. The breadth of this topic makes it difficult to prescribe a single strategy that researchers can follow in this field; we instead propose a set of guidelines to promote rigor and reproducibility when developing such therapies (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Strategies in MAE Research.

(a) Probabilistic graphical models are used to study causal relationships. The coloration and formula depict the effect of an intervention in variable X on Y. (b) Each omics modality assays a different level of microbiome function. (c) In order to understand how treatments and mitigations affect the microbiome, we must use meta-omics throughout a study. In this example, probiotics did not have an affect until a second dose, and without meta-omic readouts, we could not differentiate if the success/failure of the trial was due to ineffective engineering or because of an absence of a causal microbiome relationship. (d ) A common experiment to demonstrate causality for MAE is to use FMT to ‘transfer’ microbiomes to a germ-free mouse which should also transfer some negative phenotype.

Statistical Modeling

Mitigating MAE will require a shift in how we study the microbiome from a focus on statistical associations. For an engineering modality to be useful, there must have been a causal relationship involving the microbiome and the adverse event, and inferring these relationships must be the goal of future research. Moreover, showing that the mitigation strategy was effective is itself a demonstration of a causal effect.

Much of this research is clinical, forcing us to make these inferences from observational data. Causal inference from observations is a difficult task, but one that has been long studied in statistics and has been used in epidemiology and genomics disciplines as well 104–106. The most common methods involve probabilistic graphical models where edges represent causal relationships between entities. There are many algorithms for inferring these models and this have been extensively discussed elsewhere in the literature 107, 108.

Recently, there have been efforts to apply these techniques to the microbiome. Sazal et al. used interventional calculus to derive causal relationships between individual taxa and effects of antibiotics 109, which they proposed as a general method for quantifying the effects of microbiome perturbations. Unfortunately, their approach requires data on the order of thousands of samples due to high dimensionality, making it non-feasible for most microbiome projects currently. There have also been efforts to use time-series analysis methods to infer microbiome networks, but these suffer from similar challenges 110, 111.

To enable statistical inference from smaller datasets, one could try to simplify the problem space. For example, Surana and Kasper deliberately co-housed mice in an experiment studying the effects of the microbiome on colitis in order to limit the range of community structures and make inference easier 112. Alternatively, one could try combining data across multiple studies to increase the size of a dataset, but this is fraught with its own issues; combining heterogenous data introduces statistical artifacts, and experimental conditions can vary dramatically 113, 114. Another solution is to simplify the representation of a microbiome by embedding it into a low-dimensional space or clustering structurally similar microbiomes together, but the generalizability of these methods to different environments is not yet clear 115, 116. Thus, finding robust and practical ways to perform causal inference in the microbiome is still an open problem.

5.2. ‘Omics as a basis for MAE Research

Data problems are further compounded by the diversity of engineering modalities available. If one study used a particular probiotic formulation, can its results inform a future study using a different formulation? Can results from a fecal transplant study help us design a more precise therapy which could replicate those effects? To address these questions, there must be some common ground across modalities, and ‘omics techniques are a natural and reasonably accessible common ground. Instead of asking if a fecal transplant mitigated an adverse phenomenon, one could ask if the community perturbation caused by the transplant was associated with a reduction in event severity. Framing the question this way decouples the task of achieving a desired effect on the microbiome from that of determining what microbial functions need to be modulated to prevent an MAE.

Many clinical trials evaluating the effect of probiotics and FMT on some endpoint have failed to quantify the microbiome pre, during, and post-treatment, and as a result, one cannot assess the specific role the microbiome played in these studies. Quantifying a patient’s microbiome could let us compare different engineering modalities by using the effect of the treatment on the microbiome as a common basis.

The most popular ‘omics quantification is sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA subunit. 16S sequencing is a relatively cheap and simple way to characterize the relative abundance of organisms in a microbiome but can miss potentially important details about the community structure (120). To identify individual species and genes, one must use whole-community shotgun sequencing (WCS) 117 which is more accurate for detecting community structure 118. WCS is more expensive, but as sequencing costs have fallen over time, it is becoming increasingly popular 119. Thus, we recommend researchers 1) use WCS and 2) collect samples temporally throughout a study to facilitate causal inference.

