Abstract

In 2019, young Australians reported that two of their top concerns were ‘climate change and the environment’ and ‘mental health’. The events of 2020/2021, such as the ongoing climate emergency, the Australian bushfires, and the COVID‐19 pandemic, reflect the human‐induced environmental issues young people are most worried about and have also exacerbated the mental health issues which they already reported to be at a crisis point back in 2019. Given experiences of mental illness in adolescence are associated with poorer mental health across the lifespan, it is becoming increasingly important to address ecological determinants of youth mental health in the Anthropocene. However, despite the inclusion of ecological determinants of health in seminal health promotion frameworks, health promotion has been described as ‘ecologically blind’, emphasising social determinants of health at the expense of ecological determinants of health. A socio‐ecological model, which equally considers upstream social and ecological factors, should be applied to youth mental health issues. Using the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, we demonstrate how the ecological determinants of health may be incorporated into health promotion approaches targeting youth mental health. We also call for the health promotion sector to consider a number of actions to work towards achieving a transition to ecological determinants of health being at the forefront of health promotion activities. This commentary, written by young public health professionals, hopes to build on the momentum garnered by youth activists around the world and bring attention to the importance of ecological determinants of health for youth mental health promotion in the era of COVID‐19 and the Anthropocene.

Keywords: ecological determinants of health, health promotion, healthy environments, mental health, Ottawa Charter, social determinants, youth

1. INTRODUCTION

During a 2019 “Listening Tour”, young Australians identified climate change, the environment, and youth mental health as their top concerns. 1 Proceeding events in 2020/2021, including the ongoing climate emergency, bushfires, and COVID‐19 pandemic reflect the environmental issues young people were worried about, and they have also exacerbated mental health issues. Given natural climate systems have irrevocable tipping points, and experiences of mental illness in adolescence tend to persist across the lifespan, it is becoming increasingly important to address ecological determinants of youth mental health in the Anthropocene.

2. ECOLOGICAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

Theories and practices of health promotion are continually evolving, reflecting the nature of health and knowledge. Influenced by work such as the 1974 Lalonde Report, the World Health Organization ‘Health for All’ in the 1970s, and the establishment of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion in 1986, health promotion has historically emphasised the importance of the social determinants of health (SDoH). 2 However, the Ottawa Charter, which provides the foundations for health promotion, also emphasises the inextricable links between human health and the natural environment. 2 The framework states that the ‘protection of natural and built environments and the conservation of natural resources should be integral to any health promotion strategy’, with ‘stable ecosystems’ and ‘sustainable resources’ included as prerequisites for health (p. 3). 2 Therefore, ecological determinants of health (EDoH) should also be included in health promotion practice.

EDoH are ecosystem‐based ‘goods and services’ that are provided by nature. Among the most important of these are oxygen, water, food, and a reasonably stable and habitable climate. 3 Despite the inclusion of EDoH in seminal frameworks, health promotion has been described as ‘ecologically blind’, meaning the SDoH are often emphasised at the expense of EDoH. 4 , 5 Social and ecological determinants of health interact with each other and ultimately influence the health of populations. 5 As such, a socio‐ecological approach that considers both upstream social and ecological factors is required in health promotion.

It is becoming increasingly important to address EDoH alongside SDoH in contemporary society, where populations are becoming more vulnerable to climate and natural systems changes. The term ‘Anthropocene’ refers to an era that recognises the negative impact humans have on Earth's systems, posing significant threats to human health. 3 For example, the events of 2020/2021, such as the ongoing climate emergency, the Australian bushfires, and the COVID‐19 pandemic, have had significant impacts on human health. Importantly, these events have human‐induced ecological issues at their core. Increasing global temperatures (climate change) are the result of greenhouse gas pollution arising from human activities since the Industrial Revolution. These elevated temperatures create environments that facilitate greater frequency and extremity of natural disasters (bushfires). Land clearing for urban and agricultural purposes may create unstable ecosystems and environmental pressures which displace wildlife and ultimately increase potential human exposure to novel zoonotic viruses (increasing pandemic risk).

3. YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH

Globally, young people are awakening to, and experiencing the health threats of, the Anthropocene. Youth‐led climate strikes and advocacy have become commonplace and in March 2019 it is estimated that 1.6 million youth activists, across 125 countries, demanded action be taken against climate change. 6 In the same year, young Australians reported that one of their top areas of concern was ‘climate change and the environment’. 1

Alongside this, young Australians also reported ‘mental health’ to be one of their top concerns. 1 Young Australians’ concerns about mental health, climate change, and the environment are not mutually exclusive. The psychological burden of climate change and natural disasters has led to the emergence of new psychological phenomena which are specifically related to feelings of distress around the state of the environment: namely, ‘eco‐anxiety’ and ‘climate grief’. 6 , 7 The ongoing climate emergency, 2020 bushfires, and COVID‐19 pandemic reflect the issues young Australians are most worried about and have exacerbated the mental health issues which they already reported to be “at a crisis point” in 2019. 1 In 2020, Kids Helpline reported a 15% increase in calls during the bushfires and a 40% spike during COVID‐19 restrictions. 8

4. INCORPORATING EDOH IN YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH PROMOTION: A CALL TO ACTION

This commentary, written by young public health professionals, hopes to build on the momentum garnered by youth activists globally and bring attention to the importance of EDoH for youth mental health. While responses to health issues have historically been reactive (eg, funding mental health services) rather than preventive, we can no longer afford to be reactive with ecologically‐driven mental health issues. Natural climate systems are reaching tipping points, while experiences of mental illness in adolescence are linked to poorer mental health across the lifespan, 9 making preventive action prudent. To address the challenges of the Anthropocene, EDoH must transition to the forefront of health promotion, as called for at the 2019 World Conference on Health Promotion in Rotorua.

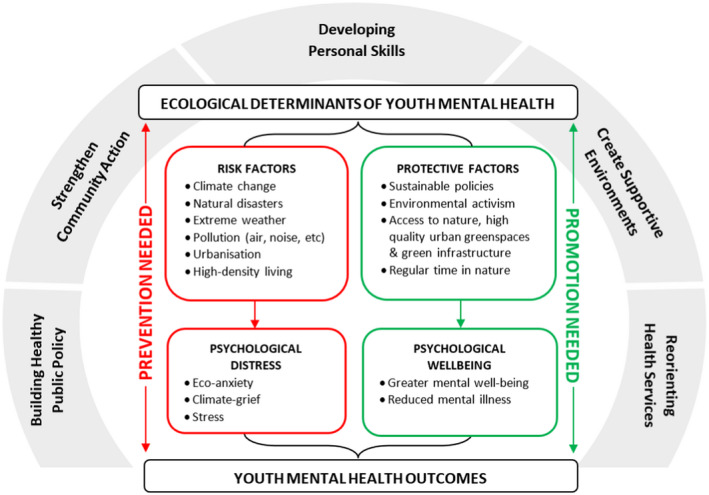

Although not an exhaustive representation, Figure 1 demonstrates how EDoH may present both risk and protective factors for youth mental health, highlighting where prevention is needed and promotion is required through the Ottawa Charter action areas. Building on Figure 1, we briefly demonstrate how EDoH may be incorporated into health promotion approaches targeting youth mental health, from an individual level through to the roles of institutions, policy, and culture. We call for all professionals in the health promotion sector to consider the following actions.

FIGURE 1.

Ecological determinants of youth mental health: A need for prevention and promotion through the Ottawa Charter action areas

5. RECOGNISING NATURE AS A HEALTH PROMOTION RESOURCE

Solutions to ecological and youth mental health issues can be symbiotic, with nature offering a range of opportunities for health‐promoting interventions, which may also encourage environmental protection. Health promotion practitioners should consider EDoH when applying health promotion principles to their work in youth mental health, through frameworks like the Ottawa Charter. For example, supporting young people to develop health literacy around the mental health benefits of connecting with nature is one approach. Despite young peoples’ concerns for the environment, their engagement with nature is relatively low; in some cases, children report higher daily screen time than weekly time spent in nature. 9 In a survey of Australian adults, 73% reported playing outdoors more often than indoors when they were children, but only 13% could say that this was true for their own children today. 10 Contact with nature supports mental health as humans are psychologically and physiologically regulated to function optimally in the natural environmental conditions under which we evolved. 11 Increased social connections and physical activity experienced in greenspaces also support young people's mental health. 12 Developing health literacy around the mental health benefits of connecting with nature is especially important in the context of COVID‐19, with research highlighting how nature engagement has protected young peoples’ mental health during lockdowns. 13

Health services may also be reoriented to capitalise on the mental health benefits afforded by nature. For example, ‘social prescribing’, which enables health professionals to refer individuals to non‐clinical services to support their health, may be used for youth mental health approaches. 14 Examples of social prescribing related to EDoH are known as ‘green prescriptions’ and include guided nature walks, farm visits, forest bathing, and community gardening. 15 To date, the adoption of social prescribing has been limited in the Australian healthcare system. In view of current strains on mental health services and the known psychological benefits of contact with nature, green prescriptions may support youth mental health in the era of COVID‐19 and the Anthropocene.

