ABSTRACT

Candida auris is an emerging yeast pathogen with a remarkable ability to develop antifungal resistance, in particular to fluconazole and other azoles. Azole resistance in C. auris was shown to result from different mechanisms, such as mutations in the target gene ERG11 or gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in the transcription factor TAC1b and overexpression of the drug transporter Cdr1. The roles of the transcription factor Mrr1 and of the drug transporter Mdr1 in azole resistance is still unclear. Previous works showed that deletion of MRR1 or MDR1 had no or little impact on azole susceptibility of C. auris. However, an amino acid substitution in Mrr1 (N647T) was identified in most C. auris isolates of clade III that were fluconazole resistant. This study aimed at investigating the role of the transcription factor Mrr1 in azole resistance of C. auris. While the MRR1N647T mutation was always concomitant to hot spot ERG11 mutations, MRR1 deletion in one of these isolates only resulted in a modest decrease of azole MICs. However, introduction of the MRR1N647T mutation in an azole-susceptible C. auris isolate from another clade with wild-type MRR1 and ERG11 alleles resulted in significant increase of fluconazole and voriconazole MICs. We demonstrated that this MRR1 mutation resulted in reduced azole susceptibility via upregulation of the drug transporter MDR1 and not CDR1. In conclusion, this work demonstrates that the Mrr1-Mdr1 axis may contribute to C. auris azole resistance by mechanisms that are independent from ERG11 mutations and from CDR1 upregulation.

KEYWORDS: drug transporters, efflux pumps, transcription factors, fluconazole, voriconazole

INTRODUCTION

The yeast pathogen Candida auris has emerged as a novel cause of invasive candidiasis (1, 2). Since the first report of this new species in Japan in 2009 (3), several clades of C. auris have emerged simultaneously in different geographical regions: clade I (South Asia), clade II (East Asia), clade III (South Africa), clade IV (South America), and clade V (Iran) (1, 2, 4). C. auris represents a public health threat because of its ability to cause nosocomial outbreaks and to develop resistance to all three currently approved antifungal drug classes (5–7). Notably, acquired resistance to fluconazole is a hallmark of most clinical C. auris isolates (2). Mechanisms of azole resistance in C. auris are close to those previously identified in other relevant pathogenic Candida spp., including mutations in the azole target gene (ERG11) (8, 9) and gain-of-function (GOF) mutations in transcription factor genes (e.g., TAC1, MRR1) resulting in overexpression of efflux pumps of the ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter family, such as Cdr1 (10), or of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), such as Mdr1 (11). Several amino acid substitutions in hot spot regions of Erg11 have been associated with azole resistance in C. auris including V125A, F126L, Y132F, K143R, and F444L (2, 12–14). The amino acid substitutions A640V and S611P in Tac1b have also been identified as triggers of azole resistance of C. auris (14, 15). However, the roles of the transcription factor Mrr1 and of the Mdr1 transporter in C. auris are not yet fully understood. Deletion of MDR1 or MRR1 in isolates of clades I or III only resulted in a modest impact on azole resistance (16, 17). An amino acid substitution N647T in Mrr1 (resulting from the non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphism A1940C in the MRR1 gene) has been identified among most isolates of C. auris clade III that were fluconazole resistant (18, 19). Because concomitant Erg11 amino acid substitutions (V125A and F126L) were present in these isolates (18), the actual role of this Mrr1 N647T amino acid substitution in azole resistance was not clearly demonstrated.

In this work, we addressed the role of Mrr1 in the azole resistance of C. auris and we demonstrated that the N647T amino-acid substitution in Mrr1 was a GOF mutation capable of reducing azole susceptibility to the short-tailed azoles (fluconazole and voriconazole) via upregulation of MDR1.

RESULTS

The N647T amino acid substitution in Mrr1 reduces azole susceptibility in C. auris.