Additionally, there are analytic methods that go beyond species abundance which may be appropriate depending on the MAE under investigation. Specifically, RNA expression sequencing, proteomics, and tandem mass spectrometry are high-throughput means to quantify the actual expression of individual genes, proteins, and metabolites 120–122. If the MAE being mitigated involves a known mechanism such as the β-glucuronidases, then these methods should be used to quantify the actual function under consideration. Lastly, the host genotype should also be considered in order to integrate information about pharmacogenomics and pharamacomicrobiomics. More studies are taking a multi-omic approach and incorporating multiple sequencing modalities, from metagenomic to epigenetic and host genomics 14, 123. As more of these studies are conducted, the integration of these modalities across a large number of data points will enable us to elucidate the mechanisms underlying various MAE and identify novel mitigation strategies.

Model systems to assess the role of the microbiome in adverse events

A common task in microbiome research is to demonstrate that a phenotype, such as an adverse event, can be reproduced by transferring a causative microbial community to a new host. In the context of MAE, experiments could include demonstrating that an irradiated or chemotherapy-treated microbiome when transferred to another host confers susceptibility to radiation and chemotherapy associated sequelae. Most commonly phenotype transfer studies are done in humanized mouse models using fecal transplant. These are germ-free mice (meaning mice with bacteria eliminated from their GI tracts and housed in a sterile environment) which are inoculated with microbes from an experimentally treated mouse or human patient. A commentary by Walter et al. recently argued that the success rate of phenotype transfer in humanized rodents is suspiciously high (95%) and questioned the validity of inferring causality from these experiments 124. We note that it is key to choose a model organism or system with features most closely relevant to the type of MAE under consideration. For example, we know that response to radiation is largely mediated by the immune-system. Thus, the model system for adverse effects of radiation via the microbiome should be chosen with an eye towards the similarity of the host immune system to our own. On the other hand, enzyme-mediated processes such as L-DOPA deactivation or irinotecan metabolism could in principle be studied in a simpler system. Numerous reviews cover the strengths and limitations of animal models for the microbiome in the context of drug metabolism 125 and for microbiome research generally 126–128.

6. Conclusion: Adverse Events Mitigation as Personalized Medicine

Adverse events are, almost always, a personalized phenomenon. Not everyone will develop adverse side-effects from a treatment, and the nature of these events can vary broadly 129. There is a body of research in pharmacology that seeks to identify individual risk factors, such genomic variants, to predict the likelihood for adverse events before administering a treatment 130. A similar approach could be used for microbial adverse event mitigation. If we understand that a patient is at high risk for developing side effects from or not responding to a treatment based on their microbiome, then we could potentially adjust the dose, choose a different treatment, or supplement them with probiotics to mitigate the event. Thus, the first step to mitigating MAE is to actually predict them. Our microbiomes are tightly connected to our physiology, immunology, diet, and lifestyle, and these indirect relationships could help in predicting MAEs 18. Indeed, many studies have shown that age, health status, and specific diseases can be predicted from one’s microbiome data 18, 131–134 (see sidebar). Each of the strategies we discuss in this review will benefit from improved prediction approaches to avoid giving patients probiotics and prebiotics that are unlikely to work for them and to focus our resources on patients who are at most risk.

The early-stage nature of this work is exciting and humbling. We have the opportunity to improve outcomes across many treatment modalities by engineering our microbiomes to favor a beneficial response. On the other hand, the caveats are enormous. Many existing studies are limited by small sample sizes, which lead to batch effects, and temporal data, essential for causal inference, is not routinely available. Thus, much of our understanding about MAE is subject to change, including to what extent the microbiome plays a role in adverse events relative to traditional pharmacogenomic factors. Additionally, our understanding of microbiome community structure dynamics is also in an early stage, limiting our ability to 1) predict the effect of an engineered perturbation and 2) to precisely achieve a desired perturbation. Despite these caveats, the MAE field is exciting because of its potential impact and because of its interdisciplinary nature; experimental biology, mathematics, data science, and clinical investigation all come together here to address a common problem, and as a result, we believe that this field is ripe for innovation.

7. Summary Points

Microbiome adverse events (MAE) are a two-way street. Medical interventions can both perturb the microbiome and be adversely modified by it.

Microbiome engineering is in a very early stage. Many interventions, such as probiotics, can fail to actually achieve a significant perturbation to the native microbiome, and this should be kept in mind when evaluating MAE research.

Researchers should employ regular meta-omic sampling when conducting experiments and clinical trials. ‘Omics provides a common basis for interpreting MAE research, and in particular is essential for understanding causal relationships between interventions and the microbiome.

