Abstract

Rationale and objective:

Greater understanding of the challenges to shared decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD is needed to support implementation of shared decision-making in clinical practice.

Study design:

Qualitative study.

Setting and participants:

Patients aged ≥65 years with advanced CKD and their clinicians recruited from 3 medical centers participated in semi-structured interviews. In-depth review of patients’ electronic medical records was also performed.

Analytical approach:

Interview transcripts and medical record notes were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results:

Twenty-nine patients (age 73±6 years, 66% male, 59% Caucasian) and 10 of their clinicians (age 52±12 years, 30% male, 70% Caucasian) participated in interviews. Four themes emerged from qualitative analysis: 1) Competing priorities – patients and their clinicians tended to differ on when to prioritize CKD and dialysis planning above other personal or medical problems; 2) Focusing on present or future –patients were more focused on living well now while clinicians were more focused on preparing for dialysis and future adverse events; 3) Standardized versus individualized approach to CKD – although clinicians tried to personalize care recommendations to their patients, patients perceived their clinicians as taking a monolithic approach to CKD that was predicated on clinical practice guidelines and medical literature rather than patients’ lived experiences with CKD and personal values and goals; and 4) Power dynamics – while patients described cautiously navigating a power differential in their therapeutic relationship with their clinicians, clinicians seemed less attuned to these power dynamics.

Limitations:

Thematic saturation was based on patient interviews. Themes presented might incompletely reflect clinicians’ perspectives.

Conclusions:

Efforts to improve shared decision-making for treatment of advanced CKD will likely need to explicitly address differences in approaches to decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD between patients and their clinicians and perceived power imbalances in the therapeutic relationship.

Keywords: shared decision-making, patient-centered care, medical decision-making, qualitative research

Plain-Language Summary:

While shared decision-making is widely promoted, its implementation in decisions about treatment of advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) remains challenging. We conducted a qualitative study using interviews with older patients with advanced CKD and their clinicians along with medical record review to ascertain perceived challenges with decision-making about treatment of their kidney disease. Patients and their clinicians reported that it was difficult to find common ground in four areas: 1) balancing CKD among other priorities; 2) focusing on the present versus preparing for the future; 3) taking a standardized versus an individualized approach to treatment of advanced CKD; and 4) navigating power differentials in the therapeutic relationship. Steps to promote shared decision-making for treatment of advanced CKD should explicitly address these challenges.

Introduction

Patients with progressive chronic kidney disease (CKD) and their clinicians face difficult decisions about whether and when to pursue maintenance dialysis.1–7 These decisions are particularly challenging for older patients with significant comorbidity for whom there is growing evidence of clinical equipoise between dialysis and conservative management of advanced CKD.8–21

In this context, professional societies call for application of shared decision-making for treatment of advanced CKD.22,23 Shared decision-making emerges from a partnership between the patient and clinician where the patient serves as an expert on their individual circumstances, needs, healthcare values and goals; and the clinician as an expert on the illness and its prognosis as well as evidence-based therapies and their risks, benefits and likely outcomes.24,25

There is concerning evidence that patients and clinicians do not always work collaboratively to reach decisions about treatment of advanced CKD.26 In a survey study of patients with advanced CKD, only 25% perceived that they shared decision-making with their medical team.27 Many patients on dialysis report regret with their decision11 and are unaware of more conservative treatment options for their advanced CKD, such as hospice.28 In prior qualitative studies, many patients described having been presented with little choice but to start dialysis.28,29 Interviews conducted of clinicians indicate that many are uncomfortable with sharing prognostic information and selectively withhold or discourage the option of conservative management with their patients.26,30–33 However, an important limitation shared by most prior qualitative studies is that they reported on only the perspective of patients and not their clinicians, or vice versa, and thus provide an incomplete view of the multifaceted process of decision-making that occurs between patients and their clinicians.

To gain a deeper understanding of how shared decision-making in advanced CKD can be supported in clinical practice, we conducted a qualitative study on the experiences of patients and their clinicians with decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD.

Methods

Study population

We recruited English-speaking patients aged ≥65 years with advanced CKD from nephrology clinics at 3 academic medical centers in the greater Seattle area between March 2017 and April 2018. Advanced CKD was defined as having at least 2 outpatient measures of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≤20 ml/min/1.73m2 separated by >90 days during the previous year. We purposively sampled patients reflecting a range of ages, racial backgrounds, and male and female perspectives. We also reviewed the clinical progress notes entered into the electronic medical record proximal to the study period to further select and invite to participate a sample of patients reflecting a range of documented preferences towards treatment options for advanced CKD. We initially approached patients by letter followed by telephone and invited them to an in-person visit to explain the study. We included patients who might have previously received hemodialysis for acute kidney injury, but excluded those who had received a kidney transplant, were receiving maintenance dialysis or were under the care of any of the authors. We also administered the 6-item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-CIT) screening tool34 to patients and excluded those with cognitive impairment (i.e., score >7). We obtained written informed consent from patients and offered $40 as compensation for time spent participating.

Enrolled patients were invited but not required to identify any clinicians at their medical center who played an influential role in their decision-making about treatment of their advanced CKD and whom we could approach to participate in the study. Recruitment of patient-identified clinicians occurred between July 2017 and May 2018 and was conducted over email or telephone. We first approached clinicians by informing them that one of their patients had identified them as eligible to participate in the study and only disclosed the patient’s identity after clinicians provided their written or electronically signed consent to participate.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at University of Washington (#00000779) and Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System (#00999).

