Abstract

Background –

Limited information is available for dogs on threshold concentrations (TCs), and the protein composition of common allergenic extracts produced by different manufacturers.

Hypothesis/Objectives –

To characterize the protein heterogeneity of tree, grass, weed and mite allergens from different lots of allergenic extracts, and to determine intradermal TCs for healthy dogs using extracts from two manufacturers.

Animals –

Twenty five privately owned, clinically healthy dogs and ten purpose-bred beagle dogs.

Methods and materials –

Protein concentration and heterogeneity of 11 allergens from two manufacturers were evaluated using a Bradford-style assay and SDS-PAGE. Intradermal testing was performed with 11 allergens from each company at four dilutions. Immediate reactions were subjectively scored (0 to 4+), and objectively measured (mm) and their percentage concordance evaluated. Model-based TCs were determined by fitting positive reactions (≥2+) at 15 min to generalized estimating equations.

Results –

Allergen extract protein quantity and composition varied within and between manufacturers despite sharing the same PNU/mL values. Model-based TCs of one weed, five trees, two grasses and a house dust mite were determined for extracts from Manufacturer 1 (M1), and for extracts of three weeds, three trees and two grasses from Manufacturer 2 (M2). Receiver operating characteristic curve analyses determined a percentage concordance of the objective and subjective measurements of 77.3% for M1 and 75% for M2 allergens.

Conclusions and clinical importance –

Veterinary allergen extracts labelled as the same species and PNU/mL are not standardized; they show heterogeneity in composition and potency within and between manufacturers. Variability in extract content may require adjustment of intradermal testing concentrations.

Résumé

Contexte –

On en sait peu chez le chien sur les concentrations seuils (TCs) et la composition protéique des extraits allergéniques produits par les différents fabricants.

Hypothéses/Objectifs –

Déterminer l’hétérogénéité proteique d’allergènes d’arbre, de graminées, d’herbacées et d’acariens pour des lots différents et de d eterminer les TCs intradermiques pour les chiens sains á l’aide d’extraits de deux fabricants.

Sujets –

Vingt cinq chiens de propriétaires cliniquement sains et dix beagles d’élevage.

Matériel et méthode –

La concentration protéique et l’hétérogénéit e de 11 allergénes de deux fabricants ont été évaluées par un test de Bradford et SDS-PAGE. Les tests intradermiques ont été réalisés avec 11 allergènes de chaque fabricant à quatre dilutions. Les réactions immediates ont été notées subjectivement (0 á 4+) et mesurees objectivement (mm) et leu pourcentage de concordance évalué. Les TCs bas ees sur modele ont été déterminées par réactions positives (≥2±)á des equations estimees généralisées.

Resultats –

La quantité et la composition protéique des extraits allergéniques variaient au sein et entre les fabricants malgré le partage des mȇmes valeurs de PNU/mL. Les TCs basées sur modéle d’une graminée, cinq arbres, deux herbacees et un acarien de poussiére de maison ont été déterminés pour les extraits de fabricant 1 (M1) et pour les extraits de trois graminées, trois arbres et deux herbacées pour le fabricant 2 (M2). Les analyses de courbe caractéristique ont détermines un pourcentage de concordance des mesures objectives et subjectives de 77.3% pour les allergénes de M1 et 75% pour M2.

Conclusions et importance clinique –

Les extraits allergéniques vétérinaires étiquetés comme les mȇmes espéces et PNU/mL ne sont pas standardisés; ils montrent une hétérogénéit e de composition et de puissance au sein et entre les fabricants. La variabilité des contenus d’extraits peut nécessiter des ajustements des concentrations des tests intradermiques.

Resumen

Introducción –

en perros hay informacion limitada acerca de concentraciones umbral (TC) y la composición proteica de extractos alergénicos comunes producidos por diferentes fabricantes.

Hipótesis/Objetivos –

caracterizar la heterogeneidad proteica de alergenos de árboles, hierbas, maleza y ácaros de diferentes lotes de extractos alergénicos y determinar TC intradérmicas para perros sanos utilizando extractos de dos fabricantes.

Animales –

veinticinco perros de propietarios particulares, clınicamente sanos y diez perros Beagle criados con este proposito.

Metodos y materiales –

la concentración de protéınas y la heterogeneidad de 11 alergenos de dos fabricantes se evaluaron mediante un ensayo de estilo Bradford y SDS-PAGE. La prueba intradérmica se realizó con 11 alérgenos de cada compaῆía en cuatro diluciones. Las reacciones inmediatas se puntuaron subjetivamente (0 a 4+) y se midieron objetivamente (mm) y se evaluó su porcentaje de concordancia. Los TC se determinaron segun modelos ajustando las reacciones positivas ( ≥2+) a los 15 minutos a ecuaciones de estimación generalizadas.

Resultados –

la cantidad y la composicion de las proteĺnas del extracto de alérgenos variaron en el mismo fabricante y entre los fabricantes a pesar de compartir los mismos valores de PNU/ml. Se determinaron las TC basadas en modelos de una mala hierba, cinco árboles, dos gramĺneas y un acaro del polvo domestico para extractos del Fabricante 1 (M1) y para extractos de tres malas hierbas, tres árboles y dos gramıneas del Fabricante 2 (M2). Los análisis de la curva caracterıstica operativa del receptor determinaron una concordancia porcentual de las mediciones objetivas y subjetivas de 77,3% para M1 y 75% para alergenos M2.

Conclusiones e importancia clınica –

los extractos alergénicos veterinarios etiquetados como la misma especie y PNU/mL no están estandarizados; muestran heterogeneidad en la composición y la potencia en el mismo fabricante y entre los fabricantes. La variabilidad en el contenido del extracto puede requerir el ajuste de las concentraciones de prueba intradérmicas.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund –

Es gibt nur limitierte Information ὒber die Schwellenkonzentrationen (TCs) und die Protein-zusammensetzung von häufigen Allergenextrakten fὒr Hunde, die von verschiedenen Herstellern produziert werden.

Hypothese/Ziele –

Eine Charakterisierung der Heterogenität von Proteinen von Baum-, Gras-, Unkrautund Milbenallergenen aus unterschiedlichen Chargen von Allergenextrakten und die Bestimmung der intradermalen TCs fὒr gesunden Hunde bei Verwendung von Extrakten von zwei Herstellern.

Tiere –

Fὒnfundzwanzig klinisch gesunde Hunde in Privatbesitz und zehn Zweck-gezὒchtete Beagles.

Methoden und Material –

Die Proteinkonzentrationen und die Heterogenität von 11 Allergenen von zwei Herstellern wurden mittels Bradford-Style-Assay und SDS-PAGE untersucht. Es wurde mit 11 Allergenen eines jeden Herstellers ein Intradermaltest in vier Verdunnungen durchgef€ uhrt. Die Sofortreaktionen wurden subjektiv bewertet (0 bis 4+) und objektiv gemessen (mm) und ihre prozentuelle Ubereinstimmung evaluiert. Es wurden Modell-basierte TCs bestimmt, wobei positive Reaktionen (≥2+) nach 15 Minuten generalisierten geschätzten Gleichungen angepasst wurden.

Ergebnisse –

Die Quantität des Allergenextraktionsproteins und seine Zusammensetzung variierte innerhalb und zwischen den Herstellern, obwohl sie dieselben PNU/mL Werte zeigten. Modell-basierte TCs eines Unkrauts, von fὒnf Bäumen, zwei Gräsern und einer Hausstaubmilbe wurden fur die Extrakte von Hersteller 1 (M1) und fὒr die Extrakte von drei Unkräutern, drei Bäumen und zwei Gräsern von Hersteller 2 (M2) bestimmt. Die Analyse mittels Receiver-Operating-Characteristic-Kurve bestimmte eine prozentuelle ὒbereinstimmung der objektiven und subjektiven Messungen von 77,3% f€ur M1 und 75% fὒr M2 Allergene.

