Abstract

COVID‐19 has become a global public health obstacle. This disease has caused negligence on mental health institutions, decreased trust in the healthcare system and traditional and religious beliefs, and has created a widespread stigma on people living with mental health illness, specifically in Nigeria. The increase of COVID‐19 cases that have exhausted the healthcare system in Nigeria have brought further negligence to people living with mental disorder, thus increasing the burden of the disease on these patients. Overall, this article considerably highlighted the need for equal accessibility to healthcare resources, as well as the requirement of proper attention and care for mental health patients in Nigeria. This article discusses the challenges that surfaced because of the COVID‐19 pandemic on people living with mental illness and their implications, as well as suggesting necessary actions and recommendations.

Keywords: COVID‐19, equity in healthcare, mental health, Nigeria

Highlights

In Nigeria, only about 15% of patients with severe mental illnesses have access to mental health care.

In Nigeria, the COVID‐19 pandemic has caused negligence on mental health institutions and created a widespread stigma on people living with mental health illnesses.

People in Nigeria lack basic understanding about mental health illnesses and have various misconceptions for its underlying causes.

It is critical to strengthen Nigeria's health‐care system, particularly during COVID‐19, by devising measures to improve mental health literacy and change stigmatizing attitudes at both the institutional and community levels.

1. COVID‐19 PANDEMIC IN NIGERIA

At the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic in early 2020, the world and many international organizations were concerned about the possible effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the African continent. The healthcare systems in the continent, already under strain under normal conditions, could easily crumble during the pandemic, due to shortage of resources, including ventilators and hospital facilities. 1

Additionally, many were also preoccupied with the fact that many preventative measures, including social distancing and hygiene practices could not be easily implemented and adapted in some parts of the continent due to the work culture and lifestyle in the various existing communities. 1 While predictions were far worse than reality, COVID‐19 is continuously posing a great a threat to the African continent, and Nigeria is not exempt. The country declared its first case in February 2020, and as of 7 May 2021, 1 there have been 166,098 cases registered, making Nigeria the eighth most affected country of the African continent. 2 Observing the trend of new COVID‐19 cases in the country, one can observe that there has been a significant decrease in the incidence rate compared to the wave witnessed in January 2021, which was the second wave in the country. 3

However, the figures representing the extent of spread of the disease in Nigeria might not be accurate due to the limited available testing resources and the economic and logistical capabilities. 4 There have also report that distrust in the government increased the lack of reporting of cases and the non‐compliance with social distancing measures in the country. 5 Other factors that have affected the development of the COVID‐19 pandemic in Nigeria include the corruption of the health sector, weakness of the healthcare system, as well as the spread of misinformation regarding public health measures and policies that have been circulating through media platforms. 5

On the other hand, research study suggested that the public‐private partnerships approached by the government were efficient in disseminating public health communication and prevention messages amongst the population. 6 As a result, this seems to have contributed to the recent decrease in the number of new cases of COVID‐19, joined by a combination of lockdown and social distancing measures, as well the vaccination program strategies. While useful, these measures have not happened without greatly affecting the Nigerian population, in particular those with mental health issues. 4

2. STATE OF PEOPLE LIVING WITH MENTAL DISORDER IN NIGERIA

Mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety are highly rampant in low‐ and middle‐income countries like Nigeria. 7 , 8 People in Nigeria lack adequate knowledge regarding mental health disorders and have various misconceptions for its underlying causes such as drug and alcohol use (80.8%), possession by evil spirits (30.2%), traumatic event or shock (29.9%), stress (29.2%), and genetic inheritance (26.5%), and very few people believe that biological factors or brain diseases are the underlying cause of the development of these disorders. 7

There is no local, authentic data regarding mental illness prevalence in the Nigerian community and reports show very low prevalence for depressive and anxiety disorders (3.1% lifetime depression, 5.7% lifetime anxiety), leading to exclusion of data from national WMHS (World Mental Health Survey) epidemiology reports. 8 All this eventually resulted in failure of gaining much attention at the local and international levels towards this serious issue and has become more critical, especially amidst the COVID‐19 pandemic. 9

A study reported that the most common depressive symptoms among depressed patients in Nigeria were anhedonia 9.1%, suicidal ideation 7.3%, hopelessness 6.9% and 1.8% psychomotor retardation. Similarly, generalized anxiety disorder patients reported worrying too much about different things (12.3%), easily annoyed (11.1%) and inability to control worrying (7.3%). 9 Stigmatizing behaviour towards mentally ill people is very well documented in Nigeria, which is prevalent among all the classes and categories of the society. This behaviour negatively affects the patient's quality of life as well as creates a barrier in accessing mental health care, apart from spreading misconceptions regarding the causes of mental illnesses in the community. 8

