Abstract

Waning antibodies and rapidly emerging variants are challenges for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) vaccine development. Adjusting existing immunization schedules and further boosting strategies are under consideration. Here, the immune responses induced by an alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in mice were compared among immunization schedules with two or three doses. For the two‐dose schedule, a 0–28‐day schedule induced 5‐fold stronger spike‐specific IgG responses than a 0–14‐day schedule, with only a slight elevation of spike‐specific cellular immunity 14 days after the last immunization. A third homologous boost 2 or 5 months after the second dose for the 0–28‐day schedule slightly strengthened humoral responses (1.3‐fold for the 0–1–3‐month schedule, and 1.8‐fold for the 0–1–6‐month schedule) 14 days after the last immunization. Additionally, a third homologous boost (especially with the 0–1–3‐month schedule) induced significantly stronger cell‐mediated immunity than both two‐dose immunization schedules for all indexes tested, with a response similar to that induced by a one‐dose heterologous boost with BNT162b2 in clinical trials, according to cellular immunity analysis (1.5‐fold). These T cell responses were Th2 oriented, with good CD4+ and CD8+ memory. These results may offer clues for applying a homologous boosting strategy for alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines.

Keywords: alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine, boost, cellular immunity, humoral response, immunization schedule, memory

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the first coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) case was reported in December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) has infected 355 million people and caused 5.61 million deaths globally in late January 2022. 1 , 2 , 3 Several vaccines, including messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, 4 , 5 adenovirus‐based vaccines, 6 , 7 and inactivated vaccines, 8 , 9 are being administered worldwide. Although two doses have been used for both mRNA (at 0 and 21 days or 0 and 28 days) and inactivated (at 0 and 14 days or 1 and 28 days) vaccines according to clinical trial results, only one dose was recommended for adenovirus‐based vaccines due to both efficacy and safety concerns.

Similar to observations for convalescent sera after natural SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, 10 , 11 neutralizing antibodies waned significantly within months after vaccination. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 Compared with mRNA vaccines that are dependent on intracellular production of spike protein antigens and the ability of mRNA itself to mobilize innate immune activity by inducing both higher neutralization titers and strong cellular immunity, 18 , 19 alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines induced lower neutralization titers and weaker cellular immunity after two‐dose immunization and exhibited a low protection rate in clinical phase III trials. 8 , 20 , 21 To improve vaccine efficacy, additional vaccination schedules with homologous or heterologous boost strategies for alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines are being considered. 22 , 23 , 24

For those who received the two‐dose full‐schedule immunization with alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines, mRNA vaccines and adenovirus‐based vaccines are considered heterologous boosts to increase not only humoral responses but also strengthen cellular immunity. 22 , 24 , 25 Correspondingly, reported homologous boosting with the third dose of alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine is mainly aimed at elevating neutralization titers without fully evaluating the enhancement of cellular immunity. 23 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 In addition, the effects of the final boost intervals should be carefully evaluated. In this report, we studied the humoral and cellular immunity induced by two and three doses of an alum adjuvant‐inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in mice, and both were administered according to the routine vaccination schedule. These results may offer helpful clues for optimizing the homologous boosting strategy for alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Vaccines

An inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine adjuvant with aluminum was supplied by the Institute of Medical Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (IMBCAMS). The vaccine contains the KMS‐1 SARS‐CoV‐2 strain (GenBank accession number MT226610.1) double inactivated with formaldehyde plus β‐propiolactone and adjuvanted with aluminum hydroxide; this is the same vaccine that was used in phase II clinical trial. 30

2.2. Mouse studies

For immunogenicity studies, specific pathogen‐free female Balb/C mice (6–8 weeks, 20–22 g) were used. Mice were supplied by the Central Animal Services of the IMBCAMS and maintained under standard pathogen‐free conditions before use. For each dose, mice were administered 1/10 of the human immunogen dose intramuscularly, that is, 15 enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay units (EU) of viral antigen and 25 μg of aluminum hydroxide. Whole blood samples were collected at different time points via the tail vein or cardiac puncture. After centrifugation at 1000 g for 30 min, sera were obtained and stored at −80°C before use. Mice were killed 2 weeks after the final immunization, and spleen cells were collected as described elsewhere. 31

