Abstract

Purpose of Review

Addiction and excessive substance use contribute to poor mental and physical health. Much research focuses tightly on neural underpinnings and centrally-acting interventions. To broaden this perspective, this review focuses on bidirectional pathways between the brain and cardiovascular system that are well-documented and provide innovative, malleable targets to bolster recovery and alter substance use behaviors.

Recent Findings

Cardiovascular signals are integrated via afferent pathways in networks of distributed brain regions that contribute to cognition, as well as emotion and behavior regulation, and are key antecedents and drivers of substance use behaviors. Heart rate variability (HRV), a biomarker of efficient neurocardiac regulatory control, is diminished by heavy substance use and substance use disorders. Promising evidence-based adjunctive interventions that enhance neurocardiac regulation include HRV biofeedback, resonance paced breathing, and some addiction medications.

Summary

Cardiovascular communication with the brain through bidirectional pathways contributes to cognitive and emotional processing but is rarely discussed in addiction treatment. New evidence supports cardiovascular-focused adjunctive interventions for problematic substance use and addiction.

Keywords: addiction, substance use, holistic, evidence-based interventions, heart rate variability

Introduction

Substance use is a widely-recognized contributor to the global burden of disease, with alcohol and other drug use linked to many of today’s most common psychological and physical health problems, including anxiety and depression, cardiovascular disease, liver disease, and cancers [1]. Most research and clinical practices related to substance use focus on substance use disorders (SUD). While this focus is of clear importance, a more expansive view is emerging that considers how substance use can broadly reduce health and increase risk for disease, disorder, and illness, even in the absence of ‗addiction’ per se. This new framework suggests that frontline healthcare providers can play a pivotal role in assessing substance use behaviors. This article further suggests that such providers can intervene in problematic substance use using body-based strategies that are both simple to learn and simple to teach. This article proposes that body-based interventions allow the health risks of substance use to be perceived as analogous in many ways to those from sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, and insufficient sleep. In doing so, they may also serve to reduce the stigma associated with substance misuse.

This article focuses on neuroscience-informed, body-based intervention strategies that are gaining popularity and research support. Specifically, we emphasize the role of the cardiovascular system in subjective experiences and learned behaviors, which include substance use and addiction. We then present heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback and resonance paced breathing as body-focused interventions that harness inherent regulators of body-brain communication to instigate neuroplasticity [2, 3]. These interventions have been shown both to improve physiological health and to support emotion regulation and cognitive control [4, 5]. Finally, we align the use of body-focused interventions to current pharmacotherapies and conclude with an overview of how a body-focused approach to substance use and addiction expands our view of health, disease, and recovery, while simultaneously adding precision and personalization.

The case for considering the body in substance use and addiction

Anyone who has experienced the racing heart of fear, the broken heart of loss, or the fluttering heart of love knows that body states are an intrinsic component of subjective experience. Rapid advances in the field of interoception add an empirical base to these human experiences [6, 7]. Moreover, interoception provides a mechanism to explain how body states play a critical role in learned behavior. Namely, body states provide sensory and visceral context to neural processes. This sensory and visceral context is increasingly being recognized as a powerful factor in drug-seeking behavior [8] and addictive disorders [9, 5].

In the case of the cardiovascular system, while changes in heart rate and blood pressure serve as essential and broadly utilized health biomarkers, more recent research has also demonstrated that these changes become embedded features of cognitive-emotional experience [5, 4]. This has significant implications for how we view cardiovascular system processing; it is not simply a passive, static indicator of life, but an active, dynamic contributor to it. This perspective aligns with research across a range of physiological systems, most notably the immune and digestive systems that interact with the autonomic nervous system and brain to support cognitive and emotional regulation [10, 11].

Anatomically, the cardiovascular system and its bidirectional connections to the brain have been well-elaborated [12]. Only more recently, however, has research moved the conceptualization of cardiovascular physiology beyond reflexive blood pressure control [13–15]. Cardiovascular information enters the brain at the nucleus tractus solitarius in the brainstem, which is then propagated to structures that control heart rate and peripheral resistance (i.e., vasculature tone and blood pressure), as well as to structures linked to cognition and emotion, namely the medial prefrontal cortex, insula, basolateral amygdala, thalamus, hypothalamus, and ventral tegmental area. This adds further support for how bodily signals become an embedded component of learned behaviors. The high degree of overlap between these structures and those delineated in prominent addiction theories is noteworthy [5].

The cardiovascular system has several advantages over other body systems as an intervention target to improve both physical and mental health. Most notably, it is easy to monitor and easy to manipulate. Additionally, there are established normative cardiovascular parameters (e.g., resting average blood pressure of 120/80) that are widely used as medical biomarkers. Beyond these static biomarkers, dynamic indices, such as heart rate variability (HRV), are gaining prominence in clinical science [16], in part because of the increasing availability of low-cost, ambulatory HRV monitoring tools like wearable electrocardiographs and photoplethysmographs, and smartphone apps. Acceptability of HRV monitors is further bolstered by general knowledge that HRV is associated with, and predicts, variations in fitness and health. Psychologically and physiologically healthy individuals typically present with relatively higher levels of HRV, while those with underlying health conditions, including SUD, commonly show relatively lower HRV levels [17, 18] (see Heiss et al., 2021 for an exception). HRV can be measured at rest or in response to a wide variety of challenges and, in 5 minutes or less, multiple measures of HRV can be obtained. Multiple HRV measures directly reflect inherent physiological control mechanisms, most notably vagal (e.g., parasympathetic activation) and baroreflex control mechanisms [19, 13, 20].

