Abstract

Background

Rituximab (R) has been shown to improve response rates and progression free survival when added to chemotherapy in patients with indolent and mantle cell lymphoma. However, the impact of R on overall survival (OS) when given in combination with chemotherapy (R‐chemo) has remained unclear so far.

Objectives

We thus performed a comprehensive systematic review in this group of patients to compare R‐chemo with chemotherapy alone with respect to OS. Other endpoints were overall response rate (ORR), toxicity and disease control as assessed by measures such as time to treatment failure (TTF), event free‐survival (EFS), progression free‐survival (PFS) and time to progression (TTP).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, EMBASE and conference proceeding from 1990 to 2005.

Selection criteria

Only randomised controlled trials (RCT) comparing R‐chemo with chemotherapy alone in patients with newly diagnosed or relapsed indolent lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) were included.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors extracted data and assessed the study quality. Number needed to treat (NNT) were calculated to facilitate interpretation.

Main results

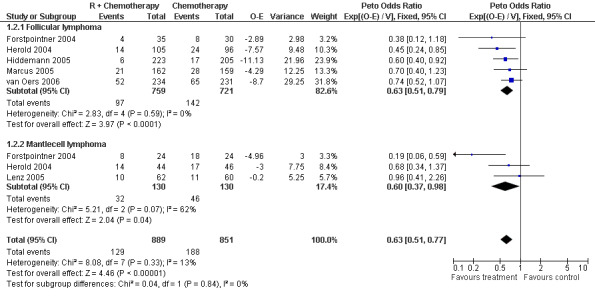

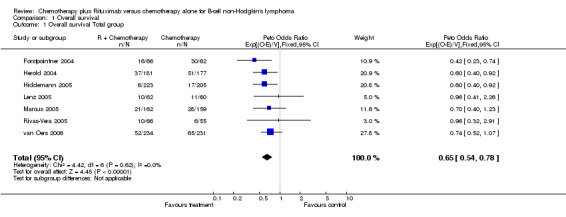

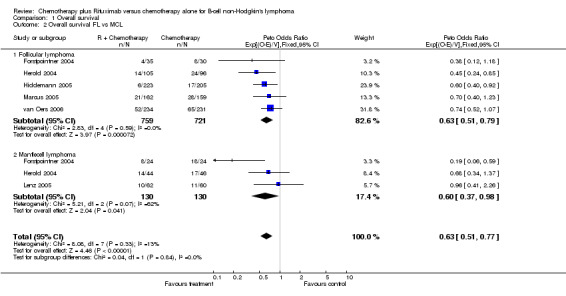

Seven randomised controlled trials involving 1943 patients with follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, or other indolent lymphomas were included in the meta‐analysis. Five studies were published as full‐text articles, and two were in abstract form. Patients treated with R‐chemo had better overall survival (hazard ratio [HR] for mortality 0.65; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54 to 0.78), overall response (relative risk of tumour response 1.21; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.27), and disease control (HR of disease event 0.62; 95% CI 0.55 to 0.71) than patients treated with chemotherapy alone. R‐chemo improved overall survival in patients with follicular lymphoma (HR for mortality 0.63; 95% CI 0.51 to 0.79) and in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (HR for mortality 0.60; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.98). However, in the latter case, there was heterogeneity among the trials (P 0.07), making the survival benefit less reliable.

Authors' conclusions

The systematic review demonstrated improved OS for patients with indolent lymphoma, particularly in the subgroups of follicular and in mantle cell lymphoma when treated with R‐chemo compared to chemotherapy alone.

Keywords: Humans; Antibodies, Monoclonal; Antibodies, Monoclonal/therapeutic use; Antibodies, Monoclonal, Murine-Derived; Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols; Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols/therapeutic use; Lymphoma, B-Cell; Lymphoma, B-Cell/drug therapy; Lymphoma, Mantle-Cell; Lymphoma, Mantle-Cell/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Rituximab; Survival Analysis

Plain language summary

Although the addition of the anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab to chemotherapy (R‐chemo) has been shown to improve response rates and progression‐free survival in patients with indolent or mantle cell lymphoma, the efficacy of R‐chemo with respect to overall survival is unclear.

Study design: Meta‐analysis of seven randomised controlled trials involving 1943 patients. Contribution: Patients treated with R‐chemo had better overall survival, overall response, complete response, and disease control but more leukocytopenia and fever than patients treated with chemotherapy alone. R‐chemo improved overall survival in patients with follicular lymphoma. Implications: Concomitant treatment with rituximab and standard chemotherapy regimens should be considered the standard of care for patients with indolent and mantle cell lymphomas who require therapy and for patients with follicular lymphoma. Limitations: Heterogeneity among the analysed mantle cell lymphoma trials precluded reliable assessment of efficacy of R‐chemo with respect to overall survival. Variability in treatment regimens among trials precluded determination of which chemotherapy regimen is the best to combine with rituximab or about the optimal number of cycles needed to treat patients with indolent lymphoma. Future directions: From our view future studies should focus on the following points: 1. Which standard chemotherapy should be used in combination with Rituximab 2. Influence of clinical and biologic prognostic markers after R‐chemotherapy. What is similar and what is different 3. Understanding rituximab efficacy and resistance 4. Role of rituximab in treatment of progressive disease 5. Mechanism of rituximab in combination with chemotherapy 6. Role of Pharmacokinetic, pharmacogenetics in the treatment with R‐chemo 7. Role of subsequent therapy with rituximab after R‐chemo

Background

Non‐Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are one of the leading causes of death from cancer in the United States and Europe and can be divided into aggressive (fast‐growing) and indolent (slow‐growing) types (Landis 1998). Patients with aggressive B‐cell lymphoma are potentially curable using multi agent chemotherapy such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) (Fisher 1993). The standard of care has changed recently with the implementation of the chimeric anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab (R) (Boye 2003). Combination treatment of R and CHOP (R‐CHOP) or similar regimen has resulted in superior treatment outcome and rendered R‐CHOP as new standard in this group of patients (Feugier 2005, Habermann 2005). The clinical course of indolent lymphoma, which make up 70% of non‐Hodgkin lymphoma and the therapeutic approach differs from that of aggressive lymphoma. Prognosis and therapy for indolent lymphoma are closely related to the extent of the disease at initial diagnosis: less than 15% to 20% of patients with indolent lymphoma are diagnosed at an early stage of the disease (Ann Arbor stage I or II), and half of these patients experience long‐term disease free survival after radiotherapy (Gallagher 1986). However, the vast majority of 80 patients with indolent lymphoma are diagnosed with advanced‐stage disease (i.e., Ann Arbor stage III or IV) and cannot be cured with conventional therapy. These patients do not have a survival benefit from early treatment at diagnosis as compared with a watch‐and‐wait strategy, and it is generally accepted that treatment for such patients should be deferred until the disease becomes symptomatic (Ardeshna 2003, Brice 1997, Barosi 2006). For patients with symptomatic indolent lymphoma, a broad spectrum of therapeutic options are available, ranging from single agents to multi agent regimens or high‐dose chemotherapy (McLaughlin 1986, Zinzani 1998, Williams 2001).

The treatment course is typically characterized by a high initial response rates followed by regular relapse pattern with no or very few long‐term survivors. Therefore, the prognosis of indolent lymphoma with a median survival of 8 to 10 years has changed very little over the last decades (Horning 1993). More recent survival data for patients with advanced indolent lymphoma suggest an improvement in OS over the last 25 years, probably because of sequential application of different chemotherapy regimens, incorporation of biologic agents and improved supportive care (Liu 2006, Swenson 2005).

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) compromises approximately 3‐10% of all NHL, which are often classified as an indolent lymphoma variant, because some patients with this disorder may survive untreated for many years. However, many patients with MCL have more aggressive disease, and for them the median overall survival is 3‐5 years. Therefore therapy should be initiated at the time of diagnosis without deferral of treatment (Brody 2006). Currently, most investigators consider MCL to be an aggressive lymphoma, whereas in the past mantle cell lymphoma were mostly included in clinical trials with indolent lymphoma. Rituximab has shown impressive response and prolonged progression free survival (PFS) in patients with indolent and mantle cell lymphoma when combined with CHOP (Czuczman 2004, Lenz 2005). Randomised phase III trials adding rituximab to a variety of different regimens confirmed these benefits in previously treated as well as in untreated patients with advanced indolent lymphoma (Lenz 2005, Marcus 2005, Forstpointner 2004, Hiddemann 2005, Herold 2004).

Some of these trials (Hiddemann 2005, Forstpointner 2004, Herold 2004) have suggested a trend toward improved overall survival for patients treated with R‐chemo, but the benefit was not definitive. We conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials in which patients with advanced indolent lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma were randomly assigned to receive R‐chemo or chemotherapy alone.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to examine the efficacy of combined immunochemotherapy using R‐chemo compared with identical chemotherapy alone with respect to overall survival. Other endpoints included response rate, toxicity, and disease control as assessed by measures such as time to treatment failure, event‐free survival, progression‐free survival, and time to progression. The impact of maintenance therapy and sequential therapy with rituximab or other immunoconjugates was not addressed.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that enrolled patients older than 18 years with histologically proven indolent lymphoma regardless of stage of disease or previous therapy. The studies were analysed if R‐chemo was compared with identical chemotherapy alone. We included full‐text, abstract publication and unpublished data. We excluded ongoing studies, interim analysis, quasi‐randomised studies and studies with 10 or fewer patients per study arm. Studies on patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or with primary central nervous system lymphoma were excluded. As many studies do not provide information with regards to concealment of allocation (COA), a subgroup analysis is to be performed to compare treatment arms with a known COA with those with an unreported one.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria:

1. All persons older 18 years with histologically proven indolent lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma

Exclusion criteria:

Patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Patients with Hepatitis B or C

Patients with T‐cell lymphoma

Patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL)

Types of interventions

Administration of combined chemotherapy with or without the monoclonal anti‐CD20 antibody (Rituximab/Mabthera) to determine whether Rituximab improves disease control and overall survival (OS). For definitions of various clinical and technical terms see "Methods of Review" section.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Overall survival (OS)

Disease control as assessed by time to treatment failure, event free‐survival, progression free‐survival and time to progression

Secondary outcomes

Overall response rate (ORR)

Complete Response (CR) and Partial Response (PR)

Toxicity

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Trials were identified by using comprehensive search strategies for identifying randomised controlled trials (RCT) as described by Dickersin 1994.

We searched a variety of electronic databases, such as the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Lilac and Internet databases of ongoing clinical trials. The electronic databases were initially searched in April 2002 (period covered: from January 1990 through March 2002) and the search was updated in December 2005 (period covered: April 2002 through December 2005).

A preliminary search of specific electronic bibliographic databases to identify relevant RCTs was performed and will be regularly updated in the future. Trials identified thus far are listed in the "unpublished notes" section.

The Cochrane Library and MEDLINE (Silverplatter) were initially searched on 11.4.2002 (years 1990‐2002) and updated in December 2005 using the following key words and truncations (see Appendix 1 for search strategy).

EMBASE was searched on 22.4.2002 through the German Institute for Medical Documentation and Information (DIMDI) using a search filter devised by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (see http:www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html, Appendix 2).

LILAC was searched on 17.4.2002 by Ottavio Clark (Brazil) using the search strategy (see Appendix 3).

Searching other resources

Handsearching

We also hand searched the conference proceedings of

American Society of Hematology,

American Society of Clinical Oncology,

European Society of Medical Oncology

for clinical trials.

Contact

Investigators and pharmaceutical companies identified as active in the field were approached for unpublished data or studies. In addition, haemato‐oncological study groups, such as

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG, South Western Oncology Group (SWOG),

National Cancer Institute (NCI),

European Organisation for the Treatment of Cancer (EORTC),

American Society of Hematology (ASH),

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)

were contacted.

