Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic and related restrictions can impact mental health. To quantify the mental health burden of COVID‐19 pandemic, we conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis, searching World Health Organization COVID‐19/PsycInfo/PubMed databases (09/29/2020), including observational studies reporting on mental health outcomes in any population affected by COVID‐19. Primary outcomes were the prevalence of anxiety, depression, stress, sleep problems, posttraumatic symptoms. Sensitivity analyses were conducted on severe mental health problems, in high‐quality studies, and in representative samples. Subgroup analyses were conducted stratified by age, sex, country income level, and COVID‐19 infection status. One‐hundred‐seventy‐three studies from February to July 2020 were included (n = 502,261, median sample = 948, age = 34.4 years, females = 63%). Ninety‐one percent were cross‐sectional studies, and 18.5%/57.2% were of high/moderate quality. The highest prevalence emerged for posttraumatic symptoms in COVID‐19 infected people (94%), followed by behavioral problems in those with prior mental disorders (77%), fear in healthcare workers (71%), anxiety in caregivers/family members of people with COVID‐19 (42%), general health/social contact/passive coping style in the general population (38%), depression in those with prior somatic disorders (37%), and fear in other‐than‐healthcare workers (29%). Females and people with COVID‐19 infection had higher rates of almost all outcomes; college students/young adults of anxiety, depression, sleep problems, suicidal ideation; adults of fear and posttraumatic symptoms. Anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic symptoms were more prevalent in low‐/middle‐income countries, sleep problems in high‐income countries. The COVID‐19 pandemic adversely impacts mental health in a unique manner across population subgroups. Our results inform tailored preventive strategies and interventions to mitigate current, future, and transgenerational adverse mental health of the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Keywords: anxiety, COVID‐19 pandemic, depression, mental health

Key points

A systematic review and meta‐analysis to quantify the impact of mental health burden of COVID‐19 pandemic and related restrictions.

The highest prevalence emerged for posttraumatic symptoms in COVID‐19 infected people (94%).

Females and people with COVID‐19 infection had higher rates of almost all outcomes.

In low‐/middle‐income nations, the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic symptoms is high.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since December 2019, a novel coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2), causing the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (COVID‐19) spread from Wuhan, China, worldwide, becoming a pandemic. 1 As of 01/13/2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) has reported over 90 million confirmed cases of COVID‐19 and over 1.9 million deaths. 2 Restrictions, such as social distancing, travel restriction, and quarantine, became necessary to reduce pandemic spread. 3 A large body of evidence exists regarding the physical effects of COVID‐19 on different groups of the population, including pregnant women, 4 pediatric patients, 5 or those with pre‐existing risk factors for COVID‐19. 6 However, comparatively fewer studies have evaluated the mental health consequences of COVID‐19. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 It also remains unclear whether nonclinical risk factors, such as sex, age, income‐level country data, are associated with adverse mental health consequences. 7 , 8 , 11

Learning from earlier severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS‐Cov‐1/MERS‐CoV) epidemics, COVID‐19 might heavily impact mental health. During SARS, healthcare workers (HCWs) reported concerns for personal safety and increased anxiety, depression, and psychotic symptoms, 12 and both perceived risk of contracting SARS and quarantine were associated with depression. 12 , 13 Working without adequate equipment and training had also detrimental effects on the mental health of HCWs. 14 The general population reported fear of contagion and infecting close contacts, loneliness, and boredom associated with quarantine, 11 as well as anxiety and insomnia. 14 Similar effects on mental health were also observed following the novel Influenza A (H1N1), Ebola, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) epidemics. 15 Since COVID‐19 has spread worldwide, the global negative mental health impact could be much higher. 7 , 8

Indeed, converging evidence suggests the COVID‐19 pandemic adversely affects mental health across different countries with different income and measures, 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 patient subpopulations, 20 , 21 , 22 and quarantine status. 23 , 24 A recent systematic review found that HCWs in direct contact with COVID‐19 patients were at higher risk for depression, anxiety, insomnia, distress, and indirect traumatization than other occupational groups. 25 The risk of psychological distress increased with quarantine duration and social isolation. 15 , 23 , 24 Furthermore, the likelihood of experiencing mental health concerns was disproportionately increased in those with pre‐existing psychiatric disorders, or physical conditions (epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, cancer, etc.). 20 , 21 , 22 , 26 , 27 Hence, summarizing evidence on the mental health effects of COVID‐19 in the general and specific subpopulations is of paramount importance. Previous evidence synthesis efforts were restricted to specific populations 20 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 28 , 29 or included mainly studies from Asia (almost 91%), with very few studies from other countries/continents. 9 , 10 Three previous meta‐analyses have pooled data on the prevalence of mental health outcomes in the general population; however, many studies have been published since the most recent one, and all previous meta‐analyses narrowed inclusion criteria to a restricted set of outcomes of interest. 30 , 31 , 32 The aim of our work is to conduct a focused meta‐analysis to summarize the mental health impact of COVID‐19 pandemic during the first 6 months of the pandemic, without restrictions on outcomes or population.

2. METHODS

This meta‐analysis followed a protocol (https://osf.io/3ary9/) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) statement recommendations 33 (Supporting Information). Study selection flowchart is provided in Figure S1.

We searched the WHO COVID‐19/PsycInfo/PubMed databases, last search 09/29/2020 (for details, see Supporting Information Methods). Two authors (E. D., K. T.) independently screened title/abstracts. A third author (M. S.) resolved any disagreement. Coprimary outcomes were the prevalence of anxiety, depression, stress, sleep problems, and posttraumatic symptoms. Secondary outcomes were the prevalence of any other mental health problem (e.g., anger, suicidal ideation, hostility, fear, wellbeing etc.). Since we measured prevalence, outcomes were all categorical (e.g., including percentage/number of individuals scoring higher than scales' thresholds, or meeting criteria for outcomes).

Included were peer‐reviewed observational studies (surveys, cross‐sectional, case‐control, cohort) reporting on primary/secondary outcomes in any population group in countries affected by COVID‐19. In case of duplicate data, we used the more recent/larger sample. We grouped populations, for example, those with psychiatric disorders, COVID‐19‐infected patients (authors' definition), HCWs. No restriction was applied to mental health outcomes, nor language, or setting.

