Abstract

Tissue injury leads to the well-orchestrated mobilization of systemic and local innate and adaptive immune cells. During aging, immune cell recruitment is dysregulated, resulting in an aberrant inflammatory response that is detrimental for successful healing. Here, we precisely define the systemic and local immune cell response after femur fracture in young and aging mice and identify increased toll-like receptor signaling as a potential culprit for the abnormal immune cell recruitment observed in aging animals. Myd88, an upstream regulator of TLR-signaling lies at the core of this aging phenotype, and local treatment of femur fractures with a Myd88 antagonist in middle-aged mice reverses the aging phenotype of impaired fracture healing, thus offering a promising therapeutic target that could overcome the negative impact of aging on bone regeneration.

Keywords: regeneration, skeletal stem cells, aging, innate immunity, adaptive immunity, inflammaging

Introduction

While bone possesses an astounding capability to regenerate in response to injury, this process becomes less efficient with age. At the core of fracture healing lies the skeletal stem and progenitor cell (SSPC), which responds to injury by initially proliferating followed by differentiation into chondrocytes and osteoblasts. Chronological aging and inflammaging, a chronic state of low-grade inflammation in aged organisms [1], contribute to the loss of SSPC number and function [2]. This functional decline of the skeletal stem cell results in a decreased regenerative response to fracture in the elderly. Recent evidence suggests that this cell-intrinsic dysfunction can be reversed by treating the chronic systemic inflammatory response observed during aging [2]. Immune cells produce and respond to inflammatory signals and there is ample evidence that the innate immune response to injury is also altered during aging [3–5]. In particular, the recruitment of pro-inflammatory macrophages to the fracture site has been linked to impaired bone healing in aging animals (reviewed in [4]). However, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding the contribution and alteration of the adaptive immune cell response to fracture healing during aging, and the molecular regulators governing this process.

There is growing evidence that T cells, key players in adaptive immunity, contribute to fracture repair, even in the absence of infectious stimuli, by modulating the local cytokine milieu in the fracture callus [6]. In this current study, we precisely define the systemic and local immune cell response after femur fracture in young and middle-aged mice and identify increased toll-like receptor signaling as a potential culprit for the aberrant immune cell recruitment observed in aging animals. Using an inhibitor of TLR-signaling reverses the aging phenotype of impaired fracture healing, thus offering a promising therapeutic target that could overcome the detrimental effects of aging on bone regeneration.

Results

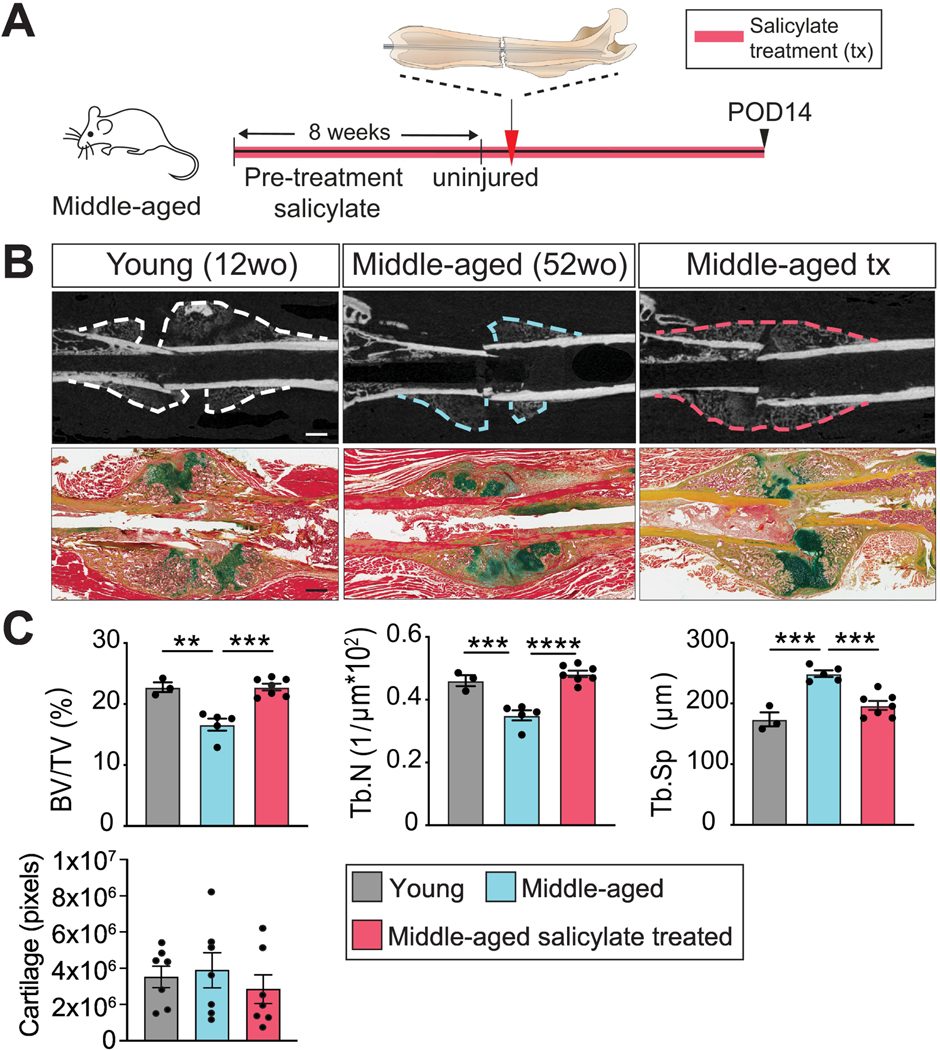

Systemic anti-inflammatory treatment enhances early bone healing in aging animals

We recently found that inflammaging impairs SSPC function [2]. In keeping with this, we observed that when mice were subjected to a femoral shaft fracture (Fig. 1A), middle-aged animals (52-week-old) exhibited impaired healing compared to young, 12-week-old animals, as demonstrated by decreased bone volume over total volume (BV/TV) and trabecular number (Tb.N.), and increased trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp) (Fig. 1B, C). We then treated middle-aged mice with sodium salicylate, a well-tolerated anti-inflammatory drug that results in a measurable decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokine release in aging animals [2]. Middle-aged mice were treated for 8 weeks and then subjected to a femoral shaft fracture while maintaining drug treatment during the healing process (Fig. 1A). Middle-aged mice treated with sodium salicylate demonstrated enhanced fracture healing compared to untreated middle-aged animals, which was equivalent to the regenerative response observed in their young counterparts (Fig. 1C). These data demonstrate that increased inflammation is detrimental to successful fracture healing and that a fine-tuned inflammatory response allows for successful tissue regeneration.

Fig. 1. Systemic anti-inflammatory treatment results in improved fracture healing in middle-aged mice.

(A) Experimental outline. Middle-aged mice were treated with the antiinflammatory, sodium salicylate, for 8 weeks followed by femoral fracture (red arrowhead). Histomorphometric analysis of fracture healing was then performed at POD 14. (B) Representative longitudinal sections of femoral shaft fractures imaged using μCT (upper panels, scale bar 1 mm) and Pentachrome histology (lower panels, scale bar 1 mm) in young, middleaged and middle-aged salicylate treated mice after POD 14. Yellow = bone. Green = cartilage. Red = muscle. (C) μCT quantification of BV/TV, Tb.N and Tb.Sp (each point represents an individual mouse) and histomorphometry of cartilage volume (each point represents an individual section) at POD 14. Data represented as mean +/− SEM. N = 3–7. Abbreviation: BV/TV, bone volume/total volume; POD, post-operative day; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Sp, trabecular spacing; tx, treated. ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001, **** p<0.00001, unpaired t-test.