Schlussfolgerungen und klinische Bedeutung –

Veterinärmedizinische Allergenextrakte, die derselben Spezies und PNU/mL entsprechen sind nicht standardisiert; sie zeigen eine Heterogenitat in ihrer Zusammensetzung und Stärke innerhalb und zwischen den Herstellern. Die Variabilität in der Zusammensetzung des Extraktes konnte eine Anpassung der verwendeten Konzentrationen beim Intradermaltest nÖtig machen.

要約

背景 –

異なるメーカーで製造された共通のアレルゲン抽出物のタンパク組成および犬における閾値濃度 (TC)について、利用できる情報は限られている。

仮説/目的 –

本研究の目的は、2つのメーカーの抽出物を使用してアレルゲン抽出物の異なるロットからの樹木、草、雑草およびダニアレルゲンのタンパク質の不均一性を特徴づけること、および健康な犬の皮内TCを決定することである。

被験動物 –

飼育下にある臨床的に健康な犬25頭と研究目的に飼育されたビーグル犬10頭。

方法および材料 –

2つの製造業者から11種類のアレルゲンのタンパク濃度および不均一性をBradford-style assayおよびSDS-PAGEを用いて評価した。皮内試験は各会社の11種類のアレルゲンを用いて4回希釈で実施した。即時反応を主観的に採点(0〜4+)、客観的に測定(mm)し、それらの比率の一致度を評価した。閾値濃度(TC)のモデルベースは、一般化された推定式に対し15分の陽性反応(≧2 +)を適合し決定した。

結果 –

アレルゲン抽出物のタンパク量および組成は、同じPNU/mL値を共有しているにもかかわらず、製造業者内および製造業者間で変化した。製造者1(M1)の抽出物から1つの雑草、5つの樹木、2つの草およびダストダニを、製造者2(M2)の抽出物から3つの雑草、3つの樹木および2つの草の閾値濃度(TC)のモデルベースを決定した。M1の77.3%およびM2アレルゲンの75%の客観的および主観的測定値の比率の一致度を受信者動作特性曲線解析により判定した。

結論と臨床的重要性 –

同種およびPNU/mLと表示した獣医療アレルゲン抽出物は標準化されていない。それは製造者内および製造者間において組成および効力に不均一性を示すからである。抽出物含有量の変 動は、皮内試験濃度の調整を必要とする可能性がある。

摘要

背景 –

对于犬的阈值浓度(TCs),以及由不同制造商生产的常见过敏性提取物的蛋白质组成,可获得的信息很有限。

假设/目的 –

对不同树木、草、杂草和螨虫过敏原提取物,描述其蛋白质差异性特征,并使用两家不同制造商生产的提取物,测定健康犬的皮内TCs。

动物 –

临床检查健康的二十五只私家犬,以及十只繁殖用比格犬

材料和方法 –

使用Bradford方法和SDS-PAGE,评估来自两家制造商的11种过敏原的蛋白质浓度和异质性,皮内试验选用两家公司的11种过敏原,分别四倍稀释。对快速反应进行主观评分(0至4+)、客观测量(mm),并评估其百分比一致性,将15分钟时阳性反应(≥2+)拟合到广义估计方程,来确定基于模型的TCs。

结果 –

尽管具有相同的PNU / mL值,但过敏原提取物蛋白质的量和组成,在制造商内部和两家之间存在差异。选自制造商1(M1)的一种杂草、五种树、两种草和屋尘螨的提取物,以及来自制造商2(M2)的三种杂草, 三种树和两种草的提取物,确定其基于模型的TCs。观测者操作特性曲线分析并确定了客观和主观测量的百分比一致性,M1符合率为77.3%,M2为75%。

结论和临床价值 –

标签上种类和PNU/mL相同的兽医临床过敏原提取物仍未标准化; 他们显示了制造商内部和制造商之间产品成分和效力的差异性;这种提取物含量的变化,可能需要调整皮内测试浓度。

Resumo

Contexto –

Poucas informacoes estão disponíveis para cães sobre os limiares irritativos (LIs), e sobre a composição proteica de extratos alergênicos comuns produzidos por diferentes fabricantes.

Hipótese/Objetivos –

Caracterizar a heterogeneidade proteica de alérgenos de árvores, gramíneas, herbáceas e ácaros de diferentes lotes de extratos alergênicos, e determinar os LIs intradêrmicos para cães saudáveis utilizando extratos de dois fabricantes.

Animais –

Vinte e cinco cães de proprietários, clinicamente saudáveis e dez cães beagles de laboratório criados para este propósito.

Métodos e materiais –

A concentração proteica e a heterogeneidade de 11 alérgenos de dois fabricantes foram avaliados utilizando um ensaio tipo Bradford e SDS-PAGE. Os testes intradérmicos foram realizados com 11 alérgenos de cada fabricante em quatro diluições. As reacões imediatas foram avaliadas subjetivamente (0 a 4+), e mensuradas (mm) objetivamente e avaliou-se também a sua porcentagem de concordância. Os LIs baseados em modelo foram determinados encaixando-se as reações positivas (≥2+) dentro de 15 minutos em equações estimativas generalizadas.

Resultados –

A quantidade de proteínas e a composicão dos extratos alergênicos variou nas amostras dô mesmo fabricante e entre fabricantes, ainda que apresentassem os mesmos valores de PNU/mL. Os LIs baseados em modelo para uma herbácea, cinco árvores, duas gramíneas e um ácaro da poeira doméstica foram determinados para extratos do Fabricante 1 (F1), e para extratos de três herbáceas, três árvores e duas gramíneas do Fabricante 2 (F2). As análises da curva característica operacional do receptor determinaram uma porcentagem de concordância de 77,3% entre as mensurações objetivas e subjetivas para os alérgenos de M1 e de 75% para os de M2.

Conclusões e importância clínica –

Os extratos alergênicos veterinários registrados como sendo da mesma espécie e concentração em PNU/mL não são padronizados; eles demonstram heterogeneidade na sua composição e potencia dentro das amostras do mesmo fabricante e entre fabricantes. A variabilidade na composição dos extratos pode demandar ajustes nas concentrações dos testes intradérmicos.

Introduction

Identifying potential environmental triggers in atopic patients are accomplished using allergen testing. In humans and animals, the intradermal test (IDT) measures levels of tissue-bound immunoglobulin E (IgE), whereas various types of serum allergen tests identify circulating serum IgE antibodies.1–5 Selection of the identified allergens for inclusion in allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT) is based on the presence of regional sensitizers, relative allergenicity, clinical relevance, compatibility of extracts on mixing and cross-reactivity with other allergens.6 Effective ASIT reduces clinical signs and concurrent pharmacotherapy while improving quality of life.

Allergen extracts are aqueous preparations produced from natural source materials that contain various amounts of major, minor and isoallergens, as well as other nonallergenic compounds.7 The efficacy of ASIT depends exclusively on the content of allergen preparations, and manufacturers are challenged to produce allergen extracts with consistent compositions. Human IDTs and skin prick tests (SPT) use a combination of standardized and nonstandardized extracts. Comparing standardized allergen extracts to reference standards ensures relative equivalent potencies. This makes skin testing and employing ASIT with standardized extracts less variable and facilitates the comparison of study results. Importantly, standardization ensures safety and efficacy of ASIT by minimizing the risks of variations in allergen dose when switching from one lot of manufactured extract to another and provides an objective measure of stability for each lot of allergen extract over time. Standardized allergens are extracted in glycerinated saline, and the utility of these extracts for IDT in veterinary medicine has not been validated. A challenge in veterinary medicine is the interpretation of an IDT reaction due to the variability of the aqueous extracts, given that there are no standardized allergen extracts for use in IDT.

