Since the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in 2019, the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the virus keeps evolving as transmission continues globally. On November 26, 2021, a highly divergent variant with a high number of mutations, the Omicron (PANGO lineage B1.1.529),1 was designated by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a variant of concern (VOC). The Omicron variant has been spreading rapidly than any other previous variants of SARS-CoV-2, and is currently the dominant variant worldwide that accounts for more than 95% of sequenced cases submitted to GISAID. Three subvariants of Omicron, including BA.1, BA.2, and BA.3, were detected in varying proportion in different parts of the world within weeks. The BA.2 subvariant, known popularly as the stealth Omicron variant which lacks a particular genetic signature that distinguishes it from the Delta variant, has been shown to be more transmissible than BA.1, and has quickly become the dominant strain in many countries.

Emergence of the new omicron XE subvariant that could be more transmissible

On March 25, 2022, the UK’s Health Security Agency (UKHSA) published a report, satating that it is monitoring three recombinants: XD, XE, and XF.2 The XD and XF variants are recombinants of Delta and Omicron BA.1. The XE subvariant, a recombinant of Omicron BA.1 and BA.2, was first detected via sequencing on January 19, 2022. The UKHSA has since recorded 637 cases of XE geographically distributed across the UK by March 22, suggesting community transmission. This subvariant has attracted attention globally because statistical models have shown early signs that XE has a growth rate 9.8% above that of BA.2.2 The WHO has issued a warning against XE, stating that it could be more transmissible than previous variants. However, with the number of confirmed cases being too small to be analyzed, the data could be biased. Further monitoring is required for the detailed evaluation of the growth rate and transmissibility of XE.

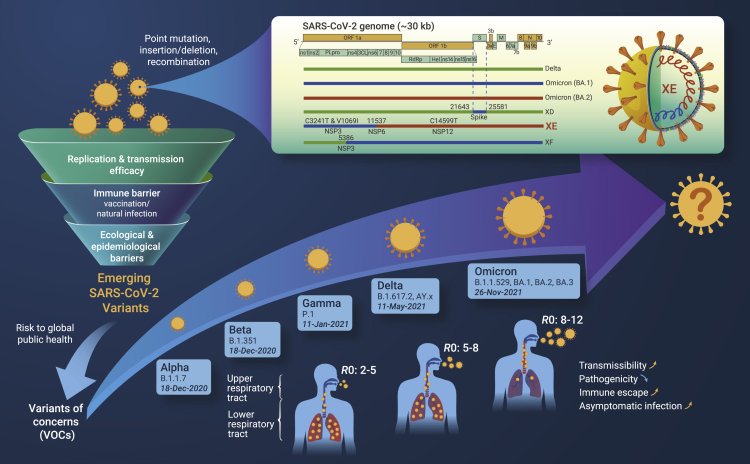

The recombination site of the XE subvariant is located within nonstructural protein (NSP) 6 of the SARS-CoV-2 genome (nucleotide position 11,537),2 and thus the XE contains BA.1 mutations for NSP1–6 and then BA.2 mutations for the remainder of the genome. Moreover, the XE includes three mutations that are not present in all BA.1 or BA.2 sequences (Figure 1), of which NSP3 C3241T and NSP 12 C14599T are synonymous mutations, and the amino acid mutation V1069I is located in NSP3 (papain-like protease), which is responsible for cleaving viral polyproteins during replication. The impact of these mutations on viral transmission, immune evasion, and virulence remains to be investigated.

Figure 1.

Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants of concerns and the newly designated recombinant lineage Omicron XE

Phenotypic changes of viral pathogenicity of Omicron and the emerging XE

Compared with the earlier strains of SARS-CoV-2, the currently circulating Omicron variant harbors a large number of mutations in its spike protein,1 which may help the Omicron to escape neutralizing antibodies from convalescent or vaccinated individuals, and change its capacity in cell entry, replication, and pathogenesis. In general, the efficient transmission of respiratory viruses is associated with the replication in, and shedding from, the upper respiratory tract. In contrast, severe disease is generally mediated by viral replication and tissue destruction in the lower respiratory tract and lung parenchyma. Mutations facilitating replication in the upper airways could be selected because of higher transmissibility and may reduce virulence.3 In line with this, researchers from Hong Kong found that Omicron infects and multiplies 70 times faster than the initial strain of SARS-CoV-2 and the Delta variant in human bronchus. In contrast, the infection of Omicron in the lung is significantly lower (>10 times) than the initial strain of SARS-CoV-2, thus providing explanations for why Omicron transmits faster between humans, while it results in a lower severity of disease than previous variants. This attenuated pathogenicity of Omicron infections has been confirmed in mice and hamsters and is congruous with the accumulated reports of Omicron variant infection in humans, including data that showed significantly decreased odds of hospitalization and death.4 There are also reports indicating that Omicron BA.2 causes a similar risk of hospitalization as the original Omicron strain and BA.1. Studies regarding the long-term immunity of Omicron and the post-COVID condition are ongoing.