Research in our laboratories focuses on the baroreflex control mechanism. This mechanism is well known because it ensures reflexive control of blood pressure through closed-loop feedback systems that modulate heart rate, stroke volume, and vascular tone [19, 13, 21, 22]. The heart rate baroreflex is particularly well understood; heart rate accelerations and/or vasoconstriction lead to an increase in blood pressure that is detected by baroreceptors present in arterial walls; this information is conveyed to the brain that then signals heart rate deceleration via efferent parasympathetic signaling. As noted above, the afferent heart rate and blood pressure information is also conveyed to higher-order subcortical and cortical structures that embed this information within a cognitive-emotional context and communicate with midbrain and brainstem structures to influence subsequent cardiovascular adjustments. In this way, cardiovascular and other bodily feedback becomes integrated within conscious elements of executive control and emotion regulation, as well as in attention bias, salience, and craving processes that operate largely outside of awareness [23, 10].

Changing cardiovascular physiology leads to clinical benefit

HRV biofeedback and resonance paced breathing are two closely related bio-behavioral interventions that engage autonomic regulatory processes through slow, paced breathing. Both interventions evoke strong neuroplastic responses [24, 25] and produce positive clinical changes across multiple physical and mental health disorders including hypertension, asthma, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and SUD [25, 26]. Both HRV biofeedback and resonance paced breathing are techniques that manipulate respiratory sinus arrhythmia, a physiological phenomenon that links respiratory and cardiovascular functioning [27]. When the respiratory sinus arrhythmia is entrained to the inherent internal rhythm of the baroreflex, an exponential whole-system cardiovascular response is observed. In HRV biofeedback, an individual’s resonance frequency (i.e., the frequency at which minimal respiratory input elicits maximal cardiovascular response) is precisely identified, and then breathing at this frequency is guided by biofeedback equipment (i.e., where one’s dynamic pulse wave is displayed on a screen to guide breathing frequency). For most individuals, the resonance frequency is ~0.1Hz, which is equivalent to 6 breaths per minute, though there is some inter-individual variability based on body size and blood volume [28, 27]. Resonance paced breathing is based on the same physiological principles but instead of utilizing individualizing biofeedback, breathing is simply paced at 0.1Hz using a digital app or clock.

Most research to date has focused on multi-week courses of HRV biofeedback and demonstrated that breathing at one’s precise resonance frequency confers the greatest physiological and psychological benefits [29, 30]. Yet, evidence is growing that even brief episodes of resonance paced breathing similarly support cardiovascular health, autonomic homeostasis, cognitive and emotional self-regulation, and may reduce autonomic allostatic load during stress states [25, 31]. Meta analytic evidence supports the use of HRV biofeedback and resonance paced breathing across a wide range of disorders [25]. Medium-to-large effect size decreases in anxiety and stress have been observed in response to HRV biofeedback and resonance paced breathing [25, 31], consistent with positive modulatory effects on brain regions dually involved in autonomic nervous system control [32] and addiction [33, 5]. A substantial body of work indicates HRV biofeedback benefits individuals with difficulty regulating affect such as depressive disorders [e.g., 34, 35–37] and PTSD [e.g., 38, 39–42], both of which are highly co-morbid with SUD. Such interventions need not be seen as stand-alone measures; rather, interventions that enhance baroreflex sensitivity may facilitate cognitive, behavioral, and motivational therapies for SUD.

Early successes with HRV biofeedback and resonance paced breathing for disorders that involve emotion dysregulation gave rise to a growing body of work exploring the potential benefits of HRV biofeedback for SUD. It was posited that HRV biofeedback could enhance communication between neural and cardiovascular systems that modulate physiological arousal in response to internal and external cues that are antecedent to substance use, thus increasing behavioral flexibility and reducing relapse risk [43, 4]. A recent systematic review [44] suggests that HRV biofeedback may reduce craving, citing work involving short [3 sessions; 45], moderate [6 sessions; 46, 47], and longer term [8 sessions; 48, 49] interventions. Studies by Penzlin and colleagues also showed HRV biofeedback led to reductions in anxiety in patients with alcohol use disorder [47], and a trend towards lower alcohol use relapse at one-year follow-up compared to controls [46].

Brief (e.g., 5 minutes) assessment of neurocardiac processes may have utility predicting who will show positive clinical benefit from biobehavioral interventions such as HRV biofeedback. For example, higher resting HRV was associated with lower craving in alcohol dependent outpatients [50]. Further, in a clinical trial of HRV biofeedback for SUD, lower resting baseline HRV was associated with increases in craving over three weeks in an inpatient SUD group who received treatment as usual (TAU) [45]. However, this effect was not present in the group that received HRV biofeedback in addition to TAU. Thus, the intervention appeared to dissociate the relationship between initial physiological vulnerability and craving changes during treatment. These findings suggest that HRV biofeedback may be an especially useful adjunctive treatment for those showing evidence of weaker autonomic regulation (i.e., lower HRV), although further study is needed to support this hypothesis.

