Abstract

Three-dimensional (3D) printing technology has great potential for constructing structurally and functionally complex scaffold materials for tissue engineering. Bio-inks are a critical part of 3D printing for this purpose. In this study, based on dynamic hydrazone-crosslinked hyaluronic acid (HA-HYD) and photocrosslinked gelatin methacrylate (GelMA), a double-network (DN) hydrogel with significantly enhanced mechanical strength, self-healing, and shear-thinning properties was developed as a printable hydrogel bio-ink for extrusion-based 3D printing. Owing to shear thinning, the DN hydrogel bio-inks could be extruded to form uniform filaments, which were printed layer by layer to fabricate the scaffolds. The self-healing performance of the filaments and photocrosslinking of GelMA worked together to obtain an integrated and stable printed structure with high mechanical strength. The in vitro cytocompatibility assay showed that the DN hydrogel printed scaffolds supported the survival and proliferation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. GelMA/HA-HYD DN hydrogel bio-inks with printability, good structural integrity, and biocompatibility are promising materials for 3D printing of tissue engineering scaffolds.

1. Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) scaffold biomaterials play an important role in tissue engineering because they provide a suitable cellular microenvironment to facilitate tissue formation and promote regenerative processes.1,2 3D printing technology can customize a scaffold according to the desired composition and morphology, reproduce the heterogeneity of the original tissue, and allow mechanical adjustability, providing new technology and methods for fabricating scaffolds.3 Bio-inks are a critical component of 3D printing; they facilitate the printing of biomaterials with adjustable properties and may contain cells, growth factors, and drugs for various biomedical applications.4

Hydrogels are three-dimensional network structures formed by the crosslinking of hydrophilic polymers. They have unique characteristics similar to the natural extracellular matrix (ECM)—a high water content, biodegradability, and good biocompatibility. They also have a wide range of adjustable physical and chemical properties and good permeability to oxygen and nutrients, making them very suitable for cell growth.5−8 Hydrogels have been applied in extrusion-based 3D printing as bio-inks.9 Generally, hydrogels used as bio-inks for 3D printing scaffolds need to have the following characteristics: printability, high structural integrity, and biocompatibility.4 The printability of the hydrogel bio-inks depends on their shear thinning during printing and rapid recovery to a gel after printing. During printing, the hydrogel bio-ink needs to have a sufficiently low viscosity to facilitate extrusion. After extrusion, its viscosity should increase to form a uniform and stable hydrogel, as the printed filaments deposit on the receiving plate and proceed to rapid gelation during deposition.10,11 Meanwhile, the filaments should possess appropriate mechanical integrity to support themselves and maintain the structure of the printed scaffold.12,13 As 3D printed scaffolds for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, they should also have good biocompatibility and support cell viability and tissue growth.14,15

Many methacrylate polymers have been used to design hydrogel bio-inks, which can rapidly photocrosslink to form gels induced by a photoinitiator.16 However, covalent photocrosslinking typically impedes processability and needs to be controlled to prevent blocking of the printing nozzle. Therefore, reversible crosslinks such as dynamic covalent bonds,17 ionic interactions,18 supramolecular interactions,19,20 and hydrogen bonds21 are of interest, as these reversible interactions generally possess shear-thinning and self-healing properties.22 During extrusion, these dynamic hydrogels undergo a gel–sol transition, and after extrusion, the crosslinks recombine to renew the network.23 A double-network hydrogel (DN hydrogel) is composed of two interpenetrating networks and typically shows an enhanced/optimal mechanical strength at a certain ratio of the two networks as well as diversity in chemical composition.24,25 Applying DN hydrogels in 3D printing has led to impressive results, meeting the requirements for 3D printing hydrogel bio-inks.26 Within the category of dynamic/static crosslinking DN hydrogels, one strategy is to combine static covalent crosslinks with dynamic covalent crosslinks, which makes use of reversible dynamic covalent crosslinks as the energy dissipation mechanism to improve the printability and enhance toughness. The second static crosslinking can be used to reinforce the structure after printing or to regulate the viscosity before printing.11,27,28

We employed a dynamic/photocrosslinking strategy to develop a DN hydrogel bio-ink. Two natural biomaterials, gelatin and hyaluronic acid (HA), were used to prepare the bio-ink for 3D printing tissue engineering scaffolds. Gelatin is a denatured collagen with good biocompatibility and low antigenicity and contains many natural molecular epitopes for cell adhesion and signal transduction, which are important for maintaining the cell phenotype.29,30 HA is an important component of the ECM and has biocompatibility, biodegradability, low immunogenicity, and hydrophilicity.31,32 The amino- and aldehyde-modified HA forms a dynamic crosslinking network through the hydrazone,33 and gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) forms a static crosslinking network by photocrosslinking. In this study, a dynamic/photocrosslinking gelatin-HA DN hydrogel was prepared by blending amino- and aldehyde-modified HA with GelMA, with hydrazone-crosslinked HA as the dynamic network and photocrosslinked GelMA as the second static network. When this DN hydrogel was applied for bio-inks in 3D extrusion printing, the HA network through dynamic hydrazone crosslinking is shear-thinning and self-healing, of which the former improves the printability while the latter is due to the formation of dynamic covalent bonds between the printed structure layers to make the entire structure more stable and firm. After extrusion, the GelMA is photocrosslinked to reinforce the entire DN hydrogel printed scaffold and enhance its mechanical properties. Different DN hydrogel bio-ink formulations with different ratios of GelMA/hydrazone-crosslinked HA were evaluated for their printability, and the structure and mechanical properties of the printed scaffolds were investigated. Finally, we assessed the cytotoxicity of DN hydrogel printed scaffolds to examine their potential as a prospective material for tissue engineering.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Gelatin methacrylate (GelMA, EFL-GM-60), lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP), and a blue-violet light source (3 W, 405 nm) were obtained from the Suzhou Intelligent Manufacturing Research Institute, China. Hyaluronic acid (HA, MW of 90 kDa) was purchased from Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Dalian, China). Sodium hyaluronate (HA, MW of 310 kDa) was obtained from Huaxi Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Jinan, China). Sodium periodate, adipic acid dihydrazide (ADH), 1-ethyl-3-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl] carbodiimide (EDC), and hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT) were purchased from Macklin, Inc. (Shanghai, China). A LIVE/DEAD cell viability/toxicity kit was obtained from Life Technologies (USA). TRITC phalloidin, 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), CCK-8 cell proliferation, and a cytotoxicity assay kit (CCK-8) were purchased from Solarbio Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