3. HOW COVID‐19 AFFECTS PEOPLE LIVING WITH MENTAL DISORDER IN NIGERIA?

The SARS‐CoV‐2 virus was previously believed to be restricted to the respiratory system, majorly affecting the lungs, however, recent studies explained its multisystem involvement, especially involving the brain tissue. The COVID‐19 disease may be linked directly or indirectly to many psychiatric problems like post‐traumatic stress disorder, obsessive‐compulsive disorder, anxiety, delirium, and depression. It either can aggravate previous mental health issues or can lead to a new onset of psychiatric disorders. 10

Rising cases of COVID‐19, increased disease burden, and loss of social support can lead to short‐term mental health issues while economic losses due to imposed lockdowns in Nigeria can have a long‐term impact on the mental health of people. 11

Psychiatric patients are also at an increased risk of transmitting COVID‐19 infection by not strictly following preventive measures. Cognitive impairment in these patients poses a big challenge on SOPs, including hand hygiene, safe cough practices, self‐isolation, and wearing facemasks. Mental health patients have low self‐esteem and less ability to cope with stress than the public, which leads to an increased infectivity rate in psychiatric patients. If such patients contract the virus, the risk of re‐infection is even greater due to heightened stress in quarantine conditions and feelings of loneliness, social isolation, and despair. Attention was paid to emotional disturbances in COVID‐19 patients, frontline workers, and the public, but no attention was given to patients having pre‐existing mental health conditions. 12

A worldwide shortage of frontline workers aimed at overcoming the pandemic led to the redeployment of psychiatrists to critical care units to manage COVID‐19 patients in many countries. Consequently, this led to the closure of mental hospital OPDs and a huge surge of mental health issues in Nigeria. Imposed lockdowns and restricted rules of physical isolation deprived many patients of basic mental health care in this country. 13

Homeless people with mental health issues wandering in the streets of Nigeria have also imposed an economic burden on the state during the worst scenario of this COVID‐19 pandemic. These people are frequently deprived of food, shelter, clothing, quality care, and basic healthcare facilities. Furthermore, they are often exposed to physical, sexual, and various other forms of human rights abuses. There are high chances of contracting the virus in these groups and the state should pay special attention to providing basic health facilities for them.

4. CHALLENGES FACED BY PEOPLE LIVING WITH MENTAL DISORDER DURING COVID‐19 PANDEMIC

The COVID‐19 pandemic has exposed the weak health systems and the large treatment gap in mental health across Nigeria low‐ and middle‐income countries. 14 Because of these problems patients with serious mental illness die earlier, suffer from more medical illnesses, and receive worse medical care compared to those in the general population. 15

COVID‐19 pandemic led to severe long‐term consequences on mental health in the most impoverished and lowest‐resourced regions of the globe like Nigeria, where there was no access to mental health services before the COVID‐19 pandemic. 16 The situation of people living with mental disorder has become significantly concerning recently.

In Nigeria, the predominant belief system that mental illness is caused by unnatural forces and evil spirits led some Nigerians to resort to faith‐based institutions and traditional healing homes in search of healing. Thousands of people with serious mental health illnesses in Nigeria are admitted to these centers, where they often undergo terrible episodes of abuse. 17 , 18

For the benefit of enhanced prevention and control of infection to reduce the exposure of nurses and ensure proper physical distancing at work, arrangement in the work schedule of nurses was maintained, but the number of nurses present in the wards has been reduced. New admissions of people with mental illness into institutions are hampered due to this strategy. 19 The drop in staff numbers in mental health services due to possible infection ofin health workers with a need to self‐quarantine may affect services like routine psychiatrist reviews, focus on medication adherence and routine case manager visits. 19 Moreover, patients with serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, are further negatively affected by stay‐at‐home orders and subsequent reduction in their access to employment opportunities, thus worsening their financial distress. 20

However, during the COVID‐19 pandemic, when they are suffering from more distress, mentally ill patients experience significant reductions in availability of care. 21 Immature discharge from psychiatric units may lead to relapse, depression, anxiety, suicidal behaviour, and post‐traumatic incidents. 22 , 23 Mental health disorder comorbidities combined with COVID‐19 will make the treatment more challenging and potentially less effective. 24 , 25 Many people with mental health disorders attend regular outpatient clinics for routine case manager visits. However, currently these regular visits are more difficult and impractical to attend due to nationwide regulations on travel and quarantine. 26