The benefits of HRV biofeedback are not limited to those with mental and physical health conditions. Evidence has shown that in the wider population, practicing resonance breathing, in some cases only for 5 or 10 minutes, can improve cognitive performance [51], decrease performance anxiety [52], reduce stress, and improve sleep quality [53, 54]. This suggests that resonance breathing not only confers benefit in persons with disorders, but more broadly it enhances baroreflex signaling and the integration of cardiovascular signals with neural processes responsible for cognitive and emotional regulation for all people. The scope of potential application of this intervention thus extends across the continuum of preclinical, high-risk, substance use disordered, and recovering populations.

Such applications are supported by recent technological advances that have given rise to small, light-weight, wearable biosensors and smartphone applications that use photoplethysmography to enable wearers to engage in HRV biofeedback on-the-go [55–57]. Additionally, some second-generation ambulatory, biosensor-based technologies that monitor autonomic arousal in real time can be used to prompt wearers to engage in brief bursts of HRV biofeedback to normalize autonomic output during periods of stress/high autonomic arousal [58]. These just-in-time interventions may serve as useful tools to buffer salient contextual triggers and urges to use alcohol and other drugs, as well as anxiety and stress. We recently observed, for example, that a single 5-minute session of resonance paced breathing decreased neural activation to alcohol cues in visual representation and attentional processing brain regions, while at the same time increasing activation in regions associated with behavioral control, internally directed cognition, and brain-body integration across low risk drinkers and those who met criteria for alcohol use disorder [24]. In addition to their potential for direct clinical benefit, the advent of ambulatory HRV biofeedback and paced breathing devices has profound implications for the accessibility and scalability of HRV biofeedback and resonance paced breathing because they are affordable, usually integrate with the end-user’s smartphone, and do not require a provider to administer the intervention. These characteristics make implementation through mobile technologies especially useful for underserved and hard-to-reach populations.

Support for body-focused intervention from pharmacotherapy

A number of on- and off-label medications are commonly used in the treatment of SUD. Though generally speaking these medications are thought to confer benefit by mitigating withdrawal symptoms and/or reducing craving, the specific mechanism of action for most SUD medications is not known [59, 60]. Some of these medications have well documented, direct cardiovascular effects, while others have likely or implied effects on cardiac modulation. It is possible that several of these medications may help support SUD recovery indirectly through normalization of neurocardiac processes.

For instance, the drugs acamprosate (best known by the brand name Campral), and topiramate (best known as Topamax) are widely prescribed to individuals with SUD because of their capacity to reduce craving and substance use [61]. These are hypothesized to support SUD recovery in a number of ways, all of which help modulate neuronal hyperexcitability associated with substance use and drug withdrawal states [particularly alcohol and benzodiazepines; 62, 63]. Evidence suggests that these medications also reduce physiological arousal, as evidenced by reduced heart rate [64, 65], mean arterial blood pressure [66], galvanic skin conductance [65, 67, 68], and blood cortisol [69], along with increases in HRV [67]. It is possible that acamprosate and topiramate are effecting benefit for some individuals at the level of the brain by inhibiting neural hyperexcitation, while for others the greatest benefit may be derived from the peripheral effects of the medications via reduced physiological arousal.

The postulate that these medications may confer benefit through cardiovascular modulation is supported by a large body of research indicating that a number of adrenergic-targeting medications including prazosin and doxazosin (alpha-1 adrenergic inverse agonists, or “alpha-blockers”) and propranolol (beta 1-and-2 adrenergic antagonist, or “beta-blockers”) that are widely used to treat hypertension, reduce craving and the use of alcohol and other drugs [70–78]. Potentially, these medications support SUD recovery by dampening high basal levels of sympathetic arousal commonly observed in individuals with SUD [75, 74, 77]. Whereas the effects on blood pressure are primarily driven by countering noradrenergic-mediated vasoconstriction via adrenergic receptors in the smooth muscle of the vasculature, effects on craving and substance use likely derive from direct actions on noradrenergic receptors found throughout the central nervous system. However, the role of these medications on altering baroreflex sensitivity and heart rate variability (Petersen et al., 2018) cannot be ruled out as potential mechanisms of action in addiction medicine.

In preliminary studies, Wilcox et al. [79] and Haass-Koffler et al. [80] observed greater reductions in alcohol use among individuals receiving prazosin or doxazosin compared to placebo in those with high resting blood pressure, but not healthy resting blood pressure. Examination of beta blocker efficacy in decreasing cocaine craving indicated drops in both craving and autonomic arousal to cocaine cues [77], though the relationship between the two has yet to be examined. While these ideas require further investigation, they present the potential for prescribers to use a brief assessment of basal heart rate and HRV to determine who might benefit most from these medications. Given heart rate/HRV can be easily measured using small, inexpensive and non-invasive devices—for instance, while a patient waits to be seen by their provider or using the pulse-oximeter when nursing staff take patients’ vitals—this may be a scalable precision medicine approach that could help match SUD medications to patients.

