Abstract

One thousand one hundred and nineteen cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) Omicron variant cases have been diagnosed at the Institut Hospitalo‐Universitaire Méditerranée Infection, Marseille, France, between November 28, 2021, and December 31, 2021. Among the 825 patients with known vaccination status, 383 (46.4%) were vaccinated, of whom 91.9% had received at least two doses of the vaccine. Interestingly, 26.3% of cases developed SARS‐CoV‐2 infection within 21 days following the last dose of vaccine suggesting possible early production of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 facilitating antibodies. Twenty‐one patients have been hospitalized, one patient required intensive care, and another patient who received a vaccine booster dose died.

Keywords: coronavirus, COVID‐19, death, Delta, hospitalization, infection, Intensive Care Unit, Omicron, SARS‐CoV‐2, vaccination, variant

Highlights

Significantly low rates of hospitalization, transfer to Intensive Care Unit and death were observed in patients infected with Omicron as compared to those infected with Delta variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 during the same period,

26.3% of patients infected with Omicron get infected during the 3 weeks following COVID‐19 vaccination raising the question of facilitating antibodies.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to Santé publique France report on COVID‐19 released on December 30, 2021, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) Omicron variant (Pango lineage B.1.1.529) accounted for 62.4% of diagnoses at the country scale based on a compatible pattern of mutations detected by specific real‐time reverse‐transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) designed for variant screening. 1 Preliminary reports from Denmark and Norway have suggested that a large proportion of patients infected with the Omicron variant were fully vaccinated and experienced clinically‐mild infections. 2 , 3 The objective of this study was to describe the first 1119 Omicron cases diagnosed at the Institut Hospitalo‐Universitaire (IHU) Méditerranée Infection located in Marseille, France that manages the vast majority of patients in the area and to provide preliminary information on its severity.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Data source

We conducted a single‐center retrospective cohort study at IHU Méditerranée Infection, which is part of the network of public hospitals in Marseille (AP‐HM). All available SARS‐CoV‐2 positive results obtained by our laboratory between November 28, 2021 (the date of the first identification of the Omicron variant) and December 31, 2021, were reviewed. IHU Méditerranée Infection received patients or asymptomatic contacts directly presenting for SARS‐CoV‐2 testing or samples sent from other medical wards of AP‐HM (including temporarily dedicated COVID‐19 units and intensive care units (ICU), or from laboratories outside AP‐HM. Most of the positive patients sampled at IHU Méditerranée Infection were followed up in the day‐care hospital or were hospitalized in dedicated infectious disease units at IHU, according to the severity of the disease. When required, patients were transferred to ICU at AP‐HM.

2.2. Surveillance of SARS‐CoV‐2 and identification of variants

SARS‐CoV‐2 genotyping was performed from nasopharyngeal samples as previously described. 4 The Omicron variant was identified first by the absence of detection of amino acid substitutions L452R and P681R with TaqMan SARS‐CoV‐2 mutation assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and by positivity of ORF1 and N genes but negativity of the S gene with the TaqPath COVID‐19 kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). 4 , 5 Then, SARS‐CoV‐2 genomes were obtained and analyzed as previously described. 4 Briefly, next‐generation sequencing was performed using either the Illumina COVID‐seq protocol and the NovaSeq. 6000 instrument (Illumina Inc.) or the Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) and the GridION instrument (Oxford Nanopore Technologies Ltd.). Genome sequences were assembled by mapping on the SARS‐CoV‐2 genome GenBank accession no. NC_045512.2 (Wuhan‐Hu‐1 isolate) using Minimap2 (https://github.com/lh3/minimap2). 6 Samtools (https://www.htslib.org/) were used to soft clip primers (https://artic.network/) and remove sequence duplicates. 7 Consensus genomes were generated using Sam2consensus (https://github.com/vbsreenu/Sam2Consensus) through a first in‐house script written in Python language (https://www.python.org/). Mutation detection was performed with Nextclade web application (https://clades.nextstrain.org/) 8 and freebayes (https://github.com/freebayes/freebayes). 9 SARS‐CoV‐2 genotype was determined with a second in‐house Python script. Nextstrain clades and Pangolin lineages were determined using Nextclade and Pangolin web application (https://cov-lineages.org/pangolin.html), 10 respectively. Genome sequences were deposited in the GISAID sequence database (https://www.gisaid.org/). 11

2.3. Ethical statement

This research project was validated by the ethics committee of the Méditerranée Infection Institute under reference 2022‐001.

Access to the patients' biological and registry data issued from the hospital information system was approved by the data protection committee of Assistance Publique‐Hôpitaux de Marseille (AP‐HM) and was recorded in the European General Data Protection Regulation Registry under number RGPD/APHM 2019‐73.