Citations of all trials identified in the search were checked for additional references. No language restrictions were used. The full search strategy is published in the Cochrane library Kober 2002.

Databases of ongoing trials

Following databases were screened for the latest clinical investigations:

www.controlled‐trials.com

http://www.doh.gov.uk/research/nrr.htm

http://clinicaltrials.nci.nih.gov

http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/gui

www.eortc.be/

www.ctc.usyd.edu.au/

www.trialscentral.org/index.html

Data collection and analysis

Trial selection Two reviewers (H. Schulz and N. Skoetz) independently screened and screened for retrieval the titles and abstracts of all studies identified in the literature search to verify compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. When this information was unsatisfactory, we performed a full‐text analysis that considered the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus involving a third reviewer (A. Engert). The same reviewers who screened the studies independently performed data extraction and quality assessment of all included articles. Assessment of the methodologic quality of clinical trials requires information about the design, conduct, and analysis of the trial (Juni 2001). All included studies, regardless of whether they are published or not, were assessed for internal validity parameters, with particular emphasis on randomisation, masking of patients and clinicians, concealment of allocation, documentation of dropout and withdrawals, and intent‐to‐treat analysis. We contacted the first authors of the included studies to obtain unreported data.

Data Analysis and Statistical Methods A fixed effect model was assumed in all meta‐analyses. For binary data, the relative risk (RR) was used as an indicator of treatment effect, and the Mantel‐Haenszel Method was used for pooling. Overall survival and disease control were calculated as hazard ratios (HR) with data from published studies using methods described in Parmar 1998 or derived from binary mortality data. NNT for overall survival was calculated by assuming a 2‐year overall survival of 90% for patients with follicular lymphoma and 70% for mantle cell lymphoma based on methods described by (Altman 1999). We used the ‐years survival, because the median follow up of the analysed studies ranged between 18 and 39 months. In meta‐analyses with at least four trials a funnel plot was generated and a linear regression test Egger 1997) was performed to examine the likely presence of publication bias in meta‐analysis. A P value less than 0.1 was considered statistically significant for the linear regression test. Potential causes of heterogeneity were explored by performing sensitivity analyses to evaluate effects of lymphoma subtype, previous treatment, stage, duration of study, study quality, source of data, and the influence of single large studies on the effectiveness of rituximab treatment. Particular emphasis was made on the evaluation of additional toxicity of R‐chemo in comparison to chemotherapy alone. Toxicity in context means any adverse event occurring during treatment. Toxicity was defined as any adverse events occurring during treatment including death. Analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan, version 4.2.8 for Windows; Oxford, England): The Cochrane Collaboration 2004; the statistical software package R (Ihaka 1996) was used for additional analyses not possible with RevMan. Statistical tests for heterogeneity were one‐sided; statistical tests for effect estimates and for publication bias were two‐sided.

Sensitivity and subgroup analysis Where sufficient data were available, sensitivity and subgroup analysis were performed based on the following characteristics.

Different qualities of studies, e.g. reporting of randomisation, blinding, concealment of allocation and attrition

different quality of studies

different size of studies

different source of studies (published sources vs. unpublished)

previous therapy

indolent lymphoma with the subgroup of follicular lymphoma or mantle cell lymphoma

Results

Description of studies

Trials identified A total of 1345 potentially relevant trials describing treatment with rituximab were identified and screened for retrieval. 62 were evaluated in more detail. Of these, 55 were excluded for the following reasons: 33 articles were reviews, 2 articles described ongoing trials, 2 trials did not use identical chemotherapy in the control arm. 5 trials were non‐randomised. In addition a total of 11 studies proved rituximab as monotherapy, maintenance therapy, consolidation therapy, in combination with radiotherapy, or as sequential treatment . These studies were excluded because they did not compare concurrent R‐chemo as an induction therapy with identical chemotherapy alone. Two trials evaluated the outcome of minimal residual disease, but not the endpoints such as overall survival or disease control.

Characteristics of studies analysed A total of seven randomised controlled trials involving 1943 adult patients were thus included in the systematic review. In these trials 1480 patients had histologically proven FL and 260 patients had MCL. The remaining 203 patients were described as indolent lymphoma (N = 121), or lymphoplasmocytic/cytoid lymphoma or B‐cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (N = 82) (Table 1). Five trials included untreated patients with advanced disease (Ann Arbor III and IV, Rosenberg 1971). The other two trials (Forstpointner 2004, van Oers 2006) included relapsed or refractory patients with follicular or mantle cell histology. The chemotherapy regimens used included CHOP; cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, vincristine, and prednisone (CNOP); cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP); fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (FCM); and mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, and prednisolone (MCP). All trials compared one of these regimens in combination with rituximab (indicated as R‐chemo) with the chemotherapy regimen alone (Table 2). In one trial (Rivas‐Vera 2005), patients were also randomly assigned to a third group to assess treatment with rituximab alone; those patients were not included in this meta‐analysis. In two trials of R‐CHOP versus CHOP, patients who were younger than 60 years (Hiddemann 2005) or younger than 65 years (Lenz 2005) and in remission were eligible for a second random assignment to adjuvant treatment with high‐dose chemotherapy followed by either blood stem cell transplantation or interferon alpha maintenance; patients in remission who were 60 years or older (Hiddemann 2005) or 65 years or older (Lenz 2005) received interferon alpha maintenance. Two studies, one of the FCM regimen combined with rituximab versus FCM (Forstpointner 2004) and the other of R‐CHOP versus CHOP (van Oers 2006) offered patients in remission a second random assignment to either rituximab maintenance or observation. All the trials that offered a second random assignment showed a balanced distribution of the baseline characteristics of the patients included in the initial R‐chemo and chemotherapy arms.

1. Trials included in the Meta‐Analysis.

| Author | Total Group (N) | FL (N) | MCL (N) | Unspecified lymphoma |

| Forstpointner 2004 | 128 | 65 | 48 | 15 |

| Herold 2004 | 358 | 201 | 90 | 67 |

| Hiddemann 2005 | 428 | 428 | not included | none |

| Lenz 2005 | 122 | none | 122 | none |

| Marcus 2005 | 321 | 321 | none | none |

| Rivas‐Vera 2005 | 121 | not applicable | not applicable | 121 |

| van Oers 2006 | 465 | 465 | none | none |

| Total amount | 1943 | 1480 | 260 | 203 |

2. Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author | Therapy | Previous therapy | Ann Arbor stage | High FLIPI risk | Observation time |

| Forstpointner 2004 | 4 x R‐FCM vs 4 x FCM | Yes | III/IV | not applicable | 18 months |

| Herold 2004 | 8 x R‐MCP vs 8 x MCP | No | III/IV | 55% | 36 months |

| Hiddemann 2005 | 6‐8 x R‐CHOP vs 6 to 8 x CHOP | No | III/IV | 45% | 36 months |

| Lenz 2005 | 6 x R‐CHOP vs 6 x CHOP | No | III/IV | 35 % (IPI high and high‐intermediate risk) | 18 months |

| Marcus 2005 | 8 x R‐CVP vs 8 CVP | No | III/IV | 45% | 18 months |

| Rivas‐Vera 2005 | 6 x R‐CNOP vs 6 x CNOP vs 6 x R | No | III/IV | not applicable | 24 months |

| van Oers 2006 | 8 x R‐CHOP vs 8 x CHOP | Yes | III/IV | 37% | 39 months |

The following chemotherapeutic regimens were used:

CHOP cyclophosphamide (d1 750mg/m2), doxorubicin (d1 50mg/m2), vincristine (d1 1,4mg/m2), prednisone ( d1 to d5 100mg/m2) (Lenz 2005, Hiddemann 2005, van Oers 2006)

CNOP cyclophosphamide (d1 750mg/m2), mitoxantrone (d1 12mg/m2), vincristine (d1 1,2mg/m2) prednisone (d1 to d5 100mg) (Rivas‐Vera 2005)

CVP cyclophosphamide (d1 750mg/m2), vincristine (d1 1,4mg/m2), and prednisone (d1 to d5 40mg/m2) (Marcus 2005)

FCM fludarabine (d1 to d3 25mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (d1 to d3 200mg/m2), mitoxantrone (d1 8mg/m2) (Forstpointner 2004)

MCP mitoxantrone (d 3 and d4 8mg/m2), chlorambucil (d3 to d7 3 x 3mg/m2 ), prednisolone (d3 to d7 25mg/m2) (Herold 2004)

All trials compared a combination of one of these regimens plus rituximab with chemotherapy alone. Rituximab was used in a dosage of 375mg/m2 as a concurrent therapy with the combination chemotherapy either on day 1 or on the day before start of chemotherapy. There was one study who had an early failure design where patients were of study when they achieved only a stable disease after 4 cycles of R‐chemo or chemo therapy (Marcus 2005) .

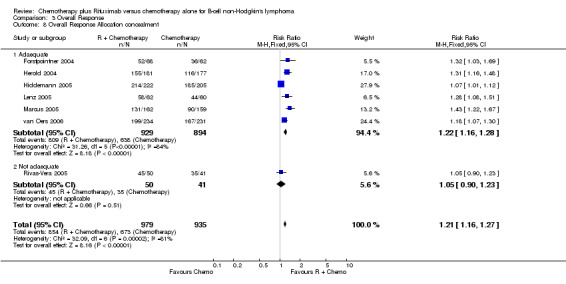

Risk of bias in included studies

Details of the studies are shown in Table 3. All studies were described as randomised and 6/7 trials had a clear and adequate allocation concealment. Most of the studies included intent to treat calculations (6/7) and only a few drop outs were described (Table 3). Only one study of Rivas‐Vera 2005 were not described in detail and we were not able to receive further information according to allocation concealment and intention‐to‐treat‐analysis. The single dosis of 375mg/m2 used for rituximab was equal in all included studies. In exception of the study of Rivas‐Vera 2005 were no information was provided, in all of the studies the two arms of comparison were well balanced. All of the studies were referred to as multicenter studies. Five of the studies were published as full text (Hiddemann 2005;Herold 2004;Lenz 2005;Marcus 2005, van Oers 2006), and two were published in abstract form. For two of the six trials additional unpublished data were provided by the investigators. (Forstpointner 2004;Herold 2004)

