Abstract

1. Many infectious pathogens spend a significant portion of their life cycles in the environment or in animal hosts, where ecological interactions with natural enemies may influence pathogen transmission to people. Yet, our understanding of natural enemy opportunities for human disease control is lacking, despite widespread uptake and success of natural enemy solutions for pest and parasite management in agriculture.

2. Here we explore three reasons why conserving, restoring, or augmenting specific natural enemies in the environment could offer a promising complement to conventional clinical strategies to fight environmentally mediated pathogens and parasites. (1) Natural enemies of human infections abound in nature, largely understudied and undiscovered. (2) Natural enemy solutions could provide ecological options for infectious disease control where conventional interventions are lacking. And, (3) Many natural enemy solutions could provide important co-benefits for conservation and human well-being.

3. We illustrate these three arguments with a broad set of examples whereby natural enemies of human infections have been used or proposed to curb human disease burden, with some clear successes. However, the evidence base for most proposed solutions is sparse, and many opportunities likely remain undiscovered, highlighting opportunities for future research.

Keywords: biological control, natural enemies, infectious disease, sustainability, sustainable development, disease ecology, disease control

Introduction

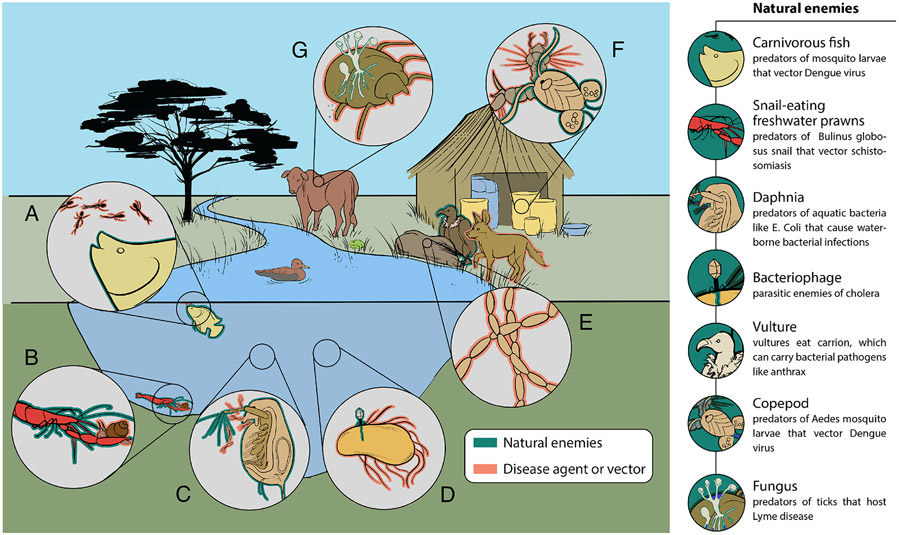

The war against citrus pests in ancient Chinese orchards was not won by eliminating insect life, but by cultivating it. A strategy still in use today, farmers introduced yellow citrus ants, voracious predators of beetles, flies, and hymenopteran crop pests, to orchards to protect fruit from pest damage (Huang & Yang, 1987). This is the earliest documented example of biological control, or pest control using natural enemies. Active management of these natural “enemies of our enemies” is a key component of integrated pest management in agriculture, around which ecosystem services evaluations and commercial industries worth billions of dollars have emerged (Losey & Vaughan, 2006; Naranjo et al., 2015; R. Naylor & Ehrlich, 1997; Power, 2010). Like agricultural pests, many parasites and pathogens that cause disease in humans spend a considerable amount of their life cycle in the environment or in animal hosts where natural enemy interactions can influence their abundance and, subsequently, transmission to humans (Fig. 1). Here, we argue that broadening our understanding of interactions between environmentally mediated infectious organisms and their natural enemies could help to identify novel ecological interventions for human health. Effective ecological interventions, or actions that leverage ecological mechanisms to protect human health (Sokolow et al., 2019), may also offer co-benefits in other sectors like biodiversity conservation and sustainable development.

Figure 1.

Natural enemies (outlined in green) of human infections in the environment (outlined in orange). (A) Larvivorous fish predators of mosquito vectors. (B) Macrobrachium spp. crustacean predators of schistosomiasis intermediate host snails. (C) Daphnia spp. crustacean predators of aquatic bacteria, including Escheria coli and Campylobacter jejuni. (D) Phage predation on V. cholerae. (E) Vulture consumers of disease-carrying carcasses, and competitors of wild dogs that can carry rabies. (F) Copepod predators of larval Aedes mosquito vectors of dengue virus. (G) Fungal pathogen, Beauveria bassiana, of tick disease vectors.

Human health benefits from natural enemies all the time. On skin, mucosa, and in the gut, healthy communities of beneficial microbes can suppress the proliferation of harmful bacteria through resource competition and the production of antimicrobial compounds (Dethlefsen et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2013). Applying an ecosystem perspective to the microbial infections we host has led to clinical trials and commercialization of some natural enemy-based therapeutics, including probiotics for use against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Clostridium difficile, and upper respiratory infections (Bernaola Aponte et al., 2013; Goldenberg et al., 2017; Hao et al., 2015; Kassam et al., 2013; Koretz & Rotblatt, 2004). More recently, bacteriophages (naturally occurring viruses that infect and kill bacteria and archaea) have received increased attention as a promising alternative to antibiotics for multidrug-resistant infections (Dedrick et al., 2019; Nobrega et al., 2015).

In the environment, where the focus of this Perspective lies, natural regulation of infectious organisms and disease hosts is an ongoing process that may benefit human health by limiting populations of disease-causing organisms. Free-living stages of parasites and pathogens, and their non-human hosts are embedded in ecological communities, where they are used as resources by consumers and compete with other organisms for their own resources. Some of the natural enemies of important disease vectors, including mosquitoes, ticks, flies, and snails, have been identified, revealing a wide range of naturally occurring enemies (Erlanger et al., 2008; Jenkins, 1964; Kamareddine, 2012; Keiser et al., 2005; Lacey & Lacey, 1990; Lardans & Dissous, 1998; Pointier et al., 2011; Samish et al., 2004). However, very little is known about the true breadth of natural enemy interactions that could potentially be used for human infection control through natural enemy protection (i.e., species or habitat conservation) or implementation (i.e., population augmentation or introduction). Of those interactions that have been identified as potential ecological interventions, quantitative evidence on their epidemiological impact and cost-effectiveness is severely lacking (Lugassy et al., 2021; McKinnon et al., 2016). Subsequently, there is limited knowledge and little operational use of specific natural enemy tools for human infection control in the environment, leading to an under-appreciation of the ecosystem services that they may provide to people. This is in contrast to a rich history of natural enemy research and implementation for pest and pathogen control in agriculture, including through classical (inoculative) and conservation biological control strategies (Barratt et al., 2018).

The modern era of clinical disease intervention, which dominates public health strategies to control environmentally mediated diseases (Remais & Eisenberg, 2012), has vastly improved the health and well-being of billions of people worldwide (Bloom & Cadarette, 2019). At the same time, billions of people remain at-risk for long-standing, re-emerging, and emerging infectious diseases, many with important environmental reservoirs that clinical interventions alone may not adequately address (Bloom & Cadarette, 2019; Garchitorena et al., 2017). Therefore, we argue three key reasons why the human health impacts of natural enemy interactions with disease-causing organisms in the environment deserve more attention. (1) Natural enemies of disease-causing organisms abound in nature, largely undiscovered; (2) Natural enemy solutions could provide ecological options for infectious disease control where conventional (chemical-based) approaches are limited or insufficient; and, (3) Natural enemy solutions could offer a wide range of co-benefits in other sectors like conservation and food security. First, we explore these three reasons with relevant examples. Next, we discuss challenges that have hindered research on and implementation of natural enemy solutions, and how we might overcome some of those challenges in the near future.