Early systemic immune cell mobilization after long bone fracture

Upon injury, inflammation regulates mobilization of the immune system and immune cells, such as Thelper cells and macrophages, release pro-inflammatory molecules. Therefore we next asked whether the change in inflammation state during aging is associated with a change in the immune cell response during fracture repair. Local tissue damage is often accompanied by a systemic immune response, which may modulate, potentiate or abate the local tissue immunity [7, 8]. While the systemic immune behavior to fracture in young animals has been characterized (reviewed in [9]), the impact of aging on the systemic immune response and its impact on long bone fracture healing is still poorly understood. To address this, we mapped systemic innate and adaptive immune behaviors at high temporal resolution in young versus aging animals. We performed femoral shaft fractures in young (12-week-old) and middle-aged (52-week-old) mice and, using a cohort of well-characterized lineage markers and flow cytometry, quantified the proportion of defined immune populations in peripheral blood during early fracture repair, when the inflammatory response peaks (Fig. 2A-E).

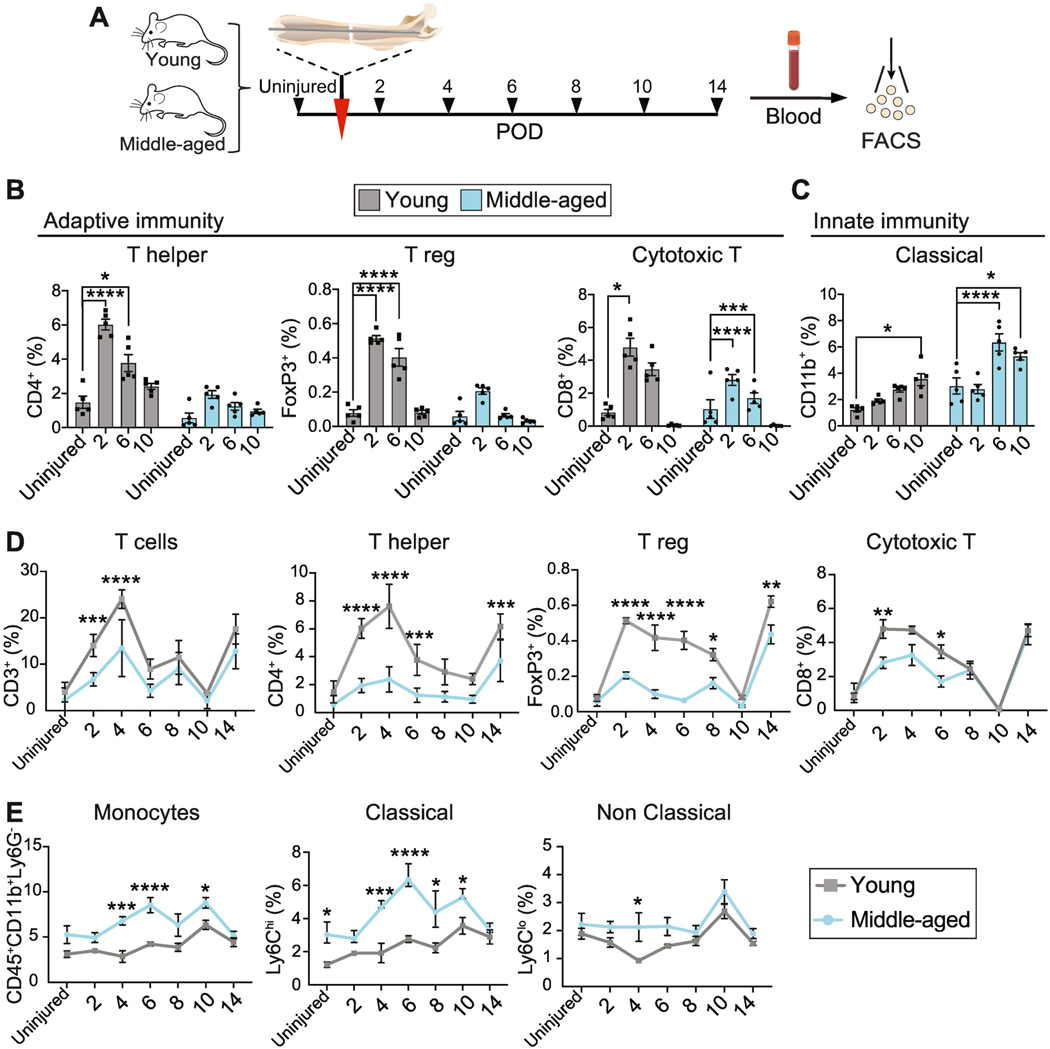

Fig. 2. Systemic immune response to long bone fracture.

(A) Experimental outline. Femoral fractures were performed on young and middle-aged mice (red arrowhead). Blood samples were taken at various intervals before and after injury (black arrowheads) for analysis of immune populations in the peripheral blood. (B-E) Summary of flow cytometry quantification of the percentage of different immune cell populations in young and middle-aged mice calculated as % of CD45+ cells. (B, C) Systemic mobilization of adaptive (B) and innate (C) immune cells after long bone fracture compared to systemic levels in the uninjured animal (young and middleaged). Each point represents an individual mouse. Data represented as mean +/− SEM. N =5. (D, E) Comparison of adaptive (D) and innate (E) immune cell number in young and aged animals at varying time points after fracture. Each point represents an individual mouse. Data represented as mean +/− SEM. N = 5. Abbreviation: FACS, fluorescent-activated cell sorting; POD, postoperative day; T reg, regulatory T cell. * p<0.05, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001, **** p<0.00001, unpaired t-test.

First, we assessed the dynamics of immune cell mobilization in young versus aging animals. In young mice, T cell frequency – in particular Thelper, Treg, and cytotoxic T cells – was elevated in response to injury (Fig. 2B, gray bars). We observed biphasic mobilization into the peripheral blood (reviewed in [10]) characterized by an early phase that peaked at day 2 after fracture, returned to baseline around post-injury day 10, but then increased again at day 14 (Fig. 2B, D), a time point corresponding to the transition from soft to hard callus (Fig. 1B). In contrast, middleaged mice showed no significant increase in the proportion of Thelper or Treg cells upon injury (Fig. 1B, blue bars), indicating that the early mobilization after fracture did not occur (Fig. 2B, blue bars). Moreover, the proportion of Thelper and Treg cells was consistently reduced at almost every time point after fracture in middle-aged compared to young mice (Fig. 2D). While cytotoxic T cells exhibited typical early dynamics in middle-aged mice, their fraction was also reduced compared to young animals from day 2 to 6 after fracture, after which they normalized to values similar to the young (Fig. 2D).

Monocytes, the most highly represented innate immune cell type in peripheral blood, exhibited a different mobilization pattern. Classical monocytes critical for the early inflammatory response to injury and infection, while non-classical monocytes are typically viewed as anti-inflammatory [11]. Following the femoral fracture, the number of peripheral classical monocytes (CD45+CD11b+Ly6Chigh) steadily increased over time in young animals, reaching a peak at day 10 after injury (Fig. 1C, gray bars). Instead, middle-aged mice exhibited more rapid and robust monocyte mobilization with a peak at post-injury day 6 (Fig. 2C, blue bars). Classical monocytes were elevated in middle-aged versus young mice both before and after injury (Fig. 1E). However, we observed little difference in the dynamics of nonclassical monocytes (Fig. 1E), except for a blunted decline in the middle-aged mice at post-injury day 4. Thus far, these data suggest a less pronounced adaptive immune cell mobilization in aging animals in response to bone injury, while the systemic mobilization of innate immune cells, in particular the ones considered pro-inflammatory, was increased.

Together these data show that local tissue trauma after fracture elicits a systemic inflammatory response with circulating immune traits that are altered with age. Notably, we demonstrate an inverse relationship between circulating monocytic and lymphocyte kinetics in the blood of middle-aged animals following fracture.