2.3. Detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein‐specific antibodies

The levels of spike protein‐specific antibodies in serum samples collected from immunized mice were determined by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Recombinant S‐trimer 6P proteins (S protein) (Atagenix), which is produced by mammalian cells and encoding mutated Met1‐Gln1208 of SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein (F817‐P, A892‐P, A899‐P, A942‐P, K986‐P, V987‐P) were used to precoat 96‐well microplates at a final concentration of 2 μg/ml. After incubation overnight at 4°C, the plates were washed three times with PBST (phosphate‐buffered saline containing 0.05% (v/v) polysorbate 20). Five percent (w/v) skim milk in PBS was used to block the plates for 1 h, and serial dilutions of mouse sera were incubated for another 1 h. Goat anti‐mouse IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (1:10 000, 1:500, and 1:2000, respectively; Bio‐Rad) were used as detection antibodies. After adding the mixed substrate 3,3,5,5‐tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, BD) for 5 min, 1 M sulfuric acid was added to stop the reaction. The absorbance at 450 nm was detected with a spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc.). IgG/IgG1/IgG2a titers were defined as the endpoint dilutions showing cutoff signals above OD450 = 0.15, and antibody titers lower than 50 at a dilution of 1:500 were defined as 50 for calculations. 32

2.4. Cytokine analysis

Spleen cells were suspended in RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute, Thermo Fisher) 1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Biological Industries) and penicillin‐streptomycin (Thermo Fisher) at a final concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml. Then, 100 µl of cells was added to each well of a 96‐well plate (Corning Inc.). Recombinant S‐trimer 6P protein, at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, was added to each well, and the same volume of PMA + ionomycin (DAKEWE) was used as a positive control. After incubation for 24 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, the supernatant of cells was collected, and the contents of IL‐2, IFN‐γ, IL‐4, and IL‐13 were tested by ELISA. Briefly, unconjugated IL‐2 (3 μg/ml), IFN‐γ (4 μg/ml), IL‐4 (3 μg/ml), and IL‐13 (3 μg/ml) antibodies (Invitrogen) dissolved in PBS were used to coat 96‐well plates for 16 h at 4°C. After blocking with 5% (w/v) skim milk at 37°C for another 1 h, 50 μl/well cell supernatant was added to each well and incubated for 3 h at room temperature. Biotin‐conjugated antibodies against IL‐2, IFN‐γ, IL‐4, and IL‐13 (2 μg/ml, Invitrogen) and HRP‐conjugated streptavidin (1 μg/ml, Biolegend) were incubated with the samples for 1 h and 30 min. The reaction was terminated, and the results were detected as described above in the antibody detection section.

2.5. Enzyme‐linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay

According to the manufacturer's protocol, spleen cells (5 × 105 cells/well) from immunized mice were seeded in 96‐well plates for further analysis with an ELISPOT assay kit (BD). Recombinant S‐trimer 6P protein at 20 µg/ml was used to stimulate S protein‐specific T cell responses, and the same volume of PMA + ionomycin was used as a positive control. Spots were counted with an ELISPOT reader system (Autoimmun Diagnostika GmbH) after immunoimaging. 33