Three reasons why natural enemy solutions for sustainable control of human infections deserve more attention

Reason 1: Natural enemies of disease-causing organisms abound in nature

Growing interest in understanding the ecological contexts of infectious disease transmission may help incentivize research to better understand the diversity and health impacts of natural enemies. Parasites and pathogens are increasingly well recognized as components of complex ecosystems (Horwitz & Wilcox, 2005). Several prominent research movements embrace this perspective as critical to better prevent infections and protect human health. These include EcoHealth, One Health, and Planetary Health (Charron, 2012; Evans & Leighton, 2014; Whitmee et al., 2015). Each movement has its own distinct flavor (Lerner & Berg, 2017), but all recognize the importance of understanding how ecological interactions influence human health outcomes (Lerner & Berg, 2017). However, empirical evidence that links knowledge to actionable solutions to leverage ecological interactions for infection control is sparse (Lugassy et al., 2021; McKinnon et al., 2016). This is especially true for natural enemies: in a recent systematic evidence map linking ecosystem functions to 14 vector-borne and zoonotic diseases, the epidemiological impact of predation and competition was identified as a major knowledge gap (Lugassy et al., 2021).

Despite the evidence gaps, opportunities to identify novel natural enemy solutions for health abound, because natural enemies abound in nature. We focus on three distinct types of natural enemies that nearly all living organisms contend with: predators, parasites, and ecological competitors. In agriculture, natural enemy solutions typically exploit consumer-resource (or enemy-victim) interactions (i.e., interactions with predators, parasitoids, and pathogenic micro-organisms) (van Lenteren et al., 2018). We include ecological competitors in our broad definition of natural enemies because the negative outcomes of competition on population sizes of infectious organisms can, in certain contexts, have substantial impacts on infectious disease transmission, and could be leveraged as natural enemy solutions for human health.

Predators

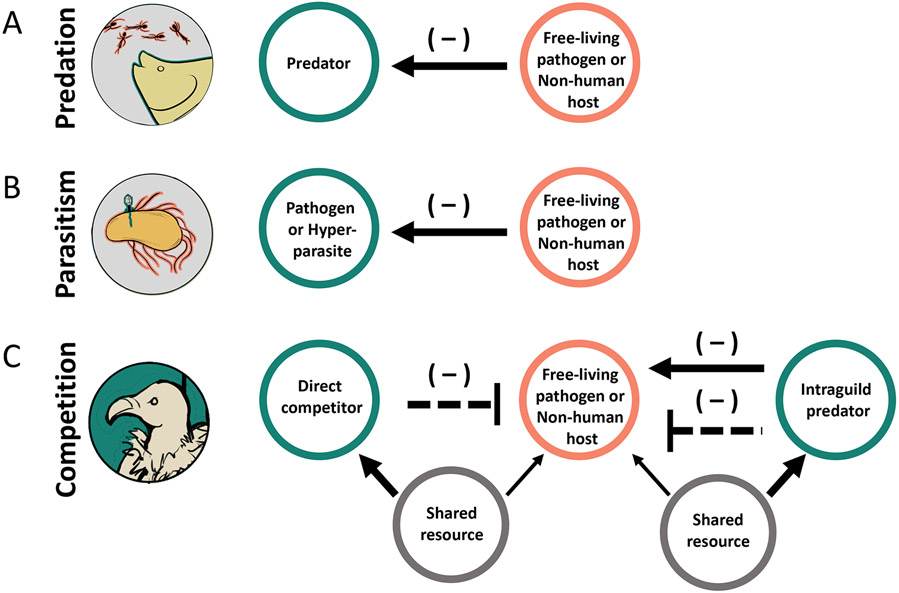

Virtually all organisms serve as food for other organisms. Predation is a form of consumer-resource relationship in which a predator attacks, kills, and ingests prey (Lafferty et al., 2015). Predators can influence the transmission of environmentally mediated disease by consuming free-living infectious organisms, or non-human hosts (Fig. 2a). Predators can be grouped according to their diet breadth. Generalists consume a wide variety of prey, while specialists have a narrow prey breadth. In the 20th century, agricultural biocontrol activities tended to focus on specialist predators and parasitoids, as diet specificity was considered a key attribute for natural enemies that were to be introduced to exotic habitats (Symondson et al., 2002). However, high prey specificity also means that specialists can become scarce when prey is limited (Symondson et al., 2002), thus leading to periods of increased human disease risk when specialist predator density declines and prey density increases (Ostfeld & Holt, 2004). The role of generalist predators in providing a chronic, background level of pest suppression in agriculture has been appreciated more recently, evidenced by a growing movement towards conservation biological control. Under this scheme, efforts are made to enhance the abundance of native generalist predators (individual species or guilds of multiple species) for sustained pest suppression (Symondson et al., 2002).

Figure 2.

General categories of natural enemy interactions with disease-causing organisms: (A) predation; (B) parasitism; and, (C) competition, including intraguild predation, a special case of competition when an organism is both a competitor and a predator of another organism.

The beneficial role that predators play in human infection control has often been appreciated only retrospectively, after their depletion was found to correlate with disease outbreaks (Ostfeld & Holt, 2004). For example, overfishing in Lake Malawi resulted in population losses of cichlid fish, some of which predated on freshwater snails that serve as the intermediate host for human schistosomiasis (snail fever). The schistosomiasis outbreak that followed the depletion of fish stocks suggested that the fish had been performing an important ecosystem service for human health (Stauffer et al., 2006; Stauffer & Madsen, 2012). Field studies to better quantify the ecosystem services that predators provide for human health are badly needed, because efforts to conserve, restore, or augment natural predator populations could potentially yield benefits for both health and the environment. Currently, evidence that natural predators can be proactively harnessed to improve disease control is poor.