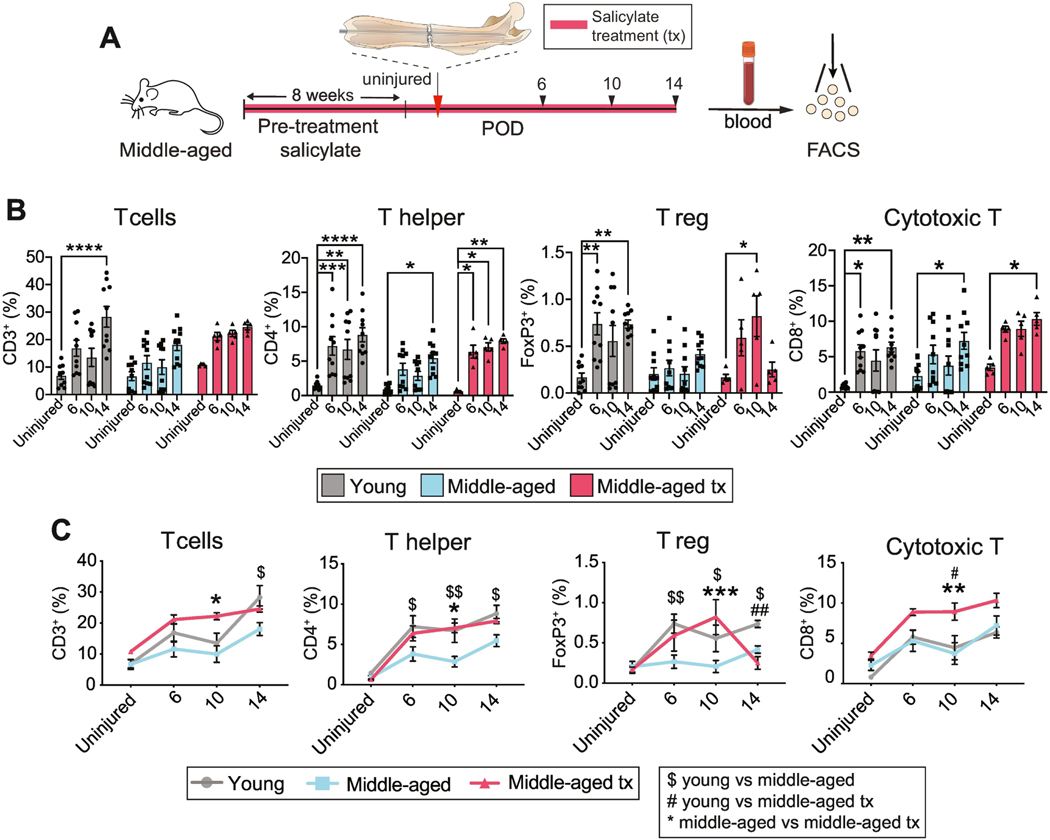

Salicylate treatment in aged animals restores circulating T cell phenotype

Thus far we present evidence that with aging, there is a decline in the regenerative capacity of the skeleton that can be restored by treatment with an anti-inflammatory drug (Fig. 1). Additionally, we found that this decline is accompanied by a change in post-traumatic systemic immune cell mobilization (Fig. 2). We now asked to determine whether the rescue of fracture healing efficiency in aging mice by sodium salicylate treatment is accompanied by a T cell activation kinetic that mimics that of young mice. We focused on T cell activation rather than the monocytic response due to the relative gap in knowledge about the role of the adaptive immunity in fracture healing. We analyzed the blood of young and middle-aged mice, and middle-aged mice after salicylate treatment for circulating T cells at 6, 10 and 14 days after fracture (Fig. 3A). We had previously shown that middle-aged mice were unable to initiate an early Thelper and Treg response to fracture (Fig. 2B). Similarly, here we observed that Thelper, Treg and cytotoxic T cells were significantly elevated in young mice from post-injury day 6 while, in middle-aged mice, there was no significant increase in Treg cells, and Thelper and cytotoxic T cells were only elevated at day 14 (Fig. 3B). Sodium salicylate treatment of middle-aged mice resulted in an increase in the proportion of all T cell populations, particularly at early time points, towards levels observed in the 12-week-old young mice (Fig. 3B, C). The cytotoxic T cell proportion increased in response to sodium salicylate treatment, even though there was no initial difference between the untreated young and middle-aged animals (Fig. 3B, C). These data demonstrate that treatment of middle-aged mice with sodium salicylate modulates the T cell profile in the peripheral blood to kinetics that are more similar to those in young animals.

Fig. 3. Anti-inflammatory treatment restores systemic immune cell mobilization.

(A) Experimental outline. Femoral fracture (red arrowhead) was performed on young, middle-aged, and middle-aged mice treated with the anti-inflammatory salicylate for 8 weeks. Blood samples were taken at various intervals (black arrowheads) before and after injury for analysis of immune populations in the peripheral blood. (B, C) Summary of flow cytometry quantification of the percentage of immune cell populations in young, middle-aged, and middle-aged salicylatetreated mice calculated as % of CD45+ cells. (B) Fracture-induced systemic mobilization of T cells, T helper cells, regulatory T cells and cytotoxic T cells in comparison to systemic levels observed in the uninjured animal (young and middle-aged). Each point represents an individual mouse. Data represented as mean +/− SEM. N = 5–10 (C) Direct comparison of adaptive immune cell number of young, middle-aged and middle-aged treated animals at distinct time points after fracture. Each point represents an individual mouse. Data represented as mean +/− SEM. N = 510 * p<0.05, ** p<0.001, *** p<0.0001, **** p<0.00001, unpaired t-test. Significance annotation in panel (C) $ = young vs middle-aged; # = young vs middle-aged treated; * = middle-aged vs middle-aged treated. Abbreviation: FACS, fluorescent-activated cell sorting; POD, post-operative day; T reg, regulatory T cell; tx, treated.

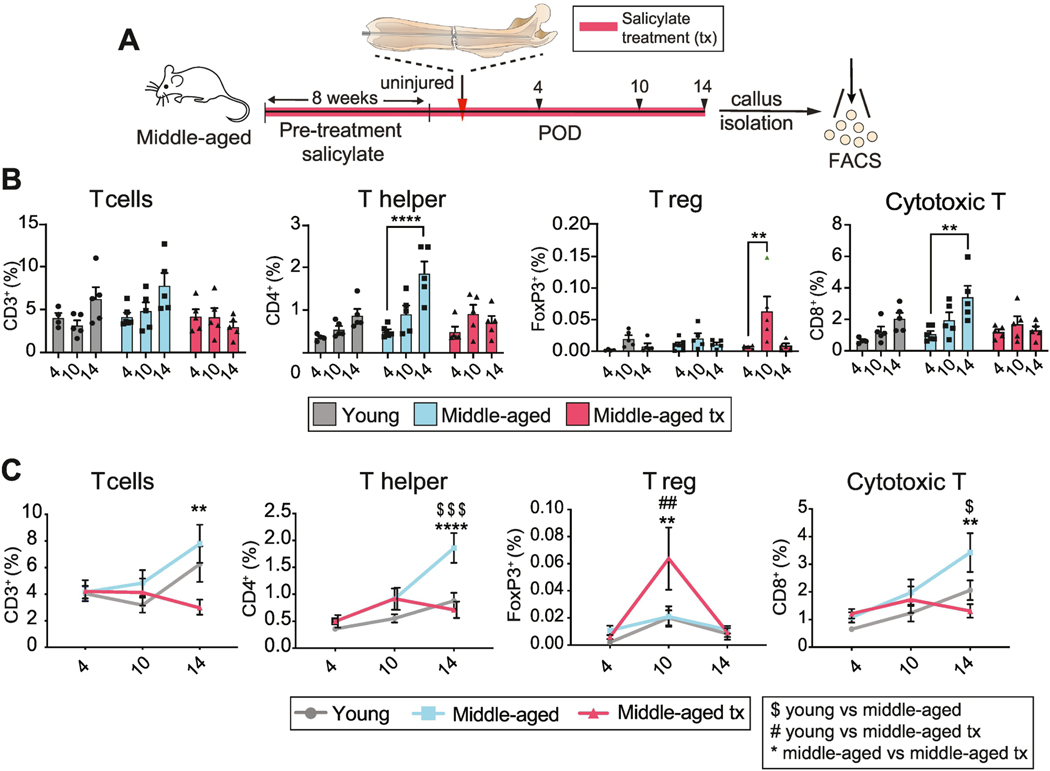

Increased Thelper and cytotoxic T cell recruitment into fracture callus in middle-aged animals.