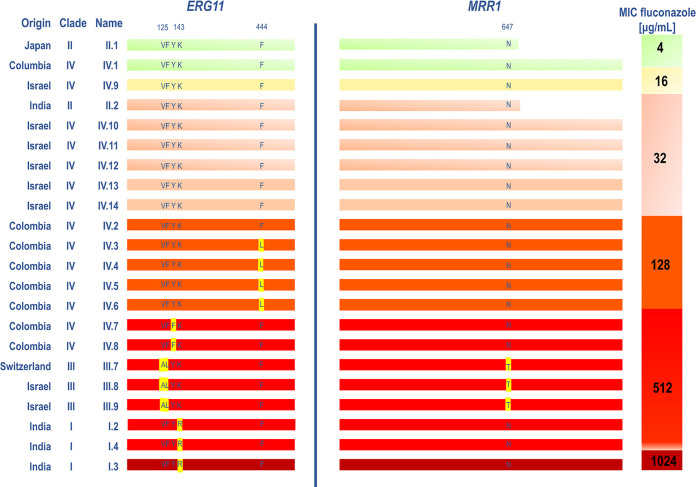

To investigate the role of Mrr1 in the azole resistance of C. auris, we first sequenced the MRR1 gene in a collection of 22 C. auris isolates representing clades I to IV (Fig. 1). The two isolates of clade II had a truncated Mrr1 protein (704 amino acids instead of 1,133) resulting from two deletions (2001C, 2001A) with a stop codon (TGA) at position 2,113 to 2,115. These isolates exhibited relatively lower fluconazole MIC values (≤32 μg/mL) compared with the other isolates. As reported in previous publications (18, 19), a single non-synonymous nucleotide polymorphism (A1940C) resulting in the amino acid substitution N647T (further referred as MRR1N647T mutation) was observed in all three isolates of clade III (isolates III.7, III.8, and III.9). These isolates exhibited a high level of resistance to fluconazole (MIC [MIC] >256 μg/mL) and concomitant amino acid substitutions at positions V125A and F126L in Erg11 (further referred as ERG11V125A,F126L mutations), which is common finding for this clade (18, 19). The MRR1N647T mutation was not observed in any of the clinical isolates from the other clades (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

Representation of the amino acid sequences of ERG11 and MRR1 of 22 C. auris isolates. The amino acid sequences of the isolates of each clade are compared with a reference sequence of a fluconazole-susceptible isolate of the same clade: B8441 (clade I) (30), II.1 (clade II), B12037 (clade III) (31), and IV.1 (clade IV). The non-synonymous amino acid substitutions are marked in yellow. Color bars indicate different fluconazole susceptibility levels. The origin of the different isolates have been described in a previous publication (32).

To further define the role of Mrr1 and in particular of the MRR1N647T mutation in azole resistance of C. auris, we deleted MRR1 in an azole-resistant strain of clade III containing the MRR1N647T mutation (isolate III.8, Fig. 1) and in an azole-resistant strain of another clade that did not harbor the MRR1N647T mutation or any other mutation in ERG11 (isolate IV.2, Fig. 1). MRR1 deletion had no impact on azole susceptibility of the IV.2 mrr1WTΔ strain (Table 1). However, we observed a modest (2-fold) MIC decrease of the short tailed azoles (fluconazole and voriconazole) in the III.8 mrr1N647TΔ strain, while MICs of the long tailed azoles (itraconazole and isavuconazole) were unchanged (Table 1). We concluded that the MRR1N647T mutation may play a role in azole resistance; however, this effect could be attenuated by the presence of the concomitant ERG11V125A,F126L mutations.

TABLE 1.

MICs values of the parental strains and their derived mutant strains

| Strains | Fluconazole MIC [μg/mL] | Voriconazole MIC [μg/mL] | Isavuconazole MIC [μg/mL] | Itraconazole MIC [μg/mL] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| III.8 | 512 | 2 | 0.5 | 4 |

| III.8 mrr1N647TΔ | 256 | 1 | 0.5 | 4 |

| IV.2 | 128 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| IV.2 mrr1WTΔ | 128 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| IV.1 | 4 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 1 |