Nonstandardized allergens do not have reference standards established, thereby allowing for greater variations in quality (potency and immune reactivity) both among lots and between suppliers. Inconsistencies in both protein and major allergen content in human allergen extracts had been demonstrated between manufacturers.9–11

Optimal allergen extract threshold concentrations (TCs) for IDT have been defined as the highest concentration of an allergen that results in positive reactivity in ≤10% of a normal population.12 This TC is used to minimize false positive and negative reactions in dogs with a clinical diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD).12 Recommended concentrations of allergen extract dilutions for use in IDT in veterinary medicine for pollens are 1,000 PNU/mL and for dust mites are 250 PNU/mL.3,13 However, an earlier study revealed that house dust mite dilutions greater than 31.25 PNU/mL gave false-positive reactions.14 When a greater proportion of clinically nonaffected animals react to an injected allergen at a given concentration, false-positive reactions to those specific allergens are also more likely to occur in dogs with AD. False-positive reactions resemble an erythematous wheal of an IgE-mediated reaction to an allergen and can represent a clinically irrelevant sensitization, an irritant reaction not mediated by IgE, contaminated test allergens, poor injection technique, irritable skin, dermatographism and mitogenic allergens.3,15

Studies to evaluate differential IDT reactivity and irritant TCs between extracts provided by different manufacturers do suggest variability.16,17 As there is no standardization for veterinary allergen extracts, a significant need exists to establish TCs for use in IDT. Additionally, a deficiency exists in comparing allergen extracts from multiple manufacturers. Establishing TCs in nonallergic, clinically normal dogs, with allergens from both manufacturers, should aid with interpretation of IDT reactions and results from future allergy studies.

We hypothesized that allergen extracts produced by two different companies would have different IDT TCs when evaluated in a population of apparently healthy dogs. The aims of the study were: (i) to survey the protein heterogeneity and concentration of tree, grass, weed and mite allergen extract lots between and within manufacturers; and (ii) to determine IDT allergen extract TCs for healthy dogs using extracts from two different veterinary allergen manufacturers.

Methods and materials

This was a prospective study. The study protocol and owner consent form were approved by the Ohio State University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use and the Clinical Research Committees.

Allergens

Eleven commercially available aqueous allergen extracts were used for protein analysis and for IDT. The allergen extracts included three weeds (giant/short ragweed mix, lamb’s quarter and English plantain), five trees (American elm, black walnut, box elder, red cedar and white oak), two grasses (Johnson and Timothy) and one house dust mite (Dermatophagoides farinae). Allergens were obtained from ALK-Abello (Round Rock, TX, USA) and Stallergenes Greer Laboratories, Inc. (Lenoir, NC, USA). All allergen extracts were used within their expiration date.

Two to three lots of the equivalent species of allergen extracts manufactured by the same company were mixed for IDT testing solutions. As we hypothesized that allergen extracts would vary between lots, mixing was done to reduce variation in protein concentration and composition. Mixing of lots would mimic the variation in lots that would occur when clinicians have depleted allergen extract stocks. Mixes were made by combining aliquots from each allergen extract lot to equal the lowest PNU/mL or weight/volume (w/v) concentration of any lot.

Total protein quantification

Total protein concentration (lg/mL) was determined by a Bradford-style assay [#23236, Pierce™ Coomassie Plus (Bradford) Assay Kit, ThermoFisher Scientific; Waltham, MA, USA]. Bradford-style assays were performed in three to four replicates for each sample via the microplate method, using bovine serum albumin as a protein standard.18 Protein concentrations for each allergen are represented as the mean (±SD) of the three to four replicates (Table S1).

Protein composition and SDS-PAGE

The protein composition of each ALK-Abello allergen extract lot and mixes were analysed using equal PNU/mL concentrations and volume (30 μL/lane) by SDS-PAGE. Extracts were diluted to the same PNU concentration and treated with the reducing agent, dithiothreitol (DTT) and loaded in buffer (#1610737 29 Laemmli Sample Buffer, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.; Hercules, CA, USA), then heated to >95°C for 5 min before loading into the wells of pre-cast 10–20% tris-glycine gels (#XP10200BOX, Novex™ WedgeWell, Life Science, Invitrogen; Waltham, MA, USA). Electrophoresis was conducted at 100 V/cm for 1 h to separate the proteins in 19 tris-glycine SDS running buffer [#LC2675, Novex™ Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer (109), Invitrogen] and subsequently stained with Coomassie stain (#LC6060, SimplyBlue™ SafeStain, Invitrogen) to visualize linear bands. The size of the separated proteins was identified by molecular weight using a pre-stained protein standard (#161–0375, Precision Plus Protein™ Kaleidoscope™ Prestained Protein Standard, Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Animals

Twenty five privately owned, clinically healthy dogs and ten purpose-bred beagles were used in this study. Privately owned dogs were a minimum age of 2 years old and had lived in their current owner’s homes for at least one year. A questionnaire (see Supporting Information) was used to ensure that none of the privately owned dogs had any history of pruritus, dermatological and/or otic diseases. If an owner answered “yes” to any question regarding pruritus, cutaneous or otic lesions, history of antibiotic use for skin or ears, ocular or nasal discharge or vomiting and diarrhoea, the dog was excluded from the study. A complete blood count and biochemistry panel were performed at the time of enrolment. Prior to the IDT, all privately owned dogs were fed a standardized diet (BLUE Basics® Grain-Free Turkey Potato Recipe, Blue Buffalo Co Ltd; Wilton, CT, USA) with an omega 6:3 ratio of 7.8, plus treats (BLUE Basics® Turkey & Potato Biscuits, Blue Buffalo Co.) for a minimum of two months.

Purpose-bred beagles were a minimum of 1-year-old at the time of enrolment. They were kept in kennels that were sprayed down with water repeatedly throughout the day and cleaned thoroughly with a disinfectant scrub each morning. The dogs were kept on a rubber-coated metal floor with plastic bowls for food and water; had interactive indestructible food toys filled with their laboratory diet; and had no blankets. All of the dogs’ medical records were evaluated to ensure they did not have a history of dermatological and otic disease. Only dogs without abnormalities on general physical, dermatological and otoscopic examinations were included. A complete blood count and biochemistry profile were not required for enrolment. All purpose-bred beagles were fed a standardized diet (Laboratory Canine Diet 5006*, LabDiet®; St Louis, MO, USA), with an omega 6:3 ratio of 4.5, for a minimum of two months before enrolment.

Dogs could have never received antipruritic medications, including topical, oral or injectable glucocorticoids, antihistamines, Staphage Lysate®, pentoxifylline and tacrolimus. Dogs could have previously received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, essential fatty acid supplementation, gabapentin or monoamine oxidase inhibitors for reasons other than pruritus. All dogs had been without any medication that could influence intradermal testing for at least eight weeks, including the aforementioned supplements and medications. All dogs were receiving products for preventative flea and heartworm control.

