Abstract

Background

Global data show that transgender people (TGP) are disproportionally affected by HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs); however, data are scarce for Western European countries. We assessed gender identities, sexual behaviour, HIV prevalence and STI positivity rates, and compared these outcomes between TGP who reported sex work and those who did not.

Methods

We retrospectively retrieved data from all TGP who were tested at the STI clinics of Amsterdam and The Hague, the Netherlands in 2017–2018. To identify one’s gender identity, a ‘two-step’ methodology was used assessing, first, the assigned gender at birth (assigned male at birth (AMAB)) or assigned female at birth), and second, clients were asked to select one gender identity that currently applies: (1) transgender man/transgender woman, (2) man and woman, (3) neither man nor woman, (4) other and (5) not known yet. HIV prevalence, bacterial STI (chlamydia, gonorrhoea and/or infectious syphilis) positivity rates and sexual behaviour were studied using descriptive statistics.

Results

TGP reported all five categories of gender identities. In total 273 transgender people assigned male at birth (TGP-AMAB) (83.0%) and 56 transgender people assigned female at birth (TGP-AFAB) (17.0%) attended the STI clinics. Of TGP-AMAB, 14,6% (39/267, 95% CI 10.6% to 19.4%) were HIV-positive, including two new diagnoses and bacterial STI positivity was 15.0% (40/267, 95% CI 10.9% to 19.8%). Among TGP-AFAB, bacterial STI positivity was 5.6% (3/54, 95% CI 1.2% to 15.4%) and none were HIV-positive. Sex work in the past 6 months was reported by 53.3% (137/257, 95% CI 47.0% to 59.5%) of TGP-AMAB and 6.1% (3/49, 95% CI 1.3% to 16.9%) of TGP-AFAB. HIV prevalence did not differ between sex workers and non-sex workers.

Conclusion

Of all TGP, the majority were TGP-AMAB of whom more than half engaged in sex work. HIV prevalence and STI positivity rates were substantial among TGP-AMAB and much lower among TGP-AFAB. Studies should be performed to provide insight into whether the larger population of TGP-AMAB and TGP-AFAB are at risk of HIV and STI.

Keywords: transgender persons, HIV, sex work

Introduction

The epidemiology of HIV and bacterial STIs among transgender women (TGWs) (ie, individuals whose sex assigned at birth was male and currently self-identify as female) varies widely across different populations and settings.1 Results have shown that TGW are disproportionately affected by HIV and may be similarly susceptible to other STIs.1 In a meta-analysis, the pooled HIV prevalence in TGW worldwide was estimated at 19.1% (95% CI 17.4 to 20.7).1 Studies on HIV and STI in transgender men (TGMs) (ie, individuals whose sex assigned at birth was female and now identify as male) are scarce and often relatively small.2–4 A study from Australia found an HIV prevalence of 3.5% (14/404) in TGM.5 The same study reported an STI positivity of 15.0% in TGW and 8.4% in TGM.5 Previous studies showed that sex work is prevalent among TGWs due to, among other reasons, the experience of stigmatisation and institutional discrimination and for economic survival.6 7 In addition, sex work contributes to HIV and STI risks. Two studies among TGW sex workers (SWs) in the Netherlands found high HIV prevalence and STI positivity rates of 18.8%–20.0% and 26.0%–26.7%, respectively.8 9 However, these outcomes are not generalisable to the broader TGW population due to selection of subpopulations (ie, SWs). A better understanding of the sexual behaviour of Western European transgender people (TGP) is required to improve healthcare policy and intervention programmes. Moreover, most studies focus only on TGWs and TGMs, omitting other gender identities. However, there is a spectrum of gender identities outside the gender binary conformity, also called gender non-binary.10 High-quality epidemiological data of TGP (including non-binary TGP) are needed to better assess the sexual health needs of this population.11 To address the broader spectrum of gender identities, we primarily use in this article—instead of TGW and TGM—the terms transgender people assigned male at birth (TGP-AMAB) and transgender people assigned female at birth (TGP-AFAB) followed by their current gender identity.

We assessed sexual behaviour, HIV prevalence and STI positivity rates among TGP with various gender identities attending the STI clinics of Amsterdam and The Hague and compared these outcomes between TGP who reported engaging in sex work and those who did not.

Materials and methods

Study sites and population

The Centre for Sexual Health/STI clinic of Amsterdam and the Centre for Sexual Health of The Hague are two of the largest STI outpatient clinics of the Netherlands, performing around 51 000 and 12 000 STI consultations annually (respectively),12 13 which amounts around 41% of the total number of STI consultations performed at all Dutch STI clinics.14 They provide anonymous and free-of-charge STI testing and treatment to key groups including TGP. In this analysis, we used data from TGP who had at least one consultation at one of the clinics, between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2018.

Data collection

Routinely collected data retrieved from the electronic patient files were age, ethnicity (defined according to the Statistics Netherlands on the basis of country of birth and maternal and paternal country of birth15), education, HIV status, gender of sexual partner(s), the number of sex partners and engaging in sex work in the preceding 6 months.

Additionally, we routinely collected the following sexual behaviour characteristics1: giving condomless fellatio (only data from Amsterdam),2 condomless anal sex (CAS); receptive: if reported sex with men; insertive: if currently having a penis) and3 condomless vaginal sex (CVS) (if currently having a vagina and reported sex with men or if currently having a penis and reporting sex with women), all in the preceding 6 months.

Educational level was divided into low (ie, primary school or lower secondary vocational education), medium (ie, intermediate secondary general education, higher secondary general education, senior secondary vocational education or preuniversity secondary education), high (ie, higher professional or university education) and other (not fitting in one of the other categories).