Exclusion criteria were: country/period not exposed to COVID‐19, case reports/series, reviews, qualitative studies, commentaries/narrative letters to editors/editorial comments without quantitative primary data, animal studies, intervention studies, studies not reporting data needed to compute prevalence with 95% confidence interval (CI) of mental health problems.

Six authors extracted data (H. L., K. H. L., J. C., J. K. Y., J. C., and E. D.), including study author, year, country, dates, population, study design, sample size, age, outcome instruments, type of survey, outcome prevalence (nominator/denominator), and 95%CIs. For case–control studies, we extracted prevalence rates among cases and controls separately. For cohort studies with multiple time points, we used the median time point. A third author resolved any disagreement (J. I. S.).

Quality was assessed with Newcastle−Ottawa Scale (NOS) 34 , 35 for cohort/case‐control studies, with the Agency for Research and Health Quality (AHRQ) Methodology Checklist for Cross‐sectional Study/Prevalence (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK35156/) 36 , 37 (Table S1) for cross‐sectional studies.

Random‐effect meta‐analyses of prevalence with 95%CIs (calculated if not reported, see Supporting Information Methods) 38 were performed by the target population, using metaprop packages in Stata. 39 , 40 The 95%CIs of the pooled prevalence rate was calculated using the cimethod (exact) and the Freeman Tukey double arcsine transformation (ftt command), which computes the weighted pooled estimate and performs the back transformation on the pooled estimate. 39 This method has properties that make it the clearly preferred option over other choices (e.g., logit transformation). 41

Heterogeneity was calculated as the I 2. 42 Publication bias was assessed if ≥10 studies using Egger test (p < 0.10), and visual funnel plot inspection. 43 , 44 Sensitivity analyses were conducted on studies that reported severe psychosocial/psychiatric symptomatology as defined by cut‐off scores or prevalence rates from the original articles, were of high quality, and included representative samples. Subgroup analyses were conducted by age, sex, country gross national income (Supporting Information Methods), and COVID‐19 infection (authors' definition). A univariate random‐effects meta‐regression was applied to investigate factors potentially contributing to the between‐study heterogeneity for the main outcomes 45 followed by multivariate analyses with those variables with p < 0.10 in the univariate analyses. We used Stata 13. 46

3. RESULTS

Out of 4242 records after removing duplicates, 313 full texts were assessed, 140 of which were excluded (Table S2), and 173 included (Figure S1; Table S3).

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

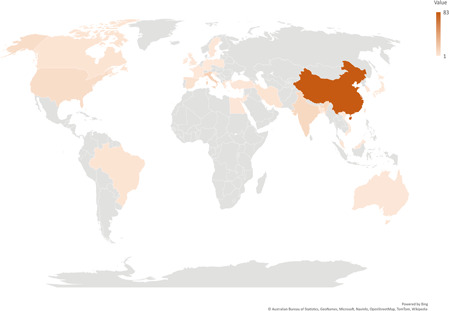

Included studies reported on 1237 estimates, from 502,261 participants from 32 countries. Figure 1 depicts the map graph of included studies across countries. About half of the studies (48%) were conducted in China, 8% in Italy, 6% in India, 4% in the USA, 7% in multiple countries. The median number of participants was 948 (interquartile range [IQR] = 343–2065) and the median sample mean age was 34.4 years (IQR = 30.5−42). The percentage of female participants ranged from 9% to 100% (median = 63%). Most studies examined the mental health impact of COVID‐19 in the general population (34%, all ages) and HCWs (31%), 6% in college/university students, and 5% in COVID‐19‐infected patients and patients with a somatic disorder. Three to seven studies (2%−4%) examined the consequences of the pandemic in other subgroups.

Figure 1.

Heat map chart of included studies across countries; darker color represents higher number of studies

Most studies (91%) were cross‐sectional, 5% of studies were either case−control or cohort studies, while 4% did not report the study design. Altogether 159 (91%) studies used validated self‐report instruments with thresholds, only one 47 used the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)‐10 criteria 48 to evaluate mental health diagnoses. The most common instruments were the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD‐7), Impact of Event Scale‐Revised (IES‐R), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Checklist for DSM‐5 (PCL‐5), and the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS‐21). No study clearly stated the primary outcome. Common mental health outcomes across studies were anxiety symptoms (18 instruments), depression symptoms (20 instruments), stress (15 instruments) posttraumatic symptoms (9 instruments), and sleep problems (5 instruments). The list of instruments used to measure the symptoms and the respective cut‐offs are reported in Table S4.

Only six studies reported data on race and ethnicity, and three studies involved multilanguage surveys (maximum = 2 languages). Snowball/convenience sampling was the most common recruitment method, and only three studies included representative samples. 49 , 50 , 51 No study accounted for infection rates. Fifteen studies reported data on confirmed COVID‐19 cases, 12 also reported estimates of mental health measurements before the pandemic (seven cross‐sectional, one case−control, two cohort, two without specifying design). However, data for a pre‐post meta‐analysis were available in only six of those studies. Studies collected data between 02/2020 and 07/2020. Thirty‐two studies (18.5%) met AHRQ/NOS scale high‐quality, 99 (57.2%) moderate, 42 studies (24.3%) low quality (agreement 89%).

3.2. Primary outcomes

Prevalence estimates for primary outcomes across different population groups are reported in Table 1. In patients with mental disorders and in COVID‐19‐infected patients, sleep problems and PTSD symptomatology were most prevalent (34% and 32% and 63% and 94%, respectively) without evidence for publication bias for anxiety/depression symptoms (Figures S2−S5).

Table 1.