| IV.1 MRR1N647T | 16 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 1 |

| IV.1 mdr1Δ | 4 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 1 |

| IV.1 mdr1Δ/MRR1N647T | 4 | 0.06 | 0.125 | 1 |

| IV.1 cdr1Δ | 1 | 0.015 | <0.03 | 0.25 |

| IV.1 cdr1Δ/MRR1N647T | 8 | 0.06 | <0.03 | 0.25 |

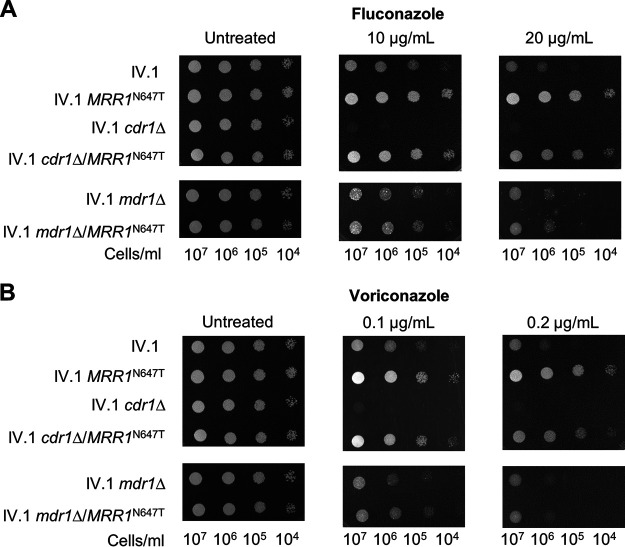

In order to demonstrate the role of the MRR1N647T mutation in azole resistance, we introduced the MRR1N647T mutation in an azole-susceptible C. auris isolate of clade IV that did not harbor any ERG11 mutation (IV.1, Fig. 1). The resulting IV.1 MRR1N647T strain exhibited a 4-fold increase of fluconazole and voriconazole MIC compared with its parental strain (Table 1). The decreased susceptibility of the IV.1 MRR1N647T strain to these azoles was also demonstrated by spotting assay (Fig. 2). However, the MICs of itraconazole and isavuconazole were not affected by this mutation (Table 1).

FIG 2.

Drug susceptibility testing by spotting assay of the mutant strains with introduction of the N647T mutation and their parental strains. (A) spotting assay with fluconazole; (B) spotting assay with voriconazole. Spotting assays were performed with serial dilutions of yeast cells spotted on YEPD agar plates containing fluconazole, voriconazole and in the absence of azoles. Concentrations of drugs were chosen according to the MICs of the tested strains. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C.

We concluded that the MRR1N647T mutation represents a GOF mutation resulting in reduced susceptibility to the short tailed azoles fluconazole and voriconazole in C. auris.

The MRR1N647T mutation reduces azole susceptibility via Mdr1 and not Cdr1.

As a next step, we investigated how the MRR1N647T mutation impacts azole susceptibility in C. auris. Because GOF mutations in MRR1 induce upregulation of MDR1 in C. albicans (11, 20), we postulated that a similar mechanism could exist in C. auris. Moreover, Iyer et al. observed that MDR1 was upregulated in two C. auris isolates of clade III harboring the MRR1N647T mutation (18). To support this hypothesis, we introduced the MRR1N647T mutation in a strain lacking MDR1. Deletion of MDR1 in the IV.1 strain (to generate the IV.1 mdr1Δ strain) had no impact on azole susceptibility (Table 1, Fig. 2). Addition of the MRR1N647T mutation to this IV.1 mdr1Δ strain (IV.1 mdr1Δ/MRR1N647T) could not reduce azole susceptibility, as it was the case in the IV.1 strain (Table 1, Fig. 2). These results strongly suggest that MDR1 is required to mediate a decrease of azole susceptibility via the MRR1N647T mutation.

We then investigated the link between Mrr1 and the Cdr1 drug transporter. Indeed, Iyer et al. have previously observed that CDR1 was highly expressed in two C. auris clade III isolates harboring the MRR1N647T mutation (18). Moreover, Mrr1 was shown to control both Mdr1 and Cdr1 expression in Candida lusitaniae, which is genetically close to C. auris (21). Deletion of CDR1 in the IV.1 strain (to generate the IV.1 cdr1Δ strain) resulted in a 4-fold MIC decrease of all four tested azoles (Table 1). Introduction of the MRR1N647T mutation in this IV.1 cdr1Δ strain (to generate the IV.1 cdr1Δ/MRR1N647T strain) resulted in an 8-fold and 4-fold increase of fluconazole and voriconazole MICs, respectively (Table 1). These results were confirmed by spotting assay (Fig. 2). We therefore concluded that decreased susceptibility to short tailed azoles induced by the MRR1N647T mutation is not dependent on Cdr1. Taken together, these results show that the MRR1N647T mutation results in decreased azole susceptibility via control of Mdr1 and not Cdr1.