Gender identity was determined by using the ‘two-step’ methodology.16 Individuals were first asked about their assigned gender at birth (assigned male at birth (AMAB) or assigned female at birth (AFAB)), and second about their current gender identity using the following options: (1) TGM/TGW, (2) man and woman, (3) neither man nor woman, (4) other or (5) not known yet.

Positivity rate of bacterial STI (chlamydia, gonorrhoea and/or infectious syphilis) and prevalence of HIV were analysed for each gender identity separately.

STI testing procedure

Urethral (in case of having a (neo)penis), pharyngeal (in case of giving fellatio), rectal (in case of receptive anal sex) and vaginal (in case of having a (neo)vagina) specimens were tested for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae with the Aptima Combo 2 assay (Hologic, Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA). In asymptomatic individuals, urine, rectal and vaginal specimens were self-collected, while in Amsterdam, medical staff collected rectal and/or vaginal specimens in symptomatic individuals. Medical staff collected pharyngeal specimens in all individuals. Those who had not previously tested HIV-positive were tested for HIV unless they actively opted out. HIV antibodies were tested with the HIV Ab/Ag test (LIAISON XL; DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy) or Advia HIV Ab/Ag combo assay (Advia Centaur; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Erlangen, Germany), and a treponemal test for syphilis serology was performed with the Treponema Screen (LIAISON XL, DiaSorin) or Advia Syphilis Assay (Advia Centaur, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics).

Statistical analysis

We used data from the first consultation of each individual in the study period. Characteristics were compared between (1) the different gender identities (stratified for AMAB and AFAB) and (2) SW versus non-sex workers (NSWs) using χ² tests, Fisher’s exact tests and Monte Carlo approximation of an exact test for categorical variables, and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables. To calculate the 95% (or in case of no events, 97.5%) CI for proportions, the exact method was used.

Data analyses were performed with SPSS package V.1.0 and STATA V.15.1. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Gender identities of study population

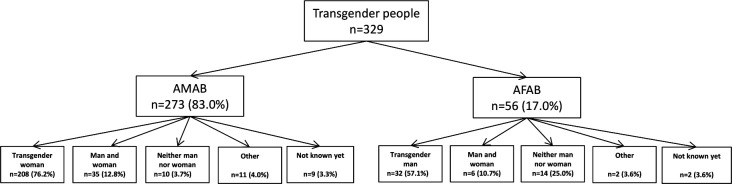

Between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2018, 329 unique TGP attended the STI clinics with a total of 656 consultations. Of those 329 unique TGP, 273 (83%) were AMAB and 56 (17%) were AFAB (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gender identities of transgender people AMAB and AFAB visiting the public health service of Amsterdam and The Hague, the Netherlands, January 2017–December 2018. AMAB, assigned male at birth; AFAB, assigned female at birth.

Among all TGP-AMAB, 76.2% (208/273) self-identified as TGWs, 12.8% (35/273) as both man and woman, 3.7% (10/273) as neither man nor woman, 4.0% (11/273) as other than previous options and 3.3% (9/237) did not know how to identify themselves (table 1). Among TGP-AFAB, 57.1% (32/56) identified as TGM, 10.7% (6/56) as male and female, 25.0% (14/56) as neither man nor woman 3.6% (2/56) as other than previous options and 3.6% (2/56) did not know how to self-identify.

Table 1.

Baseline data of sociodemographic characteristics, sexual behaviour, STI diagnosis and HIV status according to self-identified gender of TGP-AMAB visiting the public health services of Amsterdam and The Hague, the Netherlands, January 2017–December 2018

| Transgender woman n=208 (76.2%) n (%) |

Man and woman n=35 (12.8%) n (%) |

Neither man nor woman n=10 (3.7%) n (%) |

Other n=11 (4.0%) n (%) |

Not known yet n=9 (3.3%) n (%) |

P value | Total N=273 n (%) |

|

| Demographics | |||||||

| Median age in years (IQR) | 34 (27–44) | 35 27–39) | 22 (19–27) | 35 (28–47) | 27 (24–34) | <0.001 | 33 (27–43) |

| Education (n=23 missing) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low | 20 (10.5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (20.0) | 3 (33.3) | 25 (10.0) | |

| Middle | 35 (18.3) | 9 (30.0) | 9 (90.0) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (11.1) | 55 (22.0) | |

| High | 32 (16.8) | 15 (50.0) | 1 (10.0) | 5 (50.0) | 4 (44.4) | 57 (22.8) | |

| Other | 104 (54.5) | 9 (20.0) | 0 | 2 (20.0) | 1 (11.1) | 113 (45.2) | |

| Ethnic origin* | 0.002 | ||||||

| The Netherlands | 32 (15.4) | 9 (25.7) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (22.2) | 25 (19.0) | |

| Asia | 41 (19.7) | 7 (20.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 49 (17.9) | |

| Africa | 5 (2.4) | 5 (14.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (3.07) | |

| Latin America or the Caribbean | 104 (50.0) | 7 (20.0) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (36.4) | 5 (55.6) | 132 (45.1) | |

| Europe | 25 (12.0) | 6 (17.1) | 1 (10.0) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (11.1) | 37 (13.6) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.5) | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.7) | |

| Gender-affirming surgery | |||||||

| Vagina construction | 51 (24.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | <0.001 | 51 (18.7) |

| Sexual behaviour in the past 6 months | |||||||

| Median number of sex partners (IQR)† (missing n=26) | 40 (5–275) | 5 (3–35) | 5 (3–17) | 5 (3–13) | 9 (3–31) | <0.001 | 15 (4–200) |

| Sex work (missing n=16) | 125/197 (63.5) | 5/31 (16.1) | 1/10 (10.0) | 5/10 (50.0) | 1/9 (11.1) | <0.001 | 137/257 (53.3) |