Summary of pooled prevalence of mental health symptoms in various populations

| Mental health problem | No. of prevalence estimates | Pooled prevalence (95%CI) Random effects | I 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General population (all ages) | |||

| Depression | 201 | 0.20 (0.18−0.21) | 99 |

| Anxiety | 200 | 0.21 (0.19−0.23) | 99 |

| Stress | 91 | 0.20 (0.16−0.24) | 99 |

| Sleep problems | 41 | 0.35 (0.29−0.41) | 99 |

| PTSD symptomatology | 13 | 0.18 (0.11−0.25) | 98 |

| Miscellaneous a | 22 | 0.38 (0.23−0.54) | 99 |

| Behavior problem | 12 | 0.10 (0.06−0.16) | 99 |

| Psychological abnormality | 9 | 0.19 (0.08−0.34) | 99 |

| Somatization | 8 | 0.15 (0.06−0.28) | 99 |

| Paranoid ideation | 6 | 0.16 (0.04−0.34) | 99 |

| Hostility | 5 | 0.15 (0.02−0.38) | 99 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 5 | 0.16 (0.03−0.37) | 99 |

| Obsessive‐compulsive symptoms | 5 | 0.16 (0.03−0.37) | 99 |

| Suicidal ideation | 5 | 0.11 (0.01−0.31) | 99 |

| Substance use | 4 | 0.13 (0.05−0.23) | 99 |

| Fear | 1 | 0.19 (0.18−0.20) | NA |

| Patients with mental disorders | |||

| Anxiety | 15 | 0.26 (0.17−0.37) | 97 |

| Depression | 11 | 0.19 (0.14−0.23) | 85 |

| Stress | 8 | 0.16 (0.14−0.19) | 32 |

| Sleep problems | 3 | 0.34 (0.20−0.50) | NA |

| PTSD symptomatology | 2 | 0.32 (0.21−0.43) | NA |

| Anger | 1 | 0.21 (0.13−0.32) | NA |

| Suicidal ideation | 1 | 0.12 (0.06−0.21) | NA |

| Eating disorder | 1 | 0.38 (0.21−0.56) | NA |

| Behavior problem | 1 | 0.77 (0.73−0.81) | NA |

| Miscellaneous a | 1 | 0.50 (0.31−0.69) | NA |

| COVID‐19 infected patients | |||

| Depression | 29 | 0.28 (0.21−0.36) | 96 |

| Anxiety | 24 | 0.29 (0.18−0.42) | 98 |

| Stress | 7 | 0.29 (0.13−0.49) | 98 |

| Sleep problems | 3 | 0.63 (0.23−0.94) | NA |

| PTSD symptomatology | 2 | 0.94 (0.92−0.96) | NA |

| Fatigue | 1 | 0.54 (0.37−0.69) | NA |

| Miscellaneous a | 1 | 0.44 (0.28−0.60) | NA |

| Patients with a somatic disorder | |||

| Anxiety | 7 | 0.31 (0.21−0.41) | 94 |

| Depression | 4 | 0.37 (0.24−0.51) | 93 |

| Stress PTSD symptomatology | 3 | 0.25 (0.10−0.43) | NA |

| PTSD symptomatology | 3 | 0.10 (0.02−0.24) | NA |

| Sleep problems | 2 | 0.23 (0.21−0.25) | NA |

| Personality disorders | 4 | 0.01 (0.00−0.01) | 0 |

| Substance use | 4 | 0.03 (0.00−0.08) | 92 |

| Schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder | 2 | 0.01 (0.00−0.02) | NA |

| Bipolar disorder | 1 | 0.04 (0.02−0.08) | NA |

| Hostility | 1 | 0.14 (0.13−0.14) | NA |

| Organic psychosis | 1 | 0.01 (0.00−0.03) | NA |

| Miscellaneous (Multiple diagnoses) | 1 | 0.11 (0.07−0.15) | NA |

| Healthcare workers (HCWs) | |||

| Depression | 106 | 0.23 (0.19−0.28) | 98 |

| Anxiety | 103 | 0.24 (0.21−0.35) | 98 |

| Stress | 53 | 0.33 (0.26−0.40) | 99 |

| Sleep problems | 38 | 0.37 (0.31−0.44) | 96 |

| PTSD symptomatology | 19 | 0.27 (0.21−0.35) | 97 |

| Psychological abnormality | 16 | 0.27 (0.17−0.37) | 98 |

| Burnout | 14 | 0.41 (0.26−0.57) | 98 |

| Somatization | 7 | 0.15 (0.08−0.22) | 98 |

| Suicidal ideation | 3 | 0.09 (0.06−0.13) | NA |

| Miscellaneous a | 3 | 0.22 (0.11‐0.35) | NA |

| Obsessive‐compulsive symptoms | 2 | 0.14 (0.13−0.16) | NA |

| Fear | 1 | 0.71 (0.69−0.73) | NA |

| Fatigue | 1 | 0.35 (0.33−0.37) | NA |

| Hostility | 1 | 0.34 (0.30−0.38) | NA |

| Working population (other than HCWs) | |||

| Depression | 19 | 0.22 (0.13−0.31) | 99 |

| Sleep problems | 16 | 0.13 (0.09−0.17) | 97 |

| Anxiety | 14 | 0.08 (0.03−0.14) | 98 |

| Stress | 6 | 0.01 (0.00−0.03) | 84 |

| PTSD symptomatology | 3 | 0.14 (0.05−0.26) | NA |

| Somatization | 2 | 0.02 (0.01−0.02) | NA |

| Fear | 2 | 0.29 (0.25−0.33) | NA |

| Obsessive‐compulsive symptoms | 1 | 0.02 (0.01−0.03) | NA |

| Miscellaneous a | 1 | 0.19 (0.15−0.24) | NA |

| Caregivers and family members | |||

| Anxiety | 7 | 0.42 (0.24−0.60) | 98 |

| Depression | 5 | 0.21 (0.13−0.31) | 96 |

| Sleep problems | 2 | 0.06 (0.04−0.08) | NA |

| Stress | 1 | 0.07 (0.05−0.09) | NA |

| Anger | 1 | 0.32 (0.21−0.44) | NA |

| Suicidal ideation | 1 | 0.06 (0.02−0.14) | NA |

| Hopelessness | 1 | 0.03 (0.01−0.10) | NA |

| Pregnant women | |||

| Depression | 7 | 0.34 (0.28−0.40) | 96 |

| Anxiety | 6 | 0.38 (0.19−0.60) | 99 |

| Stress | 1 | 0.84 (0.71−0.94) | NA |

| Sleep problem | 1 | 0.53 (0.38−0.68) | NA |

| Eating disorder | 1 | 0.21 (0.18−0.24) | NA |

Note: Italics represents secondary outcomes.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HCWs, healthcare workers; I 2, heterogeneity metric; NA, not applicable; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

“Miscellaneous” represents low resilience, general health, loneliness, poor wellbeing, negative coping styles, worry, stigma, sadness, personality dysfunction, intrusive thoughts and avoidant behaviors.