3. Quality assessment of the included studies.

| Author | ITT‐ Analysis | Allocation concealed | Drop outs | Source of data |

| Forstpointner 2004 | Yes | Yes | 13% | Full text |

| Herold 2004 | Yes | Yes | 0 | Abstract |

| Hiddemann 2005 | Yes | Yes | 0 | Full text |

| Lenz 2005 | Yes | Yes | 5% | Full text |

| Marcus 2005 | Yes | Yes | 1% | Full text |

| Rivas‐Vera 2005 | No | No | 13% | Abstract |

| van Oers 2006 | Yes | Yes | 0 | Full text |

Effects of interventions

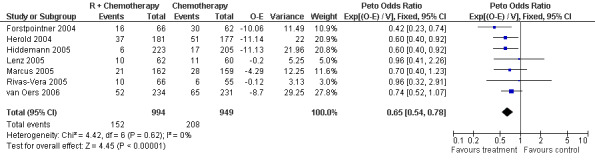

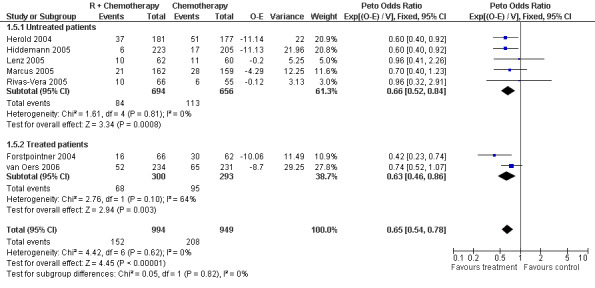

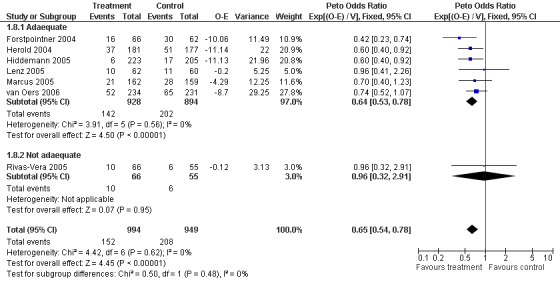

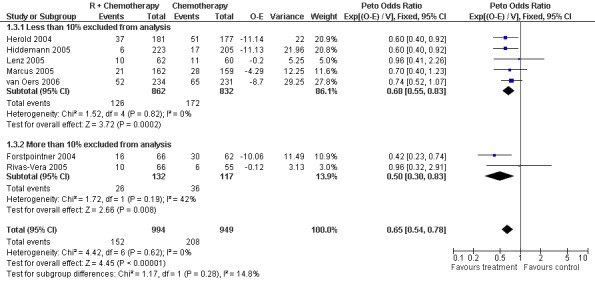

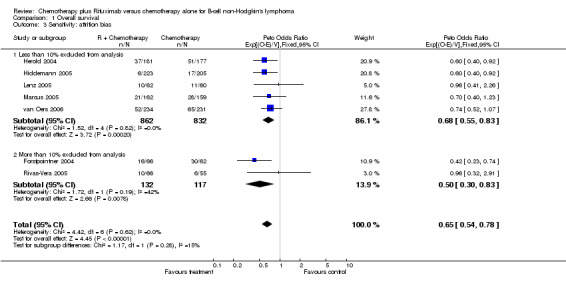

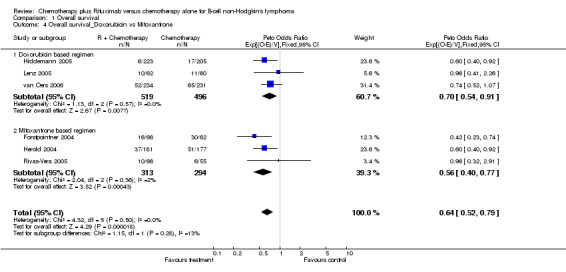

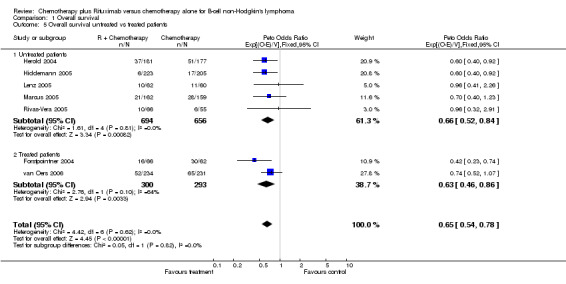

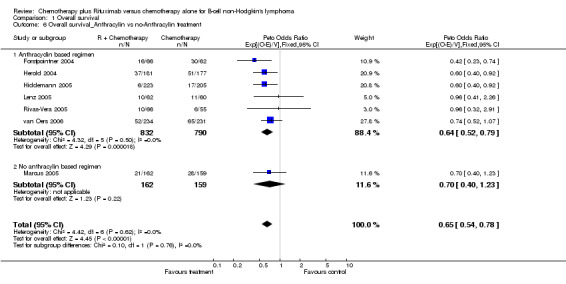

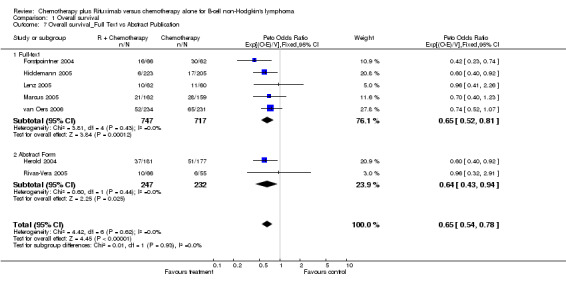

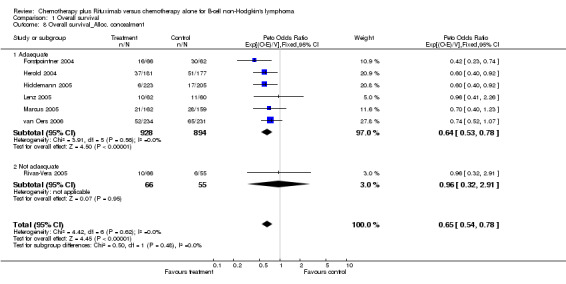

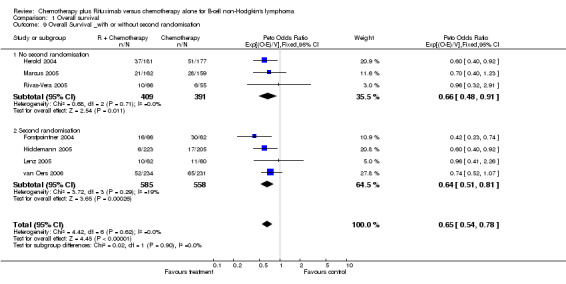

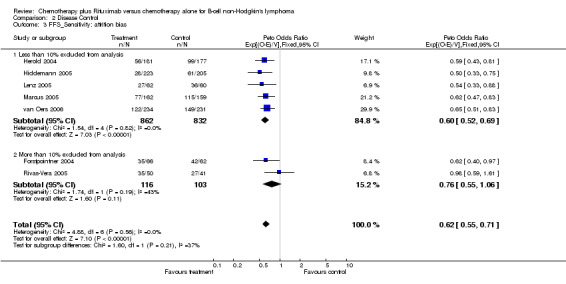

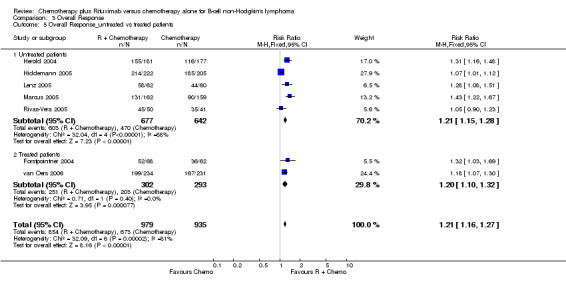

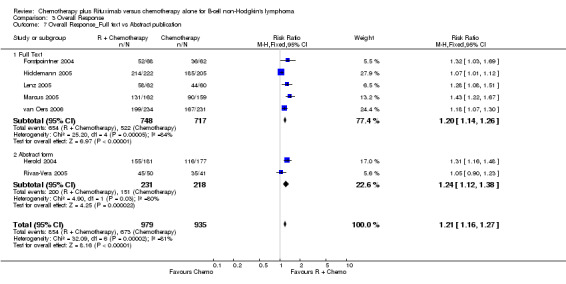

Overall Survival Overall survival data were available for all 1943 patients included in the seven trials. The median observation time for all patients was 24 months (range = 18 to 39 months). There was no heterogeneity among trials (P = 0.62). On the basis of results reported by the individual studies, we calculated a pooled hazard ratio for death from any cause of 0.65 (95% CI = 0.54 to 0.78, Figure 1), indicating statistically significantly better overall survival in the R‐chemo group compared with the chemotherapy‐alone group. A sensitivity analysis revealed no evidence of a difference between the studies with respect whether the patients received previous treatment (Figure 2), the quality of the study (Figure 3, Figure 4), or whether the data were from published versus unpublished sources (see Figure 5).

1.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Overall survival, outcome: 1.1 Overall survival Total group.

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Overall survival, outcome: 1.5 Overall survival untreated vs treated patients.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Overall survival, outcome: 1.8 Overall survival_Alloc. concealment.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Overall survival, outcome: 1.3 Sensitivity: attrition bias.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Overall survival, outcome: 1.7 Overall survival_Full Text vs Abstract Publication.

A total of 1480 patients from five studies were included in our subgroup analysis of overall survival in follicular lymphoma. Of these patients, 759 were treated with R‐chemo, of whom 97 died, and 721 were treated with chemotherapy alone, of whom 142 died. There was no heterogeneity among the trials (P = 0.59). The pooled hazard ratio for mortality for patients with follicular lymphoma was 0.63 (95% CI = 0.51 to 0.79, Figure 6), which indicates statistically significantly better overall survival in the R‐chemo group than in chemotherapy‐alone group. Assuming a 2‐year overall survival rate of 90% for patients with follicular lymphoma and the estimated hazard ratio of 0.63, the number of patients who would need to be treated with R‐chemo to prevent one additional death in 2 years was 28 (95% CI = 21 to 49.7).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Overall survival, outcome: 1.2 Overall survival FL vs MCL.

For the subgroup analysis of patients with mantle cell lymphoma, we included three trials with a total of 260 patients. The calculated hazard ratio for death was 0.60 (95% CI = 0.37 to 0.98, Figure 6), which also indicated an advantage for the R‐chemo group. However, there was heterogeneity among the trials (P = 0.07). In a sensitivity analysis that excluded the study by Forstpointner 2004, which included patients who had relapsed and who had refractory disease, the heterogeneity disappeared (P = 0.54), but there was still an overall survival advantage for R‐chemo compared with chemotherapy alone, with a pooled hazard ratio for mortality of 0.78 (95% CI = 0.45 to 1.35).