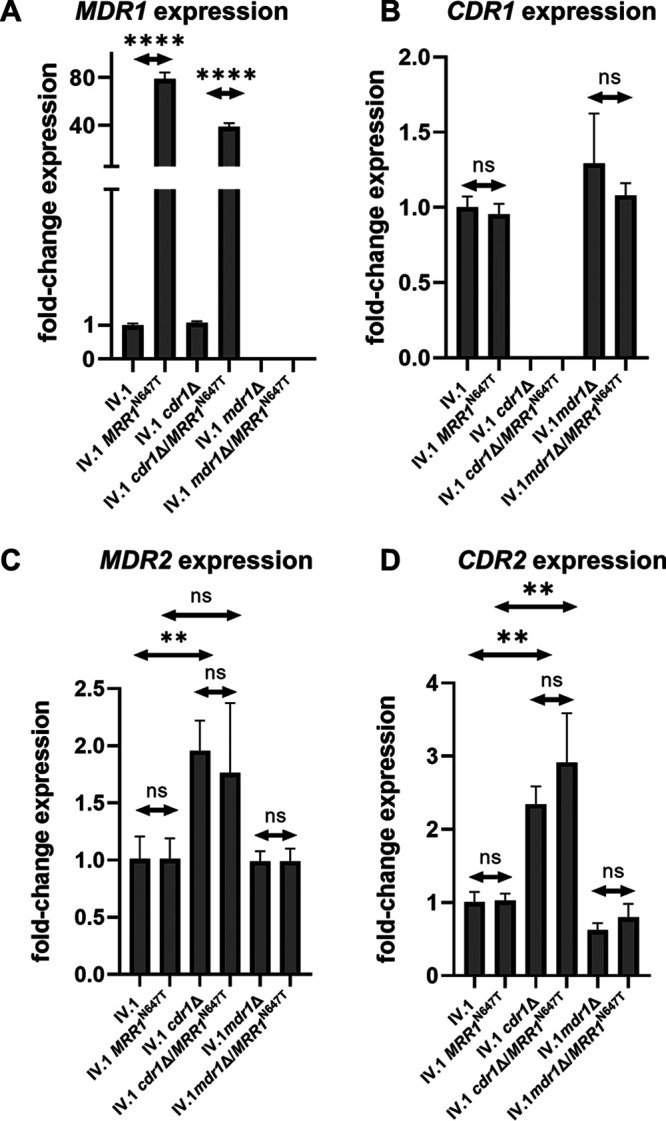

We next tested whether the MRR1N647T mutation could induce MDR1 upregulation. Real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analyses of MDR1 and CDR1 expression in the different IV.1 mutant strains (Fig. 3, panels A and B) showed that, when compared to a wild-type MRR1 allele, the MRR1N647T mutation resulted in significant upregulation of MDR1, but did not affect expression of CDR1. A significant upregulation of MDR1 was also observed in the absence of CDR1 in the IV.1 cdr1Δ/MRR1N647T strain.

FIG 3.

Relative expression of CDR1, MDR1, CDR2, and MDR2 in C. auris IV.1 and its respective MRR1, CDR1, MDR1 mutant strains. Results are expressed as fold change compared to the azole-susceptible isolate IV.1. Bars represent means with standard deviations of three biological replicates. P value was considered as statistically significant if <0.05. **, P ≤ 0.01; ****, P ≤ 0.0001; ns, not statistically significant.

We also analyzed the impact of the MRR1N647T mutation on MDR2 and CDR2 expression and did not observe any significant change (Fig. 3, panels C and D). CDR1 deletion resulted in some upregulation of MDR2 and CDR2, which could be interpreted as a compensatory effect.

DISCUSSION

Mechanisms of azole resistance in C. auris are multiple and complex, with some similarities compared to other Candida spp., but possibly also some distinct features. Several mutations in the azole target gene ERG11 have been reported in C. auris, which correspond to previously described hot spot regions of C. albicans (2, 12–14). As for C. albicans (22), the ABC transporter Cdr1 was shown to play an important role in C. auris azole resistance (16). While the transcription factor Tac1 was shown to be the main trigger of CDR1 expression in C. albicans (10), this link is less evident in C. auris (14, 17). Indeed, we have observed that TAC1a and TAC1b deletions in C. auris did not significantly impact CDR1 expression (14). In C. albicans, the MFS transporter Mdr1 is under the control of the transcription factor Mrr1, which represents an important pathway of azole resistance (11). However, the role of Mrr1 and Mdr1 in azole resistance of C. auris has not been fully investigated up to now. Rybak et al. have observed that MDR1 was upregulated in fluconazole-resistant C. auris clinical isolates compared with susceptible isolates (16). However, deletion of MDR1 in strains of clade I had no or very little effect on azole susceptibility (16). These observations were confirmed in the present study where MDR1 deletion in the IV.1 C. auris strain did not alter azole MICs. Moreover, we observed that MRR1 deletion had no or little impact on azole susceptibility. Only the isolate harboring the MRR1N647T mutation displayed a modest MIC decrease (2-fold) of short tailed azoles following MRR1 deletion. Previous studies have reported the presence of this N647T amino acid substitution in Mrr1 among the majority (98%) of C. auris clinical isolates of clade III (18, 19). All these isolates were fluconazole-resistant and harbored concomitant V125A and F126L amino acid substitutions in erg11 (18, 19). When measuring MDR1 and CDR1 expression in two of these clade III isolates, Iyer et al. observed that both genes were upregulated compared with a clade I reference strain (18). However, they did not find any known GOF mutation in Tac1b that could explain CDR1 upregulation in these isolates (18). As previously observed in C. lusitaniae, which is genetically close to C. auris, we have hypothesized that Mrr1 could control both Mdr1 and Cdr1 (21). Therefore, we intended to further delineate the link between Mrr1, the drug transporters Mdr1 and Cdr1, and azole resistance in C. auris. Our work demonstrated that the MRR1N647T mutation was responsible of MDR1 upregulation, but not CDR1, and that this mechanism was sufficient to significantly reduce susceptibility to fluconazole and voriconazole of C. auris, independently of the ERG11V125,F126L mutations. This impact on azole susceptibility was limited to the short tailed azoles, as it is expected following MDR1 upregulation, according to previous observations in C. albicans (22, 23). Albeit significant, the MIC increase resulting from this single MRR1N647T mutation were still below the tentative clinical breakpoints proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, available at: https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-antifungal.html) or other previous publications (≥32 μg/mL for fluconazole and ≥2 μg/mL for voriconazole) (2). We can conclude that, in these clade III isolates, the ERG11V125,F126L mutations play a predominant role in azole resistance, as illustrated by the modest decrease of azole susceptibility following MRR1 deletion in one of this isolate. However, the MRR1N647T mutation may contribute to further increase the level of azole resistance via MDR1 upregulation. The question remains open about the actual significance of this Mrr1-Mdr1 axis in azole resistance of C. auris. To our knowledge, there is no previous reports of the presence of the MRR1N647T mutation in clinical isolates other than clade III, or in the absence of concomitant ERG11V125,F126L mutations in clade III isolates. Further epidemiological and genotypic analyses are warranted in order to identify such clinical isolates that could harbor a similar phenotype as our laboratory generated IV.1 MRR1N647T strain with low level of azole resistance limited to short tailed azoles.