2.2. OHA and HA-ADH Synthesis and Characterization

Two hundred milligrams of sodium hyaluronate (HA, MW of 310 kDa) was dissolved in 20 mL of dH2O, and 103 mg of sodium periodate (1:1 periodate/HA molar ratio) was added to 20 mL of the HA solution. The oxidation reaction was carried out for 2 h in the dark. Ethylene glycol (2 mL) was added and reacted for 30 min to terminate the reaction. The solution was dialyzed for 3 days against dH2O (molecular weight cutoff = 8000–14,000 Da), filtered with a 0.22 μm filter membrane, and then freeze-dried to obtain solid oxidized HA (OHA). OHA was characterized using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, NICOLET 10, Thermo), and the spectra were recorded in the absorbance mode from 4000 to 600 cm–1 for 32 scans at a 4 cm–1 resolution.34

HA (200 mg, MW of 90 kDa) was dissolved in 40 mL of dH2O, and 2.6 g of ADH was added to the HA solution. EDC (0.31 g) and 0.306 g of HOBT were dissolved in 40 mL of DMSO and added slowly dropwise to the HA solution. The pH of the reaction was adjusted to 6.8 every 30 min for 4 h, and the reaction continued for 24 h. The solution was dialyzed for 7 days against dH2O (molecular weight cutoff = 3500 Da), filtered with a 0.22 μm filter membrane, and then freeze-dried to obtain solid adipic acid dihydrazide-modified HA (HA-ADH). HA-ADH was characterized by 1H NMR (DMX 360, Bruker, Billerica, MA),35 and the hydrazide modification degree of disaccharide repeat units was approximately 49%.

2.3. Preparation of the DN Hydrogel

An appropriate amount of GelMA was added to the LAP solution and dissolved at 50 °C to prepare mass percentage concentrations of 5, 10, 12.5, 15, and 20% GelMA precursor solutions. The GelMA precursor solution was placed into a mold and irradiated with a blue-violet light source for 10 s to form the hydrogel at 37 °C.

OHA and HA-ADH were dissolved separately in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at concentrations of 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3% and mixed for hydrogel formation with equal mass ratios of OHA and HA-ADH. The OHA solution was slowly added to the HA-ADH solution and vortexed to form the hydrazone-crosslinked HA (HA-HYD) hydrogel. After centrifugation to remove bubbles, the gelling process was continued for 2 h at 37 °C. Freeze-dried HA-HYD hydrogel composites were characterized using an FTIR spectrometer, and the spectra were recorded in the absorbance mode from 4000 to 600 cm–1 for 32 scans at a 4 cm–1 resolution.33

The precursor solutions of GelMA, OHA, and HA-ADH were slowly added to the mold in order and mixed well while stirring and then irradiated with a blue-violet light source for 10 s to form the DN hydrogel at 37 °C; the formulations are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Formulations of the DN Hydrogels.

| hydrogel formulations | notations |

|---|---|

| 10% GelMA, 3% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 5% GelMA-1.5% HA-HYD |

| 10% GelMA, 4% OHA, and 4% HA-ADH | 5% GelMA-2% HA-HYD |

| 10% GelMA, 5% OHA, and 5% HA-ADH | 5% GelMA-2.5% HA-HYD |

| 20% GelMA, 3% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 10% GelMA-1.5% HA-HYD |

| 20% GelMA, 4% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD |

| 20% GelMA, 5% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 10% GelMA-2.5% HA-HYD |

2.4. Extrusion-Based 3D Printing of the DN Hydrogel

The composite bio-inks were obtained by blending GelMA solution with OHA solution and HA-ADH solution using a medical three-way syringe to form a bio-ink that was half gel and half solution at 37 °C, and the formulations are listed in Table 2. A 3D bioprinter (LivPrint Lead, Medpin, China) was used to print the DN hydrogel. Standard software was used to generate G-code (Slic3r) based on STL files representing 3D CAD models (AutoCAD), communicating the commands to direct the layer-by-layer printing movements. The printer setup was as follows: an extrusion speed of 1 mm/s, a printer speed of 70%, a layer thickness of 200 μm, and an infilling of 35%. The 3D printer was adjusted to 25 °C, and the syringe loaded with the bio-ink was placed into the barrel and allowed to stand for 30 min. The bio-ink was extruded through a 25 G needle with an inner diameter of 260 μm and a length of 13 mm onto the printing plate, which was cooled to 4 °C. 3D scaffolds were printed and then exposed to a blue-violet light source for 10 s for permanent crosslinking. The printed scaffold was soaked in alcohol for sterilization prior to cell experimental studies.

Table 2. Formulations of the DN Hydrogels as 3D Printing Bio-inks.

| hydrogel formulations | notations |

|---|---|

| 10% GelMA, 3% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 5% GelMA-1.5% HA-HYD |

| 10% GelMA, 4% OHA, and 4% HA-ADH | 5% GelMA-2% HA-HYD |

| 10% GelMA, 5% OHA, and 5% HA-ADH | 5% GelMA-2.5% HA-HYD |

| 20% GelMA, 3% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 10% GelMA-1.5% HA-HYD |

| 20% GelMA, 4% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD |

| 20% GelMA, 5% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 10% GelMA-2.5% HA-HYD |

| 30% GelMA, 3% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 15% GelMA-1.5% HA-HYD |

| 30% GelMA, 4% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 15% GelMA-2% HA-HYD |

| 30% GelMA, 5% OHA, and 3% HA-ADH | 15% GelMA-2.5% HA-HYD |

The structural integrity of the printed scaffold with different notations was evaluated using a stereoscopic microscope.

2.5. Characterization

2.5.1. Microstructure and Porosity Measurements

The freeze-dried hydrogel sample was cut to expose the full cross section. The sample was glued to a copper sheet with a conductive adhesive and sprayed with gold. The morphology of the cross-sectional structure was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Zeiss MERLIN Compact) at an acceleration voltage of 10 kV. The pore size of the hydrogel sample was measured using ImageJ software.

2.5.2. Evaluation of the Swelling Ratio

The hydrogels were prepared with 100 μL of the precursor solution containing GelMA, OHA and HA-ADH, or GelMA, OHA, and HA-ADH, and the initial weight of the hydrogels was recorded as W0; they were then soaked in PBS (0.01 M, pH of 7.2–7.4) and incubated at 37 °C. The hydrogels were removed every 2 h, and the surface water was gently wiped dry with absorbent paper and weighed, which was recorded as W1. Swelling equilibrium was reached when the weight of the hydrogels did not change. Each formulation contained three parallel samples.