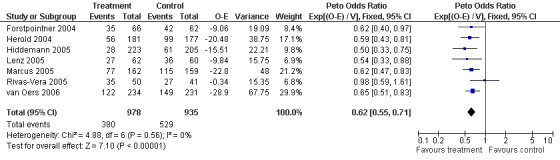

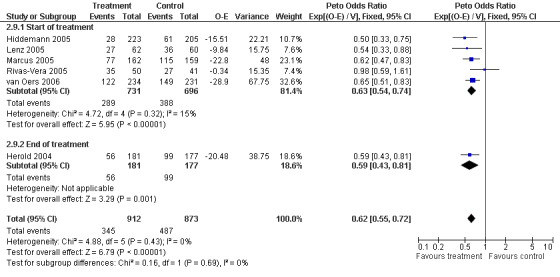

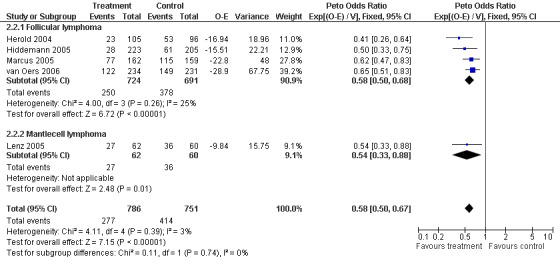

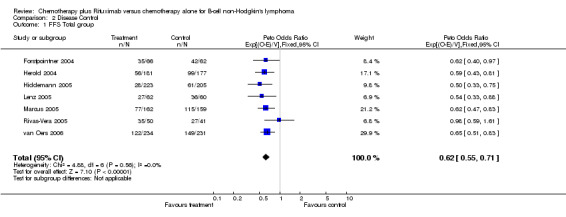

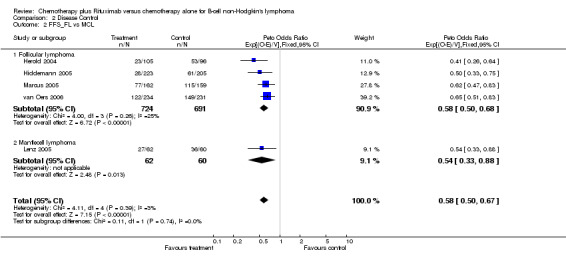

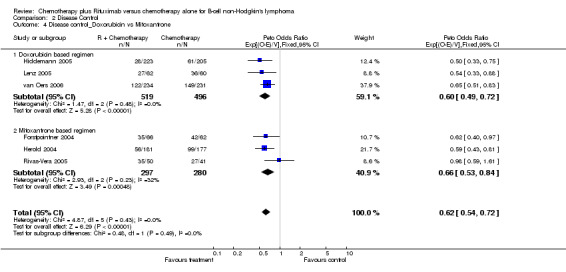

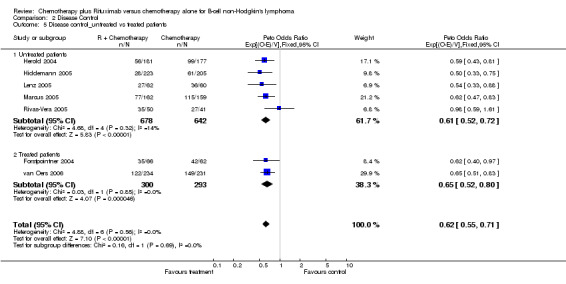

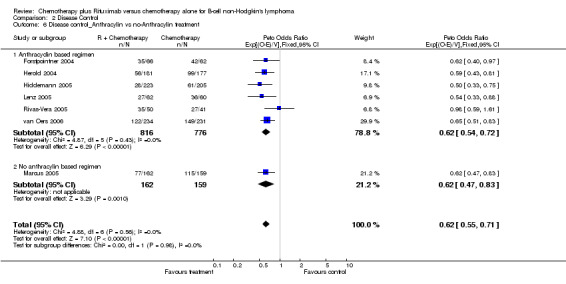

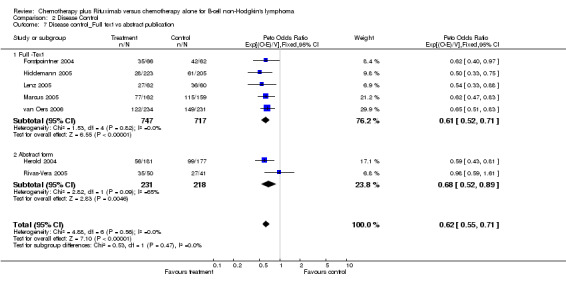

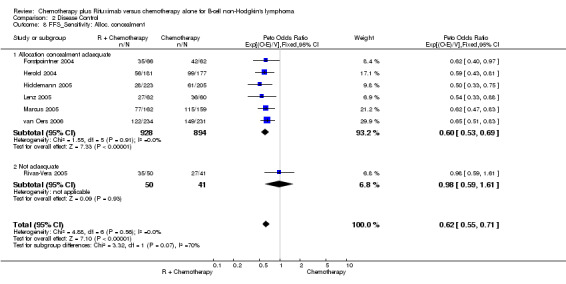

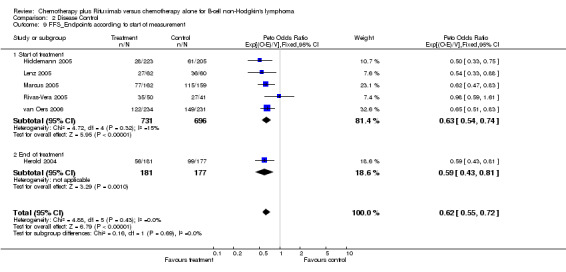

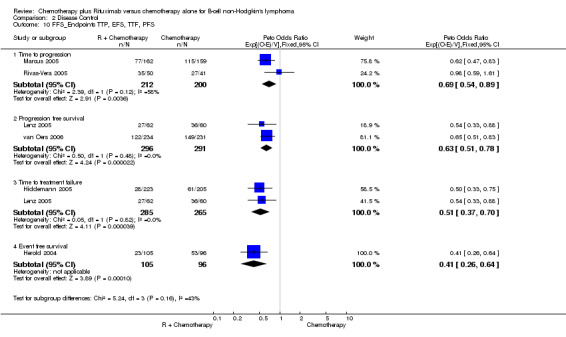

Disease Control The seven trials included in the meta‐analysis described different endpoints for treatment outcome, including event‐free survival, time to treatment failure, progression‐free survival, and time to progression. Documentation of resistance to initial therapy or death was available for 1913 patients. With respect to disease control, R‐chemo was statistically significantly superior to chemotherapy alone, with a pooled HR of 0.62 (95% CI = 0.55 to 0.71, Figure 7). This advantage was also seen in subgroup analyses comparing different defined intervals between the start of treatment and the documentation of death or progressive disease or between the end of treatment and the documentation of progressive disease or death (Figure 8). R‐chemo was also statistically significantly superior to chemotherapy alone when subgroups of follicular lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma were analysed (Figure 9).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Disease Control, outcome: 2.1 FFS Total group.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Disease Control, outcome: 2.9 FFS_Endpoints according to start of measurement.

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Disease Control, outcome: 2.2 FFS_FL vs MCL.