A change in the systemic T cell profile could regulate the local inflammatory milieu of the fracture site through secreted factors. Alternatively, the systemic mobilization of T cells might trigger a local increase in T cell number within the fracture callus, which then affects healing. To distinguish between these possibilities, we analyzed the T cell populations present within the isolated fracture callus from young, middle-aged, middle-aged salicylate treated mice. While young mice showed a robust systemic increase in T cells in response to injury (Fig. 2), there was only a modest increase in Thelper and cytotoxic T cells within the callus (Fig. 4). Furthermore, while the mobilization of systemic T cells was reduced in middle-aged versus young mice (Fig. 2), total T cell, Thelper, Treg and cytotoxic T cell proportions were similar within the callus of young and middle-aged mice at day 4 and 10 after injury. At day 14, Thelper and cytotoxic T cells were significantly more abundant in the middle-aged mice (Fig. 4B, C). At this stage of fracture healing, sodium salicylate treatment resulted in a suppression of local Thelper and cytotoxic T cell recruitment, a reversal of the middle-aged phenotype, while increasing the fraction of Treg cells in the fracture callus at day 10 after fracture (Fig. 4B, C). Thus, aging alters the systemic and local T cell response to musculoskeletal trauma and anti-inflammatory drug treatment can reverse these changes, coincident with improved fracture healing.

Fig. 4. Local T cell environment in young and middle-aged fracture callus.

(A) Experimental outline. Femoral fracture (red arrowhead) was performed on young, middle-aged, and middle-aged mice treated with the anti-inflammatory sodium salicylate for 8 weeks. Cells were isolated from the callus at POD 4, 10 and 14 (black arrowheads) for analysis of immune populations. (B) Temporal comparison of T cell, Thelper, Treg, cytotoxic T cell recruitment analyzed by FACS of the fracture callus of young, middle-aged and middle-aged salicylate-treated mice. Only Thelper and cytotoxic T cell recruitment in middle-aged mice matches the T cell dynamics observed in the peripheral blood. Each point represents an individual mouse. Data represented as mean +/− SEM. N = 5. (C) Direct comparison of the frequency of T cells, Thelper, Treg, cytotoxic T cells reveals that salicylate treatment of middle-aged mice leads to a reduction of Thelper and cytotoxic T cell recruitment to levels observed in the young animals. Treg recruitment is increased at postoperative day 10 in animals receiving salicylate treatment. Each point represents an individual mouse. Data represented as mean +/− SEM. N = 5. ** p<0.001, **** p<0.00001, unpaired t-test. Significance annotation in panel (C) $ = young vs middle-aged; # = young vs middle-aged treated; * = middle-aged vs middle-aged treated. Abbreviation: FACS, fluorescent-activated cell sorting; POD, post-operative day; T reg, regulatory T cell; tx; treated.

The immune adaptor protein MyD88 accumulates in aged callus and decreases after salicylate treatment

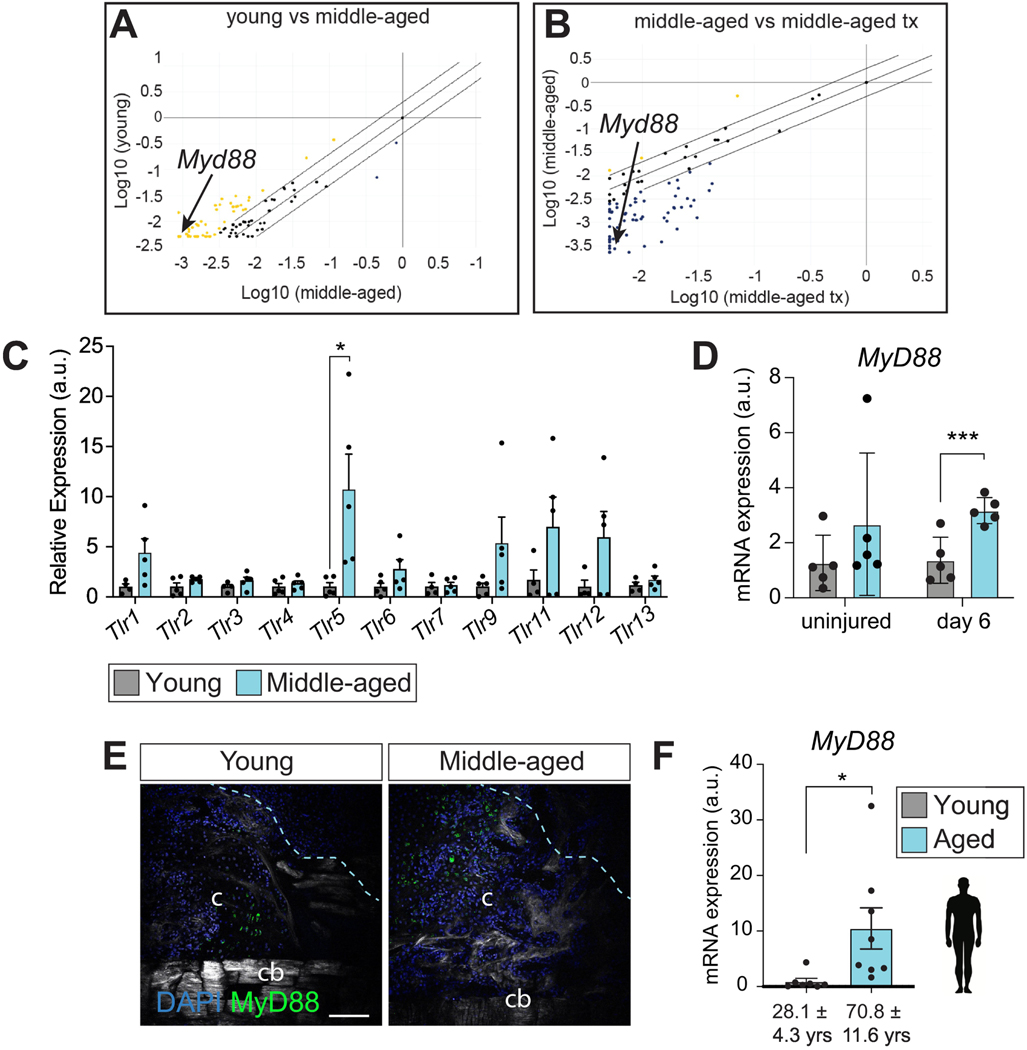

To understand the mechanism of action by which anti-inflammatory drugs improve the anabolic bone healing response, we profiled the fracture callus transcriptome from young, middle-aged and middle-aged salicylate-treated fracture callus at 14 days after fracture when downstream transcriptional effects in response to the anti-inflammatory treatment should be evident. We used a RT2 Profiler PCR Array designed to probe the expression of inflammatory genes and associated signaling pathways. In total, we profiled 84 genes related to inflammation in mice. Transcriptional analysis revealed significant differences in a plethora of genes, as demonstrated by scatter plots of young vs middle-aged and middle-aged vs middle-aged-treated samples (Fig. 5A). As expected, inflammatory genes were largely downregulated in young compared to middle-aged fracture callus (51/84 genes, Fig. 5A, yellow dots), while sodium salicylate treatment resulted in a down-regulation of the majority of genes analyzed (61/84 genes,Fig. 5B, blue dots). In-depth analysis revealed that the transcriptional message for multiple Toll-Like Receptors (TLR) was upregulated in the middle-aged callus and conversely down-regulated after sodium salicylate treatment (Suppl. Fig. S1). We confirmed this result by qRT-PCR, finding that Tlr5 exhibits the most robust increase in expression with age (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5. Aging leads to increased toll-like receptor signaling in fracture callus.