Parasites

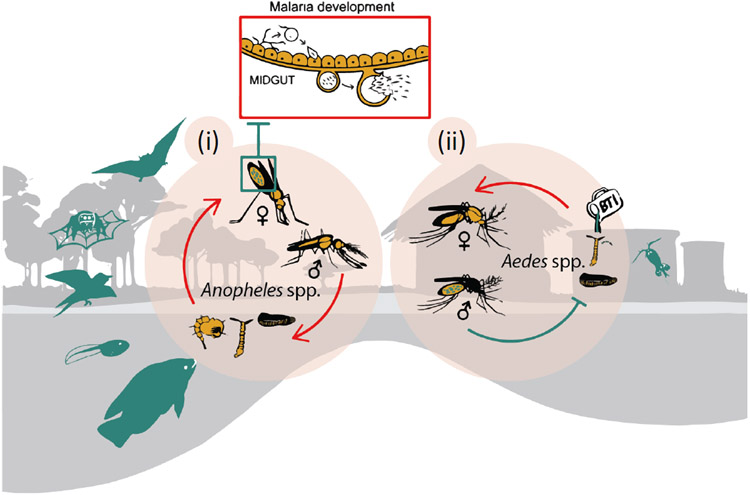

Parasitism is another type of consumer-resource relationship in which one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside a host, benefitting at the host’s expense (Fig. 2b) (Lafferty & Kuris, 2002). Parasites and pathogens (including hyperparasites, or parasites of parasites) are commonly used for pest control in agriculture and have to a lesser extent been investigated as tools for human disease control. Leveraging natural enemy research for biopesticide development in agriculture, some insect pathogens or their chemical derivatives were commercialized for use against human disease vectors. For example, Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis (Bti) and Lysinibacillus sphaericus (formerly Bacillus sphaericus) are widely available biopesticides effective against several major disease vectors, including mosquitoes and blackflies (vectors of onchocerciasis) (Regis et al., 2001). More recently, Metarhizium brunneum and Beauveria bassiana – entomopathogenic fungi that induce high mortality in adult Anopheles spp. mosquitoes (malaria vectors), Ixodes spp. black-legged ticks (Lyme disease vectors), and larval Phlebotomus sand flies (leishmaniasis vectors) – have been developed for commercial use (Fig. 1) (Amora et al., 2009; Farenhorst et al., 2011; Fernandes & Elias Pinheiro Bittencourt, 2008; George et al., 2013; Hornbostel et al., 2005; Kaaya, 2000; Scholte et al., 2006).

Bacteriophages, or highly specific viruses of bacteria, are some of the most abundant and diverse microbes on earth. In food sciences, bacteriophages are currently being investigated as a type of preservative that kills food-borne pathogens like Salmonella, Campylobacter, Listeria, Staphylococcus, and Vibrio spp. (Bai et al., 2016). Bacteriophages have also been considered as a potential control agent against Vibrio cholerae, both as a disease therapy and as an environmental intervention (Yen et al., 2017) (Fig. 1). However, limited evidence for both of these cholera control strategies is mixed (Faruque et al., 2005; Nelson et al., 2009; Silva-Valenzuela & Camilli, 2019). Even so, bacteriophages continue to generate attention as an important potential alternative to antibiotics, as concern over antibiotic-resistant pathogens in the environment and in people grows.

Ecological competitors

Competition for resources can limit populations of free-living parasites and pathogens, or their non-human hosts (Fig. 2c). For example, there is some (marginally significant) evidence that biologically diverse rodent communities in the western United States support a lower Sin Nombre hantavirus abundance, potentially because resource competition limits the relative abundance of an important reservoir host, Peromyscus maniculatus (Clay et al., 2009). In Caribbean countries such as Antigua, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Montserrat, Puerto Rico, and St. Lucia, snail-borne schistosomiasis disease has been dramatically reduced in low-transmission settings, thanks in part to the accidental or intentional introduction of competitor snail species. These snail competitors included Pomacea glauca, Marisa cornuarietis, Melanoides tuberculata, or Tarebia granifera, presence of which reduced, displaced, or prevented colonization of specific schistosome-transmitting snails species (Pointier & Jourdane, 2000).

In certain contexts, competition may drive a “dilution effect”. The dilution effect hypothesis posits that disease transmission rates tend to be lower in more diverse ecological communities. In theory, this occurs because (i) biodiversity decreases the relative abundance of suitable hosts, or (ii) biodiversity decreases encounter rates between disease-causing organisms and suitable hosts, and increase that between disease-causing organisms and unsuitable hosts (Rohr et al., 2020; Wood et al., 2014). For example, some experimental evidence suggests that human risk for schistosomiasis is inversely related to local diversity of trematodes (the class of parasites to which schistosomes belong). Laboratory and field studies suggest that, where trematode diversity is high, competition between larval stages of human and non-human trematodes to infect snail hosts reduces the relative abundance of schistosome infections in snails (Johnson et al., 2009; Laidemitt et al., 2019; Sulieman & Pengsakul, 2013; Tang et al., 2009). Even though the indirect effect of specific competitors on human disease risk is difficult to quantify, diverse guilds of competitors might be helping to mitigate human disease risk, outside of our notice, all the time.

Reason 2: Natural enemy solutions could provide ecological options for infectious disease control where conventional interventions are limited

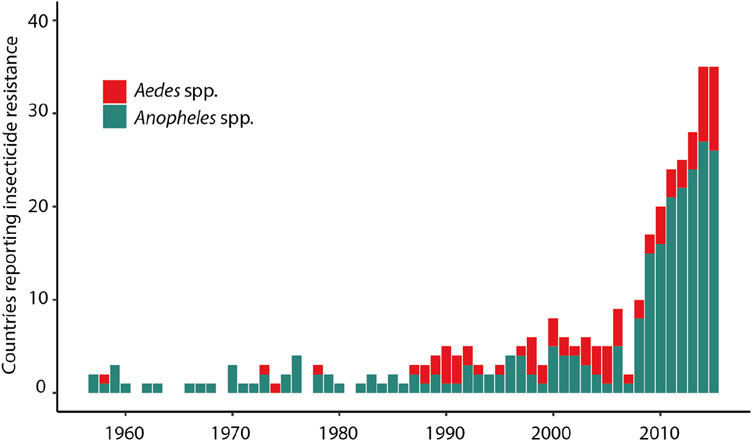

Major advances in medicine and global health have vastly reduced infectious disease mortality (Dye, 2014). Even so, environmentally mediated diseases including malaria, diarrhea, and most of the neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), remain some of the most significant causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide (Bloom & Cadarette, 2019; Dye, 2014; WHO, 2016). NTDs alone infect over a billion people, predominantly the world’s poorest and most vulnerable populations. Meanwhile, other infectious diseases have emerged or re-emerged in recent decades, including West Nile virus, Zika, plague, avian influenza, and Lyme disease, among others (Kilpatrick & Randolph, 2012; Morens et al., 2004). Conventional intervention strategies, like vaccines, drug treatment, and insecticide-based vector control, are crucial tools in the fight against environmentally mediated diseases. However, there are currently no licensed vaccines to prevent malaria or any neglected tropical disease, aside from Dengue (Hotez, 2019). Mass drug administration (the primary strategy to reduce global NTD morbidity and mortality) can be highly effective, but does not prevent infections. Consequently, a survey conducted between 2007 and 2011 of more than 400 NTD experts concluded that elimination of several major NTDs, including soil-transmitted helminths and schistosomiasis, will not be feasible with mass drug administration alone (Keenan et al., 2013). Finally, insecticide resistance is a growing problem challenging long-term control of many important insect vectors of disease (Nauen, 2007) (Fig. 3). To enhance sustainable control of environmentally mediated diseases, complementary strategies that target the environmental reservoirs of diseases are badly needed (Evan Secor, 2014; Garchitorena et al., 2017; Remais & Eisenberg, 2012).

Figure 3.

The number of countries reporting mosquito vector resistance to one or more major classes of insecticide used globally in the fight against mosquito-borne diseases. Data was obtained from the Vectorbase database (Giraldo-Calderón et al., 2015); resistance data was filtered to include resistance reported as percent mortality, and resistance was conservatively defined as mosquito mortality less than 95%.