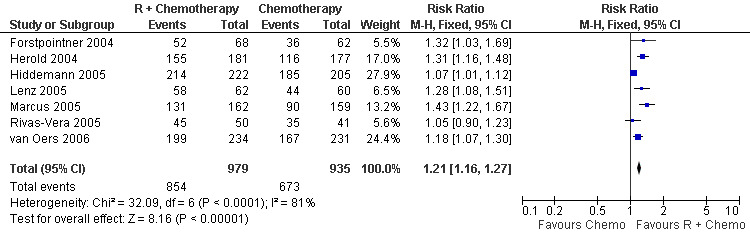

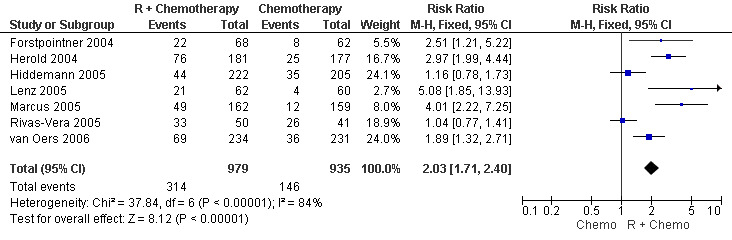

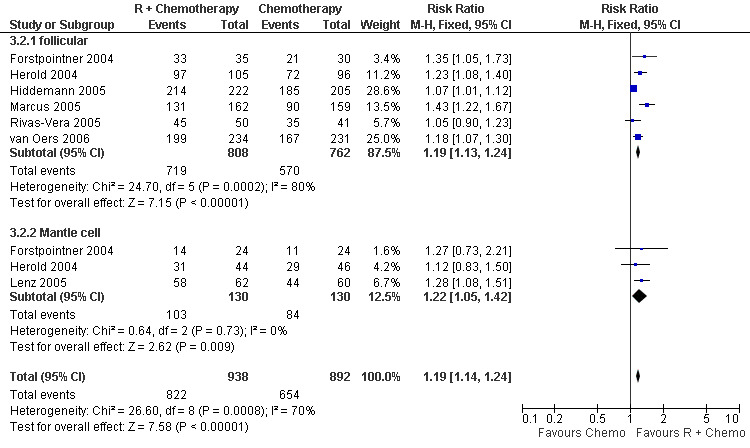

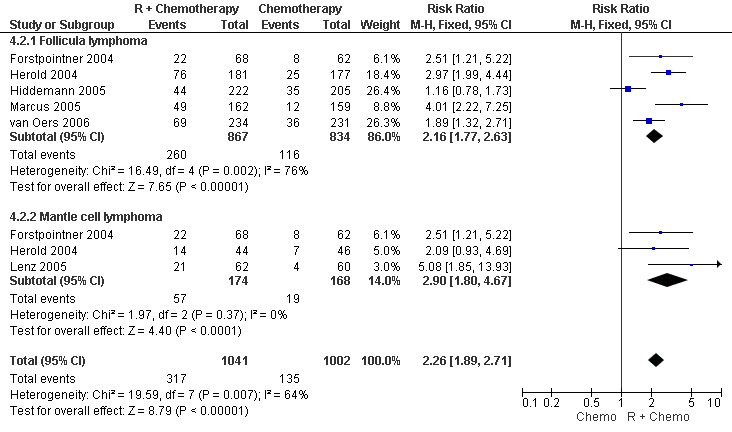

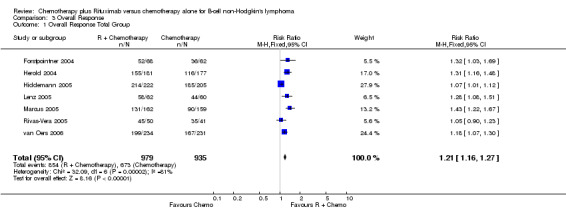

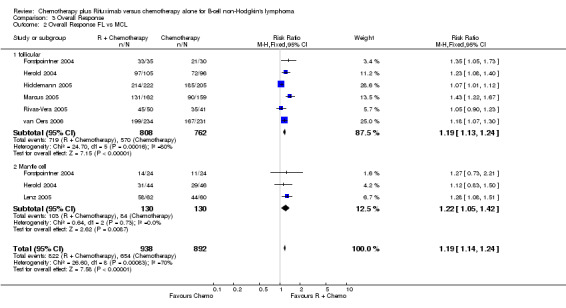

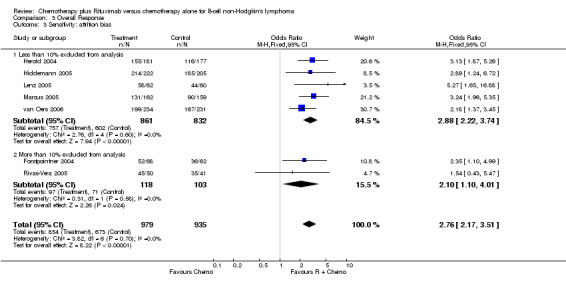

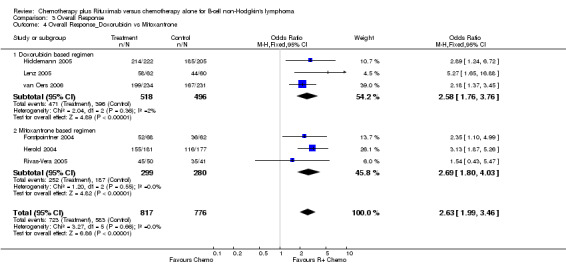

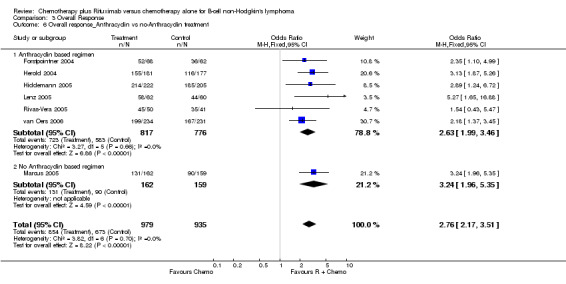

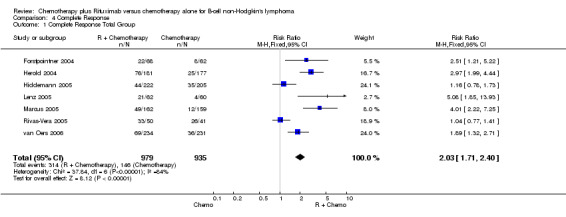

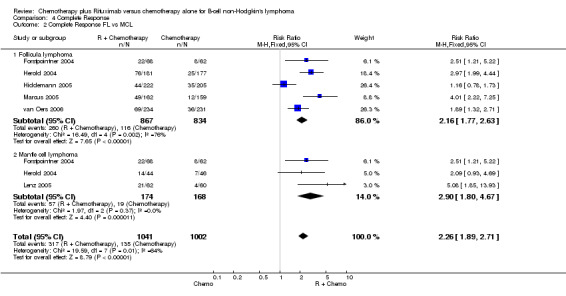

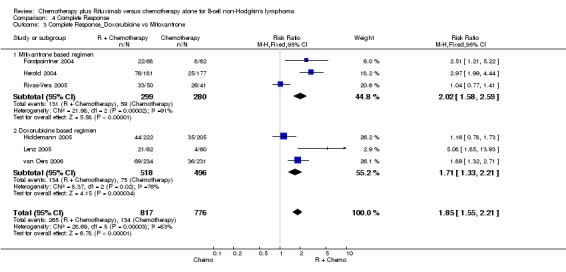

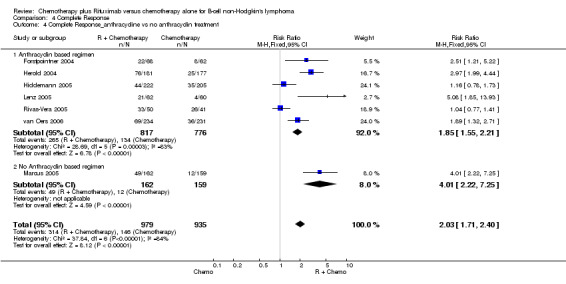

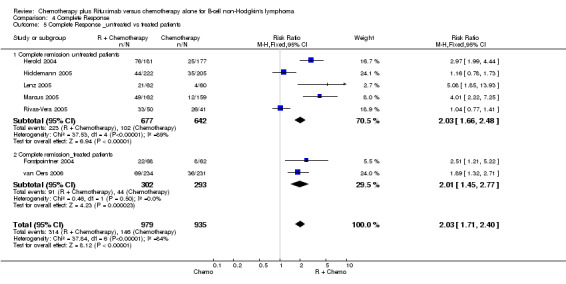

Overall Response and Complete Response rates The data for 1914 available patients were analysed for overall response. Among all patients with either indolent lymphoma or mantle cell lymphoma, 854 of 979 patients in the R‐chemo group responded to treatment, compared with 673 of 935 patients in the chemotherapy alone group, corresponding to a relative risk of a response for R‐chemo versus chemotherapy of 1.21 (95% CI = 1.16 to 1.27, Figure 10). The rate of complete responses was statistically significantly higher in patients treated with R‐chemo than in patients treated with chemotherapy alone (RR = 2.03; 95% CI = 1.71 to 2.40, Figure 11). In both analyses, there was heterogeneity among the trials (P < 0.001). Subgroup analyses of follicular lymphoma patients and mantle cell lymphoma patients also revealed that the R‐chemo arms had statistically significant higher overall response (Figure 12) and complete response rates (Figure 13) than the chemotherapy only arms.

10.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Overall Response, outcome: 3.1 Overall Response Total Group.

11.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Complete Response, outcome: 4.1 Complete Response Total Group.

12.

Forest plot of comparison: 3 Overall Response, outcome: 3.2 Overall Response FL vs MCL.

13.

Forest plot of comparison: 4 Complete Response, outcome: 4.2 Complete Response FL vs MCL.

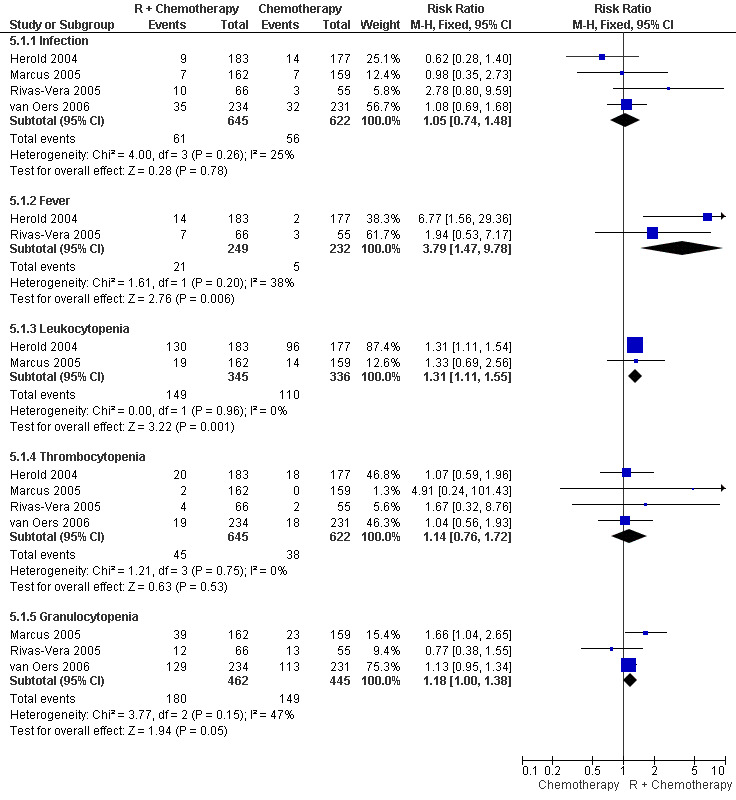

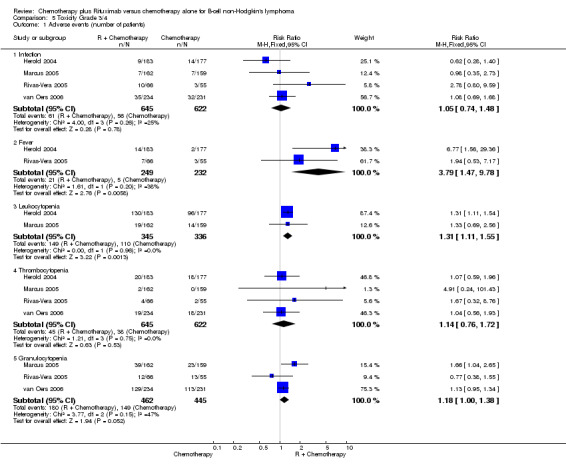

Toxicity We observed a lack of uniformity related to the reporting of treatment‐associated side effects described between the seven selected trials. Three trials (Hiddemann 2005, Lenz 2005, Forstpointner 2004) analysed toxicity over treatment cycles rather than recording absolute numbers of adverse events. Therefore, we could not include these three trials in the meta‐analysis of side effects. We performed a meta‐analysis of adverse events among the four trials that reported absolute numbers of adverse events (Marcus 2005, van Oers 2006, Rivas‐Vera 2005, Herold 2004). Overall, toxicity was described as mild to moderate for both treatment groups. The most often reported grade 3 and 4 adverse events were hematotoxicity (i.e., leukocytopenia, thrombocytopenia, or granulocytopenia), fever, and infection. The relative risk for developing fever or leukocytopenia was statistically significantly higher in patients treated with R‐chemo than in patients treated with chemotherapy alone (RR = 3.79; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.47 to 9.78 and RR = 1.31; 95% CI = 1.11 to 1.55, respectively, Figure 14). There was no evidence of a difference between treatment groups with respect to the risk of infection.

14.

Forest plot of comparison: 5 Toxicity Grade 3/4, outcome: 5.1 Adverse events (number of patients).

Discussion

Four major results emerged from this systematic review and meta‐analysis comparing R‐chemo with chemotherapy alone in a total of 1943 patients with follicular lymphoma (N = 1480), mantle cell lymphoma (N = 260), and other indolent lymphomas (N = 203).

First, concurrent treatment with R‐chemo improved overall survival in these patients compared with chemotherapy alone.

Second, patients treated with R‐chemo had statistically significantly better overall response, complete response, and disease control than patients treated with chemotherapy alone.

Third, subgroup analyses revealed statistically significant and robust data for improved overall response, complete response, disease control, and overall survival in patients with follicular lymphoma; the data were less convincing for mantle cell lymphoma because of heterogeneity among the trials.

Fourth, patients treated with R‐chemo had statistically significantly more leukocytopenia and fever than patients treated with chemotherapy alone, but there were no evidence of a difference in the frequencies of infections or thrombocytopenia between the groups.

To our knowledge, this comprehensive evaluation is the first meta‐analysis to demonstrate that R‐chemo improves overall survival in patients with advanced‐stage indolent and mantle cell lymphomas compared with chemotherapy alone. There are two possible explanations for the survival advantage of R‐chemo: patients treated with R‐chemo may have higher initial response rates and/or prolonged disease control compared with patients treated with chemotherapy alone. The efficacy of rituximab as single‐agent therapy was originally demonstrated in a pivotal study (McLaughlin 1998) that included 166 patients with refractory or relapsed indolent B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma; the overall response rate was 48%. Early preclinical data suggested that rituximab potentiates the sensitivity of tumour cells to cytotoxic drugs (Demidem 1997).

The antilymphoma activity of R‐chemo reflects their different modes of action and the ability of the antibody to modify molecular signaling pathways. This latter effect is associated with decreased expression of the antiapoptotic gene products, Bcl‐2 and Bcl‐xL, and the sensitization of drug‐resistant B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphoma cells to chemotherapy (Jazirehi 2005, Jazirehi 2005a, Bonavida 2005). However, the contribution of these mechanisms to the cytoxicity of rituximab and the in vivo relevance of these pathways in patients with follicular or mantle cell lymphoma is unclear. One of the first multicenter phase II trials to use R‐CHOP in patients with indolent lymphoma reported an overall response rate of 100% of all assessable patients and a complete response rate of 63% (Czuczman 1999). A recent update (Czuczman 2004) of this trial reported a median time to progression of 82.3 months and a duration of response of 83.5 months. In this trial, of eight patients who were Bcl‐2 positive at baseline, seven became Bcl‐2 negative, and three of the seven remained Bcl‐2 negative and in ongoing remission at 85, 98, and 99 months. To date, the most comprehensive summary of prospective clinical trials evaluating R‐chemo has been provided by the Hematology Disease Site Group (Imrie 2005). Their systematic review, which included seven randomised controlled trials, suggested that R‐chemo should be used in previously untreated and treated patients with follicular or other indolent B‐cell non‐Hodgkin lymphomas.

This recommendation was based on the balance between the risks of toxicity associated with rituximab and the benefits of delaying recurrent disease and the toxicity associated with re‐treatment. However, the trials included in that systematic review did not show statistically significant improved overall survival for patients with follicular and other indolent lymphomas, and a meta‐analysis was not performed. Our study has several limitations. First, the studies included in this analysis offered a variety of chemotherapy regimens, such as CHOP, CNOP, FCM, CVP, and MCP. The number of cycles scheduled applied ranged from four to eight, depending on the application of additional consolidation treatment. Options ranged from no adjuvant treatment to high‐dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. Therefore, with the currently available data, we cannot comment about which chemotherapy regimen is the best to combine with rituximab or about the optimal number of cycles needed to treat patients with indolent lymphoma. Second, although two trials (Marcus 2005, Hiddemann 2005) included in this analysis showed that the addition of rituximab to chemotherapy reduced the risk of disease progression in both low‐ and high‐risk patients, the data were insufficient to perform subgroup analyses on the basis of prognostic scores and biologic parameters (Solal‐Celigny 2004, Montoto 2003). Third, only three randomised controlled studies (Lenz 2005, Forstpointner 2004, Herold 2004) included patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Although we found that mantle cell lymphoma patients who were treated with R‐chemo had better overall survival, disease control, and overall response than patients treated with chemotherapy alone, the evidence for improved overall survival was less reliable than that for patients with follicular lymphoma because of the statistically significant heterogeneity among the analysed mantle cell lymphoma trials. This heterogeneity was caused mainly by the study of Forstpointner 2004, which included relapsed or refractory patients with mantle cell lymphoma, whereas the two other studies enrolled untreated patients only. There is a clear need for more prospective randomised trials in patients with advanced indolent lymphoma, with separated and adequately powered trials for untreated patients and patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. These trials should focus on the impact of rituximab in different risk groups and on the intensity of chemotherapy needed for favourable low‐risk patients, as is the ongoing PRIMA study from the Group d'Etudes de Lymphomes de L'Adulte, which is evaluating the role of maintenance rituximab in first‐line therapy. The impact of maintenance treatment with rituximab on overall survival, which was not evaluated in this analysis, is one of the most important open questions for patients with indolent non‐Hodgkin lymphoma. Recent randomised trials performed by the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) and by the EORTC demonstrated the superiority of rituximab maintenance after immunochemotherapy (van Oers 2006, Dreyling 2006) and after chemotherapy (van Oers 2006) compared with observation alone. However, the present review analysed trials conducted at a time of the rituximab era, when rituximab use was restricted to patients with relapsed disease. Therefore, the difference in overall survival between patients treated initially with immunochemotherapy or chemotherapy alone followed by maintenance therapy with rituximab might be smaller in current and future practice. There is also a need for additional randomised controlled trials in patients with mantle cell lymphoma to test the addition of rituximab to more intense chemotherapy regimens, such as dexamethasone, high‐dose cytarabine, and cisplatin or hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and dexamethasone followed by stem cell transplantation, or rituximab in combination with other new treatment drugs. In conclusion, this meta‐analysis demonstrated that, in patients with indolent or mantle cell lymphoma, R‐chemo is superior to chemotherapy alone with respect to remission induction, progression‐free survival, and overall survival. Therefore, concomitant treatment with rituximab and standard chemotherapy regimens should be considered the standard of care for patients with indolent and mantle cell lymphomas who require therapy and for patients with follicular lymphoma.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This systematic review and meta‐analysis specifically focus on clinically relevant endpoints such as event free survival and overall survival. We think that this manuscript is timely and relevant to the reader in this field since it adds important information to the ongoing discussion on the impact of rituximab on overall survival in patients with indolent lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. Our data demonstrate that combined immunochemotherapy significantly improves overall survival in patients with indolent lymphoma compared to chemotherapy alone. Thus we conclude that concomitant application of rituximab with standard chemotherapy regimen should be considered standard in patients with indolent lymphoma requiring therapy. From our view these results could lead to a major change in the treatment strategies of patients with indolent lymphoma.