2.6. Flow cytometry

All of the following reagents were purchased from Biolegend. A total of 1 × 106 splenocytes were incubated with 10 µg/ml S proteins at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2 h, then 5 µg/ml brefeldin A was added. Splenocytes were incubated overnight under the same conditions to block cytokines release. After washing with staining buffer, 100 μl of Zombie NIR™ (Biolegend) was added to each vial for the incubation of 30 min. Then, 5 µg/ml anti‐CD16/CD32 antibodies were added, and the splenocytes were incubated at 4°C for 10 min to block nonspecific binding of Fc receptors. Then, PC5.5 anti‐mouse CD4, FITC anti‐mouse CD8, BV510 anti‐mouse CD44, and BV421 anti‐mouse CD62L antibodies were added for another 30 min at 4°C. After washing with permeabilization buffer, PE‐tagged anti‐mouse IFN‐γ and APC‐tagged anti‐mouse IL‐2 antibodies were added and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. After staining, the cells were gated (forward and side scatter, FSC/SSC), and samples with more than 20 000 events for CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were analyzed with a CytoFLEX flow cytometer (Beckman) and FlowJo_V10 software (BD).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 9.2 (GraphPad Software Inc.) and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Significant differences among experimental groups were analyzed by ordinary one‐way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test, comparing the mean of each group with the mean of the control group. Asterisks representing the p‐value classification: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

3. RESULTS

3.1. The immunization schedule with three doses induces higher IgG titers than that does with two doses

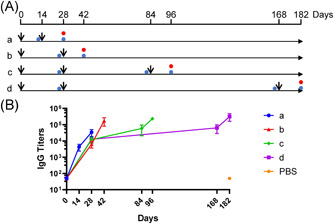

Four immunization schedules were designed, as follows: two doses for Group a, 0–2 weeks (0–14 days); two doses for Group b, 0–4 weeks (0–28 days); three doses for Group c, 0–1–3 months (0–28–84 days); and three doses for Group d, 0–1–6 months (0–28–168 days). Mice immunized with the same volume of PBS were included as the control group. Mice were killed 14 days after the final immunization in all groups (shown by red circles in Figure 1A). Antisera from the immunized mice were collected before each immunization and 2 weeks after the last immunization (shown by blue circles in Figure 1A) for antibody measurement.

Figure 1.

IgG antibodies elicited by different immunization schedules for inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) vaccines. (A) Immunization schedules for inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines. Black arrows indicate vaccine injections for each group of mice. The time points at which mouse blood was collected and killed mice are shown as blue and red circles. (B) S‐specific IgG titers of immune serum from immunized mice. N = 6. Data are shown as the mean with standard deviation. PBS, phosphate‐buffered saline

Regarding the interval between the first and the second immunization, 4 weeks was better than 2 weeks, with Groups b, c, and d on Day 28 showing nearly triple the IgG titers than in Group a on Day 14 (Figure 1B). Regarding the interval between the second and third immunization, the 2‐month interval in Group c (from 12 000 to 58 667, for a titer increase of 4.89‐fold) did not appear to be significantly different from the 5‐month interval in Group d (from 12 667 to 64 000, for a 5.05‐fold increase in the mean value).

Regarding the final IgG titers 2 weeks after the last immunization, the two‐dose immunization schedule, 0–4 weeks (Group b), had a clear advantage over 0–2 weeks (Group a), as the IgG titers had grown fivefold at the endpoint (34 667 in the Group a vs. 176 000 in Group b). Overall, the IgG titers of the three‐dose immunization schedule (234 667 in Group c, 320 000 in Group d, mean value) were higher than those of the two‐dose immunization schedule (34 667 in Group a, 176 000 in Group b, mean value) at the endpoint.