| Sex with (missing n=6) | <0.001 | ||||||

| Men | 185 (91.1) | 22 (62.9) | 8 (80.0) | 7 (70.0) | 7 (77.8) | 229 (85.8) | |

| Women | 1 (0.5) | 2 (5.7) | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.5) | |

| Both | 17 (8.4) | 11 (31.4) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (22.2) | 34 (12.7) | |

| Partner type (missing n=27) | 0.002 | ||||||

| Steady only | 8 (4.1) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 0 | 10 (4.1) | |

| Casual only | 111 (58.7) | 19 (63.3) | 6 (66.7) | 9 (90.0) | 7 (87.5) | 152 (61.8) | |

| Steady and casual | 69 (36.5) | 9 (30.0) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (12.5) | 82 (33.3) | |

| No sex | 1 (0.5) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (0.8) | |

| Giving fellatio‡ | |||||||

| Giving condomless fellatio (n=26 missing) |

106/136 (77.9) | 16/16 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 7/7 (100) | 7/7 (100) | 0.068 | 141/171 (82.5) |

| Anal sex | |||||||

| Condomless receptive anal sex§ (n=29 missing) |

92/155 (59.4) | 12/18 (66.7) | 5/6 (83.3) | 5/9 (55.6) | 6/6 (100) | 0.246 | 120/194 (61.9) |

| Condomless insertive anal sex¶ (n=31 missing) |

46/88 (52.3) | 12/16 (75.0) | 3/4 (75.0) | 4/8 (50.0) | 4/4 (100) | 0.163 | 69/120 (57.5) |

| Vaginal sex (n=14 missing) | |||||||

| Condomless vaginal sex** | 32/48 (66.7) | 6/9 (66.7) | 2/2 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 2/2 (100) | 0.784 | 45/64 (70.3) |

| Bacterial STI | |||||||

| Any bacterial STI†† (n=6 missing) |

28/203 (13.8) | 8/35 (22.9) | 2/10 (20.0) | 0/10 | 2/9 (22.2) | 0.294 | 40/267 (15.0)‡‡ |

| Chlamydia (one or more locations) | 15/203 (7.2) | 6/35 (17.1) | 2/10 (20.0) | 0/10 | 1/9 (11.1) | 0.318 | 24/267 (9.0) |

| Pharyngeal | 2/189 (1.0) | 1/33 (3.0) | 0/8 | 0/10 | 0/9 | 0.550 | 3/258 (1.2) |

| Rectal | 10/197 (5.1) | 5/34 (14.7) | 2/9 (22.2) | 0/10 | 1/9 (11.1) | 0.052 | 18/259 (6.9) |

| Urethral (penis) | 2/154 (1.3) | 2/35 (5.7) | 0/10 | 0/10 | 1/9 (11.1) | 0.159 | 5/218 (2.3) |

| Urethral (neovagina, n=2 missing) | 2/49 (4.1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2/49 (4.1) | |

| Gonorrhoea (one or more locations) | 13/203 (6.4) | 2/35 (5.7) | 0/10 | 0/10 | 1/9 (11.1) | 0.826 | 16/267 (6.0) |

| Pharyngeal | 5/199 (2.5) | 2/33 (6.1) | 0/9 | 0/10 | 1/9 (11.1) | 0.290 | 8/260 (3.1) |

| Rectal | 10/197 (5.1) | 1/34 (2.9) | 0/9 | 0/10 | 0/9 | 0.563 | 11/259 (4.2) |

| Urethral (penis) | 0/154 | 0/35 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/9 | 0/218 | |

| Urethral (neovagina, n=2 missing) | 0/49 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0/49 | |

| Infectious syphilis (n=9 missing) | 3/201 (1.5) | 1/35 (2.9) | 0/9 | 0/10 | 0/9 | 0.666 | 4/264 (1.5) |

| HIV (n=6 missing) | 0.164 | ||||||

| Opt-out | 4/203 (2.0) | 1/35 (2.9) | 1/10 (10.0) | 0/10 | 0/9 | 6/267 (2.2) | |

| Known positive | 31/203 (15.3) | 3/35 (8.6) | 0 | 1/10 (10.0) | 2/9 (22.2) | 37/267 (13.9) | |

| Negative tested | 168/203 (82.8) | 29/35 (82.9) | 9/10 (90.0) | 9/10 (90.0) | 7/9 (77.8) | 222/267 (83.1) | |

| Positive tested | 0 | 2/35 (5.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/267 (0.7)‡‡ |

*Ethnicity was defined according to Statistics Netherlands on the basis of country of birth, maternal and paternal countries of birth.26

†Giving fellatio, vaginal and/or anal sex.

‡Among those who reported giving fellatio (only data from Amsterdam).

§Among those who reported receptive anal sex with men.

¶Among those who reported insertive anal sex and currently have a penis.

**Among those who reported vaginal sex and currently having a vagina and having sex with men or if currently having a penis and having sex with women.

††Bacterial STI: chlamydia, gonorrhoea and/or infectious syphilis.

‡‡New diagnoses among TGP-AMAB who have been tested for HIV 0.9% (2/224).

NA, not applicable; TGP-AMAB, transgender people assigned male at birth.

Transgender people assigned male at birth

Demographics and sexual behaviour

The median age of TGP-AMAB was 33 years (IQR 27–43) and differed significantly between the gender identities (p<0.001) (table 1). A high proportion of TGP-AMAB originated from Latin America or the Caribbean (132/273, 45.1%).

Genital gender-affirming surgery (gGAS) (vagina construction) was reported by 51/208 TGWs (24.5%). The median number of sex partners in the past 6 months was 15 (IQR 4–200), ranging from five among TGP who identify as ‘other’ (IQR 3–13) to 40 among TGW (IQR 5–275) (p<0.001).