Study setting

The medical centers from which participants were recruited support a range of treatment options for advanced CKD, including in-hospital, in-center and home dialysis therapy, kidney transplant and kidney palliative care. Patients are typically referred to free education classes on their treatment options offered at each medical center or in the community at a non-profit dialysis organization.

Participant characteristics

Patients and clinicians were asked to provide information on their age, race and sex. Clinicians were also asked about their professional training including highest degree attained, years since completion of their terminal degree and clinical specialty. From patients’ medical records, we ascertained whether patients were listed for kidney transplant, had previously received dialysis for acute kidney injury and had completed preparatory steps to place vascular dialysis access.

Qualitative interviews

Patients completed a 60-minute private interview by phone or in-person in a clinic room with either S.P.Y.W. (nephrologist with advanced qualitative methods training) or a research coordinator trained in qualitative research methods. Clinicians completed a private phone or in-person 30-minute interview at their workplace with a research coordinator. For clinicians (n=2) who had more than one patient participating in this study, a separate interview was completed for each of their patients. Patient interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide (Item S1) designed to elicit participants’ experiences and perspectives on decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD. Clinician interviews followed a similar guide (Item S2), and clinicians were encouraged to respond to questions with their enrolled patient’s specific case in mind. Two authors (S.P.Y.W and G.S.) developed the interview guides, which they iteratively refined after review of the first 4 interviews to enhance depth and relevance of responses. All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and purged of personal identifiers. Transcripts were not returned to participants prior to analysis for their edits.

Medical record review

One author (S.P.Y.W.) reviewed all clinical progress notes in each patient’s electronic medical record from 2-years prior to enrollment through to the interview date. Passages containing information pertaining to decision-making about patients’ advanced CKD were abstracted from the medical record and purged of personal identifying information.31

Analytical approach

To analyze interview transcripts and medical record passages, we used inductive thematic analysis,35 which is an approach to uncovering previously unidentified concepts pertaining to a phenomenon through immersive and systematic review and coding of the data. First, S.P.Y.W. and a research coordinator trained in qualitative methods independently reviewed each transcript and openly coded in a line-by-line fashion for emergent themes related to participants’ experiences with making decisions about treatment of their advanced CKD. Coders met at regular intervals to review transcripts, passages and codes, and utilized a consensus-based approach to determine whether thematic saturation (i.e., when no new themes emerged with recruitment of additional cases)36 was reached. Because not all patients had clinicians who participated in this study and because there was substantial heterogeneity in documentation across patients’ medical records, thematic saturation was based on patient interviews. Passages from each patient’s medical record were reviewed and coded in a similar fashion by S.P.Y.W and T.R.H. (pediatric nephrology fellow with qualitative methods training).

Second, patient transcripts were re-reviewed alongside their corresponding clinician transcript and/or medical record passages by S.P.Y.W. and T.R.H. using a constant comparative approach, which is a process of comparing elements of a phenomenon when it occurs under different conditions.35 We recorded analytical and theoretical memos of similar, related and overlapping themes that emerged from these different data sources. Themes selected for the final thematic schema comprised those reflecting processes shaping decisions about treatment of advanced CKD shared by both patients and their clinicians. All authors participated in theme refinement and assembly into larger thematic categories. Member-checking (i.e. sharing analyzed data with participants for their input)37 was not performed out of concern that disclosing preliminary themes that synthesized patient and clinician data and their supporting quotations might threaten participant confidentiality and undermine therapeutic relationships. We used Atlas.ti v.8 to annotate transcripts and passages and organize codes and memos. The genders of patients and clinicians referenced in quotations were changed at random to conceal participants’ identities.

Results

We approached 66 patients of whom 3 screened positive for cognitive impairment, and 29 (age 73±6 years, 66% male, 59% Caucasian) consented to participate (Table 1). Examples of patients’ documented treatment preferences are provided (Table S1). All 29 enrolled patients identified at least 1 clinician (2 patients named the same clinician) who was influential in their decision-making about treatment of their advanced CKD and whom we could approach for interviews. We approached 25 clinicians of which 10 (age 52±12 years, 30% male, 70% Caucasian) consented to participate (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| N=29 |

|

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 73 (6) |

| Race | |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 2 |

| Black, African American | 6 |

| Hispanic, Latino | 3 |

| White, Caucasian | 17 |

| Mixed race | 1 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 10 |

| Male | 19 |

| Dialysis fistula placed | 2 |

| Previously received acute dialysis | 2 |

| Listed for transplant | 3 |

Table 2.