(A) RT2 profiler analysis indicating upregulated genes (yellow dots) in the fracture callus of middle-aged mice compared to young mice and (B) downregulated genes (blue) in sodium salicylate treated middle-aged mice compared to untreated middle-aged mice. The adaptor protein Myd88 is identified with arrow. (C) qRT-PCR data showing the gene expression levels of TLR family members in young and middle-aged fracture callus 14 days after femur fracture. Each point represents an individual mouse (n = 5). Data shown relative to the mean expression level in young mice and represented as mean +/− SEM. (D) Myd88 expression is similar in uninjured bone marrow from young and middle-aged mice. After injury, Myd88 expression is significantly higher in middle-aged mice at post-operative day 6. (E) Myd88 immunofluorescence staining of the callus around the fracture site (within light-blue dashed line) reveals abundance on Myd88positive cells in the middle-aged fracture callus at post-operative day 14. (F) Human Myd88 expression in fracture callus obtained from young and aged patients. * p<0.05, *** p<0.0001, unpaired t-test. Abbreviation: c, callus; cb, cortical bone; tx, treatment.

TLRs play a critical role in the recognition of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which stimulates a regenerative response to trauma [12]. After recognition of DAMPs, TLRs signal through the adaptor protein Myd88, resulting in the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines that trigger immune cell recruitment [13]. To investigate the role of Tlr signaling in the aging response to injury and, due to the central role of MyD88 in this process, we next analyzed the callus of young and middle-aged mice for MyD88 expression. We found a significant increase in MyD88 expression at day 6 after injury (Fig. 5D). We confirmed by immunofluorescence staining that MYD88 protein was also elevated in middle-aged animals at day 14 after fracture (Fig. 5E). Finally, to determine the clinical relevance of the TLR/MyD88 axis, we also measured Myd88 expression levels in young (28.1 ± 4.3 years-old) and aged (70.8 ± 11.6 years-old) human fracture patients and similarly observed a significant upregulation of MyD88 in aged versus young callus samples (Fig. 5F). Together these results reveal that TLRs, and the downstream pathway component, MyD88, are upregulated in mouse and human middleaged versus young fractured bones that are refractory to bone repair and healing.

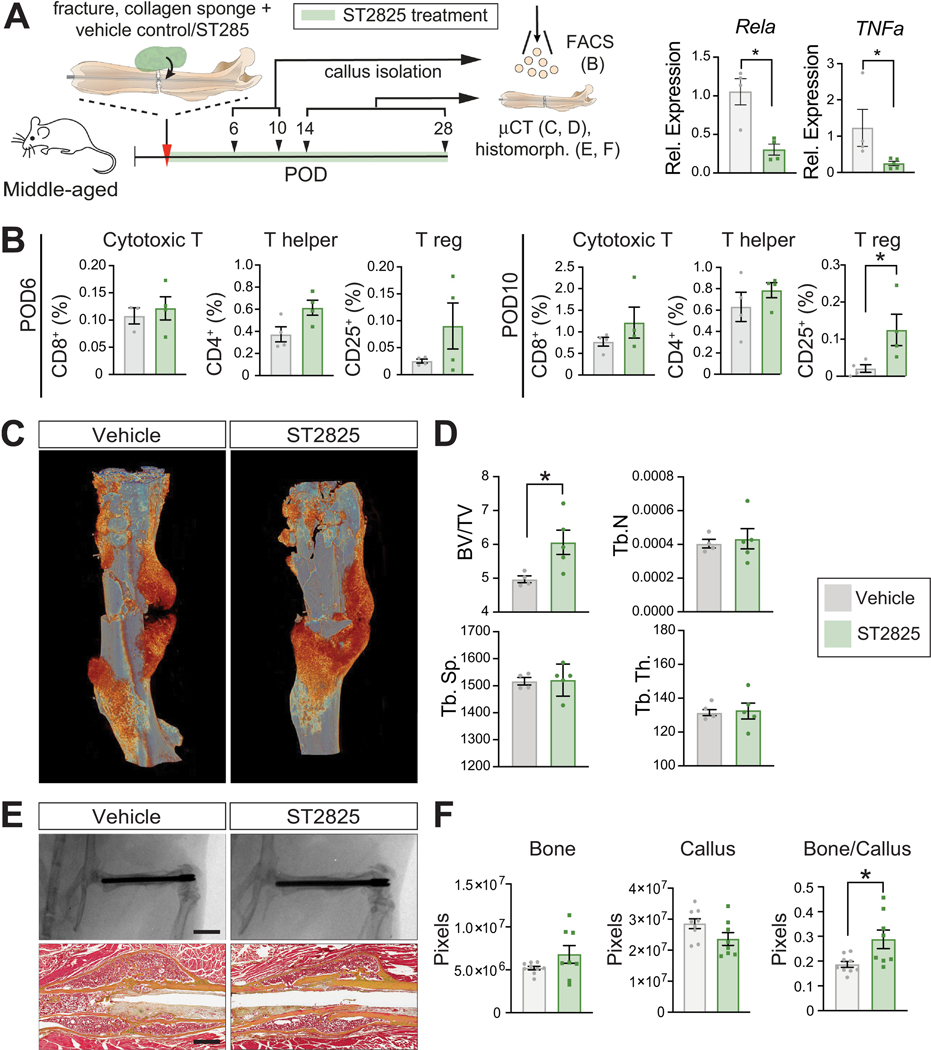

Local inhibition of MyD88 accelerates fracture healing in middle-aged mice

Based on our results demonstrating that Myd88 is upregulated in aged animals and patients, and that it can be modulated by salicylate treatment, we investigated whether the direct suppression of Myd88 activity alone could improve the healing process in middle-aged animals. To this end, we locally delivered a small molecule inhibitor of MYD88, ST2825, using a collagen sponge as a carrier (Fig. 6A). ST2825 inhibits MyD88 dimerization, which hinders the pathway activation downstream of the TLRs, which culminates in the activation of NF-κB (RelA) [14] (Fig. 6A). First, callus tissue was analysed by FACS at day 6 and 10 and revealed a significant increase of the Treg fraction at day 10, with a similar trend observed at day 6 (Fig. 6B). This increase was consistent with that observed after sodium salicylate treatment (Fig. 4B). Cytotoxic T cell and Thelper cell proportions were not affected by the local MyD88 inhibitor treatment (Fig. 6B). μCT analysis at post-operative day 14 revealed a significantly increased bone volume in the fractures treated with the MyD88 inhibitor (Fig. 6C, D). Radiographs and Pentachrome histology of fractured bones revealed a mature-appearing callus with smooth cortical margins and remodeled woven bone in the control and MyD88 inhibitor group (Fig. 6E), and histomorphometric analysis revealed that at 28 days post injury, the ST2825 treated, middle-aged samples showed an increase in new bone formation, a decrease of callus volume and a significant increase of the bone/callus volume ratio compared to the control femur fractures (Fig. 6F). These results demonstrate that the inhibition of MyD88, either indirectly through sodium salicylate treatment or directly through inhibition using ST2825, leads to an increase in the local Treg number and simultaneously improves fracture healing in middle-aged animals. Our observation that MyD88 is also upregulated in aged versus young human fracture callus pinpoints MyD88 and the TLR pathway as promising therapeutic targets to improve fracture healing in elderly patients.

Figure 6. Myd88 inhibition improves fracture healing in the middle-aged animals.