Implications for research.

With this review there is evidence for improved survival for concomitant application of rituximab to a standard chemotherapy regimen in patients with indolent lymphoma. From our view future studies should focus on the following points:

Which standard chemotherapy should be used in combination with Rituximab

Influence of clinical and biologic prognostic markers after R‐chemotherapy. What is similar and what is different

Understanding rituximab efficacy and resistance

Role of rituximab in treatment of progressive disease

Mechanism of rituximab in combination with chemotherapy

Role of Pharmacokinetic, pharmacogenomics in the treatment with R‐chemo

Role of subsequent therapy with rituximab after R‐chemo

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 15 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Acknowledgements

We thank all authors and investigators who provided us with additional information. We thank the editors of and the consumers of the Cochrane Hematological Malignancies Group for strong support. The CHMG is funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), Grant application No.: 01GH501 and gets additional funding by "Köln Fortune" the funding programme from the medical faculty University of Cologne.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

#1 ‐ #36 Randomised controlled trials search filter [Dickersin 1994]

#37 IDEC* #38 Ritux* #39 anti‐CD20* #40 "Antigens, CD20" [MESH] #41 Mabth* #42 monocl* near antibo* #43 "Antibodies, Monoclonal" [MESH] #44 #37 OR #38 OR #39 OR #40 OR #41 OR #42 OR #43

#45 lymphom* #46 non‐hodgkin* #47 nonhodgkin* #48 NHL* #49 hematol* near malign* (note: the keywords haematol* near malig* did not indicate a hit) #50 bcell* #51 b‐cell* #52 "lymphoma" [MESH] #53 #45 OR #46 OR #47 OR #48 OR #49 OR #50 OR #51 OR #52

#55 #36 AND #44 AND #53

Appendix 2. EMBASE search strategy

#1 Clinical trial #2 Randomized controlled trial #3 Randomization #4 single blind procedure #5 double blind procedure #6 crossover procedure #7 Placebo #8 randomi?ed controlled trial? #9 rct #10 random allocation #11 randomly allocated #12 allocated randomly #13 single blind? #14 double blind? #15 (treble or triple) blind? #16 placebo? #17 prospective study? #18 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17

#19 IDEC? #20 Ritux? #21 ?cd20? #22 mabth? #23 monocl? antibo? #24 #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23

#25 lymphom? #26 non?hodgkin? #27 nhl? #28 h?ematol? malig? #29 bcell? #30 b?cell? #31 #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 #32 #18 AND #24 AND #31

Appendix 3. LILAC search strategy

#1 ‐ #36 Randomised controlled trials search filter Castro 1999 (see at www.geocities.com/otavioclark/lilacs.htm the link for the article) #37 IDEC$ #38 Ritux$ #39 anti‐CD20$ #40 Antigen$ #41 Mabth$ #42 Anticorp$ Monoclo$ #43 #37 OR #38 OR #39 OR #40 OR #41 OR #42

#45 lymphom$ OR linfom$ #46 non‐hodgkin$ OR N$o Hodgkin$ OR n$o‐Hodgkin$ #47 nonhodgkin$ #48 NHL$ #49 hematol$ malign$ OR Neopl$ Hematol$ #50 bcel$ OR Celu$ B #51 b‐cell$ #52 #45 OR #46 OR #47 OR #48 OR #49 OR #50 OR #51 #53 #36 AND #44 AND #52

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Overall survival.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival Total group | 7 | 1943 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.65 [0.54, 0.78] |

| 2 Overall survival FL vs MCL | 6 | 1740 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.63 [0.51, 0.77] |

| 2.1 Follicular lymphoma | 5 | 1480 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.63 [0.51, 0.79] |

| 2.2 Mantlecell lymphoma | 3 | 260 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.60 [0.37, 0.98] |

| 3 Sensitivity: attrition bias | 7 | 1943 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.65 [0.54, 0.78] |

| 3.1 Less than 10% excluded from analysis | 5 | 1694 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.68 [0.55, 0.83] |

| 3.2 More than 10% excluded from analysis | 2 | 249 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.50 [0.30, 0.83] |

| 4 Overall survival_Doxorubicin vs Mitoxantrone | 6 | 1622 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.64 [0.52, 0.79] |

| 4.1 Doxorubicin based regimen | 3 | 1015 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.70 [0.54, 0.91] |

| 4.2 Mitoxantrone based regimen | 3 | 607 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.56 [0.40, 0.77] |

| 5 Overall survival untreated vs treated patients | 7 | 1943 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.65 [0.54, 0.78] |

| 5.1 Untreated patients | 5 | 1350 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.66 [0.52, 0.84] |

| 5.2 Treated patients | 2 | 593 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.63 [0.46, 0.86] |

| 6 Overall survival_Anthracylin vs no‐Anthracylin treatment | 7 | 1943 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.65 [0.54, 0.78] |

| 6.1 Anthracyclin based regimen | 6 | 1622 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.64 [0.52, 0.79] |

| 6.2 No anthracylin based regimen | 1 | 321 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.70 [0.40, 1.23] |

| 7 Overall survival_Full Text vs Abstract Publication | 7 | 1943 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.65 [0.54, 0.78] |

| 7.1 Full‐text | 5 | 1464 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.65 [0.52, 0.81] |

| 7.2 Abstract Form | 2 | 479 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.64 [0.43, 0.94] |

| 8 Overall survival_Alloc. concealment | 7 | 1943 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.65 [0.54, 0.78] |

| 8.1 Adaequate | 6 | 1822 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.64 [0.53, 0.78] |

| 8.2 Not adaequate | 1 | 121 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.96 [0.32, 2.91] |

| 9 Overall Survival _with or without second randomisation | 7 | 1943 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.65 [0.54, 0.78] |

| 9.1 No second randomisation | 3 | 800 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.66 [0.48, 0.91] |

| 9.2 Second randomisation | 4 | 1143 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.64 [0.51, 0.81] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Overall survival, Outcome 1 Overall survival Total group.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Overall survival, Outcome 2 Overall survival FL vs MCL.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Overall survival, Outcome 3 Sensitivity: attrition bias.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Overall survival, Outcome 4 Overall survival_Doxorubicin vs Mitoxantrone.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Overall survival, Outcome 5 Overall survival untreated vs treated patients.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Overall survival, Outcome 6 Overall survival_Anthracylin vs no‐Anthracylin treatment.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Overall survival, Outcome 7 Overall survival_Full Text vs Abstract Publication.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Overall survival, Outcome 8 Overall survival_Alloc. concealment.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Overall survival, Outcome 9 Overall Survival _with or without second randomisation.

Comparison 2. Disease Control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 FFS Total group | 7 | 1913 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.55, 0.71] |

| 2 FFS_FL vs MCL | 5 | 1537 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.58 [0.50, 0.67] |

| 2.1 Follicular lymphoma | 4 | 1415 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.58 [0.50, 0.68] |

| 2.2 Mantlecell lymphoma | 1 | 122 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.54 [0.33, 0.88] |

| 3 FFS_Sensitivity: attrition bias | 7 | 1913 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.55, 0.71] |

| 3.1 Less than 10% excluded from analysis | 5 | 1694 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.60 [0.52, 0.69] |

| 3.2 More than 10% excluded from analysis | 2 | 219 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.76 [0.55, 1.06] |

| 4 Disease control_Doxorubicin vs Mitoxantrone | 6 | 1592 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.54, 0.72] |

| 4.1 Doxorubicin based regimen | 3 | 1015 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.60 [0.49, 0.72] |

| 4.2 Mitoxantrone based regimen | 3 | 577 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.66 [0.53, 0.84] |

| 5 Disease control_untreated vs treated patients | 7 | 1913 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.55, 0.71] |

| 5.1 Untreated patients | 5 | 1320 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.61 [0.52, 0.72] |

| 5.2 Treated patients | 2 | 593 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.65 [0.52, 0.80] |

| 6 Disease control_Anthracylin vs no‐Anthracylin treatment | 7 | 1913 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.55, 0.71] |

| 6.1 Anthracyclin based regimen | 6 | 1592 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.54, 0.72] |

| 6.2 No anthracylin based regimen | 1 | 321 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.47, 0.83] |

| 7 Disease control_Full text vs abstract publication | 7 | 1913 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.55, 0.71] |

| 7.1 Full ‐Text | 5 | 1464 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.61 [0.52, 0.71] |

| 7.2 Abstract form | 2 | 449 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.68 [0.52, 0.89] |

| 8 FFS_Sensitivity: Alloc. concealment | 7 | 1913 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.55, 0.71] |

| 8.1 Allocation concealment adaequate | 6 | 1822 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.60 [0.53, 0.69] |

| 8.2 Not adaequate | 1 | 91 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.98 [0.59, 1.61] |

| 9 FFS_Endpoints according to start of measurement | 6 | 1785 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.62 [0.55, 0.72] |

| 9.1 Start of treatment | 5 | 1427 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.63 [0.54, 0.74] |

| 9.2 End of treatment | 1 | 358 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.59 [0.43, 0.81] |

| 10 FFS_Endpoints TTP, EFS, TTF, PFS | 6 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 Time to progression | 2 | 412 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.69 [0.54, 0.89] |

| 10.2 Progression free survival | 2 | 587 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.63 [0.51, 0.78] |

| 10.3 Time to treatment failure | 2 | 550 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.51 [0.37, 0.70] |

| 10.4 Event free survival | 1 | 201 | Peto Odds Ratio (95% CI) | 0.41 [0.26, 0.64] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 1 FFS Total group.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 2 FFS_FL vs MCL.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 3 FFS_Sensitivity: attrition bias.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 4 Disease control_Doxorubicin vs Mitoxantrone.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 5 Disease control_untreated vs treated patients.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 6 Disease control_Anthracylin vs no‐Anthracylin treatment.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 7 Disease control_Full text vs abstract publication.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 8 FFS_Sensitivity: Alloc. concealment.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 9 FFS_Endpoints according to start of measurement.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Disease Control, Outcome 10 FFS_Endpoints TTP, EFS, TTF, PFS.