Clinician characteristics

| N=10 |

|

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 52 (12) |

| Race | |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 3 |

| Black, African American | 0 |

| Hispanic, Latino | 0 |

| White, Caucasian | 7 |

| Mixed race | 0 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 7 |

| Male | 3 |

| Years of clinical practice, mean (SD) | 17 (9) |

| Medical specialty | |

| Nephrology | 6 |

| Oncology | 1 |

| Social Work | 1 |

| Vascular surgery | 1 |

| Primary Care | 1 |

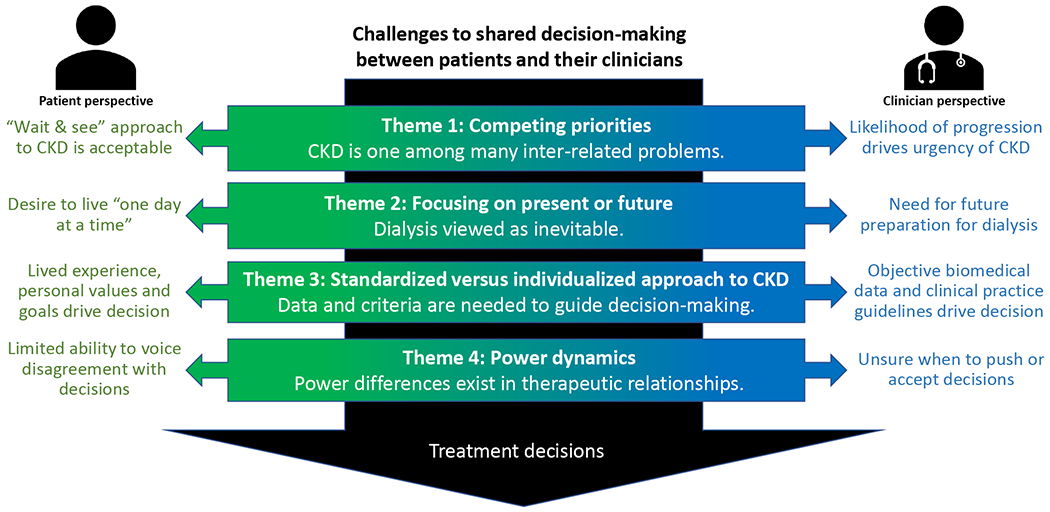

Four major themes emerged from interview transcripts and medical record passages reflecting shared processes for patients and their clinicians in decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD: 1) competing priorities; 2) focusing on present or future; 3) standardized versus individualized approach to CKD; and 4) power dynamics. Illustrative quotations supporting each theme are presented in Boxes 1–4.

Competing priorities

Both patients and clinicians described challenges with balancing multiple competing priorities in addition to advanced CKD (Box 1). Patients voiced needing to attend to several other medical conditions (quote 1a) and complex personal circumstances (quote 1b) concurrently and spoke of CKD as “just another worry” among many (quote 1c). Clinicians also acknowledged that as patients’ personal stressors and medical complications increased (quote 1d), consideration of other issues necessarily took precedence over patients’ CKD (quote 1e). Nevertheless, patients and clinicians did not always agree on the urgency and attention that their CKD should be given over other priorities in patients’ lives (quote 1f). Some patients expressed that they were best able to handle each issue if they addressed “one thing at a time” (quote 1g). Patients tended to take a “wait and see” approach with their CKD and relied on changes in clinical status to prompt them to refocus their efforts towards their CKD and preparation for dialysis or transplant (quote 1h).

By contrast, clinicians tended to use likelihood of disease progression to guide whether they might “push” the issue of CKD with their patients in advance of clinical deterioration (quote 1i). In other instances, the pace of decision-making for CKD was tied to decisions and outcomes of other illnesses (quote 1j). Despite the complex interplay that these decisions could have, they were often dealt with separately by different clinicians in different clinical settings (quote 1k). Such fragmentation in decision-making could sometimes hinder or precipitate a cascading series of decisions about interventions to ultimately address patients’ CKD (quote 1l).

Focusing on present or future

Across interviews and chart notes, patients and clinicians expressed different outlooks on CKD, with patients taking a more present-oriented and clinicians a more future-oriented view of CKD (Box 2). Patients described how “dialysis or death” were presented as a “foregone conclusion” (quote 2a), with some stating only “a miracle” could provide an alternative outcome. In this regard, patients saw “dwelling” on the future as “negative” (quote 2b) and steps to prepare for this future as only guaranteeing dialysis or death to occur (quote 2c). For one patient who did take advance steps to prepare for kidney failure but whose CKD did not progress, his efforts seemed unnecessarily burdensome in hindsight (quote 2d). Patients generally expressed desire to live in the “present” without thinking “way into the future,” enjoying a “normal life” now and taking “one day at a time” (quote 2e).

Except for one clinician who intentionally coached a patient to shift her attention to the “immediacy of the day” as a means to cope with CKD (quote 2f), clinicians tended to “strongly recommend” early preparation for declining health and dialysis (quote 2g). Clinicians described feeling an “obligation” to caution patients about the risk of kidney failure and dialysis while not “coming off as seeming really pessimistic” (quote 2h). Clinicians tended to interpret patients’ reluctance to consider the future or plan for dialysis as “not being realistic” or indicating “a lack of understanding” or “fear” (quote 2i).

