Abstract

The concentrations of β-lactam antibiotics after standard doses were measured in blood and apocrine (axilla) and eccrine (forearm) sweat from six adult healthy persons. All persons had ceftazidime (axilla, 28.4 μg/ml; forearm, 11 μg/ml) and ceftriaxone (axilla, 8.9 μg/ml; forearm, 2.5 μg/ml) in sweat, and one person had cefuroxime in sweat (axilla, 7.8 μg/ml) (all data are mean peaks). Three persons had benzylpenicillin (axilla, 2.6 to 0.1 μg/ml) and one had phenoxymethylpenicillin (axilla, 0.4 μg/ml) in sweat. Excretion of β-lactam antibiotics in the sweat may explain why staphylococci so rapidly become resistant to these drugs.

Staphylococci, corynebacteria, and propionibacteria are the major genera inhabiting human skin. A few bacteria are found on the surface of desquamated scales of normal skin, but the bulk is found in the openings of the hair follicles. The bacteria are also present at the openings of sweat ducts but not in the intraepidermal portion of the ducts (15, 18). Development of resistance to antibiotics in staphylococci (e.g., Staphylococcus epidermidis and S. aureus) (21) is frequently seen when patients are treated while in hospital (9), and generally also in countries with high consumptions of antibiotics, and spread to other patients of such strains occurs (2, 10, 13, 16).

We have previously found (9) that the prevalence of methicillin resistance in coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS) in different wards of a major university hospital was significantly correlated to the total consumption of antibiotics, but not to the consumption of β-lactamase-stable penicillins such as dicloxacillin or early cephalosporins. On the other hand it was significantly correlated to the consumption of expanded-spectrum cephalosporins such as ceftazidime and carbapenems, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and trimetoprim (9). S. epidermidis is much more prevalent on the skin than S. aureus (15, 18), and methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis (MRSE) is far more prevalent than methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Methicillin resistance is associated with the presence of the penicillin-binding protein 2a, which is not present in susceptible staphylococci. This protein is encoded by the mecA gene. Evidence exists that there is a horizontal transfer of mec sequences from CNS to S. aureus (1, 4, 5). Antibiotics which promote development of MRSE may therefore subsequently lead to MRSA.

Antibiotics probably have to be excreted to the surface of the skin to interfere with the normal flora. A possible route of excretion would be the sweat glands. We have previously shown that ciprofloxacin is excreted in sweat (perspiration) and this leads to rapid development of multidrug-resistant MRSE (7, 8). We speculated whether excretion of β-lactam antibiotics in sweat could also be the biological background for the development of MRSE and MRSA. The aim of this study was therefore to measure the concentrations in blood, apocrine sweat (axilla), and eccrine sweat (volar surface of the forearm) of selected representative β-lactam antibiotics in adult healthy persons.

Healthy persons.

Fourteen of us did the experiments on ourselves. There were eight men and six women (age 33 to 56 years; weight, 54 to 93 kg). One of us was used for pilot experiments, and on the basis of those results the other 13 were enrolled into the study. All were healthy, and informed signed consent was given. The investigation was carried out according to the 1975 Tokyo revision of the Helsinki Declaration on ethics in human experimentation, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Drug administration, sample collection, and measurement of drug concentrations.

The following antibiotics were each given to six adults: benzylpenicillin, 1.2 g intravenously (i.v.) (5-min bolus); phenoxymethylpenicillin, 1.2 g orally (p.o.); cefuroxime, 1.5 g (i.v.); ceftriaxone, 2 g i.v.; and ceftazidime, 2 g i.v. (3 g was administered to the biggest person in the study). The concentrations of the antibiotics in blood, apocrine sweat (axilla), and eccrine sweat (volar surface of the forearm) were measured as described previously (7, 8). In brief, sweat production was stimulated by pilocarpine iontophoresis, the sweat was collected for 30-min periods by 20-mm-diameter paper disks (30 μl of sweat), and blood was collected midway through each of these periods at 30 min to 8 h after the antibiotics were given. A biological method was used for antibiotic measurement (test strains: Sarcinia lutea ATCC 9341 and Proteus rettgeri 9228/71; lower detection limits, 0.1 to 0.4 μg/ml). The sweat from antibiotic-free persons had no activity against these two strains. The reproducibility of the measurements of concentrations of antibiotics in sweat was 11.8% (variation coefficient) (7).

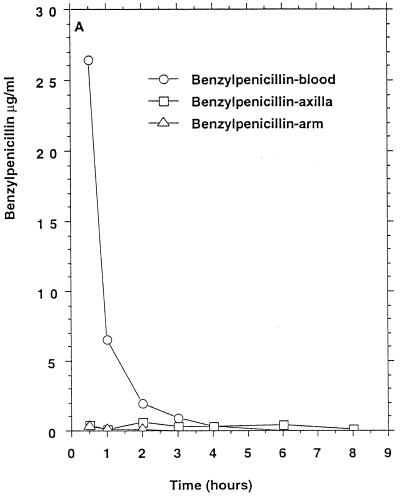

Benzylpenicillin.