In patients with a somatic disorder, anxiety/depression symptoms were most prevalent (31%/37%, respectively). In HCWs, stress and sleep problems were most prevalent (33% and 37%, respectively). Publication bias was detected for anxiety/depression symptoms, stress, and sleep problems in HCWs (Figures S6−S12).

In non‐HCW working populations, depression/PTSD symptomatology were most prevalent (22%/14%, respectively). Publication bias emerged for depression symptoms only (Figures S13−S15). In the general population, anxiety symptoms and sleep problems were most prevalent (21% and 35%, respectively). Publication bias affected estimates of anxiety, depression, posttraumatic symptoms, and sleep problems (Figures S16−S22).

In caregivers and family members of people with COVID‐19 or young adults in quarantine, anxiety/depression symptoms were most prevalent (42%/21%). In pregnant women, stress and sleep problems were most prevalent (84% and 53%, respectively).

3.3. Secondary outcomes

Prevalence estimates for secondary outcomes across different population groups are reported in Table 1. In patients with mental disorders, behavior problems were most prevalent (77%) and suicidal ideation was the least (12%). In COVID‐19‐infected patients, fatigue was most prevalent (54%) and miscellaneous (i.e., impaired general mental health) were the least (44%). In patients with a somatic disorder, hostility was most prevalent (37%) and organic psychosis, personality disorders, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorders were the least (1%). In HCWs, fear was most prevalent (71%) and suicidal ideation the least (9%). In non‐HCW working populations, fear was most prevalent (29%), and obsessive‐compulsive symptoms were the least (2%). In the general population, general outcomes were most prevalent (38%) and behavior problems the least (10%). In caregivers and family members of people with COVID‐19 or young adults in quarantine, anger was most prevalent (32%) and hopelessness the least (3%). In pregnant women the only reported secondary outcome was eating disorder with a prevalence of 21%.

3.4. Sensitivity analyses

Results of sensitivity analyses of severe mental symptoms (as indicated in original articles reporting the prevalence of most severe symptoms) are detailed in Table 2. Severe PTSD symptoms (96%) in COVID‐19‐infected patients were most prevalent; followed with rates ≥20% by severe PTSD symptoms (34%) in HCWs; severe stress symptoms (32%) and severe depression symptoms (29%) in college students; severe depression symptoms (27%) in the elderly; severe sleep problems (27%) in HCWs; severe anxiety symptoms in patients with a somatic disorder (26%); severe anxiety in HCWs (26%); severe stress (26%) and severe depression symptoms (21%) in COVID‐19‐infected patients. The least prevalent severe mental symptoms with rates <5% were severe depression symptoms (4%), severe anxiety (1%), severe stress (1%) and severe sleep problems (1%) in the non‐HCW working population; and severe suicidal ideation (1%) in the general population.

Table 2.

Summary of pooled prevalence of any severe mental health symptoms in various populations

| Population/Severe mental health problem | No. of prevalence estimates | Pooled prevalence (95%CI) Random effects | I 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | |||

| General population (adults) | 26 | 0.07 (0.06−0.09) | 99 |

| Healthcare workers (HCWs) | 21 | 0.11 (0.07−0.17) | 99 |

| College students and young adults | 10 | 0.12 (0.04−0.24) | 99 |

| COVID‐19 infected patients | 4 | 0.23 (0.01−0.87) | 99 |

| Working population (other than HCWs) | 4 | 0.01 (0.00−0.02) | 64 |

| Patients with mental disorders | 3 | 0.19 (0.08−0.34) | NA |

| Patients with a somatic disorder | 1 | 0.26 (0.18−0.34) | NA |

| Depression | |||

| General population (adults) | 29 | 0.07 (0.05−0.09) | 99 |

| Healthcare workers (HCWs) | 19 | 0.11 (0.07−0.17) | 99 |

| Patients with mental disorders | 5 | 0.16 (0.08−0.25) | 86 |

| COVID‐19 infected patients | 4 | 0.21 (0.03−0.48) | 97 |

| College students and young adults | 4 | 0.29 (0.11−0.52) | 99 |

| Children and adolescents | 3 | 0.08 (0.01−0.20) | NA |

| Working population (other than HCWs) | 2 | 0.04 (0.03−0.05) | NA |

| Patients with a somatic disorder | 1 | 0.18 (0.14−0.24) | NA |

| Elderly | 1 | 0.27 (0.21−0.34) | NA |

| Stress | |||

| General population (adults) | 20 | 0.12 (0.08−0.18) | 99 |

| Healthcare workers (HCWs) | 10 | 0.08 (0.03−0.15) | 98 |

| Patients with mental disorders | 4 | 0.17 (0.14−0.21) | 0 |

| COVID‐19 infected patients | 2 | 0.26 (0.22−0.31) | NA |

| Patients with a somatic disorder | 2 | 0.15 (0.11−0.18) | NA |

| Working population (other than HCWs) | 2 | 0.01(0.00−0.03) | NA |

| College students and young adults | 2 | 0.32 (0.27−0.36) | NA |

| Elderly | 1 | 0.10 (0.09−0.11) | NA |

| Sleep problems | |||

| Healthcare workers (HCWs) | 5 | 0.27 (0.07−0.55) | 99 |

| General population (adults) | 3 | 0.08 (0.02−0.17) | NA |

| Working population (other than HCWs) | 2 | 0.01 (0.00−0.01) | NA |

| Patients with mental disorders | 1 | 0.26 (0.17−0.38) | NA |

| PTSD symptomatology | |||

| Healthcare workers (HCWs) | 6 | 0.34 (0.16−0.55) | 99 |

| COVID‐19 infected patients | 1 | 0.96 (0.94−0.97) | NA |

| Working population (other than HCWs) | 1 | 0.11 (0.09−0.13) | NA |

| Behavior problem | |||

| General population (adults) | 2 | 0.05 (0.04−0.06) | NA |

| College students and young adults | 1 | 0.15 (0.09−0.22) | NA |

| Fear | |||

| Working population (other than HCWs) | 1 | 0.19 (0.15−0.25) | NA |

| Psychological abnormality | |||

| General population (adults) | 1 | 0.19 (0.17−0.22) | NA |

| Somatization | |||

| Healthcare workers (HCWs) | 3 | 0.13 (0.04−0.26) | NA |

| Suicidal ideation | |||

| General population (adults) | 1 | 0.01 (0.01−0.02) | NA |

Note: Italics represents secondary outcomes.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HCWs, healthcare workers; I 2 heterogeneity metric; NA, not applicable; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; italics, secondary outcomes.