3. RESULTS

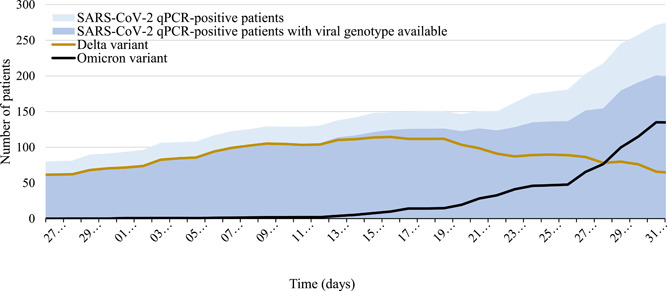

As per December 31, 2021, 1119 infections with the SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant have been diagnosed at IHU Méditerranée Infection. During the same period of time, 3075 infections with the SARS‐CoV‐2 Delta variant (B.1.617.2) have been diagnosed. The first Omicron case was diagnosed on November 28, 2021 (Figure 1), and the number of cases rapidly increased starting in mid‐December. Conversely, the number of Delta cases decreased after mid‐December. At the end of December, the number of Omicron cases exceeded that of Delta cases.

Figure 1.

Dynamic of diagnoses of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) infection by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and of Omicron and Delta variants between November 28, 2021, and December 31, 2021. Graphic represents the daily distribution of positive cases of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection diagnosed by qPCR (light blue), of cases for which SARS‐CoV‐2 genotype was obtained (dark blue), of infections with the Omicron variant (black), and of infection with the Delta variant (orange) at the Institut Hospitalo‐Universitaire Méditerranée Infection, Marseille, France, between November 28, 2021 and December 31, 2021

3.1. Demographics and clinical information

Demographics and clinical data retrospectively obtained from electronic medical files were anonymized before analysis (Table 1). The median age of the patients infected with the Omicron variant was 33 years, with more than 70% being younger than 50 years. About one‐quarter of the patients had a high viral load (qPCR cycle threshold value [C t] < 20). The vast majority of the patients were symptomatic (63.5%) and the hospitalization rate was low (1.9%) with a median age of 49 years among hospitalized patients. Only one 53‐year‐old male patient with an asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron infection was transferred to ICU because of a subarachnoid hemorrhage in relation to a ruptured Sylvian aneurysm. An 89‐year‐old woman with a history of hypertension who presented with fever, cough, and hypoxemia died. She had received three doses of the anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) Omicron and Delta variants from 28 November to 31 December 2021

| Omicron (N = 1119) | Delta (N = 3075) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | p value*** | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 611 | 54.6 | 1576 | 51.3 | 0.055 |

| Male | 508 | 45.4 | 1499 | 48.7 | |

| Median age (min−max) (years) | 33 (0−93) | 42 (0−100) | <0.0001 | ||

| Age range (years) | <0.0001 | ||||

| 0−9 | 31 | 2.8 | 129 | 4.2 | |

| 10−14 | 24 | 2.1 | 156 | 5.1 | |

| 15−19 | 78 | 7.0 | 124 | 4.0 | |

| 20−29 | 337 | 30.1 | 387 | 12.6 | |

| 30−39 | 207 | 18.5 | 559 | 18.2 | |

| 40−49 | 156 | 13.9 | 649 | 21.1 | |

| 50−64 | 50 | 4.5 | 638 | 20.7 | |

| ≥65 | 236 | 21.1 | 433 | 14.1 | |

| SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR C t value10 882 930 * | <0.0001 | ||||

| <10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10−19 | 289 | 26.6 | 1097 | 37.4 | |

| 20−29 | 702 | 64.5 | 1520 | 51.9 | |

| 30−34 | 97 | 8.9 | 313 | 10.7 | |

| Self‐reported symptoms8 962 305 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Symptomatic | 569 | 63.5 | 1788 | 77.6 | |

| Asymptomatic | 327 | 36.5 | 517 | 22.4 | |

| Hospitalization | 21 | 1.9 | 367 | 11.9 | <0.0001 |

| Transfer to intensive care unit | 1 | 0.1 | 94 | 3.1 | <0.0001 |

| Death | 1 | 0.1 | 39 | 1.3 | <0.0001 |

| COVID‐19 vaccination status8 261 955 | 0.003 | ||||

| Not vaccinated | 443 | 53.6 | 1166 | 59.6 | |

| Vaccinated | 383 | 46.4 | 789 | 40.4 | |

| One dose | 30 | 7.8 | 65 | 8.3 | |

| Two doses | 257 | 67.1 | 630 | 79.8 | |

| Three doses | 95 | 24.8 | 93 | 11.8 | |

| Four doses** | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Median time between last vaccine injection and positive SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR (min−max) (days)209 515 | 122 (1−299) | 137 (1−316) | 0.0001 | ||

| Time range between last vaccine injection and positive SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR (days)209 562 | |||||

| ≤21 | 55 | 26.3 | 64 | 11.4 | <0.0001 |

| >21 | 154 | 73.7 | 498 | 8.6 | |

Note: Superscript numbers indicate the number of patients for whom data were available.