Promisingly, modeling studies on Buruli ulcer and schistosomiasis control strategies showed that integrated MDA and environmental intervention, including through use of natural enemies, may control disease faster and more cost-effectively than either approach alone (Garchitorena et al., 2017; Hoover et al., 2019; Lo et al., 2018; Sokolow et al., 2015). For example, the Sokolow et al. study (Sokolow et al., 2015) modeled empirical evidence to show that MDA plus restoration of snail predators (freshwater Macrobrachium prawns) in water bodies where humans were acquiring schistosome infections reduced disease burden in people more than MDA alone. The prawn predators are also a valued food product, and could provide nutrition and income in addition to snail control.

For many important vector-borne diseases, chemical-based vector control is the main strategy to prevent disease transmission. However, extensive use of insecticides for vector control has led to a worrying rise in insecticide-resistance (Fig. 3). Currently, there is evidence for vector (e.g., mosquito, blackfly, sandfly, tick) resistance against all major classes of insecticides (Nauen, 2007), resulting in an increasingly urgent need for alternative methods to control vectors of public health importance. Notably, when faced with widespread insecticide-resistance in blackfly populations, the Onchocerciasis Control Programme (OCP) of West Africa turned to commercially available Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. israelensis (Bti) to enhance control of Simulium spp. blackfly larvae. The program ultimately reduced onchocerciasis in 16 participating countries through a combination of vector control and drug distribution (Regis et al., 2001). However, potential non-target impacts of Bti, while generally understood to be minimal, are still being unraveled (Poulin et al., 2010).

Given the immense impact of mosquito-borne diseases on people, communities, and economies, finding alternative options to insecticide-based control, as insecticide-resistance mounts, has been elevated in priority. Two very different natural enemy strategies have received the most attention as insecticide-alternatives: biopesticides, and use of larvivorous mosquito predators (Fig. 4). Like chemical insecticides, biopesticides can be mass-produced and spread across large areas. As discussed already, Bti is one of the most widely used mosquito larvicides, and entomopathogenic fungi show promise against adult mosquitoes. It is possible that mosquitoes will develop resistance to biopesticides (Lacey, 2007), but so far, no evidence suggests widespread Bti resistance in field populations of mosquitoes, even after decades of application (Tetreau et al., 2013). And, because entomopathogenic fungi produce several toxins that kill adult mosquitoes, it is likely that mosquito populations develop resistance over a much longer timescale than they do for chemical insecticides (Benelli et al., 2016).

Figure 4.

Natural predators (green) of adult and larval mosquitoes are widespread, and include various species of bats, arthropods, birds, amphibians, fish, and crustaceans. Naturally occurring strains of Wolbachia bacteria may (i) inhibit development of arboviruses in Aedes spp. and, potentially, malaria in Anopheles spp., or (ii) lead to sterility when artificially infected male mosquitoes mate with wild, uninfected females.

More recently, Wolbachia pipientis, a rickettsia-like bacterium that naturally infects a wide range of insects, has been leveraged as a new biopesticide against mosquitoes (Fig. 4). Theoretically, Wolbachia might reduce disease transmission via two mechanisms: (i) population suppression via release of Wolbachia-infected males that produce sterile offspring when mated with wild-type females, thus reducing the vector population over many generations (akin to sterile insect techniques (Benedict & Robinson, 2003)), and (ii) population replacement via release of male and female mosquitoes infected with a vertically-transmissible Wolbachia strain that confers resistance to specific pathogens (Fig. 4) (Flores & O’Neill, 2018; Hughes et al., 2011). However, Wolbachia infection in some Anopheles mosquitoes may increase vector competence, which would severely challenge the dissemination of this solution into natural environments where mosquito-borne disease transmission occurs (Weiss & Aksoy, 2011).

As for predators, the World Health Organization (WHO) has promoted larvivorous fish as an insecticide alternative for malaria control since the 1970’s (Fig. 1) (Walshe et al., 2017). In light of negative environmental consequences following fish introductions, discussed in more detail in the next section, the WHO has scaled back their pitch (Walshe et al., 2017). And, evidence for the scheme is lacking. A recent review assessing larvivorous fish for mosquito vector control found no studies that reported human malaria transmission as an outcome, thus limiting impact and cost-effectiveness studies (Walshe et al., 2017). For Aedes spp. mosquitoes (vectors of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya, and other arboviruses), copepods are included alongside larvivorous fish in WHO documentation for dengue control strategies (WHO, 2011) and have proven efficient larval predators in specific environments. For example, a series of studies carried out over several years in Vietnam showed that Mesocyclops copepods introduced to mosquito breeding containers can reduce larval and adult mosquito density and dengue seroprevalence in humans (Fig. 4) (Lazaro et al., 2015). Such a large-scale intervention has not been replicated in other locations, and success in the Vietnamese communities may be attributable to a key combination of several factors including environmental conditions conducive to copepod survival, significant community involvement, and larval habitat clean-up campaigns. Copepod studies in other regions have had mixed outcomes, and while considered relatively cheap and low-maintenance (Soumare & Cilek, 2011), human transmission and cost-effectiveness studies have not yet been undertaken.

Reason 3: Natural enemy solutions could offer co-benefits for conservation, food security, and human well-being

Recognizing the ecosystem services that natural enemies provide beyond human health could help align natural enemy solutions with other Sustainable Development Goals, including biodiversity conservation and food production to fight poverty and hunger. In specific contexts where conservation of natural enemies confers a health benefit, conservation biological control could yield win-wins for health and nature. In North America and Europe, observational evidence suggests that functionally diverse predator communities are associated with lower tick infection prevalence of Lyme disease, caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi (Ostfeld et al., 2018). Some have suggested that landscape level protection or restoration of predators (e.g., foxes and wolves) could protect people against tick-borne disease. Protection of smaller predators, like the red fox, could enhance rodent predation and, consequently, tick infection probability (e.g.; (Hofmeester et al., 2017; Levi et al., 2012)). Restoration of larger wolf predators could indirectly reduce rodent populations by limiting coyote abundance (which are inversely associated with fox abundance) and by decreasing deer abundance (which are important reproductive hosts for ticks) (Kilpatrick et al., 2017; Levi et al., 2012). As this example shows, protecting some natural enemies could align goals for conservation and protecting human health.

Some natural enemy solutions may have important co-benefits for food security. In Vietnam, snail-eating fish have been stocked in aquaculture facilities for both biological control against fish-borne zoonotic trematodes (e.g., Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini) and food consumption (Hung et al., 2013). Reducing trematode infection in fish protects human health and local economies, because trematode infection can reduce fish survival and marketability (Hung et al., 2013). Evidence from a field study in Northern Vietnam suggests that stocking exotic juvenile black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) in aquaculture ponds reduces trematode prevalence in fish (Hung et al., 2013). Black carp have also been experimentally stocked in rice paddies for mosquito biological control. Studies in southern India and China showed that the nutrient input from fish increased rice yields, and in China malaria transmission was reduced after many years of stocking fish (Victor et al., 1994; Wu et al., 1991). In settings where mosquito-borne disease and snail-borne schistosomiasis are co-endemic, the scheme could theoretically limit mosquito and snail populations in rice fields simultaneously. A downside of approaches using black carp in particular is that invasive carp can devastate ecosystems (Ferber, 2001; Naylor et al., 2001). Therefore, carp introductions would ideally take advantage of sterile stocks or be strictly contained to specific areas to eliminate undue damage to native biodiversity. Looking ahead, use of native fish or non-native fish natural enemies under strict management schemes could provide important dual benefits of hunger alleviation or food security and infection control.