Standardized versus individualized approach to CKD

Patients perceived their clinicians as taking a largely rote approach to management of their CKD that seemed to override their individual concerns (Box 3). Patients described a seemingly preeminent role that blood work and laboratory measures had in characterizing their CKD (quote 3a) and decision-making about whether and when to start dialysis (quote 3b). To patients, the weight assigned to laboratory values by clinicians’ in their assessments and treatment recommendations seemed arbitrary and incongruent with how they felt and what symptoms they were experiencing (quote 3c). Patients also perceived clinicians as overly focused on “the disease that they walked in the room for” and that interactions often consisted of a series of closed-ended questions posed by clinicians intended to assess whether patients fit a “textbook” presentation of CKD (quote 3d). Patients remarked that their clinicians didn’t “trust people to know their own bodies better than they do.” Patients found it difficult for clinicians to set aside their preconceived notions and accept an alternative perspective of their CKD and how best to manage it (quote 3e).

In contrast to the monolithic approach to CKD perceived by patients, clinicians who participated in interviews described varying approaches to caring for their patients. Some clinicians tended to adhere to the “standard of care” and favor “going with the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines” (quote 3f). Others discussed being careful not to “extrapolate population statistics” to one patient and to “treat them as an individual” (quote 3g). Clinicians also tended to consider their patients’ personal circumstances and comorbid conditions when determining eligibility for different dialysis modalities and kidney transplant (quote 3h). While these clinicians felt that they were more confident from the “scientific perspective” about appropriateness of treatments in individual cases, they did not feel they had adequate time or skill to talk with patients about their goals of care and which treatments best supported these goals (quote 3i). Consistent with this, we could not find documentation in clinical notes of patients’ healthcare goals elicited by their clinicians. Further, when directly asked by interviewers, none of the patients remembered being presented with a conservative option for their advanced CKD.

Power dynamics

Patients perceived themselves at disadvantage relative to their clinicians in their ability to make decisions about treatment of advanced CKD (Box 4). With little to no medical background, patients described having “no choice” but to “trust” their clinicians and accept their proposed plans and recommendations about whether and when to start dialysis (quote 4a). While patients generally accepted clinicians’ assessments of their CKD and care recommendations, some patients also described doubts and/or disagreements about their CKD and treatments (quote 4b). How patients handled these differences with their clinicians varied. Some patients voiced their differences directly with their clinicians, which clinicians sometimes found to be confrontational (quote 4c). Other patients were more deferential, using humor or exploratory questioning to convey that their clinicians’ assessments and recommendations “didn’t sit well” with them (quote 4d). There were also some patients who kept these differences in beliefs hidden out of concern of disapproval from their clinicians (quote 4e).

Clinicians seemed less attuned to the power differential described by patients. Although clinicians acknowledged their influence over their patients’ decision-making, they also felt it had its limits and saw that their patients could ultimately decide which treatments to accept (quote 4f). Interview responses (quote 4g) and documentation in the medical record (quote 4h) also suggested that some clinicians were unsure where to draw the line between “encouraging” and “forcing” patients into accepting recommendations when patients seemed reluctant. Only one clinician whom we interviewed discussed intentionally approaching patients as a peer to cultivate open, honest conversations about kidney disease and dialysis (quote 4i).

Discussion

Our study spotlights 4 key areas where it can be remarkably challenging for patients and their clinicians to find common ground in decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD (Figure 1). Patients and their clinicians described differing perspectives on balancing attention to CKD and dialysis planning versus multiple other priorities, focusing on the present versus planning for the future, relying on biomedical data and clinical practice guidelines versus patients’ informed preferences to make treatment decisions, and recognizing and navigating power differences within the patient-clinician therapeutic relationship.

Figure 1: Four challenges to decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD experienced by patients and their clinicians.

Theme 1: Competing priorities – When to triage CKD and dialysis planning above other priorities; Theme 2: Focusing on present or future – How to face dialysis as an inevitability; Theme 3: Standardized versus individualized approach to CKD – What information is overriding in guiding decision-making; Theme 4: Power dynamics – How power differences affect the patient-clinician therapeutic relationship.

Shared decision-making reflects a paradigm shift in nephrology from a traditional disease-based framework towards a more patient-centered approach to caring for patients with advanced CKD.24 Under a disease-based model, care is predominantly informed by an understanding of underlying biological mechanisms and epidemiology of illness and is focused on halting disease progression and minimizing risk of complications. Clinicians are the preeminent expert in care. In contrast, under a patient-centered model, care is designed to serve the specific needs, values and preferences of patients and accommodates the agency that patients would like to have in their care and decision-making. Our findings illustrate major flashpoints in decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD that can occur at the intersection of these two models of care. Our findings resonate with those of other studies that have reported on the lack of explicit education in techniques to promote shared decision-making in nephrology curricula,38,39 and the emotional and moral distress experienced by patients and their clinicians when reconciliation of patients’ wishes with clinicians’ perceived best interests or traditional standards of care is not achieved.30,32,40 Conversely, when clinicians receive training in communication techniques to facilitate elicitation of patients’ values, goals and preferences, patients more often report having talked with their clinicians about their goals of care and perceive their care as concordant with their goals.41 Patient decision aids can also better prepare patients to select a treatment option that they believe is best for them.42 Additionally, engaging specialty palliative care and ethics consultation services in the care of complex patients can be helpful to patients, families and clinicians and reduce the use of burdensome or unnecessary treatments.43,44 Taken together, our findings call for more innovation to support shared decision-making for treatment of advanced CKD.