Three of six persons had measurable benzylpenicillin concentrations in apocrine sweat (Table 1) which remained above the MIC at which 90% of the isolates tested are inhibited (MIC90) for penicillin-susceptible staphylococci for 8 h in two persons (Fig. 1A). Two of these persons also had measurable benzylpenicillin concentrations in eccrine sweat. Probenecid (1 g × 2 orally, 13 and 1 h before benzylpenicillin in one of the test persons) did not influence the excretion of benzylpenicillin.

TABLE 1.

Concentrations of antibiotics in sweat and blood of six healthy persons

| Drug | Dose (g) |

Cmax (μg/ml)/T (h) ina:

|

MIC90 (μg/ml) forf:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Axilla sweat | Forearm sweat | MSS | MRS | ||

| Benzylpenicillin | 1.2 | 27/0.5 (9–44) | 2.6, 2.1, 0.1b/0.5–2 | 1.5, 0.4c/0.5 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin | 1.2 | 8/1 (4.1–14) | 0.4d/4 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Cefuroxime | 1.5 | 62/1 (40–113) | 7.8e/0.5 | 3.1e/3 | 1–2 | ≥128 |

| Ceftriaxone | 2 | 372/1 (82–480) | 8.9/0.5 (0.7–16.2) | 2.5/0.5 (0.9–6.0) | 4 | ≥128 |

| Ceftazidime | 2 | 360/1 (160–920) | 28.4/0.5 (1.1–70) | 11/2 (1.0–23) | 4–8 | ≥128 |

Mean peak concentration in serum or sweat (Cmax)/time after administration of drug. Ranges of Cmax are given in parentheses.

Three of six persons had measurable concentrations (all are listed) (lower limit of detection, 0.1 μg/ml).

Two of six persons had measurable concentrations (both are listed) (lower limit of detection 0.1 μg/ml).

One of six persons had a measurable concentration (shown) (lower limit of detection, 0.1 μg/ml).

One of six persons had a measurable concentration (shown) (lower limit of detection, 0.4 μg/ml).

MSS and MRS, methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant staphylococci, respectively (data from reference 12).

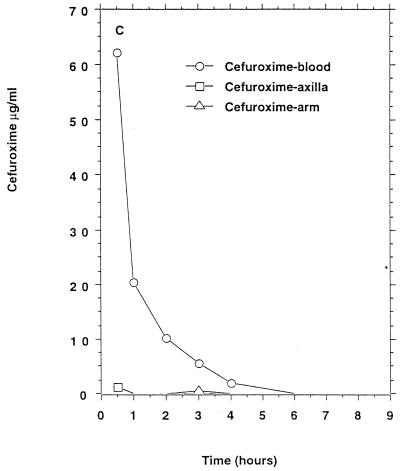

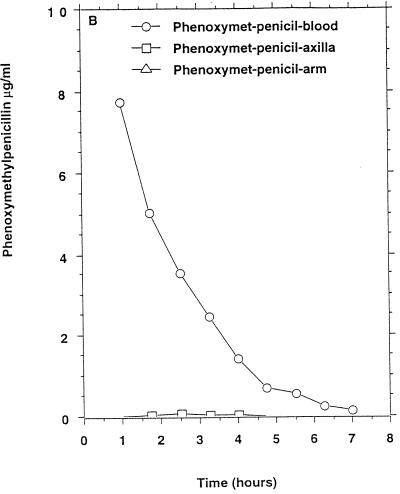

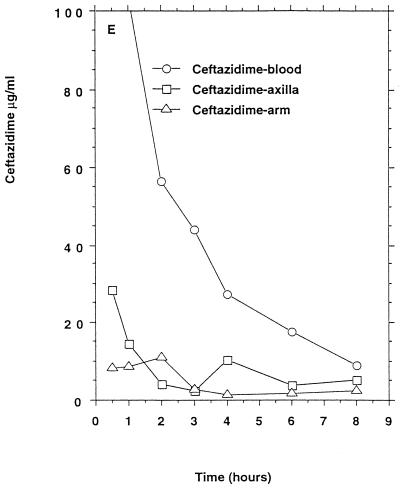

FIG. 1.