Results of analyses limited to high‐quality studies are detailed in Table S5. Briefly, the highest mental health problem prevalence was for stress (84%) in pregnant women, followed for prevalence rates ≥40% by sleep problems (71%), stress (68%), and fatigue (54%) in COVID‐19‐infected patients; sleep problems (53%) in pregnant women; depression symptoms (44%) in COVID‐19‐infected patients; depression symptoms in non‐HCW working populations; and stress (40%) in HCWs. The least prevalent severe mental symptoms with rates <5% were sleep problems (4%) in caregivers/family members. In the three studies with representative samples, we found a depressive symptoms prevalence of 27%, severe mental distress prevalence of 19%, both in the general population.

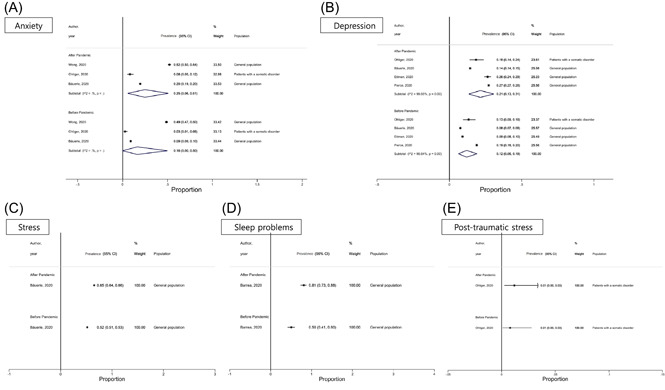

3.5. Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses' results are detailed in Tables 2, 3, and Tables S6, S7. Females had higher prevalence rates in almost all examined mental health problems, with few exceptions, namely burnout and psychological abnormalities. The younger strata of the population (college students) had higher prevalence rates of anxiety/depressive symptoms, sleep problems, and suicidal ideation. Adults had higher PTSD symptomatology and fear. Prevalence estimates of almost all examined mental health problems were higher in people affected by COVID‐19 infection or who had close contact with COVID‐19‐infected people. Finally, anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms were more prevalent in low‐/middle‐income countries, while sleep problems were more prevalent in high‐income countries. Figure 2 shows the prevalence rates of anxiety, depression, stress, sleep problems, and posttraumatic stress symptoms before and after the pandemic in studies with available data. Anxiety and depression increased by 9%, stress by 13%, sleep problems by 31% and PTSD symptoms remained unchanged.

Table 3.

Summary of pooled prevalence of any mental health problems by sex and age groups

| (A) Sex group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | |||||

| Mental health outcome | No. of prevalence estimates | Pooled prevalence (95%CI) | I 2 (%) | No. of prevalence estimates | Pooled prevalence (95%CI) | I 2 (%) |

| Anxiety | 37 | 0.19 (0.16−0.23) | 99 | 39 | 0.29 (0.24−0.34) | 99 |

| Depression | 38 | 0.21 (0.18−0.23) | 97 | 40 | 0.27 (0.24−0.31) | 99 |

| Stress | 15 | 0.19 (0.11−0.30) | 99 | 15 | 0.34 (0.20−0.49) | 99 |

| Sleep problems | 8 | 0.29 (0.18−0.41) | 98 | 10 | 0.47 (0.35−0.59) | 99 |

| PTSD symptomatology | 3 | 0.30 (0.21−0.41) | 87 | 3 | 0.37 (0.16−0.62) | NA |

| Burnout | 3 | 0.48 (0.20−0.77) | 98 | 4 | 0.43 (0.12−0.77) | 99 |

| Somatization | 1 | 0.13 (0.11−0.14) | NA | 1 | 0.21 (0.18−0.24) | NA |

| Psychological abnormality | 1 | 0.13 (0.09−0.16) | NA | 1 | 0.22 (0.21−0.23) | NA |

| Miscellaneousa | 3 | 0.20 (0.07−0.36) | 98 | 1 | 0.09 (0.06−0.13) | NA |

| (B) Age group | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minors (<18 years) | College students and young adults (18−29 years) | Adults (18−64 years) | Elderly (≥65 years) | |||||||||

| No. of prevalence estimates | Pooled prevalence (95%CI) | I 2 (%) | No. of prevalence estimates | Pooled prevalence (95%CI) | I 2 (%) | No. of prevalence estimates | Pooled prevalence (95%CI) | I 2 (%) | No. of prevalence estimates | Pooled prevalence (95%CI) | I 2 (%) | |

| Anxiety | 22 | 0.19 (0.14−0.24) | 99 | 51 | 0.28 (0.24−0.32) | 99 | 290 | 0.22 (0.20−0.24) | 99 | 13 | 0.20 (0.09−0.33) | 99 |

| Depression | 16 | 0.15 (0.10−0.21) | 99 | 48 | 0.31 (0.28−0.35) | 99 | 301 | 0.21 (0.19−0.22) | 99 | 17 | 0.17 (0.11−0.24) | 97 |

| Stress | 14 | 0.31 (0.18−0.46) | 99 | 147 | 0.23 (0.20−0.27) | 99 | 9 | 0.10 (0.01−0.29) | 99 | |||

| Sleep problems | 1 | 0.09 (0.06−0.14 | NA | 6 | 0.40 (0.24−0.57) | 99 | 95 | 0.33 (0.29−0.36) | 99 | 4 | 0.20 (0.15−0.25) | 92 |

| PTSD symptomatology | 4 | 0.20 (0.04−0.44) | 99 | 37 | 0.24 (0.18−0.30) | 99 | ||||||

| Anger | ‐ | 2 | 0.26 (0.19−0.34) | NA | ||||||||

| Behavior problem | 1 | 0.06 (0.05−0.07) | NA | 1 | 0.15 (0.09−0.22) | NA | 11 | 0.15 (0.07−0.25) | 99 | |||