In some cases, natural enemy solutions may emerge from decision-making in other sectors. In India, vulture populations have dramatically declined because of a bio-accumulative drug used in livestock (diclofenac) that kills vultures when they eat treated carcasses. In response, a ban on the drug diclofenac was instituted in India in 2006 (Cuthbert et al., 2011). While it remains to be seen, the diclofenac ban may indirectly benefit human health and wellbeing. Vulture declines have coincided with a rise in the number of feral dogs (which compete with vultures for carrion) and, subsequently, human rabies risk (Swan et al., 2006). Vulture declines might also coincide with increased risk for bacterial pathogens, including anthrax, that can proliferate in carcasses that would otherwise be cleared by vultures (Fig. 1) (Markandya et al., 2008). This is a unique form of intraguild predation (Fig. 2c) where a predator (the vulture) and pathogen (anthrax) compete for a shared resource (the prey), while the predator also consumes the pathogen. It remains to be seen if the diclofenac ban in India and in surrounding nations will restore vultures and the ecosystem services that they provide. If so, the ban might additionally benefit food security via reduced livestock predation by wild dogs and sanitation services via clearing of carcasses that can contaminate water sources (Hopkins et al., 2020). As this example demonstrates, some natural enemy solutions may emerge from decision-making in other sectors, and could be one link in a network of positive outcomes for health, conservation, and well-being.

Challenges to research and operationalize natural enemy solutions have limited their uptake, but overcoming these challenges may be on the horizon

Experimental studies that simultaneously quantify human health outcomes and co-benefits of natural enemies are exceedingly rare. The lack of scientific focus on natural enemies for human disease control has likely been influenced by several high-profile examples of classical biological control gone wrong (i.e., the accidental or intentional introduction of exotic enemies in a new habitat). Mismanagement of mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis and Gambusia holbrooki) in freshwater ecosystems is one such example related to infectious disease control. Mosquitofish can establish self-sustaining populations and consume large numbers of mosquito larvae, though a causal relationship linking mosquitofish introductions to reduced human malaria incidence is lacking (Walshe et al., 2017). Even so, they have been transported globally for more than 100 years to control mosquitoes, and are now considered one of the most invasive fish species worldwide. Established populations can significantly impact native fauna, as they consume a wide range of insect, fish, and amphibian eggs (Nico et al., 2017). To overcome this barrier to natural enemy solutions, several established risk assessment frameworks could be used to screen and test candidate species for biological control via species introductions (Pyšek & Richardson, 2010). And, novel technological developments in aquaculture could minimize the impacts of invasive aquaculture species used as natural enemies of human pathogens or their animal hosts. Some aquaculture products, including Macrobrachium freshwater prawns (predators of schistosomiasis intermediate host snails) (Fig. 1), can be produced as monosex populations so that they are unable to establish self-sustaining populations in schistosome-endemic areas where the prawn is not native (Savaya et al., 2020). While this requires repeated deployment in order to maintain effective densities for disease control, thus adding cost to their initial investment, it helps to address fears of uncontrollable invasive species damage to ecosystems and it also aligns goals of food production with that of improved health and wellbeing.

Another related hindrance to the wide application of natural enemies for human disease control is the lack of investment in this area of research and development. As opposed to investment in pharmaceuticals and chemical control agents, conservation biological control approaches cannot be patented or commercialized. And, many conservation biological control approaches may offer long-term benefits that are more difficult to predict, quantify, and fund, than short-term “silver bullet” therapeutics and chemical environmental controls (Lewis et al., 1997). Even though many of the proposed solutions discussed in this Perspective piece are not amenable to fast return on investment, or even to commercialization or patenting, they could offer strong long-term impacts which makes their discovery and implementation a valuable contribution towards a sustainable future.

A result of the lack of investment in natural enemy research may be a lack of existing evidence on natural enemy impacts, especially regarding studies that trace the interlinkages among species interactions in the environment and the outcomes for human diseases. To foster more attention to natural enemy research, evidence on links between the ecological outcomes of natural enemy solutions (i.e., population changes in natural enemy targets) and epidemiological outcomes (i.e., changes in human disease outcomes) is badly needed. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been used to test biomedical, engineering, and behavioral interventions for many infectious diseases, and could be adapted for natural enemy strategies, too. Moving forward, confidence in natural enemy solutions may grow if we apply the same standards and investments in these tools as we do for biomedical and behavioral ones. And, testing natural enemy solutions through RCT-like frameworks may allow them to be evaluated on par with other existing or potential interventions, to determine if further research and investment is warranted.

Conclusions

Natural enemies of disease-causing organisms abound in nature, and their potential impact on human health may become more apparent as research on the ecological context of parasite and pathogen transmission grows. Looking ahead, some natural enemy solutions could complement conventional (chemical drug or insecticide-based) strategies to curb disease transmission by targeting environmental sources of infection. This could be especially important where conventional interventions are lacking. Some natural enemy solutions might simultaneously offer important co-benefits for nature conservation and food security, aligning natural enemy solutions with Sustainable Development Goals. Currently, however, evidence on the epidemiological impacts, cost-effectiveness, and feasibility of harnessing natural enemy solutions through natural enemy protection (i.e., species or habitat conservation) or implementation (i.e., population augmentation or introduction) is sparse, and more research is badly needed to assess the full potential of natural enemy solutions for infectious disease control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Armand Kuris and Matthew Bonds for early conversations and inspiration on natural enemies of parasites and parasite ecology, and Kate Lamy for her artwork.

Funding:

I.J.J. is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate 399 Research Fellowship Program, DGE – 1656518. I.J.J, S.H.S., and G.A.D.L. have been supported by NSF CNH grant no. 1414102, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation OPP1114050, NIH grant no. 1R01TW010286-01, and the SNAP-NCEAS-supported working group ‘Ecological levers for health: Advancing a priority agenda for Disease Ecology and Planetary Health in the 21st century’. G.A.D.L. and S.H.S. have also been supported by the National Science Foundation grants ICER-2024383 and DEB-2011179.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability:

This manuscript does not include any data.