5. IMPLICATIONS

As the pandemic ravages Nigeria and the whole of the continent, the mental health of the people has taken a turn for the worse. People are experiencing high degrees of depression, post‐traumatic stress disorder, and general anxiety, which may contribute to further psychological trauma and exaggerate into neuropsychiatric disorders. 27 The mentally challenged were rebuked, verbally and physically assaulted by the general people, but as of now, the fear of COVID‐19 has increased these attacks on the already socially marginalized people in Nigeria. 28

Strict lockdown laws in the country and specifically in Lagos and other urban state in Nigeria had a direct effect on the help provided by different NGOs to the mentally challenged people. Due to the restrictions in the movement, help could not reach people at demanding locations, and as a result, NGOs could not have the capacity to provide basic support to the needy. Furthermore, the ability of people to seek healthcare also diminished. 28 This also includes the hospitalization of mentally challenged who are uncared for, which further deteriorates their condition. Philanthropist and volunteer work too saw setbacks due to COVID‐19 lockdown. For example, the distribution of food and other essential services earlier given by volunteers have stopped due to the fear of catching the disease. It is seen that homeless mentally challenged people are more prone to COVID‐19 due to poor nutrition and inability to follow protective measures which can lead to community transmission of the COVID‐19.

6. EFFORTS

The first step towards mitigating a problem is recognizing that there is a problem in the first place. Dealing with an emergent issue like the COVID‐19 pandemic, especially for a LMIC such as Nigeria, meant that other issues got sidelined.

Primarily, an organization called the Nigerian Psychological Association (NPA) responded by forming member COVID‐19 National Response Committee, whereby a national response protocol and factsheet was developed. 29

Following the guidelines, the NPA formed committees in their state chapters to offer support at the state level. In these committees, some of the agendas included supporting the overall governments effort to sequester the amount of fear and despair, instead, focussing the narrative to give people assurance that with the government's help they will be able to combat COVID‐19 as they did Ebola.

Among other things, there was awareness campaigns through which domestic violence, substance use disorders, mental illness, in particular depression, anxiety and post traumatic stress disorders were reeled in to focus. The NPA was also behind the development and circulation of COVID 19 factsheets, which included documents titled; Psychological Measures to Mitigate the Psychosocial Impact of COVID‐19, Lockdown and Psychosocial Well‐Being of People and Society and COVID 19 and Psychological Services.

By virtue of the endeavours of the National Resource Committee, a jingle was televised. It accentuated the need for psychological support in individuals with a positive test result and broadcasted the free tele‐psychological services provided by the NPA. Steps were taken to assure proper assessment and interventions for mental health issues; psychosocial support counselling, psychotherapy for healthy adjustment to COVID 19 and lockdown, post COVID‐19 community counselling, 29 being a few of them. For people in quarantine and isolation centers, psychological evaluation before and after this period was arranged. Frontline health workers were provided with counselling, psychotherapy and online training on self‐care.

Mentally aware Nigerian initiatives provided free of cost online sessions to individuals at home with anxiety disorders. Organizations such as the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) promoted use of psychological first aid with remote deliveries for groups of people, such as those with previous mental and substance use disorders. 30

7. RECOMMENDATIONS

Nigeria has below 15% of people with severe mental illness having access to mental health care services. 31 The urgency of the COVID‐19 pandemic in Nigeria has increased the attention to care for mentally ill people in the hospital and those outside especially, those that move on the street with no care and attention. This describes the need for mental health literacy in all levels of education and awareness about mental health education to help people living with mental disorder.

Stigmatization about people living with mental disorder increases greatly during COVID‐19 as people who are helping them before with foods are still recovering from the impact of COVID‐19, thereby reducing their attention to them. There is a need for better understanding of mental illness that would significantly improve knowledge and attitude towards people living with mental disorder.

There is an urgent necessity to improve the health care system in Nigeria especially during COVID‐19, by developing strategies that would improve mental health literacy, and change stigmatizing attitudes at both institutional and community levels. This will in the end improve the quality of the societal attitude towards mental illness and the socio‐economy of the mental disorder.

One practical yet feasible way to improve literacy in mental health during COVID‐19 is by instituting age‐appropriate school‐based educational programmes. While complexities may arise in creating these educational programs, due to stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs in supernatural causation, which still exist among educated health workers, these programs might still, be a good way forward.