Intradermal testing

All allergens and dilutions of allergens for IDT were stored in glass vials at 4°C as recommended by the manufacturer. The allergens were removed 10 min before the IDT was performed. Each of the 11 allergens from both companies was diluted with 0.4% phenolated saline (ALK-Abello) to obtain four different test concentrations in PNU/mL and w/v (Table S2). Dilutions were remade every 4 weeks as needed from their respective stock vials. All individual allergen dilutions contained at least two and up to three different lots of that specific allergen from the same company. The mixed-lot allergens were used in all the dogs.

Dogs were sedated with dex-medetomidine hydrochloride (Dexdomitor®, Zoetis; Kalamazoo, MI, USA) at 8–12 μg/kg intravenously. The skin over the left or right ventro-lateral thorax wall was carefully clipped using a number 40 clipper blade (PowerPro® Ultra Cordless Clipper Kit, Oster; McMinnville, TN, USA). A waterproof permanent marker was used to create a testing template, which consisted of three horizontal rows of 20 dots. Intradermal injections of control solutions and allergens were made above and below the dots. Syringes (1 mL 27G, BD; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) with a permanently attached 27 gauge (3/8 inch intradermal bevel) needle were preloaded with 0.25 mL of the saline-diluted allergens to avoid under- or over-injection. Each dog was then injected intradermally with 0.25 mL of 1:100 000 w/v histamine (Greer®) solution as the positive control,13,15 a negative control solution of 0.4% phenolated saline (ALK-Abelló) and 96 allergen dilutions using 1 mL syringes and nee-dles (i.e. 98 injections in total). New syringes preloaded with 0.25 mL of allergens were used for each dog.

Each skin test site was evaluated 15 min post-injection for evidence of a reaction. Reactions were evaluated and scored by the same investigator. Subjective scores used a scale of 0 (negative) to 4+ (maximum positive) based on wheal size, erythema and turgidity by comparison to the positive and negative controls.3,13 Allergen extract concentration values used to derive the model-based TCs by the statistical model were obtained from the highest concentration of an allergen used where ≤10% of dogs had a subjective IDT reaction of ≥2+ at 15 min.

The subjective IDT values were used to determine subjective TC ranges. A subjective TC range was defined as the interval between allergen dilutions where >10% of dogs had a subjective IDT reaction of ≥2+ at the lowest dilution of allergen extract and where ≤10% of dogs had a subjective IDT reaction of ≥2+ at 15 min to the strongest dilution. The subjective TC ranges were from dilutions used for the IDT in Group 2 dogs (see below). The subjective TCs are represented as ranges because not every dilution within the range was tested; therefore, the true TC falls between these values. An objective measurement of the vertical and horizontal diameter of each reaction also was performed at 15 min following injection using digital callipers.

Intradermal testing of dogs was performed in two groups: Group 1 (n = 22) and Group 2 (n = 13). The concentrations of allergens used in Group 1 were based on a pilot study that tested eight serial dilutions for each allergen in eight purpose-bred beagles and outbred hounds (pilot data not shown). Intradermal testing dilutions were adjusted for Group 2 when the percentage of dogs with significantly positive reactions (≥2+) to any allergen tested was ≥10% in Group 1. Both groups were tested with 96 allergen dilutions; 11 allergens used at four different concentrations from each manufacturer, and D. farinae tested using four additional w/v concentrations from each manufacturer. Due to expiration of five lots before completion of the study, all dogs in Group 2 had three allergens (D. farinae, English plantain and mixed ragweed) with different lot numbers than were used for IDT in Group 1, which were tested with the initial lots obtained at the start of the study.

Following IDT, a 1% hydrocortisone spray (MalAcetic® Ultra Spray Conditioner, Dechra; Overland Park, KS, USA) was applied to the test site and then an ice pack wrapped in a towel was applied for 10 min. Once testing was completed, sedation was reversed with atipame-zole hydrochloride (Antisedan®, Zoetis) at 5,000 μg/m2 intramuscularly in the epaxial muscles.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were performed to describe the protein quantification of each allergen extract lot. The concentration of each allergen extract was compared between manufacturers by evaluating the ratio of geometric means of μg/1,000 PNU and determining 95% confidence intervals for those ratios (based on Student’s t-tests for differences of the logged concentration (μg/mL) per 1,000 PNU value).

The TC was defined as the allergen dilution which resulted in a positive reaction (≥2+) on 10% of the dogs. Probit regression models were fitted separately to the allergens from each company, using generalized estimating equations to account for the repeated measures on each dog. Subjective data results from each group of dogs tested were used to fit each model, with separate dose–response curves estimated for each group. The TC was estimated from each model for each group using the equation [Φ1(0.1) –β0]/β1, where β0 and β1 are the intercept and slope coefficients from the logistic regression for the corresponding group, and Φ–1 is the inverse of the standard normal cumulative distribution function. Standard errors of the TCs were reported along with the estimate. The TCs derived from the statistical model are termed “model-based TCs”.

Concordance between a subjectively positive IDT reaction (≥2+) at 15 min with the objective measurement was determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves along with the corresponding area underneath the curve (AUC). The AUC, or concordance index (C-index), gives the probability that a randomly chosen dog with a subjective positive reaction will have a larger objective measurement than a randomly chosen dog with a subjective negative reaction.

All analyses were carried out using R v3.4.1 (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria, 2017) or SAS v9.4. (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Total protein quantification

Differences in the protein concentration of allergen extracts were observed within and between manufacturers despite equivalent PNU/mL labelling (Table S1). When evaluating extracts labelled as 40,000 PNU, the protein amount varied from as low as 210.5 μg/mL for American elm to 1,117.2 μg/mL for Timothy grass from ALK-Abelló; however, for Greer® allergens labelled as 40,000 PNU, protein concentrations ranged from 231.0 μg/mL for white oak to 864.3 μg/mL for black walnut. The largest difference in protein concentrations between the same allergen extract lots was for ALK-Abelló. ALK-Abelló American elm extracts had a 115% difference (210.5–452.1 μg/mL). Most extracts from ALK-Abello had small differences in protein concentrations between lots, as shown for Timothy grass with a 36% difference (820.5–1117.2 μg/mL), black walnut with a 30% difference (925.5–1201.4 μg/mL), box elder with a 22% difference (279.5–341.8 μg/mL) and ragweed mix with a 5% difference (581.8–613.4 μg/mL). White oak had the most consistent protein concentrations with only a 3% difference (341.0–349.8 μg/mL) between lots.

The largest protein quantification differences within Greer® allergen extracts of 40,000 PNU were with black walnut lots demonstrating a 35% difference (638.8– 864.3 μg/mL). Similar to ALK-Abelló allergen extracts, most Greer allergen extracts had comparable protein concentrations between lots as shown for English plantain with an 18% difference (368.4–434.9 μg/mL), ragweed mix with a 23% difference (639.9–789.8 μg/mL) and Timothy grass with a 5% difference (756.0–797.1 μg/mL). Box elder extract had nearly identical protein concentrations (373.1–373.7 μg/mL).

Between manufacturers, the protein concentration of the identical allergens designated to have 40,000 PNU also differed. The largest differences in protein lot concentrations were for American elm with a 144% difference (210.5–513.1 μg/mL). Johnson grass had a 99% difference (262.8–522.3 μg/mL) and black walnut had an 88% difference (638.8–1201.4 μg/mL), whereas white oak (231.0–349.8 μg/mL) and Timothy (756.0–1117.2 μg/mL) both had a c. 50% difference. Ragweed mix had a 36% difference (581.8–789.8 μg/mL). Box elder had a 34% difference (279.5–373.6 μg/mL). Lamb’s quarter had the smallest difference at 14% (402.1–459.2 μg/mL).