In conclusion, the present work highlighted another mechanism that may reduce azole susceptibility in C. auris consisting of the Mrr1-Mdr1 axis, which is triggered by upregulation of MDR1 via the amino acid substitution N647T in mrr1. This mechanism, in addition to ERG11 mutations, CDR1 upregulation and TAC1 GOF mutations, may contribute to the multifactorial and complex mechanisms of azole resistance in C. auris.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates, plasmids, and media.

The C. auris isolates used in this study are listed in Table 2. Plasmids pJK795 containing the NatR cassette and pYM70 containing the HygR cassette were used as source of nourseothricin and hygromycin resistances, respectively (24, 25). Isolates were grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YEPD) medium. Cultures were incubated for 16 to 20 h at 37°C on solid YEPD agar plates or in liquid YEPD under constant agitation (220 rpm).

TABLE 2.

Description of the strains generated in this study and their parental strains

| Name | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| III.8 | Clinical isolate | 33 |

| IV.1 | Clinical isolate | 34 |

| IV.2 | Clinical isolate | 34 |

| III.8 mrr1N647TΔ | III.8 mrr1N647TΔ::HygR | This study |

| IV.2 mrr1WTΔ | IV.2 mrr1WTΔ::HygR | This study |

| IV.1 cdr1Δ | IV.1 cdr1Δ::HygR | This study |

| IV.1 mdr1Δ | IV.1 mdr1Δ::HygR | This study |

| IV.1 MRR1N647T | IV.1 MRR1N647T::NatR | This study |

| IV.1 cdr1Δ/MRR1N647T | IV.1 cdr1Δ::HygR/MRR1N647T::NatR | This study |

| IV.1 mdr1Δ/MRR1N647T | IV.1 mdr1Δ::HygR/MRR1N647T::NatR | This study |

The antifungal drugs fluconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and isavuconazole (Alsachim, Shimadzu, France) were obtained as powder suspensions and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as stocks of 10 mg/mL for fluconazole and 1 mg/mL for other drugs.

PCR and sequencing.

The MRR1 and ERG11 genes of C. auris were identified using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Gene amplification was performed with Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) and DNA was purified with the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen Inc., Hilden, Germany). Sequencing was performed by the Sanger method (Microsynth, Balgach, Switzerland). All primers for PCR and sequencing are listed in the Supplementary Material S1. Sequencing data are deposited at GenBank under accession numbers OL742091 to OL742101 and OM287079 to OM287108.

Construction of C. auris mutants.

Three background strains were used for genetic manipulations: one isolate of clade III containing the MRR1N647T, ERG11V125A, and ERG11F126L mutations (III.8), and two isolates of clade IV with wild-type MRR1 and ERG11 alleles displaying low and high fluconazole MICs, respectively (IV.1 and IV.2, respectively). All primers and RNA guides used for these constructs are shown in Supplementary Material S1.