The majority of TGP-AMAB (229/273, 85.8%) had sex with men only, whereas 1.5% had sex only with women and 12.7% with both men and women.

Receptive CAS (120/194, 61.9%), insertive CAS (69/120, 57.5%) and CVS (45/64, 70.3%) were reported often and did not differ between gender identities.

STI and HIV diagnosis

Bacterial STI positivity was 13.8% (28/203, 95% CI 9.4% to 19.3%) among TGWs, 22.9% (8/35, 95% CI 10.4% to 40.1%) among TGP-AMAB who self-identify as man and woman, 20.0% (2/10, 95% CI 2.5% to 55.6%) among TGP-AMAB who self-identify as neither man nor woman, 0% (1-sided, 97.5% CI 0.0% to 30.8%) among those who identify as other than previous options and 22.2% (2/9, 95% CI 0.3% to 48.2%) among persons who do not know their gender identity (p=0.294). The association between gender identities and a positive diagnosis of rectal chlamydia was borderline significant (p=0.052), with the highest positivity rate among TGP-AMAB who self-identify as neither man nor woman (2/9, 22.2%; 95 % CI 2.8% to 60.0%).

Among TGP-AMAB who have been tested for HIV during their consultation, two new HIV infections were diagnosed (2/224, 0.9%; 95% CI 0.1% to 3.2%). Of all TGP-AMAB, 39/267 (14.6%, 95% CI 10.6% to 19.4%) were HIV-positive (37 known positive and 2 newly diagnosed).

SWs versus NSWs (TGP-AMAB)

More than half (137/257, 53.3%; 95% CI 47.0% to 59.5%) of all TGP-AMAB reported sex work in the past 6 months, with the highest proportion among TGWs (125/197, 63.5%). TGP-AMAB who engaged in sex work in the past 6 months were significantly older (median 38 vs 29; p<0.001) more often originated from Latin America or the Caribbean (84/137, 61.3% vs 37/120, 30.8%; p<0.001) and more often underwent gender-affirming surgery (34/137, 24.8%) than NSWs (12/120, 10.0%, p=0.002) (table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline data of sociodemographic characteristics, sexual behaviour, STI diagnosis and new HIV diagnosis according to self-identified gender of TGP-AMAB visiting the public health service of Amsterdam and The Hague, the Netherlands, January 2017–December 2018, comparing SWs versus NSWs

| Sex work in past 6 months (n=16 missing)* | SWs n=137 (53.3%) n (%) |

NSWs n=120 (46.7%) n (%) |

P value | Total N=257 n (%) |

| Demographics | ||||

| Median age in years (IQR) | 38 (31–47) | 29 (24–36) | <0.001 | 33 (27–44) |

| Education (n=11 missing) | <0.001 | |||

| Low | 12 (9.2) | 13 (11.2) | 25 (10.2) | |

| Middle | 15 (11.5) | 38 (32.8) | 53 (21.5) | |

| High | 16 (12.3) | 39 (33.6) | 55 (22.4) | |

| Other | 87 (66.9) | 26 (22.4) | 113 (45.9) | |

| Ethnic origin† | <0.001 | |||

| The Netherlands | 16 (11.7) | 33 (27.5) | 49 (19.1) | |

| Asia | 16 (11.7) | 25 (20.8) | 41 (16.0) | |

| Africa | 4 (2.9) | 5 (4.2) | 9 (3.5) | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 84 (61.3) | 37 (30.8) | 121 (47.1) | |

| Europe | 17 (12.4) | 19 (15.8) | 36 (14.0) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Gender-affirming surgery | ||||

| Vagina construction | 34 (24.8) | 12 (10.0) | 0.002 | 46 (17.9) |

| Sexual behaviour in past 6 months | ||||

| Median number of sex partners (IQR)‡ (n=26 missing) | 155 (3–400) | 4 (2–10) | <0.001 | 15 (4–200) |

| Sex with | 0.029 | |||

| Men | 123 (89.8) | 97 (80.8) | 220 (85.6) | |

| Women | 0 | 4 (3.3) | 4 (1.6) | |

| Both | 14 (10.2) | 19 (15.8) | 33 (12.8) | |

| Partner type (n=27 missing) | 0.002 | |||

| Steady only | 1 (0.7) | 9 (8.3) | 10 (4.1) | |

| Casual only | 83 (60.6) | 69 (63.3) | 152 (61.8) | |

| Steady and casual | 53 (38.7) | 29 (26.6) | 82 (33.3) | |

| No sex | 0 | 2 (1.8) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Giving fellatio§ | ||||

| Giving condomless fellatio (n=26 missing) | 70/98 (71.4) | 71/73 (97.3) | <0.001 | 141/171 (82.5) |

| Anal sex | ||||

| Condomless receptive anal sex¶ (n=31 missing) | 62/111 (55.9) | 58/83 (69.9) | 0.053 | 120/194 (61.9) |

| Condomless insertive anal sex** (n=31 missing) | 42/80 (52.5) | 27/40 (67.5) | 0.170 | 69/120 (57.5) |

| Vaginal sex†† (n=14 missing) | ||||

| Condomless vaginal sex | 29/41 (70.7) | 16/23 (69.6) | 0.999 | 45/64 (70.3) |

| Bacterial STI | ||||

| Any bacterial STI‡‡ (n=1 missing) | 16/137 (11.7) | 23/119 (19.3) | 0.116 | 39/256 (15.2) |