The ratio of μg/1,000 PNU for all allergen extracts ranged from 5.3 μg/1,000 PNU to 40.7 lg/1,000 PNU. When comparing ALK-Abelló extracts with at least two lots of the same allergen, the largest difference was detected in American elm with a 113% difference (5.3–11.3 μg/1,000 PNU). Within Greer® extracts, the largest difference in the ratio of μg/1,000 PNU between two lots was for black walnut extracts with a 41% difference (16.0–22.6 μg/1,000 PNU). Between manufacturers, the largest difference in μg/1,000 PNU ratio was identified in black walnut with an 88% difference (16.0–30.0 μg/1,000 PNU) (Table S1).

The geometric mean ratio of ALK-Abelló to Greer® μg/1,000 PNU for each allergen extract ranged from 0.6 to 1.4. Black walnut had the largest mean μg/1,000 PNU ratio difference with 1.4, whereas English plantain and Johnson grass had ratios close to one. All other allergen extracts fell between 0.6 and 1.2 (Table S1).

SDS-PAGE analyses

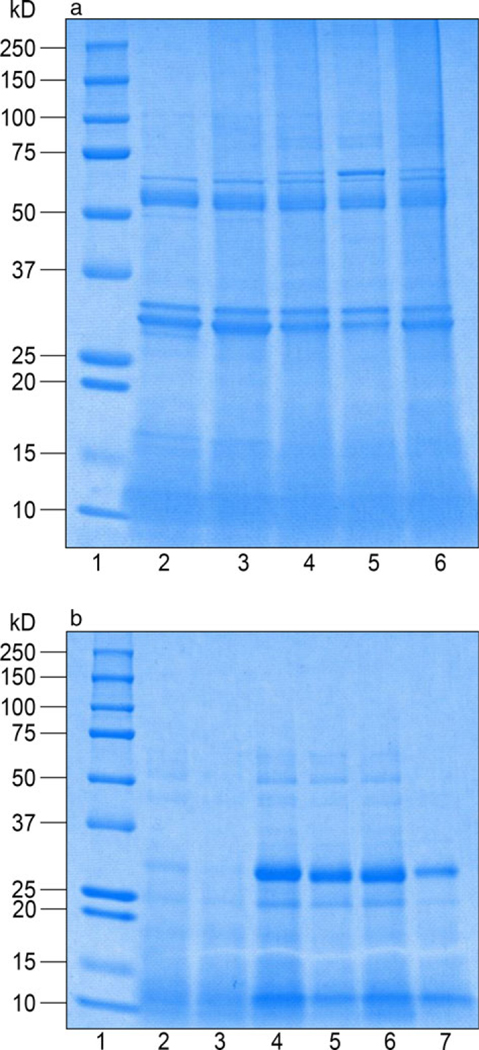

The qualitative protein composition of all 11 extracts was compared by SDS-PAGE and subsequent Coomassie staining. Phleum pretense (Timothy grass) extracts (Figure 1a) from both manufacturers had a comparable intensity in protein bands between ~31 and 34 kDa; however, the Greer extract in lane 2 had an additional small band of ~30 kDa that was not present in the other extracts. Heterogeneity of protein bands between ALK-Abello and Greer® extracts was identified ~50–70 kDa (Figure 1a). Greer® extracts (lanes 2–3) had lower molecular weight bands at 50 kDa that were absent in ALK-Abello extracts (lanes 4–6). However, there was an additional band in the ALK-Abello extracts between 50 and 70 kDa that were absent in the Greer® extracts. Despite loading equal amounts of protein by PNU, differences in intensity of bands can be seen between extracts from the same company, as demonstrated by the bands at ~68 kDa of lanes 2, 3, 5 and 6.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis (a) Phleum pretense (Timothy grass) and (b) Sorghum halepense (Johnson grass). Protein concentration of Phleum pretense extracts were 10,000 PNU per lane and the protein content of Sorghum halepense extracts were evaluated at 20,000 PNU per lane. (a) Lanes: (1) Ladder; (2) Greer® Timothy grass Lot #278062; (3) Greer® Timothy grass Lot #288475; (4) ALK-Abelló Timothy grass mix; (5) ALK-Abelló Timothy grass Lot #1701311; (6) Timothy grass Lot #1817751. (b) Lanes: (1) Ladder; (2) Greer Johnson grass, Lot #277588; (3) Greer Johnson grass, Lot #287540; (4) ALK-Abelló Johnson grass mix; (5) ALK-Abelló Johnson Lot #1475181; (6) ALK-Abelló Johnson Lot #1815590; (7) ALK-Abelló Johnson Lot #1512897. Mixed allergens were composed of at least two allergen extracts of different lots from the respective manufacturer.

Overall, the bands for Sorghum halepense (Johnson grass) extracts (Figure 1b) from ALK-Abelló (lanes 4 –7) were stronger in intensity compared to those from Greer® (lanes 2–3). Notably, protein bands at ~30 kDa were nearly absent to faint in the Greer® extracts (lanes 2–3), whereas they were prominent in ALK-Abello extracts (lanes 4–6), but less robust in the ALK extract shown in lane 7. Likewise, ALK-Abello extracts in lanes 4–6 had a band at 50 kDa, but this was absent in Greer® extracts (lanes 2–3) and the ALK-Abelló extract in lane 7.

The extracts with the most similar protein compositions between manufacturers were lamb’s quarter, ragweed mix and white oak (Figures S1f, g and i, respectively). The protein electrophoresis of the extracts American elm, black walnut, box elder, D. farinae, English plantain and red cedar showed heterogeneity in intensities for specific protein components within and between manufacturers (Figures S1a–e and h). The heterogeneity in protein extract components is highlighted by D. farinae extracts (Figure S1d). Distinct bands at ~14–15 kDa were noted for ALK-Abelló extracts (lanes 3 –5), but not in the Greer extract (lane 2). Proteins of 14 kDa correspond with the Group 2 allergen, MD-2-related protein. All D. farinae extracts show a range of very faint to strong protein bands between 150 and 250 kDa, a range of molecular weights where the allergen Zen-1 would be expected.

Animals

The privately owned dogs included 13 neutered males and 12 spayed females. Their ages ranged from 2 to 10 years of age (mean age 5.8 years). Breeds included American pit bull terrier (1), collie (1), German shepherd dog (3), German shorthair pointer (1), golden retriever (2), greyhound (3), mixed breed (5), pit bull mix (7), presa Canario (1) and standard poodle (1). Complete blood counts and biochemical profiles performed at study inclusion had no significant abnormalities. The purpose-bred beagles included six intact males and four intact females with an age range of 1–3 years old (mean age 1.5 years). Group 1 included 22 client-owned dogs; Group 2 contained three client-owned dogs and 10 purpose-bred beagles. No further dogs were enrolled in Group 2, due to expiration of allergen extracts. At the time of enrolment and IDT, all dogs were systemically healthy with no cutaneous or mucosal abnormalities.