Animal models should be carefully considered when studying MAE. Humanizedmice may not always be the most appropriate model system.

MAE is an inherently personalized phenomenon and hence requires a personalized approach to diagnose and mitigate.

8. Future Issues

Microbiome adverse events (MAE) are a two-way street. Medical interventions can both perturb the microbiome and be adversely modified by it.

Microbiome engineering is in a very early stage. Many interventions, such as probiotics, can fail to actually achieve a significant perturbation to the native microbiome, and this should be kept in mind when evaluating MAE research.

Researchers should employ regular meta-omic sampling when conducting experiments and clinical trials. ‘Omics provides a common basis for interpreting MAE research, and in particular is essential for understanding causal relationships between interventions and the microbiome.

Animal models should be carefully considered when studying MAE. Humanized mice may not always be the most appropriate model system.

MAE is an inherently personalized phenomenon and hence requires a personalized approach to diagnose and mitigate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Saad Khan and Ruth Hauptman were supported by the Einstein Medical Scientist Training Program (2T32GM007288-45); Saad Khan is additionally supported by an NIH T32 fellowship on Geographic Medicine and Emerging Infectious Diseases (2T32AI070117-13). Libusha Kelly is supported in part by a Peer Reviewed Cancer Research Program Career Development Award from the United States Department of Defense (CA171019).

9 DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

References

- 1.Team, N. (2007).

- 2.Hitchings R & Kelly L Predicting and Understanding the Human Microbiome’s Impact on Pharmacology. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 40, 495–505 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spanogiannopoulos P, Bess EN, Carmody RN & Turnbaugh PJ The microbial pharmacists within us: a metagenomic view of xenobiotic metabolism. Nature Reviews Microbiology 14, 273–287 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guthrie L, Wolfson S & Kelly L (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebeer S & Spacova I Exploring human host-microbiome interactions in health and disease-how to not get lost in translation. Genome Biology 20 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sousa T et al. The gastrointestinal microbiota as a site for the biotransformation of drugs. Abdul W Review Netherlands International journal of pharmaceutics Int J Pharm 363, 1–25 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nichols RG, Peters JM & Patterson AD Interplay Between the Host, the Human Microbiome, and Drug Metabolism. Human Genomics 13, 27–27 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guthrie L, Gupta S, Daily J & Kelly L Human microbiome signatures of differential colorectal cancer drug metabolism. Biofilms and Microbiomes 3 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace BD, Wang H, Lane KT, Scott JE & Orans J Alleviating cancer drug toxicity by inhibiting a bacterial enzyme. Science 330, 831–835 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wallace BD, Roberts AB, Pollet RM, Ingle JD & Biernat KA Structure and Inhibition of Microbiome β-Glucuronidases Essential to the Alleviation of Cancer Drug Toxicity. Chemistry and Biology 22, 1238–1249 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iizumi T, Battaglia T, Ruiz V, Perez P & G I. Gut Microbiome and Antibiotics. Archives of Medical Research 48, 727–734 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB & Button JE Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 505, 559–563 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lloyd-Price J, Abu-Ali G & Huttenhower C The healthy human microbiome. Genome Medicine 8, 51–51 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothschild D, Weissbrod O, Barkan E, Kurilshikov A & Korem T Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 555, 210–215 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachmann R, Leonard D, Delzenne N, Kartheuser A & Cani PD Novel insight into the role of microbiota in colorectal surgery. Gut 66, 738–749 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sokol H & Adolph TE The microbiota: an underestimated actor in radiation-induced lesions? Gut 67, 1–2 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma A, Buschmann MM & Gilbert JA Pharmacomicrobiomics: The Holy Grail to Variability in Drug Response? Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 106, 317–328 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peiffer-Smadja N, Delli’ere S, Rodriguez C, Birgand G & Fx L Machine learning in the clinical microbiology laboratory: has the time come for routine practice? Clinical Microbiology and Infection (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee HL, Shen H, Hwang IY, Ling H & Yew WS Targeted approaches for in situ gut microbiome manipulation. Genes 9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inda ME, Broset E, Lu TK & Fuente-Nunez CDL Emerging Frontiers in Microbiome Engineering. Trends in Immunology 40, 952–973 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angulo MT, Moog CH & Liu YY A theoretical framework for controlling complex microbial communities. Nature Communications 10, 1–12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawson CE, Harcombe WR, Hatzenpichler R, Lindemann SR & offler FEL Common principles and best practices for engineering microbiomes. Nature Reviews Microbiology 17, 725–741 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ronda C, Chen SP, Cabral V, Yaung SJ & Wang HH Metagenomic engineering of the mammalian gut microbiome in situ. Nature Methods 16, 167–170 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam KN, Alexander M & Turnbaugh PJ Precision Medicine Goes Microscopic: Engineering the Microbiome to Improve Drug Outcomes. Cell Host and Microbe 26, 22–34 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maini RV, Bess E, Bisanz J, Turnbaugh P & Balskus E Discovery and inhibition of an interspecies gut bacterial pathway for Levodopa metabolism. Science 364 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haiser HJ et al. Predicting and manipulating cardiac drug inactivation by the human gut bacterium Eggerthella lenta. Science 341, 295–303 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koppel N, Bisanz JE, Pandelia ME, Turnbaugh PJ & Balskus EP (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreira MR, Andreyev H, Mohammed K, Truelove L & Gowan SM Microbiotaand radiotherapy-induced gastrointestinal side-effects (MARS) study: A large pilot study of the microbiome in acute and late-radiation enteropathy. Clinical Cancer Research 25, 6487–6500 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millan B, Laffin M & Madsen K Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: Beyond Clostridium difficile. Current Infectious Disease Reports 19, 19–22 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Youngster I et al. Oral, Capsulized, Frozen Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Relapsing Clostridium difficile Infection. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 312, 1772–1778 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirsch BE et al. Effectiveness of fecal-derived microbiota transfer using orally administered capsules for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. BMC Infectious Diseases 15, 1–9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kao D, Roach B, Silva M, Beck P & Rioux K Effect of oral capsulevs colonoscopy- delivered fecal microbiota transplantation on recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 318, 1985–1993 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allegretti JR, Korzenik JR & Hamilton MJ Fecal microbiota transplantation via colonoscopy for recurrent C. difficile infection. Journal of Visualized Experiments 1–6 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverman MS, Davis I & Pillai DR Success of Self-Administered Home Fecal Transplantation for Chronic Clostridium difficile Infection. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tariq R, Pardi DS, Bartlett MG & Khanna S Low cure rates in controlled trials of fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent clostridium difficile infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 68, 1351–1358 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson BC, Vatanen T, Cutfield WS & O’sullivan JM The super-donor phenomenon in fecal microbiota transplantation. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 9, 1–11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groot PD, Scheithauer T, Bakker GJ, Prodan A & Levin E (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Important Safety Alert Regarding Use of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation and Risk of Serious Adverse Events (2020). URL https://fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics/important-safetyalert-regarding-use-fecal-microbiota-transplantation-and-risk-serious-adverse.