References

- Amora SSA, Bevilaqua CML, Feijo FMC, Silva MA, Pereira R, Silva SC, Alves ND, Freire FAM, & Oliveira DM (2009). Evaluation of the fungus Beauveria bassiana (Deuteromycotina: Hyphomycetes), a potential biological control agent of Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera, Psychodidae). Biological Control, 50(3), 329–335. 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J, Kim Y-T, Ryu S, & Lee J-H (2016). Biocontrol and Rapid Detection of Food-Borne Pathogens Using Bacteriophages and Endolysins. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt BIP, Moran VC, Bigler F, & van Lenteren JC (2018). The status of biological control and recommendations for improving uptake for the future. BioControl, 63(1), 155–167. 10.1007/s10526-017-9831-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict MQ, & Robinson AS (2003). The first releases of transgenic mosquitoes: An argument for the sterile insect technique. Trends in Parasitology, 19(8), 349–355. 10.1016/S1471-4922(03)00144-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benelli G, Jeffries CL, & Walker T (2016). Biological Control of Mosquito Vectors: Past, Present, and Future. Insects, 7(4), Article 4. 10.3390/insects7040052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernaola Aponte G, Bada Mancilla CA, Carreazo NY, & Rojas Galarza RA (2013). Probiotics for treating persistent diarrhoea in children. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(8), Article 8. 10.1002/14651858.CD007401.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DE, & Cadarette D (2019). Infectious Disease Threats in the Twenty-First Century: Strengthening the Global Response. Frontiers in Immunology, 10. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charron DF (2012). Ecosystem Approaches to Health for a Global Sustainability Agenda. EcoHealth, 9(3), 256–266. 10.1007/s10393-012-0791-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay CA, Lehmer EM, St. Jeor S, & Dearing MD (2009). Sin Nombre virus and rodent species diversity: A test of the dilution and amplification hypotheses. PLoS ONE, 4(7). 10.1371/journal.pone.0006467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuthbert R, Taggart MA, Prakash V, Saini M, Swarup D, Upreti S, Mateo R, Chakraborty SS, Deori P, & Green RE (2011). Effectiveness of Action in India to Reduce Exposure of Gyps Vultures to the Toxic Veterinary Drug Diclofenac. PLOS ONE, 6(5), e19069. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedrick RM, Guerrero-Bustamante CA, Garlena RA, Russell DA, Ford K, Harris K, Gilmour KC, Soothill J, Jacobs-Sera D, Schooley RT, Hatfull GF, & Spencer H (2019). Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nature Medicine, 25(5), 730. 10.1038/s41591-019-0437-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, & Relman DA (2007). An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human–microbe mutualism and disease. Nature, 449(7164), 811–818. 10.1038/nature06245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye C (2014). After 2015: Infectious diseases in a new era of health and development. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1645). 10.1098/rstb.2013.0426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlanger TE, Keiser J, & Utzinger J (2008). Effect of dengue vector control interventions on entomological parameters in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medical and Veterinary Entomology, 22(3), 203–221. 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00740.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evan Secor William. (2014). Water-based interventions for schistosomiasis control. Pathogens and Global Health, 108(5), 246–254. 10.1179/2047773214Y.0000000149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans BR, & Leighton FA (2014). A history of One Health: -EN- A history of One Health -FR- Histoire du concept « Une seule santé » -ES- Historia de «Una sola salud». Revue Scientifique et Technique de l’OIE, 33(2), 413–420. 10.20506/rst.33.2.2298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farenhorst M, Hilhorst A, Thomas MB, & Knols BGJ (2011). Development of Fungal Applications on Netting Substrates for Malaria Vector Control. Journal of Medical Entomology, 48(2), 305–313. 10.1603/ME10134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faruque SM, Naser I.bin, Islam MJ, Faruque a S. G., Ghosh a N., Nair GB, Sack D. a, & Mekalanos JJ (2005). Seasonal epidemics of cholera inversely correlate with the prevalence of environmental cholera phages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(5), 1702–1707. 10.1073/pnas.0408992102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferber D (2001). Will Black Carp Be the Next Zebra Mussel? Science, 292(5515), 203–203. 10.1126/science.292.5515.203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes EKK, & Elias Pinheiro Bittencourt VR (2008). Entomopathogenic fungi against South American tick species. EXPERIMENTAL AND APPLIED ACAROLOGY, 46(1–4), 71–93. 10.1007/s10493-008-9161-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores HA, & O’Neill SL (2018). Controlling vector-borne diseases by releasing modified mosquitoes. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 16(8), 508–518. 10.1038/s41579-018-0025-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garchitorena A, Sokolow SH, Roche B, Ngonghala CN, Jocque M, Lund A, Barry M, Mordecai EA, Daily GC, Jones JH, Andrews JR, Bendavid E, Luby SP, LaBeaud AD, Seetah K, Guégan JF, Bonds MH, & De Leo GA (2017). Disease ecology, health and the environment: A framework to account for ecological and socio-economic drivers in the control of neglected tropical diseases. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1722), Article 1722. 10.1098/rstb.2016.0128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J, Jenkins NE, Blanford S, Thomas MB, & Baker TC (2013). Malaria Mosquitoes Attracted by Fatal Fungus. Plos One, 8(5). 10.1371/journal.pone.0062632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo-Calderón GI, Emrich SJ, MacCallum RM, Maslen G, Dialynas E, Topalis P, Ho N, Gesing S, VectorBase Consortium, Madey G, Collins FH, & Lawson D (2015). VectorBase: An updated bioinformatics resource for invertebrate vectors and other organisms related with human diseases. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(Database issue), D707–713. 10.1093/nar/gku1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg JZ, Yap C, Lytvyn L, Lo CK-F, Beardsley J, Mertz D, & Johnston BC (2017). Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, Article 12. 10.1002/14651858.CD006095.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Q, Dong BR, & Wu T (2015). Probiotics for preventing acute upper respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, Article 2. 10.1002/14651858.CD006895.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeester Tim R, Jansen Patrick A, Wijnen Hendrikus J, Coipan Elena C, Fonville Manoj, Prins Herbert HT, Sprong Hein, & van Wieren Sipke E (2017). Cascading effects of predator activity on tick-borne disease risk. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1859), 20170453. 10.1098/rspb.2017.0453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover CM, Sokolow SH, Kemp J, Sanchirico JN, Lund AJ, Jones IJ, Higginson T, Riveau G, Savaya A, Coyle S, Wood CL, Micheli F, Casagrandi R, Mari L, Gatto M, Rinaldo A, Perez-Saez J, Rohr JR, Sagi A, … De Leo GA (2019). Modelled effects of prawn aquaculture on poverty alleviation and schistosomiasis control. Nature Sustainability, 2(7), 611–620. 10.1038/s41893-019-0301-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins SR, Sokolow SH, Buck JC, De Leo GA, Jones IJ, Kwong LH, LeBoa C, Lund AJ, MacDonald AJ, Nova N, Olson SH, Peel AJ, Wood CL, & Lafferty KD (2020). How to identify win–win interventions that benefit human health and conservation. Nature Sustainability, 1–7. 10.1038/s41893-020-00640-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbostel VL, Ostfeld RS, & Benjamin M. a. (2005). Effectiveness of Metarhizium anisopliae (Deuteromycetes) against Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) engorging on Peromnyscus leucopus. Journal of Vector Ecology : Journal of the Society for Vector Ecology, 30(1), 91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz P, & Wilcox BA (2005). Parasites, ecosystems and sustainability: An ecological and complex systems perspective. International Journal for Parasitology, 35(7), 725–732. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez PJ (2019). Immunizations and vaccines: A decade of successes and reversals, and a call for ‘vaccine diplomacy.’ International Health, 11(5), 331–333. 10.1093/inthealth/ihz024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HT, & Yang P (1987). The Ancient Cultured Citrus Ant. BioScience, 37(9), 665–671. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes GL, Koga R, Xue P, Fukatsu T, & Rasgon JL (2011). Wolbachia Infections Are Virulent and Inhibit the Human Malaria Parasite Plasmodium Falciparum in Anopheles Gambiae. PLOS Pathogens, 7(5), e1002043. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung NM, Duc NV, Stauffer JR Jr., & Madsen H (2013). Use of black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) in biological control of intermediate host snails of fish-borne zoonotic trematodes in nursery ponds in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. PARASITES & VECTORS, 6. 10.1186/1756-3305-6-142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins DW (1964). Pathogens, parasites and predators of medically important arthropods. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 30, Suppl:1–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PT, Lund PJ, Hartson RB, & Yoshino TP (2009). Community diversity reduces Schistosoma mansoni transmission, host pathology and human infection risk. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 276(1662), 1657–1663. 10.1098/rspb.2008.1718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaaya GP (2000). Laboratory and field evaluation of entomogenous fungi for tick control. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 916, 559–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamareddine L (2012). The Biological Control of the Malaria Vector. Toxins, 4(9), 748–767. 10.3390/toxins4090748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassam Z, Lee CH, Yuan Y, & Hunt RH (2013). Fecal Microbiota Transplantation forClostridium difficileInfection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 108(4), 500. 10.1038/ajg.2013.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan JD, Hotez PJ, Amza A, Stoller NE, Gaynor BD, Porco TC, & Lietman TM (2013). Elimination and Eradication of Neglected Tropical Diseases with Mass Drug Administrations: A Survey of Experts. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 7(12), e2562. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keiser J, Maltese MF, Erlanger TE, Bos R, Tanner M, Singer BH, & Utzinger J (2005). Effect of irrigated rice agriculture on Japanese encephalitis, including challenges and opportunities for integrated vector management. Acta Tropica, 95(1), 40–57. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick AM, & Randolph SE (2012). Drivers, dynamics, and control of emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases. Lancet, 380(9857), 1946–1955. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61151-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick A. Marm, Salkeld Daniel J, Titcomb Georgia, & Hahn Micah B. (2017). Conservation of biodiversity as a strategy for improving human health and well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1722), 20160131. 10.1098/rstb.2016.0131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koretz RL, & Rotblatt M (2004). Complementary and alternative medicine in gastroenterology: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2(11), 957–967. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00461-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey LA (2007). Bacillus thuringiensis serovariety israelensis and bacillus sphaericus for mosquito control. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association, 23(sp2), 133–163. 10.2987/8756-971X(2007)23[133:BTSIAB]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey LA, & Lacey CM (1990). The medical importance of riceland mosquitoes and their control using alternatives to chemical insecticides. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association. Supplement, 2, 1–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty KD, DeLeo G, Briggs CJ, Dobson AP, Gross T, & Kuris AM (2015). A general consumer-resource population model. Science, 349(6250), 854–857. 10.1126/science.aaa6224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafferty KD, & Kuris AM (2002). Trophic strategies, animal diversity and body size. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 17(11), 507–513. 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02615-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laidemitt MR, Anderson LC, Wearing HJ, Mutuku MW, Mkoji GM, & Loker ES (2019). Antagonism between parasites within snail hosts impacts the transmission of human schistosomiasis. ELife, 8, e50095. 10.7554/eLife.50095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lardans V, & Dissous C (1998). Snail Control Strategies for Reduction of Schistosomiasis Transmission. Parasitology Today, 14(10), 413–417. 10.1016/S0169-4758(98)01320-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro A, Han WW, Manrique-Saide P, George L, Velayudhan R, Toledo J, Ranzinger SR, & Horstick O (2015). Community effectiveness of copepods for dengue vector control: Systematic review. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 20(6), 685–706. 10.1111/tmi.12485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner H, & Berg C (2017). A Comparison of Three Holistic Approaches to Health: One Health, EcoHealth, and Planetary Health. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 4. 10.3389/fvets.2017.00163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi T, Kilpatrick AM, Mangel M, & Wilmers CC (2012). Deer, predators, and the emergence of Lyme disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(27), 10942–10947. 10.1073/pnas.1204536109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis WJ, Lenteren J. C.van, Phatak SC, & Tumlinson JH (1997). A total system approach to sustainable pest management. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 94(23), 12243–12248. 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo NC, Gurarie D, Yoon N, Coulibaly JT, Bendavid E, Andrews JR, & King CH (2018). Impact and cost-effectiveness of snail control to achieve disease control targets for schistosomiasis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(4), E584–E591. 10.1073/pnas.1708729114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losey JE, & Vaughan M (2006). The Economic Value of Ecological Services Provided by Insects. BioScience, 56(4), 311. 10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[311:TEVOES]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lugassy L, Amdouni-Boursier L, Alout H, Berrebi R, Boëte C, Boué F, Boulanger N, Durand T, de Garine-Wichatitsky M, Larrat S, Moinet M, Moulia C, Pagès N, Plantard O, Robert V, & Livoreil B (2021). What evidence exists on the impact of specific ecosystem components and functions on infectious diseases? A systematic map. Environmental Evidence, 10(1), 11. 10.1186/s13750-021-00220-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markandya A, Taylor T, Longo A, Murty MN, Murty S, & Dhavala K (2008). Counting the cost of vulture decline-An appraisal of the human health and other benefits of vultures in India. Ecological Economics, 67(2), 194–204. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.04.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon MC, Cheng SH, Dupre S, Edmond J, Garside R, Glew L, Holland MB, Levine E, Masuda YJ, Miller DC, Oliveira I, Revenaz J, Roe D, Shamer S, Wilkie D, Wongbusarakum S, & Woodhouse E (2016). What are the effects of nature conservation on human well-being? A systematic map of empirical evidence from developing countries. Environmental Evidence, 5(1), 8. 10.1186/s13750-016-0058-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morens DM, Folkers GK, & Fauci AS (2004). The challenge of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Nature, 430(6996), 242–249. 10.1038/nature02759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo SE, Ellsworth PC, & Frisvold GB (2015). Economic Value of Biological Control in Integrated Pest Management of Managed Plant Systems. Annual Review of Entomology, 60(1), 621–645. 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-021005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauen R (2007). Insecticide resistance in disease vectors of public health importance. Pest Management Science, 63(7), 628–633. 10.1002/ps.1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor R, & Ehrlich P (1997). Natural pest control services and agriculture. In Daily GC (Ed.), Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence On Natural Ecosystems (pp. 151–174). [Google Scholar]