The formula for swelling balance is as follows:

2.5.3. Compressive Strength Testing

The mechanical properties of the hydrogels and printed scaffolds were investigated by conducting a compression test using a universal material testing machine (3345, Instron, US). The precursor solution (600 μL) was placed into a 48-well plate to prepare a cylinder with a diameter of 10 mm and a thickness of 5 mm. The compressive moduli of the hydrogel and the printed scaffold were determined by taking the slope of the linear part of the stress–strain curve in the 0–30% strain region. For repeated loading cycles, the sample was compressed to a strain of 30% and unloaded to a strain of 0% at a constant test speed of 1 mm/min, with no time interval in between, repeating six test cycles. The compressive modulus of the hydrogel was determined from the slope of the loading curve from 0 to 30%, while the hysteresis energies were calculated from the integral area of the stress–strain curve.

2.5.4. Rheological Testing

The rheological properties of the hydrogel were tested using an MCR 302 modular rheometer (Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) equipped with plate–plate geometry (10 mm plate diameter) at 25 °C. To observe the state and stability of the hydrogel, a rheometer plate operating at 10 rad/s and a 0.5% strain was used to conduct a dynamic time scan experiment. The effect of temperature on the behavior of the hydrogel was then measured by ramping from 0 to 50 °C at a 10 rad/s angular frequency and a 0.5% strain, with the heating rate set to 4 °C/min. The linear viscoelastic zone of the hydrogel was determined by strain sweeping from 0.01 to 1000% at an angular frequency of 1 rad/s. The self-healing properties of the hydrogel were investigated by repeating alternating strain sweep with alternating small (1% strain) and large (350% strain) oscillation forces.

To investigate the viscosity of the bio-inks, the shear rate sweep was measured at shear rates ranging from 0.01 to 100 s–1.

2.5.5. Self-Healing Behavior Testing

The self-healing ability of the hydrogels was evaluated using a macroscopic self-healing method. Hydrogel samples were dyed using different colors. The hydrogel was cut into two disc-shaped pieces, and then, the cut surfaces were positioned in tight contact and placed in a closed environment to closely observe the self-healing process of the hydrogel. The ability of the repaired hydrogel to maintain its structure under gravity confirmed its self-healing properties.

2.6. In Vitro Biocompatibility Studies

Rabbit bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The cells were incubated in a complete medium containing 89% Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM, HyClone), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Solarbio). The culture medium was changed every two days. Only three-passage BMSCs were used in the experimental studies.

One milliliter of the cell suspension (2 × 105/mL) was dropped onto the scaffold and cocultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After culturing for 1, 3, and 5 days, the viability of the BMSCs was examined by staining the samples using a LIVE/DEAD cell viability/cytotoxicity kit (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were captured using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM710, Carl Zeiss, Germany). Living cells showed green fluorescence, whereas dead cells showed red fluorescence. The proliferation of BMSCs cultured on the scaffold was detected using a cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. To visualize the morphology of BMSCs on the scaffold, TRITC phalloidin and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) were used to stain the cells, and images were taken using a confocal laser scanning microscope; the cytoskeleton showed red fluorescence, while the nucleus showed blue fluorescence.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical differences between the groups were tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 were considered significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of the DN Hydrogel

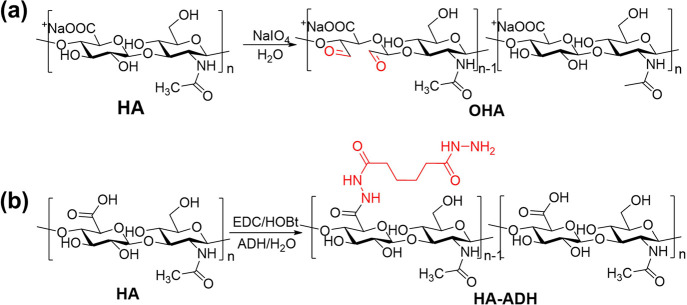

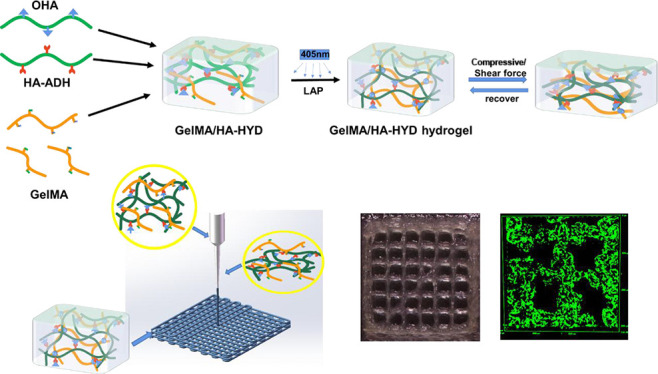

A dynamic/photocrosslinking gelatin-HA DN hydrogel with high mechanical strength, self-healing properties, and biocompatibility was prepared. The designed hydrogel was based on gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) and amino- and aldehyde-modified HA (HA-ADH and OHA). In the processing of the DN hydrogel formation, the hyaluronic acid (HA-HYD) network was formed by covalent hydrazone crosslinking as the dynamic network after mixing HA-ADH and OHA with GelMA; then, the GelMA network was formed by photocrosslinking as the static network (Figure 1). HA-ADH was obtained by amidation between adipic acid dihydrazide and carboxyl groups of HA (Figure 2a), and the proximal hydroxyl group in HA was oxidized by sodium periodate (NaIO4), introducing dialdehyde into several HA dimer units, opening the sugar ring, and forming OHA (Figure 2b). The amino group on HA-ADH reacts with the aldehyde group on OHA to form a reversible dynamic covalent hydrazone bond. The degree of modification of HA-ADH was determined by the 1H proton NMR spectrum according to Hsiu-O. Ho et al.35 The methylene signal peaks at δ 1.7 and 2.4 ppm confirmed that HA was successfully modified by adipic acid dihydrazide (Figure 3a). Using N-acetyl methyl (δ = 1.95–2.00 ppm) as the internal standard, the amino substitution degree was calculated to be 49%. An absorption peak of the aldehyde groups (C=O) in OHA appeared at 1723 cm–1 in the FTIR spectrum (Figure 3b), which confirmed that NaIO4 oxidized the carboxyl groups on HA. The aldehyde groups (C=O) in OHA reacted with the amino groups of HA-ADH via Schiff base formation, resulting in the formation of the HA-HYD hydrogel. The formation of crosslinks in HA-HYD hydrogels was also investigated by FTIR, and the hydrazone bond (C=N) in the HA-HYD hydrogel was observed at 1627 cm–1 (Figure 3c).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the synthetic route of the DN hydrogel and image of hydrogels.

Figure 2.

Synthetic scheme for the preparation of (a) OHA and (b) HA-ADH.

Figure 3.

Characterization of HA-ADH, OHA, and HA-HYD. (a) NMR spectrum of HA-ADH. (b) FTIR spectrum of OHA. (c) FTIR spectrum of HA-HYD.