Conclusion: Body-Brain-Behavior

A continuum of alcohol and drug use behaviors can have multiple and intersecting negative effects on mental and physical health. Substance use behavior change and recovery from addiction thus can be facilitated by holistic interventions that span the brain-body divide. Neurocardiac adjunctive interventions offer an evidence-based approach to bolster an underlying physiological pathway between the brain and body via the baroreflex mechanism. HRV biofeedback modulates the baroreflex mechanism to improve cardiovascular health, help reduce craving responses to salient environmental cues, and promote cognitive control and emotion regulation. The baroreflex mechanism also may be modulated via a number of medications used to treat substance use disorders. There is utility in identifying homogeneous subgroups of persons who may be most likely to benefit from either behavioral or pharmacologic interventions that improve neurocardiac signaling. Recent advances in biosensors and smartphone applications offer the potential for just-in-time behavioral interventions such as HRV biofeedback and resonance paced breathing that are accessible to large numbers of persons and may have value in interrupting automatic trigger states that interfere with conscious goals to reduce or stop substance use. Given the health promoting benefits and absence of negative side effects from such biobehavioral approaches, greater utilization by practitioners and further investigation by researchers could have substantial impact on holistic recovery from addiction and broadly improve public health.

Human and animal rights

All reported studies/experiments with human or animal subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

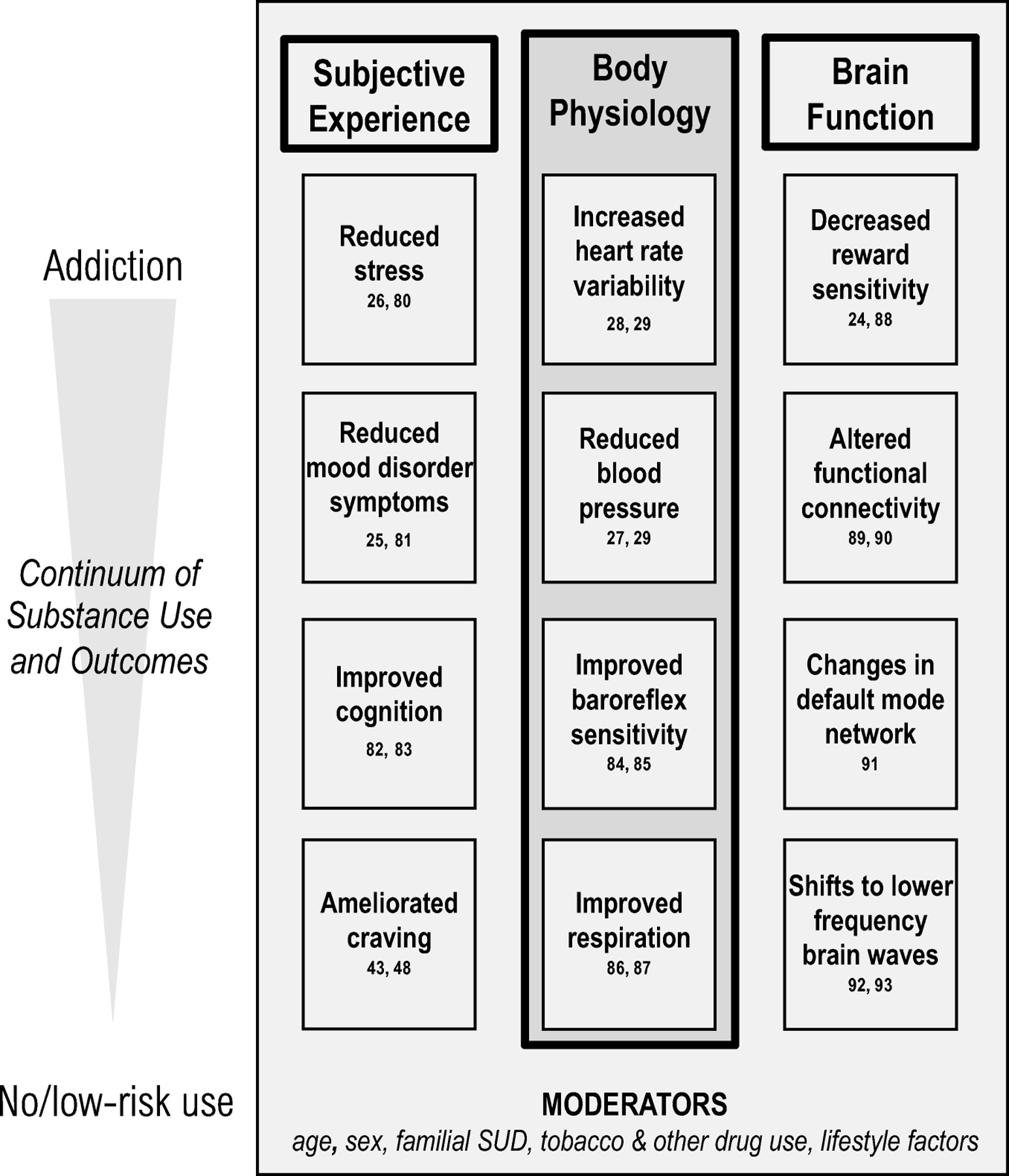

Figure 1.