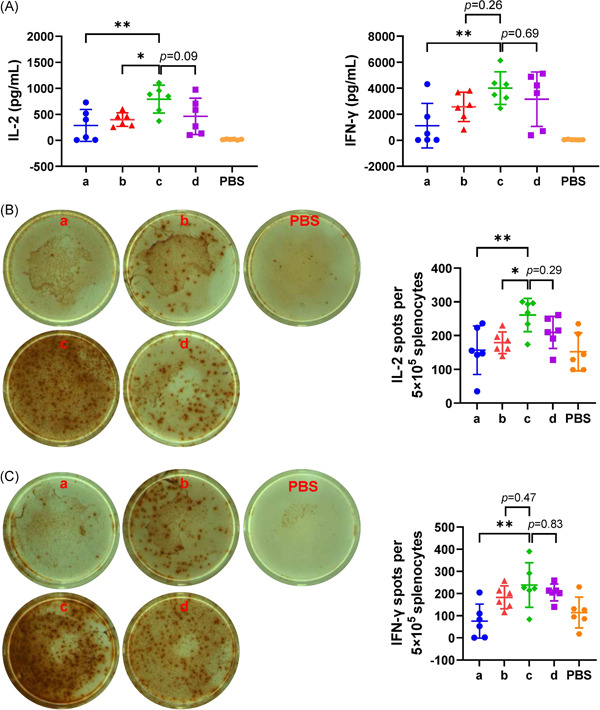

3.2. A three‐dose immunization schedule of 0–1–3 months induced the most potent cell‐mediated immunity

The three‐dose immunization schedule of 0–1–3 months (Group c in Figure 2) induced the most potent cell‐mediated immunity, followed by the schedule of 0–1–6 months (Group d in Figure 2). Although the difference between Group c and Group d was not significant, Group c exhibited significantly stronger cell‐mediated immunity than the two‐dose immunization schedule (Group a or Group b) for all tested indexes.

Figure 2.

Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and enzyme‐linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay performed with isolated splenocytes from immunized mice. (A) IL‐2 and IFN‐γ secreted by splenocytes upon stimulation with the S protein were detected by ELISA. (B) IL‐2‐producing splenocytes after S protein stimulation. (C) IFN‐γ‐producing splenocytes after S protein stimulation. Representative images of spots around the mean value for the groups are also shown in the left panels of (B) and (C). N = 6, points represent individual mice. Data were compared using one‐way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons tests, with Group c as the control. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. PBS, phosphate‐buffered saline

Regarding ELISA analysis (Figure 2A), the IL‐2 level was 790.3 pg/ml in the supernatant of Group c splenocytes after SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein stimulation, which was significantly higher than that in the supernatants of the groups subjected to the two‐dose immunization schedule (p = 0.006 for Group a, p = 0.04 for Group b). Although the IFN‐γ level was 4008 pg/ml in the supernatant of Group c splenocytes after SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein stimulation and higher than that in the supernatants of the groups subjected to the two‐dose immunization schedule, the difference was only significant compared with the Group a (p = 0.006).

Regarding ELISPOT analysis, the number of IL‐2 secreting cells (Figure 2B) in Group c was 260.8 per 5 × 105 splenocytes after SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein stimulation, which was significantly higher than that in the groups subjected to the two‐dose immunization schedule (p = 0.008 for Group a, p = 0.04 for Group b). Although the number of IFN‐γ secreting cells (Figure 2C) after SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein stimulation was 238.5 per 5 × 105 splenocytes in Group c and higher than that in the groups subjected to the two‐dose immunization schedule, the difference was only significant compared with the Group a (p = 0.002), as observed for ELISA.