3.2. Characterization of the DN Hydrogel

3.2.1. Microstructure and Porosity

The swelling properties, degradation profiles, and mechanical strength of the hydrogels correlated directly with their microscopic structures.22 SEM provided insight into the microstructure of GelMA, HA-HYD single-network (SN) hydrogels, and DN hydrogels. As indicated in the SEM images (Figure 4a–c), all hydrogels exhibited a highly interconnected porous structure with uniform mesh sizes. This porous structure proved that these hydrogels are suitable for the survival of cells and exchange of nutrients. The average pore sizes of GelMA, HA-HYD SN hydrogels, and DN hydrogels were 23, 22, and 15 μm, respectively. The pore size of the DN hydrogel was smaller than that of the SN hydrogel. This may be because GelMA molecules and HA-HYD molecules formed an interpenetrating network structure, which increased the internal crosslinking density of the DN hydrogel.

Figure 4.

SEM images of the hydrogels. (a) 10% GelMA, 500×; (b) 2% HA-HYD, 500×; (C) 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD, 500×. Scale bar = 20 μm. (d) 10% GelMA, 1000×; (e) 2% HA-HYD, 1000×; (f) 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD. 1000×. Scale bar = 10 μm. (g) Pore sizes of three distinct hydrogel systems.

3.2.2. The Swelling Ratio

The swelling ratio of the hydrogel influences many properties, such as nutrition penetration and oxygen transfer. At the same time, the swelling ratio of the hydrogel is affected by many factors, such as the concentration and hydrophilicity of the polymer, the composition, and the network structure of the hydrogel.16 The swelling capacities of the hydrogels were investigated as a function of incubation time in 0.01 M PBS buffer at 37 °C. The swelling ratios of GelMA, HA-HYD SN hydrogels, and DN hydrogels are shown in Figure 5; the swelling ratio increased more obviously in the first 2 h, and the swelling balance was reached after 6 h. The results showed that the hydrogel concentration affected the swelling ratio of the hydrogel. For the DN hydrogels with 5 and 10% GelMA, the swelling ratio decreased with increasing concentration of HA-HYD (Figure 5c,d). The decrease in the swelling ratio might be due to the fact that as the concentration increased, the molecular chains became more closely entangled, generating a denser crosslinked network structure, and the smaller pore size influenced water molecule penetration, resulting in a reduced swelling rate. As shown in Figure 5a,b, the swelling ratio of the 5% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel was less than those of 5% GelMA and 2% HA-HYD SN hydrogels, and the swelling rate of the 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel was less than those of 10% GelMA and 2% HA-HYD SN hydrogels, which may be attributed to the DN hydrogel integrating the two polymer networks, resulting in an increase in the crosslinking network density, thereby reducing the swelling rate.

Figure 5.

Swelling ratio of the hydrogel. (a) 5% GelMA, 2% HA-HYD SN hydrogel, and 5% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel. (b) 10% GelMA, 2% HA-HYD SN hydrogel, and 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel. (c) 5% GelMA-1.5/2/2.5% HA-HYD DN hydrogels. (d) 10% GelMA-1.5/2/2.5% HA-HYD DN hydrogels.

3.2.3. Compressive Strength

The mechanical strength of hydrogels is an important indicator of their suitability as a biomedical material; the scaffold materials for tissue engineering need to have suitable mechanical properties that match the repaired tissue.36,37Figure 6a–d indicates that the compression moduli of the DN hydrogel were significantly higher than those of the SN hydrogel. The compression moduli of the 5 wt % GelMA and 2 wt % HA-HYD SN hydrogels were 9.40 ± 1.02 and 5.21 ± 0.47 kPa, respectively, and the compression modulus of the 5 wt % GelMA-2 wt % HA-HYD DN hydrogel increased to 26.25 ± 4.76 kPa. The compression moduli of the 10 wt % GelMA and 2 wt % HA-HYD SN hydrogels were 45.42 ± 2.83 and 5.21 ± 0.47 kPa, respectively, and the compression modulus of the 10 wt % GelMA-2 wt % HA-HYD DN hydrogel increased to 101.02 ± 6.41 kPa, which was 20 times higher than that of the 2 wt % HA-HYD SN hydrogel and two times higher than that of the 10 wt % GelMA SN hydrogel.

Figure 6.

Compressive modulus (a, c, e, and g) and compressive stress–strain curves (b, d, f, and h) of the hydrogels.

The compression moduli of the DN hydrogels with different composition ratios are shown in Figure 6e–h. With a GelMA concentration of 5 wt % in the DN hydrogel, the compression modulus of the hydrogel increased from 16.04 ± 0.79 to 56.16 ± 5.73 kPa with the increase in the HA-HYD concentration. At a GelMA concentration of 10 wt %, as the proportion of HA-HYD increased, the compression modulus of the hydrogel increased from 70.12 ± 2.60 to 169.00 ± 5.86 kPa with the increase in the HA-HYD concentration. When the concentration of HA-HYD was 2.5%, the compression modulus increased significantly. The stress–strain curve followed the same pattern as that of the elastic modulus plot.

3.2.4. Rheological Properties

When the storage modulus (G′) of a hydrogel is greater than the loss modulus (G″), it is in a gel state, and when G′ is less than G″, the hydrogel is in a solution state.38 Considering that GelMA is thermo-sensitive, we studied the effect of temperature on the rheological behavior of DN hydrogels. As shown in Figure 7a–d, the experimental results indicated that the G′ of the GelMA hydrogel presented a downward trend in the range of 25–40 °C, which was attributed to the GelMA retaining the temperature-sensitive properties of gelatin; that is, at a low temperature (25 °C), it was in a gel state, and when the temperature was higher, the “gel–sol” transition occurred and its G′ decreased accordingly. In the oscillation temperature scanning experiment of the HA-HYD hydrogel, the G′ of HA-HYD did not change with temperature, indicating that HA-HYD has no temperature sensitivity. However, because the DN hydrogel also contained GelMA, in the temperature scanning experiment of the DN hydrogel, we also observed a phenomenon similar to GelMA; that is, there was a downward trend of G′ in the range of 25–40 °C.

Figure 7.

Rheological properties of the hydrogels (time scan). (a) 5% GelMA, 2% HA-HYD SN hydrogel, and 5% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel. (b) 5% GelMA-1.5/2/2.5% HA-HYD DN hydrogels. (c) 10% GelMA, 2% HA-HYD SN hydrogel, and 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel. (d) 10% GelMA-1.5/2/2.5% HA-HYD DN hydrogels.