Schematic highlighting the subjective, physiological, and neurological effects of heart rate variability biofeedback and resonance paced breathing on the continuum of substance use behaviors.

Acknowledgements:

The authors of this publication were supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awards T32AA028254, K02AA025123, K23AA027577-01A1, L30AA026135-02, and R01AA023667.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Contributor Information

David Eddie, Recovery Research Institute, Center for Addiction Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School

Julianne L. Price, Department of Kinesiology and Health, Center of Alcohol and Substance Use Studies, Rutgers University

Marsha E. Bates, Department of Kinesiology and Health, Center of Alcohol and Substance Use Studies, Rutgers University

Jennifer Buckman, Department of Kinesiology and Health, Center of Alcohol and Substance Use Studies, Rutgers University

References

- 1.Patel V, Chisholm D, Parikh R, Charlson FJ, Degenhardt L, Dua T et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet. 2016;387(10028):1672–85. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heiss S, Vaschillo B, Vaschillo EG, Timko CA, Hormes JM. Heart rate variability as a biobehavioral marker of diverse psychopathologies: A review and argument for an “ideal range”. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;121:144–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This recent work hypothesized that both decreased HRV and elevated HRV may be indicators of psychopathology and that biofeedback interventions could target an “ideal range” of HRV.

- 3.Lehrer PM, Gevirtz R. Heart rate variability biofeedback: how and why does it work? Front Psychol. 2014;5:756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leyro TM, Buckman JF, Bates ME. Theoretical implications and clinical support for heart rate variability biofeedback for substance use disorders. Current opinion in psychology. 2019;30:92–7. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gaps were identified in the substance use and HRV literature, and directions for future work that would best elucidate the factors that optimize HRV biofeedback interventions on an individual level were proposed.

- 5.Eddie D, Bates ME, Buckman JF. Closing the brain–heart loop: Towards more holistic models of addiction and addiction recovery. Addiction Biology. In press. doi: 10.1111/adb.12958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review identified the necessary role of cardiovascular functions and brain-body feedback in the contemporary biobehavioral models of addiction.

- 6.Critchley HD, Garfinkel SN. Interoception and emotion. Current opinion in psychology. 2017;17:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leganes-Fonteneau M, Buckman JF, Suzuki K, Pawlak A, Bates ME. More than meets the heart: systolic amplification of different emotional faces is task dependent. Cogn Emot. 2021;35(2):400–8. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2020.1832050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naqvi NH, Gaznick N, Tranel D, Bechara A. The insula: a critical neural substrate for craving and drug seeking under conflict and risk. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1316:53–70. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulus MP, Stewart JL. Interoception and drug addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2014;76:342–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayer EA, Labus J, Aziz Q, Tracey I, Kilpatrick L, Elsenbruch S et al. Role of brain imaging in disorders of brain-gut interaction: a Rome Working Team Report. Gut. 2019;68(9):1701–15. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tracey KJ. Reflex control of immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2009;9(6):418–28. doi: 10.1038/nri2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shouman K, Benarroch EE. Central Autonomic Network. In: Chokroverty S, Cortelli P, editors. Autonomic Nervous System and Sleep: Order and Disorder. Cham, switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Buckman JF, Pandina RJ, Bates ME. Measurement of vascular tone and stroke volume baroreflex gain. Psychophysiology. 2012;49(2):193–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Buckman JF, Pandina RJ, Bates ME. The investigation and clinical significance of resonance in the heart rate and vascular tone baroreflexes. In: Fred A, Filipe J, Gamboa H, editors. Biomedical engineering systems and technologies: Communications in computer and information science vol 4. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2011. p. 224–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gianaros PJ, Jennings JR. Host in the machine: A neurobiological perspective on psychological stress and cardiovascular disease. The American Psychologist. 2018;73(8):1031–44. doi: 10.1037/amp0000232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehrer P, Eddie D. Dynamic processes in regulation and some implications for biofeedback and biobehavioral interventions. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2013;38(2):143–55. doi: 10.1007/s10484-013-9217-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bates ME, Buckman JF. Integrating body and brain systems in addiction neuroscience. In: Miller P, editor. Biological research on addiction: Comprehensive addictive behaviors and disorders. New York, NY: Academic Press; 2013. p. 187–96. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eddie D, Buckman JF, Mun EY, Vaschillo B, Vaschillo EG, Udo T et al. Different associations of alcohol cue reactivity with negative alcohol expectancies in mandated and inpatient samples of young adults. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2040–3. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Buckman JF, Bates ME, Pandina RJ, editors. Resonances in the cardiovascular system: Investigation and clinical applications. BIOSTEC - 3rd International Joint Conference; 2010; Valencia, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckman JF, Vaschillo EG, Fonoberova M, Mezic I, Bates ME. The Translational Value of Psychophysiology Methods and Mechanisms: Multilevel, Dynamic, Personalized. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79(2):229–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Buckman JF, Heiss S, Singh G, Bates ME. Early signs of cardiovascular dysregulation in young adult binge drinkers. Psychophysiology. 2018;55(5):e13036. doi: 10.1111/psyp.13036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buckman JF, Eddie D, Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Garcia A, Bates ME. Immediate and complex cardiovascular adaptation to an acute alcohol dose. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39(12):2334–44. doi: 10.1111/acer.12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Critchley HD, Harrison NA. Visceral influences on brain and behavior. Neuron. 2013;77(4):624–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bates ME, Lesnewich LM, Uhouse SG, Gohel S, Buckman JF. Resonance-paced breathing alters neural response to visual cues: Proof-of-concept for a neuroscience-informed adjunct to addiction treatments. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;10:624. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehrer P, Kaur K, Sharma A, Shah K, Huseby R, Bhavsar J et al. Heart rate variability biofeedback improves emotional and physical health and performance: A systematic review and meta analysis. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2020;45(3):109–29. doi: 10.1007/s10484-020-09466-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goessl VC, Curtiss JE, Hofmann SG. The effect of heart rate variability biofeedback training on stress and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2017;47(15):2578–86. doi: 10.1017/s0033291717001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaschillo EG, Lehrer P, Rishe N, Konstantinov M. Heart rate variability biofeedback as a method for assessing baroreflex function: A preliminary study of resonance in the cardiovascular system. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2002;27:1–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwerdtfeger AR, Schwarz G, Pfurtscheller K, Thayer JF, Jarczok MN, Pfurtscheller G. Heart rate variability (HRV): From brain death to resonance breathing at 6 breaths per minute. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131(3):676–93. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2019.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review discussed the implications of heart rate variability across a wide range of physical and mental health conditions. Evidence supported the potential utility of HRV biofeedback/resonance paced breathing to broadly promote physical and psychological health.