It should be noted that the lower severity of Omicron infections seems to be the result of a combination of Omicron’s intrinsically lower virulence and pre-existing immunity, both from vaccination and past infection.4 Considerable variation in the severity of Omicron has been reported in different groups. Those with advanced age, underlying conditions, or who are unvaccinated, can develop a severe form of COVID-19 with Omicron infection. Furthermore, while studies suggest that the authorized vaccines against Omicron generally remain effective at preventing severe disease and death, large reductions in vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization in breakthrough cases were seen for those who had not received a booster dose.4 As for the XE subvariant, however, more evidence should be collected before conclusions can be drawn regarding its severity and vaccine effectiveness. In addition, with the lifting of COVID restrictions in many countries, an increased circulation of SARS-CoV-2 and previously suppressed seasonal respiratory viruses can be expected. As Omicron is highly transmissible, it will significantly burden the health systems as well as other essential services, which may subsequently lead to more deaths. Another risk that should be considered is that of co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens, such as influenza virus, especially in older individuals.

Evolutionary trajectory of SARS-CoV-2

All viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, change over time. Most changes have little or negative impact on the virus’ fitness. Only changes in specific genomic regions of the viruses may allow for their adaptations to a range of host genetic, immunological, ecological, and epidemiological barriers.3 As of March 2022, the WHO has designated five VOCs—Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron—each of which has been demonstrated to be associated with one or more of the following changes at a degree of global public health significance: increased transmissibility or virulence, or decreased in effectiveness of public health and social measures or available diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics. The rapid emergence of variants has provided clues for understanding what evolutionary trajectory the virus follows and how it would determine the future path of the pandemic.

The SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh identified human coronavirus (HCoV) from the Coronaviridae family, and the fourth HCoV belonging to the Betacoronavirus genus. Compared with the HCoVs that cause the common cold, including HCoV-NL63, -229E, -OC43, and -KU1, SARS-CoV-2 has a higher mortality rate, yet is much less pathogenic than SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Based on the evolutionary analysis for all CoVs so far, it is most likely that a newly emerging CoV would primarily evolve to develop increased infectivity and transmissibility to adapt the propagation in the new host. For example, the early D614G substitution in SARS-CoV-2 significantly increased transmission.5 The mutations in the Alpha, Delta, and Omicron variants have further increased viral transmissibility. As immunity gradually builds up, SARS-CoV-2 variants have been increasingly selected as immune escape variants. Mutations that contribute to immune escape, such as the E484K mutation that was reported in Beta and Gamma variants, have emerged, allowing the variants to increase resistance to neutralizing antibodies that are elicited by natural SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination.3 For the Delta variant, both of increased replication fitness and reduced sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies have contributed to its rapid increase, compared with Alpha and other lineages such as Kappa (B.1.617.1). The latest Omicron variant has a particularly high basic reproduction number (R0) and a greater ability to evade immune response, which replaced Delta very quickly in weeks, whereas its virulence has significantly decreased. This evolutionary scenario is to some extent similar to what we see with the 1918 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus, which was highly pathogenic when first infected human in 1918; however, the virus kept evolving and became the seasonal H1N1 virus, which only caused mild illness. As its virulence decreased, this virus kept circulating for more than 40 years, until replacement by a novel H2N2 pandemic virus in 1957. Likewise, studies of the endemic HCoV-229E have found evidence for constant antigenic evolution, which facilitates repeated reinfections and favors the persistence of the virus in human populations.

The co-circulation of Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 have provided great opportunities to generate new recombinant viruses. It remains uncertain whether those emerging recombinants would follow an evolutionary path to become more contagious and less severe. The public health risk associated with XE remains to be assessed at the global level, alongside other emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Notably, a great risk posed by BA.2 is the existence of a large proportion of asymptomatic infection and transmission, making surveillance and control challenging, which may also apply for the XE subvariant.

Response and preparedness measures

To prepare for the newly emerging XE and other variants, we need to actively monitor for potentially increased transmissibility, mortality, and resistance to either vaccine-induced immunity or antiviral therapeutics. Notably, coronaviruses are a group of viruses that regularly jump species boundaries.1 Recent studies have highlighted a potentially broad host tropism of SARS-CoV-2. The evolution of coronaviruses can be driven by a variety of mechanisms, including point mutation, insertion/deletion, and recombination. Thus, the origin of the emerging variants and the potential impacts of intra- and interspecies interaction are worthy to be explored.

While it is difficult to predict what the next VOC will be, it is necessary to decrease the likelihood of emergence of new variants, particularly those of high virulence. To achieve this, continuously strengthening the immune barrier and decreasing the possibility of infection and reinfection are essential. Although it has been clear that less viral replication occurs in vaccinated people as a whole group, which would strongly restrict the evolutionary and immune escape pathways accessible to SARS-CoV-2, unequal global vaccine coverage has long been a problem. Therefore, greater efforts should be made to boost vaccination rate, especially in high-risk groups. Meanwhile, public health intervention strategies, such as mask wearing, hygiene, and physical distancing, are still of great importance.5 Moreover, the development of vaccines and antiviral drugs with improved efficacy and broader coverage is warranted by the pandemic threat from the emerging variants.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published Online: April 18, 2022

References

- 1.Du P., Gao G.F., Wang Q. The mysterious origins of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2. Innovation. 2022;3:100206. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2022.100206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UKHSA . 2022. SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern and Variants under Investigation in England. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Telenti A., Arvin A., Corey L., et al. After the pandemic: perspectives on the future trajectory of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;596:495–504. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03792-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyberg T., Ferguson N.M., Nash S.G., et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399:1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00462-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koelle K., Martin M.A., Antia R., et al. The changing epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2022;375:1116–1121. doi: 10.1126/science.abm4915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]