ID‐NOW technique.

Patients with a previous SARS‐CoV‐2 infection were considered as having received one dose of vaccine.

χ 2, Fisher's exact test or t test when appropriate. STATA software version 16.0 (Copyright 2009 StataCorp LP, http://www.stata.com) was used for statistical analysis. Differences in the proportions were tested by Pearson's χ 2 or Fisher's exact tests when appropriate. Differences in the mean of quantitative variables were evaluated using t test. Results with a p value ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

As a comparison, patients infected with the Delta variant during the same period of time were significantly older with a greater proportion presenting with a high viral load (37.4%). They were significantly more likely to be symptomatic (77.6%) than patients infected with the Omicron variant and their hospitalization rate was 6.2 times higher (median age of 63 years), transfer to ICU was 31 times more frequent and lethality rate was 13 times higher (median age of 63 years).

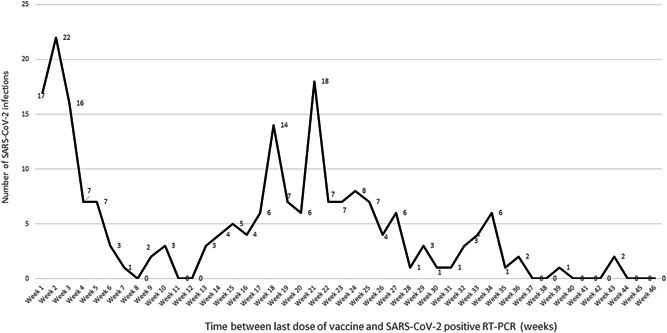

3.2. Vaccination status

Information about vaccination status was available for 826 Omicron cases (Table 1) of whom 46.4% were vaccinated, with the large majority having received at least two doses of vaccine (91.9%) including 7.8% who received one dose, 67.1% two doses, 24.8% three doses (one death), and 0.3% four doses. Interestingly, 26.3% of infections among vaccinated individuals occurred during the first 21 days following the last dose of vaccine (Figure 2). Compared to patients infected with the Omicron variant, those infected with the Delta variant were significantly less likely to be vaccinated (40.4%) and to be infected during the first 21 days following vaccination (11.4%). Viral load in vaccinated patients (mean C t value = 23.2) was similar to that of unvaccinated patients (mean C t value = 23.4) with p value = 0.3.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the numbers of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) Omicron infections corresponding to vaccine breakthrough according to time following the last dose of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination. The graphic represents the distribution of diagnoses of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection with the Omicron variant corresponding to vaccine breakthrough according to the number of weeks following anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination. The delay to infection was calculated as the difference between the time of the first positive SARS‐CoV‐2 qPCR and that of the vaccine dose (first to fourth dose) last received by the patient

4. DISCUSSION

We observed a rapid increase in the proportion of the SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant among SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected patients during December 2021, exceeding the Delta variant at the end of 2021 and supporting its higher transmissibility. 3 Unfortunately, we are unable to calculate the transmission dynamics due to the lack of necessary epidemiological data. It has been hypothesized that superspreading events may account for the increased transmissibility of the Omicron variant. 2 A short median time of incubation (3 days) was calculated in the context of a recent outbreak in Norway and may also account for the rapid spread of Omicron cases. 3 Of note, we observed a greater proportion of patients with a high viral load among those infected with the Delta variant as compared to those infected with the Omicron variant, suggesting that infectivity does not correlate with viral load.

We observed low rates of hospitalization, transfer to ICU, and death in patients infected with the Omicron variant, in line with other reports. 2 , 3 , 12 , 13 Compared to patients infected with the Delta variant during the same period of time, the severity of COVID‐19 in patients infected with the Omicron variant appeared much lower. However, larger cohorts of patients with a longer duration of follow‐up are required to conclude on the severity of the Omicron variant compared to that of other variants.

As already observed in other countries, a high proportion of cases occurred in fully vaccinated people (Table 2). In our experience, about one‐quarter of vaccinated patients who get infected with the Omicron variant were infected during the first 3 weeks following vaccination. These early infections may not be considered in other works. 2 , 12 The proportion of vaccinated cases and the proportion of early infections following vaccination was lower in patients infected with the Delta variant. These early breakthrough infections raise the question of a possible early and transient production of facilitating antibodies following vaccination with COVID‐19 mRNA vaccines, as previously suggested, 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 and they may be neglected and considered as direct side effects of the vaccine. As a matter of fact, infections in the 2 weeks following vaccination were not evaluated in most vaccine studies.