Whereas most prior studies on clinician perspectives of decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD have been limited to nephrologists,29 our findings highlight the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration and a whole-person approach to decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD. In fact, 40% of the clinicians who participated in our study because their patients identified them as influential in their decision-making were non-nephrologists, and we found documentation related to dialysis decision-making in many of the clinical progress notes of non-nephrologists. When making decisions, some patients may preferentially engage clinicians outside of nephrology with whom they have long-standing relationships.11,45,46 Further, we found that patients and their clinicians alike viewed CKD as an important consideration among multiple inter-related problems, but decision-making about each problem often seemed siloed. Implementation of a multispecialty team approach may help to clarify patients’ competing priorities, overcome care fragmentation and improve patient outcomes for those with advanced CKD 47,48

This study has several limitations. First, although we utilized purposive sampling to gather diverse patient perspectives on decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD, our findings may be of limited generalizability. Patients and clinicians were recruited from academic medical centers located in a single geographic area, and their experiences may not be representative of those in other practice settings and regions. Participants might not be representative of those who elected not to participate or might reflect a biased sample of patient-clinician dyads who wished to share particularly memorable (positive or negative) experiences with decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD. Second, we used documentation in patients’ medical records as a window on clinical encounters between patients and their clinicians as they unfolded, enabling study of a range of clinician types and settings that are relevant to decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD. This technique has advantages over direct observation of clinical encounters, which can influence patient and clinician behaviors and be unreliable because it is not guaranteed that treatment of advanced CKD will be discussed during any given observed encounter.49 However, documentation is also limited by what clinicians chose to document and may not accurately or completely reflect patient-clinician interactions. Third, we cannot be certain that patients and clinicians were referring to the same encounters during interviews or to distant encounters that would be subject to recall bias, both of which might contribute to the observed differences in perspectives between patients and clinicians. Fourth, we did not solicit the perspectives of caregivers who are also commonly involved in decision-making about CKD.11 Fifth, our study examines the perspectives of patients and clinicians gathered at a single point in time. Future work is needed to examine how perspectives might change over time. Finally, although themes presented emerged from patient and clinician interviews and the medical record, thematic saturation was based on patient interviews. Subsequently, our findings are not exhaustive of themes relating to clinicians’ perspectives on decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD.

This qualitative study provides insight into some of the obstacles encountered by patients and their clinicians during decision-making about treatment of advanced CKD. Our findings suggest that success to achieving shared decision-making for treatment of advanced CKD will likely require stronger methods for integrating more holistic and patient-centered approaches to caring for patients with advanced CKD.

Supplementary Material

Item S1 – Patient Interview Guide

Item S2 – Provider Interview Guide

Table S1 – Documented patient preferences toward treatment options for advanced CKD

Box 1.

Theme 1: Competing priorities

| Quote* | Quotation [source] | Participant |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | I have to manage diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and being old, balance, falling, fear of falling. I mean, there are so many things going on. [patient interview] | 13 |

| 1b | How the hell is a person supposed to live a life when they are living on the streets or living with drugs and stuff in their lives? [patient interview] | 8 |

| 1c | It’s everything…If I just had the kidney problem, I could cope with that, you know, easily…But it’s everything together. That’s the problem. The kidney disease is just another worry. [patient interview] | 15 |

| 1d | Her kidney disease was not very far along. Her cancer needed better follow up, so I remember spending initial time with her trying to arrange better follow up with urology and imaging…we didn’t talk early in our relationship necessarily about dialysis and things like that. [clinician interview] | 7 |

| 1e | She stated interest in dialysis, she just doesn’t want to work on that right now, and I haven’t pushed it…Depression and dissatisfaction in her living situation and family relationships. So that really predominates with her. [clinician interview] | 29 |

| 1f | So now my kidney function is down to, I think, [my creatinine is] 2.5…Their biggest concern is they take me off my diuretic…but what happens is my legs swell up…I can’t move them…Take me off my diuretics, it hurts too much to walk…In my mind, I’d rather at least have some kind of quality of life than just sitting around doing nothing. [patient interview] | 33 |

| 1g | Right now, I’m dealing with a foot problem…I can only do one thing at a time. Let’s hope I get through that. [patient interview] | 39 |

| 1h | When I slowly discovered that maybe it wasn’t going to happen that fast, I somewhat lost interest in all of that. It didn’t seem like something that I needed to pay attention to and so I focused more on simply trying to maintain the level of function with what I’ve been doing. [patient interview] | 9 |

| 1i | For someone like the patient whose blood pressure, diabetes were out of control, they’re going to progress pretty fast. That’s why I really tried to push for getting her to [dialysis class] and learn about dialysis. [clinician interview] | 1 |

| 1j | She has a second issue which is she has a pararenal abdominal aortic aneurysm…We’ve concluded that the risks of attempted repair probably outweigh the benefit…Any attempt to treat her aneurysm is likely to make her kidney disease progress…In general, being on dialysis leads to a significant decrease in quality of life. [clinician interview] | 40 |

| 1k | The surgeons have told her that they don’t think she’s a good surgical candidate partially because of her kidney disease…One of the doctors set her up to see one of his colleagues at the university…And she did see another one of the providers here who is considering her for a less invasive repair…But nobody was really following through with that…[the patient] was not getting answers that she wanted, she felt she should get surgery. [clinician interview] | 28 |

| 1l | She would need a chest/abdomen/pelvis computed tomography with angiogram in order to make a final determination. The patient is approaching the need for hemodialysis…I discussed with her that the intravenous contrast might precipitate hemodialysis…She is leaning toward imaging. [medical record] | RR |

the number indicates the theme to which the quotation pertains; the letter indicates the order in which the quotation is referenced in the manuscript text

Box 2.