- 39.Duvallet C et al. Framework for rational donor selection in fecal microbiota transplant clinical trials. PLoS ONE 14, 1–18 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Net M, Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G & Gibson GR The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 11, 506–514 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simpson HL & Campbell BJ Review article: Dietary fibre-microbiota interactions. Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 42, 158–179 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gibson GR, Hutkins R, Sanders ME, Prescott SL & Reimer RA Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology 14, 491–502 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schrezenmeir J, Vrese D & Probiotics M, prebiotics, and synbiotics - Approaching a definition. In American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 73 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suez J, Zmora N, Segal E & Elinav E The pros, cons, and many unknowns of probiotics. Nature Medicine (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Didari T, Solki S, Mozaffari S, Nikfar S & Abdollahi M A systematic review of the safety of probiotics. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 13, 24405164–24405164 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quin C et al. Probiotic supplementation and associated infant gut microbiome and health: A cautionary retrospective clinical comparison. Scientific Reports 8, 1–16 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Steidler L, Hans W, Schotte L, Neirynck S & Obermeier F Treatment of murine colitis by Lactococcus lactis secreting interleukin-10. Science 289, 1352–1355 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwang IY, Koh E, Wong A, March JC & Bentley WE Engineered probiotic Escherichia coli can eliminate and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa gut infection in animal models. Nature Communications 8, 1–11 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mimee M, Nadeau P, Hayward A, Carim S & Flanagan S An ingestible bacterialelectronic system to monitor gastrointestinal health. Science 360, 915–918 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abedon ST, Kuhl SJ, Blasdel BG & Kutter EM Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage 1, 66–85 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paule A, Frezza D & Edeas M Microbiota and Phage Therapy: Future Challenges in Medicine. Medical Sciences 6, 86–86 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henein A What are the limitations on the wider therapeutic use of phage. Bacteriophage 3, 24872–24872 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pizarro-Bauerle J & Ando H Engineered Bacteriophages for Practical Applications. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin 43, 240–249 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dunne M, Rupf B, Tala M, Qabrati X & Ernst P Reprogramming Bacteriophage Host Range through Structure-Guided Design of Chimeric Receptor Binding Proteins. Cell Reports 29, 1336–1350 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schooley RT, Biswas B, Gill JJ, Hernandez-Morales A & Lancaster J Development and use of personalized bacteriophage-based therapeutic cocktails to treat a patient with a disseminated resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 61, 1–14 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, Russell DA & Ford K Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant mycobacterium abscessus. Nature Medicine 25, 730–733 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmitt FC, Brenner T, Uhle F, Loesch S & Hackert T Gut microbiome patterns correlate with higher postoperative complication rates after pancreatic surgery 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1103 Clinical Sciences. BMC Microbiology 19, 1–13 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katzung BG (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pollet RM et al. An Atlas of βGlucuronidases in the Human Intestinal Microbiome. Structure 25, 967–977 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boucher JG, Boudreau A, Ahmed S & Atlas E (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dashnyam P, Mudududdla R, Hsieh TJ, Lin TC & Lin HY β-Glucuronidases of opportunistic bacteria are the major contributors to xenobiotic-induced toxicity in the gut. Scientific Reports 8, 1–12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sakamoto H, Yokota H, Kibe R, Sayama Y & Yuasa A Excretion of bisphenol Aglucuronide into the small intestine and deconjugation in the cecum of the rat. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta General Subjects 1573, 171–176 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.The intestinal microbiome and estrogen receptor-positive female breast cancer. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Awolade P et al. Therapeutic significance of β-glucuronidase activity and its inhibitors: A review. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 187, 111921–111921 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng KW, Tseng CH, Tzeng CC, Leu YL & Cheng TC Pharmacological inhibition of bacterial β-glucuronidase prevents irinotecan-induced diarrhea without impairing its antitumor efficacy in vivo. Pharmacological Research 139, 41–49 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Loguidice A, Wallace BD, Bendel L, Redinbo MR & Boelsterli UA Pharmacologic targeting of bacterial β-glucuronidase alleviates nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteropathy in mice. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 341, 447–454 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Emami AH, Sadighi S, Shirkoohi R & Mohagheghi MA Prediction of Response to Irinotecan and drug toxicity based on pharmacogenomics test: A prospective case study in advanced colorectal cancer. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 18, 2803–2807 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Whitfield A, Moore B & Daniels R Classics in chemical neuroscience: levodopa. ACS Chem Neurosci 5, 1192–1199 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van KS & El AS Contributions of Gut Bacteria and Diet to Drug Pharmacokinetics in the Treatment of Parkinson’s. Disease. Front Neurol 10, 1087–1087 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clayton TA, Baker D, Lindon JC, Everett JR & Nicholson JK Pharmacometabonomic identification of a significant host-microbiome metabolic interaction affecting human drug metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106, 14728–14761 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meijers B et al. p-Cresyl sulfate serum concentrations in haemodialysis patients are reduced by the prebiotic oligofructoseenriched inulin. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25, 219–224 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tsuyoshi S, Yuji N, Koji M, Naomi T & Taichi F (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tsuyoshi S, Hiroki S, Koji M, Naomi T & Taichi F (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen YY, Chen DQ, Chen L, Liu JR & Vaziri ND Microbiome-metabolome reveals the contribution of gut-kidney axis on kidney disease. Journal of translational medicine 17, 5–5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rossi M, Johnson DW, Morrison M, Pascoe EM & Coombes JS Synbiotics easing renal failure by improving gut microbiology (SYNERGY): A randomized trial. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 11, 223–231 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, Zeller G & Telzerow A Extensive impact of nonantibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 555, 623–628 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Aslam B, Wang W, Arshad MI, Khurshid M & Muzammil S Antibiotic resistance: a rundown of a global crisis. Infection and Drug Resistance 11, 1645–1658 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zaman SB et al. A Review on Antibiotic Resistance: Alarm Bells are Ringing. Cureus (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang S, Wang Q, Zhou C, Chen K & Chang H Colorectal cancer, radiotherapy and gut microbiota. Chinese Journal of Cancer Research 31, 212–222 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Blanarova C, Galovicova A & Petrasova D Use of probiotics for prevention of radiationinduced diarrhea. Bratislava Medical Journal 110, 98–104 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gerassy-Vainberg S, Blatt A, Danin-Poleg Y, Gershovich K & Sabo E Radiation induces proinflammatory dysbiosis: transmission of inflammatory susceptibility by host cytokine induction. Gut 67, 97–107 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liu MM, Li ST, Shu Y & Zhan HQ Probiotics for prevention of radiation-induced diarrhea: A meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 12, 1–15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Giralt J, Regadera JP, Verges R, Romero J & Fuente IDL Effects of Probiotic Lactobacillus Casei DN-114 001 in Prevention of Radiation-Induced Diarrhea: Results From Multicenter, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Nutritional Trial. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics 71, 1213–1219 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Demers M, Dagnault A & Desjardins J A randomized double-blind controlled trial: Impact of probiotics on diarrhea in patients treated with pelvic radiation. Clinical Nutrition 33, 761–767 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cui M, Xiao H, Li Y, Zhou L & Zhao S Faecal microbiota transplantation protects against radiation-induced toxicity. EMBO Molecular Medicine 9, 448–461 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ding X, Li Q, Li P, Chen X & Xiang L Fecal microbiota transplantation: A promising treatment for radiation enteritis. Radiotherapy and Oncology (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sivan A, Corrales L, Hubert N, Williams J & Aquino-Michaels K Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 350, 1084–1093 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gopalakrishnan V, Spencer C, Nezi L, Reuben A & Andrews M Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 359, 97–103 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Routy B et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 359, 91–97 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ahmed J, Kumar A, Parikh K, Anwar A & Knoll BM Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics impacts outcome in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. OncoImmunology 7, 1–6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pinato DJ, Howlett S, Ottaviani D, Urus H & Patel A Association of prior antibiotic treatment with survival and response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncology 5, 1774–1778 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M, Halpenny D & Fidelle M Negative association of antibiotics on clinical activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced renal cell and non-small-cell lung cancer. Annals of Oncology 29, 1437–1444 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tinsley N, Zhou C, Tan G, Rack S & Lorigan P Cumulative Antibiotic Use Significantly Decreases Efficacy of Checkpoint Inhibitors in Patients with Advanced Cancer. The Oncologist 25, 55–63 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hakozaki T, Okuma Y, Omori M & Hosomi Y Impact of prior antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab for non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology Letters 17, 2946–2952 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lacouture M, Keefe D, Sonis S, Jatoi A & Gernhardt D A phase II study (ARCHER 1042) to evaluate prophylactic treatment of dacomitinib-induced dermatologic and gastrointestinal adverse events in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Annals of Oncology 27, 1712–1718 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yan C, Tu XX, Wu W, Tong Z & Liu LL Antibiotics and immunotherapy in gastrointestinal tumors: Friend or foe? World Journal of Clinical Cases 7, 1253–1261 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Melanoma checkpoint and gut microbiome alteration with microbiome intervention. (2019). URL https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03817125.