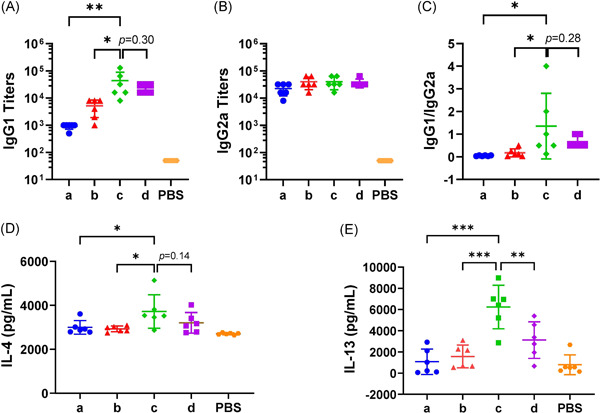

3.3. The three‐dose immunization schedule yielded more potent Th‐2‐oriented responses

The three‐dose immunization schedule of 0–1–3 months induced titers of S‐specific IgG2a antibodies (Group c in Figure 3B) equal to those induced by the two‐dose immunization schedule in Group b (IgG2a titers = 40 000), followed by the IgG2a titers induced in Group d (IgG2a titers = 37 333) and Group a (IgG2a = 22 667). Although no significant difference was detected between the IgG2a titer in Group c and those in the other three groups, S‐specific IgG1 antibodies were disproportionately elevated for the groups subjected to the three‐dose immunization schedule (Figure 3A). The S‐specific IgG1 antibody titers induced in Group c were significantly higher than those induced in the groups subjected to the two‐dose immunization schedule (p = 0.005 for Group a, p = 0.01 for Group b). Correspondingly, Group c showed the highest IgG1‐to‐IgG2a titer ratio, calculated to evaluate the Th1/Th2 balance (Figure 3C); this value was significantly higher than that in the groups subjected to the two‐dose immunization schedule (p = 0.02 for Group a, p = 0.03 for Group b).

Figure 3.

IgG subtypes and Th2 oriented cytokines elicited by different immunization schedules for inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccines. (A) S‐specific IgG1. (B) S‐specific IgG2a. (C) IgG1/IgG2a ratio. (D) and (E) IL‐4 and IL‐13 secreted by splenocytes upon stimulation with the S protein. N = 6, points represent individual mice. Data were compared using one‐way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons tests, with Group c as the control. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. PBS, phosphate‐buffered saline

Regarding Th2 oriented cytokines from ELISA analysis, the IL‐4 level (Figure 3D) was 3723 pg/ml in the supernatant of Group c splenocytes after SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein stimulation, which was significantly higher than that in the supernatants of the groups subjected to the two‐dose immunization schedule (p = 0.02 for Group a, p = 0.01 for Group b). The IL‐13 level (Figure 3E) was 6 245 pg/ml in the supernatant of Group c splenocytes after SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein stimulation, which was significantly higher than that in the supernatants of the other three groups (p < 0.001 for Group a and Group b, p = 0.004 for Group d).

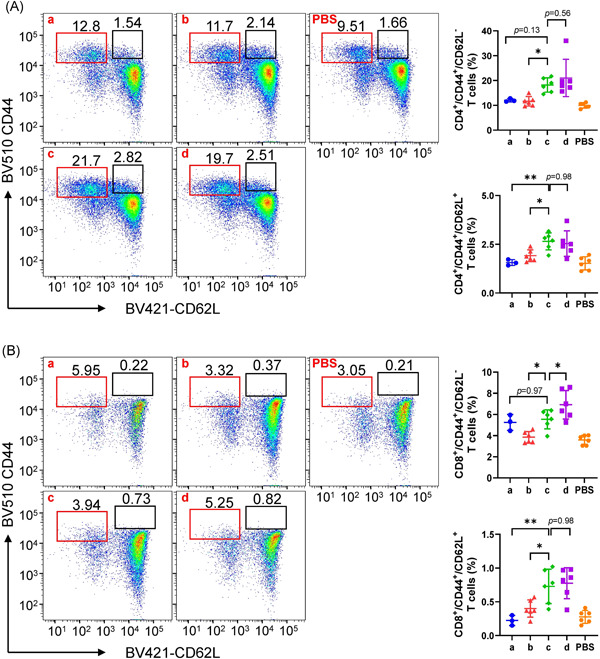

3.4. The three‐dose immunization schedule induced higher proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells in mice

As T cells become activated or progress to the memory stage, CD44 expression increases from low or moderate levels to high levels. Thus, CD44 has been reported to be a valuable marker for memory cell subsets. The expression of CD62L has also been used to distinguish naïve, effector, and memory T cells. 34 , 35 , 36 Once reactivated by antigens, memory CD4+ cells could assist with the production of antibodies by B cells, and memory CD8+ cells could help increase the production of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. In brief, CD44+/CD62L+ cells were used to gate memory T cells.