Theme 2: Focusing on present or future

| Quote | Quotation [source] | Participant |

|---|---|---|

| 2a | There’s no cure for kidney disease. You just live until you get real sick and then you get into dialysis. If not, you just got to die. That’s all. [patient interview] | 12 |

| 2b | I don’t have any feelings about death at this point. I’m not even thinking about it. I’m just thinking about every day and waking up and having a good day. I don’t really bother to think way into the future…My parents, gave me the idea that you accept your situation and not dwell on the negative. [patient interview] | 26 |

| 2c | It’s hard to explain. I actually tell my body to heal itself. It’s one of the things I was taught: positive thinking. If you have a negative attitude, if you start saying, “I’m dying” or “my kidneys are failing,” they will! [patient interview] | 37 |

| 2d | “You’ve got to have a caregiver, now!”…I just busted my butt trying to find her…“You’ve got to change this diet!“…The diet has been hell…They wanted me to find someone to donate a kidney…“Find yourself a kidney!”….[My doctors] never let up…I was supposed to rush forward and show them I could do everything they wanted. But they were just thinking about it, my life was trickling by, my time here on earth is going away, and if I don’t get a kidney or if I need one. [patient interview] | 5 |

| 2e | Just every day, take one day at a time. I’m glad to be here. Tomorrow is not promised. [patient interview] | 17 |

| 2f | She is beginning to see the value of slowing down and trying to pay more attention to what is happening now, not so much focused on the future where she feels more limited. [medical record] | R |

| 2g | Her renal function continues to decline. At such a rate, she would likely progress to end-stage renal disease in the next 12 months. Patient states she was told she needs dialysis many years ago, but “nothing ever happens…” I discussed the need to prepare for vascular access early…Despite extensive counseling, patient declines referral to vascular surgery. [medical record] | O |

| 2h | I struggled a lot about how to say this, you know, that “when your kidneys are no longer working, you can’t live…” our conversations over the last six months have been quite serious and I leave the visit feeling, you know, “have I done enough? Have I explained it clearly enough?“ [clinician interview] | 6 |

| 2i | I’m very mindful of how fear modifies their response. I’ve never met a patient when, if I tell them, “You need dialysis,” says, “Hey, start me on dialysis.” Never met a patient. Even if a patient may not articulate fear, they’re afraid. [clinician interview] | 22 |

Box 3.

Theme 3: Standardized versus individualized approach to CKD

| Quote | Quotation [source] | Participant |

|---|---|---|

| 3a | There are no symptoms, per se. They check my blood. The tale is told in the blood. That’s why they take the blood every time I go see them. They can tell if I’ve got certain things going on. [patient interview] | 30 |

| 3b | I think my numbers are going to make my decisions actually. If I get down below 13 much, she wants to start doing [dialysis]. [patient interview] | 35 |

| 3c | You’re down to 10%, you’ll get the dialysis. So, how do they set up the 10%?…Right now I’m about 15. I feel okay…But if to the point, I said, “I feel so sick, why do you say it’s not yet?” [patient interview] | 34 |

| 3d | Everything is quicker in meetings with the nurses or the doctors…it’s more black-and-white--”Here is what you do. Here’s the thing that you’ve got to do. Here’s how you have to go on these…“ They’re more interested in physical feelings. Am I tired? Am I whatever? They’re looking at it from a medical point of view…It’s all statistics and results and things like that. When they talk to patients, they’re using that type of information. That’s all fine and dandy, but life isn’t just cut and dry. There’s a little more to it. I don’t get the impression that it’s something they really want to hear. [patient interview] | 19 |

| 3e | Empty your teacup and you’ll be able to learn. If you want to taste my tea, and you have a teacup full of your tea, you’re not going to taste my tea. If you want to taste my tea, empty your teacup, let me pour some in. But if you mix it with yours, you’re not going to taste it, you’re going to say it tastes bad…“Loosen up, empty your mind and listen to me, then think about it,” that’s what I like to say to doctors. [patient interview] | 13 |

| 3f | We recommend the standard of care and I show them the guidelines, if they want to see them. [clinician interview] | 20 |

| 3g | It is my goal to provide them with all the information that I can. For me then, to understand what is important to them, based on that information, and then help them navigate this very difficult journey. [clinician interview] | 22 |

| 3h | She is interested in peritoneal dialysis and would like to learn more about peritoneal dialysis. However, given multiple abdominal surgeries, may not be a candidate. [medical record] | L |

| 3i | We’re working with patients and scrutinizing them closely for the development of uremic symptoms…But then also talk about goals of care, I would say, almost impossible within a 25-minute visit…It’s not something that I would say is in my wheelhouse of strengths, working on advance care planning. [clinician interview] | 2 |

Box 4.