6. FOSTERING INTERSECTORAL COLLABORATION

The transition towards EDoH being at the forefront of health promotion practice cannot be achieved without intersectoral collaboration. Effective policy making in the climate‐health space is often hindered by the siloed nature of government departments, research institutes, and short‐term funding, 4 which can perpetuate a lack of knowledge and understanding about climate‐health issues young people experience. Utilising a systems‐thinking approach 16 when addressing wicked problems, such as climate change and youth mental health, can encourage intersectoral collaboration beyond just the health sector.

Health in All Policies (HiAP) is a collaborative approach that aims to consider the health implications of policies and decisions made across all sectors 17 and is based on the recognition that most public health challenges exist, and can be improved, outside of the health sector. While HiAP specifically addresses the SDoH, 17 it has not historically included a significant focus on EDoH. Ecologically‐driven disasters are likely to become more frequent in the coming years, as will the mental health impacts experienced by young people. As such, intersectoral collaboration and consideration of the EDoH which impact youth mental health is essential for planning projects and building healthy public policy across government and industry sectors.

As an example, an intersectoral approach may be applied through urban planning. By 2061, 75% of Australians are expected to be living in major cities, removed from nature. 18 To accommodate for increasing urbanisation, high‐density living will mean fewer families will have access to private yards. 19 Built environments have higher noise and air pollution, and ambient temperature—contributing to both poorer psychological and environmental outcomes. 12 Increasing access to nature through urban greenspaces and green infrastructure is one intersectoral approach to creating cities that are environmentally healthy, increase biodiversity, and also support youth mental health. This is particularly important in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic, with young Australians living in greener neighbourhoods reporting better mental health during lockdowns. 13 Given urban greenspace is inequitably distributed across Australia, 20 increasing access is particularly important for young people living in low socioeconomic areas, reiterating the social equity issues related to EDoH.

7. ENGAGING YOUNG PEOPLE IN GENERATING SOLUTIONS

Eco‐anxiety and climate grief are considered reasonable and functional responses to climate‐related losses, which can be adaptive when channelled into productive and positive change. 7 Research with young activists highlights that participation in climate movements can generate hope and empowerment for young people. 21 As such, strengthening and supporting young peoples’ activism in the community may be an important approach to supporting their mental health, while also maintaining pressure for action to mitigate climate change.

In addition to intersectoral collaboration, young people should have the opportunity to engage in generating solutions to ecologically‐driven mental health problems. Using co‐design methods to meaningfully involve young people throughout the design and delivery of mental health promotion initiatives should be considered. Co‐design is a problem‐solving tool that brings together those with expertise and/or lived experience, on equal ground, to design solutions. 22 The advocacy efforts of young people should not be seen as just a symbol of hope; instead, young people should be respected as valuable contributors in generating long‐term sustainable climate solutions which support youth mental health.

8. RECONCILING PARADIGMS OF CULTURE AND INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE

Anthropocentric perspectives of western ideologies, which view humanity at the centre of all things, can ultimately hinder health promotion's ability to focus on EDoH and enact the actions outlined above. 4 For the Australian health promotion community to successfully address EDoH of youth mental health, cultural determinants of health, especially Indigenous knowledge systems, must be considered. In contrast to the westernised attitudes of dominance and superiority towards nature, Indigenous cultures entail a deep spiritual connection to Country which is central to their social and emotional wellbeing. 23 Indigenous cultures foster the health of ecosystems to ensure ecological sustainability and healthy communities. 23 , 24

Despite being highly valuable for developing effective and adaptive responses to climate‐health issues, Indigenous values and knowledges are often overlooked in mainstream discussion and decision‐making in Australia. 24 , 25 A shift is required to embed Indigenous knowledges into mental health promotion to ensure approaches aimed at addressing EDoH are not solely underpinned by a western paradigm. 4 , 25 It is at this intersection of paradigms of culture and knowledge, where an equilibrium of human and environmental health, equity and social justice, may be achieved.

9. CONCLUSION

Youth mental health promotion in Australia can be improved through a transition towards EDoH being at the forefront, in conjunction with the SDoH. The events of 2020, as well as activism displayed by young people globally, should serve as a catalyst in achieving this transition. We must not continue to hide behind the term ‘unprecedented’ and operate with short‐sightedness and quick‐fixes. Building adaptation and climate resilience is key to seize new opportunities and progress to a new, more sustainable, equitable and healthy future. We must engage with complex planetary health issues and plan for a long‐term future, alongside young people, in which health will be driven by ecological solutions. Young peoples’ futures are depending on it.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

Ethics approval was not required for this commentary.

PATIENT CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION STATEMENT

Not applicable for this commentary.