For the MRR1, CDR1, and MDR1 deletion strains, constructs containing upstream and downstream flanking regions of MRR1, CDR1, or MDR1 and the HygR cassette were obtained by fusion PCR of three PCR products with overlapping sequences, as illustrated in the Supplementary Material S2A (strains III.8 mrr1N647TΔ and IV.2 mrr1WTΔ), S3A (strain IV.1 cdr1Δ), and S4A (strain IV.1 mdr1Δ). For the introduction of the MRR1N647T mutation in the wild-type MRR1 allele, complementary primers containing the A1940C nucleotide substitution (corresponding to the N647T mutation) were used to generate a construct of the 3′-terminal region of MRR1 containing the mutation by fusion PCR. This construct was then fused by overlapping sequences with a PCR product containing the NatR (nourseothricin resistance) cassette and another one consisting of the downstream region of MRR1, as shown in Supplementary Material S5A.

Transformations in C. auris were performed by a CRISPR-Cas9 approach using the above genetic constructs. RNA-protein complexes (RNPs) reconstituted with purified Cas9 protein combined with scaffold- and gene-specific guide RNAs were used as previously described (26). Gene-specific RNA guides were designed to contain 20-bp homologous sequences of the upstream and downstream regions of the Cas9 target (Supplementary Material S2B, S3B, S4B, and S5B). The mix of the guide RNAs, the Cas9 endonuclease 3NLS (Integrated DNA Technologies Inc., Coralville, IA), and tracrRNA (an universal transactivating CRISPR RNA) were prepared according to a previously described protocol (27). Transformation of C. auris was performed by electroporation with about 1 μg of the constructs as previously described (27). Transformants were selected at 35°C on YEPD agar containing 600 μg/mL of hygromycin (Corning, Somerville, MA) or 200 μg/mL of nourseothricin (Werner BioAgents, Jena, Germany) for constructs containing the HygR and the NatR selection cassettes, respectively. Correct integration of the constructs in the transformants was verified by PCR screening (Supplementary Material S2C, S3C, S4C, and S5C) and the presence or absence of mutations was verified by sequencing.

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

MICs of fluconazole, voriconazole, isavuconazole, and itraconazole were determined for the C. auris isolates according to the procedure of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, M27, 4th edition) (28). Antifungal susceptibility was also assessed by a spotting assay using 10-fold dilutions of yeast suspension, from 107 cells/mL to 104 cells/mL, spotted (5 μL) onto YEPD plates with or without drugs (fluconazole and voriconazole). Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C.

Real-time RT-PCR.

Each C. auris isolate was grown overnight in 5 mL of liquid YEPD under constant agitation at 37°C. Overnight cultures were diluted to a density of 0.75 × 107 cells/mL in 10 mL of fresh YEPD and were grown at 37°C under constant agitation for 2 to 3 h to reach a density of 1.5 × 107 cells/mL. Total RNA was extracted with the Quick-RNA fungal/bacterial miniprep kit (Zymo Research, Freiburg im Brisgau Germany), and total RNA extracts were treated with DNase using the DNA-free kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). The concentration of purified RNA was measured with a NanoDrop 1000 instrument (Witec AG, Sursee, Switzerland). RNA was stored at −80°C until use. Each isolate was prepared in biological triplicates.

One microgram of RNA of each isolate was converted into cDNA using the Transcriptor high-fidelity cDNA synthesis kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). RT-PCR was performed in 96-well plates using the PowerUp SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA) with primers of the targeted genes (Supplementary Material S1) and supplemented with nuclease-free water up to 20 μL for each reaction. The primers used for ACT1, CDR1, CDR2, MDR1, and MDR2 mRNA amplification were the same as previously described (16). Each experiment was performed in biological triplicates and technical duplicates. The QuantStudio software program (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) including a melt curve stage was used with activation at 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. Gene expression was calculated with the threshold cycle (2−ΔΔCT) method (29). Results were analyzed by the t test method (GraphPad).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marie-Elisabeth Bougnoux from Institut Pasteur (Paris, France), Maurizio Sanguinetti from Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Roma, Italy), Judith Berman and Ronen Ben-Ami from Tel Aviv University (Tel Aviv, Israel), Guillermo Garcia-Effron from Universidad Nacional del Litoral (Santa Fe de la Vera Cruz, Argentina), Nicolas Papon from Angers University (Angers, France), and Arnaud Riat from Geneva University Hospital (Geneva, Switzerland), for providing us all the Candida auris strains from this study.

This work was supported by a research grant from the Santos-Suarez Foundation.