Allergen extract threshold concentrations

Allergen extract dilutions used in Group 2 dogs were established after dilutions used for the IDT in Group 1 dogs produced subjective reactions for allergens that were ≥10% of the cut-off for TC. The allergen extract dilutions used for Group 2 dogs provided the greater number of evaluable TCs compared to the dilutions used in Group 1 dogs (Table S2). Using the TC cut-off of ≤10% positivity for the Group 2 dogs, the generalized estimating equations produced model-based TCs for nine PNU/mL allergen extracts from ALK-Abelló and eight PNU/mL allergen extracts from Greer (Table 1, Figure S2). The model-based TCs ranged from 24 to 3,930 PNU/mL for ALK-Abello allergens and from 177 to 1,760 PNU/mL for Greer allergens. The standard error for the model-based TCs for ALK-Abello allergens ranged from 8.72 PNU/mL for D. farinae (24 ± 8.72 PNU/mL) to 33,000 PNU/mL for white oak (3,930 ± 33,300 PNU/mL). The standard error for the model-based TCs for Greer® allergens ranged from 66.4 PNU/mL for Timothy grass (177 ± 66.4 PNU/mL) to 9,450 PNU/mL for ragweed mix (1,760 ± 9,450 PNU/mL). Model-based TCs could not be determined for the ALK-Abelló allergens of ragweed mix and English plantain, and for the Greer allergens of red cedar, white oak and D. farinae. When evaluating D. farinae extract as w/v concentrations, the model-based TCs could not be determined for either manufacturer.

Table 1.

Comparison of statistically derived and ranges of subjective allergen extract threshold concentrations from two manufacturers

| Allergen threshold concentrations |

||

|---|---|---|

| Statistical model (PNU/mL SE) |

Subjective ranges (PNU/mL) |

|

| ALK-Abelló | ||

| American elm | 786 (836) | 625–1,250 |

| Black walnut | 890 (450) | 750–1,000 |

| Box elder | 576 (108) | 300–600 |

| Dermatophagoides farinae | 24 (8.72) | 20–30 |

| English plantain | † | >6,000 |

| Johnson grass | 92 (19.2) | 50–100 |

| Lamb’s quarter | 1,420 (286) | 1,000–2,000 |

| Ragweed, mixed | † | 100–200 |

| Red cedar | 613 (321) | 750–1,000 |

| Timothy grass | 146 | 150–300 |

| White oak | 3,930 (33,300) | >1,000 |

| Greer | ||

| American elm | 216 (400) | <100 |

| Black walnut | 605 (2310) | >600 |

| Box elder | 583 (3,380) | >600 |

| Dermatophagoides farinae | † | <5 |

| English plantain | 303 (269) | <50 |

| Johnson grass | 220 (427) | 25–50 |

| Lamb’s quarter | 846 (244) | 250–500 |

| Ragweed, mixed | 1,760 (9,450) | >1,750 |

| Red cedar | † | <187.5 |

| Timothy grass | 177 (66.4) | <62.5 |

| White oak | † | 100–200 |

SE standard error.

Not determined as fitted values from the estimating equations did not reach the 10% response threshold.

Subjective TC ranges were determined for nine PNU/mL allergen extracts from ALK-Abelló and three allergen extracts from Greer. All subjective TC ranges determined for ALK-Abelló and Greer® allergen extracts encompassed the statistically derived model-based TCs, except for the allergens where a model-based TC concentration was not determined, and for Timothy grass for both manufacturers (Table 1). The model-based TC for Timothy grass from ALK-Abelló was 146 PNU/mL, which differed slightly from the subjective TC range of 150–300. Likewise, for Timothy grass from ALK-Abelló, the model-based TC was 177 ± 66.4 PNU/mL which differed from the subjective TC of <62.5 PNU/mL. The ALK-Abelló model-based TC could not be determined for the English plantain and ragweed mix extracts; however, the subjective TC ranges were >6,000 PNU/mL and 100–200 PNU/mL, respectively. For the Greer® allergen extracts of D. farinae, red cedar and white oak, the model-based TCs were not found; however, the subjective TC ranges were <5 PNU/mL, <187.5 PNU/mL and 100–200 PNU/mL, respectively.

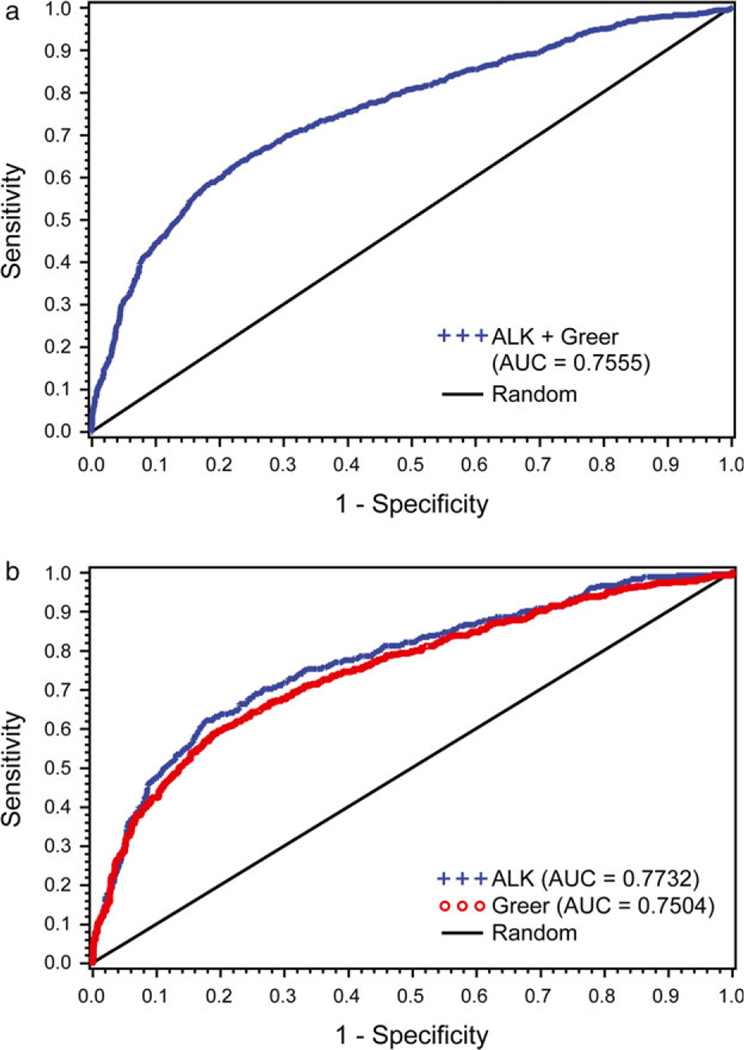

Comparison of subjective and objective IDT measurements

This comparison was carried out by producing ROC curves to evaluate the concordance of a subjectively positive IDT reaction (≥2+) at 15 min with the objective measurement. The AUC, a measure of test accuracy, was 0.7555 when the data from both companies were combined (Figure 2a). A percentage concordance of 75.5% was interpreted to mean that a randomly selected dog, that had a subjective positive reaction, had a larger objective measurement than that of a randomly chosen dog from the negative group 75.5% of the time. When the data from both companies were analysed separately, the percentage concordance was 77.3% for ALK-Abelló and 75% for Greer (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Receiver operating curves (ROC) for percentage concordance of intradermal test subjectively positive reactions (≥2+) and objective measurements (mm). (a) The area under the curve (AUC) when combining results from both manufacturers. (b) The AUCs for ALK-Abelló (blue) and for Greer (red). The black diagonal line (random) extending from coordinates 0,0 to 1,1 represents the benchmark for matching a subjective result with a larger objective measurement based on random chance alone.

Discussion

Repeatable and clinically interpretable IDT results are accomplished by using allergen extracts with consistent protein concentrations at appropriate testing concentrations. In this study, differences in protein concentration of allergen extracts manufactured by two different veterinary allergen suppliers were identified despite the label having the same PNU/mL values. If protein concentrations are truly higher or lower than the purported extract value, this may undermine the results of IDT through the creation of false negative and positive test reactions.