The G′ value of the hydrogel is one way of characterizing its mechanical properties. The hydrogels were tested by scanning the oscillation time. For the 10 wt % GelMA-2 wt % HA-HYD DN hydrogel, the G′ of the DN hydrogel (4794.21 ± 36.41 Pa) was higher than those of GelMA (3072.43 ± 21.66 Pa) and HA-HYD (3072.43 ± 21.66 Pa) SN hydrogels (Figure 8c). G′ increased with the concentration of HA-HYD in the DN hydrogels when the concentration of the GelMA hydrogel was fixed. With a GelMA concentration of 10 wt % in the DN hydrogel, the G′ of the DN hydrogel increased from 4183.16 ± 87.68 to 9925.43 ± 145.47 Pa with the increase in the HA-HYD concentration (Figure 8d). The G′ of the DN hydrogels with 5 wt % GelMA and different concentrations of HA-HYD also showed the same trend (Figure 8a,b). Throughout the testing process, the G′ and G″ of SN and DN hydrogels showed no significant change, indicating that the hydrogels were in a stable state.

Figure 8.

Rheological properties of the hydrogels (temperature scan). (a) 5% GelMA, 2% HA-HYD SN hydrogel, and 5% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel. (b) 5% GelMA-1.5/2/2.5% HA-HYD DN hydrogels. (c) 10% GelMA, 2% HA-HYD SN hydrogel, and 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel. (d) 10% GelMA-1.5/2/2.5% HA-HYD DN hydrogels.

Hydrogels are usually soft, weak, and brittle and are therefore not suitable for the construction of load-bearing tissues. One of the strategies to improve the mechanical strength of hydrogels is to develop DN hydrogels with an interpenetrating polymer network structure, which can obtain strong and stiff hydrogels.39 The DN strategy utilizes a combination of the distinct properties of two crosslinking networks. The toughening mechanism is attributed to the sacrificial network that effectively dissipates energy and protects the other network from fracture.40 Testing of compressive strength and rheological properties both confirmed that the mechanical strength of the dynamic/photocrosslinking gelatin-HA DN hydrogel was significantly enhanced compared with those of GelMA and HA-HYD SN hydrogels. In this DN hydrogel, the photocrosslinked GelMA network formed a static covalent network, and the hydrazone-crosslinked HA-HYD network formed a dynamic covalent crosslink. Under deformation by force (compression or shear), the HA-HYD network dissipates energy by the fracture of its dynamic covalent crosslinks, whereas the GelMA network remains intact and allows the hydrogel to recover from strain. Therefore, the combination of these two types of networks leads to enhanced mechanical properties of DN hydrogels. Meanwhile, the mechanical strength of the DN hydrogel can be controlled by changing the composition ratio and concentration of GelMA and HA-HYD.

3.2.5. Self-Healing of the Hydrogels

The self-healing properties of the HA-HYD hydrogel and the DN hydrogel were evaluated by examining their macroscopic self-healing behavior. Disc-shaped hydrogels with a diameter of 10 mm and a height of 5 mm were split in half using a surgical blade and then recombined at 25 °C without any external stimulation. Complete self-healing took place in 30 min, as shown in Figure 9a, and the discs would not separate under the influence of gravity.

Figure 9.

Self-healing behavior of hydrogels. (a) 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel: cutting and self-healing. (b) Pictures of GelMA, HA-HYD, and 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogels: before compression, during compression, and after compression. (c) Amplitude scan carried out from 0 to 350% strain with the GelMA-HA-HYD DN hydrogel. (d) G′ and G″ of the hydrogel under continuous strain sweep with an alternate small oscillation force (1% strain) and a large one (350% strain). Angular frequency = 10 rad s–1. (e) Compressive stress–strain curves for repeated loading up to a 30% strain of DN hydrogels. (f) Compressive cycle-stress curves for repeated loading up to a 30% strain of DN hydrogels. (g) Schematic diagram of self-healing of the DN hydrogel.

As shown in Figure 9b, GelMA, HA-HYD, and 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogels were compressed to a 50% strain. The GelMA hydrogel did not restore its original shape after compression and was completely broken because the GelMA hydrogel was photocrosslinked by carbon–carbon covalent bonds (C=C), which were not recovered after breaking. The HA-HYD and DN hydrogels could return to their original shape after the compressive force was removed because both hydrogels contained the HA-HYD network crosslinked by dynamic hydrazone bonds. To ensure the integrity of the DN hydrogel, load–unload tests of compression by a 30% strain were carried out to study the self-healing properties of the DN hydrogel (Figure 9e,f). A total of six loading and unloading tests were performed. The stress trends were 31.11, 31.00, 30.79, 30.04, 29.17, and 28.99 kPa, showing no significant change. At the same time, the six cycles of hysteresis energies after the loading and unloading cycles were 46.77, 42.18, 44.88, 48.30, 49.60, and 47.20 kJ/m3. They correspond to self-healing efficiencies of 90.18, 95.96, 107.62, 102.69, and 95.16%, respectively, calculated by dividing the lag energy of a cycle by that of the previous cycle. The stress–strain curve under cyclic compressive strain changes almost synchronously between the loading and unloading cycles, which may be due to the hydrazone bond breaking during loading and the quick recovery of the Schiff base during unloading.

Amplitude scanning was used in rheology to determine the gel–sol transition point of the 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel, which was the shear yield point, and to evaluate the self-healing performance of the DN hydrogel. The results of amplitude scanning are shown in Figure 9c,d. At a 315% strain, G″ became greater than the G′, and the DN hydrogel changed from a gel state to a solution state, which means that the dynamic hydrazone crosslinking of HA was destroyed under shear stress. When the strain is greater than 315%, the hydrogel is at a solution state, while when the strain is smaller than 315%, the hydrogel is at a gel state, so the 1 and 350% strain values were used for the dynamic cyclic strain sweep experiment, which was done for three cycles. The DN hydrogel showed a quick drop in G′ when a 350% strain was applied and a rapid recovery when a 1% strain was applied, providing further indication of the self-healing potential of the hydrogel. This self-healing performance is exactly what biological tissues such as the cartilage, tendons, and muscles need. It can help the tissue withstand the external force and dissipate a part of the external force.

3.3. 3D Printing of the DN Hydrogel Scaffolds

3D printing provides a rapid and robust approach for the fabrication of functional scaffolds for tissue engineering. The development of 3D printing techniques is strongly dependent on printable biomaterials such as bio-inks.41 For extrusion-based 3D printing, the printability standard of bio-inks is to form uniform and stable filaments during the extrusion process, solidify rapidly after extrusion, and maintain the integrity of the gel structure and sufficient mechanical strength after printing.4 We have developed a dynamic/photocrosslinking gelatin-HA DN hydrogel with enhanced mechanical strength and self-healing properties, which has potential for use as a bio-ink for extrusion-based 3D printing.