F. Lamoth received research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Santos-Suarez Foundation, Novartis, MSD, and Pfizer outside of the submitted work, and speaker honoraria from Gilead.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lamoth F, Kontoyiannis DP. 2018. The Candida auris alert: facts and perspectives. J Infect Dis 217:516–520. 10.1093/infdis/jix597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lockhart SR, Etienne KA, Vallabhaneni S, Farooqi J, Chowdhary A, Govender NP, Colombo AL, Calvo B, Cuomo CA, Desjardins CA, Berkow EL, Castanheira M, Magobo RE, Jabeen K, Asghar RJ, Meis JF, Jackson B, Chiller T, Litvintseva AP. 2017. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses. Clin Infect Dis 64:134–140. 10.1093/cid/ciw691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Satoh K, Makimura K, Hasumi Y, Nishiyama Y, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. 2009. Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol Immunol 53:41–44. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow NA, de Groot T, Badali H, Abastabar M, Chiller TM, Meis JF. 2019. Potential fifth clade of Candida auris, Iran, 2018. Emerg Infect Dis 25:1780–1781. 10.3201/eid2509.190686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schelenz S, Hagen F, Rhodes JL, Abdolrasouli A, Chowdhary A, Hall A, Ryan L, Shackleton J, Trimlett R, Meis JF, Armstrong-James D, Fisher MC. 2016. First hospital outbreak of the globally emerging Candida auris in a European hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 5:35. 10.1186/s13756-016-0132-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyre DW, Sheppard AE, Madder H, Moir I, Moroney R, Quan TP, Griffiths D, George S, Butcher L, Morgan M, Newnham R, Sunderland M, Clarke T, Foster D, Hoffman P, Borman AM, Johnson EM, Moore G, Brown CS, Walker AS, Peto TEA, Crook DW, Jeffery KJM. 2018. A Candida auris outbreak and its control in an intensive care setting. N Engl J Med 379:1322–1331. 10.1056/NEJMoa1714373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhary A, Anil Kumar V, Sharma C, Prakash A, Agarwal K, Babu R, Dinesh KR, Karim S, Singh SK, Hagen F, Meis JF. 2014. Multidrug-resistant endemic clonal strain of Candida auris in India. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 33:919–926. 10.1007/s10096-013-2027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White TC. 1997. The presence of an R467K amino acid substitution and loss of allelic variation correlate with an azole-resistant lanosterol 14alpha demethylase in Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:1488–1494. 10.1128/AAC.41.7.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morio F, Loge C, Besse B, Hennequin C, Le Pape P. 2010. Screening for amino acid substitutions in the Candida albicans Erg11 protein of azole-susceptible and azole-resistant clinical isolates: new substitutions and a review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 66:373–384. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coste AT, Karababa M, Ischer F, Bille J, Sanglard D. 2004. TAC1, transcriptional activator of CDR genes, is a new transcription factor involved in the regulation of Candida albicans ABC transporters CDR1 and CDR2. Eukaryot Cell 3:1639–1652. 10.1128/EC.3.6.1639-1652.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morschhauser J, Barker KS, Liu TT, Bla BWJ, Homayouni R, Rogers PD. 2007. The transcription factor Mrr1p controls expression of the MDR1 efflux pump and mediates multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 3:e164. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chowdhary A, Prakash A, Sharma C, Kordalewska M, Kumar A, Sarma S, Tarai B, Singh A, Upadhyaya G, Upadhyay S, Yadav P, Singh PK, Khillan V, Sachdeva N, Perlin DS, Meis JF. 2018. A multicentre study of antifungal susceptibility patterns among 350 Candida auris isolates (2009–17) in India: role of the ERG11 and FKS1 genes in azole and echinocandin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 73:891–899. 10.1093/jac/dkx480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Healey KR, Kordalewska M, Jimenez Ortigosa C, Singh A, Berrio I, Chowdhary A, Perlin DS. 2018. Limited ERG11 mutations identified in isolates of Candida auris directly contribute to reduced azole susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 62. 10.1128/AAC.01427-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Coste AT, Liechti M, Bachmann D, Sanglard D, Lamoth F. 2021. Novel ERG11 and TAC1b mutations associated with azole resistance in Candida auris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65. 10.1128/AAC.02663-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rybak JM, Munoz JF, Barker KS, Parker JE, Esquivel BD, Berkow EL, Lockhart SR, Gade L, Palmer GE, White TC, Kelly SL, Cuomo CA, Rogers PD. 2020. Mutations in TAC1B: a novel genetic determinant of clinical fluconazole resistance in Candida auris. mBio 11. 10.1128/mBio.00365-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rybak JM, Doorley LA, Nishimoto AT, Barker KS, Palmer GE, Rogers PD. 2019. Abrogation of triazole resistance upon deletion of CDR1 in a clinical isolate of Candida auris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63. 