(A) Middle-aged mice were subjected to femoral fracture. Vehicle control (DMSO and corn oil) or 20 μg of ST2825 were loaded in a collagen sponge and placed under the muscle surrounding the femur fracture at the time of the surgery. Callus samples were collected at post-operative day (POD) 6 and 10 for flow cytometry analysis of immune populations (B) and at post-operative day 14 for μCT (C, D) and post-operative day 28 for histomorphometric analysis (E, F). Expression levels of RelA and TNFα in T cells analyzed at post-operative day 14 confirming Myd88 downstream inhibition in fractures treated with the MyD88 inhibitor ST2825. (B) FACS analysis of callus tissue at post-operative day 6 and 10 for cytotoxic T cells, Thelper and Treg cells in middle-aged mice. Green bars represent the samples treated with the MyD88 inhibitor ST2825. Each point represents an individual mouse. Data represented as mean +/− SEM. N = 4. (C) Representative 3D reconstruction of femur fractures treated with vehicle control or MyD88 inhibitor at post-operative day 14. (D) μCT histomorphometry revealing increase bone volume in the callus of mice treated with the MyD88 inhibitor at post-operative 14. (E) Representative radiographs (scale bar 4 mm) and Movat’s Pentachrome histology (scale bar 500 μm) of femur fractures treated with ST2825 or control (POD 28). Yellow = bone. Green = cartilage. Red = muscle. (F) Histomorphometric measurements of the callus performed on serial histologic sections reveals increased bone formation in the callus in middle-aged mice treated with the Myd88 inhibitor. Each point represents an individual mouse. Data represented as mean +/− SEM. N = 8. * p<0.05, unpaired t-test.

Discussion

The physiological processes occurring during fracture repair have been extensively studied [15] but the molecular mechanisms that trigger the decline in regeneration efficacy in the geriatric population are not well understood [16]. Inflammaging has been identified as the main culprit driving regenerative failure and treating aged animals with the anti-inflammatory drug sodium salicylate effectively modulated the systemic and local immune response coincident with improved bone healing in middle-aged mice. However, as inflammation also plays an important role in fracture repair [15], more targeted strategies will be necessary to mitigate the negative effects of inflammaging in tandem with optimizing bone healing. To begin to address this, we precisely characterized the systemic and local immune responses upon injury in young versus aged animals and identified Myd88 as a critical immuno-modulatory adaptor that coordinates inflammation and bone repair during aging. Notably, suppressing signaling through MyD88 restored the delayed bone repair observed in aging mice, uncovering a new potential therapeutic strategy to improve fracture treatment in elderly patients.

MyD88 serves as a critical adaptor protein in TLR signaling cascade, resulting in the downstream induction of NF-κB-dependent transcription of inflammatory cytokines [17]. TLRs recognize DAMPs, also known as alarmins, which are released at the site of tissue injury [18]. TLR-activation regulates the innate and adaptive immune response after injury, and therefore TLRs are prime candidates to study and understand the age-associated mechanistic changes observed in the acute inflammatory response after fracture. In our study, we revealed an increased expression of TLRs in aged fracture callus and we identified a prolonged and increased recruitment of CD4+ T helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells into the fracture callus, coinciding with an increased expression of the adaptor protein MyD88 within the cells comprising the early fracture regenerate. Based on existing evidence, prolonged inflammation can often result in delayed wound healing [19–21], and therefore our observation of increased TLR-signaling through MyD88 and subsequent T cell recruitment may be one of the culprits for impaired fracture healing in the elderly. This hypothesis is supported by our finding that local inhibition of MyD88 at the fracture site resulted in improved bone regeneration. Further analysis revealed that MyD88 inhibition resulted in an increase of the Treg population within the callus. Treg cells act to suppress the immune response by inhibiting T cell proliferation and cytokine production [22], and hence the increase in Treg number may mediate an anti-inflammatory effect that counteracts the pro-inflammatory environment caused by the abundance of CD4+ Thelper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in the aged fracture callus. This is further supported by the observation that sodium salicylate treatment, which also improved bone healing in middle-aged animals, elevated the Treg population around post-operative day 10 within the callus, similar to what we demonstrated in the MyD88 inhibitor-treated fracture callus. However, future studies will be necessary to shed light on the specific mechanism and cell populations within the bone that are affected by MyD88 inhibition.

The immune response to injury is complex and involves both the innate and the adaptive immunity [23, 24]. Communication between the two systems is accomplished through secretion of inflammatory cytokines at the site of injury. As described above, the activation of TLRsignaling leads to a downstream activation of NF-κB, which in turn results in TNF-α, Il-1, Il-6, Il-8 and Il-12 [25, 26]. All of these cytokines directly affect innate immune cell recruitment and activation. In addition, Treg cells play a critical role in controlling the magnitude of the immune response as they regulate the activation of the innate immune cell populations [27]. Cytokine production by T cells can stimulate, inactivate or polarize macrophages within the injury site [28]. Our analysis of the injury-induced systemic monocyte recruitment revealed significantly elevated numbers of classical, Ly6Chi, monocytes during the first 10 days after fracture (Fig. 2E). At the same time we observed a significant reduction in the systemic number of Treg cells, resulting in an overall prolonged pro-inflammatory systemic environment in the middle-aged animals. Whether this decline in Treg cells in middle-aged mice is a result of increased TLR signaling or a consequence of T-cell anergy – hyporesponsive T-cells that results in insufficient activation [29] – or an exhaustion of the Treg phenotype, decreased proliferation or loss of cytokine secretion [30] is to be further analyzed. Nevertheless, this phenomenon could explain the sustained pro-inflammatory environment observed in middle-aged mice, which ultimately impairs the resolution of innate system activity and thus delays fracture healing in middle-aged animals.

In summary, this study reveals a profound association between the systemic immune cell kinetics and fracture healing, and provides the first evidence of how dysregulation of the immune response to fracture in the aging animal can be ameliorated by modulating the TLR pathway.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Studies were conducted on 12 week-old (young) C57BL/6 male mice (Jax no. 000664) purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and on 52-week-old (aging) C57BL/6 male mice (Mus musculus) from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). Mice were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with food and water provided ad libitum, in accordance with the guidelines of NYU Robert I. Grossman School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Femur fracture model and salicylate treatment

All procedures followed protocols approved by the NYU Robert I. Grossman School of Medicine IACUC (IA17–01463). Mice were anesthetized using Isoflurane inhalation. A 4-mm incision was made over the anterolateral femoral hindlimb. The quadriceps femoris muscle was elevated to expose the lateral femur. Next, the femur was transected in the mid-diaphysis with small surgical scissors, and a screw of 1 mm diameter was inserted into the medullary canal to stabilize the fracture. Incisions were closed with 5–0 Vicryl sutures. Before and after surgery, mice received subcutaneous injections of buprenorphine for analgesia and were allowed to ambulate freely.

Animals that were randomized to the salicylate treatment group received either an 8-week course of sodium salicylate (treated animals). Control mice were kept on regular drinking water before the surgery. The treatment was continued through the healing course, until the animals were euthanized at the selected time points for the histology, histomorphometry and micro-CT analysis.

μCT analyses

Femurs were scanned using a high-resolution SkyScan µCT system (SkyScan 1172, Bruker, Billerica, MA). Images were acquired at 9 μm isotropic resolution using a 10MP digital detector, 10W energy (100 kV and 100A), and a 0.5 mm aluminum filter with a 9.7 μm image voxel size. A fixed global threshold method was used based on the manufacturer’s recommendations and preliminary studies showed that mineral variation between groups was not high enough to warrant adaptive thresholding. The samples were oriented and the volume of interest (VOI) defined with the CTAn software (Bruker). The VOI was contoured manually to capture the entire callus region. The parameters selected to show variations between groups were total bone volume (BV), total tissue volume (TV), respective mineralized volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th) and trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp) following the guidelines described by Bouxsein et al. [31].

Isolation of immune cells from callus

Callus tissue from femur fractures was harvested and processed as previously described in Gulati et al. 2018 [32] with slight variations. A 7-mm section of callus tissue was excised and crushed once, using mortar and pestle, and then cut in small pieces with scissors. Then, the tissue was subjected to three enzymatic digestion with 0.2% collagenase at 37°C under agitation for 30 minutes each [32]. Cells were filtered through a 70-μm strainer and pelleted at 300 g at 4°C. Red blood cells were lysed using NH4Cl (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) for 5 min, washed with PBS+1%BSA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA and Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and pelleted. The pelleted cells were used for the flow cytometry analysis or sorting.