Comparison 3. Overall Response.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall Response Total Group | 7 | 1914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.16, 1.27] |

| 2 Overall Response FL vs MCL | 7 | 1830 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [1.14, 1.24] |

| 2.1 follicular | 6 | 1570 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.19 [1.13, 1.24] |

| 2.2 Mantle cell | 3 | 260 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.05, 1.42] |

| 3 Sensitivity: attrition bias | 7 | 1914 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.76 [2.17, 3.51] |

| 3.1 Less than 10% excluded from analysis | 5 | 1693 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.88 [2.22, 3.74] |

| 3.2 More than 10% excluded from analysis | 2 | 221 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.10 [1.10, 4.01] |

| 4 Overall Response_Doxorubicin vs Mitoxantrone | 6 | 1593 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.63 [1.99, 3.46] |

| 4.1 Doxorubicin based regimen | 3 | 1014 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.58 [1.76, 3.76] |

| 4.2 Mitoxantrone based regimen | 3 | 579 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.69 [1.80, 4.03] |

| 5 Overall Response_untreated vs treated patients | 7 | 1914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.16, 1.27] |

| 5.1 Untreated patients | 5 | 1319 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.15, 1.28] |

| 5.2 Treated patients | 2 | 595 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [1.10, 1.32] |

| 6 Overall response_Anthracyclin vs no‐Anthracyclin treatment | 7 | 1914 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.76 [2.17, 3.51] |

| 6.1 Anthracyclin based regimen | 6 | 1593 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.63 [1.99, 3.46] |

| 6.2 No Anthracyclin based regimen | 1 | 321 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.24 [1.96, 5.35] |

| 7 Overall Response_Full text vs Abstract publication | 7 | 1914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.16, 1.27] |

| 7.1 Full Text | 5 | 1465 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [1.14, 1.26] |

| 7.2 Abstract form | 2 | 449 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [1.12, 1.38] |

| 8 Overall Response Allocation concealment | 7 | 1914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [1.16, 1.27] |

| 8.1 Adaequate | 6 | 1823 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.16, 1.28] |

| 8.2 Not adaequate | 1 | 91 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.90, 1.23] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Overall Response, Outcome 1 Overall Response Total Group.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Overall Response, Outcome 2 Overall Response FL vs MCL.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Overall Response, Outcome 3 Sensitivity: attrition bias.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Overall Response, Outcome 4 Overall Response_Doxorubicin vs Mitoxantrone.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Overall Response, Outcome 5 Overall Response_untreated vs treated patients.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Overall Response, Outcome 6 Overall response_Anthracyclin vs no‐Anthracyclin treatment.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Overall Response, Outcome 7 Overall Response_Full text vs Abstract publication.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Overall Response, Outcome 8 Overall Response Allocation concealment.

Comparison 4. Complete Response.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Complete Response Total Group | 7 | 1914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [1.71, 2.40] |

| 2 Complete Response FL vs MCL | 6 | 2043 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.26 [1.89, 2.71] |

| 2.1 Follicula lymphoma | 5 | 1701 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.16 [1.77, 2.63] |

| 2.2 Mantle cell lymphoma | 3 | 342 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.90 [1.80, 4.67] |

| 3 Complete Response_Doxorubicine vs Mitoxantrone | 6 | 1593 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.85 [1.55, 2.21] |

| 3.1 Mitixantrone based regimen | 3 | 579 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.02 [1.58, 2.59] |

| 3.2 Doxorubicine based regimen | 3 | 1014 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.71 [1.33, 2.21] |

| 4 Complete Response_anthracycline vs no anthracyclin treatment | 7 | 1914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [1.71, 2.40] |

| 4.1 Anthracyclin based regimen | 6 | 1593 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.85 [1.55, 2.21] |

| 4.2 No Anthracyclin based regimen | 1 | 321 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.01 [2.22, 7.25] |

| 5 Complete Response _untreated vs treated patients | 7 | 1914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [1.71, 2.40] |

| 5.1 Complete remission untreated patients | 5 | 1319 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.03 [1.66, 2.48] |

| 5.2 Complete remission_treated patients | 2 | 595 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.01 [1.45, 2.77] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Complete Response, Outcome 1 Complete Response Total Group.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Complete Response, Outcome 2 Complete Response FL vs MCL.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Complete Response, Outcome 3 Complete Response_Doxorubicine vs Mitoxantrone.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Complete Response, Outcome 4 Complete Response_anthracycline vs no anthracyclin treatment.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Complete Response, Outcome 5 Complete Response _untreated vs treated patients.

Comparison 5. Toxicity Grade 3/4.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Adverse events (number of patients) | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Infection | 4 | 1267 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.74, 1.48] |

| 1.2 Fever | 2 | 481 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.79 [1.47, 9.78] |

| 1.3 Leukocytopenia | 2 | 681 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [1.11, 1.55] |

| 1.4 Thrombocytopenia | 4 | 1267 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.76, 1.72] |

| 1.5 Granulocytopenia | 3 | 907 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [1.00, 1.38] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Toxicity Grade 3/4, Outcome 1 Adverse events (number of patients).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Forstpointner 2004.

| Methods | Randomised Blind: No Withdrawls: Yes ITT: yes Placebo:No Funding: Deutsche Krebshilfe | |

| Participants | Relapsed or refractory indolent and mantle cell lymphoma | |

| Interventions | 4 x R‐FCM vs 4 x FCM | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival Progression free survival Complete Response Partial Response Toxicity | |

| Notes | Second randomisation for maintenance 4xRituximab month 3 and months 9 vs observation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Herold 2004.

| Methods | Randomised Blind: No Withdrawls: No ITT: yes Placebo:No Funding: pharmaceutical | |

| Participants | Untreated indolent and mantle cell lymphoma | |

| Interventions | 6 x R‐MCP vs 6 x MCP | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival Progression free survival Event free survival Complete Response Partial Response Toxicity | |

| Notes | Interferon maintenance therapy for follicular lymphoma | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Hiddemann 2005.

| Methods | Randomised Blind: No Withdrawls: No ITT: Deutsche Krebshilfe Placebo:No Funding: pharmaceutical | |

| Participants | Untreated indolent and mantle cell lymphoma | |

| Interventions | 6‐8 R‐CHOP vs 6‐8 CHOP | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival Time to treatment failure Complete Response Partial Response Toxicity | |

| Notes | Second randomisation for patients < 60 years for PBSCT vs Interferon maintenance and for patients > 60 years intensive interferon vs standard maintenance patients in CR after 4 cycles received only 6 cycles of therapy whereas all others received 8 cycles. Progressive disease were taken off study after 4 at any time | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Lenz 2005.

| Methods | Randomised Blind: No Withdrawls: Yes ITT: yes Placebo:No Funding: Deutsche Krebshilfe pharmaceutical | |

| Participants | Untreated mantle cell lymphoma | |

| Interventions | 6 x R‐CHOP vs 6 x CHOP | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival Progression free survival Time to treatment failure Complete Response Partial Response Toxicity | |

| Notes | Second randomisation for patients < 65 years for PBSCT vs Interferon maintenance plus 2 cycles of conventional chemotherapy and all patients > 65 years received interferon standard maintenance therapy | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Marcus 2005.

| Methods | Randomised Blind: No Withdrawls: Yes ITT: yes Placebo:No Funding: pharmaceutical | |

| Participants | Untreated indolent lymphoma | |

| Interventions | 8 x R‐CVP vs 8 x CVP | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival Progression free survival Duration of response Complete Response Partial Response | |

| Notes | Restaging were done after 4 cycles and patients with stable disease were taken off study | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Rivas‐Vera 2005.

| Methods | Randomised Blind: No Withdrawls: Yes ITT: yes Placebo:No Funding: not applicable | |

| Participants | Untreated indolent lymphoma | |

| Interventions | R‐CNOP vs CNOP vs R | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival Time to progressionOverall survival Time to progression Complete Response Partial Response Toxicity | |

| Notes | subgroups of indolent lymphoma are not specified. Three arm study. Patients with R only are not included in the meta‐analysis | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

van Oers 2006.

| Methods | Randomised Blind: No Withdrawls: Yes ITT: yes Placebo:No Funding: | |

| Participants | Relapsed or refractory indolent lymphoma | |

| Interventions | 6 x R‐CHOP vs 6 x CHOP | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival Time to progression Complete Response Partial Response Toxicity | |

| Notes | Second randomisation for maintenance therapy with rituximab every 2 month until 2 years vs observation | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Byrd JC | Comparison of concurrent vs sequential treatment with rituximab |

| Cohen 2002 | Rituximab Konsolidationtherapy |

| Czuczman | Non randomised study 6 x Rituximab + 6 x R‐CHOP |

| Czuczman M | Non randomised study 7 x Rituximab + 6 x Fludarabin |

| Doelken G | Study focused on rapid clearence of circulating lymphoma cells but had no outcome analysis |

| Ghielmeni M | Monotherapy R and maintenance rituximab |

| Gregory S | Konsoldiationtherapy with Rituximab |

| Hainsworth J | No identical chemotherapy and furthermore rituximab monotherapy as induction followed by R‐CVP or R‐CHOP |

| Hochster H | rituximab maintenance therapy |

| Huang J | Non randomised study 6 x R‐CHOP followed by 4 x rituximab every 6 months for 2 years |

| Jiang Y | Sequential vs concurrent therapy with rituximab 6 x R‐FND vs FND followed by 6 x R |

| Katakkar S | Non randomised study 6 x Rituximab weekly + CVP and maintenance therapy |

| Meckenstock G | Standard chemotherapy with rituximab vs high dose therapy with rituximab and no identical chemotherapy in both arms 6 x FMR vs 3 x R‐CHOP 2 x HAM/R and PBSCT |

| Pettengell | Rituximab maintenance therapy and ongoing trial |

| Rambaldi A | Treatment outcome was minimal residual disease |

| Rule S | Non randomised study and ongoing trial |

| Salles G | No identical chemotherapy schedule. 6 x R‐CHVP vs 12 x CVHP |

| Solal‐Celigny P | Rituximab monotherapy |

| Tobinai | Rituximab concurrent vs sequential 6 x R‐CHOP 6 x CHOP 6 x R |

| Vitolo | Rituximab consolidationtherapy |

| Witzig | Rituximab mono |

| Zinzani PL | Konsolidationtherapy with rituximab after 6 x Fludara + Mitoxantrone vs 6 x R‐CHOP. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

GELA Study.

| Trial name or title | |

| Methods | |

| Participants | |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | |

| Starting date | |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

Sonneveld.

| Trial name or title | Combination Chemotherapy Plus Filgrastim With or Without Rituximab in Treating Older Patients With Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma |

| Methods | |

| Participants | Adult Diffuse Large Cell Lymphoma Adult Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma Grade 3 Follicular Lymphoma Mantle Cell Lymphoma |

| Interventions | Compare the efficacy of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP), and filgrastim (G‐CSF) with or without rituximab on event‐free survival of elderly patients with intermediate or high‐risk non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma. |

| Outcomes | Compare the complete remission rate, overall survival, and disease‐free survival of patients treated with these regimens. Compare the toxicity of these regimens in these patients |

| Starting date | January 2002 |

| Contact information | Sponsored by: Commissie Voor Klinisch Toegepast Onderzoek Information provided by: National Cancer Institute (NCI) ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00028717 |

| Notes |

Contributions of authors

Holger Schulz: Conception and design, provision of study material, data extraction, analysis and interpretation, writing of review and final approval.

Thilo Kober: Protocol development, searching for trials, eligibility and quality assessment, data extraction and analysis, drafting and writing of final review

Julia Bohlius: Methodological advice, conception and design, provision of study material, data extraction, analysis and interpretation, writing of review and final approval.