Traditional expression of allergen extract potency has been measured by PNU or w/v. Each measure differently assesses the potency of an extract. Protein nitrogen values are measures of protein nitrogen in the extract that is converted to units to give a PNU, whereas the ratio of w/v reflects the grams of the source material to volume of extraction solution.13 As shown in the current study, PNU and w/v measurements do not directly assess the total protein concentration of an extract, which may be related to extract production. Extract production is a complex multistep process with minimal standardization. Extracts manufactured by a single supplier vary from lotto-lot, due to the nature of the source material being utilized and uncontrollable circumstances influencing natural products. We observed mild variability in protein composition between the same pollen and mite extracts made by the two manufacturers. However, given the small number of analysed allergen lots, the identified variability in protein complexity may or may not make a difference in extract performance based on the inclusion or exclusion of immunodominant allergens. The translation of these differences into clinical outcomes of skin test reactivity expected from an IDT and clinical response to ASIT is unknown in veterinary medicine. European standards for human allergen production allow the total protein content of standardized allergens to range from 50% to 150% of the stated amount to account for variability in the source materials.23 Similar variation in standardized extracts is allowed in the United States, because the range of the major allergen Fel d 1 content in cat extracts can contain 10–19.9 U/mL.24

We used SDS-PAGE to survey the qualitative protein composition of the commercial allergen extracts. Protein heterogeneity was evident between and within different lots of the same allergen for both manufacturers. This finding was not unexpected considering the variation in source material, manufacturing process and potency measures. The importance of this variation on diagnosis, monitoring for therapy and treatment remains undetermined. Heterogeneity in protein content was evident in D. farinae extracts. All D. farinae extracts in this study demonstrated a band between 150 and 250 kDa that falls within the size range inclusive of Zen-1 and may represent this protein. Zen-1, an 188 kDa protein, has been suggested as a major allergen in atopic dogs sensitized to D. farinae.25 A protein of 14 kDa is recognized as a major allergen of D. farinae in humans and dogs and is termed Der f 2 MD-2 related protein. A band on the SDS-PAGE gel of this size was absent in the Greer extract lot used for the electrophoresis analysis, yet was present in the ALK-Abelló extract lots.26 Finally, the third identified canine major allergen for D. farinae is 60 kDa, Der f 18.27 A band of this size was absent on the SDS-PAGE gel in the lanes with the ALK-Abelló extracts; it was present in the Greer extract. By using extracts that lack a major allergen, false-negative results may occur during IDT. Conclusive evidence for the absence of Der f 2 and Der f 18 is made by directly measuring these proteins in the extracts by Western blot analysis or by excising the band from the gel and performing mass spectrometry analysis, which was beyond the scope of this study.

Model-based TCs and ranges of subjective TCs for allergen extracts were reported. Threshold concentrations based on the subjective results of serial allergen dilutions provide a range of where the actual TC would occur as an infinite number of concentrations fall within the interval. Certainly, in other studies evaluating TCs in clinically normal dogs, subjective TCs could not be determined or were much higher than what was found in this study.16,28,29 In the only study evaluating TCs in extracts manufactured by ALK-Abelló, subjective TCs could not be determined for lamb’s quarter or Timothy grass, they were reported to be <6,000 PNU/mL.17 In lieu of performing thousands of serial extract dilutions, probit regression models using a generalized estimating equation were used to determine model-based TCs. A statistical model also was used to determine equine IDT TCs of house dust mites and storage mites.30 The results of the model-based TCs match the respective allergen extract subjective ranges with the exception of Timothy grass from both manufacturers.

When not considering the standard errors, the model-based TCs varied between manufacturers. There was a 264% difference in the model-based TC of American elm between manufacturers. American elm extracts have a model-based TC of 786 PNU/mL for the ALK-Abelló compared to 216 PNU/mL for the Greer®. This result may correspond to the lower protein concentration of the ALK-Abelló extract and the absence of bands at approximately 50 kDa in one ALK-Abello American elm extract lot. The model-based TCs of Johnson grass also differed by 139% between manufacturers. Although the average ALK-Abelló to Greer® μg/1,000 PNU ratio for Johnson grass was equivalent, variation in protein banding patterns between manufactures was demonstrated in the SDS-PAGE gels. Analysis of the ALK-Abello Johnson grass extracts showed an increased number of bands at 50 kDa and overall stronger band intensity compared to the Greer extracts, which may relate to the lower model-based TC of 92 PNU/mL for ALK-Abelló compared to the higher model-based TC of 220 PNU/mL for Greer. Finally, the model-based TCs for D. farinae w/v extracts could not be determined, but the model-based TC was found for PNU/mL extract by ALK-Abelló. This suggests that the w/v model-based TCs for mites are much different from the PNU model-based TCs in normal dogs. A study in dogs evaluating subjective IDT reactions using aqueous allergens from multiple manufacturers reported significant agreement and correlation in positive test results to four mite allergens in normal dogs when comparing allergen batches from different suppliers when measured at concentration of 250 PNU/mL.16

Similar to allergen extracts, there is no standard method of scoring IDT. Both objective measurements and subjective scoring (0 to 4+) are used in grading IDT. A subjective score is based on the perceived size, erythema and turgidity of the wheal.3 A previous study revealed poor interobserver agreement of subjective scoring alone.17 Combining subjective and objective measurements theoretically should lessen variability of IDT grading. Using ROC analyses, we observed at least a 75% agreement between a positive subjective reaction and objective measurement in normal dogs. Our results paralleled the findings in a study which found a moderate level of correlation between the subjective and objective scores in atopic dogs.31 When considering the results of our ROC curves in normal dogs and the previous study in atopic dogs, these would imply that combining subjective and objective scores and equally weighting size, erythema and turgidity, that the incidence of perceived false-positive and false-negative results may be reduced.

One limitation of this study is that the sample size contributed to the high standard errors of the calculated TCs. The standard error depends on the standard deviation, a measure of variability, of the values obtained and the sample size.32 With a larger sample size, the standard error could have been reduced as the chance of variation is minimized. The different total protein concentrations and heterogeneity of allergen extracts could have contributed to the larger standard errors as well. Intradermal test TCs were evaluated using two populations of dogs. Privately owned dogs were considered nonatopic based on the pre-enrolment owner questionnaire, physical and dermatological examination findings and complete bloodwork. Purpose-bred beagles were deemed nonatopic based on their medical history, physical examination and origin of derivation from well-characterized purpose-bred breeding stock. Although all client-owned dogs were greater than 2 years of age, it is impossible to ensure that none of the enrolled dogs would exhibit allergic signs in the future. The ideal study would evaluate TCs in purpose-bred specific pathogen-free dogs. However, potentially, by combining both populations of animals, as we did in our study, a more accurate evaluation of TC has been accomplished.

Other limitations were associated with the recruitment length, the eight week controlled diet enrolment criteria and allergen lot expiration. Five allergen lots expired between the time the IDTs were performed in Group 1 and the time they were performed in Group 2. As we found differences in protein concentration and composition between lots of the allergen extracts from the same manufacturer, this may have been reflected in the IDT results for Group 2 and the overall TCs. Allergen extracts possess different proteolytic activity, which can lead to heightened or decreased degradation, ultimately affecting IDT reactivity over time. A final limitation is that PNU/mL was used as the predominant unit of measure for the IDT concentrations. The amount of PNU per allergen is influenced by the extraction procedure and evaluation of PNU content in each extract varies according to the method of measurement. Therefore, using only allergens with standardized reference standards would be ideal for use in determining TCs. However, because PNU and w/v labelled nonstandardized extracts are used in clinical practice, this study applies to a practical setting.