Flow cytometry and Sorting

Blood samples and dissociated cell samples from the callus, were staining with two different antibody combinations to detect the innate and adaptive immune populations respectively (Table 1). Fc receptors were blocked to avoid an unspecific binding of antibodies to the Fc domain. Next, samples were stained with the specific mix of antibodies for 40 min at rt in the dark. This was followed by two washing steps. Finally cells were fixed for 30 min at 4 °C. For the intracellular Treg staining, a Foxp3 Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions. Staining with Zombie Aqua™ (Biolegend) was used for the detection of dead cells and isotype controls with beads and fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls were used to gate for background staining.

Table 1.

Antibodies for flow cytometry

| Antibodies | Clone | Company | Dilution | Immune System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APC/Cy7 anti-mouse CD45.2 Antibody | REA737 | Miltenyi | 1:100 | Innate/Adaptive |

| Anti-Ly6C-PE | REA796 | Miltenyi | 1:100 | Innate |

| Anti-Ly6G-Vioblue | REA526 | Miltenyi | 1:100 | Innate |

| Anti-MHC Class II-PerCP-Vio700 | M5/114.15.2 | Miltenyi | 1:100 | Innate |

| CD11b-APC | REA592 | Miltenyi | 1:100 | Innate |

| CD11c-FITC | REA754 | Miltenyi | 1:100 | Innate |

| F4/80-PE-Vio 770 | REA126 | Miltenyi | 1:100 | Innate |

| CD206-PE-Dazzel 594 | Biolegend | 1:100 | Innate | |

| PE-Cy™7 Rat Anti-Mouse CD3 Molecular Complex | BD | 1:100 | Adaptive | |

| PE-CF594 Rat Anti-Mouse CD4 | RM4–5 (RUO) | BD | 1:100 | Adaptive |

| CD8b.2-FITC | Miltenyi | 1:100 | Adaptive | |

| Foxp3 Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Kit | Thermo Fisher | 1:100 | Adaptive |

After staining and fixation, samples were filtered through a 40um Fisherbrand™ Cell Strainers (Thermo Fisher Scientific), acquired on a BD LSRII UV flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and recorded using the FACSDiva software (BD). Acquired data were analyzed using the FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC). In all samples, the leukocyte population was used as gate reference. The gating strategy for the different populations are detailed in the Supplementary figure S2 and S3.

Histology

Femurs were dissected at the defined time points and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C. Bones were decalcified in 19% ethylenediaminetetraaceticacid (EDTA) for 3 weeks at 4°C. Decalcified samples were embedded into paraffin, and cut into 10-μm-thick sections. Movat’s Pentachrome staining was used to detect osseous and cartilage tissues as previously described [33–36].

For histomorphometric measurements, Movat’s Pentachrome staining sections were photographed using ultra-compact Aperio CS2 system (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The resulting digital images (at least 3 different area per sample) were analyzed with Adobe Photoshop CC 2017 software. We chose a fixed, rectangular ROI for all samples. Cortical surfaces, or bone fragments resulting from the injury, were manually deselected. Pixel counts from individual sections were averaged for each sample, and the differences within and among treatment groups were calculated on the basis of these averages.

Femurs analyzed using immunofluorescence were dissected at day 14 and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C. After fixation the femurs were embedded in 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C and at −80 °C until the day before sectioning. The day before sectioning, samples were embedded in OCT and cryosectioned according to Kawamoto’s tape method [37]. Immunostaining for MyD88 was performed on cryosections of the callus after thaw and permeabilization with 0.05% Triton-X in PBS for 10 min at RT. Sections were blocked in PBS with 1% BSA for 30 min. Primary Rabbit anti-MyD88 (1:250; Sigma-Aldrich) was applied overnight at 4°C, followed by Alexa Fluor™ 488 Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (1:500; Invitrogen) 1-h incubation. After washing, the samples were stained with DAPI (1:1000, ThermoFisher).

μCT analyses

Samples were scanned using a high-resolution Skyscan μCT system (SkyScan 1172, Bruker, Billerica, MA). Images were acquired at 9 μm isotropic resolution using a 10MP digital detector, 10W energy (100 kV and 100A), and a 0.5 mm aluminum filter with a 9.7 μm image voxel size. A fixed global threshold method was used based on the manufacturer’s recommendations and preliminary studies, which showed that mineral variation between groups was not high enough to warrant adaptive thresholding. The following parameters were analyzed: total bone volume (BV), total tissue volume (TV), respective mineralized volume fraction (BV/TV). The volume of interest (VOI) included a the entire callus with the fracture site centered. The VOI was cylindrical capturing the entire callus region and total volume (TV) represents the cylinder volume is therefore constant.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was isolated from either cells, callus [38] and human bone marrow using an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) according to manufacturer’s instruction. cDNA was synthesized using iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out using the Applied Biosystems Step One Plus detection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and RT2 SYBR Green ROX PCR Master Mix (Qiagen). Specific primers (Table 2) were designed using GETPrime 2.0 [39]. Results are presented as 2–ΔΔCt values normalized to the expression of 18S. Means and SEMs were calculated in GraphPad Prism 8 software.

Table 2.

PCR primers. All primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies

| Primer Name | Sequence (5’−3’) |

|---|---|

| Mouse | |

| mu_18S FOR | ACGAGACTCTGGCATGCTAACTAGT |

| mu_18S REV | CGCCACTTGTCCCTCTAAGAA |

| mu_MyD88 FOR | TCATGTTCTCCATACCCTTGGT |

| mu_MyD88 REV | AAACTGCGAGTGGGGTCAG |

| Human | |

| hu_18S FOR | CTCACTGAGGATGAGGTGG |

| hu_18S REV | GTTCAAGAACCAGTCTGGGA |

| hu_Myd88 FOR | CAGGAAACAGCTATGACGTTGTTAACCCTGGGGTTG |

| hu_Myd88 REV | TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTGCAGGGGTTGGTGTAGT |

Patients and specimens

All experiments involving human subjects were approved by the New York University Grossman School of Medicine institutional review board. After informed consent was obtained, specimens were obtained during surgical fixation of long bone fractures. 1cc of tissue at the fracture site that was debrided during the procedure was immediately transferred into a microcentrifuge tube and placed on ice. Samples were dissociated and then subjected to above mentioned RNA isolation. Patients were selected based on their age and an effort was made to identify relatively healthy patients with minimal number of comorbidities. The two groups were matched in regards to gender and general health status.

RT2 Profiler PCR Array

Callus transcriptomics were screened using pathway-focused gene expression analysis with an RT2 Profiler PCR Array for Mouse Inflammatory Response & Autoimmunity (PAMM-077ZA, Qiagen). Callus from 12-week-old, 52-week-old, and 52-week-old salicylate-treated mice was collected at different time points post-fracture and lysed with the QIAzol® Lysis Reagent (Qiagen) using a mortar and pestle. The lysis was followed by the RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis detailed previously.

The RT2 Profiler PCR Array contains a panel of 84 immune-related genes. RNA from middleaged calluses was compared to that of young calluses for each time point individually to yield a fold change in gene expression. Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA; Qiagen) was then used to identify pathways and predicted upstream regulators relevant to our dataset. A comparison analysis was then performed using the list of upstream regulators for each time point. The genes are ordered by their activation z-score (averaged over all time points in each comparison; only the magnitude was considered) from highest to lowest. A higher activation z-score indicates a higher potential to act as an upstream regulator of the inflammatory genes that are differentially expressed in aged vs. young animals.