The three‐dose immunization schedule of 0–1–3 months induced CD4+ (Figure 4A) and CD8+ (Figure 4B) memory T cell numbers comparable to those induced by the three‐dose immunization schedule of 0–1–6 months. CD4+ memory T cell numbers (Figure 4A) in Group c were significantly higher than those in the two‐dose immunization schedule groups on effector memory cells (p = 0.03 for Group b) and central memory cells (p = 0.007 for Group a, p = 0.03 for Group b). Similar tendencies were also observed when CD8+ memory T cells (Figure 4B) were compared between Group c and the two‐dose immunization schedule groups on effector memory cells (p = 0.01 for Group b) and central memory cells (p = 0.003 for Group a, p = 0.02 for Group b).

Figure 4.

CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cell analysis by flow cytometry. (A) CD4+ memory T cells. (B) CD8+ memory T cells. Pseudocolor images displaying representative results near the average value for gated CD44+/CD62L+ cells are listed in the left panels of (A) and (B). N = 6, points represent individual mice and three data points for which the cells clotted in the Group a were eliminated. Data are shown as the mean with standard deviation and were compared using one‐way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons tests, with Group c as the control. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. PBS, phosphate‐buffered saline

4. DISCUSSION

Waning antibodies and rapidly emerging variants are two great challenges for developing SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines in all forms. Two‐dose immunization with alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines induced relatively lower neutralization titers and weaker cellular immunity than other forms of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines, for example, mRNA/adenovirus vaccines, which indicates the urgent need for an immune boost.

A heterologous boost for two‐dose immunized alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines was reported to elevate humoral responses and strengthen cellular immunity. Adenovirus‐based vaccines alone induced both high SARS‐CoV‐2 neutralization antibodies and SARS‐CoV‐2 spike‐specific T cell responses. When used as a one‐dose heterologous boost vaccine for two‐dose immunized alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines in mice, adenovirus‐based vaccines elevated the humoral responses 100‐fold and strengthened cellular immunity by 30‐fold. 24 As the most widely administered mRNA vaccine worldwide, BNT162b2, dependent on intracellular production of spike protein antigens and the innate immunity mobilization activity of mRNA itself, induced both high titers of SARS‐CoV‐2 neutralization antibodies and strong SARS‐CoV‐2 spike‐specific T cell responses. 19 When used as a one‐dose heterologous boost vaccine for two‐dose immunized alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines in clinical trials, BNT162b2 elevated the humoral responses by 70‐fold, but cellular immunity was strengthened by 1.5‐fold. 25

In this study, in mice, the two‐dose immunization schedule of 0–28 days for alum‐adjuvanted SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines induced 5‐fold stronger spike‐specific IgG responses than the 0–14 day schedule 14 days after the final immunization (Figure 1), which is consistent with a clinical trial for the comparison of a two‐dose immunization schedule for alum‐adjuvanted SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines. 29 Homologous boosting 2 months after the last immunization in the 0–28‐day group (i.e., 0–28–84 days) strengthened the humoral response by 1.3‐fold, and homologous boosting 5 months after the last immunization in the 0–28‐day group (i.e., 0–28–168 days) strengthened the humoral response by 1.8‐fold. These results were consistent with a clinical report that the third dose of alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines slightly elevated (<1.5‐fold) the geometric mean antibody titers. 26 Considering the rapidly waning nature of SARS‐CoV‐2 humoral responses, the intensified antibody responses elicited by a third immunization, which were stronger than those induced by the two‐dose immunization schedule, suggest that good immune memory is induced after alum‐adjuvanted SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination. 23 , 27

Although antibody responses recalled by the third dose of alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines can neutralize emerging SARS‐CoV‐2 variants, including the alpha, beta, and delta variants, cellular immunity may also play important roles, considering the linear characteristics of viral epitopes. 28 Although the third immunization induced significantly stronger cell‐mediated immunity than both two‐dose immunization schedules for all of the indexes tested, the response was strengthened by less than 2‐fold (Figure 2), which is similar to the effect of a one‐dose heterologous boost with BNT162b2 in clinical trials for cellular immunity analysis (1.5‐fold). 25 On the other hand, the cellular immunity induced by the third dose of alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine showed the typical Th2 orientation (Figure 3), different from the Th1 orientation induced by the initial mRNA vaccine immunization. 19 , 31 , 37 Flow cytometry analysis showed higher proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells in the three‐dose immunization group (Figure 4), indicating easier recall of both humoral and cellular immunity when responding to virus infection.