Theme 4: Power dynamics

| Quote | Quotation [source] | Participant |

|---|---|---|

| 4a | A doctor has a plan and I think, as a patient, yon kind of just give into that because they’re supposed to be educated enough above you to know why they came up with that plan and you have to just trust that the doctor is correct when she may or may not be. [patient interview] | 19 |

| 4b | Everybody talks about like that’s the absolute, you’re going to be on dialysis. Why am I hearing that all the time? It’s like you’re trying to talk me into it…“What do you think about dialysis? How are you going to…“I don’t want to do dialysis. [patient interview] | 39 |

| 4c | They tell me, “You’re getting worse and worse…“ I argue with my kidney doctor, I say, “Well I don’t feel sick. I feel the same…“ They just say, “Why are you arguing with me all the time?” [patient interview] | 12 |

| 4d | As a physician, the patient may not agree with you all the time…if you don’t agree, then you may challenge it, “Why is this?”…I guess, when I ask questions, my tone is a question and not a challenge, that’s very important. [patient interview] | 34 |

| 4e | I’m going to admit something now…I said, “I’m taking these herbs, “and [my nephrologist] says, “I don’t know what’s in them, but I don’t want you to take them.” Well, I’ve been taking them, constantly, for two years now, and I’m not willing to stop. [patient interview] | 9 |

| 4f | “[Patient} claims she just can’t do it…I feel like every time I see her, I just have to say, ‘Listen, you have to. You can do this. You can take care of yourself. You just have to do it.’ Monitoring her blood pressure, watching her diet, taking her medications. But she’s just very sort of fatalistic.” [clinician interview] | 29 |

| 4g | [Patient] actually left the visit early because she was not happy with what I was telling her. She didn’t want to talk about [dialysis]. She absolutely did not want to go there at all. This is something that is going to happen to her in her lifetime…That’s why I really tried to push for getting her to the [dialysis education classes] and learn about dialysis…I mean, it’s her choice. As a provider, as long as the patient has capacity to make decisions, I can’t push any of my beliefs onto her…I have no right to impose. I think my role is to educate her about the consequences of her disease, as long as I’ve done that, maybe she doesn’t believe me, I don’t feel strongly to further push my beliefs…if you force care onto patients, when they don’t really want to accept it, in the long term, I don’t think it’s a good idea. [clinician interview] | 1 |

| 4h | We discussed that reducing [medication] is unlikely to precipitate chest pain and encouraged her to hold or lower this dose…Unable to convince [patient] to reduce [medication] as recommended. [medical record] | H |

| 4i | I just talk to people like they’re my fiend or they’re just a normal person…I always try to get to know someone…I try to find some common ground as I’m doing the history…I try to find something that I share with someone. I try to figure out more what’s special about them and try to bring that out…I don’t actually talk about dialysis at the beginning because I want to have a relationship with someone before that even happens. [clinician interview] | 33 |

Acknowledgements:

We thank the patients and clinicians who participated in this study for their contributions. We also thank Julie Chotivatanapong for her assistance with conducting background literature reviews.

Support:

This work was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health (1K23DK107799-01 A1, PI Wong). Dr. House is supported by a National Institutes of Health training grant (5T32DK007662-30, PI Hingorani). The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Financial Disclosure:

Dr. Wong receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Palliative Care Research Center and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Dr. Rosenberg has received funding for unrelated work from the National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, Arthur Vining Davis Foundations, Cambia Health Solutions, Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO, CureSearch for Children’s Cancer, and the Seattle Children’s Research Institute. The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The opinions herein represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders.

Contributor Information

Taylor R. House, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle Children’s Hospital, 4800 Sandpoint Way NE, O.C. 9.820, Seattle, WA 98105.

Aaron Wightman, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Abby R. Rosenberg, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington.

George Sayre, Department of Health Services, University of Washington, HSR&D Center of Innovation for Veteran-Centered and Value-Driven Care, VA Puget Sound Health Care System.

Khaled Abdel-Kader, Vanderbilt University.

Susan P. Y. Wong, University of Washington, VA Puget Sound Health Care System.