ST2825 treatment

Aged (95-week-old) C57B/L6 mice underwent a femur fracture (n=6 per group). ST2825 purchased from MedchemExpress was dissolved in 10% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, Thermo Fisher) and 90% of corn oil (Sigma). 20 μg of ST2825 were administered per animal loaded in a collagen sponge at the time of the surgery. The sponge with the inhibitor was placed under the muscle surrounding the femur fracture. Animals were euthanized after 6, 10 and 28 days, cell isolation, FACS and histomorphometry was performed as described above.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean and SEMs. Statistical computational analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc) analysis. Power analysis (p=0.05, power 80%) predicted an n of 4 for each group after body-size adjustment, expecting a 25% difference between the groups. Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) was used for statistical computations. A student’s t test was used for all comparisons between two groups. For multiple comparisons, 2-way-ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was applied. Significance was set at p<0.05

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Aging SSPC function leads to impaired fracture healing

Increased TLR signaling during aging triggers abnormal immune cell recruitment

MyD88 inhibition restores the regenerative potential of the aging skeleton

Acknowledgments

We thank Gozde (Gina) Yildirim, MS, (NYU College of Dentistry) for assistance with the μCT imaging, funded through NIH Grant S10OD010751, the NYU Langone’s Microscopy Laboratory for the support with the immunofluorescence imaging and the NYU Langone’s Experimental Pathology Research Laboratory for providing the Kawamoto cryosections. We thank Lukasz Witek for performing histologic imaging with the Leica-Aperio Scanner. Cell sorting/flow cytometry technologies were provided by NYU Langone’s Cytometry and Cell Sorting Laboratory, which is supported in part by grant P30CA016087 from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute.

Funding: This work was supported by an R01AG056169 from the National Institute of Aging and a K08AR069099 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin. P.L. is also supported a gift from the Patricia and Frank Zarb Family.

Footnotes

Competing interests: No conflicts.

Data and materials availability: Requests for data and materials should be addressed to P.L.

Credit Author Statement

Emma Muiños Lopez - Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft, Kevin Leclerc - Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Malissa Ramsukh - Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Paulo Parente - Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Karan Patel - Formal analysis, Investigation, Carlos J. Aranda - Formal analysis, Investigation, Anna. M. Josephson - Formal analysis, Investigation, Lindsey H. Remark - Investigation, David J. Kirby - Investigation, Daniel Buchalter - Investigation, Tarik Hadi - Investigation, Sophie Morgani – Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization, Bhama Ramkhelawon - Writing – Review & Editing, Philipp Leucht – Visualization, Funding Acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – Original Draft, Resources

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Franceschi C, et al. , Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2000. 908: p. 244–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josephson AM, et al. , Age-related inflammation triggers skeletal stem/progenitor cell dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2019. 116(14): p. 6995–7004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark D, et al. , Age-related changes to macrophages are detrimental to fracture healing in mice. Aging Cell, 2020. 19(3): p. e13112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pajarinen J, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cell-macrophage crosstalk and bone healing. Biomaterials, 2019. 196: p. 80–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loffler J, et al. , Compromised Bone Healing in Aged Rats Is Associated With Impaired M2 Macrophage Function. Front Immunol, 2019. 10: p. 2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konnecke I, et al. , T and B cells participate in bone repair by infiltrating the fracture callus in a two-wave fashion. Bone, 2014. 64: p. 155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naik S, et al. , Inflammatory memory sensitizes skin epithelial stem cells to tissue damage. Nature, 2017. 550(7677): p. 475–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eming SA, Wynn TA, and Martin P, Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration. Science, 2017. 356(6342): p. 1026–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baht GS, Vi L, and Alman BA, The Role of the Immune Cells in Fracture Healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep, 2018. 16(2): p. 138–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bronte V and Pittet MJ, The spleen in local and systemic regulation of immunity. Immunity, 2013. 39(5): p. 806–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narasimhan PB, et al. , Nonclassical Monocytes in Health and Disease. Annu Rev Immunol, 2019. 37: p. 439–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anders HJ and Schaefer L, Beyond tissue injury-damage-associated molecular patterns, toll-like receptors, and inflammasomes also drive regeneration and fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2014. 25(7): p. 1387–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssens S and Beyaert R, A universal role for MyD88 in TLR/IL-1R-mediated signaling. Trends Biochem Sci, 2002. 27(9): p. 474–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiratori E, Itoh M, and Tohda S, MYD88 Inhibitor ST2825 Suppresses the Growth of Lymphoma and Leukaemia Cells. Anticancer Res, 2017. 37(11): p. 6203–6209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Einhorn TA and Gerstenfeld LC, Fracture healing: mechanisms and interventions. Nat Rev Rheumatol, 2015. 11(1): p. 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conboy IM and Rando TA, Aging, stem cells and tissue regeneration: lessons from muscle. Cell Cycle, 2005. 4(3): p. 407–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deguine J and Barton GM, MyD88: a central player in innate immune signaling. F1000Prime Rep, 2014. 6: p. 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piccinini AM and Midwood KS, DAMPening inflammation by modulating TLR signalling. Mediators Inflamm, 2010. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vannella KM and Wynn TA, Mechanisms of Organ Injury and Repair by Macrophages. Annu Rev Physiol, 2017. 79: p. 593–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vantucci CE, et al. , Development of systemic immune dysregulation in a rat trauma model of biomaterial-associated infection. Biomaterials, 2021. 264: p. 120405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng A, et al. , Early systemic immune biomarkers predict bone regeneration after trauma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2021. 118(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondelkova K, et al. , Regulatory T cells (TREG) and their roles in immune system with respect to immunopathological disorders. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove), 2010. 53(2): p. 73–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epelman S, Liu PP, and Mann DL, Role of innate and adaptive immune mechanisms in cardiac injury and repair. Nat Rev Immunol, 2015. 15(2): p. 117–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwasaki A and Medzhitov R, Regulation of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Science, 2010. 327(5963): p. 291–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akira S and Takeda K, Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol, 2004. 4(7): p. 499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O’Neill LA, Golenbock D, and Bowie AG, The history of Toll-like receptors - redefining innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol, 2013. 13(6): p. 453–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okeke EB and Uzonna JE, The Pivotal Role of Regulatory T Cells in the Regulation of Innate Immune Cells. Front Immunol, 2019. 10: p. 680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan T, et al. , CD4(+) T-cells are important in regulating macrophage polarization in C57BL/6 wild-type mice. Cell Immunol, 2011. 266(2): p. 180–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fathman CG and Lineberry NB, Molecular mechanisms of CD4+ T-cell anergy. Nat Rev Immunol, 2007. 7(8): p. 599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi JS, Cox MA, and Zajac AJ, T-cell exhaustion: characteristics, causes and conversion. Immunology, 2010. 129(4): p. 474–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouxsein ML, et al. , Guidelines for assessment of bone microstructure in rodents using micro-computed tomography. J Bone Miner Res, 2010. 25(7): p. 1468–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulati GS, et al. , Isolation and functional assessment of mouse skeletal stem cell lineage. Nat Protoc, 2018. 13(6): p. 1294–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leucht P, et al. , Embryonic origin and Hox status determine progenitor cell fate during adult bone regeneration. Development, 2008. 135(17): p. 2845–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leucht P, et al. , Accelerated bone repair after plasma laser corticotomies. Annals of surgery, 2007. 246(1): p. 140–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leucht P, et al. , Effect of mechanical stimuli on skeletal regeneration around implants. Bone, 2007. 40(4): p. 919–930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leucht P, et al. , FAK-Mediated mechanotransduction in skeletal regeneration. PLoS One, 2007. 2(4): p. e390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawamoto T, Use of a new adhesive film for the preparation of multi-purpose freshfrozen sections from hard tissues, whole-animals, insects and plants. Arch Histol Cytol, 2003. 66(2): p. 123–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelly NH, et al. , A method for isolating high quality RNA from mouse cortical and cancellous bone. Bone, 2014. 68: p. 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.David FP, Rougemont J, and Deplancke B, GETPrime 2.0: gene- and transcriptspecific qPCR primers for 13 species including polymorphisms. Nucleic Acids Res, 2017. 45(D1): p. D56–D60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.