- Naylor RL, Williams SL, & Strong DR (2001). Aquaculture—A Gateway for Exotic Species. Science, 294(5547), 1655–1656. 10.1126/science.1064875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson EJ, Harris JB, Morris JG, Calderwood SB, & Camilli A (2009). Cholera transmission: The host, pathogen and bacteriophage dynamic. Nature Reviews. Microbiology, 7(10), 693–702. 10.1038/nrmicro2204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng KM, Ferreyra JA, Higginbottom SK, Lynch JB, Kashyap PC, Gopinath S, Naidu N, Choudhury B, Weimer BC, Monack DM, & Sonnenburg JL (2013). Microbiota-liberated host sugars facilitate post-antibiotic expansion of enteric pathogens. Nature, 502(7469), 96–99. 10.1038/nature12503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nico L, Fuller P, Jacobs G, Cannister M, Larson J, Fusaro A, T. H. M. and M.N. (2017). Gambusia affinis. In USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database. [Google Scholar]

- Nobrega FL, Costa AR, Kluskens LD, & Azeredo J (2015). Revisiting phage therapy: New applications for old resources. Trends in Microbiology, 23(4), 185–191. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostfeld RS, & Holt RD (2004). Are predators good for your health? Evaluating evidence for top-down regulation of zoonotic disease reservoirs. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2(1), 13–20. 10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0013:APGFYH]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostfeld RS, Levi T, Keesing F, Oggenfuss K, & Canham CD (2018). Tick-borne disease risk in a forest food web. Ecology, 99(7), 1562–1573. 10.1002/ecy.2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pointier JP, & Jourdane J (2000). Biological control of the snail hosts of schistosomiasis in areas of low transmission: The example of the Caribbean area. Acta Tropica, 77(1), 53–60. 10.1016/S0001-706X(00)00123-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pointier J-P, David P, & Jarne P (2011). The Biological Control of the Snail Hosts of Schistosomes: The Role of Competitor Snails and Biological Invasions. In Toledo R & Fried B (Eds.), Biomphalaria Snails and Larval Trematodes (pp. 215–238). Springer; New York. 10.1007/978-1-4419-7028-2_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poulin B, Lefebvre G, & Paz L (2010). Red flag for green spray: Adverse trophic effects of Bti on breeding birds. Journal of Applied Ecology, 47(4), 884–889. 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01821.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Power AG (2010). Ecosystem services and agriculture: Tradeoffs and synergies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365(1554), 2959–2971. 10.1098/rstb.2010.0143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyšek P, & Richardson DM (2010). Invasive Species, Environmental Change and Management, and Health. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 35(1), 25–55. 10.1146/annurev-environ-033009-095548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regis L, Silva-Filha MH, Nielsen-LeRoux C, & Charles J-F (2001). Bacteriological larvicides of dipteran disease vectors. 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remais JV, & Eisenberg JNS (2012). Balancing Clinical and Environmental Responses to Infectious Diseases. Lancet, 379(9824), 1457–1459. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61227-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr JR, Civitello DJ, Halliday FW, Hudson PJ, Lafferty KD, Wood CL, & Mordecai EA (2020). Towards common ground in the biodiversity–disease debate. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4(1), 24–33. 10.1038/s41559-019-1060-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samish M, Ginsberg H, & Glazer I (2004). Biological control of ticks. Parasitology, 129(S1), S389–S403. 10.1017/S0031182004005219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaya A, Glassner H, Livne-Luzon S, Chishinski R, Molcho J, Aflalo ED, Zilberg D, & Sagi A (2020). Prawn monosex populations as biocontrol agents for snail vectors of fish parasites. Aquaculture, 520, 735016. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scholte EJ, Knols BGJ, & Takken W (2006). Infection of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae with the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae reduces blood feeding and fecundity. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 91(1), 43–49. 10.1016/j.jip.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Valenzuela CA, & Camilli A (2019). Niche adaptation limits bacteriophage predation of Vibrio cholerae in a nutrient-poor aquatic environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(5), 1627–1632. 10.1073/pnas.1810138116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolow SH, Huttinger E, Jouanard N, Hsieh MH, Lafferty KD, Kuris AM, Riveau G, Senghor S, Thiam C, N’Diaye A, Faye DS, & De Leo G. a. (2015). Reduced transmission of human schistosomiasis after restoration of a native river prawn that preys on the snail intermediate host. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(31), 9650–9655. 10.1073/pnas.1502651112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolow SH, Nova N, Pepin KM, Peel AJ, Pulliam JRC, Manlove K, Cross PC, Becker DJ, Plowright RK, McCallum H, & De Leo GA (2019). Ecological interventions to prevent and manage zoonotic pathogen spillover. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 374(1782), 20180342. 10.1098/rstb.2018.0342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumare MKF, & Cilek JE (2011). The Effectiveness of Mesocyclops longisetus (Copepoda) for the Control of Container-Inhabiting Mosquitoes In Residential Environments1. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association, 27(4), 376–383. 10.2987/11-6129.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer JR, & Madsen H (2012). Schistosomiasis in Lake Malawi and the Potential Use of Indigenous Fish for Biological Control. 10.5772/26018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer JR, Madsen H, McKaye K, Konings A, Bloch P, Ferreri CP, Likongwe J, & Makaula P (2006). Schistosomiasis in Lake Malawi: Relationship of Fish and Intermediate Host Density to Prevalence of Human Infection. EcoHealth, 3(1), 22–27. 10.1007/s10393-005-0007-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sulieman Y, & Pengsakul T (2013). Competitive Capability of Exorchis sp (Trematoda: Cryptogonimidae) Against Schistosoma japonicum (Trematoda: Schistosomatoidae) on Larval Development within the Intermediate Host Snail, Oncomelania hupensis. EGYPTIAN JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL PEST CONTROL, 23(1), 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Swan G, Naidoo V, Cuthbert R, Green RE, Pain DJ, Swarup D, Prakash V, Taggart M, Bekker L, Das D, Diekmann J, Diekmann M, Killian E, Meharg A, Patra RC, Saini M, & Wolter K (2006). Removing the threat of diclofenac to critically endangered Asian vultures. PLoS Biology, 4(3), 0395–0402. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symondson WOC, Sunderland KD, & Greenstone MH (2002). Can Generalist Predators be Effective Biocontrol Agents? Annual Review of Entomology, 47(1), 561–594. 10.1146/annurev.ento.47.091201.145240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang C-T, Lu M-K, Guo Y, Wang Y-N, Peng J-Y, Wu W-B, Li W-H, Weimer BC, & Chen D (2009). Development of larval Schistosoma japonicum blocked in Oncomelania hupensis by pre-infection with larval Exorchis sp. The Journal of Parasitology, 95(6), 1321–1325. 10.1645/GE-2055.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetreau G, Stalinski R, David J-P, & Després L (2013). Monitoring resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. Israelensis in the field by performing bioassays with each Cry toxin separately. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, 108(7), 894–900. 10.1590/0074-0276130155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lenteren JC, Bolckmans K, Köhl J, Ravensberg WJ, & Urbaneja A (2018). Biological control using invertebrates and microorganisms: Plenty of new opportunities. BioControl, 63(1), 39–59. 10.1007/s10526-017-9801-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Victor TJ, Chandrasekaran B, & Reuben R (1994). Composite fish culture for mosquito control in rice fields in southern India. The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 25(3), 522–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walshe DP, Garner P, Adeel AA, Pyke GH, & Burkot TR (2017). Larvivorous fish for preventing malaria transmission. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, Article 12. 10.1002/14651858.CD008090.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, & Aksoy S (2011). Microbiome influences on insect host vector competence. Trends in Parasitology, 27(11), 514–522. 10.1016/j.pt.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmee S, Haines A, Beyrer C, Boltz F, Capon AG, de Souza Dias BF, Ezeh A, Frumkin H, Gong P, Head P, Horton R, Mace GM, Marten R, Myers SS, Nishtar S, Osofsky SA, Pattanayak SK, Pongsiri MJ, Romanelli C, … Yach D (2015). Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. The Lancet, 386(10007), 1973–2028. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2011). Comprehensive Guidelines for Prevention and Control of Dengue and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever (SEARO Technical Publication Series No. 60). World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. http://www.who.int/denguecontrol/control_strategies/biological_control/en/ [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2016). Global Health Estimates 2015: Disease burden by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2015. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wood CL, Lafferty KD, DeLeo G, Young HS, Hudson PJ, & Kuris AM (2014). Does biodiversity protect humans against infectious disease? Ecology, 95(4), 817–832. 10.1890/13-1041.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N, Liao GH, Li DF, Luo YL, & Zhong GM (1991). The advantages of mosquito biocontrol by stocking edible fish in rice paddies. The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health, 22(3), 436–442. 10.2307/2641057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen M, Cairns LS, & Camilli A (2017). A cocktail of three virulent bacteriophages prevents Vibrio cholerae infection in animal models. Nature Communications, 8(1), 14187. 10.1038/ncomms14187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript does not include any data.