| Bipolar disorder | 1 | 0.04 (0.02−0.08) | NA | |||||||||

| Burnout | 14 | 0.41 (0.26−0.57) | 99 | |||||||||

| Eating disorders | 2 | 0.21 (0.18−0.24) | NA | |||||||||

| Fatigue | 2 | 0.35 (0.33−0.37) | NA | |||||||||

| Fear | 1 | 0.19 (0.18−0.20) | NA | 3 | 0.43 (0.13−0.76) | NA | ||||||

| Hostility | 7 | 0.17 (0.07−0.31) | 99 | |||||||||

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 5 | 0.16 (0.03−0.37) | 99 | |||||||||

| Obsessive‐compulsive symptoms | 8 | 0.14 (0.05−0.29) | 99 | |||||||||

| Organic psychosis | 1 | 0.01 (0.00−0.03) | NA | |||||||||

| Paranoid ideation | 6 | 0.16 (0.04−0.34) | 99 | |||||||||

| Personality disorders | 4 | 0.01 (0.00−0.01) | 0 | |||||||||

| Psychological abnormality | 25 | 0.24 (0.16−0.32) | 99 | |||||||||

| Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 2 | 0.01 (0.00−0.02) | NA | |||||||||

| Somatization | 17 | 0.13 (0.08−0.19) | 99 | |||||||||

| Substance use | 8 | 0.07 (0.03−0.13) | 98 | |||||||||

| Suicidal ideation | 1 | 0.63 (0.60−0.66) | NA | 9 | 0.06 (0.04−0.09) | 96 | ||||||

| Miscellaneousa | 2 | 0.64 (0.58−0.70) | NA | 3 | 0.54 (0.29−0.78) | NA | 26 | 0.29 (0.16−0.44) | 99 | |||

Note: italics, secondary outcomes

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; I 2, heterogeneity metric; NA, not applicable; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

“Miscellaneous” represents low resilience, general health, loneliness, poor wellbeing, negative coping styles.

Figure 2.

Pooled prevalence of anxiety (A), depression (B), stress (C), sleep problems (D), and posttraumatic stress (E) symptoms before and after COVID‐19 pandemic outbreak

3.6. Meta‐regression

Meta‐regression was performed for the main outcomes. Significant moderators of greater adverse impact in the final multivariate meta‐regression model (Table S8 and Figures S20−S62) included female versus male sex (p = 0.05) for greater anxiety, time of investigation (p ≤ 0.05, i.e., May 2020 and various combinations of months vs. January 2020) for greater depression, USA versus Asia (p = 0.002) for greater stress and use of a nonvalidated instrument for more sleep problems (p = 0.01). For PTSD symptoms, no significant associations were found.

4. DISCUSSION

In this systematic review and meta‐analysis, we provide a paramount picture of the mental health impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Summarizing evidence on the prevalence of >20 mental health outcomes from 173 studies, across 32 countries and 502,261 participants, we show that the pandemic is substantially associated with a high prevalence of mental health problems globally, but with specific effects across different population groups. Overall, based on only six studies with longitudinal data, an increase between 9% and 31% in the prevalence rates before and after the pandemic were found for anxiety, depression, stress, and sleep problems.

As the negative impact differed across specific groups, 28 , 52 these findings call for emergency actions preventing/targeting specific symptoms in particular subpopulations. For instance, the prevalence of mental health problems ranged from 1% for stress in non‐healthcare professionals to 94% for PTSD symptomatology in COVID‐19‐infected patients. Depression/anxiety symptoms, stress, and sleep problems prevalence ranged from 8% to 63% across different populations. Caregivers and family members, pregnant women, those with a somatic disorder, COVID‐19 infection or mental disorders had high anxiety symptoms prevalence (42%, 38%, 31%, 29%, 26% respectively). Depression symptoms were also high in those with a somatic disorder (37%) and pregnant women (34%). Stress was particularly high in pregnant women, HCWs, and COVID‐19‐infected patients (29%, 33%, and 84%, respectively). Again, people with COVID‐19 infection had most frequently sleep problems (63%), followed by pregnant women (53%), HCWs (37%), the general population (35%), and those with mental disorders (34%). PTSD symptoms were the highest in people with COVID‐19 infection (94%), the general population (35%), those with mental disorders (32%), and HCWs (27%).

The pandemic seems to adversely impact the mental health of patients with pre‐existing mental and physical conditions, including COVID‐19‐infected patients. Our findings suggest that one fourth have experienced anxiety, depression, and stress symptoms, while nearly three quarters reported experiencing sleep problems during the pandemic. The findings of our study are in line with the empirical experience of clinicians treating patients with physical and mental conditions in the COVID‐19 era, 53 as well as with previous literature demonstrating that symptoms of severe mental illness can be exacerbated by complex emergencies. 54

The mental health of HCWs who have been in the epicenter of this unprecedented public health crisis has also been significantly affected. It has been repeatedly shown that HCWs suffered substantial amounts of severe anxiety, depression, stress, posttraumatic symptoms, fatigue, burnout, and sleep problems, 28 , 55 , 56 while one study 57 found that fear was prevalent in nearly three quarters of HCWs, similarly to the immediate aftermath of previous epidemics. 15 , 55 , 58 HCWs have been more extensively researched so far compared with the other groups 25 ; however, publication and small study biases were present. Given the unparalleled pressure that frontline HCWs have been facing in these past months (amid increased media and public scrutiny), this possibly demonstrates the early realization of the vital need to support those who care for us. 59

In subgroup analyses, COVID‐19 seems to adversely affect mental health to a lesser extent in children, adolescents, and older adults, compared with younger (college students) and (middle‐aged) adults, although the overall prevalence rates still ranged from 6% to 20% for anxiety/depression symptoms, and sleep problems. These findings should be treated with extreme caution, as only 3% of the included studies reported results for children/adolescents/older adults. Anxiety/depression symptoms, sleep problems, and suicidal ideation prevalence estimates were higher in college students, while PTSD symptomatology and fear prevalence estimates were higher in (middle‐aged) adults. These results show that college students and middle‐aged/working‐age adults may represent a particularly vulnerable risk group. The finding that young people and college students experienced greatest psychological impact due to the pandemic compared with older adults, who are at much greater risk for medical complications and death by COVID‐19, may be due to the fact that younger adults are least able to isolate themselves and are at greatest risk of contracting/spreading the infection due to work‐related and other role‐related activities. 60 Given the current limited literature on the psychological impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on elderly populations, the results of large ongoing international studies are expected to shed more light on this age group. Females reported higher prevalence estimates of almost all examined mental health problems compared with males, with few exceptions. Moreover, anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptomatology prevalence estimates were higher in low‐income and middle‐income countries, while sleep problems prevalence was higher in high‐income countries. Finally, we found that the prevalence estimates of almost all examined mental health problems were higher in people who were infected by COVID‐19 or had close contact with infected people, suggesting the potential of both direct and indirect effects of COVID‐19 on mental health. 61