| Chlamydia | 11/137 (8.0) | 12/119 (10.1) | 0.663 | 23/256 (9.0) |

| Pharyngeal | 1/137 (0.7) | 2/110 (1.8) | 0.587 | 3/247 (1.2) |

| Rectal | 8/136 (5.9) | 9/113 (8.0) | 0.616 | 17/249 (6.8) |

| Urethral (penis) | 1/103 (1.0) | 4/107 (3.7) | 0.369 | 5/210 (2.4) |

| Urethral (vagina) | 1/34 (2.9) | 1/12 (8.3) | 0.999 | 2/46 (4.3) |

| Gonorrhoea | 7/137 (5.1) | 9/119 (7.6) | 0.291 | 16/256 (6.2) |

| Pharyngeal | 3/137 (2.2) | 5/112 (4.5) | 0.473 | 8/249 (3.2) |

| Rectal | 5/136 (3.7) | 6/113 (5.3) | 0.553 | 11/249 (4.4) |

| Urethral (penis) | 0/103 | 0/107 | 0/210 | |

| Urethral (vagina) | 0/34 | 0/12 | 0/46 | |

| Infectious syphilis | 1/136 (0.7) | 3/117 (2.6) | 0.338 | 4/253 (1.6) |

| HIV (n=1 missng) | 0.204 | |||

| Opt-out | 1/137 (0.7) | 4/119 (3.4) | 5/256 (2.0) | |

| Known positive | 20/137 (14.6) | 16/119 (13.4) | 36/256 (14.1) | |

| Negative tested | 116/137 (84.7) | 97/119 (81.5) | 213/256 (83.2) | |

| Positive tested | 0 | 2/119 (1.7)§§ | 2/256 (0.8) |

*n=16 excluded from analysis.

†Ethnicity was defined according to Statistics Netherlands on the basis of country of birth, maternal and paternal countries of birth.26

‡Giving fellatio, vaginal and/or anal sex.

§Among those who reported giving fellatio (only data from Amsterdam).

¶Among those who reported receptive anal sex with men.

**Among those who reported insertive anal sex and currently having a penis.

††Among those who reported vaginal sex and currently having a vagina and having sex with men or if currently having a penis and having sex with women.

‡‡Bacterial STI: chlamydia, gonorrhoea and/or infectious syphilis.

§§New diagnoses among NSWs, TGP-AMAB who have been tested for HIV 2.0% (2/99).

NSW, non-sex worker; SW, sex worker; TGP-AMAB, transgender people assigned male at birth.

SWs had significantly more sex partners in the past 6 months, compared with NSWs (median: 155 vs 4, p<0.001). SWs reported borderline significantly less receptive CAS than NSWs (62/111, 55.9% vs 58/86, 69.9%; p=0.053).

The bacterial STI positivity rate was 11.7% (13/137, 95% CI 6.8% to 18.3%) among SWs and 19.3% (23/119, 95% CI 12.7% to 27.6%) among NSWs (p=0.116). The HIV prevalence was 20/137 (14.6%, 95% CI 9.2% to 21.6%) among SWs and 18/119 (15.1%, 95% CI 9.2% to 22.8%) among NSWs (p=0.204). Among SWs, no new HIV infections were diagnosed, compared with two new HIV diagnoses (2/99, 2.0%, 95% CI 0.2% to 7.1%) among NSWs.

Transgender people assigned female at birth

Demographics and sexual behaviour

The median age of TGP-AFAB was 24 years (IQR 21–31) and did not differ across the gender identities (p=0.938) (table 3). Most TGP-AFAB were of Dutch origin (25/56, 44.6%) and ethnic origin did not differ between gender identities (p=0.918). gGas (penis construction) was only reported among TGMs (3/37, 9.7%). Receptive CAS (8/12, 66.7%; p=0.774) and CVS (21/30, 70.0%; p=0.157) were reported often and did not differ between gender identities.

Table 3.

Baseline data of sociodemographic characteristics, sexual behaviour, STI diagnosis and HIV status, according to self-identified gender of TGP-AFAB visiting the public health service of Amsterdam and The Hague, the Netherlands, January 2017–December 2018

| Transgender men n=32 (57.1%) n (%) |

Man and woman n=6 (10.7%) n (%) |

Neither man nor woman n=14 (25.0%) n (%) |

Other n=2 (3.6%) n (%) |

Not known yet n=2 (3.6%) n (%) |

P value | Total N=56 n (%) |

|

| Demographics | |||||||

| Median age in years (IQR) | 26 (21–32) | 23 (20–30) | 23 (20–31) | –* | –* | 0.938 | 24 (21–31) |

| Education (n=9 missing) | 0.258 | ||||||

| Low | 2 (8.0) | 2 (40.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (8.5) | |

| Middle | 8 (32.0) | 0 | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 9 (19.1) | |

| High | 13 (52.0) | 2 (40.0) | 9 (69.2) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 28 (59.6) | |

| Other | 2 (8.0) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (23.1) | 0 | 0 | 6 (12.8) | |

| Ethnic origin† | 0.918 | ||||||

| The Netherlands | 14 (43.8) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (42.9) | 2 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 25 (44.6) | |

| Asia | 4 (12.5) | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 | 5 (8.9) | |

| Africa | 2 (6.2) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (21.4) | 0 | 0 | 7 (12.5) | |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 3 (9.4) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 6 (10.7) | |

| Europe | 5 (15.6) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 | 7 (12.5) | |

| Unknown | 4 (12.5) | 0 | 2 (14.3) | 0 | 0 | 6 (10.7) | |

| Gender-affirming surgery | 0.752 | ||||||

| Penis construction (n=1 missing) |

3/31 (9.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3/55 (5.5) | |

| Sexual behaviour in past 6 months | |||||||

| Median number of sex partners (IQR)‡ (n=9 missing) | 4(1–8) | 3(1–8) | 3(1–6) | –* | –* | 0.920 | 3 (1–6) |