- 29.Steffen PR, Austin T, DeBarros A, Brown T. The impact of resonance frequency breathing on measures of heart rate variability, blood pressure, and mood. Frontiers in public health. 2017;5:222. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin G, Xiang Q, Fu X, Wang S, Wang S, Chen SA et al. Heart rate variability biofeedback decreases blood pressure in prehypertensive subjects by improving autonomic function and baroreflex. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2012;18(2):143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goessl VC, Curtiss JE, Hofmann SG. The effect of heart rate variability biofeedback training on stress and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2017;47(15):2578–86. doi: 10.1017/s0033291717001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benarroch EE. Central autonomic control. In: Low PA, Robertson D, Burnstock G, Paton JFR, Biaggioni I, editors. Primer on the autonomic nervous system. 3 ed. London, UK: Elsevier; 2012. p. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):217–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karavidas MK, Lehrer PM, Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Marin H, Buyske S et al. Preliminary Results of an Open Label Study of Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback for the Treatment of Major Depression. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2007;32(1):19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siepmann M, Aykac V, Unterdorfer J, Petrowski K, Mueck-Weymann M. A pilot study on the effects of heart rate variability biofeedback in patients with depression and in healthy subjects. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2008;33(4):195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beckham AJ, Greene TB, Meltzer-Brody S. A pilot study of heart rate variability biofeedback therapy in the treatment of perinatal depression on a specialized perinatal psychiatry inpatient unit. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(1):59–65. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0318-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin IM, Fan SY, Yen CF, Yeh YC, Tang TC, Huang MF et al. Heart rate variability biofeedback increased autonomic activation and improved symptoms of depression and insomnia among patients with major depression disorder. Clinical psychopharmacology and neuroscience : the official scientific journal of the Korean College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;17(2):222–32. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2019.17.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zucker TL, Samuelson KW, Muench F, Greenberg MA, Gevirtz RN. The effects of respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback on heart rate variability and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms: A pilot study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2009;34:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan G, Dao TK, Farmer L, Sutherland RJ, Gevirtz R. Heart rate variability (HRV) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A pilot study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2011;36:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ginsberg JP, Berry ME, Powell DA. Cardiac coherence and posttraumatic stress disorder in combat veterans. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2009;16(4):52–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reyes FJ. Implementing heart rate variability biofeedback groups for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback. 2014;42(4):137–42. doi: 10.5298/1081-5937-42.4.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuman DL, Killian MO. Pilot Study of a Single Session Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Intervention on Veterans’ Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2019;44(1):9–20. doi: 10.1007/s10484-018-9415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eddie D, Vaschillo E, Vaschillo B, Lehrer P. Heart rate variability biofeedback: Theoretical basis, delivery, and its potential for the treatment of substance use disorders. Addiction Research & Theory. 2015;23(4):266–72. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2015.1011625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alayan N, Eller L, Bates ME, Carmody DP. Current evidence on heart rate variability biofeedback as a complementary anticraving intervention. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24(11):1039–50. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eddie D, Kim C, Lehrer P, Deneke E, Bates ME. A pilot study of brief heart rate variability biofeedback to reduce craving in young adult men receiving inpatient treatment for substance use disorders. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2014;39(3):181–92. doi: 10.1007/s10484-014-9251-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Penzlin AI, Barlinn K, Illigens BM, Weidner K, Siepmann M, Siepmann T. Effect of short-term heart rate variability biofeedback on long-term abstinence in alcohol dependent patients - a one-year follow-up. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):325. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1480-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Penzlin AI, Siepmann T, Illigens BM-W, Weidner K, Siepmann M. Heart rate variability biofeedback in patients with alcohol dependence: A randomized controlled study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2015;11:2619–27. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S84798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eddie D, Conway FN, Alayan N, Buckman JF, Bates ME. Assessing heart rate variability biofeedback as an adjunct to college recovery housing programs. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;92:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alayan N, Eddie D, Eller L, Bates ME, Carmody DP. Substance craving changes in university students receiving heart rate variability biofeedback: A longitudinal multilevel modeling approach. Addict Behav. 2019;97:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quintana DS, Guastella AJ, McGregor IS, Hickie IB, Kemp AH. Heart rate variability predicts alcohol craving in alcohol dependent outpatients: Further evidence for HRV as a psychophysiological marker of self-regulation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:395–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laborde S, Allen MS, Borges U, Hosang TJ, Furley P, Mosley E et al. The influence of slow-paced breathing on executive function. Journal of Psychophysiology. In press. doi: 10.1027/0269-8803/a000279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wells R, Outhred T, Heathers JAJ, Quintana DS, Kemp AH. Matter over mind: A randomised-controlled trial of single-session biofeedback training on performance anxiety and heart rate variability in musicians. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hasuo H, Kanbara K, Fukunaga M. Effect of Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback sessions with resonant frequency breathing on sleep: A pilot study among family caregivers of patients with cancer. Frontiers in medicine. 2020;7:61. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Zwan JE, Huizink AC, Lehrer PM, Koot HM, de Vente W. The Effect of Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Training on Mental Health of Pregnant and Non-Pregnant Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(6). doi: 10.3390/ijerph16061051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dobbs WC, Fedewa MV, MacDonald HV, Holmes CJ, Cicone ZS, Plews DJ et al. The accuracy of acquiring heart rate variability from portable devices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019;49(3):417–35. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hinde K, White G, Armstrong N. Wearable devices suitable for monitoring twenty four hour heart rate variability in military populations. Sensors. 2021;21(4). doi: 10.3390/s21041061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Georgiou K, Larentzakis AV, Khamis NN, Alsuhaibani GI, Alaska YA, Giallafos EJ. Can wearable devices accurately measure heart rate variability? A systematic review. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2018;60(1):7–20. doi: 10.2478/folmed-2018-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chung A, Gevirtz R, Gharbo R, Thiam M, Ginsberg JP. Pilot Study on Reducing Anxiety with a Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback Wearable and Remote Stress Management Coach. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meyer RE. Pharmacotherapy of substance use disorders: Challenges and opportunities. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40(4):330–3. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0000000000001218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zindel LR, Kranzler HR. Pharmacotherapy of alcohol use disorders: Seventy-five years of progress. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs Supplement. 2014;75 Suppl 17(Suppl 17):79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Plosker GL. Acamprosate: A review of its use in alcohol dependence. Drugs. 2015;75(11):1255–68. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott LJ, Figgitt DP, Keam SJ, Waugh J. Acamprosate: a review of its use in the maintenance of abstinence in patients with alcohol dependence. CNS Drugs. 2005;19(5):445–64. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200519050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spanagel R, Vengeliene V, Jandeleit B, Fischer WN, Grindstaff K, Zhang X et al. Acamprosate produces its anti-relapse effects via calcium. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(4):783–91. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sofuoglu M, Poling J, Mouratidis M, Kosten T. Effects of topiramate in combination with intravenous nicotine in overnight abstinent smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;184(3–4):645–51. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ooteman W, Koeter MWJ, Verheul R, Schippers GM, van den Brink W. The effect of naltrexone and acamprosate on cue-induced craving, autonomic nervous system and neuroendocrine reactions to alcohol-related cues in alcoholics. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;17(8):558–66. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miranda R Jr., MacKillop J, Treloar H, Blanchard A, Tidey JW, Swift RM et al. Biobehavioral mechanisms of topiramate’s effects on alcohol use: an investigation pairing laboratory and ecological momentary assessments. Addict Biol. 2016;21(1):171–82. doi: 10.1111/adb.12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Agelink MW, Lemmer W, Malessa R, Zeit T, Majewski T, Klieser E. Improved autonomic neurocardial balance in short-term abstinent alcoholics treated with acamprosate. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1998;33(6):602–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reid MS, Palamar J, Raghavan S, Flammino F. Effects of topiramate on cue-induced cigarette craving and the response to a smoked cigarette in briefly abstinent smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2007;192(1):147–58. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0755-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hammarberg A, Jayaram-Lindstrom N, Beck O, Franck J, Reid MS. The effects of acamprosate on alcohol-cue reactivity and alcohol priming in dependent patients: A randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;205(1):53–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1515-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Simpson TL, Saxon AJ, Stappenbeck C, Malte CA, Lyons R, Tell D et al. Double-blind randomized clinical trial of prazosin for alcohol use disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2018. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17080913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fox HC, Anderson GM, Tuit K, Hansen J, Kimmerling A, Siedlarz KM et al. Prazosin effects on stress-and cue-induced craving and stress response in alcohol-dependent individuals: Preliminary findings. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(2):351–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: A pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1–2):66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, Edwards SM, Brickley MB, Swift RM et al. Role of the alpha1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: A proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addiction Biology. 2016;21(4):904–14. doi: 10.1111/adb.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verplaetse TL, Weinberger AH, Oberleitner LM, Smith KM, Pittman BP, Shi JM et al. Effect of doxazosin on stress reactivity and the ability to resist smoking. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2017;31(7):830–40. doi: 10.1177/0269881117699603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Newton TF, De La Garza R II, Brown G, Kosten TR, Mahoney JJ III, Haile CN. Noradrenergic α1 receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: A randomized trial. PloS One. 2012;7(2):e30854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Srinivasan AV. Propranolol: A 50-Year Historical Perspective. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2019;22(1):21–6. doi: 10.4103/aian.AIAN_201_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saladin ME, Gray KM, McRae-Clark AL, Larowe SD, Yeatts SD, Baker NL et al. A double blind, placebo-controlled study of the effects of post-retrieval propranolol on reconsolidation of memory for craving and cue reactivity in cocaine dependent humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;226(4):721–37. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3039-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kampman KM, Volpicelli JR, Mulvaney F, Alterman AI, Cornish J, Gariti P et al. Effectiveness of propranolol for cocaine dependence treatment may depend on cocaine withdrawal symptom severity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wilcox CE, Tonigan JS, Bogenschutz MP, Clifford J, Bigelow R, Simpson T. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of prazosin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. J Addict Med. 2018;12(5):339–45. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haass-Koffler CL, Goodyear K, Zywiak WH, Magill M, Eltinge SE, Wallace PM et al. Higher pretreatment blood pressure is associated with greater alcohol drinking reduction in alcohol-dependent individuals treated with doxazosin. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:23–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Haass-Koffler and colleagues identified pretreatment cardiovascular function as a moderating factor in an alpha-blockers’ efficacy in decreasing drinking in a treatment-seeking sample.