To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review and prevalence meta‐analysis is the largest and most comprehensive review on the mental health burden across various populations during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Our findings widen and complete the findings of two previous meta‐analyses, adding more than 100 studies the former one which included 63 studies 30 and around 40 studies to the latter 31 pooling data on a broader set of outcomes. Regarding outcomes, the latter meta‐analysis focused only on prevalence rates for depression, anxiety, insomnia, and PTSD, while this meta‐analysis focuses on more than five times the number of outcomes. Also, while the prevalence estimates in that work 31 have been provided by HCWs/citizens, our meta‐analysis goes more in depth providing specific and fine‐grained measures across many strata of the general population. Furthermore, 102 studies were added to a more recent meta‐analysis focusing on the prevalence of mental health problems during the pandemic. 62 The added value of such a granular approach is to inform tailored interventions and preventing strategies per population subgroup. Our work is also larger than one further previous meta‐analysis, 32 which failed to identify the poorer mental health status in health workers compared with the general population, which was instead shown in both a previous meta‐analysis on the effects of previous and current coronavirus pandemics 63 and again here in the context of estimates without any restriction in terms of outcomes and included population.

Appropriate tests for outcomes with ≥10 studies indicated significant publication bias and small‐study effects for many common outcomes, such as anxiety, depression, posttraumatic symptoms, sleep problems, but not all outcomes could be tested owing to low numbers of included studies for some outcomes.

5. LIMITATIONS

Finally, the present study has several limitations. First and most importantly, study designs, population characteristics, assessment methods and resulting findings were highly heterogeneous. However, meta‐analyses evaluating prevalence estimates showed substantially higher heterogeneity than meta‐analyses of other effect size metrics. 64 , 65 , 66 We tried to address this caveat by conducting subgroup analyses and meta‐regression analyses based on study‐level factors, examining potential sources of heterogeneity. Significant factors for higher heterogeneity were female sex for anxiety; time of the investigation, that is, May 2020 and combinations of various months (i.e., March to April) versus January 2020 for depression; study location, that is, USA versus Asia for stress; and use of unvalidated instruments for sleep problems. Second, most included studies were cross‐sectional and used self‐report instruments employing online surveys. Importantly, in studies using ICD‐10 diagnostic criteria, the prevalence estimates of mental disorders were much lower ranging from 1% to 3%. 47 As a result, no causal inferences can be made, and there is a possibility of recall or other biases related to self‐report instruments. Third, data on the change in the prevalence of mental health problems from before the pandemic to the time during the pandemic were restricted to only six studies. Finally, this meta‐analysis does not report on effect size estimates based on continuous data, as too few studies employed methods to measure syndromal ICD or DMS disorder prevalences. Fourth, we did not identify any study in Chinese, which might have left out studies published in Chinese not listed in the databases we searched.

6. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, the COVID‐19 pandemic is having a concerning impact on mental health globally, adversely affecting diverse symptom clusters in specific at‐risk populations differently. More multilanguage and multicountry studies are required, with larger sample sizes, that include multiple subgroups and account for the COVID‐19 pandemic course, ask about the mental health status at the time before the COVID‐19 pandemic as well as at the time of completing the survey, that also ask about mental healthcare‐seeking behaviors, access and adherence to care, and that also collect data in representative samples, ideally with interviews if attempting to estimate the prevalence of mental disorders. Policymakers and public health stakeholders should allocate resources for mental health promotion, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders during and after the COVID‐19 pandemic, in particular in women, younger adults, HCWs, and those with or caring for those with COVID‐19 infection. Screening, mental health promotion, and prevention/early intervention for mental disorders should also target pregnant women and their offspring, to prevent the transgenerational physical and mental health impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Based on our findings, governments and mental health agencies should adopt effective monitoring and screening programs to identify vulnerable subpopulations early and strategically during emergencies. Tailored telemedicine interventions for mental health first aid across different strata of the population based on their pathologies should also be timely planned and offered. Accessibility to mental health resources and official registries of public mental health needs should be further strengthened and enhanced nationally and globally.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

C. U. C. has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Angelini, Axsome, Gedeon Richter, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J, Karuna, LB Pharma, Lundbeck, MedAvante‐ProPhase, MedInCell, Medscape, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mylan, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Rovi, Servier, Sumitomo Dainippon, Sunovion, Supernus, Takeda, and Teva. He provided expert testimony for Janssen and Otsuka. He served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck, Rovi, Supernus, and Teva. He has received grant support from Janssen and Takeda. He is also a stock option holder of LB Pharma. A. A. has received honoraria and travel support from Janssen‐Cilag, Bausch Health, ELPEN, and Lundbeck in the past 2 years. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Elena Dragioti, Marco Solmi had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Elena Dragioti and Marco Solmi and Jae Il Shin designed the project. Elena Dragioti and Konstantinos Tsamakis searched the literature, Han Li, Keum Hwa Lee, Jiwoo Choi, Jiwon KimY, Jiwoo Choi, and Elena Dragioti extracted the data, Elena Dragioti and George Tsitsas assessed the quality of included studies, and Elena Dragioti ran the analysis. Elena Dragioti and Han Li contributed equally to this study. All authors approved the protocol, and drafted the manuscript, provided critical comments to the paper for important intellectual content, and approved the final version.

Supporting information

Supporting information.