| Sex work (n=7 missing) | 1/26 (3.8) | 1 (16.7) | 1/13 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 0.999 | 3/49 (6.1) |

| Sex with (n=2 missing) | 0.201 | ||||||

| Men | 16 (51.6) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (50) | 0 | 21 (38.9) | |

| Women | 7 (22.6) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (15.4) | 0 | 0 | 10 (18.5) | |

| Both | 8 (25.8) | 4 (66.7) | 8 (61.5) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 23 (42.6) | |

| Partner type (n=22 missing) | 18/32 | 4/6 | 8/14 | 0.200 | 34/56 | ||

| Steady only | 2 (11.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (5.9) | |

| Casual only | 13 (72.2) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (100) | 1 (50.0) | 20 (58.8) | |

| Steady and casual | 3 (16.7) | 2 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 11 (32.4) | |

| No sex | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.9) | |

| Giving fellatio§ | |||||||

| Giving condomless fellatio (n=18 missing) |

13/13 (100) | 3/3 (100) | 5/5 (100) | 0 | 2/2 (100) | 23/23 (100) | |

| Anal sex | |||||||

| Condomless receptive anal sex¶ (n=9 missing) |

4/8 (50.0) | 1/1 (100) | 1/1 (100) | 0 | 2/2 (100) | 0.774 | 8/12 (66.7) |

| Condomless insertive anal sex** (n=1 missing) |

0/2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0/2 | |

| Vaginal sex †† (n=8 missing) |

|||||||

| Condomless vaginal sex | 11/13 (84.6) | 3/5 (60.0) | 3/8 (37.5) | 2/2 (100) | 2/2 (100) | 0.157 | 21/30 (70.0) |

| Bacterial STI | |||||||

| Any bacterial STI‡‡ (n=2 missing) | 2/31 (6.5) | 0/6 | 1/13 (7.7) | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0.999 | 3/54 (5.6) |

| Chlamydia (one or more locations) | 2/31 (6.5) | 0/6 | 1/13 (7.7) | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0.999 | 3/54 (5.6) |

| Pharyngeal | 1/23 (4.3) | 0/6 | 0/11 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0.999 | 1/43 (2.3) |

| Rectal | 1/24 (4.2) | 0/6 | 0/11 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0.999 | 1/44 (2.3) |

| Urethral (vagina) | 1/26 (3.8) | 0/6 | 1/13 (7.7) | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0.999 | 2/49 (4.1) |

| Urethral (neopenis) | 0/3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0/3 | |

| Gonorrhoea (one or more locations) | 0/31 | 0/6 | 0/13 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/54 | |

| Pharyngeal | 0/23 | 0/6 | 0/11 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/43 | |

| Rectal | 0/24 | 0/6 | 0/11 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/44 | |

| Urethral (vagina) | 0/25 | 0/6 | 0/13 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/48 | |

| Urethral (neopenis) | 0/3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0/3 | |

| Infectious syphilis | 0/29 | 0/6 | 0/11 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/50 | |

| HIV (n=2 missing) | 0.727 | ||||||

| Opt-out | 2/31 (6.5) | 0 | 2/13 (15.4) | 0 | 0 | 4/54 (7.4) | |

| Known positive | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Negative tested | 29/31 (93.5) | 6 (100) | 11/13 (84.6) | 2 (100) | 2 (100) | 50/54 (92.6) | |

| Positive tested | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

*Too small sample size to calculate media and IQR (n=2).

†Ethnicity was defined according to Statistics Netherlands on the basis of country of birth, maternal and paternal countries of birth.26

‡Giving fellatio, vaginal and/or anal sex.

§Among those who reported giving fellatio (only data from Amsterdam).

¶Among those who reported receptive anal sex with men.

**Among those who reported insertive anal sex and currently having a penis.

††Among those who reported vaginal sex and currently having a vagina and having sex with men or if currently having a penis and having sex with women.

‡‡Bacterial STI: chlamydia, gonorrhoea and/or infectious syphilis.

NA, not applicable; TGP-AFAB, transgender people assigned female at birth.

The median number of sex partners in the previous 6 months among TGP-AFAB was 3 (IQR, 1–6) and did not differ between gender identities (p=0.920). Only three individuals (3/49, 6.1%, 95% CI 1.3% to 16.9%) reported sex work in the previous 6 months.

STI and HIV diagnosis

Chlamydia was diagnosed among TGM (2/31, 6.5%, 95% CI 0.8% to 21.4%) and individuals who self-identify as neither man nor woman (1/13, 7.7%, 95% CI 0.2% to 36.0%) (p=0.999). No other bacterial STI or HIV infections were found among TGP-AFAB. Likewise, no one was known to be HIV-positive.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the majority of TGP-AMAB identified as transwomen (76.2%). In contrast, 57.1% of the TGP-AFAB identified as transmen, yet a considerable proportion reported other identities; for example, 25% identified as neither man nor woman. This indicates that non-binary gender identities are important characteristics of the TGP population, especially for TGP-AFAB. A larger number of TGP-AMAB than TGP-AFAB attended the STI clinics. Compared with TGP-AFAB, the positivity rate for bacterial STI was high among TGP-AMAB. The HIV prevalence among TGP-AMAB was 14.6%. Among all TGP-AMAB who have been tested for HIV, 0.9% were newly diagnosed, whereas none of the TGP-AFAB were HIV-positive. In contrast to TGP-AFAB, a substantial part of TGP-AMAB engaged in sex work. The HIV prevalence among TGP-AMAB SWs was comparable to TGP-AMAB NSWs, whereas the STI positivity rate among TGP-AMAB SWs was lower than that of TGP-AMAB NSWs.