- 81.Blase K, Vermetten E, Lehrer P, Gevirtz R. Neurophysiological Approach by Self-Control of Your Stress-Related Autonomic Nervous System with Depression, Stress and Anxiety Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7). doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pizzoli SFM, Marzorati C, Gatti D, Monzani D, Mazzocco K, Pravettoni G. A meta-analysis on heart rate variability biofeedback and depressive symptoms. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6650. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86149-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Prinsloo GE, Rauch HG, Lambert MI, Muench F, Noakes TD, Derman WE. The effect of short duration heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback on cognitive performance during laboratory induced cognitive stress. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2011;25:792–801. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jester DJ, Rozek EK, McKelley RA. Heart rate variability biofeedback: Implications for cognitive and psychiatric effects in older adults. Aging & mental health. 2019;23(5):574–80. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1432031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lehrer P, Vaschillo EG, Lu S-E, Eckberg D, Vaschillo B, Scardella A et al. Heart rate variability biofeedback: Effects of age on heart rate variability, baroreflex gain, and asthma. Chest. 2006;129:278–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Lehrer PM. Characteristics of resonance in heart rate variability stimulated by biofeedback. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2006;31:129–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lehrer P, Smetankin A, Potapova T. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback therapy for asthma: A report of 20 unmedicated pediatric cases using the Smetankin method. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2000;25(3):193–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lehrer P, Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Lu SE, Scardella A, Siddique M et al. Biofeedback treatment for asthma. Chest Journal. 2004;126:352–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Critchley HD, Nicotra A, Chiesa PA, Nagai Y, Gray MA, Minati L et al. Slow breathing and hypoxic challenge: Cardiorespiratory consequences and their central neural substrates. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schumann A, Köhler S, de la Cruz F, Brotte L, Bär K-J, editors. Effect heart rate variability biofeedback on autonomic function and functional connectivity of the prefrontal cortex. 2020 11th Conference of the European Study Group on Cardiovascular Oscillations (ESGCO); 2020; Pisa, Italy: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mather M, Thayer J. How heart rate variability affects emotion regulation brain networks. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2018;19:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Park SM, Jung HY. Respiratory sinus arrhythmia biofeedback alters heart rate variability and default mode network connectivity in major depressive disorder: A preliminary study. Int J Psychophysiol. 2020;158:225–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Prinsloo GE, Rauch HG, Karpul D, Derman WE. The effect of a single session of short duration heart rate variability biofeedback on EEG: A pilot study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2013;38(1):45–56. doi: 10.1007/s10484-012-9207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Park YJ, Park YB. Clinical utility of paced breathing as a concentration meditation practice. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20(6):393–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]