ACKNOWLEGEMENT

We would like to thank Dr Rebecca Patrick for her encouragement and guidance throughout the writing of this commentary.

Oswald TK, Langmaid GR. Considering ecological determinants of youth mental health in the era of COVID‐19 and the Anthropocene: A call to action from young public health professionals. Health Promot J Austral. 2022;33:324–328. doi: 10.1002/hpja.560

Funding information

The authors have no funding to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. United Nations Youth Australia . Australian Youth Representative Consultation Report. Australia: UN Youth Australia; 2019. [cited 08 November 2021]. Available from: https://unyouth.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2020/01/2019‐YOUTH‐REPRESENTATIVE‐REPORT.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO) . The 1st International Conference on Health Promotion, Ottawa, 1986 . Genova: WHO; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hancock T, Spady DW, Soskolne CL. Global change and public health: addressing the ecological determinants of health. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Public Health Association; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Langmaid G, Patrick R, Kingsley J, Lawson J. Applying the mandala of health in the anthropocene. Health Promot J Austr. 2021;32(S2):8–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patrick R, Armstrong F, Hancock T, Capon A, Smith JA. Climate change and health promotion in Australia: Navigating political, policy, advocacy and research challenges. Health Promot J Austr. 2019;30(3):295–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu J, Snell G, Samji H. Climate anxiety in young people: a call to action. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(10):e435–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adaptive anxiety. Lancet Planet Health. 2020;4(4):e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Young E. Coronavirus worries have Australian children calling Kids Helpline every 60 seconds. Australia: SBS News; 2020. [updated 22 April 2020; cited 08 November 2021]. Available from: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/coronavirus‐worries‐have‐australian‐children‐calling‐kids‐helpline‐every‐69‐seconds [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oswald TK, Rumbold AR, Kedzior SG, Moore VM. Psychological impacts of “screen time” and “green time” for children and adolescents: a systematic scoping review. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0237725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Planet Ark Australia . Climbing Trees: Getting Aussie Kids Back Outdoors. Australia: Planet Ark; 2011. [cited 08 November 2021]. Available from: https://treeday.planetark.org/documents/doc‐534‐climbing‐trees‐research‐report‐2011‐07‐13‐final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol. 1995;15(3):169–82. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hartig T, Mitchell R, De Vries S, Frumkin H. Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:207–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oswald TK, Rumbold AR, Kedzior SGE, Kohler M, Moore VM. Mental Health of Young Australians during the COVID‐19 pandemic: exploring the roles of employment precarity, screen time, and contact with nature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and Consumers Health Forum of Australia (CHF) . Social Prescribing Roundtable, November 2019 Report. Canberra: CHF; 2020. [cited 08 November 2021]. Available from: https://chf.org.au/sites/default/files/social_prescribing_roundable_report_chf_racgp_v11.pdf] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chatterjee HJ, Camic PM, Lockyer B, Thomson LJ. Non‐clinical community interventions: a systematised review of social prescribing schemes. Arts & Health. 2018;10(2):97–123. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patrick R, Kingsley J. Exploring Australian health promotion and environmental sustainability initiatives. Health Promot J Austr. 2015;27(1):36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization . The Helsinki statement on health in all policies. Proceedings of the 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion; 2013 June 10–14; Helsinki, Finland: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Australian Demographic Statistics (ABS) . Australian Bureau of Statistics. Canberra; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haaland C, van Den Bosch CK. Challenges and strategies for urban green‐space planning in cities undergoing densification: a review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2015;14(4):760–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Astell‐Burt T, Feng X, Mavoa S, Badland HM, Giles‐Corti B. Do low‐income neighbourhoods have the least green space? A cross‐sectional study of Australia’s most populous cities. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nairn K. Learning from young people engaged in climate activism: the potential of collectivizing despair and hope. Young. 2019;27(5):435–50. [Google Scholar]

- 22. VicHealth . How to co‐design with young Victorians. Melbourne: Victorian Government; 2019. [updated 11 June 2019; cited 08 November 2021] Available from: https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/media‐and‐resources/publications/co‐design [Google Scholar]

- 23. Burgess CP, Berry HL, Gunthorpe W, Bailie RS. Development and preliminary validation of the 'Caring for Country' questionnaire: measurement of an Indigenous Australian health determinant. Int J Equity Health. 2008;7(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Briggs J. The use of indigenous knowledge in development: problems and challenges. Prog Dev Stud. 2005;5(2):99–114. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kingsley JY, Townsend M, Henderson‐Wilson C. Exploring aboriginal people’s connection to country to strengthen human‐nature theoretical perspectives. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2013. [Google Scholar]