Table 2.

Vaccination rates in patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) Omicron variant in different early studies

| Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 1119 | 785 | 43 |

| Location | Marseille, France (this study) | Denmark 2 (nationwide) | US 12 (nationwide) |

| Study period | Nov 28−Dec 31, 2021 | Nov 28−Dec 9, 2021 | Dec 1−8, 2021 |

| Number of patients with known vaccination status | 826 | 785 | 42 |

| Number (%) of fully vaccinated patients | 353 (42.7%) | 655 (83.4%) | 34 (80.9%) |

In conclusion, the protection resulting from COVID‐19 vaccines against infection with Omicron is not optimal. The benefit of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines against severe infections may be limited if it is confirmed that the Omicron variant is not associated with severe forms of the disease. Finally, early breakthrough infections following COVID‐19 vaccination should be better studied by highlighting the possible presence of facilitating antibodies in the serum and the nasopharyngeal samples of the patients infected during the first 3 weeks following their vaccination.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

Didier Raoult has a conflict of interests being a consultant for Hitachi High‐Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan from 2018 to 2020. The remaining authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Didier Raoult designed the study. Linda Houhamdi, Philippe Gautret, Philippe Colson, and Didier Raoult wrote the paper. All authors contributed to materials/analysis, reviewed, and approved the manuscript.

Houhamdi L, Gautret P, Hoang VT, Fournier P‐E, Colson P, Raoult D. Characteristics of the first 1119 SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant cases, in Marseille, France, November−December 2021. J Med Virol. 2022;94:2290‐2295. 10.1002/jmv.27613

Linda Houhamdi and Philippe Gautret contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Santé publique France. COVID‐19: point épidémiologique du 30 décembre 2021. Accessed January 3, 2022. [https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-et-infections-respiratoires/infection-a-coronavirus/documents/bulletin-national/covid-19-point-epidemiologique-du-30-decembre-2021].

- 2. Espenhain L, Funk T, Overvad M, et al. Epidemiological characterisation of the first 785 SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant cases in Denmark, December 2021. Euro Surveill. 2021;26(50):2101146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brandal LT, MacDonald E, Veneti L, et al. Outbreak caused by the SARS‐CoV‐2 Omicron variant in Norway, November to December 2021. Euro Surveill. 2021;26(50):2101147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Colson P, Fournier P‐E, Chaudet H, et al. Analysis of SARS‐CoV‐2 variants from 24,181 patients exemplifies the role of globalisation and zoonosis in pandemics. Front Microbiol. 2022. medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.09.10.21262922v1 10.1101/2021.09.10.21262922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santé publique France. Variant Omicron: quelle surveillance mise en place? 2021. Accessed January 14, 2022. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/presse/2021/variant-Omicron-quelle-surveillance-mise-en-place

- 6. Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(18):3094‐3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078‐2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aksamentov I, Roemer C, Hodcroft EB, Neher RA. Nextclade: clade assignment, mutation calling and quality control for viral genomes. J. Open Source Softw. 2021;6(67):3773. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garrison E, Marth G. Haplotype‐based variant detection from short‐read sequencing. arXiv. org. 2012;1207:3907v2. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rambaut A, Holmes EC, O'toole Á, et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS‐CoV‐2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(11):1403‐1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elbe S, Buckland‐Merrett G. Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID's innovative contribution to global health. Glob Chall. 2017;1(1):33‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. CDC COVID‐19 Response Team . SARS‐CoV‐2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) variant−United States, December 1−8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1731‐1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abdullah F, Myers J, Basu D, et al. Decreased severity of disease during the first global Omicron variant COVID‐19 outbreak in a large hospital in Tshwane, South Africa. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;116:38‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arvin AM, Fink K, Schmid MA, et al. A perspective on potential antibody‐dependent enhancement of SARS‐CoV‐2. Nature. 2020;584(7821):353‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yahi N, Chahinian H, Fantini J. Infection‐enhancing anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies recognize both the original Wuhan/D614G strain and Delta variants. A potential risk for mass vaccination? J Infect. 2021;83(5):607‐635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee WS, Wheatley AK, Kent SJ, DeKosky BJ. Antibody‐dependent enhancement and SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines and therapies. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(10):1185‐1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fantini J, Yahi N, Colson P, Chahinian H, La Scola B, Raoult D. The puzzling mutational landscape of the SARS‐2‐variant Omicron. J Med Virol. 2022:1‐7. 10.1002/jmv.27577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.