In conclusion, for the two‐dose immunization schedule for alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines, the immunization schedule of 0–28 days was slightly superior to that of 0–14 days. A third homologous boost 2 months or 5 months after the second immunization slightly strengthened the humoral responses, but the 0–1–3‐month immunization schedule significantly strengthened spike‐specific cellular immunity, with a Th2 orientation and good T cell memory.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Animal Care and Welfare of IMB, CAMS, and the Yunnan Provincial Experimental Animal Management Association (permit number: SYXK [dian] K2019‐0003).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ning Luan and Yunfei Wang performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Han Cao and Kangyang Lin performed part of the experiments. Cunbao Liu designed the study and drafted and finalized the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant numbers 2020YFC0849700 and 2020YFC0860600), the Major Science and Technology Special Projects of Yunnan Province (grant numbers 202003AC100009 and 202002AA100009), the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (grant number 2021‐I2M‐1‐043), the China Health and Longevity Innovation Competition (2021‐JKCS‐012), the Special Biomedicine Projects of Yunnan Province (202102AA310035), the Basic Research Projects of Yunnan Province (202101AT070286), the Funds for the Training of High‐Level Health Technical Personnel in Yunnan Province (grant number H‐2019063) and the Funds for High‐level Scientific and Technological Talents Selection Special Project of Yunnan Province.

Luan N, Wang Y, Cao H, Lin K, Liu C. Comparison of immune responses induced by two or three doses of an alum‐adjuvanted inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in mice. J Med Virol. 2022;94:2250‐2258. 10.1002/jmv.27637