- 98.Probiotics linked to poorer response to cancer immunotherapy in skin cancer patients. (2019). URL https://www.parkerici.org/the-latest/probioticslinked-to-poorer-response-to-cancer-immunotherapy-in-skin-cancer-patients.

- 99.Alverdy JC & Shogan BD Preparing the bowel for surgery: rethinking the strategy. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology 16, 708–709 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Koskenvuo L, Lehtonen T, Koskensalo S, Rasilainen S & Klintrup K Mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel preparation versus no bowel preparation for elective colectomy (MOBILE): a multicentre, randomised, parallel, single-blinded trial. The Lancet 394, 840–848 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Scales BS & Huffnagle GB The microbiome in wound repair and tissue fibrosis. Journal of Pathology 229, 323–331 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chowdhury AH, Adiamah A, Kushairi A, Varadhan KK & Krznaric Z Perioperative Probiotics or Synbiotics in Adults Undergoing Elective Abdominal Surgery. Annals of Surgery XX 1–1 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Haak BW & Wiersinga WJ The role of the gut microbiota in sepsis. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2, 135–143 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pearce N & Lawlor DA Causal inference-so much more than statistics. International Journal of Epidemiology 45, 1895–1903 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Glass TA, Goodman SN, an MAH & Samet JM Causal Inference in Public Health. Annual Review of Public Health 34, 61–75 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pingault JB et al. Using genetic data to strengthen causal inference in observational research. Nature Reviews Genetics 19, 566–580 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Maathuis MH & Nandy P (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 108.Glymour C, Zhang K & Spirtes P Review of causal discovery methods based on graphical models. Frontiers in Genetics 10, 1–15 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sazal MR, Stebliankin V, Mathee K & Narasimhan G (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mainali K, Bewick S, Vecchio-Pagan B, Karig D & Fagan WF Detecting interaction networks in the human microbiome with conditional Granger causality. PLoS computational biology 15, 1007037–1007037 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dohlman AB & Shen X Mapping the microbial interactome: Statistical and experimental approaches for microbiome network inference. Experimental Biology and Medicine 244, 445–458 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Surana NK & Kasper DL Moving beyond microbiome-wide associations to causal microbe identification. Nature 552, 244–247 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li SJ, Jiang H, Yang H, Chen W & Peng J The dilemma of heterogeneity tests in meta-analysis: A challenge from a simulation study. PLoS ONE 10, 1–9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Imrey PB Limitations of Meta-analyses of Studies With High Heterogeneity. JAMA network open 3, 1919325–1919325 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Costea PI, Hildebrand F, Manimozhiyan A, ackhed FB & Blaser MJ Enterotypes in the landscape of gut microbial community composition. Nature Microbiology 3, 8–16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tataru CA & David MM Decoding the Language of Microbiomes: Leveraging Patterns in 16S Public Data using Word-Embedding Techniques and Applications in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. bioRxiv (2019). URL 10.1101/748152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Quince C, Walker AW, Simpson JT, Loman NJ & Segata N Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nature Biotechnology 35, 833–844 (2017). URL 10.1038/nbt.3935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Laudadio I et al. Quantitative Assessment of Shotgun Metagenomics and 16S rDNA Amplicon Sequencing in the Study of Human Gut Microbiome. OMICS A Journal of Integrative Biology 22, 248–254 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jovel J et al. Characterization of the gut microbiome using 16S or shotgun metagenomics. Frontiers in Microbiology 7, 1–17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kolmeder C, ahteenmäki KL, Wacklin P, Kotovuori A & Ritamo I. Tandem mass spectrometry in resolving complex gut microbiota functions. In MALDI-TOF and Tandem MS for Clinical Microbiology (John Wiley & Sons, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bashiardes S, Zilberman-Schapira G & Elinav E Use of metatranscriptomics in microbiome research. Bioinformatics and Biology Insights 10, 19–25 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kleiner M Metaproteomics: Much More than Measuring Gene Expression in Microbial Communities. mSystems 4, 1–6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang Q et al. Host and microbiome multiomics integration: applications and methodologies. Biophysical Reviews 11, 55–65 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Walter J, Armet AM, Finlay BB & Shanahan F Establishing or Exaggerating Causality for the Gut Microbiome: Lessons from Human Microbiota-Associated Rodents. Cell 180, 221–232 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Guthrie L & Kelly L Bringing microbiome-drug interaction research into the clinic. EBioMedicine 44, 708–715 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Douglas AE Simple animal models for microbiome research. Nature Reviews Microbiology 17, 764–775 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nguyen T, Vieira-Silva S, Liston A & Raes J How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? Disease Models & Mechanisms 8, 1–16 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hugenholtz F & Vos WMD Mouse models for human intestinal microbiota research: a critical evaluation. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 75, 149–160 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wolfe D, Yazdi F, Kanji S, Burry L & Beck A Incidence, causes, and consequences of preventable adverse drug reactions occurring in inpatients: A systematic review of systematic reviews. PLoS ONE 13, 1–36 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Roden DM, Mcleod HL, Relling MV, Williams MS & Mensah GA Pharmacogenomics. The Lancet 394, 521–532 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Galkin F et al. (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ahadi S et al. Personal aging markers and ageotypes revealed by deep longitudinal profiling. Nature Medicine 26, 83–90 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Cuesta-Zuluaga JDL, Kelley ST, Chen Y, Escobar JS & Mueller NT Ageand Sex-Dependent Patterns of. Gut Microbial Diversity in Human Adults. mSystems 4, 1–12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Reiman D, Metwally AA & Dai Y (2018). [Google Scholar]