Another practical recommendation is to increase psychiatry clerkship rotations for medical students, beyond 4 weeks during COVID‐19 pandemic. This will help familiarize students more with mental health diseases outside their preconceived misconceptions and this will in turn encourage and increase awareness and care for people living with mental health among other students and various environment. In addition, it is necessary to encourage health workers (nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists and other health care professionals) to show a positive attitude towards people living with mental health disorder during COVID‐19, as they play an important role in influencing their response to treatment.

The role of the media in propagating attitudinal observation or changes towards patients affected by mental disorders should increase. The role of media can play a role in education or reducing stigma.

People with mental health conditions are often abused in various places in Nigeria, subject to years of unimaginable hardship. People with mental health conditions should be supported and provided with effective services in their communities, not chained and restricted. 32

In addition, it is necessary to undertake the widespread education of the Nigerian public on the recognition of mental health disorders as a disease and the need for societal and family support and the avoidance of stigmatization of people suffering from mental health disorders.

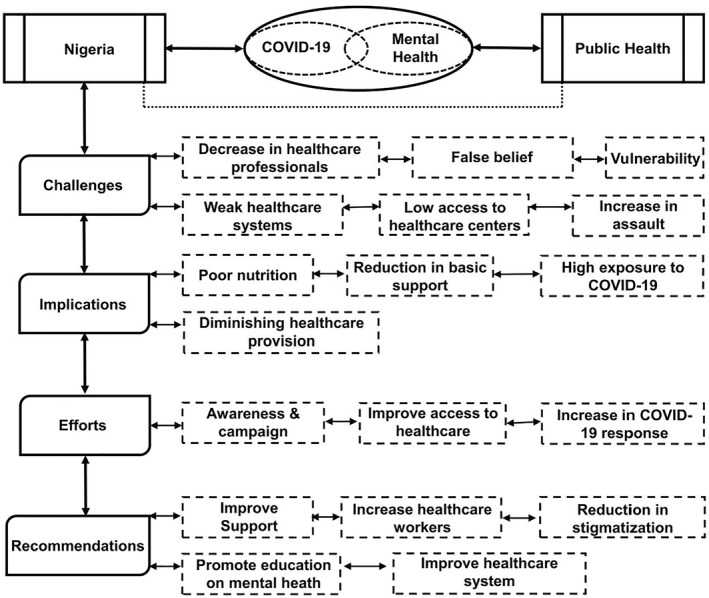

A summary of impact of COVID‐19 on people living with mental illness in Nigeria, challenges, implications, efforts and recommendations is provided in the Figure 1 below:

FIGURE 1.

An overview of impact of COVID‐19 on people living with mental illness in Nigeria

8. CONCLUSION

COVID‐19 has further highlighted health inequities in Nigeria and people with mental health disorders have been broadly affected. During the pandemic, the largest Nigerian government psychiatric hospitals consisted of few mental health professionals to serve the large population, which also affected the intake and attention given to those roaming around the street. However, more recently, community mental health services, which have shown to improve access to care and clinical outcomes, are beginning to develop in some locations. Despite efforts to promote accessible services, low levels of knowledge about effective treatment of mental disorders means that even where these services are available, a very small proportion of people utilize these services. Therefore, interventions to increase service use are an essential component of the health system.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The present study includes printed and published information; therefore, the formal ethical clearance was not applicable for this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No external funding was used in this study.

Aborode AT, Corriero AC, Mehmood Q, et al. People living with mental disorder in Nigeria amidst COVID‐19: Challenges, implications, and recommendations. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2021; 1‐8. 10.1002/hpm.3394