10.1128/AAC.00057-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayr EM, Ramirez-Zavala B, Kruger I, Morschhauser J. 2020. A zinc cluster transcription factor contributes to the intrinsic fluconazole resistance of Candida auris. mSphere 5. 10.1128/mSphere.00279-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyer KR, Camara K, Daniel-Ivad M, Trilles R, Pimentel-Elardo SM, Fossen JL, Marchillo K, Liu Z, Singh S, Munoz JF, Kim SH, Porco JA, Jr, Cuomo CA, Williams NS, Ibrahim AS, Edwards JE, Jr, Andes DR, Nodwell JR, Brown LE, Whitesell L, Robbins N, Cowen LE. 2020. An oxindole efflux inhibitor potentiates azoles and impairs virulence in the fungal pathogen Candida auris. Nat Commun 11:6429. 10.1038/s41467-020-20183-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maphanga TG, Naicker SD, Kwenda S, Munoz JF, van Schalkwyk E, Wadula J, Nana T, Ismail A, Coetzee J, Govind C, Mtshali PS, Mpembe RS, Govender NP, For G-S, for GERMS-SA. 2021. In vitro antifungal resistance of Candida auris Isolates from bloodstream infections, South Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:e0051721. 10.1128/AAC.00517-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunkel N, Blass J, Rogers PD, Morschhauser J. 2008. Mutations in the multi-drug resistance regulator MRR1, followed by loss of heterozygosity, are the main cause of MDR1 overexpression in fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains. Mol Microbiol 69:827–840. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borgeat V, Brandalise D, Grenouillet F, Sanglard D. 2021. Participation of the ABC transporter CDR1 in azole resistance of Candida lusitaniae. JoF 7:760. 10.3390/jof7090760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanglard D, Ischer F, Monod M, Bille J. 1996. Susceptibilities of Candida albicans multidrug transporter mutants to various antifungal agents and other metabolic inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 40:2300–2305. 10.1128/AAC.40.10.2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanglard D, Coste AT. 2016. Activity of isavuconazole and other azoles against Candida clinical isolates and yeast model systems with known azole resistance mechanisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:229–238. 10.1128/AAC.02157-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen J, Guo W, Kohler JR. 2005. CaNAT1, a heterologous dominant selectable marker for transformation of Candida albicans and other pathogenic Candida species. Infect Immun 73:1239–1242. 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1239-1242.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basso LR, Jr, Bartiss A, Mao Y, Gast CE, Coelho PS, Snyder M, Wong B. 2010. Transformation of Candida albicans with a synthetic hygromycin B resistance gene. Yeast 27:1039–1048. 10.1002/yea.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grahl N, Demers EG, Crocker AW, Hogan DA. 2017. Use of RNA-protein complexes for genome editing in non-albicans Candida species. mSphere 2. 10.1128/mSphere.00218-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kannan A, Asner SA, Trachsel E, Kelly S, Parker J, Sanglard D. 2019. Comparative genomics for the elucidation of multidrug resistance in Candida lusitaniae. mBio 10. 10.1128/mBio.02512-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). 2017. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts, 4th ed. Document M27. Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munoz JF, Gade L, Chow NA, Loparev VN, Juieng P, Berkow EL, Farrer RA, Litvintseva AP, Cuomo CA. 2018. Genomic insights into multidrug-resistance, mating and virulence in Candida auris and related emerging species. Nat Commun 9:5346. 10.1038/s41467-018-07779-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chow NA, Munoz JF, Gade L, Berkow EL, Li X, Welsh RM, Forsberg K, Lockhart SR, Adam R, Alanio A, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Althawadi S, Arauz AB, Ben-Ami R, Bharat A, Calvo B, Desnos-Ollivier M, Escandon P, Gardam D, Gunturu R, Heath CH, Kurzai O, Martin R, Litvintseva AP, Cuomo CA. 2020. Tracing the evolutionary history and global expansion of Candida auris using population genomic analyses. mBio 11. 10.1128/mBio.03364-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Coste AT, Bachmann D, Sanglard D, Lamoth F. 2021. Assessment of the in vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of NSC319726 against Candida auris. Microbiol Spectr 9:e0139521. 10.1128/Spectrum.01395-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Ami R, Berman J, Novikov A, Bash E, Shachor-Meyouhas Y, Zakin S, Maor Y, Tarabia J, Schechner V, Adler A, Finn T. 2017. Multidrug-resistant Candida haemulonii and C. auris, Tel Aviv, Israel. Emerg Infect Dis 23. 10.3201/eid2302.161486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theill L, Dudiuk C, Morales-Lopez S, Berrio I, Rodriguez JY, Marin A, Gamarra S, Garcia-Effron G. 2018. Single-tube classical PCR for Candida auris and Candida haemulonii identification. Rev Iberoam Micol 35:110–112. 10.1016/j.riam.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 and Fig. S2 to S5. Download aac.00067-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.4 MB (1.4MB, pdf)