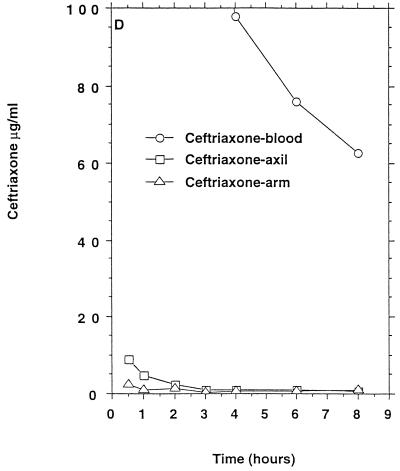

Mean β-lactam antibiotic concentrations in serum and sweat obtained from axilla and volar surface of the forearm after p.o. or i.v. (bolus) administration to six healthy persons. (A) Benzylpenicillin, 1.2 g i.v.; (B) phenoxymethylpenicillin, 1.2 g p.o. (C) cefuroxime, 1.5 g i.v.; (D) ceftriaxone, 2 g i.v.; (E) ceftazidime, 2 g i.v. No antibacterial activity of sweat was detectable before intake of the antibiotics. For comparison the MIC90s for susceptible staphylococci (in micrograms per milliliter) were as follows: benzylpenicillin, 0.03; phenoxymethylpenicillin, 0.06. The MIC90s for methicillin-susceptible and resistant staphylococci (in micrograms per milliliter) were as follows: cefuroxime, 1 to 2 and ≥128, respectively; ceftriaxone, 4 and ≥128, respectively; ceftazidime, 4 to 8 and ≥128, respectively.

Phenoxymethylpenicillin.

Only one of six persons had measurable phenoxymethylpenicillin concentrations in apocrine sweat (Table 1) which remained above the MIC90 for penicillin-susceptible staphylococci for 4 h (Fig. 1B).

Cefuroxime.

Only one of six persons had measurable cefuroxime concentrations in apocrine sweat (Table 1) which remained above the MIC90 for methicillin-susceptible staphylococci, and this person had also measurable concentrations in eccrine sweat (Fig. 1C) above the MIC90 for methicillin-susceptible staphylococci but below the MIC90 for methicillin-resistant staphylococci.

Ceftriaxone.

All six persons had measurable ceftriaxone concentrations in apocrine and eccrine sweat (Table 1) which remained above the MIC90 for methicillin-susceptible staphylococci for 0.5 to 4 h (axilla) and for 0.5 to 2 h (forearm) (Fig. 1D) but below the MIC90 for methicillin-resistant staphylococci.

Ceftazidime.

All six persons had measurable ceftazidime concentrations in apocrine and eccrine sweat (Table 1) which, in both types of sweat, remained above the ceftazidime MIC90 for methicillin-susceptible staphylococci for 0.5 to 8 h (Fig. 1D) but below the ceftazidime MIC90 for methicillin-resistant staphylococci.

The first MRSA was isolated in the United Kingdom in 1960 (3), and during the following 10 years an increasing prevalence was reported in Europe before a decrease was observed in the 1970s. During the second half of the 1970s, new multidrug-resistant MRSA strains emerged, which were resistant to gentamicin and were isolated progressively in an increasing number of countries, finally resulting in the present pandemic (14). The massive use of gentamicin in the 1970s was proposed as a cause responsible for the emergence of these new MRSA strains, but many broad-spectrum antibiotics were also being marketed at that time, including expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in the 1980s. Witte et al. (22) reported an increase of MRSA in central Europe from 1984 to 1995 and that many clones were involved. The introduction of fluoroquinolones at the end of the 1980s was quickly followed by the emergence of resistant mutants among MRSA (14). Likewise, Speller et al. (19) reported an increase of MRSA in England and Wales from 1989 to 1995, including resistance to ciprofloxacin. Crowcroft et al. (6) reported the incidence of nosocomial MRSA in 50 Belgian hospitals in 1994 and 1995. They found a significant correlation with the consumption of some expanded-spectrum cephalsporins (ceftazidime and cefulodin), ciprofloxacin, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, but no correlation with the consumption of ceftriaxone-cefotaxime or the early cephalosporins, benzylpenicillin, phenoxymethylpenicillin, or β-lactamase-stable penicillins. Recently, rapid emergence of resistant CNS on the skin after antibiotic prophylaxis was reported by Terpstra et al. (20) who showed that amoxicillin-clavulanate selected for resistance to cloxacillin, whereas ofloxacillin selected for resistance for both ofloxacillin and cloxacillin (20).

Benzylpenicillin has been in clinical use since approximately 1943, phenoxymethylpenicillin has been in use since approximately 1953, and cefuroxime has been in use since approximately 1980. The present study shows that the pharmacokinetic basis exists for these early β-lactam antibiotics to influence the normal skin flora in some persons, since the MIC for staphylococci is below the concentrations measured in sweat of at least these persons. Ceftriaxone and ceftazidime have both been in clinical use since approximately 1985. The pharmacokinetic basis is indeed present for a more pronounced influence on the skin flora of these two expanded-spectrum cephalosporins since prolonged and high concentrations of these drugs were excreted in the sweat of all the persons tested.