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ohia C, Bakarey AS, Ahmad T. COVID‐19 and Nigeria: putting the realities in context. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:279‐281. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32353547/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Worldometer . COVID‐19 Pandemic in Nigeria. Worldometer; 2021. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. COVID‐19 Pandemic in Nigeria: Nigeria Situation; 2021. https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/ng [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baiyewu O, Elugbadebo O, Oshodi Y. Burden of COVID‐19 on mental health of older adults in a fragile healthcare system: the case of Nigeria: dealing with inequalities and inadequacies. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(10):1181‐1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ezeibe CC, Ilo C, Ezeibe EN, et al. Political distrust and the spread of COVID‐19 in Nigeria. Global Publ Health. 2020;15(12):175301766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oleribe O, Ezechi O, Osita OP, et al. Public perception of COVID‐19 mangement and response in Nigeria: a cross‐sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10):e041936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Ephraim‐Oluwanuga O, Olley BO, Kola L. Community study of knowledge of and attitude to mental illness in Nigeria. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:436‐441. PMID: 15863750. 10.1192/bjp.186.5.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Audu IA, Idris SH, Olisah VO, Sheikh TL. Stigmatization of people with mental illness among inhabitants of a rural community in northern Nigeria. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59(1):55‐60. Epub 2011 Nov 29. PMID: 22131198. 10.1177/0020764011423180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adewuya AO, Atilola O, Ola BA, et al. Current prevalence, comorbidity and associated factors for symptoms of depression and generalized anxiety in the Lagos State Mental Health Survey (LSMHS), Nigeria. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;81:60‐65. Epub 2017 Nov 28. PMID: 29268153. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ojeahere MI, de Filippis R, Ransing R, et al. Management of psychiatric conditions and delirium during the COVID‐19 pandemic across continents: lessons learned and recommendations. Brain Behav Immun – Health. 2020;9:100147. 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Semo BW, Frissa SM. The mental health impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic: implications for Sub‐Saharan Africa. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:713‐720. 10.2147/PRBM.S264286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Muruganandam P, Neelamegam S, Menon V, Alexander J, Chaturvedi SK. COVID‐19 and severe mental illness: impact on patients and its relation with their awareness about COVID‐19. Psychiatr Res. 2020;291:113265. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adiukwu F, Orsolini L, Gashi Bytyçi D, et al. COVID‐19 mental health care toolkit: an international collaborative effort by Early Career Psychiatrists section. General Psychiatry. 2020;33(5):e100270. 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ojha R, Syed S. Challenges faced by mental health providers and patients during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic due to technological barriers. Internet Interv. 2020;21:100330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kola L, Kohrt BA, Hanlon C, et al. COVID‐19 mental health impact and responses in low‐income and middle‐income countries: reimagining global mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Viron MJ, Stern TA. The impact of serious mental illness on health and healthcare. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(6):458‐465. 10.1176/appi.psy.51.6.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The World Bank . Word Bank Country and Lending Groups. Accessed November 9, 2020. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519‐worldbank‐country‐and lending‐groups#:~:text=For%20the%20current%202021%20fiscal,those%20with%20a%20GNI%20per [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ifeagwazi CM. Trends in conceptualization of the etiology of psychopathology with a special focus on Euro‐American and African cultures. J Res Contemp Issues. 2006;2:84‐96. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ćerimović E, Ewang A. COVID‐19 Poses Extreme Threat to People Shackled in Nigeria; 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/30/covid‐19‐poses‐extreme‐threat‐peopleshackled‐nigeria# [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chukwuorji JC, Iorfa SK. Commentary on the coronavirus pandemic: Nigeria. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020;12:S188‐S190. 10.1037/tra0000786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kavoor AR. COVID‐19 in people with mental illness: challenges and vulnerabilities. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102051. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gautam M, Thakrar A, Akinyemi E, Mahr G. Current and future challenges in the delivery of mental healthcare during COVID‐19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;11:1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsamakis K, Tsiptsios D, Ouranidis A, et al. COVID‐19 and its consequences on mental health (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;21(3):244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moreno C, Wykes T, Galderisi S, et al. How mental health care should change as a consequence of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:813‐824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sartorius N. Comorbidity of mental and physical diseases: a main challenge for medicine of the 21st century. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2013;25:68‐69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yao H, Chen JH, Xu YF. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID‐19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Okpalauwaekwe U, Mela M, Oji C. Knowledge of and attitude to mental illnesses in Nigeria: a scoping review. Integr J Global Health. 2017;1:1. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ahmed SAKS, Ajisola M, Azeem K, et al. Impact of the societal response to COVID‐19 on access to healthcare for non‐COVID‐19 health issues in slum communities of Bangladesh, Kenya, Nigeria and Pakistan: results of pre‐COVID and COVID‐19 lockdown stakeholder engagements. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5:e003042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ezenwza M, Zamani A. Psychology in the Public Space in Nigeria: Lessons from the COVID‐19 Pandemic [online]; 2021. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://www.apa.org/international/global‐insights/nigeria‐covid‐19 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ezenwa M. Psychologists in Nigeria Respond to COVID‐19 [online]; 2021. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://www.apa.orghttps://www.apa.org/international/global‐insights/nigeria‐respond‐covid‐19 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Kola L, Makanjuola VA. Lifetime and 12‐month prevalence of mental disorders in the Nigerian survey of mental health and well‐being. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(5):465‐471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):878‐889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.