An appropriate viscosity of bio-inks is essential for extrusion-based 3D printing. Before printing, the bio-inks were obtained by blending GelMA solution with OHA solution and HA-ADH solution in a medical three-way syringe at 37 °C. A series of different GelMA and HA-HYD components of bio-inks were prepared, which were in the state of half gel and half solution. To evaluate their printability, the rheological properties of the bio-inks were tested. As shown in Figure 10a–c, for the composite bio-inks with 5% GelMA, the viscosity increased as the concentration of HA-HYD increased from 1.5 to 2.5%, and all decreased with an increasing shear rate due to the hydrazone bond in HA-HYD being broken by the shear force, which demonstrates the shear thinning of the bio-inks. For the composite bio-inks with 10 or 15% GelMA, the results showed that the bio-inks were shear-thinning, and the viscosity of the bio-inks could be adjusted by the composition and concentration of GelMA and HA-HYD.

Figure 10.

3D printing of the DN hydrogel scaffolds. (a–c) Viscosities of the DN hydrogels at different concentrations. (d) Phase diagram representing the printability of bio-inks. (e) Stereomicroscope images of the scaffold printed with the DN hydrogels at different concentrations. (f,g) 3D bioprinting setup with a temperature-controlled printhead and a cooling substrate. (h,i) Compressive modulus (h) and compressive stress–strain curves (i) of the DN hydrogel printed scaffolds.

All the bio-inks displayed shear-thinning behavior and were tested for use in extrusion-based 3D printing. At an extrusion speed of 1 mm/s, a printer speed of 70%, and an infilling of 35%, the scaffolds printed by different GelMA and HA-HYD components of bio-inks were observed using a stereomicroscope (Figure 10d,e). Bio-inks with concentrations of HA-HYD and GelMA higher than 2.5 and 15%, respectively, were highly viscous, resulting in them being unextrudable or unable to form regular filaments. The other formulations showed printability, and the scaffold printed by the bio-inks of 10% GelMA-1.5% HA-HYD and 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD had the most uniform filaments (diameter of 0.4 mm) and pore size (1.2 mm).

Before extrusion, the GelMA-HA-HYD bio-ink was in a semisolution and semigel state. During extrusion, the viscosity of the bio-ink decreased because of shear thinning, and the bio-ink passed through the printing nozzle. When the bio-ink was squeezed out of the printing nozzle, the shear force was lost, the hydrazone bond of HA-HYD was reformed, and a stable hydrogel filament with a uniform diameter was formed (Figure 10f,g). At the same time, the GelMA in the filament was photocrosslinked under irradiation by a UV lamp to further increase the mechanical strength. The filaments were printed onto a 3D scaffold via layer-by-layer printing.

The self-healing behavior of the DN hydrogels is conducive to the integration of the layers of filaments. When the subsequent layers of filaments were deposited on the earlier layers, the adjacent layers were combined due to the self-healing property of the DN hydrogel. Together with the photocrosslinking of GelMA in the filaments, the structure of the printed scaffold (approximately 10 mm × 10 mm × 3 mm) with 30 layers was fabricated with a stable structure. The mechanical strength of the printed scaffolds was tested, as shown in Figure 10h,i. When the concentration of GelMA was fixed at 10% and the concentration of HA-HYD was continuously increased, the elastic modulus of the DN hydrogel printed scaffolds increased from 33.5 ± 2.08 to 96.07 ± 6.25 kPa. Scaffolds with high mechanical strength are critical for tissue engineering applications.

3.4. In Vitro Biocompatibility of the DN Hydrogel Printed Scaffolds

In tissue engineering, scaffolds serve as a biomimetic ECM to promote cell growth and proliferation. We applied the dynamic/photocrosslinking gelatin-HA DN hydrogels as a bio-ink to print a 3D scaffold with uniform and connected apertures and enhanced mechanical strength. Although gelatin and HA are both biodegradable and biocompatible biomaterials, they are chemically modified and used as components of the bio-ink. In the process of printing, the bio-inks were extruded, deposited, and crosslinked to form a 3D scaffold. Therefore, the biocompatibility of the DN hydrogel printed scaffold was evaluated to determine its potential as a scaffold for tissue engineering . BMSCs have the ability of multilineage differentiation and can differentiate into chondrocytes, osteoblasts, and adipocytes under appropriate conditions. BMSCs can be implanted as seed cells on scaffolds for tissue engineering and have application potential in the treatment of diseases and tissue repair. In this study, BMSCs were used to assess the biocompatibility of the printed scaffolds.

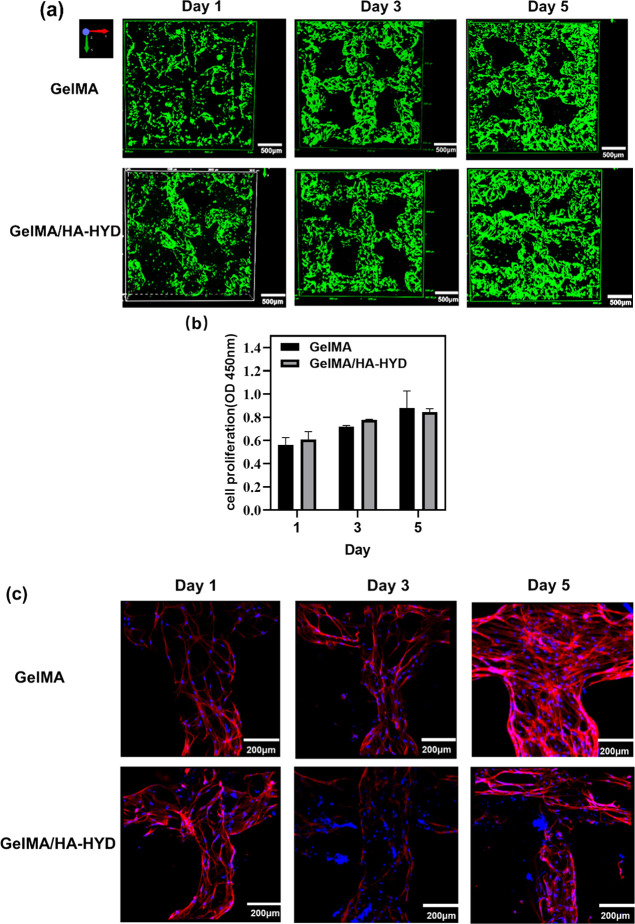

The cytocompatibility of the printed scaffold was investigated using calcein AM staining, a CCK-8 assay, and fluorescent phalloidin/DAPI staining. BMSCs were seeded into the scaffold printed with 10% GelMA and 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD and cultured for 1, 3, and 5 days. The calcein AM staining results showed that after 1 day of culturing, a certain number of BMSCs adhered to the 10% GelMA and 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD scaffolds, the cell viability was high, and no obvious dead BMSCs were observed. After 3 or 5 days of culturing, the number of cells on the two scaffolds increased significantly, and the number of dead cells was lower (Figure 11a). This also showed that the scaffold had better fusion with the BMSCs. The CCK8 assay showed that after 5 days of culturing, the BMSCs on the two printed scaffolds maintained continuous growth, but the BMSC proliferation on the 10% GelMA-2% HA-HYD DN hydrogel printed scaffold was more obvious than that on the 10% GelMA hydrogel printed scaffold (Figure 11b). The above findings indicated that GelMA and the DN hydrogel printed scaffold were both nontoxic to the cells and favorable for BMSC adhesion and survival.