Andreas Engert: Clinical and scientific advice, conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of review and final approval.

Marcel Reiser: Conception and design, analysis and interpretation, writing of review and final approval.

Nicole Skoetz: Conception and design, provision of study material, data extraction, analysis and interpretation, writing of review and final approval.

Martin Dreyling: provision of study material, data extraction, writing of review and final approval.

Michael Herold: provision of study material, writing of review and final approval.

Sven Trelle: Conception and design, methodological advice, data extraction, analysis and interpretation, writing of review and final approval.

Guido Schwarzer: Methodological advice, data analysis and interpretation, writing of review and final approval.

Michael Hallek: Clinical and scientific advice, writing of review and final approval.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Kompetence Network Malignant Lymphoma paid the salary for TK (1999‐2001), Germany.

External sources

The Editorial Base of CHMG is funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) FKZ : 01GH0501, Germany.

The Editorial Base gets additional funding by “Köln Fortune” the funding programme from the medical faculty University of Cologne, Germany.

Declarations of interest

Thilo Kober was up to March 2006 the co‐ordinator of the Cochrane Haematological Malignancies Group (CHMG) and was involved in the preparation of systematic reviews and other material for the Cochrane Library. Julia Bohlius is a medical officer and reviewer, Andreas Engert is the CHMG co‐ordinating editor and Holger Schulz is a medical officer and reviewer in the CHMG editorial base. All are or were involved in the preparation of systematic reviews. This protocol is not supported by the pharmaceutical industry or by any grant. J. Bohlius gave two presentations on erythropoiesis‐stimulating agents at Hoffmann‐La Roche & Co, the manufacturer of rituximab. M. Reiser, M. Herold, M. Dreyling, and M. Hallek have conducted research sponsored by Hoffmann‐La Roche & Co, the manufacturer of rituximab. M. Herold is a member of the Hoffmann‐La Roche & Co Speaker's bureau, and M. Dreyling has received a speaker's honorarium from Hoffmann‐La Roche & Co. M. Herold is a member of the Hoffmann‐La Roche & Co advisory board. .

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Forstpointner 2004 {published and unpublished data}

- Forstpointner R, Dreyling M, Repp R, Hermann S, Hanel A, Metzner B, et al. The addition of rituximab to a combination of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone (FCM) significantly increases the response rate and prolongs survival as compared with FCM alone in patients with relapsed and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low‐Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2004;104(10):3064‐3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Herold 2004 {published and unpublished data}

- Herold M, Pasold R, Srock S, Neser S, Niederwieser D, Neubauer A, et al. Results of a Prospective Randomised Open Label Phase III Study Comparing Rituximab Plus Mitoxantrone, Chlorambucile, Prednisolone Chemotherapy (R‐MCP) Versus MCP Alone in Untreated Advanced Indolent Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma (NHL) and Mantle‐Cell‐Lymphoma (MCL). ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2004; Vol. 104, issue 11:584.

Hiddemann 2005 {published data only}

- Hiddemann W, Kneba M, Dreyling M, Schmitz N, Lengfelder E, Schmits R, et al. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced‐stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low‐Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 2005;106(12):3725‐3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lenz 2005 {published data only}

- Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, Wormann B, Duhrsen U, Metzner B, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long‐term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). J Clin Oncol 2005;23(9):1984‐1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marcus 2005 {published data only}

- Marcus R, Imrie K, Belch A, Cunningham D, Flores E, Catalano J, et al. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first‐line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood 2005;105(4):1417‐1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rivas‐Vera 2005 {published data only}

- Rivas‐Vera S, Baez E, Sobrevilla‐Calvo P, Baltazar S, Tripp F, Vela J, et al. Is First Line Single Agent Rituximab the Best Treatment for Indolent Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma? Update of a Multicentric Study Comparing Rituximab vs CNOP vs Rituximab Plus CNOP. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2005; Vol. 106, issue 11:2431.

van Oers 2006 {published data only}

- Oers MH, Klasa R, Marcus RE, Wolf M, Kimby E, Gascoyne RD, Jack A, Van't Veer M, Vranovsky A, Holte H, Glabbeke M, Teodorovic I, Rozewicz C, Hagenbeek A. Rituximab maintenance improves clinical outcome of relapsed/resistant follicular non‐Hodgkin lymphoma in patients both with and without rituximab during induction: results of a prospective randomized phase 3 intergroup trial.. Blood 2006;108 (10):3295‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Byrd JC {published data only}

- Byrd JC, Peterson BL, Morrison VA, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of fludarabine with concurrent versus sequential treatment with rituximab in symptomatic, untreated patients with B‐cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 9712 (CALGB 9712). Blood 2003;101:6‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cohen 2002 {published data only}

- Cohen, et al. Results of a phase II study employing a combination of Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide and Rituximab (FCR) as a primary therapy for patiens with advanced follicular lymphoma (FL): the israel cooperative group. Blood 2002;100, No 11:abstract 1393. [Google Scholar]

Czuczman {published data only}

- Czuczman MS, Koryzna A, Mohr A, Stewart C, Donohue K, Blumenson L, Bernstein ZP, McCarthy P, Alam A, Hernandez‐Ilizaliturri F, Skipper M, Brown K, Chanan‐Khan A, Klippenstein D, Loud P, Rock MK, Benyunes M, Grillo‐Lopez A, Bernstein SH. Rituximab in combination with fludarabine chemotherapy in low‐grade or follicular lymphoma.. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Feb 1;23(4):694‐704 2005;Feb 1; 23 (4):694‐704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Czuczman M {published data only}

- Czuczman MS, Weaver R, Alkuzweny B, Berlfein J, Grillo‐Lopez AJ. Prolonged clinical and molecular remission in patients with low‐grade or follicular non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma treated with rituximab plus CHOP chemotherapy: 9‐year follow‐up.. J Clin Oncol 2004;Dec 1; 22 (23):4711‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Doelken G {published data only}

- Doelken G, Schueler F, Kiefer T, Herold M, Hirt C. Rapid clearance of circulating lymphoma cells from peripheral blood of follicular lymphoma patients treated with chemotherapy and rituximab as compared to patients treated with chemotherapy alone. Hematology 2002;3 Suppl. 1:278. [Google Scholar]

Ghielmeni M {published data only}

- Ghielmini M, Schmitz SF, Cogliatti SB, Pichert G, Hummerjohann J, Waltzer U, Fey MF, Betticher DC, Martinelli G, Peccatori F, Hess U, Zucca E, Stupp R, Kovacsovics T, Helg C, Lohri A, Bargetzi M, Vorobiof D, Cerny. Prolonged treatment with rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma significantly increases event‐free survival and response duration compared with the standard weekly x 4 schedule.. Blood 2004;103 (12):4416‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gregory S {published data only}

- Gregory SA. A phase II study of ludarabine and mitoxantrone followed by anti‐CD 20 monoclonal antibody in the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed, advanced low grade non Hodgkin´s lymphoma (LGNHL): interim results. Blood 2003;102, 11, Part 1, 412a:abstract 1499. [Google Scholar]

Hainsworth J {published data only}

- Hainsworth JD, Litchy S, Shaffer DW, Lackey VL, Grimaldi M, Greco FA. Maximizing therapeutic benefit of rituximab: maintenance therapy versus re‐treatment at progression in patients with indolent non‐Hodgkin's lymphoma‐‐a randomized phase II trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network.. J Clin Oncol 2005;23 (6):1088‐95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hochster H {published data only}

- H. S. Hochster, E. Weller, T. Ryan, T. M. Habermann, R. Gascoyne, S. R. Frankel, S. J. Horning. Results of E1496: A phase III trial of CVP with or without maintenance rituximab in advanced indolent lymphoma (NHL). ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings (Post‐Meeting Edition). abstract 6502 Vol 22, No 14S (July 15 Supplement), 2004: 6502. 2004.

Huang J {published data only}

- Jane E. Huang, Lowell Hart, Jonathon Polikoff, Virginia Langmuir, Fan Zhang, Louis Fehrenbacher. Rituximab Plus CHOP Followed by Maintenance Rituximab as Initial Therapy for Advanced Stage Indolent Non‐Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL); Initial Results of Induction Therapy in a Phase II Study.. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts), abstract: 4615.. 2004.

Jiang Y {published data only}

- Yunfang Jiang, Peter McLaughlin, Athanasios Thomaides, David Simons, Ajay Sehgal, Thomas Sneed, Ofelia Mesina, Marilyn Clemons, Ana Ayals, Georgios Z. Rassidakis, L. Jeffrey Mederios, Andreas H. Sarris, Frederic Gilles, Fernando Cabanillas, Andre Goy. Quantification and Monitoring of the t(14;18) Translocation Copy Number by Real‐Time PCR in Patients with Follicular Lymphoma Treated with FND Plus Concurrent or Delayed Rituximab. Amercian Society of Hematology : abstract 1444. 2003.

Katakkar S {published data only}

- Suresh B. Katakkar. A Combination of Rituximab with Chemotherapy in Low Grade Lymphoma. Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) abstract 4647. 2004.

Meckenstock G {published data only}

- G. Meckenstock, S. Martin, G. Kobbe, P. Möller, M. Bentz, C. Aul, A. Raghavachar, A. Wehmeier, D. Braumann, C. Losem, A. Nusch, R. Kronenwett, H. Döhner, R. Haas. Firstline treatment of advanced follicular lymphoma comparing fludarabine/Mitoxantrone and high‐dose chemotherapy, each combined with CD20‐antibody rituximab. Onkologie; abstract 869. 2003.

Pettengell {published data only}

- Pettengell R, Linch DC. Phase III Randomized Study of Rituximab Purging and Maintenance With Perupheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients With Relapsed or Resistant Follicular Non‐Hodgkin's Lymphoma Undergoing High‐Dose Chemotherapy. Ongoing Clinical Trial. [Ref.: 14674]

Rambaldi A {published data only}

- Rambaldi A. Long term improvement of clinical outcomes of follicular lymphoma patients achieving a molecular response after sequential CHOP and rituximab treatment: predictive value of real time quantitative PCR to identify responding patients. Blood 2003;102, No 11, Part 1, 409a:abstract 1487. [Google Scholar]

Rule S {published data only}

- Rule S, Seymour J. Phase II Randomized Study of Fludarabine and Cyclophopshamide With or Without Rituximab inPatients With Previously Untreated Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Ongoing Trial. [Ref: 14665]

Salles G {published data only}

- Gilles Andre Salles, Charles Foussard, Mounier Nicolas, Morschhauser Franck, Doyen Chantal, Lamy Thierry, Haioun Corinne, Brice Pauline, Bouabdallah Reda, Rossi Jean‐François, Audhuy Bruno, Fermé Christophe, Mahe Béatrice, Feugier Pierre, Sebban Catherine, Colombat Philippe, Xerri Luc. Rituximab Added {alpha}IFN+CHVP Improves the Outcome of Follicular Lymphoma Patients with a High Tumor Burden: to First Analysis of the GELA‐GOELAMS FL‐2000 Randomized Trial in 359 Patients.. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2004; Vol. 104:160.

Solal‐Celigny P {published data only}

- Philippe Solal‐Celigny, Gilles Andre Salles, Nicole Brousse, Patricia Franchi‐Rezgui, Pierre Soubeyran, Vincent Delwail, Eric Deconinck, Corinne Haioun, Charles Foussard, Catherine Sebban, Herve Tilly, Noel‐Jean Milpied, Francois Boue, Jean‐Michel Karsenti, Pierre Lederlin, Albert Najman, Catherine Thieblemont, Franck Morschhauser, Nathalie Berriot‐Varoqueaux, Loic Bergougnoux, Philippe Colombat. Single 4‐Dose Rituximab Treatment for Low‐Tumor Burden Follicular Lymphoma (FL): Survival Analyses with a Follow‐Up (F/Up) of at Least 5 Years.. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 585. 2004.