References

- 1.Breckenridge DM. Patients’ perceptions of why, how, and by whom dialysis treatment modality was chosen. ANNA J. 1997;24(3):313–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tweed AE, Ceaser K. Renal replacement therapy choices for pre-dialysis renal patients. Br J Nurs. 2005;14(12):659–664. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2005.14.12.18287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landrennau K, Ward-Smith P. Perceptions of adult patients on hemodialysis concerning choice among renal replacement therapies. Nephrol Nurs J. 2007;34(5):513–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee A, Gudex C, Povlsen JV, Bonnevie B, Nielsen CP. Patients’ views regarding choice of dialysis modality. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(12):3953–3959. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Chadban S, et al. Patients’ experiences and perspectives of living with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(4):689–700. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.10.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harwood L, Clark AM. Understanding pre-dialysis modality decision-making: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):109–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassidy BP, Getchell LE, Harwood L, Hemmett J, Moist LM. Barriers to education and shared decision making in the chronic kidney disease population: A narrative review. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5;2054358118803322. Published 2018. Nov 2. doi: 10.1177/2054358118803322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S, Warwicker P, Greenwood R, Farrington K. Choosing not to dialyse: evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;95(2):c40–c46. doi: 10.1159/000073708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE. Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(7):1955–1962. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A. Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(10):1611–1619. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00510109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195–204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1608–1614. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Da Silva-Gane M, Wellsted D, Greenshields H, Norton S, Chandna SM, Farrington K. Quality of life and survival in patients with advanced kidney failure managed conservatively or by dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(12):2002–2009. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01130112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain JA, Mooney A, Russon L. Comparison of survival analysis and palliative care involvement in patients aged over 70 years choosing conservative management or renal replacement therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease. Palliat Med. 2013;27(9):829–839. doi: 10.1177/0269216313484380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong SPY, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM. Healthcare intensity at initiation of chronic dialysis among older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(1):143–149. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, Foote C, Li Q, Brennan FP. CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: Survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):260–268. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03330414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verbene WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ. Comparative survival among older adults with advanced kidney disease managed conservatively versus with dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(4):633–640. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07510715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ladin L, Lin N, Hahn E, Zhang G, Koch-Weser S, Weiner DE. Engagement in decision-making and patient satisfaction: a qualitative study of older patients’ perceptions of dialysis initiation and modality decisions. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(8):1394–1401. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura MK, Desai M, Kapphahn KI, Thomas I, Asch SM, Chertow GM. Dialysis versus medical management at different ages and levels of kidney function in veterans with advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29(8):2169–2177. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017121273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verberne WR, Dijkers J, Kelder JC, et al. Value-based evaluation of dialysis versus conservative care in older patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: a cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):205. Published 2018. Aug 16. doi: 10.1186/sl2882-018-1004-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wachterman MW, O’Hare AM, Rahman OK, et al. One-Year Mortality After Dialysis Initiation Among Older Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(7):987–990. doi: 10.1001/jamaintemmed.2019.0125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renal Physicians Association Working Group. Shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis: Clinical practice guideline. Renal Physicians Association, 2010. Available at http://www.renalmd.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=2710 Accessed October, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freidin N, O’Hare AM, Wong SPY. Person-centered care for older adults with kidney disease: Core curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74(3):407–416. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu CF, Laundry RJ, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM. Care Practices for Patients With Advanced Kidney Disease Who Forgo Maintenance Dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):305–313. doi: 10.1001/jamaintemmed.2018.6197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orsino A, Cameron JI, Seidl M, Mendelssohn D, Stewart DE. Medical decision-making and information needs in end-stage renal disease patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25(5):324–331. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00069-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ. 2010;340:c112. Published 2010. Jan 19. doi: 10.n36/bmj.cn2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hussain JA, Flemming K, Murtagh FE, Johnson MJ. Patient and health care professional decision-making to commence and withdraw from renal dialysis: A systematic review of qualitative research. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(7):1201–1215. doi: 10.2215/CJN.1109m4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, et al. Discussing conservative management with older patients with CKD: An interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71(5):627–635. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.n.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong SPY, Vig EK, Taylor JS, et al. Timing of Initiation of Maintenance Dialysis: A Qualitative Analysis of the Electronic Medical Records of a National Cohort of Patients from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):228–235. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA. Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(4):495–503. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.n.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA. System-Level Barriers and Facilitators for Foregoing or Withdrawing Dialysis: A Qualitative Study of Nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(5):602–610. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40(9):771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough?. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, Campbell C, Walter F. Member Checking. A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely a Nod to Validation?. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1802–1811. doi: 10.1177/1049732316654870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Combs SA, Culp S, Matlock DD, Kutner JS, Holley JL, Moss AH. Update on end-of-life care training during nephrology fellowship: a cross-sectional national survey of fellows. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(2):233–239. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schell JO, Green JA, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM. Communication skills training for dialysis decision-making and end-of-life care in nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(4):675–680. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05220512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wachterman MW, Leveille T, Keating NL, Simon SR, Waikar SS, Bokhour B. Nephrologists’ emotional burden regarding decision-making about dialysis initiation in older adults: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20(1):385. Published 2019. Oct 24. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1565-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, et al. Effect of a Patient and Clinician Communication Priming Intervention on Patient-Reported Goals-of-Care Discussions Between Patients With Serious Illness and Clinicians: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):930–940. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subramanian L, Zhao J, Zee J, et al. Use of a Decision Aid for Patients Considering Peritoneal Dialysis and In-Center Hemodialysis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74(3):351–360. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(9):1166–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL. Quality of End-of-Life Care Provided to Patients With Different Serious Illnesses. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goff SL, Eneanya ND, Feinberg R, et al. Advance care planning: a qualitative study of dialysis patients and families. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):390–400. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07490714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saeed F, Sardar MA, Davison SN, Murad H, Duberstein PR, Quill TE. Patients’ perspectives on dialysis decision-making and end-of-life care. Clin Nephrol. 2019;91(5):294–300. doi: 10.5414/CN109608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silver SA, Bota SE, McArthur E, et al. Association of Primary Care Involvement with Death or Hospitalizations for Patients Starting Dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(4):521–529. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10890919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta R, Skootsky SA, Kahn KL, et al. A System-Wide Population Health Value Approach to Reduce Hospitalization Among Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: an Observational Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1613–1621. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06272-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marcuse EK. Weighing the evidence: the Hawthorne effect. AAP Grand Rounds, 2009;22(6);72. DOI: 10.1542/gr.22-6-72 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Item S1 – Patient Interview Guide

Item S2 – Provider Interview Guide

Table S1 – Documented patient preferences toward treatment options for advanced CKD