Dragioti E, Li H, Tsitsas G, et al. A large‐scale meta‐analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID‐19 early pandemic. J Med Virol. 2022;94:1935‐1949. 10.1002/jmv.27549

Elena Dragioti and Han Li are joint first authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web‐based dashboard to track COVID‐19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):533‐534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pan A, Liu L, Wang C, et al. Association of public health interventions with the epidemiology of the COVID‐19 outbreak in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1915‐1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trippella G, Ciarcià M, Ferrari M, et al. COVID‐19 in pregnant women and neonates: a systematic review of the literature with quality assessment of the studies. Pathogens. 2020;9(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tung HoCL, Oligbu P, Ojubolamo O, Pervaiz M, Oligbu G. Clinical characteristics of children with COVID‐19. AIMS Public Health. 2020;7(2):258‐273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aly MH, Rahman SS, Ahmed WA, et al. Indicators of critical illness and predictors of mortality in COVID‐19 patients. Infect Drug Resist. 2020;13:1995‐2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gruber J, Prinstein MJ & Clark LA et al. Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID‐19: challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. Am Psychol. 2021;76(3):409‐426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID‐19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(5):460‐471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, Menon V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID‐19 patients amidst the COVID‐19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID‐19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531‐542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912‐920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(5):302‐311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):15‐23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maunder R, Hunter J, Vincent L, et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003;168(10):1245‐1251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kisely S, Warren N, McMahon L, Dalais C, Henry I, Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID‐19 outbreak in China: a web‐based cross‐sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mazza C, Ricci E, Biondi S, et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID‐19 pandemic: immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9).3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sonderskov KM, Dinesen PT, Santini ZI, Ostergaard SD. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020;32(4):226‐228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown? A case‐control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100‐106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hao X, Zhou D, Li Z, et al. Severe psychological distress among patients with epilepsy during the COVID‐19 outbreak in southwest China. Epilepsia. 2020;61(6):1166‐1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Termorshuizen JD, Watson HJ, Thornton LM, et al. Early impact of COVID‐19 on individuals with eating disorders: a survey of ~1000 Individuals in the United States and the Netherlands. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23. Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID‐19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhu S, Wu Y, Zhu CY, et al. The immediate mental health impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic among people with or without quarantine managements. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:56‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. da Silva FCT, Neto MLR. Psychiatric symptomatology associated with depression, anxiety, distress, and insomnia in health professionals working in patients affected by COVID‐19: a systematic review with meta‐analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2021;104:110057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Salari M, Zali A, Ashrafi F, et al. Incidence of anxiety in Parkinson's disease during the coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) Pandemic. Mov Disord. 2020;35(7):1095‐1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Y, Duan Z, Ma Z, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems among patients with cancer during COVID‐19 pandemic. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901‐907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lasheras I, Gracia‐García P, Lipnicki DM, et al. Prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review with meta‐analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18).6603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:91‐98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cénat JM, Blais‐Rochette C, Kokou‐Kpolou CK, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID‐19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arora T, Grey I, Ostlundh L, Lam KBH, Omar OM, Arnone D. The prevalence of psychological consequences of COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. J Health Psychol. 2020:1359105320966639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wells GASB, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M & Tugwell P The Newcastle−Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta‐analyses. 2012.

- 35. Solmi M, Firth J, Miola A, et al. Disparities in cancer screening in people with mental illness across the world versus the general population: prevalence and comparative meta‐analysis including 4 717 839 people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(1):52‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions‐‐agency for healthcare research and quality and the effective health‐care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(5):513‐523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Silva DFO, Sena‐Evangelista KCM, Lyra CO, Pedrosa LFC, Arrais RF, Lima S. Motivations for weight loss in adolescents with overweight and obesity: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schoenberg BS. Calculating confidence intervals for rates and ratios. Neuroepidemiology. 1983;2(3‐4):257‐265. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta‐analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177‐188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta‐analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(11):974‐978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557‐560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629‐634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Simmonds M. Quantifying the risk of error when interpreting funnel plots. Syst Rev. 2015;4:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Thompson SG, Higgins JP. How should meta‐regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1559‐1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. 2013. College Station, TX.

- 47. Ohliger E, Umpierrez E, Buehler L, et al. Mental health of orthopaedic trauma patients during the 2020 COVID‐19 pandemic. Int Orthop. 2020;44(10):1921‐1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The ICD−10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: conversion tables between ICD‐8 I‐aI‐. World Health Organization Division of Mental Health. 1994.

- 49. Ben‐Ezra M, Sun S, Hou WK, Goodwin R. The association of being in quarantine and related COVID‐19 recommended and non‐recommended behaviors with psychological distress in Chinese population. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:66‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2019686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):883‐892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID‐19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547‐560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tsamakis K, Triantafyllis AS, Tsiptsios D, et al. COVID‐19 related stress exacerbates common physical and mental pathologies and affects treatment (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(1):159‐162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jones L, Asare JB, El Masri M, Mohanraj A, Sherief H, van Ommeren M. Severe mental disorders in complex emergencies. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):654‐661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tsamakis K, Rizos E, Manolis AJ, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic and its impact on mental health of healthcare professionals. Exp Ther Med. 2020;19(6):3451‐3453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid‐19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510‐512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a cross‐sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:127‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dzau VJ, Kirch D, Nasca T. Preventing a parallel pandemic—a national strategy to protect clinicians' well‐being. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):513‐515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, et al. COVID‐19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):926‐929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tisdell CA. Economic, social and political issues raised by the COVID‐19 pandemic. Econ Anal Policy. 2020;68:17‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liu X, Zhu M, Zhang R, et al. Public mental health problems during COVID‐19 pandemic: a large‐scale meta‐analysis of the evidence. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Salazar de Pablo G, Vaquerizo‐Serrano J, Catalan A, et al. Impact of coronavirus syndromes on physical and mental health of health care workers: systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:48‐57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Assefa A, Bihon A. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of prevalence of Escherichia coli in foods of animal origin in Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2018;4(8):e00716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bacigalupo I, Mayer F, Lacorte E, et al. A systematic review and meta‐analysis on the prevalence of dementia in Europe: estimates from the highest‐quality studies adopting the DSM IV diagnostic criteria. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(4):1471‐1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Alba AC, Alexander PE, Chang J, MacIsaac J, DeFry S, Guyatt GH. High statistical heterogeneity is more frequent in meta‐analysis of continuous than binary outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;70:129‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.