Figure 11.

Biocompatibility of the DN hydrogel printed scaffolds. (a,b) Cell viability and proliferation of BMSCs in the scaffold. (c) Cytoskeleton of BMSCs in the scaffold.

The morphology of BMSCs cultured on the printed scaffold was observed under a confocal microscope by staining the cytoskeleton and the nucleus with phalloidin and DAPI after 1, 3, and 5 days of culturing. On the first day of culturing, there was a small amount of BMSCs attached to the printed scaffold, and the cells showed a long spindle shape on the surface of the printed scaffold with sharp edges and corners, an obvious skeleton structure, and a large cell spreading area. From a morphological point of view, the BMSCs were in a mature state. Cell aggregation was not obvious, and there was no interconnection between the cytoskeleton. After 3 and 5 days of culturing, BMSC proliferation was obvious. The cells on the surface of the two printed scaffolds elongated, migrated, and aggregated with surrounding cells to form a branched and interconnected multicellular network (Figure 11c). These results revealed that the DN hydrogel printed scaffolds were cytocompatible. Hence, the dynamic/photocrosslinking gelatin-HA DN hydrogels represent a potential candidate for bio-inks to fabricate scaffolds for tissue engineering by extrusion-based 3D printing.

4. Conclusions

We proposed a DN hydrogel based on photocrosslinked GelMA and hydrazone-crosslinked hyaluronic acid (HA-HYD), the former as a static covalent network and the latter as a dynamic covalent network, which permits enhanced mechanical strength, self-healing, and 3D printable properties. For shear thinning due to the dynamic hydrazone bond of HA-HYD, the bio-inks based on the DN hydrogel components were suitable for extrusion-based 3D printing. The 3D scaffolds with uniform filaments and pore size were printed layer by layer, and subsequent photocrosslinking increased the mechanical strength, together with the self-healing of the DN hydrogel that created a scaffold with an integrated and stable structure. The printed scaffold had strong mechanical properties and good compatibility. This has laid the foundation for further applications in tissue engineering.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Key Basic Research and Development Projects (no. 2017YFC1103601) and the Key Project of Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (no. 2020B1515120091).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Guo Z.; Dong L.; Xia J.; Mi S.; Sun W. 3D Printing Unique Nanoclay-Incorporated Double-Network Hydrogels for Construction of Complex Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2021, 10, e2100036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conev A.; Litsa E. E.; Perez M. R.; Diba M.; Mikos A. G.; Kavraki L. E. Machine Learning-Guided Three-Dimensional Printing of Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part A 2020, 26, 1359–1368. 10.1089/ten.tea.2020.0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y.; Liu X.; Wei D.; Sun J.; Xiao W.; Zhao H.; Guo L.; Wei Q.; Fan H.; Zhang X. Photo-Cross-Linkable Methacrylated Gelatin and Hydroxyapatite Hybrid Hydrogel for Modularly Engineering Biomimetic Osteon. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 10386–10394. 10.1021/acsami.5b01433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang L.; Highley C. B.; Rodell C. B.; Sun W.; Burdick J. A. 3D Printing of Shear-Thinning Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels with Secondary Cross-Linking. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 1743–1751. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malda J.; Visser J.; Melchels F.; Jüngst T.; Hennink W.; Dhert W.; Groll J.; Hutmacher D. 25th Anniversary Article: Engineering Hydrogels for Biofabrication. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 5011–5028. 10.1002/adma.201302042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.; Mooney D. Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1869–1880. 10.1021/cr000108x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele J.; Ma Y.; Bruekers S.; Ma S.; Huck W. 25th Anniversary Article: Designer Hydrogels for Cell Cultures: A Materials Selection Guide. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 125–148. 10.1002/adma.201302958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimene D.; Kaunas R.; Gaharwar A. K. Hydrogel Bioink Reinforcement for Additive Manufacturing: A Focused Review of Emerging Strategies. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1902026 10.1002/adma.201902026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanbakhsh H.; Bao G.; Luo Z.; Mongeau L.; Zhang Y. Composite Inks for Extrusion Printing of Biological and Biomedical Constructs. ACS Biomat. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 4009–4026. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highley C.; Rodell C.; Burdick J. Direct 3D Printing of Shear-Thinning Hydrogels into Self-Healing Hydrogels. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 5075–5079. 10.1002/adma.201501234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Dai G.; Hong Y. Recent Advances in High-Strength and Elastic Hydrogels for 3D Printing in Biomedical Applications. Acta Biomater. 2019, 95, 50–59. 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzin A.; Miri A.; Sharifi F.; Faramarzi N.; Jaberi A.; Mostafavi A.; Solorzano R.; Zhang Y.; Annabi N.; Khademhosseini A.; Tamayol A. 3D-Printed Sugar-Based Stents Facilitating Vascular Anastomosis. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2018, 7, e1800702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinathan J.; Noh I. Recent Trends in Bioinks for 3D Printing. Biomat. Res. 2018, 22, 11. 10.1186/s40824-018-0122-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faramarzi N.; Yazdi I.; Nabavinia M.; Gemma A.; Fanelli A.; Caizzone A.; Ptaszek L.; Sinha I.; Khademhosseini A.; Ruskin J.; Tamayol A. Patient-Specific Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting of Tissue Engineering Scaffolds. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2018, 7, e1701347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. L.; Highley C. B.; Yeh Y. C.; Galarraga J. H.; Uman S.; Burdick J. A. Three-Dimensional Extrusion Bioprinting of Single- and Double-Network Hydrogels Containing Dynamic Covalent Crosslinks. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2018, 106, 865–875. 10.1002/jbm.a.36323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osi A. R.; Zhang H.; Chen J.; Zhou Y.; Wang R.; Fu J.; Muller-Buschbaum P.; Zhong Q. Three-Dimensional-Printable Thermo/Photo-Cross-Linked Methacrylated Chitosan-Gelatin Hydrogel Composites for Tissue Engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 22902–22913. 