According to these results, therefore, excretion of benzylpenicillin in sweat may have contributed to the selection of β-lactamase-producing staphylococci soon after the introduction of this antibiotic more than 50 years ago (2, 13, 17). Excretion of ceftriaxone and especially ceftazidime in sweat may, on the other hand, have contributed significantly to the present worldwide selection for and spread of MRSA and MRSE (10, 16). This is in accordance with the correlation found between the use of these drugs and the incidence and prevalence of MRSE and MRSA in several studies (6, 9) and the correlation between the decreased usage of expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and the reduced number of patients with MRSA (21). We have previously shown that ciprofloxacin is excreted in sweat and this leads to rapid development of multidrug-resistant S. epidermidis strains which are also resistant to methicillin (7, 8). The mechanism responsible has not been investigated, but efflux resistance may be suggested. These findings are in accordance with the results of the study mentioned above (20) which showed that ofloxacin prophylaxis was followed by development of resistance to that drug and to cloxacillin. The excretion of β-lactam antibiotics, notably expanded-spectrum cephalosporins, and fluoroquinolones in sweat may, therefore, be the biological explanation for the close temporal relationship between the marketing of these antibiotics and the increase of MRSA reported in, e.g., the United Kingdom and central Europe (19, 22).

REFERENCES

- 1.Archer G L, Niemeyer D M, Thanassi J A, Pucci M J. Dissemination among staphylococci of DNA sequences associated with methicillin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:447–454. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.3.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barber M, Rozwadowska-Dowzenko M. Infection by penicillin-resistant Staphylococci. Lancet. 1948;ii:641–644. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(48)92166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber M. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci. J Clin Pathol. 1960;II:385–393. doi: 10.1136/jcp.14.4.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brakstad O D, Mæland J A. Mechanisms of methicillin resistance in staphylococci. APMIS. 1997;105:264–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1997.tb00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers H F. Penicillin-binding protein-mediated resistance in pneumococci and staphylococci. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl. 2):S353–359. doi: 10.1086/513854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowcroft N S, Ronveaux O, Monnet D L, Mertens R. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococus aureus and antimicrobial use in Belgian hospitals. Infect Control Epidemiol. 1999;20:31–36. doi: 10.1086/501555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Høiby N, Jarløv J O, Kemp M, Tvede M, Bangsborg J M, Kjerulf A, Pers C, Hansen H. Excretion of ciprofloxacin in sweat and multiresistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. Lancet. 1997;349:167–169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09229-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Høiby N, Johansen H K, Jarløv J O, Westh H, Prag J B, Bangsborg J M, Moser C, Kemp M, Hornsleth A K, Hansen H. Ciprofloxacin in sweat and antibiotic resistance. Lancet. 1995;346:1235. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92946-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarløv J O, Høiby N. Coagulase-negative staphylococci in a major Danish university hospital: diversity in antibiotic susceptibility between wards. APMIS. 1998;106:411–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1998.tb01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kayser F H, Waldvogel F A, editors. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1986;5:689–730. doi: 10.1007/BF02013306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landman D, Chockalingam M, Quale J M. Reduction in the incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and ceftazidime-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae following changes in a hospital antibiotic formulary. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1062–1066. doi: 10.1086/514743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 4th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. p. 1238. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mård P-A, editor. Coagulase-negative Staphylocci. Stockholm, Sweden: Almqvist & Wiksel; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monnet D L. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and its relationship to antimicrobial use: possible implications for control. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1998;19:552–559. doi: 10.1086/647872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montes L F, Wilborn W H. Anatomical location of normal skin flora. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Philips I, editor. Focus on coagulase-negative Staphylococci. International Congress and Symposium Series. Vol. 151. London, United Kingdom: Royal Society of Medicine; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rammelkamp C H, Maxon T. Resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to the action of penicillin. Proc Soc Exp Biol. 1942;51:386–94. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth R R, James W D. Microbial ecology of the skin. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;42:441–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speller D C E, Johnson A P, James D, Marples R R, Charlett A, George R C. Resistance to methicillin and other antibiotics in isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from blood and cerebrospinal fluid, England and Wales, 1989–95. Lancet. 1997;350:323–325. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)12148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terpstra S, Noordhoek G T, Voesten H G J, Hendriks B, Degener J E. Rapid emergence of resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci on the skin after antibiotic prophylaxis. J Hosp Infect. 1999;43:195–202. doi: 10.1053/jhin.1999.0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wise R, Hart T, Cars O, Streulens M, Helmuth R, Huovinen P, Sprenger M. Antimicrobial resistance is a major threat to public health. B Med J. 1998;317:609–610. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7159.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witte W, Kresken M, Braulke C, Cuny C. Increasing incidence and widespread dissemination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in hospitals in central Europe, with special reference to German hospitals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:414–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]