In conclusion, both differences in protein concentration and composition were identified between lots of allergen extracts and by manufacturer. Model-based threshold concentrations for allergens from two allergen manufacturers vary, suggesting that careful consideration in determining the appropriate intradermal testing allergen dilution concentrations is warranted. We recognize that basing TCs purely on results from clinically normal outbred and purpose-bred dogs poses an inherent risk of miscalculating the “irritant” TCs in a hypersensitive patient, as these may deviate from the TCs identified in normal animals. Therefore, studies in atopic dogs with defined hypersensitivities to the allergens used in this study would identify the allergy detection TCs. This concept would be similar to the “IntraDermal dilution for 50 mm sum of Erythema determines the bioequivalent ALlegry units” (ID50EAL) testing method used to designate a bioequivalent allergy unit (BAU/mL) of biological potency of an allergen.8 Veterinary clinical practice may benefit from future studies that determine if these qualities affect IDT results and subsequent response to ASIT.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. (a–i) SDS-PAGE analysis of allergen extracts.

Figure S2. (a–d) Plots of fitted lines based on generalized estimating equations for each group of dogs based on probit models.

Table S1. Comparison of total protein concentrations of allergen extract lots from ALK-Abello and Greer.

Table S2. Intradermal test (IDT) allergen extract concentrations.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful and indebted to the owners and their pets for participating in the study. We would like to thank ALK-Abelló for collaboration, scientific input, allergens and supplies, as well as Blue Buffalo Company for providing the client-owned dog’s diet and treats. Finally, we would like to thank Marc Hardman and Tim Vojt for the figures.

Source of Funding: This study was funded by ALK-Abello; this included purchase of Greer allergen extracts and intradermal testing materials; ALK-Abello allergens were supplied free of charge.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Conflict of interests: Michelle L. Bolner, Tricia Moore-Sowers and Greg A. Plunkett are employees of ALK-Abello, they were involved in study design and drafting of the manuscript; the other authors do not declare any conflict of interests.

References

- 1.DeBoer DJ, Hillier A. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (XV): fundamental concepts in clinical diagnosis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2001; 81: 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeBoer DJ, Hillier A. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (XVI): laboratory evaluation of dogs with atopic dermatitis with serum-based “allergy” tests. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2001; 81: 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillier A, DeBoer DJ. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (XVII): intradermal testing. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2001; 81: 289–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alessandri C, Ferrara R, Bernardi ML et al. Diagnosing allergicsensitizations in the third millennium: why clinicians should know allergen molecule structures. Clin Transl Allergy 2017; 7: 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aalberse RC, Aalberse JA. Molecular allergen-specific IgE assays as a complement to allergen extract-based sensitization assessment. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015; 3: 863–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loewenstein C, Mueller RS. A review of allergen-specific immunotherapy in human and veterinary medicine. Vet Dermatol 2009; 20: 84–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiric J, Reuter A, Rabin RL. Mass spectrometry to complementstandardization of house dust mite and other complex allergenic extracts. Clin Exp Allergy 2017; 47: 604–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow KS, Slater JE. Regulatory aspects of allergen vaccinesin the US. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2001; 21: 141–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baer H, Maloney CJ, Norman PS et al. The potency and Group Iantigen content of six commercially prepared grass pollen extracts. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1974; 54: 157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vailes L, Sridhara S, Cromwell O et al. Quantitation of the majorfungal allergens, Alt a 1 and Asp f 1, in commercial allergenic products. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 107: 641–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Focke M, Marth K, Valenta R. Molecular composition and biological activity of commercial birch pollen allergen extracts. Eur J Clin Invest 2009; 39: 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willemse A, van den Brom WE. Evaluation of the intradermalallergy test in normal dogs. Res Vet Sci 1982; 32: 57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reedy LM, Miller WH, Willemse T. Allergic Skin Diseases of Dogs and Cats. 2nd edition. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1997; 50–113. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wellington J, Miller WH, Scarlett JM. Determination of skinthreshold concentration of an aqueous house dust mite allergen in normal dogs. Cornell Vet 1991; 81: 37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller WH Jr, Griffin CE, Campbell KL. Muller & Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, 7th Edition. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier Mosby, 2013; 559. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koebrich S, Nett-Mettler C, Wilhelm S et al. Intradermal andserological testing for mites in healthy beagle dogs. Vet Dermatol 2012; 23: 192–e139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foust-Wheatcraft DA, Dell DL, Rosenkrantz WS et al. Comparison of the intradermal irritant threshold concentrations of nine allergens from two different manufacturers in clinically nonallergic dogs in the USA. Vet Dermatol 2017; 285: 564–e136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coomassie Plus (Bradford) Assay Kit Instructions. Rockford, IL: ThermoFisher Scientific, 2016; 8. Available at: https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/MAN0011203_CoomassiePlus_Bradford_Asy_UG.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frew AJ, Powell RJ, Corrigan CJ et al. Efficacy and safety ofspecific immunotherapy with SQ allergen extract in treatmentresistant seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 117: 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffin CE, Hillier A. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (XXIV): allergen-specific immunotherapy. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2001; 81: 363–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casset A, Mari A, Purohit A et al. Varying allergen compositionand content affects the in vivo allergenic activity of commercial Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extracts. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2012; 159: 253–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hauck PR, Williamson S. The manufacture of allergenic extracts in North America. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2001; 21: 93–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonertz A, Roberts G, Slater JE et al. Allergen manufacturingand quality aspects for allergen immunotherapy in Europe and the United States: an analysis from the EAACI AIT Guidelines Project. Allergy 2017; 73: 816–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slater JE. Standardized allergen extracts in the United States. In: Lockey RF, Buckantz SC, Bousquet J eds. Allergens and Allergen Immunotherapy, 3rd edition: New York: CRC Press, 2004; 421–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olivry T, Dunston SM, Favrot C et al. The novel high molecularweight Dermatophagoides farinae protein Zen-1 is a major allergen in North American and European mite allergic dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol 2017; 28: 177–e138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moya R, Carnes J, Sinovas N et al. Immunoproteomic characterization of a Dermatophagoides farinae extract used in the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2016; 180: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber E, Hunter S, Stedman K et al. Identification, characterization, and cloning of a complementary DNA encoding a 60-kd house dust mite allergen (Der f 18) for human beings and dogs. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 112: 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hensel P, Austel M, Medleau L et al. Determination of thresholdconcentrations of allergens and evaluation of two different histamine concentrations in canine intradermal testing. Vet Dermatol 2004; 15: 304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bauer CL, Hensel P, Austel M et al. Determination of irritantthreshold concentrations to weeds, trees and grasses through serial dilutions in intradermal testing on healthy clinically nonallergic dogs. Vet Dermatol 2010; 21: 192–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts HA, Hurcombe SD, Hillier A et al. Equine intradermaltest threshold concentrations for house dust mite and storage mite allergens and identification of stable acari fauna. Vet Dermatol 2014; 25: 124–134, e35–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hubbard TL, White PD. Comparison of subjective and objectiveintradermal allergy test scoring methods in dogs with atopic dermatitis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2011; 47: 399–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altman DG, Bland JM. Standard deviations and standard errors. BMJ 2005; 331: 903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. (a–i) SDS-PAGE analysis of allergen extracts.

Figure S2. (a–d) Plots of fitted lines based on generalized estimating equations for each group of dogs based on probit models.

Table S1. Comparison of total protein concentrations of allergen extract lots from ALK-Abello and Greer.

Table S2. Intradermal test (IDT) allergen extract concentrations.