Ning Luan and Yunfei Wang contributed equally to this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565‐574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu F, Zhao S, Yu B, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579(7798):265‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA‐1273 SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403‐416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid‐19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603‐2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Halperin SA, Ye L, MacKinnon‐Cameron D, et al. Final efficacy analysis, interim safety analysis, and immunogenicity of a single dose of recombinant novel coronavirus vaccine (adenovirus type 5 vector) in adults 18 years and older: an international, multicentre, randomised, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;399:237‐248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, et al. Safety and efficacy of single‐dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine against covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(23):2187‐2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jara A, Undurraga EA, González C, et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in Chile. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:875‐884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tanriover MD, Doğanay HL, Akova M, et al. Efficacy and safety of an inactivated whole‐virion SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine (CoronaVac): interim results of a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled, phase 3 trial in Turkey. Lancet. 2021;398(10296):213‐222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choe PG, Kang CK, Suh HJ, et al. Waning antibody responses in asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:1‐329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seow J, Graham C, Merrick B, et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in humans. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5(12):1598‐1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bayart JL, Douxfils J, Gillot C, et al. Waning of IgG, total and neutralizing antibodies 6 months post‐vaccination with BNT162b2 in healthcare workers. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(10):1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Campo F, Venuti A, Pimpinelli F, et al. Antibody persistence 6 months post‐vaccination with BNT162b2 among health care workers. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(10):1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cucunawangsih C, Wijaya RS, Lugito NPH, Suriapranata I. Antibody response to the inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine among healthcare workers, Indonesia. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;113:15‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Favresse J, Bayart JL, Mullier F, et al. Antibody titres decline 3‐month post‐vaccination with BNT162b2. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10(1):1495‐1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Khoury J, Najjar‐Debbiny R, Hanna A, et al. COVID‐19 vaccine—long term immune decline and breakthrough infections. Vaccine. 2021;39(48):6984‐6989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thomas SJ, Moreira ED, Jr. , Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid‐19 vaccine through 6 months. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1761‐1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Corbett KS, Flynn B, Foulds KE, et al. Evaluation of the mRNA‐1273 vaccine against SARS‐CoV‐2 in nonhuman primates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1544‐1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laczkó D, Hogan MJ, Toulmin SA, et al. A single immunization with nucleoside‐modified mRNA vaccines elicits strong cellular and humoral immune responses against SARS‐CoV‐2 in mice. Immunity. 2020;53(4):724‐732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pan HX, Liu JK, Huang BY, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 inactivated vaccine in healthy adults: randomized, double‐blind, and placebo‐controlled phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134(11):1289‐1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Melo‐González F, Soto JA, González LA, et al. Recognition of variants of concern by antibodies and T cells induced by a SARS‐CoV‐2 inactivated vaccine. Front Immunol. 2021;12:747830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. He Q, Mao Q, An C, et al. Heterologous prime‐boost: breaking the protective immune response bottleneck of COVID‐19 vaccine candidates. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10(1):629‐637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liao Y, Zhang Y, Zhao H, et al. Intensified antibody response elicited by boost suggests immune memory in individuals administered two doses of SARS‐CoV‐2 inactivated vaccine. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10(1):1112‐1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang J, He Q, An C, et al. Boosting with heterologous vaccines effectively improves protective immune responses of the inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10(1):1598‐1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Intapiboon P, Seepathomnarong P, Ongarj J, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an intradermal BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine booster after two doses of inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in healthy population. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(12):1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu J, Huang B, Li G, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a three‐dose regimen of a SARS‐CoV‐2 inactivated vaccine in adults: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase 2 trial. J Infect Dis. 2021. 10.1093/infdis/jiab627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yue L, Xie T, Yang T, et al. A third booster dose may be necessary to mitigate neutralizing antibody fading after inoculation with two doses of an inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine. J Med Virol. 2022;94(1):35‐38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yue L, Zhou J, Zhou Y, et al. Antibody response elicited by a third boost dose of inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine can neutralize SARS‐CoV‐2 variants of concern. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10(1):2125‐2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zeng G, Wu Q, Pan H, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of a third dose of CoronaVac, and immune persistence of a two‐dose schedule, in healthy adults: interim results from two single‐centre, double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled phase 2 clinical trials. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021. 10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00681-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Che Y, Liu X, Pu Y, et al. Randomized, double‐blinded and placebo‐controlled phase II trial of an inactivated SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine in healthy adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;73(11):e3949‐e3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cao H, Yang S, Wang Y, et al. An established Th2‐oriented response to an alum‐adjuvanted SARS‐CoV‐2 subunit vaccine is not reversible by sequential immunization with nucleic acid‐adjuvanted Th1‐oriented subunit vaccines. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(11):1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cao H, Wang Y, Luan N, Liu C. Immunogenicity of varicella‐zoster virus glycoprotein E formulated with lipid nanoparticles and nucleic immunostimulators in mice. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(4):310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Y, Qi J, Cao H, Liu C. Immune responses to varicella‐zoster virus glycoprotein E formulated with poly(lactic‐co‐glycolic acid) nanoparticles and nucleic acid adjuvants in mice. Virol Sin. 2021;36(1):122‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cao H, Wang Y, Luan N, Lin K, Liu C. Effects of varicella‐zoster virus glycoprotein E carboxyl‐terminal mutation on mRNA vaccine efficacy. Vaccines (Basel). 2021. 129(12):1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roberts AD, Ely KH, Woodland DL. Differential contributions of central and effector memory T cells to recall responses. J Exp Med. 2005;202(1):123‐133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sckisel GD, Mirsoian A, Minnar CM, et al. Differential phenotypes of memory CD4 and CD8 T cells in the spleen and peripheral tissues following immunostimulatory therapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Corbett KS, Edwards DK, Leist SR, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature. 2020;586(7830):567‐571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.