The implementation of a ‘two-step gender-identity question method’ led to an almost five-times increase in identifying the gender identity of TGP at STI clinics in the USA.16 17 Since 2017, the STI clinics of Amsterdam and The Hague have used a comparable two-step method by first asking all clients their assigned gender at birth, and second about their current gender identity with five subcategories. Although no comparison can be made with the period before 2017 (gender identity was not assessed), the number of TGP visiting the STI clinics seems relatively low. In the study period, TGP constitute merely 0.5% of the total population attending the STI clinics of Amsterdam and The Hague (data not shown), matching the estimated 0.6% of TGP in the total Dutch population.12 13 18 However, the attending rate might still be low as there is a likely higher proportion of TGP living in big cities like Amsterdam and The Hague. Studies from the USA demonstrate that factors which may discourage TGP from entering sexual healthcare include shame of being associated with STI or HIV, fear of stigma and discrimination, and experiencing non-gender-affirming sexual healthcare.19 20

In our study, we found that among TGP-AMAB, 0.9% were newly diagnosed with HIV. Compared with this group, the proportion of new HIV diagnoses among cisgender men who have sex with men (MSM), heterosexual men and women visiting the STI clinic of Amsterdam and The Hague in 2017–2018 were 0.5% vs 0.1% vs 0.1%, respectively. Furthermore, none of the TGP-AFAB were diagnosed with HIV. The latter is in line with the rates found in the few existing studies among TGMs in global literature limited by small sample sizes (ranging from 0% to 4%).3 4 21

Similar to the difference in HIV, TGP-AFAB (5.6%) show a substantially lower positivity rate of bacterial STI than TGP-AMAB (15.0%). Moreover, the positivity rate of STI in cisgender MSM, heterosexual men and women (19.1% vs 15.9% vs 13.1%, respectively) attending the STI clinic of Amsterdam and The Hague in 2017–2018, seems to correspond with that of TGP-AMAB, suggesting that STI attendees from these groups are equally affected by STI (personal communication with data manager of the STI clinics, M. Kroone, 2020). Consequently, in the Dutch setting, TGP-AFAB might be seen as a group within the TGP that is less at risk of contracting an STI.

In our study, a significant proportion (53.5%) of TGP-AMAB visiting the STI clinics engaged in sex work, which mirrors the reported 44% of TGWs engaging in sex work in the USA.22 Compared with NSWs, SWs in our study showed characteristics which likely increased HIV prevalence, namely, older age and having a higher number of sex partners in the past 6 months.23 We found that the HIV prevalence between SWs and NSWs was comparable (14.6% vs 15.1%). Although not statistically significant, bacterial STI positivity rates were lower among SWs compared with NSWs (11.7% vs 19.3%), and no new HIV diagnoses were found among SWs compared with two (2.0%) among NSWs. In previous studies, the likelihood of STI was also lower in transgender SWs than NSWs.5 An explanation might be that SWs are more aware of their risk and have taken safety precautions to reduce the risk of acquiring STI.

Another HIV risk-enhancing factor might be CVS. Irrespective of gender identity, a majority (70%) of TGP engaged in CVS. In TGP-AFAB who have not undergone gGAS, CVS might increase the risk of contracting HIV, since testosterone use can cause vaginal dryness and atrophy.3 This also applies for TGP-AMAB who underwent gGAS and have more risk of having neovaginal lesions due to dryer and atrophic mucosa.4

Our study has some limitations. First, our findings are not generalisable to all TGP, as in general the HIV and STI positivity rates of clients of sexual health clinics are higher than among the general population. Second, only the gender—male or female—of sexual partners of the participants was asked, resulting in uncertainty about whether these partners are TGP. Third, the subgroups of gender identities have small sample sizes. Therefore, our results must be interpreted with caution. Fourth, data on educational level were categorised as other for more than 50%, mainly among TGP born outside the Netherlands. It may be possible that those educated in other countries have difficulty equating their education level to one of the levels in the Dutch system. Lastly, we did not consult the TGP community members to discuss the validity of the self-identified gender assignment.

Despite these limitations, we explored the epidemiology of HIV and STI among gender-diverse people attending two large STI clinics in the Netherlands. Moreover, we reported current genital anatomy, surgical history and anatomical sites of sexual exposure, leading to a broader picture of the sexual health of the TGP included in the study.

Physicians and other health providers taking care of TGP should take into account the different gender identities among TGP, as they vary in sexual behaviour, and involve TGP community members in the care provided. In our study, a larger proportion of TGP-AMAB than TGP-AFAB attended the STI clinics, and no new or known HIV infection was found among TGP-AFAB. It is unknown if they experience barriers or if they are truly not at risk of HIV or STI. To address this issue, we will conduct a prospective study among TGP in care at a TGP clinic with larger unbiased sample sizes and we will include detailed information on the gender of their sexual partners. This could help STI clinics and other services meet specific sexual health needs of gender-diverse communities. Moreover, we will seek community involvement to provide insight into barriers to attending STI clinics experienced by TGP and how these can be eliminated.

We advise healthcare providers working with TGP to offer routine HIV testing at a low threshold to TGP with an increased risk of HIV infection and STI. Moreover, TGWs are included as a key group for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in most guidelines, but uptake is low.24 25 The commitment of gender-affirming healthcare facilities and community involvement are needed to increase PrEP uptake.

In conclusion, we report the first study in the Netherlands assessing sexual behaviour, HIV prevalence and STI positivity rates among TGP with five different gender identities visiting the STI clinics of Amsterdam and The Hague and compared these outcomes between TGP who reported sex work and those who did not. STI clinics serve more TGP-AMAB than TGP-AFAB, and the majority of TGP-AMAB seen in these clinics are engaged in sex work. HIV prevalence and STI positivity rates were substantial among TGP-AMAB and lower among TGP-AFAB, but sample sizes were small and testing uptake might be low. Studies should be performed to provide insight into whether the larger populations of TGP-AMAB and TGP-AFAB are at risk of HIV infection and STI.