10.1021/acsami.1c01321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J. A.; Kamada J.; Koynov K.; Mohin J.; Nicolaÿ R.; Zhang Y.; Balazs A. C.; Kowalewski T.; Matyjaszewski K. Self-Healing Polymer Films Based on Thiol–Disulfide Exchange Reactions and Self-Healing Kinetics Measured Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Macromolecules 2011, 45, 142–149. 10.1021/ma2015134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krogsgaard M.; Behrens M. A.; Pedersen J. S.; Birkedal H. Self-Healing Mussel-Inspired Multi-Ph-Responsive Hydrogels. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 297–301. 10.1021/bm301844u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Yang B.; Zhang X.; Xu L.; Tao L.; Li S.; Wei Y. A Magnetic Self-Healing Hydrogel. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9305–9307. 10.1039/c2cc34745h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y.; Jia H.; Cao T.; Liu D. Supramolecular Hydrogels Based on DNA Self-Assembly. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 659–668. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao C.; Chang H.; Wang M.; Xu F.; Yang J. High-Strength, Tough, and Self-Healing Nanocomposite Physical Hydrogels Based on the Synergistic Effects of Dynamic Hydrogen Bond and Dual Coordination Bonds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 28305–28318. 10.1021/acsami.7b09614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B.; Song J.; Jiang Y.; Li M.; Wei J.; Qin J.; Peng W.; Lasaosa F.; He Y.; Mao H.; Yang J.; Gu Z. Injectable Adhesive Self-Healing Multicross-Linked Double-Network Hydrogel Facilitates Full-Thickness Skin Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 57782–57797. 10.1021/acsami.0c18948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Wong C. W.; Chang S. W.; Hsu S. H. An Injectable, Self-Healing Phenol-Functionalized Chitosan Hydrogel with Fast Gelling Property and Visible Light-Crosslinking Capability for 3D Printing. Acta Biomater. 2021, 122, 211–219. 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J. P.Why are Double Network Hydrogels so Tough? Soft Matter 2010, 6 (). [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.; Jerca V.; Hoogenboom R. Bioinspired Double Network Hydrogels: From Covalent Double Network Hydrogels via Hybrid Double Network Hydrogels to Physical Double Network Hydrogels. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 1173–1188. 10.1039/D0MH01514H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z.; Xia J.; Mi S.; Sun W. Mussel-Inspired Naturally Derived Double-Network Hydrogels and Their Application in 3D Printing: From Soft, Injectable Bioadhesives to Mechanically Strong Hydrogels. ACS Biomat. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 1798–1808. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b01864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonoyama T.; Gong J. Tough Double Network Hydrogel and Its Biomedical Applications. Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 2021, 12, 393–410. 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-101220-080338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z.; Huang K.; Luo Y.; Zhang L.; Kuang T.; Chen Z.; Liao G. Double Network Hydrogel for Tissue Engineering. Wiley Interdiscip Rev. Nanomed. nanobiotechnol. 2018, 10, e1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahadian S.; Ramon-Azcon J.; Estili M.; Obregon R.; Shiku H.; Matsue T. Facile and Rapid Generation of 3D Chemical Gradients within Hydrogels for High-Throughput Drug Screening Applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 59, 166–173. 10.1016/j.bios.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B.; Wang Y.; Miao Y.; Zhang X.; Fan Z.; Singh G.; Zhang X.; Xu K.; Li B.; Hu Z.; Xing M. Hydrogen Bonds Autonomously Powered Gelatin Methacrylate Hydrogels with Super-Elasticity, Self-Heal and Underwater Self-Adhesion for Sutureless Skin and Stomach Surgery and E-Skin. Biomaterials 2018, 171, 83–96. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu D.; Wang H.; Trinh P.; Heilshorn S.; Yang F. Elastin-Like Protein-Hyaluronic Acid (ELP-HA) Hydrogels with Decoupled Mechanical and Biochemical Cues for Cartilage Regeneration. Biomaterials 2017, 127, 132–140. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janarthanan G.; Shin H.; Kim I.; Ji P.; Chung E.; Lee C.; Noh I. Self-Crosslinking Hyaluronic Acid-Carboxymethylcellulose Hydrogel Enhances Multilayered 3D-Printed Construct Shape Integrity and Mechanical Stability for Soft Tissue Engineering. Biofabrication 2020, 12, 045026 10.1088/1758-5090/aba2f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W. Y.; Chen Y. C.; Lin F. H. Injectable Oxidized Hyaluronic Acid/Adipic Acid Dihydrazide Hydrogel for Nucleus Pulposus Regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 3044–3055. 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis M.; Shan J.; Kuhlmann M.; Jungst T.; Tessmar J.; Groll J. Evaluation of Hydrogels Based on Oxidized Hyaluronic Acid for Bioprinting. Gels 2018, 4, 82. 10.3390/gels4040082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C. M.; Huang Y. W.; Sheu M. T.; Ho H. O. Biodistribution Profiling of the Chemical Modified Hyaluronic Acid Derivatives Used for Oral Delivery System. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 64, 45–52. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren P.; Zhang H.; Dai Z.; Ren F.; Wu Y.; Hou R.; Zhu Y.; Fu J. Stiff Micelle-Crosslinked Hyaluronate Hydrogels with Low Swelling for Potential Cartilage Repair. J. Mater. Chem. B Mater. Biol. Med. 2019, 7, 5490–5501. 10.1039/C9TB01155B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Li Z.; Li J.; Yang S.; Zhang Y.; Yao B.; Song W.; Fu X.; Huang S. Stiffness-Mediated Mesenchymal Stem Cell Fate Decision in 3D-Bioprinted Hydrogels. Burns Trauma 2020, 8, tkaa029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y.; Zhang Y.; Zhang H.; Wang Y.; Liu L.; Zhang Q. A Gelatin-Hyaluronic Acid Double Cross-Linked Hydrogel for Regulating the Growth and Dual Dimensional Cartilage Differentiation of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2021, 17, 1044–1057. 10.1166/jbn.2021.3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J. P.; Katsuyama Y.; Kurokawa T.; Osada Y. Double-Network Hydrogels with Extremely High Mechanical Strength. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 1155–1158. 10.1002/adma.200304907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong J. P. Materials both Tough and Soft. Science 2014, 344, 161–162. 10.1126/science.1252389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truby R. L.; Lewis J. A. Printing Soft Matter in Three Dimensions. Nature 2016, 540, 371–378. 10.1038/nature21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]