Key messages.

Non-binary gender identities are important characteristics of transgender STI clinic visitors, especially those assigned female at birth.

Given the differences in demographics and sexual behaviour, transgender people should not be categorised and served as a single group.

HIV and STI are more prevalent in transgender people assigned male at birth than in transgender people assigned female at birth attending STI clinics in the Netherlands.

Future research into the sexual health needs of gender-diverse communities and community engagement is necessary to improve sexual health care.

sextrans-2020-054875supp001.pdf (165.5KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Handling editor: Tristan J Barber

Contributors: SD, CD, MvR, EH and HDV designed the study protocol. SD performed the statistical analysis. Results were thoroughly discussed by SD, CD, EH and MvR. SD and CD drafted the paper. All authors commented on draft versions and approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Obtaining ethical approval for the study was not deemed necessary according to Dutch law, as the study used routinely collected, de-identified surveillance data.

References

- 1. Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, et al. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:214–22. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McNulty A, Bourne C. Transgender HIV and sexually transmissible infections. Sex Health 2017;14:451–5. 10.1071/SH17050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ackerley CG, Poteat T, Kelley CF. Human immunodeficiency virus in transgender persons. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2019;48:453–64. 10.1016/j.ecl.2019.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Poteat T, Scheim A, Xavier J, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection and related Syndemics affecting transgender people. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;72:S210–9. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Callander D, Cook T, Read P, et al. Sexually transmissible infections among transgender men and women attending Australian sexual health clinics. Med J Aust 2019;211:406–11. 10.5694/mja2.50322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nadal KL, Davidoff KC, Fujii-Doe W. Transgender women and the sex work industry: roots in systemic, institutional, and interpersonal discrimination. J Trauma Dissociation 2014;15:169–83. 10.1080/15299732.2014.867572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Operario D, Soma T, Underhill K. Sex work and HIV status among transgender women: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48:97–103. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816e3971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Veen MG, Götz HM, van Leeuwen PA, et al. HIV and sexual risk behavior among commercial sex workers in the Netherlands. Arch Sex Behav 2010;39:714–23. 10.1007/s10508-008-9396-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drückler S, van Rooijen MS, de Vries HJC. Substance use and sexual risk behavior among male and transgender women sex workers at the prostitution outreach center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Sex Transm Dis 2020;47:114–21. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Center of Excellence for Transgender Health . Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender Nonbinary people. Available: http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/trans?page=guidelines-home [Accessed 17 Jun 2016].

- 11. Thomson RM, Katikireddi SV. Improving the health of trans people: the need for good data. Lancet Public Health 2019;4:e369–70. 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30129-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. GGD Amsterdam . Soapolikliniek GGD Amsterdam- Jaarcijfers 2017/2018. Available: https://www.ggd.amsterdam.nl/ggd/publicaties/jaarverslagen/

- 13. Centrum Seksuele Gezondheid . Jaarverslagen van Het Centrum Seksuele Gezondheid GGD Haaglanden (CSG) 2017/2018. Available: https://www.seksuelegezondheidhaaglanden.nl/professionals/expertisecentrum/

- 14. National Institute of Public Health and the Environment . Sexually transmitted infections in the Netherlands in 2018, 2019. Available: https://www.rivm.nl/bibliotheek/rapporten/2019-0007.pdf

- 15. Alders M. Classification of the population with a foreign background in the Netherlands. Available: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/publicatie/2002/05/classification-of-the-population-with-a-foreign-background-in-the-netherlands

- 16. Tordoff DM, Morgan J, Dombrowski JC, et al. Increased ascertainment of transgender and Non-binary patients using a 2-step versus 1-Step gender identity intake question in an STD clinic setting. Sex Transm Dis 2019;46:254–9. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tate CC, Ledbetter JN, Youssef CP. A two-question method for assessing gender categories in the social and medical sciences. J Sex Res 2013;50:767–76. 10.1080/00224499.2012.690110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuyper L. Transgenderpersonen in Nederland. den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau, 2017. Available: https://www.scp.nl/publicaties/publicaties/2017/05/09/transgender-personen-in-nederland

- 19. Sevelius JM, Patouhas E, Keatley JG, et al. Barriers and facilitators to engagement and retention in care among transgender women living with human immunodeficiency virus. Ann Behav Med 2014;47:5–16. 10.1007/s12160-013-9565-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grant JM ML, Tanis JE. Injustice at every turn: a report of the national transgender discrimination survey, 2011. Available: https://www.thetaskforce.org/injustice-every-turn-report-national-transgender-discrimination-survey/

- 21. McFarland W, Wilson EC, Raymond HF. Sexual prevalence, sexual partners, sexual behavior and HIV acquisition risk among trans men, San Francisco, 2014. AIDS Behav 2017;21:3346–52. 10.1007/s10461-017-1735-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schulden JD, Song B, Barros A, et al. Rapid HIV testing in transgender communities by community-based organizations in three cities. Public Health Rep 2008;123:101–14. 10.1177/00333549081230S313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Weissman A, Ngak S, Srean C, et al. Hiv prevalence and risks associated with HIV infection among transgender individuals in Cambodia. PLoS One 2016;11:e0152906. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Poteat TC, Radix A. HIV antiretroviral treatment and pre-exposure prophylaxis in transgender individuals. Drugs 2020;80:965–72. 10.1007/s40265-020-01313-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cdc launches prevention efforts focused on PreP, high-risk groups. AIDS Policy Law 2015;30:1:4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alders M. Classification of the population with a foreign background in the Netherlands. Statistics Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

sextrans-2020-054875supp001.pdf (165.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.